Abstract

A bigenic MUC1.Tg/MIN mouse model was developed by crossing Apc/MIN/+ (MIN) mice with human MUC1 transgenic mice to evaluate MUC1 antigen-specific immunotherapy of intestinal adenomas. The MUC1.Tg/MIN mice developed adenomas at a rate comparable to that of MIN mice and had similar levels of serum MUC1 antigen. A MUC1-based vaccine consisting of MHC class I-restricted MUC1 peptides, a MHC class II-restricted pan-helper peptide, unmethylated CpG oligodeoxynucleotide and GM-CSF caused flattening of adenomas and significantly reduced the number of large adenomas. Immunization was successful in generating a MUC1-directed immune response evidenced by increased MUC1 peptide-specific anti-tumor cytotoxicity and IFN-γ secretion by lymphocytes.

Keywords: MUC1.Tg/MIN mice, adenoma, immunotherapy

1. INTRODUCTION

The ability of the ApcMIN/+(MIN) mouse to develop spontaneous adenomatous polyps has made it a useful model for studying colon tumorigenesis. Because the current methods for treating established gastrointestinal cancer have met with limited success, recent efforts have shifted to chemoprevention as the primary strategy for reducing the risk of colon cancer. These efforts have led to the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) that target the pro-inflammatory enzyme, COX-2, whose expression is increased in adenomas and colon carcinoma [1–5]. Although these agents have been shown to cause a dose-dependent reduction in the size and frequency of intestinal polyps in APC-deficient MIN mice [1, 6, 7] and in humans harboring the familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) mutation [8,9], cessation of drug therapy is accompanied by re-emergence of polyps [8] with potential to progress to frank carcinoma. An immunologically-based intervention that targets tumor-associated antigens such as MUC1 that are over expressed in adenomas could potentially be useful in controlling adenomas and in stimulating memory responses capable of preventing disease recurrence.

MUC1 is a highly glycosylated, epithelial cell-associated mucin that is expressed in a polarized fashion on the apical surfaces of ducts and glands. Unlike normal epithelium, MUC1 is found throughout the tumor mass and is broadly expressed on the tumor surface in the underglycosylated form [10]. Increased expression of underglycosylated MUC1 has been documented in adenomatous polyps as well as colorectal adenocarcinomas [11–13]. Underglycosylation of MUC1 leads to exposure of cryptic epitopes that can be recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) [14,15]. Although MUC1 is a self protein, immune responses against MUC1, as manifested by the presence of antibodies and CTL, have been reported in some patients with breast, ovarian and colon cancer [14]. Furthermore, studies of MUC1-expressing transgenic mice have demonstrated the presence of MUC1-specific CTLs that can kill MUC1-expressing tumor cells in vitro and suppress tumor growth in vivo [16–19]. Taken together, these observations suggest that mobilization of an immune response against MUC1 could potentially be useful in treating adenomas without associated toxicity and could result in the acquisition of long-term immunity.

In this report we describe the generation of a double transgenic mouse that spontaneously develops adenomas and expresses human MUC1 as a self antigen. These mice were generated by crossing male MIN mice that develop multiple intestinal adenomas [20] with female MUC1 transgenic mice. We demonstrate that these bigenic mice develop adenomas at a rate that is comparable to wild type MIN mice, express MUC1 preferentially in neoplastic regions of the small intestine and secrete MUC1 antigen that is detectable in the serum. We also show for the first time that vaccination with a cocktail consisting of MHC class I-restricted MUC1 tandem repeat peptides, a class II pan helper peptide, and the biologic adjuvants CpG-ODN and GM-CSF leads to a flattening of adenomas and a reduction in the frequency of very large-sized adenomas. This animal model could be useful for evaluating the efficacy of immunotherapy-based strategies in treating polyposis.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Mice

MIN (C57BL/6J-ApcMIN/+) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). MUC1 transgenic (C57BL/6-MUC1.Tg) mice were developed in our laboratory as previously described [21]. Mice that spontaneously develop MUC1-expressing adenomas (MUC1.Tg/MIN) were obtained by crossing female MUC1.Tg mice with male MIN mice. Mice were bred and maintained in microisolator cages under specific pathogen–free conditions at the University of Arizona Animal Care Facility in accordance with the Principles of Animal Care (NIH publication No. 85-23) and guidelines for humane treatment of animals were followed as approved by the University of Arizona Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Genotyping

The MUC1 and Apc/MIN/+ allele-specific PCR was performed as described previously [21,22].

2.3. Adenoma Enumeration and Classification

Mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation and the colon and small intestine were excised. The small intestine was divided into three segments comprised of proximal, medial and distal regions. The sections were rinsed with sterile PBS fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h and then transferred to 70% ethanol. The adenomas were then counted under a dissecting microscope (Model SZ3060, Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA) at 20X magnification. The location and diameter of each adenoma were recorded with a millimeter scale placed on the screen. The adenomas were classified as very small (0.1≤1.0mm), small (1.0mm ≤2.0mm), medium (2.0mm≤3.0mm) and large (>3.0mm).

2.4. Immunoblotting

Lysates of normal and adenomatous tissues were prepared in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1% Triton X-100). After 20 min incubation at 4°C, lysates were centrifuged at 1000×g (4°C) for 5 min to remove cell debris. Supernatants were transferred to fresh tubes and stored at −20°C. Protein content of lysates was determined using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with BSA as a standard. Cell lysates were resolved on 5% denaturing polyacrylamide gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes electrophoretically and blocked in 5% dry milk in PBST (PBS, 0.01% Tween 20) overnight. The membrane was then incubated (1 h, 25°C) with either isotype control antibody or the B27.29 antibody that recognizes the human MUC1 tandem repeat sequences but is not reactive with the mouse Muc1 protein [23]. Both antibodies were diluted at 2 µg/mL in blocking solution. Following three 10 min washes with PBST, the membrane was incubated for 1 h at 25°C with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2000 in PBST) (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA) and detection was performed using ECL (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ).

2.5. Synthetic Peptides and Reagents

Two MUC1 TR MHC class I-restricted peptides (APGSTAPPA and SAPDTRPAP) and one hepatitis B core antigen helper peptide (TPPAYRPPNAPIL) were used in the study. The peptides were synthesized by the Mayo Clinic Peptide Synthesis Facility on an automated 433A Peptide Synthesizer (ABI, Foster City, CA) using solid-phase peptide synthesis with orthogonally protected 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) amino acids and Rink resins. The peptides were purified by preparative reversed phase HPLC on a C-18 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) and verified for their correctness by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (MSQ System, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA).

2.6. Peptide Immunization

The complete (peptide) vaccine cocktail consisted of two MHC class I-restricted MUC1 tandem repeat peptides [18,24], a class II pan helper peptide [25], and the biologic adjuvants CpG-ODN and GM-CSF, all admixed in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). MUC1.Tg/MIN, or MIN mice were divided into two groups and received three bi-weekly vaccinations using either one of two vaccines: a) a peptide-based vaccine that contained 100 µg of each MUC1 peptide (APGSTAPPA , SAPDTRPAP), 140 µg of the hepatitis B core antigen pan helper peptide (TPPAYRPPNAPIL) combined with 100 µg CpG-ODN 1826 (TCCATGACGTTCC TGACGTT) (Coley Pharmaceutical Group, Wellesley, MA) and 10,000 Units GM-CSF (Peprotec, Rocky Hill, NJ) in 100 µL PBS, or b) a non-peptide-based vaccine which contained 100 µg CpG-ODN and 10,000 Units GM-CSF in 100 µL PBS. The vaccine cocktails (100 µL) were each mixed with 100 µL of IFA (Sigma) by vortexing vigorously for 10 min. Immunizations were started on day 66 by injecting a total of 200 µL/mouse (100 µL subcutaneously into each flank) and were repeated every two weeks for a total of three immunizations. Only these two experimental groups (peptide vaccine, non-peptide vaccine) were selected for these studies because initial experiments demonstrated that the peptide-based vaccine which contained all three components (peptides, CpG-ODN, GM-CSF) was the most effective at suppressing the growth of transplanted MUC1-expressing colon cancer cells (MC38.MUC1) in MUC1.Tg mice [24]. All mice were sacrificed on day 110 and evaluated. Spleens, sera, small intestines and colons were isolated and processed for further study.

2.7. Immunohistochemistry and Histology

To evaluate MUC1 expression, tumors and normal tissues were fixed in methacarn (60% methanol, 30% chloroform, 10% glacial acetic acid), paraffin embedded, and sectioned for immunohistochemical analysis as previously described [16, 17]. In a separate experiment, following enumeration of the adenomas, the intestinal segments were formalin fixed and individual tumors were excised from each segment and placed in cassettes with sponges to maintain orientation. The intestinal tissue with the tumor masses were paraffin embedded on edge to allow sagittal sectioning of the tumor. Five micron sections of each mass were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and evaluated by a veterinary pathologist in accord with a previously published classification system [26].

2.8. MUC1 Antigen and anti-MUC1 Antibody Determination

Serum was collected via the retro-orbital plexus and the presence of circulating MUC1 antigen and anti-MUC1 antibodies were determined by ELISA as previously described [21,27].

2.9. Cytokine Production Assay

Splenocytes were isolated from vaccinated mice and incubated in 6 well plates at a density of 1×106 cells/mL with the MUC1 TR peptides and the hepatitis B virus core antigen pan helper peptide, each at 20 ng/mL for 48 h as previously described [16]. The supernatants were harvested and analyzed for the presence of IFN-γ by ELISA (Pierce Endogen, Rockford IL).

2.10. Cytotoxicity Assay

Single cell suspensions of splenocytes from 3 mice per group were pooled and stimulated in vitro with the MUC1 TR peptides (APGSTAPPA, SAPDTRPAP) and the hepatitis B virus core antigen pan helper peptide (TPPAYRPPNAPIL), each at 20 ng/mL, in the presence of 100 U/mL IL-2 for six days. Media, peptides and IL-2 were replenished on Day 3. Cytolytic activity was assessed on day 6 using 51Cr-labeled MUC1-expressing murine colon carcinoma cells (MC38.MUC1) [28] as targets. Mock-transduced cells (MC38.neo), not expressing MUC1, were labeled with 51Cr and used as negative control targets. Approximately 1×106 effector cells per well were plated in a 96 well U-bottom microtiter plate containing 1×104 51Cr-labeled MC38.MUC1 or MC38.neo tumor cells per well. Microtiter plates were centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 min, and then incubated at 37°C for 6 h. At the end of the incubation period, a 100 µL aliquot of the supernatant fluid was removed from each well, and the released 51Cr (experimental) was quantified using a Beckman LS6500 scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter, Inc. Fullerton, CA). The total 51Cr amount incorporated in tumor cells was determined by lysing 1×104 51Cr-labeled cells with Triton-X 100 (total) and counting a 100µL aliquot. Spontaneous 51Cr release was measured by counting 100µl of 1×104 51Cr-labeled cells that were incubated with media alone (spontaneous). The percentage of specific tumor cell lysis was calculated using the following formula: %Cytotoxicity=[(experimental) − (spontaneous)]/[(total) − (spontaneous)]×100. Spontaneous release did not exceed 10%.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Sizes and numbers of adenomas were evaluated using Poisson regression to analyze the difference between peptide- and non-peptide-based vaccination. IFN-γ data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank non-parametric test. The cytotoxicity data were analyzed using Student’s t-test. The difference between data sets was considered statistically significant at the level p<0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Formation of Adenomas in MUC1.Tg/MIN Mice

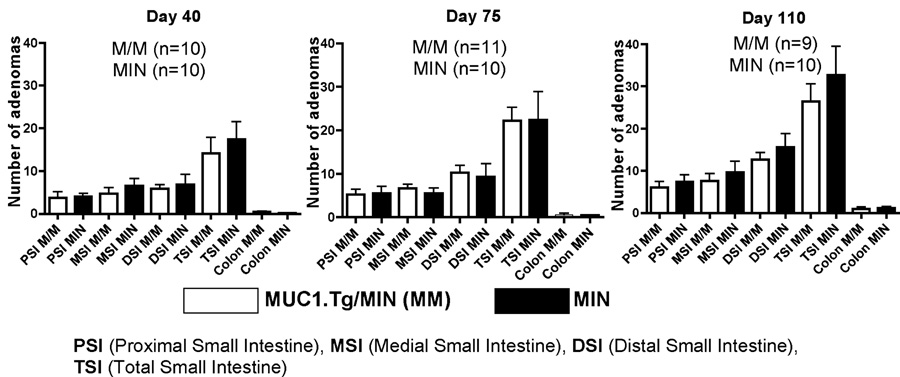

In initial studies assessed the impact of MUC1 gene expression on adenoma formation in the MUC1.Tg/MIN mice. For this purpose, the incidence of adenomas in a group of MIN and MUC1.Tg/MIN transgenic mice were evaluated by removing the intestines and counting the number of polyps on days 40, 75 and 110 as described in “Materials and Method”. The data (Figure 1) revealed a comparable and progressive increase in the numbers and distribution of adenomas in the intestine and colon in both groups of mice with age. By day 110, the average total number of adenomas in MIN and MUC1.Tg/MIN mice were 33.9±22.9 and 27.5±13.8 respectively. The colons of both mice had the fewest number of adenomas (range of 0–4 per mouse).

Figure 1. Incidence of adenomas in intestines of MUC1.Tg/MIN (M/M) and MIN mice.

Mice were sacrificed on either day 40, day 75, or day 110 and intestines were dissected and adenomatous polyps were counted. M/M mice: Day 40, n=10; Day 75, n=11; Day 110, n=9. MIN mice: Day 40, n = 10; Day 75, n = 10; Day 110, n = 10.

3.2. MUC1 Expression in MUC1.Tg/MIN Mice

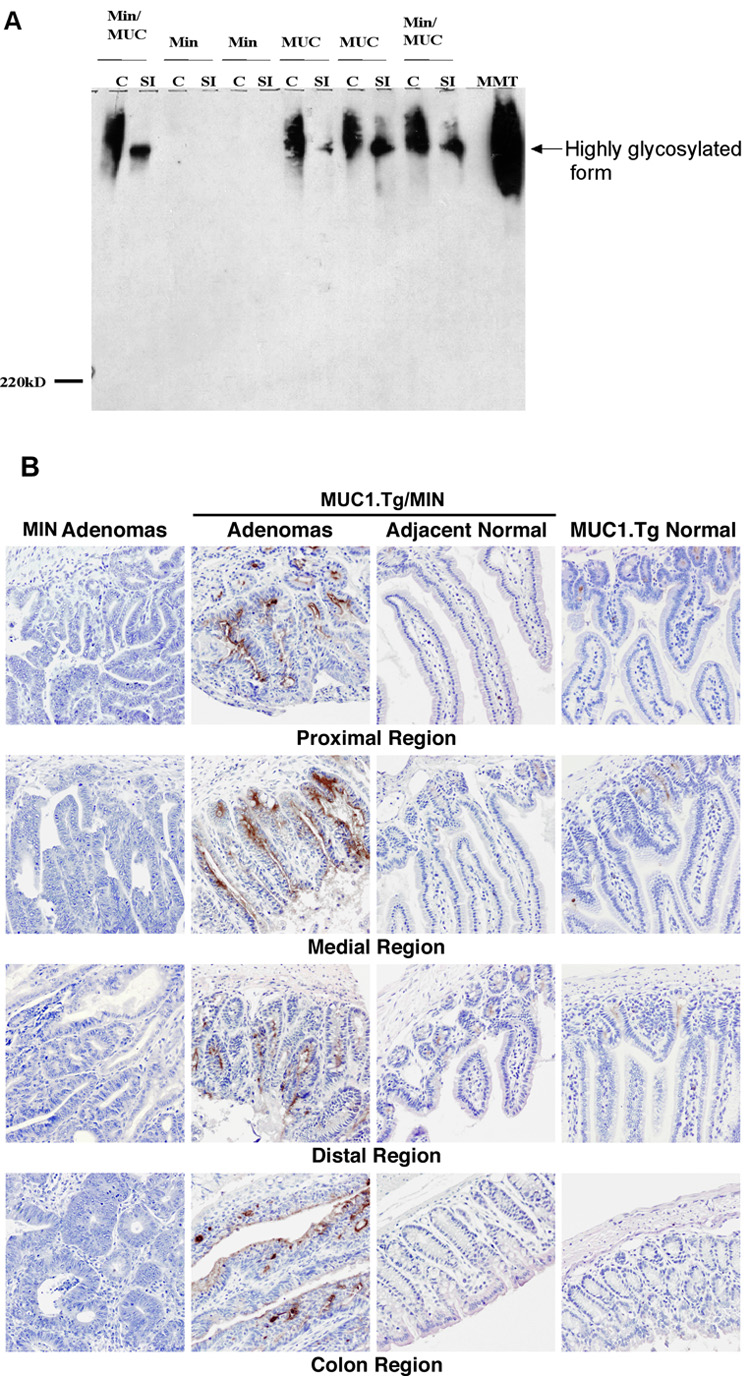

Next we evaluated the expression of MUC1 protein in the small intestine and colon tissue from MUC1.Tg/MIN, MUC1.Tg and MIN mice. Tissue lysates were prepared for western blot analysis. The lysates were stained with the B27.29 monoclonal antibody that recognizes the tandem repeat (TR) domains of human MUC1. The data (Figure 2A) reveal presence of MUC1 protein in the small intestine and colonic tissues of MUC1.Tg and MUC1.Tg/MIN mice but not in MIN mice. The two tissues appear to glycosylate MUC1 differently, as the bands, which are diffuse due to high levels of glycosylation, show different mobilities. Detection of MUC1 using the B27.29 antibody is not quantitative, as there are multiple epitopes on MUC1. The B27.29 epitope has been shown to map to two separate parts of the MUC1 glycopeptide, the core peptide spanning the PDTRP sequence and a second carbohydrate epitope attached to a T and S elsewhere in the tandem repeat [29]. To further assess the location of MUC1 protein expression in these mice, gastro-intestinal (GI) tissues were isolated from MUC1.Tg/MIN and MIN mice and immunohistochemically stained with the B27.29 monoclonal antibody. The data (Figure 2B) demonstrate MUC1 expression in adenomas from MUC1.Tg/MIN mice but not in adenomas from MIN mice. Detailed examination of GI tract tissue from MUC1.Tg/MIN mice revealed greater MUC1 staining in the neoplastic regions which comprised most of the GI tract compared to the few adjacent non-adenomatous regions of the intestines (Figure 2B middle panels). Expression of MUC1 in the intestines of the MUC1.Tg mice (Figure 2B right panels) appeared similar to the adjacent normal tissues in the MUC1.Tg/MIN mice.

Figure 2. Detection of human MUC1 protein in intestines.

(A) Western blot analysis of human MUC1 protein in intestines. Lysates were prepared from colons (C) or small intestines (SI) of 110 day-old MUC1.Tg (MUC), MIN, and MUC1.Tg/MIN (Min/MUC) mice. Equal quantities of each sample (100 µg) were separated on a 5% SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to PVDF membrane and tested for reactivity with the anti-human MUC1 monoclonal antibody B27.29. MMT is a positive control for human MUC1 and is indicative of the highly glycosylated isoform of MUC1. (B) Immunohistochemical (IHC) detection of human MUC1 protein in intestines of MUC1.Tg, MIN, and MUC1.Tg/MIN mice. Specimens were obtained from intestines of 110 day-old animals and histological sections were prepared. Human MUC1 was detected by immune staining with the antihuman MUC1 monoclonal antibody B27.29. IHC demonstrates preferential MUC1 staining in adenomatous polyps, compared to non-adenomatous regions of the intestine (middle panels) or to similar regions of the MUC1.Tg mouse (right panels). MUC1 staining was not observed in polyps from MIN mice (left panels). IHC images were collected at 200X magnification. This figure is representative of at least 3 mice that were evaluated.

3.3. Serum Levels of MUC1

Having shown that MUC1 protein was expressed in adenomas of MUC1.Tg/MIN mice, we then evaluated the serum for the presence of circulating MUC1 antigen. Mice were bled and serum was collected from individual mice and assessed for the presence of MUC1 antigen by ELISA. The data revealed high levels of MUC1 antigen in the sera of MUC1.Tg/MIN (mean range, 274–722 units/mL) and MUC1 mice (mean range, 592–668 units/mL). Not surprisingly, serum MUC1 antigen was not detected in the MIN mice. Sera from mice of both transgenic groups (MUC1.Tg, MUC1.Tg/MIN) were also tested for the presence of MUC1 antibodies that bind to a 40-residue synthetic peptide corresponding to two copies of the TR as evidence of an induced humoral immune response. Neither MUC1 nor MUC1.Tg/MIN mice developed significant levels above background of anti-MUC1 antibody (data not shown).

3.4. Effect of Peptide Vaccination on Adenoma Formation in MUC1.Tg/MIN Mice

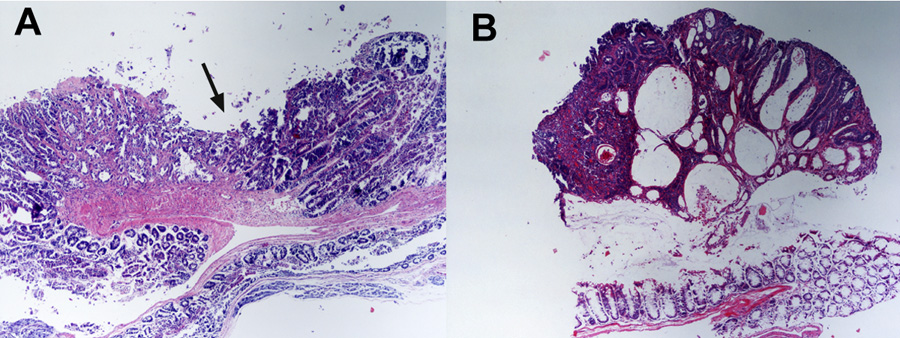

The vaccine regimen that was selected for this study was based on our recent findings [24] in which we demonstrated that the combination of MUC1 peptides, MHC class II pan helper peptide, CpG-ODN and GM-CSF was the most effective regimen in suppressing the growth of transplantable MUC1-expressing MC38 colon cancer in MUC1-Tg mice. The MHC class I peptides confer MUC1 specificity leading to the induction of CTL-mediated anti-tumor responses; the Hepatitis B core antigen-derived MHC class II pan T helper peptide was included to boost CD8+ anti-tumor responses [30,31]; CpG-ODN was included to promote DC activation via its interaction with Toll-like receptor (TLR)-9 [32,33] to enhance CTL responses, expansion and survival [33–37]. GM-CSF promotes antigen presentation and DC recruitment to vaccine sites [38–41] and is commonly used as a biological adjuvant in pre-clinical and clinical immunotherapy studies [42,43]. In separate experiments, groups of MUC1.Tg/MIN and MIN mice were immunized with the peptide-based vaccine (peptides + CpG-ODN + GM-CSF) or the non-peptide-based vaccine (CpG-ODN + GM-CSF) on day 66 when the mice harbored large numbers of adenomas. At the time of sacrifice (day 110), there was a significant reduction in the total number of adenomas in the proximal (p=0.014) and the medial (p=0.019) regions of the GI tract of the mice treated with the peptide-based vaccine (Table 1A). This reduction was largely due to reduced numbers of small adenomas (1.1≤2mm) in both the proximal (p=0.03) and the medial (p=0.02) regions of the peptide vaccinated mice compared to the mice receiving the non-peptide based vaccine (Table 1B). Although, there was a statistical increase in the number of very small adenomas (0≤1) in the distal region (p=0.001) of the peptide vaccine-treated mice compared to non-peptide-based vaccine-treated mice, this did not translate into a significant difference in the overall number of adenomas in this region (p=0.112). The total number of adenomas in the peptide-treated group was only slightly less (55.6±6.8) than the number in the non-peptide-treated group (61.3±6.8). Since the MIN mouse carries a germ-line mutation of the murine APC gene, it is unlikely that loss of APC expression is a factor in the differential regional reduction of adenomas in this mouse model. A significant observation was that the adenomas in the peptide-treated animals attained a more flattened discoid growth with an indented center area that was either eroded or necrotic (Figure 3A) while the vast majority of adenomas (~90%) in the mice that were immunized with the non-peptide based vaccine had a raised appearance (Figure 3B) and caused some blockage in the intestinal lumen. Sections of the adenomatous masses from the peptide-treated MUC1.Tg/MIN mice showed that the mucosal cells formed disorganized villus-like structures with few or no cystic spaces. The villus structures were lined by well-differentiated mucosal epithelial cells. These masses had a wide base attachment to the mucosa and there was minimal inflammation present in the stroma of the mass lesions.

Table 1.

| Table 1A. Incidence of adenomas in intestinal sections of vaccinated MUC1.Tg/MIN mice. Intestines of mice that received peptide or non-peptide-based vaccines were isolated and dissected into four segments:, proximal, medial, distal and the colon. Adenomas were enumerated as described in “Materials and Methods”. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Number of Adenomas per intestinal Region (SEM) | ||

| Peptide Vaccine (n=11) | Non-Peptide vaccine (n=9) | P value | |

| Proximal | 12.2 (2.1) | 16.3 (3.4) | 0.014 |

| Medial | 15.4 (2.0) | 19.8 (2.7) | 0.019 |

| Distal | 25.4 (4.8) | 22.2 (2.7) | 0.112 |

| Colon | 2.6 (0.4) | 2.7 (0.9) | 0.967 |

| Total | 55.6 (6.8) | 61.3 (6.8) | 0.092 |

| Table 1B. Incidence of numbers and sizes of adenomas within the regions of intestinal sections of vaccinated MUC1.Tg/MIN mice. Adenomas within each region of both peptide and non-peptide vaccinated mice were enumerated and grouped according to size in mm. The peptide treated mice had significantly fewer small (1≤2mm) adenomas in the proximal and medial regions than the non-peptide-vaccinated mice. Differences in numbers of adenomas in each size category and region were compared between the peptide vaccine and the non-peptide vaccine-treated groups using Poisson regression (p value for each comparison is noted in parentheses) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size interval, Diameter (mm) | Number and Sizes of Adenomas per Region in MUC1.Tg/MIN Mice | |||||||||

| Peptide Vaccine, n=11 (P value) | Non-Peptide Vaccine, n=9 (P value) | |||||||||

| Prox | Med | Dist | Colon | Total | Prox | Med | Dist | Colon | Total | |

| 0.1≤1 | 1.4 (0.06) | 2.3 (0.18) | 5.0 (0.0001) | 0.6 (0.24) | 9.2 (0.04) | 2.6 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 6.6 |

| 1.1≤2 | 5.1 (0.03) | 6.3 (0.02) | 10.3 (0.97) | 0.4 (0.57) | 22.0 (0.02) | 7.6 | 9.2 | 10.2 | 0.2 | 27.2 |

| 2.1≤3 | 3.6 (0.36) | 5.3 (0.07) | 7.7 (0.43) | 0.7 (0.87) | 17.4 (0.87) | 2.9 | 7.3 | 6.8 | 0.7 | 17.7 |

| >3.1 | 2.1 (0.09) | 1.6 (0.69) | 2.6 (0.12) | 1.0 (0.63) | 7.0 (0.03) | 3.3 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 9.9 |

| Total | 12.2 (0.014) | 15.4 (0.019) | 25.4 (0.112) | 2.6 (0.967) | 55.6 (0.09) | 16.3 | 19.8 | 22.2 | 2.7 | 61.3 |

Figure 3. Comparison of adenoma morphology.

(A) Section of adenoma from peptide-vaccinated (peptides + CpG-ODN + GM-CSF) MUC1.Tg/MIN mouse. Arrow indicates the flattened, indented morphology. (B). Section of adenoma from non-peptide-vaccinated (CpG-ODN + GM-CSF) MUC1.Tg/MIN mouse showing polypoid morphology and multiple cystic spaces. These samples were representative of the response observed in mice from each group. All sections were stained with routine hematoxylin and eosin. Images were collected at 200X magnification.

3.5. Generation of MUC1 Immunity in Vaccinated Mice

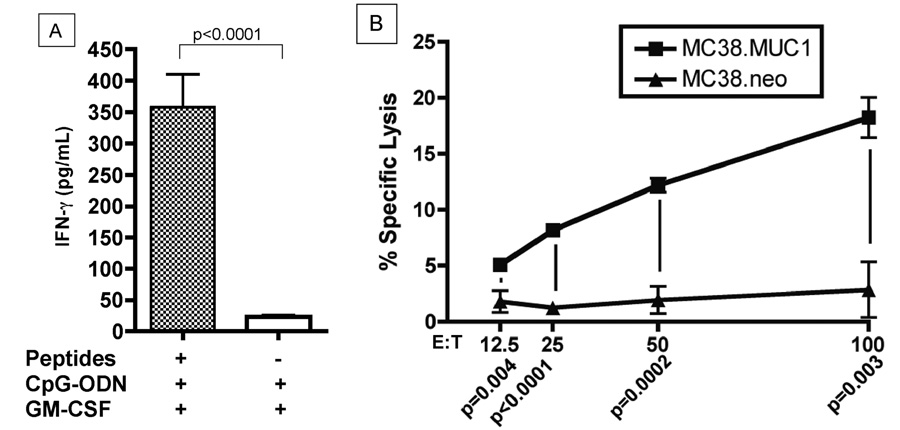

The existence of an anti-MUC1 immune response was evaluated in mice receiving the peptide-based vaccine in which a clinical response was observed. In a separate experiment, splenocytes were isolated from MUC1.Tg/MIN mice on day 110 (~2 weeks after the last vaccination) and assessed for IFN-γ secretion and tumoricidal activity against MUC1-expressing tumor cells (MC38.MUC1) after short-term (48h) in vitro re-stimulation with the MUC1 peptides. MUC1.Tg/MIN mice that were vaccinated with the peptide-based vaccine secreted significantly more IFN-γ (357.5±181.4 pg/mL) than MUC1.Tg/MIN mice vaccinated with the non-peptide-based vaccine (45.8±31.0 pg/mL) (p<0.001) (Figure 4A). Unstimulated splenocytes did not produce detectable levels of IFN-γ (data not shown). The increased IFN-γ production by splenocytes from the peptide-vaccinated mice was also correlated with in vitro cytolysis of MUC1-expressing tumor cells (Figure 4B). Of note is that analysis of sera from these mice revealed the absence of detectable anti-MUC1 antibodies (data not shown) suggesting that a cellular rather than a humoral immune response is elicited using this peptide-based vaccine cocktail.

Figure 4. Peptide-based vaccine elicits a MUC1-specific immune response.

(A) MUC1.Tg/MIN mice were vaccinated three times with either the peptide-based vaccine (peptides + CpG-ODN + GM-CSF) or the non-peptide vaccine (CpG-ODN + GM-CSF) at two week intervals. Splenocytes were then isolated and stimulated in vitro with the MUC1 TR peptides and the hepatitis B virus core antigen pan helper peptide for 48 h. Subsequently, supernatant was evaluated for IFN-γ production by ELISA. Splenocytes from individual mice from the peptide vaccine group (n=4) and the non-peptide vaccine group (n=3) were evaluated in triplicate. Data represent mean ± SD. (B) Cytolytic activity is MUC1-specific. Splenocytes from vaccinated MUC1.Tg/MIN mice were isolated and stimulated in vitro with the MUC1 TR peptides and the hepatitis B virus core antigen pan helper peptide for six days in the presence of 100 U/mL IL-2. Target cells were 51Cr-labeled MC38.MUC1 (murine colon carcinoma cell line expressing human MUC1) or MC38.neo (mock-transfected cell line not expressing human MUC1) plated at 5×104 cells/well. Effector to target cell ratios (E:T) and p values of statistical evaluations at each E:T ratio are indicated on the x-axis.

4. DISCUSSION

Apc/MIN/+ (MIN) mice are characterized by a mutation in the APC tumor suppressor gene that results in the development of multiple intestinal adenomas. Since these adenomas do not progress to invasive carcinoma, the MIN model is considered an appropriate model for studying human polyposis. In humans harboring the familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) mutation that develop multiple adenomas in the gastrointestinal tract, routine endoscopy and prophylactic colectomy are indicated to prevent the development of duodenal and colon cancers [44]. Despite these interventions, these patients have a significant risk of developing invasive duodenal adenocarcinoma. The inability of surgical and endoscopic interventions to control duodenal cancer has necessitated the use of COX-2 inhibitors to control tumor progression in this patient population [45]. The potential cardiotoxicity associated with prolonged use of high dose COX-2 inhibitors [46,47] warrants the development of new therapeutic modalities to treat the disease and prevent recurrence. In this respect, active immunotherapy, which targets tumor-associated antigens such as MUC1 that are over expressed in adenomas and colon cancer, can be considered a viable alternative. In this report, we have developed a novel bi-transgenic MUC1.Tg/MIN mouse model that develops multiple intestinal adenomas, which over-express the human MUC1 as a tumor-associated antigen. These mice were generated by crossing MIN mice with MUC1.Tg mice that express the human MUC1 transgene. The resulting MUC1.Tg/MIN mice develop adenomas at the same rate as MIN mice. Vaccination of MUC1.Tg/MIN mice with a cocktail consisting of two MHC class I-restricted MUC1 tandem repeat peptides (APGSTAPPA, SAPDTRPAP), the class II pan helper peptide (TPPAYRPPNAPIL), and the biologic adjuvants CpG-ODN (TCCATGACGTTCCTGACGTT) and GM-CSF, all admixed in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) caused flattening of adenomas in all regions of the intestine, reduced the numbers of adenomas in the proximal and medial regions of the intestine as well as the frequency of very large-sized adenomas that was not region-specific. The ability of the vaccine regimen to significantly reduce the number of adenomas in the proximal and medial intestine has implications for the prevention or treatment of recurrent duodenal polyps in FAP patients of which the MIN mouse is representative. Although endoscopic polypectomy has been shown to be somewhat effective in preventing the development of colon cancer in human FAP patients, these individuals have a high risk of developing recurrent duodenal polyps that may progress to invasive duodenal adenocarcinoma [Reviewed in 44]. Our findings suggest that this vaccine approach may prove effective in preventing or treating recurrent non-colonic adenomas in humans. The peptide-specific nature of the response elicited by the vaccine cocktail is suggested by the observed correlation of the clinical response with immunologic responses such as IFN-γ secretion and cytotoxicity of MUC1-expressing tumor cells by lymphocytes isolated from mice treated with the peptide-based vaccine but not with the non-peptide-based vaccine. Of interest in this study is that breaking tolerance to MUC1 occurred primarily in the cell-mediated compartment, as significant levels of anti-MUC1 antibodies were not detected in the vaccinated mice. Although some studies have showed induction of MUC1-specific antibodies in animal models and cancer patients [Reviewed in 10], our studies demonstrating the induction of CTL responses corroborate numerous reports in which CpG-ODN alone [33,37,48,49] or in combination with GM-CSF [24] were used as biologic adjuvants in peptide vaccines. A likely explanation of our results is that MHC class I-restricted MUC1 peptides which stimulate CD8+ T cells are acting in concert with CpG-ODN and GM-CSF in the vaccine cocktail to promote strong TH1 type responses resulting in the generation of efficient CTL anti-tumor responses [24,33,37,48,50]. In addition, inclusion of CpG-ODN in the vaccination cocktail in our study did not cause destruction of the lymphoid follicles or prevent isotype switching in treated mice (data not shown) as was reported by Heikenwalder, et al. [51]. A likely explanation why the CpG-ODN regimen used in our study was much better tolerated is that a lower dose was used (three injections every two weeks, a total dose of 300 µg/mouse) compared to the study by Heikenwalder et al. in which mice received daily CpG-ODN injections for up to 20 days (a total dose of 1200 µg/mouse). Furthermore, the discrepancy could be due to the differences in the model systems.

The ability of this peptide-based vaccine cocktail to reduce the frequency of proximal and medial adenomas has relevance to human polyposis in which duodenal cancer arising from pre-existing or recurrent duodenal adenomas is a major concern. This novel animal model could be potentially useful for testing immunologically based vaccines to control polyposis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the SPORE in Gastrointestinal Cancers grant NIH CA#95060 (E. Gerner, P.I.). We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of the following individuals: Kristi Wirths, Jose Padilla, Phil Namaguchi, Jane Criswell, Karen Blohm-Mangone and Terese L. Tinder. In addition, critical discussions with Dr. Douglas Lake were much appreciated.

The abbreviations used are

- MUC1

mucin

- MUC1.Tg

MUC1 transgenic

- CpG-ODN

unmethylated cytosine-guanine oligodeoxynucleotide

- GM-CSF

granulocytemacrophage colony stimulating factor

- IFA

incomplete Freund’s adjuvant

- MIN

multiple intestinal neoplasia

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oshima M, Dinchuk JE, Kargman SL, Oshima H, Hancock B, Kwong E, et al. Suppression of intestinal polyposis in Apc delta716 knockout mice by inhibition of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) Cell. 1996;87(5):803–809. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81988-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eberhart CE, Coffey RJ, Radhika A, Giardiello FM, Ferrenbach S, DuBois RN. Up-regulation of cyclooxygenase 2 gene expression in human colorectal adenomas and adenocarcinomas. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(4):1183–1188. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kargman SL, O'Neill GP, Vickers PJ, Evans JF, Mancini JA, Jothy S. Expression of prostaglandin G/H synthase-1 and -2 protein in human colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55(12):2556–2559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheehan KM, Sheahan K, O'Donoghue DP, MacSweeney F, Conroy RM, Fitzgerald DJ, et al. The relationship between cyclooxygenase-2 expression and colorectal cancer. Jama. 1999;282(13):1254–1257. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.13.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapple KS, Cartwright EJ, Hawcroft G, Tisbury A, Bonifer C, Scott N, et al. Localization of cyclooxygenase-2 in human sporadic colorectal adenomas. Am J Pathol. 2000;156(2):545–553. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacoby RF. The specific cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, celecoxib, caused adenoma regression in the APC mutant min mouse. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:A428. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oshima M, Murai N, Kargman S, Arguello M, Luk P, Kwong E, et al. Chemoprevention of intestinal polyposis in the Apcdelta716 mouse by rofecoxib, a specific cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2001;61(4):1733–1740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giardiello FM, Hamilton SR, Krush AJ, Piantadosi S, Hylind LM, Celano P, et al. Treatment of colonic and rectal adenomas with sulindac in familial adenomatous polyposis. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(18):1313–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305063281805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinbach G, Lynch PM, Phillips RK, Wallace MH, Hawk E, Gordon GB, et al. The effect of celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, in familial adenomatous polyposis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(26):1946–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006293422603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vlad AM, Kettel JC, Alajez NM, Carlos CA, Finn OJ. MUC1 immunobiology: from discovery to clinical applications. Adv Immunol. 2004;82:249–293. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)82006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamori S, Ota DM, Cleary KR, Shirotani K, Irimura T. MUC1 mucin expression as a marker of progression and metastasis of human colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1994;106(2):353–361. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90592-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldus SE, Monig SP, Hanisch FG, Zirbes TK, Flucke U, Oelert S, et al. Comparative evaluation of the prognostic value of MUC1, MUC2, sialyl-Lewis(a) and sialyl-Lewis(x) antigens in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Histopathology. 2002;40(5):440–449. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho SB, Ewing SL, Montgomery CK, Kim YS. Altered mucin core peptide immunoreactivity in the colon polyp-carcinoma sequence. Oncol Res. 1996;8(2):53–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnd DL, Lan MS, Metzgar RS, Finn OJ. Specific, major histocompatibility complex-unrestricted recognition of tumor-associated mucins by human cytotoxic T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(18):7159–7163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ioannides CG, Fisk B, Jerome KR, Irimura T, Wharton JT, Finn OJ. Cytotoxic T cells from ovarian malignant tumors can recognize polymorphic epithelial mucin core peptides. J Immunol. 1993;151(7):3693–3703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukherjee P, Ginardi AR, Madsen CS, Sterner CJ, Adriance MC, Tevethia MJ, et al. Mice with spontaneous pancreatic cancer naturally develop MUC-1-specific CTLs that eradicate tumors when adoptively transferred. J Immunol. 2000;165(6):3451–3460. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukherjee P, Ginardi AR, Madsen CS, Tinder TL, Jacobs F, Parker J, et al. MUC1-specific CTLs are non-functional within a pancreatic tumor microenvironment. Glycoconj J. 2001;18(11–12):931–942. doi: 10.1023/a:1022260711583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukherjee P, Ginardi AR, Tinder TL, Sterner CJ, Gendler SJ. MUC1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes eradicate tumors when adoptively transferred in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(3 suppl):848s–855s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukherjee P, Madsen CS, Ginardi AR, Tinder TL, Jacobs F, Parker J, et al. Mucin 1-specific immunotherapy in a mouse model of spontaneous breast cancer. J Immunother. 2003;26(1):47–62. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moser AR, Pitot HC, Dove WF. A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Science. 1990;247(4940):322–324. doi: 10.1126/science.2296722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowse GJ, Tempero RM, VanLith ML, Hollingsworth MA, Gendler SJ. Tolerance and immunity to MUC1 in a human MUC1 transgenic murine model. Cancer Res. 1998;58(2):315–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paulsen JE, Steffensen IL, Andreassen A, Vikse R, Alexander J. Neonatal exposure to the food mutagen 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine via breast milk or directly induces intestinal tumors in multiple intestinal neoplasia mice. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20(7):1277–1282. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.7.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price MR, Rye PD, Petrakou E, Murray A, Brady K, Imai S, et al. Summary report on the ISOBM TD-4 Workshop: analysis of 56 monoclonal antibodies against the MUC1 mucin. San Diego, Calif., November 17–23, 1996. Tumour Biol. 1998;19 Suppl 1:1–20. doi: 10.1159/000056500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukherjee P, Pathangey LB, Bradley JB, Tinder TL, Basu GD, Akporiaye ET, et al. MUC1-specific immune therapy generates a strong anti-tumor response in a MUC1-tolerant colon cancer model. Vaccine. 2007;25(9):1607–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franco A, Yokoyama T, Huynh D, Thomson C, Nathenson SG, Grey HM. Fine specificity and MHC restriction of trinitrophenyl-specific CTL. J Immunol. 1999;162(6):3388–3394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boivin GP, Washington K, Yang K, Ward JM, Pretlow TP, Russell R, et al. Pathology of mouse models of intestinal cancer: consensus report and recommendations. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(3):762–777. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddish MA, MacLean GD, Poppema S, Berg A, Longenecker BM. Pre-immunotherapy serum CA27.29 (MUC-1) mucin level and CD69+ lymphocytes correlate with effects of Theratope sialyl-Tn-KLH cancer vaccine in active specific immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1996;42(5):303–309. doi: 10.1007/s002620050287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen D, Xia J, Tanaka Y, Chen H, Koido S, Wernet O, et al. Immunotherapy of spontaneous mammary carcinoma with fusions of dendritic cells and mucin 1-positive carcinoma cells. Immunology. 2003;109(2):300–307. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grinstead JS, Koganty RR, Krantz MJ, Longenecker BM, Campbell AP. Effect of glycosylation on MUC1 humoral immune recognition: NMR studies of MUC1 glycopeptide-antibody interactions. Biochemistry. 2002;41(31):9946–9961. doi: 10.1021/bi012176z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ressing ME, van Driel WJ, Brandt RM, Kenter GG, de Jong JH, Bauknecht T, et al. Detection of T helper responses, but not of human papillomavirus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses, after peptide vaccination of patients with cervical carcinoma. J Immunother (1997) 2000;23(2):255–266. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200003000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weber JS, Hua FL, Spears L, Marty V, Kuniyoshi C, Celis E. A phase I trial of an HLA-A1 restricted MAGE-3 epitope peptide with incomplete Freund's adjuvant in patients with resected high-risk melanoma. J Immunother (1997) 1999;22(5):431–440. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199909000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jakob T, Walker PS, Krieg AM, von Stebut E, Udey MC, Vogel JC. Bacterial DNA and CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides activate cutaneous dendritic cells and induce IL-12 production: implications for the augmentation of Th1 responses. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1999;118(2–4):457–461. doi: 10.1159/000024163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davila E, Celis E. Repeated administration of cytosine-phosphorothiolated guanine-containing oligonucleotides together with peptide/protein immunization results in enhanced CTL responses with anti-tumor activity. J Immunol. 2000;165(1):539–547. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chu RS, Targoni OS, Krieg AM, Lehmann PV, Harding CV. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides act as adjuvants that switch on T helper 1 (Th1) immunity. J Exp Med. 1997;186(10):1623–1631. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho HJ, Takabayashi K, Cheng PM, Nguyen MD, Corr M, Tuck S, et al. Immunostimulatory DNA-based vaccines induce cytotoxic lymphocyte activity by a T-helper cell-independent mechanism. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18(5):509–514. doi: 10.1038/75365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warren TL, Bhatia SK, Acosta AM, Dahle CE, Ratliff TL, Krieg AM, et al. APC stimulated by CpG oligodeoxynucleotide enhance activation of MHC class I-restricted T cells. J Immunol. 2000;165(11):6244–6251. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nava-Parada P, Forni G, Knutson KL, Pease LR, Celis E. Peptide vaccine given with a Toll-like receptor agonist is effective for the treatment and prevention of spontaneous breast tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67(3):1326–1334. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwak LW, Young HA, Pennington RW, Weeks SD. Vaccination with syngeneic, lymphoma-derived immunoglobulin idiotype combined with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor primes mice for a protective T-cell response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(20):10972–10977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dranoff G. GM-CSF-secreting melanoma vaccines. Oncogene. 2003;22(20):3188–3192. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dranoff G, Jaffee E, Lazenby A, Golumbek P, Levitsky H, Brose K, et al. Vaccination with irradiated tumor cells engineered to secrete murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulates potent, specific, and long-lasting anti-tumor immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(8):3539–3543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas MC, Greten TF, Pardoll DM, Jaffee EM. Enhanced tumor protection by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor expression at the site of an allogeneic vaccine. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9(6):835–843. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.6-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Disis ML, Gooley TA, Rinn K, Davis D, Piepkorn M, Cheever MA, et al. Generation of T-cell immunity to the HER-2/neu protein after active immunization with HER-2/neu peptide-based vaccines. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(11):2624–2632. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.06.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaed SG, Klimek VM, Panageas KS, Musselli CM, Butterworth L, Hwu WJ, et al. T-cell responses against tyrosinase 368–376(370D) peptide in HLA*A0201+ melanoma patients: randomized trial comparing incomplete Freund's adjuvant, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and QS-21 as immunological adjuvants. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(5):967–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saurin JC, Chayvialle JA, Ponchon T. Management of duodenal adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis. Endoscopy. 1999;31(6):472–478. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phillips RK, Wallace MH, Lynch PM, Hawk E, Gordon GB, Saunders BP, et al. A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study of celecoxib, a selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor, on duodenal polyposis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 2002;50(6):857–860. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.6.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, Wittes J, Fowler R, Finn P, et al. Cardiovascular Risk Associated with Celecoxib in a Clinical Trial for Colorectal Adenoma Prevention. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1071–1080. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bertagnolli MM, Eagle CJ, Zauber AG, Redston M, Solomon SD, Kim K, et al. Celecoxib for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(9):873–884. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miconnet I, Koenig S, Speiser D, Krieg A, Guillaume P, Cerottini JC, et al. CpG are efficient adjuvants for specific CTL induction against tumor antigen-derived peptide. J Immunol. 2002;168(3):1212–1218. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baines J, Celis E. Immune-mediated tumor regression induced by CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(7):2693–2700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Speiser DE, Lienard D, Rufer N, Rubio-Godoy V, Rimoldi D, Lejeune F, et al. Rapid and strong human CD8+ T cell responses to vaccination with peptide, IFA, and CpG oligodeoxynucleotide 7909. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(3):739–746. doi: 10.1172/JCI23373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heikenwalder M, Polymenidou M, Junt T, Sigurdson C, Wagner H, Akira S, et al. Lymphoid follicle destruction and immunosuppression after repeated CpG oligodeoxynucleotide administration. Nat Med. 2004;10(2):187–192. doi: 10.1038/nm987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]