Abstract

Terminal RNA uridylyltransferases (TUTases) are functionally and structurally diverse nucleotidyl transferases that catalyze template-independent 3′ uridylylation of RNAs. Within the DNA polymerase β-type superfamily, TUTases are closely related to non-canonical poly(A) polymerases. Studies of U-insertion/deletion RNA editing in mitochondria of trypanosomatids identified the first TUTase proteins and their cellular functions: post-transcriptional uridylylation of guide RNAs by RNA editing TUTase 1 (RET1) and U-insertion mRNA editing by RNA editing TUTase 2 (RET2). The editing TUTases possess conserved catalytic and nucleotide base recognition domains, yet differ in quaternary structure, substrate specificity and processivity. The cytosolic TUTases TUT3 and TUT4 have also been identified in trypanosomes but their biological roles remain to be established. Structural analyses have revealed a mechanism of cognate nucleoside triphosphate selection by TUTases, which includes protein-UTP contacts as well as contribution of the RNA substrate. This review focuses on biological functions and structures of trypanosomal TUTases.

1. Introduction

The transfer of a nucleoside onto the 3′ end of a nucleic acid is catalyzed by several distinct enzyme superfamilies via a universal chemical mechanism. During RNA or DNA polymerization reactions, acidic residues in the active site coordinate two divalent metal ions, most commonly Mg2+, such as to position the α-phosphate of the incoming 5′ nucleoside triphosphate for the inline nucleophilic attack by a partially deprotonated 3′ hydroxyl group of the growing polynucleotide chain. This results in the formation of a phosphodiester bond and a pyrophosphate leaving group [1]. The catalytic modules of template-dependant RNA polymerases have been divided into at least five evolutionarily unrelated folds based on sequence and structural comparisons [2]. Conversely, all template-independent RNA polymerases possess a conserved catalytic domain shared within the DNA polymerase β superfamily [3,4]. The homoribonucleotide polymerases (specific for only one nucleoside triphosphate substrate) are represented by eukaryotic [5], bacterial [6], viral poly(A) polymerases [7] and terminal uridylyltransferases (TUTases) [8].

TUTases add a single or multiple UMP residues to the 3′ hydroxyl group of RNA in a template-independent reaction. These activities have been described in mammalian cells, plants, fission yeast and trypanosomatids (reviewed in [9]). Isolation of multi-protein complexes involved in uridine insertion/deletion RNA editing in mitochondria of trypanosomes (reviewed in [10,11]) led to the identification of RNA Editing TUTase 1 (RET1) [8] and RNA Editing TUTase 2 (RET2) [12,13]. RET1 and RET2 differ in RNA substrate specificity, polypeptide size, and quaternary structure, and have been implicated in distinct functions: post-transcriptional addition of the non-encoded 3′ oligo(U) tail to guide RNAs [14] and U-insertion mRNA editing [14,15], respectively. Two non-mitochondrial TUTases, TUT3 [16] and TUT4 [17] have also been identified in T. brucei. This review addresses recent advances in structural-functional studies of trypanosomal TUTases.

2. RNA processing in mitochondria of Trypanosomes

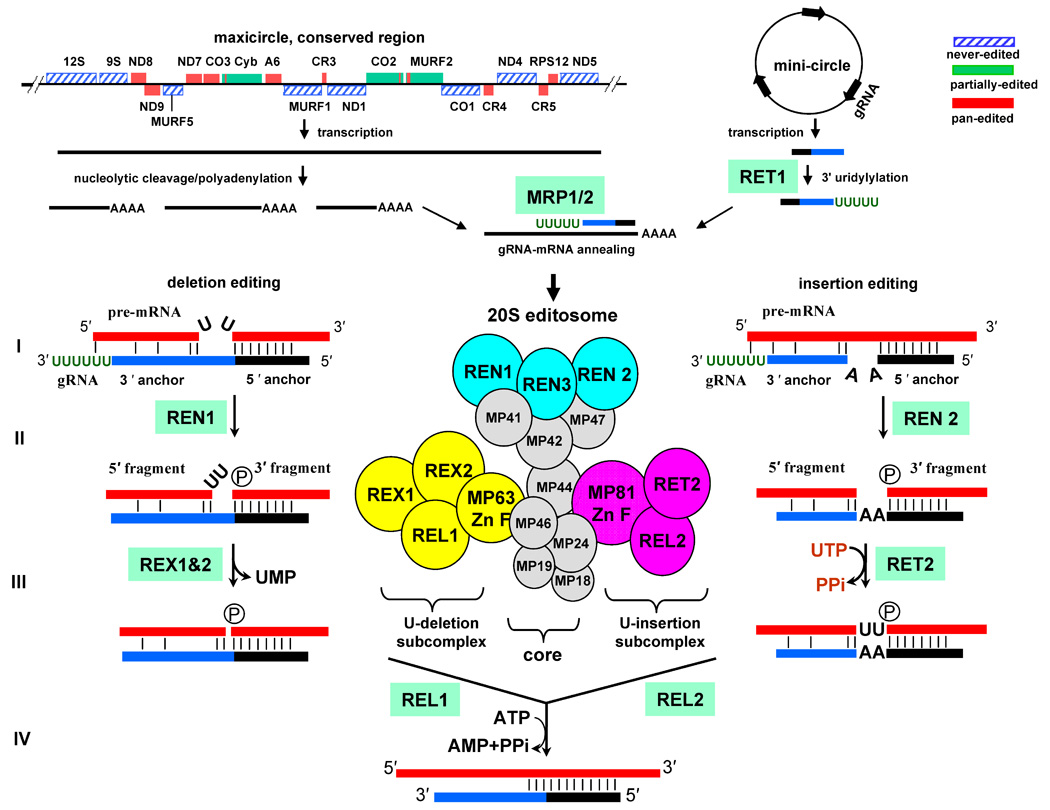

As most of our knowledge on TUTases comes from the work on RNA editing in mitochondria of trypanosomes, a brief overview of this process is provided in Figure 1. Maxicircle DNA is transcribed from unknown promoters by a single-subunit phage-like RNA polymerase, producing a polycistronic precursor(s) [18]. The adjacent pre-mRNAs within the primary transcripts overlap in several instances [19]. RNA processing in the mitochondria of trypanosomatid protozoa begins with a nucleolytic partitioning of multicistronic transcripts into ribosomal RNAs and pre-mRNAs, which then are subjected to 3′ polyadenylation and uridine insertion/deletion RNA editing. In Trypanosoma brucei, editing is directed by guide RNAs (gRNAs) and is required for the expression of 12 out of 18 protein-encoding genes. Guide RNAs are encoded primarily in minicircles although few gRNA genes are located in maxi-circles [20]. Regardless of the gene location, gRNAs are transcribed as independent individual units [21]. Mature gRNAs maintain di- or tri-phosphate at the 5′ end indicating lack of post-transcriptional 5′ processing. The 3′ processing adds an ~15 nt oligo (U) tail [22], which is required for gRNA function [14].

Figure 1.

RNA processing in mitochondria of Trypanosomes. The protein and ribosomal RNA genes are encoded in conserved region of maxicircles, which are ~25–35 kB molecules present in several copies per mitochondrial genome. The multicistronic precursor RNAs are transcribed from unknown promoters, cleaved into individual pre-mRNAs and polyadenylated. Guide RNAs are transcribed from thousands of 0.9–2.5 kB minicircles that form the bulk of catenated kinetoplast DNA network. Few gRNA genes are found in the maxicircles. gRNAs are posttranscriptionally uridylylated by RNA editing TUTase 1 (RET1). gRNA-mRNA hybridization is likely to be stimulated by the heterotetramer complex of mitochondrial RNA binding/chaperon proteins, MRP1/2. The mRNA is cleaved immediately upstream of the 5′ anchor duplex by distinct endonucleases: REN1 at deletion sites and REN2 at insertion sites. The mRNA’s 5′ and 3′ cleavage fragments are tethered by interactions with gRNA’s 3′ and 5′ “anchor” regions, respectively. In the U-deletion sites, single-stranded Us are removed by a U-specific exonucleases, REX1 and/or REX2. During the insertion editing, Us are added by RET2 according to the number of guiding nucleosides. RNA ligases seal the nicks in the double-stranded RNA. In the pan-edited mRNAs multiple overlapping gRNAs direct editing in a 3′–5′ direction: editing of the 3′ end region creates a binding site for the “anchor” of the subsequent guide RNA.

The multi-protein complexes that carry out a cascade of editing reactions (20S editosome), guide RNA 3′ end uridylylation (RNA editing TUTase 1, RET1), and mRNA-gRNA annealing (mitochondrial RNA binding proteins 1 and 2, MRP1/2) have been extensively studied (reviewed in [11,23]). In a steady-state population, edited mRNAs are present in pre-edited, highly heterogeneous partially-edited and fully-edited forms, the latter typically constituting only a small faction of the entire mRNA pool [24–26]. It is presumed that only never-edited and fullyedited mRNAs can direct protein synthesis, although a production of novel proteins via the translation of the alternatively edited mRNAs has been suggested [27].

The editing process is thought to begin with the formation of a short (5−15 nt) duplex between the “5′ anchor” region of the gRNA and pre-mRNA (Figure 1). The site selection is achieved by Watson-Crick base-pairing and is probably facilitated by the RNA annealing activity of MRP1/2, an α2β2 heterotetramer complex of two RNA binding proteins [28,29]. Partial complementarity of the mRNA and gRNA beyond the perfect duplex, also referred to as “3′ anchor,” creates secondary structure elements that define editing sites. In the U-deletion sites the unpaired single-stranded uridines in the mRNA form a bulge and the insertion site is characterized by unpaired guiding nucleotides, either As or Gs, forming the bulge in the gRNA (Figure 1). Upon gRNA binding, mRNA is cleaved by the RNaseIII-type endonucleases, REN1 and REN2, specific for U-insertion or deletion sites, respectively [30–32]. It is unknown whether the strand location (mRNA vs. gRNA) or chemical nature (R vs. Y) of unpaired nucleosides, or other features of the insertion and deletion sties, constitute the actual recognition signal for nucleolytic cleavage. The presence of the three distinct editosomes specific for the insertion, deletion, and cis-guiding insertion cites has been proposed [33], although it is unclear from the evolutionary standpoint why the “insertion” editosomes would still maintain the fully functional U-deletion enzymatic cascade and vise versa. Alternatively, three distinct endonucleases may indeed recognize specific structures of the insertion, deletion or cis-editing sites, and then recruit the common editing complex. Following the cleavage, the mRNA 5′ fragment presumably remains partially base-paired with the “3′ anchor” of the gRNA while the phosphate remains on the mRNA 3′ cleavage fragment. Thus, the first enzymatic step generates substrates for U-insertion by RET2 (two double-stranded RNAs linked by guiding nucleotides) or U-deletion by RNA editing exonucleases, REX1 and REX2 (a nicked double-stranded RNA with a single-stranded U overhang). The insertion and deletion activities are segregated into sub-complexes within the 20S editosome [34]. These sub-complexes also contain zinc-finger structural proteins and RNA editing ligases REL1 and REL2 that seal mRNA cleavage fragments upon completion of the U-deletion and U-insertion reactions, respectively [35].

3. Mitochondrial RNA editing TUTase 1: a multi-functional RNA processing enzyme

The founding member of the TUTase family was identified via biochemical purification of the major UMP-incorporating activity from mitochondria of Leishmania tarentolae [8]. The nearly homogenous preparation contained a polypeptide of ~140 kDa, which was used for gene cloning by reverse genetics. Unlike eukaryotic poly(A) polymerases, recombinant RET1 does not require additional protein factors for processive polymerization (Figure 2). On the contrary, RET1 activity in mitochondria is probably modulated to achieve a controlled synthesis of the ~15 nucleosides-long oligo(U) tails found in all guide RNAs. The size-fractionation and chemical cross-linking experiments suggested a homotetrameric organization of the enzyme, which is rather unusual among typically monomeric nucleotidyltransferases (NTs).

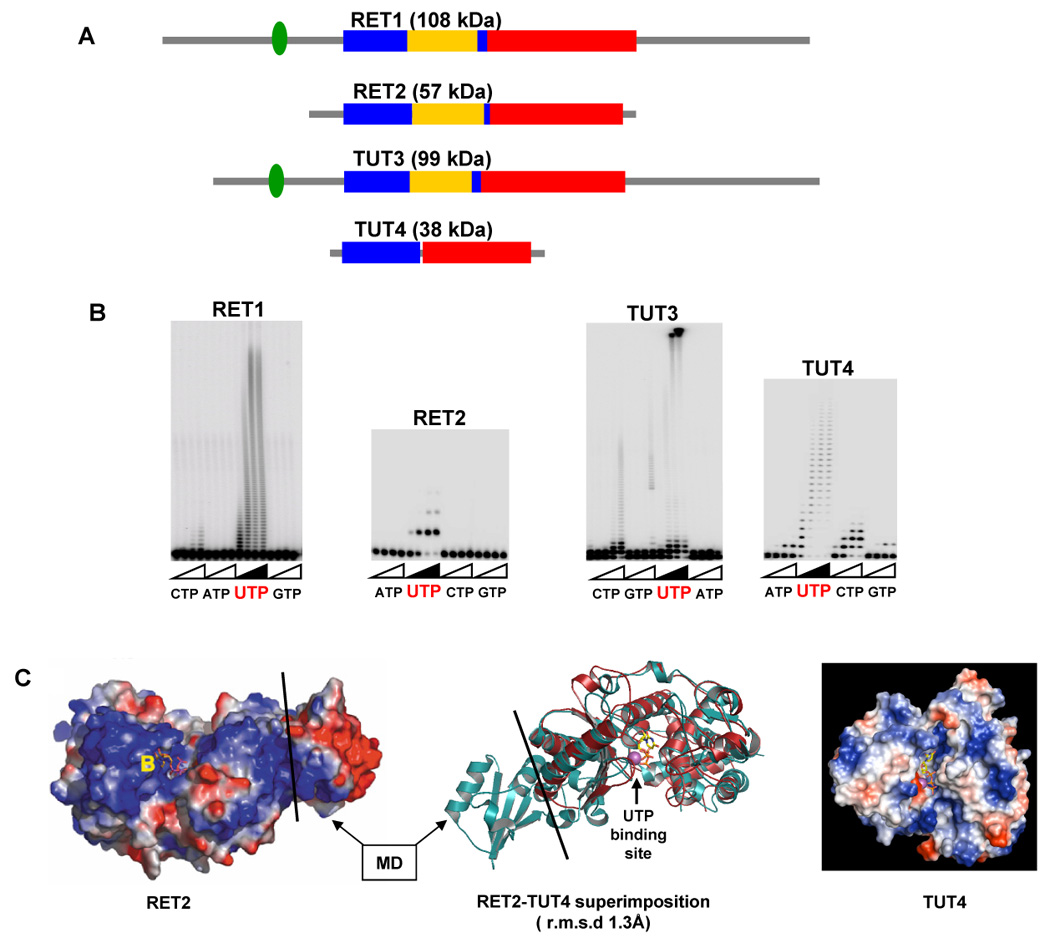

Figure 2.

Structural diversity of trypanosomal TUTases. A. Domain organization of trypanosomal TUTases. N-terminal catalytic (blue), middle (yellow) and C-terminal base recognition (red) domains are depicted to scale. C2H2-type zinc fingers are shown as green ovals. B. NTP selectivity and elongation patterns of TUTases. Synthetic single-stranded RNA substrates were used in all reactions. C. Crystal structures of RET2-UTP (left panel, [47]) and TUT4-UTP (right panel, [17]) binary complexes, reproduced with permission. Superimposition of protein chains is shown in the middle. MD- middle domain.

Sequence comparisons identified a signature motif closely matching the hG[G/S](x9–13)DxD[D/E]h (x- any amino acid, h- hydrophobic) consensus of the Pol-β superfamily signature sequence. The two acidic amino acids (DxD/E) of the signature motif and the third aspartate, which is typically located at the C-terminal end of the catalytic domain, coordinate two metal ions required for catalysis. Alanine scanning mutagenesis of the positions conserved between RET1 and eukaryotic poly(A) polymerases identified two aspartates of the signature sequence and a third aspartate located 202 amino acids toward C-terminus as essential for activity [36]. In eukaryotic poly(A) polymerases, the third aspartate is separated from the signature sequence by ~50 amino acids loop that is presumably involved in binding the RNA substrate [5,37,38]. In RET1, the extra 150 amino acid insertion constitutes a helix-rich domain essential for activity [36]. This insertion, designated as middle domain (MD), occurs at a conserved site within the catalytic domain and is found in RET1, RET2 and TUT3, but not in TUT4 (Figure 2). The lack of sequence similarity among middle domains in trypanosomal TUTases suggests divergent functions for these modules.

Phylogenetic comparisons of eukaryotic poly(A) polymerases, 2′–5′ oligoadenylate synthetases (OAS), non-canonical TRF4/5 poly(A) polymerases and archaeal CCA-adding enzymes and TUTases revealed an apparently monophyletic assemblage unified by the conserved C-terminal domain [39]. The protein motifs searches identified C2H2-type zinc fingers that are located ~ 50 amino acid upstream of the Pol- β signature sequence in RET1 and TUT3 (Figure 1). Deletion of the entire motif or mutations in the zinc-coordinating amino acids, as well as removal of the tightly-bound zinc ions by exhaustive chelating dialysis, were detrimental for RET1 activity [36]. The specific role for this motif remains to be investigated but its presence in processive TUTases, RET1 and TUT3, should be noted. Finally, overlapping oligomerization and RNA binding regions in RET1 have been mapped to the C-terminal quarter of the protein by sequential C-terminal deletions [36]. These regions have no similarities beyond kinetoplastid RET1 of trypanosomes and related species.

The proteomics of the RET1 interactions remain challenging. The immunochemical analysis and biochemical fractionation revealed the presence of RET1 in high-molecular weight complexes ranging from ~ 0.5 to 1.6 MDa [8,14] and established its interactions with the 20S editosome [8,12,14], and the MRP1/2 complex of mitochondrial RNA binding proteins [28]. Approximately 30% of the total guide RNA was bound to RET1 or RET1-containing complexes in mitochondrial extracts as determined by immunodepletion experiments [8]. The RET1 interactions with the MRP1/2 complex of RNA binding proteins [28] and the 20S editosome [8] have been demonstrated to depend on an unidentified RNA component. The RET1-containing particle of ~ 700 kDa (TUTII complex) was partially purified by column chromatography [8].

The complexity of RET1 interactions may, in part, reflect the plurality of its functions. RNA editing in mitochondria of trypanosomes is directed by trans-acting guide RNAs [20]. The non-encoded oligo[U] tail is found at the 3′ end of gRNAs [22], but it’s exact function remains the subject of debate. Inhibition of RET1 expression by RNAi led to a decrease in the steady-state level of the edited mRNAs [8]. The U-insertion activity of the 20S editosome, however, remained unaffected by RET1 RNAi while the loss of the gRNA’s oligo(U) tail has been detected [14]. The finding that non-uridylylated guide RNAs in RET1-depleted cells were stable yet apparently dysfunctional suggested that the oligo(U) tail is essential for editing. The most likely role of the oligo(U) tail appears to be a base-pairing with the purine-rich pre-edited region, which may stabilize the gRNA-mRNA hybrid [22]. The oligo(U) tail - pre-edited mRNA interaction may be particularly important for editing of the last few sites within an editing block (defined as a region complementary to a single gRNA). As the editing proceeds in a 3′–5′ direction (mRNA polarity), the “5′ anchor” is extended, but the “3′ anchor” is shortened, often to only 1–2 base-pairs.

It is unclear whether the gRNA’s 3′ end is generated by a precise termination of transcription or nucleolytic degradation of a precursor molecule. Because of RET1’s high processivity in vitro (Figure 2B, [8,14,36], certain modulation of the activity, such as efficient termination after addition of ~15 Us, must take place in order to synthesize an oligo[U] tail. This modulation may require protein factors that bind to RET1 or to the uridylylated product. Alternatively, a competing 3′–5′ U-specific exonuclease may trim products longer then ~15 Us.

Several observations suggest that RET1 may also be involved in the 3′ end processing of mitochondrial mRNAs. The original report of random U incorporation in the poly(A) tails [25] gained new dimension after finding that the mRNA decay in isolated mitochondria may be stimulated by increased UTP concentration [40]. Furthermore, UTP polymerization by RET1 is required for this phenomenon [41] suggesting that an increase in the U-content of the poly(A) tails may lead to mRNA degradation.

4. Mitochondrial RNA editing TUTase 2: guided U-insertion RNA editing

In mitochondrial extract, RET2 exists as a subunit of the 20S editosome and is responsible for the major U-insertion mRNA editing activity [14,15]. Within the 20S editosome, the insertion/ligation and deletion/ligation activities are spatially clustered via C2H2 zinc-finger motif-containing structural proteins MP81 and MP63, respectively, into a distinct sub-complexes (Figure 1, [34,42–45]). RET2 directly interacts with MP81 [15,34], which has also been shown to stimulate RET2 activity in vitro [15]. MP81 also binds RNA editing ligase 2 (REL2), thereby forming a U-insertion sub-complex [34] (Figure 1). Inhibition of RET2 expression by RNAi led to a selective decrease in the abundance of MP81 and REL2 ligase [14] whereas MP81 RNAi partially destabilized the entire 20S editosome [46]. Therefore, protein-protein interactions involving RET2 are likely to be essential for its incorporation into the 20 S editosome and its activity within the editing complex.

A high degree of sequence similarity between the N-terminal catalytic (NTD) and C-terminal (CTD) domains of RET1 and RET2 proteins (Figure 4) indicates general conservation of these modules but provides little cues for the major differences among editing TUTases’ enzymatic properties. Interaction of TUTase with other proteins are likely to be carried out by function-specific auxiliary domains and motifs, such as middle domain or zinc finger, whereas variations in the active site may account for the observed differences in UTP selectivity and RNA substrate specificity. Breakthrough crystallographic studies of RET2 revealed a domain organization previously unseen among nucleotidyl transferases: the noncontiguous NTD and CTD share a large interface essentially creating a spherically-shaped “catalytic bi-domain” (Figure 2C) [47]. The antiparallel β-sheet of the NTD and two helices in the CTD form a deep cleft in which three catalytic aspartate residues and the UTP binding site are situated. The middle domain is inserted between two β-strands at the C-terminus of the NTD and folds out into the solvent while maintaining extensive interactions with the CTD. Remarkably, the “insertions” of the middle domains via flexible loops occur in the conserved site in RET1, RET2 and TUT3 (Figure 1A) while the domains themselves are divergent at the protein sequence level. Positioning of the MD in respect to the catalytic cavity makes its contribution to UTP binding unlikely, but points out to a potential role in RNA binding and/or protein-protein interactions. Indeed, a limited topological similarity of the RET2’s MD to known RNA binding domains has been observed [47]. Consistent with its essential function, middle domain deletion in RET1 led to a complete inactivation of the enzyme [36].

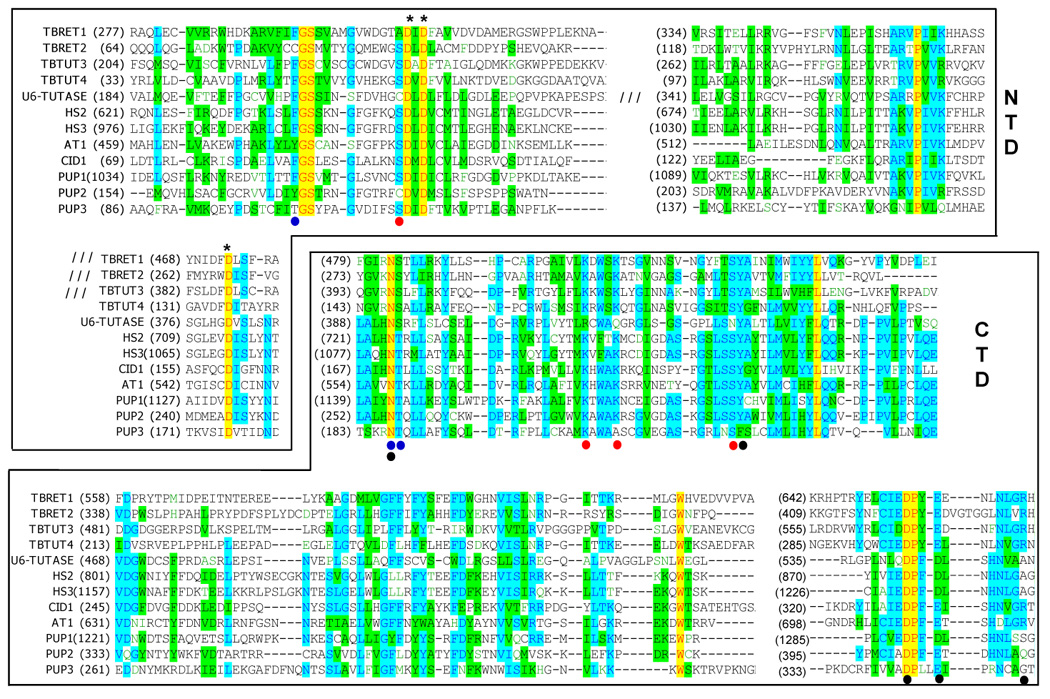

Figure 4.

Partial multiple sequence alignment and domain delineation of currently known TUTases. Alignments were performed with T-coffee algorithm [66]. Insertions in the N-terminal domain are indicated for RET1, RET2, TUT3 and U6 TUTases. Following protein sequences used in the alignment: TbRET1 (AAK38334), TbRET2 (AAO63567), TbTUT3 (AAK38334), TbTUT4 (DQ923393), U6-TUTase (NM_02283, [67]), Hs2 (BAB21802, [48]), Hs3 (XP_038288, [48]), CID1 (NP_594901, [49]), AT1 (At2g45620, [48]), PUP1 (K10D2.3, [48]), PUP2 (K10D2.2, [48]) and PUP3 (F59A3.9, [48]). Catalytic aspartates are shown by asterisks. Amino acids that interact with UTP moieties are shown by dots as follows: phosphates (red), ribose (blue) and uracil base (black). The omitted insertions are indicated by three forward slashes.

5. Non-mitochondrial TUTases

RNA editing is likely to have arisen in evolution multiple times as a means to correct mutations and modulate gene expression at RNA level. The editing events are often found in organelles; likewise the U-insertion/deletion mRNA editing is phylogenetically confined to mitochondria of kinetoplastid protozoa. As such, editing TUTases provide little insight into broader biological roles of UTP-specific terminal RNA transferases in eukaryotic cells. Identification of RET1 and RET2 provided first examples of structurally and functionally divergent TUTases and allowed identification of TUTase-like genes by database searching [9].

The closest homolog of RET1 and RET2 in trypanosomal genomes is the TUT3 protein [16]. This highly processive uridylyl transferase is not targeted to the mitochondria and its biological function remains to be determined. A C2H2 zinc finger, which is essential for activity in RET1 [36], is also found in TUT3 (Figure 2). Another “functional orphan”, TUT4, was identified by homology to editing TUTases and represents a naturally occurring minimal core module of uridylyltransferases [17]. The minimal TUTase has become an instrumental model in crystallographic and biochemical studies of UTP selection mechanisms and RNA specificity.

6. Mechanism of UTP recognition by TUTases

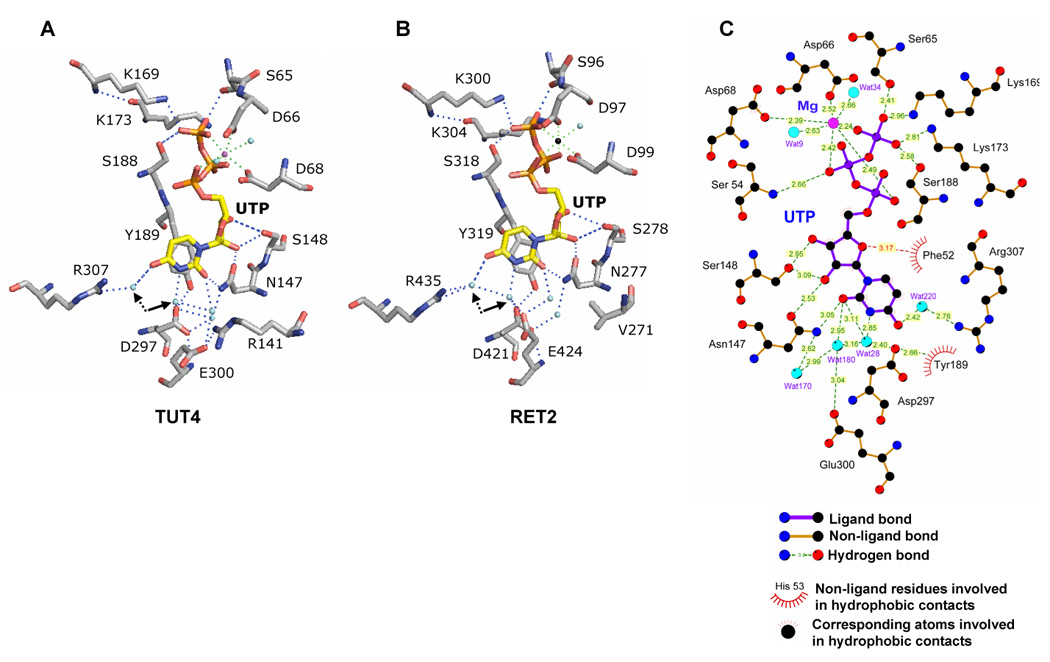

A fundamental difference between template-dependent and guided transfers of genetic information is a reliance of the former process on Watson-Crick base-pairing and the key role of protein-UTP and protein-RNA recognition in the latter. Although the U-specificity of RET2 is nearly absolute while TUT4 is more promiscuous (Figure 2B), X-ray crystallography produced a coherent picture of UTP binding sites in RET2 [47] and TUT4 [17] (Figure 3). The uridine base is locked in anti-conformation and is buried at the bottom of the deep cleft formed by the NTD and CTD (Figure 2C). The O2 atom of the uracil base forms a hydrogen bond with an invariant asparagine 147/277 (herebelow amino acids will be numbered TUT4/RET2) and a water molecule. The UTP specificity, however, is determined primarily by the two closely positioned carboxylic residues, D297/D421 and E300/E424, which coordinate a crucial water molecule indicated by solid arrow in Fig. 3A, B. Base-specific recognition is achieved by the endocyclic N3 donating a hydrogen bond to this water molecule, and carbonyl O4 receiving a hydrogen bond from another water molecule shown by the dotted arrow. CTP binding would require reversal of the hydrogen-bonding pattern at these two positions of the pyrimidine base. In addition, an essential π-stacking interaction of the aromatic tyrosine residue (189/319) and the pyrimidine ring contributes to UTP binding. The phosphates are coordinated via water-mediated and direct hydrogen bonding with amino acid residues invariant among most of Pol-β superfamily members such as S65/S96 S188/318, K169/300 and K173/K304. In addition, the structure of the TUT4-dUTP complex demonstrated the importance of the 2′ hydroxyl group H-binding with the key residue N147, which also forms a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl oxygen at position 2 of the uracil ring. The latter interaction appears to be maintaining co-planarity between the uracil base and the essential tyrosine residue 189/319.

Figure 3.

Structural basis of UTP specificity. Key protein-UTP contacts in TUT4-UTP (A) and RET2-UTP (B) complexes. Single metal ions present in TUT4-UTP and RET2-UTP are shown as magenta and black spheres, respectively. Arrows indicate coordinated water molecules participating in uracil base recognition. C. Two-dimensional representation of interactions between the amino acid residues, UTP and water molecules in the TUT4 active site. Reproduced with permission from [17].

Superimposition of the X-ray structures for TbTUT4:UTP and TbRET2:UTP binary complexes (PDB codes 2IKF and 2B56, respectively) showed a nearly identical conformation of the spherical catalytic bi-domain (NTD-CTD) and illustrates the potential of the MD as a protein-protein interaction interface (Figure 1C). The distribution of crucial amino acids between the NTD and CTD pointed out a clear functional distinction between the N-terminal catalytic and C-terminal base recognition domains. The highly conserved NTD bears three universal metal binding carboxylates as well as residues interacting with the triphosphate moiety, a common feature of all NTPs. The specificity for a particular NTP substrate comes from nucleotide base interactions with CTD. The UV-cross-linking studies further established that uracil base interactions with invariant amino acids (N147, S148, Y189, D297, E300, TUT4 numbers) and phosphates contacts, such as hydrogen bonding with S188, are essential for UTP binding. The mutations of metal-coordinating catalytic aspartic residues (D66, D68 and D136, TUT4 numbers) rendered the enzyme inactive but had no effect on UTP binding [17].

7. NTP selectivity of TUTase-like catalytic modules

The concept of a close evolutionary relationship between TUTases and non-canonical poly(A) polymerases (ncPAP) [9] has recently received experimental support. Identification of multiple novel TUTases in activity screens targeting candidate ncPAPs encoded in C. elegans, human and A. thaliana genomes [48], as well as dual A/U specificity of the CID1 protein in S. pombe [49,50] have been reported. The growing list of functions for ncPAPs includes involvement in germ line development in C. elegans [51], S-M checkpoint [50] and adenylation of specific mRNA(s) [52] in S. pombe and cytoplasmic polyadenylation in X. laevis [53], nuclear RNA surveillance [54–56] and others. The common feature of cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerases appears to be the lack of a C-terminal RNA binding domain which is characteristic of nuclear PAPs [51]. Because of low affinity for RNA substrates, Gld-2 and Trf4/5 ncPAPs include an RNA binding factor(s) to tether catalytic subunit to specific mRNA(s) [57]. Conversely, currently characterized TUTases do not require additional subunits for in vitro activity.

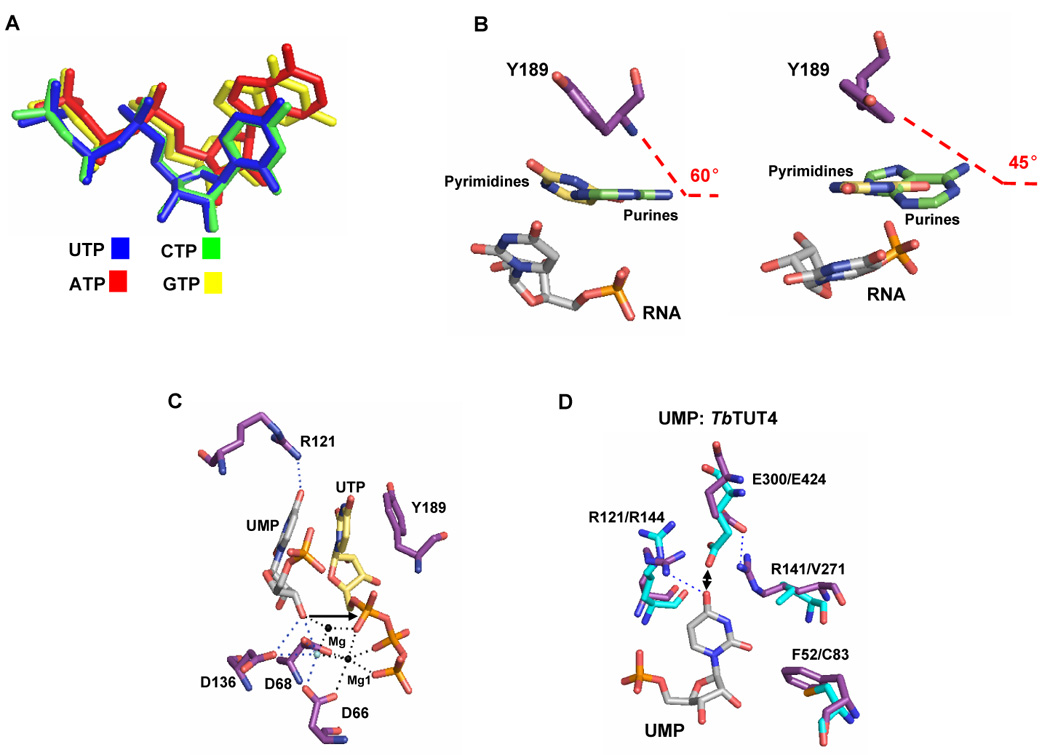

Similarities between TUTases and ncPAPs extend into nucleotide binding site that is thought to determine the base specificity. Indeed, most of the positions involved in uracil base recognition in RET2 and are conserved among TUTases and ncPAPs (Figure 4), which poses a question of how such conserved active site may be fine-tuned to select a different NTPs. At partial solution came from structural analysis of TUT4 binary complexes with ATP, CTP and GTP [58]. The X-ray structures obtained from TUT4-ATP, -CTP or -GTP co-crystals demonstrated nearly perfect superposition of the triphosphate moieties (Figure 5A) while revealing a major reduction in the co-planarity of purine bases with the phenyl ring of conserved Y189, relative to that of pyrimidines (Figure 5B). The shift of purine base positioning diminishes the stacking interaction with Y189. This finding is consistent with TUT4’s intrinsic capacity to discriminate UTP from non-cognate substrates at low NTP concentrations used in the crosslinking experiments [17], but does not fully explain the enzyme’s ability to discriminate against purine NTPs at physiological concentrations.

Figure 5.

NTP and RNA binding by catalytic modules of TUTases. A. Relative positions of rNTPs derived from superpositioning TUT4:UTP, TUT4:CTP, TUT4:ATP and TUT4:GTP structures. B. Triple-stacking interaction of conserved phenyl residues, bound UTP and 3′ terminal nucleoside of RNA. Stacking of the Y189 aromatic ring with uracil or adenosine and UMP acting as RNA is shown with purine (left) or pyrimidine (right) bases orthogonal to the viewing field. C. Relative positioning of the tyrosine-UTP-UMP “triple-sandwich” and catalytic site in TUT4. Arrow indicates the RNA’s 3′ hydroxyl group positioned for in-line attack on α- phosphorus of UTP. D. Superposition of the TUT4:UTP:UMP (PDB code 2IKF) and RET2:UTP (PDB code 2B51) crystal structures. Key residues of TUT4 (purple) and RET2 (cyan) are indicated. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dotted lines. Double-arrow shows potential electrostatic clash. Reproduced with permission from [58].

Further studies with mono- and di-nucleotide model RNA substrates, UMP and UpU, demonstrated that the terminal base of the RNA substrate forms a “triple-stacked sandwich” with the bound UTP base and the phenyl ring of Y189, which poises its 3′ hydroxyl group for in-line attack on the α-phosphorus atom (Figure 5C). In contrast, the observed positioning of purine bases in ATP- and GTP–bound structures shows a reduction in the stacking interaction and relative translation of the purine base, which destabilizes binding of the RNA’s 3′ end. In TUT4- UTP-UpU structure, the terminal and penultimate RNA nucleosides interact via hydrogen bonding with a cluster of positively charged amino acids R121 (Figure 5C), R141, R307 and R126 [58], which are essential for RNA binding [17]. Thus, the continuous stacking interactions between a tyrosine side chain, bound NTP and the terminal base of the RNA, which is tightly coordinated by contacts in the vicinity of the active site, are required for productive ternary complex formation. In addition, the 3′ hydroxyl group of UMP completes a binding site for a second catalytic metal ion, which is typically required for the nucleoside transfer reaction, but has not been observed in previously reported TbTUT4:UTP and TbRET2:UTP binary complexes (PDB codes 2IKF and 2B56, respectively) [17,47].

These findings implied that the NTD-CTD bi-domain catalytic modules shared by TUTases and ncPAPs are quite promiscuous in NTP binding. The steric constraints in the active site that preclude ATP or GTP binding do not appear to be a major specificity factor. Rather, the discrimination of non-UTP substrates by TUTases occurs due to the stabilizing effect of a stacking interaction between the terminal RNA base and bound UTP, which increases the catalytic rate for the cognate substrate. From the evolutionary perspective, it is unclear which specificity, UTP or ATP, arose earlier but seemingly small numbers of mutations were needed to convert this module into ATP-specific of ncPAPs, or vice versa. The dissimilar structures of the active sites among eukaryotic PAPs [37], viral [59] PAPs and TUTases/ncPAPs suggest that ATP specificity was acquired by these enzyme families through independent events.

8. RNA substrate specificity

Accuracy and efficiency of RET2-catalyzed U-insertion is crucial for the overall fidelity of RNA editing. The U-insertion is dictated by RET2’s intrinsic selectivity for UTP and not by Watson-Crick interactions of the incoming UTP with purine guiding nucleotides. The base-pairing of added Us with the gRNA enhances the insertion of subsequent Us presumably by restoring the optimal structure of the RET2 substrate. In vitro studies with partially purified editing complex and RNA substrate resembling a putative intermediate at step II, Figure 1 [60], showed that the base-pairing of extended mRNA 5′ cleavage fragment with guiding nucleotides and the thermodynamic stability of RNA helices surrounding the editing site increase the efficiency of the RET2-catalysed reaction [61]. On a single-stranded RNA substrate RET2 displays a strong preference for 3′ terminal purine nucleosides and the reaction is limited to the addition of a single U [15,58].

RNA substrate for RET2 is generated by the endonucleolytic mRNA cleavage leaving a 5′ phosphate on the 3′ fragment. This phosphate is required for RET2 activity, which may reflect mechanistic and evolutionary similarities between RNA editing and base excision DNA repair (reviewed in [62]). Gapped DNA substrates generated by the AP endonuclease are targeted by the repair enzyme DNA polymerase β and the recognition of the 5′ phosphate is critical for polymerase activity [63]. Furthermore, the 5′ fragment is processively extended only if the gap does not exceed five nucleotides. RET2 and Pol β share the core fold of the N-terminal domain and nucleoside transfer chemistry but clearly rely on distinct mechanisms of NTP selection: uracil binding at the selective site in the former and the template-dependent reaction catalyzed by the latter (see below and [62]). It is quite possible that the conservation of catalytic mechanism extends beyond the chemistry of the nucleoside transfer and includes specific binding to gapped nucleic acids hallmarked by 5′ phosphate group on the 3′ fragment. Interestingly, the 3′–5′ U-specific exonucleases of the 20S editosome possess an AP endo/exonuclease domain found in the DNA repair abasic endonuclease [12,31,64].

Processive TUTases, such as RET1 [36], TUT3 [16] and TUT4 [17] are less specific toward NTP substrates and most active on a single-stranded RNAs ending with Us (Figure 2B). Conversely, RET2 is exquisitely UTP-specific and prefers purines at the 3′ end of RNA substrate [58]. Selectivity of TUT4 and RET2 toward the terminal RNA base is dictated by stabilizing effects of direct hydrogen bonding with conserved residues in the vicinity of the UTP binding sites, as well as destabilizing steric hindrance effects (Figure 5D). In the TUT4-UTP-UMP tertiary complex, the arginine at position 141, which is conserved among processive trypanosomal TUTases, is locked in a salt bridge with E300. As a result, the glutamate 300 no longer coordinates a crucial water molecule (Wat 28, Figure 3C) that makes a uracil base-specific contact [17, 47]. The position corresponding to TUT4’s R141 is occupied by a valine in RET2 (Figure 5D). A smaller valine residue may provide a more spacious binding site for the 3′ terminal adenosine. Another effect of valine occupying the position 271 is differential positioning of the conserved glutamate, E424 (E300 in TbTUT4). In RET2 glutamate 424 plays a dual role: selecting adenosine over uridine as the terminal RNA nucleoside via hydrogen bonding with the exocyclic amino group (Figure 5D) and coordinating, together with D421, the critical water molecule, which accepts a hydrogen bond from position N3 of the UTP (Figure 3B). In TUT4, this water molecule (Wat 28, Figure 3C) is coordinated by one carboxyl residue (D297) and another water molecule (Wat 180), which may explain its lower selectivity (Figure 1B). Arginine 121 is essential for TUT4 activity [17] and acts as a positive determinant for terminal RNA uracil binding while discriminating against adenosine. The phenylalanine in position 52 of TUT4 is conserved in RET1 and TUT3 and most other TUTases (Figure 4). It is essential for activity in TUT4 [17], but is replaced by a cysteine in RET2, perhaps further enhancing binding of a purine base of an RNA substrate.

These TUT4-based models may explain why RET2 adds only a single uridylyl residue to single-stranded RNA substrate but, at the same time, create two conceptual problems: 1) RET2 substrates in vivo are thought to be two double-stranded RNAs linked by purine guiding nucleosides (Figure 2); 2) insertion of up to 12 Us in a single editing site occurs in trypanosomes. The TUT4-UTP-UMP structure with modeled second U-residue of RNA primer shows that the penultimate nucleoside is flipped out of the “triple sandwich” (tyrosine phenyl ring, uracil of bound UTP and terminal RNA base) and is oriented toward the exit from the UTP binding crevice [58]. This model is consistent with mapping of RNA binding contacts by mutational analysis of conserved arginine residues in TUT4 [17]. The spatial positioning of the terminal RNA nucleoside leaves no possibility for base-pairing with guiding purines (Figure 5D), while the penultimate residue may be involved in such interactions. Consequently, during U-insertion the 5′ cleavage fragment must be kinked and the terminal nucleoside disengaged from base-pairing with guide RNA, which is probably compensated by extensive protein-RNA hydrogen bonding and RNA-UTP stacking. Since RET2 is also likely to bind the 3′ end of the 5′ cleavage fragment and the phosphorylated 3′ fragment, guiding nucleotides should loop out into the solution. The high entropy cost of tethering the 3′ hydroxyl and 5′ phosphate in close proximity may explain the loss of recombinant RET2 activity on substrates with more than three guiding nucleosides (I. Aphasizheva and R. Aphasizhev, unpublished). Upon U-addition, the extended 5′ fragment should retract from the active site to allow now-penultimate base to re-anneal with the gRNA. The driving force of the translocation is unclear but the full dissociation of RET2 from RNA substrate appears unlikely. If the added U does not base-pair with gRNA, a mismatched addition product becomes a single-stranded overhang, and therefore a sub-optimal substrate for the RNA editing ligase which preferentially acts on single-stranded nicks in the double-stranded RNA [65].

9. Outlook

Mitochondrial mRNA processing in Trypanosome mitochondria is a multi-step process involving cleavage of multicistronic precursors, polyadenylation and insertion/deletion editing. The editing is directed by guide RNAs via non-templated mechanisms that rely on RNA (endonuclease, TUTase and RNA ligase) and UTP (TUTase) specificities of individual enzymes organized in a multi-protein complex. Unlike endonucleases, exonucleases and RNA ligases, RET2 is the only enzyme which does not have homologs in the 20S editosome, which makes it an attractive system to study how a conserved catalytic module shared by ncPAPs and TUTases could have been recruited to perform a highly-specialized function in RNA editing. As we learn more about TUTases in Kinetoplastida and Metazoans, questions arise of how conserved are the mechanisms of UTP recognition. Editing TUTases are essential for parasite’s viability and available high-resolution X-ray structures render RET2 and TUT4 attractive targets for drug development. Inhibitors targeting the UTP binding site may also block non-editing TUTase and ncPAPs in trypanosomes. The prospect of TUTase-based trypanocides, however, will depend on structural and biochemical characterization of human TUTases and our ability to find highlyspecific inhibitors that are not toxic to humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant AI064653 to RA. We gratefully acknowledge collaboration with Hartmut Luecke and Jason Stagno in structural studies of trypanosomal TUTases. We thank members of our laboratory for stimulating discussion and reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Steitz TA. DNA polymerases: structural diversity and common mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:17395–17398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iyer LM, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Evolutionary connection between the catalytic subunits of DNA-dependent RNA polymerases and eukaryotic RNA-dependent RNA polymerases and the origin of RNA polymerases. BMC. Struct. Biol. 2003;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aravind L, Koonin EV. DNA polymerase beta-like nucleotidyltransferase superfamily: identification of three new families, classification and evolutionary history. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1609–1618. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.7.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holm L, Sander C. DNA polymerase beta belongs to an ancient nucleotidyltransferase superfamily. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:345–347. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin G, Keller W. Mutational analysis of mammalian poly(A) polymerase identifies a region for primer binding and catalytic domain, homologous to the family X polymerases, and to other nucleotidyltransferases. EMBO J. 1996;15:2593–2603. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raynal LC, Carpousis AJ. Poly(A) polymerase I of Escherichia coli: characterization of the catalytic domain, an RNA binding site and regions for the interaction with proteins involved in mRNA degradation. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;32:765–775. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gershon PD, Ahn BY, Garfield M, Moss B. Poly(A) polymerase and a dissociable polyadenylation stimulatory factor encoded by vaccinia virus. Cell. 1991;66:1269–1278. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aphasizhev R, Sbicego S, Peris M, Jang SH, Aphasizheva I, Simpson AM, Rivlin A, Simpson L. Trypanosome Mitochondrial 3′ Terminal Uridylyl Transferase (TUTase): The Key Enzyme in U-insertion/deletion RNA Editing. Cell. 2002;108:637–648. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aphasizhev R. RNA uridylyltransferases. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:2194–2203. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5198-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson L, Sbicego S, Aphasizhev R. Uridine insertion/deletion RNA editing in trypanosome mitochondria: A complex business. RNA. 2003;9:265–276. doi: 10.1261/rna.2178403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stuart KD, Schnaufer A, Ernst NL, Panigrahi AK. Complex management: RNA editing in trypanosomes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aphasizhev R, Aphasizheva I, Nelson RE, Gao G, Simpson AM, Kang X, Falick AM, Sbicego S, Simpson L. Isolation of a U-insertion/deletion editing complex from Leishmania tarentolae mitochondria. EMBO J. 2003;22:913–924. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panigrahi AK, Schnaufer A, Ernst NL, Wang B, Carmean N, Salavati R, Stuart K. Identification of novel components of Trypanosoma brucei editosomes. RNA. 2003;9:484–492. doi: 10.1261/rna.2194603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aphasizhev R, Aphasizheva I, Simpson L. A tale of two TUTases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:10617–10622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1833120100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ernst NL, Panicucci B, Igo RP, Jr, Panigrahi AK, Salavati R, Stuart K. TbMP57 is a 3′ terminal uridylyl transferase (TUTase) of the Trypanosoma brucei editosome. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1525–1536. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aphasizhev R, Aphasizheva I, Simpson L. Multiple terminal uridylyltransferases of trypanosomes. FEBS Lett. 2004;572:15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stagno J, Aphasizheva I, Rosengarth A, Luecke H, Aphasizhev R. UTP-bound and Apo structures of a minimal RNA uridylyltransferase. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;366:882–899. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grams J, Morris JC, Drew ME, Wang ZF, Englund PT, Hajduk SL. A trypanosome mitochondrial RNA polymerase is required for transcription and replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:16952–16959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200662200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koslowsky DJ, Yahampath G. Mitochondrial mRNA 3′ cleavage polyadenylation and RNA editing in Trypanosoma brucei are independent events. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1997;90:81–94. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blum B, Bakalara N, Simpson L. A model for RNA editing in kinetoplastid mitochondria: "Guide" RNA molecules transcribed from maxicircle DNA provide the edited information. Cell. 1990;60:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90735-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clement SL, Mingler MK, Koslowsky DJ. An intragenic guide RNA location suggests a complex mechanism for mitochondrial gene expression in Trypanosoma brucei. Eukaryot. Cell. 2004;3:862–869. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.4.862-869.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blum B, Simpson L. Guide RNAs in kinetoplastid mitochondria have a nonencoded 3′ oligo-(U) tail involved in recognition of the pre-edited region. Cell. 1990;62:391–397. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90375-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson L, Aphasizhev R, Gao G, Kang X. Mitochondrial proteins and complexes in Leishmania and Trypanosoma involved in U-insertion/deletion RNA editing. RNA. 2004;10:159–170. doi: 10.1261/rna.5170704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abraham J, Feagin J, Stuart K. Characterization of cytochrome c oxidase III transcripts that are edited only in the 3′ region. Cell. 1988;55:267–272. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Decker CJ, Sollner-Webb B. RNA editing involves indiscriminate U changes throughout precisely defined editing domains. Cell. 1990;61:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90065-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sturm NR, Simpson L. Partially edited mRNAs for cytochrome b and subunit III of cytochrome oxidase from Leishmania tarentolae mitochondria: RNA editing intermediates. Cell. 1990;61:871–878. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90197-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochsenreiter T, Hajduk SL. Alternative editing of cytochrome c oxidase III mRNA in trypanosome mitochondria generates protein diversity. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:1128–1133. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aphasizhev R, Aphasizheva I, Nelson RE, Simpson L. A 100-kD complex of two RNA-binding proteins from mitochondria of Leishmania tarentolae catalyzes RNA annealing and interacts with several RNA editing components. RNA. 2003;9:62–76. doi: 10.1261/rna.2134303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller UF, Lambert L, Goringer HU. Annealing of RNA editing substrates facilitated by guide RNA-binding protein gBP21. EMBO J. 2001;20:1394–1404. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carnes J, Trotter JR, Ernst NL, Steinberg A, Stuart K. An essential RNase III insertion editing endonuclease in Trypanosoma brucei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:16614–16619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506133102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang X, Rogers K, Gao G, Falick AM, Zhou S, Simpson L. Reconstitution of uridine-deletion precleaved RNA editing with two recombinant enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:1017–1022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409275102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trotter JR, Ernst NL, Carnes J, Panicucci B, Stuart K. A deletion site editing endonuclease in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Cell. 2005;20:403–412. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carnes J, Trotter JR, Peltan A, Fleck M, Stuart K. RNA Editing in Trypanosoma brucei requires three different editosomes. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1128/MCB.01374-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schnaufer A, Ernst NL, Palazzo SS, O'Rear J, Salavati R, Stuart K. Separate Insertion and Deletion Subcomplexes of the Trypanosoma brucei RNA Editing Complex. Mol Cell. 2003;12:307–319. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cruz-Reyes J, Zhelonkina AG, Huang CE, Sollner-Webb B. Distinct functions of two RNA ligases in active Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:4652–4660. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4652-4660.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aphasizheva I, Aphasizhev R, Simpson L. RNA-editing terminal uridylyl transferase 1: identification of functional domains by mutational analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:24123–24130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin G, Moglich A, Keller W, Doublie S. Biochemical and structural insights into substrate binding and catalytic mechanism of mammalian poly(A) polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;341:911–925. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keller W, Martin G. Gene regulation: reviving the message. Nature. 2002;419:267–268. doi: 10.1038/419267a. 419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogozin IB, Aravind L, Koonin EV. Differential action of natural selection on the N and C-terminal domains of 2′–5′oligoadenylate synthetases and the potential nuclease function of the C-terminal domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;326:1449–1461. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Militello KT, Read LK. UTP-dependent and -independent pathways of mRNA turnover in Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20:2308–2316. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.7.2308-2316.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryan CM, Read LK. UTP-dependent turnover of Trypanosoma brucei mitochondrial mRNA requires UTP polymerization and involves the RET1 TUTase. RNA. 2005;11:763–773. doi: 10.1261/rna.7248605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cruz-Reyes J, Rusche L, Piller KJ, Sollner-Webb B, brucei T. RNA editing: adenosine nucleotides inversely affect U-deletion and U-insertion reactions at mRNA cleavage. Mol. Cell. 1998;1:401–409. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang CE, Cruz-Reyes J, Zhelonkina AG, O'Hearn S, Wirtz E, Sollner-Webb B. Roles for ligases in the RNA editing complex of Trypanosoma brucei: band IV is needed for U-deletion and RNA repair. EMBO J. 2001;20:4694–4703. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang CE, O'Hearn SF, Sollner-Webb B. Assembly and function of the RNA editing complex in Trypanosoma brucei requires band III protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:3194–3203. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.9.3194-3203.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Law JA, Huang CE, O'Hearn SF, Sollner-Webb B. In Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing, band II enables recognition specifically at each step of the U insertion cycle. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:2785–2794. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2785-2794.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Hearn SF, Huang CE, Hemann M, Zhelonkina A, Sollner-Webb B. Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing complex: band II is structurally critical and maintains band V ligase, which is nonessential. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:7909–7919. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7909-7919.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deng J, Ernst NL, Turley S, Stuart KD, Hol WG. Structural basis for UTP specificity of RNA editing TUTases from Trypanosoma brucei. EMBO J. 2005;24:4007–4017. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kwak JE, Wickens M. A family of poly(U) polymerases. RNA. 2007;13:860–867. doi: 10.1261/rna.514007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rissland OS, Mikulasova A, Norbury CJ. Efficient RNA polyuridylation by noncanonical poly(a) polymerases. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;27:3612–3624. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02209-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Read RL, Martinho RG, Wang SW, Carr AM, Norbury CJ. Cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerases mediate cellular responses to S phase arrest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:12079–12084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192467799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang L, Eckmann CR, Kadyk LC, Wickens M, Kimble J. A regulatory cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2002;419:312–316. doi: 10.1038/nature01039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saitoh S, Chabes A, McDonald WH, Thelander L, Yates JR, Russell P. Cid13 is a cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase that regulates ribonucleotide reductase mRNA. Cell. 2002;109:563–573. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barnard DC, Ryan K, Manley JL, Richter JD. Symplekin and xGLD-2 are required for CPEB-mediated cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Cell. 2004;119:641–651. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.LaCava J, Houseley J, Saveanu C, Petfalski E, Thompson E, Jacquier A, Tollervey D. RNA degradation by the exosome is promoted by a nuclear polyadenylation complex. Cell. 2005;121:713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vanacova S, Wolf J, Martin G, Blank D, Dettwiler S, Friedlein A, Langen H, Keith G, Keller W. A new yeast poly(A) polymerase complex involved in RNA quality control. PLoS. Biol. 2005;3:e189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wyers F, Rougemaille M, Badis G, Rousselle JC, Dufour ME, Boulay J, Regnault B, Devaux F, Namane A, Seraphin B, Libri D, Jacquier A. Cryptic pol II transcripts are degraded by a nuclear quality control pathway involving a new poly(A) polymerase. Cell. 2005;121:725–737. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kwak JE, Wang L, Ballantyne S, Kimble J, Wickens M. Mammalian GLD-2 homologs are poly(A) polymerases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:4407–4412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400779101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stagno J, Aphasizheva I, Aphasizhev R, Luecke H. Dual Role of the RNA Substrate in Selectivity and Catalysis by Terminal Uridylyl Transferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14634–14639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704259104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moure CM, Bowman BR, Gershon PD, Quiocho FA. Crystal structures of the vaccinia virus polyadenylate polymerase heterodimer: insights into ATP selectivity and processivity 1. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Igo RP, Palazzo SS, Burgess ML, Panigrahi AK, Stuart K. Uridylate addition and RNA ligation contribute to the specificity of kinetoplastid insertion RNA editing. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20:8447–8457. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.22.8447-8457.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Igo RP, Jr, Lawson SD, Stuart K. RNA sequence and base pairing effects on insertion editing in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1567–1576. doi: 10.1128/mcb.22.5.1567-1576.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beard WA, Wilson SH. Structure and mechanism of DNA polymerase Beta. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:361–382. doi: 10.1021/cr0404904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Prasad R, Beard WA, Wilson SH. Studies of gapped DNA substrate binding by mammalian DNA polymerase beta. Dependence on 5′-phosphate group. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:18096–18101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kang X, Gao G, Rogers K, Falick AM, Zhou S, Simpson L. Reconstitution of full-round uridine-deletion RNA editing with three recombinant proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:13944–13949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604476103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blanc V, Aphasizhev R, Alfonzo JD, Simpson L. The mitochondrial RNA ligase from Leishmania tarentolae can join RNA molecules bridged by a complementary RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:24289–24296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J. T-Coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;302:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Trippe R, Guschina E, Hossbach M, Urlaub H, Luhrmann R, Benecke BJ. Identification, cloning, and functional analysis of the human U6 snRNA-specific terminal uridylyl transferase 1. RNA. 2006;12:1494–1504. doi: 10.1261/rna.87706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]