Abstract

We examined interactions between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperones calnexin (CN), ERp57, and immunological heavy chain-binding protein (BiP) and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) subunits. The three chaperones rapidly associate with newly synthesized nAChR subunits. Interactions between nAChR subunits and ERp57 occur via transient intermolecular disulfide bonds and do not require subunit N-linked glycosylation. The associations of ERp57 or CN with AChR subunits are long lived and prolong subunit lifetime ∼10-fold. Co-expression of CN or ERp57 alone does not affect nAChR assembly or trafficking, but together they cause a significant decrease in nAChR expression and assembly. In contrast, associations with BiP are shorter lived and do not alter nAChR expression and assembly. However, a mutated BiP that slows its dissociation significantly increases its associations and decreases nAChR expression and assembly. Our results suggest that interactions with the chaperones regulate the levels of nAChRs assembled in the ER by stabilizing and sequestering subunits during assembly.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER)2 is highly specialized to promote and regulate the synthesis and maturation of membrane and secreted proteins. These processes are dependent on quality ER control mechanisms that identify and degrade misfolded proteins. Components of the ER quality control machinery are molecular chaperones (for reviews, see Refs. 1 and 2). Recent studies have identified protein domains and processing events that mediate interactions between ER chaperones and their substrates (3). Less is known about chaperone-substrate dynamics after the interaction is established.

Here, we examine interactions between nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) subunits and the ER chaperones, calnexin (CN), ERp57, and immunological heavy chain-binding protein (BiP). CN is a type I membrane protein that interacts directly with N-linked glycan (4) and/or with polypeptide domains (5–7). CN is found in a complex with ERp57, a member of the protein-disulfide isomerase superfamily that catalyzes the formation of intramolecular disulfide bonds in nascent proteins. ERp57 has been shown to specifically recognize only trimmed glycoproteins (8–10). However, the lectin specificity of ERp57 may be a result of its association with CN rather than an intrinsic ERp57 lectin domain (11–13), which suggests cooperativity between CN and ERp57. Meanwhile, BiP function occurs via ATP-driven cycles of binding to and release of substrate proteins, which appears to promote protein folding by maintaining a state competent for folding by preventing aggregation (14). Release of substrate requires ATP hydrolysis by the BiP ATPase (15), and ATPase mutations block substrate release (16). BiP plays a variety of additional roles in the ER, including the translocation of newly synthesized proteins across the ER membrane (17, 18) and a role in proteasome degradation (19, 20).

In this study, we have characterized how interactions between the ER chaperones and muscle nAChR subunits affect subunit stability and nAChR assembly and expression. The muscle nAChR is composed of four homologous subunits, α, β, γ (or ∊), and δ, that assemble into α2βγδ pentamers. nAChR assembly occurs in the ER (21–24) and is both slow, (τ > 90 min) and inefficient, with only ∼30% of the synthesized α subunits correctly assembled into mature AChRs (25, 26). All three chaperones have been found to associate with unassembled subunits. CN associates with all four unassembled subunits (7, 24, 27), ERp57 associates with unassembled δ subunits (28), and BiP associates with unassembled α subunits (29–31). To examine the role of CN, ERp57, and BiP during the assembly of the AChR subunits, we used the AChR subunits from Torpedo californica. The advantages of the Torpedo subunits are that there are antibodies (Abs) that recognize all four Torpedo subunits, the Torpedo subunits are less prone to proteolysis after solubilization, and their assembly is temperature-dependent, which slows the assembly significantly and allows it to be synchronized (32). Using Torpedo nAChR subunits, we found that ERp57 and BiP, like CN, associate with newly synthesized AChR subunits but not with subunits during the later stages of assembly. Although an association with ERp57 or CN significantly increased subunit half-life, there was no change in the levels of nAChRs assembled or expressed at the cell surface. However, CN and ERp57 together or a BiP ATPase mutant decreased nAChR assembly and expression. Our data suggest that these chaperones can regulate levels of AChRs by stabilizing and sequestering subunits during the process of assembly in the ER.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Tissue Culture

The primary cell line used for transient transfection experiments was the tsA201 cell line, a human embryonic kidney cell line derived from HEK293 cells (33). Cells were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% calf serum.

Epitope Tagging of ERp57 and CN

A hemagglutinin (HA) tag was added to ERp57 cDNA 4 amino acids 3′ of the N-terminal signal sequence cleavage site. The creation of the ERp57-HA construct was carried out by site-directed insertion using two rounds of overlap extension PCR as described (34). Briefly, the first round of PCR involved using a standard pRBG4 vector forward primer or reverse primer and a complementary ERp57-specific primer that encoded 1) 21−24 base pairs of the HA epitope tag and 2) 20−22 base pairs of ERp57. The ERp57 primers used were a forward primer (5′-TAC GAC GTC CCA GAC TAC GCT GAA CTC ACG GAC GAC AAC TTC G-3′) and a reverse primer (5′-GTA GTC TGG GAC GTC GTA TGG GTA TAG CAC GTC GGA GGC AGC GG-3′), where the underlined base pairs represent the HA epitope tag. The two first round PCR products were gel-purified and combined together. Regions of the ERp57-HA cDNA created by PCR methods were sequenced to control for errors in the PCR products using the Sequenase 2.0 dideoxy sequencing kit (Amersham Biosciences). A FLAG tag was added to CN by replacing the HA tag. The epitope tag swap was made using the CN-HA as the template. The creation of the CN-FLAG construct was carried out as described above for ERp57-HA. Briefly, the first round of PCR used a standard pREP8 forward primer or reverse primer along with a complementary CN-specific primer that encoded 1) a 21-base pair piece of the FLAG tag and 2) a 23−27-base pair piece of CN immediately 5′ or 3′ to the HA tag. The CN-specific primers used are a forward primer (5′-TAC AAG GAC GAT GAT GAC AAG CAA GAG GAG GAC GAT AGG AAA CC-3′) and a reverse primer (5′-GTC ATC ATC GTC CTT GTA GTC ACT GGC AGT GCC GCC ATC TTC TTC AGC-3′), where the underlined base pairs are the FLAG epitope tag.

Transient Transfection

The chaperones, Torpedo and mouse AChR subunit cDNAs, were transiently transfected into 6-cm cultures of tsA201 cells (33) using a calcium phosphate method (35). When testing for associations between single AChR subunits and chaperones, amounts of cDNAs used were 4 μg of chaperone along with either 1 μg of α or 2 μg of β, γ, or δ. When testing for the effect of a chaperone on cell surface or intracellular expression Torpedo AChR expression, we transfected cells with 1 μg of α, 0.5 μg of β, 2.5 μg of γ, and 7.5 μg of δ subunit cDNAs along with varying amounts of empty vector, ERp57-HA, CN-HA, BiP-HA, T37G-HA, or CN-HA and ERp57-HA together. When testing for the effect of a chaperone on mouse AChR expression, we transfected the cells with 5 μg of α and 2.5 μg each of β, ∊ (or γ), and δ subunit along with 10 μg of CN-HA, ERp57-HA, or empty vector or 5 μg each of CN-HA and ERp57-HA.

Metabolic Labeling, Solubilization, and Subunit Immunoprecipitations

To metabolically label cells transiently expressing AChR subunits and chaperones, cultures in 6-cm plates were labeled as described previously (32, 36, 37). Briefly, the cultures were starved in methionine/cysteine-free DMEM for 15 min. The cultures were then pulse-labeled for 5 min at 37 °C in methionine/cysteine-free DMEM supplemented with 111 μCi of a [35S]methionine/[35S]cysteine mixture ([35S]Met/Cys; NEN EXPE35S35S). The labeling was stopped with the addition of DMEM plus 5 mm methionine and cysteine and, if not chased, washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline plus 0.01% Ca2+. The cells were solubilized in lysis buffer composed of 150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris, 1 mm CaCl2, pH 7.4, 2 mm N-ethylmaleimide, and 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride plus 0.02% NaN3, 1.83 mg/ml phosphatidylcholine, and 1% Lubrol (LPC). 20 mm N-ethylmaleimide was added to the LPC when solubilizing the DTT-treated cells to prevent formation of nonspecific disulfide bonds after solubilization. Following the label, the cells were washed three times with PBS and solubilized with 1% LPC. If the cells were chased following the label, the cells were harvested and pelleted at 1000 × g for 15 s. Cells were resuspended and washed in DMEM plus 10% CS supplemented with 5 mm methionine, pelleted, and resuspended in DMEM, 10% CS, 50 mm HEPES, 5 mm methionine. Suspended cells were divided into seven equal volumes and chased in suspension while rotating at 37 °C. After the chase, samples were pelleted, washed three times with PBS, and solubilized with 1% LPC. The cell lysates were then split into two equal aliquots and immunoprecipitated with either a subunit-specific or an anti-HA-specific Ab that quantitatively precipitates ERp57-HA (data not shown). The immunoprecipitations were Protein G-Sepharose-purified, washed three times, run on reducing gels (with DTT, unless otherwise noted), fixed, treated for 30 min with Amplify (Amersham Biosciences) to enhance the signal, dried on a gel dryer, and exposed to film at −80 °C with an intensifying screen. The intensity of a subunit band was quantified using a Typhoon 8600 PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences). Gels were exposed to a special phosphorimaging screen and scanned using the PhosphorImager. The band intensities were quantified using the ImageQuant software supplied by the manufacturer. We also performed densitometry using a computing densitometer (Amersham Biosciences) and quantified band intensities using the ImageQuant software. Three to five exposures of the autoradiograph were scanned to ensure that the band intensities were within the linearity of the film.

Western Blot

To determine the increase in chaperone expression because of transient expression, 6-cm plates of tsA201 cells were either sham-transfected or transfected with 4 μg of chaperone cDNA. The samples were then trichloroacetic acid-precipitated to determine the transient increase of chaperone expression. All samples were separated using 7.5% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose for Western blot analysis. Western blots were probed with anti-ERp57 Ab (Fig. 1A; Stressgen; 1:2000 dilution) or anti-KDEL (Fig. 2, A and D; Stressgen; 1:1000 dilution), and the blots were developed by ECL (Amersham Biosciences). Band intensities were quantified by scanning 3−5 exposures to ensure the linearity of the band intensities using the computing densitometer (Amersham Biosciences).

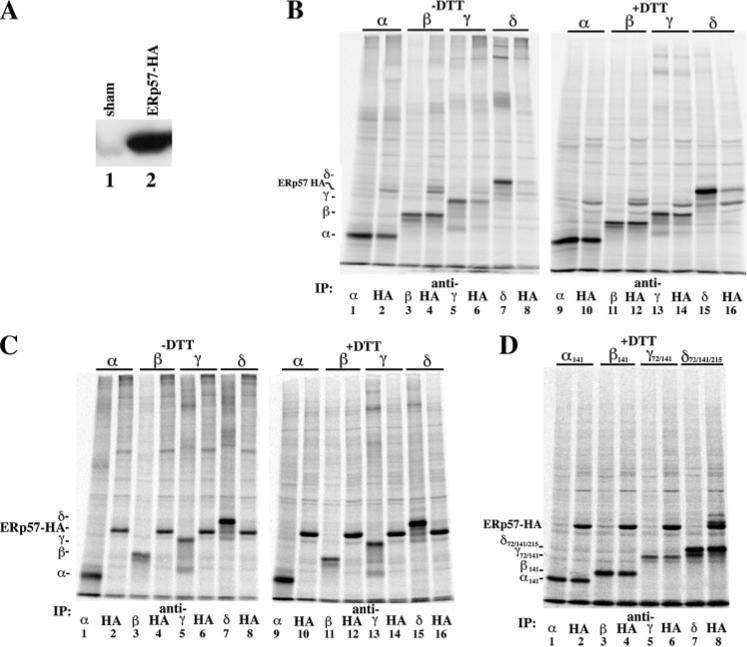

FIGURE 1. AChR subunits associate with ERp57.

A, effect of transient expression of ERp57-HA on total ERp57 protein. Western blots were overlaid with anti-ERp57 Ab. In lane 1, total cell lysate from a 6-cm plate of tSA201 cells was trichloroacetic acid-precipitated. In lane 2, total cell lysate was prepared as in lane 1, except that the cells were transiently transfected with 4 μg of ERp57-HA cDNA. B, cells transiently expressing ERp57-HA along with one of the four AChR subunits were [35S]Met/Cys-pulse-labeled. Labeled lysates were split into two equal aliquots and immunoprecipitated (IP) with either a subunit-specific Ab (odd numbered lanes) or an anti-HA Ab (even numbered lanes). When the samples were reduced with DTT prior to running the SDS-PAGE (+DTT gel; lanes 9−16), the aggregated material at the top of the –DTT lanes was reduced, causing an increase in intensity of the subunit and chaperone bands. C, cells transiently expressing either ERp57-HA or one of the four AChR subunits were [35S]Met/Cys-pulse-labeled. Samples were treated as in B. Gels were run under both nonreduced (–DTT gel, lanes 1−8) and reduced (+DTT gel, lanes 9−16). D, cells transiently expressing ERp57-HA along with one of the four mutant nonglycosylated AChR subunits were [35S]Met/Cys-pulse-labeled. Samples were treated as in B.

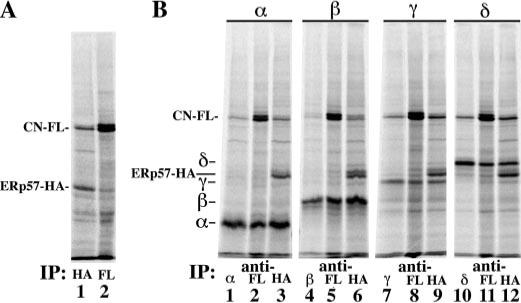

FIGURE 2. AChR subunits associate with ERp57-CN complexes.

A, cells transiently coexpressing ERp57-HA and CN-FLAG were [35S]Met/Cys-pulse-labeled. Labeled lysates were split into two equal aliquots, immunoprecipitated (IP) with either an anti-HA Ab (lane 1) or an anti-FLAG M2 Ab (lane 2), and run under reducing conditions. B, cells transiently coexpressing ERp57-HA, CN-FLAG, and a single AChR subunit were [35S]Met/Cys-pulse-labeled (n = 3−5 per subunit). Labeled lysates were split into three equal aliquots and were immunoprecipitated with a subunit-specific Ab (lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10), an anti-FLAG monoclonal Ab (lanes 2, 5, 8, and 11), or an anti-HA Ab (lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12).

125I-Bgt Binding

To measure cell surface 125I-Bgt binding of transiently transfected Torpedo αβγδ, tsA201 cells were shifted from 37 to 20 °C 24 h after the transfection. Cultures were grown for 4 days after transfection at 20 °C for maximal surface AChR expression. To measure cell surface 125I-Bgt binding of transiently transfected mouse αβγδ, tsA201 cells were maintained at 37 °C for 48 h after the transfection. The cultures were then washed with PBS and incubated at room temperature in PBS containing 4 nm 125I-Bgt (140−170 cpm/fmol) for 2 h, which results in saturation of binding. Cultures were washed again in PBS, and the cell surface counts were determined by γ-counting. Intracellular 125I-Bgt binding was measured by preincubating the cells in excess cold Bgt prior to solubilization. Total cell 125I-Bgt binding was measured after cells were solubilized with 1% LPC. Appropriate Abs along with 10 nm 125I-Bgt were added to the cell lysates and incubated at 4 °C overnight to saturate binding at this lower temperature, followed by Protein G-Sepharose purification.

RESULTS

AChR Subunits Associate with ERp57

We previously had characterized interactions between CN and nAChR subunits and found that CN rapidly associates with each nAChR subunit, but the interactions did not depend on subunit N-linked glycosylation (7). In this study, we performed a similar set of experiments to characterize interactions between ERp57 and nAChR subunits. An HA epitope tag was fused to the N terminus of ERp57, which allowed quantitative immunoprecipitation of ERp57, which was not achieved with commercially available Abs (data not shown). Transient expression of ERp57-HA resulted in a ∼100-fold increase (n = 5) of ERp57 in human embryonic kidney cells (Fig. 1A, compare lanes 1 and 2). Each Torpedo nAChR subunit cDNA (α, β, γ, or δ) was transfected with the ERp57-HA cDNA, and cells were briefly metabolically labeled with [35S]Met/Cys. To determine the percentage of nAChR subunit complexed with ERp57-HA, the amount of labeled subunit co-immunoprecipitated with an anti-HA Ab (Fig. 1B, lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) was compared with the total amount of subunit synthesis as assayed by immunoprecipitation with subunit-specific Abs (Fig. 1B, lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7). Each nAChR subunit was found to coprecipitate with ERp57-HA to varying degrees. When we quantified subunit band intensities, we observed that 69 ± 5% of α, 98 ± 7% of β, 59 ± 7% of γ, and 19 ± 1% of δ (n = 5−7 ± S.E. for each subunit) subunits associate with the ERp57-HA during the 5-min pulse labeling. ERp57, thus, rapidly associates with each of the Torpedo nAChR subunits, similar to what we had observed with CN (7).

ERp57 is a disulfide isomerase that can associate with nascent proteins via transient intermolecular disulfide bonds (10). Consistent with transient disulfide bonds forming between the nAChR subunits and ERp57, we observed that the nAChR subunit and ERp57 band intensities were less on nonreducing SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1B, –DTT) compared with SDS-PAGE prepared with DTT (Fig. 1B, +DTT). This finding suggested that disulfide-bonded ERp57-subunit complexes formed and existed on nonreducing gels and were lost after reduction. 35S-Labeled bands were present on the nonreducing gels, but their identification was ambiguous because of other labeled proteins that co-precipitate with ERp57. Subunit band intensities increased with DTT reduction, and the percentage of subunits co-precipitating with ERp57-HA did not change, consistent with ERp57-subunit disulfide-bonded complexes. N-ethylmaleimide has been used as a rapidly acting alkylating agent of cysteines (38) that prevents postlysis oxidation of free cysteines. To address whether the disulfide bonds formed after cell solubilization, we tested whether solubilization in 2 or 20 mm N-ethylmaleimide decreased the percentage of observed association. We observed no change in the subunit band intensities after co-immunoprecipitation with ERp57 whether the sample was reduced or not (data not shown). As a second test, separate cell cultures expressing either ERp57-HA or individual subunits were [35S]Met/Cys-labeled, cell lysates were mixed, and the same immunoprecipitations were performed (Fig. 1C). When ERp57-HA and nAChR subunits were expressed in separate cell cultures, we did not observe any subunit co-immunoprecipitating with ERp57-HA under either reduced (+DTT) or nonreduced (–DTT) conditions (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that association and disulfide bonds between ERp57 and nAChR subunits occur only within the environment of the ER and are the result of specific intermolecular bonds between ERp57 and a subunit.

Associations between ERp57 and substrate proteins can be dependent on the presence of N-linked glycans similar to what is observed with CN. This dependence may result from an association with CN rather than a specific lectin recognition domain on ERp57 (11). Because we previously found that CN-AChR subunit interactions are independent of the N-linked glycosylation (7), we examined whether ERp57 would interact with nonglycosylated AChR subunits mutated to remove the N-glycosylation consensus sequences. Using the same [35S]Met/Cys labeling protocol on cells co-expressing ERp57-HA and the mutated nAChR subunits, we found a similar degree of association between ERp57-HA and the subunits (Fig. 1D). However, the δ subunit mutant associates with ERp57-HA much more strongly than the wild type δ subunit (compare intensities in Fig. 1, D (lanes 7 and 8) with B (lanes 15 and 16)). The finding that nonglycosylated subunit mutants associate with ERp57-HA is consistent with our results that demonstrate AChR subunits associate with CN in a lectin-independent manner (7). We cannot rule out the possibility that ERp57 is associating nonspecifically with the α, γ, and δ nonglycosylation subunit mutants, because these mutants do not support AChR assembly (7, 39).

AChR Subunits Associate with ERp57-CN Complexes

Because ERp57 and CN are found as a complex (40), we tested whether co-expression of the two had effects different from when each is expressed individually with the subunits (Fig. 2). We substituted the HA epitope tag on CN with a FLAG epitope tag in order to separately immunoprecipitate each chaperone. When ERp57-HA was co-expressed along with CN-FLAG and [35S]Met/Cys-pulse-labeled, we found that the chaperones co-immunoprecipitated each other (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 2), indicating that ERp57 and CN are part of the same chaperone complex. When ERp57-HA and CN-FLAG were co-expressed with a single AChR subunit and [35S]Met/Cys-pulse-labeled, each of the subunits was coprecipitated with CN-FLAG (Fig. 2B, lanes 2, 5, 8, and 11) and ERp57-HA (Fig. 2B, lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12). Approximately equal amounts of subunit are coimmunoprecipitated with each chaperone. In addition, the presence of both CN-FLAG and ERp57-HA significantly increased the association between δ and ERp57 (from 19 to 69%), whereas it increased the association between β and CN-FLAG (from 56 to 100%). The presence of ERp57 and CN also increased the associations between the γ subunit and CN or ERp57 (from ∼60 to ∼80% for both). These results suggest that ERp57 and CN are part of the same chaperone complex, and they operate in tandem when associating with AChR subunits.

AChR Subunit Associations with BiP

Previous studies have found that the unassembled α subunit associates with BiP (29–31). To determine if the other subunits associate with BiP, we performed a similar set of experiments characterizing the association of BiP with AChR subunits as with ERp57 (Fig. 3). Again, we used an HA-tagged construct (BiP-HA) (41) to look at associations between BiP and AChR subunits because of problems quantitatively precipitating endogenous BiP (data not shown). In contrast to ERp57-HA, transfection of BiP-HA resulted in only a ∼35% increase (n = 4) of BiP expression (Fig. 3A). We were able to assay synthesis of both transfected and endogenous BiP, because the addition of the HA epitope altered the migration of transfected BiP on SDS-PAGE compared with the endogenous BiP. After transfection of BiP-HA, no labeled endogenous BiP was detectable. Thus, transfection of BiP-HA appeared to lower endogenous BiP synthesis, and the total levels of BiP only increased marginally.

FIGURE 3. AChR subunits associate with BiP.

A, to determine the increase of BiP-HA protein as a result of transient overexpression, Western blots were overlaid with anti-KDEL Ab. In lane 1, total cell lysate from a single 6-cm plate of tSA201 cells was trichloroacetic acid-precipitated (sham). In lane 2, total cell lysate was prepared as in lane 1, except that the cells were transiently transfected with 5 μg of BiP-HA cDNA. B, cells transiently transfected with 5 μg of BiP-HA cDNA along with one of the four AChR subunits were [35S]Met/Cys-pulse-labeled. Solubilized labeled lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with either a subunit-specific (odd numbered lanes) or anti-HA-specific Ab (even numbered lanes). C, cells transiently expressing either BiP-HA or one of the four AChR subunits were [35S]Met/Cys-pulse-labeled. Labeled BiP-HA lysates were then combined with the labeled single AChR subunit lysates. The combined cell lysates were then split into two equal aliquots and were immunoprecipitated with either a subunit-specific Ab (odd numbered lanes) or an anti-HA Ab (even numbered lanes). D, cells were transiently transfected with either the γ (lanes 1 and 2; n = 2) or δ (lanes 3 and 4; n = 2) nAChR subunit along with BiP-HA (lanes 1 and 3) or T37G-HA (lanes 2 and 4). The cells were solubilized and immunoprecipitated with a subunit-specific Ab. The blots were overlaid with an anti-HA-specific Ab and visualized. Controls were included to determine if the BiP-HA was specifically associated with the subunit; lane 5 was prepared from cells expressing only BiP-HA and immunopurified with the same subunit-specific Ab. Lane 6 is a control for both, where BiP-HA migrates on SDS-PAGE and for the immunoblot. E, identical to A, except T37G-HA cDNA was used instead of BiP-HA. F, identical to B, except T37G-HA cDNA was used in place of BiP-HA. G, identical to C, except T37G-HA cDNA was expressed instead of BiP-HA. H, cells transiently expressing the four Torpedo subunits along with 10 μg of vector, BiP-HA, or T37G-HA were solubilized 3 days after the shift to 20 °C. Intracellular Bgt counts were obtained by blocking cell surface AChRs with cold Bgt. The cells were then washed to remove excess unbound cold Bgt, solubilized, and split into six equal aliquots. 10 nm 125I-Bgt was added to each sample along with an α subunit-specific Ab to three aliquots and an anti-HA Ab to the other three. The intracellular Bgt binding fractions of the maximum values shown were calculated by dividing all 125I-Bgt counts by the number of 125I-Bgt counts in the α subunit-specific Ab-purified vector samples (n = 3; ±S.E.).

To examine which AChR subunits associate with BiP and levels of associations, cells transiently expressing each of the subunits were assayed using the using the same [35S]Met/Cys labeling protocol as above. Unassembled α and β subunits associated with BiP (Fig. 3B) but at levels less than what was observed for CN (7) and ERp57 (Fig. 1). Based on quantification of band intensities, we determined that 13% of α and 28% of β subunits associated with the BiP-HA. The BiP association with α and β subunits did not occur if each subunit and BiP were transfected in separate culture and mixed after solubilization (Fig. 3C). Our ability to assay for the co-precipitation of γ and δ subunits with BiP was limited by the co-precipitation of other proteins that migrated with and obscured γ and δ subunit bands on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3B), but the co-precipitation of γ and δ subunits was clearly less than that observed with the CN (7) and the co-precipitation of γ subunits with ERp57 (Fig. 1B). As an alternative, we used immunoblot analysis to assay for co-precipitation of γ or δ subunits with BiP-HA. Transfected cells were solubilized, and subunits were immunoprecipitated, separated on SDS-PAGE, and transferred to membranes for analysis. Anti-HA-specific Ab was used to blot for BiP-HA, and BiP clearly co-precipitated with γ (Fig. 3D, lane 1) and δ (Fig. 3D, lane 3) subunits.

Several experiments were performed to address why BiP generally associated less with the nAChR subunits than CN or ERp57. One possible reason could be that the interactions occur later during the assembly process than CN or ERp57. Much longer pulse label periods did not significantly increase co-precipitations of α or β subunits with BiP (data not shown). Furthermore, mature α subunits did not co-precipitate with BiP (Fig. 3H). To test whether the low levels of BiP-subunit associations were caused by shorter lived interactions, we altered the ATPase site of BiP, changing residue 37 from a threonine to a glycine (T37G BiP). The release of substrate from BiP is an ATPase-dependent process, and disrupting the ATPase activity slows the release of the subunits by BiP (42). Transfection of T37G-HA, as with BiP-HA, resulted in a 35% increase of total BiP (Fig. 3E). To determine the effect of the BiP ATPase mutation on associations with AChR subunits, cells transiently expressing each of the subunits were assayed as in Fig. 1B. ∼30% of α and ∼49% of β subunits associated with the T37G-HA, which is a significant increase compared with BiP-HA, consistent with the T37G-HA mutant binding to but releasing the subunits more slowly. Again, we also tested whether the interaction between nAChR subunits and T37G-HA occurred after solubilization of the cells. As with BiP-HA, we observed no co-precipitation of the AChR subunits with T37G-HA when the subunits and T37G-HA were solubilized from separate cultures (Fig. 3G). We again used immunoblot analysis to test whether T37G-HA interacts with γ and δ subunits, and we observed that ∼23% more of the γ and ∼20% more of the δ subunit was associated with T37G-HA as compared with BiP-HA (Fig. 3D, lanes 2 and 4). These results indicate that altering the ATPase site increases the amount of nAChR subunit associated with BiP. Together, our results suggest that BiP interacts with nAChR subunits by a different mechanism from that of CN and ERp57, which appear to stably bind the nAChR subunits. Instead, BiP binding appears to be shorter lived and may undergo cycles of binding and release as previously noted for its interaction with other substrates (16).

CN and ERp57 Slow Subunit ER-associated Degradation (ERAD)

To address how the interactions of CN and ERp57 affect nAChR subunits in the ER, we performed [35S]Met/Cys pulse analysis to assay subunit lifetimes. When nAChR subunits are expressed individually, they fail to assemble, are not trafficked to the plasma membrane, and are rapidly degraded by ERAD (26). Cells transiently transfected with Torpedo α subunits were [35S]Met/Cys-labeled for 5 min and chased for the times shown in Fig. 4A. Plotted in the figure are the α subunit band intensities as a function of time after the cells were labeled, and the decay of the signal is a measure of ERAD. ERAD of Torpedo α subunits is essentially fit by single exponential decay, as shown by the line through the data points and in this case has a decay constant (τ) of 55 min. This is consistent with previous measurements of the turnover of single nAChR subunits, where the data were well fit by single exponentials with τ values of ∼40 min (43–45). Similar results (Table 1) were obtained for the degradation of β, γ, and δ subunits when transfected individually and assayed using the same protocol.

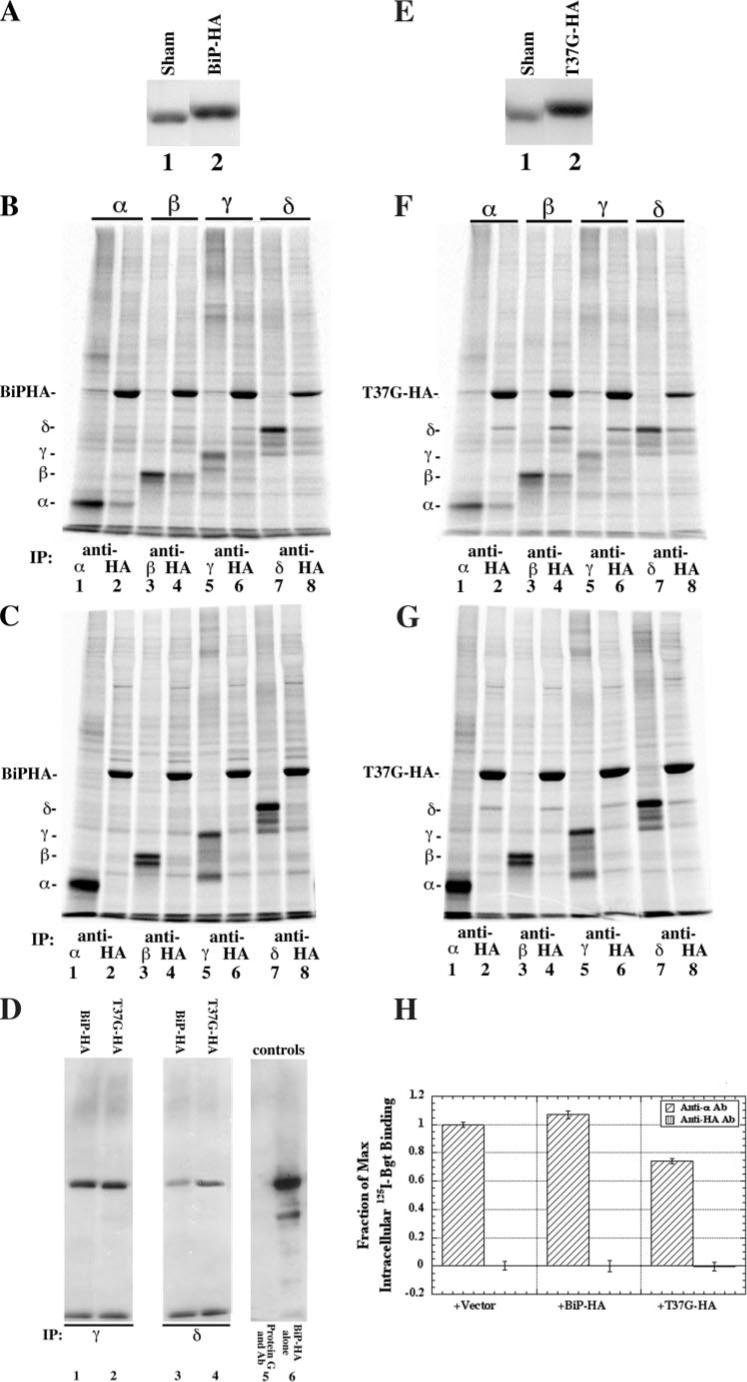

FIGURE 4. CN and ERp57 slow subunit subunit-associated degradation.

A and B, cells transiently expressing the α AChR subunit either alone (A) (n = 2) or along with CN-HA (B) (open triangles, n = 5), ERp57-HA (B) (open circles, n = 3), or both CN-FLAG and ERp57-HA (B) (open diamonds, n = 2) were [35S]Met/Cys-pulse-labeled and chased for the indicated times. The labeled cells were solubilized and immunoprecipitated with an α subunit-specific Ab. The data were obtained from quantified gel bands, and the percentage of subunit present at each time point was calculated by dividing the measured values at each time point by the 0 min subunit-specific immunoprecipitation value from each transfection. The α alone data were best fit with a single exponential, whereas the other data were best fit using a double exponential to determine the τ of the subunit. C–F, cells transiently coexpressing CN-HA and one of the AChR subunits (C, α (n = 5; ±S.E.); D, β (n = 3; ±S.E.); E, γ (n = 3; ±S.E.); F, δ (n = 4; ± S.E.)) were [35S]Met/Cys-pulse-labeled and chased for the indicated times. Labeled cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with either a subunit-specific Ab (open squares) or an HA-specific Ab (open circles). Data were calculated as in A (see Table 1).

TABLE 1. AChR subunit ERAD slowed by long lived chaperone associations.

Values were calculated from the Fig. 4 plots. Briefly, the percentage of subunit present at each time point in the Fig. 4 plots was calculated by dividing measured values at each time point by the 0 min value from the subunit-specific immunoprecipitation. The data were fit to determine the τ of the AChR subunit alone or in the presence of CN-HA, ERp57-HA, or both. ND, not determined.

| α subunit | β subunit | γ subunit | δ subunit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| min | min | min | min | |

| Control | 55 | 51 | 73 | 69 |

| +CN-HA | Fast = 50 | Fast = 40 | Fast = 40 | Fast = 5 |

| Slow = 600 | Slow = 480 | Slow = 380 | Slow = 250 | |

| + ERp57-HA | Fast = 10 | ND | ND | ND |

| Slow = 270 | ||||

| +CN-HA and ERp57-HA | Fast = 20 | ND | ND | ND |

| Slow = 800 |

Co-expression of CN, ERp57, or the two together with Torpedo α subunits alters the time course of subunit degradation, and the data from pulse-chase analysis are no longer well fit by single exponential functions (Fig. 4B and Table 1). With the addition of CN to α subunit expression, we observed two different rates of α subunit degradation: a fast rate that is comparable with that observed in the absence of CN (τ = 50 min) and a rate about 10-fold slower (τ = 600 min). With the addition of ERp57 instead of CN, again we observed two different rates of α subunit degradation: a fast rate (τ = 10 min) and a much slower rate (τ = 270 min). The fast rate obtained with ERp57 appears to be significantly faster than the rates observed in the absence of either chaperone. With co-expression of both CN and ERp57, the fast rate of degradation was similar to what was observed with ERp57 (τ = 20 min), whereas the slow rate was similar to what was observed with CN (τ = 800 min).

To further examine the effects of CN-subunit interactions on subunit degradation, we assayed the degradation of the subunits associated with CN. Experiments were performed on all four nAChR subunits individually expressed with CN (Fig. 4, C–F). After the pulse-chase protocol, the total pool of subunits was immunoprecipitated, and band intensities were determined at different times after labeling, or CN was immunoprecipitated and band intensities were determined for the subunits that co-precipitated with CN. With increasing chase time, the interactions between CN and subunits are increased. This indicates that the decay is not a measure of subunits disassociating from CN but rather that the decay measures the degradation of the subunits bound to CN. The increased interaction between CN and the subunits with chase times also indicates that CN slows the degradation of the subunits. If the subunits in the CN-subunit complex degraded only at a single slower rate, the degradation rates of the co-precipitated subunits should be single exponential decay. This is not observed, and each of the four subunits bound to CN are degraded at two distinct rates with at least a 10-fold difference. Also, the two rates of decay mirror what was observed with the total subunit pool, which indicates that the fast rate does not result from subunit dissociation from CN. The fast rate of decay for δ subunits is more than 10-fold faster then the decay measured in the absence of CN. Thus, the subunit interactions with CN can expedite the degradation for a portion of the subunits while slowing the degradation for the rest of the subunits. This appears the case for the CN with δ subunits and ERp57 with α subunits.

ERp57 and CN Together or BiP-T37G Blocks Formation of nAChR Bgt Binding Sites

Interactions with CN and ERp57 act to extend the lifetime of nAChR subunits (Fig. 4). This stabilization should increase nAChR subunit numbers in the ER and, if available to assemble, increase subunit assembly into nAChRs. Consistent with this possibility, over-expression of CN with the mouse nAChR subunits was reported to increase nAChR assembly and expression 2-fold (46). To address this issue in more detail, we assayed the effects of CN transfection on nAChR expression, both for mouse nAChRs used by Chang et al. (46) and Torpedo AChRs. All four mouse nAChR subunit cDNAs were transfected together with the CN cDNA (Fig. 5A). In agreement with Chang et al. (46), CN increased mouse nAChR expression as assayed by 125I-α-bungarotoxin (125I-Bgt) binding 2-fold compared with cultures in which only nAChR subunit cDNAs were transfected. 125I-Bgt binding to both the cell surface receptors and the total cellular pool was increased 2-fold. However, we also observed the 2-fold increases in 125I-Bgt binding to both receptor pools for cultures in which the total amount of transfected DNA was balanced with the addition of expression vector without the CN cDNA insert (empty vector). These control conditions were not performed in the study of Chang et al. (46), and we conclude that CN overexpression has no affect on nAChR trafficking to the cell surface or the formation of new nAChRs in the ER.

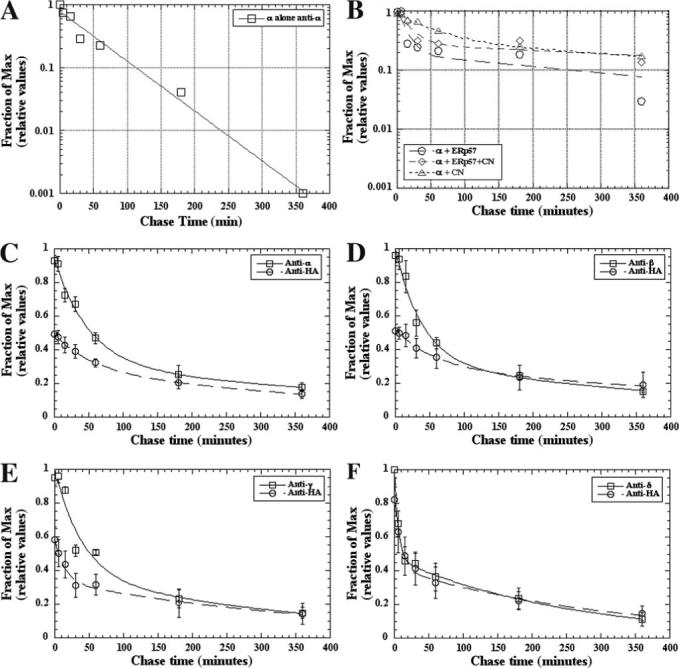

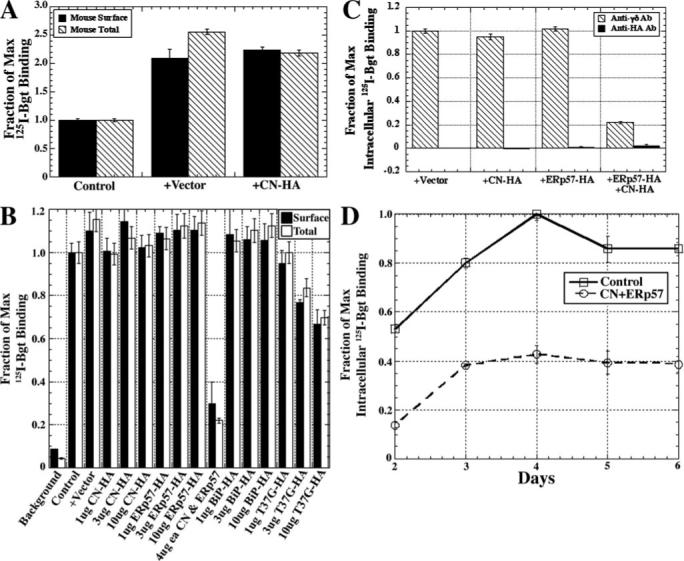

FIGURE 5. T37G-BiP or ERp57 together with CN inhibits Bgt-binding AChRs.

A, effect of CN-HA on the expression of surface and intracellular mouse AChRs as measured by 125I-Bgt binding. The fractions of maximum values shown were calculated by dividing all 125I-Bgt counts by the number of 125I-Bgt counts in the control. B, effect of varying amounts of BiP, T37GBiP, ERp57, or CN-HA cDNA on the expression of surface (black bars) or total (open bars) Torpedo AChRs as measured by 125I-Bgt binding. Background was determined by preincubating cells in 10 mm carbamylcholine prior to the addition of 125I-Bgt. Fractions of maximum values shown were calculated by dividing all 125I-Bgt counts by the number of 125I-Bgt counts in the control. C, effect of transiently expressing the four Torpedo subunits along with 10 μg of vector, CN-HA, ERp57-HA, or both on intracellular Bgt binding AChRs. Cell surface AChRs were blocked with the addition of cold Bgt before cells were harvested for the assay. Fractions of maximum values shown were calculated by dividing all 125I-Bgt counts by the number of 125I-Bgt counts in the anti-γδ Ab-purified vector sample. D, effect of coexpression of both CN and ERp57 on release of nAChRs from the ER. Cells transiently expressing the Torpedo subunits along with both CN and ERp57 were shifted to 20 °C for the times indicated. Cell surface Bgt AChRs were blocked by the addition of cold Bgt to the medium at the temperature shift. The cells were then solubilized, and 10 nm 125I-Bgt was added to the cell lysate along with either anti-α or anti-HA Ab. Fraction of maximum values shown were calculated by dividing all 125I-Bgt counts by the number of 125I-Bgt counts in the monoclonal Ab 35 purified control sample at day 4.

A similar set of experiments was performed with Torpedo nAChR subunits (Fig. 5B). Again, empty vector increased 125I-Bgt binding to both receptor pools about as well as similar amounts of CN-HA, although the increases were not as large as observed with the mouse nAChR (Fig. 5A). We obtained the same results when we expressed ERp57-HA (Fig. 5B) or BiP (Fig. 5B) with Torpedo nAChR subunits. Thus, CN, ERp57, or BiP alone with the nAChR subunits did not alter levels of nAChR expression. In addition, using a cell line that stably expresses Torpedo nAChRs and CN-HA, we found no change in nAChR pools compared with cells with nAChRs alone (data not shown).

Changes in nAChR expression were observed when CN-HA and ERp57-HA together or when the mutated BiP construct, T37G, were transfected with nAChRs. With CN-HA and ERp57-HA, the numbers of surface and total nAChR levels were decreased by 60−80% as assayed by 125I-Bgt binding, whereas with T37G, surface and total nAChR levels were decreased by ∼35% (Fig. 5B). To begin to address how chaperone-subunit interactions could be blocking Bgt site formation, we tested whether the chaperones associate with the subunits after Bgt site formation. Specifically, we tested whether 125I-Bgt binding sites co-precipitated with the chaperones (Fig. 5C). No significant amount of 125I-Bgt binding sites co-precipitated with CN-HA, ERp57-HA, BiP-HA, T37G-HA, or CN-HA and ERp57-HA together. Bgt site formation occurs during nAChR assembly in the ER (25, 32). These findings, therefore, indicate that the chaperones dissociate during assembly prior to Bgt site formation, and the actions of CN-HA and ERp57-HA together and T37G-HA that block Bgt site formation precede Bgt site formation. To further test this, we addressed whether transfection of CN-HA and ERp57-HA together altered the time course at which new Bgt binding sites formed during nAChR assembly (Fig. 5D). CN-HA and ERp57-HA reduced the levels of Bgt binding sites formed but did not have any significant effect on the time course of Bgt binding site formation. Thus, it appears that CN and ERp57 dissociate from nAChR subunits prior to formation of Bgt binding sites on assembling receptor subunits.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have characterized and compared how the ER chaperones, CN, ERp57, and BiP, interact with nAChR subunits and affect their assembly. A significant difference between BiP and the other two chaperones was that the levels of nAChR subunit association as measured by co-immunoprecipitation were much lower for BiP than for CN and ERp57. The levels of subunit association were increased by a mutation of the ATPase site that slows substrate release. The picture that emerges from our results is that BiP-subunit interactions are relatively short lived. This conclusion is also consistent with previous studies of BiP interactions with other substrates, from which it was concluded that BiP undergoes “continuous binding” cycles of BiP to and from substrates rather than “stable binding” of BiP to substrate as previously suggested (16). The short lived nature of the associations between BiP and the nAChR subunits limited the kinds of analysis that we could perform compared with the other two chaperone proteins that we assayed.

In contrast to the interaction of BiP with the subunits, the interactions of ERp57 and CN were long lived. Part of the explanation for the tight and long lived interaction between ERp57 and the nAChR subunits is that intermolecular disulfide bonds appear to transiently form between nAChR subunits and ERp57 (Fig. 1). The transient disulfide bonds are consistent with ERp57 being a disulfide isomerase, and the formation of transient mixed disulfide bonds between ERp57 and other folding proteins has been observed previously for viral glycoproteins (10). However, a distinction from what was observed previously is that ERp57 associations with nAChR subunits occurred with the nAChR subunit subunits lacking N-glycosylation sites, indicating that that ERp57 associated directly with the peptide portion of the subunits, similar to what we have observed with CN (7).

One consequence of the long lived association of ERp57 and CN with the subunits was that ERAD was slowed by more than 1 order of magnitude (Table 1). We were able to directly estimate association lifetimes of the chaperones with the subunits by measuring the rate of degradation of subunits that co-precipitated with CN (Fig. 4, C–F). From these results, we estimated that the lifetime of CN-subunit associations with individual subunits was in the range of 250−600 min. In the absence of chaperone co-expression, subunit ERAD occurred as single exponential decay with a lifetime in the range of 50−70 min. Single exponential decay most likely occurred because the subunits are overexpressed relative to endogenous ER chaperones. In a different study when each nAChR subunit was stably expressed at much lower levels (26), subunit ERAD could only be fit by multiple exponentials, consistent with chaperone-bound subunits with slower ERAD and unbound subunits with faster ERAD. The effects of ERp57 on subunit degradation were similar to that of CN (Fig. 4B and Table 1), indicating that its associations with the subunits were of a similar duration. In a previous study (26), we found that nAChR subunit stabilization, which occurred when we blocked subunit degradation by the proteasome, increased nAChR subunits in the ER and, in turn, increased nAChR assembly.

Surprisingly, the subunit stabilization, which occurred with co-expression of CN or ERp57, resulted in no increase in nAChR assembly. We were unable to reproduce the results of a previous report that overexpression of CN with the mouse nAChR subunits increased nAChR assembly and expression 2-fold (46) (Fig. 4A). Thus, any excess subunits that result from stabilization by CN and ERp57 appear not to be entering the pool of assembling subunits, and it would appear that these subunits are sequestered by the CN and ERp57 interactions. In addition to stabilizing nAChR subunits, some of the subunit associations with CN and ERp57 had the opposite effect and clearly hastened the rate of subunit degradation. This effect was most evident for CN associations with δ subunits and ERp57 associations with α subunits. In both cases, the chaperone association caused more than 50% of the subunits to degrade at a rate 5−10-fold faster (Table 1). These effects of CN and ERp57 in which the rate of subunit ERAD is increased have been observed for other proteins, such as α1-antitrypsin (47). Other studies indicate that CN acts via EDEM to hand over proteins, such as α1-antitrypsin, to ERAD (48, 49), although the studies imply that CN and EDEM interact via the N-linked glycans on the substrates, which does not appear to be the case for the nAChR subunits. Thus, we conclude that CN and ERp57 facilitate two opposing functions of the ER quality control system: stabilization of folding proteins and the disposal of misfolded proteins.

Several of our results indicate that ERp57 and CN act in concert and together have effects not observed with each chaperone alone. First is our finding that ERp57 and CN co-precipitate with each other, indicating that the two proteins are found in a complex (Fig. 4). Second, the levels of individual nAChR subunits that co-precipitated with the chaperone proteins were higher when ERp57 and CN were co-expressed compared with when each chaperone was expressed separately. Finally, we found that the levels of surface and total nAChRs, as assayed by 125I-Bgt binding, were unaffected by the presence of ERp57 or CN alone. However, nAChR levels, both surface and intracellular nAChRs, were reduced up to 60−80% (Fig. 5) when ERp57 and CN were present together with the subunits. Because Bgt binding sites form on nAChR subunits during their assembly, the effects of ERp57 and CN together appear to occur during nAChR assembly, with the result that nAChR assembly is highly reduced. Furthermore, because 125I-Bgt binding sites do not co-precipitate with ERp57 and CN (Fig. 5C), the effects of ERp57 and CN must occur in an early step of nAChR assembly prior to Bgt binding site formation.

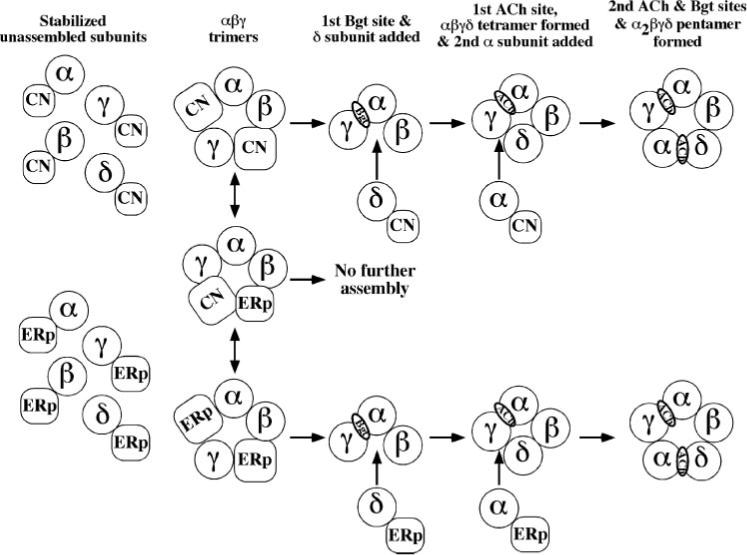

Why do ERp57 and CN alone allow nAChR assembly but together act to block assembly? One possibility is that the ERp57-CN complexes only associate with unassembled subunits before they have assembled into early intermediates. The associations of either ERp57 or CN alone stabilize the unassembled nAChR subunits but allow the subunits to assemble together. When ERp57-CN complexes associate with the subunits, their ability to assemble with other subunits is blocked in large part. The other possibility is that the ERp57-CN complexes associate with the assembly intermediates, and this intermediate can lead to blocked assembly. We had previously proposed that CN interacts with assembling nAChR subunits in the ER (7). In this model, we suggested that newly synthesized nAChR subunits interact with either chaperone proteins or other nAChR subunits in order to prevent subunit misfolding and ERAD. Without one or the other of these interactions, subunits are rapidly degraded by ERAD, as is observed with overexpressed subunits when expressed alone (Fig. 3A and Table 1). A similar model is depicted in Fig. 6, which incorporates our new data with ERp57 and CN together with ERp57.

FIGURE 6. Potential role for CN/ERp57 in AChR assembly.

Data from this study and a previous study (7) demonstrate that CN and ERp57 bind to newly synthesized AChR subunits. Newly synthesized AChR subunits either rapidly assemble into αβγ trimers or remain unassembled (32). In the model, unassembled subunits are rapidly degraded via proteasomes (26) or stabilized to facilitate their assembly. We propose that the early assembly steps are slowed by the need to shed ER chaperones from the subunits. As shown in the model, shedding of CN or ERp57 from the unassembled δ and α subunits to be added as well as from the αβγ trimers occurs during ER assembly. The tight association between the CN-ERp57 complex and αβγ trimers can block subsequent assembly events leading to a dead end or act to slow the assembly process when CN or ERp57 is displaced to initiate subsequent assembly events. It is also possible that ER-resident chaperone proteins, in particular ERp57, could help mediate subunit processing events that occur when the subunits are partially assembled complexes.

There are additional reasons why ER chaperones might be binding to assembly intermediates. First, the early intermediates lack the full complement of subunits, and chaperones could counter geometric constraints on subunit-subunit interactions that prevent full coverage of the labile regions unless they are part of the final nAChR pentameric arrangement. In this way, chaperone proteins serve a “place-holding” role for incoming subunits during the assembly process. Another reason why ER chaperone proteins could associate with partially assembled intermediates is to slow or even prevent subunit folding and processing events that occur after the subunits have partially assembled. We have determined that subunit folding continues after formation of αβγ trimers and results in formation of Bgt binding sites and agonist binding sites on αβγ trimers, αβγδ trimers, and α2βγδ pentamers (32, 36, 37). The formation of these ligand binding sites and the assembly of the δ and second α subunits are very slow events occurring over 1−2 h at 37 °C. In Fig. 6, we propose that these steps are slowed by the need to shed ER chaperones from the subunits. As shown in the model, shedding of CN or ERp57 from the unassembled δ and α subunits to be added as well as from the αβγ trimers occurs during ER assembly. The tight association between the CN-ERp57 complex and αβγ trimers can block subsequent steps in assembly, as shown in Fig. 6. It is also possible that ER-resident chaperone proteins, in particular ERp57, could help mediate subunit processing events that occur when the subunits are partially assembled complexes. Both disulfide binding (36) and N-linked glycan trimming (7, 50) of the subunits occur as they assemble in the ER. Whether ER chaperones block subunit folding and/or help mediate specific processing events, our data, overall, strongly indicate that a key function of ER chaperones is to control the rate at which nAChRs fold and assemble.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. I. Wada for the CN-HA construct, S. High for the ERp57 construct, and P. Murray for the BiP-HA construct. We also thank Drs. J. Lindstrom for the subunit-specific monoclonal Abs 148 (β) and 168 (γ) and Toni Claudio for AChR Abs that were critical to the completion of this paper.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health training grant (to C. P. W.) and by grants from NIDA and NINDS, National Institutes of Health, and the Alzheimer's Association (to W. N. G.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The abbreviations used are: ER, endoplasmic reticulum; AChR, acetylcholine receptor; nAChR, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; Ab, antibody; Bgt, bungarotoxin; BiP, immunological heavy chain binding protein; CN, calnexin; DTT, dithiothreitol; ERAD, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation; HA, hemagglutinin; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gething MJ, Sambrook J. Nature. 1992;355:33–45. doi: 10.1038/355033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gething MJ, editor. Guidebook to Molecular Chaperones and Protein-folding Catalysts. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molinari M, Helenius A. Science. 2000;288:331–333. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helenius A, Aebi M. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004;73:1019–1049. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danilczyk UG, Williams DB. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:25532–25540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leach MR, Williams DB. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:9072–9079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wanamaker CP, Green WN. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:33800–33810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501813200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliver JD, van der Wal FJ, Bulleid NJ, High S. Science. 1997;275:86–88. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zapun A, Darby NJ, Tessier DC, Michalak M, Bergeron JJ, Thomas DY. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:6009–6012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molinari M, Helenius A. Nature. 1999;402:90–93. doi: 10.1038/47062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leach MR, Cohen-Doyle MF, Thomas DY, Williams DB. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:29686–29697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schrag JD, Bergeron JJ, Li Y, Borisova S, Hahn M, Thomas DY, Cygler M. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:633–644. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frickel EM, Riek R, Jelesarov I, Helenius A, Wuthrich K, Ellgaard L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:1954–1959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042699099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gething MJ. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 1999;10:465–472. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1999.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei J, Gaut JR, Hendershot LM. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:26677–26682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendershot L, Wei J, Gaut J, Melnick J, Aviel S, Argon Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:5269–5274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corsi AK, Schekman R. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137:1483–1493. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.7.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McClellan AJ, Endres JB, Vogel JP, Palazzi D, Rose MD, Brodsky JL. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1998;9:3533–3545. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plemper RK, Bohmler S, Bordallo J, Sommer T, Wolf DH. Nature. 1997;388:891–895. doi: 10.1038/42276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brodsky JL, Werner ED, Dubas ME, Goeckeler JL, Kruse KB, McCracken AA. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:3453–3460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith MM, Lindstrom J, Merlie JP. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:4367–4376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu Y, Ralston E, Murphy-Erdosh C, Hall ZW. J. Cell Biol. 1989;109:729–738. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.2.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross AF, Green WN, Hartman DS, Claudio T. J. Cell Biol. 1991;113:623–636. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.3.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gelman MS, Chang W, Thomas DY, Bergeron JJ, Prives JM. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:15085–15092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merlie JP, Lindstrom J. Cell. 1983;34:747–757. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90531-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christianson JC, Green WN. EMBO J. 2004;23:4156–4165. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keller SH, Lindstrom J, Taylor P. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:22871–22877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keller SH, Lindstrom J, Taylor P. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:17064–17072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.17064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blount P, Merlie JP. J. Cell Biol. 1991;113:1125–1132. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.5.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paulson HL, Ross AF, Green WN, Claudio T. J. Cell Biol. 1991;113:1371–1384. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.6.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forsayeth JR, Gu Y, Hall ZW. J. Cell Biol. 1992;117:841–847. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.4.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green WN, Claudio T. Cell. 1993;74:57–69. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90294-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Margolskee RF, McHendry-Rinde B, Horn R. BioTechniques. 1993;15:906–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Gene (Amst.) 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eertmoed AL, Vallejo YF, Green WN. Methods Enzymol. 1998;293:564–585. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)93034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green WN, Wanamaker CP. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:20945–20953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green WN, Wanamaker CP. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:5555–5564. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-15-05555.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braakman I, Helenius J, Helenius A. EMBO J. 1992;11:1717–1722. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gehle VM, Walcott EC, Nishizaki T, Sumikawa K. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1997;45:219–229. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollock S, Kozlov G, Pelletier MF, Trempe JF, Jansen G, Sitnikov D, Bergeron JJ, Gehring K, Ekiel I, Thomas DY. EMBO J. 2004;23:1020–1029. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murray PJ, Watowich SS, Lodish HF, Young RA, Hilton DJ. Anal. Biochem. 1995;229:170–179. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaut JR, Hendershot LM. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:7248–7255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Claudio T, Paulson HL, Green WN, Ross AF, Hartman DS, Hayden DA. J. Cell Biol. 1989;108:2277–2290. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.6.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green WN, Ross AF, Claudio T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991;88:854–858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blount P, Merlie JP. J. Cell Biol. 1990;111:2613–2622. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang W, Gelman MS, Prives JM. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:28925–28932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qu D, Teckman JH, Omura S, Perlmutter DH. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:22791–22795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molinari M, Calanca V, Galli C, Lucca P, Paganetti P. Science. 2003;299:1397–1400. doi: 10.1126/science.1079474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oda Y, Hosokawa N, Wada I, Nagata K. Science. 2003;299:1394–1397. doi: 10.1126/science.1079181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitra M, Wanamaker CP, Green WN. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:3000–3008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-03000.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]