Abstract

Increased levels of postprandial triglycerides (TG) and remnant like particles (RLP) are associated with cardiovascular disease. We evaluated whether postprandial lipemia differed in HIV-positive patients with or without different antiretroviral regimens. A standardized high fat load was administered to 28 subjects: 11 HIV-positive subjects receiving protease inhibitors (PI), 10 HIV-positive subjects receiving non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) and 7 HIV-positive subjects not receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy, HAART (Naïve). Baseline TG levels and TG area under the curve (AUC) did not differ among the three groups. The postprandial TG concentration curves were similar in the NNRTI and Naïve groups, peaking at 3 to 5-hrs. Baseline RLP cholesterol was higher in the NNRTI group compared to other two groups (P=0.035). Both HAART groups (NNRTI and PI) had higher postprandial RLP cholesterol AUC than the Naïve group (P=0.024, ANOVA). In conclusion, during HIV conditions, HAART resulted in a pro-atherogenic pattern with accumulation of remnant lipoproteins.

Keywords: HIV, protease inhibitors-PI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-NNRTI, antiretroviral therapy, postprandial lipemia

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection results in a multitude of metabolic, nutritional and clinical manifestations [1]. Disturbances of lipid metabolism, such as decreased LDL and HDL cholesterol and increased triglyceride levels have been observed in HIV-positive individuals prior to introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) based regimens [1]. Further, abnormalities of lipid metabolism including decreased HDL-cholesterol, increased triglyceride, and a modest increase in LDL-cholesterol levels have been increasingly recognized also among antiretroviral-treated patients [1–5]. HAART generally involves the combination of three drug categories: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) and protease inhibitors (PI). Although there are substantial differences between individual drugs, and also within drug classes, dyslipidemia appears to be more prevalent among patients receiving PI’s [4,5], but use of other antiretroviral regimens, including NRTI's and NNRTIs have also been associated with metabolic changes [6].

Postprandial lipemia is a risk factor for atherosclerosis and postprandial lipoprotein levels are associated with cardiovascular disease [7–10]. However, few studies have focused on postprandial lipemia during HIV/HAART, although several components of the lipid profile associated with HIV/HAART, such as decreased HDL cholesterol and increased triglyceride concentrations, predict the postprandial response [9,11–13]. Compared to healthy HIV-negative control subjects, HIV-positive individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy have delayed clearance of postprandial triglyceride-rich lipoproteins [14]. However, there is a lack of data regarding the postprandial lipid and lipoprotein profile in HIV-positive subjects with or without different types of antiretroviral therapies. As lipid disorders are receiving increasing attention among HIV-positive patients, marked dyslipidemia is becoming more uncommon. However, even in the absence of fasting hyperlipidemia, HIV/HAART might influence lipid features. In the present study, we evaluated whether postprandial lipemia would differ in response to a standardized fat load in a cohort of normolipidemic HIV-infected patients in the absence or presence of different types of antiretroviral therapy.

METHODS

Patients

HIV-positive African American and Hispanic patients were recruited from outpatient HIV clinics at Harlem Hospital Center in New York. Eligibility for enrollment in the study was based on the presence of documented HIV infection, ongoing stable antiretroviral regimen for >6 months, and the absence of hyperlipidemia. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously described [15]. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Columbia University, Harlem Hospital Center, St Luke's-Roosevelt Medical Center, VA Northern California Health Care System, and University of California, Davis, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Overall, 28 patients were recruited for the study; 16 men and 12 women. Twenty-five patients were African American and 3 were Hispanic; 11 patients were undergoing PI-based HAART, 10 patients were undergoing NNRTI-based HAART, and 7 patients did not receive any HAART. For the 21 patients undergoing HAART, the type of antiretroviral regimen was defined as PI-based for patients taking 2 or more nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) in combination with at least 1 PI (lopinavir, indinavir or nelfinavir). NNRTI-based HAART regimens were combinations of ≥2 NRTIs in combination with 1 NNRTI (efavirenz or nevirapine) [16]. Adherence to therapy was gauged by history and follow-up with the primary care provider, and the CD4 count range was 181–1033 (x̄: 515).

Study design

The subjects were admitted to the Columbia University General Clinical Research Center. In the morning, at 0900 a standard high fat meal was administered, consisting of 272.0 g ice cream and frozen deserts (Breyers, Green Bay, Wisconsin), 12.0 g safflower oil (Hollywood), 122.0 g coconut milk (Taste of Thai), 2.0 g vanilla extract without alcohol, 60.0 g evaporated skim milk (Carnation), 6.0 g egg yolk powder (Henningson Foods), 27.0 g of a Polycose powder (Promod, Ross Laboratories) and 37.0 g of a ProMod powder (Promod, Ross Laboratories). The nutrient composition of the meal, based on a body surface area of 2 m2, included 70.4 g fat (51% of total calories) with 40.6 g of saturated fat, 111.3 g carbohydrate (36% of total calories), 47.4 g protein (15% of total calories), 262.0 mg cholesterol, and 1,235 calories. The body surface area of the subjects was calculated using the Dubois equation to gauge the appropriate weight of the meal for each subject. The subjects consumed the meal within a 15-minute period. Blood was drawn at baseline and at 3, 5, 7, and 10 hrs following the fat load.

Laboratory analysis

Immediately after each blood draw, plasma and serum were separated by centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Plasma and serum samples were aliquotted and immediately transferred to a −80°C freezer where they were stored until analyzed. Plasma total, LDL, and HDL-cholesterol, triglyceride, and glucose concentrations were measured by standard enzymatic techniques as previously described [17]. Plasma non-esterified free fatty acids (NEFA) levels were determined by a colorimetric commercial assay (Biochemical Diagnostics, Brentwood, NY) [18]. Plasma insulin concentrations were measured by using commercially available reagents without cross-reactivity with proinsulin concentrations (Linco Research, St Charles, MO) [19]. Homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated using the updated model available from the Oxford Centre for Endocrinology and Diabetes [20]. Lipoprotein remnant-like particle cholesterol (RLP-C) assays were carried out as described previously using commercially available reagents (Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Beltsville, MD) [21]. The intra-assay coefficient of variance was 5–7% and all assays were carried out in duplicate. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by the square of height.

Statistics

Analysis of data was done with SPSS statistical analysis software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Results were expressed as means ± SD. Triglyceride and insulin levels were logarithmically transformed to achieve normal distributions. Baseline comparisons between the 3 groups were performed using one-way ANOVA, and post hoc analyses were performed by Bonferroni test for two independent samples. Group means were compared using Student's t-test. To evaluate response to the fat load, areas under the curve (AUC) were calculated by the trapezoid rule [12]. Between-group AUC differences were evaluated by one-way ANOVA, and post hoc analyses were performed by Tukey test for two independent samples. Multiple linear regression analysis was applied to predict the variables that contributed to the dependent variable – the RLP cholesterol AUC. Unless otherwise noted, a nominal two-sided P value less than 0.05 was used to assess significance.

RESULTS

At baseline, Naïve subjects had lower levels of total, LDL and RLP cholesterol compared with PI and NNRTI-treated patients (Table 1). Baseline triglyceride levels were comparatively higher among PI-treated patients, and insulin levels were higher in both the NNRTI and PI groups compared to the Naïve group, although the differences did not reach statistical significance. There were no significant differences between the three groups in age, BMI, glucose, HOMA-IR, NEFA, HDL cholesterol or CD4 cells at baseline.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of study subjects

| Clinical characteristics | Naïve (n=7) | NNRTI (n=10) | PI (n=11) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men/Women | 4/3 | 7/3 | 5/6 | |

| Age (yrs) | 48.4±9.5 | 43.3±9.5 | 48.3±6.8 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7±5.7 | 25.2±4.4 | 28.0±4.9 | NS |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 91±8 | 92±7 | 91±10 | NS |

| Insulin (µU/ml) | 3.0±1.5 | 6.1±4.4 | 7.6±4.5 | NS |

| HOMA-IR | 2.46±0.92 | 2.66±1.45 | 3.26±1.28 | NS |

| NEFA (mEq/L) | 0.28±0.05 | 0.23±0.04 | 0.29±0.07 | NS |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 111±9 | 153±41 | 155±36 | 0.044 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 62±18 | 93±26 | 98±31 | 0.044 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 32±14 | 42±19 | 37±12 | NS |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 87±15 | 96±42 | 129±94 | NS |

| RLP cholesterol (mg/dl) | 5.2±2.2 | 9.0±2.6* | 7.7±4.0 | 0.035 |

| CD4 cells | 545±280 | 491±164 | 517±222 | NS |

Data are means ± SD.

P<0.05, compared with Naïve group. BMI, body mass index; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment - insulin resistance; NEFA, non-esterified free fatty acids; NS, non-significant (P≥0.05). P-values were calculated using one-way ANOVA analyses, and post hoc analyses were performed by Tukey test for two independent samples. Values for insulin, HOMA-IR, triglyceride and RLP cholesterol levels were logarithmically transformed before analyses. The non-transformed values are shown in the table.

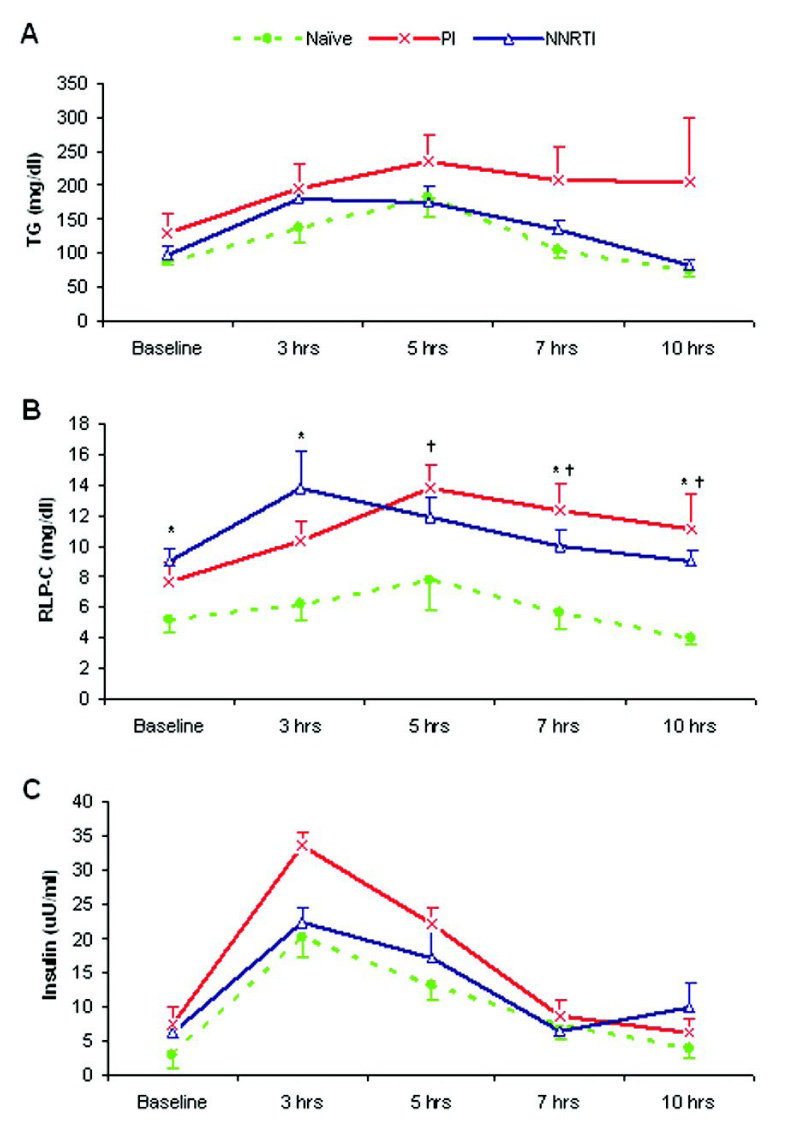

We next compared the postprandial response curves in the three groups for lipids, lipoproteins, RLP cholesterol, insulin and NEFA. The postprandial curve patterns for total, LDL and HDL cholesterol and NEFA were very similar between groups and there were no significant differences between the three groups. As seen in Figure 1A, the postprandial triglyceride concentration curves were similar in the NNRTI and Naïve groups, peaking at 3 to 5 hours. Although not reaching significance, the PI group had higher triglyceride levels at peak and at later time periods, suggesting a trend for a relative accumulation of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Both HAART groups (NNRTI and PI) had significantly higher baseline and postprandial RLP cholesterol levels compared to the Naïve group (P<0.05) throughout the 10-hr period (Figure 1B). Similar to triglyceride levels, RLP cholesterol levels peaked at 3–5 hours. All three groups showed a similar pattern in the postprandial insulin pattern with a rapid rise peaking at 3-hr and thereafter a slow decline (Figure 1C). No significant differences were observed between the treatment conditions.

Figure 1.

Postprandial response curves for Triglyceride (A), RLP cholesterol (B) and insulin (C). Data are means ± SE. *: P<0.05, PI vs. Naïve group; †: P<0.05, NNRTI vs. Naïve group. P-values were calculated using one-way ANOVA analyses, and values for triglyceride, RLP cholesterol and insulin levels were logarithmically transformed before analyses. The non-transformed values were shown in the figure.

We next calculated the AUC and the incremental AUC for lipids, lipoproteins, RLP cholesterol, insulin and NEFA. The postprandial AUC for triglyceride was higher in the PI than in the NNRTI and Naive groups (1782 vs. 1255 and 1082 mg/dl×hr, respectively), although the differences were not statistically significant (Table 2). The postprandial AUC for RLP cholesterol was significantly higher in the PI and NNRTI groups (101 and 97 mg/dl×hr, respectively) compared to the Naïve group (51 mg/dl×hr). The AUC for insulin was higher in the PI group that in Naïves, and the difference between two groups was borderline significant (158 vs. 101 mg/dl×hr, P=0.054). For incremental AUC, although the values for triglycerides and RLP cholesterol were higher for the PI and NNRTI groups compared with the Naïve group, no significant differences were seen between three groups using one-way ANOVA analysis. Although number of subjects was limited, power calculations for one-way ANOVA show that a study design with an average of 9 per group (we have 7 to 11 subjects per group) would have better than 80% power to detect a difference between largest and smallest group of 1.6 – 1.75 SD at level α=0.05. When treatment groups were directly compared using t-test, the incremental AUC for RLP cholesterol was significantly higher in the PI compared to the Naïve group (35 vs. 7 mg/dl×hr, P=0.045). There were no differences in postprandial AUC and incremental AUC for insulin, glucose, NEFA, total, LDL or HDL cholesterol levels between the three groups.

TABLE 2.

Postprandial AUC and incremental AUC for triglyceride, RLP cholesterol and insulin

| AUC | Naïve (n=7) | NNRTI (n=10) | PI (n=11) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total AUC | ||||

| Triglyceride (mg/dl×hr) | 1082±390 | 1255±391 | 1782±1420 | NS |

| RLP cholesterol (mg/dl×hr) | 51±18 | 97±32* | 101±41* | 0.002 |

| Insulin (µU/ml×hr) | 101±52 | 121±88 | 158±81 | NS |

| Incremental AUC | ||||

| Triglyceride (mg/dl×hr) | 344±293 | 459±339 | 684±658 | NS |

| RLP cholesterol (mg/dl×hr) | 7±17 | 20±28 | 35±32 | NS |

| Insulin (µU/ml×hr) | 75±46 | 69±81 | 94±69 | NS |

Data are means ± SD.

P<0.05, compared with Naïve group. NS, non-significant (P ≥0.05). P-values were calculated using One-way ANOVA analyses, and post hoc analyses were performed by Tukey test for two independent samples. Values for triglyceride, RLP cholesterol and insulin levels were logarithmically transformed before analyses. The non-transformed values are shown in the table.

Finally, as the RLP cholesterol AUC was significantly higher in both the PI and NNRTI groups, we performed multiple linear regression analysis to explore potential predictors. When analyzing all subjects together, baseline triglyceride levels predicted the RLP cholesterol AUC (P<0.001). In subsequent exploratory analysis, baseline levels of HDL cholesterol (P=0.027), NEFA (P=0.004), triglyceride (P<0.001) and RLP cholesterol (P=0.002) were significantly and independently associated with the RLP cholesterol AUC in the PI group. In contrast, in the NNRTI group, only baseline levels of RLP cholesterol (P=0.009) were associated with RLP cholesterol AUC.

DISCUSSION

Our study design allowed us to address the effect of HAART vs. no HAART as well as the effect of different types of HAART regimens on the postprandial response in HIV-positive subjects. Our results demonstrate that for this HIV population with no sign of hyperlipidemia at baseline, irrespective of antiretroviral regimen, HAART treatment resulted in a higher postprandial RLP cholesterol AUC. In contrast, no difference in postprandial triglyceride AUC was found between the groups. Thus, our results demonstrate a consistent increase in remnant levels throughout the postprandial state in normolipidemic subjects undergoing HAART.

To assess the effect of antiretroviral therapy on lipid metabolism in HIV-positive subjects meeting lipid treatment guidelines, we recruited patients without sign of fasting dyslipidemia [22]. In contrast to previous studies comparing healthy, HIV-negative subjects to HIV-positive patients, we specifically tested whether differences in antiretroviral therapy across groups with comparable normal baseline lipids would impact on the postprandial response [14]. Due to this design, it is not surprising that postprandial triglyceride levels were similar among three groups. However, in the present study we observed that irrespective of regimen, compared to subjects naïve to antiretroviral treatment HAART resulted in postprandial accumulation of RLP cholesterol. The fact that these results were seen in the absence of any difference in triglyceride levels indicates a selective impact of HAART on remnant levels among HIV-positive patients. Our results imply that HAART might uncover an increased susceptibility among HIV-positive subjects for accumulation of lipoprotein remnant particles under both postprandial and fasting conditions. As we recruited normolipidemic subjects in our study, it is possible that a more pronounced increase in postprandial remnant particles could occur in HIV-positive subjects on HAART with presence of fasting dyslipidemia. Notably, an increase in remnant levels has been documented for dyslipidemic, HIV negative subjects [23].

Increased triglyceride levels are part of the most common lipoprotein pattern reported to date in HIV/HAART [2,4,5,24]. Further, treatment with PI’s, in particular ritonavir, has resulted in pronounced hypertriglyceridemia [2,5]. The observation of a trend for higher triglyceride levels during later time periods in the PI group is compatible with a relative accumulation of triglyceride rich lipoproteins during PI treatment. Further, the incremental AUC for RLP cholesterol was significantly higher in the PI compared to the Naïve group. Together, these results suggest that among PI-treated subjects, the fat load might result in an increased accumulation of remnants. In support of this, PI use has been associated with an increased postprandial triglyceride response with a slower clearance in previous studies comparing HIV-positive and HIV-negative subjects [14]. Further, among subjects undergoing HAART, PI use is associated with an increased frequency of myocardial infarction[25]. Baseline RLP cholesterol was an independent predictor of RLP AUC, regardless of the HAART regimen. This finding implicates that additional measurement of RLP cholesterol might give further information in clinical practice for patients receiving HAART regimen. Our results suggest an increased exposure of the vessel wall to atherogenic lipoprotein remnants in patients receiving HAART. Further studies are needed to explore these results.

We recognize that the present study has some limitations. The number of participants was limited, and subjects with hyperlipidemia were excluded. Therefore, between-group differences in lipid levels in our study were not as prominent as in other studies of HAART and lipoproteins. Although we included both men and women, we did not have the power to analyze potential gender differences, and further studies are needed to explore this issue. Further we measured only one remnant characteristic. We recognize that our results need to be interpreted with these limitations in mind. Strengths of our study included the enrollment of well-controlled patients without sign of fasting dyslipidemia, inclusion of a relatively understudied minority population, and the focus on HIV-positive patients representing antiretroviral naïve conditions as well as different HAART regimens.

In conclusion, irrespective of regimen, HAART resulted in a higher postprandial RLP cholesterol AUC, while no difference in postprandial triglyceride AUC was found across antiretroviral therapy. Our results demonstrate a consistent increase in remnant levels throughout the postprandial state in HAART. Thus, during HIV conditions, antiretroviral treatment resulted in a pro-atherogenic pattern, with a relative increase in remnant lipoproteins.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The project was supported by grant HL 65938 (Berglund, L, PI) from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, and by California Research Center for the Biology of HIV in Minorities, California HIV/AIDS Research Program CH05-D-606. This work was supported in part by the UC Davis Clinical and Translational Science Center (RR 024146). Dr. E. Anuurad is a recipient of an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (0725125Y). We thank Prof. Laurel Beckett, Division of Biostatistics, Department of Public Health Sciences, UC Davis for assistance in the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carr A, Samaras K, Burton S, et al. A syndrome of peripheral lipodystrophy, hyperlipidaemia and insulin resistance in patients receiving HIV protease inhibitors. AIDS. 1998;12:F51–F58. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199807000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr A, Samaras K, Thorisdottir A, et al. Diagnosis, prediction, and natural course of HIV-1 protease-inhibitor-associated lipodystrophy, hyperlipidaemia, and diabetes mellitus: a cohort study. Lancet. 1999;353:2093–2099. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danner SA, Carr A, Leonard JM, et al. A short-term study of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of ritonavir, an inhibitor of HIV-1 protease. European-Australian Collaborative Ritonavir Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1528–1533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512073332303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulligan K, Grunfeld C, Tai VW, et al. Hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance are induced by protease inhibitors independent of changes in body composition in patients with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;23:35–43. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200001010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saves M, Raffi F, Capeau J, et al. Factors related to lipodystrophy and metabolic alterations in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1396–1405. doi: 10.1086/339866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saint-Marc T, Partisani M, Poizot-Martin I, et al. Fat distribution evaluated by computed tomography and metabolic abnormalities in patients undergoing antiretroviral therapy: preliminary results of the LIPOCO study. AIDS. 2000;14:37–49. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200001070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bansal S, Buring JE, Rifai N, et al. Fasting compared with nonfasting triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular events in women. JAMA. 2007;298:309–316. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyson D, Rutledge JC, Berglund L. Postprandial lipemia and cardiovascular disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2003;5:437–444. doi: 10.1007/s11883-003-0033-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nordestgaard BG, Benn M, Schnohr P, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and death in men and women. JAMA. 2007;298:299–308. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karpe F. Postprandial lipoprotein metabolism and atherosclerosis. J Intern Med. 1999;246:341–355. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Couch SC, Isasi CR, Karmally W, et al. Predictors of postprandial triacylglycerol response in children: the Columbia University Biomarkers Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:1119–1127. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.5.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis GF, O'Meara NM, Soltys PA, et al. Fasting hypertriglyceridemia in noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus is an important predictor of postprandial lipid and lipoprotein abnormalities. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;72:934–944. doi: 10.1210/jcem-72-4-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stein JH, Merwood MA, Bellehumeur JB, et al. Postprandial lipoprotein changes in patients taking antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:399–405. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000152233.80082.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas-Geevarghese A, Raghavan S, Minolfo R, et al. Postprandial response to a physiologic caloric load in HIV-positive patients receiving protease inhibitor-based or nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:146–154. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riddler SA, Smit E, Cole SR, et al. Impact of HIV infection and HAART on serum lipids in men. JAMA. 2003;289:2978–2982. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.22.2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuck CH, Holleran S, Berglund L. Hormonal regulation of lipoprotein(a) levels: effects of estrogen replacement therapy on lipoprotein(a) and acute phase reactants in postmenopausal women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:1822–1829. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.9.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albu JB, Curi M, Shur M, et al. Systemic resistance to the antilipolytic effect of insulin in black and white women with visceral obesity. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E551–E560. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.3.E551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ginsberg HN, Kris-Etherton P, Dennis B, et al. Effects of reducing dietary saturated fatty acids on plasma lipids and lipoproteins in healthy subjects: the DELTA Study, protocol 1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:441–449. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adler AI, Levy JC, Matthews DR, et al. Insulin sensitivity at diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes is not associated with subsequent cardiovascular disease (UKPDS 67) Diabet Med. 2005;22:306–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devaraj S, Vega G, Lange R, Grundy SM, Jialal I. Remnant-like particle cholesterol levels in patients with dysbetalipoproteinemia or coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 1998;104:445–450. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dube MP, Stein JH, Aberg JA, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of dyslipidemia in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy: recommendations of the HIV Medical Association of the Infectious Disease Society of America and the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:613–627. doi: 10.1086/378131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ooi TC, Cousins M, Ooi DS, et al. Postprandial remnant-like lipoproteins in hypertriglyceridemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3134–3142. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.7.7627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friis-Moller N, Sabin CA, Weber R, et al. Combination antiretroviral therapy and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1993–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friis-Moller N, Reiss P, Sabin CA, et al. Class of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1723–1735. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]