Abstract

Cardiac myxoma is a source of emboli to the central nervous system and elsewhere in the vascular tree. However, nonspecific systemic symptoms and minor embolic phenomena may be overlooked in the absence of any history of cardiac problems. In this situation, cardiac investigations may not be performed, and diagnosis of this rare condition may be delayed until the onset of more significant embolic disease, such as stroke with functional impairment, as in the case reported here. The clinical presentation of cardiac myxoma is discussed, along with appropriate investigations and treatment, which may prevent such sequelae.

Case

A 48-year-old man who presented to the emergency department reported a fall and transient loss of consciousness. The physical examination was limited by the patient's confusional state, but it revealed weakness of the right arm and leg. No seizure had been witnessed. He smoked but had no other conventional vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes or dyslipidemia.

Over the previous year he had reported 4 or 5 syncopal episodes, weight loss of 20 lb (about 9 kg) to 130 lb (about 59 kg), and symptoms of myalgia and arthralgia. His family reported gradual memory impairment and personality change. Investigations before the current event had focused on a possible rheumatological disorder and had revealed elevation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR; peak 74 mm/h), a positive speckled pattern on antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing and a weakly positive result on classical antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (c-ANCA) testing. The results of biopsy of a lower extremity rash were suggestive of livedo reticularis. An autoimmune process such as Wegener's granulomatosis or systemic lupus erythematosus had been suggested, and the patient had started steroid and chloroquine therapy but without improvement.

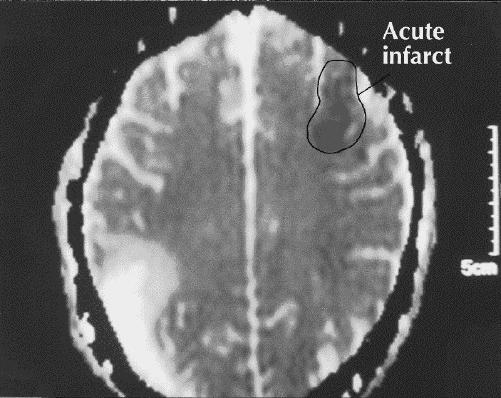

During the current admission, repeat ANA and c-ANCA testing yielded negative results. The ESR remained elevated at 64 mm/h. Electrocardiography (ECG) demonstrated sinus rhythm with left anterior fascicular block. CT of the brain showed previous infarcts of the right parietal and left occipital lobes. MRI demonstrated additional old bihemispheric infarcts and a more recent infarct in the left frontal lobe on apparent diffusion coefficient images (Fig. 1); the latter was the most likely source of the patient's acute symptoms. The results of magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) were unremarkable.

Fig. 1: MRI of the brain (apparent diffusion coefficient image) shows old bihemispheric infarcts and a more recent left frontal infarct (highlighted).

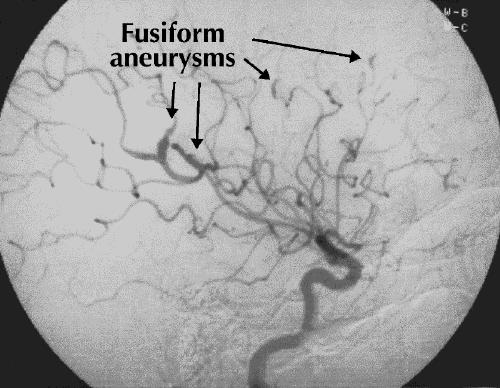

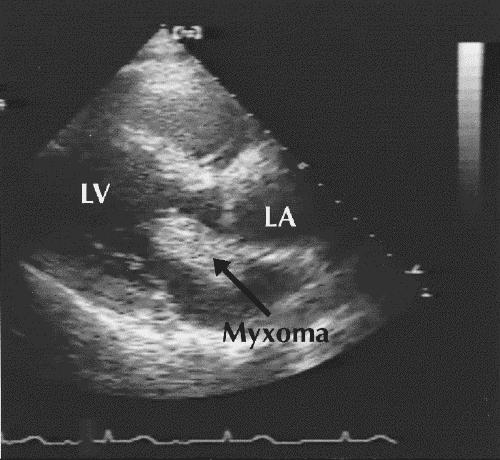

Cerebral angiography revealed multiple, bilateral fusiform aneurysms throughout the anterior and posterior circulations (Fig. 2). These findings, along with the bilateral distribution of cerebral infarction, suggested a proximal embolic source. Transthoracic echocardiography identified a left atrial myxoma (4 х 2.5 х 2.5 cm) prolapsing through the mitral valve in diastole (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2: Cerebral angiogram shows multiple fusiform aneurysms (highlighted).

Fig. 3: Echocardiogram shows the left atrial myxoma (highlighted). LV = left ventricle, LA = left atrium.

The myxoma, of which there was no known family history, was resected without complications 11 days after admission. Steroids were gradually reduced and stopped postoperatively. The ESR fell initially to 16 mm/h and then to 4 mm/h at follow-up 3 months after the surgery. The patient was subsequently referred for rehabilitation for residual right-sided weakness and gait unsteadiness. Formal neuropsychological testing demonstrated deficits in concentration, attention, executive function, visuospatial function and memory. These were thought to be consistent with the ischemic brain damage.

Comments

Atrial myxoma, the most common benign cardiac tumour, is found more commonly in young adults with stroke or transient ischemic attack (1 in 250) than in older patients with these problems (1 in 750).1 The annual incidence is 0.5 per million population,2 with 75% of cases occurring in the left atrium. There is a 2:1 female preponderance,3 and the age at onset is usually between 30 and 60 years. Delay in diagnosis from symptom onset may range from 1 to 126 months.3

Although atrial myxoma is mostly sporadic, at least 7% of cases are familial.4 The best described familial type is Carney complex, characterized by cutaneous spotty pigmentation, cutaneous and cardiac myxomas, nonmyxomatous extracardiac tumours and endocrinopathies. It is transmitted in an autosomal dominant manner, through a causative mutation of the PRKAR1α gene located on the long arm of chromosome 17 (17q22-24 region).5

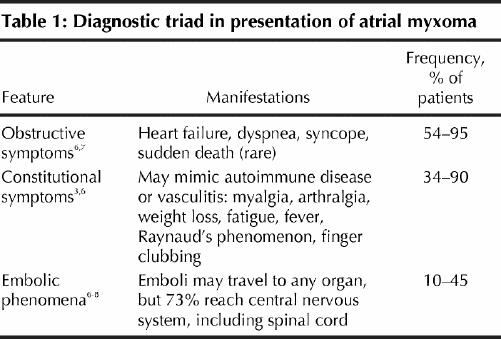

The presentation of atrial myxoma often comprises a diagnostic triad (Table 1). Active illness is often accompanied by elevation of ESR and C-reactive protein, hyperglobulinemia and anemia. Constitutional symptoms may be mediated by interleukin-6, produced by the myxoma itself.9

Table 1

Strokes are often recurrent10 and may be embolic or hemorrhagic, the presentation ranging from progressive multi-infarct dementia11 to massive embolic stroke causing death.12 Because tumour fragments or adherent thrombus may embolize, anticoagulation may not be protective.13 The multiple, bilateral fusiform aneurysms14 commonly found on peripheral arterial branches predispose the patient to cerebral hemorrhage.14 As in the patient described here, MRA may miss intracranial aneurysms less than 3 mm in diameter and is inferior to conventional angiography in this regard.15

The presence of embolic phenomena, especially in young patients with neurological symptoms, should prompt early neuroimaging and echocardiography, even in the absence of ECG or auscultation abnormalities. Auscultation abnormalities may be absent in 36% of patients with myxoma, and a murmur suggestive of mitral stenosis has been reported in only 54%.1 Transesophageal echocardiography, which has been reported as having 100% sensitivity for cardiac myxoma,16 is preferred over transthoracic echocardiography. Transesophageal echocardiography may also improve the detection of other major cardioembolic sources (e.g., intracardiac thrombus, vegetations or aortic arch plaque), as well as less common potential sources (e.g., patent foramen ovale, atrial septal aneurysm or left ventricular aneurysm).17

Cardiac MRI can assist in delineating tumour size, attachment and mobility.18 This information may be helpful in surgical resection, which, because of the risk of further embolization, should not be deferred even in asymptomatic cases discovered incidentally. Resection may lead to normalization of serum interleukin-6 levels and resolution of constitutional symptoms,9 and the intracranial aneurysms may regress and resolve.19

Neurological sequelae after resection are rare but may occur without recurrence of the cardiac tumour. Instead of regressing, aneurysms may enlarge or appear for the first time.20 Tumour fragments that have metastasized to the vessel walls may enlarge, causing vessel occlusion and delayed infarction,14 or they may penetrate through the vessel wall, forming intra-axial metastases.21

Primary tumours recur in only 1% to 3% of sporadic cases, often because of inadequate resection.4 For patients with sporadic myxoma, annual review with echocardiography is suggested for a period of 3 to 4 years, when the risk of recurrence is greatest.22 For Carney complex, which has a recurrence rate of up to 25%, lifetime annual review with familial screening is recommended.23

Conclusions

The diagnosis of atrial myxoma can be elusive, especially when the symptoms suggest a systemic illness. In the case reported here, the significance of these symptoms became apparent when the patient presented acutely with a motor deficit as a result of cerebrovascular embolism. The presence of bihemispheric infarction focused subsequent investigations on the possibility of a proximal source of embolization, which resulted in identification of the causative atrial myxoma.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Drs. O'Rourke, Dean and Mouradian were responsible for the conception of the article, the literature search and writing of the initial drafts. Drs. Akhtar and Shuaib reviewed and contributed suggestions and revisions to the final drafts of the article.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Fintan O'Rourke, Stroke Prevention Clinic, Room 1F2.16, University of Alberta Hospital, Mackenzie Health Sciences Centre, 8440-112 St., Edmonton AB T6G 2B7; fax 780 407-6020; forourke@ualberta.ca

References

- 1.Hart RG, Albers GW, Koudstaal PJ. Cardioembolic stroke. In: Ginsberg MD, Bogousslavsky J, editors. Cerebrovascular disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. London: Blackwell Science; 1998. p. 1392-429.

- 2.Pinede L, Duhaut P, Loire R. Clinical presentation of left atrial myxoma. A series of 112 consecutive cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2001;80(3):159-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.MacGowan SW, Sidhu P, Aherne T, Luke D, Wood AE, Neligan MC, et al. Atrial myxoma: national incidence, diagnosis and surgical management. Ir J Med Sci 1993;162(6):223-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.McCarthy PM, Piehler JM, Schaff HV, Pluth JR, Orszulak TA, Vidaillet HJ Jr, et al. The significance of multiple, recurrent and “complex” cardiac myxomas. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1986;91:389-96. [PubMed]

- 5.Kirschner LS, Carney JA, Pack SD, Taymans SE, Giatzakis C, Cho YS, et al. Mutations of the gene encoding the protein kinase type I-alpha regulatory subunit in patients with the Carney complex. Nat Genet 2000;26:89-92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Markel ML, Waller BF, Armstrong WF. Cardiac myxoma: a review. Medicine (Baltimore) 1987;66:114–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.St John Sutton MG, Mercier LA, Giuliani ER, Lie JT. Atrial myxomas: a review of clinical experience in 40 patients. Mayo Clin Proc 1980;55:371-6. [PubMed]

- 8.Blondeau P. Primary cardiac tumours. French studies of 533 cases. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1990;38:192–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Mendoza CE, Rosado MF, Bernal L. The role of interleukin-6 in cases of cardiac myxoma. Clinical features, immunologic abnormalities, and a possible role in recurrence. Tex Heart Inst J 2001;28(1):3-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Kessab R, Wehbe L, Badaoui G, el Asmar B, Jebara V, Ashoush R. Recurrent cerebrovascular accident: unusual and isolated manifestation of myxoma of the left atrium. J Med Liban 1999;47(4):246-50. In French. [PubMed]

- 11.Hutton JT. Atrial myxoma as a cause of progressive dementia. Arch Neurol 1981;38(8):533. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Bienfait HP, Moll LC. Fatal cerebral embolism in a young patient with an occult left atrial myxoma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2001;103(1):37-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Knepper LE, Biller J, Adams HP Jr, Bruno A. Neurologic manifestations of atrial myxoma. A 12-year experience and review. Stroke 1988;19(11):1435-40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Price DL, Harris JL, New PF, Cantu RC. Cardiac myxoma. A clinicopathologic and angiographic study. Arch Neurol 1970;23(6):558-67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Adams WM, Laitt RD, Jackson A. The role of MR angiography in the pretreatment assessment of intracranial aneurysms: a comparative study. Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21(9):1618-28. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Engberding R, Daniel WG, Erbel R, Kasper W, Lestuzzi C, Curius JM, et al. Diagnosis of heart tumours by transesophageal echocardiography: a multicentre study in 154 patients. Eur Heart J 1993;14:1223-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Kapral MK, Silver FL. Preventive health care, 1999 update: 2. Echocardiography for the detection of a cardiac source of embolus in patients with stroke. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. CMAJ 1999;161(8):989-96. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Reddy DB, Jena A, Venugopal P. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in evaluation of left atrial masses: an in vitro and in vivo study. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1994;35(4):289-94. [PubMed]

- 19.Damasio H, Seabra-Gomes R, da Silva JP, Damasio AR, Antunes JL. Multiple cerebral aneurysms and cardiac myxoma. Arch Neurol 1975;32(4):269-70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Roeltgen DP, Weimer GR, Patterson LF. Delayed neurologic complications of left atrial myxoma. Neurology 1981;31(1):8-13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Bazin A, Peruzzi P, Baudrillard JC, Pluot M, Rousseaux P. Cardiac myxoma with cerebral metastases. Neurochirurgie 1987;33(6):487-9. [PubMed]

- 22.Semb BK. Surgical considerations in the treatment of cardiac myxoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1984;87(2):251-9. [PubMed]

- 23.Basson CT, Aretz HT. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 11-2002. A 27-year-old woman with two intracardiac masses and a history of endocrinopathy. N Engl J Med 2002;346(15):1152-8. [DOI] [PubMed]