Summary

Eukaryotes are endowed with multiple specialized DNA polymerases, some (if not all) of which are believed to play important roles in the tolerance of base damage during DNA replication. Among these DNA polymerases, Rev1 protein (a deoxycytidyl transferase) from vertebrates interacts with several other specialized polymerases via a highly conserved C-terminal region. The present studies assessed whether these interactions are retained in more experimentally tractable model systems, including yeasts, flies, and the nematode C. elegans. We observed a physical interaction between Rev1 protein and other Y-family polymerases in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. However, despite the fact that the C-terminal region of Drosophila and yeast Rev1 are conserved from vertebrates to a similar extent, such interactions were not observed in S. cerevisiae or S. pombe. With respect to regions in specialized DNA polymerases that are required for interaction with Rev1, we find predicted disorder to be an underlying structural commonality. The results of this study suggest that special consideration should be exercised when making mechanistic extrapolations regarding translesion DNA synthesis from one eukaryotic system to another.

Keywords: Y-family of DNA polymerases, TLS, Rev1, polymerase η, polymerase ι, polymerase κ, protein-protein interactions

1. Introduction

The rescue of arrested DNA replication at sites of template base damage is critical for cell survival. Not surprisingly, prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells have evolved multiple strategies for mitigating the lethal effects of arrested DNA replication without prior removal of the offending DNA damage; so-called DNA damage tolerance [1]. The replicative bypass of base damage by DNA translesion synthesis (TLS) represents a specific mode of damage tolerance that utilizes specialized low-fidelity DNA polymerases to overcome arrested DNA replication, often at the expense of introducing errors and hence generating mutations [1]. To date ten such specialized DNA polymerases have been identified in vertebrates. A newly-discovered subset of these proteins (Rev1, Polη, Polι, and Polκ) is designated the Y-family of DNA polymerases [1–3].

Among the Y-family of DNA polymerases Rev1 protein is highly conserved in eukaryotes, but no archaeal or bacterial Rev1 orthologs have been detected. Structural orthologs of Polη and Polι are also apparently absent in prokaryotes. In contrast, a readily identifiable ortholog of Polκ (DinB protein in E. coli) is present in bacteria. Rev1 is unique among the Y-family in that its DNA polymerase activity is restricted to the incorporation of one or two molecules of dCMP regardless of the nature of the template nucleotide. It is thus often referred to as a dCMP transferase [4]. Remarkably, while the catalytic domain of Rev1 protein is required for the replicative bypass of sites of base loss (AP sites), inactivation of this activity does not abrogate a requirement for Rev1 for ultraviolet (UV) radiation-induced mutagenesis in yeast or mammalian cells [5–7].

Rev1 protein also possesses a conserved N-terminal BRCT domain that is required for TLS in yeast and mammalian cells exposed to UV radiation [7,8] and presumably other types of base damage. Indeed, a single amino acid substitution in the BRCT domain of otherwise catalytically active yeast Rev1 abolishes the bypass of [6–4] photoproducts, suggesting a non-catalytic role(s) for Rev1 protein during UV radiation-induced mutagenesis [7]. Additional support for the notion that Rev1 has a function(s) in TLS that is independent of its dCMP transferase activity is implicit in the observation that the protein interacts with the Y-family polymerases Polκ, Polη and Polι, and with Rev7 protein [a subunit of a heterodimeric specialized DNA polymerase called Polζ] through a C-terminal 100 amino acid region that is highly conserved among vertebrates [9–11]. The functional significance of these interactions is not understood. However, the additional observations that PCNA also interacts with these DNA polymerases and with Rev1 protein [8,12–14], and that PCNA and some Y-family members (including Rev1 protein) undergo monoubiquitination, has prompted the hypothesis that Rev1 plays a key role in the process of TLS [3,15,16].

Several non-vertebrate eukaryotic organisms, such as the yeasts S. cerevisiae and S. pombe, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, and the nematode C. elegans, have proven to be informative model systems for various mechanistic studies in vertebrates. In view of the fact that these model organisms are endowed with Rev1 protein as well as one or more other Y-family DNA polymerases, they offer the potential for gaining fundamental insights into the molecular biology of TLS in eukaryotes. In the present studies we have compared interactions between Rev1 protein and other members of the Y-family of DNA polymerases from animals and fungi.

Here we report that Rev1 protein from the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster and the yeasts S. cerevisiae and S. pombe readily interacts with the Rev7 subunit of the specialized DNA polymerase ζ (Polζ). Additionally, various Y-family DNA polymerases from Drosophila interact with Rev1 protein from this organism. In contrast, members of the Y-family of specialized DNA polymerases from both yeasts and from C. elegans do not interact with Rev1 protein from these organisms. Consistent with this observation, the extensive conservation of the C-terminal 100 amino acids of Rev1 protein in vertebrates is not observed in yeasts or nematodes. Remarkably, however, the extent of amino acid conservation in the C-terminal region of Rev1 protein from Drosophila is not obviously greater than that observed in yeast.

In contrast to the corresponding mouse proteins, the Drosophila Y-family DNA polymerases Polι and Polη utilize two distinct regions to interact with Drosophila Rev1. However, a comparison of the Rev1-interacting domains in Polη, Polι and Polκ from mouse or Drosophila reveals little sequence conservation and does not predict conserved structures. Thus, notwithstanding the presence of Rev1 protein and some specialized DNA polymerases in invertebrates and fungi, interactions between these proteins differ qualitatively among themselves and from the Rev1-DNA polymerase interactions observed in vertebrates. We conclude that no single eukaryotic model system thus far examined can be considered a prototypic model system for generalizing the molecular mechanism of TLS in eukaryotes, and suggest that care must be exercised in making mechanistic extrapolations from one eukaryotic system to another.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pair-wise yeast two-hybrid assays and interaction domain mapping

S. cerevisiae constructs

Rev1 was PCR amplified from Rev1p-GST-pJN60 [17] and cloned into pACT2 (Clontech) or pGBKT7 (Clontech). Rad30 was PCR amplified from pEGUh6b-Rad30 [18] and cloned into pGBKT7 or pGBT9 (Clontech). Rev7 was PCR amplified by colony PCR and cloned into pGADT7 (Clontech).

C. elegans constructs

Rev-1 was amplified by RT-PCR of total RNA (prepared by bead disruption and RNAeasy prep of N2 hermaphrodite worms) and cloned into pGADT7. Polη-1 was amplified by RT-PCR and cloned into pGBKT7. Two spliced products were detected, one with a 57 bp deletion in exon 7, as previously reported [19]. Both products were assayed. Polη-1 was amplified by RT-PCR and cloned into pGBKT7.

S. pombe constructs

Rev1 (SPBC1347.01c) was amplified by RT-PCR of total RNA and cloned into pGADT7 or pGBKT7. Eso1+(Polη), Polκ(SPCC553.07c), and Rev7 were amplified by RT-PCR and cloned into pGBKT7 or pGADT7. Exon boundaries for Rev7 were redefined and annotated accordingly on online databases.

Drosophila constructs

Rev1 was amplified by RT-PCR of total RNA prepared by Trizol extraction of Kc cells and cloned into pACT2. Polη and Polι were amplified from pGEX-dPolι and pGEX-dPolι [20] and cloned into pGBKT7. Rev7 was amplified by RT-PCR and cloned into pGBKT7. Truncation constructs were made by PCR cloning.

Mouse constructs

As previously described [9]. Truncation constructs were made by PCR cloning.

All constructs were sequenced prior to experiments using an automated ABI Prism 3100 Genetic Analyzer.

2.2. Yeast transformation and growth selection

Pair-wise combinations of yeast two hybrid constructs and corresponding negative controls containing an empty vector were transformed into freshly prepared AH109 competent cells (Clontech) and plated on DDO media (-Trp/-Leu). After 4 days of growth at 30°C, 2–3 colonies were picked, suspended in sterile water, and plated on QDO media (-Trp/-Leu/-Ade/-His) and grown for up to 10 days at 30°C to select for positive interactions. Side by side plating on DDO was performed as a control.

2.3. β-galactosidase assays

Pair-wise combinations of full-length or truncated yeast two-hybrid constructs and corresponding negative controls containing an empty vector were transformed into freshly prepared Y187 competent cells (Clontech) and plated on DDO media (-Trp/-Leu) to grow for 3–4 days at 30°C. Two or three colonies were picked and grown in selective media overnight and log-phase cultures were grown to OD600~0.6 the following day. Three aliquots per culture in Z-buffer were flash frozen. Each sample was subjected to the addition of Z-buffer+β-mercaptoethanol and ONPG substrate (Sigma) and subsequently measured (<24 hours) for their spectrophotometric values with respect to time.

2.4. Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis of dRev1 and dPolη

The full-length ORFs for dRev1 and dPolη were cloned into expression vectors using the Drosophila Gateway system. Kc Drosophila cells (40–80% confluency) were co-transfected with dRev1-pAMW(N-terminal Myc) and dPolη-pAWV(C-terminal YFP) or empty pAMW with dPolη-pAWV using Effectene reagent (Quiagen). Transfected cells selected in puromycin (20mg/mL)/CCM-3 reached confluency and were split after 24 hours. Transiently transfected cells were harvested after 48 hours and extracted in lysis buffer (50mM Tris pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40) spiked with protease inhibitor (Sigma). The lysate was incubated with rabbit anti-GFP serum (Molecular Probes) and added to washed Protein A Sepharose (Amersham), followed by incubation for 3h at 4°C. The beads were washed and the contents bound to the beads were analyzed by Western blot using anti-Myc or anti-GFP.

2.4. Yeast strains

Strains are listed in Table 1. Yeast strains used for the Rev1/Rad30 coIP are derivatives of W1588-4C (MATa leu2-3,112 ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 ura3-1 trp1-1 RAD5), which is a W303 strain corrected for RAD5 [21]. Deletion of REV1 and RAD30 were constructed by gene replacement by PCR amplification of rev1::KanMX and rad30::KanMX, respectively, from the Saccharomyces Genome Deletion Project strains 1643 and 4255, respectively. To produce the tagged Rad30 fusion protein, the TEV-ProA-7His tag was PCR amplified from pYM10 [22] and inserted to replace the stop codon of RAD30. Rev1-HA was expressed from pAS311-REV1-HAC, which has been described previously along with YSD5, YLW20 YLW70 [23].

Table 1.

Yeast strains used in this study.

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| W1588-4C | MATa leu2-3,112 ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 ura3-1 trp1-1 RAD5 |

| W1588-4A | MATa leu2-3,112 ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 ura3-1 trp1-1 RAD5 |

| YSD5 |

MATa leu2-3,112 ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 ura3-1 trp1-1 RAD5

bar1::LEU2 REV7-13MYC::HIS3MX6 |

| YLW20 |

MATa leu2-3,112 ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 ura3-1 trp1-1 RAD5

rev1::KanMX |

| YLW70 |

MATa leu2-3,112 ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 ura3-1 trp1-1 RAD5

bar1::LEU2 |

| RWY13 |

MATa leu2-3,112 ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 ura3-1 trp1-1 RAD5

RAD30-TEV-ProA-7His::HIS3MX |

| RWY15 |

MATa leu2-3,112 ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 ura3-1 trp1-1 RAD5

rad30::KanMX |

| RWY254 |

MATa leu2-3,112 ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 ura3-1 trp1-1 RAD5

bar1::LEU2 RAD30-TEV-ProA-His::HISMX |

| RWY270 |

MATa leu2-3,112 ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 ura3-1 trp1-1 RAD5

bar1::LEU2 pep4::KanMX |

2.5. UV radiation survival of yeast

At least three independent cultures of each strain (RWY13, RWY15, and W1588-4C) were used. Cultures were grown to saturation for 3 days at 30°C, diluted in water, plated on SC-H, and immediately irradiated using a G15T8 UV lamp (General Electric) at 254nm, 1 J/m2 per second for varying amounts of time. After irradiation, plates were kept in the dark at 30°C for 3 days before colonies were counted.

2.6. Survival after exposure to methyl methanesulfonate (MMS)

As described previously [23]. In short, after induction in galactose, appropriate dilutions of yeast cells (W1588-4C plus pAS311; YLW20 with pAS311 or with pAS311-REV1-HAC) were plated on SC-W plates with 2% galactose and the indicated amount of MMS.

2.7. Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis of S. cerevisiae Rev1 and Pol η

Yeast cultures were grown in selective media with raffinose for 2 days then subcultured into selective media with galactose to induce protein expression overnight. For UV treatment, cells were spun down and resuspended in water to OD600 ~ 0.5, poured into large dishes to form a thin layer, then exposed to 50 J/m2 of UV (resulting in approximately 50% killing of WT). Irradiated cells were then resuspended in selective media with galactose and incubated at 30°C for 110–120 minutes after irradiation before harvesting, because previous work suggests that both Rev1 and Rad30 respond to DNA damage on this time scale [24–27]. Immunoprecipitations were performed essentially as described previously [23,28]. Cell pellets were washed once in water and resuspended in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM DTT and Roche complete protease inhibitor cocktail). Cells were lysed either by bead-beating or by French Press. The lysate was centrifuged 13,500 RCF for 7 minutes, and PMSF was added to 1 mM. For the precipitation of ProA tagged proteins, the supernatant was bound to 50 μl IgG Sepharose (Amersham) for 1–2 hours. For Myc or HA tags, the supernatant was mixed with 2 μg of anti-Myc (mouse monoclonal 4A6; Upstate) or anti-HA (mouse monoclonal HA.11 clone 16B12; Covance) antibody and incubated for one hour on ice. 20 μl of ProG-agarose (Sigma) was then added and incubated for 1–2 hours at 4°C. The resin was washed 3 times in 500 μl of lysis buffer, and bound proteins were eluted by boiling the resin in SDS sample buffer.

Several alternate coIP procotols were performed, all yielding similar results. One alternate technique is represented in figure 4C. Yeast cultures were grown as above, butresuspended in alternate lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgSO4, 10% glycerol, 0.05%NP40, 1 mM DTT, Roche complete protease inhibitor cocktail). Cell suspension was frozen drop-wise in liquid nitrogen, then lysed by grinding the frozen cells with dry ice in a coffee grinder. Thawed lysates were centrifuged 10,000 RCF for 15 minutes. The supernatant was then incubated with IgG-coupled magnetic beads (Dynabeads M270-Epoxy, Dynal) for 4 hours at 4°C. The beads were collected and washed three times in alternate lysis buffer lacking glycerol. Bound proteins were eluted by boiling the beads in SDS sample buffer.

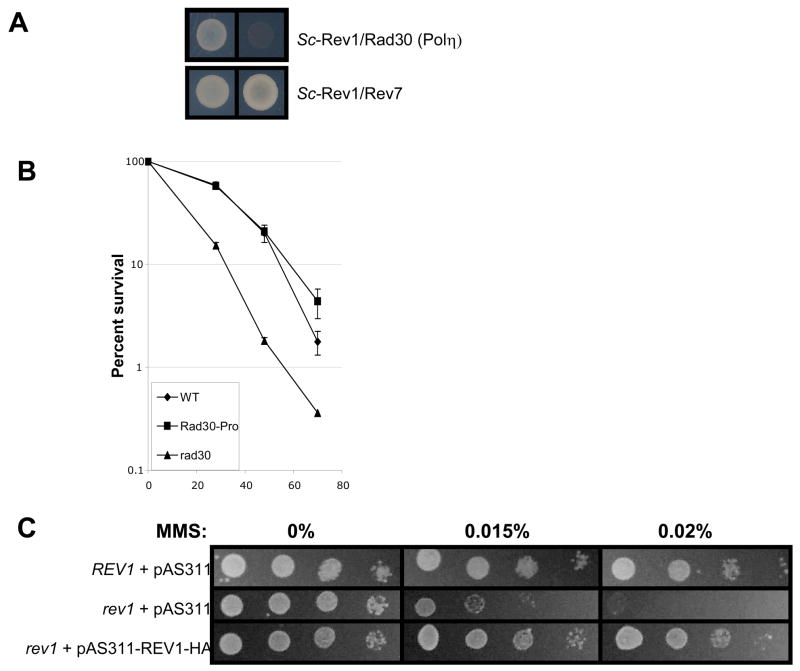

Figure 4. S. cerevisiae Rev1 does not interact with Rad30 (Polη) in vivo.

(A) In the yeast two-hybrid assay, S. cerevisiae Rev1 interacts with Rev7, but not Rad30 (Polη). (B) In S. cerevisiae, tagged Rad30 (Polη) is fully functional for UV radiation survival: comparison of WT (W1588-4C), Rad30-TEV-ProA-His (RWY13), and rad30Δ (RWY15) strains. Error bars represent standard error. (C) Rev1-HA-pAS311 can rescue the MMS sensitivity of the rev1 null mutant. Top row: wildtype (W1588-4A + pAS311), second row: rev1Δ (YLW20 + pAS311) bottom row: Rev1-HA (YLW20 + pAS311-REV1-HAC (D) S. cerevisiae Rev1-HA coimmunoprecipitates endogenously tagged Rev7-Myc. Lane 1: Rev1-Cterm-HA and Rev7-13Myc (YSD5 + pAS311-REV1CT239-HAC); Lane 2: Full length Rev1-HA and Rev7-13Myc (YSD5 + pAS311-Rev1-HAC); Lane 3: Rev7-13Myc alone (YSD5 + pAS311). Full length Rev1 is produced at lower levels than the C-terminal 239 amino acid fragment, resulting in the difference in quantity of Rev7-Myc which coIPs in lane 1 compared with lane 2. (E) In S. cerevisiae, endogenously tagged Rev7 immunoprecipitates Rev1-HA. Rev7-13Myc immunoprecipitates Rev1 in the presence (+) of Rev1-HA (YSD5 + pAS311-Rev1-HAC) but does not in the absence (−) of Rev1-HA (YSD5 + pAS311). Rev1-HA is undetectable in the input (not shown). (F) S. cerevisiae Rev1 and Rad30 (Polη) do not co-immunoprecipitate in the presence or absence of UV-damage. IgG was used to precipitate Rad30-TEV-ProA-7His protein using the alternate coIP protocol with strains RWY75 and YSD7. Lane 1: RWY75 input sample probed with PAP for Rad30-TEV-ProA-7His; Lane 2: RWY75 input; Lane 3, YSD7 IP; Lane4, RWY75 IP, showing Rad30 band only. Lanes 2–4 probed with anti-HA antibody, detects Rev1-HA present in the input and also (through the IgG-binding activity of ProA) nonspecifically detects the high concentration of Rad30-ProA in the IP. For UV-treated conditions, yeast extracts were made from cells that had been subjected to UV radiation. IgG was used to precipitate Rad30-TEV-ProA-7His protein by the primary coIP protocol. Lane 1: Rev1-HA and Rad30-ProA (RWYRWY254 + pAS311-REV1-HAC); Lane 2: Rev1-HA only (RWY270 + pAS311-REV1-HAC); Lane 3: Rad30-ProA only (RWY254).

For immunoblotting, protein samples were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Cambrex), transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore), and probed with appropriate antibodies. ProA-tagged proteins were detected using rabbit peroxidase anti-peroxidase (PAP) antibody (Sigma); Myc and HA tags were detected using mouse monoclonal antibody clone 4A6 (Upstate) and mouse monoclonal HA.11 clone 16B12 (Covance), respectively, followed by HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Pierce).

2.8. Protein sequences analysis

Iterative searches of the non-redundant protein sequence database (National center for Biotechnology Information, NIH, Bethesda) were performed using the PSI-BLAST program [29] with standard parameters and the composition-based statistics applied to eliminate spurious hits emerging as a result of amino acid compositional biases [30]. Multiple alignments of protein sequences were generated using the Clustal W program [31]. Protein secondary structure prediction was performed using the JPred program [32]. Disordered protein regions were predicted using the DisEMBL server [33].

3. Results

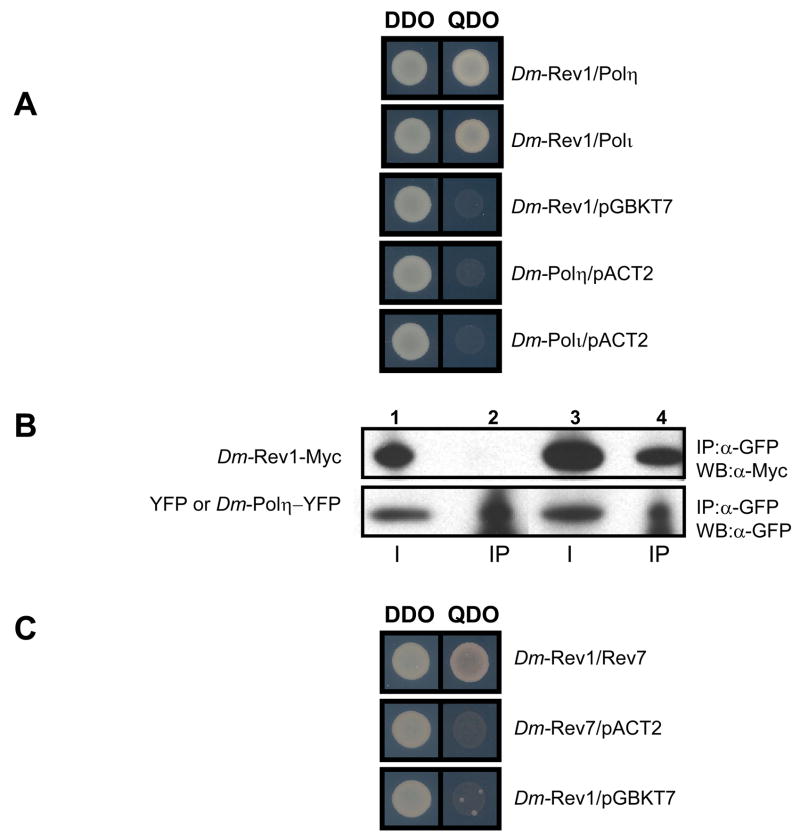

3.1 Interactions between Rev1 protein and Rev7 protein, the catalytic subunit of the B-family DNA polymerase Polζ

In addition to its well-documented ability to interact with various Y-family DNA polymerases, the highly conserved C-terminal region of mouse Rev1 protein interacts with the Rev7 subunit of Polζ, a specialized DNA polymerase from the B-family, which is also implicated in TLS in eukaryotes. Rev1 protein from Drosophila and the yeasts S. pombe and S. cerevisiae also interact with homologous Rev7 protein (Figs. 2–5). Additionally, mouse Rev1 maintains an interaction with Rev7 from both yeasts and flies (data not shown), suggesting that the region of Rev7 responsible for binding Rev1 is structurally conserved.

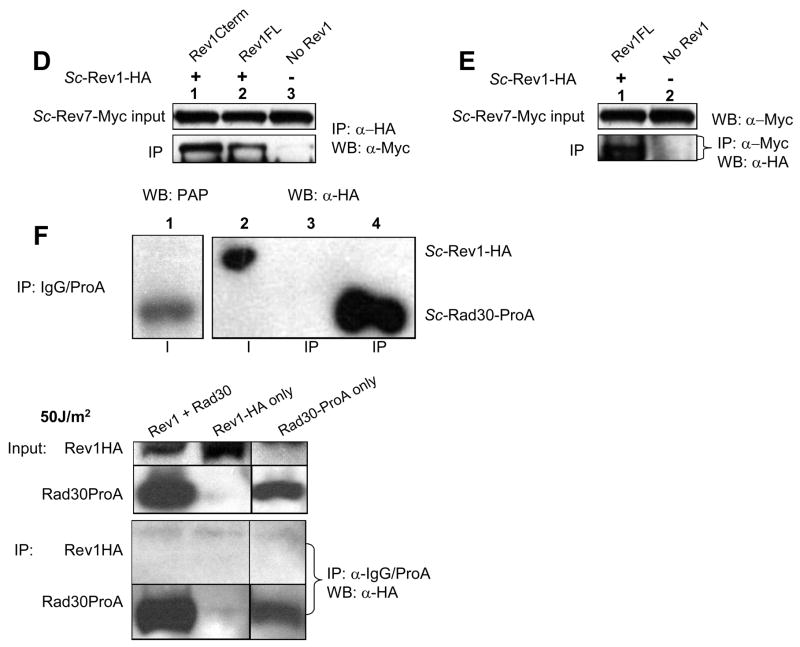

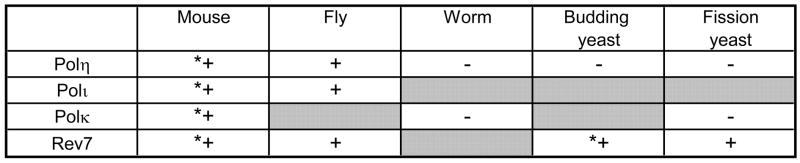

Figure 2. Drosophila Rev1 interacts with Y-family polymerases Polι and Polη, and B-family Rev7 (Polζ).

(A) Drosophila Rev1 interacts with Drosophila Polη and Polι in the yeast two-hybrid assay. Yeast transformants expressing a Drosophila Rev1-activation domain (AD) fusion protein and the designated polymerase (Polι, or Polη)-binding domain (BD) fusion protein are selected on double drop out (DDO) media (-Trp or Leu). Positive interactions are indicated by growth on quadruple drop out (QDO) media acids (-Trp, -Leu, -Ade, -His). Growth on QDO media indicates the two proteins physically interact, as their proximity results in the activation of histidine and adenine protein expression. (B) Drosophila Rev1 co-precipitates with Drosophila Polη; Lane 1: input Rev1-Myc + YFP; Lane 2: IP Rev1-Myc + YFP; Lane 3: input Rev1-Myc + Polη-YFP; Lane 4: IP Rev1-Myc + Polη-YFP. (C) Drosophila Rev1 interacts with Drosophila Rev7 in the yeast two-hybrid assay.

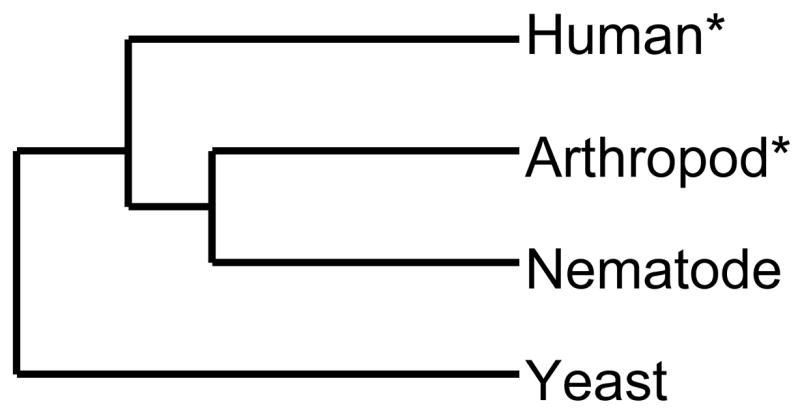

Figure 5. The TLS polymerase interactions with Rev1 protein within different species.

The presence (+) or absence (−) of a DNA polymerase interaction with Rev1 within each species (as determined by the yeast two-hybrid or other methods described here) is indicated. Shaded boxes indicate that the polymerase has not been identified in the species. Asterisks (*) indicate previously published work.

3.2. Interactions between Rev1 protein and Y-family DNA polymerases in animals and yeast

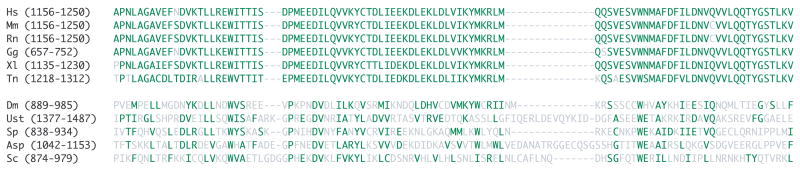

As already mentioned, interactions between Rev1and the Y-family of DNA polymerases from humans and mice transpire via the C-terminal 100 amino acids of Rev1, a region of the protein that is highly conserved in vertebrates (Fig. 1). An iterative search of the NCBI non-redundant protein sequence database demonstrated that this region of Rev1 is also conserved in a number of invertebrates, and fungi also reveal homologous sequences (Fig. 1). However, the extent of the amino acid conservation is considerably reduced compared to that in vertebrates (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the C-terminal 100 amino acids of Rev1 are not conserved in nematodes (data not shown). Exhaustive sequence searches failed to reveal sequences homologous to the Rev1 C-terminus of nematodes in other eukaryotes or in prokaryotes. Thus, it appears that the C-terminal domain of Rev1 is an innovation of the animal-fungal lineage that was lost in nematodes.

Figure 1. The C-terminus of Rev1 is highly conserved in vertebrates but to a lesser extent among invertebrates.

The sequences of the C-terminal 100 amino acids of Rev1 protein in vertebrates (top) and invertebrates and fungi (bottom) are shown. Hs, Homo sapiens; Mm, Mus musculus; Rn, Rattus norvegicus; Gg, Gallus gallus; Xl, Xenopus laevis; Tn Tetraodon nigroviridis; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; Ust, Ustilago maydis; Sp, Schizosaccharomyces pombe; Asp, Aspergillus fumigatus; Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Amino acid identity and similarity are represented by green colored letters, while differences are indicated in grey.

To explore physical interactions between Rev1 and Y-family DNA polymerases from various non-vertebrate eukaryotes, yeast cells were co-transformed with Rev1 and a DNA polymerase of interest, and interactions were examined using the yeast two-hybrid system and in some cases by co-immunoprecipitation. In confirmation of previous studies, mouse Rev1 protein interacted with the mouse Y-family DNA polymerases Polη, Polι and Polκ (data not shown, see Fig. 5) [9]. Similar results were obtained when yeast cells were transformed with vectors that express Rev1 and either Polη or Polι from D. melanogaster (Fig. 2A), an organism not endowed with a Polκ gene. This result was confirmed by immunoprecipitating YFP-tagged Polη from Drosophila cell lysates and detecting Myc-tagged Rev1 on YFP- Polη-bound beads (Fig. 2B).

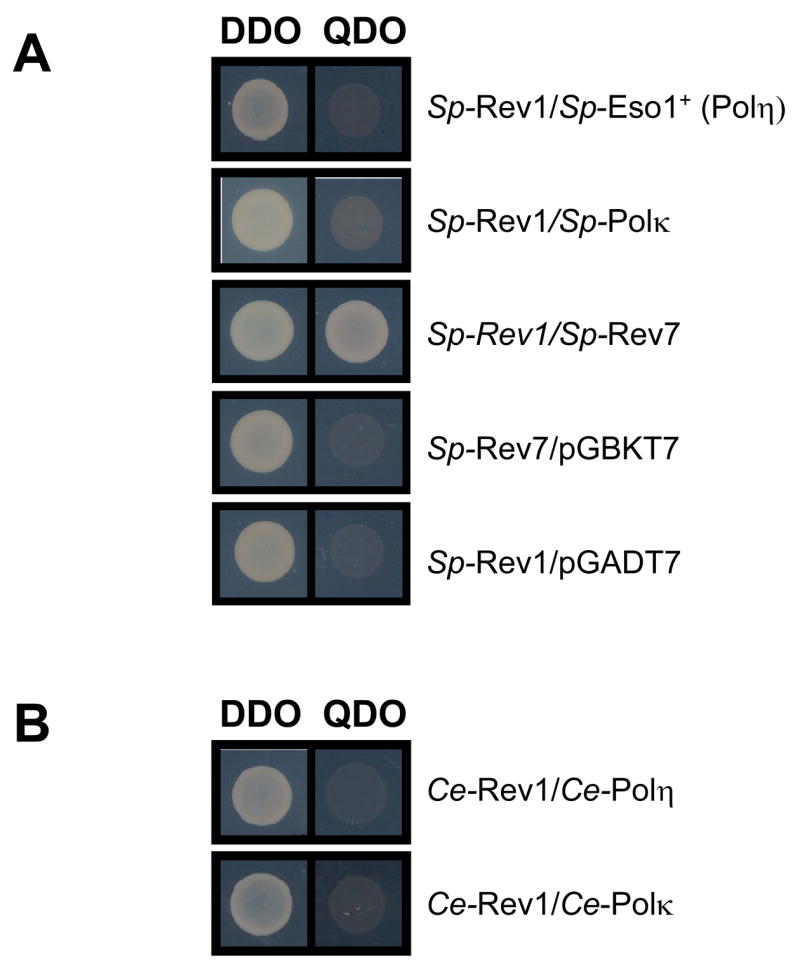

No interactions were observed between Rev1 and Polη (eso1+ or Rad30) from the yeasts S. pombe or S. cerevisiae using the yeast two-hybrid assay (Figs. 3A and 4A). Like Drosophila, the yeast S. cerevisiae does not harbor a Polk gene. However, Rev1 protein from S. pombe failed to interact with Polκ protein from this organism (Figure 3A). Additionally, Rev1 protein from the nematode C. elegans failed to demonstrably interact with either Polη or Polκ from this organism (Figure 3B). In confirmation of these negative results a strain of S. cerevisiae modified to express endogenously tagged Rad30 (Polη)-ProA was transformed with a vector expressing yeast Rev1 protein tagged with an HA epitope. Both tagged proteins were functional as evidenced by their ability to complement the sensitivity of S. cerevisiae rev1Δ and rad30Δ (polη) mutants to killing by UV radiation or methyl methane sulfonate (Fig. 4B and 4C). However, in contrast to the control co-IP observed between S. cerevisiae Rev7-Myc and Rev1-HA (Fig. 4D and 4E), when Rad30 (Polη)-ProA was immunoprecipitated from yeast cell extracts (either in the absence or the presence of DNA damage) Rev1-HA failed to co-precipitate (Fig. 4F).

Figure 3. Rev1 interactions in S. pombe and C. elegans.

In the yeast two-hybrid assay (A) S. pombe Rev1 interacts with S. pombe Rev7, but not S. pombe eso1+(Polη) or Polκ. (B) C. elegans Rev1 does not interact with C. elegans Polη or Polκ homologs.

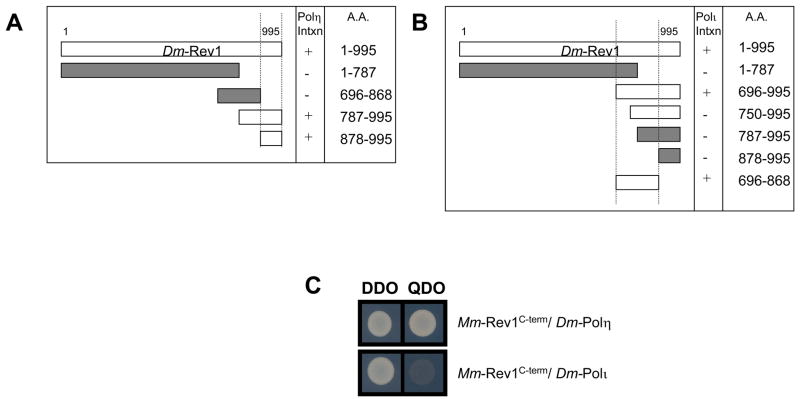

3.3 Drosophila Polη and Polι have different requirements for an interaction with Rev1

The interaction between Drosophila Rev1 and Drosophila Polη or Polι was further examined to determine a requirement for the Rev1 C-terminal region, as previously demonstrated in mice and humans. As shown in Fig. 6A, the C-terminal 117 amino acids of Drosophila Rev1 are necessary and sufficient for an interaction with Drosophila Polη. However, a region adjacent to the C-terminus of Drosophila Rev1 is required for its interaction with Polκ (Fig. 6B). Unlike the C-terminal domain, this region of Drosophila Rev1 is poorly conserved, even in orthologs from mosquitoes (data not shown). Additional experiments demonstrated a robust interaction between mouse Rev1 C-terminus and Drosophila Polη, but not between the mouse Rev1 C-terminus and Drosophila Polι (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. Drosophila Polη and Polι have different requirements for interaction with Rev1.

(A) Drosophila Rev1 interacts with Drosophila Polη through its conserved C-terminal domain (~117a.a.). (B) Drosophila Polι requires amino acids upstream of the Drosophila Rev1 C-terminus. (C) Drosophila Polη interacts with the C-terminus (~120a.a.) of mouse Rev1, while Drosophila Polι does not.

In summary, interactions between Rev1 protein and specialized DNA polymerases from the Y-family (Polη, Polι or Polκ) from mouse or humans are apparently conserved in the fruit fly D. melanogaster, but not in the worm C. elegans or the yeasts S. cerevisiae or S. pombe. Furthermore, whereas Drosophila Polη interacts with the conserved C-terminus of Drosophila Rev1, Drosophila Polι exhibits a different requirement for an interaction with Drosophila Rev1.

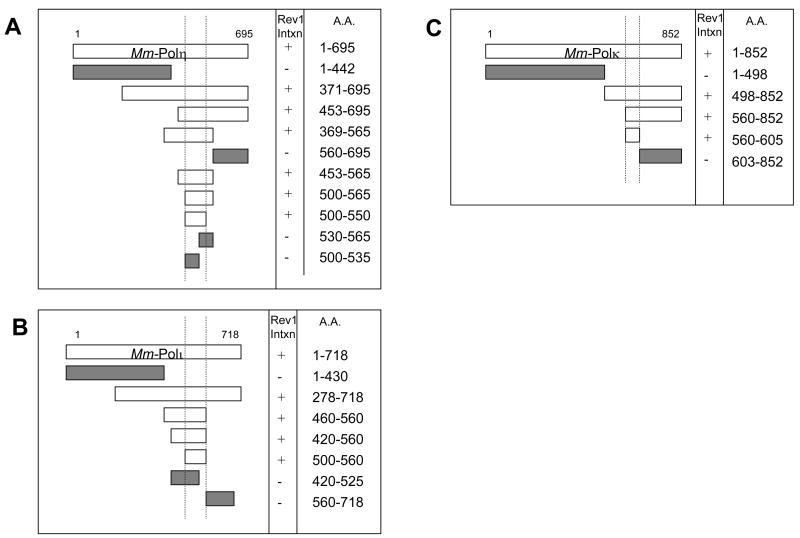

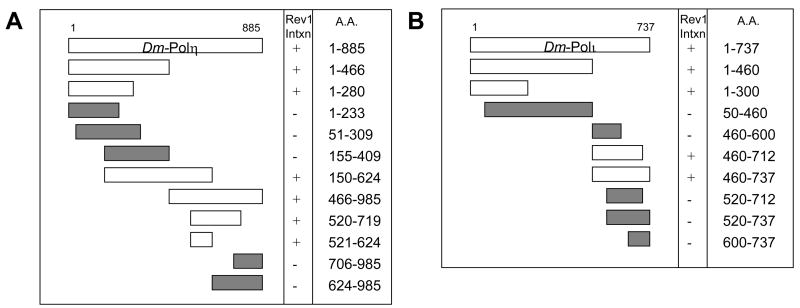

3.4 Mapping Rev1-interaction domains in Y-family DNA polymerases

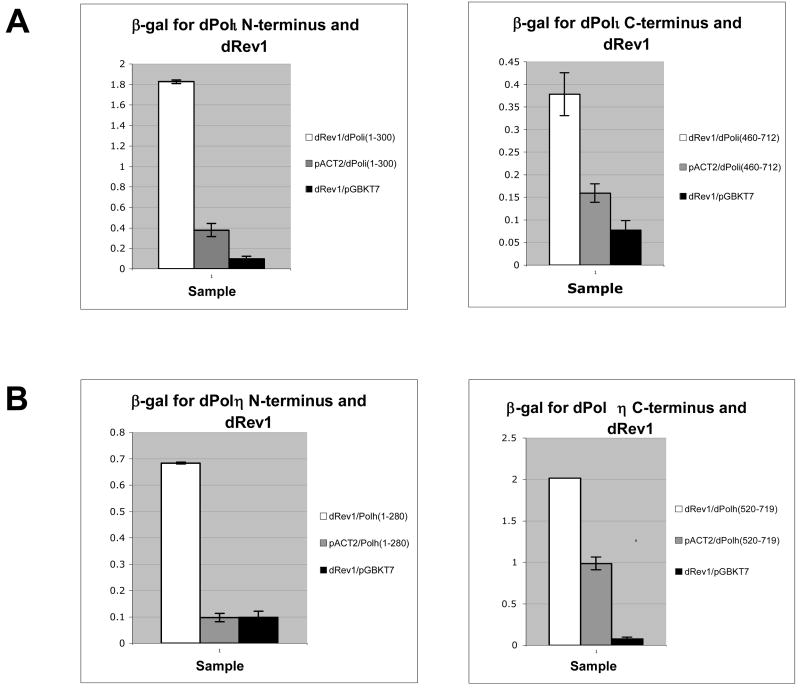

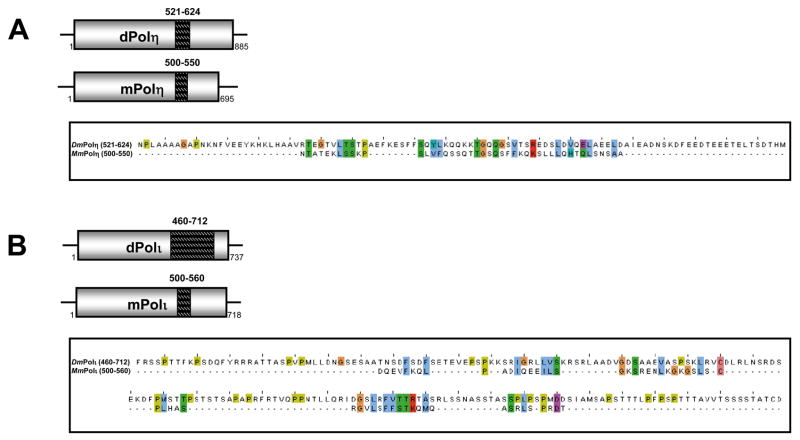

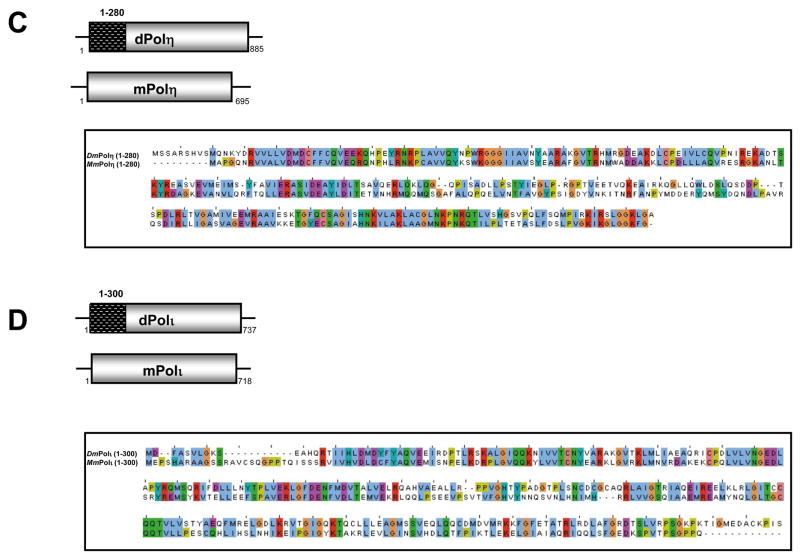

Having identified a requirement for the C-terminal region of mouse and Drosophila Rev1 protein for their interaction with some Y-family DNA polymerases, we sought to identify and compare the Rev1-binding domains in these DNA polymerases. Truncated cDNAs for mouse Polη, Polι, and Polκ were constructed and tested for their ability to interact with full-length mouse Rev1 in the yeast two-hybrid assay. With respect to the mouse polymerases, regions spanning ~50 amino acids in the C-terminal half of Polη, Polι, and Polκ supported an interaction with Rev1 (Fig. 7). Similar experiments were performed with truncations of Drosophila Polη and Polι. Once again, regions in the C-terminal half of both proteins supported an interaction with Drosophila Rev1 (Fig. 8). Remarkably, interactions with Drosophila Rev1 were also observed in the presence of an N-terminal 280 amino acid peptide from Drosophila Polη and an N-terminal 300 amino acid peptide from Drosophila Polι (Fig. 8). These observations were confirmed using a β-galactosidase reporter assay (Fig. 9).

Figure 7. Mapping of mouse Rev1-interaction domains in Y-family DNA polymerases.

The interaction between mouse Rev1 and the mouse Y-family polymerases requires a region spanning ~50 a.a. in the C-terminal half of (A) mouse Polη (500–550), (B) mouse Polι (500–560), and (C) mouse Polκ (560–605).

Figure 8. Drosophila Polη and Polι bind Drosophila Rev1 with two independent regions.

(A) Drosophila Polη and (B) Drosophila Polι interact with Drosophila Rev1 via an N-terminal peptide as well as a region located in the C-terminal half of each protein.

Figure 9. Expression of β-galactosidase confirms two Drosophila Rev1 binding domains in Drosophila Polη and Polι.

(A) Drosophila Polη and (B) Drosophila Polη interact with Drosophila Rev1 via an N-terminal peptide as well as a region located in the C-terminal half of each protein. Full-length protein interactions for Polη and Polι are set at a value=1 unit (not shown). All displayed values are normalized to the full-length interaction.

Amino acid sequences of the Rev1-interacting regions of Polη and Polι from mouse and Drosophila are shown in Fig. 10. The similarly located interaction regions are poorly conserved between mouse and Drosophila (Fig. 10 A, B). In contrast, the N-terminal regions of Drosophila Polη and Polι comprise the polymerase domain proper and are well conserved in mice (Fig. 10 C, D). These findings reveal a paradox. The Rev1-interacting regions that are located adjacent to the C-termini of various Y-family polymerases represent the hinge between the N-terminal polymerase domain and the C-terminal Zn-finger and, as noted above, are poorly conserved, with no reliable alignment observed outside groups of closely related species. For instance, the Rev1-binding regions of mouse Polκ, Polη, and Polι show significant sequence conservation only within the respective sets of mammalian orthologous proteins: neither orthologs from more distant species nor paralogs could be reliably aligned within these regions [34,35]. Although the Rev1-binding regions of the Y-family polymerases lack evidence of evolutionary conservation, these regions are predicted to be enriched in disordered structures (Supplemental Fig. 1) [33]. In contrast, the N-terminal regions of Drosophila Polη and Polι, which also interact with Drosophila Rev1, belong to the polymerase domain proper that is highly conserved in most eukaryotes.

Figure 10. Amino acid sequence conservation of Rev1-binding regions in Drosophila and mouse.

(A) An alignment of the experimentally determined, similarly located Rev1-binding region in Drosophila and mouse Polη and (B) Drosophila and mouse Polι. (C) An alignment of the N-terminal Rev1-binding region of Drosphila Polη reveals close homology with the N-terminus of mouse Polη, which does not exhibit an interaction with mouse Rev1.

4. Discussion

Previous studies indicate that Rev1 protein in eukaryotic organisms maintains one or more functions in DNA damage tolerance independent of its dCMP transferase activity [6,7]. In light of the observation that human and mouse Rev1 interact with multiple Y-family DNA polymerases via a highly conserved C-terminal domain [9–11], we inquired whether similar if not identical interactions are conserved in invertebrates and fungi that also possess Y-family homologues. Surprisingly, given that S. cerevisiae Rev1 and Polη (Rad30) are both required for the replicative bypass (translesion DNA synthesis) of lesions in DNA generated by exposure of cells to UV radiation, we find no evidence of interaction between S. cerevisiae Rev1 and Polη (Rad30 protein), regardless of whether cells were exposed to UV radiation or not. Remarkably, the amino acid sequence of the Rev1 C-terminus of S. cerevisiae shows considerable sequence similarity to the corresponding region of Drosophila Rev1, which interacts with both Drosophila Polη and Polι (Fig. 4A, 4B). Thus, the interaction between the C-terminus of Rev1 and Polη appears to be an animal-specific innovation, which is compatible with the high level of conservation of this portion of the Rev1 sequence in animals as compared to the limited conservation between animals and fungi (Fig. 1). These findings are consistent with the observation that, unlike Rev1 and the Polζ complex (Rev3/Rev7) in S. cerevisiae, Rev1 and Rad30 do not exhibit an epistatic interaction with respect to UV radiation sensitivity [26].

An interaction between the polymerase accessory domain (PAD) of purified Rev1 and Polη (Rad30 protein) in vitro was recently reported in S. cerevisiae [36]. This interaction was not documented in vivo. However, the authors reported that purified yeast Rev1/Rev7 complex precludes interaction between Rev1 with Polη in vitro [36]. Conceivably, in the native cellular environment of S. cerevisiae where Rev7 (the regulatory subunit of DNA polymerase ζ) is abundant, this protein sequesters most, if not all Rev1, thus preventing complex formation between Rev1 and Polη (Rad30 protein).

Recent studies from one of our laboratories (GCW) have documented that Rev1 protein levels are dramatically cell cycle regulated in S. cerevisiae [24]. To further explore a possible functional relationship between Rev1 and Y-family polymerases in S. cerevisiae we performed epistasis analysis between Rev1 and Polη (Rad30 protein) in G1 or G2 arrested cells with respect to UV radiation exposure, but observed no cell-cycle dependent genetic relationship at low dosage of irradiation. Similar results have been reported for asynchronous cells [24 and R. Woodruff and G. Walker, unpublished results]. The absence of physical and genetic interactions may explain the observation that S. cerevisiae Rev1 and Rad30 are not required for the replicative bypass of the same UV radiation-induced cognate lesions [7,37]. Indeed, since Rad30 is apparently not required for UV radiation-induced mutagenesis (unlike Rev1 or Polζ), it has been speculated that Polη (Rad30) protein participates in an error-free repair pathway independent of Rev1 protein [26,27]. In summary, it seems reasonable to suggest that the C-terminus of Rev1 acquired novel functions in more complex eukaryotes. Alternatively, different sets of interactions may execute similar functions, as suggested by the observation that S. pombe Rev7 protein interacts with S. pombe Rev1, Polκ and Polη (eso1+) [J. N. Kosarek and E. C. Friedberg, unpublished results].

The observation that Drosophila Rev1 protein interacts with both Drosophila Polη and Polι is intriguing. Drosophila is not endowed with an adaptive immune system [38] suggesting that these interactions did not evolve to support somatic hypermutation, a process in which several Y-family polymerases in higher eukaryotes are implicated [39,40]. Remarkably, Drosophila Polη interacts with the C-terminal 117 amino acids of Drosophila Rev1, just as in mouse and humans. Drosophila Polη also maintains an interaction with the C-terminus of mouse Rev1, suggesting functional analogy between the C-terminal domains of mouse and Drosophila, despite reduced sequence conservation. In contrast, Drosophila Polι does not interact with the C-terminus of Drosophila Rev1, but rather with a distinct domain that does not appear to be conserved in Rev1 protein from the other species examined, nor does it show any sequence similarity to closely related species (data not shown). The minimal conservation of this Polι-binding domain in Drosophila Rev1 suggests that Drosophila Rev1 may have a unique mechanism in vivo for switching between Polι and Polη.

Drosophila Polη and Polι each utilize two independent domains for interacting with Drosophila Rev1. In addition to the domain in the C-terminal half of these proteins, (similarly located to the Rev1-interaction domains identified in the mouse homologues of Polη, Polι, and Polκ) we identified a second Drosophila Rev1-interaction domain located at the N-terminus of Drosophila Polη and Polι Fig. 8A and 8B). The N-terminal motifs of Drosophila Polι and Polη that bind Rev1 contain the five characteristic Y-family motifs, including the catalytic domains of the polymerases, which are well conserved among all species. The N-terminal fragment of Drosophila Polη can also support an interaction with mouse Rev1 protein (data not shown), suggesting there are functional differences between the N-terminus of mouse Polη and Drosophila Polη, notwithstanding the high degree of amino acid conservation (Figure 10 C). The additional observation that Drosophila Rev1 interacts with the catalytic domains of Drosophila Polη and Polι raises the possibility that these interactions may affect the catalytic properties of these proteins, as has been shown for the interaction between yeast Rev1 and Rev3 (Polζ) [41].

The Rev1-interacting regions in the similarly located mouse and Drosophila Y-family polymerases examined in our studies are predicted to be enriched in disordered structures (Supplemental Fig. 1). Disordered interaction domains have been observed among transcription factors [42] and a variety of other regulatory proteins. A structured protein that interacts with multiple unstructured partners has also been observed [43]. Furthermore, functionally analogous domains have been observed which have little sequence similarity but share intrinsic disorder [43], which is predicted to be the case for Rev1-binding partners. UmuD and UmuD’ proteins from E. coli which are also involved in DNA damage tolerance, have also been shown to be intrinsically disordered (S.M. Simon, F.J.R. Sousa, R.S. Mohana-Borges and G. C. Walker, manuscript in preparation). UmuD and UmuD’ are the products of the umuD gene; they stably interact with and functionally regulate the activity of the prokaryotic Y-family member UmuC, and interact with many other proteins, including RecA, DinB, and polymerase subunits α, β, and ε[44–50].

When the ability of the Rev1 C-terminus to interact with Y-family members is related to the phylogeny of species studied here, we observe that this function appears to have been lost outside coelomates, higher metazoans which possess a body cavity (Fig. 11, adapted from [51]) [52–55]. In addition, C. elegans (a pseudocoelomate) is a more rapidly evolving species [52], which is supported by our observation that the C-terminal domain of Rev1 was lost in nematodes but retained in yeast.

Figure 11. The ability of the Rev1 C-terminus to interact with other Y-family polymerases and its relationship to the phylogeny of species.

This tree describes a predominant evolutionary relationship between nematodes, arthropods, and humans, known as Coelomata. Here, humans and arthropods are sister taxa, where the nematode sequence is basal to the fly-human clade. C. elegans is a ‘faster evolving’ species of nematode(pseudocoelomate), contributing to its position on the tree. Yeast is an outgroup. (Adapted from [51]).

*Indicates the ability of the Rev1 C-terminus to bind other Y-family DNA polymerases.

Interaction between Rev1 and Rev7 (the catalytic subunit of Polζ) is maintained in all organisms studied, suggesting that these proteins co-evolved to maintain an essential function for TLS. Studies in yeast have shown that Polζ is indispensable for DNA damage-induced mutagenesis and that Rev1 is required for the function of Polζ [4,56]. Furthermore, kinetic analyses have shown that Rev1 enhances Polζ function during mismatch extension as well as extension past abasic sites and [6–4] photoproducts [41]. While the specific role of the Rev1/Rev7 interaction remains to be determined, our results provide evidence that this interaction may underlie a distinctly conserved TLS function.

In conclusion, in our efforts to expand studies of the Rev1/Y-family polymerase interactions to a more tractable model organism, we conclude that no single eukaryote thus far examined can be considered a prototypic model system for generalizing the molecular mechanism of TLS in eukaryotes, and that particular domains of these proteins and their functions are more divergent than originally thought. These studies should advocate special consideration when making mechanistic extrapolations from lower to higher eukaryotes and vice versa.

Supplementary Material

Predictions are shown according to each of the three definitions below, where an indication of disorder is represented by uppercase letters. The regions in question are highlighted in grey. Loops/coils: Residues are assigned as belonging to one of several secondary structure types. Loops/coils are not necessarily disordered, however protein disorder is only found within loops. It follows that one can use loop assignments as a necessary but not sufficient requirement for disorder. Hot loops: These constitute a subset of the above, namely those loops with a high degree of mobility as determined from C-alpha temperature (B-)factors. It follows that highly dynamic loops should be considered protein disorder. Missing coordinates in X-Ray structure as defined by REMARK-465 entries in PDB. Non-assigned electron densities most often reflect intrinsic disorder, and have been used early on in disorder prediction. *To interpret the predictions it is crucial to keep in mind that the three predictors are not all predicting the same kind of disorder. Agreement between the predictors should thus not be expected [33].

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Timothy Megraw and Shaila Kotadia for providing materials and protocols for Drosophila experiments. We thank Christopher Lawrence, Zhigang Wang, and Takeshi Todo for providing polymerase constructs. We also thank Burke Squires for assistance with preliminary sequence alignments and acknowledge the C. elegans Genome Consortium for providing N2 hermaphrodite worms. G.C.W. is an American Cancer Society Research Professor and is supported by National Cancer Institute (NCI) Grant CA21615-27. This work was also supported by grant ES11344 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ECF) and in part by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant ESO15818 (GCW).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Friedberg EC. Suffering in silence: the tolerance of DNA damage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:943–953. doi: 10.1038/nrm1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. American Society for Microbiology; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedberg EC, Lehmann AR, Fuchs RP. Trading places: how do DNA polymerases switch during translesion DNA synthesis? Mol Cell. 2005;18:499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence CW. Cellular functions of DNA polymerase ζ and Rev1 protein. Adv Protein Chem. 2004;69:167–203. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)69006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otsuka C, Loakes D, Negishi K. The role of deoxycytidyl transferase activity of yeast Rev1 protein in the bypass of abasic sites. Nucleic Acids Res Suppl. 2002:87–88. doi: 10.1093/nass/2.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross AL, Simpson LJ, Sale JE. Vertebrate DNA damage tolerance requires the C-terminus but not BRCT or transferase domains of REV1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:1280–1289. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson JR, Gibbs PE, Nowicka AM, Hinkle DC, Lawrence CW. Evidence for a second function for Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rev1p. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:549–554. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo C, Sonoda E, Tang TS, Parker JL, Bielen AB, Takeda S, Ulrich HD, Friedberg EC. REV1 protein interacts with PCNA: significance of the REV1 BRCT domain in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell. 2006;23:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo C, Fischhaber PL, Luk-Paszyc MJ, Masuda Y, Zhou J, Kamiya K, Kisker C, Friedberg EC. Mouse Rev1 protein interacts with multiple DNA polymerases involved in translesion DNA synthesis. Embo J. 2003;22:6621–6630. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tissier A, Kannouche P, Reck MP, Lehmann AR, Fuchs RP, Cordonnier A. Co-localization in replication foci and interaction of human Y-family members, DNA polymerase pol η and REVl protein. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1503–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohashi E, Murakumo Y, Kanjo N, Akagi J, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Ohmori H. Interaction of hREV1 with three human Y-family DNA polymerases. Genes Cells. 2004;9:523–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haracska L, Kondratick CM, Unk I, Prakash S, Prakash L. Interaction with PCNA is essential for yeast DNA polymerase η function. Mol Cell. 2001;8:407–415. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haracska L, Johnson RE, Unk I, Phillips BB, Hurwitz J, Prakash L, Prakash S. Targeting of human DNA polymerase ι to the replication machinery via interaction with PCNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14256–14261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261560798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haracska L, Unk I, Johnson RE, Phillips BB, Hurwitz J, Prakash L, Prakash S. Stimulation of DNA synthesis activity of human DNA polymerase κ by PCNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:784–791. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.3.784-791.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bienko M, Green CM, Crosetto N, Rudolf F, Zapart G, Coull B, Kannouche P, Wider G, Peter M, Lehmann AR, Hofmann K, Dikic I. Ubiquitin-binding domains in Y-family polymerases regulate translesion synthesis. Science. 2005;310:1821–1824. doi: 10.1126/science.1120615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo C, Tang TS, Bienko M, Parker JL, Bielen AB, Sonoda E, Takeda S, Ulrich HD, Dikic I, Friedberg EC. Ubiquitin-binding motifs in REV1 protein are required for its role in the tolerance of DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8892–8900. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01118-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson JR, Lawrence CW, Hinkle DC. Deoxycytidyl transferase activity of yeast REV1 protein. Nature. 1996;382:729–731. doi: 10.1038/382729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan F, Zhang Y, Rajpal DK, Wu X, Guo D, Wang M, Taylor JS, Wang Z. Specificity of DNA lesion bypass by the yeast DNA polymerase η. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8233–8239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohkumo T, Masutani C, Eki T, Hanaoka F. Deficiency of the Caenorhabditis elegans DNA polymerase η homologue increases sensitivity to UV radiation during germ-line development. Cell Struct Funct. 2006;31:29–37. doi: 10.1247/csf.31.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishikawa T, Uematsu N, Mizukoshi T, Iwai S, Iwasaki H, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Ueda R, Ohmori H, Todo T. Mutagenic and nonmutagenic bypass of DNA lesions by Drosophila DNA polymerases dpolη and dpolι. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15155–15163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009822200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao X, Muller EG, Rothstein R. A suppressor of two essential checkpoint genes identifies a novel protein that negatively affects dNTP pools. Mol Cell. 1998;2:329–340. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knop M, Siegers K, Pereira G, Zachariae W, Winsor B, Nasmyth K, Schiebel E. Epitope tagging of yeast genes using a PCR-based strategy: more tags and improved practical routines. Yeast. 1999;15:963–972. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199907)15:10B<963::AID-YEA399>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Souza S, Walker GC. Novel role for the C terminus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rev1 in mediating protein-protein interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8173–8182. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00202-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waters LS, Walker GC. The critical mutagenic translesion DNA polymerase Rev1 is highly expressed during G(2)/M phase rather than S phase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8971–8976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510167103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skoneczna A, McIntyre J, Skoneczny M, Policinska Z, Sledziewska-Gojska E. Polymerase η is a short-lived, proteasomally degraded protein that is temporarily stabilized following UV irradiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:1074–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald JP, Levine AS, Woodgate R. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD30 gene, a homologue of Escherichia coli dinB and umuC, is DNA damage inducible and functions in a novel error-free postreplication repair mechanism. Genetics. 1997;147:1557–1568. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.4.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roush AA, Suarez M, Friedberg EC, Radman M, Siede W. Deletion of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene RAD30 encoding an Escherichia coli DinB homolog confers UV radiation sensitivity and altered mutability. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;257:686–692. doi: 10.1007/s004380050698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duncker BP, Shimada K, Tsai-Pflugfelder M, Pasero P, Gasser SM. An N-terminal domain of Dbf4p mediates interaction with both origin recognition complex (ORC) and Rad53p and can deregulate late origin firing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16087–16092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252093999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schaffer AA, Aravind L, Madden TL, Shavirin S, Spouge JL, Wolf YI, Koonin EV, Altschul SF. Improving the accuracy of PSI-BLAST protein database searches with composition-based statistics and other refinements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2994–3005. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.14.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuff JA, Clamp ME, Siddiqui AS, Finlay M, Barton GJ. JPred: a consensus secondary structure prediction server. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:892–893. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.10.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linding R, Jensen LJ, Diella F, Bork P, Gibson TJ, Russell RB. Protein disorder prediction: implications for structural proteomics. Structure. 2003;11:1453–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.HDa GT, Thompson JD. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cuff JACM, Siddiqui AS, Finlay M, Barton GJ. JPred: a consensus secondary structure prediction server. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:892–893. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.10.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Acharya N, Haracska L, Prakash S, Prakash L. Complex formation of yeast Rev1 with DNA polymerase η. Mol Cell Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1128/MCB.01478-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibbs PE, McDonald J, Woodgate R, Lawrence CW. The relative roles in vivo of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pol η, Pol ζ, Rev1 protein and Pol32 in the bypass and mutation induction of an abasic site, T-T (6–4) photoadduct and T-T cis-syn cyclobutane dimer. Genetics. 2005;169:575–582. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.034611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medzhitov R, Janeway C., Jr Innate immune recognition: mechanisms and pathways. Immunol Rev. 2000;173:89–97. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ross AL, Sale JE. The catalytic activity of REV1 is employed during immunoglobulin gene diversification in DT40. Mol Immunol. 2006;43:1587–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masuda K, Ouchida R, Hikida M, Kurosaki T, Yokoi M, Masutani C, Seki M, Wood RD, Hanaoka FJOW. DNA polymerases η and θ function in the same genetic pathway to generate mutations at A/T during somatic hypermutation of Ig genes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17387–17394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Acharya N, Johnson RE, Prakash S, Prakash L. Complex formation with Rev1 enhances the proficiency of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase ζ for mismatch extension and for extension opposite from DNA lesions. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:9555–9563. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01671-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu J, Perumal NB, Oldfield CJ, Su EW, Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Intrinsic disorder in transcription factors. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6873–6888. doi: 10.1021/bi0602718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bustos DM, Iglesias AA. Intrinsic disorder is a key characteristic in partners that bind 14-3-3 proteins. Proteins. 2006;63:35–42. doi: 10.1002/prot.20888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar R, Thompson EB. Gene regulation by the glucocorticoid receptor: structure:function relationship. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;94:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang M, Shen X, Frank EG, O'Donnell M, Woodgate R, Goodman MF. UmuD'(2)C is an error-prone DNA polymerase, Escherichia coli pol V. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8919–8924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jarosz DF, Beuning PJ, Cohen SE, Walker GC. Y-family DNA polymerases in Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sutton MD, Opperman T, Walker GC. The Escherichia coli SOS mutagenesis proteins UmuD and UmuD' interact physically with the replicative DNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12373–12378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shinagawa H, Iwasaki H, Kato T, Nakata A. RecA protein-dependent cleavage of UmuD protein and SOS mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:1806–1810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burckhardt SE, Woodgate R, Scheuermann RH, Echols H. UmuD mutagenesis protein of Escherichia coli: overproduction, purification, and cleavage by RecA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:1811–1815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nohmi T, Battista JR, Dodson LA, Walker GC. RecA-mediated cleavage activates UmuD for mutagenesis: mechanistic relationship between transcriptional derepression and posttranslational activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:1816–1820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mushegian AR, Garey JR, Martin J, Liu LX. Large-scale taxonomic profiling of eukaryotic model organisms: a comparison of orthologous proteins encoded by the human, fly, nematode, and yeast genomes. Genome Res. 1998;8:590–598. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.6.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hedges SB. The origin and evolution of model organisms. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:838–849. doi: 10.1038/nrg929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng J, Rogozin IB, Koonin EV, Przytycka TM. Support for the coelomata clade of animals from a rigorous analysis of the pattern of intron conservation. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:2583–2592. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rogozin IB, Wolf YI, Carmel L, Koonin EV. Analysis of Rare Amino Acid Replacements Supports the Coelomata Clade. Mol Biol Evol. 2007 doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolf YI, Rogozin IB, Koonin EV. Coelomata and not Ecdysozoa: evidence from genome-wide phylogenetic analysis. Genome Res. 2004;14:29–36. doi: 10.1101/gr.1347404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baynton K, Bresson-Roy A, Fuchs RP. Distinct roles for Rev1p and Rev7p during translesion synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:124–133. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Predictions are shown according to each of the three definitions below, where an indication of disorder is represented by uppercase letters. The regions in question are highlighted in grey. Loops/coils: Residues are assigned as belonging to one of several secondary structure types. Loops/coils are not necessarily disordered, however protein disorder is only found within loops. It follows that one can use loop assignments as a necessary but not sufficient requirement for disorder. Hot loops: These constitute a subset of the above, namely those loops with a high degree of mobility as determined from C-alpha temperature (B-)factors. It follows that highly dynamic loops should be considered protein disorder. Missing coordinates in X-Ray structure as defined by REMARK-465 entries in PDB. Non-assigned electron densities most often reflect intrinsic disorder, and have been used early on in disorder prediction. *To interpret the predictions it is crucial to keep in mind that the three predictors are not all predicting the same kind of disorder. Agreement between the predictors should thus not be expected [33].