Abstract

Short peptides corresponding to the arginine-rich domains of several RNA-binding proteins are able to bind to their specific RNA sites with high affinities and specificities. In the case of the HIV-1 Rev-Rev response element (RRE) complex, the peptide forms a single α-helix that binds deeply in a widened, distorted RNA major groove and makes a substantial set of base-specific and backbone contacts. Using a reporter system based on antitermination by the bacteriophage λ N protein, it has been possible to identify novel arginine-rich peptides from combinatorial libraries that recognize the RRE with affinities and specificities similar to Rev but that appear to bind in nonhelical conformations. Here we have used codon-based mutagenesis to evolve one of these peptides, RSG-1, into an even tighter binder. After two rounds of evolution, RSG-1.2 bound the RRE with 7-fold higher affinity and 15-fold higher specificity than the wild-type Rev peptide, and in vitro competition experiments show that RSG-1.2 completely displaces the intact Rev protein from the RRE at low peptide concentrations. By fusing RRE-binding peptides to the activation domain of HIV-1 Tat, we show that the peptides can deliver Tat to the RRE site and activate transcription in mammalian cells, and more importantly, that the fusion proteins can inhibit the activity of Rev in chloramphenicol acetyltransferase reporter assays. The evolved peptides contain proline and glutamic acid mutations near the middle of their sequences and, despite the presence of a proline, show partial α-helix formation in the absence of RNA. These directed evolution experiments illustrate how readily complex peptide structures can be evolved within the context of an RNA framework, perhaps reflecting how early protein structures evolved in an “RNA world.”

Keywords: RNA–protein recognition, RNA structure, arginine-rich motif, HIV-1 Rev-Rev response element, λ N antitermination

The ability of RNAs to fold into complex three-dimensional structures provides a diverse array of shapes and spatial arrangements of functional groups for recognition by proteins and peptides. It should therefore not be surprising that the first few examples of protein–RNA complexes have revealed quite distinct strategies for recognition. Cocrystal structures of four tRNA synthetase-tRNA complexes show four different ways in which proteins dock against a similar RNA framework. The glutaminyl tRNA synthetase binds to the minor groove side of the tRNA, the aspartyl tRNA synthetase binds to the major groove side, the seryl tRNA synthetase uses a long coiled-coil domain to bind primarily to the backbone of an extra tRNA stem, and the phenylalanyl tRNA synthetase uses a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) domain and coiled-coil arm to recognize the tRNA architecture (1–4). Unlike recognition of the more-or-less rigid tRNA structures, the R17 coat protein and U1A RNP domain bind to disordered loops of RNA hairpins, fixing the orientation of bases through specific interactions within hydrophobic protein pockets (5, 6). A similar mode of recognition is observed for the anticodon loop of glutaminyl tRNA (7). The other side of induced fit binding is exemplified by arginine-rich peptides from the bovine immunodeficiency virus Tat and HIV-1 Rev proteins in which β-hairpin and α-helical peptide conformations are stabilized upon binding to their respective RNA sites (8–13). The coiled-coil domain of the phenylalanyl tRNA synthetase also undergoes a disorder-to-helix transition upon RNA binding (4) and similar folding transitions may be common among ribosomal proteins (14).

The arginine-rich RNA-binding motif was first identified in bacteriophage λ, 21, and P22 N proteins (15) and is characterized by a preponderance of arginines, but otherwise little sequence similarity, within regions <20 amino acids long. Biochemical studies with peptides from HIV-1 Tat (16–18), HIV-1 Rev (19, 20), bovine immunodeficiency virus Tat (8, 21), and λ and P22 N (22) suggest that arginine-rich regions can function as independent RNA-binding domains that faithfully mimic many of the binding properties of the intact proteins. Though the proteins are classified together as a family, arginine-rich RNA-binding domains in fact display a rather wide range of conformational preferences, including α-helices, β-hairpins, and probably extended chains, and in general are weakly structured or disordered until bound to their specific RNA-binding sites (8, 9, 11, 22, 23). Thus, it appears that peptide–RNA interactions with the surrounding RNA framework help “mold” the peptides into particular conformations, and it is tempting to speculate that RNAs may have served as structural scaffolds during the early evolution of proteins.

To explore the possibility that peptides may be molded into a given RNA site, we have been designing combinatorial peptide libraries using the structurally versatile arginine-rich motif as a framework and have been screening for novel RNA binders using an in vivo reporter assay based on antitermination by the bacteriophage λ N protein (24). As an initial target we chose the Rev response element (RRE), which contains two purine-purine base pairs that widen the major groove and form a binding pocket for the α-helical Rev peptide (12). Peptides that bind with affinities comparable to Rev were identified from a library consisting only of arginine, serine, and glycine, and these peptides appear to recognize the RRE using different amino acids than Rev and appear to bind in nonhelical conformations (24). In the present study, we have further molded one of the peptides to the RRE using repetitive rounds of codon-based mutagenesis and selection, analogous to in vitro evolution of RNA catalysts (25, 26). In such directed evolution experiments, the aim is to find increasingly active molecules by beginning with a single active molecule and exploring closely related sequences, presumably optimizing interactions or active conformations. After two rounds of peptide evolution, we have identified variants that recognize the RRE with substantially higher affinities and specificities than Rev. In vitro binding competition experiments demonstrate that the peptides effectively displace Rev from the RRE, and in vivo reporter assays suggest that the peptides can inhibit Rev function. The results reinforce the idea that a single RNA site can be recognized in different ways and suggest that tight binding peptides may be evolved to inhibit RNA-protein interactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of Combinatorial Libraries.

Peptide libraries were expressed as fusions to the bacteriophage λ N protein and were screened for RNA-binding activities in a two-plasmid antitermination reporter assay (24, 27). Degenerate oligonucleotides encoding the libraries were synthesized by a codon-based mutagenesis procedure. Two oligonucleotides were synthesized in parallel, one encoding a prototype sequence and the other containing randomized codons at appropriate positions. Following synthesis of each randomized codon, the two resins were mixed and then split in amounts that created the desired distribution of codons at each position varied. The prototype sequences encoding peptide RSG-1 (24), 5′-GAATCCCCATGGCCCGTCGCCGTCGCCGTCGTGGCAGTCGCCGTAGTGGCGCCAGTCGTCGCCGTCGCCGTGCAGCTGCGGCGAATGCAGCAAATCC-3′, and RSG-1.1 (a peptide evolved in this study), 5′-GAATCCCCATGGCCCGTCGCCGTCGCCGTCGTGGCAGTCGCCCTAGTGGCGCCGAGCGTCGCCGTCGCCGTGCAGCTGCGGCGAATGCAGCAAATCC-3′, were synthesized in parallel with the randomized RSG-1 oligonucleotide, 5′-GAATCCCCATGGCCCGTCGCCGTCGCCGT(NNK)9CGTCGCCGTCGCCGTGCAGCTGCGGCGAATGCAGCAAATCC-3′, and randomized RSG-1.1 oligonucleotide, 5′-GAATCCCCATGGCC(NNK)5CGTGGCAGTCGCCCTAGTGGCGCCGAG(NNK)5GCAGCTGCGGCGAATGCAGCAAATCC-3′, respectively. A primer (5′-GGATTTGCTGCATTC-3′) was annealed to the 3′-end of each degenerate oligonucleotide, and complementary strands were synthesized using Sequenase 2.0 (United States Biochemical). A 32-codon library containing NNK codons, where N is an equimolar mixture of A, C, G, and T, and K is an equimolar mixture of G and T, was used for randomization. This mixture encodes all 20 acids and one stop codon, though the number of codons representing each amino acid differs. Codons were randomized at a 25% frequency to optimize the representation of variants containing two and three mutations when nine or ten amino acid positions are mutagenized (28). By screening ≈200,000 sequences, it is possible to sample all variants containing two mutations with >90% confidence and a small percentage (≈2%) of variants containing three mutations. Confidence levels were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution (29).

Screening for Peptide Variants with Increased Antitermination Activities.

For primary screens, double-stranded degenerate oligonucleotides were digested with NcoI and BsmI and ligated into 3–5 μg of pBR322-derived N-expressor plasmid. Ligation mixtures were transformed into Escherichia coli N567 cells (30) containing a pACYC-derived RRE reporter plasmid and ≈200,000 transformants were plated onto 40–50 tryptone plates (150 mm) containing 0.05 mg/ml ampicillin, 0.015 mg/ml chloramphenicol, 0.012 mg/ml (50 μM) isopropyl β-d-galactoside [to induce the tac promoters that drive expression of the N protein and β-galactosidase (β-gal)], and 0.08 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactoside. Individual dark blue colonies were then grown to saturation in 96-well plates containing tryptone and antibiotics, cultures were pooled, and N-expressor plasmids were isolated. In secondary screens, pooled N-expressor plasmids were then retransformed into fresh RRE-reporter cells to eliminate reporter-related false positives. Antitermination activities were quantitated by visual estimation of colony color and by β-gal solution assays. In the colony color assay, the number of plusses represents relative blue intensity after growth on 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactoside plates (described above) for ≈48 hr at 34°C. For solution assays, bacteria were grown at 37°C to early log phase, isopropyl β-d-galactoside was added to 0.5 mM, and cells were grown for 1 additional hr to OD600 = 0.4–0.5. The cells were then permeabilized and assayed for β-gal activity using an ONPG colorimetric assay (24).

Peptides, Proteins, and RNAs.

Peptides were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems model 432A peptide synthesizer and purified as described (21). All peptides were capped by a succinyl group at the N terminus and by four alanines and an amide group at the C terminus. Peptide molecular masses were confirmed by electrospray mass spectrometry, and peptide concentrations were determined by quantitative amino acid analysis (University of Michigan Protein and Carbohydrate Structure Facility, Ann Arbor, MI). Purified Rev protein was generously provided by Drs. Maria Zapp and Marie-Louise Hammarskjöld (31, 32). Internally labeled RNAs were transcribed in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase (33) and [α-32P]CTP (NEN, 3,000 Ci/mmol; 1 Ci = 37 GBq). RNAs were purified and concentrations were determined as described (21).

RNA-Binding Assays.

RNA-binding gel shift assays were performed by incubating peptides and/or Rev protein with RNA at 4°C in 10 μl binding mixtures containing 10 mM Hepes⋅KOH (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 50 μg/ml tRNA, and 10% glycerol. To determine relative binding affinities of peptides, 0.1–0.2 nM radiolabeled RNAs were titrated with peptide, and peptide–RNA complexes were resolved on 10% polyacrylamide, 0.5× TBE (45 mM Tris/45 mM boric acid/1 mM EDTA, pH 8) gels that had been prerun for 1 hr and allowed to cool to 4°C (21). Apparent Kd is defined as the concentration of peptide required to shift 50% of the free RNA into the complex. For competition experiments with the Rev protein, 10 nM RNA was used and peptide:protein stoichiometries were varied as described.

Fusions to HIV-1 Tat, Mammalian Transfection, and Chloramphenicol Acetyltransferase (CAT) Assays.

Plasmids expressing Tat1–48, Tat1–48-Rev34–50, and Tat1–49-RSG proteins were constructed in the pSV2 Tat expression vector by oligonucleotide cassette mutagenesis as described (20). To measure levels of Tat activation mediated through the RRE IIB site, plasmids expressing the fusion proteins (1–500 ng) were cotransfected into HeLa cells along with an HIV-1 long terminal repeat-RRE IIB-CAT reporter plasmid (50 ng) (20) using lipofectin (GIBCO/BRL). To measure effects on Rev activity, plasmids expressing the Tat-peptide fusions (1–1,000 ng) were cotransfected with a pDM128 CAT-RRE reporter plasmid (100 ng) (34) and a pSV2 Rev expressor plasmid (50 ng). For both Tat and Rev assays, CAT activity was determined 48 hr after lipofection.

Circular Dichroism.

CD spectra were measured using an Aviv model 62DS spectropolarimeter. Samples were prepared in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5 and 100 mM KF. Spectra were recorded using a 1 cm pathlength cuvette at 4°C and signal was averaged for 5 sec at each wavelength. Scans were repeated five times and averaged. Mean molecular ellipticity was calculated per amino acid residue and helical content was estimated from the value at 222 nm (35).

RESULTS

Selection of RSG Variants with Increased Antitermination Activities.

We previously used a two-plasmid β-gal reporter assay to identify peptides from combinatorial libraries that bind tightly to the RRE. In this assay, peptides are fused to the bacteriophage λ N protein and RNA binders are identified by the ability to antiterminate transcription using a reporter plasmid containing the RRE IIB hairpin replacing box B of the λ nut site (24). One peptide from this screen, RSG-1 (Fig. 1), was chosen for further mutagenesis and selection in an attempt to evolve even tighter binding peptides. We first mutagenized the central nine residues of RSG-1 (Round 1, Fig. 1) using a codon-based mutagenesis procedure that introduced 32 possible codons (encoding all 20 amino acids) with a 25% probability of mutation at each position (see Materials and Methods). Codon-based mutagenesis generally introduces less amino acid bias than nucleotide-based mutagenesis or mutagenic PCR and can be used to reduce the size of screens (36–40). RRE-reporter cells were used to visually screen ≈200,000 colonies, sufficient to sample most sequences containing two mutations and ≈2% containing three mutations. Only 5–10% of colonies were as blue as the parent RSG-1 (scored as ++), suggesting that a substantial fraction of mutations decrease RRE-binding activity. We picked 770 of the darkest blue colonies (≈0.4% of the total screened), isolated plasmid DNA, and retransformed the pooled plasmids into RRE-reporter cells. In this secondary screen, ≈5% of colonies were darker blue than RSG-1 whereas the same plasmids transformed into noncognate reporter cells gave only a background level of blue colonies (<0.5%; ref. 24), indicating that many were RRE-specific. Plasmids were isolated from 51 positive clones (scored as +++ or ++++) and 8 unique sequences were found (Fig. 1). Interestingly, a pair of substitutions was often found at Arg-10 and Ser-14, usually mutated to Pro-10 and Glu-14. The double mutant, RSG-1.1, showed a substantial increase in antitermination activity as measured by the plate assay (increasing from ++ to ++++) and about a 2-fold increase in β-gal activity as measured by the less sensitive solution assay (Fig. 1). Several clones contained a third mutation but these were no more active than the double mutant.

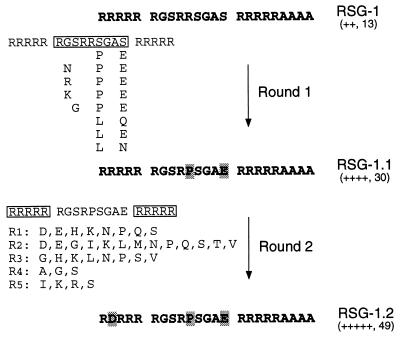

Figure 1.

Summary of two rounds of codon-based mutagenesis and selection of RSG-1 variants with increased antitermination activities. Peptide libraries were fused before residue 19 of the N protein and following methionine and alanine. RSG-1 was previously selected from a library consisting of arginine, serine, and glycine randomized at nine positions and flanked by five arginines at the N terminus and five arginines and four alanines at the C terminus (24). RSG-1 contains an alanine not encoded by the designed library. In the first round of evolution, the central nine amino acids (boxed) were randomized as described in the text and the eight sequences shown had increased antitermination activities. RSG-1.1 contains Pro-10 and Glu-14 substitutions (highlighted). In the second round of evolution, five flanking arginines on each side of the central region (boxed) were randomized in RSG-1.1 and clones with increased activities contained substitutions only in the N-terminal arginines. A summary of residues found at each of the five positions is shown, and these include single, double, and triple mutants. RSG-1.2 contains Asp-2, Pro-10, and Glu-14 substitutions (highlighted). Antitermination activities were determined by a β-gal colony color (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactoside) assay as indicated by plusses (the Rev peptide scores +++ and the wild-type N-nut interaction scores ++++++) and by a solution o-nitrophenyl β-galactoside assay (units β-gal) as described (24).

A second round of evolution was performed on RSG-1.1 using the same codon-based mutagenesis procedure as in the first round, but this time mutagenizing the five arginines flanking each side of the central 9-amino acid region (Fig. 1). We screened ≈200,000 colonies and found that a large proportion (>5%) were very dark blue after growth for only 20 hr, suggesting that many variants had increased binding activities. We picked 900 of the darkest blue colonies, prepared pooled plasmids, and found that most colonies in the secondary screen (>50%) were darker blue than RSG-1.1. Plasmids were isolated from 59 positive clones and 45 unique sequences were found (Fig. 1). Strikingly, we observed amino acid substitutions only in the N-terminal five arginines and two cases in which C-terminal arginine codons were changed, consistent with the frequency expected if all C-terminal arginines were essential. Many types of single, double, and triple mutants were found within the N-terminal arginines, with only a slight preference for proline at the second position and glycine at the fourth position. Of 12 single mutants, 10 had substitutions at the second position, often to acidic residues but not to lysine, suggesting that fewer positive charges near the N terminus might enhance binding. This is consistent with deletion analysis that showed that removing two or four N-terminal arginines, but not five, increased binding (data not shown). RSG-1.2, which contains an Arg-2 to Asp-2 substitution and shows a 2-fold increase in β-gal activity compared with RSG-1.1 and scores +++++ in the plate assay (Fig. 1), was chosen for additional study.

In Vitro RRE Binding of Selected RSG Peptides.

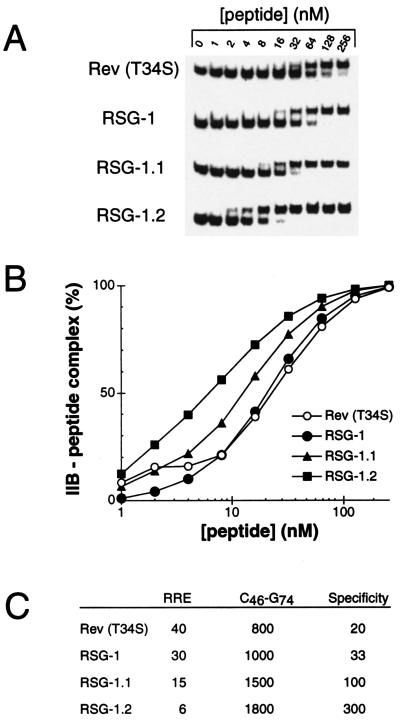

To confirm that the increased antitermination activities observed in the reporter assay result from increased RRE-binding affinities, peptides corresponding to RSG-1.1 and RSG-1.2 were synthesized and affinities were determined by gel shift assays (Fig. 2). As described (24), RSG-1 binds with slightly higher affinity than a partially helical Rev peptide (30 nM vs. 40 nM), and the two evolved peptides, RSG-1.1 and RSG-1.2, bind with still higher affinities (15 nM and 6 nM, respectively). RRE-binding specificities improve even more substantially; the Rev peptide shows a 20-fold preference for wild-type IIB over a C46-G74 mutant (20), RSG-1 shows a 33-fold preference, RSG-1.1 a 100-fold preference, and RSG-1.2 a 300-fold preference (Fig. 2C). Part of the increase in specificity results from a decrease in nonspecific binding affinities (Fig. 2C), most likely reflecting the progressive decrease in net positive charge of the selected peptides. The most highly evolved peptide, RSG-1.2, binds to RRE IIB RNA with ≈7-fold higher affinity and ≈15-fold higher specificity than the Rev peptide.

Figure 2.

(A) RNA-binding gel shift assays with RSG and Rev peptides. 0.1 nM RRE IIB RNA was titrated with Rev34–47 (T34S, E47R), RSG-1, RSG-1.1, and RSG-1.2 peptides at the concentrations indicated. Binding reactions contained a large excess of competitor tRNA. (B) Binding isotherms for Rev34–47 (T34S, E47R) (○), RSG-1 (•), RSG-1.1 (▴), and RSG-1.2 (▪) quantitated from A. (C) Apparent KDs (nM) for RSG and Rev peptides with wild-type RRE IIB RNA or the C46-G74 mutant. Specificity was calculated as the ratio of specific (wild-type IIB) to nonspecific (C46-G74 mutant) KAs.

In Vitro Competition Between RSG Peptides and the Rev Protein for the RRE.

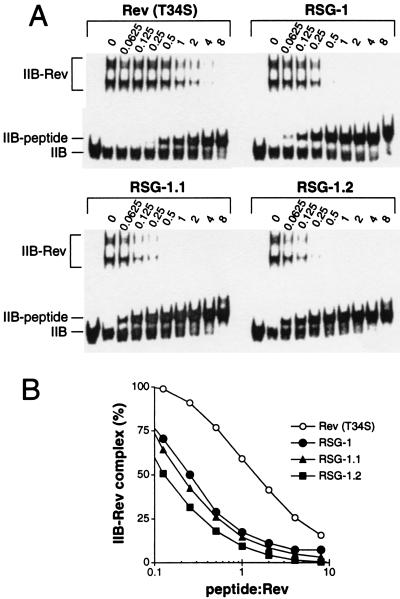

Because tight RRE-binding peptides might potentially be used to inhibit Rev activity, we next asked whether the selected RSG peptides could compete with Rev for RRE binding. A complex was formed between the intact Rev protein and RRE IIB RNA in vitro, increasing amounts of peptide were added, and protein–RNA and peptide–RNA complexes were resolved on gels (Fig. 3A). An equimolar amount of Rev peptide was required to displace 50% of the protein from the complex, as expected for a peptide that binds with similar affinity as the protein (19). In contrast, only 0.2 equivalents of RSG-1, 0.1 equivalents of RSG-1.1, and 0.05 equivalents of RSG-1.2 were needed to achieve 50% inhibition, correlating well with their relative RRE-binding affinities. Thus, RSG-1.2 competes for Rev binding 20-fold more effectively than the Rev peptide.

Figure 3.

In vitro competition between RSG peptides and the Rev protein for RRE binding. (A) Complexes were formed between RRE IIB RNA (10 nM) and intact Rev protein (160 nM), and peptides were titrated at the peptide:protein ratios indicated. (B) Quantitation of the data in A: Rev34–47 (T34S, E47R) (○), RSG-1 (•), RSG-1.1 (▴), and RSG-1.2 (▪).

Activities of RSG Peptides in Mammalian Cells.

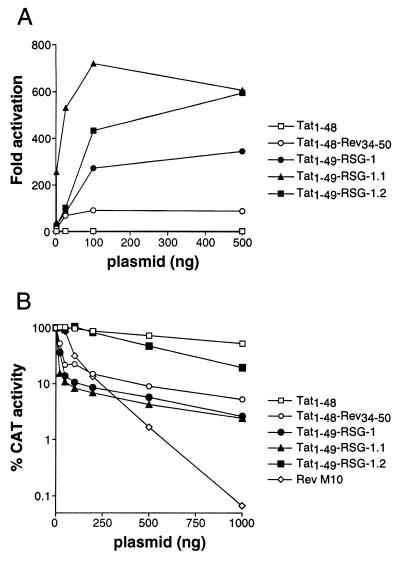

To test whether the selected peptides can bind to the RRE in mammalian cells, we next fused the peptides to the activation domain of HIV-1 Tat and asked whether the fusion proteins could activate transcription through an RRE IIB site located in place of TAR in an HIV-1 long terminal repeat-CAT reporter (20). We observed a dose-dependent increase in CAT activity for the Rev peptide, RSG-1, and RSG-1.1 (Fig. 4A), correlating with their relative binding affinities. RSG-1.2 also showed dose-dependent activation but had weaker activity than RSG-1.1, perhaps reflecting a suboptimal fusion to the Tat activation domain. Several additional fusions were constructed in which the linker between RSG-1.2 and the activation domain was altered, but none showed increased activity (data not shown). It remains unclear why RSG-1.2 does not function as well as RSG-1.1 in the Tat context despite its higher RNA-binding affinity.

Figure 4.

Activity of peptides fused to HIV-1 Tat in mammalian cells. (A) Tat-mediated activation of an HIV-1 long terminal repeat-RRE IIB CAT reporter (20) by Tat-Rev peptide and Tat-RSG peptide fusions. Expression plasmids were transfected into HeLa cells at the concentrations indicated and CAT activities were measured after 48 hr (23). Fold activation was calculated as the ratio of CAT activity in the presence and absence of Tat fusion proteins. (B) Inhibition of Rev-mediated export of CAT-encoding mRNAs by Tat-Rev peptide, Tat-RSG peptide fusions, and Rev M10. Expression plasmids were transfected into HeLa cells at the concentrations indicated along with pDM128 CAT reporter and pSV2 Rev expressor plasmids, and CAT activities were measured after 48 hr.

The ability of the selected peptides to inhibit Rev function was tested using the Tat-peptide fusions as competitors in a Rev reporter assay. The reporter plasmid, pDM128, contains the RRE and CAT gene within an intron; thus translation of CAT is dependent on Rev-mediated export of unspliced mRNAs (34). The Tat-peptide fusions were cotransfected with pDM128 and pSV2-Rev, a Rev-expression plasmid, and as observed for Tat activation, the Rev peptide, RSG-1, and RSG-1.1 showed dose-dependent inhibition of Rev function that correlated with their RNA-binding affinities (Fig. 4B), but RSG-1.2 had little activity. At high plasmid concentrations, inhibition by the peptides was not as effective as a Rev M10 mutant, which appears to inhibit Rev by competing for protein–protein interactions (41, 42), but at low concentrations the best RNA-binders were more effective than M10. While we do not know whether steady-state levels of M10 and the Tat fusion proteins are comparable, it is clear that the two types of inhibitors have rather distinct dose-dependencies (Fig. 4B), consistent with different mechanisms or targets of inhibition.

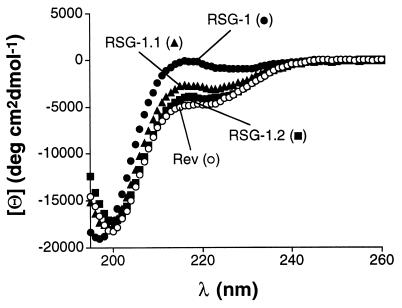

CD of RSG Peptides and Peptide-RNA Complexes.

CD and NMR experiments have shown that the Rev peptide binds to the RRE in an α-helical conformation (12, 13, 20) whereas CD spectra of RSG-1 indicated little or no helix formation, suggesting a different mode of binding (24). To preliminarily examine the conformations of the evolved RSG-1.1 and RSG-1.2 peptides, CD spectra were measured in the absence of RNA (Fig. 5). Remarkably, while RSG-1 shows a random coil spectrum, RSG-1.1 and RSG-1.2 show partial α-helix formation (8% and 12%, respectively) despite the fact that the peptides have proline substitutions near the middle of their sequences. CD difference spectra of RSG-1.1 and RSG-1.2 in the presence and absence of IIB RNA indicated little change in helix content upon binding, unlike Rev peptides that become fully helical (data not shown; ref. 11).

Figure 5.

CD spectra of Rev34–47 (T34S, E47R) (○), RSG-1 (C2R) (•), RSG-1.1 (▴), and RSG-1.2 (▪).

DISCUSSION

In this study we have shown that tight RNA-binding peptides can be evolved through multiple rounds of mutagenesis and selection, in essence molding a peptide to fit the shape of a particular RNA site. By choosing an appropriate initial amino acid library followed by codon-based mutagenesis, it is possible to explore sequence space in a relatively extensive and unbiased manner (28). The bacterial λ N antitermination system is well-suited to screening large numbers of peptide sequences, functions over a wide range of antitermination activities, and can distinguish between small differences in RNA-binding affinities. To date, the antitermination activities of the N fusion proteins have accurately reflected peptide RNA-binding activities as measured by several independent assays. For example, the Rev peptide, RSG-1, and the evolved RSG-1.1 and RSG-1.2 peptides show good correlations between antitermination activities and: (i) RNA-binding affinities of synthetic peptides in gel shift assays, (ii) competition between peptides and the Rev protein in vitro, (iii) activation of transcription when fused to HIV-1 Tat, and 4) inhibition of Rev function when fused to Tat, though RSG-1.2 does not function as well as other peptides in the Tat context. Thus, it appears that the antitermination system may be generally useful for identifying novel RNA-binding peptides and that an initial screen using only a small set of amino acids to crudely sample sequence space (24), followed by directed evolution as described here, may be an effective two-step strategy.

Our experiments with the RRE suggest that there may be multiple ways to recognize a given RNA site, using different peptide conformations and different amino acids to form the peptide–RNA interface. Arginine-rich peptides may be a particularly versatile framework for creating different types of RNA binders in part because the arginine guanidinium group displays five hydrogen bond donors for specific interactions and a positive charge for electrostatic interactions, and because the arginine side chain is long, flexible, and aliphatic and is therefore compatible with many possible structural arrangements. We do not yet know how the RSG peptides recognize the RRE with such high affinity and specificity, how they compare in structural detail to the Rev-RRE interaction, or how the three amino acid substitutions improve the binding of RSG-1. Based on the types of substitutions observed, we speculate that the RSG peptides may have evolved by stabilizing the three dimensional structure of the peptide and by eliminating unfavorable contacts (steric and/or electrostatic) rather than by creating new contacts to the RNA. For example, the proline substitution first seen in RSG-1.1 rather surprisingly increased the α-helical content of the peptide, suggesting that at least part of the peptide may be helical when bound to the RRE and that some of the improved affinity may result from helix stabilization. We suspect that the C-terminal part of peptide may be helical because deletion of the C-terminal alanines or replacement with glycines results in almost complete loss of antitermination activity (data not shown). Furthermore, the glutamic acid substitution identified in RSG-1.1 might help stabilize a helical conformation by forming an intramolecular salt bridge to an arginine, and it seems plausible that proline might introduce a kink, stabilize a turn, or cap the end of the helix, allowing the N terminus to fold back and form additional contacts to the RNA. Based on results from the second round of evolution, it appears that removing arginines from the N terminus enhances binding by eliminating unfavorable electrostatic contacts or steric clashes. Structural studies are clearly required to explore these and other possibilities in detail and to allow comparison to the α-helical Rev peptide.

The evolved RSG peptides bind to the RRE substantially more tightly than does Rev and efficiently block the Rev-RRE interaction in vitro. In vivo, RSG-1.1 inhibits Rev function when fused to Tat. Other studies have shown that it is possible to inhibit Rev function using RNA decoys that compete for Rev binding (43), dominant negative Rev mutants, such as M10, that appear to compete for protein–protein interactions (41, 42), and small molecules, such as neomycin and diphenylfurans, that bind directly to the RRE (44, 45). While peptides are not considered to be useful therapeutic agents because they are difficult to deliver and unstable, progress is being made in the design of peptidomimetics, and peptides have the advantage that binding affinities may be optimized using genetic screens and evolutionary strategies (refs. 24, 46–49; this study). It may also be possible to develop peptides for use in gene therapy protocols, either by expressing the peptide alone or as part of a fusion protein. Preliminary studies with the Rev M10 mutant show protection against HIV replication (50) and it will be interesting to compare M10 to the evolved RSG peptides, or to even tighter binders.

Finally, we wish to speculate that RNAs might have served as structural scaffolds to help peptides adopt discrete conformations during the early evolution of proteins. Given the wide range of tertiary structures that RNAs can adopt, it seems plausible that relatively complex peptide structures could be molded at RNA–peptide interfaces, and that as proteins increased in size, protein–protein interactions might have evolved to take the place of protein–RNA interactions, ultimately allowing proteins to fold stably on their own.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cynthia Honchell for peptide and oligonucleotide synthesis, members of the lab for helpful discussions, and Colin Smith for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM47478 and GM39589.

ABBREVIATIONS

- RRE

Rev response element

- CAT

chloramphenicol acetyltransferase

- β-gal

β-galactosidase

References

- 1.Rould M A, Perona J J, Söll D, Steitz T A. Science. 1989;246:1135–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.2479982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavarelli J, Rees B, Ruff M, Thierry J C, Moras D. Nature (London) 1993;362:181–184. doi: 10.1038/362181a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biou V, Yaremchuk A, Tukalo M, Cusack S. Science. 1994;263:1404–1410. doi: 10.1126/science.8128220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldgur Y, Mosyak L, Reshetnikova L, Ankilova V, Lavrik O, Khodyreva S, Safro M. Structure (London) 1997;5:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oubridge C, Ito N, Evans P R, Teo C H, Nagai K. Nature (London) 1994;372:432–438. doi: 10.1038/372432a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valegard K, Murray J B, Stockley P G, Stonehouse N J, Liljas L. Nature (London) 1994;371:623–626. doi: 10.1038/371623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rould M A, Perona J J, Steitz T A. Nature (London) 1991;352:213–218. doi: 10.1038/352213a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L, Frankel A D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5077–5081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puglisi J D, Chen L, Blanchard S, Frankel A D. Science. 1995;270:1200–1203. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye X, Kumar R A, Patel D J. Chem Biol. 1995;2:827–840. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan R, Frankel A D. Biochemistry. 1994;33:14579–14585. doi: 10.1021/bi00252a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Battiste J L, Mao H, Rao N S, Tan R, Muhandiram D R, Kay L E, Frankel A D, Williamson J R. Science. 1996;273:1547–1551. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5281.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye X, Gorin A, Ellington A D, Patel D J. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:1026–1033. doi: 10.1038/nsb1296-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yonath A, Franceschi F. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:3–5. doi: 10.1038/nsb0197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazinski D, Grzadzielska E, Das A. Cell. 1989;59:207–218. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90882-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weeks K M, Crothers D M. Cell. 1991;66:577–588. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calnan B J, Tidor B, Biancalana S, Hudson D, Frankel A D. Science. 1991;252:1167–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Churcher M J, Lamont C, Hamy F, Dingwall C, Green S M, Lowe A D, Butler J G, Gait M J, Karn J. J Mol Biol. 1993;230:90–110. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kjems J, Calnan B J, Frankel A D, Sharp P A. EMBO J. 1992;11:1119–1129. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan R, Chen L, Buettner J A, Hudson D, Frankel A D. Cell. 1993;73:1031–1040. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen L, Frankel A D. Biochemistry. 1994;33:2708–2715. doi: 10.1021/bi00175a046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan R, Frankel A D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5282–5286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calnan B J, Biancalana S, Hudson D, Frankel A D. Genes Dev. 1991;5:201–210. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harada K, Martin S S, Frankel A D. Nature (London) 1996;380:175–179. doi: 10.1038/380175a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beaudry A A, Joyce G F. Science. 1992;257:635–641. doi: 10.1126/science.1496376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehman N, Joyce G F. Nature (London) 1993;361:182–185. doi: 10.1038/361182a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franklin N C. J Mol Biol. 1993;231:343–360. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harada K, Frankel A D. In: RNA–Protein Interactions: A Practical Approach. Smith C, editor. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1997. , in press. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clackson T, Wells J A. Trends Biotechnol. 1994;12:173–184. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(94)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franklin N C, Doelling J H. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2513–2522. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2513-2522.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zapp M L, Hope T J, Parslow T G, Green M R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7734–7738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orsini M J, Thakur A N, Andrews W W, Hammarskjold M-L, Rekosh D. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:945–953. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milligan J F, Uhlenbeck O C. Methods Enzymol. 1989;180:51–62. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)80091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hope T J, McDonald D, Huang X J, Low J, Parslow T G. J Virol. 1990;64:5360–5366. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5360-5366.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Y H, Yang J T, Chau K H. Biochemistry. 1974;13:3350–3359. doi: 10.1021/bi00713a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glaser S M, Yelton D E, Huse W D. J Immunol. 1992;149:3903–3913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cormack B P, Struhl K. Science. 1993;262:244–248. doi: 10.1126/science.8211143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cadwell R C, Joyce G F. PCR Methods Appl. 1992;2:28–33. doi: 10.1101/gr.2.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vartanian J-P, Henry M, Wain-Hobson S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2627–2631. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.14.2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hermes J D, Blacklow S C, Knowles J R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:696–700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hope T J, Klein N P, Elder M E, Parslow T G. J Virol. 1992;66:1849–1855. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.1849-1855.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stauber R, Gaitanaris G A, Pavlakis G N. Virology. 1995;213:439–449. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee S W, Gallardo H F, Gilboa E, Smith C. J Virol. 1994;68:8254–8264. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8254-8264.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zapp M L, Stern S, Green M R. Cell. 1993;74:969–978. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90720-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ratmeyer L, Zapp M L, Green M R, Vinayak R, Kumar A, Boykin D W, Wilson W D. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13689–13696. doi: 10.1021/bi960954v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.SenGupta D J, Zhang B, Kraemer B, Pochart P, Fields S, Wickens M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8496–8501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laird-Offringa I A, Belasco J G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11859–11863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jain C, Belasco J G. Cell. 1996;87:115–125. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fouts D E, Celander D W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1582–1584. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.8.1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woffendin C, Ranga U, Yang Z, Xu L, Nabel G J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2889–2894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]