Abstract

Hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy) is associated with atherosclerotic events involving the modulation of arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism and the activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9). Cytochrome P450 (CYP) epoxygenase- 2J2 (CYP2J2) is abundant in the heart endothelium, and its AA metabolites epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) mitigates inflammation through NF-κβ. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms for MMP-9 regulation by CYP2J2 in HHcy remain obscure. We sought to determine the molecular mechanisms by which P450 epoxygenase gene transfection or EETs supplementation attenuate homocysteine (Hcy)-induced MMP-9 activation. CYP2J2 was over-expressed in mouse aortic endothelial cells (MAECs) by transfection with the pcDNA3.1/CYP2J2 vector. The effects of P450 epoxygenase transfection or exogenous supplementation of EETs on NF-κβ-mediated MMP-9 regulation were evaluated using Western blot, in-gel gelatin zymography, electromobility shift assay, immunocytochemistry. The result suggested that Hcy downregulated CYP2J2 protein expression and dephosphorylated PI3K-dependent AKT signal. Hcy induced the nuclear translocation of NF-κβ via downregulation of IKβα (endogenous cytoplasmic inhibitor of NF-κβ). Hcy induced MMP-9 activation by increasing NF-κβ –DNA binding. Moreover, P450 epoxygenase transfection or exogenous addition of 8,9-EET phosphorylated the AKT and attenuated Hcy-induced MMP-9 activation. This occurred, in part, by the inhibition of NF-κβ nuclear translocation, NF-κβ –DNA binding and activation of IKβα. The study unequivocally suggested the pivotal role of EETs in the modulation of Hcy/MMP-9 signal.

Keywords: Endothelial dysfunction, Matrix remodeling, Arachidonic acid, EETs, HETE, Signal transduction, Gene overexpression

Introduction

Alteration in extracellular matrix (ECM) turnover by matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) plays a pivotal role in the progression of vascular pathology. MMPs are classified as zinc-dependent proteinases capable of degrading structural components of ECM (Creemer et al. 2001; Spinale, 2002). MMPs are synthesized as latent enzymes, and their proteolytic activation is fueled by increase in oxidative stress (Galis and Khatri, 2002; Moshal et al. 2005) and calcium load (Ko et al. 2005). The elevated blood levels of Hcy are known as hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy). There are three ranges of HHcy: moderate (10-30 μM), intermediate (31-100 μM), and severe (> 100 μM).

A myriad of research suggested that the increased expression of MMPs, especially MMP-9 led to vascular pathology in HHcy. Hcy induced oxidative stress and activated MMP-9 (Tyagi et al. 2005; Moshal et al. 2006; Moshal et al. 2006). Hcy caused endocardial endothelial dysfunction (Miller et al. 2000; Miller et al. 2002) and impaired microvascular endothelial cell (MVEC) function in vivo (Ungravi et al. 2002). All these effects were attributed to MMP-9 activation. It was observed that induction of HHcy in apoE-null mice increased the atherosclerotic area and enhanced the expression of MMP-9 in vasculature (Hofmann et al. 2001). Solini et al. (2006) suggested that an increased MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity led to atherosclerosis in HHcy. Collectively, these observations supported the critical role of MMP-9 in HHcy-associated atherosclerotic events. However, the knowledge of the molecular mechanisms for MMP-9 regulation in HHcy remains enigmatic.

Various reports projected the importance of arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism in the atherosclerotic-related events (Fleming et al. 2001). However, the modulation of AA metabolomics in HHcy is not well understood. It was reported that Hcy modulated AA pathway and increased the proclivity to atherosclerosis (Signorello et al. 2002; Leoncini et al. 2006). These observations prompted us to look into the role of EETs in modulation of Hcy/MMP-9 signal.

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) epoxygenases of the 2B, 2C and 2J subfamilies are expressed in endothelial cells and metabolizes AA to four regioisomeric epoxides: 5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12- and 14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid or EETs. The CYP2J2 isoform is abundant in vascular endothelium (Wu et al. 1996), and its AA metabolites are cardioprotective (Node et al. 1999). CYP-derived EETs act as intracellular signal transduction molecules and exert their effect by the activation of kinase cascades (Fleming et al. 2001). In addition, EETs inhibit activation and nuclear translocation of NF-κβ (Node et al. 1999). Yang et al. (2001) suggested downregulation of CYP2J2 and EETs in aortic endothelial cells during ischemia and reperfusion. Michaelis et al. (2005) observed that the CYP2C9-derived EETs induced the MMP activation and matrix degradation during hypoxia. Several studies suggested the role of CYP2J2 in the cardiovascular system and emphasized its importance as an anti-atherosclerotic enzyme.

Since Hcy causes modulation of AA, and its pathological effects are mediated by the kinase pathways, it is tempting to speculate the involvement of CYP epoxygenase and EETs in the modulation of Hcy/MMP-9 signal. We have designed a mechanistic study to determine, whether and by which molecular mechanisms, CYP epoxygenase and EETs regulate MMP-9 in HHcy.

Materials and Methods

Materials

EETs were purchased from BIOMOL International (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Sodium orthovandate, DL-homocysteine, gelatin, β-actin and other chemicals for buffer preparation were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Anti-phospho-AKT antibody was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Anti-MMP-9 antibody, and NF-κβ blocking peptide were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-RelA (p65), anti-AKT antibodies, and wortmannin were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti-calpain-1 (domain-IV) and anti-oct-1 antibodies obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) were used.

Cell culture, expression vectors and transfections

Mouse aortic endothelial cell (MAEC) cells was a kind gift from Dr. Kathleen Bove (Stratton VA Medical Center, Albany, NY) and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/Ham's F-12 50/50 (Cellgro, Kansas City, MP), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% L-glutamine.

The CYP2J2 cDNA (1.876 kilobase pairs; GenBank accession number U37143) or GFP cDNA (0.75 kilobase pairs) subcloned into the plasmid pcDNA3.1 was prepared as described (Node et al. 1999; Yang et al. 2001). pcDNA3.1/GFP and pcDNA3.1/CYP2J2 plasmids were purified using QIAGEN Plasmid Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Chatsworth, CA) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. MAECs were grown to 50-60% confluence in OPTI MEM medium. Then, MAECs were transfected with pcDNA3.1/GFP and pcDNA3.1/CYP2J2 plasmids (0.2 μg DNA/cm2) using FuGENE 6 Transfection Reagent (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Forty- eight hours after transfection, the percent transfection efficiency was determined by examining pcDNA3.1/GFP transfected cells for GFP fluorescence using laser confocal microscope Fluo View 1000 (Olympus). CYP2J2 expression levels were determined by Western blotting.

Western blot analysis

After transfection, MAECs were treated for 30 min with or without PI3 Kinase inhibitor (wortmannin μM; 0.5, 1), PI3K activator (sodium orthovandate μM; 100, 200), and 8,9-EET (μM; 0.1, 1, 2) prior to 6 hrs Hcy (100 μM) treatment. Cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail. The protein concentration was determined using Bio-Rad protein assay dye. Equal amount of protein (50 μg) was subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane (BioRad laboratories, Hercules, CA). Immunoblotting was performed with primary antibodies against CYP2J2, which was prepared as described (Ma et al. 1999). This anti-CYP2J2 antibody does not react with other CYP isoforms(Node et al. 1999: Wu et al. 1996). The anti-phospho AKT, anti-AKT and anti-Rel A/p65, and anti-β-actin antibodies were used. Corresponding secondary antibodies were applied and blots were developed using ECL plus substrate (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Densitometric analysis was carried out on Western blots using UMAX PowerLock II (Taiwan, ROC) program.

Conditioned media and in-gel gelatin zymography for MMP activity

MAECs were cultured in 100 mm Petri dishes and were serum starved before the indicated treatments. After forty-eight hours of transfection, MAECs were treated with or without Hcy for 6 hours. Other Petri dishes received the treatment with 8,9 or 11,12-EET (1 μM), PI3 Kinase inhibitor (wortmannin 1μM), and sodium peroxyvandate (200 μM) for 30 minutes, NF-κβ blocking peptide (25 μg/ml) for 3 hrs prior to the Hcy (100 μM) treatment for 6 hours. The NF-κβ blocking peptide contained the amino acid sequence AAVALLPAVLLALLAPVQRKRQKLMP. Wortmannin is a potent specific and direct inhibitor of PI3 Kinase. The gelatinolytic activity of MMP-9 and MMP-2 was detected in the conditioned media as described (Moshal et al. 2006). Briefly, 80 μg of the protein was subjected to 7.5% non-reducing SDS-PAGE with gelatin (1mg/ml) as a substrate for MMPs. After electrophoresis, gels were washed with renaturation buffer (2.5% triton X-100) and incubated overnight at 37°C with continuous shaking in activation buffer (Tris 50 mM [pH 7.4], 0.8% NaCl, 0.02% NaN3, and 5 mM CaCl2). Gels were stained with 0.5% coomassie brilliant blue R-250 and gelatinolytic activity was detected as clear bands against dark background. Quantitative analysis was performed using UMAX PowerLock II (Taiwan, ROC) software.

RelA/p65 translocation assay

Cells were serum starved, pretreated with 8,9-EET, and transfected with pcDNA3.1/CYP2J2 followed by incubation with Hcy (100 μM) for 6 hrs. After the treatment, cells were trypsinized, washed with PBS and used for preparation of nuclear and cytosolic extract as described (Philip and Kundu, 2003). Cells were re-suspended in buffer A (mM; 10 HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 1.5 MgCl2, 0.5 DTT and 0.2 PMSF) and allowed to swell on ice for 15 minutes. Cells were vortexed and centrifuged at 20,000×g for 15 seconds. The supernatant represented the cytosolic extract. The cell pellet was re-suspended in buffer B (mM; 20 HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 420 NaCl, 1.5 MgCl2, 0.2 EDTA, 0.5 DTT, 0.2 PMSF and 25% glycerol) and incubated on ice for 20 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 20,000×g for 2 minutes in cold. The supernatant was used as nuclear extract. The purity of cytosolic and nuclear extract was determined by Western blot with anti-calpain-1 (domain-IV) and anti-oct-1 antibodies, respectively. Protein concentration was determined in nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts and equal amount of protein was placed on 10% SDS-PAGE for electrophoresis, driven onto the PVDF membrane. Immunoblotting was performed on cytosolic and nuclear extract with polyclonal rabbit anti- RelA/p65 antibody. Corresponding secondary antibodies were applied and blots were developed using ECL plus substrate.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

After pcDNA3.1/CYP2J2 transfection and the indicated treatments, nuclear extract were prepared and assayed for protein concentration as described in Rel A translocation assay. Biotin labeled NF-κβ probe with sequence AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC was purchased from Panomics Inc. (Fermont, CA) and EMSA was performed. Six μg of the nuclear extracts were incubated with 10ng of biotin- labeled NF-κβ probe in binding buffer containing 1μg/ μl of polydeoxyinosinic deoxycitidylic acid (poly (dI-dC)). The DNA-protein complex was resolved on six-percent native polyacrylamide gel and electroblotted on the Pall Biodyne B nylon membrane (Pall Corporation, Cortland, NY). After transfer, the membranes were baked for 1 hour at 80°C and UV cross-linked for 3 minutes followed by probing with streptavidin-HRP conjugate. After incubating with detection buffer, the membranes were developed using HOPE Micro-Max X-ray film processor.

Immunoconfocal staining for intracellular MMP-9 and p65/Rel A nuclear translocation

MAECs were cultured in an 8-well chamber. Cells were treated with or without 8,9-EET (3 μM) for 30 mins followed by Hcy (100 μM) treatment for 6 hours. Cells were fixed and permeabilized with 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS containing lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC; 0.1 mg/ml). After blocking with 1% FCS in PBS, cells were incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti- RelA/p65 antibody (1:200 dilution) or monoclonal mouse anti-MMP-9 antibody at a 1:200 dilution for 1 hour at room temperature. The corresponding fluorescence-conjugated (1:800 dilution) secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used after incubation. The cells were washed and images were acquired using laser confocal microscope Fluo View 1000 (Olympus).

Statistics

Experiments were performed at least in triplicate, unless otherwise mentioned. Data is expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Bonferonni corrections. *p < 0.05 versus control and #p < 0.05 versus the Hcy treatment was considered statistically significant.

Results

Hcy-induced MMP-9 parallels a decrease in CYP2J2 protein expression and is PI3K-dependent

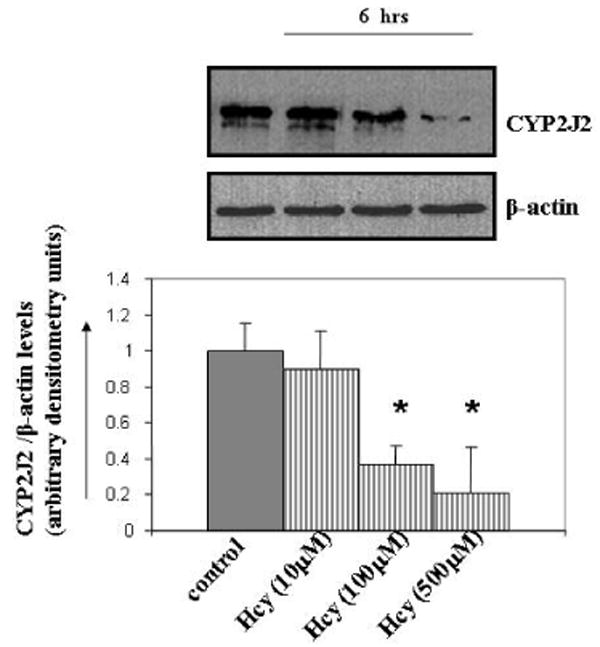

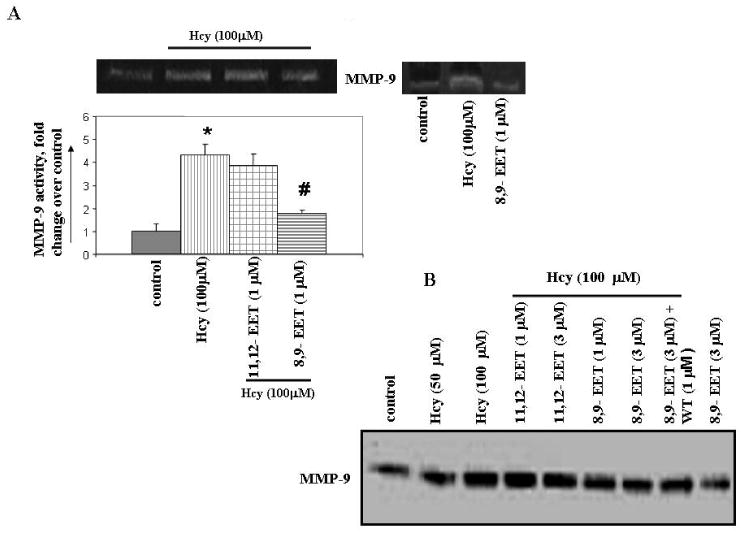

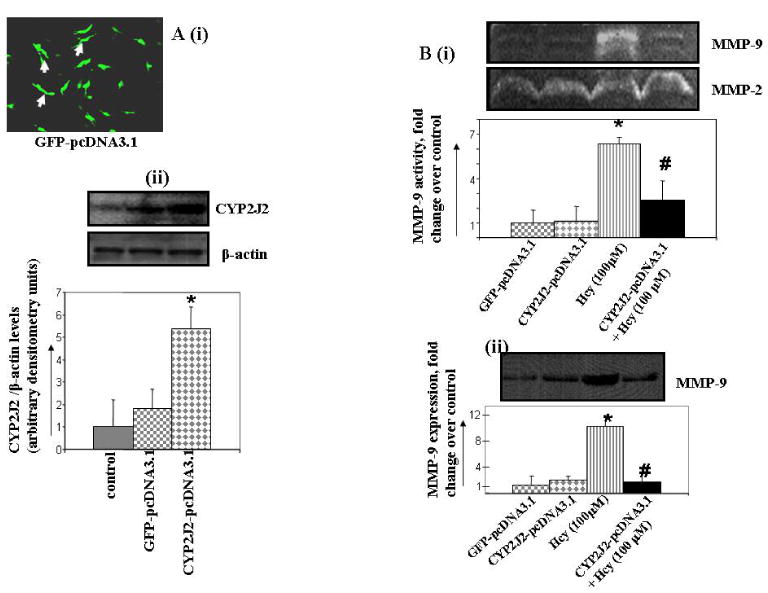

To determine if CYP2J2 expression was modulated by Hcy and whether this process involved the effect of EETs on the Hcy/MMP-9 signaling axis, MAECs were incubated with different concentrations of Hcy for 6 hours. Immunoblotting with CYP2J2 antibody revealed that MAECs expressed abundant CYP2J2 and that Hcy treatment downregulated CYP2J2 expression (Figure 1). We tested the effect of exogenous EETs on MMP-9 induction. Interestingly, we observed that 8,9-EET, but not 11,12-EET, attenuated the Hcy-induced MMP-9 expression and activity (Figure 2A, B). This suggested that functional effects of EETs occurred via activation of different signal pathways. We used a pharmacological inhibitor of PI3K signal pathway (wortmannin) and showed that 8,9-EET attenuated Hcy-induced MMP-9 via PI3K-dependent pathway (Figure 2B, C). Supplementation of 8,9-EET prior to the Hcy treatment reflected a decrease in punctate staining pattern for MMP-9 when compared to Hcy treatment alone (Figure 2D). However, the basal levels of MMP-9 were not affected with EETs treatment (Figure 2A right panel, and B) or by WT (data not shown). Based on these findings we concluded that: (a) Hcy decreased CYP2J2 expression in dose-dependent manner; and (b) the addition of synthetic 8,9-EET attenuated Hcy-induced MMP-9 via PI3K-dependent signal.

Figure 1.

The effect of Hcy treatment on the CYP2J2 expression. MAEC were serum starved and treated with different doses of Hcy (μM; 10, 100, and 500) for 6 hrs. PBS treated cells were used as control. After the treatments, cells were lysed and equal amount of proteins were immunoblotted with an antibody to CYP2J2. Treatments are indicated below each part. A representative Western blot for CYP2J2 expression levels is shown in gel panel. β-actin was used as loading control. Bar graphs are the representative of three experiments. CYP2J2 expression levels were quantitated and normalized to the levels of β-actin. *p < 0.05

Figure 2.

The effect of 8,9- and 11,12-EETs supplementation on Hcy-induced MMP-9 activity / expression and the involvement of PI3K pathway. MAECs were serum starved and treated with or without EETs, WT, and NF-κβ blocking peptide followed by incubation with Hcy for 6 hrs. Conditioned media was assayed for MMP-9 activity (A, C) using in-gel gelatin zymography and expression (B) by Western blot. MMP-9 activity is represented as fold change compared to control. D, Immunostaining for MMP-9 expression. The punctate staining pattern for MMP-9 is represented by white solid arrows. We have brightened the images for all experiments equally to enhance the quality. To enable the comparison of changes in fluorescence intensity, the images were acquired under identical set of conditions for all treatment groups. *p < 0.05 versus control; #p < 0.05 versus Hcy treatment.

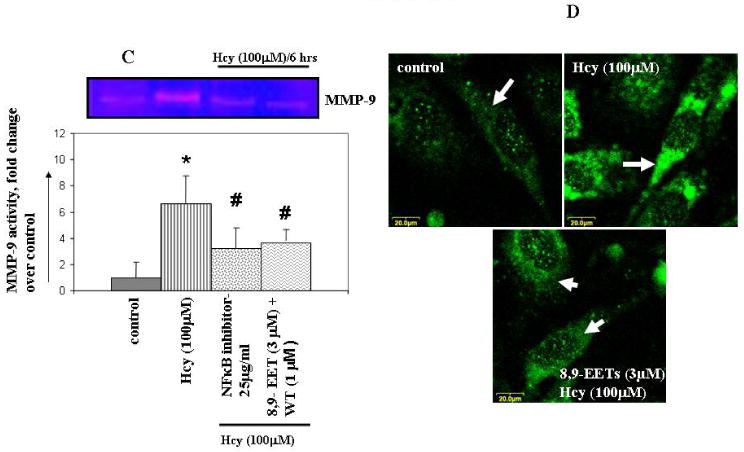

CYP2J2 transfection attenuates Hcy-induced MMP-9

To determine the effect of P450 epoxygenase transfection on the Hcy/MMP-9 signal axis, MAECs were transfected with either pcDNA3.1/GFP or pcDNA3.1/CYP2J2. After forty-eight hours, approximately 15-20 percent of cells were positive for green fluorescence as evidenced by confocal imaging (Figure 3Ai). Immunoblotting showed a 4-5 fold increase in CYP2J2 protein levels (Figure 3Aii) when compared to pcDNA3.1/GFP transfected MAECs. In another experiments, after 48 hours of CYP2J2 transfection cells were serum deprived and incubated with or without Hcy-100 μM for 6 hours. However, no significant change was observed in the CYP2J2 protein expression compared to non-transfected cells in transfection experiments with an empty vector for CYP2J2. CYP2J2 transfection attenuated the Hcy-induced MMP-9 activity/expression (Figure 3Bi and ii). We concluded that CYP2J2 transfection increased CYP2J2 expression and attenuated Hcy-induced MMP-9 expression/activity.

Figure 3.

The effect of P450 epoxygenase transfection on Hcy-induced MMP-9 expression/activity. Cells were transfected with either pcDNA3.1/GFP or pcDNA3.1/CYP2J2. After 48 hour of transfection prior to Hcy treatment for 6 hrs; A (i) Expression levels of CYP2J2 were determined using confocal imaging and Western blot. B (i, ii) Conditioned media was analyzed for MMP-9 activity and expression. *p < 0.05 versus control; #p < 0.05 versus Hcy treatment.

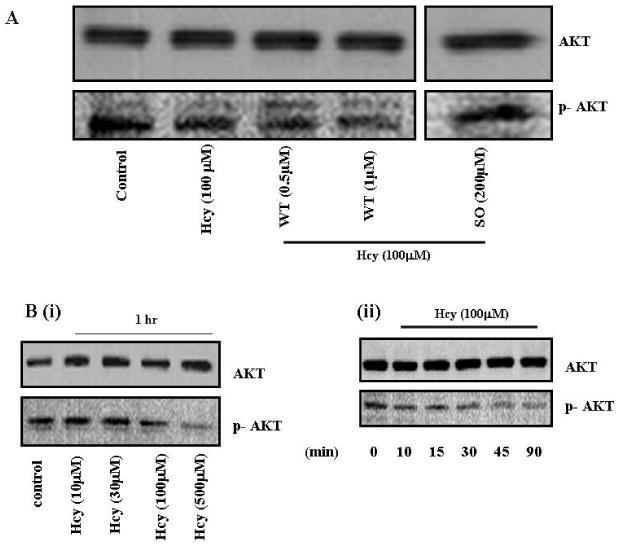

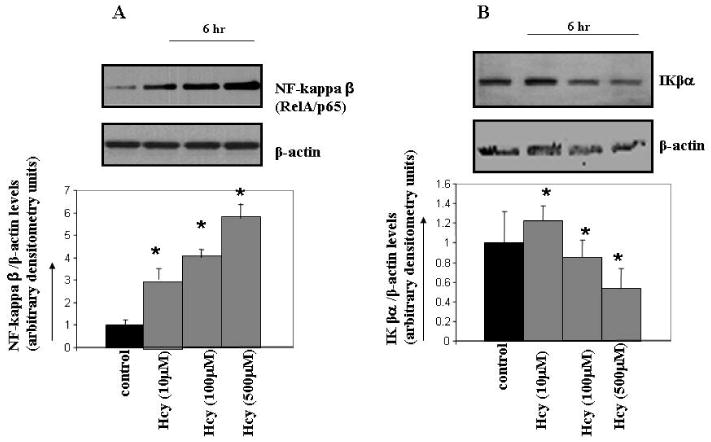

Hcy dephosphorylates PI3K/AKT

Hcy inhibited PI3K-dependent AKT phosphorylation in time and dose-dependent manner and suggested the involvement of PI3K/AKT signal pathway (Figure 4A and B). The basal levels of AKT phosphorylation were not affected with WT or SO treatment alone (data not shown). We concluded that: (a) Hcy signaled through PI3K/AKT pathway; and (b) Hcy mediated PI3K-dependent AKT dephosphorylation in cultured MAECs.

Figure 4.

The effect of Hcy treatment on PI3K-dependent AKT phosphorylation. A, MAECs were serum starved and treated with or without WT and SO followed by incubation with Hcy for 1 hr. Cell lysates were analyzed for phosphorylation of AKT using Western blot. The blots were re-probed for total AKT as a loading control. Treatments are indicated below each part. B, Representative Western blot for dose and time-dependent dephosphorylation of AKT signal by Hcy is shown in the gel panel.

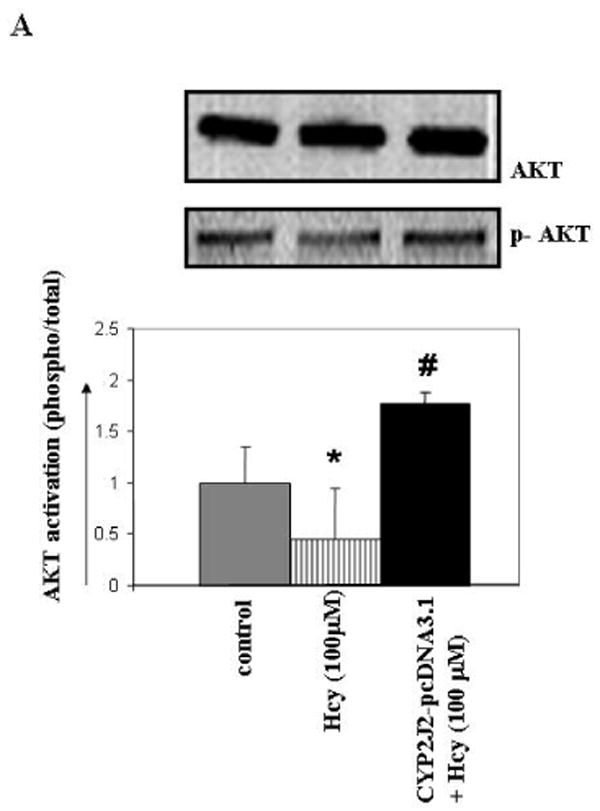

P450 epoxygenase transfection or exogenous administration of 8,9-EET activates PI3K-dependent AKT phosphorylation

Hcy decreased PI3K-dependent AKT phosphorylation, while P450 epoxygenase transfection, followed by Hcy treatment increased AKT phosphorylation (Figure 5A). Similarly, exogenous addition of 8,9-EET increased AKT phosphorylation in concentration and time-dependent manner (Figure 5B). The basal levels of AKT phosphorylation were not affected with P450 gene transfection or EETs treatment alone (data not shown). We concluded that pcDNA3.1/CYP2J2 transfection or 8,9-EET treatment caused an increase in AKT phosphorylation.

Figure 5.

The effect of P450 epoxygenase transfection or exogenous administration of 8,9-EET on AKT phosphorylation in HHcy. Representative Western blot for AKT phosphorylation in CYP2J2 transfected (A), and synthetic 8,9-EET treatment prior to incubation with Hcy for 1hr is shown. Membranes were stripped and re-probed for total AKT as a loading control. Results are the representative of at least three experiments. AKT phosphorylation is plotted as fold change over control. *p < 0.05 versus control; #p < 0.05 versus Hcy treatment.

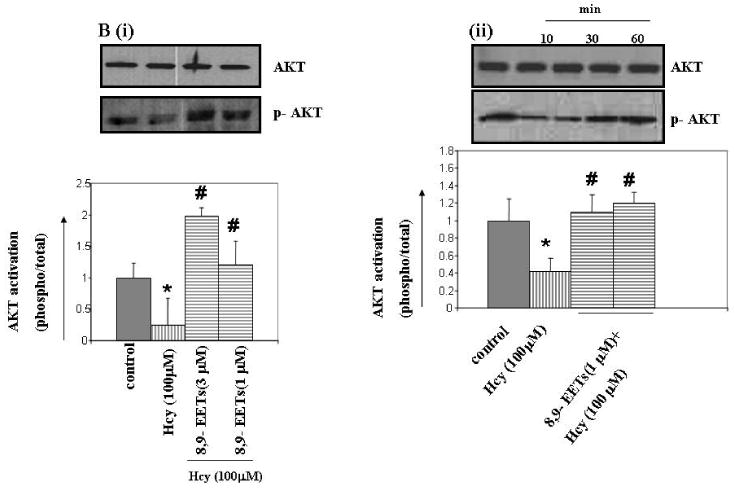

Hcy inhibits IKβα protein, activates NF-κβ (relA/p65) and regulates MMP-9

Hcy activated NF-κβ in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 6A). Pretreatment with NF-κβ blocking peptide ablated Hcy-induced MMP-9 (Figure 2C). The treatment with NF-κβ blocking peptide alone didn't affected MMP-9 activity (data not shown). Since IKβα is the inhibitor of NF-κβ and inhibits transcriptional activation of the target genes by blocking its nuclear translocation, we observed that Hcy treatment decreased IKβα levels (Figure 6B). These observations suggested that Hcy activated NF-κβ by inhibiting IKβα levels leading to MMP-9 induction.

Figure 6.

The effect of Hcy treatment on NF-κβ and IKβα expression levels. Cells were serum starved and treated with or without Hcy for 6 hrs. A representative immunoblot probed with anti- NF-κβ antibody (A) and anti- IKβα antibody (B) is shown. Results are representative of three experiments. Protein expression levels of IKβα and NF-κβ were quantitated and represented as bar graph. *p < 0.05

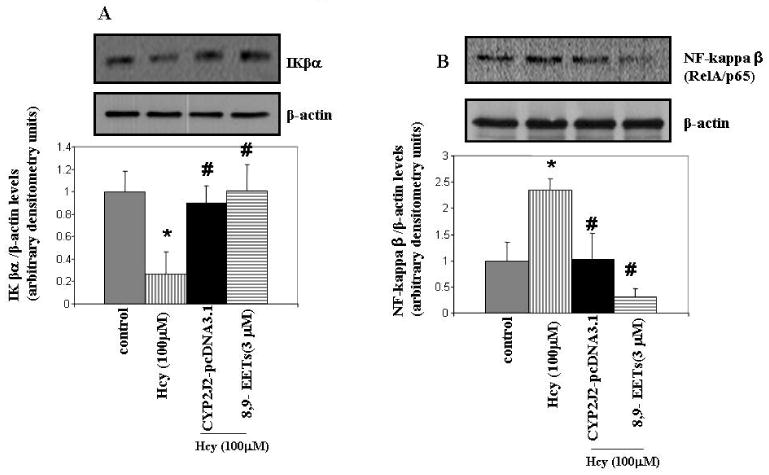

P450 epoxygenase gene transfection or exogenous supplementation of 8,9-EET increases IKβα levels and attenuates NF-κβ (RelA/p65) levels

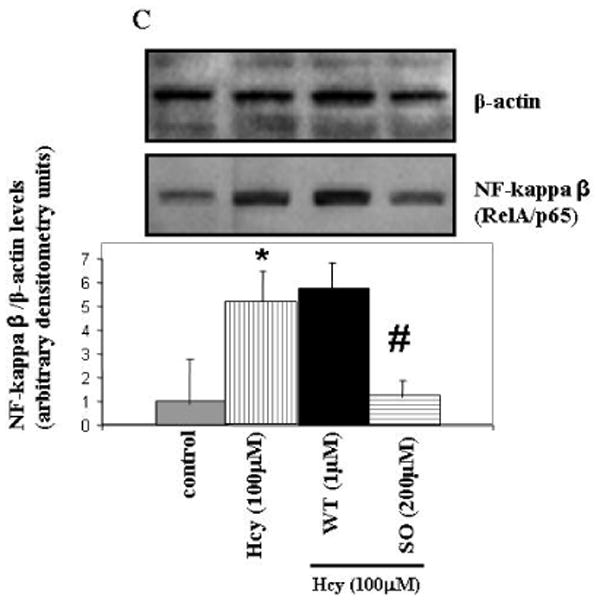

To determine whether P450 epoxygenase transfection or administration of 8,9-EET attenuated Hcy-induced MMP-9 by inhibition of NF-κβ, we measured IKβα and NF-κβ levels. CYP2J2 overexpression or addition of synthetic 8,9-EET increased IKβα levels and attenuated NF-κβ levels (Figure 7 A and B). The use of pharmacological inhibitor and activator of PI3K pathway suggested the involvement of PI3K/AKT signal in the modulation of NF-κβ activation (Figure 7C). Since NF-κβ activation involves the nuclear translocation of NF-κβ subunit Rel A, we assessed the effect of P450 epoxygenase transfection, or exogenous supplementation of 8,9-EET on RelA/p65 subcellular distribution. It was observed that Hcy treatment increased RelA/p65 expression in nuclear extract compared to control. Furthermore, CYP2J2 overexpression or supplementation of 8,9-EET prevented RelA/p65 expression in nuclear compartment (Figure 8A). Although, the predominant localization of RelA/p65 was in the cytoplasmic compartment, RelA/p65 showed an intense nuclear accumulation after Hcy treatment. CYP2J2 overexpression or 8,9-EET supplementation prevented nuclear accumulation of RelA (Figure 8B). There was no significant change in the basal levels of RelA/p65 and IKβα protein levels with either P450 gene transfection, EETs, WT or SO treatment alone (data not shown). We concluded that P450 epoxygenase transfection or 8,9-EET supplementation increased IKβα levels and prevented the nuclear accumulation of NF-κβ.

Figure 7.

The effect of P450 epoxygenase transfection or exogenous addition of 8,9-EET on NF-κβ and IKβα expression levels in HHcy. After CYP2J2 gene transfection or treatment with 8,9-EET, protein was electroblotted to determine IKβα (A) and NF-κβ (B) levels. Cells were treated with or without WT and SO followed by incubation with Hcy for 6 hrs. The cell lysates were electroblotted with anti- NF-κβ (relA/p65) antibody. (C). Protein levels of IKβα and NF-κβ (relA/p65) were normalized with β-actin and represented as bar graph (n=3). *p < 0.05 versus control; #p < 0.05 versus Hcy treatment.

Figure 8.

The effect of P450 epoxygenase transfection or exogenous addition of 8,9-EET on NF-κβ nuclear translocation in HHcy. A, After transfection with CYP2J2 gene or synthetic 8,9-EET (1 μM) treatment the cells were incubated with Hcy. The nuclear and cytosolic extracts were immunoblotted for NF-κβ expression. B, Cell were incubated with or without 8,9-EET followed by Hcy treatment and the NF-κβ expression was determined using confocal imaging. Images were acquired using Laser Confocal Microscope, FluoView 1000 (Olympus).

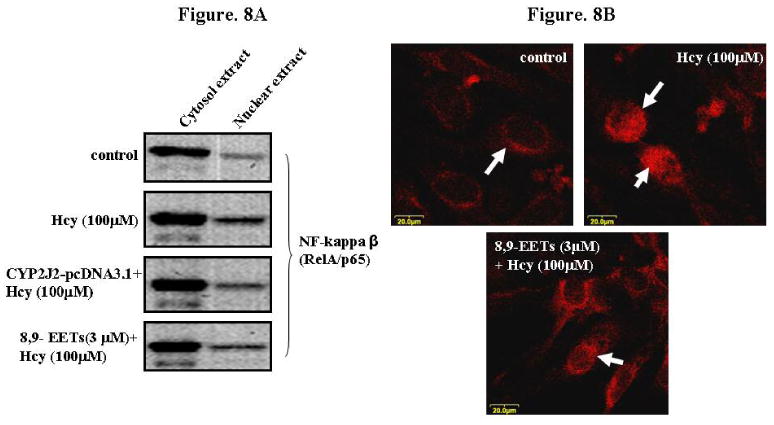

P450 epoxygenase transfection or exogenous supplementation of 8,9-EET inhibits Hcy-induced NF-κβ-DNA activity

We determined whether P450 epoxygenase transfection or 8,9-EET supplementation modulated the formation of NF-κβ -DNA complex. Nuclear extracts were prepared and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed. We observed that Hcy increased NF-κβ -DNA activity. Also, P450 epoxygenase transfection or supplementation of 8,9-EET attenuated the Hcy-induced NF-κβ -DNA activity (Figure 9). We concluded that CYP2J2 overexpression or 8,9-EET supplementation decreased the Hcy-induced NF-κβ -DNA binding activity.

Figure 9.

The effect of P450 epoxygenase transfection or exogenous addition of synthetic 8,9-EET on NF-κβ protein–DNA binding in HHcy. After pcDNA3.1/CYP2J2 transfection or synthetic 8,9-EET (1 μM) treatment followed by incubation with Hcy, the nuclear extract were processed for electrophoretic mobility shift assay to determine the NF-κβ-DNA binding activity. The position of NF-κβ protein–DNA complexes and nonspecific band (NS) is indicated. NF-κβ-DNA binding activity is represented as fold change compared to control.

Discussion

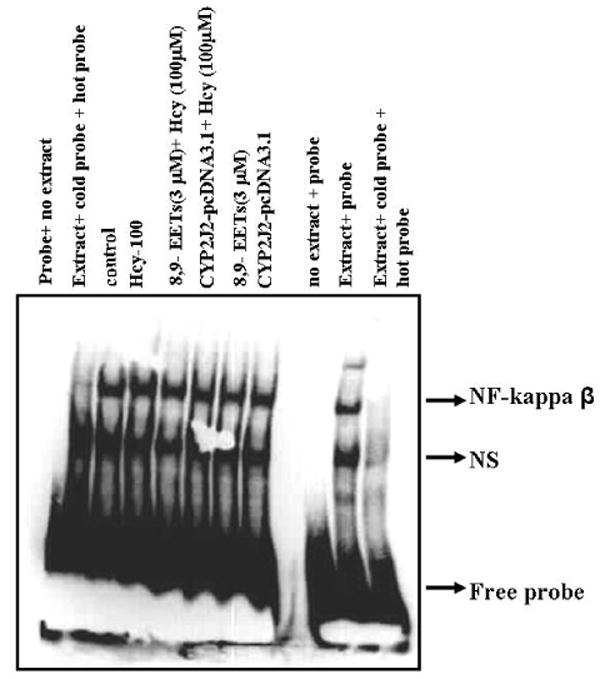

Hcy reduced the CYP2J2 expression and activated MMP-9. This involved the dephosphorylation of PI3K-dependent AKT signals. Hcy caused activation and nuclear translocation of NF-κβ via downregulation of IKβα. Hcy increased the NF-κβ -DNA binding activity leading to MMP-9 induction. Additionally, P450 epoxygenase transfection or exogenous administration of 8,9-EET phosphorylated AKT and abolished the Hcy-induced MMP-9, in part, by the inhibition of NF-κβ and IKβα activation.

Hcy-induced endothelial dysfunction is manifested by increased oxidant stress and impaired endothelium-dependent vascular tone. Hcy activates MMP-9, in part, by decrease in nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability and an increase in vascular oxidant stress (Tyagi et al. 2005). AA after being liberated from the membrane is metabolized to vasoactive eicosanoids, including prostacyclin (PGI2) (Vane and Botting, 1995). A third mediator, known as endothelium derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF), presumably an EET, had an anti-atherosclerotic property similar to nitric oxide (Node et al. 1999; Fitzpatrick et al. 1986; Sun et al. 2002). Our study suggested that vascular endothelium-derived AA metabolites may modulate the vascular function in HHcy.

Hcy induced the AA release and increased the formation of thromboxane in platelets from HHcy human subjects (Signorello et al. 2002; Leoncini et al. 2006). The actions of thromboxane -vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation- opposed the effects of PGI2. CYP2J2, highly expressed in vascular endothelial cells, activates the epoxidation of AA to EETs (Node et al. 1999; Wu et al. 1996). By using the physiological dose of EETs (1-3 μM), we showed that the exogenous addition of 8,9-EET but not the 11,12-EET significantly ablated Hcy-induced MMP-9 indicating the differential bioactivity of specific EET regioisomers. Of interest, Node et al. (1999), while studying the anti-inflammatory properties of CYP2J2-derived EETs in cultured BAEC, noticed differential bioactivity of EETs which was attributed to the different cell type, culture conditions, and the treatment regimes.

Yang et al. (2001), observed a decrease in CYP2J2 protein levels in hypoxia-associated cellular injury and demonstrated that CYP2J2 transfection in BAECs was cytoprotective against hypoxia. There was a significant reduction in CYP2J2 protein by Hcy in a dose dependent manner. Importantly, P450 epoxygenase transfection significantly attenuated Hcy-induced MMP-9 expression and activity. These observations accentuated the importance of CYP and its AA metabolites in the modulation of Hcy/MMP-9 signal.

CYP-derived EETs are signal transduction molecules which exert different effects on a variety of cell types including activation of kinase cascades and the modulation of gene expression. Wang et al. (2005) demonstrated that EETs mediate angiogenic effects and suggested the involvement of MAPK/ERK and PI3-kinase/AKT signal (Michaelis and Fleming, 2006). Recently, we showed that Hcy mediated an increase in MMP-9 activation and expression and suggested the involvement of MAPK/ERK signal in endothelial cells (Moshal et al. 2006). Although the phosphorylation of PI3K-dependent AKT signal has been suggested in MMP-9 induction (Wang et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2006), we presumed that the decrease in endogenous CYP levels with the consequent effects occurred downstream of the activation of MAPK/ERK signal pathway. Experiments with PI3-kinase/AKT inhibitor (wortmannin) and activator (sodium peroxyvandate) in HHcy, suggested the involvement of PI3-kinase in Hcy/MMP-9 signal axis. Furthermore, we observed a time- and concentration-dependent dephosphorylation of PI3K-dependent AKT with Hcy. Similarly, Zhu et al. (2006), Zhang et al. (2005), and Suhara et al. (2004) observed the Hcy-induced AKT dephosphorylation in cultured endothelial cells in different experimental settings.

Notably, the CYP epoxygenase transfection or addition of 8,9-EET in HHcy led to AKT phosphorylation to the levels which approximated those in the control groups. Similarly, Wang et al. (2005) showed that the angiogenic effects of CYP2J2-derived EETs were mediated by activation of PI3-kinase/AKT signal in BAECs (Michaelis and Fleming, 2006). Exactly, how the CYP-derived EETs can elicit the activation of AKT remains unclear. Although an extracellular EET receptor has been proposed on guinea pig monocytes (Wong et al. 2000) and rat aortic smooth muscle cells (Synder et al. 2002), there has been no report of such receptor in endothelial cells.

Hcy induces inflammatory responses by the activation of NF-κβ and the MMP-9 is a known target of NF-κβ activation. Notably, in our experimental setting of HHcy, the use of an NF-κβ blocking peptide suggested that indeed Hcy-induced MMP-9 activation was through NF-κβ -activation. In addition, NF-κβ activation by Hcy was concentration-dependent and involved the reduction IKβα levels. Although the phosphorylation of IKβα is also important in NF-κβ activation, in the present study only expression levels of IKβα were measured. Wang et al. (2000) reported a similar mechanism of NF-κβ activation in Hcy-treated vascular smooth muscle cells. However, CYP2J2-derived EETs modulate Hcy-induced MMP-9 via NF-κβ mechanism remains unknown, we suggested that CYP epoxygenase transfection or the administration of 8,9-EET ablated Hcy-induced NF-κβ activation and involved IKβα activation. These observations are in harmony with Node et al. (1999) who observed that the exogenous administration of EETs or CYP2J2 overexpression decreased the cytokine-induced endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression by a mechanism involving inhibition of NF-κβ and the activation of IKβα.

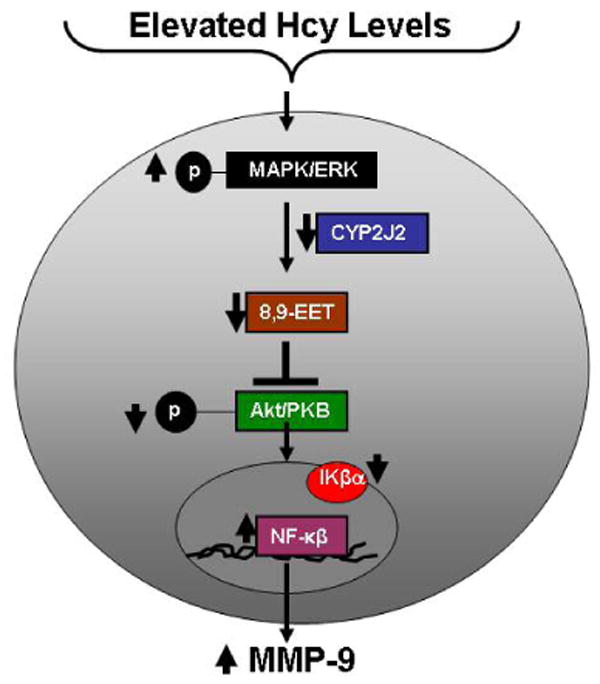

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that the Hcy treatment attenuated CYP2J2 protein levels and activated MMP-9, a process which involved dephosphorylation of PI3K-dependent AKT signal and an NF-κβ-dependent mechanism (Figure 10). Furthermore, the P450 epoxygenase transfection or 8,9-EET supplementation phosphorylated AKT and attenuated Hcy-induced MMP-9, in part, by inhibition of NF-κβ and IKβα activation. Thus our findings highlighted the understanding of molecular mechanisms for MMP-9 regulation in HHcy, and specifically proposed a role for CYP epoxygenase and its AA metabolites in the modulation of Hcy/MMP-9 signal. This information may be helpful in developing a novel therapeutic approach to HHcy-associated vascular dysfunction.

Figure 10.

A schematic representation of the modulation of Hcy/MMP-9 signal by P450 epoxygenase. Hcy downregulates CYP2J2 expression, attenuates PI3K-dependent AKT phosphorylation, causes nuclear accumulation of NF-κβ leading to MMP-9 induction.

Acknowledgments

The study is supported, in part, by American Heart Association Post-Doctoral training grant (award # 0625579B) (to Karni S. Moshal), Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (to Darryl C. Zeldin), NIH Grant HL-74185 S (to Walter E. Rodriguez), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-71010, HL-74185, and HL-88012 (to Suresh C. Tyagi).

References

- Creemers EEJM, Cleuthens JPM, Smits JFM, Daemen MJAP. Matrix metalloproteinase after myocardial infarction a new approach to prevent heart failure. Circ Res. 2001;89:201–210. doi: 10.1161/hh1501.094396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick FA, Ennis MD, Baze ME, Wynalda MA, McGee JE, Liggett WF. Inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase activity and platelet aggregation by epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Influence of stereochemistry. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:15334–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Michaelis UR, Kiss L, Popp R, Busse R. The coronary endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) stimulates multiple signalling pathways and proliferation in vascular cells. Pflugers Arch. 2001;442(4):511–8. doi: 10.1007/s004240100565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galis ZS, Khatri JJ. Matrix metalloproteinases in vascular remodeling and atherogenesis: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Circ Res. 2002;90(3):251–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann MA, Lalla E, Lu Y, Gleason MR, Wolf BM, Tanji N, Ferran LJ, Jr, Kohl B, Rao V, Kisiel W, Stern DM, Schmidt AM. Hyperhomocysteinaemia enhances vascular inflammation and accelerates atherosclerosis in a murine model. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:675–683. doi: 10.1172/JCI10588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko HM, Kang JH, Choi JH, Park SJ, Bai S, Im SY. Platelet-activating factor induces matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression through Ca 2+ - or PI3K-dependent signaling pathway in a human vascular endothelial cell line. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(28):6451–6458. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SD, Wu CC, Chang YC, Chang SH, Wu CH, Wu JP, Hwang JM, Kuo WW, Liu JY, Huang CY. Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced cellular hypertrophy and MMP-9 activity via different signaling pathways in H9c2 cardiomyoblast cells. J Periodontol. 2006;77(4):684–91. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leoncini G, Bruzzese D, Signorello MG. Activation of p38 MAPKinase/cPLA2 pathway in homocysteine-treated platelets. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(1):209–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Qu W, Scarborough PE, Tomer KB, Moomaw CR, Maronpot R, Davis LS, Breyer MD, Zeldin DC. Molecular cloning, enzymatic characterization, developmental expression, and cellular localization of a mouse cytochrome P450 highly expressed in kidney. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(25):17777–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCully KS. Homocysteine and vascular disease. Nat Med. 1996;2(4):386–389. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis UR, Fisslthaler B, Barbosa-Sicard E, Falck JR, Fleming I, Busse R. Cytochrome P450 epoxygenases 2C8 and 2C9 are implicated in hypoxia-induced endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5489–98. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A, Mujumdar V, Shek E, Guillot J, Angelo M, Palmer L, Tyagi SC. Hyperhomocyst(e)inemia induces multiorgan damage. Heart Vessels. 2000;15:135–143. doi: 10.1007/s003800070030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A, Mujumdar V, Palmer L, Bower JD, Tyagi SC. Reversal of endocardial endothelial dysfunction by folic acid in homocysteinemic hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis UR, Fleming I. From endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) to angiogenesis: Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) and cell signaling. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111(3):584–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshal KS, Tyagi N, Henderson B, Ovechkin AV, Tyagi SC. Protease-activated receptor and endothelial-myocyte uncoupling in chronic heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288(6):H2770–H2777. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01146.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshal KS, Sen U, Tyagi N, Henderson B, Steed M, Ovechkin AV, Tyagi SC. Regulation of homocysteine-induced MMP-9 by ERK1/2 pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290(3):C883–C891. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00359.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshal KS, Singh M, Sen U, Rosenberger DS, Henderson BC, Tyagi N, Zhang H, Tyagi SC. Homocysteine-mediated activation and mitochondrial translocation of calpain regulates MMP-9 in MVEC. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291(1):H2825–H2835. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00377.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Node K, Huo Y, Ruan X, Yang B, Spiecker M, Ley K, Zeldin DC, Liao JK. Anti-inflammatory properties of cytochrome P450 epoxygenase-derived eicosanoids. Science. 1999;285(5431):1276–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip S, Kundu GC. Osteopontin induces nuclear factor kappa B-mediated promatrix metalloproteinase-2 activation through I kappa B alpha /IKK signaling pathways, and curcumin (diferulolylmethane) down-regulates these pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(16):14487–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207309200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signorello MG, Pascale R, Leoncini G. Effect of homocysteine on arachidonic acid release in human platelets. Eur J Clin Invest 2002. 2002;32(4):279–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2002.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder GD, Krishna UM, Falck JR, Spector AA. Evidence for a membrane site of action for 14,15-EET on expression of aromatase in vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:H1936–H1942. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00321.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solini A, Santini E, Nannipieri M, Ferrannini E. High glucose and homocysteine synergistically affect the metalloproteinases-tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases pattern, but not TGFB expression, in human fibroblasts. Diabetologia. 2006;49(10):2499–506. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0377-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinale FG. Matrix metalloproteinases regulation and dysregulation in the failing heart. Circ Res. 2002;90:520–530. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000013290.12884.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhara T, Fukuo K, Yasuda O, Tsubakimoto M, Takemura Y, Kawamoto H, Yokoi T, Mogi M, Kaimoto T, Ogihara T. Homocysteine enhances endothelial apoptosis via upregulation of Fas-mediated pathways. Hypertension. 2004;43(6):1208–13. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000127914.94292.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Sui X, Bradbury JA, Zeldin DC, Conte MS, Liao JK. Inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell migration by cytochrome P450 epoxygenase-derived eicosanoids. Circ Res. 2002;90:1020–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000017727.35930.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi N, Sedoris KC, Steed M, Ovechkin AV, Moshal KS, Tyagi SC. Mechanisms of homocysteine-induced oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289(6):H2649–H2656. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00548.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungvari Z, Csiszar A, Bagi Z, Koller A. Impaired nitric oxide-mediated flow induced coronary dilation in hyperhomocysteinemia: morphological and functional evidence for increased peroxynitrite formation. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:145–153. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64166-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vane JR, Botting RM. Pharmacodynamic profile of prostacyclin. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:3A–10A. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Siow YL, O K. Homocysteine stimulates nuclear factor kappaB activity and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in vascular smooth-muscle cells: a possible role for protein kinase C. Biochem J. 2000;352:817–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zhang ZG, Zhang RL, Gregg SR, Hozeska-Solgot A, LeTourneau Y, Wang Y, Chopp M. Matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) and MMP-9 secreted by erythropoietin-activated endothelial cells promote neural progenitor cell migration. J Neurosci. 2006;26(22):5996–6003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5380-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wei X, Xiao X, Hui R, Card JW, Carey MA, Wang DW, Zeldin DC. Arachidonic acid epoxygenase metabolites stimulate endothelial cell growth and angiogenesis via mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314(2):522–32. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.083477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong PY, Lai PS, Falck JR. Mechanism and signal transduction of 14 (R), 15 (S)- epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (14,15-EET) binding in guinea pig monocytes. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2000;62:321–333. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(00)00079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Chen W, Murphy E, Gabel S, Tomer KB, Foley J, Steenbergen C, Falck JR, Moomaw CR, Zeldin DC. Molecular cloning and expression of CYP2J2, a human cytochrome P450 arachidonic acid epoxygenase highly expressed in heart myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3460–3468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Graham L, Dikalov S, Mason RP, Falck JR, Liao JK, Zeldin DC. Overexpression of cytochrome P450 CYP2J2 protects against hypoxia-reoxygenation injury in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60(2):310–320. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HS, Cao EH, Qin JF. Homocysteine induces cell cycle G1 arrest in endothelial cells through the PI3K/Akt/FOXO signaling pathway. Pharmacology. 2005;74(2):57–64. doi: 10.1159/000083684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JH, Chen JZ, Wang XX, Xie XD, Sun J, Zhang FR. Homocysteine accelerates senescence and reduces proliferation of endothelial progenitor cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40(5):648–52. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]