Abstract

Polypyrimidine-tract binding protein (PTB) is an RNA binding protein with multiple functions in the regulation of RNA processing and IRES-mediated translation. We report here overexpression of PTB in a majority of epithelial ovarian tumors revealed by immunoblotting and tissue microarray (TMA) staining. By Western Blotting, we found that PTB was overexpressed in 17out of 19 ovarian tumor specimens compared to their matched normal tissues. By TMA staining, we found PTB expression in 38 out of 44 ovarian cancer cases but only in 2 out of 9 normal adjacent tissues. PTB is also overexpressed in SV40 large T antigen immortalized ovarian epithelial cells compared to normal human ovarian epithelial cells. Using doxycycline-inducible small interfering RNA technology, we found that knockdown of PTB expression in the ovarian tumor cell line A2780 substantially impaired tumor cell proliferation, anchorage-independent growth and in vitro invasiveness. These results suggest that overexpression of PTB is an important component of the multi-step process of tumorigenesis, and might be required for the development and maintenance of epithelial ovarian tumors. Moreover, because of its novel role in tumor cell growth and invasiveness, shown here for the first time, PTB may be a novel therapeutic target in the treatment of ovarian cancer.

Keywords: Epithelial ovarian cancer, polyprimidine tract-binding protein, RNA interference, tissue microarray, tumorigenesis

Introduction

Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein (PTB) is a member of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein family (also known as hnRNP I) with multiple functions. It was originally identified as a protein that bound to the pyrimidine-rich region within introns of pre-mRNA and was proposed as a splicing factor (Garcia-Blanco et al., 1989; Wang & Pederson, 1990). It is now widely believed that PTB functions as a negative regulator of pre-mRNA splicing, blocking the inclusion of numerous alternative exons into mRNA (Black, 2003), including its own exon (Wollerton et al., 2004). Besides roles in splicing, PTB has also been implicated in the regulation of other aspects of RNA metabolism, such as pre-mRNA polyadenylation (Castelo-Branco et al., 2004), mRNA stability (Knoch et al., 2004; Kosinski et al., 2003), mRNA export from the nucleus (Zang et al., 2001) and mRNA localization in the cytoplasm (Cote et al., 1999). In addition, PTB is involved in the control of cap-independent translation driven by the internal ribosomal entry site (IRES). PTB can bind the IRESs of viral and cellular mRNAs and either positively or negatively influences the IRES activity (Cornelis et al., 2005; Mitchell et al., 2001).

PTB is widely expressed in many cells and tissues. It is mainly localized to the nucleus and distributed diffusely throughout the nucleoplasm with high concentration in a nuclear structure called the perinucleolar compartment (PNC) (Matera et al., 1995), which is much more prevalent in tumor cells than in normal cells (Huang et al., 1997). Recently, it has been reported that higher PNC prevalence significantly correlates with higher malignancy and poorer prognosis of breast cancer (Kamath et al., 2005).

We previously observed that human ovarian tumors overexpressed PTB and another splicing factor, SRp20, compared to matched normal ovarian tissues. Correspondingly, we found more splice variants of the multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1) as well as CD44 in ovarian tumors than in matched normal ovarian tissues (He et al., 2004). It remains to be determined whether these two splicing factors directly participate in the splicing of the MRP1 and CD44 genes. Others found that overexpression of PTB in glioblastoma tissues coincided with the increased exclusion of the α-exon of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 in transformed glial cells (Jin et al., 2003; Jin et al., 2000). Nevertheless, it is unknown whether PTB plays any functional role in tumor progression.

In this report, we expanded our previous observation to more ovarian cancer specimens and confirmed the overexpression of PTB in ovarian tumors at the cellular level. We also show that knockdown of PTB expression by small interfering RNA (siRNA) substantially impairs ovarian tumor cell growth, colony formation, and invasiveness in vitro.

Results

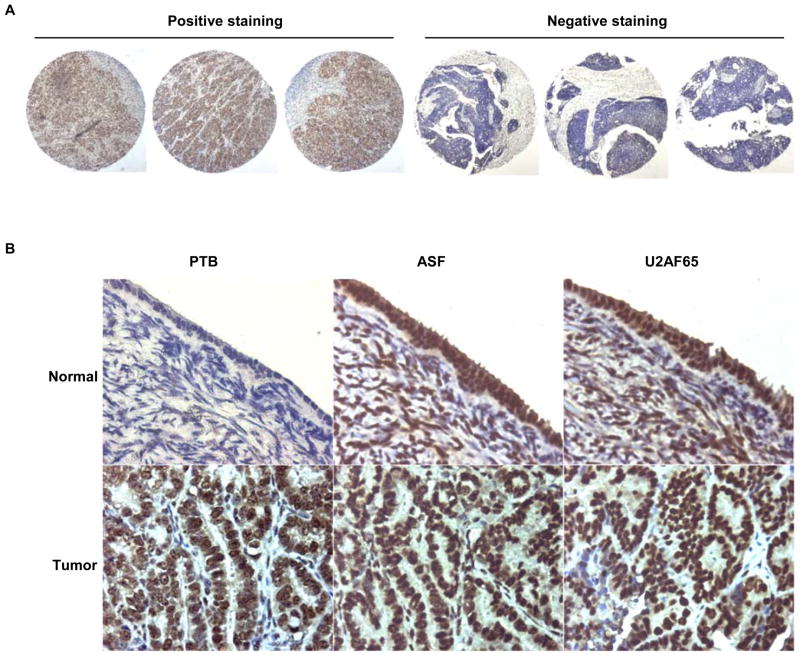

Immunohistochemical staining of tissue microarrays (TMAs) for PTB

We confirmed our previous observation that PTB was overexpressed in human epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) by Western Blotting of another 19 pairs of matched ovarian tumor and normal tissues and showing overexpression of PTB in 17 pairs (Supplemetal Data Fig. S1). In order to compare PTB expression at the cellular level between normal ovarian epithelia and ovarian tumors, we performed immunohistochemical staining for PTB on an ovarian tumor TMA that contained tissue spots of 48 cases of advanced EOC and 13 cases of normal adjacent ovarian tissues. After staining, 44 cancer cases and 11 normal cases were judged valid and analyzed further. Our rule for valid cases was that there were a minimum of 2 satisfactory cores for cancer and 1 satisfactory core for normal ovary. Unsatisfactory cases were those with missing core(s), scant/insufficient tumor cells, and increased background or folded/wrinkled/torn sections. Overall, the stainings of three cores of a case were very similar, as exemplified in Fig. 1A. Out of 44 valid cancer cases, 33 had score differences no greater than 1 both in intensity and in frequency among three cores, indicating that staining was reliable and unbiased.

Fig 1.

PTB is overexpressed in EOC. A. Examples of homogeneous staining among the three cores of each case in TMA. Shown is the staining for PTB. B. Immunohistochemical staining for PTB and two other splicing factors, ASF and U2AF65, on human EOC TMA. Arrows indicate ovarian surface epithelial cells. Note negative PTB staining in normal ovarian epithelial cells. Magnification, 600X

The staining for PTB in the majority of ovarian tumor tissues was positive and strong while in most normal ovarian tissues the staining was negative. Fig. 1B shows examples of PTB staining in tumor and normal ovarian tissues. The results of the staining are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical staining for PTB in EOC TMA

| Negative | Positive | Mixed | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovarian Tumors | 6 (13.6%) | 33 (75%) | 5 (11.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Adjacent Normal Ovaries | 9 (81.8%) | 2 (18.2%) | 0 (0%) |

Statistical significance was evaluated using Pearson’s Chi-Square test

We note that most normal tissues contained only stromal cells, and only one retained surface epithelium. In this case, we found that the staining of normal epithelium for PTB was negative, while staining for two other splicing factors, ASF/SF2 and U2AF65, was very strong (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the staining for all three splicing factors was very strong in tumors (Fig. 1B). This result suggests that the overexpression of splicing factors in EOC compared to normal ovarian epithelium is not universal; indeed, overexpression of PTB in EOC appears to be unique in this disease. In support of this observation, we also stained sixteen conventional normal ovarian tissue sections with some surface epithelia retained and ten epithelial ovarian tumor tissue sections for PTB and confirmed above observation, i.e., the staining of normal ovarian surface epithelia was negative or very weak positive while that of EOC was strong positive (data not shown).

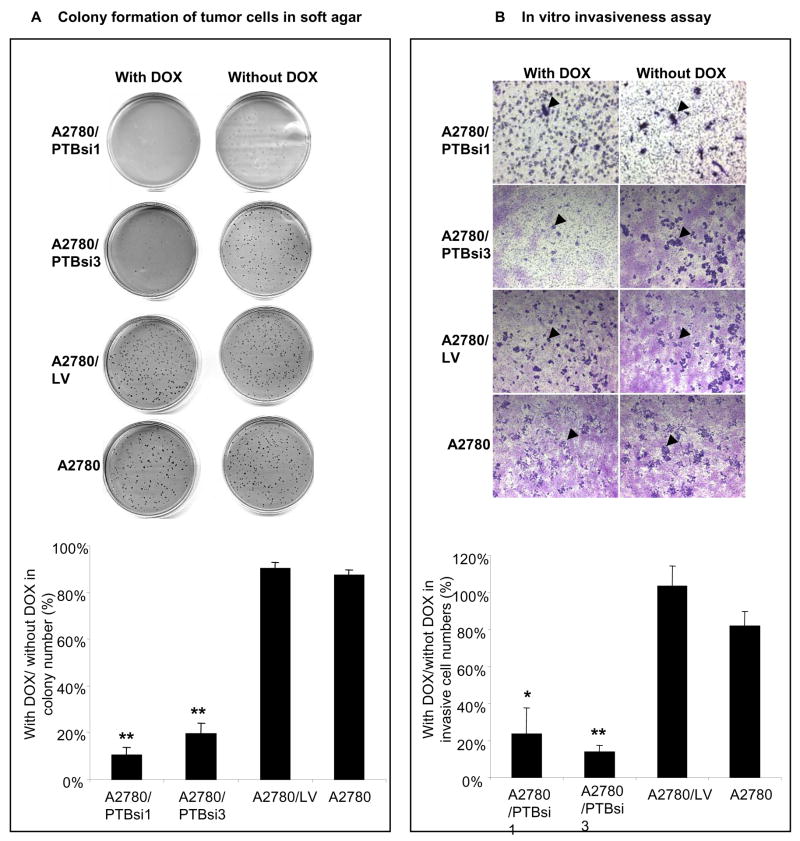

Immortalization of ovarian epithelial cells increases the expression of PTB

The observation that normal ovarian tissues express low levels of PTB compared to ovarian tumors raised the question of when during oncogenesis this splicing factor becomes overexpressed. Hence, we examined by Western Blotting the expression of PTB in normal human ovarian surface epithelia (HOSE), life-extended HOSE (IOSE398) (Maines-Bandiera et al., 1992), truly immortalized HOSE (IOSE120T) (Liu et al., 2004) and ovarian epithelial tumor cell lines PA-1, SKOV3, OVCAR8 and A2780. As shown in Fig. 2A, the expression of PTB is substantially overexpressed in life-extended IOSE398 cells and maintained at high levels in IOSE120T and ovarian tumor cell lines, compared to normal HOSE cells. Further, we compared the PTB levels at different passages of IOSE398 cells, which senesce at around passage 20. As can be seen in Fig. 2B, PTB levels were gradually reduced when cells were approaching senescence. These results suggest that the up-regulation of PTB is an early event in the neoplastic transformation of ovarian epithelial cells and might be required for cell growth. In support of this notion, we found by staining an ovarian disease-progression TMA that the expression levels of PTB are highest in invasive ovarian tumors, lowest in benign ovarian tumors and in between in borderline/low malignant potential ovarian tumors (data not shown).

Fig 2.

PTB is overexpressed in immortalized HOSE cells and ovarian tumor cell lines. A. Immunoblotting analysis of PTB expression in cell lines. B: PTB expression in IOSE398 cells at different passages. Multiple PTB bands are different splice variants of PTB. The expression levels of PTB are quantified as a ratio of PTB to β-actin expression.

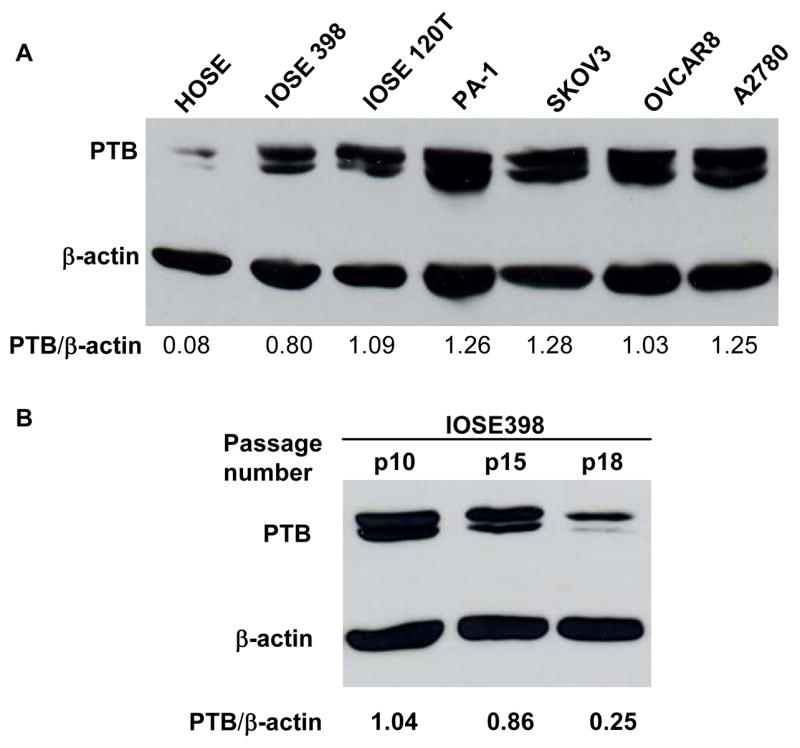

Knockdown of PTB expression by vector-based siRNA

Our above observation raised another question of whether overexpressed PTB plays any functional role(s) in maintaining ovarian tumor cell growth. To address this, we used siRNA technology to knock down the expression of PTB in tumor cells and then examined the effects of such manipulations on cell growth and malignancy, the latter assessed in an in vitro invasiveness assay. In order to significantly knockdown PTB expression, we tested over ten vector-based siRNAs targeting different regions of PTB mRNA and found three to be very effective in suppression of PTB expression. Moreover, the introduction of these three vector-based siRNAs into MCF-7 cells, a breast cancer cell line, also caused suppression of cell growth (see Supplemental Data, Fig. S3). In this study, we chose two of them (PTB small hairpin RNAs 1 and 3 (shRNA1 and shRNA3)) and transferred them individually to a lentiviral vector as described in the Methods and Materials. We then established sublines of the epithelial ovarian tumor cell line A2780 that express tetracycline-inducible PTB siRNA. The sublines (named as A2780/PTBsi1 and A2780/PTBsi3 respectively) carry both expression cassettes of tTR/KRAB-Red and PTB shRNA1 or PTB shRNA3 (Fig. 3A). In the presence of doxycycline (DOX), the fusion protein tTR/KRAB-Red is bound by DOX and dissociated from the tetO, thus unblocking the downstream PTB shRNA, allowing it to be expressed. Shown in Fig. 3B is the expression of PTB at mRNA and protein levels in the absence and presence of DOX. It can be seen that the expression of PTB is controlled by DOX: in the presence of DOX, PTB expression is significantly knocked down at both mRNA and protein levels. In contrast, the expression of PTB in the control subline A2780/LV, which carries LV-tTR/KRAB-Red and the lentiviral vector without PTB shRNA, is not influenced by DOX. In addition, we showed that knockdown of PTB expression by DOX-induced siRNA was not accompanied by non-specific interferon response, a major concern in studies involving siRNAs (see Supplemental Data Fig. S4).

Fig 3.

Knockdown of PTB expression by vector-based DOX-inducible PTB siRNA. A. Schematic structure of lentiviral vectors. B. Expression of PTB at mRNA and protein levels in A2780 sublines carrying tTR/KRAB-Red and THsiPTB (A2780/PTBsi1 and A2780/PTBsi3) in the presence or absence of DOX.

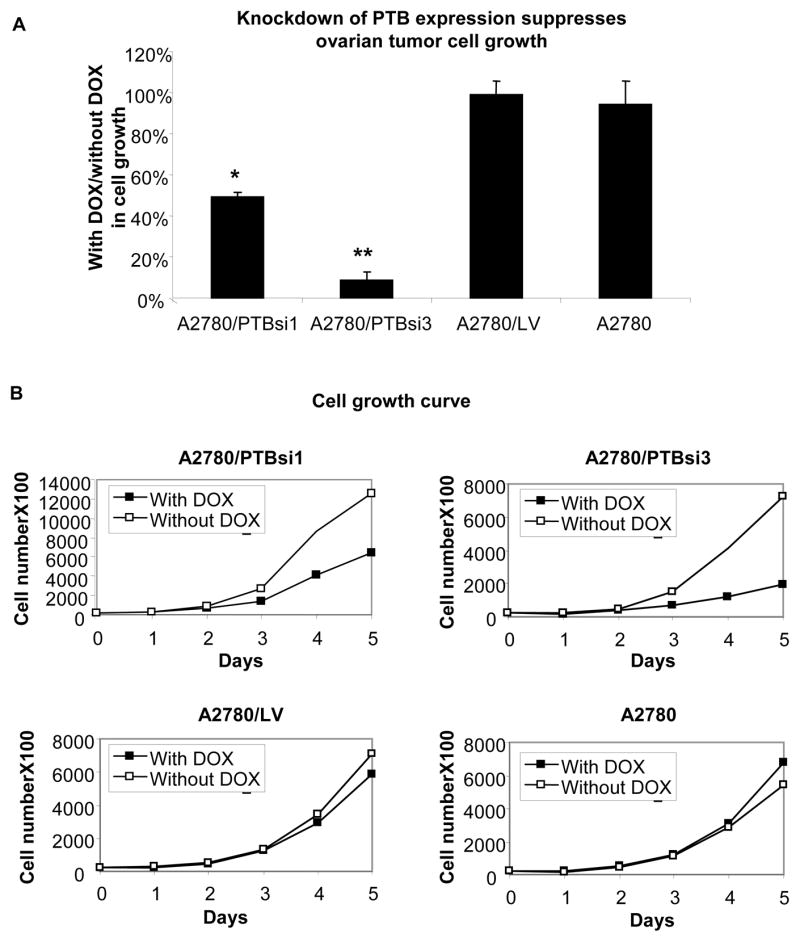

Knockdown of PTB expression suppresses the growth of ovarian tumor cells in Vitro

Using the 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay, we compared the proliferation of A2780/PTBsi1 and A2780/PTBsi3 in the presence and absence of DOX. As shown in Fig. 4A, the growth of A2780/PTBsi3 was suppressed substantially in the presence of DOX, while the control subline A2780/LV, as well as the parental A2780 cells grew similarly in both conditions (with and without DOX). It is worth noting that in the absence of DOX, there is no significant difference in cell growth among the four cell lines, indicating that the introduction of lentiviral vectors into the cell itself did not influence cell growth. We counted cell numbers at 24 h intervals, using a Coulter Counter (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). The result was highly consistent with that obtained by MTT assay. It can be seen in Fig. 4B that A2780/PTBsi1 and A2780/PTBsi3 grows substantially more slowly in the presence of DOX. By contrast, we observed no such difference in the control subline or parental A2780 cells. We also observed similar results in a breast cancer cell line, MCF7, following knockdown of PTB (Supplemental Data Fig. S3), indicating that growth suppression following PTB knockdown is likely a general phenomenon and not confined to one tumor histotype.

Fig 4.

Knockdown of PTB expression suppresses ovarian tumor cell growth. A. MTT assay of cell proliferation. Shown is the average of three separate experiments. Error bars represent the standard error (SE). * and ** indicate P<0.05 and P<0.01, respectively, when compared to either control cell line. D. Cell growth curves. Two separate experiments were done and exhibited similar trends. Shown are the results of one experiment.

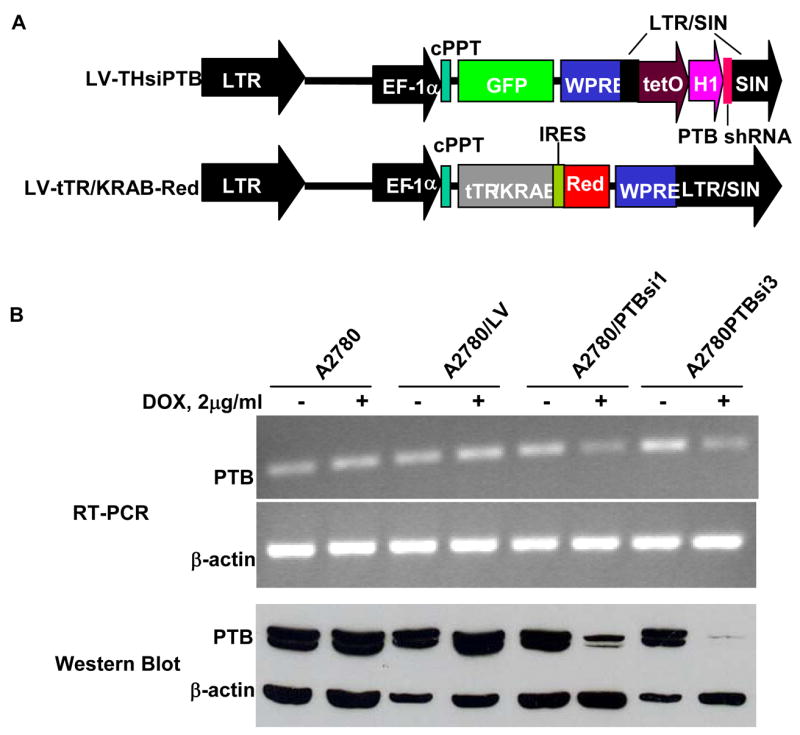

Knockdown of PTB expression decreases the invasiveness of ovarian tumor cells

To determine whether overexpression of PTB makes any contribution to the invasiveness, and therefore, the malignancy of ovarian tumor cells, we examined two malignant properties, anchorage-independent growth (AIG) and invasiveness, in the A2780/PTBsi1 and A2780/PTBsi3 cells when their PTB expression was manipulated by DOX. The AIG of tumor cells was measured by the formation of colonies in soft agar. As shown in Fig. 5A, the colonies formed when A2780/PTBsi1 and A2780/PTBsi3 grown with DOX were only 10.4±3.1% and 19.5±4.4%, respectively, of that formed when grown without DOX, indicating that knockdown of PTB expression substantially impaired the AIG of A2780 cells. By contrast, both the control subline and the parental A2780 cells exhibited little differences in their ability to form colonies in soft agar when grown with DOX and without DOX (The percentages were 90.1±2.9% and 87.4±2.3%, respectively). The invasiveness of tumor cells was measured by their abilities to degrade the basement membrane matrix proteins in the coating layer, which serves as a barrier to discriminate invasive cells from non-invasive cells, and ultimately pass through the pores of a polycarbonate membrane. As shown in Fig. 5B, when A2780/PTBsi1 and A2780/PTBsi3 cells were grown with DOX, the number of invasive cells (indicated by arrows in the figure) was far less (23.5±14.1% and 14.0±3.3%, respectively) than when they were grown without DOX, indicating that knockdown of PTB expression also greatly reduced the invasive potential of A2780 cells. In contrast, DOX treatment produced little or no effect on the invasive abilities of the control cell lines A2780/LV and A2780 (The percentages were 103.3±11% and 81.6±8.0%, respectively).

Fig 5.

Knockdown of PTB expression lowers malignant potential of ovarian tumor cells. A. Colony formation of tumor cells in soft agar. Upper part shows colonies in the soft agar of one experiment and lower part shows average ratios (in percentage) of colony numbers formed with DOX vs without DOX (n=3). B. In vitro invasiveness assay of ovarian tumor cells. Upper part shows invasive cells under microscope (40x) of one experiment and lower part shows average ratios (in percentage) of invasive cells grown with DOX vs without DOX (n=3). Invasive cells were counted under microscope with high magnification (150×). Arrows indicate the invasive cells. * and ** indicate P<0.05 and P<0.01, respectively, when compared to either control cell line. Error bars represent the standard error (SE).

Discussion

In this study, we confirmed our previous observation that PTB was overexpressed in human EOC by immunohistochemical staining of EOC TMA. Moreover, we found that PTB expression was up-regulated in immortalized ovarian epithelial cells as well as in ovarian tumor cell lines, compared to normal or untransformed ovarian epithelial cells, a novel observation. Additionally, we demonstrated that knockdown of PTB expression by siRNA impaired the growth of ovarian tumor cells and diminished their malignant potential. Together, these results suggest to us that overexpression of PTB could be an important component of a multi-step process of tumorigenesis and might be required for the development and maintenance of EOC.

The mechanism that leads to the up-regulation of PTB expression in ovarian tumors remains to be elucidated. Given that PTB expression is increased in SV40 large T antigen (TAg)-transduced OSE cells (see Fig. 2) and TAg disrupts the normal actions of tumor suppressor pRb and p53 (Bryan & Reddel, 1994), it is possible that the expression of PTB is under control of these two proteins. However, since PTB is overexpressed in PA-1, which expresses wild-type p53, as well as in SKOV3, that does not express p53 at all (Jin et al., 2002), p53 probably plays no role in PTB overexpression. Clearly, other pathways cannot be excluded because TAg also interacts with proteins other than pRb and p53 (Kasper et al., 2005).

As indicated in the Introduction, PTB is a key regulator of alternative splicing, and is involved in the repression of inclusion of many alternative exons (Wagner & Garcia-Blanco, 2001). Therefore, overexpression of PTB is very likely to cause alterations in splicing patterns that may have such effects as we have shown herein, and we are presently examining this in our system. Defects in pre-mRNA splicing have been shown to be causes of a variety of human diseases (Faustino & Cooper, 2003). Mounting evidence suggests that altered splicing is associated with and possibly involved in tumor progression and/or metastasis (Venables, 2004). Recent computational analyses, based on alignments of expressed sequence tags (EST) to human RefSeq mRNAs or human genomic DNA, revealed that many alternatively spliced variants were significantly associated with cancer, and the majority of these genes have functions related to cancer (Wang et al., 2003; Xu & Lee, 2003). In general, the direct causes behind the alteration of pre-mRNA splicing can be divided into two categories: mutations in cis-elements and changes in trans-acting factors. At present, it is not clear whether mutations make significant contributions to aberrant splicing found in tumors. Our finding of overexpresssion of PTB in ovarian tumors indicates that aberrant splicing is at least partially due to changes in trans-acting splicing factors. Since pre-mRNA splicing is a complex cellular process involving many other splicing factors, to have a better understanding of why and how splicing patterns change in tumor cells, it is necessary to have a global view of expression of all splicing factors in tumor and normal cells, and some of our current effort is directed to addressing this matter.

Overexpression of PTB in the majority of ovarian tumors raises possibilities that PTB could be a useful biomarker for the diagnosis and/or prognosis of ovarian cancer, or even as a novel therapeutic target. Ovarian cancer is the deadliest disease among all gynecological cancers (Jemal et al., 2003). Two facts account for this dismal outcome: one is the absence of reliable early detection markers; the other is inadequacy of present therapy for advanced disease (Ozols et al., 2004). Therefore, to improve patient survival, it is critical to identify new biomarkers for early detection. Given the current absence of any preventable etiologic factors and effective tools for screening, another way to approach improving patient survival is to discover biomarkers that can lead to a better management of patients after initial diagnosis (Bast et al., 2005). To establish the usefulness of PTB as a biomarker, more work is needed to determine whether there is a correlation among the expression of PTB and subtype, grade and stage of ovarian cancer, as well as clinical outcomes such as therapy response, survival, progression-free survival, and the like. These studies are presently underway in our laboratories and will be reported elsewhere.

The results that knockdown of PTB expression causes suppression of tumor cell proliferation, suppression of AIG, and suppression of invasiveness strongly support the notion that PTB is important in maintaining ovarian tumor cell growth and malignant potential. To our best knowledge, ours is the first report to show such effects. At present, it is not clear what mechanisms mediate these effects. Given the multiple functions of PTB, these effects could be related to changes in alternative splicing, mRNA stability or IRES-driven translation of certain genes. However, current knowledge about the targets of PTB cannot entirely explain our observations. Therefore, it is very likely that there exist some unidentified substrates of PTB that are involved in the maintenance of ovarian tumor cell growth and malignancy by PTB. Despite these gaps in our knowledge, our results support the idea that PTB might have potential as a therapeutic target for the treatment of ovarian cancer, and our laboratories are pursuing these lines of investigation. In addition, we recently performed a microarray analysis comparing controls to cells with PTB knocked-down by siRNA. Our preliminary results, to be detailed elsewhere, have revealed that a number of genes associated with tumor growth and metastasis are down-regulated and a number of genes associated with tumor suppression are up-regulated in PTB-knockdown A2780 cells, supporting the observations in this manuscript.

Finally, a very recent report showed that knockdown of PTB in MCF-7 cells inhibited apoptosis triggered by TRAIL and ectopical expression of PTB in MCF-7 cells caused a small increase in apoptosis (Bushell et al., 2006). These results are somewhat in contrast to what we present here. However, the report did not show whether knockdown of PTB itself affected cell growth. Also it is worth noting that MCF-7 cells already overexpress PTB compared to normal human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC) or non-tumorigenic immortalized HMEC (our unpublished data). Further overexpressing PTB ectopically in MCF-7 cells might cause some artificial phenomena.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and cell culture conditions

These are detailed in the Supplemental Data.

TMA of EOC

TMA slides were obtained from the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) Tissue Bank in Columbus, Ohio. The TMA contained 165 randomly distributed 1 mm cores with 150 cancers and 15 adjacent normal ovaries. Among the cancers, there were 48 cases of advanced stage EOC (25 stage III and 23 stage IV) and one case of uterine adenocarcinoma with up to 3 cores for each case (except one case with 6 cores). Cores of adjacent normal ovarian tissue were from 13 patients with ovarian cancer. Of these, 11 cases had one core for each and 2 cases had two cores for each.

Western Blotting

Western Blotting was performed as previously described (He et al., 2004). The densities of protein bands were measured using software Scion Image (Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD).

Immunohistochemical staining of TMA

The procedure of immunohistochemical staining and its evaluation are described in detail in the Supplemental Data.

Preparation of lentiviruses carrying tetracycline-inducible expression cassette of shRNA

The DNA fragments coding for PTB shRNA1 and 3 were generated by annealing of two pairs of complemetary oligonucleotides. The procedures for cloning of the DNA fragment into the lentiviral vector and for preparation of lentiviruses are detailed in the Supplemental Data.

Establishment of stable cell lines expressing tetracycline-inducible PTB siRNA

We first established cell lines transduced by lentiviruses LV-tTR/KRAB-Red, and then re-infected them with lentiviruses LV-THsiPTB. Clones expressing both red fluorescent protein and GFP were selected and expanded. The regulation by DOX of siRNA expression in these clones was verified by measuring PTB expression by both RT-PCR and Western Blotting.Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was determined using MTT assay. Cell growth curves were obtained by counting cells grown in 24-well plates using a Coulter Counter (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Detailed procedures for these experiments are described in the Supplemental Data.

Soft agar colony formation

The assay was performed in 60mm dishes or 6-well plates that contained two layers of soft agar. The top and bottom layers were 0.3% and 0.4% agarose, respectively, in DMEM with 5% FBS. 5000 cells together with or without DOX were added to the top agarose before pouring. Colonies were counted manually after two to three weeks incubation at 37°C, 5% CO2.

In vitro invasiveness assay

The invasive properties of tumor cells were analyzed using CytoSelect™ Cell Invasion Assay kit (Cell Biolabs, Inc., San Diego, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The procedure is described in detail in the Supplemental Data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Didier Trono (University of Geneva, Switzerland) for his generous gift of lentiviral vectors LV-THM and LV-tTR/KRAB-Red as well as plasmids pMD2.g, pMDLg/pRRE and pRSV Rev. We are most grateful to our colleague, Martina Vaskova, for her outstanding administrative, technical, and intellectual assistance. Finally, we thank the GOG tumor bank for the EOC TMA. This work was supported by the GOG (a subcontract to WTB), the National Cancer Institute (WTB), and the University of Illinois at Chicago. It was conducted in a facility constructed with support from the NCRR NIH grant C06RR15482.

References

- Bast RC, Jr, Lilja H, Urban N, Rimm DL, Fritsche H, Gray J, et al. Translational crossroads for biomarkers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6103–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DL. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan TM, Reddel RR. SV40-induced immortalization of human cells. Crit Rev Oncog. 1994;5:331–57. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v5.i4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushell M, Stoneley M, Kong YW, Hamilton TL, Spriggs KA, Dobbyn HC, et al. Polypyrimidine tract binding protein regulates IRES-mediated gene expression during apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2006;23:401–12. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelo-Branco P, Furger A, Wollerton M, Smith C, Moreira A, Proudfoot N. Polypyrimidine tract binding protein modulates efficiency of polyadenylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4174–83. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4174-4183.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis S, Tinton SA, Schepens B, Bruynooghe Y, Beyaert R. UNR translation can be driven by an IRES element that is negatively regulated by polypyrimidine tract binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3095–108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote CA, Gautreau D, Denegre JM, Kress TL, Terry NA, Mowry KL. A Xenopus protein related to hnRNP I has a role in cytoplasmic RNA localization. Mol Cell. 1999;4:431–7. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustino NA, Cooper TA. Pre-mRNA splicing and human disease. Genes Dev. 2003;17:419–37. doi: 10.1101/gad.1048803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Blanco MA, Jamison SF, Sharp PA. Identification and purification of a 62,000-dalton protein that binds specifically to the polypyrimidine tract of introns. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1874–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12a.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Ee PL, Coon JS, Beck WT. Alternative splicing of the multidrug resistance protein 1/ATP binding cassette transporter subfamily gene in ovarian cancer creates functional splice variants and is associated with increased expression of the splicing factors PTB and SRp20. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4652–60. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Spector DL. The dynamic organization of the perinucleolar compartment in the cell nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:965–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.5.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A, Ghafoor A, Ward E, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:5–26. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W, Bruno IG, Xie TX, Sanger LJ, Cote GJ. Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein down-regulates fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 alpha-exon inclusion. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6154–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W, McCutcheon IE, Fuller GN, Huang ES, Cote GJ. Fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 alpha-exon exclusion and polypyrimidine tract-binding protein in glioblastoma multiforme tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1221–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Burke W, Rothman K, Lin J. Resistance to p53-mediated growth suppression in human ovarian cancer cells retain endogenous wild-type p53. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:659–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RV, Thor AD, Wang C, Edgerton SM, Slusarczyk A, Leary DJ, et al. Perinucleolar compartment prevalence has an independent prognostic value for breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:246–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper JS, Kuwabara H, Arai T, Ali SH, DeCaprio JA. Simian virus 40 large T antigen's association with the CUL7 SCF complex contributes to cellular transformation. J Virol. 2005;79:11685–92. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11685-11692.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoch KP, Bergert H, Borgonovo B, Saeger HD, Altkruger A, Verkade P, et al. Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein promotes insulin secretory granule biogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:207–14. doi: 10.1038/ncb1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski PA, Laughlin J, Singh K, Covey LR. A complex containing polypyrimidine tract-binding protein is involved in regulating the stability of CD40 ligand (CD154) mRNA. J Immunol. 2003;170:979–88. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Yang G, Thompson-Lanza JA, Glassman A, Hayes K, Patterson A, et al. A genetically defined model for human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1655–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maines-Bandiera SL, Kruk PA, Auersperg N. Simian virus 40-transformed human ovarian surface epithelial cells escape normal growth controls but retain morphogenetic responses to extracellular matrix. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:729–35. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91579-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matera AG, Frey MR, Margelot K, Wolin SL. A perinucleolar compartment contains several RNA polymerase III transcripts as well as the polypyrimidine tract-binding protein, hnRNP I. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:1181–93. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.5.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SA, Brown EC, Coldwell MJ, Jackson RJ, Willis AE. Protein factor requirements of the Apaf-1 internal ribosome entry segment: roles of polypyrimidine tract binding protein and upstream of N-ras. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3364–74. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.10.3364-3374.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozols RF, Bookman MA, Connolly DC, Daly MB, Godwin AK, Schilder RJ, et al. Focus on epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:19–24. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables JP. Aberrant and alternative splicing in cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7647–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EJ, Garcia-Blanco MA. Polypyrimidine tract binding protein antagonizes exon definition. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3281–8. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.10.3281-3288.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Pederson T. A 62,000 molecular weight spliceosome protein crosslinks to the intron polypyrimidine tract. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5995–6001. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.5995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Lo HS, Yang H, Gere S, Hu Y, Buetow KH, et al. Computational analysis and experimental validation of tumor-associated alternative RNA splicing in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:655–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollerton MC, Gooding C, Wagner EJ, Garcia-Blanco MA, Smith CW. Autoregulation of polypyrimidine tract binding protein by alternative splicing leading to nonsense-mediated decay. Mol Cell. 2004;13:91–100. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00502-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Lee C. Discovery of novel splice forms and functional analysis of cancer-specific alternative splicing in human expressed sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5635–43. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang WQ, Li B, Huang PY, Lai MM, Yen TS. Role of polypyrimidine tract binding protein in the function of the hepatitis B virus posttranscriptional regulatory element. J Virol. 2001;75:10779–86. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10779-10786.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.