Abstract

HIV-infected humans and SIV-infected rhesus macaques experience a rapid and dramatic loss of mucosal CD4+ T cells that is considered to be a key determinant of AIDS pathogenesis. In this study, we show that nonpathogenic SIV infection of sooty mangabeys (SMs), a natural host species for SIV, is also associated with an early, severe, and persistent depletion of memory CD4+ T cells from the intestinal and respiratory mucosa. Importantly, the kinetics of the loss of mucosal CD4+ T cells in SMs is similar to that of SIVmac239-infected rhesus macaques. Although the nonpathogenic SIV infection of SMs induces the same pattern of mucosal target cell depletion observed during pathogenic HIV/SIV infections, the depletion in SMs occurs in the context of limited local and systemic immune activation and can be reverted if virus replication is suppressed by antiretroviral treatment. These results indicate that a profound depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells is not sufficient per se to induce loss of mucosal immunity and disease progression during a primate lentiviral infection. We propose that, in the disease-resistant SIV-infected SMs, evolutionary adaptation to both preserve immune function with fewer mucosal CD4+ T cells and attenuate the immune activation that follows acute viral infection protect these animals from progressing to AIDS.

A series of elegant studies conducted recently in HIV-infected humans and SIV-infected rhesus macaques (RMs,3 Macaca mulatta) has shown that these pathogenic lentiviral infections are consistently associated with an early, severe, and persistent depletion of memory CD4+CCR5+ T cells in mucosal-associated lymphoid tissues (MALT) (1–6). These studies led to the formulation of a pathogenic model of HIV/SIV infection whereby the loss of mucosal CD4+ Th cells causes a breakdown of the mucosal barrier, thus increasing a patient's susceptibility to systemic microbial translocation from the gastrointestinal tract (7). These microbial products may then contribute to the chronic generalized immune activation observed during pathogenic HIV and SIV infections. Ultimately, this early and persistent failure of the mucosal immune system is thought to result in the eventual collapse of the immune system that is associated with full-blown AIDS (7–10).

Important insights into the pathogenesis of HIV infection have been provided by studies of nonpathogenic SIV infection of natural host species, such as sooty mangabeys (SMs), African green monkeys, mandrills, and others. SMs (Cercocebus atys) are West African monkeys that are commonly infected with SIV both in the wild and in captivity; in these animals, the infection appears to be acquired at the time of sexual maturity (11). Natural SIV infection of SMs is particularly relevant for two main reasons: first, SIVsmm, the virus found in SMs, is the origin of the HIV-2 epidemic in humans (12), and second, SIVsmm was used to generate the various RM-adapted SIVmac viruses (e.g., SIVmac239, SIVmac251) that are often used for studies of AIDS pathogenesis and vaccines (13). The most intriguing feature of naturally SIV-infected SMs is that, unlike HIV/SIV-infected humans and RMs, these animals typically remain asymptomatic and do not progress to AIDS despite levels of plasma viremia that are as high, or even higher, than those observed in HIV-infected patients (14, 15). Although the mechanism(s) underlying the lack of disease progression in SMs is still unknown, our previous studies have shown that a characteristic feature of this infection is the overall preservation of peripheral blood (PB) CD4+ T cell homeostasis that occurs in the absence of the chronic immune activation, bystander T cell apoptosis, and cell cycle dysregulation that are associated with pathogenic primate lentiviral infections (15–19).

In this study, we report the results of the first comprehensive study of the MALT in SIV-infected SMs, during both chronic natural and acute experimental infection. This study involved an extensive cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis of the MALT by sampling the respiratory mucosa via bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and the intestinal mucosa via rectal biopsy (RB). We observed that nonpathogenic SIV infection of SMs is associated with rapid, severe, and persistent CD4+ T cell depletion at mucosal sites, the extent of which is comparable to what has been described in pathogenic HIV/SIV infections. However, in the context of low levels of systemic and mucosal immune activation, SIV-infected SMs do not progress to AIDS despite this depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Eighteen naturally SIV-infected, 2 experimentally SIV-infected, and 13 uninfected SMs were included in the cross-sectional analysis. Based on their age at the time of sampling and the age at which most SMs acquire SIV, we estimated that average length of infection in the naturally SIV-infected SMs included in this study was of 8.5 years. Blood collection was performed by venipuncture. Local animal care and use committee and National Institutes of Health protocols were strictly followed. All animals were housed at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center.

Experimental SIV infection

Infection of five SMs with uncloned SIVsmm has been conducted, as previously described (16, 20). Briefly, each animal was i.v. inoculated with 1 ml of plasma from an experimentally SIVsmm-infected SM sampled at day 11 postinfection. In addition, five RMs were i.v. infected with 1 ml of uncloned SIVsmm and five were i.v. infected with 10,000 50% tissue culture-infective dose of SIVmac239. High-dose SIVmac239 was used to ensure fully pathogenic infection in RMs.

Antiretroviral therapy

Six naturally SIV-infected SMs were treated with 9-R-(2-phosphonomethoxypropyl) adenine (PMPA, tenofovir) and β-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thia-5-fluorocytidine (FTC, emtricitabine) for 6 wk. Both drugs were administered s.c. at the dose of 30 mg/kg/day. PMPA and FTC were provided by Gilead.

Lymph node (LN) biopsy, RB, and BAL

For LN biopsy, animals were anesthetized with Ketamine or Telazol; the skin over the axillary or inguinal region was clipped and surgically prepped. An incision was made over the LN, which was exposed by blunt dissection and excised over clamps. LN biopsies were homogenized and passed through a 70-μm cell strainer to mechanically isolate lymphocytes. For RB, fecal material was removed from the rectum, and a rectal scope/sigmoidoscope was then placed a short distance into the rectum. RB were obtained with biopsy forceps and placed in tissue culture fluid for immunophenotypical studies. Isolation of lymphocytes from RB was performed, as described previously (19). For BAL, a fiber-optic bronchoscope was placed into the trachea after local anesthetic was applied to the larynx. The scope was directed into the right primary bronchus and wedged into a distal subsegmental bronchus. Up to three 35-ml aliquots of warmed normal saline were instilled, and the saline was collected by aspiration between each individual lavage before a new aliquot was instilled. Immunophenotypical studies were performed by multicolor flow cytometry (as detailed below) on mononuclear cells derived from LN, RB, and BAL (19). In all cases, cells were stained the day of sampling.

Viral load

SIV plasma viral load was determined, as previously described (15).

Immunophenotyping by flow cytometry

Seven-color flow cytometric analysis was performed on whole blood samples according to standard procedures and using a panel of mAbs that were originally designed to detect human molecules, but that we and others have shown to be cross-reactive with SMs and RMs (15). The Abs used were as follows: anti-CD4 PerCP (clone L200), anti-CD4 FITC (clone L200), anti-CD8 Pacific Blue (clone RPA-T8), anti-CD25 PECy7 (clone 2A3), Ki67 FITC (clone B56), anti-CD3 Alexa 700 (clone SP34−2), anti-CD69 PerCP (clone L78), anti-CD95 allophycocyanin (clone DX2), and anti-HLA-DR PerCP (clone G46−6) (all from BD Pharmingen); anti-CD127 PE (clone R34.34) (from Beckman Coulter); and anti-CD28 PECy7 (clone 28.2) (from eBioscience). Samples assessed for Ki67 were surface stained first with the appropriate Abs, then fixed and permeabilized using BD Perm 2 (BD Pharmingen), and stained intracellularly with Ki67. Flow cytometric acquisition and analysis of samples were performed on at least 100,000 events on a LSRII flow cytometer driven by the DiVa software package (BD Biosciences). Analysis of the acquired data was performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Immunohistochemistry

General intestinal architecture was assessed following H&E staining. To detect CD4+ T cells, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were immunostained, as described previously (21).

LPS levels

Plasma samples were diluted 5-fold with endotoxin-free water and then heated to 70°C for 10 min to inactivate plasma proteins. Plasma LPS was then quantified with a commercially available Limulus amebocyte assay (Cambrex), according to manufacturer's protocol. Each sample was run in duplicate.

Statistical analyses

The Mann-Whitney U test was performed using Prism 4.0 software. In addition, we used the Dixon's Q test to identify statistical outliers.

Results

CD4+ T cell depletion in MALT of naturally SIV-infected SMs

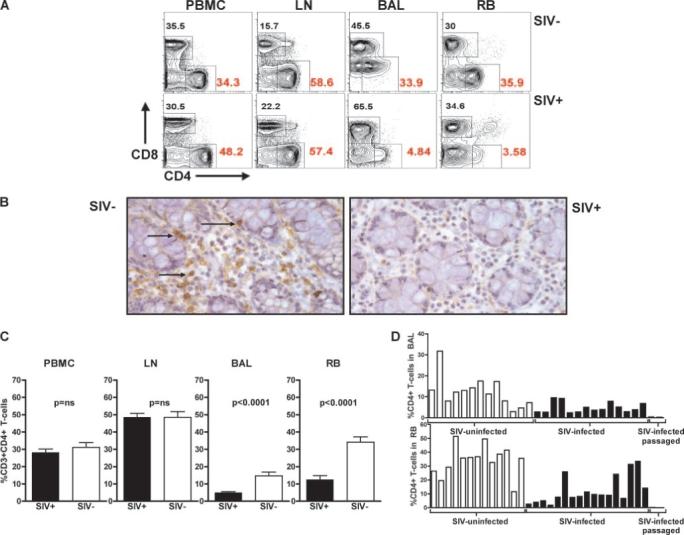

We first performed a cross-sectional analysis of the phenotype of T cells isolated from PB, LN, and MALT (specifically, RB and BAL). We studied 18 naturally and 2 experimentally SIV-infected SMs (all tested during the chronic phase of infection), as well as 13 uninfected animals. Importantly, all animals studied remained asymptomatic throughout the follow-up period. Fig. 1A shows a comparative flow cytometric measurement of the percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in PB, LN, BAL, and RB of one representative SIV-infected SM and one uninfected SM (pregated on CD3+ cells). Fig. 1B confirms, using immunohistochemical staining for CD4 in rectal tissue, the depletion of CD4+ T cells in the intestinal lamina propria of SIV-infected SMs. A summary of this cross-sectional analysis in Fig. 1C demonstrates that, whereas the percentage of CD4+ T cells in PB and LN is similar in SIV-infected and uninfected SMs, the percentage of CD4+ T cells in both BAL and RB is significantly lower in SIV-infected SMs as compared with uninfected SMs. Fig. 1D shows the percentage of mucosal CD4+ T cells in each of the studied animals, and indicates that the severity of mucosal CD4+ T cell depletion in infected SMs approximates that observed in HIV-infected patients (2). Interestingly, an even more dramatic depletion of MALT CD4+ T cells (i.e., to <0.5% of total T cells; Fig. 1D) was observed in two persistently asymptomatic SMs that were experimentally infected via SIV passage from a naturally infected SM and that developed systemic CD4+ T cell depletion coincident with expanded SIV coreceptor tropism (33). In all, these results indicate that nonpathogenic SIV infection of SMs is associated with a significant depletion of MALT CD4+ T cells that is, however, not followed by progression to AIDS.

FIGURE 1.

Depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cell during nonpathogenic SIV infection of SMs. A, Representative flow cytometric contour plots showing the percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the PB (PBMCs), LN, BAL, and RB of an uninfected (top panels) and an SIV-infected (bottom panels) SM. All contour plots are pregated on CD3+ T cells. B, Immunohistochemical stain for CD4 (brown, see arrows) in the rectal mucosa of a representative uninfected SM (left) and SIV-infected SM (right). C, Percentage of CD4+ T cells in the PBMCs, LN, BAL, and RB of 18 naturally SIV-infected (■) and 13 uninfected (□) SMs, as determined by flow cytometry. Values of p were determined by the Mann-Whitney U test. D, Percentage of CD4+ T cells in the BAL (top) and RB (bottom) in each of the 33 SMs included in this study. At the extreme right of the bar graphs are the data relative to two experimentally SIV-infected SMs that experienced generalized CD4+ T cell depletion in association with expanded cell tropism, but remained asymptomatic for >4 years. These latter two animals were inoculated with 1 ml of plasma passaged from a naturally SIV-infected SM with high virus replication.

Limited immune activation in the mucosa of chronically SIV-infected SMs

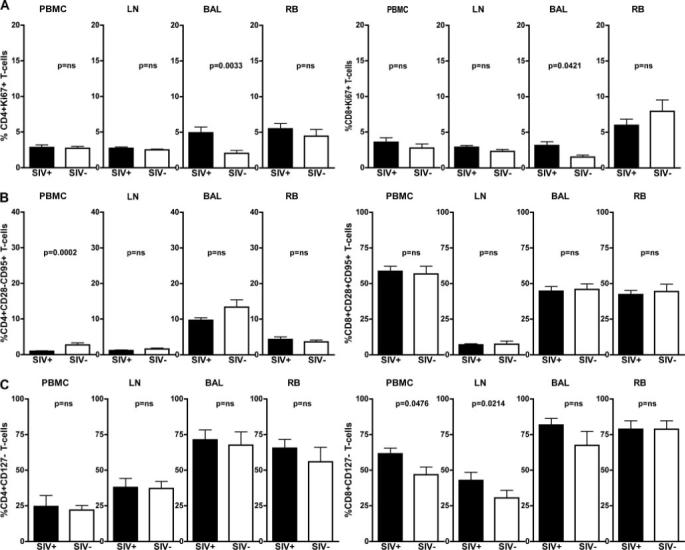

In contrast to HIV-infected patients, SIV-infected SMs exhibit low levels of systemic T cell activation, proliferation, and bystander apoptosis during chronic infection. To assess the level of T cell activation in the MALT during natural SIV infection of SMs, we measured the fraction of proliferating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing Ki67 as well as the fraction of T cells expressing markers of an activated effector phenotype, i.e., loss of the costimulatory molecule CD28 with up-regulation of the apoptosis-related marker CD95 or loss of the IL-7R α-chain CD127 (Fig. 2). Consistent with our previous observations in uninfected SMs (19), the majority of mucosal T cells display a memory or effector phenotype in both SIV-infected and uninfected SMs. Fig. 2A shows a moderate, but significant increase in the level of proliferating T cells in the lungs, but not in the intestines, of SIV-infected animals compared with uninfected animals. It should be noted that the level of Ki67+ T cells in the BAL of naturally SIV-infected SMs (an average of 4.93% for CD4+ T cells and 3.14% for CD8+ T cells) is much lower than what has been described in SIV-infected RMs (6, 22). Importantly, we did not find any significant differences in the percentage of mucosal CD28−CD95+ or CD127− effector CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in SIV-infected SMs compared with uninfected controls (Fig. 2, B and C). Taken together, these data indicate that, with the exception of a moderate increase in Ki67+ T cells isolated from BAL, natural SIV infection of SMs is not associated with any major changes in the levels of T cell proliferation or activation in the MALT.

FIGURE 2.

Depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells in SIV-infected SMs is not associated with increased mucosal or systemic immune activation. T cells isolated from blood (PBMCs), LN, BAL, and RB of 18 naturally SIV-infected (■) and 13 uninfected (□) SMs were assessed for their levels of immune activation and proliferation. A, Percentage of CD4+Ki67+ (top left) and CD8+Ki67+ (top right) as determined by flow cytometry; p values were determined by the Mann-Whitney U test. B, Percentage of effector (i.e., CD95+CD28−) CD4+ (middle left) and CD8+ (middle right) T cells as determined by flow cytometry; p values were determined by the Mann-Whitney U test. C, Percentage of CD4+CD127− (bottom left) and CD8+CD127− (bottom right) as determined by flow cytometry; p values as determined by the Mann-Whitney U test.

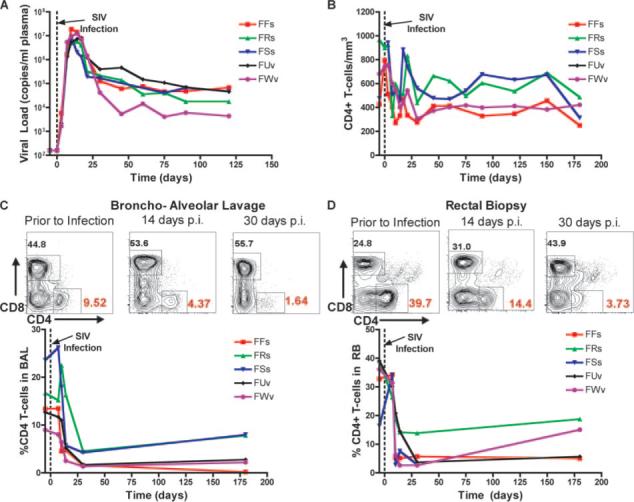

Experimental SIV infection induces an early, severe, and persistent depletion of CD4+ T cells

To better define the kinetics of the mucosal CD4+ T cell depletion observed in naturally SIV-infected SMs, we experimentally infected five SMs via i.v. inoculation of 1 ml of plasma from a SIV-infected SM (as previously described (18)). Similar to earlier observations (18, 20), all animals remained asymptomatic throughout the follow-up period of 365 days, showed peak plasma viral loads in the range of 106−108 copies/ml, and attained viral set-point levels by day 60 postinfection in the range of 104−106 copies/ml plasma (Fig. 3A). Experimentally SIV-infected SMs exhibited a relatively minor initial decline in the level of circulating CD4+ T cells in PB that plateaued after 2−3 wk of infection and was maintained during the next 6 mo at levels ranging from 50 to 90% of the preinfection CD4+ T cell counts (Fig. 3B). Fig. 3C shows flow cytometric contour plots describing the sharp decline of CD4+ T cells in the lungs (BAL) and intestines (RB) at days 14 and 30 postinfection in one representative experimentally SIV-infected SM, and Fig. 3D shows a longitudinal analysis of CD4+ T cell levels in these mucosal tissues in the first 6 mo postinfection. In striking contrast to what we observed in PB, SIV infection of SMs is associated with a rapid, severe (50 −95%), and persistent depletion of CD4+ T cells in both the lung and the intestine. The observed depletion in the MALT involves both memory (CD28+CD95+) and effector (CD28−CD95+) CD4+ T cells (data not shown). It should be noted that these results are consistent with the finding that a dramatic depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells follows acute SIVagm infection of another natural host species for SIV, the African green monkey (23).

FIGURE 3.

Experimental SIV infection of SMs induces severe and persistent depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells. A, Plasma viral load expressed as copies/ml plasma in five experimentally infected SMs designated FFs, FRs, FUv, FSs, and FWv (top left). B, Longitudinal analysis of the number of CD4+ T cells/mm3 PB in the animals shown in A (top right). C and D, Representative contour plots show the fraction of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the mucosa before and 14 and 30 days post-SIV infection all contour plots are pregated on CD3+ cells. Longitudinal analysis of the percentage of CD4+ T cells in BAL (C, bottom left) and RB (D, bottom right). The x-axis shows the time postinfection (days).

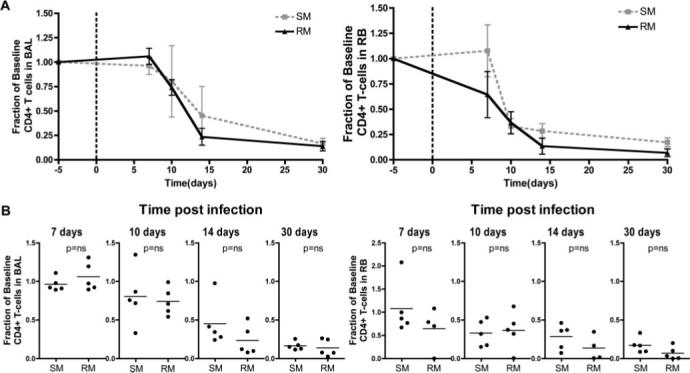

Comparison of the kinetics of acute mucosal CD4+ T cell depletion in pathogenic and nonpathogenic SIV infections

To directly compare the magnitude and kinetics of mucosal CD4+ T cell depletion in the acute setting in both nonpathogenic and pathogenic SIV infection of SMs and RMs, respectively, we next examined the kinetics of mucosal CD4+ T cell depletion in five RMs experimentally infected with 10,000 50% tissue culture-infective dose i.v. of SIVmac239. Consistent with previous studies (3, 4, 6), experimental SIV infection of RMs was associated with a rapid and extensive loss of mucosal CD4+ T cells (data not shown). To compare the level of the mucosal CD4+ T cell depletion in SIV-infected SMs and RMs, we plotted the level of CD4+ T cells at each time point postinfection as a fraction of the preinfection (baseline). As shown in Fig. 4A, this analysis revealed that changes in the percentages of mucosal CD4+ T cells following SIV infection are remarkably similar when comparing the pathogenic RM model with the nonpathogenic SM model. Importantly, the average fractional loss of CD4+ T cells was not significantly different between SMs and RMs at any time during acute infection (Fig. 4B). In addition, we found no difference between SMs and RMs in the mean level of residual CD4+ T cells found in BAL or RB at 30 days postinfection, i.e., the time when maximal depletion had been reached in all animals (data not shown). It should also be noted, however, that one of the five SIVmac239-infected RMs showed a very profound CD4+ T cell depletion (<0.3% of CD3+ T cells expressing CD4 by 7 days postinfection) that was not observed in any of the experimentally infected SMs. In all, these data indicate that nonpathogenic SIV infection of SMs is similar to pathogenic HIV/SIV infections of humans and RMs in terms of the pattern and kinetics of mucosal target cell depletion, because each are associated with an early, severe, and persistent loss of memory and effector CD4+ T cells in mucosal tissues.

FIGURE 4.

Kinetics of CD4+ T cell depletion during the acute phase of SIV infection of SMs and RMs. A, Fractional changes in CD4+ T cells relative to baseline in BAL and RB from experimentally SIVsmm-infected SMs and SIVmac239-infected RMs. B, Comparison of the fraction of baseline mucosal CD4+ T cells in SMs and RMs sampled at 7, 10, 14, and 30 days postinfection. Statistical analysis performed using the Mann-Whitney U test.

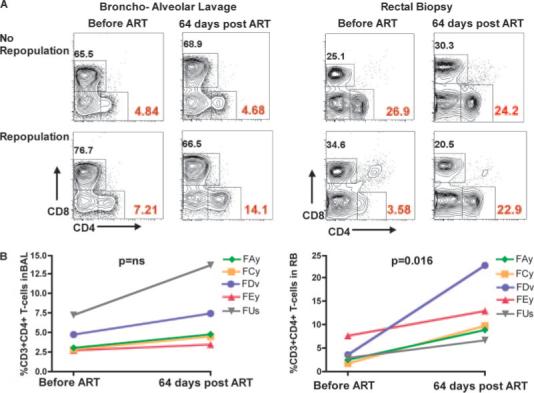

Potent antiretroviral therapy induces reconstitution of mucosal CD4+ T cells in chronically SIV-infected SMs

We next sought to assess the relationship between mucosal CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in naturally SIV-infected SMs by treating six animals with a potent antiretroviral regimen, including PMPA (tenofovir) and FTC (emtricitabine) for 6 wk (30 mg/kg/day each). In all treated animals, PMPA and FTC induced a rapid decline of plasma viremia, with five of six SMs suppressing viral load below the limit of detection (i.e., 80 copies/ml plasma) by day 28 and one animal showing a >2-log decline at the same time point (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 5, a variable degree of mucosal CD4+ T cell repopulation was observed in the treated SIV-infected SMs. Representative flow cytometric contour plots of the animal with the greatest fractional increase of mucosal CD4+ T cells and the only animal with no increase are displayed in Fig. 5A. This SIV-infected SM (FVs) with no CD4+ T cell repopulation detected via RB (and very little detected via BAL) was identified as an outlier with respect to the baseline CD4+ T cell level (using Dixon's Q test) and thus was excluded from further analyses. Fig. 5B shows the pre- and posttreatment percentage of mucosal CD4+ T cells in the five remaining animals, with a significant ( p = 0.016) increase in CD4+ T cells observed in the intestine. Although four of five treated SIV-infected SMs demonstrated a >50% increase in BAL-derived CD4+ T cells, this increase was not statistically significant ( p = 0.15). It should be noted that the lowest amounts of mucosal CD4+ T cell repopulation were observed in the two SMs with the highest baseline levels before therapy. As such, these results suggest that, in SIV-infected SMs with suppressed virus replication, the low levels of mucosal immune activation and the absence of systemic immune dysfunction may favor homeostatic mechanisms designed to reconstitute the pool of mucosal CD4+ T cells.

FIGURE 5.

Antiretroviral therapy induces variable, but significant mucosal CD4+ T cell reconstitution in naturally SIV-infected SMs. A, Representative flow cytometric contour plots showing the percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the BAL (left panels) and RB (right panels) of two naturally SIV-infected SMs before and at day 64 after initiation of antiretroviral therapy with PMPA and FTC. All contour plots are pregated on CD3+ T cells. The two animals were selected as representative of a minimal (top panels) or major (bottom panels) repopulation of MALT CD4+ T cells. B, Percentage of CD4+ T cells in the BAL (left) and RB (right) of five naturally SIV-infected SMs measured at baseline and at day 64 after initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) as determined by flow cytometry.

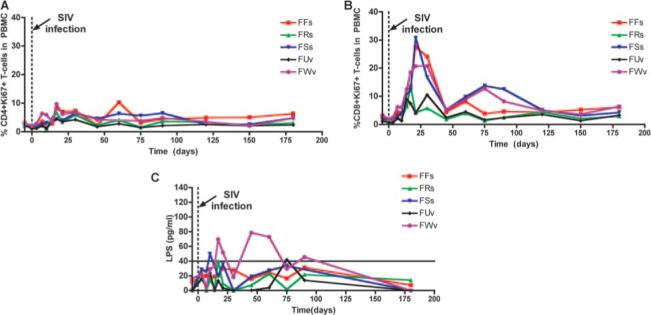

Transient systemic immune activation and microbial translocation during acute SIV infection of SMs

We next assessed the level of systemic immune activation following experimental SIV infection of SMs by performing a longitudinal study of the level of proliferating T cells in the blood of the five animals described in Fig. 3. We found that this cohort of experimentally SIV-infected SMs showed an early, yet transient wave of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation (Fig. 6, A and B) despite continuously high levels of virus replication and persistent MALT CD4+ T cell depletion (Fig. 3). It should be noted that the level of T cell proliferation observed during primary SIV infection in this group of SMs is higher than what we observed in a previous study (18), possibly due to different sampling schedules.

FIGURE 6.

Transient systemic activation and microbial translocation during primary SIV infection of SMs. A and B, Longitudinal analysis of the percentage of circulating CD4+ (A, left) and CD8+ (B, right) T cells that express the proliferation marker Ki67 during primary SIV infection of SMs. The x-axis shows the time postinfection (days). C, Longitudinal analysis of the plasma levels of LPS in the same animals depicted in Fig. 3. The x-axis shows the time postinfection (days).

Increased plasma levels of LPS, a component of Gram-negative bacteria, have been used as a marker of the loss of mucosal barrier integrity and consequent systemic microbial translocation described in pathogenic HIV and SIV infections (24). According to this model, microbial translocation from the intestine to the bloodstream plays a key role in establishing the chronic generalized immune activation associated with disease progression. To determine whether the rapid and severe loss of mucosal CD4+ T cells that we observed during primary SIV infection of SMs results in a loss of mucosal immune function, we measured longitudinally the plasma levels of LPS in the five experimentally infected SMs. As shown in Fig. 6C, two SMs (FWv and FSs) manifested a transient increase in plasma LPS levels above 40 pg/ml (considered to be the upper limit of normal) during the first few weeks of infection, consistent with a temporary loss of mucosal barrier integrity. Intriguingly, these two SMs were also found to have the most profound CD4+ T cell depletion in the intestine in the acute phase of infection (Fig. 3D). In all, these results suggest that the rapid and severe loss of mucosal CD4+ T cells that occurs during primary SIV infection of SMs can, at least in some cases, induce a transient loss of mucosal integrity that is temporally associated with an increase in systemic (Fig. 6, A and B) and local (data not shown) immune activation. Alternatively, depletion of MALT CD4+ T cells and transient loss of mucosal integrity may be covariates that both relate to SIV replication in the intestinal mucosa, which causes the destruction of CD4+ T cells as well as damage to epithelial cells.

Discussion

In this study, we describe the results of the first analysis of the mucosal immune system during nonpathogenic SIV infection of natural hosts, the SMs. A series of studies of pathogenic HIV infection of humans and SIVmac infection of RMs focused on the role of the early depletion of mucosal memory CD4+ T cells in AIDS pathogenesis (1–6). Although it is still unclear to what extent direct virus infection (4) vs bystander death of uninfected CD4+ T cells (3) is the cause of this depletion, there is ample consensus that this rapid and dramatic loss of Th cells leads to a progressive state of mucosal dysfunction that, in turn, contributes to both the generalized immune activation and systemic loss of CD4+ T cells that are closely associated with clinical progression to AIDS (7–10, 25, 26).

Fascinatingly, and somewhat unexpectedly, we found that nonpathogenic SIV infection of SMs is consistently associated, both during the acute phase of experimental infection and the chronic phase of natural infection, with a significant depletion of CD4+ T cells in the MALT. It is particularly remarkable that the level of mucosal CD4+ T cell depletion observed in chronically SIV-infected SMs is very similar to that of chronically HIV-infected patients (2, 5, 27), and that the kinetics of the mucosal CD4+ T cell decline during primary infection is comparable in SIVsmm-infected SMs and RMs infected with high doses of the highly pathogenic SIVmac239 virus (Fig. 4). However, in stark contrast to pathogenic HIV and SIV infections, the depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells seen in SMs is not associated with either the progressive systemic depletion of CD4+ T cells or the presence of generalized immune activation that are typical of pathogenic HIV/SIV infection. The lack of mucosal immune activation in SIV-infected SMs (Fig. 2), even in the presence of lower levels of CD4+ T cells, may in part explain why suppression of viral replication seems to lead to a more rapid reconstitution of mucosal CD4+ T cells in SMs (Fig. 5) than what has been reported in HIV-infected humans (1, 27–29). An intriguing potential implication of these findings is that the reconstitution of the pool of MALT CD4+ T cells in HIV-infected humans may be achieved sooner or more efficiently if treatments targeting chronic immune activation are added to those aimed at suppressing viral replication.

In all, these findings indicate that the main difference at the level of mucosal immunity between pathogenic and nonpathogenic primate lentiviral infections is not the kinetics or amount of CD4+ T cell depletion, but rather the level of local and systemic immune activation. We emphasize that these results provide, in and of themselves, important insights into the key question regarding naturally SIV-infected SMs, i.e., how do they avoid AIDS despite many years of infection with a highly replicating virus? Indeed, these new observations confirm and better define the protective role of low levels of immune activation in preventing naturally SIV-infected SMs (and possibly other natural SIV hosts as well) from disease progression. Although our previous observations indicated that the low systemic immune activation protects SIV-infected SMs by preserving peripheral CD4+ T cell homeostasis (15), the current findings introduce the concept that, in this non-progressing model of infection, low levels of immune activation may be instrumental to maintain normal mucosal immune function in the context of a severe depletion of local memory CD4+ T cells. Importantly, the realization that the homeostasis of MALT CD4+ T cells is, in fact, disrupted during nonpathogenic SIV infection is not consistent with the hypothesis that the loss of MALT CD4+ T cells is necessary and sufficient for the development of AIDS (7–10), but rather indicates that other insult(s) may be required. The real question then becomes the following: what protects SIV-infected SMs from progressing to AIDS in the setting of a major depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells?

One possible mechanism is that, in SMs (and possibly other natural hosts), but not in humans or RMs, the residual MALT CD4+ T cells are sufficient to maintain the overall function of the mucosal immune system. This could be postulated to be the result of thousands of years of evolutionary pressure placed upon SMs by natural SIV infection, causing them to adapt to tolerate levels of mucosal CD4+ T cell depletion that would be associated with disease progression in HIV-infected humans (2). The lack of systemic immune activation observed in chronically SIV-infected SMs may thus be a consequence of the preserved integrity of the mucosal barrier provided by a reduced, but still sufficient pool of CD4+ T cells. The recent finding that, in the chronic phase, naturally SIV-infected SMs do not exhibit the increased level of plasma LPS observed in HIV-infected individuals is consistent with an intact mucosal barrier and the absence of persistent transluminal microbial translocation in these animals (24). In contrast, the transient increases in plasma LPS that we observed during the acute phase of SIV infection of the two SMs with the most profound depletion of local CD4+ T cells suggest that a transient interruption of the mucosal barrier can occur even in AIDS-resistant natural hosts, most likely as a consequence of the local loss of CD4+ T cells. The fact that the systemic bacterial translocation in these two animals was unsustained even though their mucosal CD4+ T cell levels remained low at all time points again indicates that mucosal immune function and mucosal integrity are maintained in chronically SIV-infected SMs despite local CD4+ T cell depletion. In this context, it will be interesting to determine, in future studies, whether SIV infection of SMs is associated with preserved function of intestinal epithelial cells.

In a recent report, we showed that mucosal CD4+ T cells isolated from SMs as well as other natural SIV hosts (i.e., mandrills, sun-tailed monkeys, and African green monkeys) express low levels of CCR5 (30). Despite this finding, other lines of evidence indicate that SM CD4+ T cells are readily infected in vivo and in vitro despite low CCR5 expression (G. Silvestri, unpublished observations). Explanation for this apparent discrepancy includes the following possibilities: 1) cells that are defined CCR5 negative by flow cytometry may in fact express a sufficient number of this coreceptor on their surface for infection, and/or 2) SIVsmm may use other coreceptors in vivo, thus allowing for our current observation that the majority of mucosal CD4+ T cells are depleted during SIV infection of SMs.

In HIV-infected individuals, the pathogenic role of the aberrant and generalized immune activation that typically follows infection is multifaceted, and includes the following: 1) the creation of additional targets for virus replication (activated CD4+ T cells); 2) the loss of bystander, uninfected T cells via activation-induced apoptosis; and 3) the generation of a proinflammatory environment that may affect the overall immune function above and beyond the loss of CD4+ T cells (31, 32). In SIV-infected SMs, the limited immune activation may favor the preservation of the mucosal immune barrier (and thus its resistance to further microbial translocation) by avoiding a dangerous cycle of mucosal immune activation, increased virus replication, further mucosal CD4+ T cell depletion, and progressive loss of mucosal integrity that would ultimately promote a state of chronic, systemic immune activation.

Taken as a whole, these results indicate that natural, nonpathogenic SIV infection of SMs results in a similar pattern of mucosal target cell depletion as pathogenic infections of humans and RMs. However, in striking contrast to pathogenic HIV and SIV infections, the depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells observed in SIV-infected SMs is not associated with any signs of immune dysfunction and clinical illness. This observation indicates that a profound depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells is not sufficient per se to induce loss of mucosal immunity during a primate lentiviral infection, and that additional factors, particularly an increase in the local level of immune activation, may be required to initiate the disease process that ultimately leads to systemic immunodeficiency. We propose that, in the disease-resistant SIV-infected SMs, evolutionary adaptation both to preserve mucosal immune function in the presence of fewer CD4+ T cells and to attenuate the mucosal and systemic immune activation are mechanisms protecting these animals from progression to AIDS despite an early, severe, and persistent depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Stephanie Ehnert and all the animal care and veterinary staff at the Yerkes National Primate Center, as well as Benton Lawson and the Virology Core of the Emory Center for AIDS Research. We are thankful to Drs. Mark Feinberg, Ashley Haase, Eric Hunter, Amitinder Kaur, Louis Picker, Sarah Ratcliffe, Mario Roederer, and Ronald Veazey for helpful comments and discussions, and to Dr. Ann Chahroudi for critical review of this manuscript. PMPA and FTC were provided by Gilead.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 AI052755 and AI066998 (to G.S.), R01 HL075766 (to S.I.S.), R01 AI035522 and R21 AI060451 (to D.L.S.), R01 AI064066 (to I.V.P.), and RR-00165 (Yerkes National Primate Research Center). S.N.G. was supported by Grant 1F31AI066400-01A1; J.M.M. was supported in part by a training grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 5 T32 AI 07520.

Abbreviations used in this paper: RM, rhesus macaques; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; FTC, β-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thia-5-fluorocytidine; LN, lymph node; MALT, mucosal-associated lymphoid tissues; PB, peripheral blood; PMPA, 9-R-(2-phosphonomethoxypropyl) adenine; RB, rectal biopsy; SM, sooty mangabey.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Guadalupe M, Reay E, Sankaran S, Prindiville T, Flamm J, McNeil A, Dandekar S. Severe CD4+ T-cell depletion in gut lymphoid tissue during primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and substantial delay in restoration following highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 2003;77:11708–11717. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11708-11717.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenchley JM, Schacker TW, Ruff LE, Price DA, Taylor JH, Beilman GJ, Nguyen PL, Khoruts A, Larson M, Haase AT, Douek DC. CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:749–759. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Q, Duan L, Estes JD, Ma ZM, Rourke T, Wang Y, Reilly C, Carlis J, Miller CJ, Haase AT. Peak SIV replication in resting memory CD4+ T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. Nature. 2005;434:1148–1152. doi: 10.1038/nature03513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattapallil JJ, Douek DC, Hill B, Nishimura Y, Martin M, Roederer M. Massive infection and loss of memory CD4+ T cells in multiple tissues during acute SIV infection. Nature. 2005;434:1093–1097. doi: 10.1038/nature03501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehandru S, Poles MA, Tenner-Racz K, Horowitz A, Hurley A, Hogan C, Boden D, Racz P, Markowitz M. Primary HIV-1 infection is associated with preferential depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes from effector sites in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:761–770. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Picker LJ, Hagen SI, Lum R, Reed-Inderbitzin EF, Daly LM, Sylwester AW, Walker JM, Siess DC, Piatak M, Jr., Wang C, et al. Insufficient production and tissue delivery of CD4+ memory T cells in rapidly progressive simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:1299–1314. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Douek DC. HIV disease: fallout from a mucosal catastrophe? Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:235–239. doi: 10.1038/ni1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haase AT. Perils at mucosal front lines for HIV and SIV and their hosts. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:783–792. doi: 10.1038/nri1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Picker LJ, Watkins DI. HIV pathogenesis: the first cut is the deepest. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:430–432. doi: 10.1038/ni0505-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veazey RS, Lackner AA. HIV swiftly guts the immune system. Nat. Med. 2005;11:469–470. doi: 10.1038/nm0505-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fultz PN, Gordon TP, Anderson DC, McClure HM. Prevalence of natural infection with simian immunodeficiency virus and simian T-cell leukemia virus type I in a breeding colony of sooty mangabey monkeys. AIDS. 1990;4:619–625. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199007000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn BH, Shaw GM, De Cock KM, Sharp PM. AIDS as a zoonosis: scientific and public health implications. Science. 2000;287:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson PR, Hirsch VM. SIV infection of macaques as a model for AIDS pathogenesis. Int. Rev. Immunol. 1992;8:55–63. doi: 10.3109/08830189209056641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rey-Cuille MA, Berthier JL, Bomsel-Demontoy MC, Chaduc Y, Montagnier L, Hovanessian AG, Chakrabarti LA. Simian immunodeficiency virus replicates to high levels in sooty mangabeys without inducing disease. J. Virol. 1998;72:3872–3886. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3872-3886.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silvestri G, Sodora DL, Koup RA, Paiardini M, O'Neil SP, McClure HM, Staprans SI, Feinberg MB. Nonpathogenic SIV infection of sooty mangabeys is characterized by limited bystander immunopathology despite chronic high-level viremia. Immunity. 2003;18:441–452. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunham R, Pagliardini P, Gordon S, Sumpter B, Engram J, Moanna A, Paiardini M, Mandl JN, Lawson B, Garg S, et al. The AIDS-resistance of naturally SIV-infected sooty mangabeys is independent of cellular immunity to the virus. Blood. 2006;108:209–217. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paiardini M, Cervasi B, Sumpter B, McClure HM, Sodora DL, Magnani M, Staprans SI, Piedimonte G, Silvestri G. Perturbations of cell cycle control in T cells contribute to the different outcomes of simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus macaques and sooty mangabeys. J. Virol. 2006;80:634–642. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.634-642.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silvestri G, Fedanov A, Germon S, Kozyr N, Kaiser WJ, Garber DA, McClure H, Feinberg MB, Staprans SI. Divergent host responses during primary simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsm infection of natural sooty mangabey and nonnatural rhesus macaque hosts. J. Virol. 2005;79:4043–4054. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4043-4054.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sumpter B, Dunham R, Gordon S, Engram J, Hennessey M, Kinter A, Paiardini M, Cervasi B, Klatt N, McClure H, et al. Correlates of preserved CD4+ T-cell homeostasis during natural, non-pathogenic SIV infection of sooty mangabeys: implications for AIDS pathogenesis. J. Immunol. 2006;178:1680–1691. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muthukumar A, Zhou D, Paiardini M, Barry AP, Cole KS, McClure HM, Staprans SI, Silvestri G, Sodora DL. Timely triggering of homeo-static mechanisms involved in the regulation of T-cell levels in SIVsm-infected sooty mangabeys. Blood. 2005;106:3839–3845. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veazey RS, Tham IC, Mansfield KG, DeMaria M, Forand AE, Shvetz DE, Chalifoux LV, Sehgal PK, Lackner AA. Identifying the target cell in primary simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection: highly activated memory CD4+ T cells are rapidly eliminated in early SIV infection in vivo. J. Virol. 2000;74:57–64. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.57-64.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Picker LJ, Reed-Inderbitzin EF, Hagen SI, Edgar JB, Hansen SG, Legasse A, Planer S, Piatak M, Jr., Lifson JD, Maino VC, et al. IL-15 induces CD4 effector memory T cell production and tissue emigration in nonhuman primates. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:1514–1524. doi: 10.1172/JCI27564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pandrea I, Gautam R, Ribeiro RM, Brenchley JM, Butler IF, Pattison M, Rasmussen T, Marx PA, Silvestri G, Lackner AA, et al. Acute loss of intestinal CD4+ T cells is not predictive of simian immunodeficiency virus virulence. J. Immunol. 2007;179:3035–3046. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, Kazzaz Z, Bornstein E, Lambotte O, Altmann D, et al. Microbial trans-location is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat. Med. 2006;12:1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grossman Z, Meier-Schellersheim M, Paul WE, Picker LJ. Pathogenesis of HIV infection: what the virus spares is as important as what it destroys. Nat. Med. 2006;12:289–295. doi: 10.1038/nm1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson RP, Kaur A. HIV: viral blitzkrieg. Nature. 2005;434:1080–1081. doi: 10.1038/4341080a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehandru S, Poles MA, Tenner-Racz K, Jean-Pierre P, Manuelli V, Lopez P, Shet A, Low A, Mohri H, Boden D, et al. Lack of mucosal immune reconstitution during prolonged treatment of acute and early HIV-1 infection. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guadalupe M, Sankaran S, George MD, Reay E, Verhoeven D, Shacklett BL, Flamm J, Wegelin J, Prindiville T, Dandekar S. Viral suppression and immune restoration in the gastrointestinal mucosa of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients initiating therapy during primary or chronic infection. J. Virol. 2006;80:8236–8247. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00120-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brenchley JM, Schacker TW, Price DA, Larson M, Khoruts A, Beilman GJ, Haase AT, Douek DC. High frequencies of infected CD4+ T cells in the gastrointestinal tract is associated with poor mucosal immune reconstitution after HAART.; 13th Conference of Retrovirus and Opportunistic Infections.; Denver, CO. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandrea I, Apetrei C, Gordon SN, Barbercheck J, Dufour J, Bohm R, Sumpter BS, Roques P, Marx PA, Hirsch VM, et al. Paucity of CD4+CCR5+ T-cells is a typical feature of natural SIV hosts. Blood. 2007;109:1069–1076. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grossman Z, Meier-Schellersheim M, Sousa AE, Victorino RM, Paul WE. CD4+ T-cell depletion in HIV infection: are we closer to understanding the cause? Nat. Med. 2002;8:319–323. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCune JM. The dynamics of CD4+ T-cell depletion in HIV disease. Nature. 2001;410:974–979. doi: 10.1038/35073648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milush JM, Reeves JD, Gordon S, Zhou D, Muthukmar A, Kosub DA, Chacko E, Giavedoni L, Ibegbu CC, Cole KS, et al. Virally induced CD4+ T cell population is not sufficient to induce AIDS in a natural host. J. Immunol. 2007;179:3047–3056. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]