Abstract

Syn- and anti-1-amino-3-[2-iodoethenyl]-cyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid (syn-, anti-IVACBC 16, 17) and their analogue 1-amino-3-iodomethylene-cyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid (gem-IVACBC 18) were synthesized and radioiodoinated with [123I] in 34%–43% delay-corrected yield. All these amino acids entered 9L gliosarcoma cells primarily via L-type transport in vitro with high uptake of 9–11%ID/1×106 cells. Biodistribution studies of [123I]16, 17 and 18 in rats with 9L gliosarcoma brain tumors demonstrated high tumor to brain ratios (4.7–7.3:1 at 60 minutes post injection). In this model, syn-, anti- and gem-[123I]IVACBC are promising radiotracers for SPECT brain tumor imaging.

The development of radiotracers for detecting cancer in patients is a major focus of radiopharmaceutical research. A number of classes of compounds that accumulate preferentially in neoplastic tissues have been investigated for this purpose, including metabolically based radiotracers such as amino acids. Amino acids are important biological substrates in virtually all biological processes and are required nutrients for cell growth. A variety of radiolabeled amino acids have been developed as potential tumor imaging agents for positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT). The amino acids developed for oncologic imaging can be divided into two major categories, naturally occurring amino acids and their structurally similar analogues, and non-natural amino acids. One potential advantage of non-natural amino acids over naturally occurring amino acids is their increased metabolic stability. Additionally, non-natural amino acids may not participate effectively in protein synthesis. These properties can potentially simplify the analysis of tracer kinetics with non-natural amino acids.

Non-natural amino acid PET tracers anti-1-amino-3-[18F]fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid (anti-[18F]FACBC)1, 2 and syn- and anti-1-amino-3-[18F]fluoromethyl-cyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid (syn-and anti-[18F]FMACBC)3 have been prepared in this lab and have shown great potential in imaging brain and prostate cancer.4–6 The radionuclides used for PET and SPECT have complementary properties. While PET has higher temporal and spatial resolution, SPECT radionuclides possess certain advantages. Most commonly used SPECT radionuclides, including iodine-123 and technecium-99m, are available without an onsite cyclotron. SPECT radionuclides have longer half-lives (e.g. 13.2 hours for iodine-123 and 6 hours for technecium-99m) than most widely used PET radionuclides (e.g. 110 minutes for fluorine-18 and 20 minutes for carbon-11). The longer half-lives of most SPECT radionuclides facilitate chemical synthesis, allow for the study of processes that occur over longer time courses and are suitable for remote distribution of the radiolabeled product to sites that do not have radiosynthetic capabilities. There are currently fewer radiolabeled amino acids suitable for SPECT than for PET, with [123I]IMT7 representing the most widely used radiolabeled amino acid for SPECT.

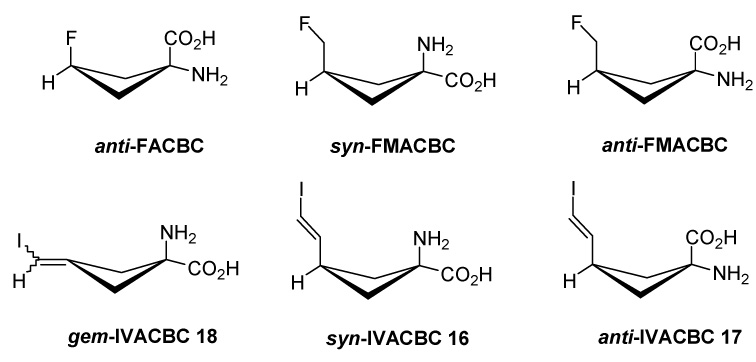

In effort to develop the radiotracers for SPECT tumor imaging, we report here the syntheses of syn-,anti-1-amino-3-[2-iodoethenyl]-cyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid (syn-, anti-IVACBC 16, 17), 1-amino-3-iodomethylene-cyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid (gem-IVACBC 18), which are analogues of FACBC and FMACBC, their [123I] radiolabeling and biological evaluation with a rat 9L gliosarcoma cell line and in Fischer rats with 9L tumors implanted intracranially (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structures of FACBC and its fluoro and iodovinyl analogues.

The syntheses of syn- and anti-IVACBC stannylated precursors for radiolabeling were prepared in a series of synthetic steps starting from allylbenzylether (1), which is shown in Scheme 1. The intermediates, the syn- and anti-1-[N-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino]-3-hydroxymethyl-cyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid tert-butyl esters (2, 3) were prepared in 7 steps according to Martarello’s method.3 The alcohol isomers were transformed to the corresponding aldehydes (4, 5) by Swern oxidation.8 In the key synthetic step, reaction of 4 or 5 with iodoform in tetrahydrofuran using chromium(II) chloride as a catalyst gave exclusively trans (E) isomers of 6 and 79–12 as determined by 1H NMR. The stannyl labeling precursors syn- and anti-1-[N-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino]-3-[2-trimethylstannylethenyl]-cyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid tert-butyl esters 8 and 9 were prepared from vinyl iodides 6 and 7, respectively, using hexamethylditin and catalytic tetrakis(triphenylphosphine) palladium(0).12, 13

Scheme 1 a. Syntheses of syn- and anti-IVACBC stannylated precursors 8 and 9.

aReagents and conditions: (a) (COCl)2, DMSO, DCM, −50°C then Et3N, 79% (4); 64% (5). (b) CHI3, CrCl2, THF, 0°C – rt, 59% (6); 60% (7). (c) (CH3)3Sn-Sn(CH3)3, Pd0(PPh3)4, THF, 50–60°C, 26% (8); 18% (9).

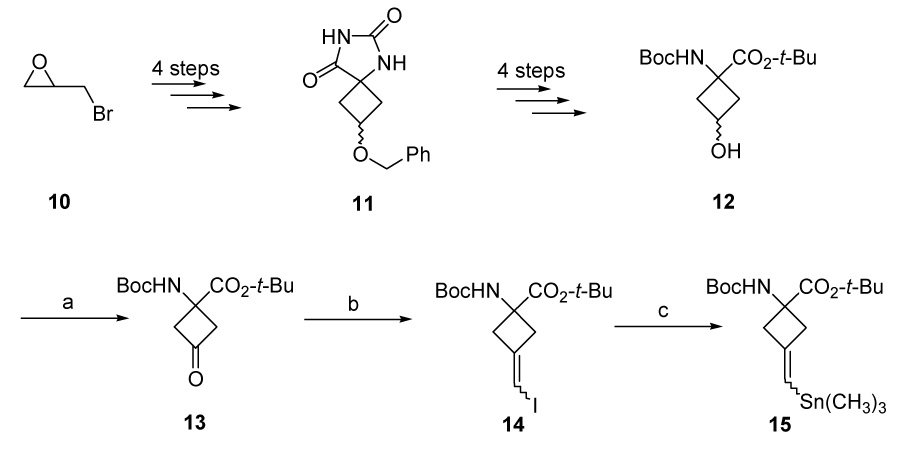

The protected gem-IVACBC stannylated precursor for radiolabeling was prepared starting from epibromohydrin (10). The key intermediate, a 5:1 mixture of syn/anti-5-(3-benzyloxycyclobutane)hydantoins (11) was prepared in 4 steps as described previously,1 and hydrolyzed at 120°C with 3N NaOH to the syn/anti-1-amino-3-benzyloxycyclobutane-1-carboxylic acids. Subsequent N-protection with di-tert-butyl dicarbonate and tert-butyl esterification with tert-butyl 2,2,2-trichloroacetimidate followed by Pdo catalyzed debenzylation3 gave the syn/anti-1-[N-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino]-3-hydroxy-cyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid tert-butyl esters (12). The alcohols were transformed to the corresponding ketone (13) by Swern oxidation followed by reaction with CHI3/CrCl2 to form protected gem-IVACBC (14) which was treated with (SnMe3)2/Pd0(PPh3)4 to afford 1-[N-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino]-3-trimethylstannylmethylene-cyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid tert-butyl ester (15) as the radiolabeling precursor12 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2 a. Synthesis of gem-IVACBC stannylated precursor 15.

aReagents and conditions: (a) (COCl)2, DMSO, DCM, −50°C then Et3N, 92% (13). (b) CHI3, CrCl2, THF, 0°C – rt, 27% (14). (c) (CH3)3Sn-Sn(CH3)3, Pd0(PPh3)4, THF, 50–60°C, 76% (15).

The 127I references of syn-, anti- and gem-IVACBC 16, 17 and 18 were prepared from the N-Boc amino acid tert-butyl esters 6, 7 and 14, respectively, by treatment of trifluoroacetic acid and purified by ion-retardation resin chromatography12 (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3 a. Syntheses of syn-, anti- and gem-IVACBC 16, 17 and 18.

aReagents and conditions: (a) TFA, DCM, rt, 78% (16); 71% (17); 68% (18).

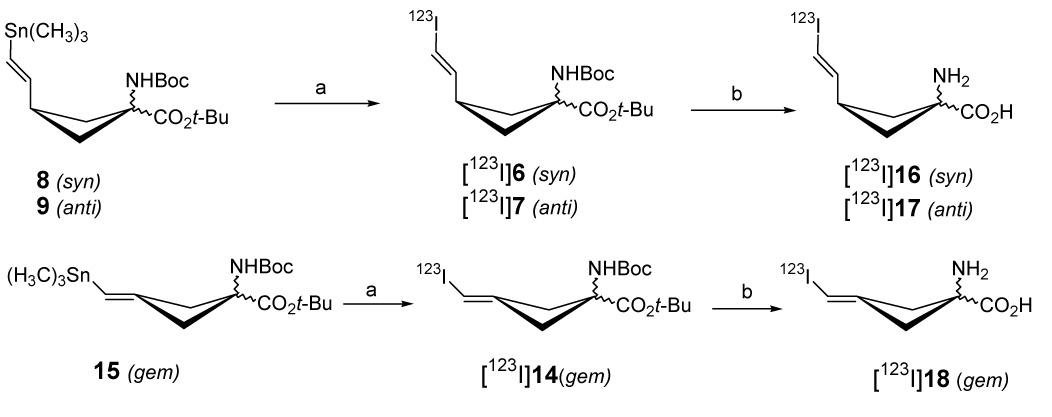

Radioiodinated syn-, anti-[123I]IVACBC 16, 17 and gem-[123I]IVACBC 18 were prepared using no-carrier-added (NCA) sodium [123I]iodide under oxidizing conditions followed by deprotection with aqueous hydrochloric acid12 (Scheme 4). The radioiodinated products were purified by ion-retardation resin chromatography. The procedure required approximately 100 min with decay-corrected yields (d.c.y.) of 41.9±18.3% (n=17, syn-[123I]IVACBC 16), 43.4±23.0% (n=12, anti-[123I]IVACBC 17) and 33.7±18.2% (n=7, gem-[123I]IVACBC 18) in over 99% radiochemical purity as measured by radiometric TLC. Based on 200 nmole of tin precursor utilized for labeling and approximate yields of 1 mCi of product, the minimum specific activities for syn-, anti- and gem-[123I] 16, 17, 18 are estimated at 5 mCi/µmole. The final product was not assayed for the presence of tin.

Scheme 4 a. Radiosyntheses of syn-, anti- and gem-IVACBC 16, 17 and 18.

aReagents and conditions: (a) [123I]NaI, H2O2, H+, rt. (b) TFA, DCM, 85 °C, 42% (16); 43% (17); 34% (18).

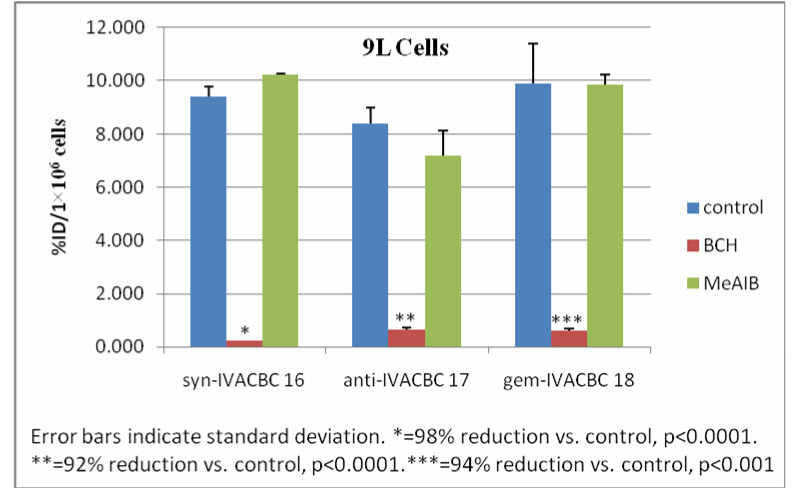

The in vitro studies were performed in 9L rat gliosarcoma cells in Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C with or without inhibitors to evaluate the compounds tumor cell uptake and transport mechanism. 10 mM 2-amino-bicyclo[2.2.1]-heptane-2-carboxylic acid (BCH) and N-methyl-α-aminoisobutyric acid (MeAIB) were used as L- and A-type amino acid transport inhibitors, respectively. The results of these amino acid uptake assays are depicted in Figure 2. In the absence of inhibitors, [123I]IVACBC 16, 17 and 18 showed high levels of intracellular accumulation, 8.4–9.9% of the initial dose per million cells (%ID/1×106 cells) in 9L gliosarcoma cells. In the presence of BCH, 92.3–97.5% of inhibition was observed in all these compounds compared to controls (p<0.001 in all cases, 1-way ANOVA). In contrast, no significant uptake inhibition occurred with MeAIB for 16 and 18 and 14.3% inhibition for 17 relative to controls. These results demonstrate that compounds 16, 17 and 18 are selective substrates for L-type amino acid transport in 9L gliosarcoma cells in vitro.

Figure 2.

9L cell uptake and inhibition assays with [123I]16, [123I]17 and [123I]18.

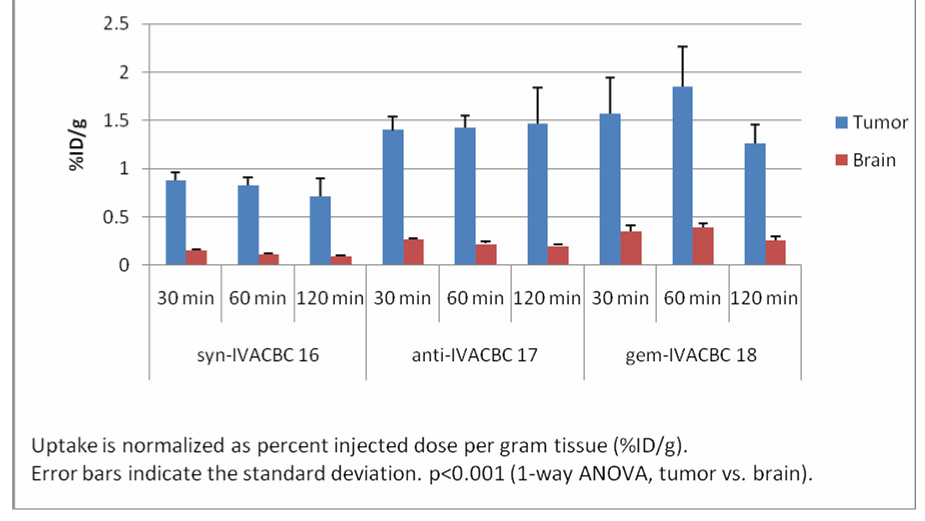

The in vivo biodistribution studies were performed in Fischer rats with 9L tumors implanted intracranially. The radioactivity in tumors and in normal tissues of tumor-bearing rats (n=5 each time point) was calculated at 30, 60, 120 min post injection (p.i.) and normalized as percent injected dose per gram tissue (%ID/g). The uptake of radioactivity of [123I]IVACBC 16, 17 and 18 in tumor and brain is presented in Figure 3. The experiments showed that these amino acids had rapid and prolonged accumulation in tumors, ranged from 0.83 to 1.85 %ID/g and was significantly higher than in normal brain tissue (p<0.001 at all time points, 1-way ANOVA). The uptake in normal brain tissue was less than 0.4%ID/g at all time points for all these compounds thus the tumor to normal brain uptake ratios were 7.3:1, 6.5:1 and 4.7:1 at 60 min p.i. for [123I]IVACBC 16, 17 and 18, respectively. Low uptake was found in heart, liver, lung, bone and thyroid. The low thyroid uptake with all radiotracers indicates that free iodide was not generated during the time course of the study. The uptake of radioactivity of [18F] labeled anti-FACBC2, syn-FMACBC3 and anti-FMACBC3 in tumors at 60 min p.i. were 1.72, 1.59 and 2.50 %ID/g in the same animal model, respectively, which resulted in tumor to brain ratios of 6.6:1, 6.9:1 and 8.9:1, respectively.2, 3 Thus, the characteristics of candidate compounds 16, 17 and 18 are comparable with anti-FACBC, syn-FMACBC and anti-FMACBC, by entering 9L cells via L-type transport system in vitro and showing high levels of uptake in 9L brain tumors in vivo in comparison to normal brain.

Figure 3.

Radioactive uptake in tumor and brain of 9L tumor-bearing Fisher rats with [123I]IVACBC 16, 17 and 18.

In summary, three new SPECT tumor imaging agents, syn-, anti- and gem-IVACBC 16, 17 and 18 have been synthesized, [123I] labeled and biologically evaluated. All these compounds demonstrated high levels of tumor uptake in vitro and in vivo in a 9L rat gliosarcoma brain tumor model and they are L-type amino acid transporter substrates. These results are comparable with those of anti-FACBC, syn-FMACBC and anti-FMACBC in the same animal model, which support the candidacy of syn-, anti-and gem-IVACBC 16, 17 and 18 as promising SPECT brain tumor imaging agents.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Bing Wang of the NMR Center of Emory University for his assistance with NMR studies and Zhaobin Zhang for his assistance with the in vivo studies. Research supported by Nihon Medi-Physics Co., Ltd.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McConathy J, Voll RJ, Yu W, Crowe RJ, Goodman MM. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 2003;58:657. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(03)00029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shoup TM, Olson J, Hoffman JM, Votaw J, Eshima D, Eshima L, Camp VM, Stabin M, Votaw D, Goodman MM. J. Nucl. Med. 1999;40:331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martarello L, McConathy J, Camp VM, Malveaux EJ, Simpson NE, Simpson CP, Olson JJ, Bowers GD, Goodman MM. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:2250. doi: 10.1021/jm010242p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nye JA, Schuster DM, Yu W, Camp VM, Goodman MM, Votaw JR. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2007;48:1017. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.040097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oka S, Hattori R, Kurosaki F, Toyama M, Williams LA, Yu W, Votaw JR, Yoshida Y, Goodman MM, Ito O. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2007;48:46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuster DM, Votaw JR, Nieh PT, Yu W, Nye JA, Master V, Bowman FD, Issa MM, Goodman MM. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2007;48:56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jager PL, Vaalburg W, Pruim J, de Vries EG, Langen KJ, Piers DA. J. Nucl. Med. 2001;42:432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mancuso AJ, Swern D. Synthesis. 1981;3:165. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takai K, Nitta K, Utimoto K. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:7408. doi: 10.1021/ja00279a068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Lera AR, Torrado A, Iglesias B, Lopez S. Tetrahedron Letters. 1992;33:6205. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wulff WD, Powers TS. Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1993;58:2381. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu W, McConathy J, Olson JJ, Camp VM, Goodman MM. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:6718. doi: 10.1021/jm070476u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panekand JS, Jain NF. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:2747. doi: 10.1021/jo001767c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]