SUMMARY

Calmodulin (CaM) regulation of Ca2+ channels is central to Ca2+ signaling. CaV1 versus CaV2 classes of these channels exhibit divergent forms of regulation, potentially relating to customized CaM/IQ interactions among different channels. Here, we report the crystal structures for the Ca2+/CaM—IQ domains of both CaV2.1 and CaV2.3 channels. These highly similar structures emphasize that major CaM contacts with the IQ domain extend well upstream of traditional consensus residues. Surprisingly, upstream mutations strongly diminished CaV2.1 regulation, whereas downstream perturbations had limited effects. Furthermore, our CaV2 structures closely resemble published Ca2+/CaM—CaV1.2 IQ structures, arguing against CaV1/2 regulatory differences based solely on contrasting CaM/IQ conformations. Instead, alanine scanning of the CaV2.1 IQ domain, combined with structure-based molecular simulation of corresponding CaM/IQ binding energy perturbations, suggests that the C-lobe of CaM partially dislodges from the IQ element during channel regulation, allowing exposed IQ residues to trigger regulation via isoform-specific interactions with alternative channel regions.

Keywords: Ca2+ channel, crystal structure, structure-function relations, calmodulin, IQ domain, ion-channel modulation, Ca2+ signaling

INTRODUCTION

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels of the CaV1-2 family constitute dominant sources of Ca2+ entry that trigger numerous biological functions (Dolmetsch, 2003; Dunlap et al., 1995). Fitting with their salient functional roles, these channels are subject to extensive positive and negative Ca2+ feedback control of their opening, with calmodulin (CaM) serving as the Ca2+ sensor (Evans and Zamponi, 2006). In particular, for CaV2 channels which predominate in triggering CNS neurotransmitter release (Wheeler et al., 1994), these feedback regulatory systems are believed to influence short-term synaptic plasticity (Borst and Sakmann, 1998; Chaudhuri et al., 2005; Cuttle et al., 1998; Wykes et al., 2007; Xu and Wu, 2005), and thereby the computational repertoire of the brain (Abbott and Regehr, 2004; Tsodyks and Markram, 1997). In all of these contexts, CaM clearly exhibits powerful and unexpected forms of Ca2+ decoding (Dunlap, 2007), the principles of which may generalize to numerous Ca2+ signaling systems. As such, the CaM regulation of Ca2+ channels not only has specific consequences for Ca2+ signaling, but may also represent a general mechanistic paradigm for Ca2+ decoding and ion-channel modulation.

CaM/Ca2+ channel regulation includes several provocative functional features. First, in resting channels, Ca2+-free CaM (apoCaM) is already preassociated with the cytoplasmic region of channels, rendering CaM as a ‘resident’ Ca2+ sensor (Erickson et al., 2001; Erickson et al., 2003b; Pitt et al., 2001). Second, CaM can ‘bifurcate’ the local Ca2+ signal in the channel nanodomain: Ca2+ binding to the C-terminal lobe of CaM (C-lobe) alone can trigger one type of regulatory process on a channel; and Ca2+ binding to the N-terminal lobe (N-lobe) can induce a separate form of modulation (Chaudhuri et al., 2005; DeMaria et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2006). Intriguingly, despite evidence that a single CaM molecule orchestrates both processes (Mori et al., 2004; Yang, 2007), C-lobe induced regulation persists with millimolar concentrations of intracellular Ca2+ chelators like EGTA and BAPTA, whereas N-lobe processes are largely inhibited by such Ca2+ buffering (Liang et al., 2003). Not every channel manifests both C- and N-lobe functions, but the coexistence of both processes has been clearly demonstrated in CaV2.1 and CaV1.3 channels (Chaudhuri et al., 2005; DeMaria et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2006). Finally, the polarity of channel modulation by a given lobe of CaM can be inverted between closely similar Ca2+ channel types. For CaV2.1 channels, the C-lobe triggers a fast Ca2+-dependent facilitation of opening (CDF) (Chaudhuri et al., 2005; DeMaria et al., 2001), while the N-lobe produces a slower Ca2+-dependent inactivation (CDI) (Chaudhuri et al., 2005; DeMaria et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2003). By contrast, for CaV1.2 channels, Ca2+ binding to the C-lobe triggers a rapid CDI process, while the N-lobe initiates a more gradual and distinct CDI mechanism (Alseikhan et al., 2002; Dick et al., 2007; Peterson et al., 1999). Remarkably, structural similarities and single-channel data hint that the CaV2.1 and CaV1.2 C-lobe processes may be the same, only with opposing polarity (CDF versus CDI) (Chaudhuri et al., 2007). Probing this C-lobe directional inversion thereby promises rich mechanistic insights.

By contrast to function, less is known about the underlying structural bases ofCaM/channel regulation. Most of the structural determinants of CaM regulation of CaV1–2 channels are localized to their main, pore-forming α1 subunits, specifically in the upstream third of subunit carboxy termini (Figure 1A, left, ‘CI’ region) (Evans and Zamponi, 2006). FRET and biochemical evidence indicates that apoCaM is preassociated with a consensus IQ domain, and an immediately upstream preIQ region (Erickson et al., 2001; Erickson et al., 2003a; Pitt et al., 2001). Ca2+ binding to CaM may cause rearrangements of CaM on these same segments (Evans et al., 2004), as Ca2+/CaM binds to IQ domains of many CaV1–2 channels (DeMaria et al., 2001; Peterson et al., 1999; Zuhlke et al., 1999), as well as to preIQ regions of CaV2.1 (Evans et al., 2004) and CaV1.2 (Erickson et al., 2003a; Kim et al., 2004; Pate et al., 2000; Pitt et al., 2001; Romanin et al., 2000; Tang et al., 2003). These rearrangements somehow modulate channel gating, with the potential involvement of an EF-hand-like channel module as a transduction element for C-lobe mediated processes (Chaudhuri et al., 2004; de Leon et al., 1995; Kim et al., 2004; Peterson et al., 2000; Zuhlke and Reuter, 1998). Given the multiplicity of structural determinants within a single molecular complex, the precise sequence underlying Ca2+-dependent regulation of channels remains unclear. Nonetheless, Ca2+/CaM interaction with the IQ domain has been viewed as potentially central to initiating a chain of ensuing regulatory events, because mutations within this domain can eliminate both CDF and CDI in CaV2.1 (DeMaria et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2003); and CDI within CaV1.2, CaV1.3, CaV2.2, and CaV2.3 channels (Evans and Zamponi, 2006; Yang et al., 2006). Indeed, these complexes between CaM and channel IQ domains represent sophisticated additions to a family of CaM—IQ assemblies, originally defined for CaM interactions with unconventional myosins, and now encompassing over 50 different mammalian molecules (Hoeflich and Ikura, 2002). Unlike classical CaM binding targets, IQ domains support both apoCaM and Ca2+/CaM interactions that underlie exquisite functional modulation of affiliated molecules (Black et al., 2006), nowhere more evident than in the setting of Ca2+ channels.

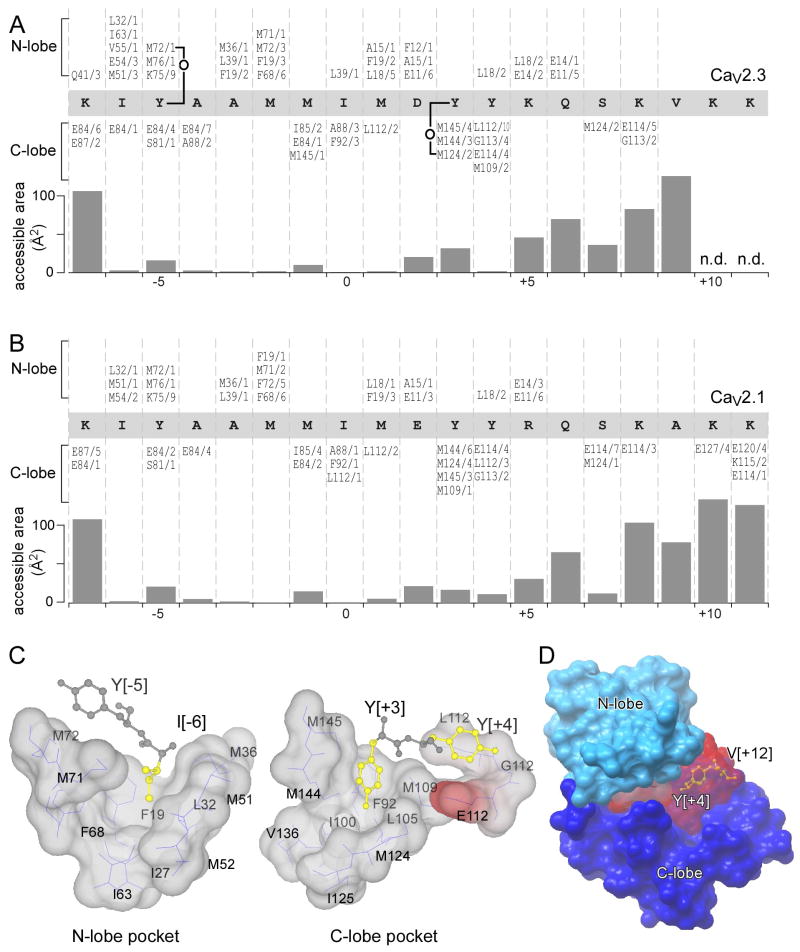

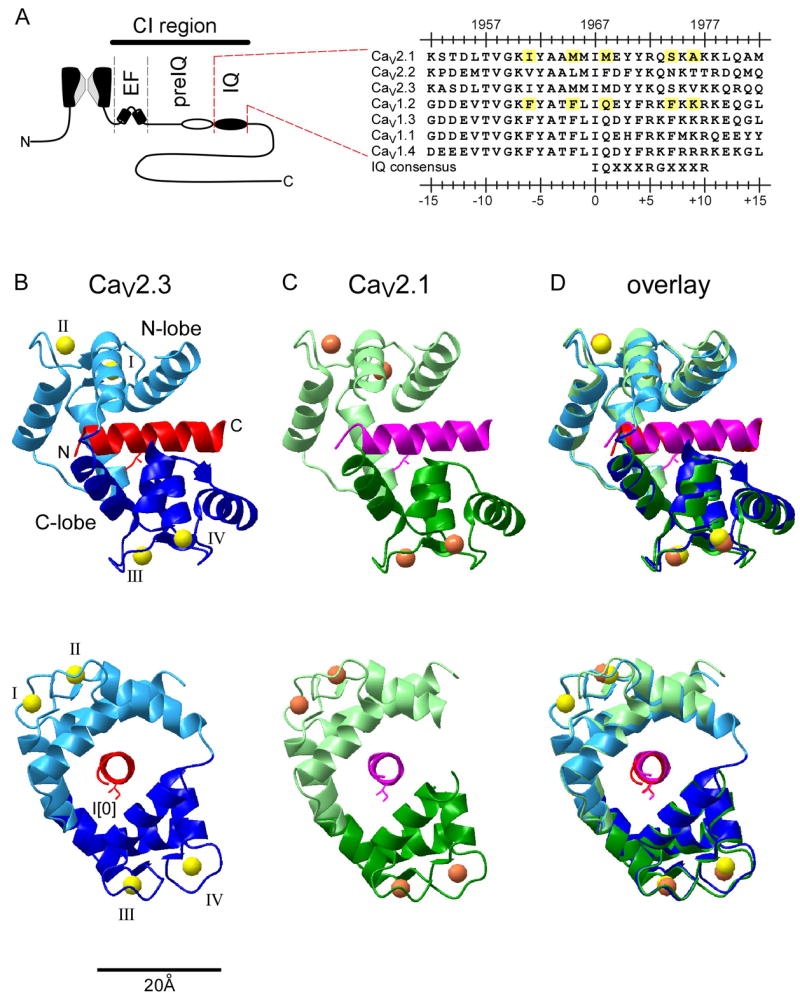

Figure 1. Structures of Ca2+/CaM bound to the IQ domain of CaV2.1 and CaV2.3.

(A) IQ domains of CaV Ca2+ channels. Left, cartoon of pore-forming α1 subunits of CaV channels, with carboxytail landmarks, as labeled. EF, EF-hand motif; IQ, IQ domain; preIQ, intervening sequence important for apoCaM binding. CI region, structural ‘hot spot’ for CaM/channel regulation. Right, aminoacid sequence alignment of IQ domains of CaV channels, with IQ consensus pattern in bottom row. Upper calibration references amino acid coordinates for CaV2.1 α1A subunit; bottom calibration gives universal coordinates with key isoleucine set to position 0. Yellow highlights, differences between CaV2.1 and CaV1.2 proposed to explain contrasting regulatory profiles between these two channel types. (B) Ribbon-diagram representations of Ca2+/CaM bound to the IQ domain of CaV2.3, from saggital (top) and coronal (bottom) viewpoints. The IQ domain is colored in red; amino-terminal end towards the left. N-and C-lobes are differentially colored as labeled. Side chain of I[0] residue shown as stick diagram. The four EF hands with Ca2+ (balls) are numbered in order. (C) Analogous CaV2.1 structure. (D) Superimposition of structures in panels B and C, indicating close similarity.

Very recently, the first atomic resolution structures of Ca2+ regulatory modules have been reported (Fallon et al., 2005; Van Petegem et al., 2005). In keeping with the presumed centrality of the IQ domain, these structures have focused upon Ca2+/CaM complexed with the IQ element of CaV1.2. Ca2+/CaM interacts extensively with this IQ domain, consistent with a Ca2+/CaM effector role for this site (Van Petegem et al., 2005). Interestingly, compared with CaV1 IQ domains, those for CaV2 channels differ at more than five positions (Figure 1A, right, yellow highlights), and these dissimilarities have been suggested by Van Petegem and colleagues to alter the structure of the IQ/CaM assembly, thereby accounting for the contrasting regulatory profiles of CaV2.1 versus CaV1.2 (Van Petegem et al., 2005). Given the rich mechanistic dividends pertaining to these oppposing modulatory profiles, this study explicitly tests for specific underlying differences in the structure of CaV2.1 versus CaV1.2 IQ domains in complex with Ca2+/CaM. Two crystal structures were here obtained: one for Ca2+/CaM in complex with the IQ domain of CaV2.3 channels; and the second for the analogous complex involving the IQ moiety of CaV2.1. Both structures were highly similar representatives of a generic CaV2 class structure, and correlation with functional analysis of an alanine mutational scan suggests that the C-lobe of CaM partially dislodges from the IQ element during channel regulation.

RESULTS

Recapitulation of distinctive features of the CaV IQ domains complexed with Ca2+/CaM

We utilized molecular replacement to solve two new crystal structures: one for Ca2+/CaM in complex with the IQ domain of CaV2.3 channels, resolved at a 2.2 Å resolution; and the second for the analogous complex involving the IQ moiety of CaV2.1 channels, at a 2.6 Å resolution. The search model was the analogous structure for CaV1.2 channels (C conformation, structure 2BE6) (Van Petegem et al., 2005). CaV2.3 and CaV2.1 complexes turned out to be highly similar, so the higher-resolution CaV2.3 structure best represents a generic CaV2 configuration. To facilitate comparison between IQ domains from different channels (Figure 1A, right), residues are numbered with the central isoleucine at position ‘0,’ here and throughout.

For the structure of Ca2+/CaM in complex with the CaV2.3 IQ domain, crystals exhibited an I4122 symmetry, and the asymmetric unit contained a single CaM/IQ complex with a 1:1 stoichiometry. The structure was notable in several regards (Figure 1B). First, CaM, as fully charged with four Ca2+ ions, envelopes an alpha helical IQ domain, which extends straight out without the mid-point bend seen in analogous CaV1 structures (Fallon et al., 2005; Van Petegem et al., 2005). Second, the CaV2.3 structure is also distinguished by a parallel orientation, wherein the N-lobe is positioned somewhat closer to the IQ amino terminus than is the C-lobe. This orientation is thus far unique to CaM/IQ structures of CaV channels (Fallon et al., 2005; Van Petegem et al., 2005), and CaM in complex with CaM-dependent kinase kinase (Osawa et al., 1999). Third, the two lobes of CaM are arrayed on opposite faces of the IQ helix; and the C- and N-lobes make little inter-domain contact compared to the majority of CaM/peptide structures (Hoeflich and Ikura, 2002), with only two residues from the different lobes of our structure residing within 4 Å of each other (T37 and N111). The features described under this third point enable CaM/IQ contacts to segregate between C- and N-lobe classes, as explicitly shown by the 4-Å contact map in Figure 2A. This segregation may facilitate the semi-autonomous regulatory action of these lobes in CaV1–2 channels (DeMaria et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2003; Liang et al., 2003; Peterson et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2006). Finally, the specifics of CaM interaction are characteristic of Ca2+/CaM—IQ complexes (Fallon et al., 2005; Van Petegem et al., 2005). Both C- and N-lobes made extensive hydrophobic and electrostatic contacts with the IQ segment (Figure 2A and 2C), respectively burying 582 and 702 Å2 in surface area at the IQ domain interface. Additionally, not only were IQ residues traditionally associated with CaM interaction ([I/L/V]QxxxRxxxx[R/K]) found to be important (Jurado et al., 1999), but so were numerous other hydrophobic anchors distributed throughout the segment (Figures 2A and 2C). In particular, multiple contacts are present upstream of the I[0] position, and the total buried surface area of the IQ domain was evenly split between upstream sites (618 Å2), and those from the I[0] position onwards (653 Å2). These extensive upstream contacts contrast with the traditional emphasis on downstream consensus residues. Figure 2C displays specific examples of intimate docking at both upstream and downstream residues, emphasizing the fit of I[−6] within a hydrophobic pocket of the N-lobe (left), as well as the anchoring of Y[+3] and Y[+4] residues into like features of the C-lobe. Indeed, the IQ domain demonstrates greater solvent exposure in its downstream half, compared to an almost completely buried upstream portion (Figures 2A, bottom; Figure 2D). These features contrast with the dominance of C-lobe and downstream-IQ interactions within the apoCaM/IQ structure for myosin (Houdusse et al., 2006).

Figure 2. Residue-by-residue interaction of CaV2 IQ domains with Ca2+/CaM.

(A) Contact map of Ca2+/CaM with the IQ domain of CaV2.3. IQ domain sequence in light gray rectangle. CaM residues within 4 Å of indicated IQ domain position are shown above (N-lobe) and below (C-lobe) IQ sequence. Listings for CaM include number of atoms within each residue that are within 4 Å of the indicated IQ position. Water-mediated hydrogen bonds shown by ‘o’ symbol. Bar graph at the bottom plots solvent accessible area for each IQ position. (B) Contact map for Ca2+/CaM with CaV2.1 IQ domain of. (C) Close hydrophobic interactions between select IQ domain residues and hydrophobic pockets of Ca2+/CaM, taken from CaV2.3 structure (Figure 1B). Left, upstream residues -5 and -6 (shown as stick diagrams) dock closely with N-lobe pocket (shown in space-filling representation). Right, those at positions 3 and 4 nestle tightly with C-lobe cavities. CaM is color-coded for electrostatic potential (gray, hydrophobic; red, electronegative). (D) Space-filling representation of CaV2.3 structure. Partial exposure of IQ domain (red) at carboxy-terminal end. Y[+4], stick figure; V[+12], colored in yellow.

Crystals for the analogous CaV2.1 structure manifested a C2 symmetry, where the asymmetric unit contained two CaM/IQ complexes (1 and 2), each with 1:1 stoichiometry. Both complexes adopted nearly indistinguishable conformations, though complex 1 yielded a somewhat more defined electron density map. Accordingly, all subsequent analysis refers to structure 1 (Figures 1C and 2B). The near identity of this CaV2.1 structure to its CaV2.3 counterpart is documented by the overlay in Figure 1D. Additionally, the detailed contact map (Figure 2B) confirmed a highly analogous interface between CaM and the IQ domain of CaV2.1, and the atomic positions were closely similar throughout (Table 1). The details of model refinement for both structures are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Cα-RMS deviations (Å2) for structures of Ca2+/CaM complexed with IQ domains of CaV2.3, CaV2.1, and CaV1.2

| CaV2.3 | CaV2.1a | CaV2.1b | CaV1.2* | CaV1.2# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaV2.3 | 0.93 | 0.70 | 0.99 | 2.51 | |

| CaV2.1a | 0.55 | 1.01 | 2.40 | ||

| CaV2.1b | 0.90 | 2.42 | |||

| CaV1.2* | 2.37 | ||||

| CaV1.2# |

The superscripts ‘a’ and ‘b’ denote structures 1 and 2 of the CaV2.1 complex, respectively.

C-form in 2BE6.pdb.

2F3Y.pdb.

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| CaV2.3 IQ/CaM | CaV2.1 IQ/CaM | |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal parameters | ||

| Space group | I4122 | C2 |

| Cell constants (Å) | 124.61, 124.61, 74.02 | 80.66, 80.43, 63.84 |

| Data collection | ||

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.54 | 1.54 |

| Resolution (Å) | 30-2.2 (2.28-2.2) | 50-2.6 (2.7-2.6) |

| Rsym | 0.089 (0.502) | 0.061 (0.35) |

| I/σI | 17.3 (1.8) | 6.9 (2.1) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.57 (92.7) | 92.39 (94.5) |

| Redundancy | 6.3 (5.1) | 1.6 (1.6) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 30-2.3 | 24.9-2.6 |

| No. reflections | 12496 | 12283 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 20.5/26.1 | 20.8/25.3 |

| No. atoms | ||

| Protein | 1291 | 2523 |

| Ligand/ion | 14 | 23 |

| Water | 138 | 53 |

| B-factors | ||

| Protein | 40.30 | 68.86 |

| Ligand/ion | 67.92 | 67.02 |

| Water | 46.87 | 70.32 |

| RMS deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.008 | 0.006 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.009 | 0.849 |

Highest resolution shell shown in parentheses.

Thus oriented to CaV2 structure, we searched for any structural differences relative to the analogous complex for CaV1.2 channels, ones that might rationalize the notable contrasts in CaM regulatory phenotype between these two channel classes. In this regard, no simple answers arose: the CaV2 structure is highly similar to the most common CaV1 form, but for the lack of an ~10° bend in the mid IQ segment of the CaV1 structure (Supplemental Data 1). This minor difference, in a largely buried peptide, seemed insufficient to explain appreciable functional differences. Also, the similarity of an extensive contact map for a published CaV1.2 complex (Van Petegem et al., 2005) (Supplemental Data 1), and statistical comparisons of atom positions (Table 1), underscored the overall structural similarities.

Systematic alanine scanning of the CaV2.1 IQ domain

To gain perspective on the contrast between structural similarity and functional divergence, we undertook alanine-scanning mutagenesis of the CaV2.1 IQ domain, and correlated mutations with CaM regulatory function as assayed by whole-cell electrophysiological recordings. Previous reports have described the effects of cluster mutations within the IQ domain (DeMaria et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2003), but these scans were far from exhaustive, and could well involve perturbations of main-chain conformation that complicate interpretation. By contrast, point alanine mutations probe side-chain effects, without perturbation of the backbone fold (Cunningham and Wells, 1989).

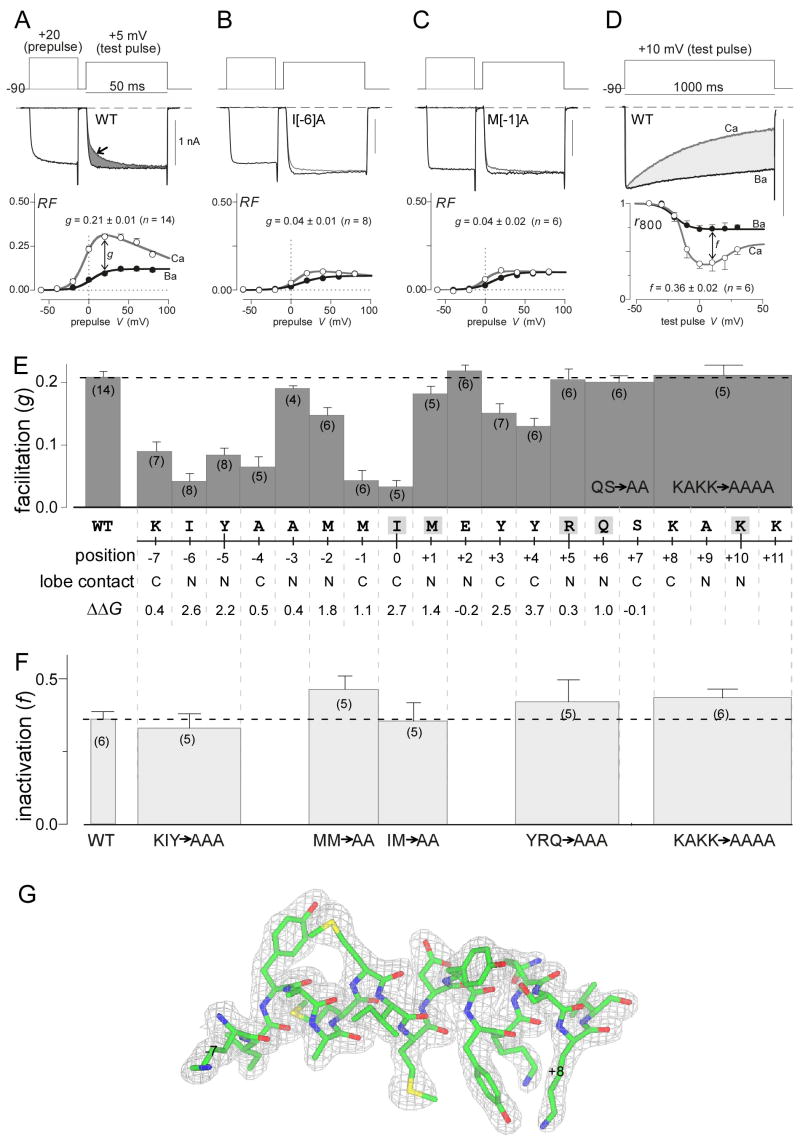

Figure 3A introduces a first form of CaM regulation in CaV2.1: Ca2+ binding to the C-lobe of CaM triggers a Ca2+-dependent facilitation (CDF) of current that accrues over tens of milliseconds, before appreciable CDI becomes apparent (Chaudhuri et al., 2005; Chaudhuri et al., 2007; DeMaria et al., 2001; Soong et al., 2002). With Ca2+ as charge carrier, CDF is readily detected as a slow phase of increasing Ca2+ current seen during short (50-ms) test depolarizations (top, gray trace, arrow). When channels are facilitated by Ca2+ entry during a preceding voltage prepulse, ensuing currents activate rapidly to the facilitated level during the test-pulse (top, black trace). To quantify the facilitation produced by the prepulse, we integrate the difference between normalized test-pulse currents in the absence and presence of a prepulse (ΔQ, gray shaded area), and this integral is used to determine the relative facilitation (RF) induced by the voltage prepulse. On average, RF demonstrates a bell-shaped dependence upon prepulse voltage (bottom, open circles), as expected for a genuine Ca2+-driven process (Brehm and Eckert, 1978). By contrast, fitting with the strong preference of CaM for Ca2+ over Ba2+ (Chao et al., 1984), there is little evidence of such prepulse facilitation with Ba2+ as charge carrier (bottom, filled circles). The small rise of RF seen with Ba2+ (~0.05, bottom, open circles) likely reflects background G-protein modulation (DeMaria et al., 2001). To index pure CDF, we consider the increase of the Ca2+ over Ba2+ RF relations (g ~0.2), following a 20-mV prepulse.

Figure 3. Functional alanine scan of CaV2.1 IQ domain.

(A) Baseline CDF for wild-type CaV2.1 channel. Top, exemplar Ca2+ current traces evoked by a test pulse, with (black) and without (gray) a voltage prepulse. Dark gray shading emphasizes the facilitation produced by Ca2+ entry during the prepulse. Bottom, population data for CDF. RF, relative facilitation produced by voltage prepulses to the potential shown on the abscissa. Open symbols, data with Ca2+ currents; filled symbols, data with Ba2+ currents. Difference between relations at +10 mV (g) quantifies pure CDF. Numbers in parentheses, number of cells in population data, here and throughout. (B, C) Elimination of CDF for corresponding I[−6]A (B) and M[−1]A (C) mutations. (D) Baseline CDI profile for wild-type CaV2.1 channel. Top, exemplar Ca2+ current (gray) and Ba2+ current (black), as evoked by 10-mV test pulse. Light gray shading emphasizes extent of CDI. Current scale bar pertains to Ca2+ current. Ba2+ current scaled down 2–3× to facilitate visual comparison of decay kinetics. Bottom, population data for CDI. r800 is the fraction of peak current remaining after 800-ms depolarization to the potential shown on the abscissa. Open symbols, for Ca2+ currents; filled symbols, for Ba2+ currents. Difference between relations at +10 mV (f) quantifies pure CDI. (E) CDF of CaV2.1 mutants, with changes to alanine as indicated. Bottom rows indicate predominate CaM lobe contact (C, N), and Robetta calculated disruption of binding energy upon mutation to alanine. (E) CDI of CaV2.1 mutants, with changes to alanine as indicated. (G) Electron density contour around CaV2.3 IQ domain from positions −7 to +9. Mesh encloses region where density exceeds background by two standard deviations, as generated by CCP4 mg.

Given this baseline, we examined the effects of alanine point mutations across the entire CaV2.1 IQ domain. To start, we recalled that a double alanine mutation in the central IQ domain residues IM→AA (positions 0–1) eliminated CDF in prior work (DeMaria et al., 2001). Dissecting this result into single point mutations (isoleucine at position zero mutated to an alanine (I[0]A); and methionine at position 1 changed to alanine (M[1]A)) indicates that the bulk of attenuation is attributable to the I[0] position (Figure 3E). Beyond this derivative result, the results of alanine scanning were unexpected (Figure 3E). Point mutations at any of the other canonical IQ domain residues (gray highlighted residues) had no appreciable effect on CDF. In fact, no more than minor effects were observed for any of the residues downstream of the initial I[0] at the beginning of the canonical motif; the strongest downstream effect was seen with Y[+3]A and Y[+4]A perturbations, which induced no more than 30–40% attenuation of function. The conventional concept for IQ domains predicts that the region downstream of I[0] would be functionally dominant (Bahler and Rhoads, 2002). By contrast, alanine point mutations at multiple upstream sites induced surprisingly large reductions in CDF; and this upstream trend was upheld for one of two naturally occurring alanines that were changed to threonines (Figure 3E, positions −4 and −3). In particular, CDF was nearly abolished with I[−6]A, A[−4]T, and M[−1]A mutations (Figures 3B, 3C, and 3E), all of these being upstream residues. These findings emphasized a surprising structure-function correlation for the Ca2+-CaM/IQ complex of CaV2 channels: IQ domain contacts at multiple residues upstream of I[0] were functionally dominant for C-lobe triggered regulatory function, compared with the canonical IQ motif residues, which include I[0] and selected downstream positions. This feature likely relates to the substantial structural contrasts between Ca2+-CaM/IQ and apoCaM/IQ complexes (Houdusse et al., 2006), for which the latter forms the basis of traditional IQ motif hotspots (Figure 3E, highlighted positions). The set of key upstream residues identified here may be emblematic of a new canonical IQ motif pertinent to Ca2+/CaM interactions. In this regard, the pattern of upstream dominance may well pertain to the CaV1 Ca2+-CaM/IQ complex in regard to C-lobe signaling (Fallon et al., 2005; Van Petegem et al., 2005).

We next turned to a second form of CaM regulation of CaV2.1 channels, as shown in Figure 3D. Ca2+ binding to the N-lobe of CaM triggers a Ca2+-dependent inactivation (CDI) that progresses over hundreds of milliseconds (Chaudhuri et al., 2005; Chaudhuri et al., 2007; DeMaria et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2003; Soong et al., 2002). This can be seen from the faster decay of Ca2+ versus Ba2+ currents (Figure 3D, top). Because the Ba2+ current decay reflects a separate form of voltage-dependent channel inactivation (Alseikhan et al., 2002; Jones et al., 1999; Patil et al., 1998), the additional speeding of decay seen in Ca2+ versus Ba2+ currents reflects pure CDI (shaded area). On average, inactivation can be thus quantified by plotting the fraction of peak current remaining after 800-msec depolarization to various voltages (r800, Figure 3D, bottom). The maximum difference between Ba2+ and Ca2+ relations, f800 = 0.36, quantifies average CDI. Whereas substitution of glutamate at IQ positions 0 and 1 does eliminate this CDI (DeMaria et al., 2001), more targeted alanine substitutions have left CDI unchanged, at least for the few residues where such alanine substitutions have thus far been made (DeMaria et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2003). Here, despite an exhaustive scan, none of the alanine cluster/point mutations throughout the IQ domain appreciably affected CDI (Figure 3F). This result was unexpected, given the anticipated centrality of the IQ domain for CaM/channel regulation.

Potential mechanisms of CaM/channel regulation implicated by Ca2+-CaM/IQ structures

The demonstrated similarity in Ca2+-CaM/IQ structure for CaV2 and CaV1 channels (Table 1; Supplemental Data 1), together with the functional outcomes of systematic alanine scanning of the CaV2.1 IQ region (Figure 3), offered new constraints for evaluating mechanisms of CaM/channel regulation. The simplest scenario for rationalizing the opposing regulatory polarities of C-lobe regulation in CaV2.1 and CaV1.2 channels would arise from clear distinctions in the Ca2+-CaM/IQ structures of CaV2.1 versus CaV1.2 channels. Our new structures (Figures 1 and 2) clearly exclude this scenario, at least for the conformation in our crystals. This exclusion allowed us to focus on two other broad classes of mechanisms.

Class 1

This mechanism postulates insignificant structural differences between CaV2.1 and CaV1.2 channels, when comparing either their apoCaM/IQ complexes, or their Ca2+-CaM/IQ assemblies. In this manner, the IQ domain itself would play no distinguishing role in specifying C-lobe signaling polarity. Instead, nearly identical Ca2+-induced conformational changes in the CaM/IQ structure would be decoded in different ways by other parts of these two channel types. An important corollary of this class is ‘context-independent IQ function,’ wherein substitution of the IQ domain from one channel subtype into another should not alter C-lobe signaling.

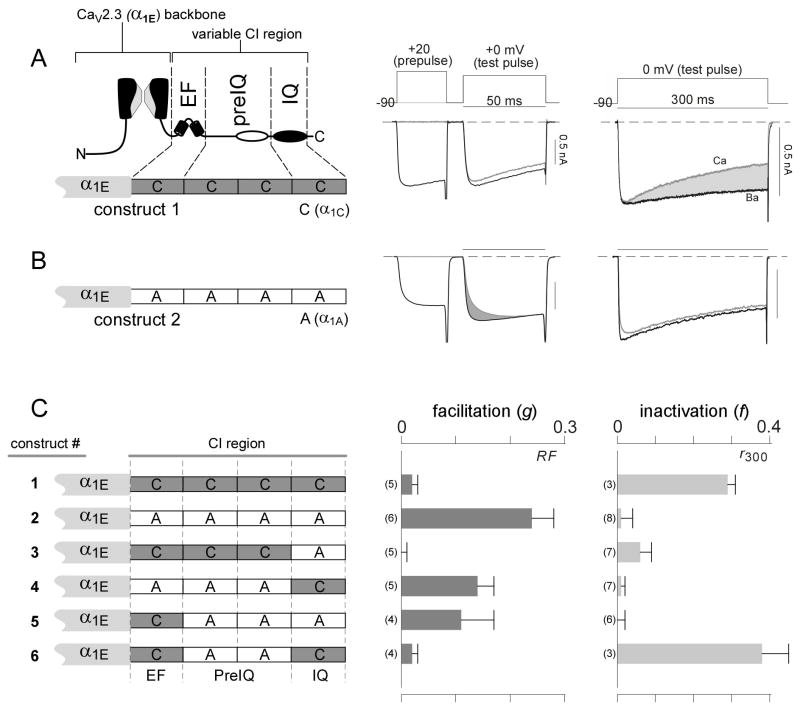

To test this prediction, we undertook the chimeric channel experiments displayed in Figure 4. CaV1.2 and CaV2.1 channels (with pore-forming subunits α1C and α1A, respectively) both manifest Ca2+ regulation triggered by Ca2+ binding to the C-lobe of CaM, but the regulatory polarity is CDI for CaV1.2, and CDF for CaV2.1. To examine the effects of targeted switching of IQ domains, we substituted the crucial proximal third of the carboxy terminus (Figure 1A, CI region) from either an α1C or α1A subunit onto a single, expression-permissive CaV2.3 channel backbone (Figure 4A, left, α1E). Direct swapping of CI regions between α1C and α1A subunits yielded nonfunctional channels (not shown), while CaV2.3 channels (α1E subunit backbone) do not exhibit intrinsic C-lobe CaM regulation (Liang et al., 2003). Hence, the CaV2.3 backbone furnished an appropriate and uniform context in which the regulatory effects of chimeric channel manipulations could be evaluated. Importantly, all recordings were performed in elevated Ca2+ buffering (5 mM EGTA) so as to isolate the C-lobe component of CaM regulation, and the electrophysiological protocols and analysis were analogous to those in Figures 3A and 3D.

Figure 4. Context-dependent IQ function.

(A) C-lobe regulation in chimeric channel with carboxy tail from CaV1.2 α1C subunit (construct 1). Left, cartoon of chimeric channel α1 subunit composition, with carboxytail landmarks as in Figure 1A. The ‘backbone’ of all chimeric α1 subunits, from the amino terminus through the beginning of the carboxy terminus, is derived from the CaV2.3 α1E subunit, here and throughout the figure. The proximal third of the carboxy tail from the CaV1.2 α1C subunit, spanning the EF-hand through the IQ domain, is fused to this backbone to create construct 1. Middle, exemplar Ca2+ traces showing absence of CDF (format as in Figure 3A). Right, exemplar Ca2+ and Ba2+ traces illustrating the presence of CDI (format as in Figure 3D). All experiments utilized high 5 mM EGTA Ca2+ buffering, to enrich for C-lobe mediated regulation throughout the figure. (B) C-lobe regulation in chimeric channels with carboxy tail from CaV2.1 α1A subunit (construct 2). CDF is present, but CDI is absent. (C) CDF and CDI population data, for constructs 1–6. Left, schematic showing composition of constructs. Middle, average CDF strength (g). Right average CDI strength (f). Metrics defined in Figures 3A and 3D. Context-dependent function of IQ domain shown by constructs 2 versus 3, and constructs 5 versus 6.

The experimental results clearly contradicted context-independent function of the IQ domain. For construct 1, with the carboxy tail from CaV1.2 channels, C-lobe signaling induced CDI (Figures 4A and 4C, top row), as for the parent CaV1.2 channel. Following the same linkage to the parental channel, construct 2 (carboxy tail from CaV2.1 channels) exhibited CDF (Figures 4B and 4C, row 2). Given this baseline, mechanistically informative results were obtained by selective exchange of IQ segments between constructs 1 and 2. Figure 4C (constructs 3 and 4) shows that this exchange did not preserve the C-lobe signaling present in the original constructs. Construct 3, which features insertion of the IQ segment of CaV2.1 into construct 1, failed to exhibit appreciable CDF or CDI. Construct 4, wherein the IQ segment from CaV1.2 has been introduced into construct 2, shows significantly weaker CDF than seen in construct 2. Yet stronger violation of context-independent IQ function came from two further constructs. Upon substituting the EF-hand domain from CaV1.2 into construct 2, the resulting construct 5 still exhibited CDF (Figure 4C, row 5), albeit weaker than in construct 2. However, after switching the CaV1.2 IQ domain into construct 5, the resulting construct 6 showed unmistakable CDI (Figure 4C, row 6). Thus, substitution of an IQ domain alone, as seen in the conversion from construct 5 into 6, switched regulatory polarity. Hence, class 1 cannot be true.

Class 2

This leads to a remaining possibility, wherein our CaV2 IQ/CaM structure might only be partially related to the conformation underlying functional CDF. Instead, the physiologically relevant conformation features some displacement of CaM to expose portions of the IQ domain for interaction with other regions, which in turn triggers channel regulation. In this scenario, the IQ domain would contribute in part to C-lobe signaling polarity, while interactions with other portions of the channel would also matter.

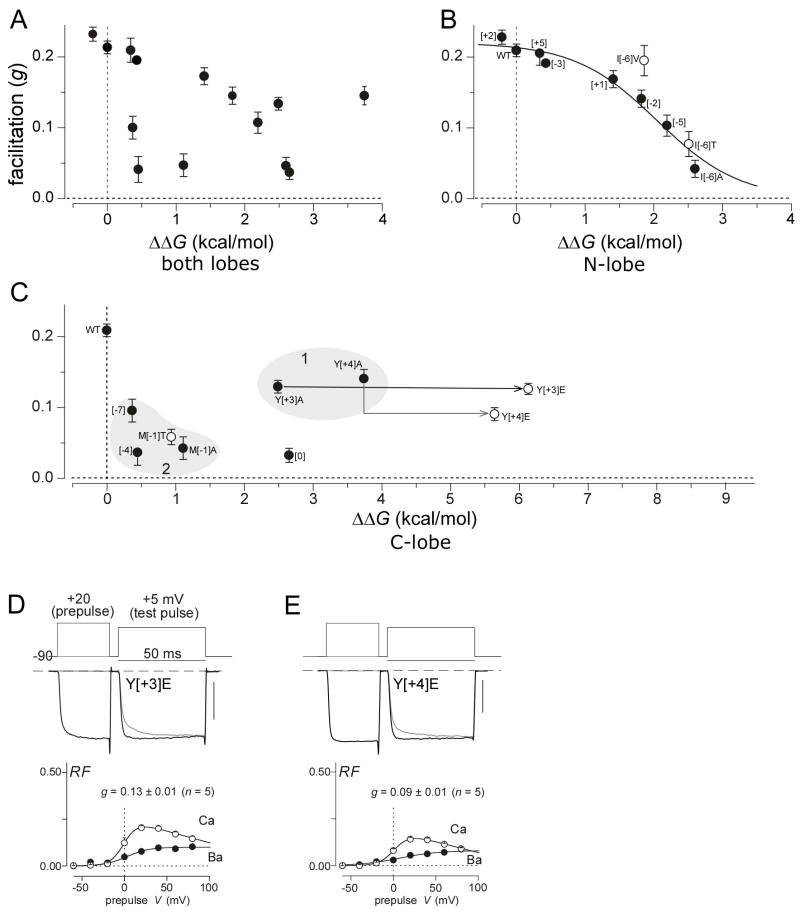

To investigate this hypothesis, we compared our CaV2 IQ/CaM structure (Figure 1) to the functional outcomes from alanine scanning mutagenesis (Figure 3) using Robetta, a molecular simulation package for ligand/receptor binding energy perturbation via single point mutations (Kortemme and Baker, 2002). These algorithms have successfully predicted these energies for multiple sets of experimentally determined structures and binding energies. Here, we utilized our CaV2.3 IQ/CaM structure as an input to Robetta, and the energetic effects of various point mutations to binding were then estimated. Importantly, a core assumption of this algorithm, that main chain conformation undergoes little perturbation by mutations, is consistent with prior structures showing that Ca2+/CaM in complex with a mutant CaV1.2 IQ domain is nearly indistinguishable from the wild-type configuration (Fallon et al., 2005). Figure 3E (bottom) displays the results of the CaV2.3 analysis as ΔΔG values, each denoting the estimated change in IQ/CaM binding energy for the indicated point mutation. All portions of the IQ segment subject to these energy calculations were characterized by well-defined electron densities, as demonstrated in Figure 3G (bottom). If the extent of IQ/CaM binding, as captured in our crystal structure (Figure 1B), were directly related to the strength of functional CDF, then plotting the strength of CDF (g) as a function of ΔΔG should define a 1:1 binding isotherm. Alternatively, if such binding were only indirectly related to function, such as in a hypothetical configuration featuring some Ca2+/CaM displacement towards another surrogate partner, an absence of correlation between these two variables might result. Figure 5A displays the results of this analysis, where each symbol relates to a single point mutation from Figure 3E. Initial examination would suggest no correlation. However, when the data were segregated according N- and C-lobe interfaces, a coherent pattern emerged. The plot for data relating to the N-lobe interface alone (Figure 5B) renders a clearly recognizable 1:1 binding curve, with half saturating binding energy ~2 kcal/mole. To further corroborate this relation, we introduced mutations other than alanine at a single position (I[−6]), where intimate CaM/IQ contact is prominent in CaV2 structure (Figure 2C). Reassuringly, these alternative mutations produced data that also resided close to the same binding curve (Figure 5B, open symbols). Hence, IQ domain binding to the N-lobe of CaM appears intimately related to functional CDF.

Figure 5. Comparing CDF function and predicted binding energy perturbation.

(A) Apparent absence of correlation between strength of CDF (ordinate) and predicted CaM/IQ binding perturbation by point mutations in IQ domain of CaV2 channels (abscissa). Filled symbols correspond to data from Figure 3E. (B) Strength of CDF correlates well with predicted binding energy perturbations, if analysis is restricted to IQ residues with N-lobe contacts. Filled symbols, N-lobe subset of data in panel A; open symbols, additional mutations at position −6. Solid curve plots 1:1 binding isotherm, with a half-binding energy value of ~2 kcal/mol. (C) Discordance of strength of CDF and predicted binding energy perturbations for C-lobe contacts. Filled symbols, C-lobe subset of data in panel A; open symbols, additional mutations at positions −1, +3, and +4. Locus 1, cases where energy calculations predict major disruption of CaM binding to IQ domain, yet CDF is largely preserved. Locus 2, cases where energy predictions suggest little perturbation of CaM binding to IQ domain, yet there is nearly complete elimination of CDF. (D) Y[+3]E mutant preserves CDF. (E) Y[+4]E mutant also spares CDF.

By contrast, the analogous plot for the C-lobe interface retained a disordered pattern (Figure 5C). In particular, two notable groups of discordance were present. First, Y[+3] and Y[+4] residues both anchor the C-lobe of CaM in our structure (Figure 2C), and corresponding Y[+3]A and Y[+4]A mutations are each predicted to markedly attenuate IQ/C-lobe binding (ΔΔG ~3 kcal/mole). Yet, the effect on CDF was minimal (Figure 5C, locus 1). Second, K[−7], A[−4]T, and M[−1] mutations should produce minimal perturbation of the IQ/C-lobe interface (locus 2, ΔΔG ~1 kcal/mole or less), yet extremely strong reductions of CDF were produced. More extreme forms of such divergence came from less conserved mutations at two of these key sites (Figure 5C, open symbols). For locus 1, both Y[+3]E and Y[+4]E mutants project an enormous ΔΔG ~6 kcal/mole, yet CDF is still largely maintained at the levels for alanine mutations (Figures 5C, 5D and 5E). For locus 2, the M[−1]T mutation should barely perturb IQ/C-lobe interaction, yet there is still marked diminution of CDF (Figures 5C).

These examples of C-lobe discordance suggest that the actual CDF configuration involves some displacement of the C-lobe away from the IQ domain (i.e., class 2), towards an alternate binding site that minimizes overall energetics. Nearby Ca2+/CaM binding sites, just upstream of the IQ domain, have been identified in CaV2.1 (Evans et al., 2004), and in CaV1.2 (Erickson et al., 2003a; Kim et al., 2004; Pate et al., 2000; Pitt et al., 2001; Romanin et al., 2000; Tang et al., 2003). Also, the presumed departure of the C-lobe from the IQ domain might be facilitated by heightened solvent accessibility of the IQ domain downstream of I[0] (Figure 2A, bottom; 2B, bottom; 2D), given that the C-lobe of CaM interacts to a somewhat greater degree with this downstream IQ region. Additionally, prior biochemical experiments demonstrate that cysteine substitution at position 0 of the CaV1.2 IQ domain yields Ca2+-CaM/IQ dimers linked by disulfide bonds (Kim et al., 2004). Finally, partial C-lobe departure from the IQ element would render CaM/IQ conformations distinguishable between CaV1.2 and CaV2.1 contexts; in particular, customized interaction of an exposed IQ surface with other channel domains explains both the divergence of C-lobe regulatory polarity between CaV1.2 and CaV2.1 channel subtypes, as well as the context-dependent functionality of the IQ domain in Figure 4. Cursory examination of Figure 4C might even suggest that it is complementation between EF and exposed IQ surfaces that specifies C-lobe polarity. However, the lack of CDF and CDI in an ‘ACCA’ chimeric channel (not shown) suggests that such IQ interactions might extend beyond the EF element alone. Previously reported data hint at potential extensions to the cytoplasmic loop between domains I and II of CaV1.2 channels (Kim et al., 2004). Overall, the weight of evidence, including our energy calculations of CaV2.1 point mutations, favors some C-lobe displacement from the IQ domain during channel regulation (class 2). A like scenario has been suggested for CaV1.2 (Fallon et al., 2005), but here we explored this proposal in greater depth.

DISCUSSION

We have solved the crystal structure for Ca2+/CaM in complex with the IQ domains from CaV2.3 and CaV2.1 channels. Both of these may be considered as equivalent to a generic CaV2 structure, which shares most of the hallmark features for previously resolved structures of Ca2+/CaM bound to the IQ domain of CaV1.2 channels. One surprising aspect of this structure arises by alanine scanning mutagenesis of the entire CaV2.1 IQ domain. For regulation by the C-lobe of CaM, IQ domain contacts upstream of the canonical IQ motif (IQxxxRGxxxR) are functionally dominant, while the downstream canonical contacts play a lesser role. This set of key upstream residues encompasses hydrophobic contacts at [−6], [−5] and [−1] positions. As these are not predicted by any known Ca2+/CaM binding motif (Rhoads and Friedberg, 1997), this set of contacts may comprise part of a new canonical IQ motif pertinent to Ca2+/CaM interactions (as opposed to the traditional motif for apoCaM (Rhoads and Friedberg, 1997)). Fitting with potential generalization, an IQ-domain data base indicates conservation of such hydrophobic residues (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2007). Another interesting feature concerns signaling triggered by Ca2+ binding to the N-lobe of CaM (Figure 3D). In this context, none of the IQ domain contacts appeared functionally consequential. A final key result is that only minor structural differences are present between the CaV2 and CaV1 IQ/CaM structures, and these in themselves seem insufficient to account for the substantial differences in C-lobe CaM-mediated regulation of these channels. Together, these results unambiguously exclude the simplest of prevailing hypotheses for channel regulation, wherein clear distinctions in the Ca2+-CaM/IQ structures of CaV2.1 versus CaV1.2 channels are primarily responsible for divergent regulatory effects. This exclusion now emphasizes more complex mechanisms, wherein multiple binding sites and structural determinants co-dominate in specifying CaM regulation of channels.

Specifically, by using molecular simulation (Robetta) to correspond our CaV2 structure with the functional outcomes of alanine scanning mutagenesis across the IQ domain of CaV2.1 (Kortemme and Baker, 2002), we favor a working proposal (class 2) in which the configuration in our CaV2 Ca2+-CaM/IQ structure may not fully capture the configuration underlying functional CDF. Instead, the C-lobe may partially dislodge from the IQ segment, enabling contacts between exposed IQ surfaces and other channel domains to trigger C-lobe mediated channel regulation. These alternative contacts may be customized to produce opposing C-lobe regulatory effects between CaV2.1 and CaV1.2 channels. Likewise, the absence of appropriate contacts may explain the lack of C-lobe mediated regulation in CaV2.2 and CaV2.3 channels (Liang et al., 2003). Importantly, this proposal rationalizes the overall sparing of C-lobe driven CDF by mutations at Y[+3] and Y[+4] positions (Figure 3E), despite intimate anchoring of these residues within a C-lobe cavity of the crystal structure (Figure 2C).

A remaining challenge for this class 2 proposal concerns the suggested importance of IQ contacts with the N-lobe in producing CDF (Figure 5B); this importance might initially appear to contradict previous results that Ca2+ binding only to the C-lobe of CaM is required to produce CDF (Chaudhuri et al., 2005; DeMaria et al., 2001). However, while our structure contains the Ca2+-bound N-lobe in complex with the IQ domain, the contacts and energetics for a Ca2+-free N-lobe interaction with the IQ element may be similar, and we would propose that either form of N-lobe/IQ binding supports CDF. Another form of Ca2+/CaM displacement could explain the uniform absence of IQ mutational effects on regulation triggered by Ca2+ binding to the N-lobe of CaM (Figures 3D and 3F). In particular, displacement of the N-lobe from the IQ domain, and subsequent binding to another site, could trigger the slower form of CaM modulation (CDI, Figure 3D), in a manner insensitive to IQ manipulation. Indeed, there is evidence that the Ca2+-bound N-lobe interacts with an amino-terminal channel locus to produce CDI in CaV1.3 and CaV1.2 channels (Dick et al., 2007), and we would propose that CaV2 channels contain a similar site elsewhere in the channel. Given this view, the slow induction of CDI would terminate CDF, because CDF appears reliant upon N-lobe/IQ interactions.

One other class of mechanism deserves consideration. There could be appreciable differences in the structures of apoCaM in complex with the IQ domains of CaV2.1 and CaV1.2 channels, while the analogous structures for Ca2+/CaM are very similar. This proposal readily explains differences in regulatory polarity, in terms of distinct apoCaM/IQ configurations for different channel types. Moreover, this scheme could partially explain the alanine scanning data for CaV2.1 (Figure 4C), as some discord between function and Ca2+/CaM binding to the IQ domain might reflect actual changes in apoCaM—IQ binding. However, live-cell FRET experiments between apoCaM and holochannels indicate a similar apoCaM/channel configuration in CaV1.2, CaV2.1, and CaV2.3 contexts (Erickson et al., 2001), at odds with this scenario. Though more direct data would be required to conclusively exclude this proposal, we favor class 2 mechanisms as more consistent with a comprehensive view of experimental constraints.

In all, our results emphasize that CaM/channel regulation likely reflects a multiplicity of binding configurations and structural determinants, likely extending beyond the IQ domain (Dunlap, 2007). Combined consideration of structure, alanine scanning, and molecular simulation hint at a scenario wherein Ca2+/CaM displaces from the IQ domain to facilitate further interactions triggering channel regulation. This provisional proposal forms an important framework for ongoing work. Future studies must peer beyond Ca2+/CaM in complex with the IQ domain, refine identification of additional effector sites, and resolve further related structures at the atomic level. In these structures, it may be necessary to simultaneously incorporate CaM with multiple sites, to fully capture the CaM/channel configurations most closely linked to modulation of channel gating. In this process, simple forms of molecular simulation (Baker, 2006) to correlate function with structure may continue to prove advantageous.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein purification and crystallization

Recombinant rat CaM (as cloned into pET24b, Novagen, EMD Chemicals, San Diego, CA) was expressed in E. coli BL-21(DE3), and purified to homogeneity by octyl-sepharose column chromatography (GE Healthcare Piscataway, NJ). The purified CaM was shown to be greater than 95% pure by SDS-PAGE. Synthetic peptides of the IQ domains for CaV2.1 and CaV2.3 channels were generated at the Synthesis and Sequencing Facility at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. To confirm molecular weights, these peptides were analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrophotometry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Mixtures of CaM (10 mg/ml) and each IQ-domain peptide (3 mg/ml) were incubated in a solution containing 20 mM MOPS-NaOH, 10 mM CaCl2, at pH 7.4. The mixture was then applied to a gel filtration column (Superdex 75 10/300, GE Healthcare), equilibrated with same buffer. A purified CaM/peptide complex was thus isolated, and subsequently crystallized using hanging drop vapor diffusion. Hanging drops were comprised of 1 μl of protein solution and 1 μl of a 1:2 dilution of reservoir buffer (described below) with water. Each drop was vapor equilibrated against 500 μl of undiluted reservoir buffer, and incubated at 18 °C. Further details of the crystallization conditions and related information for each type of complex are elaborated below.

CaV2.1 IQ-CaM complex—The purified complex of CaM and the IQ domain of CaV2.1 was further concentrated to 10 mg/ml, using a Centricon spin column (YM-3, Millipore, Bedford, MA). This concentrated complex was mixed into droplets as described above, with a reservoir buffer comprised of 2.3 M ammonium sulfate, 0.15 M sodium tartrate, and 0.05 M sodium-citrate (pH 5.5). Jagged, trapezoidal-shaped crystals appeared within four days, and achieved their full size in approximately two weeks. Diffraction quality crystals were grown by micro-seeding initial jagged crystals into freshly mixed droplets that had been pre-equilibrated for 3 hours. This produced single, rectangular-shaped crystals that grew in space group C2 and contained two CaM/IQ complexes in the asymmetric unit. The crystals used for x-ray diffraction analysis were soaked briefly in a fresh aliquot of reservoir buffer. The diffraction data were collected at room temperature, with crystals held in a wax-sealed glass capillary tube. The x-ray source was CuKα radiation produced by a Rigaku RU-200 generator (Tokyo, JAPAN).

CaV2.3 IQ-CaM complex—The purified complex of CaM and the IQ domain of CaV2.3 was concentrated to 10 mg/ml, mixed into droplets as above, and crystallized using a reservoir buffer containing 2.1 M ammonium sulfate, and 0.05 M sodium-citrate (pH 5.0). Pyramidal crystals appeared within two days, and achieved their full size in approximately 1 week. Crystals exhibited a I4122 space group, with one CaM/IQ complex within the asymmetric unit. The crystals used for diffraction analysis were soaked briefly in a cryoprotectant (20% glycerol in reservoir buffer), and flash frozen in a gaseous nitrogen stream at −180 °C. Diffraction data were then collected as above.

Analysis of x-ray diffraction data

Data were processed using HKL2000 (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). The C-lobe of CaM, taken from a previously solved structure of Ca2+/CaM in complex with the IQ domain of CaV1.2 channels (PDB ID code 2BE6 C-form), was used as the search model in a molecular replacement approach to solving the structure of Ca2+/CaM in complex with the IQ domain of CaV2.3. In this process, we used the program MOLREP (Vagin and Teplyakov, 1997) from the CCP4 program suite (Collaborative Computational Project, 1994). Structure refinement was accomplished with iterative rounds of model building and refinement, using COOT (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) and REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 1997) software packages, respectively. The structure for Ca2+/CaM in complex with the IQ domain of CaV2.1 was obtained in a similar manner, except that the search model was the newly solved structure for Ca2+/CaM in complex with the IQ domain of CaV2.3. In addition, the refinement also incorporated TLS algorithms, with TLS groups derived from TLSMD (Painter and Merritt, 2006). All data collection and model refinement statistics for both structures are summarized in Table 2. Molecular graphics were prepared with CCP4 mg software (Potterton et al., 2004). Total buried surface area was determined by the AREAIMOL program in the CCP4 suite (Lee and Richards, 1971), as applied to our CaV2.3 structure. Coordinates and structure factors will be deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (accession codes XXXX and YYYY for CaV2.1 and CaV2.3, respectively).

Transfection of human embryonic kidney 293 cells

Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells were transiently transfected (calcium phosphate protocol) and cultured in 6-cm plates, as described (Brody et al., 1997). For expression of recombinant calcium channels, we applied 4 μg of cDNA encoding the desired α1 subunit (CaV), along with 4 μg each of rat brain α2a (Perez-Reyes et al., 1992), rat brain α2δ subunits (Tomlinson et al., 1993), and finally 1 μg of the RSV T antigen. The α1A pore-forming subunit (CaV2.1) (Soong et al., 2002) was cloned from a human source (NM000718), and the CaV1.2 α1C subunit from rabbit (Wei et al., 1991) (X15539). All chimeric constructs were made from the carboxy tails of these two parental α1A and α1C channel subunits, as fused in various combinations onto the rat brain CaV2.3 α1E subunit (Soong et al., 1993) (NM019294), which served as a channel backbone (Figure 4).

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell current recordings were performed 1–3 days after transfection, using glass pipettes with resistances of 1.5–3 MΩ prior to series resistance compensation. For characterization of regulatory processes initiated by Ca2+ binding to the C-lobe of CaM (all Figures except 3D and 3F), which can occur when Ca2+ elevations are restricted to within tens of nanometers of the channel cytoplasmic pore, the internal solution contained a relative high concentration of Ca2+ buffer, with a specific composition containing: Cs-MeSO3, 135 mM; CsCl, 5 mM; EGTA, 5 mM; MgCl2, 1 mM; MgATP, 4 mM; and HEPES (pH 7.3), 10 mM; 290 mOsm, adjusted with glucose. To characterize N-lobe mediated channel regulation, which favors global Ca2+ elevations, the EGTA was reduced to 1 mM in the internal solution (Figures 3D and 3F, only). The bath solution contained: TEA-MeSO3, 140 mM; HEPES (pH 7.3), 10 mM; and CaCl2 or BaCl2, 5 mM; 300 mOsm, adjusted with glucose. Standard patch-clamp techniques were used with an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments/Molecular Devices, CA). Currents were filtered at 2 kHz and sampled at 10 kHz; series resistance was typically 1–2 MΩ after >70% compensation; and leaks and capacitive transients were subtracted by a P/8 protocol. Test pulse depolarizations were delivered every 30 s for local Ca2+ regulation protocols, and 60 s for global Ca2+ regulation protocols. Population data are presented as mean ± SEM, after analysis by custom-written software in MATLAB software (MathWorks, MA) and Microsoft Excel.

Construction of mutant and chimeric molecules

Single or cluster mutations in the IQ domain were generated using the QuikChange procedure (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), with the template being a small portion of the CaV2.1 α1A cDNA, which spanned the IQ domain. The mutant IQ domain was then cloned into a pristine α1A subunit in pcDNA3, via unique upstream BstE II and downstream Xba I restrictions sites, which flanked the IQ domain. For the chimeric channels in Figure 4, the caboxy tail of the CaV2.3 α1E subunit was replaced by the N-terminal third of the carboxy tail (containing EF-hand and IQ regions) derived from various combinations of CaV1.2 α1C and CaV2.3 E subunits. Thus, amino acids 1–1712 of the CaV2.3 α1E subunit served as a ‘backbone’ for all chimeric channels. For construct 1 (Figure 4C), PCR was used to amplify cDNA encoding amino acids 1513–1670 of the CaV1.2 α1C subunit, followed by a stop codon. This product was cloned into unique upstream Xho I and downstream Xba I sites of the CaV2.3 α1E subunit. The upstream Xho I site in the PCR product was introduced as a silent mutation at the upstream end of the PCR product. For construct 2 (Figure 4C), amino acids 1818–1982 of the CaV2.1α1A subunit was introduced into the CaV2.3 α1E subunit by the same strategy and restriction sites. For constructs 3–6 (Figure 4C), overlap extension PCR (Ho et al., 1989) was used to generate the various carboxy tail inserts, which were introduced into the CaV2.3 α1E subunit by the same strategy and restriction sites. The detailed amino acid composition of constructs 1–6 are presented in Supplemental Data 2. Throughout, all portions of constructs subject to PCR or QuickChange were confirmed in their entirety by sequencing.

Energy calculations for point mutations

The web-based computational algorithm Robetta (http://www.robetta.org/alascansubmit.jsp) was used to predict the change in ligand-receptor (i.e., IQ domain and Ca2+/CaM) binding energy produced by point mutation of interface residues (Kortemme et al., 2004). These algorithms accommodate changes not only to alanine, but also to other amino acids (e.g., Figure 5, M[7minus;1]T and Y[+4]E). For mutations to alanine, the default operational mode of the algorithm was used. For mutations from alanine to non-alanine residues (A→X), we modified the target residue in the submitted structure file, so as to rename the target residue as ‘X’ and delete all side-chain atoms. This change triggered the computational algorithm to build in the missing atoms for the desired mutant residue (X), and then optimize rotomer conformation. The calculated ΔΔG(X→A) then corresponded to an X→A mutation. The energy for the desired A→X mutation is then determined as ΔΔG(A→X) = −ΔΔ G(X→A). For Y→X mutations, where neither X nor Y is alanine, a concatenation of the former manipulations was used. Specifically, ΔΔG (Y→X) = ΔΔG(Y→A) + ΔΔG(A→X). Calculations were generated based on our structure of Ca2+/CaM in complex with the IQ domain of CaV2.3, rather than for the CaV2.1 analog, owing to the advantages of the higher resolution in the former structure (2.1 Å versus 2.6 Å).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wanjun Yang for dedicated technical support; Mark Mayer and Samuel Bouyain for advice on crystallization; Lai Hock Tay for introducing the potential use of Robetta; David Masica, Jeffrey Gray, and Tanja Kortemme for advice on the use of Robetta; and Michael Tadross and Henry Colecraft for insightful comments and discussion. This work was supported by RO1MH065531 from the NIMH (to D.T.Y.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbott LF, Regehr WG. Synaptic computation. Nature. 2004;431:796–803. doi: 10.1038/nature03010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alseikhan BA, DeMaria CD, Colecraft HM, Yue DT. Engineered calmodulins reveal the unexpected eminence of Ca2+ channel inactivation in controlling heart excitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17185–17190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262372999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahler M, Rhoads A. Calmodulin signaling via the IQ motif. FEBS Lett. 2002;513:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. Prediction and design of macromolecular structures and interactions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361:459–463. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DJ, Leonard J, Persechini A. Biphasic Ca2+-dependent switching in a calmodulin-IQ domain complex. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6987–6995. doi: 10.1021/bi052533w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JG, Sakmann B. Facilitation of presynaptic calcium currents in the rat brainstem. J Physiol (Lond) 1998;513:149–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.149by.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm P, Eckert R. Calcium entry leads to inactivation of calcium channel in Paramecium. Science. 1978;202:1203–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.103199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody DL, Patil PG, Mulle JG, Snutch TP, Yue DT. Bursts of action potential waveforms relieve G-protein inhibition of recombinant P/Q-type Ca2+ channels in HEK 293 cells. JPhysiol (Lond) 1997;499:637–644. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao SH, Suzuki Y, Zysk JR, Cheung WY. Activation of calmodulin by various metal cations as a function of ionic radius. Mol Pharmacol. 1984;26:75–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri D, Alseikhan BA, Chang SY, Soong TW, Yue DT. Developmental activation of calmodulin-dependent facilitation of cerebellar P-type Ca2+ current. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8282–8294. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2253-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri D, Chang SY, DeMaria CD, Alvania RS, Soong TW, Yue DT. Alternative splicing as a molecular switch for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent facilitation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6334–6342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1712-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri D, Issa JB, Yue DT. Elementary Mechanisms Producing Facilitation of Cav2.1 (P/Q-type) Channels. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129:385–401. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project N. CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham BC, Wells JA. High-resolution epitope mapping of hGH-receptor interactions by alanine-scanning mutagenesis. Science. 1989;244:1081–1085. doi: 10.1126/science.2471267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuttle MF, Tsujimoto T, Forsythe ID, Takahashi T. Facilitation of the presynaptic calcium current at an auditory synapse in rat brainstem. J Physiol (Lond) 1998;512:723–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.723bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leon M, Wang Y, Jones L, Perez-Reyes E, Wei X, Soong TW, Snutch TP, Yue DT. Essential Ca(2+)-binding motif for Ca(2+)-sensitive inactivation of L-type Ca2+ channels. Science. 1995;270:1502–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaria CD, Soong TW, Alseikhan BA, Alvania RS, Yue DT. Calmodulin bifurcates the local Ca2+ signal that modulates P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. Nature. 2001;411:484–489. doi: 10.1038/35078091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick IE, Tadross MR, Liang H, Tay LH, Yang W, Yue DT. An N-terminal calmodulin-binding module transforms the global/local Ca2+ selectivity of CaM/CaV channel regulation (abstr.) Biophys J. 2007;(Supplement 20a):99a. [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch R. Excitation-transcription coupling: signaling by ion channels to the nucleus. Sci STKE 2003. 2003:PE4. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.166.pe4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap K. Calcium channels are models of self-control. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129:379–383. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap K, Luebke JI, Turner TJ. Exocytotic Ca2+ channels in mammalian central neurons. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson MG, Alseikhan BA, Peterson BZ, Yue DT. Preassociation of calmodulin with voltage-gated Ca(2+) channels revealed by FRET in single living cells. Neuron. 2001;31:973–985. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00438-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson MG, Liang H, Mori MX, Yue DT. FRET two-hybrid mapping reveals function and location of L-type Ca2+ channel CaM preassociation. Neuron. 2003a;39:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson MG, Moon DL, Yue DT. DsRed as a potential FRET partner with CFP and GFP. Biophys J. 2003b doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74504-4. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J, Tay LH, Mori MX, Anderson MJ, Erickson MG, Yue DT. FRET two-hybrid analysis reveals differences in the interaction of calmodulin with CaV1.2 (L-) versus CaV2.1 (P/Q-type) Ca channels (abstr.) Biophys J. 2004;86:275a. [Google Scholar]

- Evans RM, Zamponi GW. Presynaptic Ca2+ channels--integration centers for neuronal signaling pathways. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:617–624. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon JL, Halling DB, Hamilton SL, Quiocho FA. Structure of calmodulin bound to the hydrophobic IQ domain of the cardiac Ca(v)1.2 calcium channel. Structure. 2005;13:1881–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho S, Hunt H, Horton R, Pullen J, Pease L. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeflich KP, Ikura M. Calmodulin in action: diversity in target recognition and activation mechanisms. Cell. 2002;108:739–742. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdusse A, Gaucher JF, Krementsova E, Mui S, Trybus KM, Cohen C. Crystal structure of apo-calmodulin bound to the first two IQ motifs of myosin V reveals essential recognition features. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19326–19331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609436103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LP, DeMaria CD, Yue DT. N-type calcium channel inactivation probed by gating-current analysis. Biophys J. 1999;76:2530–2552. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77407-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurado LA, Chockalingam PS, Jarrett HW. Apocalmodulin. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:661–682. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Ghosh S, Nunziato DA, Pitt GS. Identification of the components controlling inactivation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Neuron. 2004;41:745–754. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortemme T, Baker D. A simple physical model for binding energy hot spots in protein-protein complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14116–14121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202485799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortemme T, Kim DE, Baker D. Computational alanine scanning of protein-protein interfaces. Sci STKE 2004. 2004:pl2. doi: 10.1126/stke.2192004pl2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Zhou H, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent regulation of Ca(v)2.1 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:16059–16064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Richards FM. The interpretation of protein structures: estimation of static accessibility. J Mol Biol. 1971;55:379–400. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, DeMaria CD, Erickson MG, Mori MX, Alseikhan BA, Yue DT. Unified mechanisms of Ca2+ regulation across the Ca2+ channel family. Neuron. 2003;39:951–960. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00560-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hao L, He S, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD, et al. CDD: a conserved domain database for interactive domain family analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D237–240. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori MX, Erickson MG, Yue DT. Functional stoichiometry and local enrichment of calmodulin interacting with Ca2+ channels. Science. 2004;304:432–435. doi: 10.1126/science.1093490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa M, Tokumitsu H, Swindells MB, Kurihara H, Orita M, Shibanuma T, Furuya T, Ikura M. A novel target recognition revealed by calmodulin in complex with Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:819–824. doi: 10.1038/12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Meth Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:439–450. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate P, Mochca-Morales J, Wu Y, Zhang JZ, Rodney GG, Serysheva II, Williams BY, Anderson ME, Hamilton SL. Determinants for calmodulin binding on voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39786–39792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007158200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil PG, Brody DL, Yue DT. Preferential closed-state inactivation of neuronal calcium channels. Neuron. 1998;20:1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E, Castellano A, Kim HS, Bertrand P, Baggstrom E, Lacerda AE, Wei XY, Birnbaumer L. Cloning and expression of a cardiac/brain beta subunit of the L- type calcium channel. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1792–1797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BZ, DeMaria CD, Adelman JP, Yue DT. Calmodulin is the Ca2+ sensor for Ca2+-dependent inactivation of L- type calcium channels. Neuron. 1999;22:549–558. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BZ, Lee JS, Mulle JG, Wang Y, DeLeon M, Yue DT. Critical determinants of Ca2+-dependent inactivation within an EF-hand motif of L-type Ca2+ channels. Biophysical Journal. 2000;78:1906–1920. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76739-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt GS, Zuhlke RD, Hudmon A, Schulman H, Reuter H, Tsien RW. Molecular basis of calmodulin tethering and Ca2+-dependent inactivation of L-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30794–30802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potterton L, McNicholas S, Krissinel E, Gruber J, Cowtan K, Emsley P, Murshudov GN, Cohen S, Perrakis A, Noble M. Developments in the CCP4 molecular-graphics project. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2288–2294. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads AR, Friedberg F. Sequence motifs for calmodulin recognition. FASEB J. 1997;11:331–340. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.5.9141499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanin C, Gamsjaeger R, Kahr H, Schaufler D, Carlson O, Abernethy DR, Soldatov NM. Ca2+ sensors of L-type Ca2+ channel. FEBS Lett. 2000;487:301–306. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02361-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soong TW, DeMaria CD, Alvania RS, Zweifel LS, Liang MC, Mittman S, Agnew WS, Yue DT. Systematic identification of splice variants in human P/Q-type channel alpha1(2.1) subunits: implications for current density and Ca2+-dependent inactivation. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10142–10152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10142.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soong TW, Stea A, Hodson CD, Dubel SJ, Vincent SR, Snutch TP. Structure and functional expression of a member of the low voltage-activated calcium channel family. Science. 1993;260:1133–1136. doi: 10.1126/science.8388125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Halling DB, Black DJ, Pate P, Zhang JZ, Pedersen S, Altschuld RA, Hamilton SL. Apocalmodulin and Ca2+ calmodulin-binding sites on the CaV1.2 channel. Biophys J. 2003;85:1538–1547. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74586-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson WJ, Stea A, Bourinet E, Charnet P, Nargeot J, Snutch TP. Functional properties of a neuronal class C L-type calcium channel. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1117–1126. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90006-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsodyks MV, Markram H. The neural code between neocortical pyramidal neurons depends on neurotransmitter release probability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA. 1997;94:719–723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an Automated Program for Molecular Replacement. J Appl Cryst. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Van Petegem F, Chatelain FC, Minor DL., Jr Insights into voltage-gated calcium channel regulation from the structure of the CaV1.2 IQ domain-Ca2+/calmodulin complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:1108–1115. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei XY, Perez-Reyes E, Lacerda AE, Schuster G, Brown AM, Birnbaumer L. Heterologous regulation of the cardiac Ca2+ channel alpha 1 subunit by skeletal muscle beta and gamma subunits. Implications for the structure of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21943–21947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DB, Randall A, Tsien RW. Roles of N-type and Q-type Ca2+ channels in supporting hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science. 1994;264:107–111. doi: 10.1126/science.7832825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykes RC, Bauer CS, Khan SU, Weiss JL, Seward EP. Differential regulation of endogenous N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channel inactivation by Ca2+/calmodulin impacts on their ability to support exocytosis in chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5236–5248. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3545-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Wu LG. The decrease in the presynaptic calcium current is a major cause of short-term depression at a calyx-type synapse. Neuron. 2005;46:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang PS. abstract on one cam. Biophys J 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Yang PS, Alseikhan BA, Hiel H, Grant L, Mori MX, Yang W, Fuchs PA, Yue DT. Switching of Ca2+-dependent inactivation of Ca(v)1.3 channels by calcium binding proteins of auditory hair cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10677–10689. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3236-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuhlke RD, Pitt GS, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW, Reuter H. Calmodulin supports both inactivation and facilitation of L-type calcium channels. Nature. 1999;399:159–162. doi: 10.1038/20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuhlke RD, Reuter H. Ca2+-sensitive inactivation of L-type Ca2+ channels depends on multiple cytoplasmic amino acid sequences of the α1c subunit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA. 1998;95:3287–3294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.