Abstract

In 2005, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation created Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change, a program to identify, evaluate, and disseminate interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in the care and outcomes of patients with cardiovascular disease, depression, and diabetes. In this introductory paper, we present a conceptual model for interventions that aim to reduce disparities. With this model as a framework, we summarize the key findings from the six other papers in this supplement on cardiovascular disease, diabetes, depression, breast cancer, interventions using cultural leverage, and pay-for-performance and public reporting of performance measures. Based on these findings, we present global conclusions regarding the current state of health disparities interventions and make recommendations for future interventions to reduce disparities. Multifactorial, culturally tailored interventions that target different causes of disparities hold the most promise, but much more research is needed to investigate potential solutions and their implementation.

Keywords: disparities, interventions, cardiovascular disease, depression, diabetes, breast cancer

In 2005, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) launched a major set of initiatives to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Prior studies have extensively documented the existence of disparities in both health care delivery and health outcomes. Minority patients receive lower quality of health care compared to white patients based on a variety of quality of care measures. For example, minority patients have lower process-of-care ratings and lower utilization of major medical procedures (Jha et al. 2005; Trivedi et al. 2005). The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has published an annual Disparities Report to provide a national overview of disparities data in both quality of care and access. The 2006 report documents that racial and ethnic minorities continue to receive poorer quality of care as compared to whites in 22 essential quality of care measures. Specifically, Hispanics receive poorer quality of care as compared to non-Hispanic whites in 77% of these measures, African Americans 73%, American Indians and Alaska Natives 41%, and Asian Pacific Islanders 32% (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2006). Despite the increasing public attention devoted to health disparities and the growing public investment in quality improvement interventions, significant racial and ethnic disparities in care and outcomes still exist for many conditions, including those that are the focus of this supplement: cardiovascular disease, diabetes, depression, and breast cancer (McGlynn et al. 2003; Smedley, Stith, and Nelson 2003; Trivedi et al. 2005; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2006; Vaccarino et al. 2005).

In 2003, the Institute of Medicine published Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, a landmark book that reviewed disparities and further raised consciousness of this issue in the national policy arena (Smedley, Stith, and Nelson 2003). Unequal Treatment provides an important conceptual framework for thinking about the sources of and solutions for health disparities. The book discusses sources of disparities at the patient, clinical encounter, and system levels. It also outlines general system and cross-cultural education interventions to reduce disparities. While this conceptual framework for addressing disparities has been invaluable, the most urgent needs are to develop specific solutions, identify the interventions that are most effective, and implement them in the real world.

In 2005, RWJF initiated a program titled Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change to encourage, evaluate, and disseminate new interventions to reduce disparities (www.solvingdisparities.org). Finding Answers is part of a broad RWJF portfolio of disparity reduction programs that examine factors ranging from quality of care, access to care, insurance coverage, language issues, and legal barriers to reducing disparities (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Disparities Interest Area 2007). The Institute of Medicine identified equity as one of the six fundamental domains of high-quality care (Institute of Medicine 2001). In the past, RWJF had separate Quality of Care and Disparity Teams within their organization. Recognizing the integral nature of equity as part of high-quality care, RWJF has recently combined these two teams into one Quality/Equality Team to work on these issues. Finding Answers is a specific program of the RWJF Quality/Equality Team that integrates quality improvement and disparity reduction.

This supplement of Medical Care Research and Review is part of the RWJF effort to reduce disparities and one of the responsibilities of the Finding Answers project. The specific aims of the supplement are to (1) review what interventions reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care in cardiovascular disease, diabetes, depression, and breast cancer; (2) assess the evidence for the effectiveness of culturally tailored interventions; and (3) analyze existing evidence on the effect of pay-for-performance and public reporting of performance measures on reducing disparities, and explore potential barriers and solutions to their successful implementation for narrowing disparities. All four conditions examined in this supplement have a high prevalence, cause significant morbidity and mortality, have clear standards of care, and have large documented disparities in care. Cardiovascular disease, depression, and diabetes are the three disease foci of the RWJF effort, and evidence from the breast cancer disparity intervention field can help inform the approach to those three diseases. We recognize that health disparities originate from societal factors such as poverty and unequal education (Marmot 2002; Schnittker 2004). We also recognize that larger health care policy issues such as limited access to health care contribute significantly to health disparities (Health Policy Institute of Ohio 2004; Smedley, Stith, and Nelson 2003). While addressing these issues may be necessary to completely eliminate health disparities, we realize that some of these issues are simply beyond the scope and control of health care organizations, providers, and payors. These entities need concrete recommendations regarding what they can do to reduce disparities in their environments. In light of this need, we have chosen to focus the content of this supplement on health care-oriented quality improvement interventions and some of the financial and policy interventions that impact quality improvement. As a complementary tool to this supplement, the Finding Answers Web site (www.solvingdisparities.org) has a searchable database that contains summaries of these individual interventions.

Throughout this discussion it is important to recognize that race is a complex, multifaceted term with several different conceptualizations (West and Walther 1994). For the purposes of this supplement, we treat race primarily as a sociopolitical construct with its attendant limitations (Fisher et al. 2007). Our practical focus is on those elements of race relevant for disparities in the health care system.

New Contribution

This introductory paper presents an overarching conceptual model to help guide readers through the remaining papers. It also summarizes the key findings, themes, and lessons from the other six articles. The paper ends with several global conclusions and recommendations.

Conceptual Model of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care

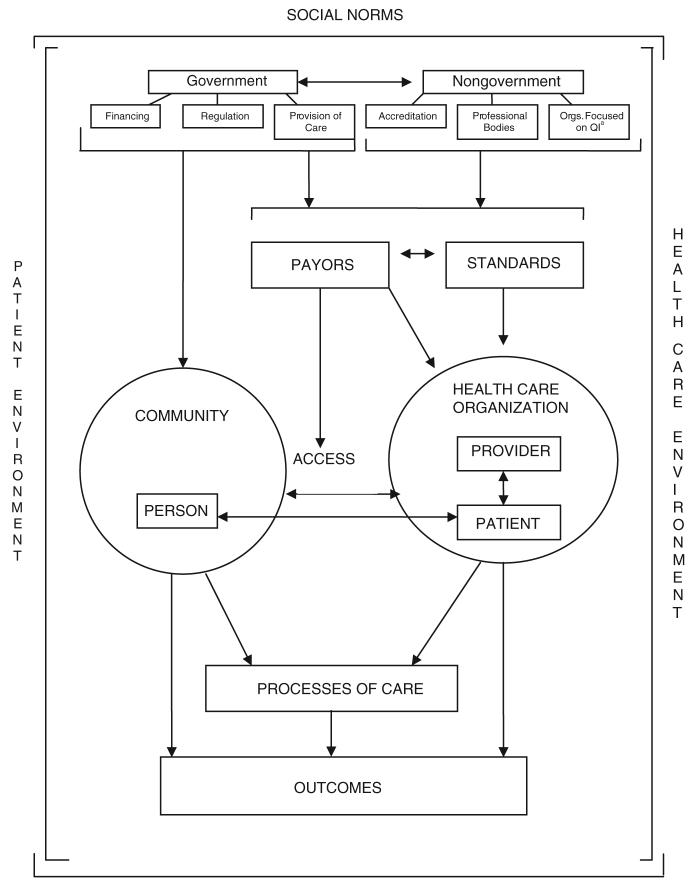

Figure 1 presents the overarching conceptual model for disparities that the individual papers explore in more detail. While a number of other conceptual frame-works exist (Cooper, Hill, and Powe 2002; Jones 2000; King and Williams 1995; Kressin 2005; Smedley, Stith, and Nelson 2003; Williams, Lavizzo-Mourey, and Warren 1994), our model is specifically designed to facilitate understanding of the diverse interventions covered in our review papers. As represented by the vertical brackets on the borders of figure 1, a patient environment and health care environment encompass everything from governmental policies to community and health care organizations. Focusing first on the central circles in the diagram, individuals go back and forth between being persons in the community and patients in a health care organization. Important events can occur in both settings that affect processes of care and outcomes. For example, providers may order a series of diagnostic tests and treatments that impact the health of patients. This medical care can affect the entire spectrum of health and illness, from preventive care to acute illness to chronic disease management. The role of the community is also critical. The bulk of patient self-management of chronic illness takes place in the community, such as monitoring symptoms, taking medications, and participating in programs of physical exercise and healthy eating. In addition, persons are surrounded by social networks of peers and families that influence attitudes and behavior, and healthy choices are influenced by environmental factors such as the availability of fruits and vegetables in the local markets.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model for Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care.

a. Orgs. Focused on QI = Organizations Focused on Quality Improvement.

Americans’ access to health care is variable, and as demonstrated by the arrows between the community and health care organization circles, interventions that create linkages between communities and health care systems may improve access to care and subsequently improve health status. These range from national policy interventions such as the provision of adequate health insurance, to the use of community health workers or promotoras who can play liaison, case-management, cultural translation, and patient advocacy roles. Thus, community and health care organization environments exist for the individual person/patient, and there are ways to integrate these two worlds more seamlessly. Social norms, including subtle forms of racism, are suffused throughout both of these environments, represented by the overarching horizontal bracket at the top of figure 1.

Interventions in the health care organization and the larger health system are the primary focus of the Finding Answers program. Within the health care organization circle, a variety of quality improvement initiatives may lead to better delivery of care processes and ultimately better health care for minority populations. Productive communication and interaction between providers and patients are essential, and thus cultural competency programs for providers and empowerment programs that encourage patients to be more active partners in their care are examples of possible interventions. As previously noted, innovative ways to link the health care organization and community are needed.

The upper half of figure 1 demonstrates that the interactions of persons with providers, health care organizations, and the community occur within wider political and economic environments. Both government and nongovernment organizations can influence health care organizations and, more indirectly, the community through payment mechanisms and the creation of standards. Payors include Medicare, Medicaid, private insurers, and managed care companies. Standards can be based on laws, regulations, or scientific evidence. Federal and state governments have an enormous impact on health through the financing, regulation, and provision of care. For example, well-designed policies that provide financial incentives to improve quality of care and reduce disparities may have benefits (Chien et al. 2007). Nongovernmental accreditation organizations, professional bodies, and organizations focused on quality are some of the other entities that affect payors and standards.

These payors and standards, represented by boxes in the top third of figure 1, can be intermediaries linking the decisions of governmental and nongovernmental bodies to the actions of health care organizations. Payors also influence access to care. For payors, key levers affecting disparities include decisions about who pays, whom does one pay, what does one pay for, how does one pay, how much does one pay, and who has access to care and health insurance? Governmental and nongovernmental organizations can create standards that either directly or indirectly affect health disparities. For example, antidiscrimination and access to care laws such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the 1986 Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) antidumping legislation (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2007), and more recent interpreter and cultural competency laws may reduce disparities (Gibbs et al. 2006; Ladenheim and Groman 2006). Accreditation and manpower regulations such as licensure and scope of practice rules affect the supply of providers and health care facilities serving minority populations. Scientific evidence and practice guidelines by a variety of organizations set the standard of care, and thus some of the targets for the quality of care to be received by all. Decisions by states and private organizations such as the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA) to publicly report quality of care data also implicitly create a standard of care that health providers will strive for (National Committee on Quality Assurance 2007).

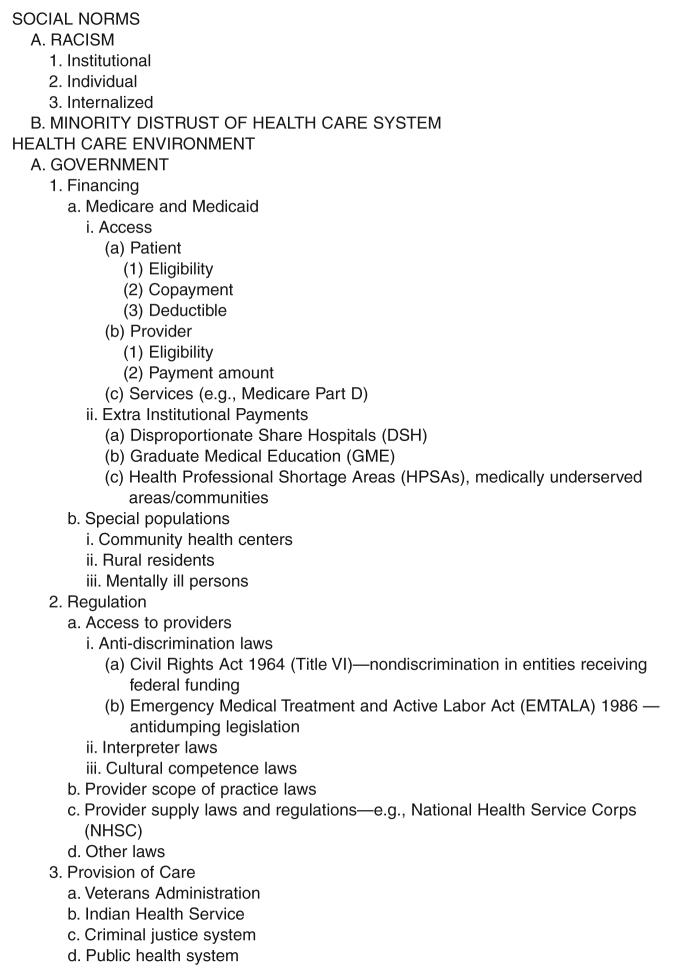

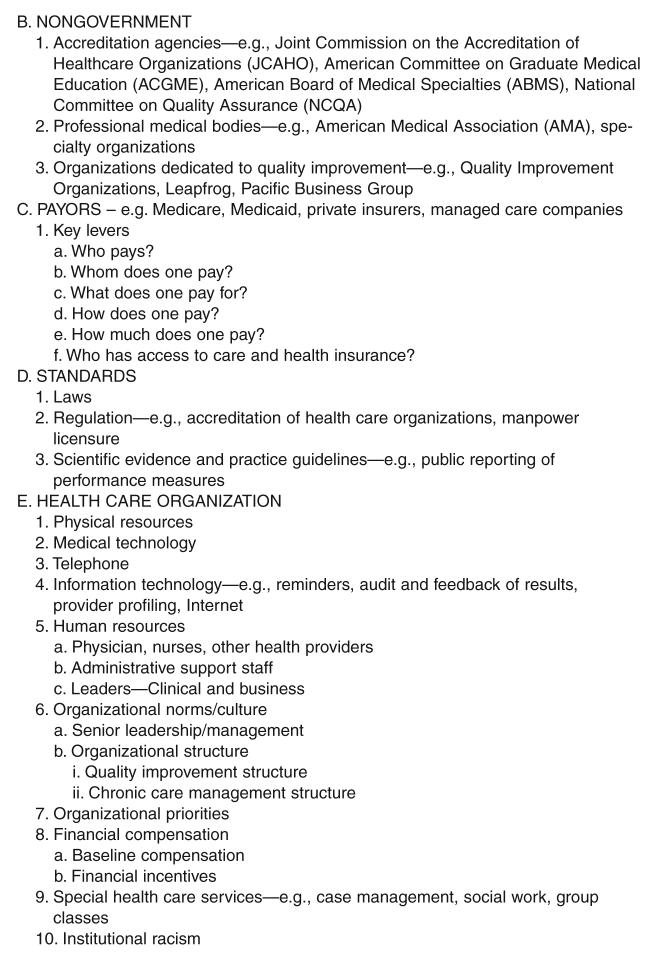

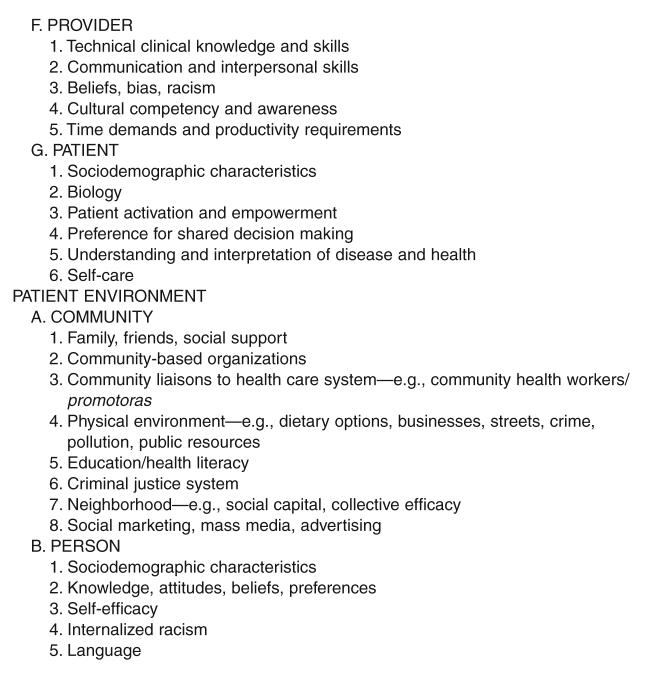

Figure 2 outlines the factors in the conceptual model in more detail, and these concepts are developed more fully in some of the other papers in this supplement (Chien et al. 2007; Fisher et al. 2007). A number of excellent descriptions of the governmental financing and regulatory policy levers exist (Baquet, Carter-Pokras, and Bengen-Seltzer 2004; Beal 2004; Frist 2005; Kennedy 2005; Lurie 2002; Lurie, Jung, and Lavizzo-Mourey 2005; Tang, Eisenberg, and Meyer 2004), and thus will not be repeated in this supplement.

Figure 2. Key Domains in the Conceptual Model for Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care.

Key Questions

The key question is what actually works for reducing racial and ethnic disparities in health care. The answers range from individual provider and patient interventions to ones geared toward improving the health care organization, linkages to the community, and policies affecting the behavior of individuals and organizations. Another question that recurs throughout this supplement is whether culturally tailored interventions are more effective at reducing health care disparities than generic quality improvement approaches. A related question is whether population-based general performance incentives are sufficient to reduce disparities, or whether specific incentives tied to the goal of reducing health disparities need to be created and promoted.

Lessons Learned from Each Paper

This section summarizes the key findings of the six papers in this supplement. The purpose is to provide a broad overview of disease-specific health care interventions designed to reduce health disparities as well as policies and issues related to health systems’ ability to impact disparities. We refer the reader to each of the remaining papers for a full discussion of the issues.

Cardiovascular Disease

Davis et al. comprehensively review interventions designed to reduce disparities in the management of cardiovascular risk factors, coronary artery disease, and heart failure (Davis et al. 2007). The health disparities intervention literature in cardiovascular disease has been more heavily focused on control of cardiovascular risk factors than disease management; among risk factors that have been studied, hypertension and tobacco use have received the greatest amount of attention. Apart from issues of intervention focus, an important limitation of the existing cardiovascular disparities intervention literature is that interventions have been evaluated in individual minority populations, and very few intervention studies have formally assessed changes in disparities as a primary outcome.

Hypertension

Among the hypertension interventions, there has been variety in the focus of intervention studies, ranging from studies targeting patients and family members to providers and health care organizations. Of the interventions focused on patients or families, interventions that promoted sodium restriction modestly improved blood pressure outside experimental settings, and exercise, weight loss, and psychosocial interventions also had limited real-world effectiveness. At the provider and organization level, interventions that involved clinic reorganization or multidisciplinary teams of health care providers appeared to produce beneficial effects on blood pressure in minority populations. Among the interventions using multidisciplinary teams, nurseled interventions were common and produced beneficial effects on blood pressure control. Pharmacist and community-health worker interventions were also effective, but the total number and size of studies evaluating these interventions were both small.

Tobacco Cessation

Tobacco cessation interventions were the next most common cardiovascular interventions. Patient-directed pharmacologic interventions such as buproprion have been shown in African Americans to be effective, especially when combined with counseling. However, the effectiveness of these common therapies has been less frequently studied in other minority groups. Efforts have been made to culturally tailor health education on smoking cessation to African American and Hispanic populations; these interventions have had mixed results, with heterogeneity in the study populations and interventions limiting the conclusions that can be drawn. Organization-wide tobacco cessation programs have been more effective compared to isolated provider-targeted education programs.

Hyperlipidemia and Physical Inactivity

There have been relatively fewer studies in the areas of hyperlipidemia and physical activity. Interventions designed to improve lipid levels in minority populations have had mixed results; however, several interventions intended to bring about overall improvements in cardiovascular risk factors via clinic reorganization or care management with nurses have successfully improved lipid levels. Patient-level interventions designed to increase physical activity have had mixed results and have been marked by high dropout rates. While some study results are particularly promising, there are too few studies in this area to draw definitive conclusions regarding the ideal intervention to increase physical activity in ethnic/racial minorities.

Coronary Artery Disease and Heart Failure

For acute coronary artery disease management, surprisingly there are no studies describing attempts to improve acute coronary heart disease care. One study of post-myocardial infarction care of depression and social support was not effective in racial/ethnic minorities. There have been relatively more interventions for heart failure management. Among these studies, care management programs consisting of patient education, specialty nurse case management, frequent telephone follow-up, and heart failure specialist oversight, have decreased hospitalizations in the subset of patients with advanced heart failure. The interventions have not been extrapolated to patients with milder degrees of heart failure. In addition, the value of racially and ethnically tailored care has not been well studied. Finally, implementing study interventions in minority populations under everyday, nonexperimental, real-world conditions has not been explored in much detail.

Diabetes

Peek et al. analyzed diabetes interventions including patient, provider, health care organization, and multitarget efforts (Peek, Cargill, and Huang 2007). For each of these intervention categories, diabetes care interventions have successfully improved processes of diabetes care such as regular physical activity and intermediate outcomes such as mean glucose levels. While these findings are quite promising, diabetes care studies have typically been conducted over relatively brief periods of time (12 months or less) and questions remain regarding whether the benefits of these interventions can be sustained and lead to long-term improvements in disparities in diabetes-related complications.

Patient

All patient interventions were educational activities that focused primarily upon improving patients’ diet, physical activity, and self-management. Culturally tailored interventions generally improved knowledge and health behaviors, and had variable effects on health outcomes (e.g., glucose levels). In meta-analysis, culturally tailored interventions had a larger mean absolute reduction in HgbA1c values (0.69%) when compared to general quality improvement interventions (0.1% mean absolute reduction) (Peek, Cargill, and Huang 2007). Interventions that incorporated peer support and one-on-one interactions reported positive results more frequently than those using computer-based education and online self-management coaching.

Provider

Problem-based education to increase use of practice guidelines, provider feedback, and computerized patient-specific reminders generally improved processes of care and outcomes. In-person feedback was superior to computerized decision-support in effecting sustained provider behavioral change and improvement in diabetes and blood pressure control. Primary care providers who received feedback and reminders had patients with equivalent diabetes control as those seen in the diabetes specialty clinic, indicating real promise for provider interventions to impact health outcomes.

Health Care Organizations and Community

Studies of interventions provide strong evidence that organization-level interventions and interventions incorporating both health care organizations and the community can improve diabetes care outcomes. A registered nurse serving as case manager and/or clinical manager using treatment algorithms led to large improvements in glucose, blood pressure, and lipid control, particularly when nurses were used as clinicians. The addition of community health workers added peer support and community outreach; the combination of nurses and community health workers was superior to interventions using only nurses or community health workers. Pharmacist-led medication management and patient education have also improved glucose control. Rapid glycosylated hemoglobin measurement technology and medication assistance programs have also shown promise.

Multitarget

Interventions that target a combination of patients, providers, multiple health care organizations, and health care systems frequently improved processes of care and outcomes. These interventions often used multidisciplinary teams and patient registries. These projects included a variety of interventions such as patient education, nurse case management, treatment algorithms, community outreach with community health workers, patient incentives, continuous quality improvement, and group visits. A comprehensive REACH 2010 project reduced racial and ethnic disparities (Jenkins et al. 2004). This ambitious project consisted of a coalition of health care and academic institutions, community-based and faith-based organizations, civic groups, libraries, professional associations, government and business organizations, and local media. This community-based participatory research project included patient (education, empowerment), communities (community health worker, community-based case management, coalition building, advocacy), provider (audit/feedback), and health care organization (patient registries, continuous quality improvement) change. This is one of the few interventions that formally measured and demonstrated a reduction in racial disparities. Another project combining physician (electronic chart reminders), patient (automated letters, laboratory orders), and health systems change (diabetes registry), but no community partnerships reduced the disparity in LDL cholesterol testing and control.

Depression

Van Voorhees et al. found that multicomponent interventions, using either chronic disease management or collaborative care models that affect the larger health care system, health care organization, provider, and person-level factors, improved the health outcomes of ethnic minorities with depression (Van Voorhees et al. 2007). The interventions addressed the continuum of factors in the process from individual patient assessment for depression to navigation through the health care system. Specifically, the interventions addressed evaluation, initiation of treatment, completion of treatment, payment structure, limited supply of mental health specialists and referral system fragmentation. The core component of each of these interventions was active case management by a trained lay person, nurse, or social worker. Successful interventions have occurred for meeting the standards of both cognitive behavioral psychotherapy and antidepressant medication treatment for depression. Culturally tailored programs including bilingual providers, language-appropriate educational materials, and case management tailored to low-income patients have been effective. Results from single-component interventions employing screening and physician reminders, physician detailing, or patient education materials have not demonstrated clear benefit.

Breast Cancer

Masi et al. reviewed interventions to reduce breast cancer disparities, focusing on screening, diagnostic testing, and treatment (Masi, Blackman, and Peek 2007). Just as Davis et al. found an asymmetric distribution of studies on the various aspects of cardiovascular disease disparities interventions (Davis et al. 2007), the majority of interventions addressing breast cancer disparities have focused on breast cancer screening, while relatively few studies have examined interventions to help patients who have an abnormal mammogram or breast cancer. The research focus on screening interventions mirrors the unique legislative history of breast cancer care. Since 1990, federal funds have been available to help uninsured women obtain mammography through the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP). While this led to increased screening, the NBCCEDP did not include funding for certain diagnostic procedures and breast cancer treatment. The Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 2000 was designed to bridge this gap, but relatively few studies have focused on treatment interventions funded through this legislation.

Screening

Patient Only

Reminder letters frequently increase mammography screening rates in women of higher socioeconomic status but were less effective among women of lower socioeconomic status and women without a prior source of care. More intensive interventions such as culturally tailored educational videos and education increased breast cancer knowledge, intention to seek screening, and actual screening rates. Interventions that addressed financial and logistical concerns were more effective than reminder-based systems among low-income women. These interventions include same-day mammography, assistance with transportation and child care, and free mammograms.

Provider

Physician chart reminders were generally more effective than patient reminders. However, combinations of provider and patient reminders were frequently not effective in clinics serving racially and ethnically diverse populations in busy, resource-constrained settings. Interventions designed to increase clinical breast examination had mixed results. For interventions targeting physicians alone, chart reminders, chart flow sheets, and administrative assistance completing radiology requisition forms improved adherence to mammography screening guidelines.

Expedited Diagnostic Testing and Treatment

As discussed earlier, relatively few interventions have examined disparities in diagnostic testing or treatment, the stages of care that are natural consequences of breast cancer screening. Case management has been found to help reduce time to follow-up and time to breast biopsy. Interventions ranged from low-intensity case tracking and telephone follow-up, to more intensive coordinated care models, and sociomedical models that encompass financial, social service, and psychological assistance. For breast cancer treatment, performance measures for cancer treatment are currently being developed. A nurse case management intervention led to higher rates of breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy.

Culture

Fisher et al. encourage the use of the term “cultural leverage,” defined as “a focused strategy for improving the health of racial and ethnic communities by using their cultural practices, products, philosophies, or environments as vehicles that facilitate behavior change of patients and practitioners. Building upon prior strategies, cultural leverage proactively identifies the areas in which a cultural intervention can improve behaviors and then actively implements the solution” (Fisher et al. 2007: 245S). Culture has both surface characteristics such as dress, music, and colors, as well as deeper characteristics encompassing values and assumptions. Cultural leverage can be accomplished by activating shared norms and expectations and making health care systems cognizant of cultural practices. Cultural interventions can be targeted to a group or tailored to an individual. Cultural leverage also inherently addresses racism. Race is primarily a sociopolitical construct. Fisher et al. draw upon the work of Camara Jones in conceptualizing institutional racism, individually mediated racism, and internalized racism (Jones 2000). Institutional racism leads to differential access to goods, services, and opportunities. Individually mediated racism can be either prejudice, meaning differential assumptions about persons based upon race, or discrimination, which is differential action based upon race. Internalized racism is acceptance by stigmatized races of negative messages about their abilities and intrinsic worth.

Fisher et al. conceptualize cultural interventions occurring at three possible levels: individual as person/patient, access, and health care environment. Individual-oriented interventions modify health behaviors of individuals within communities. Access-oriented interventions increase the community’s access to the existing health care system. Health care environment interventions modify the health care system or organization to more effectively serve patients and communities.

Thirty-eight studies are included in Fisher et al.’s review. Sixteen studies used self-reported outcomes and 7 had positive results. All 6 qualitative studies reported positive findings. Sixteen of the studies used objective health-related measurements and were all positive. Many interventions focused on intermediary factors such as patient self-efficacy or provider cultural competence that may be important in the evaluation of health disparities.

Several themes emerged from these results. Many promising interventions focused on nurses as the key personnel for implementing interventions. One possible interpretation is that nurses, on average, might have more detailed insight into how race affects care. Physician interventions were typically of short duration and generally concentrated on cultural competency or language tool training. Prevention interventions focused on promoting healthy lifestyles, improving self-esteem, and enhancing self-efficacy. These cultural tools were designed to mitigate internalized racism, such as among substance abuse clients who might have a poor image of themselves. Self-efficacy was addressed through interventions including role models and culturally congruent programming and communication strategies. These interventions attempted to improve self-worth and ability to interact with others in the health care system.

Performance Incentive Programs: Pay-for-Performance and Public Reporting

Chien et al. examined how performance incentive programs, such as pay-for-performance and public reporting of performance measures, can impact disparities (Chien et al. 2007). They reviewed existing studies on performance incentive programs and disparities, and performed semistructured interviews of key leaders, representing private and governmental health plans and payors, for their views on their incentive programs and their potential relationship with health disparities. They argue that whether such performance incentive programs narrow, widen, or maintain disparities depends upon how well the plans promote an inclusive approach to diverse populations and avoid “cherry picking” and other schemes that reward rich health plans, hospitals, and health care organizations at the expense of those caring for the poor. The first argument draws upon empirical work in the literature that suggests that uniform approaches to quality improvement may not be as effective in minority populations. Consequently, reducing health disparities may require programs that are culturally tailored to minority populations, involve specific health plan/hospital incentives for improving the health of minorities, or both.

“Cherry picking” can occur when physicians or health plans have an incentive to avoid or disenroll minority patients who may be more challenging to provide quality care for. Risk adjustment has been proposed as one solution, but poorly designed systems could lock in preexisting disparities if the case-mix adjustment schemes essentially excuse providers for providing poor care to minorities. The “rich get richer” thesis is that wealthy organizations caring for higher socioeconomic status patients may have an easier time reaching absolute levels of quality performance. Rewarding relative improvement toward an absolute standard is one potential remedy.

Chien et al. found only one study in the literature that explicitly examined the effect of performance incentive programs on disparities. This one study, an examination of New York State’s cardiac surgery report card system, found an increase in racial and ethnic disparities in coronary artery bypass graft surgery rates following the implementation of the report card system (Werner, Asch, and Polsky 2005). In interviewing leaders of 15 programs implementing pay-for-performance programs, Chien et al. found that most were aware that the new payment schemes could affect disparities, but few were explicitly designing their system to increase the chance that racial and ethnic disparities would narrow. Leaders of only four programs thought they could identify racial and ethnic groups in need of culturally tailored interventions, and only one leader said the organization was specifically addressing the needs of minority groups. Chien et al. concluded that there needs to be more explicit attention to thinking about how policies affect disparities if we are to maximize the chance of improvement for all and reduce disparities.

Summary Conclusions

How does one make sense of this complicated literature on reducing racial and ethnic disparities in care and outcomes? While there is an immense general quality improvement literature, relatively few studies have specifically examined how to improve quality of health care for minorities and even fewer studies have identified the reduction of health disparities as an outcome. However, the evidence presented in this supplement identifies promising intervention strategies and questions that need to be addressed in future intervention studies.

Promising Intervention Strategies

Multifactorial interventions that address multiple levers of change. Without improving multiple components or stages of care for a given condition, we lessen our chances of reducing disparities in what ultimately matters, major health outcomes. For example, increasing breast cancer screening is only useful if patients have timely diagnostic testing after an abnormal mammogram and appropriate treatment for breast cancer (Masi, Blackman, and Peek 2007). Effective depression interventions addressed evaluation, treatment, completion of treatment, access to providers, and payment (Van Voorhees et al. 2007). Some of the most powerful diabetes interventions targeted patient, provider, organization, and community factors simultaneously (Peek, Cargill, and Huang 2007). Simple magic bullets or interventions that successfully address health disparities by modifying a single barrier are likely to be elusive.

Culturally tailored quality improvement. Culturally tailored approaches to care may improve care for ethnic minorities by providing a mechanism for individualizing care. All four disease-specific reviews discussed the importance of individualized care to improving outcomes (Davis et al. 2007; Masi, Blackman, and Peek 2007; Peek, Cargill, and Huang 2007; Van Voorhees et al. 2007). Ultimately the specific barriers facing particular individuals, communities, and health care organizations need to be addressed. Such individualized care may account for why case managers, community health workers, and culturally tailored counseling showed promise across the different conditions. Few studies have directly compared culturally tailored interventions to generic quality improvement techniques. Despite this lack of evidence, there are theoretical and practical reasons to believe that cultural tailoring may enhance the effectiveness of general quality improvement interventions among ethnic minority groups. Confirmation of this hypothesis is needed in prospective trials.

Nurse-led interventions within the context of wider system change. These programs are often more effective than interventions that target physicians and the office visit. The reasons are probably multifactorial. Nurses are more cost-effective, which may permit more time with patients. They are familiar and comfortable working in teams, are traditionally more patient-centered, and by training and background may be more likely to use appropriate culturally tailored approaches. Which of these factors contribute the most to the effectiveness of nurses in reducing health care disparities for racial minorities is unknown. Nurses, in collaboration with pharmacists and community health workers, may be well suited to address transitions from the hospital to home or intermediate care, and to improve well-being, access, and adherence between clinic visits, issues that are especially important in vulnerable populations.

Questions for Future Research

What parts of a multicomponent intervention provide the most value? While multicomponent interventions are generally more effective than single-component interventions, an inevitable tension arises between implementing expensive multicomponent programs and accounting for the limited financial resources and staff time of an organization. The practical questions for organizations are whether the various components of such an intervention can be prioritized, if there can be a tiered rollout of some multicomponent interventions, and what gives the most value or “bang for the buck.” We found essentially no studies evaluating the economic value of efforts designed to reduce health disparities. The development of effective strategies for improving care or reducing disparities does not ensure that such programs will be adopted by health care providers or widely disseminated by policy makers. Analyses that examine the business case for quality and disparities reduction as well as societal cost-effectiveness analyses are critical for managers and policy makers (Huang, Brown, et al. in press; Huang, Zhang, et al. in press).

How can interventions developed in the research setting be successfully implemented in other organizations and patient populations? Studies have been conducted in a variety of settings such as community health centers, private doctors’ offices, and academic health centers. However, few studies provide much detail on how to implement study interventions in minority populations under everyday, real-world conditions. For example, administrative and clinical leadership, financial viability, and nursing staffing patterns are important practical issues that frequently are not addressed in evaluations of interventions. Research to inform implementation of disparity interventions and practical tools for implementing interventions are greatly needed (Greenhalgh et al. 2004).

Given heterogeneity within each type of intervention, what conclusions can be made about the effectiveness of classes of interventions? For example, each of the four clinical reviews in this supplement describe interventions using cultural tailoring, community health workers, and case management (Davis et al. 2007; Masi, Blackman, and Peek 2007; Peek, Cargill, and Huang 2007; Van Voorhees et al. 2007). Interventions using these tools often vary considerably, even within the same disease category. Thus, overarching conclusions about intervention types must be viewed cautiously. Answers to questions such as how intensive do interventions need to be, what are the critical components of the intervention, and how much follow-up and monitoring are necessary for success depend upon more detailed information.

What interventions reduce disparities in understudied populations such as American Indian and Asian American subgroups, and pediatric and geriatric ethnic subgroups? We found in our literature review that the majority of health disparities interventions focus on adult African American and Latino patients. It is important to realize that health disparities may exist for other important groups and subgroups such as American Indians, Asian Americans, and minority persons at either end of the age spectrum. These groups may require unique solutions.

How can we comprehensively integrate the strengths of the community and health care system? The most common interventions linking community to health care system are limited community health worker projects. However, projects that seamlessly and comprehensively link a number of community and health care system organizations and networks, such as the REACH 2010 project included in Peek et al.’s review (Peek, Cargill, and Huang 2007) are rare.

What effect do policies linking quality to payment and other performance incentives have on disparities? Pay-for-performance and public reporting of performance measures are currently being enacted throughout the country. Disturbingly, there is essentially no literature evaluating the effectiveness or potential harms of these policies on disparities. This literature void is stunning given the high level of interest in these performance incentive schemes. Regional and national demonstration projects are greatly needed with a specific focus on health disparities effects. For example, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have a number of general pay-for-performance demonstration projects underway (U.S. Senate 2005), and the RWJF has a new program titled Aligning Forces for Quality that tests regional interventions that incorporate public reporting of performance measures, quality improvement, and consumer engagement (Aligning Forces for Quality 2007). These demonstration projects could specifically include health disparity measurement as part of their assessment of quality of care and outcomes.

Our country needs innovative solutions to the problem of health disparities, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change program is attempting to fill in key gaps in our knowledge of what interventions reduce racial and ethnic disparities in care. The program requires traditional criteria of academic rigor and innovation among grantees, but also emphasizes practical real-world lessons and requires elucidation of implementation issues and financial ramifications of the projects. Addressing these gaps in knowledge is critical to the field and needs to be a higher priority among funders and journals seeking to promote real-world translational research. Finding Answers seeks a broad range of interventions focused upon reducing disparities and increasing quality within the health care system including policy interventions, organizational quality improvement interventions, solutions targeted at patients, nurses, and/or physicians, and projects that link and integrate the strengths of the community and health care system. Of note, the new Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Quality/Equality Team also includes members of the former RWJF Nursing Team, which will facilitate study of interventions involving nurses, allied health personnel, and community health workers.

The United States still has a great distance to travel before racial and ethnic disparities in care can be eliminated, and relatively few projects have studied how to specifically reduce these differences. However, there is reason for optimism based upon the early lessons from the existing literature reviewed in this supplement. More research will fill these gaps in our knowledge, and wise management and public policy can facilitate the creation, adoption, and spread of successful interventions. We hope readers will use this supplement to enhance their knowledge and problem-solving in this critical area as they contribute to the solutions ending racial and ethnic disparities in care and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change Program, the Department of Medicine at the University of Chicago, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Diabetes Research and Training Center (P60 DK20595). Dr. Chin is also supported by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K24 DK071933). Dr. Huang is supported by a Career Development Award from the National Institute on Aging (K23 AG021963).

References

- Aligning Forces for Quality 2007[accessed April 12, 2007]Available from http://www.forces4 quality.org/

- Baquet CR, Carter-Pokras O, Bengen-Seltzer B. Healthcare disparities and models for change. American Journal of Managed Care. 2004;10:SP5–11. Spec No. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal AC. Policies to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in child health and health care. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2004;23(5):171–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.5.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services EMTALA: An Overview[accessed April 16, 2007]2007Available from http://www.cms.hhs.gov/EMTALA/

- Chien AT, Chin MH, Davis AM, Casalino LP. Pay-for-performance, public reporting, and racial disparities in health care: How are programs being designed? Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(5 Suppl):283S–304S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Hill MN, Powe NR. Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17(6):477–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AM, Vinci L, Okwuosa T, Chase A, Huang ES. Cardiovascular health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(5 Suppl):29S–100S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher TL, Burnet DL, Huang ES, Chin MH, Cagney KA. Cultural leverage: interventions using culture to narrow racial disparities in health care. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(5 Suppl):243S–282S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frist WH. Overcoming disparities in U.S. health care. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2005;24(2):445–51. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs BK, Nsiah-Jefferson L, McHugh MD, Trivedi AN, Prothrow-Stith D. Reducing racial and ethnic health disparities: Exploring an outcome-oriented agenda for research and policy. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2006;31(1):185–218. doi: 10.1215/03616878-31-1-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82(4):581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Policy Institute of Ohio . Understanding health disparities. Health Policy Institute of Ohio; Columbus, OH: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Huang ES, Zhang Q, Brown SES, Drum ML, Meltzer DO, Chin MH. The cost-effectiveness of improving diabetes care in U.S. federally-qualified community health centers. Health Services Research. 2007 2007 May 16; doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00734.x. OnlineEarly Articles. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ES, Brown SES, Zhang JX, Kirchhoff AC, Schaefer CT, Casalino LP, Chin MH. The cost consequences of improving diabetes care: The community health center experience. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34016-1. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C, McNary S, Carlson BA, King MG, Hossler CL, Magwood G, Hendrix K, Beck L, Linnen F, Thomas V, Powell S, Ma’at I. Reducing disparities for African Americans with diabetes: Progress made by the REACH 2010 Charleston and Georgetown diabetes coalition. Public Health Reports. 2004;119(3):322–30. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AK, Fisher ES, Li Z, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Racial trends in the use of major procedures among the elderly. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(7):683–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa050672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CP. Levels of racism: A theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. American Journal Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy EM. The role of the federal government in eliminating health disparities. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2005;24(2):452–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G, Williams DR. Race and health: A multidimensional approach to African-American health. In: Amick BC, Levine S, Tarlov AR, Walsh DC, editors. Society and health. Oxford University Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kressin NR. Separate but not equal: The consequences of segregated health care. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2582–4. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.577635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladenheim K, Groman R. State legislative activities related to elimination of health disparities. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2006;31(1):153–83. doi: 10.1215/03616878-31-1-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie N. What the federal government can do about the nonmedical determinants of health. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2002;21(2):94–106. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie N, Jung M, Lavizzo-Mourey R. Disparities and quality improvement: Federal policy levers. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2005;24(2):354–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. The influence of income on health: Views of an epidemiologist. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2002;21(2):31–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi CM, Blackman DJ, Peek ME. Interventions to enhance breast cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment among racial and ethnic minority women. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(5 Suppl):195S–242S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, Kerr EA. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348(26):2635–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Committee on Quality Assurance 2007[accessed April 16, 2007]Available from http://www .ncqa.org/

- Peek ME, Cargill A, Huang ES. Diabetes health disparities: A systematic review of health care interventions. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(5 Suppl):101S–156S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Disparities Interest Area 20072007[accessed April 2, 2007]Available from http://www.rwjf.org/portfolios/interestarea.jsp?iaid=133

- Schnittker J. Education and the changing shape of the income gradient in health. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2004;45(3):286–305. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang N, Eisenberg JM, Meyer GS. The roles of government in improving health care quality and safety. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2004;30(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(04)30006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi AN, Zaslavsky AM, Schneider EC, Ayanian JZ. Trends in the quality of care and racial disparities in Medicare managed care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(7):692–700. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa051207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . 2006 national healthcare disparities report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2006. Publication No. 07-0012. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Senate Medicare Health Care Quality Demonstration Programs; 107th Congress; P.L.. 2005.pp. 108–173. [Google Scholar]

- Vaccarino V, Rathore SS, Wenger NK, Frederick PD, Abramson JL, Barron HV, Manhapra A, Mallik S, Krumholz HM. Sex and racial differences in the management of acute myocardial infarction, 1994 through 2002. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(7):671–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa032214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees BW, Walters AE, Prochaska M, Quinn MT. Reducing health disparities in depressive disorders process of care and outcomes between whites and ethnic minorities: Call for a comprehensive and pragmatic approach. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(5 Suppl):157S–194S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner RM, Asch DA, Polsky D. Racial profiling: The unintended consequences of coronary artery bypass graft report cards. Circulation. 2005;111:1257–63. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157729.59754.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West C, Walther L, editors. Race matters. Vintage; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Warren RC. The concept of race and health status in America. Public Health Reports. 1994;109(1):26–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]