Abstract

The epidemiological study of hypersomnia symptoms is still in its infancy; most epidemiological surveys on this topic were published in the last decade. More than two dozen representative community studies can be found. These studies assessed two aspects of hypersomnia: excessive quantity of sleep and sleep propensity during wakefulness (excessive daytime sleepiness). The prevalence of excessive quantity of sleep when referring to the subjective evaluation of sleep duration is around 4% of the population. Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) has been mostly investigated in terms of frequency or severity; duration of the symptom has rarely been investigated. EDS occurring at least 3 days per week has been reported in between 4% and 20.6% of the population, while severe EDS was reported at 5%. In most studies men and women are equally affected. In the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, hypersomnia symptoms are the essential feature of 3 disorders: insufficient sleep syndrome, hypersomnia (idiopathic, recurrent or posttraumatic) and narcolepsy. Insufficient sleep syndrome and hypersomnia diagnoses are poorly documented. The co-occurrence of insufficient sleep and EDS has been explored in some studies and prevalence has been found in around 8% of the general population. However, these subjects often have other conditions such as insomnia, depression or sleep apnea. Therefore, the prevalence of insufficient sleep syndrome is more likely to be between 1% and 4% of the population. Idiopathic hypersomnia would be rare in the general population with prevalence, around 0.3%. Narcolepsy has been more extensively studied, with a prevalence around 0.045% in the general population. Genetic epidemiological studies of narcolepsy have shown that between 1.5% and 20.8% of narcoleptic individuals have at least one family member with the disease. The large variation is mostly due to the method used to collect the information on the family members; systematic investigation of all family members provided higher results. There is still a lot to be done in the epidemiological field of hypersomnia. Inconsistencies in its definition and measurement limit the generalization of the results. The use of a single question fails to capture the complexity of the symptom. The natural evolution of hypersomnia remains to be documented.

Keywords: epidemiology, excessive sleepiness, hypersomnia, narcolepsy, genetic epidemiology

1 INTRODUCTION

Sleep and its functions have fascinated philosophers and scientists for as long as writing reports can be traced. Over time, we have “civilized” sleep, learning to control and delineate circumstances in which it can occur and its duration. Although everyone agrees that sleeping is important, it is often the first “expendable” commodity in our busy lives. There are, however, costs associated with this practice. One of them is excessive sleepiness. Sleep debt is not the only cause for excessive sleepiness but it account for a large part of it.

The term “excessive daytime sleepiness” is often used interchangeably with “hypersomnia.” This usage is partly correct; hypersomnia is a broader symptom including extended nocturnal sleep, unplanned daytime sleep and an inability to remain awake or alert in situations where it is required (excessive sleepiness). There is also a growing trend in labeling excessive sleepiness as a disease or a disorder. So far, there is no data supporting this claim. Excessive daytime sleepiness is not a disease or a disorder; it is a symptom of a sleep disorder or of another disease. In the latest edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-2), it is listed as an essential feature (i.e., obligatory for the diagnosis) in three types of sleep disorders: behaviorally induced insufficient sleep syndrome, hypersomnia and narcolepsy. Table 1 details the different diagnoses and their clinical and pathologic subtypes. A total of 12 different diagnoses involving excessive sleepiness as an essential feature are described and 7 of them are break down in different subtypes.

Table 1.

Hypersomnia diagnoses and clinical subtypes in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-2)

| Behaviorally induced insufficient sleep syndrome | |

| Narcolepsy: | Hypersomnia: |

|

|

As we will see, epidemiological studies conducted in the general population have mostly focused on excessive daytime sleepiness rarely assessing nocturnal and diurnal sleep quantity. The first part of this article reviews epidemiological studies conducted in the general population on hypersomnia as a symptom. The second part presents epidemiological data on the three types of sleep disorders for which hypersomnia is an essential feature, including genetic epidemiology.

2 HYPERSOMNIA SYMPTOMS

Generally speaking, surveys that investigate hypersomnia symptoms in the general population can be divided into two categories: those measuring excessive quantity of sleep and those assessing sleep propensity during wakefulness.

2.1 Excessive quantity of sleep

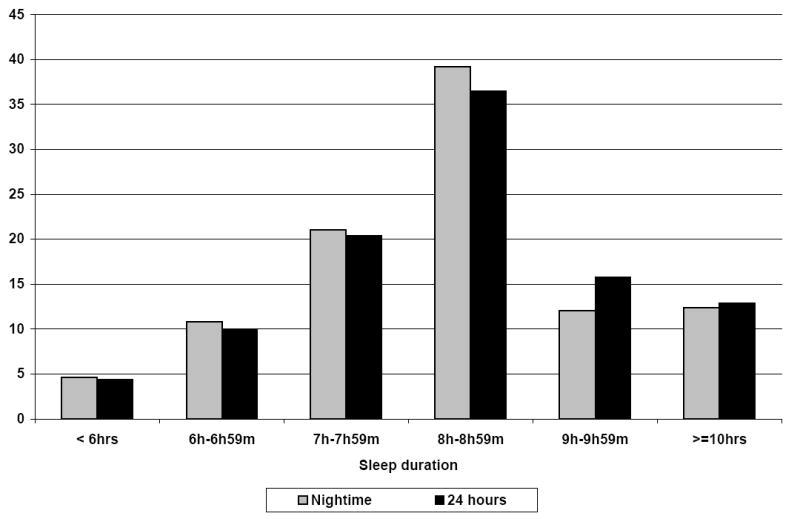

Excessive quantity of sleep refers to getting too much sleep or taking naps during the daytime. Usually, studies that have assessed whether individuals were getting too much sleep only inquired about the subjective evaluation of sleep quantity; i.e., if, according to the subject, he or she estimated sleeping too much. This occurs rather frequently in the general population: between 2.8% and 9.5% answered positively to this type of question (Table 2). Surprisingly, studies never cross-compared this information with sleep duration to verify the correlation between the two. We did this exercise in a European sample of 18,980 individuals. It was found that fewer than 30% of individuals claiming they were getting too much sleep slept nine hours or more per 24-hour period (Fig. 1). More specifically, individuals with bipolar disorder (OR 2.6), generalized anxiety disorder (OR: 2.2), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OR 2.1), panic (OR: 1.9) or posttraumatic stress disorder (OR: 1.9) are twice more likely to report getting too much sleep. It is also reported twice more often by individuals younger than 30 years.

Table 2.

Excessive quantity of sleep in general population studies

| Authors | N | Age | Sample selection | Type of interview | Description | Prevalence (%) (M/F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bixler et al., (58) Los Angeles, USA, 1979 | 1006 | ≥ 18 | Random stratified sample | Face-to-face in household | Sleep too much | 4.2 |

| Ford & Kamerow (24) Baltimore, Durham, Los Angeles, USA, 1989 | 7954 | ≥ 18 | Household probability sample | Face-to-face in household | Sleep too much lasting 2 weeks or more, and professional consultation, sleep enhancing medication intake, or interfere a lot with daily life | 2.8/3.5 |

| Téllez-Lòpez et al. (8) Monterrey, Mexico, 1995 | 1000 | ≥ 18 | Not specified | Face-to-face in household | Getting too much sleep | 9.5 |

| Breslau et al., (59) Southeast Michigan, USA, 1996 | 1,007 | 21-30 | Members of health maintenance organization (HMO) | Face-to-face in household | Sleep too much lasting 2 weeks or more, and professional consultation, sleep enhancing medication intake, or interfere a lot with daily life | 16.3 |

| Ohayon et al (18) United Kingdom | 4972 | ≥ 15 | 2 stages: Random stratified sample + Household probability sample | Telephone | Getting too much sleep | 3.2 |

| Roberts et al., (60) Alameda county, CA, USA, 1999 | 2,730 | 46-102 | General population subjects selected in 1965 and follow-up every 10 years | Mail questionnaire | Sleeping too much | 5.3 |

Figure 1.

Distribution of subjects sleeping too much by nighttime and 24-hours sleep duration

2.2 Sleep propensity during wakefulness

Sleep propensity during wakefulness in situations of diminished attention refers to excessive daytime sleepiness. Its definition and measurement varied nearly as much as the number of community surveys that investigated it (Table 3). Most of the studies limited the assessment of daytime sleepiness to a single question answered by either “yes or no,” a severity scale or a frequency scale. Duration of daytime sleepiness was rarely examined.

Table 3.

Sleep propensity during wakefulness in general population studies

| Frequency

|

Severity

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, year, place | N (age range) | Prevalence | Author, year, place | N (age range) | Prevalence |

| Liljenberg et al., 1988, 2 counties in Sweden a (10) | 3,557 (30-65) | 5.3% | Gislason & Almqvist 1987, Uppsala, Sweden (17) | 3,201 men (30-69) | M:16.7% S: 5.7% |

| Martikainen et al 1992 Tampere, Finland b (13) | 1,190 (36-50) | 9.8% | Ohayon et al., 1997, UK (18) | 4,972 (≥ 15) | M:15.2% S: 5.5% |

| Janson et al., 1995 4 cities in Iceland, Sweden, Belgium b (14) | 2,202 (20-45) | 20.6% | Zielinski et al., 1999, Warsaw district, Poland c (11) | 1,186 (38-67) | 22.3% 0.7% |

| Hublin et al., 1996, Finland b (15) | 11,354 (33-60) | 9% | Nugent et al., 2001, Northern Irland (19) | 2,364 men (≥18) | M: 8.8% S: 11.8% |

| Zielinski et al., 1999, Warsaw district, Poland a (11) | 1,186 (38-67) | 26.1% +pb: 2.5% | Ohayon et al., 2002, Germany, UK, Italy, Spain, Portugal (1) | 18,980 (≥ 15) | M: 8.7% S: 3.8% |

| Liu et al., 2000 Japan a (12) | 3,030 (≥ 20) | 15% | Souza et al., 2002 Campo Grande, Brazil c (22) | 408 (≥ 18) | 18.9% |

| Ohayon et al., 2002 Germany, UK, Italy, Spain, Portugal b (1) | 18,980 (≥ 15) | 4% | Ohayon & Vechierrini, 2002 Paris, France (20) | 1,026 (60-101) | M: 6% S: 5.2% |

| Hara et al., 2004 Bambui, Brazil b (16) | 1066 (≥ 18) | 16.8% | Takegami et al., 2005, Hokkaido region, Japan c (23) | 4,412 (≥ 20) | 8.9% |

| Bixler et al., 2005 Dauphin & Lebanon counties, Pennsylvania, USA (21) | 16,583 (≥20) | 8.7% | |||

Assessed using frequency adverbs

Assessed using number of days per week

Severity assessed with the Epworth sleepiness scale

M = Moderate; S= Severe

Some studies simply asked for the presence of sleepiness during the day. Among the earliest studies, Lugaresi et al (2) investigated the presence of “sleepiness independent of meal times” in a sample of 5,713 individuals aged 3 years and older living in the Republic of San Marino. They obtained a prevalence of 8.7%. Another early study conducted in Tucson (Arizona, USA) with 2,187 subjects aged 18 years and older got a prevalence of 12.3% of men and 11.7% of women falling asleep during the day (3). Three elderly studies assessed the presence of excessive daytime sleepiness by asking the participants if they were “usually sleepy in the daytime.” A first study using 5,201 subjects 65 years and older from the Cardiovascular Health Study (baseline evaluation 1989-1990) reported a prevalence of 17% of men and 15% of women being “usually sleepy in the daytime” (4). In the 1993-94 evaluation, 4,578 adults aged 65 and older answered the Epworth Sleepiness Scale as well as the same question on being “usually sleepy in the daytime” (5). The 85th percentile of the ESS scores (>9 in women and >11 in men) was used to indicate the presence of excessive sleepiness. Being “usually sleepy in the daytime” was reported by 20% of the sample. Using the same question, Foley et al. (6) obtained a prevalence of 7.7% in a sample of 2,346 Japanese-American men. A Canadian study (7) using a national sample of 1,659 elderly who underwent a clinical examination obtained a prevalence of 3.9% of subjects who had a tendency to sleep all day. In this study, sleep disturbance questions were part of the physician’s assessment of depression. A Mexican study (8) reported that 21.5% of the sample experienced a “strong need to sleep during the day.” In Japan, 28,714 participants aged 20 years old and over, part of the Active Survey of Health and Welfare, answered a questionnaire that contained a section on sleep disturbances (9). Excessive sleepiness was assessed with the following question: “Do you fall asleep when you must not sleep (for example, when you are driving a car)?” A total of 2.5% of the sample answered positively to that question.

Frequency of excessive daytime sleepiness was assessed using a graduating scale ranging from never to very often or always; or a frequency per week. A Swedish study reported a prevalence of 5.2% of men and 5.5% of women being often or very often sleepy during the daytime (10) (See table 3 for more details). A Polish study (11) asked its 1,186 participants how often they felt sleepy and wanted to fall asleep in the daytime: 26.1% answered “often” but only 2.5% of the sample reported interference with their activities. A Japanese study (12) reported that 15% of its nationally representative sample reported feeling “often” or “always” excessively sleepy during the daytime.

Martikainen et al. (13) found that 9.8% of Finnish respondents reported being “clearly more tired than others,” experiencing a “daily desire to sleep in the course of normal activities” or feeling “very tired daily.” When using a frequency per week in a sample of young European adults, Janson et al. (14) obtained a prevalence of 20.6% of daytime sleepiness occurring at least three days per week and 5% of daily daytime sleepiness. In the Finnish twin cohort, Hublin et al. (15) found a 9% prevalence of daytime sleepiness occurring daily or almost daily. Ohayon et al. (1) used two definitions of sleepiness in a five-country sample of 18,980 individuals aged 15 years and over. When asked if they had a tendency to fall asleep easily during the daytime and almost anywhere, 4% of the participants answered it occurred at least three days per week. Periods of sudden and irresistible sleep during the daytime were occurring at least 3 days per week in 3.8% of the sample. They also observed important variations between the countries; southern European individuals being less sleepy than the others. Finally, a Brazilian study performed in Bambui (16) with 1,066 subjects observed a prevalence of 16.8% of subjects with daytime sleepiness in the past month occurring at least three days per week.

Severity of excessive daytime sleepiness was assessed using a graduating scale ranging from “not at all” to “extremely” or using the Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS). The Swedish study of Gislason and Almqvist (17) yielded a prevalence rate of 16.7% for moderate daytime sleepiness and of 5.7% for severe daytime sleepiness in a male sample. In a UK study of 4,972 subjects, severe daytime sleepiness was observed in 5.5% of the sample and moderate daytime sleepiness in 15.2% (18). A Northern Irish community study (19) involving 2,364 men aged between 18 and 91 years reported a prevalence of 8.8% of moderate sleepiness and 11.8% of severe sleepiness. In their European study, Ohayon et al. (1) also measured the severity of excessive daytime sleepiness. They observed that 8.7% of their sample reported moderate sleepiness and 3.8% severe sleepiness. Again, they found that southern European countries had lower rates of moderate and severe sleepiness than the other countries. In a similar study conducted in the Paris metropolitan area, Ohayon and Vechierrini (20) reported that 6% of individuals 60 years and older had moderate sleepiness while 5.2% had severe sleepiness. In their study, Bixler et al. (21) assessed excessive daytime sleepiness in central Pennsylvania using two questions: “Do you feel drowsy or sleepy most of the day but manage to stay awake?” and “Do you have any irresistible sleep attacks during the day?” Moderate to severe answers to either one of these questions was considered indicative of excessive daytime sleepiness. Among the 16,583 participants, 8.7% had excessive daytime sleepiness.

Three studies assessed the severity of daytime sleepiness using the ESS. In Poland, the mean ESS score was 8.5 for the total sample (11). Excessive daytime sleepiness in passive situations was found in 22.3% of the sample and excessive daytime sleepiness in active situations in 0.7%. A Brazilian community study (22) of 408 adults from Campo Grande city reported a prevalence of 18.9% of excessive daytime sleepiness using a cut-off score of 11 on the ESS. A Japanese study (23) found that 8.9% of its adult sample had abnormal ESS scores.

There are few studies in the general population that compare different questions and types of assessment of excessive sleepiness (1,11,24). One study (1) found that the three measures of subjective sleepiness had moderate correlation between them (r between 0.22 and 0.35). Another study (24) showed that ESS scores correlated moderately with other subjective measures of excessive sleepiness (being sleepy during the daytime (r=0.36) or being unrested during the daytime (r=0.24)). Unlike insomnia symptoms, excessive sleepiness was not gender-related in many studies. Absence of consistent definitions of excessive daytime sleepiness brings an unacceptable variability for proper prevalence related to age.

Practice point 1.

Epidemiological surveys have measured 2 symptoms of hypersomnia: excess of sleep and sleep propensity during wakefulness.

In both cases, the same limitations are present. Most of the studies based their conclusions from a single question assessing sleep excess or excessive sleepiness. Duration of the symptom was rarely reported.

Sleep excess, when defined as getting too much sleep, is associated with a sleep duration of 9 hours or more in only 30% of the cases.

Three types of sleep disorders have excessive sleepiness as an essential feature: Behaviorally induced insufficient sleep syndrome, hypersomnia and narcolepsy.

3 HYPERSOMNIA-RELATED DIAGNOSES

3.1 Behaviorally induced insufficient sleep syndrome

Insufficient sleep syndrome is characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness in individuals who have shorter sleep duration than what is expected in their age group. Usually, these individuals will get more sleep when they are not following their habitual sleep schedule. Mental disorders, organic diseases and other sleep disorders that could account for the sleepiness have to be ruled out before concluding to the presence of an insufficient sleep syndrome. Some epidemiologic surveys have investigated the association between sleep duration and excessive daytime sleepiness but very few have explored the diagnosis. For example, in the Finnish twin cohort, Hublin et al., (25) defined insufficient sleep as at least one hour difference between nocturnal sleep and sleep report needs of sleep; 20.4% of their sample met this criterion. Of these subjects, about 40% reported daytime sleepiness at least 3 days per week, which means that about 8% of their sample had both insufficient sleep and excessive daytime sleepiness. Yet, differential diagnosis is not applied. Half of these subjects with insufficient sleep had insomnia symptoms and 40% were depressed according to the Beck Depression Inventory. There was no data on possible sleep apnea. Therefore, insufficient sleep syndrome was likely to be lower than 4% in that sample. Another study, conducted in Japan (12), evaluated insufficient sleep by asking subjects if they got as much sleep as they needed. A total of 23.1% answered positively to that question, of which 31.3% had daytime sleepiness. Consequently, the combination of insufficient sleep and daytime sleepiness was present in about 7.2% of their adult sample. However, no differential diagnosis was applied. One study conducted in the United Kingdom (18) applied strict differential diagnosis and found a prevalence of insufficient sleep syndrome at 1.1% in their sample.

3.2 Hypersomnia

To date, there is no epidemiologic information in the general population regarding the different forms of hypersomnia as proposed by the ICSD-2. In fact, data on the prevalence of hypersomnia as a diagnosis are nearly non-existent for the general population. Therefore, we know nothing about demographic characteristics of people with hypersomnia disorders. There is some fragmentary information in three studies. The Epidemiologic Catchment area study conducted in the ‘80s reported a prevalence of 3.4% of hypersomnia (26). However, no differential diagnosis was done, which means that probably many subjects had instead another disorder such as sleep-related breathing disorder or depression. Two general population studies reported a prevalence of hypersomnia diagnosis (all types) at 0.3% in the general population of the United Kingdom (18) and Italy (27).

3.3 Narcolepsy

Reliable estimates of narcolepsy in the general population are difficult to achieve. It requires scanning a large number of individuals to obtain sufficient precision in the prevalence. Consequently, most of the studies presented in this section extrapolated the prevalence of narcolepsy to the general population using clinical samples, specific community groups or advertisements. Only three studies calculated the prevalence of narcolepsy in samples representative of the general population.

3.3.1 Prevalence based on extrapolation

The oldest prevalence study on narcolepsy was published in 1945 (28). This study reported 19 narcoleptics (2 with cataplexy) out of 10,000 black American navy recruits and 3 narcoleptics out of 100,000 white individuals.

The oldest European study was performed in 1957 by Roth (29). The frequency of narcolepsy (with or without cataplexy) in Czechoslovakia was estimated to be between 0.02% and 0.03%, while narcolepsy with cataplexy was assessed to be between 0.013% and 0.02%. These estimates were based on the review of patient material. Findings were extrapolated to the general population.

Two American studies (30,31) recruited participants with sleep attacks and cataplexy through newspaper and television advertisements. The presence of narcolepsy was assessed through telephone interviews. The prevalence of narcolepsy was extrapolated to the general population using the number of newspaper readers and television viewers for the areas (San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles) where the advertisements were posted. Prevalence was estimated at 0.05% for the Bay Area and 0.067% for Los Angeles.

The two oldest studies in Asia were conducted in Japan (32, 33). One involved 12,469 adolescents from Fujisawa and the other involved 4,559 Japanese employees, aged between 17 and 59 years. In the first case, prevalence was estimated at 0.16% for narcolepsy with cataplexy (32) and at 0.18% in the second case (33). The prevalences in these 2 Japanese studies were clearly higher than in the other studies. Whether this is a particularity of the Japanese population or a bias due to the methodology remains to be further investigated. The major weakness of these two studies remains the assessment of cataplexy based on a single question assessing muscle weakness during a strong emotion.

An Italian group (34) reviewed the charts of 2,518 unselected patients, aged 6-92 years, admitted to an Italian general hospital during a one-year period. They found only one case of narcolepsy based on its history, clinical and polysomnographic data. Extrapolation of the frequency of narcolepsy (0.04%) in the general population was calculated using demographic information of the area served by this hospital.

The lowest narcolepsy frequency was observed among Israeli Jews (35). The authors reviewed the clinical material of 1,526 patients complaining of excessive daytime sleepiness (2/3 of the subjects were Jewish and 1/3 Arabs) who consulted a sleep clinic between 1978 and 1986. Narcolepsy was diagnosed in only six patients. Although the authors did not extrapolate their findings to the general population, others did the exercise. The frequency of narcolepsy in the Israeli Jewish general population was estimated to be 0.002%.

Two studies were done in France. In the first study (36), 58,162 male military recruits answered a questionnaire. Narcolepsy, defined as more than two daytime sleep episodes per day accompanied by cataplexy and sleeping difficulties, was found in 0.055% of the sample.

Another study (37), using 14,195 patients 15 years of age or older of all the physicians in the Gard district (South of France), estimated at 0.021% the frequency of narcolepsy. Patients first answered a questionnaire. Possible narcoleptics (n=29) were further interviewed by telephone. Three out of the 4 probable narcoleptics were confirmed by polysomnography and HLA typing (DRB, 1501 and DQB 0602) leading to a narcolepsy prevalence of 0.021 % in this area.

Narcolepsy was also estimated in the Finnish Twin Cohort (38). A total of 12,504 twins completed the Ullanlinna Narcolepsy Scale. Those suspected of narcolepsy were further interviewed by telephone and then invited to a clinical evaluation, including polygraphic recording and HLA blood typing. Five were strongly suspected of narcolepsy but only three were confirmed by sleep laboratory examination. The prevalence of narcolepsy in the Finnish Twin Cohort was set at 0.026% (95% confidence interval, 0.0-0.06).

Two Chinese studies provided estimates of narcolepsy. The first study, based on patient materials, estimated the frequency of narcolepsy to be between 0.001% and 0.04% in adults (39). The second study (40), performed with 70,000 children and adolescents attending a pediatric neurology clinic, estimated the frequency of narcolepsy at 0.04%. Finally, an American study (41) reviewed all medical records entered between 1960 and 1989 in the records-linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Medical records were classified as “Definite Narcolepsy,” “Probable Narcolepsy (laboratory confirmation)” or “Probable Narcolepsy (clinical).” Prevalence of narcolepsy (with or without cataplexy), extrapolated to the 1985 Olmsted County population, was set at 0.056% and prevalence of narcolepsy with cataplexy was set at 0.035%. The incidence of narcolepsy was set at 1.37/100,000 per year (1.72 for men, 1.05 for women).

3.3.2 Prevalence in the general population

Three studies were performed using representative general community samples. The oldest study was performed in South Arabia (42). Nearly all inhabitants, aged 1 year or older, of the Thugbah community were interviewed. A total of 23,227 individuals participated in face-to-face interviews. A neurologist subsequently evaluated all participants with abnormal responses in the questionnaire. Narcolepsy was found in 0.04% of the sample (95% confidence interval, 0.014% to 0.066%).

A study (1) was conducted with representative samples of five European countries (the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Portugal and Spain). A total of 18,980 individuals, aged 15 years and over, were interviewed by telephone. Using the minimal criteria proposed by the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD), researchers found a prevalence of narcolepsy of 0.047% (95% confidence interval, 0.016% to 0.078%).

Finally, Wing et al. (43) conducted a telephone study using a general population sample of 9,851 adults aged between 18 and 65 years. Participants answered a validated Chinese version of the Ullanlinna Narcolepsy Scale. Subjects with positive scores on the Ullanlinna Narcolepsy Scale (n=28) were invited to a clinical interview and further testing (polysomnography, MSLT and HLA typing). Three subjects refused supplemental evaluation. Three subjects were identified as narcoleptics. This set the prevalence of narcolepsy at 0.034% (95% CI: 0.021%-0.154%) in Hong Kong.

Limitations from existing classifications pose serious difficulties in studying narcolepsy in the general population. The use of too large criteria inflates the prevalence. For example, narcolepsy symptoms, automatic behavior, sleep paralysis and hypnagogic hallucinations are too poorly defined to be useful in epidemiology. Recurrent intrusions of elements of REM sleep into the transition between sleep and wakefulness are highly prevalent in the general population: 6.2% for sleep paralysis and 24.1% for hypnagogic hallucinations (1). This indicates that these symptoms are not specific to narcolepsy.

Practice point 2.

Insufficient sleep syndrome was rarely investigated as a diagnostic entity but mostly as a symptom.

Insufficient sleep was strongly associated with excessive sleepiness. However, attempts to identify possible diagnoses (for example, insomnia, OSAS or depression) were rarely made.

The prevalence of hypersomnia diagnoses is still to be determined in the general population. The few data available suggest that hypersomnia as a diagnosis is below 1%.

The prevalence of narcolepsy is set at 0.04% in the general population. Milder forms are yet to be documented.

3.3.3 Genetic epidemiology of narcolepsy

The genetic component of narcolepsy has been known for several decades. The first description of familial narcolepsy, mother and son, was made in 1877 (44). Another early case report by Daly and Yoss (45) presented a three-generation family with 12 definite and 3 possible cases of narcolepsy (only 3 had cataplexy). More systematic research on familial aspects of narcolepsy appeared in the 1970s. Three methods were used to collect information on family members.

The first method was based on the collection of family history of excessive sleepiness and narcolepsy with the probands without further verification with the family. The first genetic epidemiology research mostly used this method. A study with 50 narcoleptic probands reported that 18% of them (n=9) had at least another family member with narcolepsy and 34% of probands had at least one other family member with excessive daytime sleepiness (46). Honda et al. (47) reported a proportion of 6% of narcoleptic family members and 24% with excessive daytime sleepiness. In another study, family history reports identified 23% of narcoleptic probands with at least another family member with narcolepsy and 44% with at least one relative with excessive daytime sleepiness (48).

The second method consisted of asking to probands with narcolepsy if they had any “sleepy” first- or second-degree relatives. In some studies, the probands also had to answer questions about other narcolepsy symptoms for each sleepy relative. Based on the description made by the probands, relatives suspected of narcolepsy were invited for an interview and examination at the sleep clinics (49-52). The proportion of probands with at least one family member with narcolepsy ranged from 1.5% to 9.8% (see Table 5). Asking probands if family members had narcolepsy-cataplexy led to the lowest rate of affected family members (1.5%).

Table 5.

Genetic epidemiological studies on narcolepsy

| Authors | Place | N screened probands | N family | Methods | % probandsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guilleminault et al., 1989 (49) | USA | 334 | 35 | 1) Screening with the probands of narcolepsy symptoms in the family; 2) interviews with first- or second-degree relatives with excessive sleepiness + cataplexy | 5.7 |

| Billard et al., 1994 (50) | France | 188 | 37 | 1) Screening with the probands of narcolepsy symptoms in the family; 2) interviews with first- or second-degree relatives with excessive sleepiness + cataplexy | 7.4 |

| Nevsimalova et al., 1997 (51) | Czech Republic | 153 | 1082 | 1) Screening with the probands for excessive sleepiness in family members; 2) questionnaires sent to all family members of probands who reported at least 1 sleepy family member; 3) interviews with first- or second-degree relatives with excessive sleepiness + cataplexy; clinical examination for 11/22 positive family members | 9.8 |

| Hayduk et al., 1997 (53) | USA | 32 | 57 | No screening with the probands. Living first-degree relatives underwent polysomnography, MSLT and HLA | 18.8 |

| Mayer et al., 1998 (52) | Germany | 711 | 47 | 1) Screening with the probands for narcolepsy-cataplexy symptoms in first and second-degree relatives; 2) polysomnography and MSLT for 24 family members | 1.5 |

| Ohayon et al., 2005 (27) | Italy | 157 | 263 | No screening with the probands. Living first-degree relatives underwent interviews | 10.8 |

| Ohayon et al., 2006 (54) | USA | 96 | 337 | No screening with the probands. Living first-degree relatives underwent interviews | 20.8 |

Proportion of probands with at least one positive family member

The third method consisted of collecting genealogic information with the proband and interviewing all available living first- (and second-) degree relatives (27,53,54). This second method was more time consuming and more expensive. However, it led to higher proportions (10.8% to 20.8%) of narcoleptic probands with at least one family member with narcolepsy (Table 5).

Relying on the memory and the knowledge of probands about their family members is more likely to provide inaccurate estimates of prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness and narcolepsy among the family members.

Practice point 3.

Genetic epidemiological studies of narcolepsy have shown that between 1.5% and 20.8% of narcoleptic individuals have at least one family member with the disease.

The different methods used to collect the information on the family members were mostly responsible for this large variation is mostly.

The method consisting in the systematic investigation of all family members provided higher results.

4 CONCLUSIONS

A uniform operational definition of excessive sleepiness is still missing; few surveys have used similar definitions. Consequently, the variance in results does not make it possible to reach any definite conclusions. A clear definition of what is excessive sleepiness and what are the “markers” that most alert physicians are essential to advance our knowledge; otherwise, excessive sleepiness will remain the “second” symptom, unworthy of medical attention.

There is no distinction between excessive sleepiness and fatigue: we still do not know how we can differentiate excessive sleepiness from fatigue; to what extent these two concepts overlap; and if excessive sleepiness is always a cause of fatigue or if excessive sleepiness can occur without fatigue.

The causes and consequences of excessive sleepiness are rarely presented as a whole.

Hypersomnia is an associated symptom in depressive disorders in the DSM-IV classification. However, no epidemiological study has investigated such a relationship, although mental disorders are present in about 10% of sleepy individuals who consult sleep disorders clinics and about 10% to 75% of depressed patients complain of hypersomnia. Few polysomnographic studies have been performed with patients having a mood disorder in relationship to hypersomnia or excessive sleepiness. The Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) did not reveal abnormalities in the daytime sleep latency (55). Several clinical studies have also pointed out the high occurrence of subjective excessive sleepiness in association with mental disorders, organic disorders or both. This high comorbidity may hide a more complex problem based on the definition of excessive sleepiness.

Few of the epidemiological studies have reported results by ethnic group or indicated the ethnic makeup of their sample. In fact, there have been almost no data published on ethnocultural differences in excessive sleepiness in the United States or elsewhere (19). Some investigators have interpreted data from the Human Relations Area Files as indicating that certain aspects of sleep, such as daytime napping, may occur more in some cultural groups (56), but epidemiologic data on such cross-cultural differences actually are quite rare. A recent study of college students in Mexico City found no support for the “siesta culture” concept, characterized by a strong tendency for daytime naps and daytime sleepiness (57). More similarities than differences were noted between the sample from Mexico and samples from other countries on sleep patterns.

Genetic epidemiology in sleep disorders is still in its infancy. Only seven genetic epidemiological studies have been done for narcolepsy and none on hypersomnia disorder diagnosis. Again, the disparity between how the family members were assessed led to considerable divergence in the prevalence of narcolepsy among family members. The systematic investigation of all family members provided higher results.

Research agenda

In the coming years, epidemiological research efforts should focus on the following:

-

(1)

Sandardization of the definitions of hypersomnia, sleep excess and excessive sleepiness.

-

(2)

Definition of rules on how to assess sleep excess and excessive sleepiness.

-

(3)

Longitudinal epidemiological data on the evolution and consequences of excessive sleepiness need to be gathered.

-

(4)

Standard procedures for genetic sleep epidemiology need to be developed.

Table 4.

Prevalence of narcolepsy

| Authors | 5.1.1.1 Place | N | Age range | Population and Methods | Prevalence Per 100,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solomon, 1945 (28) | USA | 10,000 | 16-34 | Black naval recruit men | 20 |

| Dement et al., 1972 (28) | North California USA | Unknown | Unknown | General population recruited by newspaper advertisement followed by telephone interview | 50† |

| Dement et al., 1973 (31) | South California USA | Unknown | Unknown | General population recruited by TV advertisement followed by telephone interview | 67† |

| Honda, 1979 (32) | Fujisawa City, Japan | 12,469 | 12-16 | High school students, questionnaire | 160 |

| Roth, 1980 (29) | Czech Caucasians | Unknown | Unknown | Patient material, polysomnography | 20 to 30† |

| Franceschi et al., 1982 (34) | Milan, Italy | 2,518 | 6-92 | Unselected in-patients, questionnaire, polysomnography | 40† |

| Lavie & Peled, 1987 (35) | Israeli Jews and Arabs | 1,526 | 30-57 | Patient material, polysomnography and HLA typing | 0.23† |

| al Rajeh et al., 1993 (42) | Thugbah community, South Arabia | 23,227 | >=1 | All the population. Face-to-face interviews, subjects with abnormal responses evaluated by a neurologist | 40 |

| Hublin et al., 1994 (38) | Finland | 12,504 | 33-60 | Twin cohort, postal questionnaire, telephone interview, polysomnography, HLA typing | 26 |

| Tashiro et al., 1994 (32) | Japan | 4,559 | 17-59 | Sample of employees, questionnaire, personal interview | 180 |

| Wing et al.,1994 (39) | Hong Kong, China | 342 | >=18 | Patient material from 1986 to 1992, polysomnography, MSLT and HLA typing | 1 to 40† |

| Billiard et al., 1987 (36) | Vincennes and Tarascon, France | 58,162 | 17-22 | Male military recruits, questionnaire | 55 |

| Ondzé et al., 1998 (37) | “Le Gard” region, France | 14,195 | > 15 | Patients of all physicians. Questionnaire + follow up by phone interview for possible cases + polysomnography and HLA typing in 4 cases | 21 |

| Han et al., 2001 (40) | Beijing, China | 70,000 | 5-17 | Consecutive patients attending a pediatric neurology clinic. Screening questionnaire + polysomnography, MSLT and HLA typing | 40 |

| Ohayon et al., 2002 (1) | UK, Germany, Italy, Portugal and Spain | 18,980 | 15-100 | Representative sample of general population. Telephone interview with Sleep-EVAL system | 47 |

| Silber et al., 2002 (41) | Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA | Unknown | 0-109 | Review of medical records between 1960 and 1985 | 57† |

| Wing et al., 2002 (43) | Hong Kong, China | 9,851 | 18-65 | Representative sample of general population. Ullanlinna narcolepsy scale, polysomnography, MSLT and HLA | 34 |

Prevalence was extrapolated

Acknowledgments

MMO is supported by a NIH grant (#5R01NS044199).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1*.Ohayon MM, Priest RG, Zulley J, Smirne S, Paiva T. Prevalence of narcolepsy symptomatology and diagnosis in the European general population. Neurology. 2002;58:1826–1833. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lugaresi E, Cirignotta F, Zucconi M, Mondini S, Lenzi PL, Coccagna G. Good and poor sleepers: an epidemiological survey of the San Marino population. In: Guilleminault C, Lugaresi E, editors. Sleep/Wake disorders: Natural History, Epidemiology, and Long-Term Evolution. New-York, NY: Raven Press; 1983. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klink M, Quan SF. Prevalence of reported sleep disturbances in a general adult population and their relationship to obstructive airways diseases. Chest. 1987;91:540–546. doi: 10.1378/chest.91.4.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enright PL, Newman AB, Wahl PW, Manolio TA, Haponik EF, Boyle PJR. Prevalence and correlates of snoring and observed apneas in 5,201 older adults. Sleep. 1996;19:531–538. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.7.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitney CW, Enright PL, Newman AB, Bonekat W, Foley D, Quan SF. Correlates of daytime sleepiness in 4578 elderly persons: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Sleep. 1998;21:27–36. doi: 10.1093/sleep/21.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foley D, Monjan A, Masaki K, Ross W, Havlik R, White L, Launer L. Daytime sleepiness is associated with 3-year incident dementia and cognitive decline in older Japanese-American men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1628–1632. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.t01-1-49271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rockwood K, Davis HS, Merry HR, MacKnight C, McDowell I. Sleep disturbances and mortality: results from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:639–641. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Téllez-Lòpez A, Sánchez EG, Torres FG, Ramirez PN, Olivares VS. Hábitos y trastornos del dormir en residentes del área metropolitana de Monterrey. Salud Mental. 1995;18:14–22. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaneita Y, Ohida T, Uchiyama M, Takemura S, Kawahara K, Yokoyama E, Miyake T, Harano S, Suzuki K, Yagi Y, Kaneko A, Tsutsui T, Akashiba T. Excessive daytime sleepiness among the Japanese general population. J Epidemiol. 2005;15:1–8. doi: 10.2188/jea.15.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10*.Liljenberg B, Almqvist M, Hetta J, Roos BE, Agren H. The prevalence of insomnia: the importance of operationally defined criteria. Ann Clin Res. 1988;20:393–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zielinski J, Zgierska A, Polakowska M, Finn L, Kurjata P, Kupsc W, Young T. Snoring and excessive daytime somnolence among Polish middle-aged adults. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:946–950. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d36.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Uchiyama M, Kim K, Okawa M, Shibui K, Kudo Y, Doi Y, Minowa M, Ogihara R. Sleep loss and daytime sleepiness in the general adult population of Japan. Psychiatry Res. 2000;93:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martikainen K, Hasan J, Urponen H, Vuori I, Partinen M. Daytime sleepiness: A risk factor in community life. Acta Neurol Scand. 1992;86:337–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1992.tb05097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janson C, Gislason T, De Backer W, Plaschke P, Bjornsson E, Hetta J, Kristbjarnason H, Vermeire P, Boman G. Daytime sleepiness, snoring and gastro-oesophageal reflux amongst young adults in three European countries. J Intern Med. 1995;237:277–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1995.tb01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hublin C, Kaprio J, Partinen M, Heikkila K, Koskenvuo M. Daytime sleepiness in an adult Finnish population. J Intern Med. 1996;239:417–423. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1996.475826000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hara C, Lopes Rocha F, Lima-Costa MF. Prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness and associated factors in a Brazilian community: the Bambui study. Sleep Med. 2004;5:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gislason T, Almqvist M, Erikson G, Taube A, Boman G. Prevalence of sleep apnea syndrome among Swedish men - an epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:571–576. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Philip P, Guilleminault C, Priest R. How sleep and mental disorders are related to complaints of daytime sleepiness. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2645–2652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nugent AM, Gleadhill I, McCrum E, Patterson CC, Evans A, MacMahon J. Sleep complaints and risk factors for excessive daytime sleepiness in adult males in Northern Ireland. J Sleep Res. 2001;10:69–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohayon MM, Vechierrini MF. Daytime sleepiness is an independent predictive factor for cognitive impairment in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:201–208. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, Calhoun SL, Vela-Bueno A, Kales A. Excessive daytime sleepiness in a general population sample: the role of sleep apnea, age, obesity, diabetes, and depression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4510–4515. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Souza JC, Magna LA, Reimao R. Excessive daytime sleepiness in Campo Grande general population, Brazil. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2002;60:558–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takegami M, Sokejima S, Yamazaki S, Nakayama T, Fukuhara S. An estimation of the prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness based on age and sex distribution of Epworth sleepiness scale scores: a population based survey. Nippon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2005;52:137–145. In Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24*.Baldwin CM, Kapur VK, Holberg CJ, Rosen C, Nieto FJ. Sleep Heart Health Study Group. Associations between gender and measures of daytime somnolence in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2004;27:305–311. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Hublin C, Kaprio J, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M, Heikkila K, Koskimies S, Guilleminault C. The prevalence of narcolepsy: an epidemiological study of the Finnish Twin Cohort. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:709–716. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989;262:1479–1484. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.11.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27*.Ohayon MM, Ferini-Strambi L, Plazzi G, Smirne S, Castronovo V. Frequency of narcolepsy symptoms and other sleep disorders in narcoleptic patients and their first-degree relatives. J Sleep Res. 2005;14:437–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solomon P. Narcolepsy in negroes. Dis Nerv Syst. 1945;6:176–183. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roth B. In: Narcolepsy and Hypersomnia. Broughton R, translator. Chapter 10. London: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dement W, Zarcone W, Varner V, Faines CS. The prevalence of narcolepsy. Sleep Res. 1972;1:148. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dement WC, Carskadon M, Ley R. The prevalence of narcolepsy II. Sleep Res. 1973;2:147. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Honda Y. Census of narcolepsy, cataplexy and sleep life among teenagers in Fujisawa city. Sleep Res. 1979;8:191. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tashiro T, Kanbayashi T, Iijima S, Hishikawa Y. An epidemiological study on prevalence of narcolepsy in Japanese. J Sleep Res. 1992;1(suppl):228. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franceschi M, Zamproni P, Crippa D, Smirne S. Excessive daytime sleepiness: a 1-year study in an unselected inpatient population. Sleep. 1982;5:239–247. doi: 10.1093/sleep/5.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lavie P, Peled R. Letter to the Editor: Narcolepsy is a Rare Disease in Israel. Sleep. 1987;10:608–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Billiard M, Alperovich A, Perot C, Jammes C. Excessive daytime sleepiness in young men: prevalence and contributing factors. Sleep. 1987;10:297–305. doi: 10.1093/sleep/10.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ondzé B, Lubin S, Lavendier B, Kohler F, Mayeux D, Billiard M. Frequency of narcolepsy in the population of a French “département”. J Sleep Res. 1998;7:193. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hublin C, Kaprio J, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M. Insufficient sleep--a population-based study in adults. Sleep. 2001;24:392–400. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wing YK, Chiu HF, Ho CK, Chen CN. Narcolepsy in Hong Kong Chinese--a preliminary experience. Aust N Z J Med. 1994;24:304–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1994.tb02177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han F, Chen E, Wei H, Dong X, He Q, Ding D, Strohl KP. Childhood narcolepsy in North China. Sleep. 2001;24:321–324. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silber MH, Krahn LE, Olson EJ, Pankratz VS. The epidemiology of narcolepsy in Olmsted County, Minnesota: a population-based study. Sleep. 2002;25:197–202. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.al Rajeh S, Bademosi O, Ismail H, Awada A, Dawodu A, al-Freihi H, Assuhaimi S, Borollosi M, al-Shammasi S. A community survey of neurological disorders in Saudi Arabia: the Thugbah study. Neuroepidemiology. 1993;12(3):164–178. doi: 10.1159/000110316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wing YK, Li RH, Lam CW, Ho CK, Fong SY, Leung T. The prevalence of narcolepsy among Chinese in Hong Kong. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:578–584. doi: 10.1002/ana.10162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westphal CC. Eigenthumliche mit Einschafen verbundene Anfalle. Arch Psychiat Nervenkr. 1877;7:681–683. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daly DD, Yoss RE. A family with narcolepsy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1959;34:313–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kessler S, Guilleminault C, Dement W. A family study of 50 REM narcoleptics. Acta Neurol Scand. 1974;50:503–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1974.tb02796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Honda Y, Asaka A, Tanaka Y, Juji T. Discrimination of narcoleptic patients by using genetic markers and HLA. Sleep Res. 1983;12:254. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montplaisir J, Poirier G. HLA in narcolepsy in Canada. In: Honda Y, Juji T, editors. HLA in Narcolepsy. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1988. pp. 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guilleminault C, Mignot E, Grumet FC. Familial patterns of narcolepsy. Lancet. 1989;2(8676):1376–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91977-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Billiard M, Pasquie-Magnetto V, Heckman M, Carlander B, Besset A, Zachariev Z, Eliaou JF, Malafosse A. Family studies in narcolepsy. Sleep. 1994;17(8 Suppl):S54–S59. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.suppl_8.s54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nevsimalova S, Mignot E, Sonka K, Arrigoni JL. Familial aspects of narcolepsy-cataplexy in the Czech Republic. Sleep. 1997;20:1021–1026. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.11.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mayer G, Lattermann A, Mueller-Eckhardt G, Svanborg E, Meier-Ewert K. Segregation of HLA genes in multicase narcolepsy families. J Sleep Res. 1998;7:127–133. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1998.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayduk R, Flodman P, Spence MA, Erman MK, Mitler MM. HLA haplotypes, polysomnography, and pedigrees in a case series of patients with narcolepsy. Sleep. 1997;20:850–857. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.10.850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54*.Ohayon MM, Okun ML. Occurrence of sleep disorders in the families of narcoleptic patients. Neurology. 2006;67:703–705. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000229930.68094.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Webb WB, Dinges DF. Cultural perspectives on napping and the siesta. In: Dinges DF, Broughton RJ, editors. Sleep and alertness: Chronobiological behavioral and medical aspects of napping. New York: Raven Press; 1989. pp. 247–265. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valencia-Flores M, Castano VA, Campos RM, Rosenthal L, Resendiz M, Vergara P, Aguilar-Roblero R, Garcia Ramos G, Bliwise DL. The siesta culture concept is not supported by the sleep habits of urban Mexican students. J Sleep Res. 1998;7:21–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1998.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bixler EO, Kales A, Soldatos CR, Kales JD, Healey S. Prevalence of sleep disorders in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136:1257–1262. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.10.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nofzinger EA, Thase ME, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Himmelhoch JM, Mallinger A, Houck P, Kupfer DJ. Hypersomnia in bipolar depression: a comparison with narcolepsy using the multiple sleep latency test. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1177–1181. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.9.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:411–418. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roberts RE, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Prospective data on sleep complaints and associated risk factors in an older cohort. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:188–196. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199903000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klink M, Quan SF. Prevalence of reported sleep disturbances in a general adult population and their relationship to obstructive airways diseases. Chest. 1987;91:540–546. doi: 10.1378/chest.91.4.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hays JC, Blazer DG, Foley DJ. Risk of napping: Excessive daytime sleepiness and mortality in an older community population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:693–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Asplund R. Daytime sleepiness and napping amongst the elderly in relation to somatic health and medical treatment. J Intern Med. 1996;239:261–267. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1996.453806000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]