Abstract

Purpose

A randomized, controlled trial comparing hand-assisted laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy with open surgery did not show an advantage for the laparoscopic approach. The trial was criticized because hand-assisted laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy was not considered a true laparoscopic proctocolectomy. The objective of the present study was to assess whether total laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy has advantages over hand-assisted laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy with respect to early recovery.

Methods

Thirty-five patients underwent total laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy and were compared to 60 patients from a previously conducted randomized, controlled trial comparing hand-assisted laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy and open restorative proctocolectomy. End points included operating time, conversion rate, reoperation rate, hospital stay, morbidity, quality of life, and costs. The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 and the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index were used to evaluate general and bowel-related quality of life.

Results

Groups were comparable for patient characteristics, such as sex, body mass index, preoperative disease duration, and age. There were neither conversions nor intraoperative complications. Median operating time was longer in the total laparoscopic compared with the hand-assisted laparoscopic group (298 vs. 214 minutes; P < 0.001). Morbidity and reoperation rates in the total laparoscopic, hand-assisted laparoscopic, and open groups were comparable (29 vs. 20 vs. 23 percent and 17 vs.10 vs. 13 percent, respectively). Median hospital-stay was 9 days in the total laparoscopic group compared with 10 days in the hand-assisted laparoscopic group and 11 days in the open group (P = not significant). There were no differences in quality of life and total costs.

Conclusions

There were no significant short-term benefits for total laparoscopic compared with hand-assisted laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy with respect to early morbidity, operating time, quality of life, costs, and hospital stay.

Key words: Restorative proctocolectomy, Total laparosocpic, Hand-assisted laparoscopic, Ileal pouch-anal-anastomosis, Ulcerative colitis, Familial polyposis coli

Restorative proctocolectomy is considered the operation of choice for patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and familial polyposis coli (FAP). Several studies have demonstrated laparoscopic approaches for restorative proctocolectomy to be feasible and safe. However, most of these studies concluded that recovery after laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy (LRP) was similar or only marginally improved compared with conventional open restorative proctocolectomy (ORP).1–3

The only randomized trial comparing LRP with ORP, applying a hand-assisted laparoscopic technique (HAL-RP), indicated that there were no benefits with respect to early recovery and morbidity.4 Critics argued that the hand-assisted laparoscopic technique could not be considered a true laparoscopic procedure. It was suggested that the lack of difference in outcome between HAL-RP and ORP could be explained by the fact that the HAL-RP is a hybrid laparoscopic procedure consisting of a hand-assisted colectomy followed by an open restorative proctectomy via the Pfannenstiel incision used for the insertion of the handport. The open proctectomy during HAL-RP requires the use of a ring-retractor, which causes considerable strain on the abdominal wound. The question emerged whether a pure laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy would show the expected benefits. Therefore, the authors decided to adapt a total laparoscopic approach by combining a total laparoscopic colectomy and laparoscopic restorative proctectomy (TLRP) on a cohort of patients and compare outcomes with those after HAL-RP and ORP. TLRP is believed to be less invasive than the hand-assisted laparoscopic approach because of lesser manipulation of the bowel and abdominal wound. Although theoretic advantages of both procedures are strongly debated in the literature, the advantages of either procedure cannot be sustained by good quality studies comparing both approaches directly.

The objective of this study was to determine whether a total laparoscopic approach for restorative proctocolectomy has short-term advantages compared with a hand-assisted laparoscopic approach with respect to morbidity, early recovery, cost, and quality of life. Because no significant differences between HAL-RP and ORP were found in the previously conducted RCT, the results after TLRP will be compared with those after ORP as well.

Patients and Methods

In the period April 2004 to March 2006, patients eligible for restorative proctocolectomy were operated by a total laparoscopic approach and prospectively evaluated. Short-term outcomes were compared with those of a patient population of a previously conducted, randomized, controlled two-center trial. In this trial, conducted in the period January 2000 to August 2003, patients were allocated to HAL-RP or ORP. Short-term results (perioperative data and quality of life (QOL) until 3 months after operation) of this randomized trial have been published previously.5

The surgical technique of TLRP consisted of a medial to lateral total laparoscopic proctocolectomy using a 6-trocar technique. After complete laparoscopic dissection of the rectum down to the pelvic floor, the midrectum is transected laparoscopically by using a linear endostapler with knife (Endopath®, TSB45, Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Amersfoort, The Netherlands). The colon and half of the rectum can now be extracted through a 6-cm Pfannenstiel incision. With the colon out of the way, the rectum stump can be retracted with a Satinsky clamp and cross stapled 1-cm to 2-cm proximal to the dentate line by using an open TL 30 stapler (Proximate® TL30, Ethicon Endo-Surgery) to ensure a transverse low rectal cross-stapling. The terminal ileum was exteriorized and the pouch was created by using a 100-mm linear cutter (Proximate TLC10®, Ethicon Endo-Surgery) and the anvil of the circular stapler (Proximate CDH29®, Ethicon Endo-Surgery) was inserted in the base of the pouch. After re-establishing the pneumoperitoneum, the ileoanal anastomosis was created laparoscopically. The surgical technique of HAL-RP has been described previously.6 In summary, an 8-cm Pfannenstiel incision was made at the start of the operation. After mobilizing the sigmoid through this incision, the handport was placed in the Pfannenstiel incision. Three additional trocars were inserted. Under manual guidance, mobilization of the large bowel was performed. Proctectomy was performed openly via the Pfannenstiel incision. A J-pouch was constructed for both the total laparoscopic, hand-assisted laparoscopic, and open approaches. A defunctioning ileostomy in all groups was only given in selected cases: in case of active inflammatory disease defined as bloody stool and high-dosage corticosteroids (>10 mg/day), in case of difficult dissection or technical difficulties during construction of the anastomosis, in case of bleeding, or in case of an incomplete donut.

Postoperative care of the TLRP group was identical to the patient groups who underwent HAL-RP and ORP. All patients who did not have a defunctioning ileostomy received a pouch catheter, which was never removed until the sixth day after surgery. Oral intake was advanced to liquids and nutritional supplements as fast as possible after surgery. Only after removal of the pouch catheter, patients were allowed to have solids because of fear of solid stool blocking the pouch catheter. In patients who had a defunctioning ileostomy, oral intake was advanced as fast as possible to a normal diet. Discharge criteria in the three groups were equal and consisted of 1) adequate pain control with oral drugs, 2) absence of nausea, 3) passage of first flatus and/or stool, as well as an acceptable stool frequency (<10/day), 4) ability to tolerate solid food, 5) mobilization and self support as preoperative, and 6) acceptance of discharge by the patient.

Primary end points were operating time, conversion rate, early morbidity (within 30 days after surgery), morphine requirement, and costs. Daily (postoperative Day (POD) 1, POD2, and POD3) and total morphine requirement was assessed in all patients who received patient-controlled analgesia (PCA). The allocation to PCA or epidural analgesia was at the discretion of the attending anesthesiologist and patient’s preference. The calculation of total costs was based on the amounts for costs for material used during the procedure, costs for use of an operating room with personnel, costs for relaparotomies or relaparoscopies, and costs for admission days. Preoperative costs were not taken into account.

Secondary end points were time to resumption of full liquid (>1,000 ml) and normal (solid) diet, and QOL measured by the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36) and the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) preoperatively, and at one, two, and four weeks, and three months after the operation.7,8

Statistics

All data are presented as median and range, unless otherwise specified. The nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare discrete and continuous variables between the three groups. If P < 0.05, a post-hoc analysis using the Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare discrete and continuous data between two groups. The chi-squared test, or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate were used to compare categorical or dichotomous variables between groups. For comparison of results of different time points of QOL, a repeated measures multivariate ANOVA procedure was used.

Results

In the study period, 35 of 37 patients with UC or FAP eligible for surgery had a one-stage TLRP. Patient characteristics of the three groups are shown at Table 1. There were no significant differences between the groups, although patients from the HAL-RP group tended to be younger than patients from both other groups and the proportion of patients with FAP in the TLRP group tended to be smaller than in the HAL-RP and ORP group. As a consequence, the number of patients receiving immunosuppressive drugs in the TLRP was higher compared with both other groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 95 patients before one-stage restorative proctocolectomy

| TLRP (n = 35) | HAL-RP (n = 30) | ORP (n = 30) | P value* | P value† | P value‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male:female ratio | 11:24 | 9:21 | 15:15 | 0.194 | — | — |

| Age (yr) | 36 (15–54) | 29 (16–57) | 35 (16–57) | 0.045 | 0.076 | 0.43 |

| UC:FAP ratio | 30:5 | 20:10 | 20:10 | 0.13 | — | — |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.3 (16.6–39.5) | 22.6 (18.1–34.7) | 23.3 (17.2–34.2) | 0.692 | — | — |

| Duration of disease (yr) | 7 (0.1–30) | 6 (0.5–37) | 4 (0.1–15) | 0.345 | — | — |

TLRP = total laparosopic restorative proctocolectomy; HAL-RP = hand-assisted laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy; ORP = open restorative proctocolectomy; M = male; F = female; UC = ulcerative colitis; FAP = familial polyposis coli; BMI = body mass index.

Data are numbers of patients or medians with ranges in parentheses unless otherwise indicated.

*TLRP vs. HAL-RP vs. ORP (Kruskal-Wallis for continuous variables, chi-squared test, or Fisher’s exact test (n < 5) for categorical variables).

†TLRP vs. HAL-RP (Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, chi-squared test, or Fisher’s exact test (n < 5) for categorical variables).

‡TLRP vs. ORP (Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, chi-squared test, or Fisher’s exact test (n < 5) for categorical variables).

There were no intraoperative complications in either group and there were no conversions in the laparoscopic groups (Table 2). Operating time was significantly longer in the TLRP compared with the HAL-RP and ORP groups.

Table 2.

Results of peri-operative outcome parameters after TLRP vs. HAL-RP and ORP

| TLRP (n = 35) | HAL-RP (n = 30) | ORP (n = 30) | P value§ | P value* | P value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operating time‡ (min) | 298 (235–375) | 214 (149–400) | 133 (97–260) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Primary protecting loop ileostomy | 12 | 8 | 7 | 0.601 | — | — |

| Hospital stay‡ | 9 (5–39) | 10 (5–31) | 11 (6–28) | 0.139 | — | — |

| Minor complications*** | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0.698 | — | — |

| Wound infection | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urinary tract infection | 2 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Pneumonia | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Major complications*** §§ | 7 | 5 | 4 | 0.745 | — | — |

| Persistent ileus/inability to defecate | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | 2 (2) | |||

| Anastomotic leakage | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | |||

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | |||

| SB herniation through omentum | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Stoma necrosis | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Corpus alienum | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | |||

| Total number of patients with re-operation | 6 | 3 | 4 | 0.705 | — | — |

| All patients with diversion (including those after re-operation) | 16 | 11 | 11 | 0.686 | — | — |

‡ Median with range

§ P TLRP vs HAL-RP vs ORP (Kruskall Wallis for continues variables, Chi square test or Fisher’s exact test (n < 5) for categorical variables)

* P TLRP vs HAL-RP (Mann Whitney U test for continues variables, Chi square test or Fisher’s exact test (n < 5) for categorical variables)

**P TLRP vs ORP (Mann Whitney U test for continues variables, Chi square test or Fisher´s exact test (n<5) for categorical variables)

*** Within 30 days after operation

SB: small bowel

§§ numbers between parantheses are the numbers of patients requiring a re-operation for specific complication

TLRP: Total laparosopic restorative protocolectomy

HAL-RP: Hand-assisted laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy

ORP: Open restorative proctocolectomy

Morbidity in terms of major and minor complications was comparable among the three groups. Nonetheless, compared with the HAL-RP group, more patients from the TLRP group underwent reoperation. There were seven major complications in the TLRP group. Six patients were reoperated: five laparoscopically and one by open surgery because of necrosis of the ileostomy (Table 2). All patients who had a laparoscopic reintervention were given a protecting loop ileostomy except for one patient with a small-bowel herniation through the major omentum. All major complications requiring a reoperation in each of the three groups regarding anastomotic leak or abscess formation occurred in patients without a protecting ileostomy. Indications for reoperation in each of the three groups are provided in Table 2.

A total of 16 patients who underwent TLRP had undergone a diversion procedure at the time of discharge from the hospital (12 primary, 4 secondary). In all these patients bowel continuity was restored within three months after surgery. In the HAL-RP group, 11 had undergone a diversion procedure at the time of discharge (8 primary, 3 secondary). In the ORP group, 11 patients were diverted (7 primary, 4 secondary). In ten patients from both groups, bowel continuity was restored within three months after surgery. In one patient from the HAL-RP group, bowel continuity was never restored because of the postoperative diagnosis of a cholangiocarcinoma. In one patient from the ORP group, bowel continuity could not be restored because of a persistent intra-abdominal abscess.9

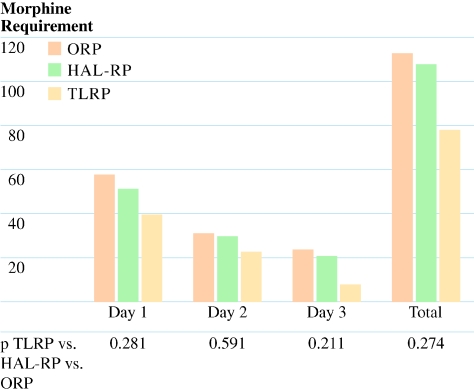

There was a statistically significant shorter period to oral intake in the TLRP group compared with both other groups (time to resumption of liquid diet, 3 vs. 5 vs. 5 days and normal diet 5 vs. 6 vs. 7 days in the TLRP, HAL-RP, and ORP groups, respectively; P = 0.004 and P = 0.018, respectively). In spite of this, there was no statistical difference in hospital stay between the three groups (Table 2). Although daily and total morphine requirement in the TLRP was lower compared with the HAL-RP and ORP groups, this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Daily and total morphine requirement after TLRP vs. HAL-RP vs. ORP. HAL-RP = hand-assisted laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy; TLRP = total laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy; ORP = open restorative proctocolectomy.

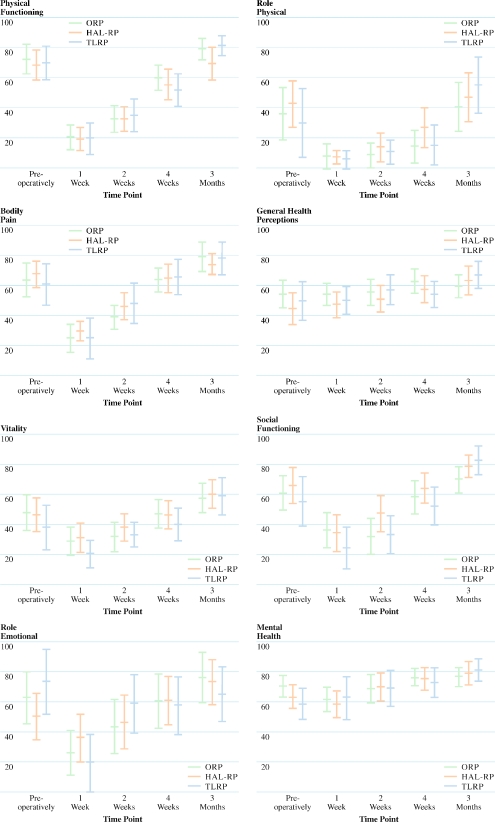

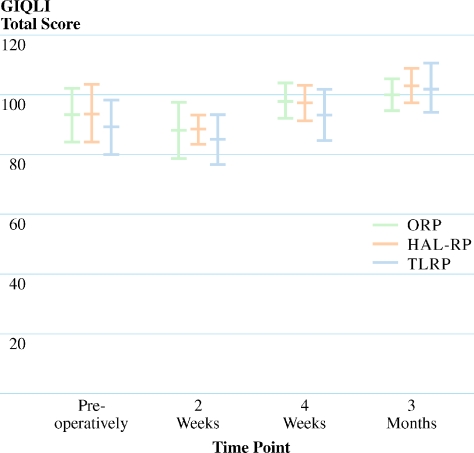

Results of the SF-36 and GIQLI were comparable between the groups. A significant decline was found on all scales of the SF-36 (Fig. 2) and total GIQLI score (Fig. 3) in the first two weeks after the operation (P < 0.05). This decline was, however, not affected by the type of surgery (TLRP vs. HAL-RP vs. ORP; P > 0.05). QOL returned to baseline levels after four weeks and continued to improve until three months postoperatively, without any significant differences between the groups.

Figure 2.

Results of postoperative recovery measured with SF-36 questionnaire (mean ± SEM). The x-axis represents the time when the questionnaires were completed, before and after surgery. The HAL-RP group is represented in green, the TLRP group is represented in grey, and the ORP group is represented in blue. HAL-RP = hand-assisted laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy; TLRP = total laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy; wks = weeks; mnths = months; SF-36 = Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36.

Figure 3.

Results of postoperative recovery measured with the GIQLI questionnaire (mean ± SEM). The x-axis represents the time when the questionnaires were completed, before and after surgery. The HAL-RP group is represented in green, the TLRP group is represented in grey, and the ORP group is represented in blue. HAL-RP = hand-assisted laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy; TLRP = total laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy; wks = weeks; mnths = months; GIQLI = Gastrointestinal Quality of life Index.

A specification of costs is shown in Table 3. Costs for surgery were significantly higher in the TLRP group compared with both other groups, both because of the higher costs for material and the longer operating times. Total costs were 1864 euros less in the TLRP compared with the HAL-RP group. This difference, which was not statistically significant, can be explained by the shorter hospital stay in the TLRP group.

Table 3.

Results of median costs after TLRP vs. HAL-RP vs. ORP (in Euros)

| TLRP | HAL-RP | ORP | P value‡ | P value§ | P value∥ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized costs | ||||||

| Material during operation | 2,849 | 2,347 | 1,071 | — | — | — |

| Use of OR, including personnel (Euro/min) | 4.85 | 4.85 | 4.85 | — | — | — |

| Day of care at surgical ward | 1,055 | 1,055 | 1,055 | — | — | — |

| Creating Ileostomy | 87 | 87 | 87 | — | — | — |

| Closing Ileostomy | 83 | 83 | 83 | — | — | — |

| Relaparotomy | 87 | 87 | 87 | — | — | — |

| Relaparoscopy | 169 | 169 | — | — | — | — |

| Calculated costs for surgery (primary operation) | ||||||

| Costs for personnel + OR use (adjusted for operating time) | 1,445 (1,140–1,819) | 1,040 (723–1,940) | 645 (470–1,261) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total costs of operation (personnel + OR use + material) | 4,294 (3,989–4,668) | 3,387 (3,070–4,287) | 1,721 (1,541–2,332) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Calculated costs of admission | ||||||

| Costs for primary hospital stay | 9,495 (5,275–41,145) | 10,550 (5,275–32,705) | 11,605 (6,330–29,540) | 0.139 | — | — |

| Total costs for readmission for complications + stoma closure* | 4,220 (1,055–31,650) | 5,275 (5,275–16,880) | 5,275 (4,220–22,155) | 0.164 | — | — |

| Costs for admission (all days of admission) | 10,550 (5,275–69,630) | 13,188 (5,275–42,200) | 12,133 (7,385–43,255) | 0.381 | — | — |

| Total costs† | 14,864 (9,312–75,384) | 16,728 (8,364–46,468) | 13,405 (9,145–45,466) | 0.165 | — | — |

TLRP = total laparosopic restorative proctocolectomy; HAL-RP = hand-assisted laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy; ORP = open restorative proctocolectomy; OR = operating room.

Data are numbers or median costs per patient with ranges in parentheses unless otherwise indicated.

*For readmitted patients only.

†Total costs include all costs for surgery (use of OR + personnel, material, reoperations, costs for stoma), costs for admission, and costs for any readmission.

‡TLRP vs. HAL-RP vs. ORP (Kruskal-Wallis).

§TLRP vs. HAL-RP (Mann-Whitney U test).

∥TLRP vs. ORP (Mann-Whitney U test).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that compared with HAL-RP and ORP, TLRP offers no clinically significant short-term advantages, apart from an earlier return to diet. Moreover, it is associated with longer operating times and a tendency to a higher reintervention rate. It can be concluded that costs are comparable as the reduction in overall costs after TLRP counterbalances the increased surgical costs.

The presumption that a total laparoscopic approach in restorative proctocolectomy is associated with more favorable short-term results compared with a hybrid HAL-RP procedure could not be substantiated. Critics might argue that the applied total laparoscopic approach is a laparoscopic-assisted rather than a pure laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy, because pouch creation is performed extracorporeally. Extracorporeal stapling of the pouch and placement of the anvil of the circular stapler is a logical step, because an extraction incision has to be made to retrieve the colon and rectum. The only way to avoid an incision is to extract the colon and rectum through the anus.7 Consequently, the pouch is stapled laparoscopically, and a handsewn ileoanal anastomosis is performed transperineally after mucosectomy. In the latter procedure, the ileoanal anastomosis is performed extracorporeally, whereas in our approach the anastomosis is made laparoscopically.

Although not significantly so, the rate of reintervention was doubled after TLRP compared with HAL-RP but not because of anastomotic leak or pelvic abscess. Proportionally more patients in the TLRP group had UC (86 vs. 67 vs. 67 percent in the TLRP, HAL-RP, and ORP groups, respectively). Consequently, these patients were exposed to higher doses of immunosuppressive drugs. This also explains why more patients from the TLRP group received a primary protecting loop ileostomy (Table 1). Within all three groups, reoperations only occurred in those patients without a protecting ileostomy, except for one patient in the TLRP group who underwent reoperation for stoma necrosis.

Kienle et al.1 is one of the few authors who applied a total laparoscopic approach as well. In a consecutive series of 59 total laparoscopic proctocolectomies, the authors reported comparable operating times but an increased complication rate and an increased length of hospital stay compared with the present study. Moreover, conversion rate in the study by Kienle et al.1 was considerable (8 percent). The total laparoscopic approach, comprising a right hemicolectomy, left hemicolectomy, and rectum excision, probably makes the operation more vulnerable to complications, because the procedure is more difficult compared with, for instance, HAL-RP or open surgery.

Several studies comparing hand-assisted and true laparoscopic surgery for other procedures, such as sigmoidectomy or left hemicolectomy, concluded that the hand-assisted laparoscopic approach reduced operating times without affecting recovery.8–12 Little evidence is available regarding the role of hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery for restorative proctocolectomy. A study by Nakajima et al.,10 including only a small number of patients, noticed an increase in operating time using a pure laparoscopic compared with a hand-assisted technique, with equal morbidity and hospital stay. Noticeably, Larson et al.13 observed an increase in operating time after HAL-RP compared with TLRP. Hospital stay was one day shorter in the TLRP group, and in 6 percent of the cases a conversion to open surgery was necessary. In the present study, a stoma was constructed in only one-third of the patients and no conversions occurred. Because patients with a protecting loop ileostomy are known to have a shorter primary hospital stay, the present study and that of Larson et al.,13 in which all patients received a covering loop ileostomy, cannot readily be compared with respect to length of hospital stay.

So what is there to gain from a TLRP compared to a HAL-RP? In the present study, a significantly quicker extend to full liquid and normal diet was observed, which can partially be explained by the fact that almost half of the patients from the TLRP compared with one-third of patients in the HAL-RP and ORP groups received a protecting ileostomy. Obviously, this is of limited clinical relevance because it did not significantly influence length of hospital stay. However, the pouch catheter, residing for six days according to protocol, might have tempered the potential benefits of an earlier extend to normal diet in those patients without a protecting ileostomy. Interestingly, a reduction in hospital stay of two days after TLRP compared with ORP was observed as opposed to a difference of one day compared with HAL-RP. This decrease was not statistically significant.

There are some limitations to this study that could explain some of the differences in outcome between the study groups. As stated above, more patients in the TLRP group received an ileostomy. Because oral intake in patients with a defunctioning ileostomy is generally advanced quicker, this might have influenced the results. Another form of bias might be the fact that the more recently obtained results after TLRP were compared with a historic cohort of patients. The implementation of a fast-track care program for segmental colectomies in August 2004 at one of our surgical wards might have precipitated advancement of oral intake and mobilization. In this way, although discharge criteria and perioperative treatment in patients who underwent TLRP were similar to those who underwent HAL-RP and ORP between 2000 and 2003, some of the discharge criteria might have been fulfilled earlier. Finally, an allocation bias for laparoscopic surgery has been a possible confounding factor, because all patients referred to the laparoscopic surgeon were operated on by using a total laparoscopic approach, except for two patients who favored an open approach. However, compared with the HAL-RP, patients from the TLRP had to some extent less favorable preoperative characteristics, such as an older age, higher body mass index, and more patients with ulcerative colitis.

Cosmesis after laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy is considered superior to that after ORP. Although cosmesis after TLRP might be superior to that after HAL-RP, it is difficult to believe that a reduction of 2 cm in the size of the Pfannenstiel incision might influence cosmesis and body image significantly.14

There are no clear short-term advantages after TLRP compared with HAL-RP with respect to recovery, quality of life, and costs. There is however one important argument for TLRP: it is an excellent procedure for training surgeons in laparoscopic colorectal surgery because it comprises a total left and right hemicolectomy and a laparoscopic proctectomy. In teaching hospitals, this might compensate for the prolonged operating times.

Conclusions

A total laparoscopic technique for restorative proctocolectomy, apart from an earlier extend to normal diet, has no clinically relevant short-term advantages compared with an open and hand-assisted laparoscopic technique, because operating times are further prolonged, hospital stay and QOL are similar, and costs are comparable.

Acknowledgments

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Kienle P, Z’graggen K, Schmidt J, et al. Laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg 2005;92:88–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Marcello PW, Milsom JW, Wong SK, et al. Laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy: case-matched comparative study with open restorative proctocolectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:604–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Tilney HS, Lovegrove RE, Heriot AG, et al. Comparison of short-term outcomes of laparoscopic vs. open approaches to ileal pouch surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007;22:531–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Maartense S, Dunker MS, Slors JF, et al. Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis: a randomized trial. Ann Surg 2004;240:984–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, et al. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1055–68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, et al. Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg 1995;82:216–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Larson DW, Dozois E, Sandborn WJ, et al. Total laparoscopic proctocolectomy with Brooke ileostomy: a novel incisionless surgical treatment for patients with ulcerative colitis. Surg Endosc 2005;19:1284–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Chang YJ, Marcello PW, Rusin LC, et al. Hand-assisted laparoscopic sigmoid colostomy: helping hand or hindrance? Surg Endosc 2005;19:656–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Lee SW, Yoo J, Dujovny N, et al. Laparoscopic vs. hand-assisted laparoscopic sigmoidectomy for diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum 2006;49:464–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Nakajima K, Lee SW, Cocilovo C, et al. Laparoscopic total colostomy: hand-assisted vs. standard technique. Surg Endosc 2004;18:582–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Rivadeneira DE, Marcello PW, Roberts PL, et al. Benefits of hand-assisted laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy: a comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:1371–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Targarona EM, Gracia E, Garriga J, et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing conventional laparoscopic colostomy with hand-assisted laparoscopic colostomy: applicability, immediate clinical outcome, inflammatory response, and cost. Surg Endosc 2002;16:234–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Larson DW, Cima RR, Dozois EJ, et al. Safety, feasibility, and short-term outcomes of laparoscopic ileal-pouch-anal anastomosis: a single institutional case-matched experience. Ann Surg 2006;243:667–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Dunker MS, Bemelman WA, Slors JF, et al. Functional outcome, quality of life, body image, and cosmesis in patients after laparoscopic-assisted and conventional restorative proctocolectomy: a comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:1800–7. [DOI] [PubMed]