Abstract

Individuals with hemophilia A require frequent infusion of preparations of coagulation factor VIII. The activity of factor VIII (FVIII) as a cofactor for factor IXa in the coagulation cascade is limited by its instability after activation by thrombin. Activation of FVIII occurs through proteolytic cleavage and generates an unstable FVIII heterotrimer that is subject to rapid dissociation of its subunits. In addition, further proteolytic cleavage by thrombin, factor Xa, factor IXa, and activated protein C can lead to inactivation. We have engineered and characterized a FVIII protein, IR8, that has enhanced in vitro stability of FVIII activity due to resistance to subunit dissociation and proteolytic inactivation. FVIII was genetically engineered by deletion of residues 794-1689 so that the A2 domain is covalently attached to the light chain. Missense mutations at thrombin and activated protein C inactivation cleavage sites provided resistance to proteolysis, resulting in a single-chain protein that has maximal activity after a single cleavage after arginine-372. The specific activity of partially purified protein produced in transfected COS-1 monkey cells was 5-fold higher than wild-type (WT) FVIII. Whereas WT FVIII was inactivated by thrombin after 10 min in vitro, IR8 still retained 38% of peak activity after 4 hr. Whereas binding of IR8 to von Willebrand factor (vWF) was reduced 10-fold compared with WT FVIII, in the presence of an anti-light chain antibody, ESH8, binding of IR8 to vWF increased 5-fold. These results demonstrate that residues 1690–2332 of FVIII are sufficient to support high-affinity vWF binding. Whereas ESH8 inhibited WT factor VIII activity, IR8 retained its activity in the presence of ESH8. We propose that resistance to A2 subunit dissociation abrogates inhibition by the ESH8 antibody. The stable FVIIIa described here provides the opportunity to study the activated form of this critical coagulation factor and demonstrates that proteins can be improved by rationale design through genetic engineering technology.

Hemophilia A results from the quantitative or qualitative deficiency of coagulation factor VIII (FVIII), necessitating exogenous replacement by either plasma- or recombinant-derived FVIII preparations. FVIII has a domain organization of A1-A2-B-A3-C1-C2 and is synthesized as a 2,351-aa single-chain glycoprotein of 280 kDa from which a signal peptide is cleaved upon translocation into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (1–3). Whereas the A and C domains exhibit 35–40% amino acid identity to each other and to the A and C domains of coagulation factor V, the B domain is not homologous to any known protein. Intracellular proteolytic processing within the B domain after residue Arg-1648 generates an 80-kDa light chain (domains A3-C1-C2) and a heterogeneous-sized heavy chain of 90–200 kDa (domains A1-A2-B). The heavy and light chains are associated as a heterodimer through a divalent metal-ion-dependent linkage between the A1 and A3 domains.

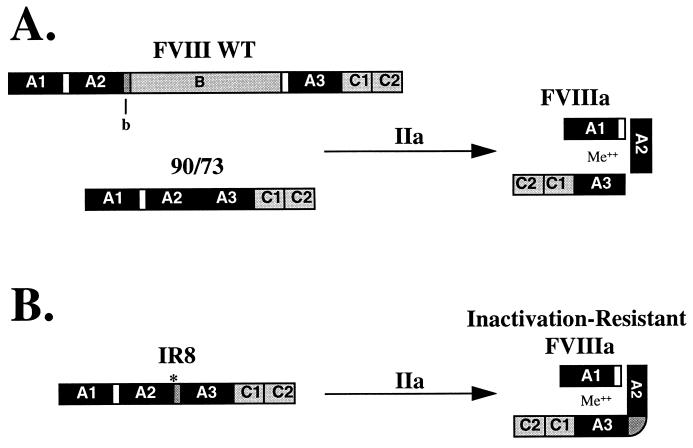

In plasma, FVIII circulates in an inactive form bound to von Willebrand factor (vWF) through noncovalent interactions and requires proteolytic cleavage by thrombin or factor Xa for activation (4–8). Upon proteolytic cleavage by thrombin, activated FVIII (FVIIIa) is released from vWF and functions to increase the Vmax of factor IXa proteolytic activation of factor X by at least 4 orders of magnitude in the presence of phospholipid and calcium (9, 10). Thrombin cleavage after Arg residues 372, 740, and 1689 activates FVIII coagulant activity, and this coincides with generation of a FVIIIa heterotrimer consisting of the A1 subunit in a divalent-metal-ion-dependent association with the thrombin-cleaved A3-C1-C2 light chain and a free A2 subunit associated with the A1 domain through an ionic interaction (Fig. 1A) (4, 11–13). This FVIIIa heterotrimer is unstable and subject to rapid inactivation through dissociation of the A2 subunit under physiological conditions (14).

Figure 1.

Structural domains of FVIII WT, B domain-deleted and inactivation-resistant FVIII (IR8). (A) A schematic representation of FVIII WT and B domain-deleted FVIII (90/73) domain structure and their predicted FVIIIa heterotrimeric subunit structure after thrombin activation (IIa). (B) A similar representation of IR8 and its predicted heterodimeric subunit structure after thrombin activation. Me++ indicates a divalent metal ion necessary for heavy and light chain association. ∗, indicates the missense mutation at residue 740 predicting resistance to thrombin cleavage. b indicates the 54 amino acids of B domain retained in the IR8 construct. White boxes represent the acidic regions at the A1-A2 and the B-A3 junctions.

Previous studies demonstrated that cleavages after Arg-372 and Arg-1689 are the most critical for efficient functional activation, whereas cleavage after Arg-740 was not required (13, 15–18). Cleavage after Arg-1689 removes an acidic amino acid-rich region from Arg-1648 to Arg-1689, and is necessary for dissociation of FVIIIa from vWF and makes FVIIIa available for interaction with phospholipids (4, 19–21). Cleavage after residue Arg-740 releases the heavily glycosylated B domain. Previous studies demonstrated that the B domain of FVIII is dispensable for FVIII cofactor activity (22–24). Genetically engineered FVIII molecules that have varying degrees of B domain deletion yield functional FVIII molecules that are more efficiently expressed in mammalian cells (22, 23, 25, 26). These deletion molecules exhibit typical thrombin activation that correlates with cleavage after Arg-372, Arg-740, and Arg-1689, generating a FVIIIa heterotrimer that is indistinguishable from wild-type FVIII (FVIII WT) and also is subject to rapid inactivation though dissociation of the A2 domain subunit.

With the greater understanding of the structural requirements for FVIII cleavage and activation, we have designed a functional B domain deletion FVIII that is not susceptible to rapid dissociation of the A2 domain subunit. We tested the hypothesis that fusion of the A2 subunit with the A3-C1-C2 light chain would yield a molecule in which only a single cleavage after Arg-372 would be necessary for functional activation. Under this hypothesis, the resultant FVIIIa molecule would not be susceptible to A2 subunit dissociation because the A2 subunit would be covalently attached to the light chain. We have generated such a molecule, inactivation-resistant factor VIII (IR8), which is resistant to spontaneous inactivation and exhibits a higher specific activity than FVIII WT. The results demonstrate the importance of A2 subunit dissociation in limiting the activity of FVIIIa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Anti-heavy chain factor VIII mAb (F-8), F-8 conjugated to CL-4B Sepharose, and purified recombinant factor VIII protein were a gift from Debra Pittman (Genetics Institute, Cambridge, MA). Anti-human vWF horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit antibody was purchased from Dako. Anti-light chain factor VIII mAbs, ESH-4 and ESH-8, were purchased from American Diagnostica (Greenwich, CT). Factor VIII-deficient and normal pooled human plasma were obtained from George King Biomedical (Overland Park, KS). Activated partial thromboplastin (Automated APTT reagent) and CaCl2 were purchased from General Diagnostics Organon Teknika (Durham, NC). Human thrombin and aprotinin were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim. [35S]methionine (>1,000 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Amersham. En3Hance was purchased from DuPont. Fetal bovine serum was purchased from PAA Laboratories (Newport Beach, CA). DMEM, methionine-free DMEM, OptiMEM, biotin N-hydroxy succinimide ester, and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate were purchased from GIBCO/BRL. O-phenylendiamine dihydrochloride was purchased from Sigma.

Plasmid Mutagenesis.

Mutagenesis was performed within the mammalian expression vector pMT2 (27) containing the FVIII cDNA (pMT2VIII). Mutant plasmids were generated through oligonucleotide site-directed mutagenesis by using the PCR as described (28). The plasmid designated 90/80 is FVIII WT cDNA sequence in which the B domain was deleted (del741–1648) and was described previously (29). The plasmid designated 90/73 is FVIII WT cDNA sequence in which the B domain and the acidic region of the light chain have been deleted (del741–1689) and was described previously (20).

Construction 1 (90/73 R740K).

Vector pMT290/73 was used as the DNA template. Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis was used to create a KpnI–ApaI PCR fragment in which codon 740 was mutated from AGA to AAA, predicting an amino acid substitution of lysine for arginine, and was ligated into KpnI–ApaI-digested pMT290/73.

Construction 2 (90/b/73 R740K).

Vector pMT2VIII was used as the DNA template. Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis was used to create a KpnI/b/MluI PCR fragment (where b represents DNA sequence encoding for amino acid residues 741–793 of the WT sequence followed by an MluI site predicting amino acids threonine and arginine at residues 794 and 795/1689), which was ligated into the KpnI–MluI-digested vector pMT2VIII/1689MluI. Vector pMT2VIII/1689MluI was generated by the heteroduplex procedure to introduce an MluI site at residue 1689 to facilitate cloning as described previously (30).

Construction 3 (90/b/73 R740A).

Vector 90/b/73 R740K was used as the DNA template. Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis was used to create a KpnI/b/ApaI fragment in which codon 740 was mutated from AAA to GCA, predicting an amino acid substitution of alanine for lysine, which was ligated into KpnI–ApaI-digested pMT290/73.

Construction 4 (90/b/73 R336I/R740A).

Vector PMT2VIII/R336I was digested with SpeI and KpnI. The fragment was ligated into SpeI–KpnI-digested 90/b/73 R740A.

Construction of IR8 (90/b/73 R336I/R562K/R740A).

Vector PMT2VIII/R562K was digested with BglII and KpnI. The fragment was ligated into BglII–KpnI-digested 90/b/73 R336I/R740A. The plasmid containing the WT FVIII cDNA sequence was designated FVIII WT. All plasmids were purified by centrifugation through cesium chloride and characterized by restriction endonuclease digestion and DNA sequence analysis.

DNA Transfection and Analysis.

Plasmid DNA was transfected into COS-1 cells by the DEAE-dextran method as described (31). Conditioned medium was harvested at 64 hr posttransfection in the presence of 10% fetal bovine serum. FVIII activity was measured by one-stage APTT clotting assay on a Medical Laboratory Automation Electra 750 (Pleasantville, NY). Protein synthesis and secretion were analyzed by metabolically labeling cells at 64 hr posttransfection for 30 min with [35S]methionine (300 μCi/ml in methionine-free medium), followed by a chase for 4 hr in medium containing 100-fold excess unlabeled methionine and 0.02% aprotinin. Cell extracts and conditioned medium were harvested, and immunoprecipitations were performed and analyzed as described (31).

Protein Purification.

Partially purified IR8 protein was obtained from 200 ml of conditioned medium from transiently transfected COS-1 cells by immunoaffinity chromatography (32), yielding 300–1,500 ng per purification. FVIII WT protein was purified in parallel from stably transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells. The proteins eluted into the ethylene glycol-containing buffer were dialyzed and concentrated against a polyethylene glycol (Mr ≈15–20,000)-containing buffer (14) and stored at −70°C.

FVIII Activity and Antigen Assay.

FVIII activity was measured in a one-stage APTT clotting assay by reconstitution of human FVIII-deficient plasma. For thrombin activation, protein samples were diluted into 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl/2.5 mM CaCl2/5% glycerol and incubated at room temperature with 1 unit/ml of thrombin. After incubation for increasing periods of time, aliquots were diluted and assayed for FVIII activity. One unit of FVIII activity is the amount measured in 1 ml of normal human pooled plasma. FVIII antigen was quantified using a sandwich ELISA method using anti-light chain antibodies ESH-4 and ESH-8 (33). Recombinant factor VIII protein purified in parallel was used as a standard.

FVIII-vWF Complex ELISA.

Immulon 2 microtiter wells (Dynatech) were coated with F-8 antibody at a concentration of 2 μg/ml overnight at 4°C in a buffer of 0.05 M sodium carbonate/bicarbonate, pH 9.6. Wells were washed with TBST (50 mM Tris⋅HCl,pH 7.6/150 mM NaCl/0.05% Tween 20) then blocked with 3% BSA in TBST. Protein samples were diluted in TBST, 3% BSA, 1% factor VIII-deficient human plasma +/− ESH8 (molar ratio of ESH8/FVIII protein = 2:1). Samples were incubated for 2 hr at 37°C in 1.7-ml microfuge tubes and then incubated for an additional 2 hr in the blocked and washed microtiter wells. FVIII/vWF complexes were detected as described (34).

RESULTS

Generation of Inactivation Resistant FVIII.

Variable deletions between residues 740 and 1648 within FVIII yield molecules with WT activity that generate a heterotrimer after cleavage by thrombin (26, 30, 35). Further deletion of the acidic region in the light chain (740–1689, termed 90/73) also yielded a functional molecule that generated a heterotrimer after thrombin cleavage; however, this molecule had a significantly reduced affinity for vWF (20). We tested the requirement for cleavage at the 740/1689 junction within the 90/73 deletion molecule by site-directed mutagenesis to change the Arg-740/1689 to Lys. Thrombin treatment of the resultant secreted molecule generated a heterodimer due to a single cleavage after Arg-372. This molecule would be resistant to dissociation of the A2 subunit, because it was fused to the light chain. However, the resultant molecule was not active in the one-stage APTT clotting assay either before or after thrombin cleavage. We hypothesized that a conformational constraint of the A2 domain may prevent activity of the 90/73 molecule having the A2 domain juxtaposed to the A3 domain. We therefore introduced a “spacer” of B domain (b) consisting of the amino acid residues 741–793 of the WT sequence followed by an MluI site (for cloning purposes), predicting amino acids Thr and Arg at residues 794 and 795/1689. This construct 90/b/73 is similar to a previously characterized B domain deletion FVIII (FVIII-LA) that is efficiently secreted and susceptible to thrombin cleavage and activation (26). The A2-b junction then was mutated from Arg to Lys or Ala at residue 740 to prevent thrombin cleavage at this site (Fig. 1B). Thus, upon incubation with thrombin, cleavage should occur only after Arg-372 to generate a FVIIIa heterodimer.

Both thrombin and factor Xa can cleave after Arg-336 and inactivate FVIII by loss of the acidic region at the carboxy terminus of the A1 domain. This acidic region may be important for interaction with the A2 subunit (36). To prevent cleavage and loss of the acidic region, Arg-336 was mutated to Ile because this amino acid change previously was shown to abrogate cleavage (14). Finally, activated protein C can inactivate FVIIIa by proteolytic cleavage after Arg-336 and Arg-562 (37). Cleavage at either of these sites by activated protein C would generate a heterotrimer of subunits that would be subject to inactivation through A2-subunit dissociation. Thus, Arg-562 was mutated to Lys to abrogate cleavage at this site. Previous observations with a full-length FVIII construct containing Arg-336-Ile and Arg-562-Lys demonstrated that these missense mutations did not interfere with synthesis, secretion, or functional activation and were resistant to APC-mediated cleavage at these sites (K. Amano and R.J.K., unpublished data). The final construct FVIII (del795–1689/Arg-336-Ile/Arg-562-Lys/Arg-740-Ala) was termed IR8.

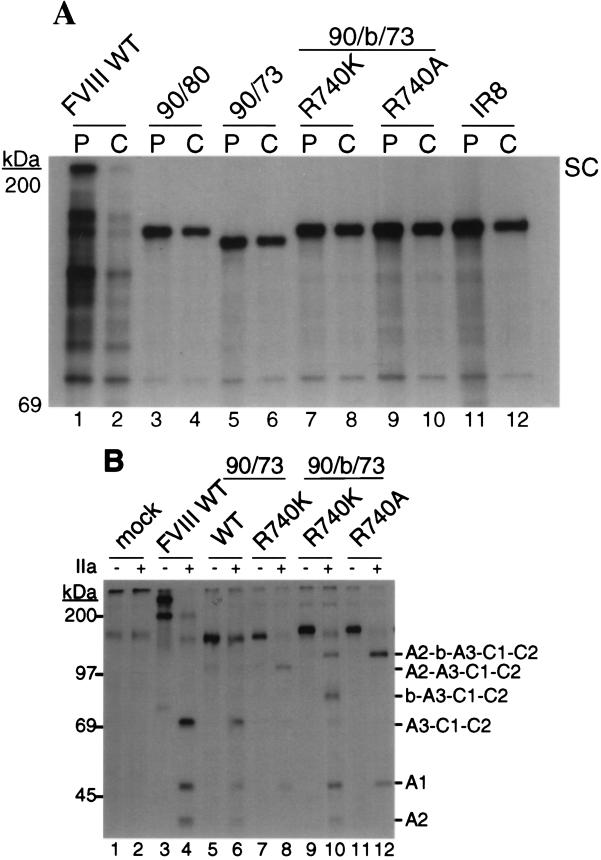

Synthesis and Secretion of IR8.

The synthesis and secretion of FVIII WT and the various inactivation-resistant mutants were compared by transient DNA transfection into COS-1 monkey cells. At 64 hr posttransfection, the rates of synthesis were analyzed by immunoprecipitation of cell extracts from [35S]methionine pulse-labeled cells. Intracellular FVIII WT was detected in its single-chain form and migrated at approximately 250 kDa (Fig. 2A, lane 1). The B domain deletion mutant 90/80 (del741–1648) migrated at ≈170 kDa (Fig. 2A, lane 3). 90/73 migrated slightly faster due to the additional deletion of the residues in the acidic region of the light chain (Fig. 2A, lane 5). All of the 90/b/73-based constructs, including IR8, (Fig. 2A, lanes 7, 9, and 11) exhibited similar band intensity to the 90/80 and 90/73 constructs, suggesting that the multiple missense mutations did not interfere with efficient protein synthesis. After a 4-hr chase period, the majority of FVIII WT was lost from the cell extract (Fig. 2A, lane 2) and was recovered from chase-conditioned medium as a 280-kDa single chain, a 200-kDa heavy chain, and an 80-kDa light chain (Fig. 2B, lane 3). All of the inactivation-resistant mutants were recovered from the chase-conditioned medium as single-chain species (Fig. 2B, lanes 5, 7, 9, and 11). Therefore the various alterations of the FVIII construct did not significantly affect secretion.

Figure 2.

Synthesis, secretion, and thrombin cleavage of FVIII WT and mutants expressed in COS-1 cells. WT and mutant plasmids were transfected into COS-1 monkey cells. At 64 hr posttransfection, cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine for 30 min, and cell extracts were harvested. Duplicate labeled cells were chased for 4 hr in medium containing excess unlabeled methionine, and then cell extracts and conditioned medium were harvested. Equal proportionate volumes of cell extract and conditioned medium were immunoprecipated with anti-FVIII-specific antibody, and equal aliquots were analyzed by SDS/PAGE. A duplicate sample of immunoprecipitated labeled protein was incubated with thrombin (1 unit/ml) for 30 min at 37°C before SDS/PAGE analysis. Mock indicates cells that did not receive plasmid DNA. Cell extract pulse (P) and chase (C) (A). Chase conditioned media before (B, −) and after thrombin digestion (B, +). The migration of FVIII WT from the cell extracts is indicated at the right as a single chain (SC). FVIII from the conditioned medium is indicated at the far right as single chain (SC), heavy chain (HC), and light chain (LC) forms. The migration of the mutants from the cell extracts and conditioned medium is indicated on the right of each image by their predicted domain structure. Molecular mass markers are shown on the left of each image.

Structural Stability of IR8 After Thrombin Cleavage.

The labeled FVIII proteins immunoprecipated from the chase-conditioned medium were incubated with thrombin (1 unit/ml) for 30 min before SDS/PAGE analysis. FVIII WT was efficiently cleaved into a heterotrimer of fragments consisting of a 50-kDa A1 subunit, 43-kDa A2 subunit, and 73-kDa thrombin-cleaved light chain, A3-C1-C2 (Fig. 2B, lane 4). 90/73 WT also was cleaved into a heterotrimer of subunits similar to FVIII WT (Fig. 2B, lane 6). 90/73 Arg-740-Lys generated a heterodimer of thrombin-cleaved subunits consistent with a 50-kDa A1 subunit and an A2-A3-C1-C2 fused light chain (Fig. 2B, lane 8). 90/b/73 Arg-740-Lys generated thrombin cleavage fragments consistent with two heteromeric species, a 50-kDa A1 and a 120-kDa A2-b-A3-C1-C2 heterodimer, as well as a 43-kDa A2 subunit and an ≈85-kDa fragment consistent with a b-A3-C1-C2 fused light chain (Fig. 2B, lane 10). The appearance of the A2 subunit after incubation with thrombin suggested that the conservative mutation Lys-740 did not completely abrogate thrombin cleavage in the presence of the b spacer. With the nonconserved missense mutation to Arg-740-Ala a stable heterodimeric species was demonstrated (Fig. 2B, lane 12). This stable heterodimeric structure after thrombin cleavage was maintained for IR8 with subsequent additions of the missense mutations Arg-336-Ile and Arg-562-Lys.

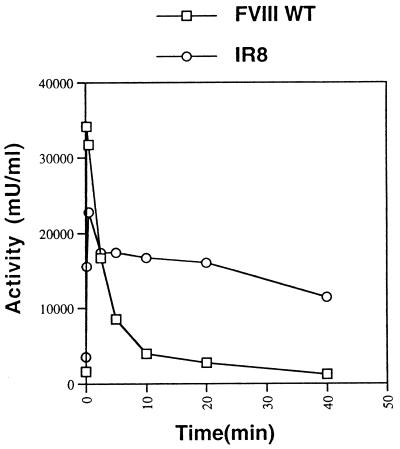

Functional Stability of IR8 After Thrombin Activation Correlates with Increased Specific Activity.

Having demonstrated the structural integrity of the IR8 heterodimer upon thrombin cleavage, the functional consequence of this modification on activation and inactivation was examined in an in vitro functional assay. Immunoaffinity-purified FVIII WT and IR8 were incubated with thrombin and assayed for FVIII activity by a one-stage APTT clotting assay. Upon treatment with thrombin, FVIII WT was maximally activated within 10 sec and then rapidly inactivated over the next 5 min. IR8 reached peak activity after 30-sec incubation with thrombin (Fig. 3), suggesting a modestly reduced sensitivity to thrombin activation compared with FVIII WT. In addition, the peak activity for thrombin-activated IR8 was lower (75 ± 7% of peak activity obtained from thrombin-activated FVIII WT, n = 3), suggesting some reduced efficiency as a cofactor. However, IR8 demonstrated significant stabilization of peak activity over the first 10-min incubation with thrombin (67 ± 5% of peak IR8 activity, n = 3), where activity of FVIII WT was less than 5%. Although a gradual loss of peak IR8 activity was seen with prolonged incubation with thrombin, IR8 still retained ≈38% of peak activity after 4-hr incubation with thrombin.

Figure 3.

Activation and inactivation of FVIII and IR8 by thrombin. Partially purified FVIII WT and IR8 proteins (1 nM) were incubated with thrombin (1 unit/ml) at room temperature and assayed over time for FVIII activity by APTT. The results are from a single thrombin activation experiment and are typical of multiple independent experiments.

Immunoaffinity-purified FVIII WT and IR8 were assayed for FVIII activity using a standard one-stage APTT clotting assay. Antigen determinations were made using a FVIII light chain-based ELISA. The specific activity values for IR8 then were calculated based on a correction for its molecular weight. IR8 was observed to have a 5-fold increased specific activity compared with FVIII WT (102 ± 43 vs. 18.6 ± 7.4 units/mg).

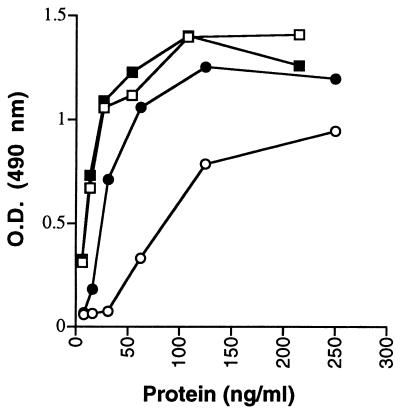

IR8 Is Not Inhibited by the mAb ESH8.

Characterization of a FVIII inhibitory mAb ESH8 demonstrated that its inhibition was dependent on binding of FVIII to vWF (38–40). Because IR8 had deleted residues required for high-affinity vWF binding, we tested the inhibitory effect of the ESH8 antibody on IR8. Because ESH8 inhibits FVIII only in the presence of vWF, IR8 first was examined for its affinity for vWF. Immunoaffinity-purified FVIII WT and IR8 proteins were assayed for their binding to vWF in solution. FVIII WT demonstrated saturable vWF binding as FVIII concentrations increased to 50 ng/ml (Fig. 4). IR8 demonstrated approximately 10-fold lower affinity for vWF, consistent with the deletion of the light chain acidic region. However, in the presence of ESH8, IR8 demonstrated significantly increased affinity for vWF.

Figure 4.

FVIII-vWF binding of partially purified FVIII proteins as determined by ELISA. FVIII WT and IR8 proteins were purified through immunoaffinity chromotography and analyzed for binding to vWF after incubation with human FVIII-deficient plasma. O.D. represents the absorbance obtained through the detection of FVIII-vWF complexes by an anti-vWF-horseradish peroxidase conjugate antibody in the presence of O-phenylendiamine dihydrochloride. Squares, FVIII WT; circles, IR8; open symbols, absence of ESH8; closed symbols, presence of ESH8.

The functional impact of this ESH8-induced binding of IR8 to vWF complex was evaluated by assaying for FVIII activity using the one-stage clotting assay (Table 1). In the absence of ESH8, immunoaffinity-purified FVIII WT and IR8 demonstrated minimal loss of activity over a 4-hr incubation at 37°C with FVIII-deficient plasma. In the presence of ESH8, FVIII WT activity was inhibited to 30%, whereas IR8 retained 100% of its initial activity. These results suggest that inactivation of WT FVIII in the presence of ESH8 may be due to A2 subunit dissociation, and IR8 is resistant to inactivation by ESH8 because it is not susceptible to A2 subunit dissociation.

Table 1.

ESH8 does not inhibit IR8 activity in presence of vWF

| Protein | % of initial activity

|

|

|---|---|---|

| −ESH8 | +ESH8 | |

| FVIII WT | 92 ± 3 | 29 ± 13 |

| IR8 | 101 ± 2 | 120 ± 27 |

DISCUSSION

With an increased understanding of the requirements for FVIII function, studies have attempted to produce improved FVIII molecules for replacement therapy for patients with hemophilia A. Strategies investigated thus far have included the deletion or modification of FVIII sequences, resulting in more efficient expression. These strategies, although offering potential for more efficient manufacturing of recombinant protein or more efficient delivery through gene therapy, have not increased FVIII plasma half-life or specific activity; either of which could potentially reduce the amount of FVIII required for efficient replacement for hemorrhagic events. Decreasing the amount of FVIII protein for replacement therapy would have tremendous benefit to individuals with hemophilia A because this would not only reduce the cost of treatment but should minimize inhibitor antibody development that occurs in response to the heavy antigen load of FVIII being recognized as a foreign protein. Our studies have focused on the potential to develop an improved FVIII therapeutic by increasing the specific activity of recombinant FVIII.

Previous studies on the requirements for functional activity of FVIII demonstrated that cleavage after Arg residues 372 and 1689 both were required for activation of factor VIII and that the B domain was not required for functional activity (13, 22–24). Deletion of residues 741-1689 yielded a functional molecule (90/73) that displayed WT thrombin cleavage and activation, resulting in a heterotrimer similar to WT FVIIIa that was susceptible to rapid dissociation of the A2 subunit. We tested the hypothesis whether mutagenesis of the 740-1690 cleavage site within 90/73 would yield a functional molecule that was activated by thrombin as a result of a single cleavage at Arg-372. However, mutation of the 740-1690 junction within 90/73 destroyed its activity, although the resultant molecule was susceptible to thrombin cleavage at Arg-372. These results suggested that either cleavage at the amino terminus of the light chain is required to elicit procoagulant activity or that the A2 subunit requires an appropriate distance from the A3 domain in the light chain. When a 54-aa spacer, comprised of B domain sequence, was introduced between the A2 domain and the light chain, near WT activity, as well as thrombin activation, was restored. These results demonstrate both that thrombin activation of FVIII does not require cleavage at the amino terminus of the light chain and that there is a spatial requirement between the light chain and the A2 domain for FVIII activity. The spatial requirement may reflect the two factor IXa interaction sites identified at residues Ser-558–Glu-565 in the A2 domain that interacts with the factor IXa serine protease domain (41, 42) and Glu-1811–Lys-1818 in the A3 domain that interacts with the factor IXa epidermal growth factor 1 domain (43, 44). Most significantly, the resultant molecule IR8 was cleaved at a single site after Arg-372 to generate procoagulant activity and was resistant to inactivation mediated by A2 domain dissociation. These results support the importance of A2 subunit dissociation as a mechanism for inactivation of FVIIIa, as originally proposed by Lollar and Parker (45). The importance of cleavage at residue 372 previously was demonstrated by identification of mutants in Arg-372 that result in hemophilia A (16) and by analysis of site-directed mutants of Arg-372 (13). Interestingly there was a ≈25% loss of IR8 activity within the first 30 sec to 2.5 min after thrombin activation followed by only a very gradual loss of activity occurring over hours. We propose that noncleavage-mediated inactivation is responsible for the immediate loss of peak activity. It is possible that the “spacer” length or composition used in this form of IR8 is not optimal. This possibility also is supported by the observation that the peak activity observed immediately after thrombin activation is less than that obtained with FVIII WT. Perhaps some unfolding of the IR8 protein occurs after activation and precludes efficient interaction with factor IXa. Further analysis of additional molecules based on IR8 having alternate spacer lengths or amino acid content may optimize the inactivation resistance.

Initial studies supported that vWF interacts with the acidic amino acid-rich amino terminus of the FVIII light chain. mAbs to residues 1670–1689 inhibit interaction with vWF (46–48) and deletion of a portion of this region destroys high-affinity vWF interaction (47). However, the isolated acidic peptide 1648–1689 was incapable of binding vWF, suggesting the vWF interaction requires other regions of the FVIII molecule. We have shown that deletion of the acidic amino acid-rich region in the light chain in IR8 yields a molecule that has 10-fold reduced interaction with vWF. More recently, it was demonstrated that antibodies to the carboxy-terminus of the C2 domain of FVIII inhibit vWF binding and support that the C2 domain is also important for vWF interaction. One C2 domain antibody, ESH8, reacts with a C2 domain epitope between residues 2248–2285 and is inhibitory only in the presence of vWF. We have shown that IR8 binding to vWF is increased approximately 5-fold in the presence of the ESH8 antibody. These results support that the high-affinity vWF binding site in IR8 is intact but its conformation is inadequate to support high-affinity vWF interaction. We propose that ESH8 antibody binding to IR8 induces a conformation that is capable of high-affinity vWF interaction. The ESH8-induced conformational change may be similar to the conformational change induced by the presence of the acidic amino acid-rich region in the FVIII light chain.

Frequently, hemophilia A patients treated with FVIII develop alloantibodies that react with the C2 domain and inhibit FVIII activity. ESH8 is one anti-C2 domain inhibitory antibody that does not interfere with binding of FVIII to vWF and for which the mechanism of FVIII inactivation has been studied. Studies support that ESH8 stabilizes the FVIII-vWF interaction to delay release of FVIIIa from vWF by 4-fold, so that A2 domain dissociation occurs before FVIIIa release from vWF (40). The unique stability of IR8 after thrombin-activation provided a useful reagent to test this hypothesis that previously was derived from kinetic measurements. We characterized the inhibitory effect of ESH8 on IR8 and found that IR8 was resistant to inactivation mediated by the ESH8 antibody. These results suggest that molecules similar to IR8 may provide therapeutic efficacy in patients that have FVIII inhibitor antibodies similar to ESH8.

We have tested the hypothesis that a heterodimeric FVIIIa molecule that is resistant to spontaneous inactivation through dissociation of the A2 subunit would increase its specific activity. The results show that IR8 exhibits a dramatically increased stability after thrombin activation under physiological conditions. The in vitro specific clotting activity of IR8 was increased approximately 5-fold over WT recombinant FVIII. These results support the importance for A2 domain dissociation in limiting FVIII activity in vitro. Future studies are required to evaluate the importance of A2 domain dissociation in limiting FVIII activity in vivo. These studies now can be performed with the IR8 molecule. Analysis of IR8 molecules that either contain or lack mutations at the APC inactivation sites at Arg-336 and Arg-562 will provide important information on the mechanism of inactivation of FVIII in vivo. Finally, the ability to isolate a stable form of FVIIIa will provide a critical reagent for structural studies as well as a means to study the importance of FVIIIa generation in thrombosis by infusion of stable FVIIIa into in vivo models of thrombotic disease.

Acknowledgments

S.W.P. is a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow of the Pediatric Scientist Development Program. R.J.K. was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HL52173.

ABBREVIATIONS

- FVIII

factor VIII

- FVIIIa

thrombin-activated factor VIII

- WT

wild type

- vWF

von Willebrand factor

- IR8

inactivation-resistant factor VIII

- APTT

activated partial thromboplastin time

References

- 1.Vehar G A, Keyt B, Eaton D, Rodriguez H, O’Brien D P, Rotblat F, Oppermann H, Keck R, Wood W I, Harkins R N, Tuddenham E G D, Lawn R M, Capon D J. Nature (London) 1984;312:337–342. doi: 10.1038/312337a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toole J J, Knopf J L, Wozney J M, Sultzman L A, Buecker J L, Pittman D D, Kaufman R J, Brown E, Shoemaker C, Orr E C, Amphlett G W, Foster B W, Coe M L, Knutson G J, Fass D N, Hewick R M. Nature (London) 1984;312:342–347. doi: 10.1038/312342a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufman R J, Wasley L C, Dorner A J. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:6352–6362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eaton D, Rodriguez H, Vehar G A. Biochemistry. 1986;25:505–512. doi: 10.1021/bi00350a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girma J P, Meyer D, Verweij C L, Pannekoek H, Sixma J J. Blood. 1987;70:605–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamer R J, Koedam J A, Beeser-Visser N H, Sixma J J. Eur J Biochem. 1987;167:253–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koedam J A, Hamer R J, Beeser-Visser N H, Bouma B N, Sixma J J. Eur J Biochem. 1990;189:229–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss H J, Sussman I I, Hoyer L W. J Clin Invest. 1977;60:390–404. doi: 10.1172/JCI108788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mertens K, van Wijngaarden A, Bertina R M. Thromb Haemostasis. 1985;54:654–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Dieijen G, Tans G, Rosing J, Hemker H C. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:3433–3442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fay P J. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;952:181–190. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(88)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fay P J, Haidaris P J, Smudzin T M. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8957–8962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pittman D D, Kaufman R J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2429–2433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fay P J, Beattie T L, Regans L M, O’Brien L M, Kaufman R J. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6027–6032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gitschier J, Kogan S, Levinson B, Tuddenham E G. Blood. 1988;72:1022–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson D J, Pemberton S, Acquila M, Mori P G, Tuddenham E G, O’Brien D P. Thromb Haemostasis. 1994;71:428–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regan L M, Fay P J. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8546–8552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fulcher C A, Gardiner J E, Griffin J H, Zimmerman T S. Blood. 1984;63:486–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fay P J, Anderson M T, Chavin S I, Marder V J. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;871:268–278. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(86)90208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nesheim M, Pittman D D, Giles A R, Fass D N, Wang J H, Slonosky D, Kaufman R J. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17815–17820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fay P J, Coumans J V, Walker F J. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2172–2177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toole J J, Pittman D D, Orr E C, Murtha P, Wasley L C, Kaufman R J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5939–5942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.16.5939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eaton D L, Wood W I, Eaton D, Hass P E, Hollingshead P, Wion K, Mather J, Lawn R M, Vehar G A, Gorman C. Biochemistry. 1986;25:8343–8347. doi: 10.1021/bi00374a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meulien P, Faure T, Mischler F, Harrer H, Ulrich P, Bouderbala B, Dott K, Sainte Marie M, Mazurier C, Wiesel M L, Pol H V d, Cazenave J-P, Courtney M, Pavivani A. Protein Eng. 1988;2:301–306. doi: 10.1093/protein/2.4.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarver N, Ricca G A, Link J, Nathan M H, Newman J, Drohan W N. DNA. 1987;6:553–564. doi: 10.1089/dna.1987.6.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pittman D D, Alderman E M, Tomkinson K N, Wang J H, Giles A R, Kaufman R J. Blood. 1993;81:2925–2935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaufman R J. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:487–511. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85041-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erlich H A. PCR Technology: Principles and Applications for DNA Amplification. New York: Stockton; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynch C M, Israel D I, Kaufman R J, Miller A D. Hum Gene Ther. 1993;4:259–272. doi: 10.1089/hum.1993.4.3-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pittman D D, Marquette K A, Kaufman R J. Blood. 1994;84:4214–4225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pittman D D, Kaufman R J. Methods Enzymol. 1993;222:236–260. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)22017-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michnick D A, Pittman D D, Wise R J, Kaufman R J. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20095–20102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zatloukal K, Cotten M, Berger M, Schmidt W, Wagner E, Birnstiel M L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5148–5152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pipe S W, Kaufman R J. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25671–25676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bihoreau N, Paolantonacci P, Bardelle C, Fontaine-Aupart M P, Krishnan S, Yon J, Romet-Lemonne J L. Biochem J. 1991;277:23–31. doi: 10.1042/bj2770023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fay P J, Haidaris P J, Huggins C F. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17861–17866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fay P J, Smudzin T M, Walker F J. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20139–20145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saenko E L, Shima M, Rajalakshmi K J, Scandella D. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11601–11605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scandella D, Gilbert G E, Shima M, Nakai H, Eagleson C, Felch M, Prescott R, Rajalakshmi K J, Hoyer L W, Saenko E. Blood. 1995;86:1811–1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saenko E L, Shima M, Gilbert G E, Scandella D. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27424–27431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fay P J, Beattie T, Huggins C F, Regan L M. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20522–20527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Brien L M, Medved L V, Fay P J. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27087–27092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lenting P J, Christophe O D, Maat H, Rees D J G, Mertens K. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25332–25337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lenting P J, van de Loo J W, Donath M J, Van Mourik J A, Mertens K. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1935–1940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.4.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lollar P, Parker C G. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1688–1692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foster P A, Fulcher C A, Houghten R A, Zimmerman T S. Blood. 1990;75:1999–2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leyte A, Verbeet M P, Brodniewicz-Proba T, Van Mourik J A, Mertens K. Biochem J. 1989;257:679–683. doi: 10.1042/bj2570679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shima M, Yoshioka A, Nakai H, Tanaka I, Sawamoto Y, Kamisue S, Terada S, Fukui H. Int J Hematol. 1991;54:515–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]