Abstract

Known major mutations such as BRCA1/2 and TP53 only cause a small proportion of heritable breast cancers. Co-dominant genes of lower penetrance that regulate hormones have been thought responsible for most others. Incident breast cancer cases in the identical (monozygotic) twins of representative cases reflect the entire range of pertinent alleles, whether acting singly or in combination. Having reported the rate in twins and other relatives of cases to be high and nearly constant over age, we now examine the descriptive and histological characteristics of the concordant and discordant breast cancers occurring in 2310 affected pairs of monozygotic and fraternal (dizygotic) twins in relation to conventional expectations and hypotheses. Like other first-degree relatives, dizygotic co-twins of breast cancer cases are at higher than usual risk (standardised incidence ratio (SIR)=1.7, CI=1.1–2.6), but the additional cases among monozygotic co-twins of cases are much more numerous, both before and after menopause (SIR=4.4, CI=3.6–5.6), than the 100% genetic identity would predict. Monozygotic co-twin diagnoses following early proband cancers also occur more rapidly than expected (within 5 years, SIR=20.0, CI=7.5–53.3). Cases in concordant pairs represent heritable disease and are significantly more likely to be oestrogen receptor-positive than those of comparable age from discordant pairs. The increase in risk to the monozygotic co-twins of cases cannot be attributed to the common environment, to factors that cumulate with age, or to any aggregate of single autosomal dominant mutations. The genotype more plausibly consists of multiple co-existing susceptibility alleles acting through heightened susceptibility to hormones and/or defective tumour suppression. The resultant class of disease accounts for a larger proportion of all breast cancers than previously thought, with a rather high overall penetrance. Some of the biological characteristics differ from those of breast cancer generally.

British Journal of Cancer (2002) 87, 294–300. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600429 www.bjcancer.com

© 2002 Cancer Research UK

Keywords: breast neoplasms, genetics, etiology, pathogenesis, twins

The prevalence of familial cases indicates that about 10% of all breast cancers are heritable (Rowell et al, 1994), but major mutations such as BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53 can only be a minority of these (Cui et al, 2001b; Peto et al, 1999); familial cases are especially prominent before menopause (Pharoah et al, 1997). The genes responsible for most heritable breast cancers are unidentified. Due to the role of hormones in breast cancer risk, genes regulating hormone production or transport have been emphasized. Those that are common and of low penetrance have been singled out (Ford et al, 1995; Feigelson et al, 1996), and an autosomal mode of inheritance is thought likely (Williams and Anderson, 1984; Newman et al, 1988; Iselius et al, 1991; Cui et al, 2001a; Claus et al, 1991; Chen et al, 1995; Bishop et al, 1988).

Although BRCA1 tumours are less likely to express oestrogen receptors (Armes et al, 1999; Phillips, 2000), heritable tumours seem histologically heterogeneous (Lakhani et al, 2000). Attempts to separate non-heritable from heritable breast cancer cases have relied on family history, and even when based on first-degree relatives, this criterion is unsatisfactory. Many genetically determined cases give a false negative family history (Cui and Hopper, 2000), and false positive histories occur by chance, especially in large families. Even BRCA1/2 mutations do not correlate particularly well with family history (Hopper et al, 1999). Moreover, true multiplex families mostly reflect conditions of high penetrance. Cases caused by gene combinations, recessive genes, or genes of low penetrance are less likely to have affected relatives. Thus neither the true proportion of breast cancers that are heritable nor the proportionate role of specific genetic determinants is actually known.

Adult twins are ordinary persons who share a nearly identical early environment as well as about half (dizygotic) or all (monozygotic) of the genome. Monozygotic (MZ) twinning is not known to be appreciably influenced by either genetic or environmental factors. Therefore the cases of disease among MZ twins can be presumed genetically representative of the population, and disease-concordant pairs must necessarily share all heritable determinants. We have reported (Peto and Mack, 2000) that the subsequent annual incidence in the MZ co-twins of breast cancer cases is not only extremely high (1300 : 100 000) but relatively constant throughout life, just as it is in the contra-lateral breasts of cases (Robbins and Berg, 1964; Hislop et al, 1984; Harvey and Brinton, 1985). Here we assess in more detail the breast cancers occurring in the MZ and DZ twins of representative breast and other cancer cases (Mack et al, 2000), report the unique descriptive and histological characteristics of concordant twin breast cancer cases, and examine current hypotheses in light of the findings.

METHODS

From 1980–91, 17 245 affected twin pairs responded to advertisements seeking ‘twins with cancer and other chronic diseases’ in the non-classified pages of major periodicals serving English-speaking North America (Mack et al, 2000). Each pair was contacted by telephone and asked to provide details of their age, zygosity, and diagnosis.

Among the 6325 female twin pairs with cancer were 2562 probands with breast cancer, including the members of 200 MZ and 109 dizygotic (DZ) concordant pairs. More than 95% were non-Latino and white, and we have assessed their representiveness by computing the estimated prevalence of breast cancer cases among living white adult twins in North America (Mack et al, 2000), using cohort-specific birth rates (Elwood, 1973; Jeanneret and Macmahon, 1962; Statistics NCfH, all years), life tables (Kleinman et al, 1991), and site-specific cancer incidence (Gaudette, 1992; Hankey and Percy, 1992) and survival (Hankey et al, 1993). We also compared the unaffected co-twins to population-based samples of healthy US residents (Mack et al, 2000). We estimate that we identified over a third of all MZ twin breast cancer cases occurring before age 60 in the period. Our ascertainment was less complete for twin cases who were DZ, over 65 at diagnosis, or discordant for disease at the time of ascertainment, but neither region, community characteristics, interval since diagnosis, nor outcome appeared to influence ascertainment (Mack et al, 2000).

Medical records were sought to verify diagnoses, and were obtained for 80% of the breast cancer cases. Of those, 94% were reported to be invasive. Tumour specimens were requested for review (successfully in 65%) and cases were classified according to standard cancer registry practice (Percy et al, 1990). When diagnostic and classificational errors were found to be negligible among the first 805 specimens reviewed, the practice was discontinued. Twins' perception of their zygosity, repeatedly shown to be over 90% accurate by others (Kasriel and Eaves, 1976; Torgersen, 1979) as well as ourselves (Deapen et al, 1992; Kumar et al, 1993), were nearly all in agreement, and those in disagreement were excluded from zygosity-specific results.

All twins were followed prospectively by mail to identify deaths and new diagnoses. National age, period, and neoplasm-specific incidence rates (Hankey and Percy, 1992), were applied to the person-years of follow-up to estimate the expected number of new cases. The indirectly age-adjusted standardised incidence ratio of observed to expected cases (SIR), was calculated by age, sex, and zygosity, as was the incidence rate/100 000 person-years. Since inclusion of some co-twins preferentially identified as cases in retrospect at original ascertainment may introduce bias, pairs already concordant at ascertainment were excluded. Thus analysis was restricted to the initially unaffected 2310 co-twins of breast cancer cases and 3628 co-twins of other cancer cases. Events occurring between ascertainment of the affected pair and the date of last contact, always prior to February 1, 1993, were recorded. For MZ twins of breast cancer cases, the average length of follow-up was 4.8 (95% CL 4.6–5.0) years, with 16.4 and 49.0% followed for one year or less and 5 or more years respectively. For DZ twins of breast cancer cases, the average follow-up was for 4.6 (95% CL 4.4–4.8) years, with 14.9 and 48.8% followed for 1 or less and 5 or more years respectively.

For concordant pairs (including those concordant at ascertainment) and a sample of MZ discordant pairs, additional efforts were made to obtain representative tumour blocks from the initial breast cancer surgery. Using the paraffin-embedded tissue from 196 cases from concordant pairs and 190 cases from MZ discordant pairs, a single pathologist (MP) blindly reviewed the histology of the tumours, and assessed the prevalence of oestrogen receptors (ER), progestin receptors (PR), p53, and HER-2/neu expression by immunohistochemical methods. HER2/neu membrane protein was scored as low, over-expressed, or highly over-expressed, and considered positive under either of the latter alternatives. ER, PR, and p53 nuclear proteins were scored by prevalence of cells staining at each of three levels of intensity. For the present purpose a tumour was considered to be positive if 10% or more of the cells stained positively. Multivariate linear regression analysis (SAS Proc GLM) was used to control for age at diagnosis when comparing the frequency of positive tumour markers among the twin pair subsets.

Religious preference was obtained by questionnaire from the twins comprising 1944 affected pairs. We located and obtained blood samples from 27 surviving cases belonging to 19 multiplex Jewish families in which diagnoses occurred before 50. Three common Ashkanazi mutations: two BRCA1 (185delAG, exon 2, and 5382insC, exon 20) and one BRCA2 (6174delT, exon 11) were tested (Ursin et al, 1997).

RESULTS

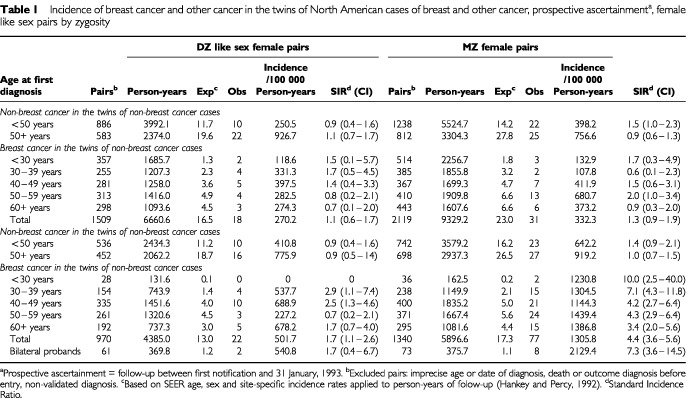

One hundred and forty-eight cancers of the breast in the initially healthy co-twins of cancer cases were diagnosed during the period of prospective follow-up, of whom 99 (22 DZ and 77 MZ) occurred among the co-twins of breast cancer cases. Table 1 describes the occurrence of these prospectively identified cancers in terms of incidence and standardised incidence ratio according to zygosity, age and site of proband diagnosis, and person-years of follow-up.

Table 1. Incidence of breast cancer and other cancer in the twins of North American cases of breast and other cancer, prospective ascertainmenta, female like sex pairs by zygosity.

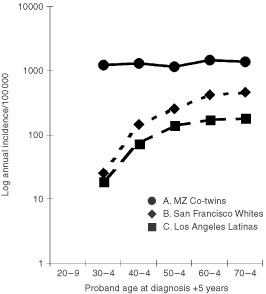

Breast cancer incidence in the co-twins of non-breast cancer cases increased with age past menopause as expected, and for all ages combined, no substantial or significant risk attributable to twin status was found. Marginal excesses of malignancy other than breast cancer occurred in MZ, but not DZ, twins of breast cancer cases diagnosed before age 50. The appearance of additional breast cancer cases among the initially healthy co-twins of breast cancer cases was substantial and significant. Among the DZ co-twins, the 22 new cases represent an unstable annual age-specific incidence ranging from 227 to 689 : 100 000, reflecting a statistically significant age-adjusted SIR of 1.7, a 70% excess over expected. Among the MZ co-twins, the 77 new cases reflect an annual incidence ranging from 1144 to 1439 : 100 000, and an overall SIR of 4.4, a 340% excess over expected, and one as high as 7.1 before 40 years of age. Figure 1 compares the age-specific rates in the MZ co-twins to the highest and lowest North American population-based rates (Parkin et al, 1992). If the MZ proband had bilateral breast cancer, especially likely to represent heritable disease (Bernstein et al, 1992; Hislop et al, 1984), the SIR for the co-twins showed a similar gradient with age and was even higher overall at 7.3, reflecting an attributable excess of 630%. Overall, 23% and 3% of the concordantly affected MZ pairs had one and more than one affected first degree relative respectively (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Age-specific Incidence of breast cancer in identical co-twins of breast cancer cases compared to that in highest and lowest risk North American populations (42).

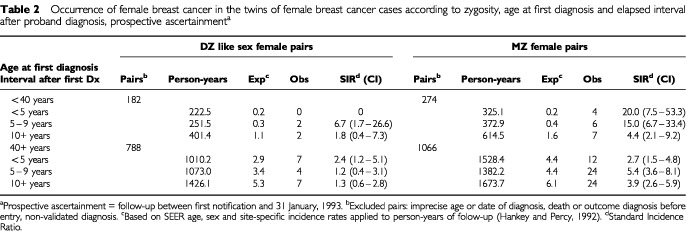

In Table 2, the appearance of breast cancer in co-twins is described according to the interval following the proband's cancer diagnosis. Within the first five years after the diagnosis in a proband younger than age 40, the SIR among MZ co-twins was many times higher than expected, and the magnitude fell in inverse proportion to the time elapsed. This tendency was not apparent among DZ co-twins or after diagnoses in older probands.

Table 2. Occurrence of female breast cancer in the twins of female breast cancer cases according to zygosity, age at first diagnosis and elapsed interval after proband diagnosis, prospective ascertainmenta.

Overall, 8.6% of the concordant and 7.6% of the discordant MZ pairs identified themselves as Jewish. Among those first diagnosed before age 50, 10.1% of those concordant and 6.8% of those discordant did so. Thus being Jewish increased the risk of concordant diagnoses by a factor of 1.3 overall, and 1.5 premenopausally. Of the 19 tested multiplex Jewish families with at least one premenopausal diagnosis, BRCA1 mutations were found in 4, and a BRCA2 mutation in 1.

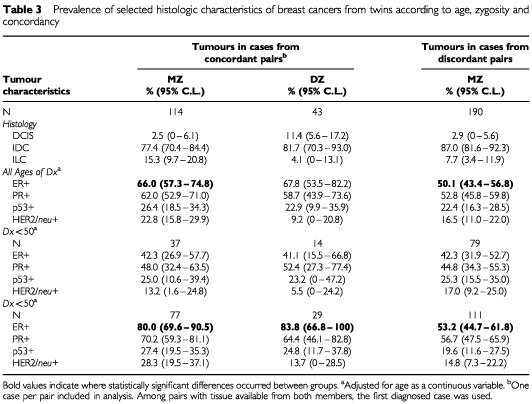

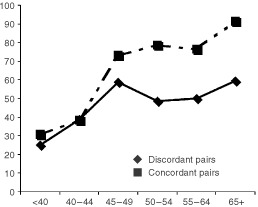

More than 97% of the tissue samples from MZ twins (concordant and discordant) showed evidence of invasiveness (Table 3) Although a slightly higher proportion of lobular tumours occurred among the MZ concordant pairs, no significant difference by histologic subtype (ductal, lobular, ductal in-situ) was found, and only a single tumour (in a DZ twin) showed a medullary histopathology. PR and ER positivity were significantly more common among older cases, and ER positivity was significantly higher among cases from concordant than among those from discordant pairs, especially after age 50 (Figure 2). After age 50, HER2/neu and p53 were more common among cases from concordant than discordant MZ pairs; the former difference was significant and the latter nearly so. Biomarker combinations were examined, and concordant cases were more likely to be ER+PR+ (age-adjusted prevalence=54.1%1.7% MZ, 55.07.2% DZ) than were discordant cases (41.30.8% MZ), but the difference could be explained by chance. No excess prevalence of ER-p53+ concordant cases was found (concordant MZ 13.21%, DZ 12.84.6%, and discordant MZ 13.914.4%).

Table 3. Prevalence of selected histologic characteristics of breast cancers from twins according to age, zygosity and concordancy.

Figure 2.

Percentage of tumours ER+ by age at diagnosis: MZ cases from breast cancer concordant and discordant pairs.

DISCUSSION

Since DZ co-twins experience a level of risk no higher than that of other first-degree relatives generally (Brinton et al, 1982; Claus et al, 1990; Houlston et al, 1992; Olsen et al, 1999; Thompson, 1994; Tulinius et al, 1992), despite sharing a substantially more similar environment, the very high incidence among representative MZ co-twins of breast cancer cases (Table 1) serves to verify the substantial heritability of this disease (Easton et al, 1993; Eby et al, 1994; Lichtenstein et al, 2000; Thompson, 1994). Moreover, our estimate of incidence in MZ co-twins is probably an underestimate. It is based solely on prospective follow-up, and a number of rapidly concordant MZ pairs, i.e. those with co-twin cases occurring soon after the proband diagnosis but before ascertainment, were preferentially excluded to eliminate bias. The similarity of the observed high and constant age-specific rate to that in the contralateral breasts of breast cancer cases (Harvey and Brinton, 1985; Robbins and Berg, 1964) provides additional evidence that bilateral disease is largely attributable to the genome rather than the personal environment.

No more than a small minority of heritable co-twin cases can be attributed to BRCA1/BRCA2 or other known major mutations. More than three-fourths of the additional cases among MZ co-twins occur after 40 (Table 1), whereas most BRCA1/2 cases occur before that age (Ford et al, 1998). While 23% of the concordantly affected MZ pairs had one affected first degree relative, only 3% had more than one, in strong contrast to BRCA1/2 cases (Cui and Hopper, 2000). Jewish women are at high risk from disease caused by major mutations. Although the risk to a woman from a Jewish multiplex family (Egan et al, 1996) or a Jewish family with a BRCA1/2 mutation (Fodor et al, 1998) is increased by a factor of 3–4, and although Jewish women are also at higher risk from additional breast cancer risk factors (Swift et al, 1987), we found that a Jewish MZ co-twin's risk of becoming affected was increased only marginally more than that to Jewish women generally (Mack et al, 1985; Warner et al, 1999). Even among multiplex Jewish families with early cases, we could identify only a few with BRCA1/2 mutations. Moreover, whereas BRCA1/2 neoplasms tend to be ER-, especially in connection with P53 mutations, and tend to include an excess of the medullary histological type (Lakhani, 1999; Phillips, 2000), the tumours in these concordant MZ twins were not medullary, and tended to be ER+, without a link to P53 mutations (Table 3, Figure 2).

The proportion of MZ co-twin cases attributable to genetic determinants is roughly 77% (4.4-1)/4.4) (Table 1), indicating that MZ twin breast cancer-concordant cases, unlike familial cases generally, are much more likely than not to represent heritable cases. Based on the observed age-specific incidence in the co-twins of MZ cases (Table 1), the cumulative risk among those surviving to age 75 would be at least 44.5%, indicating that only a fraction of the minority with heritable disease remain discordant. MZ twin breast cancer-discordant cases can therefore be presumed to represent disease which is not strongly heritable. Material from breast cancer concordant and discordant MZ twin pairs clearly offers the best opportunity available to compare cases that are heritable with those that are not.

Our results suggest that heritable breast cancer represents a larger proportion of the total burden than conventionally thought. In Scandinavia (Lichtenstein et al, 2000), 14% of MZ twin pairs were found to be concordant. However, the population-based ascertainment ignored discordant mortality and necessarily excluded substantial numbers of subjects at the extremes of age at risk, as has been pointed out (Risch, 2001), indicating that the actual cumulative concordance exceeds 20%. If so, and if more than 77% of the cases in MZ twins represent heritable forms of disease, the proportion of all breast cancer represented by heritable disease exceeds 15%, and we have speculated on other grounds that it may be even higher (Peto and Mack, 2000).

The pattern of occurrence in MZ and DZ co-twins is determined by the mode of inheritance of disease. Any excess risk to a DZ twin of a case is the result of sharing 50% of the genome and a common early environment. Given a predominantly autosomal dominant mode of inheritance, the increment of risk to an MZ co-twin would be slightly less than double that to a DZ co-twin. This is because the additional risk from sharing the other half of the genome would produce the same incremental contribution as that from sharing the first half, and little, if any, added environmental risk would be expected, because the commonality of MZ twins' early environment is probably only marginally greater than that of DZ twins. Since the DZ twin of a case suffers a 70% increase in risk (overall relative risk of 1.7 from Table 1), an increase of under 140% would be expected. In fact, a relative risk of 4.4 (Table 1) indicates an increase of at least 340%, and the confidence limits are such that the difference cannot be explained by chance. A similarly large increase in risk attributable to MZ status can be calculated from the Scandinavian twins study (Lichtenstein et al, 2000). Such a large increment indicates that most heritable breast cancers do not result from single autosomal dominant alleles. While a recessive mode of inheritance cannot be ruled out, that would seem an unlikely alternative, especially as a cause of older cases (Cui et al, 2001b). It is more likely that a substantial proportion of heritable breast cancer in both younger and older women is polygenic, resulting from the interaction of two or more coexisting alleles (Chen et al, 1995). In such a circumstance, a gene acting through a hormonal mechanism might only do so in the presence of another existing genetic error in, for example, a repair (tumour suppression) gene. Such a combination would explain how a general defect of molecular repair might only produce malignancy in one specific organ (Haber, 2000).

The pattern of occurrence in MZ twins also necessarily reflects the mechanism of heritable breast carcinogenesis. The shorter than expected intervals between co-twin diagnoses (Table 2) are similar to the chronologic sequence of primary and contra-lateral breast cancer diagnoses (Harvey and Brinton, 1985; Prior and Waterhouse, 1978; Robbins and Berg, 1964; Storm and Jensen, 1986) and, given the long latency, points to a roughly similar early age at the time of a crucial causal event.

Moreover, to attain an incidence level over 1200 : 100 000 before age 30 (Table 1), the age-specific incidence of strictly heritable disease must have risen very early and rapidly and must account for nearly every early case. While the rate in MZ co-twins, based on sporadic as well as heritable disease, stays virtually constant (Figure 1), the population-based rate, largely from sporadic cases, increases with age by an order of magnitude. The rate of heritable disease therefore could not increase much over the same period and may actually decline, another observation inconsistent with causation by age-specific hormone accumulation. Thus alleles such as those at CYP 17 (Henderson and Feigelson, 2000) are unlikely to be the predominant determinants of heritable disease. Nor is the polymorphism responsible for enzymatic conversion of androgens into oestrogens (CYP19) likely to play a major role in heritable disease, since this conversion takes place in fat cells, largely after menopause, and too late to explain the early excess in risk.

Thus genetically determined high hormone levels are probably not the predominant mechanism of heritable breast cancer carcinogenesis. In fact the focus on high hormone levels as the phenotypic expression of causal genes may be misplaced, because the familial aggregation of hormone levels may not be even principally genetic in origin. Lifestyle, including physical exercise (Bernstein et al, 1994), perinatal conditions (Ekbom et al, 1997, 2000), transient episodes of disease-induced catabolism, and deficiencies in early diet (Berkey et al, 2000; Willett, 1997), produce variations in age at maturation, and probably underlie most of the change in risk seen after migration (Shimizu et al, 1991) and economic development (Miller and Bulbrook, 1986). Because families vary in the ease and rapidity of acculturation and adaptation, age-specific hormone profiles are likely to vary between them.

An alternative mechanism of heritable susceptibility, a genetically determined high cellular sensitivity to reproductive hormones, is suggested by an animal model and does fit the observed pattern of occurrence. When treated with estradiol at a standard dosage, certain rat strains rapidly develop breast cancer almost without exception (Shull et al, 1997; Harvell et al, 2000). Cancers resultant from a genetically induced enhancement of human sensitivity to hormone exposure would be induced by the first major endogenous hormone exposure at puberty, resulting in a pattern of risk like that observed among MZ twins (Table 1). Such sensitivity might result from polymorphic variation in the human estrogen receptor (ER) gene (Andersen et al, 1994), or by either overexpression of a transcription co-activator or underexpression of a co-repressor (Ansick et al, 1997). Age-specific breast sensitivity is precedented by radiogenic carcinogenesis which is closely tied to early age at exposure (Aisenberg et al, 1997), and adolescent soy intake during adolescence may preferentially reduce breast cancer risk (Shu et al, 2001).

Twins comprise 2% of the North American population (Mack et al, 2000) and suffer over 20 000 cancer diagnoses each year. We found no unusual cancer risk to twins as twins, since no significant or substantial increase in overall relative risk of cancer to the twin of a case of another form of cancer appeared (Table 1). While there seems to be no difference between breast cancer risk to the DZ twin of a case and that to a non-twin sibling, the high risk to the MZ co-twin of an early breast cancer, being twice that of a second primary diagnosis, is of serious clinical concern. More frequent screening procedures, chemoprophylaxis, and possibly prophylactic surgery, with all corresponding pros and cons, should be discussed with each such woman, as if she were a high risk gene carrier. Unfortunately, twins rarely volunteer their twin status to their doctors. The question of twinship should be posed to every patient when the diagnosis of a serious familial disease is under consideration. Such a practice will become even more clinically important as our knowledge of heritable risk and gene/environment interaction expands.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant RD-105 from the American Cancer Society, Public Health Service grants CA32262 and CA42581 from the National Cancer Institute, and DAMD17-94-J-4290 from the Department of Defense. We acknowledge the invaluable contributions of Dennis Deapen, DrPH, who administered the registry staff and of Janice Schaefer, RN, who designed and maintained the registry of twin cases. We thank Julian Peto for joint discussion of certain results. Lastly, we are grateful to the thousands of twins who readily understood the value of their unique contribution to science and gave valuable time to assist us.

References

- AisenbergAFinkelsteinDDoppkeKKoernerFBoivinJ-FCGW1997High risk of breast carcinoma after irradiation of young women with Hodgkin's disease Cancer 7912031210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AndersenTHeimdalKSkredeMTveitKBergKBorresenA-L1994Oestrogen receptor (ESR) polymorphisms and breast cancer susceptibility Hum Genet 94665670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AnsickSKononenJWalkerRAzorsaDMMTGuanX-YSauterGKallioniemiO-PTrentJMeltzerP1997AlB1, a steroid receptor coactivator amplified in breast and ovarian cancer Science 277965968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ArmesJETruteLWhiteDSoutheyMCHammetFTesorieroAHutchinsAMDiteGSMcCredieMRGilesGGHopperJLVenterDJ1999Distinct molecular pathogeneses of early-onset breast cancers in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: a population-based study Cancer Res 5920112017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BerkeyCGardnerJDFrazierAColditzG2000Relation of childhood diet and body size to menarche and adolescent growth in girls Am J Epidemiol 152446452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BernsteinJThompsonWRischNHolfordT1992The genetic epidemiology of second primary breast cancer Am J Epidemiol 136937948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BernsteinLHendersonBHanischRSullivan-HalleyJRossR1994Physical exercise and reduced risk of breast cancer in young women J Natl Cancer Inst 8614031408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BishopDCannon-AlbrightLMcLellanTGardnerESkolnickM1988Segregation and linkage analysis of nine Utah breast cancer pedigrees Genetic Epidemiol 5151169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BrintonLHooverRFraumeniJJ1982Interaction of familial and hormonal risk factors for breast cancer J Natl Cancer Inst 69817822 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ChenPLPSellersTAPRichSSPPotterJDPFolsomARP1995Segregation analysis of breast cancer in a population-based sample of postmenopausal probands: The Iowa Women's Health Study Genetic Epidemiol 12401415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ClausERischNThompsonW1990Age at onset as an indicator of familial risk of breast cancer Am J Epidemiol 131961972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ClausERischNThompsonW1991Genetic analysis of breast cancer in the CASH study Am J Hum Genet 48232241 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CuiJAntoniouACDiteGSSoutheyMCVenterDJEastonDFGilesGGMcCredieMRHopperJL2001aAfter BRCA1 and BRCA2 – what next? multifactorial segregation analyses of three-generation, population-based Australian families affected by female breast cancer Am J Hum Genet 68420431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CuiJHopperJL2000Why are the majority of hereditary cases of early-onset breast cancer sporadic? A simulation study Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 9805812 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CuiJPAntoniouACPDiteGSPSoutheyMCPVenterDJPEastonDFPGilesGGPMcCredieMRPHopperJLP2001bAfter BRCA1 and BRCA2 – what next? multifactorial segregation analyses of three-generation, population-based Australian families affected by female breast cancer Am J Hum Genet 68420431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeapenDEscalanteAWeinribLHorowitzDBachmanBRoy-BurmanPWalkerAMackT1992A revised estimate of twin concordance in systemic lupus erythematosis Arthritis Rheum 35311318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EastonDFordDPetoJ1993Inherited susceptibility to breast cancer Cancer Surveys 1895113 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EbyNChang-ClaudeJBishopD1994Familial risk and genetic susceptibility for breast cancer Cancer Causes Control 5458470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EganKNewcombPLongneckerMTrentham-DietzABaronJTrichopoulosDStampferMWillettW1996Jewish religion and risk of breast cancer Lancet 34716451646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EkbomAErlandssonGHsiehC-CTrichopolousDAdamiH-OCnattingiusS2000Risk of breast cancer in prematurely born women J Natl Cancer Inst 92840841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EkbomAHsiehCLipworthLAdamiH-OTrichopoulosD1997Intrauterine environment and breast cancer risk in women: a population-based study J Natl Cancer Inst 897176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElwoodJ1973Changes in the twinning rate in Canada 1926-70 Brit J Prev Soc Med 27236241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FeigelsonHRossRYuMCoetzeeGReichardtJHendersonB1996Genetic susceptibility to cancer from exogenous and endogenous exposures J Cell BiochemSuppl 251522 [DOI] [PubMed]

- FodorFWestonABleiweissIMcCurdyLWalshMTartterPBrowerSEngC1998Frequency and carrier risk associated with common BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish breast cancer patients Am J Hum Genet 634551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FordDEastonDPetoJ1995Estimates of the gene frequency of BRCA1 and its contribution to breast and ovarian cancer incidence Am J Hum Genet 5714571462 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FordDEastonDFStrattonMNarodSGoldgarDDevileePet al1998Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium Am J Hum Genet 62676689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GaudetteL1992CanadaInCancer Incidence in Five ContinentsParkin D, Muir C, Whelan S, Gao Y-T, Ferlay J, Powell J (eds),Vol. VILyon: IARC Scientific Publications [Google Scholar]

- HaberD2000BRCA1: an emerging role in the cellular response to DNA damage Lancet 35520902091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HankeyBBrintonLKesslerLAbramsJ1993BreastInSEER Cancer Statistics Review 1973-1990Miller B, Ries L, Hankey B, Kosary K, Harras A, Devesa S, Edwards B (eds), Vol. Publication 93-2789.pp. IV-1-24.Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute [Google Scholar]

- HankeyBPercyC1992USA: the ‘SEER’ Program.InCancer Incidence in Five ContinentsParkin D, Muir C, Whelan S, Gao Y-T, Ferlay J, Powell J (eds),Vol. VILyon: IARC Scientific Publications [Google Scholar]

- HarvellDStreckerTTochacekMXieBPenningtonKMcCombRRoySShullJ2000Rat strain-specific actions of 17b-estradiol in the mammary gland: correlation between estrogen-induced lobuloalveolar hyperplasia and susceptibility to estrogen-induced mammary cancers Proc Natl Acad Sci 9727792784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HarveyEBrintonL1985Second cancer following cancer of the breast in Connecticut Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 6899112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HendersonBFeigelsonH2000Hormonal carcinogenesis Carcinogenesis 21427433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HislopTElwoodJColdmanASpinelliJWorthAEllisonL1984Second primary cancers of the breast: Incidence and risk factors Br J Cancer 497985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HopperJLSoutheyMCDiteGSJolleyDJGilesGGMcCredieMREastonDFVenterDJ1999Population-based estimate of the average age-specific cumulative risk of breast cancer for a defined set of protein-truncating mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Australian Breast Cancer Family Study Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 8741747 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HoulstonRMcCarterEParbhooSScurrJSlackJ1992Family history and risk of breast cancer J Med Genet 29154157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IseliusLSlackJLittlerMMortonN1991Genetic epidemiology of breast cancer in Britain Ann Hum Genet 55151159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JeanneretOMacMahonB1962Secular changes in rates of multiple births in the United States Am J Hum Genet 14410425 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KasrielJEavesL1976The zygosity of twins: further evidence of the agreement between diagnosis by blood groups and written questionnaires J Biosoc Sco 8263266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KleinmanJFowlerMKesselS1991Comparison of infant mortality among twins and singletons: United States 1960 and 1983 Am J Epidemiol 133133143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KumarDGemayelNDeapenDKapadiaDYamashitaPDwyerJRoy-BurmanPBrayGMackT1993North-American twins with IDDM:genetic, etiological, and clinical significance of disease concordance according to age, zygosity, and the interval after diagnosis in the first twins Diabetes 4213511363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LakhaniSR1999The pathology of familial breast cancer Morphological aspects Breast Cancer Res 13135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LakhaniSRGustersonBAJacquemierJSloaneJPAndersonTJvan de VijverMJVenterDFreemanAAntoniouAMcGuffogLSmythESteelCMHaitesNScottRJGoldgarDNeuhausenSDalyPAOrmistonWMcManusRScherneckSPonderBAFutrealPAPetoJStoppa-LyonnetDBignonYJStrattonMR2000The pathology of familial breast cancer: histological features of cancers in families not attributable to mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 Clin Cancer Res 6782789 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LichtensteinPHolmNVerkasaloPIliadouAKaprioJKoskenvuoMPukkalaESkytteAHemminkiK2000Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer New Engl J Med 3437885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MackTBerkelJBernsteinLMackW1985Religion and cancer in Los Angeles County Natl Inst Cancer monograph 69235245 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MackTMDeapenDHamiltonAS2000Representativeness of a roster of volunteer North American twins with chronic disease Twin Research 33342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MillerABulbrookR1986UICC multidisciplinary project on breast cancer: the epidemiology, aetiology, and prevention of breast cancer Int J Cancer 37173177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NewmanBAustinMALeeMKingMC1988Inheritance of human breast cancer: evidence for autosomal dominant transmission in high-risk families Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 8530443048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OlsenJHSeersholmNBoiceJrJDKruger KjaerSFraumeniJrJF1999Cancer risk in close relatives of women with early-onset breast cancer–a population-based incidence study Br J Cancer 79673679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ParkinDMuirCWhelanSGaoY-TFerlayJPowellJ1992Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Vol. VILyon: IARC Scientific Publications [Google Scholar]

- PercyCVan HoltenVMuirC1990International Classification of Disease of Oncology Geneva: World Health Organization

- PetoJCollinsNBarfootRSealSWarrenWRahmanNEastonDFEvansCDeaconJStrattonMR1999Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations in patients with early-onset breast cancer[see comments]J Natl Cancer Inst 91943949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PetoJMackT2000High constant incidence in twins and other relatives of women with breast cancer Nat Genet 26411414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PharoahPDDayNEDuffySEastonDFPonderBA1997Family history and the risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis Int J Cancer 71800809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PhillipsKA2000Immunophenotypic and pathologic differences between BRCA1 and BRCA2 hereditary breast cancers J Clin Oncol 181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PriorPWaterhouseJ1978Incidence of bilateral tumors in a population-based series of breast cancer patients. I. Two approaches to an epidemiological analysis Br J Cancer 37620634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RischN2001The Genetic Epidemiology of Cancer: Interpreting Family and Twin Studies and Their Implications for Molecular Genetic Approaches Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prevent 10733741 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RobbinsGBergJ1964Bilateral primary breast cancers Cancer 1715011527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RowellSNewmanBBoydJKingM-C1994Inherited predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer Am J Hum Genet 55861865 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ShimizuHRossRBernsteinLYataniRHendersonBMackT1991Cancers of the prostate and breast among Japanese and white immigrants in Los Angeles County Br J Cancer 63963966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ShuXJinFDaiQWenWPotterJKushiLRuanZGaoY-TZhengW2001Soyfood intake during adolescence and subsequent risk of breast cancer among Chinese women Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prevent 10483488 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ShullJSpadyTSnyderMJohanssonSPenningtonK1997Ovary-intact, but not ovariectomized female ACI rats treated with 17β-estradiol rapidly develop mammary carcinoma Carcinogenesis 1815951601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics NCfH(All years) Vital Statistics of the United States: Rockville MD

- StormHJensenO1986Risk of contralateral breast cancer in Denmark Br J Cancer 54483492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SwiftMReitnauerPMorrelDChaseC1987Breast and other cancers in families with ataxia-telangectasia N Engl J Med 31612891294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ThompsonW1994Genetic epidemiology of breast cancer Cancer 74279287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TorgersenS1979The determination of twin zygosity by means of a mailed questionnaire Acta Genet Med Gemellol 28225236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TuliniusHSigvaldasonHOlafsdottirGTryggvadottirL1992Epidemiology of breast cancer in families in Iceland J Med Genet 29158164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UrsinGHendersonBEHaileRWPikeMCZhouNDiepABernsteinL1997Does oral contraceptive use increase the risk of breast cancer in women with BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations more than in other women? Cancer Res 5736783681 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WarnerEFoulkesWGoodwinPMeschinoWBlondalJPatersonCOzcelikHGossPAllingham-HawkinsDHamelNDi ProsperoLContigaVSerruyaCKleinMRMHoneyfordJLiedeAGlendonGBrunetJNarodS1999Prevalence and penetrance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations in unselected Ashkenazi Jewish women with breast cancer J Natl Cancer Inst 9112411247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WillettW1997Fat, energy, and breast cancer J Nutr 127921S923S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WilliamsWAndersonD1984Genetic epidemiology of breast cancer: segregaton analysis of 200 Danish pedigrees Genetic Epidemiol 1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]