Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Hospital-based data from Africa suggest that newborn skin-cleansing with chlorhexidine may reduce neonatal mortality. Evaluation of this intervention in the communities where most births occur in the home has not been done. Our objective was to assess the efficacy of a 1-time skin-cleansing of newborn infants with 0.25% chlorhexidine on neonatal mortality.

METHODS

The design was a community-based, placebo-controlled, cluster-randomized trial in Sarlahi District in southern Nepal. Newborn infants were cleansed with infant wipes that contained 0.25% chlorhexidine or placebo solution as soon as possible after delivery in the home (median: 5.8 hours). The primary outcome was all-cause mortality by 28 days. After the completion of the randomized phase, all newborns in study clusters were converted to chlorhexidine treatment for the subsequent 9 months.

RESULTS

A total of 17 530 live births occurred in the enrolled sectors, 8650 and 8880 in the chlorhexidine and placebo groups, respectively. Baseline characteristics were similar in the treatment groups. Intention-to-treat analysis among all live births showed no impact of the intervention on neonatal mortality. Among live-born infants who actually received their assigned treatment (98.7%), there was a nonsignificant 11% lower neonatal mortality rate among those who were treated with chlorhexidine compared with placebo. Low birth weight infants had a statistically significant 28% reduction in neonatal mortality; there was no significant difference among infants who were born weighing ≥2500 g. After conversion to active treatment in the placebo clusters, there was a 37% reduction in mortality among low birth weight infants in the placebo clusters versus no change in the chlorhexidine clusters.

CONCLUSIONS

Newborn skin-wiping with chlorhexidine solution once, soon after birth, reduced neonatal mortality only among low birth weight infants. Evidence from additional trials is needed to determine whether this inexpensive and simple intervention could improve survival significantly among low birth weight infants in settings where home delivery is common and hygiene practices are poor.

Keywords: chlorhexidine, mortality, neonatal, Nepal

DEVELOPING COUNTRIES HAVE made significant progress in reducing mortality for children who are younger than 5 years through the implementation of a variety of maternal and child health interventions in the past 3 decades. Little progress has been made, however, in reducing perinatal and neonatal mortality,1,2 and neonatal deaths now comprise nearly 40% of all mortality in children who are younger than 5 years.3 Ninety-nine percent of neonatal deaths occur in developing countries, mostly at home, and are attributable primarily to infections, birth asphyxia, and complications of prematurity.3,4 Low birth weight (LBW) is an important underlying factor for neonatal mortality and contributes to an estimated 60% to 80% of neonatal deaths in low-resource settings.1 LBW is particularly important in south Asia, where the prevalence is ∼30%.2 Recent research suggests that improved care of LBW infants has the potential to improve survival significantly.5,6

Early neonatal sepsis is associated with colonization of infant skin by organisms that are present in the vaginal canal. This is supported by studies from developed countries that demonstrated reduced neonatal colonization when the vaginal canal is cleansed with antiseptic solution.7–13 Two hospital-based studies from developing countries also have addressed this issue. In nonrandomized, unmasked trials that were conducted in Malawi14 and Egypt,15 pregnant women received vaginal cleansing with 0.25% chlorhexidine during labor and their newborns were given full-body skin-cleansing with the same solution. Compared with nonintervention time periods, neonatal mortality was reduced 22% in Malawi and 33% in Egypt. However, the combination of treatment to both mother and child prevents differentiating the contribution of each intervention to these results. Generalizing these findings to other populations with high neonatal mortality also is problematic because other factors may modify the effect of such an intervention. For example, in rural Nepal, the rates of sexually transmitted infections and bacterial vaginosis are low compared with many places in Africa,16,17 and the vast majority of deliveries occur at home, a highly contaminated environment. Therefore, colonization of the infant with potential pathogens from the mother during delivery may play a smaller role in South Asia than in Africa. The causative organisms for neonatal infections also suggest that environmental sources are common.18,19 Furthermore, the treatment effect could be modified by the birth weight distribution of the population, because skin barrier function is compromised in preterm, LBW infants, leading to increased risk for infection.20–22 Given the marked differences in LBW rates in Asia and Africa, it is important to understand the impact of the intervention in both contexts. On the basis of the potential for skin-cleansing of newborns with chlorhexidine to be a simple, inexpensive, and safe intervention for improving neonatal survival, we conducted a community-based trial of this intervention on neonatal mortality.

METHODS

The Nepal Newborn Washing Study was a cluster-randomized, placebo-controlled, community-based trial that began in September 2002 among newborn infants who were delivered to women who lived in Sarlahi District in south-central Nepal. This area is typical of much of the Indian subcontinent. The population is considered poor, even in Nepal; almost three fourths of families live below the poverty line.23 The area was divided into sectors (N = 413) on the basis of the population that 1 local female worker (ward distributor [WD]) could service, ∼40 to 50 households.

Pregnancies in the study area were identified by the WDs, who went door to door on a monthly basis. At ∼6 months' gestation, women were recruited for participation. At the time of recruitment, all women received weekly vitamin A supplementation, iron–folic acid supplements, and albendazole. These benefits were provided because previous research in this area had demonstrated their efficacy. Tetanus immunization history was assessed and, when deficient, provided by study staff, and all women were provided with a clean birthing kit. Workers provided education regarding proper nutrition during pregnancy and hygienic delivery and neonatal care, including clean cord care and prevention of hypothermia. Although the prevalence of HIV infection and group B streptococcal colonization in pregnant women is not known in this area, they are likely to be very low.

Eligibility and Randomization

Infants in this population typically are delivered by family members or untrained, traditional birth attendants, and >95% of births occur in the home. The WD was notified by families as soon as possible after the birth of a child. The WD then walked to the home to enroll the newborn infant and conducted the skin-cleansing.

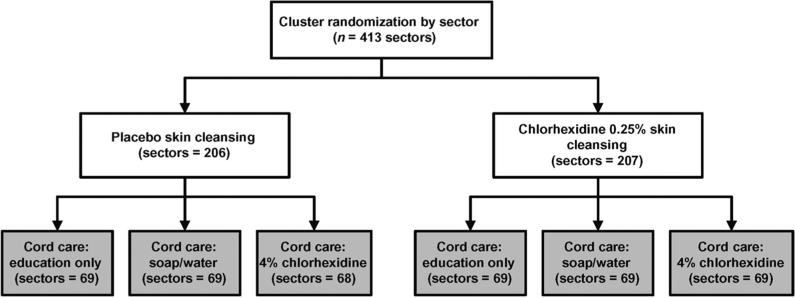

Randomization was conducted at the sector level, stratified by geographic area and tertiles of infant mortality risk as measured during an antenatal micronutrient supplementation trial that was completed in the same area 1 year before the start of this study.24 Concurrent with this trial, a subset of infants were included in a nested trial of 3 approaches to care of the umbilical cord using omphalitis and mortality as end points (Fig 1). Details of this trial were presented in a separate article.25

FIGURE 1.

Study design. Results of the nested trial of umbilical cord care treatments (gray boxes) are reported separately.25

Informed consent was obtained at the community, household, and individual levels. Community consent was obtained during meetings with community leaders. In addition, verbal consent was obtained at the household level from the parents of enrolled infants.

Intervention

Newborn infants were sector-randomized to receive 1 of 2 skin-cleansing regimens when the WD arrived at the house after delivery: (1) wiping of the total body excluding the eyes and ears with Pampers infant wipes (Procter and Gamble Co, Cincinnati, OH) that released a solution that contained 0.25% free chlorhexidine (equivalent to 0.44% chlorhexidine digluconate) or (2) wiping with the same infant wipes that lacked chlorhexidine (placebo). All wipes were alcohol-free, produced by Procter and Gamble Co, and packaged in sterile plastic sachets that contained 6 wipes. The allocation codes were kept at Proctor and Gamble, and investigators and all study staff were masked to the treatment assignment. Demonstrations with life-sized dolls and an instructional video were used to train WDs to deliver the intervention using a standard protocol.26

Definition and Measurement of Outcome

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality within the first 28 days of life. Cause of death was assessed by verbal autopsy and classified by an algorithmic approach defined previously.27 Sepsis deaths were defined by the presence of 2 or more of the following signs or symptoms: (1) caregiver's report of fever; (2) vomiting more than half of feeds; (3) unconsciousness; (4) bulging fontanelle; (5) feeding difficulty (not able to suck before death or feeding less than normal); (6) skin or umbilical cord infection (pus discharge from the cord stump); (7) jaundice; and (8) difficulty breathing and either rapid breathing or chest indrawing. A hierarchy of diagnoses was applied during cause-of-death analysis as follows: congenital abnormality, tetanus, prematurity, birth asphyxia, sepsis, acute lower respiratory infection, and diarrhea.27 For deaths that were attributed to congenital abnormality or tetanus, a confirmation by physician review of the verbal autopsy record was required.

Data Collection

Community-level data on the presence of economic, educational, and health facilities were collected during interviews with community leaders. Household-level data on socioeconomic status, education, maternal health indicators including reproductive history, and household structure were collected during a household interview. After the intervention visit to the home, a staff member (not the WD) visited to collect data on the delivery process and the condition and immediate care of the newborn infant and to weigh the infant using a digital infant scale. Visits were conducted on days 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 21, and 28 to assess infant vital status and morbidity. At each visit, the staff member examined the infant for signs of umbilical cord and skin infection, measured the axillary temperature and respiratory rate, and recorded other morbidity symptoms and signs. On day 14, an interview was conducted with the mother on newborn care practices. Infants who had specific sets of signs and symptoms at the time of household visits were referred to the local health system for care. All infants who were alive at 28 days were discharged from the study.

Sample Size

The study originally was designed to detect a minimum reduction in all-cause neonatal mortality of 20% (relative risk [RR]: 0.80) given 80% power, a 2-sided type I error of 5%, 5% loss to follow-up, and a neonatal mortality rate of 50 per 1000 live births in the placebo group. Because neonatal mortality did not cluster at the sector level during a previous study,24 no adjustment was made for intracluster correlation. This resulted in a sample size of 13 500 live births. A lower-than-expected neonatal mortality rate by the time of the first Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) meeting prompted the recommendation that the sample size be expanded to ∼17 000 live births.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 8.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Treatment groups were compared on baseline household, maternal, and delivery characteristics. Treatment effect on neonatal mortality was done on 2 populations. The first used all live births that occurred in the cluster irrespective of whether they received their assigned intervention. The second used only newborns who were alive at the time of the WD visit to the home and who received their assigned intervention. Mortality was compared using live births as the denominator and deaths within the first 28 days as the numerator. Survival analysis, including Kaplan-Meier survival curves, also was conducted. Multivariable binomial regression with a log link function was used to model the risk for mortality adjusted for potentially confounding factors imbalanced across treatment groups and to model effect modification. Estimates of the RRs and their SEs were adjusted to account for the clustered randomization using generalized estimating equations with an exchangeable correlation structure.28

Children who migrated out of the study area or whose parents refused additional participation before day 28 were censored at the time when they left the study. Stratified analyses were planned for selected variables that are known to be important risk factors for neonatal mortality, such as LBW, previous child death in the family, gender, and ethnic group.

Ethical Review and Data and Safety Monitoring

This study received approval from the Nepal Health Research Council and the Committee on Human Research of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. It is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00109616). An independent DSMB met 3 times to review the protocol and the data for safety and efficacy. At the meeting in January 2005, the DSMB recommended that the study be stopped because of adequate evidence for a beneficial effect of chlorhexidine newborn skin-cleansing among LBW infants. The ethical committees approved this decision, and from March 8, 2005, through January 2006 (end of enrollment), all newborn infants in the study area received skin-cleansing with the chlorhexidine solution.

Role of Funders

Financial supporters and the commodity supplier played no role in the design, conduct, management, analysis, or interpretation of the results or in the preparation, review, or approval of this article.

RESULTS

Study Population

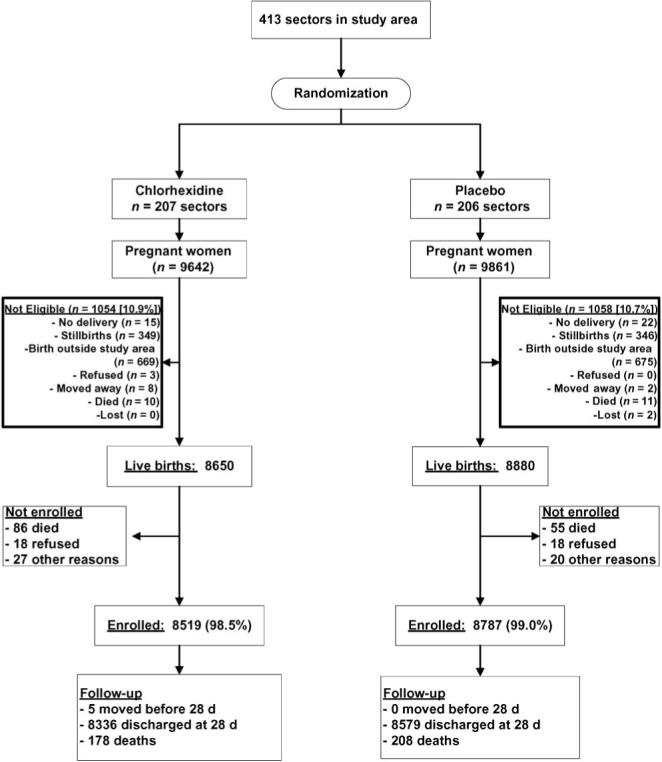

Between September 1, 2002, and March 8, 2005, there were 17 530 live-born infants from women who agreed to participate during their pregnancy (Fig 2). Parents of 18 (0.2%) infants in each group refused to participate when asked again at the time of infant enrollment. More infants did not receive their assigned intervention in the chlorhexidine group, 27 for other reasons and 86 because the infant died before the time the WD arrived to conduct the intervention (total = 113 [1.3%]) vs 20 for other reasons and 55 pretreatment deaths in the placebo group (total = 75 [0.8%]; Fig 2). The reason for this imbalance is unclear because the distribution of the time between birth and intervention was the same in the 2 treatment groups.

FIGURE 2.

Participation flow chart.

Baseline characteristics of the families, deliveries, and newborn infants who were enrolled in the trial were well balanced across treatment groups (Table 1). More than 90% of deliveries occurred at home. Approximately 60% of birth attendants washed hands with soap and water before the delivery; 80% of infants were fed colostrum, but only approximately half began breast-feeding within 12 hours after delivery. Birth weight distributions in the treatment groups were similar as were a number of other characteristics related to delivery hygiene and status of the infant at birth (Table 1). The LBW rate was 30%.

TABLE 1.

Selected Baseline Characteristics According to Treatment Group

| Baseline Variable | Chlorhexidine |

Placebo |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Total clusters | 207 | 100.0 | 206 | 100.0 | ||

| Cluster size of infants, mean (SD) | 41.2 (18.6) | 42.7 (19.6) | ||||

| Total live-born infants | 8650 | 100.0 | 8880 | 100.0 | ||

| Maternal age, y | ||||||

| <20 | 2151 | 24.9 | 2211 | 24.9 | ||

| 20−24 | 3503 | 40.5 | 3459 | 39.0 | ||

| 25−29 | 1860 | 21.5 | 2035 | 2.9 | ||

| 30−34 | 777 | 9.0 | 841 | 9.5 | ||

| ≥35 | 359 | 4.2 | 334 | 3.8 | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 4443 | 51.4 | 4533 | 51.1 | ||

| Female | 4207 | 48.6 | 4347 | 49.0 | ||

| Ethnic groupa | ||||||

| Pahadi | 2375 | 27.9 | 2596 | 29.8 | ||

| Madeshi | 6124 | 72.1 | 6109 | 70.2 | ||

| Casteb | ||||||

| Brahmin | 528 | 6.6 | 585 | 6.7 | ||

| Chetri | 581 | 6.8 | 562 | 6.5 | ||

| Vaiysha | 5379 | 63.2 | 5521 | 63.3 | ||

| Shudra | 1113 | 13.1 | 1267 | 14.5 | ||

| Muslim/other | 876 | 10.3 | 781 | 8.9 | ||

| Paternal literacyc | 4862 | 56.3 | 4920 | 55.5 | ||

| Maternal literacyd | 2198 | 25.4 | 2262 | 25.5 | ||

| Paternal occupatione | ||||||

| Farmer | 3732 | 43.2 | 3961 | 44.6 | ||

| Laborer | 2933 | 33.9 | 2874 | 32.4 | ||

| Business | 1063 | 12.3 | 1121 | 12.6 | ||

| Private service | 593 | 6.9 | 639 | 7.2 | ||

| Government | 228 | 2.6 | 195 | 2.2 | ||

| None | 88 | 1.0 | 75 | 0.8 | ||

| Previous child mortalityf | ||||||

| ≥1 previous child deaths | 1767 | 20.4 | 2019 | 22.6 | ||

| Electricity in houseg | 2039 | 24.0 | 2081 | 23.9 | ||

| Ownership | ||||||

| Bicycleh | 4603 | 53.2 | 4744 | 53.4 | ||

| Radioi | 2533 | 29.8 | 2593 | 29.8 | ||

| Televisionj | 1538 | 18.1 | 1517 | 17.4 | ||

| Paddy farm landk | 4201 | 49.8 | 4433 | 51.5 | ||

| Nonpaddy farm landl | 3673 | 43.5 | 3857 | 44.8 | ||

| Cattlem | 5122 | 60.3 | 5326 | 61.2 | ||

| Goatsn | 3872 | 46.7 | 4065 | 46.8 | ||

| House roof materialo | ||||||

| None | 40 | 0.5 | 36 | 0.4 | ||

| Thatch | 1315 | 15.5 | 1457 | 16.7 | ||

| Tile/tin | 6804 | 80.0 | 6878 | 78.9 | ||

| Concrete | 341 | 4.0 | 341 | 3.9 | ||

| Latrine at housep | 972 | 11.5 | 1019 | 11.6 | ||

| Water sourceq | ||||||

| Tube well | 7226 | 85.0 | 7376 | 84.8 | ||

| Ring well | 1236 | 14.5 | 1256 | 14.5 | ||

| Other | 42 | 0.5 | 80 | 0.7 | ||

| Place of deliveryr | ||||||

| Home | 7417 | 90.2 | 7620 | 90.2 | ||

| Outdoors | 33 | 0.4 | 40 | 0.4 | ||

| Health post/clinic | 270 | 3.3 | 282 | 3.3 | ||

| Hospital | 441 | 5.4 | 450 | 5.3 | ||

| Other | 63 | 0.8 | 56 | 0.7 | ||

| Birth weight, gs | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2704 (437) | 2706 (450) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2700 (2414−3000) | 2700 (2408−3000) | ||||

| <2000 | 400 | 4.3 | 433 | 5.1 | ||

| 2000−2499 | 2048 | 24.8 | 2058 | 24.2 | ||

| 2500−2999 | 3687 | 44.6 | 3809 | 44.8 | ||

| ≥3000 | 2128 | 25.8 | 2201 | 25.9 | ||

| Unclear amniotic fluid at deliveryt | 2201 | 28.7 | 2292 | 29.0 | ||

| Birth attendant washed hands before deliveryu | 4981 | 63.5 | 4804 | 59.8 | ||

| Used new blade to cut umbilical cordv | 7753 | 97.6 | 7987 | 98.0 | ||

| Breastfed within 12 h after deliveryw | 4009 | 47.8 | 4095 | 47.4 | ||

| Infant given colostrumx | 6735 | 80.1 | 7038 | 81.2 | ||

IQR indicates interquartile range.

A total of 326 were missing ethnicity data.

A total of 307 were missing caste data.

A total of 19 were missing paternal-literacy data.

A total of 11 were missing maternal-literacy data.

A total of 28 were missing paternal-occupation data.

None were missing previous child-death data.

A total of 329 were missing data on electricity in the house.

None were missing bicycle ownership data.

A total of 330 were missing radio-ownership data.

A total of 330 were missing television-ownership data.

A total of 472 were missing paddy-land data.

A total of 472 were missing nonpaddy-land data.

A total of 332 were missing cattle-ownership data.

A total of 370 were missing goat-ownership data.

A total of 318 were missing house roof material data.

A total of 348 were missing latrine data.

A total of 314 were missing water-source data.

A total of 858 were missing place-of-delivery data.

A total of 766 were missing birth weight data.

A total of 2055 were missing amniotic fluid data.

A total of 1653 were missing hand-washing data.

A total of 1432 were missing blade data.

A total of 493 were missing breastfeeding data.

A total of 449 were missing colostrum data.

Intervention Delivery

Because study staff typically were not in attendance at the delivery, WDs traveled to the house where the delivery took place. Despite this inherent delay, newborn skin-cleansing occurred soon after delivery at a median time of 5.8 hours after birth (interquartile range: 2.1− 11.8 hours); 91.4% of infants were cleansed within the first 24 hours. No adverse reactions to the intervention were reported.

Safety

A concern regarding this intervention was the potential for hypothermia as a result of the wetting action of the wipes, especially because the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that bathing after birth be delayed for at least 6 hours.29 Previous research in our study area showed that 95% of families conduct a wet wash of the newborn within the first 12 hours after delivery.30 This suggested that an additional skin-wiping followed promptly by wrapping of the infant and accompanied by behavioral messages to limit exposure and manage hypothermia would be unlikely to produce additional risk as a result of hypothermia. A pilot study of the wiping procedure confirmed that little moisture was left on the skin, little to no vernix was removed, and a small drop in body temperature (mean: 0.4°C) resulted.26 A previous trial of antenatal micronutrient supplementation on birth weight and early infant health that was conducted in the same study area used an identical method for measurement of infant temperature (P. Christian, DrPH, written communication, 2005). This allowed a comparison of rates of hypothermia between these studies. Adjusted for month of birth, there was a 12% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 5%−19%) increased odds of mild hypothermia (36.5°C–35.8°C) and a 16% (95% CI: 22%−10%) reduced odds of moderate to severe hypothermia (<35.9°C) in the skin-cleansing trial compared with the previous study.

Intervention Impact

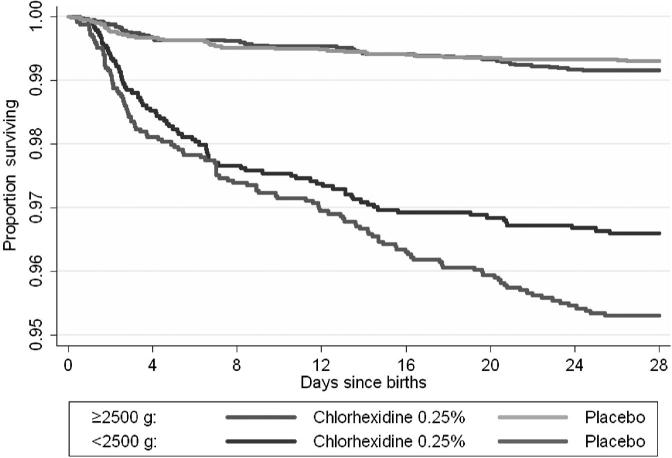

On the basis of the intention-to-treat analysis of all live births, there was no difference in neonatal mortality (RR: 1.04; 95% CI: 0.87−1.24; Table 2). Among those who actually received their assigned intervention, there was a nonsignificant 11% lower neonatal mortality rate in the chlorhexidine group compared with placebo (Table 2). However, among LBW infants, the chlorhexidine group had a significant, 28% lower mortality than the placebo group (RR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.55− 0.95). Infants who weighed ≥2500 g showed no significant difference in mortality (Table 2; Fig 3). Among LBW infants, baseline comparisons between the treatment groups also were well balanced (data not shown). Alternative definitions of LBW, such as <2000 g, showed similar treatment effects as for those <2500 g (data not shown). There was no evidence of interaction between the skin-cleansing intervention and the treatments in the umbilical cord care trial; both chlorhexidine treatments acted independently.25 There was no evidence that other factors modified the effect of skin-cleansing with chlorhexi-dine on mortality risk (Table 2). Among LBW infants, chlorhexidine skin-cleansing was equally effective when stratified by whether the birth attendant washed her hands before delivery (washed hands RR: 0.77 [95% CI: 0.51−1.18]; did not wash hands RR: 0.78 [95% CI: 0.53− 1.16]). Among LBW infants, there was a trend toward reduction in sepsis-specific deaths in the chlorhexidine group (RR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.53−1.29).

TABLE 2.

Mortality According to Treatment Group

| Parameter | Placebo Wash |

Chlorhexidine Wash |

RR | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live Births | Deaths | Rate | Live Births | Deaths | Rate | |||

| Total | 8880 | 263 | 29.6 | 8650 | 264 | 30.1 | 1.04 | 0.87−1.24 |

| Received assigned intervention | ||||||||

| No | 93 | 55 | 591.4 | 131 | 86 | 656.5 | 1.11 | 0.90−1.36 |

| Yes | 8787 | 208 | 23.7 | 8519 | 178 | 20.9 | 0.89 | 0.72−1.10 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 4533 | 133 | 29.3 | 4443 | 142 | 32.0 | 1.08 | 0.86−1.38 |

| Female | 4347 | 130 | 29.9 | 4207 | 122 | 29.0 | 0.98 | 0.76−1.28 |

| Ethnic groupa | ||||||||

| Pahadi | 2596 | 49 | 18.9 | 2375 | 55 | 23.2 | 1.24 | 0.83−1.86 |

| Madeshi | 6109 | 205 | 33.6 | 6124 | 203 | 33.1 | 0.99 | 0.81−1.21 |

| History of child death in familyb | ||||||||

| No | 6861 | 178 | 25.9 | 6883 | 202 | 29.3 | 1.14 | 0.92−1.41 |

| Yes | 2018 | 85 | 42.1 | 1763 | 62 | 35.2 | 0.84 | 0.59−1.19 |

| Birth attendant washed hands before deliveryc | ||||||||

| No | 3232 | 107 | 33.1 | 2860 | 98 | 34.3 | 1.04 | 0.78−1.37 |

| Yes | 4804 | 124 | 25.8 | 4981 | 135 | 27.1 | 1.06 | 0.82−1.36 |

| Birth weight, gd | ||||||||

| <2500 | 2491 | 117 | 47.0 | 2448 | 83 | 33.9 | 0.72 | 0.55−0.95 |

| ≥2500 | 6010 | 42 | 7.0 | 5815 | 49 | 8.4 | 1.20 | 0.80−1.81 |

Rate shown is per 1000 live births.

A total of 326 were missing ethnicity data.

A total of 5 were missing previous child-death data.

A total of 1653 were missing hand-washing data.

A total of 766 were missing birth weight data.

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves according to treatment group among LBW (<2500 g) and normal birth weight (≥2500 g) infants. Log rank test: ≥2500 g χ2 = 0.79, P = 0.37; <2500 g χ2 = 5.26, P = .02.

Once the DSMB recommended that the randomized-trial portion of the study be stopped, all subsequent live births (n = 6055) were eligible to receive the active treatment. After conversion of the placebo clusters to chlorhexidine, there was a statistically nonsignificant 6% reduction in overall mortality as compared with no change in the chlorhexidine clusters (Table 3). Among LBW infants, there was a 37% reduction in mortality among infants in the placebo clusters, whereas no change was found from before conversion to after conversion in the chlorhexidine clusters.

TABLE 3.

Mortality According to Treatment Group During Randomized-Trial Phase and After Switch-over of Placebo Clusters to Chlorhexidine Skin-Cleansing

| Parameter | Placebo Wash |

Chlorhexidine Wash |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live Births | Deaths | Rate (per 1000 Enrolled Live Births) | Live Births | Deaths | Rate (per 1000 Enrolled Live Births) | |

| Total | ||||||

| Randomized-trial period, n | 8880 | 263 | 29.6 | 8650 | 264 | 30.1 |

| Placebo converted to chlorhexidine, n | 3136 | 87 | 27.7 | 2919 | 94 | 32.2 |

| RR after conversion vs before conversion | 0.94 | 1.04 | ||||

| 95% Cl | 0.74−1.19 | 0.83−1.31 | ||||

| Birth weighta<2500 g | ||||||

| Randomized-trial period, n | 2491 | 117 | 47.0 | 2448 | 83 | 33.9 |

| Placebo converted to chlorhexidine, n | 952 | 28 | 29.4 | 877 | 32 | 36.5 |

| RR after conversion vs before conversion | 0.63 | 1.08 | ||||

| 95% Cl | 0.42−0.94 | 0.72−1.61 | ||||

| Birth weight ≥2500 ga | ||||||

| Randomized-trial period, n | 6010 | 42 | 7.0 | 5815 | 49 | 8.4 |

| Placebo converted to chlorhexidine, n | 2114 | 12 | 5.7 | 1978 | 14 | 7.1 |

| RR after conversion vs before conversion | 0.81 | 0.84 | ||||

| 95% Cl | 0.43−1.54 | 0.47−1.52 | ||||

Birth weight data were missing for 134 infants during the postconversion data-collection period.

DISCUSSION

Overall, there was no evidence that chlorhexidine cleansing of the skin was associated with reduced neonatal mortality in this population. However, among LBW infants who actually received their assigned intervention, there was a 28% reduction in neonatal mortality among those whose skin was wiped with chlorhexi-dine as soon as possible after birth. The causal evidence for the LBW results were strengthened by the observation of a significant decline in mortality among LBW infants after the randomized portion of the study among sectors that originally were assigned to the placebo group, whereas mortality in the clusters that originally were assigned to chlorhexidine did not change. These data suggest that, in a high-risk subgroup of infants, early postdelivery skin-cleansing with chlorhexidine may reduce the risk for neonatal mortality. This finding needs confirmation, however, from other studies of LBW infants in settings where home deliveries are common. These data lend partial support to 2 previous, nonrandomized, hospital-based studies in Malawi and Egypt, where significant reductions in early neonatal mortality were found among infants who were washed with 0.25% chlorhexidine and whose mothers received vaginal cleansing with the same solution.14,15 Whether the combined use of vaginal and newborn skin-cleansing would have produced greater benefit or spread the benefit across all infants in our study population is unknown. More than 90% of births in Nepal occurred at home, where there is a much higher potential for environmental contamination of the newborn infant than in hospital settings.

As expected for an intervention that focuses on reducing the risk for infection, fewer deaths among LBW infants as a result of sepsis were observed in cause-specific analysis. However, results of verbal autopsies for very young infants must be viewed with caution because many of the signs and symptoms that were used in the algorithms for cause of death can apply to a variety of causes. A reduction in sepsis deaths also was observed in the Malawi study, in which there was a two-thirds reduction in clinically diagnosed early neonatal sepsis deaths.14

The results from these studies suggest that the importance of a well-developed and healthy skin barrier to infection may have been underestimated to date, especially in settings where environmental contamination and the prevalence of LBW are high. This idea is supported by recent results from trials of therapy with topically applied emollients (eg, sunflower oil), which showed 54% and 41% reductions in nosocomial sepsis among preterm infants in Egypt21 and Bangladesh,22 respectively. Moreover, invasion through the skin of pathogens in neonatal sepsis among very LBW infants in developed countries has been documented.31–33 Evidence suggests that chlorhexidine-mediated reductions in numbers of colonizing pathogens, alternations in the local balance of microbes, and/or in skin barrier immune function may act to reduce risk for development of systemic infections via cutaneous and/or umbilical portals of entry.34–37

Chlorhexidine was chosen for this study because of its established safety profile at concentrations well above those used in this trial and because it leaves a residual bactericidal effect on the skin.38 It is included on the WHO essential drug list, and the WHO recommends it when antiseptic applications to the umbilical cord are indicated.39 We found no adverse effects as a result of its use as a skin-cleansing agent.

This study does have limitations. Specifically, there was imbalance in the number of deaths that occurred between birth and the time when our local worker arrived at the house to enroll the infant officially and provide the assigned skin-cleansing. We have no explanation for this difference in preenrollment mortality because the distribution of time between birth and the application of the assigned treatment was identical in the 2 treatment groups. Treatment groups also were well balanced on a variety of other factors that are associated with early infant mortality.

The results from this trial in rural Nepal and the hospital-based studies in Africa suggest that a simple, safe, and inexpensive newborn chlorhexidine skin-cleansing may reduce significantly neonatal mortality among infants in these low-resource settings. However, the limitation of a positive treatment effect to a subgroup of this study population requires that additional data that directly address the role of chlorhexidine skin-cleansing among LBW infants be collected in populations with high risk for neonatal mortality before this intervention can move from research to programs and policy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was conducted by the Department of International Health, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD), under grants HD 44004 and HD 38753 from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD); grant 810 −2054 from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Seattle, WA); and Cooperative Agreements HRN-A-00−97−00015−00 and GHS-A-00−03−000019−00 between Johns Hopkins University and the Office of Health and Nutrition, US Agency for International Development (Washington, DC). Commodity support was provided by Procter and Gamble Co (Cincinnati, OH).

Special appreciation goes to Data and Safety Monitoring Board members Drs P. S. S. Sundar Rao, Pushpa Sharma, Dharma Manandhar, and Martin Bloem.

Abbreviations

- LBW

low birth weight

- WD

ward distributor

- RR

relative risk

- DSMB

Data and Safety Monitoring Board

- WHO

World Health Organization

- CI

confidence interval

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr Darmstadt has collaborated with Proctor and Gamble on testing of skin emollient products for premature newborns. The other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

A preliminary set of these data was presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies; May 16, 2005; Washington DC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lawn JE, Cousens S, Darmstadt GL, Paul V, Martines J. Why are 4 million newborn babies dying every year? Lancet. 2004;364:2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17511-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Save the Children Federation . Saving Newborn Lives, State of the World's Newborns. Save the Children Federation; Westport, CT: 2001. pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. 4 million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005;365:891–900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costello A, Manandhar D. Current state of the health of newborn infants in developing countries. In: Costello A, Manandhar D, editors. Improving Newborn Infant Health in Developing Countries. Imperial College Press; London, England: 2000. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahmathullah L, Tielsch JM, Thulasiraj RD, et al. Impact of newborn vitamin A dosing on early infant mortality: a community-based randomized trial in south India. Br Med J. 2003;327:254. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7409.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, Adam T, Walker N, de Bernis L. Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet. 2005;365:977–988. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adriaanse AH, Kollee LAA, Muytjens HL, Nijhuis JG, de Haan AF, Eskes TK. Randomized study of vaginal chlorhexidine disinfection during labor to prevent vertical transmission of group B streptococci. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1995;61:135–141. doi: 10.1016/0301-2115(95)02134-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burman LG, Christensen P, Christensen K, et al. Prevention of excess neonatal morbidity associated with group B streptococci by vaginal chlorhexidine disinfection during labour. Lancet. 1992;340:65–69. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90393-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen KK, Christensen P. Chlorhexidine for prevention of neonatal colonization with GBS. Antibiot Chemother. 1985;35:296–302. doi: 10.1159/000410383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dykes AK, Christensen KK, Christensen P. Chlorhexidine prevention of neonatal colonization with GBS: IV. Depressed puerperal carriage following vaginal washing with chlorhexidine during labor. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1987;24:293–297. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(87)90154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meberg A, Schoyen R. Bacterial colonization and neonatal infections. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1985;74:366–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1985.tb10985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rouse DJ, Hauth JC, Andrews WW, Mills BB, Maher JE. Chlorhexidine vaginal irrigation for the prevention of peripartal infection: a placebo controlled randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:617–622. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70557-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sweeten KM, Eriksen NL, Blanco JD. Chlorhexidine versus sterile water vaginal wash during labor to prevent peripartum infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:426–430. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taha TE, Biggar RJ, Broadhead RL, et al. Effect of cleaning the birth canal with antiseptic solution on maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality in Malawi. Br Med J. 1997;315:216–220. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7102.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakr AF, Karkour T. Effect of predelivery vaginal antisepsis on maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in Egypt. J Womens Health. 2005;14:496–501. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wawer MJ, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, et al. Control of sexually transmitted diseases for AIDS prevention in Uganda: a randomised community trial. Lancet. 1999;353:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)06439-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christian P, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Chlamydia and gonorrhea among rural Nepali women. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:254–258. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.011817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sidbury R, Darmstadt GL. Microbiology. In: Hoath SB, Maibach H, editors. Neonatal Skin. 2nd ed. Marcel Dekker; New York, NY: 2002. pp. 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaidi AKM, Ali SA, Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA. Serious Bacterial Infections Among Neonates and Young Infants in Developing Countries: Evaluation of Etiology and Therapeutic Management Strategies in Community Settings. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2003. pp. 1–106. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darmstadt GL, Mao-Qiang M, Chi E, et al. Impact of topical oils on the skin barrier: possible implications for neonatal health in developing countries. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91:546–554. doi: 10.1080/080352502753711678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darmstadt GL, Badrawi N, Law PA, et al. Topical therapy with sunflower seed oil prevents nosocomial infections and mortality in premature babies in Egypt: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:719–725. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000133047.50836.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darmstadt GL, Saha SK, Ahmed ASMNU, et al. Effect of topical treatment with skin barrier-enhancing emollients on nosocomial infections in preterm infants in Bangladesh: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1039–1045. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pradhan EK, LeClerq SC, Khatry SK, et al. A Window to Child Health in the Terai. Nepal Nutrition Intervention Project-Sarlahi; Kathmandu, Nepal: 1999. NNIPS Monograph No. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christian P, West KP, Khatry SK, et al. Effects of maternal micronutrient supplementation on fetal loss and infant mortality: a cluster-randomized trial in Nepal. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:1194–1202. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.6.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mullany LC, Darmstadt GL, Khatry SK, et al. Topical applications of chlorhexidine to the umbilical cord prevent omphalitis and reduce neonatal mortality in southern Nepal: a community-based, cluster-randomized trial. Lancet. 2006;367:910–918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68381-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mullany LC, Darmstadt GL, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, Tielsch JM. Safety of neonatal skin cleansing in rural Nepal. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43:117–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman JV, Christian P, Khatry SK, et al. Evaluation of neonatal verbal autopsy using physician review versus algorithm-based cause-of-death assignment in rural Nepal. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2005;19:323–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization . Thermal Protection in the Newborn: A Guide. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1997. Report WHO/RHT/MSM/97.2. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mullany LC, Darmstadt GL, Khatry SK, Tielsch JM. Traditional massage of newborns in Nepal: implications for trials of improved practice. J Trop Pediatr. 2005;51:82–86. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmh083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darmstadt G, Saha S, Ahmed A, Khatun M, Chowdhury M. The skin as a potential portal of entry for invasive infections in neonates. Perinatology. 2003;5:205–212. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams M. Skin of the premature infant. In: Eichenfield L, Frieden I, Esterly N, editors. Textbook of Neonatal Dermatology. WB Saunders Co; Philadelphia, PA: 2001. pp. 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- 33.D'Angio C, McGowan K, Baumgart S, St Geme J, Harris M. Surface colonization with coagulase-negative staphylococci in premature neonates. J Pediatr. 1989;114:1029–1034. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Darmstadt G, Fleckman P, Jonas M, Chi E, Rubens C. Differentiation of cultured keratinocytes promotes adherence of Streptococcus pyogenes. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:128–136. doi: 10.1172/JCI680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dinulos JG, Mentele L, Fredericks LP, Dale BA, Darmstadt GL. Keratinocyte expression of human beta-defensin-2 following bacterial infection: role in cutaneous host defense. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10:161–166. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.1.161-166.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mullany L, Darmstadt GL, Tielsch J. Role of antimicrobial applications to the umbilical cord on bacterial colonization and infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:996–1002. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000095429.97172.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowbury EJ, Lilly HA. Use of 4 percent chlorhexidine detergent solution (Hibiscrub) and other methods of skin disinfection. Br Med J. 1973;1(5852):510–515. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5852.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denton GW. Chlorhexidine. In: Block SS, editor. Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation. 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2001. pp. 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization . Care of the Umbilical Cord. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1998. Report WHO/FHE/MSM-cord care. [Google Scholar]