Abstract

Background

Aspiration pneumonia is common among frail elderly persons with dysphagia. Although interventions to prevent aspiration in these patients are routinely used in these patients, little is known about the effectiveness of those interventions.

Objective

To compare the effectiveness of chin-down posture and 2 consistencies (nectar or honey) of thickened liquids on the 3-month cumulative incidence of pneumonia in participants with dementia or Parkinson disease.

Design

Randomized, controlled, parallel-design trial in which patients were enrolled from 9 June 1998 to 19 September 2005.

Setting

47 hospitals and 79 subacute facilities.

Patients

515 patients age 50 years or older with dementia or Parkinson disease who aspirated thin liquids (demonstrated videofluoroscopically). Of these, 504 were followed until death or 3 months.

Interventions

Participants were randomly assigned to drink all liquids in a chin-down posture (n = 259) or to drink nectar-thick (n = 133) or honey-thick (n = 123) liquids in a head-neutral position.

Measurements

The primary outcome was pneumonia diagnosed by chest radiography or by the presence of 3 respiratory indicators.

Results

52 participants had pneumonia, yielding an overall estimated 3-month cumulative incidence of 11%. The 3-month cumulative incidence of pneumonia was 0.098 and 0.116 in the chin-down posture and thickened-liquid groups, respectively (hazard ratio [HR], 0.84 [95% CI, 0.49 to 1.45]; P = 0.53). The 3-month cumulative incidence of pneumonia was 0.084 in the nectar-thick liquid group compared with 0.150 in the honey-thick liquid group (HR, 0.50 [CI, 0.23 to 1.09]; P = 0.083). More patients assigned to thickened liquids than those assigned to the chin-down posture intervention had dehydration (6% vs. 2%), urinary tract infection (6% vs. 3%), and fever (4% vs. 2%).

Limitations

A no-treatment control group was not included. Follow-up was limited to 3 months. Care providers were not blinded, and differences in cumulative pneumonia incidence between interventions had wide CIs.

Conclusion

No definitive conclusions about the superiority of any of the tested interventions can be made. The 3-month cumulative incidence of pneumonia was much lower than expected in this frail elderly population. Future investigation of chin-down posture combined with nectar-thick liquid may be warranted to determine whether this combination better prevents pneumonia than either intervention independently.

Trial Registration

Clinical Trials.gov registration number: NCT00000362

Swallowing disorders are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. An estimated 18 million adults will require care for dysphagia-related malnutrition, dehydration, pneumonia, and reductions in quality of life by 2010 (1-3). Patients with dysphasia have an increased incidence of aspiration pneumonia because the aspirated material is heavily colonized with bacteria. Pneumonia is the most common cause of infectious death in the United States among persons age 65 years or older and the third leading cause of death for persons age 85 years or older (4). One hospital admission for pneumonia is estimated to cost $7166 (5). Rates of hospital discharge for Medicare beneficiaries with pneumonia as a primary diagnosis have increased by 93.5% in the past decade (6), along with length of stay and death rates (4).

Liquid aspiration is the most common type of aspiration in elderly persons (1). Relative risk for pneumonia is highest in patients with dementia, followed by those who are institutionalized (7). As many as 50% of patients with parkinsonism are estimated to have dysphagia (8), and one third aspirate silently---that is, with no external sign (such as coughing) to eject material or alert caregivers (9).

Many short- and long-term care facilities use thickened liquid diets to treat of aspiration (10). In these diets, thin liquids (for example, water, tea, coffee) are eliminated, even in the absence of efficacy data, at a substantial cost in financial and quality-of-life terms. It costs approximately $200 per month for an individual to drink thickened liquids (11,12). A common alternative to thickened liquids is use of a chin-down posture (13-17). Welch and coworkers (13) noted that posterior shift of anterior pharyngeal structures with the chin-down posture improved airway protection. Whereas previous studies have provided a basis for the widespread clinical use of chin-down posture, none has provided long-term health outcome data.

Results from a previously reported portion of this study demonstrated short-term elimination of aspiration during the videofluorographic swallowing evaluation most often with honey-thick liquids, followed by nectar-thick liquids, and finally chin-down position (18). We sought to compare the effectiveness of chin-down posture and thickened liquids (nectar thick and honey thick) on the incidence of pneumonia in participants with dementia or Parkinson disease during 3 months of treatment.

Methods

Design

The study design and methods are described in detail elsewhere (19). In brief, between enrollment initiation on 9 June 1998 and closure on 16 September 2005, 47 acute-care hospitals and 79 subacute residential facilities combined their patients to enroll 515 participants, a total that was 65 participants short of the recruitment goal. Follow-up was completed on 9 December 2005. The Data and Safety Monitoring Committee recommended discontinuing enrollment, on the basis of a futility analysis suggesting that enrolling additional participants would not change the findings.

Participants were enrolled in this 3-month follow-up study if they were observed to aspirate when swallowing 3 mL of thin liquids from a spoon or when drinking from a cup without an intervention during videofluoroscopy or swallowing. Aspiration was defined as barium observed below the vocal folds. Participants who qualified were then given boluses to perform 3 conditions in random order: thin liquid (15 centipoise) swallowed in a chin-down posture, nectar-thick liquid (300 centipoise) swallowed in a head-neutral position, and honey-thick liquid (3000 centipoise) swallowed in a head-neutral position. Participants who did equally well (all conditions eliminated aspiration) or equally poor (no conditions eliminated aspiration) but wished to continue oral intake, despite being warned about risk for pneumonia, were randomly assigned to 1 of the conditions as an intervention and followed for 3 months. Participants who aspirated during 1 or 2 of the conditions were not randomly assigned. On-site speech-language pathologists, nurses, and direct care and dietary staff who completed rigorous training about facilitation of the chin-down posture and proper techniques to thicken liquids supervised administration of the interventions. The number of participants under supervision by a speech-language pathologist ranged from 1 to 93 (median, 4 participants). Clinicians were instructed to refrain from using concomitant active or compensatory interventions with participants during the study period. Research staff made monthly site visits to monitor protocol adherence. All participants or their representatives provided written informed consent. Each facility’s institutional review board of record, as approved by the Office for Human Research Protections, Department of Health and Human Services, approved the study.

Setting and Participants

Inclusion criteria were a physician-identified diagnosis of dementia (Alzheimer type, single or multistroke type, or other nonresolving types) or Parkinson disease and patient age (50 to 95 years). Exclusion criteria were tobacco use in the past year, current alcohol abuse, history of head or neck cancer, insulin-dependent diabetes for 20 years or more, nasogastric tube, other progressive or infectious neurologic diseases, or pneumonia within 6 weeks of enrollment.

Outpatients and inpatients from participating acute and subacute care facilities who were suspected of aspirating liquids by their physicians and speech-language pathologists during standard clinical care were referred for a videofluoroscopic swallowing study at a participating acute-care facility. The informed consent process was completed with the patient and care provider by the speech-language pathologist or research personnel before the swallowing study. After the swallowing study, participants returned to their living situation (acute care, subacute care, or home) while the videofluoroscopic images were analyzed. Participants were randomly assigned to an intervention group within 24 hours.

Randomization and Interventions

The primary interventions were chin-down posture while consuming thin liquids versus consuming thickened liquids (nectar thick or honey thick [Resource ThickenUp, Nestlé HealthCare Nutrition [formerly Novartis Medical Nutrition], Minneapolis, Minnesota]) in a head-neutral position. The thin, nectar-thick, and honey-thick barium solutions (Varibar, E-Z-EM, Lake Success, New York) were manufactured in a standardized formulation for this study. Standardized recipes matching the viscosities of the barium products were developed for a wide variety of thickened beverages.

Participants were randomly assigned centrally by a telephone system controlled by the Statistical and Data Center at the EMMES Corporation (Rockville, Maryland). A study speech-language pathologist called a central telephone number and entered participant criteria when prompted to by using the telephone keys. If the patient was eligible, an intervention was assigned and a summary page that included intervention assignment and meal-monitoring was faxed to the speech-language pathologist. Randomization sequences for primary assignment (chin-down posture vs. thickened liquids) were developed by a statistician at the Statistical and Data Center. The sequences were stratified by participant age (50 to 79 years or 80 to 95 years) and diagnosis (Parkinson disease with or without dementia, or dementia only) and included randomly assigned block sizes of 32, 40, or 48 within each of the 4 strata. If a participant was assigned to thickened liquids, a second randomization was done to assign the participant to nectar-thick liquids or honey-thick liquids with equal probability. Neither the participants nor direct caregivers were blinded to intervention assignment, but neither group made outcome judgments. We expected that all liquids, regardless of amount or frequency of administration, would be provided to participants consistent with the intervention to which the participant was randomly assigned. All participants continued nonliquid nutritional intake in the same manner as before enrollment. Eight percent received nutrition by means of a gastrostomy tube.

Measurements and Outcomes

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome for the study was definite pneumonia. Definite pneumonia was defined as evidence of pneumonia on chest radiography or 3 or more of the following: sustained fever (temperature >100 °F [38 °C]), rales or rhonchi on chest auscultation, sputum Gram stain showing substantial leukocytes, or sputum culture showing a respiratory pathogen.

Suspected pneumonia was defined as at least 2 of the 4 features of definite pneumonia (except evidence of pneumonia on a chest radiograph). The primary care physician determined the need for chest radiography or sputum culture as part of standard clinical care. Chest radiography was done in all 52 patients with pneumonia; 2 of these patients did not have evidence of pneumonia on chest radiography, but had 3 or 4 of the features of definite pneumonia.

Secondary Outcomes and Comparisons

A secondary outcome of interest was definite pneumonia or death. Secondary comparisons of interest were relative effectiveness of the 2 degrees of thickening (honey thick vs. nectar thick) and the effect of aspiration status at study entry (having aspirated all intervention liquids or none of the intervention liquids during the swallowing study). A future manuscript will address other secondary outcomes and comparisons.

Follow-up Procedures

Initially, all participants were monitored at all meals by caregivers and study staff for adherence with the assigned intervention (“meal-monitoring”). In 1999, to lessen the burden on care providers, meal-monitoring was reduced to randomized sets of 3 meals per week. Ultimately, a goal of meal-monitoring for 300 participants, distributed evenly across the 3 interventions, was selected, which provided CI widths of about 10 percentage points when compliance of 50% was assumed. Because the study was terminated early, 268 participants (96 in the chin-down posture group, 90 in the nectar-thick liquid group, and 82 in the honey-thick liquid group) were monitored for compliance with the assigned intervention. Participant characteristics did not vary by more than 4 percentage points between the meal-monitored group and the group that was not meal-monitored.

Exit forms were completed for participants at the end of the study or if participants discontinued the intervention before the end of 3-month follow-up. Regardless of when participants exited the intervention, their health outcomes were followed for 3 months. However, if participants had pneumonia, their use of the intervention stopped and they were referred to their speech-language pathologist for dysphagia management. Postintervention therapies were recorded starting in 2001, although whether the therapy was administered in a manner consistent with the study specifications was not specifically documented.

Clinicians assessed adverse events, which were defined as any clinically significant event possibly related to the assigned intervention (for example, dehydration). Clinicians were instructed not to report events expected as part of the participant’s disease progression or aging process (for example, worsening of Parkinson disease symptoms). Clinicians rated all adverse events as mild, moderate, severe, or life-threatening.

The Data and Safety Monitoring Committee met 16 times, either by phone or face-to-face. The composition of the committee represented various disciplines included in the project. The committee discussed progress in patient accrual, study outcomes, and participant safety. Quality site monitoring was conducted by the statistical and data center through extensive data editing, queries, and site visits to selected facilities. Any problems identified by these quality-control staff members were discussed with study personnel and corrected.

Statistical Analysis

Available literature at the time of study design suggested a 20% rate of cumulative pneumonia incidence in the study population at 3 months (20-22). A sample size of 290 participants was needed in each group (580 total) to provide a minimum of 90% power to detect a decrease in cumulative pneumonia incidence of 10 percentage points in the chin-down posture group if the cumulative pneumonia incidence in the thickened-liquids group was 20% (a 50% reduction in pneumonia incidence). A monitoring plan defined before study initiation provided control of α spending during interim safety analyses throughout the course of the study (23). The study conducted interim analyses for 8 Data and Safety Monitoring Committee meetings scheduled from July 2000 to August 2005. Each interim analysis evaluated a z statistic comparing rates of pneumonia or death between primary interventions by using an O’Brien-Fleming lower bound (24) with an α value of 0.025 and a Pocock (25) upper bound with an α value of 0.025. Neither the upper nor the lower boundary was crossed in an interim analysis. In addition, an unplanned conditional power calculation (26) was conducted at each interim analysis to determine the likelihood of rejecting the null hypothesis at upcoming interim analyses, given the study assumptions of a pneumonia or death rate of 0.10 with chin-down posture versus a pneumonia or death rate of 0.20 with thickened liquids. At the first interim analysis, the conditional power was greater than 0.5. By the final interim analysis, the conditional power was less than 0.001, which provided clear evidence to terminate recruitment before reaching the enrollment goal. Cumulative incidence rates for the outcomes of pneumonia and pneumonia or death overall were calculated by using the Kaplan-Meier life table method. A Cox model approach was used to assess primary intervention effect (chin-down posture vs. thickened liquids) and secondary intervention effect (nectar thick vs. honey thick liquids) after controlling for the 2 enrollment strata: age and diagnosis. Fisher exact tests (27) were used to compare adverse event rates. All tests of hypotheses were 2-sided. P values are presented without adjustment for testing of multiple end points. Missing data were limited to outcomes for participants lost to follow-up without a known death or pneumonia event during 12 weeks of follow-up. For these participants, follow-up time was censored at the time of study discontinuation. All randomly assigned participants were included in the analyses to the extent that information was available according to the intention-to-treat principle. All statistical analyses were done by using SAS software, version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Role of the Funding Source

The National Institutes of Health, through the Committee and Project Officer, had a role in the design and conduct of the study, interpretation of the data, and review or approval of the manuscript; however, they did not have a role in the collection, management, and analysis of data or preparation of the manuscript.

Results

Study Flow

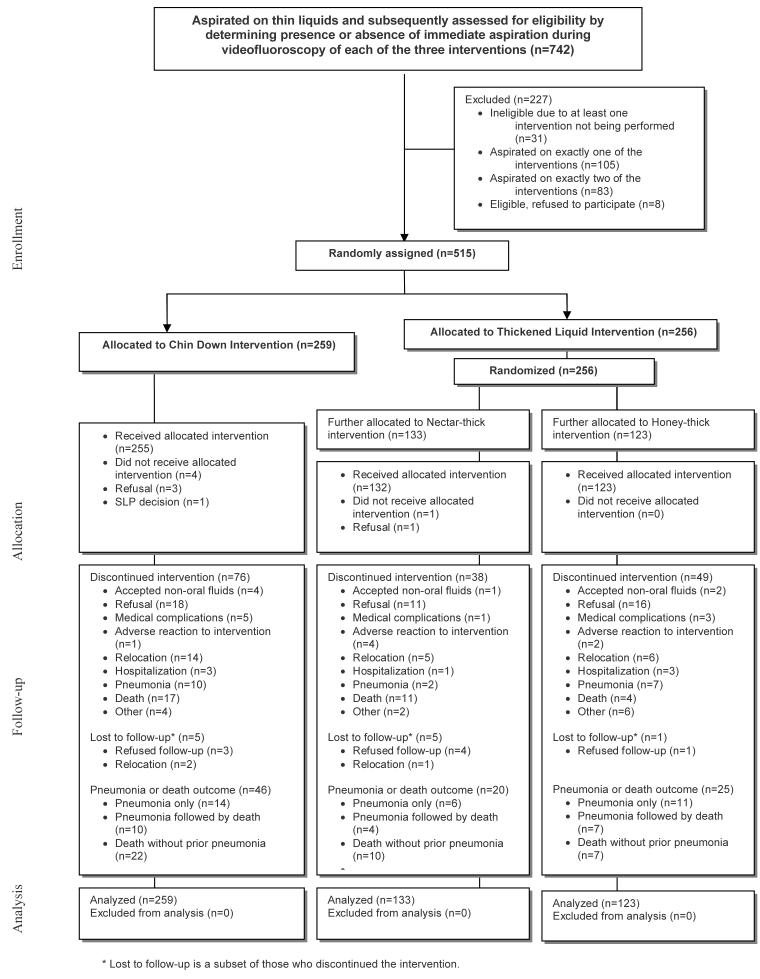

Figure 1 describes the study population. Seven hundred forty-two persons participated in the short-term swallowing study (18), of whom 515 were eligible and randomly assigned in our follow-up study. Two hundred fifty-nine participants were assigned to the chin-down posture group, and 256 participants were assigned to thickened-liquids group. Of the 515 randomly assigned participants, 413 completed 3 months of follow-up with no incidence of pneumonia, 39 without previous incidence of pneumonia were followed until death, 52 developed pneumonia (of whom 21 subsequently died), and 11 without previous incidence of pneumonia had incomplete follow-up (ranging from <1 week to 2 months).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 shows participant characteristics by intervention group. Seventy percent were men, 59% were age 80 years or older (median age, 81), and 16% were of minority ethnicity. Fifty percent had dementia, 30% had Parkinson disease without dementia, and 20% had Parkinson disease with dementia. About two thirds of participants qualified for enrollment in the study by aspirating with all interventions in the swallowing study.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Enrollment*

| Interventions | Thickened Liquids | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chin Down | Thickened Liquids | Nectar-Thick | Honey-Thick | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| N | 259 | 100 | 256 | 100 | 133 | 100 | 123 | 100 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 178 | 69 | 181 | 71 | 93 | 70 | 88 | 72 |

| Female | 81 | 31 | 75 | 29 | 40 | 30 | 35 | 28 |

| Age | ||||||||

| 50-59† | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 60-69 | 16 | 6 | 21 | 8 | 16 | 12 | 5 | 4 |

| 70-79 | 88 | 34 | 78 | 30 | 37 | 28 | 41 | 33 |

| 80-89 | 127 | 49 | 125 | 49 | 66 | 50 | 59 | 48 |

| 90-95 | 26 | 10 | 28 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 16 | 13 |

| Age: Mean (median) | 81 (81) | 80 (81) | 80 (81) | 81 (81) | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 217 | 84 | 214 | 84 | 111 | 84 | 103 | 84 |

| Black | 22 | 8 | 18 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 11 | 9 |

| Hispanic | 10 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 9 | 3 | 16 | 6 | 12 | 9 | 4 | 3 |

| Other | 1 | <1 | 1 | <1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Educational level | ||||||||

| No formal education | 1 | <1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Some grammar school | 51 | 20 | 36 | 14 | 18 | 14 | 18 | 15 |

| Some high school | 42 | 16 | 42 | 16 | 26 | 20 | 16 | 13 |

| High school graduate | 76 | 29 | 80 | 31 | 37 | 28 | 43 | 35 |

| 1+ years of college | 55 | 21 | 66 | 26 | 36 | 27 | 30 | 24 |

| 1+ years of graduate school | 20 | 8 | 24 | 9 | 13 | 10 | 11 | 9 |

| Not reported | 14 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

| Dementia - Alzheimer’s | 42 | 16 | 46 | 18 | 20 | 15 | 26 | 21 |

| Dementia - Single or multi stroke | 40 | 15 | 35 | 14 | 17 | 13 | 18 | 15 |

| Dementia - Other | 49 | 19 | 48 | 19 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 15 |

| Idiopathic PD† - No Dementia | 83 | 32 | 71 | 28 | 39 | 29 | 32 | 26 |

| Idiopathic PD† - Dementia | 45 | 17 | 56 | 22 | 28 | 21 | 28 | 23 |

| Aspiration during Immediate (short-term) study | ||||||||

| None of the interventions | 76 | 30 | 94 | 37 | 46 | 35 | 48 | 39 |

| All of the interventions | 183 | 70 | 162 | 63 | 87 | 65 | 75 | 61 |

PD: Parkinson’s disease

Includes one participant enrolled 2 weeks short of turning 50 years o

Cumulative Incidence Rates within Intervention and Participant Subgroups

Pneumonia Outcome

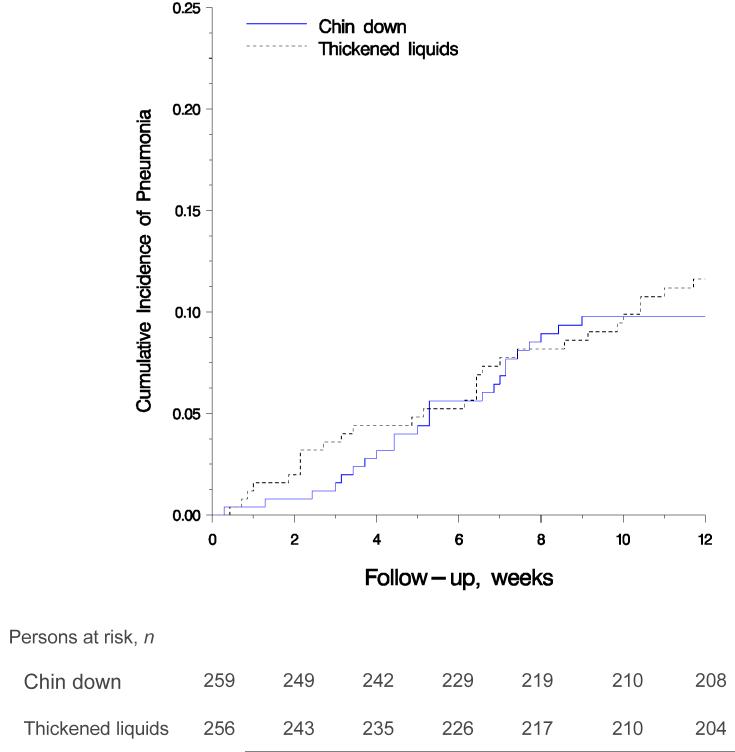

Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier estimate (28) of pneumonia by main intervention group. The 3-month Kaplan-Meier estimates of pneumonia in the chin-down posture and thickened-liquid groups were 0.098 (24 events) and 0.116 (28 events), respectively (hazard ratio [HR], 0.84 [95% CI, 0.49 to 1.45]; P = 0.53). When participants were stratified by short-term aspiration status, the 3-month Kaplan-Meier estimates of pneumonia in the chin-down posture and thickened-liquid groups were 0.082 (6 events) and 0.0436 (4 events), respectively (HR, 1.91 [CI, 0.54 to 6.78]; P = 0.32) for participants who aspirated during none of the interventions and 0.105 (18 events) and 0.161 (24 events), respectively (HR, 0.64 [CI, 0.35 to 1.18]; P = 0.153), for participants who aspirated during all 3 interventions.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of pneumonia in the chin down posture and thickened liquid groups (P = 0.53, log-rank test).

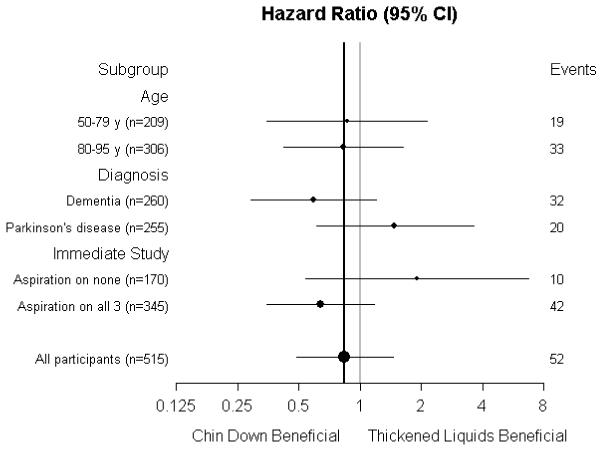

The 3-month Kaplan-Meier estimates of pneumonia in the nectar-thick and honey-thick liquid groups were 0.084 (10 events) and 0.150 (18 events), respectively (HR, 0.50 [CI, 0.23 to 1.09]; P = 0.083). When participants were stratified by short-term aspiration status, the 3-month Kaplan-Meier estimates of pneumonia in the nectar-thick and honey-thick liquid groups were 0.000 (0 events) and 0.084 (4 events), respectively (P = 0.051, log-rank test) for participants who aspirated during none of the interventions and 0.130 (10 events) and 0.195 (14 events), respectively (HR, 0.58 [CI, 0.26 to 1.31; P = 0.193), for participants who aspirated during on all 3 interventions. Figure 3 shows that the 95% CIs for the estimated effect of intervention within subgroups for pneumonia generally overlapped, and all contained the estimated HR for all participants. No diagnosis--intervention interaction effect was observed (P = 0.117). Using suspected pneumonia as an outcome did not materially alter the intervention effect estimates.

Figure 3.

A.Forest plot showing primary intervention effect for pneumonia in subgroups.

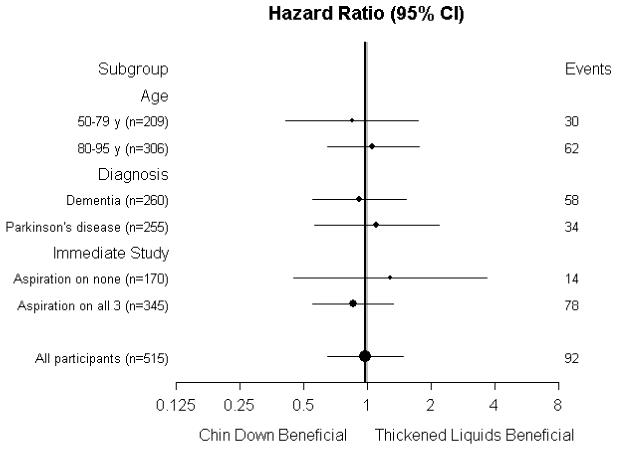

B. Forest plot showing primary intervention effect for pneumonia or death in subgroups.

Pneumonia or Death

The 3-month Kaplan-Meier estimates of pneumonia or death in the chin-down posture and thickened-liquid groups were 0.180 (46 events) and 0.183 (46 events), respectively (HR, 0.98 [CI, 0.65 to 1.48]; P = 0.94). The 3-month Kaplan-Meier estimates of pneumonia or death in the nectar-thick and honey-thick liquid groups were 0.163 (21 events) and 0.205 (25 events), respectively (HR, 0.76 [CI, 0.43 to 1.36]; P = 0.36).

Figure 3 shows that the 95% CIs for the estimated effect of intervention within subgroups for pneumonia or death generally overlapped, and all contained the estimated HR for all participants.

Adverse Events

Table 2 summarizes adverse events, hospitalizations, and mortality by intervention. Fourteen participants withdrew from the interventions because of an adverse event or hospitalization. One hundred nineteen participants (23%) had at least 1 adverse event during the study. The combined outcome of at least 1 dehydration, urinary tract infection, or fever event (all defined by the primary physician) was more frequent in the thickened-liquid groups than the chin-down posture group (23 patients vs. 12 patients [9% vs. 5%]; difference, 4 percentage points [CI, 0.3 to 9 percentage points]; P = 0.055). Withdrawals due to adverse experiences or hospitalizations were also more common in the thickened-liquid groups than the chin-down posture group (10 patients vs. 4 patients [4% vs. 2%]; difference, 2 percentage points [CI, -0.4 to 5 percentage points]; P = 0.112). Increased breathing difficulty was more frequent in the chin-down posture group (4 [2%] vs. 0; P = 0.124). Among participants assigned to thickened liquids, diarrhea was more frequent in the nectar-thick liquid group than in the honey-thick liquid group (5 patients vs. 0 patients [2% vs. 0%]; P = 0.061). Occurrence of a serious adverse event (life-threatening adverse event, hospitalization, or death) was balanced across primary and secondary intervention groups. Median length of hospital stay because of pneumonia for participants in the honey-thick liquid group was 18 days (6 events) compared with 6 days for the chin-down posture group (13 events) and 4 days for the nectar-thick liquid group (9 events).

Table 2.

Adverse Experiences, Hospitalizations, or Death, by Intervention

| N (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Chin Down (n=259) | Thickened Liquids (n=256) | Nectar-Thick (n=133) | Honey-Thick (n=123) |

| Participants with at least one adverse experience* | 51 (20%) | 68 (27%) | 38 (29%) | 30 (24%) |

| Dehydration | 6 (2%) | 15 (6%) | 7 (5%) | 8 (7%) |

| Urinary tract infection (UTI) | 8 (3%) | 16 (6%) | 11 (8%) | 5 (4%) |

| Fever | 4 (2%) | 10 (4%) | 7 (5%) | 3 (2%) |

| Weight loss | 4 (2%) | 6 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 3 (2%) |

| Fatigue/weakness | 4 (2%) | 6 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 3 (2%) |

| Vomiting | 3 (1%) | 7 (3%) | 5 (4%) | 2 (2%) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (<1%) | 5 (2%) | 5 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Increased breathing difficulty | 4 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| At least one dehydration, UTI, or fever event | 12 (5%) | 23 (9%) | 14 (11%) | 9 (7%) |

| At least one weight loss or fatigue event | 7 (3%) | 8 (3%) | 4 (3%) | 4 (3%) |

| Participants hospitalized at least once | 52 (20%) | 51 (20%) | 28 (21%) | 23 (19%) |

| Withdrawals from interventions due to adverse experience or hospitalization | 4 (2%) | 10 (4%) | 5 (4%) | 5 (4%) |

| Death | 32 (12%) | 29 (11%) | 15 (11%) | 14 (11%) |

| Serious adverse event* | 71 (27%) | 66 (26%) | 34 (26%) | 32 (26%) |

Adverse events occurring in 10 or more participants or those clinically meaningful are listed.

An outcome of life-threatening adverse experience, hospitalization, or death.

Adherence to the Intervention

Adherence was measured weekly across assessed meals and classified on a monthly basis as 0% to 25%, 26% to 50%, 51% to 75%, or 76% to 100% (Appendix Table, available at www.annals.org). Data on 31 of the 268 participants monitored for intervention adherence were too sparse to analyze, and compliance was not rated across 3 months of follow-up for an additional 74 participants. In the chin-down posture group, a higher proportion of participants with Parkinson disease had adherence greater than 50% compared with participants with dementia or Parkinson disease with dementia (91% vs. 57% to 58%). Adherence greater than 50% to the nectar-thick intervention across 3 months of follow-up was fairly even across diagnoses (67% to 73%). Adherence greater than 50% to the honey-thick intervention across 3 months of follow-up was highest among participants with dementia (91%), followed by participants with Parkinson disease (75%) and then by participants with Parkinson disease with dementia (56%). Cumulative pneumonia incidence in each intervention was similar among participants with adherence greater than 50% compared with the entire cohort. Among 340 participants for whom data are available about changes in therapy, 15 (4%) switched to a different therapy before the end of follow-up.

Electronic-only Table.

Compliance of >50% at each month, by intervention and diagnosis*

| Intervention | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chin Down | Nectar-thick | Honey-thick | |||||||

| Diagnosis | M1† | M2‡ | M3§ | M1 | M2 | M3 | M1 | M2 | M3 |

| Parkinson’s Disease (# with >50% compliance / # available) | 21/25 | 21/24 | 20/22 | 23/28 | 17/23 | 14/21 | 15/19 | 12/16 | 12/16 |

| >50% compliant (%) | 84% | 88% | 91% | 82% | 74% | 67% | 79% | 75% | 75% |

| Dementia (# with >50% compliance / # available) | 20/32 | 16/26 | 13/23 | 26/32 | 18/25 | 16/22 | 33/35 | 24/27 | 21/23 |

| >50% compliant (%) | 63% | 62% | 57% | 81% | 72% | 73% | 94% | 89% | 91% |

| PD with Dementia (# with >50% compliance / # available) | 12/17 | 7/12 | 7/12 | 15/18 | 13/17 | 11/15 | 9/14 | 8/10 | 5/9 |

| >50% compliant (%) | 71% | 58% | 58% | 83% | 76% | 73% | 64% | 80% | 56% |

| TOTAL (# with >50% compliance / # available) | 53/74 | 44/62 | 40/57 | 64/78 | 48/65 | 41/58 | 57/68 | 42/53 | 38/48 |

| >50% compliant (%) | 72% | 71% | 70% | 82% | 74% | 71% | 84% | 79% | 79% |

M1 = Month 1; M2 = Month 2; M3 = Month 3; PD = Parkinson’s disease

Numbers in M1 columns reflect participants whose compliance through the first month was > 50%.

Numbers in M2 columns reflect participants whose compliance was > 50% for both month 1 and month 2.

Numbers in M3 columns reflect participants whose compliance was >50% for all three months.

Discussion

We compared 2 common but untested interventions to prevent pneumonia---chin-down posture and thickened liquids---in persons with dementia or Parkinson disease who had a known tendency to aspirate liquid. By performing a systematic search of PubMed from January 1990 to December 2007 using the terms dysphagia, pneumonia, Parkinson’s disease and dementia, we identified no other studies that compared outcomes of such treatments in these populations.

We found a 3-month cumulative incidence of pneumonia of 11% across all enrolled participants. This rate was much lower than the rate assumed at study initiation and lower than a 3-month cumulative pneumonia incidence of 20% to 40% reported in elderly patients with stroke, dementia, or Parkinson disease or residing in nursing homes (20-22, 29-32). We cannot determine whether the lower rate in our sample represents an effect of intervention or changes over time in other health care delivery because we did not include a control group for no treatment.

Our study failed to reject the null hypothesis of no difference between the chin-down-posture and thickened-liquid interventions. Our results are consistent with differences as large as a 51% decrease in the HR for pneumonia and a 45% increase in the HR for pneumonia associated with the chin-down posture (HR, 0.84 [CI, 0.49 to 1.45]; P = 0.53). Our secondary results found that participants drinking nectar-thick liquids had a lower incidence of pneumonia than those drinking honey-thick liquids (HR, 0.50 [CI, 0.23 to 1.09]; P = 0.083), although the results do not exclude an increase in the HR for pneumonia of 9% associated with nectar-thick liquids compared with honey-thick liquids. Although only 10 cases of pneumonia occurred in the 170 participants for whom all of the conditions in the short-term trial worked equally well, no cases were reported in those randomly assigned to drink nectar-thick liquids for 3 months. These intriguing findings warrant further study. Nectar-thick liquids may be easier to clear from the airway than more viscous liquids, as indicated by the longer median length of hospital stay for participants randomly assigned to honey-thick liquid who developed pneumonia.

The common clinical assumption that “the thicker the liquid, the safer the swallow,” is largely based on short-term response and either bedside or videofluoroscopic evaluation (18). Our findings temper support for 3000-centipoise honey-thick liquid as an intervention in patients with dementia or Parkinson disease who aspirate thin liquid. Of note, however, we studied only participants who did not benefit preferentially from an intervention. It remains to be discovered whether participants for whom honey-thick fluid reduces aspiration preferentially in the fluoroscopy suite, and are then treated with honey-thick liquids, remain in better respiratory health with fewer or less severe adverse outcomes (for example, hospital length of stay if pneumonia occurred).

The outcomes of our study focus on important issues of clinical significance. The lower-than-expected pneumonia incidence in our sample changes the threshold at which clinicians, patients, or caregivers balance the risks and benefits of the available interventions. If one chooses to use an intervention with no proven effect on risk for aspiration and pneumonia, the chin-down posture, which allows the person to enjoy the taste and texture of thin liquids, is an option. Alternatively, choosing nectar-thick liquids, which require less training and oversight during the swallowing process, is also a reasonable choice. Moreover, in the neurodegenerative, often depressed critical care patients, choices as basic as drinking a cold glass of water or a hot cup of tea ultimately depend on the desires and judgments of the patients and their caregivers.

Our study has limitations. We did not include a no-treatment group because “no treatment” is unethical in the context of standard clinical care. The nature of the interventions did not allow blinding of direct care providers, although these individuals were not responsible for determining the primary outcome of pneumonia diagnosis. The 3-month follow-up period was short, but it was chosen to balance concern over attrition in a frail elderly population with sensitivity to develop detectible pneumonia. Adherence to prescribed interventions was, as expected, a problem. An “efficacy” study conducted in circumstances with intensive or optimal staffing that ensured adherence to interventions might show benefits of 1 therapy over another. However, staffing shortages and care provider “burnout” are known limitations that exist widely across institutional and even noninstitutional settings: findings from an “efficacy” study conducted in an unrealistic setting would not be generalizable.

In the end, given the lower-than-expected overall pneumonia incidence and the point estimates of pneumonia incidence for each intervention, it is difficult to argue that further study is needed to better quantify potential differences between chin-down posture and thickened liquids. Future investigation of chin-down posture combined with nectar-thick liquid may be warranted to determine whether use of both interventions simultaneously significantly decreases the pneumonia rate compared with use of either intervention alone. Our findings should prompt clinicians to question the practice of recommending very thick liquids (in this case, 3000 centipoise) without first evaluating all possible intervention options and considering of the relative cost burden to the patient and care providers, not just in terms of dollars but also quality of life.

From William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC), Madison, Wisconsin; The EMMES Corporation, Rockville, Maryland; University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin; Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois; ORC Macro, Calverton, Maryland; Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California; Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota; University of Miami Hospital and Clinics, Miami, Florida; New York Hospital Medical Center-Queens, Flushing, New York; Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, West Roxbury, Massachusetts; Richard L. Roudebush Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Indianapolis, Indiana; and American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Rockville, Maryland.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Susi Nehls, BS, for editing expertise; Abby Duane, BS, for preparing the manuscript; E. Kenneth Sullivan, PhD, for study design and statistical analysis; Carol Caperton Wenck, MS, CCRA, for coordination of the project; and Jeffrey Glassroth, MD, and Jeffrey Grossman, MD, for sharing their perspectives on critical care of patients with pneumonia.

Grant Support: By the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health (DC03206). Additional support for the grant was provided by Novartis and E-Z-EM to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Communication Sciences and Disorders Clinical Trials Research Group. This is GRECC Manuscript #2006-03.

References

- 1.Feinberg MJ, Knebl J, Tully J, Segall L. Aspiration and the elderly. Dysphagia. 1990;5:61–71. doi: 10.1007/BF02412646. PMID: 2209101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Census Bureau Accessed at http://www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html on 29 November 2007.

- 3. ECRI Institute. Diagnosis and Treatment of Swallowing Disorders (Dysphagia) in Acute-Care Stroke Patients. Evidence Report/Technical Assessment No. 8. (Prepared by ECRI Evidence-Based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-97-0020). AHCPR Publication no 99-E024. Plymouth Meeting, PA, Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research; 1999. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=hstat1.chapter.11701 on October 30, 2007.

- 4.LaCroix AZ, Lipson S, Miles TP, White L. Prospective study of pneumonia hospitalizations and mortality of U.S. older people: the role of chronic conditions, health behaviors, and nutritional status. Public Health Rep. 1989;104:350–60. PMID: 2502806. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niederman MS, McCombs JS, Unger AN, Kumar A, Popovian R. The cost of treating community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Ther. 1998;20:820–37. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(98)80144-6. PMID: 9737840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baine WB, Yu W, Summe JP. Epidemiologic trends in the hospitalization of elderly Medicare patients for pneumonia, 1991-1998. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1121–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1121. PMID: 11441742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipsky BA, Boyko EJ, Inui TS, Koepsell TD. Risk factors for acquiring pneumococcal infections. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:2179–85. PMID: 3778047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonda D, Schwarz J, Clinnick S. Parkinsonian medication one hour before meals improves symptomatic swallowing: a case study. Dysphagia. 1995;10:165–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00260971. PMID: 7614856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robbins JA, Logemann JA, Kirshner HS. Swallowing and speech production in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:283–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190310. PMID: 3963773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groher ME, McKaig TN. Dysphagia and dietary levels in skilled nursing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:528–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06100.x. PMID: 7730535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chidester JC, Spangler AA. Fluid intake in the institutionalized elderly. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97:23–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00011-4. quiz 29-30. [PMID: 8990413] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chernoff R. Nutritional requirements and physiological changes in aging. Nutr Rev. 1994;52:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welch MV, Logemann JA, Rademaker AW, Kahrilas PJ. Changes in pharyngeal dimensions effected by chin tuck. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:178–81. PMID: 8431103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shanahan TK, Logemann JA, Rademaker AW, Pauloski BR, Kahrilas PJ. Chin-down posture effect on aspiration in dysphagic patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:736–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(93)90035-9. PMID: 8328896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasley A, Logemann JA, Kahrilas PJ, Rademaker AW, Pauloski BR, Dodds WJ. Prevention of barium aspiration during videofluoroscopic swallowing studies: value of change in posture. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160:1005–9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.5.8470567. PMID: 8470567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Logemann JA, Rademaker AW, Pauloski BR, Kahrilas PJ. Effects of postural change on aspiration in head and neck surgical patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;110:222–7. doi: 10.1177/019459989411000212. PMID: 8108157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Logemann JA, Shanahan T, Rademaker AW, Kahrilas PJ, Lazar R, Halper A. Oropharyngeal swallowing after stroke in the left basal ganglion/internal capsule. Dysphagia. 1993;8:230–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01354543. PMID: 8359043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Logemann JA, Gensler G, Robbins JA, Lindblad AS, Brandt DK, Hind JA, et al. A randomized study of three interventions for aspiration of thin liquids in patients with dementia or Parkinson’s disease. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51:173–183. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brandt DK, Hind JA, Robbins J, Lindblad AS, Gensler G, Gill G, et al. Challenges in the design and conduct of a randomized study of two interventions for liquid aspiration. Clin Trials. 2006;3:457–68. doi: 10.1177/1740774506070731. PMID: 17060219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loeb M, McGeer A, McArthur M, Walter S, Simor AE. Risk factors for pneumonia and other lower respiratory tract infections in elderly residents of long-term care facilities. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2058–64. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.17.2058. PMID: 10510992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pick N, McDonald A, Bennett N, Litsche M, Dietsche L, Legerwood R, et al. Pulmonary aspiration in a long-term care setting: clinical and laboratory observations and an analysis of risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:763–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb03731.x. PMID: 8675922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langmore SE, Terpenning MS, Schork A, Chen Y, Murray JT, Lopatin D, et al. Predictors of aspiration pneumonia: how important is dysphagia? Dysphagia. 1998;13:69–81. doi: 10.1007/PL00009559. PMID: 9513300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demets DL, Ware JH. Asymmetric group sequential boundaries for monitoring clinical trials. Biometrika. 1982;69:661–63. [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics. 1979;35:549–56. PMID: 497341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pocock SJ. Group sequential methods in the design and analysis of clincal trials. Biometrika. 1977;64:191–99. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lan KK, Wittes J. The B-value: a tool for monitoring data. Biometrics. 1988;44:579–85. PMID: 3390511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher RA. On the interpretation of χ2 from contingency tables, and the calculation of P. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1922;85:87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan E, Meier P. J Amer Statist Assn. Vol. 53. Univ. California Radiation Laboratory; University of Chicago; CA: IL: 1958. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations; pp. 457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakazawa H, Sekizawa K, Ujiie Y, Sasaki H, Takishima T. Risk of aspiration pneumonia in the elderly [Letter] Chest. 1993;103:1636–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.5.1636b. PMID: 8486071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gambassi G, Landi F, Lapane KL, Sgadari A, Mor V, Bernabei R. Predictors of mortality in patients with Alzheimer’s disease living in nursing homes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;1:59–65. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.1.59. PMID: 10369823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gambassi G, Lapane KL, Landi F, Sgadari A, Mor V, Bernabie R, Systematic Assessment of Geriatric drug use via Epidemiology (SAGE) Study Group Gender differences in the relation between comorbidity and mortality of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1999;53:508–16. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.3.508. PMID: 10449112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Louis ED, Marder K, Cote L, Tang M, Mayeux R. Mortality from Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:260–4. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550150024011. PMID: 9074394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]