Abstract

Study of the prognostic impact of multidrug resistance gene expression in the management of breast cancer in the context of adjuvant therapy. This study involved 171 patients treated by surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy±radiotherapy±hormonal therapy (mean follow-up: 55 months). We studied the expression of multidrug resistance gene 1 (MDR1), multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP1), and glutathione-S-transferase P1 (GSTP1) using a standardised, semiquantitative rt–PCR method performed on frozen samples of breast cancer tissue. Patients were classified as presenting low or high levels of expression of these three genes. rt-PCR values were correlated with T stage, N stage, Scarff–Bloom–Richardson (SBR) grade, age and hormonal status. The impact of gene expression levels on 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) was studied by univariate and multivariate Cox analysis. No statistically significant correlation was demonstrated between MDR1, MRP1 and GSTP1 expressions. On univariate analysis, DFS was significantly decreased in a context of low GSTP1 expression (P=0.0005) and high SBR grade (P=0.003), size ⩾5 cm (P=0.038), high T stage (P=0.013), presence of intravascular embolus (P=0.034), and >3 N+ (P=0.05). On multivariate analysis, GSTP1 expression and the presence of ER remained independent prognostic factors for DFS. GSTP1 expression did not affect OS. The levels of MDR1 and MRP1 expression had no significant influence on DFS or OS. GSTP1 expression can be considered to be an independent prognostic factor for DFS in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer.

Keywords: MDR1 , MRP1 , GSTP1 , rt–PCR, breast cancer, prognosis

The increasing use of adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer, designed to improve both disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS), highlights the need to develop predictive tests of tumour chemosensitivity in order to identify patients likely or unlikely to benefit from such therapy (Bonadonna et al, 1990; Scholl et al, 1994). Cytotoxic exposure can induce a multidrug resistance phenotype (MDR), which can involve numerous cell changes (Simon and Schindler, 1994). Some proteins are overexpressed in MDR cell lines, defining a group of MDR-related genes. In humans, P-glycoprotein (P-gp), encoded by the multidrug resistance gene 1 gene (MDR1) (Endicott and Ling, 1989; Gottesman and Pastan, 1993), and multidrug resistance-related protein MRP1, first described by Cole et al (1994), are two membrane glycoprotein transporters belonging to the more extensive superfamily of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins (Dean et al, 2001). More recently, other members of this family have been implicated in multidrug resistance of breast cancer, such as BCRP/ABCG2 and other forms (Leonessa and Clarke, 2003). Such proteins act as energy-dependent efflux pumps capable of expelling a large range of xenobiotics, including doxorubicin and other cytotoxic drugs derived from natural products, out of the cell. MRP1 can act as a transporter of glutathione conjugates (Muller et al, 1994). Although the precise role of the glutathione detoxification pathway in the MDR phenomenon has not yet been fully elucidated, the isoenzymes of the glutathione-S-transferase (GSTs), namely the subclass GSTpi (EC 2.5.1.18), have been extensively reported to be overexpressed in tumour cells displaying the MDR phenotype (Keith et al, 1990; Buser et al, 1997; Ferrandina et al, 1997; Frassoldati et al, 1997; Silvestrini et al, 1997; Boku et al, 1998; Stoehlmacher et al, 2002; Oudard et al, 2002; Cullen et al, 2003; Galimberti et al, 2003; Bennaceur-Griscelli et al, 2004). However, the role of GSTs proteins remains controversial in the literature.

In a previous study, we used a semiquantitative rt–PCR method to evaluate multidrug resistance gene expression in surgical breast cancer biopsies (Lacave et al, 1998). The primary objective of the present study was to complete this preliminary study by evaluating the clinical impact of the expression of these genes on the management of breast cancer in a series of 171 patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy.

PATIENTS, MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and tissue samples

This study was performed on a series of 171 surgically obtained tumour specimens from 171 patients with stage I–III invasive breast carcinoma, treated between April 1991 and January 2001 by surgery (Surgical Gynecology Departments, at the La Pitié Salpêtrière and Tenon Hospitals), adjuvant chemotherapy (Medical Oncology and Radiation Oncology Department, Tenon Hospital, Paris, France), +/− postoperative radiotherapy (Radiation Oncology Department, Tenon Hospital, Paris, France), +/− hormonal therapy (Medical Oncology and Radiation Oncology Department, Tenon Hospital, Paris, France). The mean and median ages were 54 and 52 years, respectively (range: 34–77), and 54% of patients were postmenopausal. First-line treatment was tumorectomy in 59.6% of patients (n=102), and radical mastectomy in 40.4% of patients (n=69) with axillary dissection in all cases. All patients received adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy were excluded from this study. Radiotherapy was performed in 162 cases (94.7%), and 117 patients (68.4%) received hormonal therapy. Details of the systemic treatments used are given in Table 1. Most patients received anthracyclines (n=163; 95%). The clinical and pathological characteristics of the study population are also described in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Patients (n) | Patients (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | SBR grade | ||

| ⩽55 | 102 | I | 28 |

| >55 | 69 | II | 73 |

| III | 67 | ||

| Not available | 3 | ||

| Postmenopausal | DNA ploidy | ||

| Yes | 92 | Diploid | 58 |

| No | 79 | Aneuploid | 83 |

| Not available | 30 | ||

| Clinical T stage | S-phase fraction | ||

| T1 | 85 | Low | 35 |

| T2 | 73 | Medium | 39 |

| T3 | 6 | High | 52 |

| T4 | 7 | Not available | 45 |

| Histological nodal status | Oestrogen receptors | ||

| N− | 64 | Yes | 111 |

| N+ | 106 | No | 48 |

| Not available | 1 | Not available | 12 |

| Number of positive nodes | Progesterone receptors | ||

| <3 N+ | 66 | Yes | 87 |

| ⩾3 N+ | 39 | No | 68 |

| Not available | 16 | ||

| Capsular invasion | Postoperative radiotherapy | ||

| C I− | 116 | Yes | 162 |

| C I+ | 54 | No | 9 |

| Not available | 1 | ||

| Histologic type | Adjuvant hormonal therapy | ||

| Ductal | 139 | Yes | 117 |

| Lobular | 23 | No | 51 |

| Others | 9 | Not available | 3 |

| Associated extensive in situ carcinomas | Type of chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 44 | FEC | 147 |

| No | 123 | THEP VCF | 15 |

| Not available | 4 | FNC | 7 |

| EP | 1 | ||

| CMF | 1 | ||

| Intravascular embolus | |||

| Yes | 49 | ||

| No | 107 | ||

| Not available | 15 | ||

FEC=fluorouracil, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide; THEPVCF=theprubicin, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, fluorouracil; CMF=cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil; FNC=fluorouracil, novantron, cyclophosphamide; EP=epirubicin, paclitaxel.

Histopathologic typing, Scarff–Bloom–Richardson (SBR) grading and measurement of oestrogen (ER) and progesterone (PR) receptor levels (cutoff value: 10 fmol mg−1) were performed by independent investigators. DNA ploidy and S-phase fraction (SPF) were determined by DNA flow cytometry, using a standardised method and consensus rules for interpreting the data (Chassevent et al, 2001). Tumours containing a single cell population with a DNA index ranging between 0.9 and 1.05 were classified as diploid, and those with an additional cell population with a DNA index outside the 0.9–1.05 range were defined as aneuploid. The SPF was classified as three SPF classes, defined on the basis of terciles (33rd and 66th percentile) after adjusting for ploidy.

rt–PCR studies

The conditions and methodological aspects of the end point rt–PCR procedures used in this study have been previously described in detail (Lacave et al, 1998). Although real-time PCR has been established as the gold standard rt–PCR procedure for gene expression studies since the end of the 1990s, most patients described here were included in the mid-1990s, at a time when real-time PCR was not routinely performed in the majority of laboratories. We therefore chose to maintain the classical end point rt–PCR method for all of these patients. Briefly, each gene of interest was separately coamplified with its specific endogenous standard (i.e. MDR1/β2M; MRP1/PGK; GSTπ/PGK). For MDR1, the control cell lines consisted of the drug-sensitive human epidermoid carcinoma KB3-1 cell line and its multidrug-resistant derivative, the KB 8-5 cell line (kindly provided by Dr Gottesman) (Akiyama et al, 1985). The MCF7 human breast carcinoma cell line (Soule et al, 1973) was obtained from J Robert (Institut Bergonié, Bordeaux, France), and was also used to select the doxorubicin-resistant cell line (MCF7R) used in this study. These cell lines were used as negative and positive controls for GST P1 (GSTP1), respectively. The IGROV cell line was obtained from J Bénard (Benard et al, 1985), and was used as a negative control vs MCF7R to check for MRP1 expression. Historically, β2M has been proposed for use as an internal standard for MDR1 (Beck et al, 1996) when KB cell lines are used as the control cell line (see below). Owing to the lack of β2M expression in MCF7R, PGK was used as the internal standard for MRP1 and GSTP1. The gene of interest/endogenous standard ratio of test samples was expressed in relation to the ratio found for control cell lines overexpressing the gene tested. Calculated values were expressed in arbitrary units. Control cell lines were also used to determine the standard curves by serial dilutions of total RNA extracted from drug-resistant cell lines, with total RNA extracted from their respective drug-sensitive cell lines in order to validate and standardise the rt–PCR conditions for optimal coamplification of the genes tested and their respective internal control sequences. We had also previously checked that the values obtained for control cell lines always displayed low ranges of interassay variation (coefficient of variation <10% in every case). Owing to the high degree of heterogeneity observed with the rt–PCR procedures used in previous studies to determine the expression of MDR-related genes, no cutoff values have been clearly defined and, in the present study, as shown in Table 2, we chose to define the subgroups on the basis of the estimated median values of gene expression for each gene (⩽ or > the median value) (Table 2).

Table 2. Definition of subgroups according to the median value of gene expression.

|

Gene expression

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Low | High | |

| MDR1 | ⩽2% (n=93) | >2% (n=72) |

| MRP1 | ⩽61.7% (n=105) | >61.7% (n=66) |

| GSTP1 | ⩽63% (n=61) | >63% (n=59) |

Statistical methods

Comparisons between the levels of expression of the three genes studied and patient characteristics were performed using Pearson's χ2 test. A two-sided P<0.05 was considered significant. The DFS was defined as the interval between first treatment and primary failure (local and/or distant recurrence). Actuarial survival rates were computed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and compared using the log rank test (Kaplan and Meier, 1958). The influence of DNA ploidy and SPF fraction on outcome, adjusted for the other prognostic factors, was assessed by univariate and multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards regression model in a forward stepwise procedure (Cox, 1972). The ascending method was used for a block-by-block construction (clinical variables, and then laboratory variables). The various variables were: (a) age at diagnosis (⩽ or >50 years); (b) menopausal status; (c) clinical T stage (T1; T2; T3; T4); (d) histologic type (ductal or lobular carcinoma); (e) histologic lymph node involvement (N−; N+); (f) number of lymph nodes involved (< or ⩾3N+); (g) capsular invasion (CI−; CI+); (h) histologic grade (SBR I–III); (i) surgical margins (⩽ or >1 mm); (j) vascular invasion; (k) associated extensive (>25%) in situ carcinoma; (l) intravascular and intralymphatic embolus; (m) hormone receptor status; (n) DNA ploidy; (o) SPF adjusted for ploidy; and expression of (p) MDR1; (q) MRP1 and (r) GSTP1 genes, each divided into two groups according to whether gene expression was less than or greater than the median value of expression. As most patients received radiotherapy (94.7%) and anthracycline-based adjuvant chemotherapy (95%), we deliberately excluded the type of adjuvant therapy received by the patients from statistical analysis. The study end points compared the levels of expression of each of the three genes with those of the other two multidrug resistance genes, and evaluated the influence of multidrug resistance gene expression on 5-year actuarial DFS, and overall specific survival (OS) rates. Complete information for follow-up and secondary events were obtained for all patients. The median follow-up from the beginning of treatment was 56 months (range: 7–139 months).

RESULTS

Tumour characteristics and flow cytometry

Most tumours were ductal (n=139; 81%), or lobular carcinomas (n=23; 13. 5%). The main characteristics of the samples are summarised in Table 1. Most tumours were early-stage carcinomas (T1–T2: n=158; 92%), and were node positive (n=106; 62%). The hormonal status was available in 159 patients (93%). In all, 141 samples were evaluated by cytometry. A total of 58 tumours were diploid (41%), and 83 were aneuploid (59%). Only 126 of these 141 tumour samples were available for SPF evaluation, and tumour samples were divided into three SPF prognosis groups: tumours with low SPF values (n=35: 28%), intermediate SPF values (n=39: 31%) and high SPF values (n=52: 41%).

RT–PCR analysis of tumour samples

Determination of MDR1 expression was available for 164 tumours (96%). When compared with the negative KB 3.1 and positive KB 8.5 control cell lines, 68 (42%) of tumours did not express the MDR1 gene, while 96 tumours (58%) expressed MDR1. The mean value of the MDR1/β2M ratio was 0.052±0.008 (range: 0–0.065), with a median of 0.02.

MRP1 expression was assessed for 131 tumour samples (77%), with a mean MRP1/PGK ratio of 0.75±0.08 (range: 0–10), and a median of 0.61. Only 10 tumours (7.6%) did not express the MRP1 gene.

GSTP1 expression was evaluated in 119 tumour samples (70%), and only three tumours were found not to express this gene. The mean GSTP1/PGK ratio was 0.74±0.06 (range: 0–4.6) with a median of 0.63.

Table 3 reports the levels of expression of the three genes in relation to the clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients and samples. No statistically significant difference in the expression of any of the MDR-related genes was observed between any of the subgroups, apart from tumours with negative ER or PR, in which GSTP1 expression was significantly higher.

Table 3. MDR phenotype according to patient and tumor characteristics.

| MDR1 | MRP | GSTp | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) a | ||||||

| ⩽55 | 5.86±1.12 | 0.288 | 83.79±7.77 | 0.745 | 70.3±16.91 | 0.459 |

| >55 | 4.18±0.95 | 63.82±6.38 | 80.1±11.22 | |||

| Postmenopausal | ||||||

| Yes | 3.97±0.75 | 0.09 | 70.96±7.85 | 0.976 | 81.3±9.44 | 0.222 |

| No | 6.59±1.42 | 81.78±18.15 | 65.18±8.44 | |||

| Clinical T stage | ||||||

| T1 | 4.95±1.04 | 0.534 | 104.21±17.93 | 0.029 | 77.1±9.92 | 0.362 |

| T2 | 4.83±1.09 | 54.74±6.1 | 69.51±7.19 | |||

| T3 | 11.2±9.49 | 35.53±15.57 | 123.8±84.76 | |||

| T4 | 7.25±5.1 | 43.5±18.28 | 49.5±20.41 | |||

| Histologic type b | ||||||

| Ductal carcinomas | 5.61±0.93 | 0.289 | 81.82±10.68 | 0.284 | 73.04±6.9 | 0.524 |

| Lobular carcinomas | 3.32±1.38 | 53.08±11.93 | 85.31±22.6 | |||

| SBR grade c | ||||||

| SBRI | 5.13±2.16 | 0.804 | 71.83±13.7 | 0.933 | 89.63±21.75 | 0.622 |

| SBRII | 4.74±0.96 | 82.37±19.41 | 66.4±8.86 | |||

| SBRIII | 5.87±1.42 | 70.02±7.82 | 76.83±9.31 | |||

| Histologic nodal status | ||||||

| N− | 6.18±1.58 | 0.326 | 79.67±19.59 | 0.465 | 85.15±10.0 | 0.230 |

| N+ | 4.59±0.8 | 72.04±7.54 | 68.91±8.56 | |||

| Intravascular embolism | ||||||

| Yes | 5.28±1.39 | 0.684 | 73.66±11.83 | 0.963 | 57.07±10.68 | 0.08 |

| No | 4.63±0.87 | 75.16±12.53 | 82.7±8.4 | |||

| Associated extensive in situ carcinoma | ||||||

| Yes | 6.04±1.58 | 0.56 | 77.04±12.9 | 0.56 | 71.32±13.25 | 0.7 |

| No | 4.98±0.91 | 74.84±11.31 | 77.33±7.71 | |||

| Oestrogen receptor status | ||||||

| Negative | 7.45±2.04 | 0.08 | 60.67±5.16 | 99.09±12.3 | ||

| Positive | 4.29±0.78 | 79.31±12.56 | 0.59 | 65.39±8.05 | 0.028 | |

| Progesterone receptor status | ||||||

| Negative | 5.51±1.52 | 0.835 | 67.99±8.29 | 0.571 | 87.04±8.7 | 0.038 |

| Positive | 5.15±0.95 | 79.43±16.72 | 59.99±9.47 | |||

| DNA ploidy | ||||||

| Diploid | 5.45±1.57 | 0.735 | 69.63±10.44 | 0.164 | 68.19±11.26 | 0.298 |

| Aneuploid | 6.10±1.15 | 61.51±5.85 | 84.31±9.84 | |||

| S-phase fraction | ||||||

| Low | 5.1±1.43 | 0.312 | 75.66±11.11 | 0.580 | 84.32±15.63 | 0.719 |

| Medium | 4.52±1.59 | 71.79±13.61 | 81.72±13.68 | |||

| High | 7.95±1.96 | 61.29±6.4 | 70.8±7.4 |

Patient's age.

Other histologic types were excluded.

SBR: Scarff–Bloom–Richardson index.

Values are expressed as mean±s.e. of RNA levels of MDR1, MRP1 and GSTP1 rt–PCR products, expressed as a percentage of control cell lines. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare these variables.

When the values were analysed as continuous values, no statistically significant correlation was found between MDR1, MRP1 and GSTP1 expression.

Patient outcome

Nine (5.5%) patients developed local recurrence after a mean interval of 27.5 months (range: 2–49 months), three (1.7%) patients developed a regional axillary relapse (mean interval: 29 months, range: 9–53 months), and 24 patients (14%) developed distant metastasis after a mean interval of 36 months (range: 3–83 months). In all, 18 patients had died at the endpoint date of this analysis: 17 from cancer (10%) and one from another cause. A total of 16 (9.3%) patients developed a second cancer (breast and/or another primary tumour).

The 5-year DFS rate was 79.7% (±3.3; [73.3–86.6]) in the overall population, 82% (±5.6; [71.7; 93.7]) among node-negative patients, and 79.3% (±4.2; [71.5–87.9]) among node-positive patients (P=0.38). The 5-year specific survival was 89.7% (±2.7; [84.5–95.2]) in the overall population, 93.3% (±3.9; [85.9–1]) among node-negative patients, and 88.3% (±3.6; [81.6–95.6]) among node-positive patients (P=0.26).

Prognostic impact of multidrug resistance genes

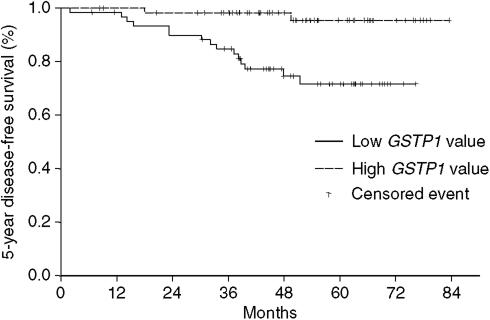

In the overall population, univariate Cox analysis showed a better 5-year DFS rate in the group of patients with high GSTP1 expression than in the group with low GSTP1 expression (95.4±0.03% [89.2–100] versus 71.9±0.06% [60.4–85.6]; HR=0.33; P=0.0005, Figure 1). Other factors found to be significantly correlated with DFS on univariate analysis were SBR grade (P=0.039), T stage (P=0.013), more than three positive nodes (P=0.05), and presence of intravascular and intralymphatic embolus (P=0.034) (Table 4). Expression of the other two multidrug resistance genes, MDR1 and MRP1, did not influence 5-year DFS.

Figure 1.

5-year disease-free survival according to level of GSTP1 expression.

Table 4. 5-year disease-free survival rates and Cox univariate analysis.

| n pts | 5-year DFS (±s.e.) (%) [CI] | P; HR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSTπ | 0.0005; 0.33 | ||

| Low expression | 60 | 71.9 (±6.3) [60.4–85.6] | |

| High expression | 60 | 95.4 (±3.3) [89.2–100] | |

| NA | 51 | ||

| T Stage | 0.013; 2.48 | ||

| T1 | 85 | 87.4 (±3.7) [80.4–95.1] | |

| T2 | 73 | 77 (±6) [66.1–89.8] | |

| T3 | 6 | 25.5 (±26.3) [4–100] | |

| T4 | 7 | 46.8 (±18.2) [21.9–100] | |

| Intravascular embolus | 0.034; 1.53 | ||

| Yes | 49 | 70.4 (±7) [57.9–85.7] | |

| No | 107 | 86.9 (±3.7) [80.1–94.2] | |

| SBR grade | 0.039; 1.75 | ||

| SBRI | 28 | 100 | |

| SBRII | 73 | 74.6 (±5.6) [64.4–86.5] | |

| SBRIII | 67 | 77.2 (±5.4) [67.2–88.7] | |

| >3 N+ | 0.05; 2.17 | ||

| Yes | 39 | 71.3 (±7.3) [58.2–87.2] | |

| No | 66 | 83 (±3.7) [75.9–90.7] |

NA=not available; N Pts=number of patients; SBR=Scarff–Bloom–Richardson; T=T stage according to TNM AJCC 2002 classification; [CI]=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio.

>3N+=more than three positive nodes involved.

On multivariate analysis (Table 5), complete clinical and laboratory data were available for 90 patients. In the overall population, ER receptor status and subgroups based on GSTP1 expression were shown to be independent predictors for DFS (P=0.002 and 0.011, respectively).

Table 5. Cox multivariate analysis for 5-year disease-free survival.

|

Overall population (n=90)

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Relative risk (s.e.) | P | |

| Oestrogen receptor status | 0.066 (0.876) | 0.002 |

| GST P1 level expression (⩽ vs >63%) | 0.302 (0.469) | 0.011 |

Model for overall population included the following factors (factors with a P-value <0.2 using univariate analysis): SBR grade, T stage, clinical and histologic node involvement, number of lymph nodes involved (< or ⩾3 N+), capsular invasion, presence of intravascular or intratumoral embolus, presence of intraductal or intralobular extensive carcinoma, oestrogen receptor status, MDR1 and GSTP1 gene expression.

On univariate analysis, only two factors statistically influenced the 5-year OS rate: SBR grade (P=0.028), and clinical lymph node status (N0 vs N1, P=0.039). Expression of the three multidrug resistance genes studied did not influence the 5-year OS. Cox multivariate analysis did not demonstrate any factor independently correlated with 5-year OS.

DISCUSSION

The increasing use of chemotherapy in breast cancer has led physicians to develop accurate and reliable tests to identify MDR determinants in clinical studies. However, very limited data are available in the literature in this field and the precise mechanism of action, the relationship between multidrug resistance genes, and their clinical impact on the outcome of patients with breast cancer remain unclear, as published results have been discordant (Keith et al, 1990; Buser et al, 1997; Frassoldati et al, 1997; Silvestrini et al, 1997; Trock et al, 1997; Ferrero et al, 2000; Leonessa and Clarke, 2003). Few data are available concerning the impact of multidrug resistance genes on the clinical outcome of patients treated for breast cancer. This study was mainly designed to evaluate the clinical impact (DFS and OS) of MDR1, MRP1 and GSTP1 gene expression on the management of patients with breast cancer treated by adjuvant chemotherapy.

When the values were considered as continuous values, correlation studies did not reveal any statistically significant correlation between MDR1, MRP1, and GSTP1 expressions. In the previous study, published in 1998, based on a series of 74 patients, we observed a significant positive correlation between MRP1 and GSTpi expression (Lacave et al, 1998). This correlation was not confirmed in the present study, possibly because of a more scattered distribution of expression levels. Although GSH has been demonstrated to be necessary for MRP1-mediated cellular efflux of certain natural substances (Rappa et al, 1997) and although in vitro detoxification of anticancer agents involves a combined action of GSTs and MRPs (Morrow et al, 1998; O'Brien et al, 2000; Depeille et al, 2004; Depeille et al, 2005), a clear-cut correlation between MRP1 and GSTP1 expression has yet to be established in the clinical setting.

In this series, the 5-year DFS and OS were not influenced by the expression of either MDR1 or MRP1. In a series of 85 node-positive breast cancer patients receiving anthracycline-based adjuvant therapy, Ferrero et al (2000) did not find any significant influence of MDR1 and MRP1 on progression-free or overall specific survival, and Kanzaki et al (2001) did not observe any correlation between MRP1 mRNA expression and relapse after doxorubicin adjuvant therapy. In contrast, in a series of 59 breast cancer patients, Burger et al (2003) reported a clear link between RNA expression of lung resistance-related protein and MDR1, and progression-free survival, but this series included only advanced cases. In a recent publication based on 104 patients treated for breast cancer, higher MDR1/P-gp expression was associated with a statistically significant shorter OS and progression-free time, but the authors used a method based on immunohistochemical reactions using monoclonal antibodies (Surowiak et al, 2005). In a study of 27 patients, the risk of relapse in the 10 years following adjuvant chemotherapy was higher in patients whose primary tumours expressed higher levels of MRP1 mRNA (Ito et al, 1998). Heterogeneous results are a common feature of studies evaluating the expression and prognostic role of this gene, mainly due to both methodological and biological factors, and the prognostic impact of these two genes on DFS or OS remains to be established (Leonessa and Clarke, 2003).

The main result emerging from this study is that GSTP1 expression can be taken into account in the management of breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy.

In this study, we clearly demonstrated, on both univariate and multivariate Cox analysis, that subgroups based on GSTP1 expression were shown to be independent predictors of DFS, with a better 5-year DFS rate in the group of patients with high GSTP1 expression than in the group with low GSTP1 expression. This finding supports the results of previous studies concerning various type of tumours (Goasguen et al, 1996; Buser et al, 1997; Howells et al, 1998; Kearns et al, 2001). For example, Buser et al (1997), in a series of 89 women with untreated breast cancer, found that high levels of Gst and Gpx activities were associated with favourable clinical characteristics and a good prognosis, whereas low levels of Gst activity were associated with more aggressive or more advanced disease, although the results did not reach the limit of statistical significance. However, the results of our study are somewhat different from those reported by Buser et al. In our study, all patients had received adjuvant chemotherapy, whereas in Buser's study, only a small minority of patients had received adjuvant chemotherapy. The mean age of the population was also considerably higher in the study by Buser et al. This might explain why GSTP1 was found to be a significant prognostic factor on both univariate and multivariate analysis.

The precise molecular mechanism responsible for this phenomenon is unclear. As GSTP1 is the major GSTs consistently expressed in both normal and tumour breast tissue (Forester, Carcinogenesis 1990; 11: 2163–2170), it can be hypothesised that low GSTP1 expression would reduce the global activity of GSTs, and consequently reduce glutathione (GSH) consumption in GST-catalysed reactions, thereby leading to higher levels of GSH, which would block apoptosis and promote proliferation of tumour cells. This hypothesis was first proposed by Kearns et al (2001), who reported an association between elevated GSH levels in leukaemia cells and an increased risk of relapse in childhood acute lymphoid leukaemia. Morales et al (2005) recently confirmed these results, by showing that intracellular glutathione levels determine cell sensitivity to drug-induced apoptosis. It has also been demonstrated that intracellular GSH depletion of human oral squamous cell carcinoma by inorganic selenium compounds may cause caspase-9-mediated apoptosis (Takahashi et al, 2005).

A possible explanation for the increased DFS in patients with high levels of GSTP1 expression could involve the role of GSTP1 on cell proliferation. GSTP1 has been identified as a modulator of cell signaling, by interacting with and inhibiting c-Jun N terminal kinase (JNK) (Adler et al, 1999; Elsby et al, 2003) implicated in the control of cell proliferation (Timokhina et al, 1998; Tournier et al, 2000) and transformation (Raitano et al, 1995; Xiao and Lang, 2000). These results are consistent with the work by Ruscoe et al (2001), showing that GST-depleted cells, which exhibited a higher JNK activity, proliferated faster than their wild-type counterparts.

An hypothesis can be proposed to explain the molecular mechanisms responsible for higher levels of expression of GSTP1 in patients with better DFS, as the very variable levels of expression of GSTP1 cannot be explained by the presence of variant genotypes previously implicated in the pathogenesis of breast cancer in patients treated with chemotherapy (Yang et al, Cancer 2005; 103: 52–58), as these variants are mainly related to variations of enzyme catalytic activity (Sweeney, Cancer Res 2000; 60: 5621–5624). Complementary studies are currently underway to test this hypothesis, which was not included in the initial design of our study. Altered DNA methylation, related to the fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer (Jones and Baylin, 2002; Verma et al, 2004) now constitutes a growing field of clinical investigation in cancer (Das and Singal, 2004) and could possibly explain variable levels of GSTP1 expression in our patients. Altered DNA methylation has been well documented in breast cancer (for review see Widschwendter and Jones, 2002). In particular, inactivation of GSTP1 by promoter hypermethylation was initially reported to be frequent in renal carcinoma and in about 30% of primary breast cancers by Esteller et al (1998). Hypermethylation of CpG dinucleotides at the 5′ transcriptional regulatory region has been shown to be sufficient to inhibit GSTP1 transcription in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line when mediated by the methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD) protein MBD2 (Lin and Nelson, 2003). Jhaveri and Morrow (1998) previously showed that the GSTP1 CpG island is hypermethylated in ER-positive, GSTP1-nonexpressing MCF-7, but is undermethylated in ER-negative, GSTP1-expressing cell lines. Note that, in our study, both ER- and PR-negative patients exhibited higher levels of GSTP1 expression. In a recent study, Shinozaki showed that hypermethylation of GSTP1 was significantly associated with macroscopic sentinel lymph node metastasis compared to patients with microscopic or no sentinel lymph node (Shinozaki et al, 2005).

Most authors have studied the relevance of MDR phenotype as a predictive test for breast cancer response in patients treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and have found that MDR phenotype is indeed a relevant tool for monitoring breast cancer response to this treatment (Chevillard et al, 1996; Trock et al, 1997; Burger et al, 2003). In this study, we deliberately excluded patients who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy in order to obtain a homogeneous population. This subject will be further developed in a study to be published subsequently.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that a low level of GSTP1 gene expression is an independent predictive factor of poor 5-year DFS in patients treated by adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. MDR1, MRP1 did not show any significant influence on the prognosis of these patients.

References

- Adler V, Yin Z, Fuchs SY, Benezra M, Rosario L, Tew KD, Pincus MR, Sardana M, Henderson CJ, Wolf CR, Davis RJ, Ronai Z (1999) Regulation of JNK signaling by GSTp. EMBO J 18: 1321–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama S, Fojo A, Hanover JA, Pastan I, Gottesman MM (1985) Isolation and genetic characterization of human KB cell lines resistant to multiple drugs. Somat Cell Mol Genet 11: 117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck WT, Grogan TM, Willman CL, Cordon-Cardo C, Parham DM, Kuttesch JF, Andreeff M, Bates SE, Berard CW, Boyett JM, Brophy NA, Broxterman HJ, Chan HS, Dalton WS, Dietel M, Fojo AT, Gascoyne RD, Head D, Houghton PJ, Srivastava DK, Lehnert M, Leith CP, Paietta E, Pavelic ZP, Weinstein R (1996) Methods to detect P-glycoprotein-associated multidrug resistance in patients' tumors: consensus recommendations. Cancer Res 56: 3010–3020 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benard J, Da Silva J, De Blois MC, Boyer P, Duvillard P, Chiric E, Riou G (1985) Characterization of a human ovarian adenocarcinoma line, IGROV1, in tissue culture and in nude mice. Cancer Res 45: 4970–4979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennaceur-Griscelli A, Bosq J, Koscielny S, Lefrere F, Turhan A, Brousse N, Hermine O, Ribrag V (2004) High level of glutathione-S-transferase pi expression in mantle cell lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res 10: 3029–3034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boku N, Chin K, Hosokawa K, Ohtsu A, Tajiri H, Yoshida S, Yamao T, Kondo H, Shirao K, Shimada Y, Saito D, Hasebe T, Mukai K, Seki S, Saito H, Johnston PG (1998) Biological markers as a predictor for response and prognosis of unresectable gastric cancer patients treated with 5-fluorouracil and cis-platinum. Clin Cancer Res 4: 1469–1474 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonadonna G, Veronesi U, Brambilla C, Ferrari L, Luini A, Greco M, Bartoli C, Coopmans de Yoldi G, Zucali R, Rilke F (1990) Primary chemotherapy to avoid mastectomy in tumors with diameters of three centimeters or more. J Natl Cancer Inst 82: 1539–1545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger H, Foekens JA, Look MP, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Klijn JG, Wiemer EA, Stoter G, Nooter K (2003) RNA expression of breast cancer resistance protein, lung resistance-related protein, multidrug resistance-associated proteins 1 and 2, and multidrug resistance gene 1 in breast cancer: correlation with chemotherapeutic response. Clin Cancer Res 9: 827–836 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buser K, Joncourt F, Altermatt HJ, Bacchi M, Oberli A, Cerny T (1997) Breast cancer: pretreatment drug resistance parameters (GSH-system, ATase, P-glycoprotein) in tumor tissue and their correlation with clinical and prognostic characteristics. Ann Oncol 8: 335–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassevent A, Jourdan ML, Romain S, Descotes F, Colonna M, Martin PM, Bolla M, Spyratos F (2001) S-Phase Fraction and DNA Ploidy in 633 T1T2 breast cancers a standardized flow cytometric study. Clin Cancer Res 7: 909–917 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevillard S, Pouillart P, Beldjord C, Asselain B, Beuzeboc P, Magdelenat H, Vielh P (1996) Sequential assessment of multidrug phenotype and measurement of S-phase fraction as predictive markers of breast cancer response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer 77: 292–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SP, Sparks KE, Fraser K, Loe DW, Grant CE, Wilson GM, Deeley RG (1994) Pharmacological characterization of multidrug resistant MRP-transfected human tumor cells. Cancer Res 54: 5902–5910 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR (1972) Regression models and life tables. J R Statist Soc B 34: 187–220 [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KJ, Newkirk KA, Schumaker LM, Aldosari N, Rone JD, Haddad BR (2003) Glutathione S-transferase pi amplification is associated with cisplatin resistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines and primary tumors. Cancer Res 63: 8097–8102 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das PM, Singal R (2004) DNA methylation and cancer. J Clin Oncol 22: 4632–4642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Hamon Y, Chimini G (2001) The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. J Lipid Res 42: 1007–1017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depeille P, Cuq P, Mary S, Passagne I, Evrard A, Cupissol D, Vian L (2004) Glutathione S-transferase M1 and multidrug resistance protein 1 act in synergy to protect melanoma cells from vincristine effects. Mol Pharmacol 65: 897–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depeille P, Cuq P, Passagne I, Evrard A, Vian L (2005) Combined effects of GSTP1 and MRP1 in melanoma drug resistance. Br J Cancer 93: 216–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsby R, Kitteringham NR, Goldring CE, Lovatt CA, Chamberlain M, Henderson CJ, Wolf CR, Park BK (2003) Increased constitutive c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling in mice lacking glutathione S-transferase Pi. J Biol Chem 278: 22243–22249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott JA, Ling V (1989) The biochemistry of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance. Annu Rev Biochem 58: 137–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteller M, Corn PG, Urena JM, Gabrielson E, Baylin SB, Herman JG (1998) Inactivation of glutathione S-transferase P1 gene by promoter hypermethylation in human neoplasia. Cancer Res 58: 4515–4518 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandina G, Scambia G, Damia G, Tagliabue G, Fagotti A, Benedetti Panici P, Mangioni C, Mancuso S, D'Incalci M (1997) Glutathione S-transferase activity in epithelial ovarian cancer: association with response to chemotherapy and disease outcome. Ann Oncol 8: 343–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero JM, Etienne MC, Formento JL, Francoual M, Rostagno P, Peyrottes I, Ettore F, Teissier E, Leblanc-Talent P, Namer M, Milano G (2000) Application of an original RT-PCR-ELISA multiplex assay for MDR1 and MRP, along with p53 determination in node-positive breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer 82: 171–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frassoldati A, Adami F, Banzi C, Criscuolo M, Piccinini L, Silingardi V (1997) Changes of biological features in breast cancer cells determined by primary chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 44: 185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimberti S, Testi R, Guerrini F, Fazzi R, Petrini M (2003) The clinical relevance of the expression of several multidrug-resistant-related genes in patients with primary acute myeloid leukemia. J Chemother 15: 374–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goasguen JE, Lamy T, Bergeron C, Ly Sunaram B, Mordelet E, Gorre G, Dossot JM, Le Gall E, Grosbois B, Le Prise PY, Fauchet R (1996) Multifactorial drug-resistance phenomenon in acute leukemias: impact of P170-MDR1, LRP56 protein, glutathione-transferases and metallothionein systems on clinical outcome. Leuk Lymphoma 23: 567–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman MM, Pastan I (1993) Biochemistry of multidrug resistance mediated by the multidrug transporter. Annu Rev Biochem 62: 385–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells RE, Redman CW, Dhar KK, Sarhanis P, Musgrove C, Jones PW, Alldersea J, Fryer AA, Hoban PR, Strange RC (1998) Association of glutathione S-transferase GSTM1 and GSTT1 null genotypes with clinical outcome in epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res 4: 2439–2445 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Fujimori M, Nakata S, Hama Y, Shingu K, Kobayashi S, Tsuchiya S, Kohno K, Kuwano M, Amano J (1998) Clinical significance of the increased multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) gene expression in patients with primary breast cancer. Oncol Res 10: 99–109 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhaveri MS, Morrow CS (1998) Methylation-mediated regulation of the glutathione S-transferase P1 gene in human breast cancer cells. Gene 210: 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA, Baylin SB (2002) The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet 3: 415–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki A, Toi M, Nakayama K, Bando H, Mutoh M, Uchida T, Fukumoto M, Takebayashi Y (2001) Expression of multidrug resistance-related transporters in human breast carcinoma. Jpn J Cancer Res 92: 452–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan ES, Meier P (1958) Non parametric estimation from incomplete observations. Am Stat Assoc J 53: 457–480 [Google Scholar]

- Kearns PR, Pieters R, Rottier MM, Pearson AD, Hall AG (2001) Raised blast glutathione levels are associated with an increased risk of relapse in childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 97: 393–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith WN, Stallard S, Brown R (1990) Expression of mdr1 and gst-pi in human breast tumours: comparison to in vitro chemosensitivity. Br J Cancer 61: 712–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacave R, Coulet F, Ricci S, Touboul E, Flahault A, Rateau JG, Cesari D, Lefranc JP, Bernaudin JF (1998) Comparative evaluation by semiquantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of MDR1, MRP and GSTp gene expression in breast carcinomas. Br J Cancer 77: 694–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonessa F, Clarke R (2003) ATP binding cassette transporters and drug resistance in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 10: 43–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Nelson WG (2003) Methyl-CpG-binding domain protein-2 mediates transcriptional repression associated with hypermethylated GSTP1 CpG islands in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 63: 498–504 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales MC, Perez-Yarza G, Nieto-Rementeria N, Boyano MD, Jangi M, Atencia R, Asumendi A (2005) Intracellular glutathione levels determine cell sensitivity to apoptosis induced by the antineoplasic agent N-(4-hydroxyphenyl) retinamide. Anticancer Res 25: 1945–1951 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow CS, Smitherman PK, Diah SK, Schneider E, Townsend AJ (1998) Coordinated action of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) and multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1) in antineoplastic drug detoxification. Mechanism of GST A1-1- and MRP1-associated resistance to chlorambucil in MCF7 breast carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 273: 20114–20120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M, Meijer C, Zaman GJ, Borst P, Scheper RJ, Mulder NH, de Vries EG, Jansen PL (1994) Overexpression of the gene encoding the multidrug resistance-associated protein results in increased ATP-dependent glutathione S-conjugate transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 13033–13037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien M, Kruh GD, Tew KD (2000) The influence of coordinate overexpression of glutathione phase II detoxification gene products on drug resistance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 294: 480–487 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oudard S, Levalois C, Andrieu JM, Bougaran J, Validire P, Thiounn N, Poupon MF, Fourme E, Chevillard S (2002) Expression of genes involved in chemoresistance, proliferation and apoptosis in clinical samples of renal cell carcinoma and correlation with clinical outcome. Anticancer Res 22: 121–128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raitano AB, Halpern JR, Hambuch TM, Sawyers CL (1995) The Bcr-Abl leukemia oncogene activates Jun kinase and requires Jun for transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 11746–11750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappa G, Lorico A, Flavell RA, Sartorelli AC (1997) Evidence that the multidrug resistance protein (MRP) functions as a co-transporter of glutathione and natural product toxins. Cancer Res 57: 5232–5237 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscoe JE, Rosario LA, Wang T, Gate L, Arifoglu P, Wolf CR, Henderson CJ, Ronai Z, Tew KD (2001) Pharmacologic or genetic manipulation of glutathione S-transferase P1-1 (GSTpi) influences cell proliferation pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 298: 339–345 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl SM, Fourquet A, Asselain B, Pierga JY, Vilcoq JR, Durand JC, Dorval T, Palangie T, Jouve M, Beuzeboc P (1994) Neoadjuvant vs adjuvant chemotherapy in premenopausal patients with tumours considered too large for breast conserving surgery: preliminary results of a randomised trial: S6. Eur J Cancer 30: 645–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki M, Hoon DS, Giuliano AE, Hansen NM, Wang HJ, Turner R, Taback B (2005) Distinct hypermethylation profile of primary breast cancer is associated with sentinel lymph node metastasis. Clin Cancer Res 11: 2156–2162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestrini R, Veneroni S, Benini E, Daidone MG, Luisi A, Leutner M, Maucione A, Kenda R, Zucali R, Veronesi U (1997) Expression of p53, glutathione S-transferase-pi, and Bcl-2 proteins and benefit from adjuvant radiotherapy in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 89: 639–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon SM, Schindler M (1994) Cell biological mechanisms of multidrug resistance in tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 3497–3504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soule HD, Vazguez J, Long A, Albert S, Brennan M (1973) A human cell line from a pleural effusion derived from a breast carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 51: 1409–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoehlmacher J, Park DJ, Zhang W, Groshen S, Tsao-Wei DD, Yu MC, Lenz HJ (2002) Association between glutathione S-transferase P1, T1, and M1 genetic polymorphism and survival of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 94: 936–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surowiak P, Materna V, Matkowski R, Szczuraszek K, Kornafel J, Wojnar A, Pudelko M, Dietel M, Denkert C, Zabel M, Lage H (2005) Relationship between the expression of cyclooxygenase 2 and MDR1/P-glycoprotein in invasive breast cancers and their prognostic significance. Breast Cancer Res 7: 862–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Sato T, Shinohara F, Echigo S, Rikiishi H (2005) Possible role of glutathione in mitochondrial apoptosis of human oral squamous cell carcinoma caused by inorganic selenium compounds. Int J Oncol 27: 489–495 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timokhina I, Kissel H, Stella G, Besmer P (1998) Kit signaling through PI 3-kinase and Src kinase pathways: an essential role for Rac1 and JNK activation in mast cell proliferation. EMBO J 17: 6250–6262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournier C, Hess P, Yang DD, Xu J, Turner TK, Nimnual A, Bar-Sagi D, Jones SN, Flavell RA, Davis RJ (2000) Requirement of JNK for stress-induced activation of the cytochrome c-mediated death pathway. Science 288: 870–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trock BJ, Leonessa F, Clarke R (1997) Multidrug resistance in breast cancer: a meta-analysis of MDR1/gp170 expression and its possible functional significance. J Natl Cancer Inst 89: 917–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma M, Maruvada P, Srivastava S (2004) Epigenetics and cancer. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 41: 585–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widschwendter M, Jones PA (2002) DNA methylation and breast carcinogenesis. Oncogene 21: 5462–5482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Lang W (2000) A dominant role for the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase in oncogenic ras-induced morphologic transformation of human lung carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 60: 400–408 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]