Abstract

In order to examine the role of left perisylvian cortex in spelling, 13 individuals with lesions in this area were administered a comprehensive spelling battery. Their spelling of regular words, irregular words, and nonwords was compared with that of individuals with extrasylvian damage involving left inferior temporo–occipital cortex and normal controls. Perisylvian patients demonstrated a lexicality effect, with nonwords spelled worse than real words. This pattern contrasts with the deficit in irregular word spelling, or regularity effect, observed in extrasylvian patients. These findings confirm that damage to left perisylvian cortex results in impaired phonological processing required for sublexical spelling. Further, degraded phonological input to orthographic selection typically results in additional deficits in real word spelling.

Keywords: Phonological agraphia, Aphasia, Perisylvian cortex, Lexical agraphia, Spelling, Writing, Phonological processing

1. Introduction

The relationship between phonology (sounds) and orthography (letters) in English has been described as “quasi-regular” (Plaut, McClelland, Seidenberg, & Patterson, 1996). Some phoneme-to-grapheme mappings are regular or predictable (as in the word stop), in that the spelling could be derived using a sounding out procedure, or through conversion of each sound to its corresponding letter. Other lexical items, such as tomb, have irregular or exceptional phoneme–grapheme relationships for which a sound-to-letter conversion strategy would generate an incorrect response. Cognitive models of language processing have attempted to explain how spellings for both regular and irregular words, as well as novel stimuli such as pronounceable nonwords (e.g., flig), are generated. Traditional dual-route spelling models posit two distinct procedures by which spellings for words can be achieved (Ellis, 1982). A memory-based, lexical–semantic route is said to generate spellings for real (familiar) words, and a rule-based, sublexical route is proposed for spelling unfamiliar words and nonwords through sound-to-letter conversion.

Neuropsychological studies have demonstrated that focal brain lesions can produce selective impairment of the two hypothesized spelling routes. Damage to the lexical–semantic spelling route gives rise to the syndrome of lexical agraphia, characterized by disproportionate difficulty in spelling irregular words (Baxter & Warrington, 1987; Beauvois & Derouesné, 1981; Behrmann, 1987; Goodman & Caramazza, 1986a; Goodman & Caramazza, 1986b; Hatfield & Patterson, 1983; Roeltgen & Heilman, 1984). Correct spelling of irregular words depends critically on the retrieval of word-specific orthographic information. Presumably, damage or impaired access to orthographic representations in lexical agraphia forces patients to rely on the sublexical spelling route. Although regular words and nonwords can be correctly spelled by phoneme–grapheme conversion, the sublexical strategy results in phonologically plausible errors when spelling irregular words (yacht → yot). Lexical agraphia is typically associated with extrasylvian lesions involving the left temporo–parieto–occipital junction (Beauvois & Derouesné, 1981; Behrmann, 1987; Croisile, Trillet, Laurent, Latombe, & Schott, 1989; Goodman & Caramazza, 1986a; Hatfield & Patterson, 1983; Rapp & Caramazza, 1997; Roeltgen & Heilman, 1984; Vanier & Caplan, 1985). In particular, damage to the angular gyrus and/or posterior middle/inferior temporal gyrus has been implicated in a number of cases. More recently, Rapcsak and Beeson (2004) described lexical agraphia in a group of patients with left inferior temporo–occipital lesions. This study employed a comprehensive spelling battery designed to determine the effects of orthographic regularity, frequency, and lexicality (word versus nonword status) on spelling accuracy. All eight patients in this study presented with behavioral profiles consistent with lexical agraphia, and each had damage to extrasylvian cortical regions including Brodmann areas 37 and 20, with notable sparing of the angular gyrus (BA 39). The results of this study provided converging evidence with fMRI studies of normal individuals reporting activation in BA 37/20 during written spelling of familiar words (Beeson et al., 2003; Nakamura et al., 2000).

Impairment of the sublexical spelling route is referred to as phonological agraphia. Individuals with phonological agraphia have difficulty generating spellings for unfamiliar words or pronounceable nonwords. Shallice first described the disorder in 1981, and a number of studies have since attempted to refine the behavioral profile and isolate the relevant neural substrates (Alexander, Friedman, Loverso, & Fischer, 1992; Baxter & Warrington, 1995; Bolla-Wilson, Speedie, & Robinson, 1985; Bub & Kertesz, 1982; Goodman-Schulman & Caramazza, 1987; Kim & Na, 2000; Kim, Chu, Lee, Kim, & Park, 2002; Langmore & Canter, 1983; Marien, Pickut, Engelborghs, Martin, & DeDeyn, 2001; Roeltgen, Sevush, & Heilman, 1983). While the inability to spell nonwords is the defining deficit in phonological agraphia, real word spelling is almost always impaired to some degree. In fact, “pure” cases seem to be quite rare and the more frequent clinical profile is one of disproportionate impairment of nonword spelling relative to real word spelling. In particular, real word spelling performance may be affected by lexical–semantic variables, such as word frequency (high > low), imageability (high > low), and grammatical class (content words > functors) (for reviews, see Alexander et al., 1992; Rapcsak & Beeson, 2002). Real word spelling errors are generally phonologically implausible attempts, often bearing some visual or orthographic similarity to the target word (e.g., summer → sumree). This type of error is thought to reflect reliance on an orthographic lexicon that is functionally inadequate when deprived of input from phonology (Rapcsak & Beeson, 2002).

With respect to neural substrates, Roeltgen and colleagues (Roeltgen, 1993; Roeltgen & Heilman, 1985; Roeltgen et al., 1983) asserted that the critical lesion site in phonological agraphia involved the anterior supramarginal gyrus (BA 40) and/or the insula deep to it. Additional cortical regions consistently implicated in the disorder include Broca’s area (BA 44/45) and the superior temporal gyrus (BA 22) (Alexander et al., 1992; Kim & Na, 2000; Kim et al., 2002; Marien et al., 2001; Rapcsak & Beeson, 2002). While many researchers have attempted to link phonological spelling abilities to a single perisylvian sub-region, an alternative view contends that phonological agraphia may result from damage to a number of perisylvian cortical areas that together comprise a distributed neural network dedicated to phonological processing (Alexander et al., 1992; Kim et al., 2002; Rapcsak & Beeson, 2002). The distributed nature of the neural systems involved in phonological processing is supported by functional imaging studies of speech production/perception and phonological awareness (e.g., Buchsbaum, Hickok, & Humphries, 2001; Demonet, Chollet, & Ramsay, 1992; St. Heim, Opitz, Müller, & Friederici, 2003). There is also fMRI evidence supporting the involvement of multiple perisylvian cortical regions in phoneme–grapheme conversion in normal individuals. For instance, Beeson and Rapcsak (2003) demonstrated activation in Broca’s area (BA 44/45), precentral gyrus (BA 6/4), the insula, and superior/middle temporal gyrus (BA 22/21) when nonword spelling was contrasted either with real word spelling or with drawing shapes. Another fMRI study, conducted by Omura, Tsukamoto, Kotani, Ohgami, and Yoshikawa (2004), also detected activation in left pre-motor cortex/Broca’s area as well as the left superior temporal gyrus during a phoneme–grapheme conversion task. It has been proposed that spelling by the sublexical route entails a number of distinct mental computations and processes, including phoneme discrimination, phonological segmentation, phoneme–grapheme conversion, phonological short-term memory, and subvocal rehearsal (Ellis, 1982; Kim et al., 2002; Rapcsak & Beeson, 2002; Roeltgen et al., 1983; Shallice, 1981). The relative contribution of distinct regions within left perisylvian cortex to these operations awaits clarification.

To date, most studies of phonological agraphia have relied on description of single cases, with writing profile as the inclusion criterion. As a result, it is currently unknown how reliable and reproducible is the association between perisylvian damage and phonological agraphia. Furthermore, as pointed out by Alexander et al. (1992), behavioral test batteries were highly variable across studies and detailed neuroanatomical information was inconsistently provided, thereby limiting the ability to correlate spelling performance with specific lesion site. In addition, to confirm the proposed functional role of perisylvian regions in the spelling process, it needs to be shown that lesions that do not involve these cortical areas give rise to a different spelling profile. The investigations reported here were designed to overcome some of the limitations of previous studies by selecting patients based on neuroanatomical rather than behavioral criteria and by comparing perisylvian patients to a group of patients with extrasylvian lesions involving left inferior temporo–occipital cortex (hereafter referred to as “extrasylvian,” for convenience) who were administered the same comprehensive spelling battery.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Thirteen patients with left perisylvian lesions were recruited for this study (Table 1). The majority of the participants were current or former patients of the University of Arizona Aphasia Clinic; others were recruited from the Tucson community. Eleven participants had damage resulting from ischemic stroke within the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory, one had a cerebral hemorrhage due to left MCA aneurysm, and one had an intracranial hemorrhage following a left hemisphere arteriovenous malformation rupture. Ten participants were right-handed prior to stroke and three were left-handed. Of the 10 right-handed individuals, four shifted to use of the left hand as a result of hemiparesis following stroke. Mean age for the group was 57.2 years (range 40–72) and average time post onset was 55.3 months (range 8–130). Participants had an average of 14.4 years of education (range 11–18). The performance of the perisylvian group was compared to that of the eight individuals with extrasylvian lesions reported in Rapcsak and Beeson (2004, Table 2). Lesion etiology in 7/8 participants in the extrasylvian group was ischemic stroke in the distribution of the left posterior cerebral artery (PCA), whereas the remaining individual developed a left temporal lobe hematoma as a complication of anticoagulant therapy. The control group included the eleven individuals from the previous study, plus five additional individuals with no history of neurological illness. Although the patients with perisylvian damage tended to be younger than those with extrasylvian lesions, there were no significant differences among the three groups with respect to age (F(2, 34) = 3.09, p = .058) or education (F(2, 34) = 1.877, p = .169).

Table 1.

Demographic information and test scores for patients with perisylvian damage

| Participants | HD | GM | MK | AB | RG | JR | GB | ED | JS | ML | LL | AS | EH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | M | M | M | M | F | M | M | M | F | M | M | F | M |

| Age | 66 | 60 | 55 | 65 | 40 | 64 | 58 | 45 | 48 | 47 | 59 | 64 | 72 |

| Hand pre/post | R/R | L/L | R/L | R/L | R/R | R/L | R/L | L/L | R/R | R/R | R/R | L/L | R/R |

| Education (years) | 16 | 18 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 18 | 14 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 17 | 14 | 12 |

| TPO | 25 | 95 | 11 | 11 | 48 | 52 | 19 | 130 | 8 | 53 | 112 | 47 | 108 |

| BNT | 56 | 55 | 41 | 0 | 50 | 54 | 46 | 27 | 13 | 34 | 45 | 40 | 55 |

| PPT | 51 | 49 | 42 | 49 | 50 | 52 | 46 | 51 | 46 | 50 | 44 | 50 | 51 |

| WAB AQ | 97.8 | 94.3 | 47.1 | 19.8 | 94.0 | 82.5 | 79.6 | 72.1 | 42.9 | 84.1 | 89.8 | 85.0 | 91.8 |

| Aphasia type | Non | Non | C | B | Non | A | A | A | B | C | A | C | A |

TPO, time post onset (months); BNT, Boston Naming Test (max. score = 60); PPT, Pyramids and Palm Trees Test (max. score = 52); WAB AQ, Western Aphasia Battery Aphasia Quotient (max. = 100); Aphasia type (from Western Aphasia Battery); Non, non-aphasic; C, conduction; B, Broca’s; A, anomic.

Table 2.

Demographic information and test scores (mean and SD) for patient and control groups

| Perisylvian | Extrasylviana | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 10M:3F | 8M | 12F:4M |

| Age | 57.2 (9.6) | 69.0 (11.9) | 63.4 (11.1) |

| Education | 14.4 (2.3) | 13.4 (2.5) | 15.3 (2.1) |

| Time post onset (months) | 55.3 (42.5) | 13.0 (13.4) | |

| Western Aphasia Battery | 75.4 (23.9) | 93.4 (4.99) | |

| Boston Naming Test | 39.7 (17.3) | 34.5 (15.0) | |

| Pyramids and Palm Trees Test | 48.5 (3.1) | 47.6 (3.2) |

2.2. Language profile

Participants in the group with perisylvian lesions presented with a range of aphasia types and severities, as measured by the Western Aphasia Battery (Kertesz, 1982) (Table 1). The mean Aphasia Quotient (AQ) for the perisylvian group was 75.4 (SD = 23.9). The aphasia profiles included Broca’s (2), conduction (3), and anomic aphasia (5); three individuals tested as non-aphasic. Table 2 shows that the overall language impairment of the perisylvian patients was greater than that of the extrasylvian group [mean AQ = 93.4, SD = 4.99; t(13.6) = −2.61, p = .021]. The extrasylvian group included four individuals with anomic aphasia and four who tested as non-aphasic. Group means for the Boston Naming Test (BNT; Kaplan, Goodglass, & Weintraub, 2001) and the Pyramids and Palm Trees Test, a test of semantic association (Howard & Patterson, 1992), are presented in Table 2. Most participants in the perisylvian group (9 of 13) demonstrated evidence of significant anomia on the BNT, as did seven of eight in the group with extrasylvian lesions. Four of the 13 individuals with perisylvian lesions and two of the eight with extrasylvian lesions demonstrated a clinically significant semantic impairment.

2.3. Spelling assessment

Stimuli for writing to dictation tasks were designed to detect the influence of various linguistic variables known to affect spelling accuracy in individuals with agraphia, including orthographic regularity, word frequency, and lexical status (i.e., word versus nonword) (Beeson & Hillis, 2001; Ellis, 1982; Roeltgen & Heilman, 1985). The spelling battery consisted of 60 regular words demonstrating predictable sound to letter correspondences (e.g., pine) and 60 irregular or exception words (e.g., laugh), which could not be spelled accurately by reliance on phoneme-to-grapheme conversion. Regular and irregular words were evenly distributed across three frequency bands (low = 0–20 occurrences per million, medium = 21–100, high = >100; Kucera & Francis, 1967). Imageability ratings for 48 of 60 irregular words and 45 of 60 regular words were available (Paivio, Yuille, & Madigan, 1968). A comparison of imageability values for regular and irregular subsets revealed no significant difference (t(91) = −.497, p = .621). Word length varied from four to eight letters and was balanced across lists. Twenty pronounceable nonwords (e.g., merber) were included to assess sublexical spelling ability (sound-to-letter conversion). Nonwords were derived by changing 1–2 letters in real words while maintaining phonological plausibility. Nonwords were comparable to real word stimuli in terms of length. Word and nonword stimuli were presented verbally by the examiner and repeated by the participant prior to spelling in order to ensure correct stimulus perception. Analysis of spelling errors was conducted using a modified version of the Johns Hopkins Dyslexia and Dysgraphia Batteries (Goodman & Caramazza, 1986b) error classification system.

2.4. Lesion analysis

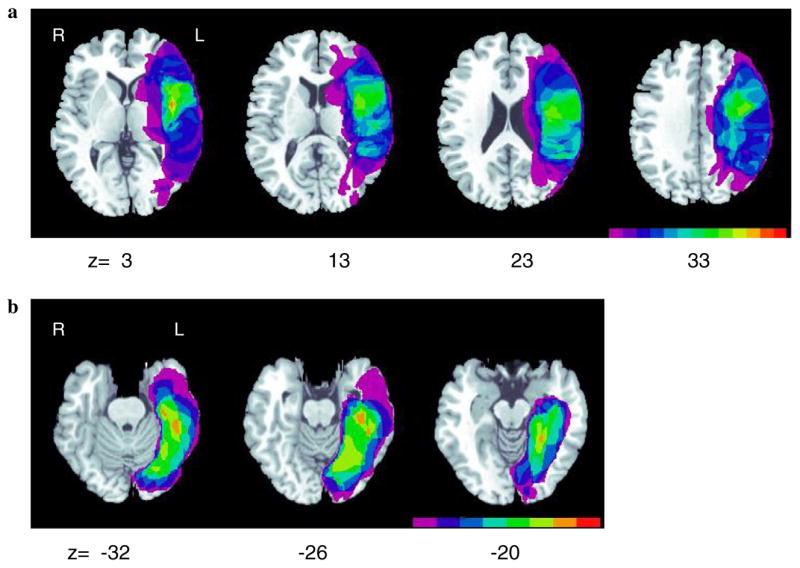

Clinical CT or MRI scans were collected for all participants. Axial slices were matched to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) T1 template within the MRIcro software program (Rorden & Brett, 2000) and lesion boundaries were manually traced onto separate templates for each participant. The lesions, drawn as regions of interest (ROIs) for each patient, were then displayed on a common template in order to determine areas of lesion overlap (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

(a) Lesion overlap maps for perisylvian patients (n = 13). Color bar indicates the number of subjects with damage to a given neuroanatomical area (fuchsia = 1; red = 13). (b) Lesion overlap maps for extrasylvian patients (n = 8; Rapcsak and Beeson, 2004). Color bar indicates the number of subjects with damage to a given neuroanatomical area (fuchsia = 1; red = 8).

3. Results

3.1. Effect of stimulus type

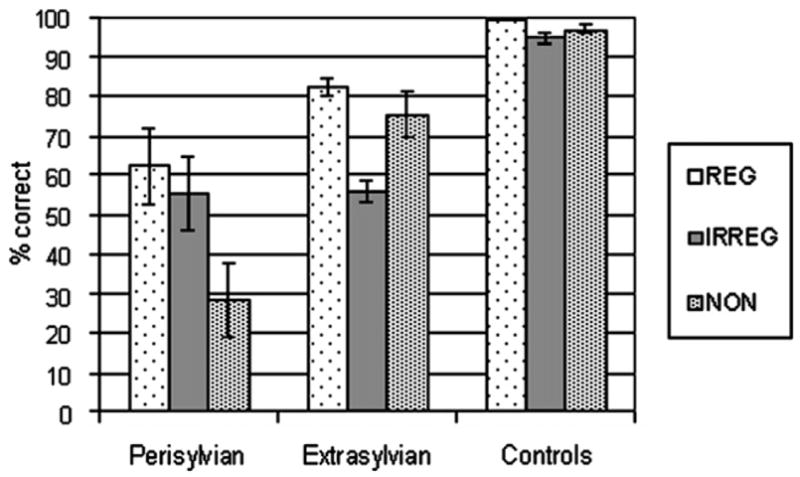

Spelling accuracy for each stimulus type (regular, irregular, and nonwords) is shown for the three groups in Fig. 2. A 3 (group) × 3 (stimulus type) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed main effects of group and stimulus type and a group by stimulus type interaction (Table 3). To further explore this interaction, follow-up contrasts were conducted using a pooled error term and degrees of freedom reflecting variance from within and between group analyses. Significance levels were adjusted by the Bonferroni procedure (α = .0056). This analysis indicated that the perisylvian group performed worse than the control group on all stimulus types, and worse than the extrasylvian group on nonwords only. The extrasylvian group performed worse than the control group on irregular words alone. To examine the effect of stimulus type on performance within each group, additional pairwise comparisons were conducted (α = .0056). In the perisylvian group, nonwords were spelled worse than both regular and irregular words, and in the extrasylvian group, irregular words were spelled worse than both regular words and nonwords. No pairwise comparisons were significant for the control group. Taken together, these results indicate a disproportionate impairment of nonword spelling in patients with perisylvian lesions, consistent with phonological agraphia. By contrast, patients with extrasylvian lesions showed a predominant impairment in spelling irregular words, consistent with lexical agraphia.

Fig. 2.

Spelling performance for each group on regular words, irregular words, and nonwords.

Table 3.

ANOVA examining the effects of group (perisylvian, extrasylvian, controls) and stimulus type (regular words, irregular words, nonwords) on spelling performance

| Source | df | MS | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect of group | 2 | 25,312.31 | 24.12 | .001 |

| Error | 34 | 1049.54 | ||

| Main effect of stimulus type | 2 | 2115.68 | 23.24 | .001 |

| Interaction: group × stimulus type | 4 | 1833.45 | 20.14 | .001 |

| Error | 68 | 91.03 |

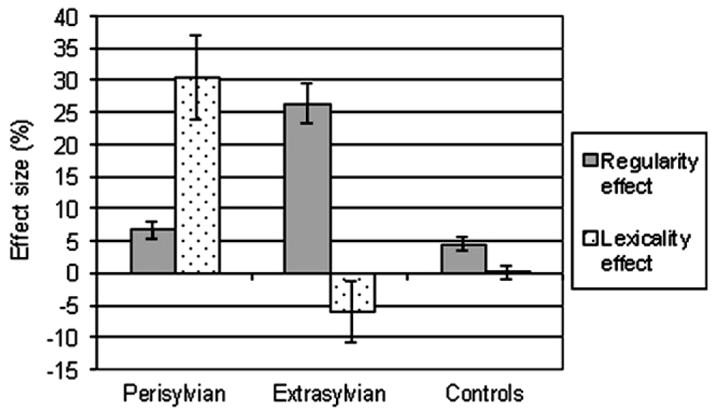

3.2. Regularity and lexicality effects

The disproportionate deficits in nonword spelling in the perisylvian patients and irregular word spelling in the extrasylvian patients were further confirmed by calculation of lexicality and regularity effects (Fig. 3). The lexicality effect was calculated as percent correct real words minus percent correct nonwords. The magnitude of the lexicality effect was compared across the three groups using a one-way ANOVA, which revealed a significant difference between the groups (F(2, 34) = 18.207, p < .001). Pairwise comparisons indicated that the lexicality effect was significantly larger in the perisylvian patients relative to both extrasylvian patients and controls, with no significant difference detected between the latter two groups. The regularity effect was calculated as percent correct regular words minus percent correct irregular words. The size of the regularity effect was compared using a one-way ANOVA, which showed a significant difference between groups (F(2,34) = 44.076, p < .001). Pairwise comparisons indicated that the regularity effect was significantly larger in the extrasylvian group relative to both perisylvian patients and controls, with no significant difference demonstrated between the latter two groups.

Fig. 3.

Regularity and lexicality effects for spelling in each group.

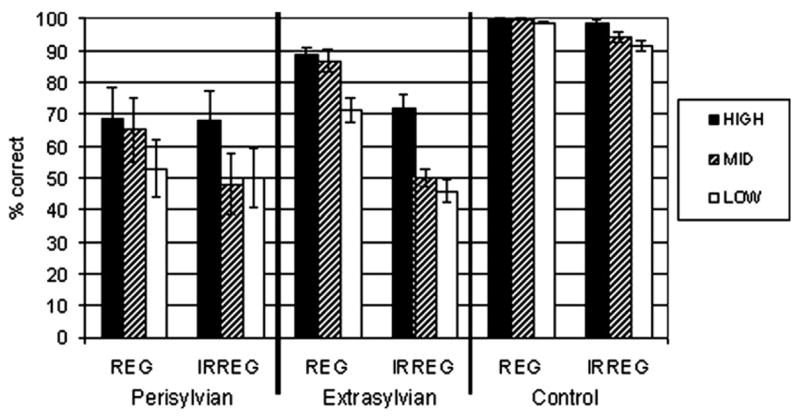

3.3. Orthographic regularity and word frequency

Real word spelling performance as a function of frequency and regularity is depicted in Fig. 4. A 2 (regularity) × 3 (frequency) ANOVA was conducted for each patient group and for the control group. In each group, main effects of frequency and regularity were observed, as well as a frequency × regularity interaction (see Tables 4–6). Pairwise comparisons were conducted in each group to further explore the interaction (adjusted α value = .0056). Comparison across frequency bands within regular and irregular words revealed that regular high and medium frequency words were spelled more accurately than regular low frequency words in the perisylvian and extrasylvian groups. In the control group, no effect of word frequency was observed for regularly spelled items. In both patient groups as well as the control group, irregular high frequency words were spelled more accurately than both irregular medium and low frequency items. Comparisons of regularly versus irregularly spelled words within each frequency band indicated a significant regularity effect (regular > irregular) only for medium frequency words in the perisylvian group. In contrast, the extrasylvian group demonstrated a regularity effect across all three frequency bands. In the control group, the regularity effect was observed for both medium and low frequency words. To summarize, perisylvian and extrasylvian patients showed similar sensitivity to word frequency, but the effect of orthographic regularity was more pronounced in the extrasylvian group.

Fig. 4.

Spelling performance in each group for regular versus irregular words across word frequency bands.

Table 4.

ANOVA for spelling by the perisylvian group examining spelling regularity (regular versus irregular) and word frequency (high, medium, low)

| Source | df | MS | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect of regularity | 1 | 900.32 | 24.71 | .001 |

| Error | 12 | 36.43 | ||

| Main effect of frequency | 2 | 1917.63 | 31.60 | .001 |

| Error | 24 | 60.68 | ||

| Interaction: regularity × frequency | 2 | 511.86 | 6.82 | .005 |

| Error | 24 | 75.05 |

Table 6.

ANOVA for spelling by the control group examining spelling regularity (regular versus irregular) and word frequency (high, medium, low)

| Source | df | MS | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect of regularity | 1 | 504.17 | 22.41 | .001 |

| Error | 15 | 22.50 | ||

| Main effect of frequency | 2 | 133.07 | 7.98 | .002 |

| Error | 30 | 16.68 | ||

| Interaction: regularity × frequency | 2 | 84.64 | 6.13 | .006 |

| Error | 30 | 13.80 |

3.4. Analysis of spelling errors

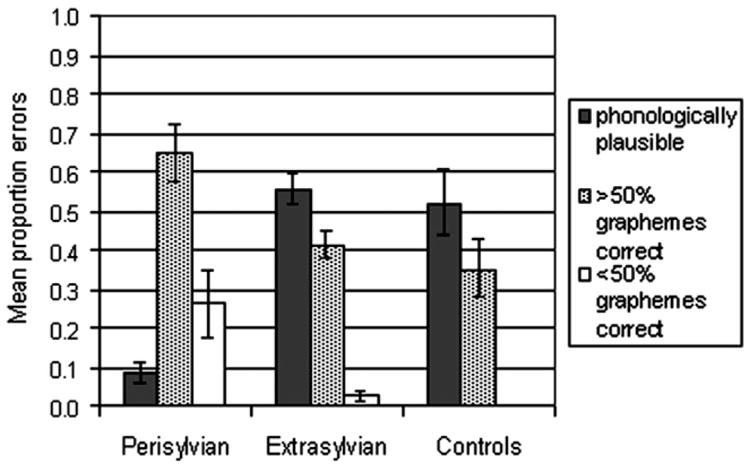

Errors produced by patients lend insight into the cognitive strategies employed during spelling attempts. Mean proportions of spelling error types in each group are shown in Fig. 5. In the perisylvian group, only 8.5% of total errors on real words were phonologically plausible; 65% of total errors resembled the target, with at least half of graphemes produced correctly (these errors included visually similar words, morphological errors, and phonologically implausible nonwords). In the remainder of error responses (26.5%), less than half of graphemes were produced correctly relative to the target. This pattern of errors indicates that the perisylvian group was not reliant on a phonological strategy, and that the majority of their incorrect spellings resembled the target orthographically.

Fig. 5.

Spelling error types in each group.

In contrast to the perisylvian group, Fig. 5 shows that the majority of errors in both the extrasylvian and control groups were phonologically plausible. Production of this type of error is indicative of reliance on a sublexical phoneme–grapheme conversion strategy in spelling. The proportion of phonologically plausible errors were compared across the three groups using a one-way ANOVA. This analysis revealed a significant difference between groups for this type of error (F(2, 34) = 16.153, p < .001). Pairwise comparisons revealed that the perisylvian group had significantly fewer phonologically plausible errors compared with the other patient group and the control group. The extrasylvian and control groups, however, did not differ with regard to the proportion of phonologically plausible errors committed. Thus, both extrasylvian patients and controls seem to rely on sublexical phoneme–grapheme conversion when word-specific orthographic information is unavailable.

With regard to nonword spelling, the perisylvian group evidenced far greater difficulty (28% correct) than the extrasylvian (75% correct) and control (97% correct) groups (see Fig. 2). Error analyses for nonword spelling in the perisylvian group revealed that 85% of all errors were phonologically implausible attempts (e.g., flig → felh), 14% of errors were lexicalization errors wherein a real word was produced instead of the nonword target (e.g., flig → flag), and remaining errors were categorized as “no response.” The extrasylvian group’s errors also consisted largely of implausible attempts (94.2%), however; fewer lexicalization errors (5.8%) were committed. Of the few errors produced by normal controls, 70% were phonologically implausible attempts, and the remaining errors were lexicalizations.

3.5. Lesion analysis

Lesion overlap maps for perisylvian patients generated with the MRIcro software program are shown in Fig. 1a. The color scale indicates the number of patients with damage to a given neuroanatomical region. When represented in the standard space of Talairach and Tournoux (1988), the areas of greatest lesion overlap extended in the vertical dimension from z = 3 to z = 33 (Fig. 1a). The most common sites of damage included the posterior inferior frontal gyrus/frontal operculum (BA 44/45), precentral gyrus (BA 6/4) and the insula. Damage to posterior perisylvian regions, including superior temporal gyrus (BA 22) and the supramarginal gyrus (BA 40), was less consistent across participants.

Overlap maps for extrasylvian patients (from Rapcsak & Beeson, 2004) are displayed in Fig. 1b. Areas of greatest overlap extended from z = −32 to z = −20. As reported in Rapcsak and Beeson (2004), the regions most commonly damaged included the lingual, fusiform, and parahippocampal gyri (BA 18/19, 37, 20, 36/28), with extension laterally into inferior/middle temporal gyrus in some cases. Critically, none of the individuals included in the extrasylvian group had evidence of damage to perisylvian cortical areas and only one perisylvian patient had a lesion that extended into areas that were damaged in the extrasylvian group.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study are consistent with the prediction that damage to left perisylvian cortex results in phonological agraphia. Individuals with perisylvian lesions demonstrated poor nonword spelling relative to real word spelling, indicating an inability to generate plausible spellings by way of phoneme-to-grapheme conversion for items lacking a lexical representation. The nonword spelling deficit of perisylvian patients was observed not only in comparison with normal controls but also in contrast to patients with extrasylvian lesions involving left inferior temporo–occipital cortex. Furthermore, a comparison of the relative size of regularity and lexicality effects in the two patient groups highlights contrasting patterns of deficits, reflecting different levels of breakdown in the spelling process. Specifically, the perisylvian group exhibited disproportionate impairment of the sublexical phoneme–grapheme conversion procedure, whereas the extrasylvian group’s deficit in irregular word spelling is suggestive of impaired access to word-specific orthographic information, presumably caused by damage to the orthographic lexicon. These group findings are generally consistent with single case studies reporting a double dissociation between spelling disorders affecting the sublexical versus the lexical–semantic spelling routes (Beauvois & Derouesné, 1981; Shallice, 1981).

In accordance with the literature, most of our patients with phonological agraphia due to perisylvian damage also had difficulty spelling familiar words. In fact, only two individuals in the perisylvian group demonstrated relatively preserved real word spelling: one with 91% and the other with 97% accuracy. These observations suggest that “pure” phonological agraphia is relatively uncommon. One of the individuals with “pure” phonological agraphia in our study had an anterior perisylvian lesion involving Broca’s area, precentral gyrus and the insula, whereas the other patient had a posterior perisylvian lesion with evidence of damage to superior temporal gyrus, supramarginal gyrus, and the insula. However, other patients with similar lesion profiles demonstrated concomitant impairments of real word spelling. It has been suggested that the real word spelling impairment observed in the majority of patients with phonological agraphia reflects additional damage to the lexical–semantic spelling route (e.g., Alexander et al., 1992). Alternatively, the nonword and real word spelling deficits may both be related to damage to phonological representations. Specifically, it has been proposed that orthographic lexical selection is influenced and constrained by sublexical phoneme–grapheme conversion (Hillis & Caramazza, 1991) and/or by input from the phonological lexicon (Ellis, 1982; Margolin, 1984; Patterson & Shewell, 1987). Thus, it may be the case that perisylvian lesions compromise both sub-lexical and word-level phonological inputs to orthography and produce parallel impairments in spelling nonwords and real words. Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed a significant correlation between nonword and real word spelling accuracy in our perisylvian group (r = .73; p = .002).

Although we have elected to discuss our findings within the framework of dual-route models of spelling, it should be noted that our results in patients with phonological agraphia are also consistent with parallel distributed processing (PDP) models of language processing (e.g., Plaut et al., 1996). These models do not postulate separate lexical and sublexical procedures for spelling real words and non-words. Instead, processing for both types of items occurs in an interactive fashion between phonological, orthographic, and semantic units. In such models, damage to phonology is expected to have a disproportionate impact on nonword spelling because unfamiliar combinations of phonological elements are less stable than familiar patterns of activation that correspond to real words (cf. Patterson & Marcel, 1992; Patterson, Suzuki, & Wydell, 1996). Furthermore, phonological representations for lexical items receive an additional source of activation from semantic units that is not available for nonwords. With increasingly severe damage to phonology, however, lexical phonological representations may also become compromised and unstable, resulting in defective spelling of real words. In short, both dual-route and PDP models can account for the frequency-dependent decrement of real word spelling ability in patients with phonological impairment due to perisylvian lesions. Consistent with the proposed phonological deficit, the vast majority of nonword spelling errors committed by the perisylvian group bore little or no phonological resemblance to the target; the remaining few errors were real word responses or lexicalizations. Similarly, error analysis for real words indicated that the perisylvian group was far less likely than extrasylvian patients or normal controls to produce phonologically plausible spelling errors.

With regard to the neural substrates of phonological spelling, the lesion overlap maps presented in Fig. 1a suggest a relationship between damage to perisylvian cortex and phonological agraphia. Regions most often damaged in our patients with phonological spelling impairment included the inferior frontal gyrus/frontal operculum, pre-central gyrus, and the insula, with several patients demonstrating damage to superior temporal gyrus and supramarginal gyrus as well. We recognize that caution must be exercised in interpreting lesion overlap maps. In particular, it is conceivable that the “hotspots” on these maps simply indicate brain regions that are most likely to be damaged in patients with MCA strokes, rather than areas that are directly responsible for our patients’ spelling deficit. For example, Hillis et al. (2004) suggested that the insula might be over-represented in lesion overlap studies due to its high likelihood of sustaining damage following MCA stroke. We note, however, that all previously reported cases of phonological agraphia had evidence of damage to one or more of the perisylvian cortical regions that were involved in our patients (for reviews, see Alexander et al., 1992; Rapcsak & Beeson, 2002). Our results are also consistent with functional imaging studies showing activation in Broca’s area (BA 44/45), precentral gyrus (BA 6/4), the insula, and left superior/middle temporal gyrus (BA 22/21) during sublexical spelling tasks in normal individuals (Beeson & Rapcsak, 2003; Omura et al., 2004). Overall, these findings support the notion that phonological agraphia reflects damage to a distributed network of perisylvian cortical regions involved in phonological processing (Alexander et al., 1992; Kim et al., 2002; Rapcsak & Beeson, 2002).

Evidence from patients with aphasia and functional neuroimaging studies of language processing in normal individuals indicates that the perisylvian regions identified in this study play a critical role in speech production and perception (Binder & Price, 2001; Buchsbaum et al., 2001; Damasio, 2000; Demonet et al., 1992). Imaging studies have also demonstrated prominent activation of these perisylvian cortical areas during tests of phonological awareness that require the identification, maintenance, and manipulation of sublexical phonological information (Burton, Small, & Blumstein, 2000; Seki, Okada, Koeda, & Sadato, 2004; St. Heim et al., 2003). Phonological awareness skills are likely to play an important role in spelling by the sublexical route. Although the distributed neuroanatomy of phonological agraphia documented in our study is consistent with neural systems models of phonological processing, the possibility exists that different perisylvian regions make distinct contributions to spelling performance. As noted earlier, sublexical spelling is a complex process consisting of several cognitive operations, each of which may be selectively impaired in phonological agraphia (Ellis, 1982; Rapcsak & Beeson, 2002; Roeltgen et al., 1983; Shallice, 1981). The respective contribution of different perisylvian regions to these cognitive operations remains to be determined and will require detailed studies of patients with circumscribed cortical lesions.

Table 5.

ANOVA for spelling by the extrasylvian group examining spelling regularity (regular versus irregular) and word frequency (high, medium, low)

| Source | df | MS | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect of regularity | 1 | 8400.52 | 70.96 | .001 |

| Error | 7 | 118.38 | ||

| Main effect of frequency | 2 | 1918.75 | 36.02 | .001 |

| Error | 14 | 53.27 | ||

| Interaction: regularity × frequency | 2 | 402.08 | 6.40 | .011 |

| Error | 14 | 62.80 |

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Mark Borgstrom, statistical consultant at the University of Arizona, for his advice regarding this paper.

Footnotes

This work was funded in part by RO1DC007646 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders and P30AG19610 from the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center. Additional support for the first author came from the University of Arizona Imaging Fellowship.

References

- Alexander MP, Friedman RB, Loverso F, Fischer RS. Lesion localization in phonological agraphia. Brain and Language. 1992;43:83–95. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(92)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter DM, Warrington EK. Transcoding sound to spelling: Single or multiple sound unit correspondence? Cortex. 1987;23:11–28. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(87)80016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter DM, Warrington EK. Category specific phonological dysgraphia. Neuropsychologia. 1995;23:653–666. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(85)90066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvois MF, Derouesné J. Lexical or orthographic agraphia. Brain. 1981;104:21–49. doi: 10.1093/brain/104.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeson PM, Hillis AE. Comprehension and production of written words. In: Chapey R, editor. Language intervention strategies in adult aphasia. 4. Baltimore: Lippencott, Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 572–595. [Google Scholar]

- Beeson PM, Rapcsak SZ. Neural substrates of sublexical spelling [Abstract] Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2003;9:170. [Google Scholar]

- Beeson PM, Rapcsak SZ, Plante E, Chargualaf J, Chung A, Johnson SC, Trouard TP. The neural substrates of writing: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Aphasiology. 2003;17:647–665. [Google Scholar]

- Behrmann M. The rites of righting writing: Homophone mediation in acquired dysgraphia. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1987;4:365–384. [Google Scholar]

- Binder J, Price CJ. Functional Neuroimaging of Language. In: Cabeza R, Kingstone A, editors. Handbook of functional neuroimaging of cognition. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press; 2001. pp. 87–251. [Google Scholar]

- Bolla-Wilson K, Speedie LJ, Robinson RG. Phonologic agraphia in a left-handed patient after a right-hemisphere lesion. Neurology. 1985;35:1778–1781. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.12.1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bub D, Kertesz A. Evidence for lexicographic processing in a patient with preserved written over oral single word naming. Brain. 1982;105:697–717. doi: 10.1093/brain/105.4.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchsbaum B, Hickok G, Humphries C. Role of left posterior superior temporal gyrus in phonological processing for speech perception and production. Cognitive Science. 2001;25(5):663–678. [Google Scholar]

- Burton MW, Small SL, Blumstein S. The role of segmentation in phonological processing: an fMRI investigation. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2000;12:679–690. doi: 10.1162/089892900562309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croisile B, Trillet M, Laurent B, Latombe B, Schott B. Agraphie lexicale por hematome temporo–parietal gauche. Revue Neurologique. 1989;145:287–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio H. The Neural Basis of Language Disorders. In: Chapey R, editor. Language intervention strategies in adult aphasia. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 18–36. [Google Scholar]

- Demonet JF, Chollet F, Ramsay S, et al. The anatomy of phonological and semantic processing in normal subjects. Brain. 1992;115:1753–1768. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.6.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis AW. Spelling and writing (and reading and speaking) In: Ellis AW, editor. Normality and Pathology in Cognitive Functions. London: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 113–146. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RA, Caramazza A. Aspects of the spelling process: evidence from a case of acquired dysgraphia. Language and Cognitive Processes. 1986a;1:263–296. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RA, Caramazza A. Comprehension and production of written words. In: Chapey R, editor. Language intervention strategies in adult aphasia. 4. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1986b. pp. 572–579. The Johns Hopkins University Dyslexia and Dysgraphia Batteries. Published in: Beeson, P. M. & Hillis, A. E. (2001) [Google Scholar]

- Goodman-Schulman R, Caramazza A. Patterns of dysgraphia and the nonlexical spelling process. Cortex. 1987;23:143–148. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(87)80026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield FM, Patterson K. Phonological spelling. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1983;35A:451–468. doi: 10.1080/14640748308402482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis AE, Caramazza A. Mechanisms for accessing lexical representations for output: evidence from a category-specific semantic deficit. Brain and Language. 1991;40:106–144. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(91)90119-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis AE, Work M, Barker PB, Jacobs MA, Breese EL, Maurer K. Re-examining the brain regions crucial for orchestrating speech articulation. Brain. 2004;127:1479–1487. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard D, Patterson K. Pyramids and Palm Trees: A Test of Semantic Access from Pictures and Words. Bury St. Edmunds: Thames Valley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. Boston Naming Test. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A. Western aphasia battery. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Na DL. Dissociation of pure Korean words and Chinese-derivative words in phonological dysgraphia. Brain and Language. 2000;74:134–137. doi: 10.1006/brln.2000.2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Chu K, Lee KM, Kim DW, Park SH. Phonological agraphia after superior temporal gyrus infarction. Archives of Neurology. 2002;59:1314–1316. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.8.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera H, Francis WN. A computational analysis of present-day American English. Providence, RI: Brown University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Langmore SE, Canter GJ. Written spelling deficit of Broca’s aphasics. Brain and Language. 1983;18:293–314. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(83)90022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marien P, Pickut BA, Engelborghs S, Martin JJ, DeDeyn PP. Phonological agraphia following a focal anterior insulo-opercular infarction. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39:845–855. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin DI. The neuropsychology of writing and spelling: semantic, phonological, motor and perceptual processes. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1984;36A:459–489. doi: 10.1080/14640748408402172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Honda M, Okada T, Hanakawa T, Toma K, Fukuyama H, Konishi J, Shibasaki H. Participation of the left posterior inferior temporal cortex in writing and mental recall of Kanji orthography: a functional MRI study. Brain. 2000;123:954–967. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.5.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura K, Tsukamoto T, Kotani Y, Ohgami Y, Yoshikawa K. Neural correlates of phoneme-to-grapheme conversion. Neuro-Report. 2004;15:949–953. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200404290-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paivio A, Yuille JC, Madigan SA. Concreteness, imagery and meaningfulness values for 925 words. Journal of Experimental Psychology Monograph Supplement. 1968;76(1):1–25. doi: 10.1037/h0025327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson K, Marcel A. Phonological ALEXIA or PHONOLOGICAL Alexia? In: Alegria J, Holender D, Junca de Morais J, Radeau M, editors. Analytic Approaches to Human Cognition. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1992. pp. 259–274. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson K, Shewell C. Speak and spell: Dissociations and word-class effects. In: Coltheart M, Sartori G, Job R, editors. The Cognitive Neuropsychology of Language. London: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1987. pp. 273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson K, Suzuki T, Wydell T. Interpreting a case of Japanese phonological alexia: the key is in phonology. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1996;13(6):803–822. [Google Scholar]

- Plaut D, McClelland J, Seidenberg M, Patterson K. Understanding normal and impaired word reading: computation principles in quasi-regular domains. Psychological Review. 1996;103:56–115. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp B, Caramazza A. From graphemes to abstract letter shapes: levels of representation in written spelling. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1997;23:1130–1152. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.23.4.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapcsak SZ, Beeson PM. Neuroanatomical correlates of spelling and writing. In: Hillis AE, editor. Handbook on adult language disorders: Integrating cognitive neuropsychology, neurology, and rehabilitation. Philadelphia: Psychology Press; 2002. pp. 71–99. [Google Scholar]

- Rapcsak SZ, Beeson PM. The role of left posterior inferior temporal cortex in spelling. Neurology. 2004;62:2221–2229. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000130169.60752.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeltgen DP. Agraphia. In: Heilman KM, Valenstein E, editors. Clinical neuropsychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Roeltgen DP, Heilman KM. Lexical Agraphia: further support for the two-system hypothesis of linguistic agraphia. Brain. 1984;107:811–827. doi: 10.1093/brain/107.3.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeltgen DP, Heilman KM. Review of agraphia and a proposal for an anatomically based neuropsychological model of writing. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1985;6:205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Roeltgen DP, Sevush S, Heilman KM. Phonological agraphia: writing by the lexical–semantic route. Neurology. 1983;33:755–765. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.6.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki A, Okada T, Koeda T, Sadato N. Phonemic manipulation in Japanese: an fMRI study. Cognitive Brain Research. 2004;20:261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorden C, Brett M. Stereotaxic display of brain lesions. Behavioral Neurology. 2000;12:191–200. doi: 10.1155/2000/421719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shallice T. Phonological agraphia and the lexical route in writing. Brain. 1981;104:413–429. doi: 10.1093/brain/104.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Heim B, Opitz K, Müller K, Friederici A. Phonological processing during language: fMRI evidence for a shared production-comprehension network. Cognitive Brain Research. 2003;16(2):285–296. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(02)00284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain: 3-dimensional proportional system—an approach to cerebral imaging. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Vanier M, Caplan D. CT correlates of surface dyslexia. In: Patterson KE, Marshall JC, Coltheart M, editors. Surface dyslexia: Neuropsychological and cognitive studies of phonological reading. London: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1985. [Google Scholar]