Abstract

Limited information on salvage treatment in patients affected by pancreatic cancer is available. At failure, about half of the patients present good performance status (PS) and are candidate for further treatment. Patients >18 years, PS ⩾50, with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma previously treated with gemcitabine-containing chemotherapy, and progression-free survival (PFS) <12 months received a combination of raltitrexed (3 mg m−2) and oxaliplatin (130 mg m−2) every 3 weeks until progression, toxicity, or a maximum of six cycles. A total of 41 patients received 137 cycles of chemotherapy. Dose intensity for both drugs was 92% of the intended dose. Main grade >2 toxicity was: neutropenia in five patients (12%), thrombocytopenia, liver and vomiting in three (7%), fatigue in two (5%). In total, 10 patients (24%) yielded a partial response, 11 a stable disease. Progression-free survival at 6 months was 14.6%. Median survival was 5.2 months. Survival was significantly longer in patients with previous PFS >6 months and in patients without pancreatic localisation. A clinically relevant improvement of quality of life was observed in numerous domains. Raltitrexed–oxaliplatin regimen may constitute a treatment opportunity in gemcitabine-resistant metastatic pancreatic cancer. Previous PFS interval may allow the identification of patients who are more likely to benefit from salvage treatment.

Keywords: chemotherapy, metastatic disease, oxaliplatin, pancreatic cancer, raltitrexed, salvage therapy

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma has a dismal prognosis due to early metastatic dissemination even in patients submitted to surgery with radical intent. As a consequence, effective systemic treatment has a strategic role in the therapeutic management of this disease. Unfortunately, very few agents have demonstrated any activity with reproducible response rates greater than 15%. While randomised studies have suggested that chemotherapy is superior to best supportive care in prolonging survival and improving symptoms in patients with advanced disease (Glimelius et al, 1996), standard single agent gemcitabine yields a marginal impact on disease outcome. Median progression-free survival (PFS) with this agent is approximately 3 months (Burris et al, 1997; Bramhall et al, 2001, 2002; Berlin et al, 2002; Moore et al, 2003; Rocha Lima et al, 2004; Van Cutsem et al, 2004; Reni et al, 2005), and <15% of patients are PF at 6 months (PFS-6) from diagnosis (Reni et al, 2005). Approximately half of the patients failing previous treatment present good performance status (PS) and are willing to undergo further treatment. However, very limited information concerning the impact of salvage treatment upon survival and quality of life is available. This patient population represents the target for experimental trials aimed at broadening the chemotherapeutic armamentarium. Raltitrexed (Tomudex® AstraZeneca S.p.A., Ben Venue Laboratories Inc., Bedford, OH, USA) is a thymidylate synthase inhibitor that is easily transported in the cell, where it undergoes extensive polyglutamation within the cells, which extends the intracellular retention, increases concentration, and ultimately leads to increased cytotoxicity. Raltitrexed blocks the production of thymidine monophosphate from deoxyuridine monophosphate in a reaction-specific manner. Oxaliplatin (Eloxatin®, Sanofi-Synthelabo S.p.A, Milan, Italy), a third-generation platinum analogue, is a diaminocyclohexane platinum that forms interstrand DNA adducts, which differ from those formed by cisplatin or carboplatin in their capability to overcome resistance mechanisms. Preclinical studies suggested that pancreatic cancer cell lines are highly sensitive towards raltitrexed and oxaliplatin even in gemcitabine- and 5-fluorouracil-resistant cells (Kornmann et al, 2000; Monti et al, 2004), and that oxaliplatin yields an addictive antitumour activity when combined with raltitrexed or other thymidylate synthase inhibitors (Raymond et al, 1998), thus encouraging the use of these two drugs in experimental protocols as salvage treatment (Monti et al, 2004). Furthermore, raltitrexed and oxaliplatin have a noncrossresistant mode of action, differential toxicity profiles, and can be used in combination as outpatient therapy in the same doses as for single agent use (Fizazi et al, 2000).

Raltitrexed-oxaliplatin (TOM-OX) combination has been assessed in colorectal cancer and mesothelioma yielding elevated tumour control rates in 5-fluorouracil or cisplatin pretreated patients (Cascinu et al, 2002; Seitz et al, 2002). Single agent raltitrexed obtained 5% partial response (PR) and 29% stable disease (SD) in 42 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma (Pazdur et al, 1996).

A multicentre phase II trial was undertaken to determine the activity and safety of TOM-OX combination as salvage treatment in gemcitabine-resistant metastatic pancreatic cancer.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient population

Patients aged >18 years with histologically or cytologically proven metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma, with at least one bidimensionally measurable target lesion were eligible for this study. Patients were to have received previous gemcitabine-containing chemotherapy. No definition of gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer exists and no other trial has used this eligibility criterion. Thus, in the absence of benchmarks to which to refer, it was arbitrarily decided to include only those patients in whom progression occurred <12 months from the start of treatment (i.e. <6 months from treatment conclusion) as it was deemed unlikely that these patients could achieve relevant benefit with further gemcitabine administration. Other inclusion criteria were: Karnofsky PS⩾50, adequate bone marrow (absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ⩾1500 cells mm−3, platelet count ⩾100 000 cells mm−3, and haemoglobin ⩾10 g dl−1); kidney function (creatinine clearance ⩾65 ml min−1) and liver function (serum total bilirubin ⩽2 mg dl−1, alkaline phosphatase and serum transaminases ⩽three times the upper limit of normal (ULN)). Patients with prior malignancy were ineligible for the study, with the exception of those who had had basal-cell carcinoma of the skin, carcinoma in situ of the cervix, or other cancer for which the patient had been disease free for at least 5 years. Patients with ampullary tumours or other histologic variants of pancreatic carcinoma were ineligible. The study was reviewed and approved by each local Ethics Committee of the participating institutions and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participating patients were required to provide written informed consent.

Treatment plan

Raltitrexed was diluted in 5% dextrose and given as 15 min intravenous (i.v.) infusion at 3 mg m−2. After a 45 min interval, oxaliplatin was administered in at least 2 h i.v. infusion at 130 mg m−2. Patients were systematically given prophylactic antiemetic treatment with 5-HT3 antagonists. Cycles were repeated every 3 weeks until PD, unacceptable toxicity, patient's or physician's decision, or a maximum of six cycles. Dose adjustments were made according to the greatest degree of toxicity. In the case of ANC <1500 cells mm−3, of platelet count <100 000 cells mm−3, or of ⩾grade 3 nonhaematological toxicity, on the first day of the next cycle, the treatment was withheld until recovery and then restarted with dose for the drug responsible for nonhaematological toxicity reduced by 25%. If recovery was not evident within 2 weeks, the patient was discontinued from the study. If grade 3 or grade 4 haematological toxicity occurred, doses for both drugs were reduced by 25% or by 50%, respectively. Treatment was discontinued in cases of grade 4 haematological toxicity associated with grade 3 gastro-intestinal toxicity. If grade 2 or grade 3 gastro-intestinal toxicity occurred, raltitrexed dose was to be reduced by 25% or by 50%, respectively. Treatment was discontinued in cases of grade 4 gastro-intestinal toxicity. In cases of decreased creatinine clearance, raltitrexed was administered every 4 weeks at 75% (55–65 ml min−1) or 50% (25–54 ml min−1) of the original dose. Raltitrexed was discontinued if creatinine clearance fell below 25 ml min−1. The oxaliplatin dose was to be reduced to 100 mg m−2 in cases of paraesthesia or dysesthesia with pain or functional impairment lasting >7 days, to 80 mg m−2 for persistent paraesthesia or dysesthesia between two cycles without functional impairment, or discontinued in cases with persistent paraesthesia or dysesthesia between two cycles with functional impairment.

Study evaluations

Pretreatment evaluation consisted of PS assessment, haematological and biochemical profiles, CA 19-9 analysis, spiral computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen, and the chest or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). During treatment, blood chemistry, creatinine clearance, and CA 19-9 analysis was performed on day 14, whereas haematological profile was repeated on day 1 of every cycle. Imaging studies, employing the same method used to measure the initial target, were repeated every two treatment cycles to assess objective response. At the end of chemotherapy, CA 19-9 analysis was performed every 40–50 days, and imaging studies were repeated every 2–3 months, when an increase of CA 19-9 was observed, or when PD was suspected. The EORTC QLQ-C30 (Aaronson et al, 1993) and PAN26 (Fitzsimmons et al, 1999) questionnaires for quality of life (QOL) assessment were given to patients at study entry and every second cycle of chemotherapy, until PD.

Outcome measures

Side effects were graded according to the Common Toxicity Criteria defined by the NCI (US), extended by the NCIC (Canada) version 2.0 (Ajani et al, 1990). The objective tumour response to treatment was assessed according to the WHO criteria on the basis of a maximum of three ‘target lesions’ selected before the start of the treatment. All scans were centrally reviewed by one expert radiologist. The duration of complete response was defined as the time between the first documentation of complete disease resolution and the first documented observation of PD. The duration of PR was defined as the time between the initiation of treatment and the time of PD. The PFS was defined as the interval between the initiation of treatment and the occurrence of PD. Survival (OS) was measured from the initiation of treatment to the date of death for any reason or to the last follow-up assessment. The QOL was assessed using the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire (Aaronson et al, 1993) supplemented by the pancreatic cancer module (EORTC QLQ-PAN-26) (Fitzsimmons et al, 1999). Differences >10 points on the transformed scales were regarded as clinically significant (Osoba et al, 1998). Mean scale and items scores were transformed to a 0–100 scale, as described in the EORTC scoring manual (Fayers et al, 2001). To be assessable for QOL, patients had to have a baseline QOL assessment and at least one subsequent QOL assessment. The numbers of patients in each analysis may differ from scale to scale as some patients may have had randomly missing scores on certain scales.

Statistical analysis

The primary end point of this trial was to assess the objective response rate of TOM-OX in gemcitabine-resistant metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Secondary end points were PFS, OS, toxicity, response duration, and QOL. The Simon Minimax two-stage design was used. The maximum response rate considered of low interest was 10% and the minimum response rate considered of interest was 25%. The sample size was calculated with a type I error of 10% and a test power of 90%. Early discontinuation of the study was planned in the case of <3 responses in the first 27 patients. Alternatively, the target enrollment was estimated to be 40 patients. TOM-OX would be considered an active regimen in this patient population if >6 responses were noted among the 40 enrolled patients. All the statistical analyses were performed on the intention-to-treat population. The survivor functions curves were estimated according to the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. All the probability values were from two-sided tests. Analyses were carried out using the Statistica 4.0 statistical package for Windows (1993 Statsoft, Tulsa, OK, USA).

Funding source

Raltitrexed and oxaliplatin were supplied gratuitously by Astra-Zeneca, Italy and Sanofi-Synthelabo, Italy. No funding sources supported the work.

RESULTS

Patient population

Between December 2002 and March 2004, 41 patients were entered into this trial. The characteristics of the patient population are listed in Table 1. Previous PFS, which was calculated as the interval between the initiation of latest chemotherapy treatment and the occurrence of PD, was 1–11.5 months (median 6). With regard to previous treatment, 16 of 18 patients submitted to surgery with curative intent received postoperative chemotherapy, which was followed by radiotherapy in 10 cases, while two patients were submitted to postoperative chemoradiation and received gemcitabine at the time of first recurrence. Two of the 23 patients who did not receive prior surgery were irradiated. Among 35 patients receiving a single prior chemotherapy, treatment consisted of gemcitabine alone in 17 patients, PEFG (cisplatin, epirubicin, 5-fluorouracil, gemcitabine) regimen (Reni et al, 2005) in 16 patients, gemcitabine plus cisplatin or 5-fluorouracil in one case each. Among six patients receiving either two (n=5) or three (n=1) prior chemotherapy lines, first-line treatment consisted of gemcitabine in all cases and was followed as second-line treatment by PEFG regimen (n=5) or 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid (n=1); one patient also received mitomycin-C after gemcitabine and PEFG regimen, as third-line treatment. In total, 26 patients had PD during previous chemotherapy, and 15 had an interval <5 months between the end of previous therapy and PD.

Table 1. Patient characteristics at baseline.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Patients enrolled | 41 |

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 61 |

| Range | 25–80 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 23 (56) |

| Female | 18 (44) |

| Karnofsky PS | |

| 70–80 | 16 (39) |

| 90–100 | 25 (61) |

| Site of metastases | |

| Liver | 33 (80) |

| Lymphnodes | 8 (20) |

| Lung | 12 (29) |

| Peritoneum | 5 (12) |

| Number of metastatic lesions | |

| 1 | 1 (2) |

| 2–5 | 24 (59) |

| >5 | 16 (39) |

| Prior therapy | |

| Prior pancreatic surgery | 18 (44) |

| Prior radiotherapy | 14 (34) |

| Prior chemotherapy lines | |

| n=1 | 35 (85)* |

| n>1 | 6 (15) |

| *Gemcitabine alone | 17 (49) |

| *Combination | 18 (51) |

PS=performance status; n=number.

In all, 35 patients received 1 prior chemotheraphy line. Of those, 17 received Gemcitabine alone and 18 received a combination chemotherapy.

Treatment summary and toxicity

A total of 137 cycles were delivered. Total number of cycles per patient is reported in Table 2. In all, 13 (32%) patients received six cycles, while 28 discontinued treatment due to radiologically confirmed PD (16), clinical PD without radiological assessment (five), patient or medical decision (five), persistent thrombocytopenia (one), and death of heart failure (one). Dose intensity was 92% for both drugs. The mean interval between cycles was 22.8 days. The start of a new cycle was delayed by 7–14 days in 18 cycles (13%) due to persistent neutropenia (n=6) or thrombocytopenia (n=1), fever (n=1), liver toxicity (n=2), bowel subocclusive status (n=1), delay in CT scan reassessment (n=2), patient or medical decision (n=5). Raltitrexed dose was reduced in five (12%) patients either by 50% due to G3 vomiting (n=1) or by 25% due to grade 2 liver toxicity (n=1) or fatigue (n=3). Oxaliplatin dose was reduced in four (10%) patients by 25% due to G3 liver toxicity (n=1), G2 liver toxicity, or fatigue (n=1 each).

Table 2. Treatment summary.

| Number of cycles | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| 1 | 6 |

| 2 | 18 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 |

| 5 | 2 |

| 6 | 13 |

Table 3 summarises the main side effects observed. One patient died on day 1 of the third cycle due to heart failure. Febrile neutropenia, or non-neutropenic infections were not observed.

Table 3. Treatment-related toxicity per cycle (and worst ever by patient).

| Toxicity | Grade 0 | Grade 1/2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | NA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granulocytes | 66 (63) | 22 (22) | 3 (5) | 3 (7) | 6 (2) |

| Platelets | 70 (61) | 22 (29) | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Haemoglobin | 39 (29) | 54 (66) | 1 (2) | 0 | 6 (2) |

| Stomatitis | 98 (93) | 2 (7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 61 (46) | 36 (46) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Diarrhoea | 90 (76) | 9 (22) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Neurologic | 81 (68) | 19 (32) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 72 (49) | 27 (46) | 2 (5) | 0 | 0 |

| Liver (GOT/GPT) | 62 (49) | 30 (41) | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Liver (GGT/Alk.P) | 88 (83) | 5 (12) | 1 (2) | 0 | 6 (2) |

| Fever | 92 (80) | 8 (20) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kidney | 98 (93) | 2 (7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Numbers are expressed as percentages. NA=not available.

Response and survival

Table 4 summarises the outcome measures. The central radiology independent review showed 10 PR (24%; 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 11–37%), 11 SD (27%; 95% CI 13–41%), 15 PD (37%; 95% CI 22–52%), while five patients (12%; 95% CI 2–22%) discontinued chemotherapy before tumour assessment due to clinical PD. Median duration of PR was 5.6 months (interquartile range: 4.3–6.4 months) and five of 10 patients with PR were PF at 6 months. Median duration of SD was 4.0 months (interquartile range 3.1–4.5 months) and one of 11 patients with SD was PF at 6 months. Of 35 patients, 13 (37%; 95% CI 20–54%) with elevated CA19.9 basal value had a marker reduction of >50% during treatment.

Table 4. Activity and efficacy analyses summary.

|

Best response

|

Outcome measures

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous treatment | PR | SD | PFS-6 | OS-12 |

| All patients (n=41) | 10 (24.4%) | 11 (26.8%) | 6 (14.6%) | 5 (12.2%) |

| PEFG (n=16) | 3 (18.7%) | 6 (37.5%) | 3 (18.8%) | 4 (25.0%) |

| G (n=17) | 5 (29.4%) | 4 (23.5%) | 2 (11.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| G → PEFG (=5) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| F including | ||||

| y (n=23) | 5 (21.7%) | 7 (30.4%) | 4 (17.4%) | 5 (21.7%) |

| n (n=18) | 5 (27.8%) | 4 (22.2%) | 2 (11.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| P including | ||||

| y (n=22) | 3 (13.6%) | 7 (31.8%) | 3 (13.6%) | 4 (18.2%) |

| n (n=19) | 7 (36.8%) | 4 (21.1%) | 3 (15.8%) | 1 (5.3%) |

| n of lines | ||||

| 1 (n=35) | 9 (25.7%) | 10 (28.6%) | 6 (17.1%) | 5 (14.3%) |

| >1 (n=6) | 1 (16.6%) | 1 (16.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

n=number; PR=partial response; SD=stable disease; PFS-6=progression-free at 6 months; OS-12=alive at 12 months; P=cisplatin; E=epirubicin; F=5-fluorouracil; G=gemcitabine; y=yes; n=no; → =followed by.

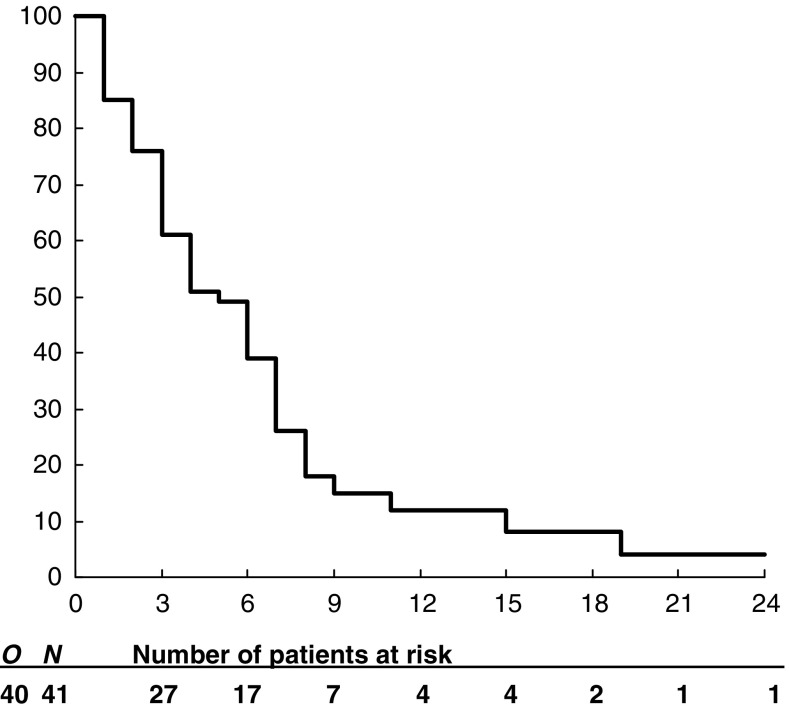

All patients, apart from one dying from heart failure while PF, had PD. In the five patients without radiological documentation of PD, PFS was calculated as the interval between treatment initiation and death. Median and 6-month PFS was 1.8 months (interquartile range: 1.2–4.5 months) and 14.6% (95% CI 4.6–24.6%; Table 4). A total of 40 patients died. One is alive at 29 months. Median and 1-year OS was 5.2 months (interquartile range: 2.3–7.5 months) and 12.2% (95% CI 2.2–22.2%; Figure 1; Table 4), respectively. Median survival for patients with PR, SD, and PD was 7.4, 6.8, and 2.5 months, respectively. Median survival was 2.9 months for 22 patients without CA19.9 reduction and 7.4 months for 13 patients with CA19.9 reduction >50% (P=0.006).

Figure 1.

Overall survival. N=number of eligible patients. O=total number of events at the final analysis. Subsequent numbers are the number of patients at risk.

Quality of life

At baseline, questionnaires were completed by 29 patients (71%). Two of those had PD after the first cycle, while three patients completed only baseline questionnaires. Thus, 24 patients (59%) were assessable for QOL analysis. In this subset of patients, a clinically significant improvement in QOL relative to baseline was observed in health-care satisfaction (50%), body image (42%), fear for future health (40%), pain (39%), sexuality, digestive symptoms (33%), QOL 1 and 2 (30–35%), altered bowel habit and cachexia (30%), cognitive functioning, hepatic symptoms, pancreatic pain (29%), physical functioning, fatigue (26%), nausea, and appetite loss (24%).

Exploratory analyses

As the aim of salvage treatment in metastatic pancreatic cancer is palliative, exploratory analyses of the impact of TOM-OX on OS in subgroups of patients were performed in an attempt to identify those who could receive the greatest benefit from treatment (significance level after multiple comparison adjustment: 0.0036). Previous chemotherapy including 5-fluorouracil or cisplatin did not reduce the probability to be PF at 6 months or alive at 12 months after TOM-OX (Table 4). When considering patients who received only one prior chemotherapy line, no significant difference in OS was observed among 16 patients previously treated by PEFG when compared to 17 patients treated by gemcitabine alone (1-year OS 25.0 vs 0%; P=0.018). A summary of univariate and multivariate analyses of the relationship between OS and patient-, treatment-, and tumour-related variables is reported in Table 5. Overall survival was significantly longer in patients with previous PFS ranging between 6.1 and 12 months relative to those with shorter PFS and in patients without pancreatic localisation. A trend towards longer OS was observed in patients submitted to previous surgery. A multivariate analysis by the Cox proportional hazard model confirmed that previous PFS and pancreatic localisation were significantly predictive of survival (Table 5).

Table 5. Exploratory analyses summary.

|

Univariate

|

Multivariate

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Subgroups | No. of patients | 1 year OS (%) | P | HR | 95% CI | P |

| PFS | <6 months | 22 | 0.0 | ||||

| ⩾6 months | 19 | 21.1 | 0.0035 | 4.27 | 1.56–11.67 | 0.007 | |

| Surgery | Yes | 18 | 22.2 | ||||

| No | 23 | 0.0 | 0.0049 | 2.26 | 0.48–10.79 | 0.31 | |

| CHT lines | 1 | 6 | 11.4 | ||||

| >1 | 35 | 0.0 | 0.1278 | 1.49 | 0.38–5.83 | 0.58 | |

| Age | ⩽60 | 19 | 15.8 | ||||

| >60 | 22 | 4.5 | 0.3362 | 1.27 | 0.50–3.21 | 0.62 | |

| Gender | Male | 23 | 17.4 | ||||

| Female | 18 | 0.0 | 0.0296 | 0.52 | 0.23–1.19 | 0.13 | |

| PS | 90–100 | 25 | 12.0 | ||||

| 70–80 | 16 | 6.2 | 0.2882 | 1.29 | 0.49–3.38 | 0.61 | |

| Radiotherapy | Yes | 14 | 11.1 | ||||

| No | 27 | 7.1 | 0.3601 | 0.78 | 0.34–1.80 | 0.56 | |

| No. of lesions | 2–5 | 24 | 4.2 | ||||

| >5 | 16 | 18.8 | 0.4529 | 0.62 | 0.18–2.12 | 0.45 | |

| Site: liver | Yes | 33 | 9.1 | ||||

| No | 8 | 12.5 | 0.4891 | 0.96 | 0.32–2.88 | 0.94 | |

| Site: lung | Yes | 12 | 16.7 | ||||

| No | 29 | 6.9 | 0.4457 | 1.06 | 0.31–3.58 | 0.93 | |

| Site: pancreas | Yes | 26 | 0.0 | ||||

| No | 15 | 26.7 | 0.0011 | 8.46 | 1.34–53.4 | 0.03 | |

| Site: peritoneum | Yes | 5 | 0.0 | ||||

| No | 36 | 11.1 | 0.3860 | 0.37 | 0.08–1.76 | 0.22 | |

| No. of sites | 1 | 7 | 42.9 | ||||

| >1 | 34 | 2.9 | 0.0080 | 0.70 | 0.14–3.42 | 0.66 | |

No.=number; CHT=chemotherapy; PFS=progression-free survival; OS=overall survival; PS=performance status; HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

The present trial showed that TOM-OX regimen was feasible, had limited toxicity and relevant activity in patients with gemcitabine-resistant metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and may constitute a treatment opportunity in this setting. It is noteworthy that this regimen was also active in patients with 5-fluorouracil- or cisplatin-resistant disease. Until a decade ago, the use of chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer was believed to have no role in the routine treatment of patients with advanced disease (Lionetto et al, 1995). A few options are currently available for first-line treatment (Burris et al, 1997; Moore et al, 2005; Reni et al, 2005). However, gemcitabine-based chemotherapy yields a very limited disease control, and progression usually occurs within a few months after starting first-line treatment. As no further standard therapeutic option exists and scarce information on the impact on outcome of salvage therapy is available, prospective trials attempting to widen the therapeutic armamentarium against this disease are warranted. So far, very few studies have investigated salvage chemotherapy after failure of gemcitabine or gemcitabine-containing chemotherapy (Stehlin et al, 1999; Oettle et al, 2000; Ulrich-Pur et al, 2003; Cantore et al, 2004; Milella et al, 2004; Reni et al, 2004), one of which was retrospective (Kozuch et al, 2001). The populations selected were different in terms of proportion of patients with PS>80, which ranged from 0 to 61%, metastatic patients (73–100%), patients with liver metastases (57–85%), patients with >1 prior chemotherapy lines (0–29%), and median PFS after previous treatment (6.0–7.9 months), which was rarely reported in other series, while in our exploratory analyses it resulted as an independent factor predicting the outcome of salvage therapy (Table 6). Furthermore, the sample size of most series is limited to <20 patients per treatment arm (Oettle et al, 2000; Ulrich-Pur et al, 2003; Milella et al, 2004; Reni et al, 2004), thus producing data with very large CIs. Given these differences, the lack of information on important prognostic factors, and other potential bias related to phase II trial design, results are difficult to compare across trials, especially in terms of survival. Activity observed in the current trial (PR: 24%) was consistent with the response rate of 16–35% previously reported with other active regimens (Kozuch et al, 2001; Ulrich-Pur et al, 2003; Milella et al, 2004) and compares favourably with the 0–10% objective responses reported elsewhere (Stehlin et al, 1999; Oettle et al, 2000; Ulrich-Pur et al, 2003; Cantore et al, 2004; Reni et al, 2004). The median PFS of 1.8 months observed with TOM-OX regimen was slightly shorter than the median PFS of 1.7–4.1 months reported in other series (Stehlin et al, 1999; Oettle et al, 2000; Kozuch et al, 2001; Ulrich-Pur et al, 2003; Cantore et al, 2004; Milella et al, 2004; Reni et al, 2004). However, it is likely that this depended on the timing of radiographic assessment, which was performed more frequently in the current trial and was therefore more prone to intercept early PD. Consistently, PFS-6 was identical in our series and in the retrospective series which had previously obtained the longest median PFS among published series (Kozuch et al, 2001). With regard to grade 3–4 toxicity, neutropenia (12%), nausea/vomiting (7%), and liver enzymes increase (7%) observed in our series were within the range reported with other regimens (5–38, 3–14, and 5–13%, respectively). Fatigue (5%) was reported in a single series (10% (Reni et al 2004)). Diarrhoea (2%) was observed less often relative to other series (3–10%). Of note, less toxicity was observed in our series relative to TOM-OX when administered to patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (Cascinu et al, 2002; Seitz et al, 2002), namely, 17–33% liver toxicity, 10–30% neutropenia, 5–13% nausea-vomiting, 11–16% fatigue, and 7–17% diarrhoea were reported in metastatic colorectal cancer (Cascinu et al, 2002; Seitz et al, 2002). The differences in toxicity may reflect different selection of patients (e.g. in terms of PS) and may suggest that toxicity profile could be different in different tumour sites. As the aim of salvage therapy in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer is purely palliative, some concern could be raised that the improvement in clinical outcome is not achieved at the cost of impaired QOL. Clinical benefit response was proposed to address this issue (Burris et al, 1997). However, this measure was not validated and has been criticised for using selected variables that do not reflect QOL (Hoffman and Glimelius, 1998). Thus, we preferred a more reliable and validated measure, such as the EORTC QLQ questionnaire. No data to which to compare the present findings are available in the literature. Raltitrexed–oxaliplatin regimen yielded a clinically significant improvement relative to baseline in a large proportion of patients in several QOL domains, including most of the important symptoms that are frequently associated with pancreatic cancer.

Table 6. Results of salvage therapy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

| Ref | No. of pts | Treatment | m. age | PS 0 | M (%) | liver M (%) | >1CHT (%) | PPFS | ORR (%) | mPFS | PFS-6 (%) | 1 year OS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 30 | I+E | 60 | 30 | 100 | 60 | 23 | Nr | 10 | 4.1 | Nr | 23 |

| 15a | 34 | G-FLIP | 64 | Nr | 100 | 85 | 29 | Nr | 24 | 3.9 | 20 | 20 |

| 17 | 17 | F+celecoxib | 60 | 35 | 82 | Nr | 0 | Nr | 35 | 1.9 | 6 | 20 |

| 21 | 18 | T | 59 | Nr | 100 | Nr | 22 | 7.9 | 5.5 | 3.3 | Nr | Nr |

| 26 | 15 | MDI | 61 | 26 | 100 | 60 | 20 | Nr | 0 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 |

| 29 | 33 | Ru | 62 | 0 | 73 | 57 | Nr | Nr | 9 | Nr | Nr | 6 |

| 30 | 19 | R | 60 | 21 | 100 | 74 | 0 | Nr | 0 | 2.5 | Nr | 0 |

| 30 | 19 | R+I | 63 | 21 | 100 | 63 | 0 | Nr | 16 | 4.0 | Nr | 22 |

| cs | 41 | R+E | 61 | 61 | 100 | 80 | 15 | 6.0 | 24 | 1.8 | 15 | 12 |

Ref=reference; No. of pts=number of patients; m. age=median age; PS 0=performance status=0 (ECOG) or 90–100 (Karnofsky); M=metastatic; CHT=% of patients with >1 previous chemotherapy lines; PPFS=previous progression-free survival; ORR=objective response rate; m PFS=median progression-free survival; PFS-6=progression-free survival at 6 months; 1 year OS=overall survival at 1 year; cs=current series; I=irinotecan; E=eloxatin; G=gemcitabine; F=5-fluorouracil; L=leucovorin; P=cisplatin; T=paclitaxel; M=mitomycin; D=docetaxel; Ru=rubitecan; R=raltitrexed; Nr=not reported.

Retrospective.

Altogether, a median overall survival of 3.5–10 months and median PFS of 2–4 months was achieved with active salvage therapy. It is of note that 12–23% patients with metastatic disease are alive at 1 year from salvage treatment start (current series, Kozuch et al, 2001; Ulrich-Pur et al, 2003; Cantore et al, 2004; Milella et al, 2004). These figures are similar to those observed after gemcitabine in the first-line setting. While a bias in favour of salvage therapy due to better selection of patients cannot be ruled out, these data suggest that an appropriately selected subset of patients, for example, on the basis of previous PFS, with gemcitabine-refractory disease may yield a relevant clinical and survival benefit from further treatment. This hypothesis should be tested in a phase III trial against best supportive care.

Footnotes

A summary of the data presented in this manuscript was selected for poster presentation at the 2005 Annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Oncology and was published as part of the proceedings.

References

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC, Kaasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rofe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Study Group (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality of life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 2: 319–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajani JA, Welch SR, Raber MN, Fields WS, Krakoff IH (1990) Comprehensive criteria for assessing therapy-induced toxicity. Cancer Invest 8: 147–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin JD, Catalano P, Thomas JP, Kugler JW, Haller DG, Benson III AB (2002) Phase III study of gemcitabine in combination with fluorouracil vs gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial E2297. J Clin Oncol 20: 3270–3275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramhall SR, Rosemurgy A, Brown PD, Bowry C, Buckels JA, for the Marimastat Pancreatic Cancer Study Group (2001) Marimastat as first-line therapy for patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 19: 3447–3455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramhall SR, Schultz J, Nemunaitis J, Brown PD, Baillet M, Buckels JAC (2002) A double-blind placebo-controlled, randomised study comparing gemcitabine and marimastat with gemcitabine and placebo as first line therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 87: 161–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris III HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P, Nelson R, Dorr FA, Stephens CD, Von Hoff DD (1997) Improvement in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 15: 2403–2413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantore M, Rabbi C, Fiorentini G, Oliani C, Zamagni D, Iacono C, Mambrini A, Del Freo A, Manni A (2004) Combined irinotecan and oxalipatin in patients with advanced pre-treated pancreatic cancer. Oncology 67: 93–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascinu S, Graziano F, Ferraù F, Catalano V, Massacesi C, Santini D, Silva RR, Barni S, Zaniboni A, Battelli N, Siena S, Giordani P, Mari D, Baldelli AM, Antognoli S, Maisano R, Priolo D, Pessi MA, Tonini G, Rota S, Labianca R (2002) Raltitrexed plus oxaliplatin (TOMOX) as first-line chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. A phase II study of the Italian Group for the Study of Gastrointestinal Tract Carcinomas (GISCAD). Ann Oncol 13: 716–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayers P, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, Curran D, Groenvold M (2001) EORTC QLQ Scoring Manual, 3rd edn. Brussels, Belgium: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimmons D, Johnson CD, George S, Payne S, Sandberg AA, Bassi C, Beger HG, Birk D, Buchler MW, Dervenis C, Fernandez Cruz L, Friess H, Grahm AL, Jeekel J, Laugier R, Meyer D, Singer MW, Tihanyi T (1999) Development of a disease specific Quality of Life questionnaire module to supplement the EORTC core cancer QoL questionnaire, the QLQ-C30 in patients with pancreatic cancer. Eur J Cancer 35: 939–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fizazi K, Ducreux M, Ruffie P, Bonnay M, Daniel C, Soria JC, Hill C, Fandi A, Poterre M, Smith M, Armand JP (2000) Phase I, dose-finding, and pharmacokinetic study of raltitrexed combined with oxaliplatin in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 18: 2293–2300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glimelius B, Hoffman K, Sjoden PO, Jacobsson G, Sellstrom H, Enander LK, Linne T, Svensson C (1996) Chemotherapy improves survival and quality of life in advanced pancreatic and biliary cancer. Ann Oncol 7: 593–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman K, Glimelius B (1998) Evaluation of clinical benefit of chemotherapy in patients with upper gastrointestinal cancer. Acta Oncol 37: 651–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornmann M, Fakler H, Butzer U, Beger HG, Link KH (2000) Oxaliplatin exerts potent in vitro cytotoxicity in colorectal and pancreatic cancer cell lines and liver metastases. Anticancer Res 20: 3259–3264 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozuch P, Grossbard ML, Barzdins A, Araneo M, Robin A, Frager D, Homel P, Marino J, DeGregorio P, Brucner HW (2001) Irinotecan combined with gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and cisplatin (G-FLIP) is an effective and non crossresistant treatment for chemotherapy refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. Oncologist 6: 488–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionetto R, Pugliese V, Bruzzi P, Rosso R (1995) No standard treatment is available for advanced pancreatic cancer. Eur J Cancer 6: 882–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milella M, Gelibter A, Di Cosimo S, Bria E, Ruggeri EM, Carlini P, Malaguti P, Pellicciotta M, Terzoli E, Cognetti F (2004) Pilot study of celecoxib and infusional 5-fluorouracil as second-line treatment for advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer 101: 133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti P, Marchesi F, Reni M, Mercalli A, Sordi V, Allavena P, Piemonti L (2004) Pancreatic cancer in vitro biology: a comprehensive characterization of pancreatic ductal carcinoma cell line behaviour and chemo-sensitivity for translational research. Virchow's Arch 445: 236–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, Kotecha J, Gallinger S, Au HJ, Nomikos D, Ding K, Ptaszynski M, Parulekar W (2005) Erlotinib improves survival when added to gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. A phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trial Group (NCIC-CTG). Proceedings of the Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium; 27–29 January 2005; Hollywood, FL, USA, p 3: abstract 77

- Moore MJ, Hamm J, Dancey J, Eisenberg PD, Dagenais M, Fields A, Hagan K, Greenberg B, Colwell B, Zee B, Tu D, Ottaway J, Humphrey R, Seymour L (2003) Comparison of gemcitabine vs the matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor BAY 12-9566 in patients with advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 21: 3296–3302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oettle H, Arnold D, Esser M, Huhn D, Riess H (2000) Paclitaxel as weekly second-line therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Anti-Cancer Drugs 11: 635–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J (1998) Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 16: 139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazdur R, Meropol NJ, Casper ES, Fuchs C, Douglass Jr HO, Vincent M, Abbruzzese JL (1996) Phase II trial of ZD1694 (Tomudex) in patients with pancreatic cancer. Invest New Drugs 13: 355–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond E, Chaney SG, Taamma A, Cvitkovic E (1998) Oxaliplatin: a review of preclinical and clinical studies. Ann Oncol 9: 1053–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reni M, Cordio S, Milandri C, Passoni P, Bonetto E, Oliani C, Luppi G, Nicoletti R, Galli L, Bordonaro R, Passardi A, Zerbi A, Balzano G, Aldrighetti L, Staudacher C, Villa E, Di Carlo V (2005) Gemcitabine vs cisplatin, epirubicin, 5-fluorouracil, gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol 6: 369–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reni M, Panucci MG, Passoni P, Bonetto E, Nicoletti R, Ronzoni M, Zerbi A, Staudacher C, Di Carlo V, Villa E (2004) Salvage chemotherapy with mitomycin, docetaxel, and irinotecan (MDI regimen) in metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a phase I and II trial. Cancer Invest 22: 688–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha Lima CMS, Green MR, Rotche R, Miller Jr WH, Jeffrey GM, Cisar LA, Morganti A, Orlando N, Gruia G, Miller LL (2004) Irinotecan plus gemcitabine results in no survival advantage compared with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer despite increased tumor response rate. J Clin Oncol 22: 3776–3783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz JF, Bennouna J, Paillot B, Gamelin E, Francois E, Conroy T, Raoul JL, Becouarn Y, Bertheault-Cvitkovic F, Ychou M, Nasca S, Fandi A, Barthelemy P, Douillard JY (2002) Multicenter non-randomized phase II study of raltitrexed (Tomudex) and oxaliplatin in non-pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol 13: 1072–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehlin JS, Giovanella BC, Natelson EA, DeIpolyi PD, Coil D, Davis B, Wolk D, Wallace P, Trojacek A (1999) A study of 9-nitrocamptothecin (RFS-2000) in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Int J Oncol 14: 821–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich-Pur H, Raderer M, Kornek GV, Schull B, Schmid K, Haider K, Kwasny W, Depisch D, Schneeweiss B, Lang F, Scheitauer W (2003) Irinotecan plus raltitrexed vs raltitrexed alone in patients with gemcitabine-pretreated advanced adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 88: 1180–1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cutsem E, van de Velde H, Karasek P, Oettle H, Vervenne WL, Szawloski A, Schoffski P, Post S, Verslype C, Neumann H, Safran H, Humblet Y, Perez Ruixo J, Ma Y, Von Hoff D (2004) Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus tipifarnib compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 22: 1430–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]