Abstract

We examined target selection for visually-guided reaching in monkeys using a visual search task in which an odd-colored target was presented with distractors. The colors of the target and distractors were randomly switched in each trial between red and green, and the number of distractors was varied. Previous studies of saccades and attention have shown that target selection in this task is easier when a greater number of homogenous distractors is present. We found that monkeys made fewer reaches to distractors and that reaches to the target were completed more quickly when a greater number of homogenous distractors was present. When the target was presented in a sparse array of distractors, reaches had longer movement durations and greater trajectory curvature. Reaching errors were directed more often to a distractor adjacent to the target, suggesting a spatially coarse-to-fine progression during target selection. Reaches were also influenced by the properties of trials in the recent past. When the colors of the target and distractors remained the same from trial to trial rather than switching, reaches were completed more quickly and accurately, indicating that color priming across trials facilitates target selection. Moreover, when difficult search trials were randomly intermixed with easier trials without distractors, reach latencies were influenced by the difficulty of previous trials, indicating that motor initiation strategies are gradually adjusted based on accumulated experience. Overall, these results are consistent with reaching results in humans, indicating that the monkey provides a sound model for understanding the neural underpinnings of reach target selection.

Introduction

Studies of reaching movements to single targets have provided a wealth of valuable information about the neural mechanisms controlling the planning, kinematics, and dynamics of these movements (e.g., Caminiti et al. 1991, 1998; Cisek et al. 2003; Crammond and Kalaska 1996, 2000; Crutcher and Alexander 1990; Fu et al. 1993; Georgopoulos 1991, 1995; Georgopoulos et al. 1982; Johnson et al. 1996; Kalaska et al. 1989; Moran and Schwartz 1999; Mountcastle et al. 1975; Scott and Kalaska 1997; Scott et al. 2001). However, in the real world, most visual scenes are complex and crowded. Instead of a single isolated object, there are often several different objects competing for attention and directed action. Thus, a complete understanding of the production of goal-directed actions must also incorporate the higher-level processes involved in the selection of a target stimulus from distractors.

Several groups have recently developed monkey models for studying reach target selection (e.g., Cisek 2006; Cisek and Kalaska 2002, 2005; Hoshi et al. 2000; Scherberger and Andersen 2007). Scherberger et al. (2003) used a double-target paradigm to show that choices of targets for reaching movements and for saccades are similarly affected by the amount of time between the presentation of one choice alternative and the other, and that saccades and reaches use a similar head-centered reference frame for target selection. In humans, behavioral studies examining reaching movements in the presence of competing stimuli have shown that movement trajectory and kinematics are affected by the presence of distractors and by the spatial layout of the target and distractors (e.g. Chang and Abrams 2004; Fischer and Adam 2001; Keulen et al. 2002, 2004; Song and Nakayama 2006, 2007a; Tipper et al. 1992, 1998, 2000; Welsh and Elliott 2004, 2005).

Our lab has developed a visual search task to investigate target selection for visually-guided reaching movements. Visual search tasks have been used extensively to study saccade target selection in both humans and monkeys, and there is now a substantial base of knowledge concerning the neural mechanisms of saccade target selection in search (Basso and Wurtz 1998; Bichot and Schall 1999, 2002; McPeek 2006; McPeek and Keller 2002, 2004; Schall and Hanes 1993; Thompson et al. 1996). Using a similar task to study reach target selection has the advantage of allowing direct comparisons to be made between the neural mechanisms underlying target selection for the two different movement modalities. However, there is currently little information about the reaching performance of monkeys during visual search. If the monkey is to serve as a model for studying the neural mechanisms of reach target selection, it is critical to understand the behavioral characteristics of reaching movements in monkeys during search, and to determine the extent to which this behavior is similar to that of humans.

Song and Nakayama (2006, 2007a) recently used a pop-out search task to investigate human reaching performance in visual search. Our task is based on theirs, and is very similar to those used to study saccade target selection and visual attention. In our task, an odd-colored target is presented either in an array of homogenous distractors or alone, and monkeys are rewarded for reaching to and touching the target (Fig. 1). In this study, we examine two aspects of reaching movements in search: first, the effect of varying the number of distractors in the search array; and second, the effect of previous trials on performance in the current trial.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagrams of a single target trial (A), and color-oddity search trials (B-E). In single target trials, a lone target is presented without distractors, while in search trials an odd-colored target is presented with 3, 5, 7, or 11 distractors.

In humans, Song and Nakayama (2006) found that reaches to a color-oddity target are initiated and completed more rapidly when a greater number of homogenous distractors is present. These results parallel those seen for saccade target selection in humans and monkeys (Arai et al. 2004; Findlay 1997; McPeek et al. 1999; McSorley and Findlay 2003), and for shifts of attention in humans (Bravo and Nakayama 1992; Maljkovic and Nakayama 1994). An improvement in target selection with more distractors seems surprising at first glance, but, in fact, is consistent with bottom-up models of target selection (Julesz 1986; Koch and Ullman 1985) which predict that it is easier to localize a pop-out target when it is embedded in a dense array of homogenous distractors than in a sparse array. In the first section of this study, we will investigate whether this relationship between distractor number and target selection holds for reaching movements in monkeys.

Perception and action are not simply dependent on the characteristics of the current trial, but rather, depend critically on the history of trials, particularly when previous and current trials share similar stimulus features or responses (de Lussanet et al. 2002; Luce 1986; Maljkovic and Nakayama 1994; Maloney et al. 2005). In human subjects, Song and Nakayama (2006) used a color-oddity reaching task in which the color of the target and distractors could either remain the same or switch from trial to trial. They found that reaches to the target are facilitated when the color of the target remains the same, and as the number of consecutive same-color target repetitions increases, reaches towards the target are initiated and completed increasingly quickly. In contrast, when the target color switches from trial to trial, initial reaches are directed toward a distractor more often.

Such history effects are also seen for other factors, such as trial difficulty (Mozer et al. 2007; Taylor and Lupker 2001). Song and Nakayama (2007a) demonstrated that when relatively easy single target trials (Fig. 1A) and more difficult search trials (Fig. 1B) are randomly mixed within a block, the latency of movement initiation in a given trial depends on the difficulty of the previous trials. During a sequence of easier trials, initiation latencies become shorter. In contrast, during a sequence of more difficult search trials, latencies increase. The second section of the current study examines the history effects of target color repetition and trial difficulty repetition for reaching movements in monkeys.

Methods

Two male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) weighing 6–11 kg were used in this study. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute approved all experimental protocols. We complied with the guidelines of the Public Health Service policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Apparatus

Testing was performed in a dimly illuminated room. Data collection and storage were controlled by Power Mac G4, which also generated the visual displays using software constructed with the Video Toolbox library (Pelli 1997). Visual stimuli were presented on a 17 inch color CRT touch sensitive monitor (ELO touch systems), positioned 25.5 cm in front of the monkeys. The monitor had a spatial resolution of 800 × 600 pixels and a refresh rate of 75 Hz.

Stimuli and behavioral procedure

The two monkeys (H and J) were seated in a primate chair. Monkey H’s head was restrained for the duration of the testing sessions, while Monkey J’s head was unrestrained. Both monkeys were trained to perform target-reaching tasks for liquid reward and were allowed to work to satiation. The task started when the monkeys touched a yellow square, which appeared at the center of the monitor and subtended 1–2° with a luminance of 1.6 cd/m2 against a black homogeneous background of 0.2 cd/m2. The monkeys were required to keep their hand on this yellow square during an interval of 450–550 ms. At the end of this randomly-varying interval, the square was extinguished and a single target (Fig. 1A, single target task) or an odd-colored target along with multiple distractors (Fig. 1B–E, color-oddity search task) was presented. In search, the number of distractors was varied across blocks, and was 3, 5, or 11 for Monkey J and 3, 5, or 7 for Monkey H. A larger share of blocks was run in the 3 distractors condition. Most blocks consisted of only single-target trials or only search trials, and the order of blocks was randomly varied. To examine the sequential effects of single-target vs. search trials, we ran additional blocks of trials in which the two trial types were randomly intermixed in equal proportion. In these intermixed blocks, the number of distractors was held constant at three. Each block consisted of 60–80 trials.

The stimuli consisted of discs subtending 2.5° of visual angle (1.1 cm in diameter on the screen). The discs were colored either red or green, with measured luminance values of 0.9 cd/m2 and 1.2 cd/m2, respectively. The color of the target was randomly selected in each trial to be either red or green, and the distractors, when present, were all of the opposite color. The stimuli were presented at an eccentricity of 12° or 15° for Monkey J and 15° for Monkey H (5.4 and 6.7 cm from the center, respectively). The position of the target was randomly selected in each trial from 12 possible directions, equally spaced around the clock. In the search task, the target and distractor stimuli were arranged uniformly around an imaginary circle, maintaining an equal eccentricity from the center. The display remained onscreen until a response was made. The monkeys were rewarded if the first point at which the hand touched the screen (after lifting off from the center point) was within 4–5° of the correct target location. Monkey J typically used the tip of the right index finger (D2), and Monkey H used the tip of the right middle finger (D3) to touch the screen.

Following several weeks of training, Monkey J performed 4504 search and 2322 single target trials and Monkey H performed 3155 search trials and 1463 single target trials. Among those, 946 single target and 936 search trials (3 distractors) from Monkey J, and 503 single target trials and 515 search trials (3 distractors) in Monkey H were presented in intermixed blocks.

In a later set of sessions, a small reflective hemisphere was taped to the right hand, ~1 cm from the tip of the index finger of Monkey J and the middle finger of Monkey H in order to measure reach movement trajectories. The reflective hemisphere was illuminated by infrared light and was optically tracked at a rate of 60 Hz using a Northern Digital Polaris tracker. The left arm was loosely restrained and the head was restrained in both monkeys. In these experiments, the target was randomly presented in each trial at one of four locations (45°, 135°, 225°, and 315° with respect to horizontal) at an eccentricity of 15°. When distractors were present, they were spaced uniformly around an imaginary circle at the same eccentricity as the target. In these sessions, Monkey J performed an additional 1069 search trials with 3 distractors and 322 single target trials, and Monkey H performed an additional 1094 and 455 trials, respectively.

Data analysis

Off-line data analysis was conducted on temporal and spatial aspects of the reaching movements: initiation latency, movement duration, total time, reach endpoint, and target selection error. Movement onset was the time at which the finger lifted from its initial position in the center of the touchscreen, and initiation latency was defined as the interval between stimulus and movement onset. Movement duration was defined as the interval between movement onset and target acquisition, as measured by the touchscreen. Total time was the sum of initiation latency and movement duration.

Reach endpoint was measured as the first location contacted on the touchscreen after movement onset. A trial was classified as a target selection error when the reach endpoint was more than 5° away from the target. Only trials in which the correct target was selected were included for analyses of initiation latency, movement duration and total time.

When reaching movements were tracked, movement velocity was calculated from the 3D position traces after filtering with a low-pass filter (cutoff frequency of 25 Hz). The beginning and end of reaching movements were detected using a velocity criterion (8–10 cm/sec). The algorithm’s identification of movements was inspected to verify its accuracy. We calculated the radial direction of movements at each point during movement duration. We defined radial direction as the direction of the vector from the initial starting position to the current hand position in the plane of the monitor.

The curvature of movement trajectories was quantified by calculating the maximum curvature of the movement in the 2D plane of the video monitor. Maximum curvature was defined as the maximum perpendicular distance from a straight-line path between the start and end points of a movement trajectory divided by the length of the straight-line path (Desmurget et al. 1997; Smit and Van Gisbergen 1990; Song and Nakayama 2006, 2007a, b).

Results

Effect of the number of distractors on reach target selection

If target selection for reaching movements in monkeys is similar to target selection for human reaching (Song and Nakayama 2006), saccades (Arai et al. 2004; McPeek et al. 1999), and shifts of attention (Bravo and Nakayama 1992; Maljkovic and Nakayama 1994), then we expect reaching performance to improve as the number of homogenous distractors increases. To determine how distractors affect reaching, we analyzed data from search trials according to the number of distractors. The number of distractors was randomly varied among 3, 5 or 11 for Monkey J and 3, 5, or 7 for Monkey H between blocks of trials. Data from single target trials without distractors were collected in separate blocks.

The upper panel of Figure 2 shows the proportion of target selection errors for each monkey as a function of the number of distractors. A target selection error was defined as a reach that ended more than 5° from the target location (see Methods). For comparison, the proportion of reaches ending more than 5° from the target in the single-target condition is plotted at the extreme left of the abscissa. Not surprisingly, the single-target condition showed the fewest target selection errors, and the proportion of errors was significantly greater when 3 distractors were presented with the target. As the number of distractors increased, the proportion of target selection errors decreased, and the significance of this decreasing trend was verified by logistic regressions (P < 10−8 for J and P < 10−6 for H). Thus, when a target is presented with distractors, a greater number of homogenous distractors facilitates reach target selection in monkeys.

Figure 2.

Effect of the number of distractors on reaching performance. The upper panels show target selection error rate (proportion of reaches that end more the 5° from the target location) for each monkey as a function of the number of distractors in the search array. The middle panels show the total time as a function of the number of distractors for each monkey. Total time is defined as the time from stimulus onset to finger contact with the target location. For comparison, the error rate and total time for single-target trials without distractors are shown at the extreme left of the plots. In the lower panels, total time was decomposed into initiation latency (the time from target onset to finger lift-off) and movement duration (time from lift-off to contact with the touchscreen). For comparison, latency and duration for single-target trials without distractors are shown at the extreme left. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean in this and all subsequent Figures.

Effect of the number of distractors on reaching times

In the previous section, we showed that when more distractors are present in the search display, fewer target selection errors are made. Here, we analyze reach times, and find that the improvement in performance with more distractors is also reflected in the timing of the movements. Our primary temporal measure was the total time needed to reach the target, rather than initiation latency or movement duration. Unlike saccadic eye movements, the duration of reaching movements can be voluntarily controlled, and previous studies have suggested that initiation latency and movement duration can be traded-off depending on response strategy, instructions, practice and individual differences (Danev et al. 1971; Inomata 1980; Phillips and Glencross 1985; Proctor and Wang 1997; Rubich et al. 2000; Song and Nakayama 2007b). Since total time is the sum of initiation latency and movement duration, it reflects the time needed to actually reach the correct target. Thus, it should accurately reflect target selection difficulty regardless of the trade-off between initiation latency and movement duration.

The middle panel of Figure 2 shows total time as a function of the number of distractors, with data from the single target condition plotted at the left of the abscissa. Reaches to single targets are executed more rapidly than reaches to the same targets presented with distractors. However, as the number of distractors increases, both monkeys show an improvement in performance, with significant decreases in total time (linear contrasts: P < 10−7 for each monkey). Overall, our results show that reaching movements toward a color oddball are facilitated, both in terms of target selection errors and total time, when a greater number of homogenous distractors is present.

When we decomposed total time into initiation latency and movement duration (see Methods), we found that the initiation latencies of Monkey J exhibit a modest but significant decrease as the number of distractors increases from three to five (Figure 2, lower panel; linear contrast: P < 10−7). The magnitude of this decrease is similar to what is seen for human reaching movements (Song and Nakayama 2006). However, Monkey H does not show an apparent change in initiation latency as a function of the number of distractors (P = .11). On the other hand, both monkeys show a significant decrease in movement duration with more distractors, as verified with linear contrasts (P < 10−7 for J and P < 10−6 for H).

Analysis of endpoint errors

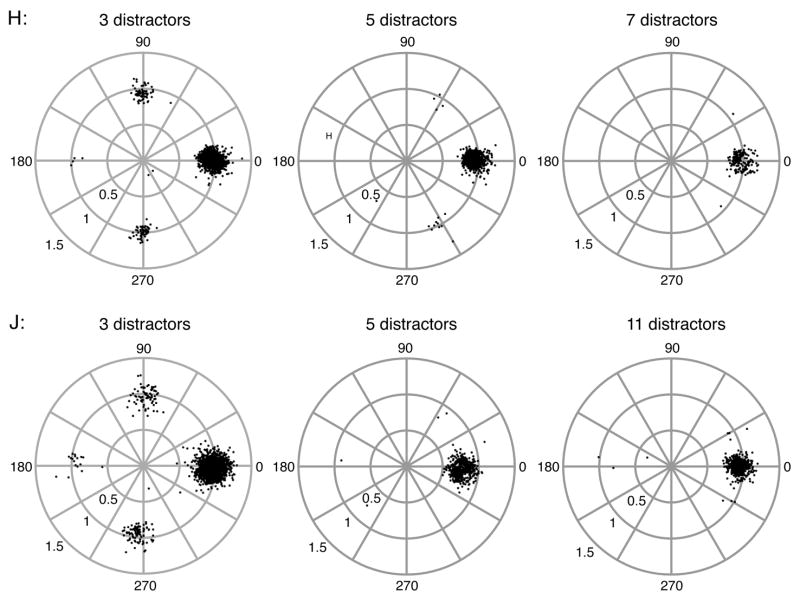

To gain further insight into how targets are selected from distractors for reaching movements, we analyzed the pattern of reach endpoints in search trials. Reach endpoints in each distractor condition for both monkeys are plotted in Figure 3. We normalized the endpoints by a simple rotation and amplitude scaling, such that reaches to the correct target location correspond to an angle of 0° and an amplitude of 1. Thus, for example, in the 3-distractor case, the distractors are located at 90°, 180°, and 270°. For both monkeys, reach endpoints tended to cluster around the locations of the stimuli, similar to what has been seen for reaching in humans (Song and Nakayama 2006). This pattern is similar to what is seen for saccades, except that misdirected saccades show a greater tendency to be hypometric (ending before the distractor) and, less commonly, to end between two stimuli (averaging movements; e.g., Findlay 1997; McPeek and Keller 2001).

Figure 3.

Reach endpoints of search trials with 3, 5 and 7 distractors for Monkey H (upper) and 3, 5 and 11 distractors for Monkey J (lower). The endpoints are normalized by a rotation, such that the correct target location is always represented at an angle of 0° and amplitude 1. For instance, in the 3-distractor case, the distractors are located at 90°, 180°, and 270°. Errors were more likely to be directed to one of the distractors near the target than to the distractor furthest from the target location.

Interestingly, in the 3-distractor condition, both monkeys directed significantly fewer errors to the distractor furthest from the target (180° direction) than to the distractors adjacent to the target (90° and 270° in direction), as confirmed with binomial tests (P < 1.7×10−13 for J and P < 2.5×10−15 for H). Although very few errors were made in trials with more than 3 distractors, when error were made, they also tended to be directed to distractors located near the target, and were seldom directed to distractors in the opposite hemi-field from the target. The fact that more errors are directed to stimuli closer to the target indicates that coarse-scale information about the correct target location can influence incorrect reaches. Such a pattern has also been seen for saccade target selection in monkeys (Bichot and Schall 1999; McPeek and Keller 2001) and humans (Findlay 1997; Gilchrist et al. 1999).

Color priming

In addition to the effects of distractors on reaching movements, we also examined how trials in the past affect reaching performance in the current trial. One potent effect, noted in a variety of search tasks, is priming of the target color by previous trials. Reaching studies in humans (Song and Nakayama 2006), saccade target selection studies in monkeys (Bichot and Schall 1999, 2002; Bichot et al. 1996, 2001; McPeek and Keller 2001) and humans (McPeek et al. 1999), and studies of attention in humans (Goolsby et al. 2005; Maljkovic and Martini 2005; Maljkovic and Nakayama 1994) have all shown a facilitation of target selection when the color of the target repeats across trials, as opposed to when it switches.

We examined whether color priming facilitates target selection for reaches in monkeys using data from blocks of search trials with 3 distractors. In each trial, the color of the target was equally likely to switch or remain the same, and we analyzed performance as a function of the number of immediately-preceding trials with the same target color as in the current trial. As shown in Figure 4 (upper), when the target color differs from its color in the previous trial (denoted as 1 on the abscissa), monkeys make the greatest proportion of target selection errors. As the number of color repetitions increases, error rates decline in both monkeys and a significant decreasing trend was verified using logistic regression (P < .0006 for J and P < .002 for H).

Figure 4.

Effect of color priming on reaching performance. Target selection error rate (upper), total time (middle), and movement initiation latency and duration (lower) for each monkey are plotted as a function of the number of consecutive same-color trial in the past. Reaching performance improves when the color of the target remains the same from trial to trial. One on the abscissa denotes trials in which the target color differed from its color in the previous trial; two denotes trials in which the target color was the same as in the previous trial, but differed from its color two trials previously, and so on.

We next examined the effects of color priming on total time. As depicted in Figure 4 (middle), total time decreases in both monkeys as the number of consecutive same-color trials increases. When the target color differs from its color in the previous trial, total time is much longer than when the target color remains the same. As the number of color repetitions increases, total time decreases significantly (linear contrasts: P < .005 for J and P < .025 for H), supporting the idea that color priming facilitates target selection for reaches in monkeys.

As before, we divided total time into initiation latency and movement duration (Fig. 4 lower). Movement duration shows a similar trend to what was seen for total time, decreasing as the number of target color repetitions increases (linear contrasts: P < .025 for J and P < .05 for H). However, a reduction in initiation latency is evident only for Monkey J (P < .025), and not for Monkey H (P=.25).

Movement duration and trajectory curvature

In humans, Song and Nakayama (2006) found that when target selection was difficult, longer movement durations were associated with greater curvature in the movement trajectory: the early portion of the trajectory was frequently directed toward a distractor location, and was corrected in mid-flight so that the movement ended near the target. We examined whether increased movement durations in the current study are also associated with curved movement trajectories by collecting an additional dataset in each monkey in which the reaching movement trajectories were recorded (see Methods). We compared the magnitude of trajectory curvature in the single target task, in which movement durations were shortest, with the trajectory curvature in the 3-distractor search task, in which movement durations were longest.

Since these data were collected after several weeks of additional training in the reaching task, both monkeys generally reached faster than in the previous sessions. Nonetheless, they still consistently demonstrated shorter movement durations in single target trials than in search trials (239.6 (±2.05) vs. 267.2 (±1.49) ms, P < 5×10−16 in J and 185.2 (±3.04) vs. 221.7 (±2.97) ms, P < 2×10−15 in H). Figure 5A–B shows spatial plots of reaching trajectories in Monkey H, color-coded by the location of the target. In single target trials (Fig. 5A), trajectories toward each of the four target locations are relatively straight. In contrast, many curved trajectories are observed in 3-distractor search trials (Fig. 5B), with the early portion of the curved trajectory often directed toward a distractor and corrected in mid-flight.

Figure 5.

Effect of distractors on reach trajectories. A, B show examples of reach trajectories in single target (left) and 3-distractor search (right) for Monkey H. These trajectories are tracked in three dimensions, but, for clarity, only the components in the plane of the touchscreen monitor are shown. Trajectories associated with each target location are depicted by distinct colors: green (45°), blue (135°), red (225°) and black (315°). The scale bar indicates 1cm. C shows a plot of radial direction vs. time during the movement for Monkey J in the single-target task. Radial direction has been normalized such that the target direction corresponds to a direction of 0°. D, E show similar plots of radial direction vs. time in 3-distractor search, for movements with durations in the lower third (short duration: D) and upper third (long duration: E) of the distribution.

Figure 5C–D shows plots of radial direction (see Methods) vs. time during reaching movements made by Monkey J. Here, radial direction has been normalized across target positions, such that a direction of 0° corresponds to the target direction. Figure 5C shows a temporal plot of radial direction for reaches to a single target without distractors. Radial direction quickly stabilizes near the onset of the movement, such that the reach is directed toward the target location (0°). To examine the association between movement duration and trajectory curvature in the 3-distractor search task, we separately plotted radial direction vs. time for movements in this task with durations in the lower third (range: 100–167 ms; mean: 149 ms) and the upper third (range: 217–434 ms; mean: 259 ms). As shown in Fig. 5D, the radial directions of most of the short-duration movements quickly coalesce around the target direction, similar to what is seen in the absence of distractors. On the other hand, the long-duration movements (Fig. 5E) tend to show much more extensive curvature, indicated by changes in radial direction occurring later in the movements.

We quantified the global curvature of the movement trajectories by computing maximum curvature (see Methods), and found that mean maximum curvature is greater in 3-distractor search trials than single target trials (0.12 (±0.0026) vs. 0.15 (±0.0030); Mann-Whitney U test, P < 5×10−4 in J and 0.12 (±0.0029) vs. 0.16 (±0.0051); P < 10−5 in H). To further establish the relationship between movement duration and trajectory curvature, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient between movement duration and curvature in the 3-distractor search trials. In both monkeys, as movement duration increases, maximum curvature also generally increases (Figure 6; Pearson r = .56, P < 7×10−87 in J and r = .64, P < 5×10−104 in H). Thus, the longer movement durations seen in the more difficult target selection condition are associated with greater trajectory curvature. The presence of endpoint errors and longer movement durations when target selection is more difficult suggests that in some trials, movements are initiated before competition between the target and distractors has been fully resolved, similar to what has been concluded for saccadic eye movements (McPeek 2006; McPeek and Keller 2001, 2003).

Figure 6.

Correlation between movement duration and maximum curvature in search. Maximum curvature is plotted against movement duration for 3-distractor search trials in each monkey.

Adjustment of initiation latency according to the difficulty of previous trials

In the previous sections, we found that the number of distractors and the history of target color repetitions have significant effects on reach target selection. Interestingly, these effects manifest themselves strongly in reach endpoints and in the duration of reaching movements, and to a lesser extent in initiation latency. The smaller effect of target selection difficulty on initiation latency suggests that the monkeys are not following a strict strategy of initiating a movement at the moment that target selection is completed. Instead, as suggested in the previous section, it seems that in some trials, movements are initiated before competition between the target and distractors has been fully resolved, leading to target selection errors, increased movement durations, and curved trajectories.

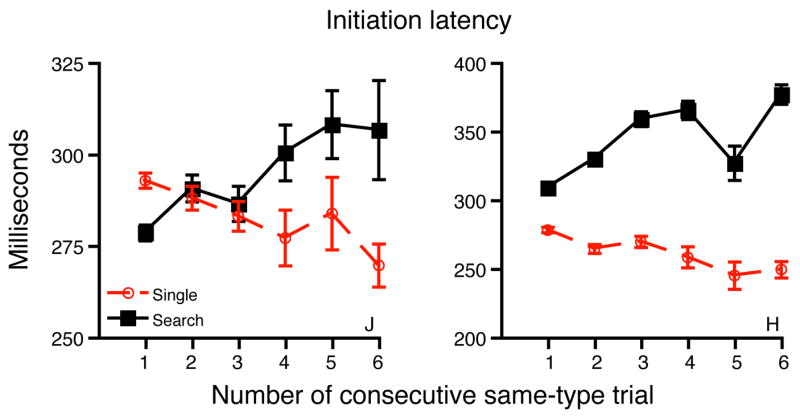

If initiation latency is not determined solely by the difficulty of target selection in the current trial, then what other factors influence latency? One possibility is that initiation latencies are adjusted based on the properties of previous trials. Specifically, initiation latency might be lengthened after a difficult trial, and shortened after an easy trial. To examine this possibility, we intermixed two types of trials: single-target trials, the easiest of our conditions; and search trials with three distractors, the most difficult of our target selection conditions (as shown in Fig. 2). To examine how the difficulty of preceding trials influences movement initiation time, we categorized each trial according to the consecutive number of trials of the same type. Then we analyzed initiation latencies for each trial type (single target vs. search) as a function of the number of consecutive preceding trials of the same type. For instance, in Figure 7, one on the abscissa indicates a trial that differed in type from the previous trial, while two indicates a trial that was the second trial in a row of the same type.

Figure 7.

Movement initiation latencies of randomly-intermixed search and single-target trials as a function of the number of consecutive same-type trials. One on the abscissa indicates trials that differed in type from the previous trial. Initiation latencies gradually become shorter with more consecutive single-target trials, and longer with more consecutive search trials.

As Figure 7 shows, single-target trials are initiated more rapidly when they are preceded by a greater number of single-target trials (P < .025 for each monkey). Conversely, search trials are initiated more slowly as the number of preceding search trials increases (P < .01 for J and P < .001 for H). As a result, the difference in initiation latencies between the two trial types gradually grows with more repetitions. This pattern demonstrates a cumulative adjustment of movement initiation latency according to the previous history of trial difficulty.

Discussion

This study used visual search tasks to investigate reach target selection in monkeys. Search paradigms have been used extensively to study target selection for saccades and shifts of attention, but to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the behavioral characteristics of reaching movements in monkeys during a reaction-time visual search task. The goals of the study are two-fold: first, to systematically characterize the reaching performance of monkeys in visual search tasks, and to compare reach target selection in monkeys with published reports of performance in humans. This is important for establishing the monkey as a model system for understanding the neural mechanisms of reach target selection.

The second goal is to compare the behavioral characteristics of reach target selection in visual search with established results on saccade target selection. A close congruence between these two modalities would suggest that they share common selection mechanisms.

Effect of distractors on reach target selection

We found, first, that monkeys complete reaching movements more rapidly and make fewer target selection errors when a greater number of homogenous distractors is present. More erroneous reaches to a distractor are made, and the total time is longer when the number of distractors is smaller. This finding agrees well with models of target selection, which predict that localization of an odd target will be facilitated when a greater density of homogenous distractors is present (Julesz 1986; Koch and Ullman 1985).

In analyzing the endpoints of the errant reaching movements, we found that target selection errors were made more often to the distractors adjacent to the target. This indicates that spatially coarse information about the correct target location can influence incorrect reaches, and suggests that target selection develops over time in a spatially coarse-to-fine progression. Interestingly, this pattern of results has also been reported for saccade target selection in both humans (Findlay 1997; Gilchrist et al. 1999) and monkeys (Bichot and Schall 1999; McPeek and Keller 2001).

Effect of color priming on reach target selection

We also found that reaches to the target are facilitated when the color of the target remains the same from trial to trial, rather than switching. Fewer target selection errors are made and total time decreases with more repetitions of the target color, indicating that color priming affects target selection for reaching movements in monkeys. The magnitude of this priming effect is similar to what is seen for human reaching movements in a search task (Song and Nakayama 2006).

Movement trajectory

The presence of endpoint errors and longer movement durations when target selection is more difficult suggests that in some trials, movements are initiated before competition between the target and distractors has been fully resolved. When we analyzed movement trajectories in our task, we found that trajectories in the more difficult 3-distractor search task showed significantly greater mean curvature than trajectories in the single-target task without distractors, similar to what has been observed in humans (Song and Nakayama 2006). Furthermore, a correlation analysis revealed a significant trial-by-trial correlation between movement duration and trajectory curvature in the 3-distractor task. These findings support the idea that when competing stimuli are present, goal-directed hand movements can be initiated before the correct target is selected.

Indeed, trajectory curvature has been related to ongoing competition between target and distractor stimuli for both reaches (Song and Nakayama 2006, 2007a; Tipper et al. 1992, 1998, 2000; Welsh and Elliott 2005) and saccades (Arai et al. 2004; Doyle and Walker 2001; McPeek 2006; McPeek et al. 2003; McSorley et al. 2004; Port and Wurtz 2003; Sheliga et al. 1994, 1995). For instance, Tipper and colleagues (1992, 1998, 2000) showed that when subjects reach for a pre-specified target, their reaching trajectories swerve away from distractors. Welsh and Elliott (2005) demonstrated that when a distractor is presented at a precued location while the target is presented at an uncued location, reaching reaction times and trajectory deviations towards the location of the distractor increase. Similarly, when multiple stimuli are presented, saccades show increased curvature in their trajectories (Arai et al. 2004; McPeek and Keller 2001; McPeek et al. 2003; McSorley and Findlay 2003; McSorley et al. 2004; Sheliga et al. 1995; Walker et al. 2006).

Similar effects on target selection for reaching, saccades, and attention

A clear result arising from this study in conjunction with previous studies on saccades and attention in visual search is that varying the number of homogenous distractors has a similar effect on the difficulty of target selection for reaching, saccades, and shifts of attention in search. As the number of distractors increases, target selection is facilitated for saccades in visual search for both human (McPeek et al. 1999; McSorley and Findlay 2003) and monkey subjects (Arai et al. 2004; McPeek and Keller 2001; McPeek et al. 1999), and for reaching movements (Song and Nakayama 2006) and shifts of attention in humans (Bravo and Nakayama 1992; Maljkovic and Nakayama 1994). Furthermore, the effects of color priming on reaching in visual search that we observe here are similar to what has been seen for saccades in both humans (McPeek et al. 1999) and monkeys (Bichot and Schall 1999, 2002; McPeek and Keller 2002), and for shifts of attention in humans (Goolsby et al. 2005; Maljkovic and Martini 2005; Maljkovic and Nakayama 1994).

To quantify the difficulty of target selection for reaching movements, we have focused two measures: the proportion of target selection errors and the total time required to touch the target. Studies of saccades typically analyze target selection errors, but report saccade initiation latency, rather than total time, as their primary temporal measure. The reason for this difference is that saccadic movements have brief, stereotyped durations which largely depend on movement amplitude, and are not under conscious or strategic control. Thus, for saccades, initiation latency and the total time to reach the target are highly correlated. In contrast, reaching movements are more flexible and can be influenced by factors including response strategy, instructions, practice and individual differences. Indeed, subjects can trade-off initiation latency and movement duration (Danev et al. 1971; Inomata 1980; Phillips and Glencross 1985; Proctor and Wang 1997; Rubich et al. 2000; Song and Nakayama 2007b). Thus, they could adopt a strategy of initiating a movement as soon as the stimuli appear, and correcting an initially-incorrect movement in-flight. This would result in a shorter initiation latency and longer movement duration. Alternatively, subjects could wait until the correct motor program is completed, and make a movement directly to the target, resulting in a longer initiation latency and a shorter movement duration. Since total time is the sum of initiation latency and movement duration, we believe that it best captures the difficulty of target selection, regardless of the subjects’ strategy.

In both humans and monkeys, close linkages between gaze position and reaching movements have been shown in numerous studies (e.g., Ballard et al. 1997; Frens and Erkelens 1991; Horstmann and Hoffmann 2005; Johansson et al. 2001; Land and Hayhoe 2001; Land and McLeod 2000; Neggers and Bekkering 2000, 2002; Scherberger et al. 2003; Soechting et al. 2001). Many studies have also shown a linkage between saccades and attention (e.g., Cavanaugh and Wurtz 2004; Corbetta et al. 1998; Deubel and Schnieder 1996; Kowler et al. 1995; McPeek et al. 1999; Moore and Fallah 2001; Müller et al. 2004; Posner 1980; Rizzolatti et al. 1987; Thompson et al. 2005).

Considering these relationships, similar effects of distractor number and color priming on reaching, saccades, and attention could be mediated via a connection between attention and saccades and between gaze position and reaching. In other words, we conjecture that if reaches and saccades were coupled, then the spatiotemporal characteristics of reach movements in this task would be influenced by the same factors influencing saccades, including the allocation of attention. The current results could also be explained if both saccades and reaching were independently guided by attention. In a recent study, Bock & Eversheim (2000) examined the effects of pre-cues on reaching times to a single target, finding that the crucial parameter for obtaining pre-cueing effects was the extent of the area occupied by the pre-cues. Based on this finding, they suggested that the pre-cues influence reaching movements through their effects on spatial attention. Indeed, other studies in humans have argued for an obligatory link between attention and reaching (Chang and Abrams 2004; Deubel et al. 1998; Song and Nakayama 2006; Tipper et al. 1992). Taken together, results from these studies show a close congruence among reaches, saccades, and attention, suggesting the possibility that target selection for all three modalities might be based on a common stage of neural processing.

Effect of the difficulty of previous trials

Finally, we found that the difficulty (single-target vs. search) of trials in the past affects the initiation latency of reaching movement in the current trial. Specifically, initiation latencies for easy single-target trials become faster and those for difficult search trials become slower as the number of same-type trial repetitions increases. Similar behavior has been reported in humans (Song and Nakayama 2007a). This finding indicates that distinctive motor initiation strategies for single-target trials and search trials emerge gradually, based on the history of prior trials. Since the two trial types were randomly intermixed, the monkeys did not have explicit knowledge of upcoming trial type. These results suggest that recent experience can lead to an adjustment of motor initiation strategies, even in the absence of explicit future knowledge.

Neural substrates of reach target selection

The neural substrates of target selection for reaching movements likely involve higher-order movement-related areas in the frontal lobe, including the dorsal premotor area (PMd), and in posterior parietal cortex, including the parietal reach region (PRR).

Single unit recording studies have shown that the pattern of PMd activity changes according to the direction and amplitude of limb movements (Boussaoud and Wise 1993; Crammond and Kalaska 1994), and temporary inactivation of PMd results in reaching movements with directional errors (Kurata and Hoffman 1994). Compared to the primary motor area (MI), the PMd appears to represent more abstract task-related factors, such as stimulus-response mappings, movement preparation, and selection (Caminiti et al. 1998; Crammond and Kalaska 2000; Johnson et al. 1996; Shen and Alexander 1997; Wise et al. 1996, 1997). The role of the PMd when a target must be selected from competing stimuli is not yet fully understood. However, recent studies have demonstrated that when two potential targets are presented for selective reaching, the PMd can simultaneously encode the two competing movement goals during a delay period before the cue to move (Cisek 2006; Cisek and Kalaska 2002, 2005), suggesting a role in target selection.

The parietal reach region (PRR) may also be involved in reach target selection. Previous studies have shown that parietal cortex is involved in the transformation of sensory signals for actions, and that many parietal neurons are active in the planning period of a reach task (Andersen et al. 1985; Buneo et al. 2002; Mountcastle et al. 1975; Snyder et al. 1997, 1998). Scherberger and Andersen (2007) recently used a paradigm in which two potential targets were sequentially presented in opposite directions, and monkeys were allowed to freely choose either target. They found that neural activity in the PRR was strongly linked to target choice, and that target selection could be predicted from activity in the majority of cells. However, it could be argued that this activity represents a motor plan for each stimulus rather than target selection per se (Jackson et al. 2007).

Finally, it is worth noting that activity in the primate frontal eye field and superior colliculus is correlated with covert shifts of attention (e.g.: Ignashchenkova et al. 2004; Thompson et al. 2005), and both areas have been shown to be causally involved in the allocation of covert visual attention (e.g.: Moore and Fallah 2001; Cavanaugh and Wurtz 2004; Müller 2005; Wardak et al. 2006). Thus, to the extent that covert attention is involved in target selection for reaching movements, these areas may also be involved in reach target selection.

Conclusion

In general, our results for monkeys are consistent with what has been observed in humans (Song and Nakayama 2006, 2007a), confirming the validity of the monkey as a model system for understanding the neural mechanisms of reach target selection. The results also show clear similarities with findings on target selection for saccades and attention. Overall, the results indicate that visual search tasks are well-suited for investigating the neural mechanisms of target selection for reaching movements. They allow the difficulty of target selection to be systematically manipulated, and make it possible to directly compare reaching results with the body of knowledge available about the neural mechanisms of target selection for saccades and attention in visual search.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Eye Institute grant EY014885 to R. M. McPeek and by a R. C. Atkinson Fellowship Award to J. H. Song.

References

- Andersen RA, Essick GK, Siegel RM. Encoding of spatial location by posterior parietal neurons. Science. 1985;230:456–458. doi: 10.1126/science.4048942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai K, McPeek RM, Keller EL. Properties of saccadic responses in monkey when multiple competing visual stimuli are present. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:890–900. doi: 10.1152/jn.00818.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard D, Hayhoe M, Pook P, Rao R. Deictic codes for the embodiment of cognition. Behav Brain Sci. 1997;20:723–767. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x97001611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso MA, Wurtz RH. Modulation of neuronal activity in superior colliculus by changes in target probability. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7519–7534. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07519.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichot NP, Schall JD. Effects of similarity and history on neural mechanisms of visual selection. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:549–554. doi: 10.1038/9205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichot NP, Schall JD. Priming in macaque frontal cortex during popout visual search: feature-based facilitation and location-based inhibition of return. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4675–4685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04675.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichot NP, Schall JD, Thompson KG. Visual feature selectivity in frontal eye fields induced by experience in mature macaques. Nature. 1996;381:697–699. doi: 10.1038/381697a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichot NP, Thompson KG, Rao SC, Schall JD. Reliability of macaque frontal eye field neurons signaling saccade targets during visual search. J Neurosci. 2001;21:713–725. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00713.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock O, Eversheim U. The mechanisms of movement preparation: a precuing study. Behav Brain Res. 2000;108:85–90. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussaoud D, Wise SP. Primate frontal cortex: effects of stimulus and movement. Exp Brain Res. 1993;95:28–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00229651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DH. The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spat Vis. 1997;10:433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo MJ, Nakayama K. The role of attention in different visual search tasks. Percept Psychophys. 1992;51:465–472. doi: 10.3758/bf03211642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buneo CA, Jarvis MR, Batista AP, Andersen RA. Direct visuomotor transformations for reaching. Nature. 2002;416:632–636. doi: 10.1038/416632a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caminiti R, Ferraina S, Mayer AB. Visuomotor transformations: early cortical mechanisms of reaching. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1998;8:753–761. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caminiti R, Johnson PB, Galli C, Ferraina S, Burnod Y. Making arm movements within different parts of space: the premotor and motor cortical representations of a coordinate system for reaching to visual targets. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1182–1197. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-05-01182.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh J, Wurtz RH. Subcortical modulation of attention counters change blindness. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11236–11243. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3724-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SW, Abrams RA. Hand movements deviate toward distracters in the absence of response competition. J Gen Psychol. 2004;131:328–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisek P. Integrated neural processes for defining potential actions and deciding between them: a computational model. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9761–9770. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5605-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisek P, Crammond DJ, Kalaska JF. Neural activity in primary motor and dorsal premotor cortex in reaching tasks with the contralateral versus ipsilateral arm. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:922–942. doi: 10.1152/jn.00607.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisek P, Kalaska JF. Simultaneous encoding of multiple potential reach directions in dorsal premotor cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:1149–1154. doi: 10.1152/jn.00443.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisek P, Kalaska JF. Neural correlates of reaching decisions in dorsal premotor cortex: specification of multiple direction choices and final selection of action. Neuron. 2005;45:801–814. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Akbudak E, Conturo TE, Snyder AZ, Ollinger JM, Drury HA, Linenweber MR, Petersen SE, Raichle ME, Van Essen DC, Shulman GL. A common network of functional areas for attention and eye movements. Neuron. 1998;21:761–773. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80593-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crammond DJ, Kalaska JF. Modulation of preparatory neuronal activity in dorsal premotor cortex due to stimulus-response compatibility. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1281–1284. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.3.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crammond DJ, Kalaska JF. Differential relation of discharge in primary motor cortex and premotor cortex to movements versus actively maintained postures during a reaching task. Exp Brain Res. 1996;108:45–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00242903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crammond DJ, Kalaska JF. Prior information in motor and premotor cortex: activity during the delay period and effect on pre-movement activity. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:986–1005. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.2.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crutcher MD, Alexander GE. Movement-related neuronal activity selectively coding either direction or muscle pattern in three motor areas of the monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1990;64:151–163. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danev SG, de Winter CR, Wartna GF. On the relation between reaction and motion time in a choice reaction task. Acta Psychol (Amst) 1971;35:188–197. [Google Scholar]

- de Lussanet MH, Smeets JB, Brenner E. The relation between task history and movement strategy. Behav Brain Res. 2002;129:51–59. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00320-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmurget M, Jordan M, Prablanc C, Jeannerod M. Constrained and unconstrained movements involve different control strategies. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1644–1650. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deubel H, Schneider WX. Saccade target selection and object recognition: evidence for a common attentional mechanism. Vision Res. 1996;255:90–92. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(95)00294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deubel H, Schneider WX, Paprotta I. Selective dorsal and ventral processing: evidence for a common attentional mechanism in reaching and perception. Vis Cogn. 1998;5:81–107. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle M, Walker R. Curved saccade trajectories: voluntary and reflexive saccades curve away from irrelevant distractors. Exp Brain Res. 2001;139:333–344. doi: 10.1007/s002210100742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay JM. Saccade target selection during visual search. Vision Res. 1997;37:617–631. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(96)00218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer MH, Adam JJ. Distractor effects on pointing: the role of spatial layout. Exp Brain Res. 2001;136:507–513. doi: 10.1007/s002210000596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frens MA, Erkelens CJ. Coordination of hand movements and saccades: evidence for a common and a separate pathway. Exp Brain Res. 1991;85:682–690. doi: 10.1007/BF00231754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q-G, Suarez JI, Ebner TJ. Neuronal specification of direction and distance during reaching movements in the superior precentral premotor area and primary motor cortex of monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:2097–2116. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.5.2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos AP. Higher order motor control. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1991;14:361–377. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.002045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos AP. Current issues in directional motor control. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:506–510. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)92775-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos AP, Kalaska JF, Caminiti R, Massey JT. On the relations between the direction of two-dimensional arm movements and cell discharge in primate motor cortex. J Neurosci. 1982;2:1527–1537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-11-01527.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist ID, Heywood CA, Findlay JM. Saccade selection in visual search: evidence for spatial frequency specific between-item interactions. Vision Res. 1999;39:1373–1383. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(98)00242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goolsby BA, Grabowecky M, Suzuki S. Adaptive modulation of color salience contingent upon global form coding and task relevance. Vision Res. 2005;45:901–930. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horstmann A, Hoffmann KP. Target selection in eye-hand coordination: do we reach to where we look or do we look to where we reach? Exp Brain Res. 2005;167:187–195. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi E, Shima K, Tanji J. Neuronal activity in the primate prefrontal cortex in the process of motor selection based on two behavioral rules. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:2355–2373. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.4.2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignashchenkova A, Dicke PW, Haarmeier T, Thier P. Neuron-specific contribution of the superior colliculus to overt and covert shifts of attention. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:56–64. doi: 10.1038/nn1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inomata K. Influence of different preparatory sets on reaction time and arm-movement time. Percept Mot Skills. 1980;50:139–144. doi: 10.2466/pms.1980.50.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson CPT, Albert NB, Roberts RD, Galea JM, Swait G. Target selection: choice or response? J Neurosci. 2007;27:6079–6080. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1454-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson RS, Westling G, Bäckström A, Flanagan JR. Eye-hand coordination in object manipulation. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6917–6932. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06917.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PB, Ferraina S, Bianchi L, Caminiti R. Cortical networks for visual reaching: physiological and anatomical organization of frontal and parietal lobe arm regions. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6:102–119. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julesz B. Texton gradients: the Texton theory revisited. Biol Cybern. 1986;54:245–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00318420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaska JF, Cohen DAD, Hyde ML, Prud’homme MJ. A comparison of movement direction-related versus load direction-related activity in primate motor cortex, using a two-dimensional reaching task. J Neurosci. 1989;9:2080–2102. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-06-02080.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keulen RF, Adam JJ, Fischer MH, Kuipers H, Jolles J. Selective reaching: evidence for multiple frames of reference. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 2002;28:515–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keulen RF, Adam JJ, Fischer MH, Kuipers H, Jolles J. Selective reaching: distractor effects on movement kinematics as a function of target-distractor separation. J Gen Psychol. 2004;131:345–364. doi: 10.3200/GENP.131.4.345-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch C, Ullman S. Shifts in selective visual attention: towards the underlying neural circuitry. Hum Neurobiol. 1985;4:219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowler E, Anderson E, Dosher B, Blaser E. The role of attention in the programming of saccades. Vision Res. 1995;35:1897–1916. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00279-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata K, Hoffman DS. Differential effects of muscimol microinjection into dorsal and ventral aspects of the premotor cortex of monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1151–1164. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.3.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land MF, Hayhoe M. In what ways do eye movements contribute to everyday activities? Vision Res. 2001;41:3559–3565. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land MF, McLeod P. From eye movements to actions: how batsmen hit the ball. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1340–1345. doi: 10.1038/81887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce RD. Response Times: Their Role in Inferring Elementary Mental Organization. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Maljkovic V, Martini P. Implicit short-term memory and event frequency effects in visual search. Vision Res. 2005;45:2831–2846. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maljkovic V, Nakayama K. Priming of popout: I. Role of features. Mem Cognit. 1994;22:657–672. doi: 10.3758/bf03209251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney LT, Dal Martello MF, Sahm C, Spillmann L. Past trials influence perception of ambiguous motion quartets through pattern completion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3164–3169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407157102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPeek RM. Incomplete suppression of distractor-related activity in the frontal eye field results in curved saccades. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:2699–2711. doi: 10.1152/jn.00564.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPeek RM, Han JH, Keller EL. Competition between saccade goals in the superior colliculus produces saccade curvature. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:2577–2590. doi: 10.1152/jn.00657.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPeek RM, Keller EL. Short-term priming, concurrent processing, and saccade curvature during a target selection task in the monkey. Vision Res. 2001;41:785–800. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPeek RM, Keller EL. Saccade target selection in the superior colliculus during a visual search task. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2019–2034. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.4.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPeek RM, Keller EL. Deficits in saccade target selection after inactivation of superior colliculus. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:757–763. doi: 10.1038/nn1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPeek RM, Maljkovic V, Nakayama K. Saccades require focal attention and are facilitated by a short-term memory system. Vision Res. 1999;39:1555–1566. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(98)00228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSorley E, Findlay JM. Saccade target selection in visual search: accuracy improves when more distractors are present. J Vis. 2003;3:877–892. doi: 10.1167/3.11.20. http://journalofvision.org/3/11/20/10.1167/3.11.20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McSorley E, Haggard P, Walker R. Distractor modulation of saccade trajectories: spatial separation and symmetry effects. Exp Brain Res. 2004;155:320–333. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1729-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore T, Fallah M. Control of eye movements and spatial attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1273–1276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021549498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran DW, Schwartz AB. Motor cortical representation of speed and direction during reaching. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:2676–2692. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.5.2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountcastle VB, Lynch JC, Georgopoulos A, Sakata H, Acuna C. Posterior parietal association cortex of the monkey: command functions for operations within extrapersonal space. J Neurophysiol. 1975;38:871–908. doi: 10.1152/jn.1975.38.4.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozer MC, Kinoshita S, Shettel M. Sequential dependencies offer insight into cognitive control. In: Gray W, editor. Integrated Models of Cognitive Systems. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 180–193. [Google Scholar]

- Müller HJ, Krummenacher J, Heller D. Dimension-specific inter-trial facilitation in visual search for pop-out targets: evidence for a top-down modulable visual short-term memory effect. Vis Cogn. 2004;11:577–602. [Google Scholar]

- Müller JR, Philiastides MG, Newsome WT. Microstimulation of the superior colliculus focuses attention without moving the eyes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:524–529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408311101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neggers SF, Bekkering H. Ocular gaze is anchored to the target of an ongoing pointing movement. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:639–651. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.2.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neggers SF, Bekkering H. Coordinated control of eye and hand movements in dynamic reaching. Hum Mov Sci. 2002;21:349–376. doi: 10.1016/s0167-9457(02)00120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelli DG. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: transforming numbers into movies. Spat Vis. 1997;10:437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J, Glencross D. The independence of reaction and movement time in programmed movements. Acta Psychol (Amst) 1985;59:209–225. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(85)90045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port NL, Wurtz RH. Sequential activity of simultaneously recorded neurons in the superior colliculus during curved saccades. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:1887–1903. doi: 10.1152/jn.01151.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI. Orienting of attention. Q J Exp Psychol. 1980;32:3–25. doi: 10.1080/00335558008248231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor RW, Wang H. Differentiating types of set-level compatibility. In: Hommel B, Prinz W, editors. Theoretical Issues in Stimulus-Response Compatibility. Amsterdam: North-Holland; 1997. pp. 11–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Riggio L, Dascola I, Umiltà C. Reorienting attention across the horizontal and vertical meridians: evidence in favor of a premotor theory of attention. Neuropsychologia. 1987;25:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(87)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubichi S, Nicoletti R, Umiltà C, Zorzi M. Response strategies and the Simon effect. Psychol Res. 2000;63:129–136. doi: 10.1007/pl00008171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schall JD, Hanes DP. Neural basis of saccade target selection in frontal eye field during visual search. Nature. 1993;366:467–469. doi: 10.1038/366467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherberger H, Andersen RA. Target selection signals for arm reaching in the posterior parietal cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2001–2012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4274-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherberger H, Goodale MA, Andersen RA. Target selection for reaching and saccades share a similar behavioral reference frame in the macaque. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:1456–1466. doi: 10.1152/jn.00883.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SH, Gribble PL, Graham KM, Cabel DW. Dissociation between hand motion and population vectors from neural activity in motor cortex. Nature. 2001;413:161–165. doi: 10.1038/35093102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SH, Kalaska JF. Reaching movements with similar hand paths but different arm orientations. I. Activity of individual cells in motor cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:826–853. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.2.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheliga BM, Riggio L, Rizzolatti G. Orienting of attention and eye-movements. Exp Brain Res. 1994;98:507–522. doi: 10.1007/BF00233988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheliga BM, Riggio L, Rizzolatti G. Spatial attention and eye movements. Exp Brain Res. 1995;105:261–275. doi: 10.1007/BF00240962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Alexander GE. Neural correlates of a spatial sensory-to-motor transformation in primary motor cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1171–1194. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit AC, Van Gisbergen JA. An analysis of curvature in fast and slow human saccades. Exp Brain Res. 1990;81:335–345. doi: 10.1007/BF00228124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder LH, Batista AP, Andersen RA. Coding of intention in the posterior parietal cortex. Nature. 1997;386:167–170. doi: 10.1038/386167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder LH, Batista AP, Andersen RA. Change in motor plan without a change in the spatial locus of attention modulates activity in posterior parietal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:2814–2819. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soechting JF, Engel KC, Flanders M. The Duncker illusion and eye-hand coordination. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:843–854. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.2.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JH, Nakayama K. Role of focal attention on latencies and trajectories of visually guided manual pointing. J Vis. 2006;6:982–995. doi: 10.1167/6.9.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JH, Nakayama K. Automatic adjustment of visuomotor readiness. J Vis. 2007a;7:1–9. doi: 10.1167/7.5.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JH, Nakayama K. Fixation offset facilitates saccades and manual reaching for single but not multiple target displays. Exp Brain Res. 2007b;177:223–232. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0667-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor TE, Lupker SJ. Sequential effects in naming: a time-criterion account. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2001;27:117–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson KG, Biscoe KL, Sato TR. Neuronal basis of covert spatial attention in the frontal eye field. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9479–9487. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0741-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson KG, Hanes DP, Bichot NP, Schall JD. Perceptual and motor processing stages identified in the activity of macaque frontal eye field neurons during visual search. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:4040–4055. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.4040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipper SP, Howard LA, Houghton G. Action-based mechanisms of attention. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998;353:1385–1383. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipper SP, Howard LA, Houghton G. Behavioral consequences of selection from neural population codes. In: Monsell S, Driver J, editors. Attention and Performance XVII: Control of Cognitive Processes. Boston: MIT Press; 2000. pp. 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- Tipper SP, Lortie C, Baylis GC. Selective reaching: evidence for action-centered attention. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 1992;18:891–905. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.18.4.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R, Haggard P, McSorley E. The control of saccade trajectories: direction of curvature depends on advanced knowledge of target location. Percept Pyschophys. 2006;68:129–138. doi: 10.3758/bf03193663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh TN, Elliot D. Effects of response priming and inhibition on movement planning and execution. J Mot Behav. 2004;36:200–211. doi: 10.3200/JMBR.36.2.200-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh TN, Elliot D. The effects of response priming on the planning and execution of goal-directed movements in the presence of a distracting stimulus. Acta Psychol (Amst) 2005;119:123–142. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise SP, Boussaoud D, Johnson PB, Caminiti R. Premotor and parietal cortex: corticocortical connectivity and combinatorial computations. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:25–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise SP, di Pellegrino G, Boussaoud D. The premotor cortex and nonstandard sensorimotor mapping. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996;74:469–482. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-74-4-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]