Abstract

Both major forms of diabetes involve a decline in β-cell mass, mediated by autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing cells in type 1 diabetes and by increased rates of apoptosis secondary to metabolic stress in type 2 diabetes. Methods for controlled expansion of β-cell mass are currently not available but would have great potential utility for treatment of these diseases. In the current study, we demonstrate that overexpression of trefoil factor 3 (TFF3) in rat pancreatic islets results in a 4- to 5-fold increase in [3H]thymidine incorporation, with full retention of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. This increase was almost exclusively due to stimulation of β-cell replication, as demonstrated by studies of bromodeoxyuridine incorporation and co-immunofluorescence analysis with anti-bromodeoxyuridine and antiinsulin or antiglucagon antibodies. The proliferative effect of TFF3 required the presence of serum or 0.5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor. The ability of TFF3 overexpression to stimulate proliferation of rat islets in serum was abolished by the addition of epidermal growth factor receptor antagonist AG1478. Furthermore, TFF3-induced increases in [3H]thymidine incorporation in rat islets cultured in serum was blocked by overexpression of a dominant-negative Akt protein or treatment with triciribine, an Akt inhibitor. Finally, overexpression of TFF3 also caused a doubling of [3H]thymidine incorporation in human islets. In summary, our findings reveal a novel TFF3-mediated pathway for stimulation of β-cell replication that could ultimately be exploited for expansion or preservation of islet β-cell mass.

TYPE 1 DIABETES MELLITUS results from the autoimmune destruction of insulin-containing pancreatic islet β-cells. Islet transplantation is being intensively investigated as an alternative to insulin injection therapy for treatment of type 1 diabetes in humans. Currently, one of the primary obstacles for broad-scale application of this cell-based therapy is the limited availability of pancreatic islets from cadaveric donors (1). Type 2 diabetes develops when β-cell mass fails to compensate for increased insulin demand imposed by development of peripheral insulin resistance. Thus, better understanding of pathways that regulate β-cell proliferation could be of great utility for development of therapies for both major forms of diabetes.

Trefoil factor 3 (TFF3) is a protease-resistant peptide containing seven cysteine residues, six of which form disulfide bonds to give the peptide a structure that resembles a clover (2). The seventh cysteine residue is required for homodimerization and is critical for TFF3 function (3,4,5). TFF3 is secreted from the goblet cells in the intestines and is thought to be involved in protection from injury and regenerative growth and repair of intestinal epithelial cells (6). The mechanism by which TFF3 exerts these actions is incompletely understood but seems to involve stimulation of transactivation of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (EGFR) (4).

TFF3 has been recently reported to be abundantly expressed in pancreatic islets (7), but its biological role in these cells is unknown. To gain further insight into this issue, we have developed molecular tools that allow us to suppress or overexpress TFF3 in rodent and human pancreatic islets. We find that TFF3 has potent mitogenic effects on pancreatic islet β-cells and that these effects require serum or EGF. Moreover, these effects of TFF3 occur with full retention of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS), a key β-cell function. These findings suggest that TFF3 regulates a pathway of β-cell replication that could be exploited for expansion or preservation of functional islet β-cell mass.

RESULTS

TFF3 Regulates Proliferation of INS-1-Derived 832/13 Cells

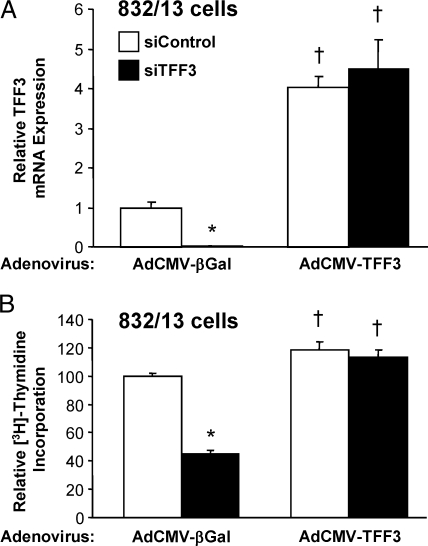

To begin to investigate the effects of TFF3 on β-cell proliferation, we selectively reduced the expression of TFF3 mRNA using a small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplex specific to rat TFF3 (siTFF3) in the rat INS-1-derived cell line 832/13. Transfection of 832/13 cells with siTFF3 reduced TFF3 mRNA levels by 92 ± 4% compared with cells transfected with a control siRNA with no known gene homology (siControl) (Fig. 1A) and resulted in a 57 ± 2% decrease in [3H]thymidine incorporation (Fig. 1B). Because suppression of TFF3 expression was able to decrease β-cell replication, we hypothesized that increasing TFF3 expression with a recombinant adenovirus containing the rat TFF3 cDNA (AdCMV-TFF3) would have the opposite effect. AdCMV-TFF3-treated 832/13 cells exhibited a 4.1 ± 0.3-fold increase in TFF3 mRNA (Fig. 1A) and a 19 ± 6% increase in [3H]thymidine incorporation (Fig. 1B) compared with cells treated with a control adenovirus expressing the β-galactosidase gene (AdCMV-βGal). Although the proliferative effect of TFF3 overexpression was predictably modest in the background of a transformed cell line, these data also show that the reduction in both TFF3 mRNA and [3H]thymidine incorporation in siTFF3-treated cells could be reversed by adenovirus-mediated restoration of TFF3 expression, proving that the inhibition of cell growth in cells transfected with the siTFF3 duplex was a direct result of suppression of the TFF3 gene and not an off-target effect. Also consistent with this interpretation, measurement of media adenylate kinase activity in untreated, siTFF3-treated, or siControl-treated 832/13 cells revealed no increase in enzyme release in response to treatment with either siRNA duplex, indicating that the fall in [3H]thymidine incorporation in siTFF3-treated cells shown in Fig. 1B was not an artifact of cell toxicity (data not shown).

Figure 1.

TFF3 Regulates Proliferation of the 832/13 β-Cell Line

The 832/13 cells were transfected with siRNA duplexes directed against TFF3 (siTFF3) or with no known sequence homology (siControl) and then transduced 24 h later with a control adenovirus expressing β-galactosidase (AdCMV-βGal) or a recombinant adenovirus expressing TFF3 (AdCMV-TFF3). A, TFF3 mRNA levels measured by RT-PCR; B, to determine whether TFF3 regulates β-cell proliferation, [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured. Measurements of mRNA and [3H]thymidine incorporation were made 48 h after viral transduction. Data are means ± sem for four independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 vs. siControl; †, P < 0.05 vs. AdCMV-βGal.

TFF3 Stimulates Proliferation of Rat Pancreatic Islets with No Impairment of β-Cell Function

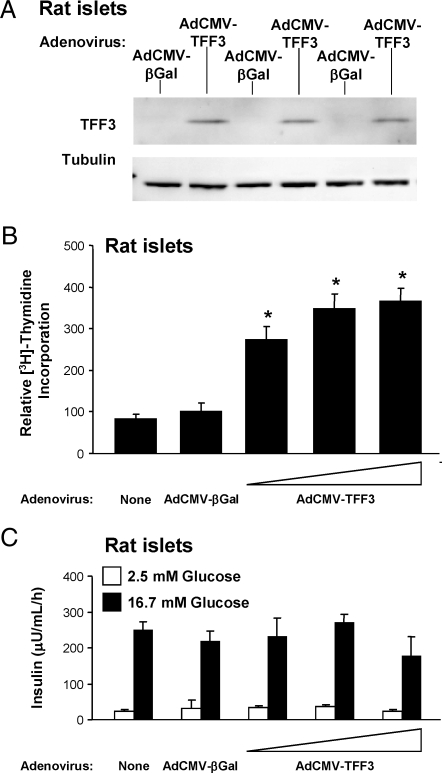

To determine whether the effects of TFF3 on proliferation of INS-1-derived cell lines translated to primary cells, we treated rat pancreatic islets with AdCMV-TFF3. TFF3 mRNA and protein are present in 832/13 cells but are essentially undetectable in primary adult rat islets. Treatment of islets with AdCMV-TFF3 resulted in a clear virus dose-dependent increase in TFF3 mRNA (data not shown) and protein (Fig. 2A) levels. The level of TFF3 overexpression shown in the immunoblot in Fig. 2A resulted in an approximate 4-fold increase in [3H]thymidine incorporation in primary islets (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

TFF3 Increases Islet Cell Proliferation without Compromising β-Cell Function

Rat islets were harvested and transduced with a control adenovirus (AdCMV-βGal) or increasing doses of a recombinant adenovirus expressing TFF3 (AdCMV-TFF3). A, Immunoblot with an antibody specific for TFF3 demonstrating overexpression of TFF3 in rat islets by transducing with the middle dose of AdCMV-TFF3. Tubulin serves as an internal control. B, [3H]Thymidine incorporation. C, β-Cell function was assayed by measuring insulin secretion at basal (2.5 mm) and stimulatory (16.7 mm) glucose, respectively. All assays were conducted 72 h after viral treatment of islets. *, P < 0.05 vs. AdCMV-βGal.

A general observation in the islet research field is that stimulation of islet proliferation with oncogenes or growth factors often results in loss of key β-cell functions such as GSIS (1). Importantly, adenovirus-mediated overexpression of TFF3 did not compromise β-cell function (Fig. 2C), as evidenced by comparable insulin secretion at basal and stimulatory glucose (2.5 and 16.7 mm, respectively) in AdCMV-βGal- and AdCMV-TFF3-treated islets. Thus, TFF3 appears to be capable of increasing islet cell replication with no decrement in β-cell function, at least in the time frame of these studies (3–4 d of TFF3 expression).

TFF3-Stimulated Islet Proliferation Involves β-Cells

To determine whether the TFF3-mediated increase in islet cell proliferation involves β-cells, primary rat islets were treated with adenoviruses as before and the incorporation of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) was measured by immunofluorescence microscopy, in slides cotreated with antibodies specific to insulin or glucagon. Figure 3A shows representative islet sections from a total of 84 AdCMV-TFF3-treated islets and 53 AdCMV-βGal-treated islets (representing 10,348 cells and 5,089 cells counted, respectively). Approximately 1% of islet cells treated with AdCMV-βGal were BrdU positive (Fig. 3B), and 0.8% were positive for both insulin and BrdU (Fig. 3C). In contrast, 5% of islet cells were BrdU positive in AdCMV-TFF3-treated islets, and 4.7% of islet cells were both BrdU and insulin positive in this group (e.g. >90% of BrdU-positive cells were also insulin positive). Based on previous studies, we expect an efficiency of adenovirus-mediated islet cell transduction of 70%, including β-cells at the islet core (8,9). Overall, the approximate 5-fold increase in BrdU incorporation in response to TFF3 expression is well aligned with our measurements of [3H]thymidine incorporation in islet cells (Fig. 2B) and indicate that the increase in BrdU incorporation in whole islets occurs almost exclusively in insulin-expressing β-cells.

Figure 3.

Most TFF3-Mediated Stimulation of Islet Cell Replication Occurs in β-Cells

A, To determine the extent to which TFF-3-mediated increases in islet cell replication occur in β-cells, rat islets were harvested and transduced with a control adenovirus (AdCMV-βGal) or a recombinant adenovirus expressing TFF3 (AdCMV-TFF3). After 48 h of culture, BrdU was added to the culture media for an additional 24 h. Islets were sectioned, and immunofluorescence was performed with antibodies specific for BrdU, insulin, and glucagon. B, The total number of BrdU-positive cells in AdCMV-TFF3 vs. AdCMV-βGAL-treated rat islets. C, The number of BrdU and insulin co-positive cells in AdCMV-TFF3 and AdCMV-βGAL-treated rats islets. In B and C, numbers are expressed as a percentage of the total number of islet cells. *, P < 0.05 vs. AdCMV-βGal. DAPI, 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole.

TFF3-Stimulated Islet Proliferation Is Dependent on Akt

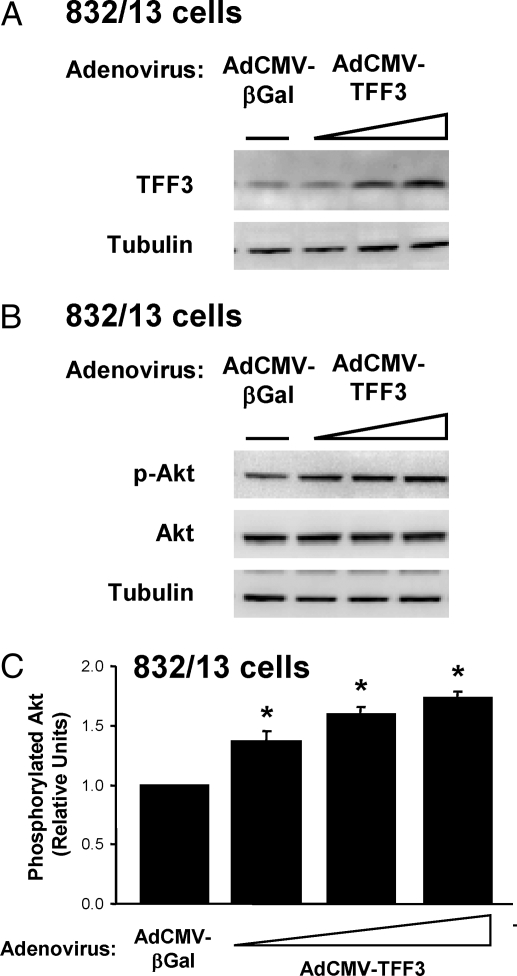

Because it has previously been shown that protein kinase B/Akt can regulate islet proliferation (10,11,12), we sought to determine whether the effects of TFF3 on β-cell proliferation were mediated by this pathway. Treatment of 832/13 cells with increasing doses of AdCMV-TFF3 caused dose-dependent increases in TFF3 protein levels (Fig. 4A), with an approximate peak increase of 3-fold, consistent with the estimate of a four-fold increase in TFF3 mRNA in AdCMV-TFF3-treated cells shown in Fig. 1A. As TFF3 protein content increased, the amount of phosphorylated Ser473 (active) Akt was also increased (1.7 ± 0.1-fold in three-independent experiments), with no changes in total Akt protein (Fig. 4, B and C). Thus, overexpression of TFF3 causes Akt activation in 832/13 cells.

Figure 4.

TFF3 Overexpression Increases Akt Phosphorylation

The 832/13 cells were transduced with a control adenovirus (AdCMV-βGal) or increasing doses of a recombinant adenovirus expressing TFF3 (AdCMV-TFF3). After 72 h, cells were harvested for immunoblot analysis. A, Immunoblot with an antibody specific for TFF3. B, Immunoblot with an antibody specific for phosphorylated and total Akt. Tubulin serves as an internal control. Shown is a representative immunoblot from among three independent experiments. C, Quantitative analysis of phosphorylated Akt. Data are normalized to total Akt and tubulin and are expressed as means ± sem for three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 vs. AdCMV-βGal.

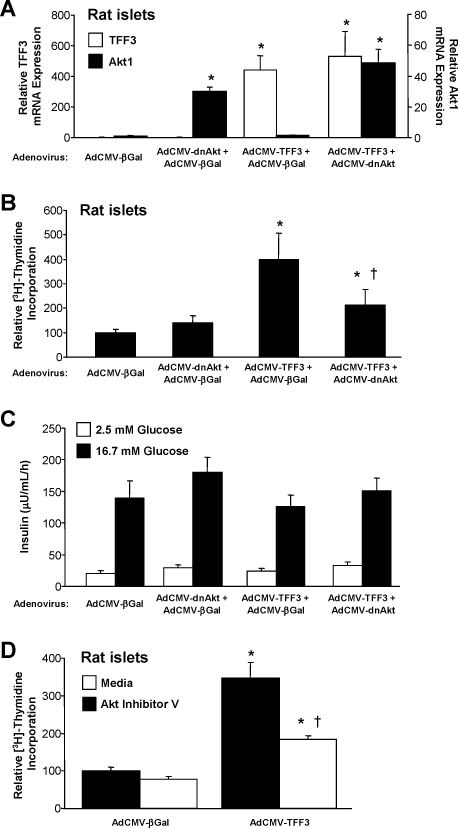

Next we sought to disrupt TFF3-mediated increases in proliferation by impairment of Akt signaling with an adenovirus expressing a dominant-negative form of Akt (AdCMV-dnAkt). Treatment of rat islets with AdCMV-TFF3 or AdCMV-dnAkt caused corresponding increases in mRNA levels for each gene (Fig. 5A). The increase in [3H]thymidine incorporation observed in islets treated with AdCMV-TFF3- relative to AdCMV-βGal-treated islets was largely attenuated in islets with coexpression of TFF3 and the dominant-negative Akt protein (Fig. 5B). These data indicate that the effect of TFF3 on islet proliferation can largely be blocked by impairment of Akt activation. We also measured GSIS in islets treated with AdCMV-βGal, AdCMV-dnAkt, and/or AdCMV-TFF3 (Fig. 5C). Importantly, none of the viral treatments, either alone or in various combinations, had any effect on insulin secretion at basal or stimulatory glucose concentrations.

Figure 5.

TFF3-Stimulated Islet Proliferation Is Mediated by Akt

To determine whether TFF3 mediates its effects on proliferation through Akt, an adenovirus expressing a dominant-negative Akt (AdCMV-dnAkt) was employed to disrupt Akt signaling. Primary rat islets were harvested and transduced with AdCMV-βGal, AdCMV-dnAkt plus AdCMV-βGal, AdCMV-TFF3 plus AdCMV-βGal, or AdCMV-TFF3 plus AdCMV-dnAkt. Studies were conducted 72 h after viral treatment. A, TFF3 and Akt mRNA levels; B, [3H]thymidine incorporation; C, GSIS. In A–C, data are means ± sem for five independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 vs. AdCMV-βGal; †, P < 0.05 vs. AdCMV-TFF3 plus AdCMV-βGal. D, Primary rat islets were treated with AdCMV-βGal or AdCMV-TFF3. After 48 h, islets were transferred to medium alone or that containing 10 μm Akt inhibitor V. [3H]Thymidine incorporation was measured after 24 h of incubation in the presence or absence of the inhibitor. Data are means ± sem for three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 vs. AdCMV-βGal; †, P < 0.05 vs. media control.

To further examine the role of Akt in TFF3-mediated stimulation of islet cell proliferation, we treated islets with a pharmacological inhibitor of Akt (Akt inhibitor V/triciribine). Similar to experiments with the dominant-negative Akt construct, treatment with the pharmacological inhibitor caused a clear decrease in [3H]thymidine incorporation in AdCMV-TFF3-treated islets (Fig. 5D).

EGFR Signaling Is Required for TFF3-Stimulated Islet Proliferation

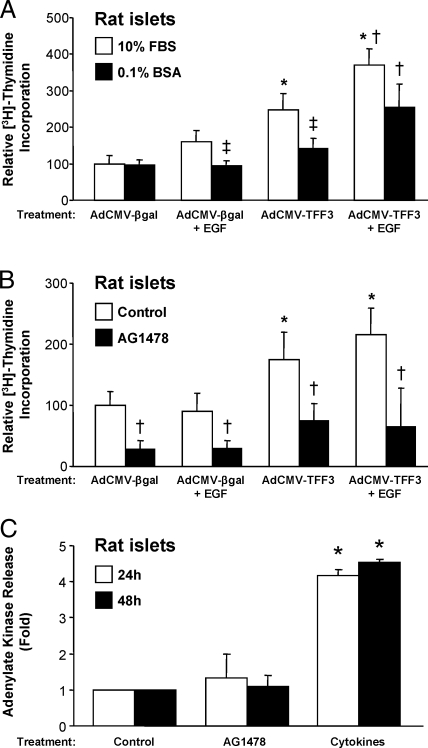

We hypothesized that TFF3 acts in concert with another factor to mediate its proliferative effects. Consistent with this idea, AdCMV-TFF3 treatment increased [3H]thymidine incorporation only in islets cultured in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), but not in 0.1% BSA (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

EGFR Signaling Is Required for TFF3-Stimulated Islet Proliferation

A, Rat islets were treated with AdCMV-βGal or AdCMV-TFF3. After 24 h, islets were transferred to media containing 10% FBS or 0.1% BSA in the presence or absence of 0.5 ng/ml EGF for 24 h. [3H]Thymidine incorporation was measured during the final 24 h. Data are means ± sem for three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 vs. AdCMV-βGal; †, P < 0.05 vs. AdCMV-TFF3; ‡, P < 0.05 vs. 10% FBS. B, Islets were treated with AdCMV-βGal or AdCMV-TFF3. After 24 h, islets were transferred to media containing 0.1% BSA for 48 h. After an additional 24 h in culture, islets were incubated with or without 0.5 ng/ml EGF and with or without 10 μm AG1478 for 24 h. [3H]Thymidine incorporation was measured during the final 24 h. Data are means ± sem for three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 vs. AdCMV-βGal; †, P < 0.05 vs. control. C, To demonstrate that acute EGFR inhibition does not induce cytotoxicity in cultured rat islets, primary rat islets were isolated and treated with vehicle (control), 10 μm AG1478, or 10 ng/ml IL-1β and 100 U/ml IFN-γ (cytokines). Cell death was assayed by the presence of adenylate kinase in the culture media, an indicator of cell lysis. Data are normalized to cells exposed to control and represent mean ± sem for three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 vs. control.

Because TFF3 has been shown to transactivate the EGFR (4), we hypothesized that EGF may be the serum factor required for TFF3-mediated islet proliferation. To test this idea, we exposed islets to AdCMV-βgal or AdCMV-TFF3, with and without EGF, and in the presence or absence of 10% FBS. These studies demonstrate that the failure of AdCMV-TFF3 to stimulate [3H]thymidine incorporation into islets in the absence of 10% FBS could be corrected by the addition of EGF (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, in either the presence or absence of serum, the combination of EGF plus AdCMV-TFF3 treatment had a larger stimulatory effect on [3H]thymidine uptake than either treatment alone, suggesting that the combination of TFF3 and EGF might serve as a particularly efficacious approach for increasing islet proliferation.

To further explore the role of EGFR signaling in TFF3-stimulated proliferation, we inhibited EGFR with the pharmacological agent AG1478 in rat islets cultured in the presence of 10% FBS (Fig. 6B). AG1478 was able to completely abrogate AdCMV-TFF3-induced increases in [3H]thymidine incorporation in these cells, providing further evidence for a critical role for EGFR activation in TFF3-mediated β-cell proliferation.

To eliminate the possibility that the effects of AG1478 were related to cellular toxicity, we measured release of adenylate kinase into the culture medium in cells with and without exposure to 10 μm AG1478 for 24 or 48 h (the concentration of AG1478 is the same as used to demonstrate impairment of TFF3-mediated proliferation in Fig. 6B). Adenylate kinase release is a general measure of cytotoxicity that should increase in cells undergoing either necrotic or apoptotic cell death (13). As a positive control for cell death, we treated cells with a cytotoxic cytokine mixture (IL-1β and IFN-γ). As can be seen in Fig. 6C, AG1478 does not affect cell viability at either time point, whereas exposure of islets to the cytokine mixture causes a 5-fold increase in adenylate kinase release/cell death.

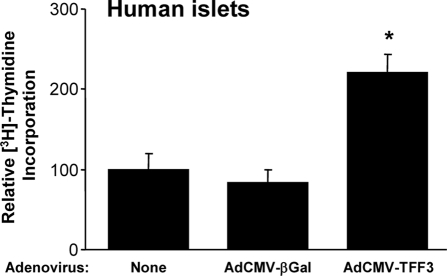

Effect of TFF3 Overexpression on Cell Replication in Human Islets

To investigate whether the proliferative effects of TFF3 that we have described in rodent cell lines and pancreatic islets translate to human cells, we treated human islets with AdCMV-TFF3 or AdCMV-βGal and measured [3H]thymidine incorporation. We found that TFF3 overexpression more than doubled [3H]thymidine incorporation in three separate human islet preparations (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

TFF3 Increases Human Islet Proliferation

Human islets were harvested and transduced with no virus (none), a control adenovirus (AdCMV-βGal), or a recombinant adenovirus expressing TFF3 (AdCMV-TFF3). [3H]Thymidine incorporation was measured 72 h after viral treatment. Data are means ± sem for three independent human islet aliquots. *, P < 0.05 vs. none and AdCMV-βGal.

DISCUSSION

Both major forms of diabetes are ultimately caused by a failure of the pancreatic β-cells to deliver insulin at a rate sufficient to account for metabolic demand. In the case of type 1 diabetes, insulin deficiency occurs due to autoimmune destruction of islet β-cells, whereas in type 2 diabetes, β-cell mass fails to compensate for obesity and insulin resistance. In light of this, a major practical goal of modern diabetes research is to develop methods for controlled β-cell expansion that could be applicable to therapies for both major forms of the disease. Two kinds of approaches have been considered. 1) One approach is the production of large pools of human islets ex vivo that can be transplanted into diabetic subjects. For this approach to flourish, strategies must be developed for coaxing stem cells to differentiate into fully functional β-cells or for stimulating replication of adult human islets with full retention of key functions such as fuel-regulated insulin secretion. 2) Another approach is the stimulation of expansion of islet cell mass within the pancreas in situ. This could involve synthesis of new islet cells (neogenesis) from precursor cells and/or stimulation of replication of preexisting β-cells.

Recently, Nielsen and co-workers (7) showed convincingly that TFF3 is expressed in human and rat pancreatic islet β-cells. Interestingly, the same authors found that addition of recombinant TFF3 peptide to neonatal rat islets stimulated their attachment and migration but not their proliferation. These studies differ from those reported here in the following ways: 1) neonatal rat islets were used in the studies of Nielsen and co-workers rather than adult rat or human islets in the current study; 2) Nielsen and co-workers cultured their islets in RPMI 1640 containing 0.5% human serum and 500 ng/ml human GH, whereas we show in the current study that such low levels of serum preclude demonstration of the proliferative effects of TFF3 unless EGF is added; 3) [3H]thymidine incorporation assays were conducted after a 24-h starvation period in 0.5% human serum in the Nielsen study, whereas no starvation period was employed in the current work; and 4) TFF3 was administered as an exogenous peptide in the Nielsen study, whereas our study relied on expression of the TFF3 cDNA within islet cells. Based on these differences in experimental design, possible explanations for the lack of effect of TFF3 on replication in the former study and the clear effect in the current work include the following: 1) at the low serum levels used in the former study, EGFR signaling may have been below a critical threshold required for TFF3 proliferative signaling (see Fig. 6 of the current study); 2) a difference related to the use of neonatal rather than adult islets; or 3) a difference related to intracellular expression of TFF3 compared with its extracellular administration. Additional studies will be required to distinguish among these possibilities.

Our study does provide important clues as to the mechanism by which overexpressed TFF3 might stimulate islet cell replication. Previous studies have suggested that trefoil factors, including TFF3, may act via effects on EGFR signaling (4,14). For example, exposure of HT-29 colonic epithelial cells to TFF3 induces the phosphorylation of EGFR (4). In addition, TFF3 expression is able to prevent etoposide-induced apoptosis in the AGS gastric cancer cell line, and this effect can be blocked by coexpression of a dominant-negative EGFR lacking the kinase domain (14).

EGFR signaling is complex, involving activation of multiple signaling pathways, including the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway, the Erk/MAPK pathway, the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway, and the inositol trisphosphate/protein kinase pathway. Based on studies reported here showing that the proliferative effects of TFF3 in islet cells can be blocked by both molecular and pharmacological suppression of Akt activity, the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt pathway emerges as one of particular relevance. Indeed, overexpression of Akt in islets of transgenic mice has been shown previously to increase β-cell mass (10,11).

What remains unclear is whether TFF3 is itself a bona fide ligand for the EGFR or whether TFF3 merely facilitates or potentiates the interaction of EGF with its receptor. Furthermore, if TFF3 is able to increase the stability of the EGF/EGFR complex, it is possible that it might also perform this function with other ligand/receptor tyrosine kinase complexes. The data presented here showing that EGFR function is required for TFF3 signaling in islets are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that a cadre of EGF family members (including EGF, TGF-α, epiregulin, and betacellulin) can induce β-cell proliferation (15,16,17,18). Similarly, a recent study has demonstrated that knockout of the EGFR results in impaired postnatal β-cell proliferation (19), further supporting the importance of EGFR signaling in control of β-cell mass. Combined with the results of the current study, the exciting possibility that emerges is that in the presence of normal circulating levels of EGF or other EGFR ligands, up-regulation of TFF3 expression may function as a switch for β-cell replication by enhancing EGFR signaling in response to physiological demand, for example in pregnancy or obesity. This idea is currently being investigated in our laboratory.

In summary, we have demonstrated that TFF3 overexpression increases islet β-cell proliferation. Importantly, the TFF3-mediated increases in islet proliferation are specific to β-cells and do not alter β-cell function and can also be demonstrated in human islets. In addition, we provide strong evidence linking TFF3-stimulated β-cell proliferation to the Akt and EGFR signaling pathways. Based on these findings, we conclude that TFF3 might serve as a useful factor to expand β-cell mass in vitro and potentially in vivo. Because EGF has the ability to potentiate the effects of TFF3 (and vice versa), combined EGF and TFF3 treatment may be the optimally effective strategy for expanding β-cell mass.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Use of Recombinant Adenoviruses

INS-1-derived 832/13 rat insulinoma cells were cultured as described previously (20). Pancreatic islets were harvested from male Sprague Dawley rats weighing approximately 250 g (21,22), under a protocol approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

For siRNA-directed suppression of TFF3 expression, pre-annealed duplexes (5′-CCGTGGTTGCTGTTTTGAC-3′ and 5′-GTCAAAACAGCAACCACGG-3′) were obtained from Ambion (Austin, TX; no. 197602) and transfected into 832/13 cells via the Amaxa nucleofection system (Amaxa Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) using 2 μg duplex per 2 × 106 cells in T-solution as previously described (13). As a control, cells were also transfected with a siRNA duplex with no known sequence homology (siControl), as previously described (23). For gene overexpression studies, recombinant adenoviruses containing the rat TFF3 cDNA (AdCMV-TFF3) or the bacterial β-galactosidase gene (AdCMV-βGAL) were prepared and used as previously described (24,25,26). To disrupt Akt signaling, we used a recombinant adenovirus containing a mutated form of Akt (AdCMV-dnAkt), in which T308 and S473 are mutated to alanine residues to prevent phosphorylation and activation of this kinase; this form of Akt exerts a dominant-negative function on Akt signaling (27). The 832/13 cells and primary rat islets were treated with viruses for 24 h and then cultured in virus-free media for an additional 48 h after treatment before functional studies.

[3H]Thymidine Incorporation

DNA synthesis rates were measured by measurement of incorporation of [3H]methyl thymidine into genomic DNA as described (8). [3H]Methyl thymidine was added at a final concentration of 1 μCi/ml to 832/13 cells in 12-well plates during the last 4 h of cell culture or to pools of about 200 islets during the last 18 h of cell culture. The 832/13 cells were washed three times with cold medium. DNA was precipitated with two 500-μl aliquots of cold 10% trichloroacetic acid and solubilized by addition of 250 μl 0.3 n NaOH. Groups of 25 islets were picked in triplicate, washed, and centrifuged twice at 300 × g for 3 min at 4 C. DNA was precipitated with 500 μl cold 10% trichloroacetic acid and solubilized by addition of 80 μl 0.3 n NaOH. The amount of [3H]thymidine incorporated into DNA was measured by liquid scintillation counting and normalized to total cellular protein.

BrdU Labeling and Immunofluorescence in Rat Islets

DNA synthesis was also evaluated by measurement of BrdU incorporation into cellular DNA. For these studies, a 1:100 dilution of BrdU labeling reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added to islet culture media in place of [3H]thymidine for the final 18 h of cell culture. Preparation of islets for immunohistochemistry was as described (28). Islets were fixed in Bouin's solution for 2 h and maintained in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. The 5-μm serial sections on glass slides were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated in a graded series of ethanol solutions. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwaving the slides for 13.5 min in 10 mm sodium citrate buffer with 0.05% Tween 20 (pH 6.0). Indirect immunofluorescence was performed using the following primary antibodies and dilutions: mouse anti-BrdU (1:100; Invitrogen), guinea pig antiinsulin (1:50; Invitrogen), and rabbit antiglucagon (1:50; Invitrogen). Slides were incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000; Invitrogen) and were washed in PBS three times for 5 min each between antibody applications.

Immunoblot Analysis

Whole-cell lysates were prepared using M-PER lysis buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL) supplemented with protease (Pierce) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). In addition, islet samples were briefly sonicated. The 20-μg aliquots of protein were resolved on 4–12% or 10% Bis-Tris-HCl buffered polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked for 20 min with 1× milk buffer (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Primary antibodies were diluted in polyvinylpyrrolidone (29) as follows: anti-TFF3 (1:250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or anti-total or -phosphorylated-Akt (1:1000; Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA). Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 C, and primary antibodies were detected using appropriate horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies and visualized using ECL Advance (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ) on a Versadoc 5000 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Membranes were stripped (ReBlot; Chemicon) and reprobed with anti-γ-tubulin (1:10,000; Sigma).

GSIS

Pools of about 200 rat islets were treated with various recombinant adenoviruses, and groups of 25 islets per condition were picked in triplicate. Static incubation GSIS assays were performed as described (25). Media samples were analyzed by RIA with the insulin Coat-a-Count kit (Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA) (30,31).

Measurement of RNA Levels

RNA was harvested from 832/13 cells or 20–50 primary rat islets using the RNeasy mini or micro kits (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), respectively. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with 0.5 μg RNA using iScript (Bio-Rad) reagents. Real-time PCR were performed using the ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detection system and software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and PCR MasterMix reagents (Bio-Rad) as previously described (25). Sequences for all primers are available upon request from the authors.

Ligand and Inhibitor Experiments

Inhibition of Akt signaling by pharmacological agents was achieved by exposing islets to 10 μm Akt inhibitor V/triciribine (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) for 24 h. To stimulate EGFR signaling, 0.5 μg/ml EGF from mouse submaxillary glands (Sigma) was added for 24 or 48 h as indicated. To inhibit EGFR signaling, 10 μm AG1478 (Calbiochem) was added for 24 h. To demonstrate that acute EGFR inhibition does not induce cytotoxicity in cultured rat islets, primary rat islets were isolated and treated with vehicle (control), 10 μm AG1478, or 10 ng/ml IL-1β and 100 U/ml IFN-γ (cytokines). Cell death was assayed as before (13) by the presence of adenylate kinase in the culture media, an indicator of cell lysis.

Human Islet Experiments

Human islet aliquots were procured at the University of Virginia. Islet preparations were cultured, treated with recombinant adenoviruses, and used for measurements of [3H]thymidine incorporation exactly as described for rat islet cultures.

Statistical Methods

ANOVA analysis was applied to detect statistical differences (P < 0.05). Differences within ANOVA were determined using Tukey's post hoc tests. All data are reported as means ± sem.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ken Walsh (Boston University) for the dnAkt adenovirus and Helena Winfield for expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants U01 DK56047 (C.B.N.), and K99 DK078732 (P.T.F.) and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Grants 17-2007-1026 (C.B.N.) and 3-2005-954 (P.T.F.).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online February 7, 2008

Abbreviations: BrdU, 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, EGF receptor; FBS, fetal bovine serum; GSIS, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion; TFF3, trefoil factor 3.

References

- Hohmeier HE, Newgard CB 2005 Islets for all? Nat Biotechnol 23:1231–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thim L, May FE 2005 Structure of mammalian trefoil factors and functional insights. Cell Mol Life Sci 62:2956–2973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick MP, Westley BR, May FE 1997 Homodimerization and hetero-oligomerization of the single-domain trefoil protein pNR-2/pS2 through cysteine 58. Biochem J 327(Pt 1):117–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita K, Taupin DR, Itoh H, Podolsky DK 2000 Distinct pathways of cell migration and antiapoptotic response to epithelial injury: structure-function analysis of human intestinal trefoil factor. Mol Cell Biol 20:4680–4690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muskett FW, May FE, Westley BR, Feeney J 2003 Solution structure of the disulfide-linked dimer of human intestinal trefoil factor (TFF3): the intermolecular orientation and interactions are markedly different from those of other dimeric trefoil proteins. Biochemistry 42:15139–15147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann W 2005 Trefoil factors TFF (trefoil factor family) peptide-triggered signals promoting mucosal restitution. Cell Mol Life Sci 62:2932–2938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackerott M, Lee YC, Mollgard K, Kofod H, Jensen J, Rohleder S, Neubauer N, Gaarn LW, Lykke J, Dodge R, Dalgaard LT, Sostrup B, Jensen DB, Thim L, Nexo E, Thams P, Cathrine Bisgaard H, Nielsen JH 2006 Trefoil factors are expressed in human and rat endocrine pancreas: differential regulation by growth hormone. Endocrinology 147:5752–5759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker TC, BeltrandelRio H, Noel RJ, Johnson JH, Newgard CB 1994 Overexpression of hexokinase I in isolated islets of Langerhans via recombinant adenovirus. Enhancement of glucose metabolism and insulin secretion at basal but not stimulatory glucose levels. J Biol Chem 269:21234–21238 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker TC, Noel RJ, Johnson JH, Lynch RM, Hirose H, Tokuyama Y, Bell GI, Newgard CB 1996 Differential effects of overexpressed glucokinase and hexokinase I in isolated islets. Evidence for functional segregation of the high and low Km enzymes. J Biol Chem 271:390–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal-Mizrachi E, Wen W, Stahlhut S, Welling CM, Permutt MA 2001 Islet beta cell expression of constitutively active Akt1/PKBα induces striking hypertrophy, hyperplasia, and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Invest 108:1631–1638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle RL, Gill NS, Pugh W, Lee JP, Koeberlein B, Furth EE, Polonsky KS, Naji A, Birnbaum MJ 2001 Regulation of pancreatic β-cell growth and survival by the serine/threonine protein kinase Akt1/PKBα. Nat Med 7:1133–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Li L, Xu E, Wong V, Rhodes C, Brubaker PL 2004 Glucagon-like peptide-1 regulates proliferation and apoptosis via activation of protein kinase B in pancreatic INS-1 β-cells. Diabetologia 47:478–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier JJ, Fueger PT, Hohmeier HE, Newgard CB 2006 Pro- and antiapoptotic proteins regulate apoptosis but do not protect against cytokine-mediated cytotoxicity in rat islets and β-cell lines. Diabetes 55:1398–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taupin DR, Kinoshita K, Podolsky DK 2000 Intestinal trefoil factor confers colonic epithelial resistance to apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:799–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Miyagawa J, Waguri M, Sasada R, Igarashi K, Li M, Nammo T, Moriwaki M, Imagawa A, Yamagata K, Nakajima H, Namba M, Tochino Y, Hanafusa T, Matsuzawa Y 2000 Recombinant human betacellulin promotes the neogenesis of β-cells and ameliorates glucose intolerance in mice with diabetes induced by selective alloxan perfusion. Diabetes 49:2021–2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huotari MA, Palgi J, Otonkoski T 1998 Growth factor-mediated proliferation and differentiation of insulin-producing INS-1 and RINm5F cells: identification of betacellulin as a novel β-cell mitogen. Endocrinology 139:1494–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntz E, Broca C, Komurasaki T, Kaltenbacher MC, Gross R, Pinget M, Damge C 2005 Effect of epiregulin on pancreatic β-cell growth and insulin secretion. Growth Factors 23:285–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooman I, Bouwens L 2004 Combined gastrin and epidermal growth factor treatment induces islet regeneration and restores normoglycaemia in C57Bl6/J mice treated with alloxan. Diabetologia 47:259–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen PJ, Ustinov J, Ormio P, Gao R, Palgi J, Hakonen E, Juntti-Berggren L, Berggren PO, Otonkoski T 2006 Downregulation of EGF receptor signaling in pancreatic islets causes diabetes due to impaired postnatal β-cell growth. Diabetes 55:3299–3308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmeier HE, Mulder H, Chen G, Henkel-Rieger R, Prentki M, Newgard CB 2000 Isolation of INS-1-derived cell lines with robust ATP-sensitive K+ channel-dependent and -independent glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 49:424–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milburn Jr JL, Hirose H, Lee YH, Nagasawa Y, Ogawa A, Ohneda M, BeltrandelRio H, Newgard CB, Johnson JH, Unger RH 1995 Pancreatic β-cells in obesity. Evidence for induction of functional, morphologic, and metabolic abnormalities by increased long chain fatty acids. J Biol Chem 270:1295–1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naber SP, McDonald JM, Jarett L, McDaniel ML, Ludvigsen CW, Lacy PE 1980 Preliminary characterization of calcium binding in islet-cell plasma membranes. Diabetologia 19:439–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MV, Joseph JW, Ilkayeva O, Burgess S, Lu D, Ronnebaum SM, Odegaard M, Becker TC, Sherry AD, Newgard CB 2006 Compensatory responses to pyruvate carboxylase suppression in islet β-cells. Preservation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J Biol Chem 281:22342–22351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker TC, Noel RJ, Coats WS, Gomez-Foix AM, Alam T, Gerard RD, Newgard CB 1994 Use of recombinant adenovirus for metabolic engineering of mammalian cells. Methods Cell Biol 43(Pt A):161–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schisler JC, Jensen PB, Taylor DG, Becker TC, Knop FK, Takekawa S, German M, Weir GC, Lu D, Mirmira RG, Newgard CB 2005 The Nkx6.1 homeodomain transcription factor suppresses glucagon expression and regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in islet β-cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:7297–7302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P, Hardy S, Morgan DO 1998 Nuclear localization of cyclin B1 controls mitotic entry after DNA damage. J Cell Biol 141:875–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujio Y, Guo K, Mano T, Mitsuuchi Y, Testa JR, Walsh K 1999 Cell cycle withdrawal promotes myogenic induction of Akt, a positive modulator of myocyte survival. Mol Cell Biol 19:5073–5082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozar-Castellano I, Takane KK, Bottino R, Balamurugan AN, Stewart AF 2004 Induction of β-cell proliferation and retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation in rat and human islets using adenovirus-mediated transfer of cyclin-dependent kinase-4 and cyclin D1. Diabetes 53:149–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycock JW 1993 Polyvinylpyrrolidone as a blocking agent in immunochemical studies. Anal Biochem 208:397–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SA, Quaade C, Constandy H, Hansen P, Halban P, Ferber S, Newgard CB, Normington K 1997 Novel insulinoma cell lines produced by iterative engineering of GLUT2, glucokinase, and human insulin expression. Diabetes 46:958–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmeier HE, BeltrandelRio H, Clark SA, Henkel-Rieger R, Normington K, Newgard CB 1997 Regulation of insulin secretion from novel engineered insulinoma cell lines. Diabetes 46:968–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]