Abstract

A role for a deficit in transport actions of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) in hypertension is supported by the following: (1) diminished renal 20-HETE in Dahl-S rats; (2) altered salt- and furosemide-induced 20-HETE responses in salt-sensitive hypertensive subjects; and (3) increased population risk for hypertension in C allele carriers of the T8590C polymorphism of CYP4A11, which encodes an enzyme with reduced catalytic activity. We determined T8590C genotypes in 32 hypertensive subjects, 25 of whom were phenotyped for salt sensitivity of blood pressure and insulin sensitivity. Urine 20-HETE was lowest in insulin-resistant, salt-sensitive subjects (F=5.56; P<0.02). Genotypes were 13 TT, 2 CC, and 17 CT. C allele frequency was 32.8% (blacks: 38.9%; whites: 25.0%). C carriers (CC+CT) and TT subjects were similarly distributed among salt- and insulin-sensitivity phenotypes. C carriers had higher diastolic blood pressures and aldosterone:renin and waist:hip ratios but lower furosemide-induced fractional excretions of Na and K than TT. The T8590C genotype did not relate to sodium balance or pressure natriuresis. However, C carriers, compared with TT, had diminished 20-HETE responses to salt loading after adjustment for serum insulin concentration and resetting of the negative relationship between serum insulin and urine 20-HETE to a 1-μg/h lower level of 20-HETE. The effect of C was insulin independent and equipotent to 18 μU/mL of insulin (Δ20-HETE=2.84-0.054×insulin-0.98×C; r2=0.53; F=11.1; P<0.001). Hence, genetic (T8590C) and environmental (insulin) factors impair 20-HETE responses to salt in human hypertension. We propose that genotype analyses with sufficient homozygous CC will establish definitive relationships among 20-HETE, salt sensitivity of blood pressure, and insulin resistance.

Keywords: hypertension, obesity, arachidonic acid, cytochrome P450, insulin, insulin resistance

The monooxygenase derivative of arachidonic acid synthesized by CYP450 enzymes, 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE), is a candidate for participation in blood pressure regulation and hypertension. This could be via excess of its potent vasoconstrictor actions1-4 or deficiency of its inhibition of tubular transport, normally exerted at the NKCC cotransporter of the thick ascending limb and at the ubiquitous renal tubular Na-K-ATPase.5-8

Studies in Dahl-S rats9-11 and in angiotensin II-induced hypertension in mice12 support the view that a diminished effect of 20-HETE on renal transport is an important mechanism in experimental hypertension. Human population studies on polymorphisms of CYP4A11 that diminish its catalytic activity to synthesize 20-HETE13,14 are consistent with this interpretation.

Our studies in essential hypertension documented abnormal 20-HETE responses to physiological15 and pharmacological16 natriuresis and negative relationships with serum insulin17 but not diminished urinary excretion of 20-HETE, as expected from observations in rodents. Because Dahl-S rats are not only salt sensitive but also insulin resistant,18 we decided to investigate whether excretion of 20-HETE is diminished in hypertensive subjects who exhibit both phenotypes concomitantly. Also, population studies on CYP4A11 did not describe physiological phenotypes in participating subjects. Therefore, we genotyped the CYP4A11 T8590C locus in a series of hypertensive subjects characterized for salt sensitivity of blood pressure and insulin sensitivity, in an attempt to understand the mechanism for the possible association of the C allele with hypertension.

Methods

Thirty-two subjects with essential hypertension (blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg or taking antihypertensive medications) consented to participate in a protocol approved by the institutional review board. Genotyping for T8590C and salt sensitivity of blood pressure were determined in all of the subjects, whereas phenotyping for insulin sensitivity and measurement of 20-HETE excretion were completed in 25. Studies were conducted in the General Clinical Research Center ≥2 weeks after discontinuation of therapy and maintenance on usual salt intake. Salt sensitivity of blood pressure was assessed by means of a salt load (24 hours of a 160-mmol Na diet+2 L of saline infusion in 4 hours) followed by salt depletion by diet (10 mmol/d) and furosemide (120 mg over 8 hours) on the second day. A patient was deemed salt sensitive if daytime average systolic blood pressure (Spacelabs 90207 monitors) decreased ≥10 mm Hg from the salt-loading to the salt-depletion day.

Insulin sensitivity was determined with the homeostatic model assessment method, in which the index SIHOMA is calculated as 22.5*(glucose*insulin)-1.19 To reduce variability, each subject’s SIHOMA was obtained with fasting insulin and glucose data on 3 consecutive days. A patient was deemed insulin resistant if the average SIHOMA was <0.161 mL*L/μU*mmol, a cutoff derived from maximum normal fasting glucose (5.56 mmol/L) and maximum normal fasting insulin (25 μU/mL) in our laboratory.

During the salt-sensitivity protocol, urine from each period was collected for measurement of sodium excretion and 20-HETE, and blood samples were obtained for measurement of plasma renin activity and aldosterone. Serum insulin (Nichols Institute), plasma renin activity,20 and aldosterone21 were measured by radioimmunoassay. The method used for measurement of urine 20-HETE (negative chemical ionization, gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy of a 20-HETE derivative) has been reported previously in detail.15 Genotyping for the T8590C polymorphism of CYP4A11 was carried out by PCR amplification performed with intron-specific primers on DNA extracted from buffy coats. Primer sequences, reaction conditions, DNA extraction, and genotyping methods can be found at www.bioventures.com.13

Data are presented as means±SEMs. Comparisons between 2 groups were made with unpaired t tests for continuous variables and χ2 analysis for categorical variables. Comparisons among 4 groups were carried out by ANOVA and contrasting of means (Dunnett’s). Adjustment of 20-HETE by serum insulin was performed by ANCOVA, with the coefficient for insulin (β weight) obtained from multivariate regression with insulin as the covariate. Stepwise forward and backward multivariate regression analyses and all of the other tests were performed with JMP software (version 3.0.2, SAS Institute). A P value <0.05 was used to reject the null hypothesis. A posthoc power analysis confirmed that β error was <0.2 for n=25 and the results of the t test and ANOVAs presented in the 3 figures.

Results

Table 1 shows clinical and biochemical data in the entire population and in the 25 subjects characterized for salt sensitivity of blood pressure, insulin sensitivity, and 20-HETE excretion. The whole population was middle aged (47±2 years), obese (body mass index: 34±1 kg/m2), and predominantly female (24 women and 8 men); 18 subjects were black, and 14 were white. Average blood pressure was 154±4/94±2 mm Hg, but there was wide variability in the severity of blood pressure elevation, with 44% patients having stage 2 hypertension, as defined by Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure criteria.

Table 1.

Clinical and Biochemical Characteristics of C Carriers (CC+CT) and TT Subjects

| All Subjects (n=32) |

Subjects With IS+SS Data (n=25) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | CC+CT (19) | P | TT (13) | CC+CT (16) | P | TT (9) |

| Clinical variables | ||||||

| Age, y | 45±2 | 48±2 | 46±2 | 49±2 | ||

| Race, black/white | 13/6 | ≈0.09 | 5/8 | 10/6 | 4/5 | |

| BP, mm Hg | 155±5/98±2 | ns/<0.05 | 152±6/87±3 | 155±5/98±2 | ns/<0.03 | 154±7/88±3 |

| Na balancesalt-loaded, mmol | 135±26 | 140±30 | 120±28 | 153±42 | ||

| Creatinine clearance, mL/min | 140±9 | 125±10 | 142±10 | 135±12 | ||

| RAAS and electrolyte excretion | ||||||

| ARR, (pmol/L)/(ngAI/L/s) | 3625±561 | <0.05 | 2018±480 | 3505±637 | ≈0.07 | 1687±575 |

| PRAsalt-depleted, ngAI/L/s | 0.61±0.21 | 1.10±0.29 | 0.69±0.25 | 1.24±0.39 | ||

| ΔAldosalt-loaded, pmol/L | -33±56 | -170±53 | -35±67 | -210±65 | ||

| FENa, % | 1.9±0.2 | ≈0.06 | 2.3±0.2 | 1.9±0.2 | 2.2±0.2 | |

| FEK, % | 11.3±0.6 | <0.05 | 14.0±4.6 | 11.3±0.6 | <0.03 | 14.5±1.4 |

| Obesity/insulin sensitivity | ||||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 34±2 | 35±2 | 34±1 | 37±2 | ||

| Waist:hip ratio | 0.91±0.02 | <0.02 | 0.84±0.02 | 0.91±0.02 | 0.87±0.04 | |

| Serum insulin, μU/mL | 31.8±2.8 | 30.9±3.6 | ||||

| SIHOMA, mL*L/μU*mmol | 0.154±0.020 | 0.146±0.025 | ||||

IS indicates insulin sensitivity; SS, salt sensitivity; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; ARR, aldosterone:renin ratio; PRA, plasma renin activity; Aldo, aldosterone; FENa, fractional excretion of Na during furosemide; FEK, fractional excretion of K during furosemide; SIHOMA, insulin-sensitivity index. A blank space on the P value column or ns indicates a not statistically significant difference between groups; P values for trends (0.05<P<0.1) are given.

Genotypes for the T8590C polymorphism of CYP4A11 were 13 homozygous TT (40.6%), 2 homozygous CC (6.3%), and 17 heterozygous CT (53.1%). The frequency of the C allele was 32.8%, somewhat higher in blacks (38.9%) than in whites (25.0%), analogous to what has been reported in the Tennessee population.13 Because of the small number of CC homozygous subjects, all of the analyses were carried out as comparisons between carriers of the C allele (CC+CT, hereafter designated as C) versus homozygous TT.

There were no major differences between the fully phenotyped patients and the entire group. Table 1 shows that age, creatinine clearance, and sodium balance after salt loading did not differ between C and TT subjects. Racial distribution showed a trend, consistent with allele frequencies, toward a larger number of blacks in the C group. However, this difference did not reach statistical significance. Diastolic blood pressure, but not systolic, was higher in C than in TT.

C subjects had significantly higher aldosterone:renin ratios during usual salt intake compared with TT subjects (a trend also observed in the fully phenotyped subgroup). This observation was independent of race in multivariate analysis (P for race=0.60). They also had diminished fractional excretion of K during furosemide administration and trends (P value not statistically significant) toward lower plasma renin activity during salt depletion, decreased suppression of aldosterone by salt loading, and diminished fractional excretion of Na during furosemide. Although these characteristics suggest a relationship between the C allele and salt sensitivity of blood pressure, the slopes of the pressure-natriuresis curves did not differ between the C (0.96±0.10 radians) and TT groups (1.05±0.17 radians; not shown). Moreover, the proportions of C and TT subjects were not different among salt-sensitive (C=59% and T=41%) and salt-resistant (C=60% and T=40%) individuals.

Waist:hip ratio was significantly higher in C subjects (not significant in the fully phenotyped subset), but body mass index was not different between the C and TT groups. The observation about waist:hip ratios may suggest a relationship between the C allele and insulin resistance. However, serum insulin and the insulin-sensitivity index were not different between C and TT in the subjects phenotyped for insulin sensitivity. Moreover, the proportions of C and TT subjects were not different between insulin-resistant (C=60% and T=40%) and insulin-sensitive (C=62% and T=38%) groups.

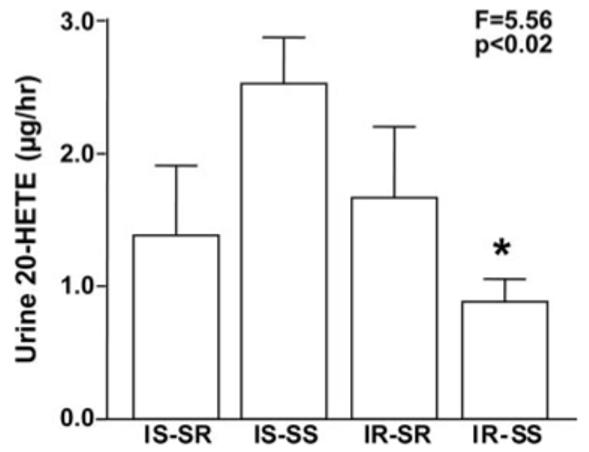

Of the 25 fully phenotyped subjects, 13 were salt sensitive (fall of systolic BP from salt loading to salt depletion: -13.4±1.4 mm Hg) and 12 were salt resistant (fall of systolic BP from salt loading to salt depletion: -4.3±1.4 mm Hg), whereas 14 were insulin resistant (serum insulin: 39.2±2.3 μU/mL; SIHOMA: 0.034±0.009 mL*L/μU*mmol) and 11 were insulin sensitive (serum insulin: 22.3±1.2 μU/mL; SIHOMA: 0.221±0.014 mL*L/μU*mmol). Figure 1 shows urine 20-HETE excretion during salt loading in these subjects, divided into 4 groups defined by the combination of insulin sensitivity and salt sensitivity of blood pressure. Urine 20-HETE was significantly lower in insulin-resistant, salt-sensitive subjects (0.88±0.17 μg/h) than in the other 3 groups, as depicted in Figure 1 and by the statistics in the legend.

Figure 1.

Urinary excretion of 20-HETE during salt loading in 4 groups of subjects grouped by 2 phenotypes: insulin sensitivity and salt sensitivity of blood pressure. IS indicates insulin sensitive; IR, insulin resistant; SS, salt sensitive; and SR, salt resistant. The number of subjects and their racial distribution (black/white subjects) were as follows: IS-SR: 4 (2/2), IS-SS: 7 (4/3), IR-SR: 8 (5/3), and IR-SS: 6 (3/3). The F statistic and P value are for the ANOVA comparing the 4 groups (Welch, unequal variances). *Reduced 20-HETE excretion in IR-SS vs the other groups (contrasting of means, Dunnett’s test, P<0.04).

The unadjusted urine 20-HETE response to salt loading tended to be lower in C than in TT subjects, but the difference was not significant (Figure 2, left). In contrast, after adjustment for individual serum insulin by covariate analysis, the 20-HETE response to salt was significantly diminished in C subjects compared with TT subjects (Figure 2, right). These results indicate that both the previously demonstrated inhibitory effect of serum insulin on 20-HETE excretion17 and the CYP4A11 polymorphism determine 20-HETE excretion.

Figure 2.

Urine 20-HETE responses to salt loading in C and TT subjects. The left panel shows unadjusted 20-HETE values, whereas the right panel provides the results of a covariate analysis in which 20-HETE excretion was adjusted for the serum insulin level of each subject. C indicates carriers of the C allele of T8590C (CC=2 and CT=14); TT, subjects homozygous for the T allele (n=9); ns, not significant.

The regression analysis in Table 2 quantifies these effects. In this model, the dependent variable was the increase in 20-HETE excretion produced by salt loading, and the regressors were serum insulin and a dummy variable representing the C and TT groups. The model was significant. The effects of insulin and the C allele in reducing 20-HETE excretion were independent (the interaction term was not significant). Because there were more carriers of the C allele among black than among white subjects, we excluded that the effect of the C allele was because of race by determining the following: (1) the coefficient for race was not statistically significant (P=0.92); (2) including race as a regressor did not increase r2 (0.53); and (3) race did not change the significance of the effect of the C allele in stepwise forward or backward procedures.

Table 2.

Multivariate Regression Model for the 20-HETE Response to Salt Loading (Micrograms per Hour)

| Parameter Estimates | ||||

| Term | Estimate | SE | t Ratio | P>|t| |

| Intercept | 2.8449 | 0.5218 | 5.45 | <0.0001 |

| Insulin, μU/mL | -0.0539 | 0.0137 | -3.92 | 0.0008 |

| Allele (C=0, T=1) | 0.9808 | 0.3092 | 3.17 | 0.0048 |

| Summary of fit and ANOVA | ||||

| r2 | 0.5263 | |||

| F ratio | 11.1130 | |||

| P>F | 0.0006 | |||

C=0 and T=1 indicate dummy variables for carriers of the C allele vs homozygous TT subjects. Introduction of either the variable race or the interaction term insulin*allele as regressors in the model had no statistically significant effect (see text).

Finally, from the coefficients in the model, it can be calculated that carrying the C allele results in a lesser 20-HETE response to salt of ≈1 μg/h at all of the levels of serum insulin. Also, this effect of the C allele is approximately equipotent to that of an increase in serum insulin of ≈18 μU/mL.

Consistent with the results of this model, patients with coexisting insulin resistance and the C allele exhibited no response of 20-HETE to salt loading (-0.20±0.30 μg/h), whereas those with normal insulin sensitivity and the TT genotype had maximal responses (1.80±0.67 μg/h). The other 2 groups, insulin-resistant subjects with the TT genotype and insulin-sensitive subjects with the C allele, had 20-HETE responses to salt of intermediate magnitude (0.64±0.32 and 0.65±0.27 μg/h, respectively; Figure 3). The statistics for this comparison are in the figure legend.

Figure 3.

Urine 20-HETE responses to salt loading in 4 groups of subjects grouped by both insulin-sensitivity phenotype (IS indicates insulin sensitive; IR, insulin resistant) and CYP4A11 genotype (C indicates carriers of the C allele of T8590C, either CC or CT genotype; TT, subjects homozygous for the T allele). The number of subjects in each group was as follows: IS-TT, 5; IS-C, 6; IR-TT, 7; and IR-C, 7. The F statistic and P value on the graph are for the ANOVA comparing the 4 groups. *Statistically significant difference in the 20-HETE response to salt between the IR-C and IS-TT groups (contrasting of means, Dunnett’s test, P<0.02).

Discussion

Our initial studies on a possible role for 20-HETE in human hypertension15-17 were stimulated by the unequivocal evidence that a deficit in outer medullary CYP4A2 protein and 20-HETE is linked to salt sensitivity of blood pressure in Dahl-S rats. In addition to direct documentation of these deficits,9 a series of publications characterized the functional consequences of decreased 20-HETE of renal medullary origin, including an increase in chloride transport, shift in pressure natriuresis, and salt-sensitive hypertension.10 Moreover, these abnormalities can be ameliorated by infusion of 20-HETE in the renal medulla10 or reproduced in control strains by inhibiting 20-HETE synthesis.22 A role for a deficit of renal tubular 20-HETE in hypertension, via loss of its inhibitory actions on sodium transport,5,7,8 has also been documented in other species. In C57BL/6J mice, which have very low renal production of 20-HETE, fenofibrate abolishes angiotensin II hypertension by stimulating CYP4a protein in renal tubules, not vessels.12 In humans, polymorphisms in the major CYP isoforms that synthesize 20-HETE (M allele of V433M in CYP4F223 and C allele of T8590C in CYP4A1113,14) produce enzymes with diminished catalytic activity. In the case of CYP4A11, there is proof in population studies for an association between the variant enzyme and hypertension.13,14

The P450 4A1 and 4A2 gene loci cosegregate with blood pressure in F2 crosses of Dahl-S and control rats.9 However, absolute proof that CYP genes are the cause of salt sensitivity of blood pressure has not yet been provided. There are 2 monogenic forms of hypertension produced by knocking out CYP4A genes in mice. One does not involve 20-HETE. This is the CYP4A10[-/-], in which salt-sensitive hypertension relates to diminished activity of the CYP2C44 epoxygenase with diminished synthesis of 11,12-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid and unchanged CYP4A12 and renal 20-HETE.24 The other depends on excessive 20-HETE vasoconstriction because of increased, rather than decreased, synthesis of the compound. This is the CYP4A14[-/-], which develops androgen-dependent hypertension associated with overexpression of CYP4A12.25 Congenic Dahl-S strains harboring the entire region of chromosome 5 that contains the CYP4A genes from Lewis rats exhibit restored synthesis of outer medullary CYP4A protein and 20-HETE and have blunted blood pressure responses to salt and reduced proteinuria compared with Dahl-S strains.11 However, experiments with different overlapping sections of the transferred chromosome raised the possibility that the CYP4A3 and A8 genes, not A1 and A2, may be responsible for the effect of retrogressing the entire region into the congenic strains.26

In our early experiments, we measured 20-HETE in subjects with salt-sensitive hypertension in the expectation that urinary excretion might be reduced, analogous to decreased synthesis of the compound in Dahl-S kidney. Urine 20-HETE excretion most likely reflects its renal synthesis, because the urine is the most important efflux pathway for renal 20-HETE.27 Although we detected abnormal regulation of physiological (salt loading)15 and pharmacological (furosemide)16 natriuresis by 20-HETE in these patients, we did not find reduced urinary excretion of the compound. Analogously, salt-sensitive young Sprague-Dawley rats have impaired 20-HETE-induced natriuresis despite high excretion levels of this compound, an abnormality that disappears as they age and become salt resistant.28 Therefore, it is apparent that salt sensitivity of blood pressure may relate to either diminished synthesis or to defective natriuretic action of 20-HETE and perhaps to a combination of both.

Later on we showed that our unexpected finding of a strong negative correlation between urine 20-HETE excretion and body mass index 15 was explained by the observation that hyperinsulinemia is a major factor inhibiting urine 20-HETE excretion in humans.17 This is consistent with known insulin inhibition of CYP4A1, 2, and 3 isoforms in liver and kidney microsomes of the rat29 and suggests that insulin may also inhibit the isoforms that synthesize 20-HETE in humans. It is conceivable that inhibition of outer renal medullary CYP4A isoforms is a mechanism by which insulin increases sodium reabsorption at the thick ascending limb, because insulin also exerts this action at the proximal tubule by translational and posttranslational activation of the NHE3 isoform of the Na+/H+ exchanger30; at the thiazide-sensitive Na+Cl- transporter via diminished expression of WNK4 kinase31; and at the epithelial sodium channel, via phosphorylation and translocation of the 3 channel subunits to the membrane.32

This publication extends our previous observations in 2 regards. First, whereas Dahl-S rats are an inbred strain in which salt sensitivity of blood pressure coexists with insulin resistance,18 salt-sensitive hypertensive subjects are not always insulin resistant.33 We hypothesized that measuring 20-HETE excretion in patients characterized for both phenotypes would document reduced urine excretion of 20-HETE in hypertensive subjects with concomitant salt sensitivity of blood pressure and insulin resistance. We confirmed this hypothesis, which strengthens the view that, regardless of the genetics of CYP4A in hypertension, serum insulin is a major nongenetic determinant of the activity of the CYP4A system in the human kidney. Hence, insulin may regulate sodium and chloride transport and blood pressure via actions at the thick ascending limb.

Second, whereas in Dahl-S rats the hypertension relates to a deficit in CYP4A protein and renal medullary 20-HETE, in humans it relates to a variant enzyme (C allele of the T8590C polymorphism of CYP4A11), which probably determines diminished 20-HETE levels because of diminished catalytic activity, although this has never been shown in the population studies.13,14 We now demonstrate that the C allele of T8590C resets the inhibitory relationship between insulin and 20-HETE excretion toward lower levels of 20-HETE compared with that observed in homozygous TT subjects. Our data suggest that the C allele leads to reduced synthesis of 20-HETE at any given level of serum insulin and that the ultimate level of urine 20-HETE is the consequence of the genetic effect of the CYP4A11 polymorphism and the insulin-sensitivity phenotype of the subject. These suggestions are supported by the observation that stimulation of 20-HETE excretion by salt loading is absent in hypertensive carriers of the C allele who are insulin resistant.

Aldosterone:renin ratios are increased, independent of race, in C-allele carriers. We have validated this observation in a separate cohort (n=45) from Vanderbilt University (N.J. Brown, unpublished data, 2007). Increased aldosterone:renin ratios perhaps explain more severe blood pressure elevation in C-allele carriers than in TT subjects, a possibility that remains to be explored further.

Decreased insulin-mediated glucose uptake and hyperinsulinemia are observed in normotensive offspring of hypertensive subjects, supporting the view that a genetic predisposition may contribute to both abnormalities.34 The sodium-retaining actions of insulin have been implicated in the pathogenesis of salt-sensitive hypertension, independent of obesity.35 Our data suggest that 1 of the plausible mechanisms underlying the relationships among insulin resistance, salt sensitivity of blood pressure, and essential hypertension is an abnormal synthesis of 20-HETE.

Perspectives

Regulation of renal sodium handling and salt sensitivity of blood pressure by CYP450 metabolites of arachidonic acid is complex and may involve genetically determined deficiencies of monooxygenases and epoxygenases, single nucleotide polymorphisms that affect catalytic activity of these enzymes, and interactions with phenotypes that affect expression of their genes. Our work has focused on the effects of insulin and the C allele of CYP4A11, both leading to reduced urine excretion of 20-HETE in human hypertension. Because of the potential effects of reduced 20-HETE actions on sodium reabsorption, shift in pressure natriuresis curves, and salt-sensitive hypertension, the observations are important in that they could be subject to therapeutic intervention with available agents. That is, stimulation of expression of the variant CYP4A11 enzyme by fibrates, reduction of serum insulin by thiazolidinediones, or the achievement of both effects by dual peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonists may lead to increased 20-HETE synthesis, hence, increased 20-HETE-mediated natriuresis, diminution of salt sensitivity of blood pressure (an independent risk factor for cardiovascular mortality), and amelioration of hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants MO1 RR00073 NCRR (C.L.L. and F.E.); HL04221 and RR00095 (J.V.G.); HL65193, HL67308, and HL60906 (N.J.B.); DK38226 (J.H.C.); and grant PO1 34300 (A.N. and M.L.-S.).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Imig JD, Zou AP, Stec DE, Harder DR, Falck JR, Roman RJ. Formation and actions of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid in rat renal arterioles. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:R217–R227. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.1.R217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso-Galicia M, Falck JR, Reddy KM, Roman RJ. 20-HETE agonists and antagonists in the renal circulation. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:F790–F796. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.5.F790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kauser K, Clark JE, Masters BS, Ortiz de Montellano PR, Ma YH, Harder DR, Roman RJ. Inhibitors of cytochrome P-450 attenuate the myogenic response of dog renal arcuate arteries. Circ Res. 1991;68:1154–1163. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.4.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imig JD, Zou AP, Ortiz de Montellano PR, Sui Z, Roman RJ. Cytochrome P-450 inhibitors alter afferent arteriolar responses to elevations in pressure. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H1879–H1885. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.5.H1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nowicki S, Chen SL, Aizman O, Cheng XJ, Li D, Nowicki C, Nairn A, Greengard P, Aperia A. 20-Hydroxyeicosa-tetraenoic acid (20 HETE) activates protein kinase C: role in regulation of rat renal Na+,K+-ATPase. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1224–1230. doi: 10.1172/JCI119279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ribeiro CM, Dubay GR, Falck JR, Mandel LJ. Parathyroid hormone inhibits Na(+)-K(+)-ATPase through a cytochrome P-450 pathway. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:F497–F505. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.266.3.F497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amlal H, LeGoff C, Vernimmen C, Soleimani M, Paillard M, Bichara M. ANG II controls Na(+)-K+(NH4+)-2Cl- cotransport via 20-HETE and PKC in medullary thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1047–C1056. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.4.C1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Escalante B, Erlij D, Falck JR, McGiff JC. Cytochrome P-450 arachidonate metabolites affect ion fluxes in rabbit medullary thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:C1775–C1782. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.6.C1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stec DE, Deng AY, Rapp JP, Roman RJ. Cytochrome P4504A genotype cosegregates with hypertension in Dahl S rats. Hypertension. 1996;27:564–568. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou AP, Drummond HA, Roman RJ. Role of 20-HETE in elevating loop chloride reabsorption in Dahl SS/Jr rats. Hypertension. 1996;27:631–635. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roman RJ, Hoagland KM, Lopez B, Kwitek AE, Garrett MR, Rapp JP, Lazar J, Jacob HJ, Sarkis A. Characterization of blood pressure and renal function in chromosome 5 congenic strains of Dahl S rats. Am J Physiol. 2006;290:F1463–F1471. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00360.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vera T, Taylor M, Bohman Q, Flasch A, Roman RJ, Stec DE. Fenofibrate prevents the development of angiotensin II-dependent hypertension in mice. Hypertension. 2005;45:730–735. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153317.06072.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gainer JV, Bellamine A, Dawson EP, Womble KE, Grant SW, Wang Y, Cupples LA, Guo CY, Demissie S, O’Donnell CJ, Brown NJ, Waterman MR, Capdevila JH. Functional variant of CYP4A11 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid synthase is associated with essential hypertension. Circulation. 2005;111:63–69. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151309.82473.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayer B, Lieb W, Götz A, König IR, Aherrahrou Z, Thiemig A, Holmer S, Hengstenberg C, Doering A, Loewel H, Hense HW, Schunkert H, Erdmann J. Association of the T8590C polymorphism of CYP4A11 with hypertension in the MONICA Augsburg echocardiographic substudy. Hypertension. 2005;46:766–771. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000182658.04299.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laffer CL, Laniado-Schwartzman M, Wang MH, Nasjletti A, Elijovich F. Differential regulation of natriuresis by 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid in human salt-sensitive versus salt-resistant hypertension. Circulation. 2003;107:574–578. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000046269.52392.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laffer CL, Laniado-Schwartzman M, Wang MH, Nasjletti A, Elijovich F. 20-HETE and furosemide-induced natriuresis in salt-sensitive essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;41:703–708. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000051888.91497.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laffer CL, Laniado-Schwartzman M, Nasjletti A, Elijovich F. 20-HETE and circulating insulin in essential hypertension with obesity. Hypertension. 2004;43:388–392. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000112224.87290.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reaven GM, Twersky J, Chang H. Abnormalities of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in Dahl rats. Hypertension. 1991;18:630–635. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.18.5.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radziuk J. Insulin sensitivity and its measurement: structural common-alities among the methods. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4426–4433. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.12.7025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sealey JE, Gerten-Banes J, Laragh JH. The renin system: variations in man measured by radioimmunoassay or bioassay. Kidney Intl. 1972;1:240–253. doi: 10.1038/ki.1972.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antunes JR, Dale SL, Melby JC. Simplified radioimmunoassay for aldosterone using antisera to aldosterone-gamma-lactone. Steroids. 1976;28:621–630. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(76)90004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stec DE, Mattson DL, Roman RJ. Inhibition of renal outer medullary 20-HETE production produces hypertension in Lewis rats. Hypertension. 1997;29:315–319. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stec DE, Roman RJ, Flasch A, Rieder MJ. Functional polymorphism in human CYP4F2 decreases 20-HETE production. Physiol Genomics. 2007;30:74–81. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00003.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakagawa K, Holla VR, Wei Y, Wang WH, Gatica A, Wei S, Mei S, Miller CM, Cha DR, Price E, Jr, Zent R, Pozzi A, Breyer MD, Guan Y, Falck JR, Waterman MR, Capdevila JH. Salt-sensitive hypertension is associated with dysfunctional Cyp4a10 gene and kidney epithelial sodium channel. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1696–1702. doi: 10.1172/JCI27546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holla VR, Adas F, Imig JD, Zhao X, Price E, Jr, Olsen N, Kovacs WJ, Magnuson MA, Keeney DS, Breyer MD, Falck JR, Waterman MR, Capdevila JH. Alterations in the regulation of androgen-sensitive Cyp 4a monooxygenases cause hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5211–5216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081627898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoagland KM, Alonso-Galicia M, Maier KG, Flasch AK, Wang X, Jacob HJ, Nobrega M, Rapp JP, Garrett MR, Roman RJ. Evaluation of P4504a genes for hypertension and renal disease using chromosome 5 congenic strains of Dahl S rats. Hypertension. 2000;36:687–b. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carroll MA, Balazy M, Huang DD, Rybalova S, Falck JR, McGiff JC. Cytochrome P450-derived renal HETEs: storage and release. Kidney Intl. 1997;51:1696–1702. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sankaralingam S, Desai KM, Glaeser H, Kim RB, Wilson TW. Inability to upregulate cytochrome P450 4A and 2C causes salt sensitivity in young Sprague-Dawley rats. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:1174–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimojo N, Ishizaki T, Imaoka S, Funae Y, Fuji S, Okuda K. Changes in amounts of cytochrome P450 isozymes and levels of catalytic activities in hepatic and renal microsomes of rats with streptozocin-induced diabetes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;46:621–627. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90547-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klisic J, Hu MC, Nief V, Reyes L, Fuster D, Moe OW, Ambühl PM. Insulin activates Na /H exchanger 3: biphasic response and glucocorticoid dependence. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:F532–F539. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00365.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song J, Hu X, Riazi S, Tiwari S, Wade JB, Ecelbarger CA. Regulation of blood pressure, the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), and other key renal sodium transporters by chronic insulin infusion in rats. Am J Physiol. 2006;290:F1055–F1064. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00108.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang YH, Alvarez de la Rosa D, Canessa CM, Hayslett JP. Insulin-induced phosphorylation of ENaC correlates with increased sodium channel function in A6 cells. Am J Physiol. 2005;288:141–147. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00343.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raji A, Williams GH, Jeunemaitre X, Hopkins PN, Hunt SC, Hollenberg NK, Seely EW. Insulin resistance in hypertensives: effect of salt sensitivity, renin status and sodium intake. J Hypertens. 2001;19:99–105. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200101000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grunfeld B, Balzareti H, Romo H, Gimenez M, Gutman R. Hyperinsulinemia in normotensive offspring of hypertensive parents. Hypertension. 1994;23:I12–I15. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.1_suppl.i12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fuenmayor N, Moreira E, Cubeddu LX. Salt sensitivity is associated with insulin resistance in essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11:397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00490-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]