Abstract

Background

Stigma and discrimination are widely recognized as factors that fuel the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Uganda's success in combating HIV/AIDS has been attributed to a number of factors, including political, religious and societal engagement and openness - actors that combat stigma and assist prevention efforts.

Objectives

Our study aimed to explore perceptions of Uganda-based key decision-makers about the past, present and optimal future roles of FBOs in HIV/AIDS work, including actions to promote or dissuade stigma and discrimination.

Methods

We analyzed FBO contributions in relation to priorities established in the Global Strategy Framework on HIV/AIDS, a consensus-based strategy developed by United Nations Member States. Thirty expert key informants from 11 different sectors including faith-based organizations participated in a structured interview on their perceptions of the role that FBOs have played and could most usefully play in HIV/AIDS prevention, care and support.

Results

Early on, FBOs were perceived by key informants to foster HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination. Respondents attributed this to inadequate knowledge, moralistic perspectives, and fear relating to the sensitive issues surrounding sexuality and death. More recent FBO efforts are perceived to dissuade HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination through increased openness about HIV status among both clergy and congregation members, and the leadership of persons living with HIV/AIDS.

Conclusions

Uganda's program continues to face challenges, including perceptions among the general population that HIV/AIDS is a cause for secrecy. By virtue of their networks and influence, respondents believe that FBOs are well-positioned to contribute to breaking the silence about HIV/AIDS which undermines prevention, care and treatment efforts.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Faith-Based Organizations, Religion, Stigma, Discrimination, Vulnerability, Uganda

Introduction

Stigma is a persistent influence on HIV/AIDS, inflicting substantial personal, social and economic costs on individuals, friends and families, communities and nations.1,2 Fueled by deeply-felt responses including fear of infection, moral outrage, and shame, those living with HIV/AIDS may be shunned, denied care and support, or avoid life-saving medical care out of fear of rejection.3 Moreover, HIV/AIDS-related stigma and resulting discriminatory acts create circumstances that fuel the spread of HIV.4 It has been observed that religious doctrines and moral positions by religious leadership have helped create and support perceptions that those infected have sinned and deserve their punishment, thus increasing the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS.5 Yet, religious leaders have also been lauded for using their influential voices to mitigate stigma and discrimination against those infected and affected by the virus that causes AIDS.6, 7

Uganda, an early epicenter of the disease, is now frequently cited as sub-Saharan Africa's HIV/AIDS “success story” in response to its dramatic reduction in HIV/AIDS prevalence.8 HIV prevalence among pregnant women in Kampala fell from 31% to 6.2% between 1990 and 2003,9 while among army recruits aged 18 to 21 years, prevalence rates decreased by 12% over 5 years.10 Among a number of theories about Uganda's success are high level of political commitment to openness about the epidemic, involvement of all segments of society, and the “ABC” strategy — Abstain, Be faithful or use Condoms.11,12

Regardless of strategy or vehicle responsible for Uganda's achievement, religious organizations are recognized for playing an important role in preventing new infections in Uganda. 6, 7 Uganda adopted a multi-sectoral approach in the fight against HIV/AIDS with an active participation among faith-based organizations as early as 1992.13 Nearly all of its major religious institutions, both Islamic and Christian, have been actively engaged in the country's struggle with HIV/AIDS.4,6 While there is general agreement supporting the critical role of the faith community in the dramatic reductions in Uganda's HIV prevalence, a better understanding of what faith communities are doing with regard to addressing the epidemic is critical.

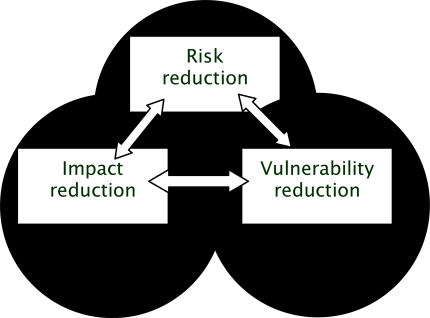

Our study aimed to explore perceptions of Uganda-based key decision-makers about the past, present and optimal future roles of FBOs in HIV/AIDS work, including actions to promote or dissuade stigma and discrimination. We analyzed FBO performance and contributions in relation to priorities established in the Global Strategy Framework on HIV/AIDS, an internationally-recognized, consensus-based strategy developed by United Nations Member States.14 This strategy encourages simultaneous efforts to reduce risk of HIV transmission, lessen vulnerability to HIV/AIDS, especially among women and other high risk groups, and mitigate the impact of the disease by providing care, treatment and support to those affected.

A key component of the overall strategy is to combat AIDS-related stigma that undermines the success of all three approaches. It is hoped that findings from this study will help FBOs to better understand how they are perceived, and how people in a variety of sectors think that FBOs can most usefully collaborate. Armed with this information, both faith and secular groups can capitalize on perceived strengths and address perceived weaknesses of FBOs to improve the collective response to reducing stigma and improving the lives of those living with the virus.

Methods

Key Informants

Interviewees were purposively sampled using the “snowball technique,”1 beginning with a list of potential informants identified from a background information search and references provided by other key actors in the field of HIV/AIDS. From a database of nearly 150 potential key informants representing 11 different sectors, 30 senior-level individuals actively engaged in HIV/AIDS programming, who play a leadership role in their institutions were carefully selected as key informants. Those surveyed included government officials, researchers, health service providers, national AIDS control program officers, representatives from non-governmental organizations (NGOs), pharmaceutical representatives, and leaders from major FBOs in the country.

Interview Framework and Procedures

By basing the interview questions on The Global Strategy Framework on HIV/AIDS, we sought to highlight and explore the “guiding principles and leadership commitments that together form the basis for a successful response to the epidemic,”14 as they relate to faith-based organizations.

We defined “faith-based organization” broadly to include the range from places of worship to development organizations with a mission of faith. This decision was taken for practical reasons in that the activities of the diverse faith-based actors in the country would be difficult to separate.

Semi-structured, face-to-face interviews were conducted from September to December 2003. Lasting on average 60 minutes, interviews examined key informants' perceptions of the extent of FBO leadership, collaboration and contribution to strategies to reduce risk, decrease vulnerability, and mitigate the impact of HIV/AIDS. Interviews were conducted in the preferred language of the interviewee and were audio taped after permission was obtained. Tapes were transcribed verbatim and translated, if necessary, into English. Permission to carry out the study was obtained from the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (NCST). Informed consent was obtained from all respondents.

Data Analysis

We aimed to reduce bias when analyzing transcripts by “blinding” ourselves to the identity of the informant through the assignment of a number to each informant. Using qualitative analysis software, Atlas.ti, we coded all electronic transcripts with predetermined categories that referred to the general topic(s) that informants discussed. We then divided transcripts into sub-groups according to the sector (‘FBO’ and ‘Non-FBO’). Data-derived codes based on themes emerging from data were identified from the typed text data.

For the purpose of this paper, we used a combination of codes to compile quotations that addressed the question, “What actions have FBO taken that promote or dissuade stigma and discrimination?” We studied our informants' responses in terms of FBO contributions, the conditions that define their participation, and the consequences of their involvement. Themes that resonated among a critical mass were further systematically analyzed for commonalities, variations and disagreements. Lastly, we contrasted and compared these themes across sectors to synthesize our findings. The analysis is limited to what our key informants perceive and does not aim to validate the objectivity of these perceptions.

Results

The findings are presented in two sections; the first relating to FBO actions perceived as promoting stigma, the second focusing on actions taken by FBOs to challenge stigmatizing behavior. Emerging themes for the former include the use of stigmatizing language and messages; deeply-entrenched societal attitudes and norms; and limited involvement of persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHAs). The latter section highlights themes focusing on the mitigation of stigma including increased knowledge; improved collaboration, inclusion and mobilization; and institutional capacity. All themes reflect an overarching consensus among both non-FBO and FBO respondents.

FBO actions facilitating stigma

Stigmatizing Language and Messages

There was agreement among key informants that the language historically used by FBO leadership had often supported and propagated discriminatory views towards PLWHAs within their religious community.

You know for a long time we have lived with stigma in this country. When people have HIV they are stigmatized, they are looked at as cursed. There was a time when even some religious leaders could say, ‘you have been cursed by God, you are a sinner, you have been misbehaving,’ which I think does not go well as far as people coming out [disclosing their HIV status] is concerned. (FBO Key Informant)

In the beginning it was rather not very kind because whoever was found HIV-positive was looked at as a sinner and I think faith-based organizations have played a big role in enhancing stigma which was unfortunately very bad. (Non-FBO Key Informant)

FBOs were also identified as sending out mixed messages in line with the Christian concept of ‘hate the sin, love the sinner.’ Respondents noted that while FBOs were largely unaware of the ill-effects of such language, these messages were as stigmatizing as more deliberate condemnation.

But when the church at the same place turns around and says, ‘You know my son, you know my daughter, I will be there for you. I know you have sinned but I will be there for you,’ again there is a mixed message there. (Non-FBO Key Informant)

Some religious leaders say things they don't realize that they are stigmatizing, for example that this disease is a punishment from God. Deuteronomy says, ‘If you obey, you will lead a healthy life, if you disobey, I curse you with boils, I will curse you with plagues, you will die an early death,’ you see. How do you expect a person living with HIV/AIDS to come out and say, ‘Here I am, I am positive’ after realizing that God is punishing him, singling him out of the many who are disobeying and don't have AIDS? (FBO Key Informant)

Deeply-Entrenched Attitudes and Norms

Informants cited the use of religious teachings to ascribe blame without regard to deeply entrenched societal vulnerabilities. According to respondents, many of the traditional religious solutions offered by FBOs did not address the significant HIV acquisition risks faced by vulnerable groups, including women.

Many women who get infected in Africa have never had sex with more than one man. They are faithful but infected. So to say, ‘be faithful therefore you don't get AIDS’ is not a very good message. So to say, ‘come to marriage’— you know that is the message sometimes the church leaders give. ‘If you want to escape AIDS please come to Jesus and get married in church and things will be fine,’ and you shake your head. How will Jesus save you from infection? Actually, getting married increases the risk. (FBO Key Informant)

Moralistic attitudes among various FBOs were also seen to foster both self-stigma among PLWHAs, as well as anger and withdrawal from religious activities.

What I have noticed in my church is that people who are HIV positive do not want to openly come out because of stigma. You know the church has that feeling that if you are a good Christian you should not get engaged in acts of sin…and to them, getting HIV, they take it that you got it through sin. And not only that, but even the person himself who is HIV-positive feels the self-stigma: ‘How will they see me that now I have got HIV? They will take it that I'm a sinner.’ (Non-FBO Key Informant)

The Reverend said that people with AIDS eat from dirty plates — we call them ‘mpombos’. I said to myself, ‘I have never eaten from the dirty plate. Get out of here! This is not a right place for you.’ I do not give them my money when I go there. (Non-FBO Key Informant)

FBOs were cited for equating positive behavior change to being a ‘good Christian’, sending erroneous signals to its members. Religious organizations were also noted for embracing select elements of behavior change, eschewing other more sensitive elements.

Up to now there are still problems of faith-based organizations accepting some of the elements of behavior change. I know many people tend to think that behaviour change is being Christian but it is far from that. I think behaviour change means changing from past ways of life into a new way of life. And they did not support that in the beginning. We were not really found forth-coming because of the negative approach our religious institutions had as far as HIV/AIDS is concerned. (Non-FBO Key Informant)

Limited Involvement of PLWHAs

According to most key informants, there has been limited involvement of PLWHAs in FBO activities. This lack of participation, often attributed to the fear of “breaking the silence,” was cited by respondents as further fostering stigma and discrimination within both the organization and greater community.

It has been realized that we are not doing enough in involving persons living with HIV/AIDS in our churches, mosques, temples and so forth. And even many of our religious leaders living with HIV are living with it very silently. It would be nice to…I mean, we wish to do a lot more to see to it that we involve them more and more, whether they are laypeople or they are ordained ministers. (FBO Key Informant)

Involvement of persons with HIV on the whole is inadequate because of the stigma. People are not very willing to come out, and if they come out there are still a lot of negative feelings. If a religious leader comes out, if he is positive, there is a lot of suspicion and so on. So, yes they have tried, but it is not yet adequate. Maybe it can be improved upon. (Non-FBO Key Informant)

FBO Actions Mitigating Stigma

Increased Knowledge

As the epidemic has evolved in Uganda, respondents noted the changing attitudes of FBOs towards those with HIV/AIDS. Informants applauded FBOs for accepting HIV/AIDS as a problem without “borders” and for sharing this message throughout their respective organizations.

Basically, FBOs are saying, ‘HIV/AIDS can get me but it can also get you.’ So when you have someone with HIV/AIDS in the community, you should support him, you should help him, because he may not be necessarily a sinner. (Non-FBO Key Informant)

Through participation in HIV/AIDS trainings, informants stated that FBOs have been armed with better information to fight discrimination and stigma within their institutions and congregations.

I should say where there has been training of the FBOs' leadership, where they have participated in seminars, they have had an impact on stigma and discrimination, because they have come to realize that there are many modes of HIV transmission and it is not just sex. And then they have come to know that even with HIV/AIDS you can still be productive. So to me, where they are trained they are effective in reducing stigma. (Non-FBO Key Informant)

“…the planners, both national and for us the implementers in designing a communication strategy that would be able to reach out many people, we opted for using FBOs or approaches, that is using religious leaders of all faiths…because these are the normal communicators in the community. Train them in HIV/AIDS issues including stigma and discrimination and ask them to pass the messages through sermons, group talks, home visits, and lectures and so on. So, we gave them more capacity to communicate on these issues. They have done it quite well, in fact very well in some instances. It is one thing establishing services and it is another connecting the services to the community, and that is where the faith-based groups did a good job…we are all satisfied with them. (Non-FBO Key Informant)

Improved Collaboration, Inclusion and Mobilization

FBOs were reported as increasingly involving PLWHAs in their activities as well as being supportive to those that declare their HIV status. FBOs were applauded for their more recent support of PLWHA networks. All key informants interviewed cited improved FBO networking and collaboration with community-based organizations founded or led by people living with HIV/AIDS.

Given the fact that we set up a unit like this purely for HIV-positive patients means that we are fighting stigma. We are saying, ‘you are welcome here, even if somebody else is not willing,’ and I am sure [this is] the whole aim of whatever other FBOs are doing. Setting up a program for these patients means they are helping them, they are recognizing that there is a problem and they are willing to help. (FBO Key Informant)

Seeing FBOs launch a network of religious people who are HIV-positive and those who are directly affected by HIV in the recently-held conference in Uganda made a difference. I am sure it is going to make a difference as long as the question of stigma within faith-based organization goes away; we are blessed in changing the course of HIV/AIDS. (Non-FBO Key Informant)

Most key informants were optimistic about these developments, particularly the involvement of religious persons who are positive.

… I mean a person like me — I am a religious leader. I am positive and my church and fellow church leaders have really supported me to do what I have been able to do. And I am aware of other religious leaders who have become open and they have not been harassed. Even other members of the church who have taken the courage to share are really supported and involved in message delivery, program development. (FBO Key Informant)

I know, for example, one faith group that involved one of their leaders who is HIV positive to do advocacy work. Sometimes they have used them to do advocacy to contribute to policy development. (Non-FBO Key Informant)

Key informants also acknowledged that community mobilization efforts of FBOs have led to increased uptake of prevention services such as voluntary counseling and testing. Through these efforts, as well as educational and outreach programs, FBOs were observed to contribute to reducing stigma and discrimination in the community.

FBOs have continued to educate people about the disease and the more you educate people the more you change their mind about the disease. So maybe that is where I can say they have been contributing to the reduction of stigma by educating people more about it, by telling people about it, by getting involved into the programs. By allowing persons with HIV/AIDS to go for care and support in the missionary hospitals, that is bringing down stigma. (Non-FBO Key Informant)

Well, the first thing really is to restore hope among these people, among the infected and the affected to help them rediscover their self-esteem, rebuild their self-confidence and promote positive living…(FBO Key Informant)

Institutional Capacity

FBOs were noted as possessing a comparative advantage in their ability to address stigma through their existing social mobilization channels. As trusted entities within the communities, FBOs were cited for their significant ability to influence the cultural norms of their congregations.

I think around the issues of stigma, FBOs have a huge role to play. So many people go to Church on Sundays here or Mosque on Fridays. It has always been a powerful tool for social mobilization and developing and sustaining or changing social norms. Always, more powerful probably than political systems because on one level it seems people, although they listen to politicians, they do not really trust them. (Non-FBO Key Informant)

FBOs were also cited as addressing HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination through their institutions that provide care and support to PLWHAs. FBOs' post-test clubs, homecare and income generating activities and support to orphans and widows were referenced as important programs in the fight against stigma and discrimination.

The primary focus is care, it is only care. We have several activities in care; we do medical and nursing care, we do home visiting then we do all types of counseling and we have some support for the orphans and preventive care also focusing on the youth. (FBO Key Informant)

I will pick out some few FBOs, which I know. For example, Nsambya Home Care has a department that is specifically dealing with HIV/AIDS. So what they are doing is one, they are looking at affected families, they are offering services to the orphans in terms of school fees and scholastic materials, In addition to that they offer voluntary counseling and testing services. But they do not end there. They go ahead to give support in relation to the needs of the persons living with HIV/AIDS, for example treatment that I think is free. And to me that is very important because we also have those who can't afford treatment. (Non-FBO Key Informant).

Discussion

HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination are multi-layered, building upon and reinforcing negative connotations through the association of HIV/AIDS with already marginalized behaviours.15 Our findings characterize FBOs as contributors to HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination at the early stages of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Uganda. Respondents attributed this to inadequate knowledge and misconceptions about HIV/AIDS transmission and fear relating to socially-sensitive issues including sexuality, disease and death. However, Uganda's FBOs have moved from being promoters of stigma to institutions at the forefront of dissuading HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination. Increased knowledge and understanding of HIV/AIDS among FBOs has aided this transition. Further, greater openness about one's HIV status among both clergy and congregation members, and the involvement of PLWHAs in prevention, care and advocacy efforts, characterize the changing attitudes and efforts among FBOs to stem HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination.

The findings reinforce the linkages between stigma and the reproduction of social differences. Parker and Aggleton15 note that stigma is deeply rooted, operating within values of everyday life. Stigma plays into and reinforces social inequalities, which have been both directly and indirectly promoted by the actions of some FBOs. Therefore, addressing the actions and attitudes of FBOs are considered important and viable options for many,16 including the respondents in this sample. The factors identified by participants in this study (e.g., language, lack of correct information, fear and harmful attitudes) that led FBOs to contribute to and be associated with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination are consistent with findings reported elsewhere.17, 18, 19 Yet, our study also suggests that the more recent actions of FBOs have promoted tolerance.

However, Uganda's fight against HIV/AIDS-related stigma has yet to be won. Roughly half of men and women surveyed by the Uganda Ministry of Health in 2005 said they would prefer to keep secret the fact that a family member had contracted HIV.9 Our findings support the notion that bringing FBO leadership to the fore in combating stigma, utilizing their extensive networks and opportunities to reach communities, would enable FBOs to play a greater role in ending the marginalization and secrecy that have contributed to the spread of HIV/AIDS around the world, and help further the successes that have been achieved in Uganda.

Figure 1.

The Global Strategy Framework on HIV/AIDS

Table 1.

Uganda key informant representation by sector

| Non-faith-Based Sectors | Number of informants |

| Businesses/Pharmaceutical Companies | 1 |

| Donors | 3 |

| Government Ministries | 2 |

| Health Care Facilities | 1 |

| HIV/AIDS Researchers | 4 |

| International Governmental Organizations | 1 |

| National AIDS Control Programs | 2 |

| Non-Governmental Organizations | 3 |

| Organizations Representing People Living with HIV/AIDS |

3 |

| Organizations Representing High | 2 |

| Risk/Vulnerable Groups | |

| Total Non-FBO Key Informants | 22 |

| Non-faith-Based Sectors |

Number of informants |

| Christian | 7 |

| Muslim | 1 |

| Total FBO key informants | 8 |

| Total key iInformants | 30 |

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to all those working in the field of HIV/AIDS especially the busy professionals who provided the interview and insights that made this study possible. Additionally we would like to thank Susan newcomer and Sara Friedman for their comments on the drafts. We are grateful to the research assistants for their support in during data collection. This study was supported by a Grant to the Global Health Council from the Catholic Medical Mission Board

Footnotes

A technique for finding research subjects in which an informant gives the researcher the name of another, who in turn provides the name of a third, and so on.

References

- 1.Herek GM, Mitnick L, Burris S, Chesney M, Devine P, Fullilove MT, et al. Workshop report: AIDS and stigma: a conceptual framework and research agenda. AIDS Public Policy. 1998;J 13(1):36–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keusch GT, Wilentz J, Kleinman A. Stigma and global health: developing a research agenda. Lancet. 2006;367(9509):525–527. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68183-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoneburner RL, Low-Beer D. Population-level HIV declines and behavioral risk avoidance in Uganda. Science. 2004;304(5671):714–718. doi: 10.1126/science.1093166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mann J. Statement at an informal briefing on AIDS to the 2nd session of the United Nations General Assembly. New York: United Nations; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS related stigma, discrimination and denial: Comparative Analysis: Research studies from Uganda and India. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh B. Conscience. Washington, DC: Catholics for a Free Choice; Breaking the Silence on HIV/AIDS: Religious health organizations and Reproductive Health, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall K, Keough L. Uganda: Conquering ‘Slim’ - Uganda's war on HIV AIDS. In: Marshall K, Keough L, editors. Mind, Heart and Soul in the Fight Against Poverty. Washington DC: World Bank; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green EC. Faith-Based Organizations: contribution to HIV prevention. Washington DC: The Synergy Project; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNAIDS, author. Progress Report. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2004. UNAIDS at Country level. [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNAIDS/WHO, author. AIDS epidemic update, December, 2005. Geneva: UNAIDS/WHO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.ICMH, author. Emerging patterns of HIV incidence In Uganda and other East African countries. Geneva: International Center for Migration and Health; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parkhurst JO, Lush L. The political environment of HIV: lessons from a comparison of Uganda and South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(9):1913–1924. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green EC. Case studies in ABC: Models for the implementation of abstinence and ‘faithfulness’ behavior change programs. Washington DC: USAID; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okware S, Kinsman J, Onyango S, Opio A, Kaggwa P. Revisiting the ABC strategy: HIV prevention in Uganda in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81(960):625–628. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.032425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNAIDS, author. The Global strategy framework on HIV/AIDS. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO, author. The 3x5 target newsletter. Geneva: 2004. Faith-based groups: Vital partners in the battle against AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bharat S, Aggleton P, Tyrer P. India: HIV/AIDS-related discrimination, stigma and denial. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blendon RJ, Donelan K. Discrimination against people with AIDS: the public's perspective. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(15):1022–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810133191522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilmore N, Somerville MA. Stigmatization, scapegoating and discrimination in sexually transmitted diseases: overcoming ‘them’ and ‘us’. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(9):1339–1358. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]