Abstract

Id proteins play important roles in osteogenic differentiation; however, the molecular mechanism remains unknown. In this study, we established that inhibitor of differentiation (Id) proteins, including Id1, Id2, and Id3, associate with core binding factor α-1 (Cbfa1) to cause diminished transcription of the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and osteocalcin (OCL) gene, leading to less ALP activity and osteocalcin (OCL) production. Id acts by inhibiting the sequence-specific binding of Cbfa1 to DNA and by decreasing the expression of Cbfa1 in cells undergoing osteogenic differentiation. p204, an interferon-inducible protein that interacts with both Cbfa1 and Id2, overcame the Id2-mediated inhibition of Cbfa1-induced ALP activity and OCL production. We show that 1) p204 disturbed the binding of Id2 to Cbfa1 and enabled Cbfa1 to bind to the promoters of its target genes and 2) that p204 promoted the translocation from nucleus to the cytoplasm and accelerated the degradation of Id2 by ubiquitin–proteasome pathway during osteogenesis. Nucleus export signal (NES) of p204 is required for the p204-enhanced cytoplasmic translocation and degradation of Id2, because a p204 mutant lacking NES lost these activities. Together, Cbfa1, p204, and Id proteins form a regulatory circuit and act in concert to regulate osteoblast differentiation.

INTRODUCTION

The differentiation of uncommitted mesenchymal cells to osteoblasts is a fundamental process in embryonic development and bone repair. The bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are important regulators of this process (Heldin et al., 1997; Miyazono et al., 2000). They function by binding cell surface receptors; signaling by Smad proteins; and activating bone-specific genes, including core binding factor α-1 (Cbfa1) (Ducy, 2000; Miyazono et al., 2001; Attisano and Wrana, 2002). This process is positively or negatively regulated by a variety of coactivators and corepressors (Ducy et al., 2000; Miyazono et al., 2001; Attisano and Wrana, 2002). Cbfa1, also known as Runx2, PeBP2αA, Osf2, or AML3, is a member of the runt family of transcription factors. It is an essential transcription factor of osteoblast and bone formation (Ducy, 2000). During skeletal development, Cbfa1 is observed first in early mesenchymal condensations, and it is then principally expressed in osteoblasts (Ducy et al., 1997). Cbfa1 −/− mice exhibit a complete lack of ossification, and they die immediately after birth (Komori et al., 1997). Cbfa1 maintains osteoblastic function by regulating the expression of several bone-specific genes such as osteopontin and osteocalcin and by controlling bone extracellular matrix deposition (Ducy, 2000). Mutations in Cbfa1 are found in 65–80% of individuals with cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD) (Lee et al., 1997; Mundlos and Olsen, 1997; Zhou et al., 1999). The molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of CCD are not completely defined. Some mutations of Cbfa1 abolish its DNA binding activity (Lee et al., 1997; Mundlos et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 1999) and others disturb the association of Cbfa1 to its binding partners, including Smads (Xie et al., 2000). It was found that several Cbfa1-binding proteins such as retinoblastoma protein (pRb) (Thomas et al., 2001), p204 (Liu et al., 2005), and Core binding factor β (Kundu et al., 2002; Yoshida et al., 2002) may also play critical roles in bone development.

Inhibitor of differentiation (Id) proteins belong to the helix-loop-helix (HLH) family. Id proteins function as global regulators of gene expression during cell growth and differentiation (reviewed in Ruzinova and Benezra, 2003; Wong et al., 2004). Recent studies have highlighted their role in differentiation of specialized lineages such as lymphocytes (Sun, 1994; Yan et al., 1997), granulocyte (Buitenhuis et al., 2005), vascular endothelial cells (Pammer et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2007), myocytes (Alway et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2002), cardiac myocytes (Ding et al., 2006b), and neuronal cells (Jen et al., 1997; Lyden et al., 1999; Nakashima et al., 2001). Id proteins, which lack a DNA binding domain, associate with other transcriptional factors and prevent them from binding DNA or forming active heterodimers (Benezra et al., 1990b). There are four known members of the Id family (called Id1, Id2, Id3, and Id4), which function by directly modulating the transcriptional function and regulating the protein stability of the basic (b)HLH transcription factors. In skeletal muscle differentiation, the targets of inhibition by Id were known to be the bHLH transcription factors (e.g., MyoD, myogenin, E12, and E47) (Benezra et al., 1990a; Jen et al., 1992; Perk et al., 2005). In cardiac myocyte differentiation, non-bHLH transcription factors Gata4, Nkx2.5, and Tbx5 bind to Id1, Id2, and Id3, and they were inhibited their transactivation. Id proteins were identified to be the early response genes of BMP-2, -6, and -9 in a microarray, and they were found to quickly go down during the terminal differentiation of committed osteoblasts, suggesting that a balanced regulation of Id expression may be critical to BMP-induced osteoblast lineage-specific differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (Ogata et al., 1993; Hollnagel et al., 1999; Amthor et al., 2002); however, the molecular mechanism by which Id proteins regulate osteogenesis remains unknown.

p204 is a member of the interferon-inducible murine p200 family proteins (Choubey et al., 1989; Deschamps et al., 2003; Ludlow et al., 2005). p204 consists of 640 amino acid (aa) residues. In the N-terminal domain (aa 1-216), there is a basic amino acid-rich nuclear localization signal (NLS) and a canonical export signal (NES) required for the translocation of p204 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm during skeletal and cardiac muscle differentiation (Liu et al., 2000; Ding et al., 2006b). The C-terminal domain of p204 consists of two homologous, partially conserved 200-amino acid segments (a and b) in which pRb binding motifs (e.g., LXCXE) are located. Overexpression of p204 is growth inhibitory due in part to its inhibition of rRNA transcription; p204 binds to the ribosomal DNA-specific upstream binding factor transcription factor, and it inhibits its sequence-specific binding to DNA (Liu et al., 1999; Moss and Stefanovsky, 2002). The antiproliferative activity of p204 has been attributed to the binding of p204 to pRb by its pRb binding LXCXE motifs (Gribaudo et al., 1999; Liu et al., 1999; Hertel et al., 2000). However, the antiproliferative activity of p204 does not always depend on pRb (Asefa et al., 2006) (Ding and Lengyel, unpublished data). Overexpression of p204 was found to delay the progression of cells from the G0/G1 phase to the S phase of the cell cycle (Lembo et al., 1998).

p204 was found to be an important regulator of both skeletal and cardiac muscle differentiation (Liu et al., 2000, 2002; Ding et al., 2006a,b). Overexpression of p204 accelerates muscle formation (Liu et al., 2000). This is due at least in part to the binding of p204 to the Id proteins, including Id1, Id2, and Id3, and overcoming the inhibition by the Id proteins of MyoD activity in skeletal muscle differentiation, and Gata4 and Nkx2.5 activity in cardiac myocyte formation (Liu et al., 2002; Ding et al., 2006b). A recent publication revealed the involvement of p204 also in macrophage differentiation (Dauffy et al., 2006). The p204 gene was isolated as a macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF)-responsive gene by using a gene trap approach in the interleukin (IL)-3–dependent myeloid FD-Fms cell line. Moreover forced expression of p204 strongly repressed the IL-3 and M-CSF–dependent proliferation, whereas it promoted the M-CSF–induced macrophage differentiation of FD-Fms cells (Dauffy et al., 2006). p204 may also play an important role in lymphocytic differentiation based on the observation that p204 mRNA levels are higher in less mature double-positive (CD4+CD8+) thymocytes than in single-positive (CD4+ or CD8+) thymocytes (Deftos et al., 2000). Notch1, an essential factor for promoting the maturation of T thymocytes, can transcriptionally up-regulate p204 gene expression during the maturation to both CD4+ and CD8+ single-positive lineages of CD4+CD8+ double-positive thymocytes (Deftos et al., 2000).

We previously reported that p204 acted as a transcriptional coactivator of Cbfa1 and therefore enhanced osteoblast differentiation (Liu et al., 2005) and that pRb is an essential linker between p204 and Cbfa1, thereby increasing its activity (Luan et al., 2007) during the differentiation of pluripotent C2C12 to osteoblast induced by BMP-2. In this study, we report that Id proteins directly associate with Cbfa1 and inhibit Cbfa1-mediated osteogenic differentiation and that p204 overcomes these inhibitions by Id proteins, and we focus on the molecular mechanisms underlying these processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of a Recombinant Adenovirus Expressing Id2

The AdEasy adenoviral vector system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to construct an adenovirus expressing Id2 (Ad-Id2). Briefly, Id2 cDNA was inserted into the KpnI and HindIII sites in pAdTrack-cytomegalovirus (CMV) vector. The predigested recombinant adenovirus DNA was transfected into human embryonic kidney 293 cells. After collecting the medium supernatant that contains recombinant adenovirus, multiplicity of infection (MOI) for the recombinant adenovirus was determined according to the standard protocol (Nifuji et al., 2004). The expression of recombinant virus in infected C2C12 cells was tested by Western blotting with specific antibodies.

Generation of stable lines that constitutively expressed Id2-Flag plus either p204 or p204 mutant lacking NES. Stable cell lines were established by transiently transfecting C2C12 cells with pCMV-p204, or pCMV-p204ΔNES, or/and pCMV-Id2-Flag constructs, together with the selective plasmid pMiniHgh (provided by Dr. X. Y. Fu, Yale University School of Medicine), which conferred hygromycin resistance upon the cells, at a ratio of 10:1. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were split into 15-cm culture plates and selected with 1 mg/ml hygromycin (Invitrogen) in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Invitrogen). After 2 wk, individual colonies were picked, and then they were expanded and tested for p204 or Id2-Flag expression of the relevant lines, by using Western analysis. Stable lines were maintained under constant hygromycin (200 μg/ml).

Isolation and Culture of Mouse Bone Marrow Stromal Cells (BMSCs)

Mouse bone marrow was isolated by flushing the femurs and tibiae of 8- to 12-wk-old female BALB/c mice with 0.6 ml of improved minimal essential medium (IMEM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin/100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 2 mM glutamine (Invitrogen), and then it was filtered through a cell strainer (Falcon; BD Biosciences Discovery Labware, Bedford, MA). Cells were centrifuged for 10 min at 260 × g, washed by the addition of fresh medium, centrifuged again, resuspended, and plated out in IMEM supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin/100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine at a density of ∼2 × 106 cells/cm2 in 25-cm2 plastic culture dishes. The cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. After 72 h, nonadherent cells and debris were removed, and the adherent cells were cultured continuously. Cells were grown to confluence, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and lifted by incubation with 0.25% trypsin/2 mM EDTA (Invitrogen) for 5 min. Nondetached cells were discarded and the remaining cells were regarded as passage 1 of the BMSC culture. Confluent BMSCs were passaged and plated out at 1:2–1:3 dilutions. At passage 3, cells were transferred to DMEM (Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% FBS for differentiation studies.

Alkaline Phosphatase and Osteocalcin Assays

C2C12 cells or BMSCs transducted with Ad-Cbfa1, or/and Ad-Id2, or/and Ad-p204 were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum for 4 d. Cells were then lysed for measuring ALP activity, and medium was used for determining OCL production. In brief, the ALP assay mixtures contained 0.1 M 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mM MgCl2, 8 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium, and cell homogenates. After 30-min incubation at 37°C, the reaction was stopped with 0.1 N NaOH, and the absorbance was read at 405 nm. A standard curve was prepared with p-nitrophenol (Sigma-Aldrich). Each value was normalized to the protein concentration. The amount of OCL secreted into the culture medium was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using a mouse osteocalcin assay kit (Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA) per the manufacturer's protocol.

Coimmunoprecipitation (CoIP) Assay

C2C12 cells cultured in 35-mm dishes were cotransfected with Cbfa1 (2 μg) together with either Flag-Id1 (2 μg), Flag-Id2 (2 μg), Flag-Id3 (2 μg), or Flag-Id4 (2 μg) expression vector by using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). Cells were harvested after incubation in DMEM, 10% FCS for 48 h, and then they were lysed in lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 50 mmol/l Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 0.15 mol/l NaCl, 0.01 mol/l sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, 1% Trasylol, and protein inhibitor cocktails, Sigma-Aldrich). Protein samples (500 μg) were loaded with 10 μg of M2 monoclonal anti-Flag (Sigma-Aldrich) or Cbfa1 polyclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and then they were immunoprecipitated by incubation with protein A beads at 4°C overnight. The proteins retained on the loaded beads were washed and eluted following a published procedure (Ding et al., 2006b). Western blotting was conducted with anti-Cbfa1 as well as M2 monoclonal anti-Flag.

To identify the domain of Cbfa1 that binds to Id2, a series of Cbfa1 deletion constructs (2 μg) and Id2-Flag expression vector were cotransfected into C2C12 cells, and the cells were cultured for 3–4 d. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Cbfa1 (N-terminal) antibody, and the immunoprecipitated complex was detected using Western blotting with anti-Flag antibody.

To verify the interaction of endogenous Id2 and Cbfa1 protein, cell lysates prepared from C2C12 cells treated with 300 ng/ml BMP-2 for 12 h were immunoprecipitated with anti-Cbfa1 antibody and the immunoprecipitated complex was detected using Western blotting with anti-Id2 antibody.

To determine whether p204 enhances the Id2 ubiquitination in the cells, Id2-Flag expression plasmid and pCMV-ubiquitin-hemagglutinin (UB-HA) together with various amount of p204 expression plasmid were transfected into C2C12 cells. Three days later, MG132 (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to block the proteasomal degradation of Id2-Flag. After further 6-h incubation, total protein of cell lysates were prepared and inoculated with anti-Flag antibody and detected with anti-hemagglutinin antibody by Western blotting.

Expression and Purification of Glutathione Transferase (GST)-Fusion Proteins

For expression of GST fusion proteins, the appropriate plasmid pGEX-Id2, pGEX-204 pGEX-Id2N(1-30), pGEX-Id2HLH(30-84), and pGEX-Id2C(84-134) was transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α (Invitrogen). Fusion proteins were affinity purified on glutathione-agarose beads, as described previously (Liu et al., 1999).

GST Pull-Down Assay

For examination of the binding of Id2 to Cbfa1 and its deletion mutants, Glutathione-Sepharose beads (50 μl) preincubated with either purified GST (0.5 μg, serving as control) or GST-Id2 were incubated with cell lysates of C2C12 cells transfected with full-length Cbfa1 and a series of mutant Cbfa1 fragments expression plasmids. Bound proteins were resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE and detected by Western blotting with anti-Cbfa1N antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

In the binding assay for dissecting the domain of Id2 required for interaction with Cbfa1, glutathione-Sepharose beads (50 μl) preincubated with purified GST-Id2N, GST-Id2HLH, or GST-Id2C were incubated with cell lysates bearing Cbfa1. Bound proteins were processed as described above.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

Using a ChIP assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Charlottesville, VA), C2C12 progenitor cells transfected with expression plasmids encoding Cbfa1, Id2-Flag, or/and p204 as well as induced with BMP-2 for various times were treated with formaldehyde (1% final concentration). The cells were then washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in SDS lysis buffer (1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, and 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1). The lysates were sonicated to shear the DNA to a length between 200 and 1000 base pairs. The sonicated supernatant fraction was diluted with ChIP dilution buffer (0.01% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, and 150 mM NaCl), and then it was incubated with antibodies against Cbfa1 (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), against Id2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), against p204 or preimmune serum with rotation at 4°C overnight. To collect the DNA–protein complexes, a salmon sperm DNA–protein A–agarose slurry was added to the mixture, and then it was incubated with rotation at 4°C for 1 h, and the DNA–protein–agarose was pelleted by centrifugation. After extensive washing of the pellet with a series of buffers (low salt wash buffer, high salt wash buffer, LiCl immune complex wash buffer, and 1× Tris/EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.1, and 1 mM EDTA), the pellet was dissolved in 250 μl of elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3, and 0.01 mg/ml herring sperm DNA), and centrifuged to remove the agarose. The supernatant fraction was treated with 20 μl of 5 M NaCl and heated to 65°C for 4 h to reverse the protein–DNA cross-linking. After treatment with EDTA and proteinase K, the supernatant fraction was extracted with phenol-chloroform, and then it was precipitated with ethanol to recover the DNA. For amplification of the osteocalcin promoter region, 10% of the chromatin-immunoprecipitated DNA was polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified using as forward primer 5′-CTGCAATCACCAACCACAGC and as reverse primer 5′-CTGCACCCTCCAGCATCCAG. Forty cycles of PCR (at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s) were performed. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel.

Real-Time PCR and Reverse Transcription (RT)-PCR

Real-time PCR with SYBR Green chemistry was performed to check the expression of p204 and Cbfa1 in the Ad-Id2 transducted C2C12 cells, by using the ABI Prism 7500 PCR amplification system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequences of Cbfa1-specific primers are 5′-TGA TGA CAC TGC CAC CTG TG-3′ and 5′-ACT CTG GCT TTG GGA AGA GC-3′. Sequences of p204-specific primers are 5′-GGA AAG AGA CAA CCA AGA GC-3′ and 5′-TGG CTT GTA GTT GAT GTA GG-3′. Sequences of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)-specific primers are 5′-ACTTTGTGAAGCTCATTTCCTGGTA-3′ and 5′-GTGGTTTGAGGGCTCTTACTCCTT-3′. A reaction mixture containing the master mixture with SYBR Green fluorescent dye (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and the selective primers was added to a 96-well plate, together with 2 μl of cDNA template, for a final reaction volume of 20 μl per well, and the mixture was run for an initial step at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of amplification at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 60 s. All the data were collected during the extension step and expressed as arbitrary fluorescence units per cycle. A melting curve was obtained at the end of the PCR reaction to verify that only one product was produced. The mRNA expression of Cbfa1, p204, β-actin, and GAPDH was also visualized by semiquantitative RT-PCR (OneStep RT-PCR kit; QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) with same primers as used in real-time PCR assays.

Immunofluorescent Cell Staining

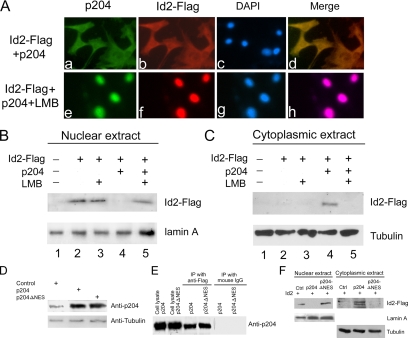

To determine whether leptomycin B (LMB) affects the cytoplasmic translocation, C2C12 cells stably transfected with Id2-Flag together with or without p204 expression plasmid were cultured in the presence of 300 ng/ml BMP-2 with or without 2 ng/ml LMB for 2 d. Cell monolayers were screened using a standard indirect immunofluorescent staining procedure using monoclonal antibodies to Flag and polyclonal antibodies to p204 protein (1:400) and rhodamine-labeled goat-anti-mouse or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat-anti-rabbit antibody as secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Nuclei were visualized with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Fractionation and Western Blotting Analyses

To determine whether LMB affects the subcellular distribution of exogenous Id2-Flag and p204, C2C12 cells transfected with p204 or/and Id2-Flag expression plasmid were cultured in the presence or absence of 2 ng/ml LMB. Nuclear/cytoplasmic fractionation was carried out as described by McMahon et al. (Karlsson et al., 2004). Monolayer cells were trypsinized, and the cell suspension was washed with three volumes of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline by repeated centrifugation (500 × g for 2 min at 4°C). The cell pellet was gently resuspended in 300 μl of buffer 1 [250 mM sucrose, 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM iodoacetamide, and 0.5% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40 supplemented with Complete, EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science, Basel, Switzerland)]. After 5 min on ice, the nuclei were pelleted, and the resulting supernatant was harvested and is referred to as cytoplasmic extract. The nuclei were gently resuspended in 1 ml of buffer 2 (250 mM sucrose, 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM iodoacetamide with EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture), and they were pelleted. Nuclei lysed in 100 μl of buffer 3 [50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40, 0.5% (wt/vol) deoxycholic acid, and 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS supplemented with Complete, EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science)] on ice for 15 min. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation (16,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C), and the supernatant was referred to as the nuclear fraction. Efficient cytoplasmic and nuclear fractionation was confirmed by Western blotting analysis using anti-tubulin antibody for cytoplasmic fraction and anti-lamin A antibody for nuclear fraction. The levels of endogenous Id2 or Id2-Flag protein from cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were analyzed by Western blotting by using anti-Id2 or anti-Flag antibody.

Assay of the Acceleration of the Degradation of Id2 by p204 In Vivo

C2C12 cells were transfected with 10 μg of pCMV-Id2-Flag, as indicated without or with 10 μg of pCMV-p204 or 10 μg of pCMV-p204ΔNES by using Lipofectamine 2000. Twenty-four hours later, the cultures were digested with trypsin/EDTA, pooled, replated into 6-cm tissue culture dishes, and incubated for 24 h. At this time, 100 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) was added, together with 20 μM MG132. After the indicated times of incubation, the various cultures were lysed in NP-40 buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM EDTA, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 μg/ml pepstatin). The lysates were analyzed for Id2-Flag by Western blotting with M2-Flag antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich). To confirm the ubiquitin E1-activating enzyme-dependent acceleration of Id2 Degradation by p204 in vivo, C2C12 cells (Nishimoto et al., 1980) were cotransfected with 8 μg of pCMV-Id2FLAG, and, as indicated, without or with 8 μg of pCMV204 and without or with 8 μg of pCMV-Ub-HA. After 24 h, the cultures were supplemented with 100 μg/ml CHX and 20 μM MG132 for another 24 h, harvested, and lysed. Immunoprecipitation experiments were performed from cell lysates using anti-Flag monoclonal antibody (mAb) as immunoprecipitating antibody. The ubiquitinized Id2-Flag [Id2-Flag-(UB)n] in lysate precipitates was assessed with anti-HA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) by Western blotting.

RESULTS

Overexpression of Id2 Inhibits the Cbfa1-activated Osteogenic Differentiation

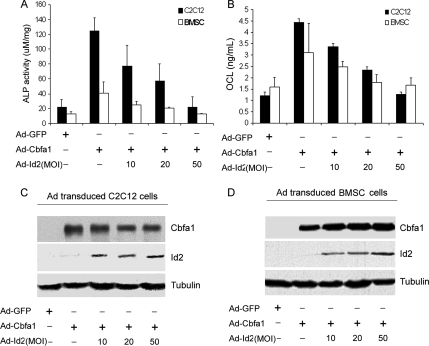

Cbfa1, an essential transcription factor of osteogenesis and bone formation, controls the expression of genes that are activated during osteoblast differentiation, including ALP and OCL (Nishimura et al., 2002). Id proteins have been implicated in the regulation of osteoblast differentiation and bone formation (Maeda et al., 2004; Peng et al., 2004), but the molecular mechanism by which Id proteins regulate osteogensis remain unknown. To address this issue, we sought to determine whether Id proteins affect the Cbfa1 activity by using the pluripotent mesenchymal C2C12 cells, a well-established cell model for studying osteogenesis in vitro (Katagiri et al., 1994; Munz et al., 2002; Eliazer et al., 2003). For this purpose, we generated a recombinant adenovirus encoding Id2, and then we determined the effect of Id2 on the Cbfa1-mediated activity of ALP and production of osteocalcin, two marker genes for osteoblasts. As shown in Figure 1, infection of C2C12 with the recombinant adenovirus encoding Cbfa1 (Ad-Cbfa1) led to a high ALP activity and a robust production of osteocalcin. This Cbfa1-dependent induction of ALP and osteocalcin was dramatically inhibited by coinfection with Ad-Id2 in a dose-dependent manner. More significantly, similar results were also observed with primary bone marrow stromal cells. These data suggest Id2 protein is a potent inhibitor of Cbfa1-mediated gene activation in the course of osteogenesis.

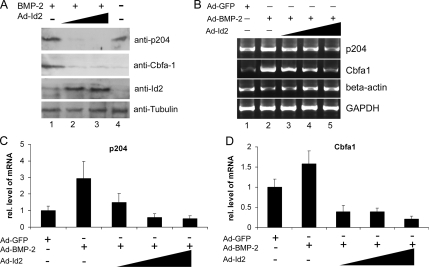

Figure 1.

Id2 inhibits the Cbfa1-mediated osteogenesis assayed by ALP and OCL. (A) Id2 inhibits the Cbfa1-dependent ALP activity in a dose-dependent manner. C2C12 cell lines and BMSCs were infected either Ad-GFP (MOI 50, serves as a control) or Ad-Cbfa1 (MOI 20) with or without Ad-Id2 (at different MOI) for 4 d, and the cell lysates were used for determining the ALP activity. (B) Id2 inhibits the Cbfa1-dependent OCL production in a dose-dependent manner. C2C12 cell lines and BMSCs were infected as described in A, and the cell culture media were used for determining OCL level. (C and D) Expression of Cbfa1 and Id2 in C2C12 and BMSCs infected with indicated adenoviruses. Cell lysates were prepared from C2C12 (C) and BMSCs (D) infected with various adenoviruses, as indicated, and detected by Western blot with anti-Cbfa1, anti-Id2, and anti-tubulin (internal control) antibodies.

The Id1, Id2, and Id3 Proteins Associate with Cbfa1 in the Course of Osteogenesis

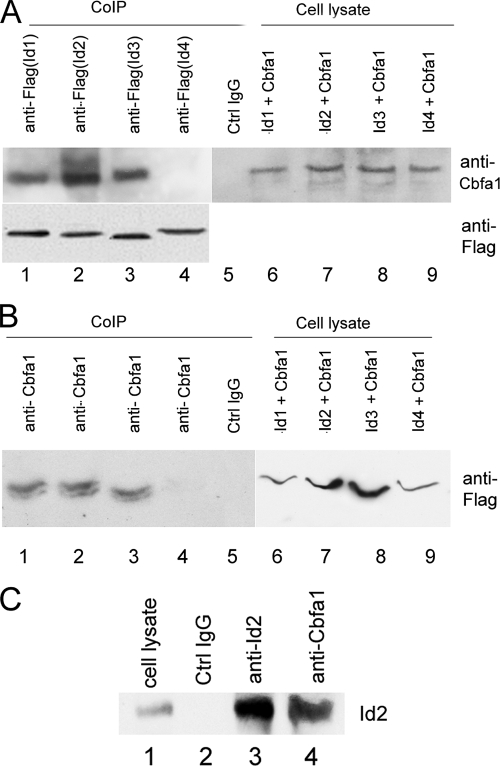

Id protein family members bind to transcription factors and block their association with DNA, thereby inhibiting their actions (Sun et al., 1991; Pesce and Benezra, 1993). We examined whether Id proteins associate with Cbfa1 via CoIP assay. C2C12 cells were transfected with a mammalian expression plasmid encoding Cbfa1 and a plasmid that encodes either Id1-Flag, Id2-Flag, Id3-Flag, or Id4-Flag (Ding et al., 2006b). The transfected cell extracts were incubated with control immunoglobulin (IgG) (negative control) or anti-Flag, and the complexes were detected with anti-Cbfa1 or anti-Flag antibody (Figure 2A). A specific Cbfa1 band was immunoprecipitated by anti-Flag antibody from the cell lysates bearing Id1-Flag, Id2-Flag, or Id3-Flag, but not Id4-Flag, demonstrating that Cbfa1 specifically associates with Id1, Id2, Id3, but not Id4. Note that anti-Flag antibody efficiently immunoprecipitated all Flag-tagged Id proteins. Control IgG and cell lysates were negative and positive control. These findings were further verified with an opposite CoIP assay in which anti-Cbfa1 antibody was used for immunoprecipitation and anti-Flag for detection (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Id proteins associate with Cbfa1 in vivo. (A) Cell lysates prepared from C2C12 cells transfected with an expression plasmid encoding Cbfa1 and an expression plasmid encoding Flag-Id1, Flag-Id2, Flag-Id3, or Flag-Id4, as indicated, were incubated with either anti-Flag (lanes 1–4) or control IgG (lane 5), followed by protein A-agarose. The immunoprecipitated protein complex and cell extracts (lanes 6–9, positive controls) were examined by Western blotting with anti-Cbfa1 or anti-Flag antibody. (B) Cell lysates prepared as described in A were incubated with anti-Cbfa1 (lanes 1–4) or control IgG (lane 5), and the immunoprecipitated proteins and cell extracts (lanes 6–9, positive controls) were examined by Western blotting with anti-Flag mAb. (C) Id2 binds to Cbfa1 during BMP-2–induced osteogenesis. Cell lysates were prepared from C2C12 cells that were treated with 300 ng/ml BMP-2 protein for 12 h, and then they were incubated with either control IgG (lane 2), anti-Id2 (lane3), or anti-Cbfa1 (lane 4), and the immunoprecipitated protein complex and cell extracts (lane 1, positive control) were examined by Western blotting with anti-Id2 antibody.

To determine whether Cbfa1/Id2 complex is detectable during osteogenesis, cell lysates prepared from C2C12 cells treated with BMP-2 for 12 h were incubated with control IgG (negative control), anti-Id2 (positive control), or anti-Cbfa1, and the complexes were detected with anti-Id2 polyclonal antibody (Figure 2C). A specific Id2 band was immunoprecipitated by anti-Id2 antibody (lane 3) and anti-Cbfa1 antibody (lane 4), but not by control IgG antibody (lane 2), demonstrating that Id2 specifically associates with Cbfa1 also in the BMP-2–trigged osteogenesis.

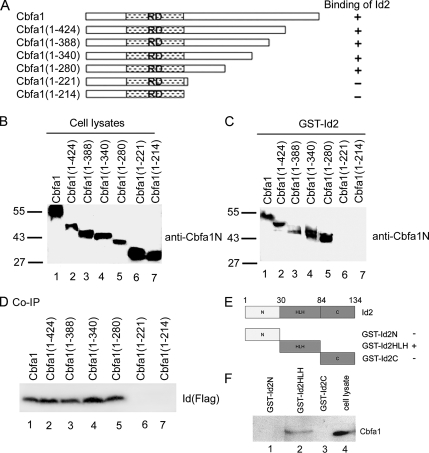

A 60-Amino Acid Segment (aa 221-280) of Cbfa1 and HLH Domain (aa 30-84) of Id2 Are Required for the Association of Cbfa1 and Id2

To dissect the segments of Cbfa1 required for binding to Id2, a series of Cbfa1 deletion constructs (Figure 3A) encoding truncated Cbfa1 proteins in mammalian cells (generously provided by Drs. K. Ito and Y. Toshiyuki of the Institute for Virus Research at Kyoto University) were transfected into C2C12 cells. Pull-down assays involving the immobilized GST-Id2 and cell extracts prepared from C2C12 cells bearing Cbfa1 mutants (Figure 3B) were performed to determine the ability of the various Cbfa1 mutants to associate with Id2. Immunoblotting using anti-Cbfa1N antibody against the N-terminal domain of Cbfa1 showed that C-terminal domain deletion mutants of Cbfa1, including Cbfa1 (1-424), Cbfa1 (1-388), Cbfa1 (1-340) and Cbfa1 (1-280), bind GST-Id2, as does the full-length factor, whereas further deletion mutant Cbfa1 (1-221) abolishes the interaction of the two polypeptides (Figure 3C), suggesting that the 60-amino acid segment (aa 222-280) of Cbfa1 contains the molecular determinants for interaction with Id2. This finding was further verified using a set of CoIP assay with cell lysates bearing Id2-Flag and one of the Cbfa1 C-terminal deletion mutants, as indicated (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Identification of binding domains required for interaction between Cbfa1 and Id2. (A) Schematic structure of a series of Cbfa1 mutant constructs used to map the binding domain of Cbfa1 to Id2. Numbers mean amino acid residues in Cbfa1; + or − means binding or lack of binding respectively. (B) Western blotting assay. C2C12 cells were transfected with an expression plasmid encoding either Cbfa1 or one of its mutants, as shown in A, and the expression of the Cbfa1 or its mutants was detected with anti-Cbfa1N antibody. (C) A fragment (aa 222-280) of Cbfa1 is required for binding to Id2 (GST pull-down assay). Purified GST–Id2 fusion protein immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads was incubated with cell extracts expressing Cbfa1 or various Cbfa1 mutant segments as shown in B. Proteins trapped by the interaction with GST-Id2 were examined by immunoblotting with anti-Cbfa1 N antibodies. (D) CoIP assay for dissecting the segment of Cbfa1 required for binding Id2. Cell lysates prepared from C2C12 cells transfected with an expression plasmid encoding Id2-Flag and an expression plasmid encoding either Cbfa1 or one of its mutans, as described above, were incubated with anti-Cbfa1 N antibody, followed by protein A-agarose. The immunoprecipitated proteins were examined by Western blotting with anti-Flag mAb. (E) Schematic diagrams of GST-Id2 segment fusion proteins used to identify an Id2 segment binding to p204. The numbers refer to amino acid residues in Id2. The binding or lack of binding of the various GST-Id2 segments to p204, as shown in F, is indicated. (F) HLH domain of Id2 protein is sufficient to bind to Cbfa1 (GST pull-down assay). Purified GST-Id2N (lane 1), GST-Id2HLH (lane 2), or GST-Id2C (lane 3) fusion protein immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads was incubated with C2C12 cell extracts expressing Cbfa1 protein. Proteins trapped by the interaction with GST-Id2 segments and cell lysates (serves as a positive control) were examined by immunoblotting with anti-Cbfa1 antibody.

We previously generated GST fusion proteins of Id segments, including GST-Id2N(1-30), GST-Id2HLH(30-84), and GST-Id2C(84-134) (Liu et al., 2002). We used these Id2 mutants to determine the ability of the various regions of Id2 protein to associate with Cbfa1. Pull-down assays involving the immobilized GST-Id2N, GST-Id2HLH, GST-Id2C (Figure 3E), and cell extracts prepared from C2C12 cells transfected with full-length Cbfa1 expression plasmid (Figure 3F) were performed. Immunoblotting using anti-Cbfa1N against the N-terminal domain of Cbfa1 shows that GST-Id2HLH, but not GST-Id2N or GST-Id2C, binds Cbfa1. Together, a 60-amino acid segment (aa 221-280) of Cbfa1 and HLH domain (aa 30-84) of Id2 are important for the binding of Id2 to Cbfa1.

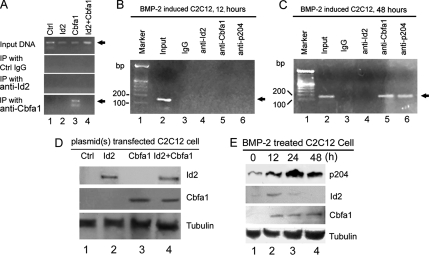

Id2 Inhibits the Sequence-specific Binding of Cbfa1 to OCL Promoter

We used a ChIP assay to determine whether association of Id2 and Cbfa1 affects the binding of Cbfa1 to its target DNA, ChIP was first carried out using C2C12 cells transfected with expression plasmids encoding Id2, Cbfa1, or both (Figure 4A), and the expressions of Cbfa1 and Id protein in the transfected cells are shown in Figure 4D. After cross-linking the proteins to the DNA, they were associated with using formaldehyde, we lysed the cells, sheared the chromatin by sonication, and immunocoprecipitated protein–DNA complexes using IgG (negative control) as well as anti-Id2 or anti-Cbfa1 antibodies. We examined the purified DNA samples by PCR with primers that span the Cbfa1 binding site in the OCL promoter. The PCR product with expected size was observed from the DNA sample purified from the immunoprecipitates with antibodies to Cbfa1, but not that obtained from immunoprecipitation with the IgG control or Id2 antibody. In addition, anti-Cbfa1 antibody failed to precipitate the DNA from the cells that were cotransfected with Cbfa1 and Id2 expression plasmids. These results indicate that Id2 is able to disturb the binding of Cbfa1 to the osteocalcin promoter in transfected cells in vivo.

Figure 4.

Id2 inhibits the binding of Cbfa1 to the osteocalcin promoter (ChIP assay). (A) Id2 disturbs the association of Cbfa1 with the OCL promoter in vivo. C2C12 cells were transfected with an expression vector (Ctrl), an expression plasmid encoding Id2-Flag, Cbfa1 or both. After cross-linking with formaldehyde cell lysates were prepared, sonicated, and subjected to immunoprecipitation with control IgG, anti-Flag (Id2), or anti-Cbfa1. Purified DNA from the cell lysate as input DNA and DNA recovered from immunoprecipitation were amplified by PCR using specific primers for Cbfa1 binding region in OCL promoter. Input DNA was used as positive control. (B and C) Early induction of Id2 inhibits the binding of Cbfa1 to the osteocalcin promoter in the BMP-2–induced osteogenesis. C2C12 cells treated with 300 ng/ml BMP-2 protein for 12 h (B; Id2 is highly expressed) or 48 h (C; Id2 is undetectable) were cross-linked by formaldehyde treatment and lysed. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with control IgG (lane 2), anti-Id2 (lane 3), anti-Cbfa1 (lane 4), or anti-p204 (lane 5). Purified DNA from the cell lysate (input DNA, positive control) and DNA recovered from immunoprecipitation were amplified by PCR using specific primers for Cbfa1 binding region in OCL promoter. (D) Expression of Id2 and Cbfa1 in C2C12 cells transfected with corresponding plasmids. Cell lysates were prepared from C2C12 cells transfected with various expression plasmid as described in A and detected by Western blot with anti-Id2 (lane 1), anti-Cbfa1 (lane 2), and anti-tubulin (lane 3) antibodies. (E) Expression of Id2, Cbfa1 and p204 during the BMP-2–treated C2C12 cells. C2C12 cells treated with 300 ng/ml BMP-2 protein for various times, as indicated, and the total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot with anti-p204, anti-Id2, anti-Cbfa1, and anti-tubulin antibody (internal control), respectively.

Similar ChIP assays were performed using C2C12 cells induced to osteogenic differentiation by BMP-2. The aim of these experiments was to test whether Id2, an early response gene of BMP-2, regulates the association of Cbfa1 transcription factor and the osteocalcin promoter in C2C12 cells undergoing osteogenic differentiation. The results of the ChIP test as analyzed by PCR are shown in Figure 4, B and C. Anti-Cbfa1 antibody did not precipitate the DNA from C2C12 cells that were treated with BMP-2 for 12 h when Id2 was highly expressed (Figure 4E), whereas it efficiently immunoprecipitated DNA from the cells treated with BMP-2 for 48 h when Id2 was undetectable (Figure 4E). These results, together with the demonstration that Cbfa1 and Id2 form a complex in vivo (Figure 2), indicate that the endogenous Id2 prevents the binding of Cbfa1 to DNA via forming Id2/Cbfa1 complex at early stage of osteogenic differentiation. In accordance with our previously report (Liu et al., 2005), anti-p204 also could precipitate osteocalcin promoter DNA at 48 h time point in that p204 and Cbfa1 form an activation complex in the osteocalcin promoter during osteoblast differentiation.

Ectopic Id2 Inhibits the Expression of Cbfa1 and p204 in C2C12 Cultures Induced to Differentiate to Osteoblasts by BMP-2

Id proteins inhibit the expression of corresponding tissue-specific transcription factors in the course of various kinds of lineage differentiation. We determined whether Id2 affected the level of endogenous Cbfa1 and p204 in the C2C12 cells undergoing osteogenic differentiation trigged by BMP-2. As shown in Figure 5A, Id2 protein was clearly elevated in the C2C12 cells transduced by Ad-Id2 virus; BMP-2 induced expressions of Cbfa1 and p204 and ectopic expression of Id2 resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition on these inductions.

Figure 5.

Id2 inhibits the expression of p204 and Cbfa1 during BMP-2–induced osteogenesis. (A) Id2 decreases the levels of p204 and Cbfa1 proteins in the BMP-2–induced osteogenesis. C2C12 cell lines were infected with Ad-BMP-2 (MOI 20) without or with Ad-Id2 (MOI 10, 20), as indicated, for 2 d, and the levels of p204, Cbfa1, Id2, and tubulin (internal control) in the cell lysates were visualized by Western blotting with corresponding antibodies, as indicated. (B) Id2 inhibits the induction of p204 or Cbfa1 mRNA by BMP-2, assayed by RT-PCR. C2C12 cell lines were infected with either Ad-GFP (MOI 20), Ad-BMP-2 (MOI 20) without or with Ad-Id2 (MOI 10, 20), as indicated, for 2 d, and the total RNA was used for determining the mRNA level of p204, Cbfa1, β-actin, and GAPDH. (C) Id2 inhibits the induction of p204 mRNA by BMP-2, assayed by real-time PCR. The cells were processed as in described in B and the mRNA level of p204 and GAPDH was measured by real-time PCR. Expression of p204 was normalized against GAPDH endogenous control. The units are arbitrary, and the leftmost bar in each panel indicates a relative level of p204 mRNA of 1. (D) Id2 inhibits the induction of Cbfa1 mRNA by BMP-2, assayed by real-time PCR. The cells were processed, and the data were analyzed as described in C. In addition, Cbfa1 mRNA was measured.

To further determine whether Id2 inhibits the expressions of Cbfa1 and p204 by affecting gene transcription, we examined the mRNA levels of both Cbfa1 and p204 from Ad-Id2– or Ad-GFP (as a negative control)–transduced C2C12 cells cultured in the presence of BMP-2 (Figure 5, B–D). Both regular RT-PCR and real-time PCR with primers specific to Cbfa1 or p204 demonstrated that Id2 specifically down-regulated the expression of Cbfa1 and p204 gene, because overexpression of Id2 did not affect the expression of β-actin and GAPDH. Collectively, these results clearly demonstrated that Id2 inhibits the transcription of Cbfa1 and p204 genes in BMP-2–induced osteogenesis of C2C12 cells.

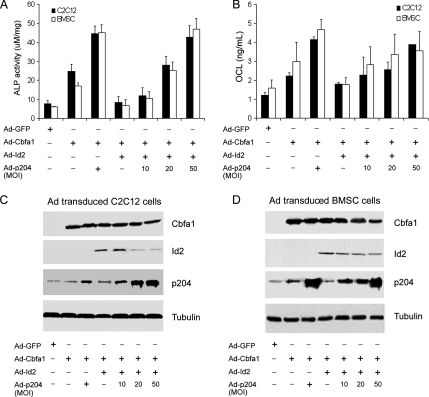

Id2 Inhibits Cbfa1-dependent ALP Activity and OCL Production and p204 Overcomes Its Inhibition

We reported previously that p204 associates with Cbfa1, acts as a cofactor of Cbfa1, and enhances Cbfa1-dependent gene activation and osteogenesis (Liu et al., 2005). These findings, together with the facts that Id proteins also bind to Cbfa1 and inhibit Cbfa1-dependent gene activation and osteogenesis, led us to investigate whether p204 is capable of overcoming the inhibition of Cbfa1 activity by Id proteins. The data in Figure 6reveal that this is the case. Cbfa1-activated ALP activity (Figure 6A) and OCL production (Figure 6B) were dramatically reduced when Id2 protein was coexpressed, and this repression of Id2 on Cbfa1 action was overcome by p204 in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 6.

p204 overcomes the inhibition of Cbfa1-mediated osteogenesis by Id2, assayed by ALP and OCL. (A) Id2 inhibits the Cbfa1-dependent ALP activity; p204 overcomes it. C2C12 cell lines and BMSCs were infected with Ad-GFP (MOI 50, control), Ad-Cbfa1 (MOI 20), and Ad-Cbfa1 plus Ad-Id2 (MOI 20) without or with Ad-p204 (at different MOI), as indicated, for 4 d, and the cell lysates were used for determining the ALP activity. (B) p204 overcomes the inhibition of the Cbfa1-mediated OCL production by Id2. C2C12 cell lines were infected as described in A, and the cell culture media were used for determining OCL level. (C and D) Expression of Cbfa1 and Id2 in C2C12 and BMSCs infected with indicated adenoviruses. Cell lysates were prepared from C2C12 (C) and BMSCs (D) infected with various adenoviruses, as indicated, and they were detected by Western blot with anti-Cbfa1, anti-Id2, anti-p204, and anti-Tubulin (internal control) antibodies.

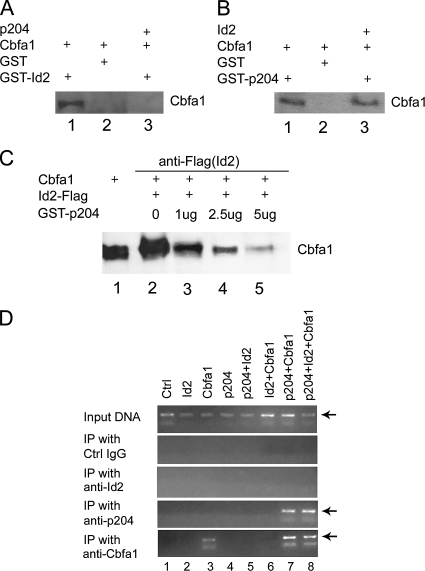

p204 Disturbs Id2/Cbfa1 Complex and Enables Cbfa1 to Bind to the Osteocalcin Promoter

To elucidate the molecular mechanism by which p204 overcomes the Id2-mediated inhibition on Cbfa1, we determined whether p204 prevented the binding of Id2 to Cbfa1 and freed Cbfa1 to bind DNA. As reveled in Figure 7A, GST-Id2, but not GST, could efficiently pull down Cbfa1 from the cell lysates bearing Cbfa1, whereas GST-Id2 failed to bind to Cbfa1 from the cell lysates bearing Cbfa1 and p204, indicating that p204 was able to disturb the association of Id2 and Cbfa1. Interestingly, Id2 did not affect the interaction between p204 and Cbfa1 (Figure 7B), suggesting that p204 binds to Cbfa1 with higher affinity than does Id2. The inhibition on the binding of Id2 to Cbfa1 by p204 was further verified with a CoIP assay (Figure 7C). Anti-Flag antibody efficiently immunoprecipitated Cbfa1 from the cell extracts of C2C12 cells transfected with Cbfa1 and Id2-Flag expression plasmids (lane 2), whereas addition of purified GST-p204 in the cell lysates abolished this complex in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 7.

p204 disturbs the binding of Id2 to Cbfa1 and enables Cbfa1 to bind to DNA. (A) Id2 fails to bind Cbfa1 in the presence of p204 (GST pull-down assay). Purified GST (lane 2) or GST-Id2 fusion protein (lanes 1 and 3) immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads was incubated with the extracts of C2C12 cells expressing Cbfa1 (lanes 1 and 2) alone or Cbfa1 plus p204 protein (lane 3). Proteins trapped by the interaction with GST or GST-Id2 were examined by immunoblotting with anti-Cbfa1 antibodies. (B) p204 still binds Cbfa1 in the presence of Id2 protein (GST pull-down assay). Purified GST (lane 2) or GST-p204 fusion protein (lanes 1 and 3) immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads was incubated with the extracts of C2C12 cells expressing Cbfa1 (lane 1) alone or Cbfa1 plus Id2 (lanes 2 and 3). Proteins trapped by the interaction with GST or GST-p204 were examined by immunoblotting with anti-Cbfa1 antibodies. (C) Addition of purified p204 protein disrupts the interaction between Cbfa1 and Id2 in a dose-dependent manner (CoIP assay). C2C12 cell extracts expressing Cbfa1 and Id2-Flag protein in the absence or presence of various amounts of purified GST-p204, as indicated, were incubated with anti-Flag, followed by protein A-agarose beads. The immunoprecipitated proteins and cell extracts (lane 1, positive control) were examined by Western blotting with anti-Cbfa1 antibody. (D) p204 overcomes the inhibition on the binding of Cbfa1 to the osteocalcin promoter by Id2 in vivo (ChIP assay). C2C12 cells were transfected with an expression vector (Ctrl), an expression plasmid encoding Id2, Cbfa1, p204, or various combinations, as indicated. After cross-linking with formaldehyde cell lysates were prepared, sonicated, and subjected to immunoprecipitation with control IgG, anti-Id2, anti-p204, or anti-Cbfa1. Purified DNA from the cell lysate as input DNA (positive control) and DNA recovered from immunoprecipitation were amplified by PCR using specific primers for Cbfa1 binding region in OCL promoter.

We next performed ChIP assay to examine whether p204 could enable Cbfa1 to bind to DNA, and the data in Figure 7D demonstrated this was the case. As in Figure 4, Cbfa1 bound to the transfected osteocalcin promoter (lane 3), and Id2 completely inhibited the association of Cbfa1 to DNA (lane 6), whereas the binding of Cbfa1 to DNA was restored when p204 protein was coexpressed. These results clearly indicated that p204 prevented the formation of Id2/Cbfa1 complex and freed Cbfa1 to associate with the promoters of its target genes, including osteocalcin.

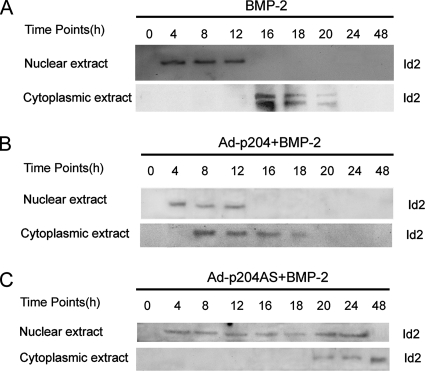

Id2 Translocates from the Nucleus to the Cytoplasm in C2C12 Cells Undergoing Osteogenic Differentiation Induced by BMP-2, and p204 Accelerates This Translocation

Because p204 was previously shown to promote the translocation of ectopic Id2 protein from the nucleus to the cytoplasm in the course of skeletal and cardiac muscle differentiation (Liu et al., 2002; Ding et al., 2006b), we next examined whether p204 mediated the cytoplasmic translocation of Id2 during osteoblast differentiation. The enhancement of translocation by p204 was observed on Id2 protein by using Western blot analysis of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions from cell lysates (Figure 8, A–C). The cytoplasmic translocation of endogenous Id2 protein was accelerated or delayed in time-dependent manner by Ad-p204 or Ad-p204AS (encoding an antisense RNA against p204 mRNA) infection respectively in the BMP-treated C2C12 cells compared with nontransduced BMP-2–treated C2C12 cells. These results indicated that the level of p204 is important for the translocation of Id2 from nucleus to the cytoplasm in the course of osteogenic differentiation.

Figure 8.

Id2 translocates from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and p204 accelerated its cytoplasmic translocation in BMP-2 induced osteogenesis. (A) Id2 translocates from the nucleus to the cytoplasm during BMP-2–induced osteogenesis, assayed by Western blotting. C2C12 cells cultured in the presence of 300 ng/ml BMP-2 protein for various time points, as indicated, were lysed and cell fractionation of cytoplasmic and nuclei were prepared. The level of Id2 protein was visualized by Western blotting with anti-Id2 antibody. (B) p204 enhances the cytoplasmic translocation of Id2 during BMP-2–induced osteogenesis. C2C12 cells were infected with Ad-p204 virus (MOI 20) and cultured in the presence of BMP-2 protein. The samples were prepared and detected as described in A. (C) Reduction in p204 expression delays the cytoplasmic translocation of Id2 during BMP-2–induced osteogenesis. C2C12 cells were infected with adenovirus encoding p204 antisense RNA (Ad-p204AS, MOI 20) and processed as in described in A.

LMB Blocks the p204-accelerated Cytoplasmic Translocation of Id2 in BMP-2–treated C2C12 Cells

LMB is a potent, specific inhibitor of NES-dependent protein export from the nucleus (Fukuda et al., 1997; Ossareh-Nazari et al., 1997; Kudo et al., 1998). A typical leucine-rich NES (-Leu-X-X-X-Leu-Leu-X-X-X-Leu-X-Leu- (Gerace, 1995; Ambili and Sudhakaran, 1999; Harhaj and Sun, 1999) occurs in the N-terminal region of p204. We examined whether LMB inhibited the cytoplasmic translocation of p204 and Id2 in C2C12 cells undergoing osteogenic differentiation. Stably transfected C2C12 cells were generated that express Id2-Flag and p204. After 24-h culture in the presence of BMP-2, the cells were probed with anti-Flag mAb M2 or anti-p204 polyclonal antibody and FITC-labeled anti-rabbit or rhodamine-labeled anti-mouse secondary antibody. Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy of the stained cells revealed that the majority of Id2-Flag and p204 translocated to the cytoplasm in the BMP-2–treated cells (Figure 9A, a, b, c and d). However, 48 h after the addition of 2 ng/ml leptomycin B to the cells, most of the Id2-Flag and p204 were detected in the nucleus (Figure 9A, e–h). The blockage of cytoplasmic translocation of Id2 by LMB was further confirmed by Western blot analysis of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions from BMP-2–treated C2C12 cells transfected with pCMV-Id2-Flag alone or pCMV-Id2-Flag plus pCMV-204 (Figure 9, B and C).

Figure 9.

The p204-mediated enhancement of the cytoplasmic translocation of Id2 in the course of osteogenesis depends on the NES of p204. (A) LMB inhibits p204-dependent cytoplasmic appearance of Id2 in BMP-2–treated C2C12 cells (immunofluorescence cell staining). C2C12 cells transfected with pId2-Flag and pCMV-p204 were cultured in the presence of 300 ng/ml BMP-2 without (top) or with (bottom) of LMB (2 ng/ml) for 2 d. After fixation and blocking, the cultures were stained with anti-p204 (a and e), anti-Flag (b and f) antibodies, and the nuclei were stained with DAPI (c and g); the overlapping regions of these three signals are shown as “merge” (d and h). (B and C) LMB inhibits p204-dependent cytoplasmic appearance of Id2 in BMP-2–treated C2C12 cells (Western blotting assays). C2C12 cells transfected with pCMV-Id2-FLAG only or together with pCMV-204 were cultured in the presence of BMP-2 without (lanes 2 and 4) or with (lanes 3 and 5) of 2 ng/ml LMB, as indicated. Two days later, the cultures were digested with trypsin/EDTA, collected, replated, and incubated in the media supplemented with MG132, an inhibitor of proteasomes, for a further 12 h. Cell fractionation of cytoplasmic (B) and nuclei (C) were analyzed for Id2-Flag by Western blotting by using anti-Flag antibody. Lamin A and tubulin were used as loading controls. (D) A comparison of the levels of expression of p204 and p204ΔNES in transfected C2C12 cells by Western blotting. C2C12 cells were transfected with either pCMV vector, or an expression plasmid encoding p204 (pCMV-p204) or p204 mutant in which the NES was deleted (pCMV-p204ΔNES), and the protein expressions were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-p204 or anti-tubulin (as internal control) antibodies. (E) p204ΔNES binds to Id2 in vivo, as does p204 (CoIP assay). Cell lysates prepared from C2C12 cells transfected with an expression plasmid encoding Id2-Flag and an expression plasmid encoding either p204 or p204ΔNES, as indicated, were incubated with either anti-Flag (lanes 3 and 4) or control IgG (lanes 5 and 6), followed by protein A-agarose. The immunoprecipitated protein complex and cell extracts (lanes 1 and 2, serve as positive controls) were examined by Western blotting with anti-p204 antibody. (F) Ectopic expression of p204 but not p204ΔNES enhanced the translocation of Id2 in BMP-2-induced osteogenesis. C2C12 cells stably transfected with pCMV vector (Ctrl), pCMV-p204 (p204), or pCMV-p204ΔNES (p204ΔNES) were transfected with pCMV-Id2-Flag, and they were cultured in the presence of 300 ng/ml BMP-2 protein for 3 d. Cells were lysed, and cell fractionation of cytoplasmic and nuclei were prepared. The level of Id2 protein was visualized by Western Blotting with anti-Id2 antibody. For the loading probes, the amounts of lamin A (a nuclear protein) and tubulin (a cytoplasmic protein) were also assayed by Western blotting.

Id2-Flag was translocated to the cytoplasm in the presence of ecotopic expression of p204 (Figure 9, B and C, lane 4); however, this translocation was completely inhibited by LMB (Figure 9, B and C, lane 5). These results are in accord with what we observed in the skeletal muscle differentiation from myocytes (Liu et al., 2002).

NES of p204 Is Required for Its Enhancement of the Cytoplasmic Translocation of Id2 in BMP-2–treated C2C12 Cells

Because LMB blocks the nuclear export of various NES-containing proteins, including p204, we sought to determine whether NES of p204 is specifically needed for the Id2 cytoplasmic translocation during osteogenesis. To do so, we generated control, p204 and p204ΔNES stable lines based on C2C12 cells. As shown in Figure 9D, the levels of expression of p204 and p204ΔNES were similar in the two lines. Furthermore, anti-Flag coimmunoprecipitated similar amounts of p204 and p204ΔNES with Flag-Id2 (Figure 9E). The stable lines were then transfected with pCMV-Id2-Flag and incubated with 300 ng/ml BMP-2 protein. Three days later, MG132 was added to block the proteasomal degradation of Id2-Flag. After further 2-h incubation, nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of cells and total protein of cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Flag M2 mAb. The Id2-Flag occurred in the cytoplasm in the p204 stable line, whereas remained in the nucleus in the p204ΔNES line, similar to that in control line (Figure 9F). The differences in the appearance of nuclear/cytoplasmic Id2-Flag showed the inability of p204ΔNES to enable the cytoplasmic translocation of Id2. This is not due to a lower expression of p204ΔNES in the cells or to an inability of p204ΔNES to bind Id2 (Figure 9, D and E). All of the above-mentioned results indicated that p204 promoted the translocation of Id2 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, and this promotion by p204 depended on the presence of its NES.

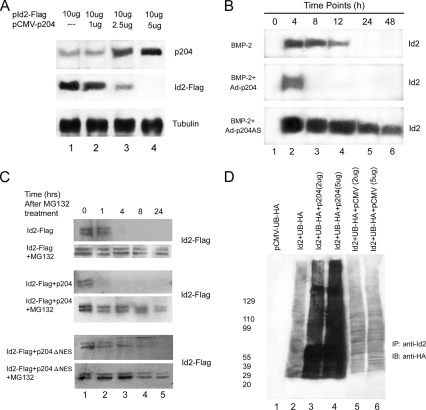

p204 Accelerates the Degradation of Id2 by Ubiquitin–Proteasome Pathway in C2C12 Cells

It was reported previously that p204 promoted a decrease in the level of Id proteins in the course of skeletal muscle and cardical muscle differentiation (Liu et al., 2002; Ding et al., 2006b). Figure 10A also reveals a p204 dosage-dependent decrease in the level of Id2-Flag. At a concentration of 5 μg p204 expression plasmid transfected level, Id2-Flag became undetectable after 36 h in the BMP-2–treated C2C12 cells. These findings prompted us to assay whether p204 accelerates the degradation of the endogenous Id2 protein in C2C12 cells undergoing osteogenic differentiation. Total proteins, from the BMP-2–treated C2C12 cells infected with either Ad-p204 or Ad-p204AS virus at various times, were collected and the level of Id2 protein was visualized by Western blotting with anti-Id2 antibody. Overexpression of p204 enhanced, whereas low level of p204 by antisense approach reduced, the degradation of Id2 in the course of osteogenesis of C2C12 cells induced by BMP-2 (Figure 10B).

Figure 10.

p204 accelerates the degradation of Id2 in the course of osteogenesis. (A) p204 decreases the level of Id2-Flag protein in a dose-dependent manner in BMP-2–treated C2C12 cells. C2C12 cells transfected with a pCMV-Id2-Flag plasmid and various amount of a pCMV-p204 plasmid, as indicated, were cultured in the presence of BMP-2 for 36 h, and cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-p204, anti-Flag, or anti-tubulin (an internal control). (B) p204 accelerates the degradation of endogenous Id2 in BMP-2–treated C2C12 cells. C2C12 cells (BMP-2) and C2C12 infected with either Ad-p204 virus (BMP-2 + Ad-p204) or an adenovirus encoding p204 antisense RNA (BMP-2 + Ad-p204AS) were cultured in the presence of BMP-2 protein. Cell extracts were prepared at indicated times, and the level of Id2 was detected by Western blotting with anti-Id2 antibody. (C) p204, but not p204ΔNES, accelerates the degradation of Id2-Flag by proteasomes. C2C12 cells were transfected as indicated with pCMV-Id2-Flag together with pCMV204 or pCMV204ΔNES. After 24 h, the cultures were digested with trypsin/EDTA, collected, replated, and incubated for a further 24 h. Thereafter (0 h), each culture was supplemented with MG132. The various cultures were harvested and lysed after the indicated times of incubation (0–24 h), and then they were analyzed for Id2-Flag by Western blotting using anti-Flag antibody. (D) p204 dose-dependent increase in the ubiquitination of Id2 in BMP-2–treated C2C12 cells. C2C12 cells were transfected with the mammalian expression plasmids encoding Id2, HA-Ub, p204, or pCMV (as a control). After incubation for 48 h, the cultures were supplemented with MG132 and incubated for a further 6 h. The cells lysates were then immunoprecipitated with anti-Id2 antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody.

The degradation of Id protein occurs through the ubiquitin– proteasome pathway (Bounpheng et al., 1999; Berse et al., 2004). The Western blots in Figure 10C (top) revealed that in C2C12 cells, in which protein synthesis was blocked by CHX first, ectopic Id2-Flag degradation was inhibited by proteasome blocking agent MG132, because the time of detectable Id2-Flag protein changed from 1.0 to 24 h. The degradation of Id2 accelerated by p204 is also blocked by MG132, because the time of detectable Id2-Flag protein changed from 0 to 24 h.

Because our data showed that the translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm of Id proteins is associated with their degradation, and this translocation of Id promoted by p204 depended on the presence of its NES, we deduced that NES of p204 is also required for the degradation of Id protein promoted by p204. Indeed, p204ΔNES did not accelerate the degradation of Id2-Flag; in fact, it diminished this degradation by extending the detectable time from 1 to 8 h (Figure 10C, bottom). This demonstrated that the lack of the NES did impede the promoting of Id2 degradation.

Next, we sought to determine whether the acceleration by p204 of the degradation of Id2 by proteasomes was dependent on ubiquitination. To establish whether p204 can increase the ubiquitination of an Id protein in vivo, we introduced into C2C12 cells plasmids encoding Id2-Flag and HA-tagged ubiquitin without or with various amounts of a plasmid encoding p204. After incubation to allow the expression of the ectopic proteins, we added MG132 to inhibit proteasome activity and to allow the accumulation of polyubiquitinated Id2-Flag. Culture lysates were prepared for an immunoprecipitation assay with anti-Flag antibody, and the immunoprecipitate was analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA probe. The data in Figure 10D revealed a p204 dose-dependent increase in the extent of Id2-Flag polyubiquitination. The level of ubiquitination was low in the control reaction mixtures without p204 (lane 2), higher in the reaction mixture supplemented with 2 μg of p204 plasmid (lane 3), and much higher in that supplemented with 5 μg of p204 plasmid (lane 4). These results revealed that p204 strongly promoted the ubiquitination of Id2 in a dose-dependent manner.

DISCUSSION

Id-1, Id-2, and Id-3 are early targets of osteogenic BMP signaling, and they play important roles in the BMP-induced osteogenic differentiation and bone formation (Ogata et al., 1993); the molecular events involved have not been delineated. Cbfa1, a downstream molecule of BMP signaling, is essential for bone formation (Komori, 2003), and it is a potent inducer of osteogenic differentiation (Zhao et al., 2005). This knowledge led us to hypothesize that Ids might exert their bone development-regulating effect by interacting with Cbfa1 and regulate its activity during osteogenesis. Here, we provide the first evidence demonstrating that 1) Id1, Id2 and Id3, but not Id4, bind to Cbfa1 in vivo and also in the BMP-2–treated C2C12 cells (Figures 2 and 3); and 2) Id2 strongly inhibits the Cbfa1-mediated ALP activity and OCL production (Figure 1). Furthermore, we present comprehensive evidence revealing that the inhibition of the Cbfa1-mediated osteogenesis by Id proteins results from 1) inhibiting the DNA binding activity of Cbfa1 (Figure 4) and 2) inhibiting the expression of Cbfa1 and p204 by Id proteins during the BMP-2–induced osteogenesis of C2C12 cells (Figure 5). These results suggest that Ids directly or indirectly inhibit the Cbfa1 transcription activity and that the osteogenic repression by Ids may occur through these actions. Thus, the targets of inhibition by Id are not only the bHLH transcription factors (e.g., MyoD, myogenin, E12, and E47) (Benezra et al., 1990b; Jen et al., 1992; Perk et al., 2005) in skeletal muscle differentiation but also the non-bHLH proteins, such as Gata4 and Nkx2.5 transcription factors (Ding et al., 2006b) and Cbfa1 (this study) and pRb protein (Iavarone et al., 1994; Ouyang et al., 2002).

Although overexpression of Id proteins inhibited osteogenic differentiation initiated by BMPs (i.e., BMP-9), RNA interference-mediated knockdown of these Id genes also slowed down osteogenic differentiation (Peng et al., 2004), suggesting that a certain level of Id proteins is probably required for the proliferation of mesenchymal cells and critical for fine control of subsequent osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Conversely, BMP-2 enhancement of differentiation of osteoblast seems to require the prior decline of Id level as a prerequisite condition, because at least some differentiation markers such as alkaline phosphatase activity and OCL production are enhanced by Cbfa1 in confluent cells (Ducy, 2000; Lee et al., 2000). However, the precise mechanism of the down-regulation of Id protein level during osteoblast differentiation remains to be elucidated.

The involvement of p204 in osteoblast differentiation was reported previously by our group (Liu et al., 2005). p204 binds to Cbfa1 and acts as a transcriptional coactivator of Cbfa1 in the course of osteogenesis (Liu et al., 2005). In addition, some Id proteins interact with p204 protein in the differentiation of several cell lineages. In the case of skeletal muscle differentiation and cardiac myocyte differentiation, p204 overcomes the inhibition of the differentiation by the Id proteins in these processes (Liu et al., 2002; Ding et al., 2006a). The present study examining the differentiation of C2C12 cells to osteoblasts trigged by BMP proteins reached the same conclusion concerning the function of p204. The Id proteins inhibited transactivation of gene expression by Cbfa1 by binding Cbfa1 and then inhibited the sequence-specific binding of Cbfa1 complex to DNA. p204 negated these inhibitions by Id proteins (Figure 6) by 1) blocking the binding of Id2 to Cbfa1 and enabling Cbfa1 to associate with its target DNA (Figure 7) and 2) promoting translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and accelerating the degradation of Id2 by ubiquitin–proteasome pathway in C2C12 cells undergoing osteogenic differentiation (Figures 8–10).

Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling is an important mechanism for the regulation of Id protein function (Kurooka and Yokota, 2005). Some molecules have been found to regulate Id subcellular localization. For example, Deed et al. (1996) showed that transiently expressed Id3 accumulated in the nucleus when one of the E2A gene products, E47, was coexpressed. Hence, they concluded that E protein acts as a nuclear chaperone for Id proteins. Conversely, Samanta and Kessler (2004) have presented the opposite findings. Their data suggested that Id2 and Id4 would sequester nuclear bHLH proteins to the cytoplasm to promote differentiation of cultured neural progenitors into astrocytes. Furthermore, the subcellular localization of one of the Id protein family members, Id2, has been reported to change from the nucleus to the cytoplasm during neural differentiation into oligodendrocytes (Wang et al., 2001) and myeloid differentiation (Tu et al., 2003). We previously reported that p204 interacted with Id2 and enabled Id2 translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm during the differentiation of skeletal and cardiac muscle cells, and that it overcame the inhibitions mediated by Id proteins (Liu et al., 2002; Ding et al., 2006b). In this study, we found that Id proteins also translocated from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and that ectopic p204 strongly enhanced this process during BMP-2–induced osteogenesis (Figure 8). In addition, the p204-promoted degradation of Id2 through the ubiquitin proteasome pathway is important for the function of p204 in Cbfa1-induced osteogenic differentiation, because proteasome blocking agent MG132 largely abolished p204-mediated enhancement of Cbfa1-induced alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin (data not shown). The p204 enhancement of the translocation of the Id proteins may facilitate the differentiation of C2C12 cells in various ways: 1) by removing the inhibitory Id proteins from the nucleus, it is likely to increase the synergistic transactivation of osteoblast-specific genes by Cbfa1. 2) Consequently, the degradation of the Id proteins in the cytoplasm via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway can be accelerated. Intriguingly, p204 decreased the level of the Id proteins by accelerating their degradation by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, and this strictly depended on the presence of the NES in p204 (Figures 9 and 10). This requirement for the NES in p204 for the acceleration of Id protein degradation was in accord with previous findings that NES was also required for p204 to overcome Id inhibition of skeletal muscle and cardiac myocyte differentiation.

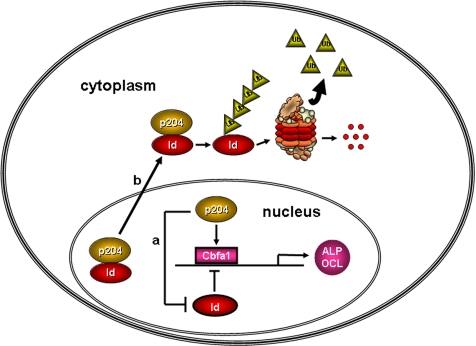

In conclusion, this study provides evidence showing that Id proteins associate with Cbfa1 and inhibit its osteogenic action and that p204 overcomes these inhibitions in C2C12 cells undergoing osteogenic differentiation. As illustrated in Figure 11, Cbfa1, p204, and Id proteins form a regulatory circuit and act in concert to regulate osteoblast differentiation. pRb was found to interact with Cbfa1, and it was required for Cbfa1-mediated osteogenesis (Thomas et al., 2001). pRb is also needed for the association of p204 and Cbfa1 and enhancements of osteogenesis by p204 (Luan et al., 2007). Id2 does not disturb the association of p204 and Cbfa1 (Figure 7B), and same is also true for the association of pRb and Cbfa1 (data not shown), suggesting that p204 and/or pRb bind to Cbfa1 with higher affinity than does Id2. Furthermore, loss of Id-2 partially rescues the Rb−/− phenotype, because the lethality in Rb−/− mice at E14.5 is accompanied by widespread proliferation and defective differentiation and apoptosis in multiple tissues but is absent in Rb−/−, Id-2−/− animals (Lasorella et al., 2000). Thus, the involvements and significance of the interaction network of Cbfa1, p204, Rb, and Ids in regulating osteogenesis remain to be determined.

Figure 11.

A proposed model for explaining the involvements of Id proteins and p204 in regulating Cbfa1 activity in osteogenesis. Cbfa1 is the essential transcription factor that activates the expressions of marker genes of osteogenic differentiation, including ALP and OCL. Id proteins associate with Cbfa1 and inhibit the binding of Cbfa1 to the promoters of target genes. p204 overcomes this inhibition via (a) disturbing the interaction between Id proteins and Cbfa1 and enabling Cbfa1 to bind to DNA, and (b) promoting the translocation of Id proteins from nucleus to the cytoplasm and accelerating the degradation of Id proteins by ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. →, 32 ⊣, and UB indicate stimulation, inhibition, and ubiquitin, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Patricia Ducy (Baylor College of Medicine) for Cbfa1-specific reporter genes, Drs. Kosei Ito and Yoneda Toshiyuki for constructs expressing PeBP2αA (Cbfa1) and its deletion mutants, Dr. Renny Franceschi (University of Michigan) for adenovirus encoding Cbfa1, and Dr. Tong-Chuan He (University of Chicago) for adenovirus encoding BMP-2. This work was aided by National Institutes of Health grants AR-050620, AR-053210, AG-029388, and AR-052022.

Abbreviations used:

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- Cbfa1

core binding factor α-1

- CCD

cleidocranial dysplasia

- CoIP

coimmunoprecipitation

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- GST

glutathione transferase

- Id

inhibitor of differentiation

- LMB

leptomycin B

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- NES

nuclear export signal

- NLS

nuclear localization signal

- OCL

osteocalcin

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- pRb

retinoblastoma protein.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1057) on February 20, 2008.

REFERENCES

- Alway S. E., Degens H., Lowe D. A., Krishnamurthy G. Increased myogenic repressor Id mRNA and protein levels in hindlimb muscles of aged rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2002;282:R411–R422. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00332.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambili M., Sudhakaran P. R. Modulation of neutral matrix metalloproteinases of involuting rat mammary gland by different cations and glycosaminoglycans. J. Cell Biochem. 1999;73:218–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor H., Christ B., Rashid-Doubell F., Kemp C. F., Lang E., Patel K. Follistatin regulates bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP-7) activity to stimulate embryonic muscle growth. Dev. Biol. 2002;243:115–127. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asefa B., Dermott J. M., Kaldis P., Stefanisko K., Garfinkel D. J., Keller J. R. p205, a potential tumor suppressor, inhibits cell proliferation via multiple pathways of cell cycle regulation. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1205–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attisano L., Wrana J. L. Signal transduction by the TGF-beta superfamily. Science. 2002;296:1646–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1071809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benezra R., Davis R. L., Lassar A., Tapscott S., Thayer M., Lockshon D., Weintraub H. Id: a negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Control of terminal myogenic differentiation. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1990a;599:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb42359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benezra R., Davis R. L., Lockshon D., Turner D. L., Weintraub H. The protein Id: a negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell. 1990b;61:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90214-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berse M., Bounpheng M., Huang X., Christy B., Pollmann C., Dubiel W. Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of Id1 and Id3 is mediated by the COP9 signalosome. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;343:361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bounpheng M. A., Dimas J. J., Dodds S. G., Christy B. A. Degradation of Id proteins by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. FASEB J. 1999;13:2257–2264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buitenhuis M., van Deutekom H. W., Verhagen L. P., Castor A., Jacobsen S. E., Lammers J. W., Koenderman L., Coffer P. J. Differential regulation of granulopoiesis by the basic helix-loop-helix transcriptional inhibitors Id1 and Id2. Blood. 2005;105:4272–4281. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choubey D., Snoddy J., Chaturvedi V., Toniato E., Opdenakker G., Thakur A., Samanta H., Engel D. A., Lengyel P. Interferons as gene activators. Indications for repeated gene duplication during the evolution of a cluster of interferon-activatable genes on murine chromosome 1. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:17182–17189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauffy J., Mouchiroud G., Bourette R. P. The interferon-inducible gene, Ifi204, is transcriptionally activated in response to M-CSF, and its expression favors macrophage differentiation in myeloid progenitor cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006;79:173–183. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0205083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deed R. W., Armitage S., Norton J. D. Nuclear localization and regulation of Id protein through an E protein-mediated chaperone mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:23603–23606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.23603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deftos M. L., Huang E., Ojala E. W., Forbush K. A., Bevan M. J. Notch1 signaling promotes the maturation of CD4 and CD8 SP thymocytes. Immunity. 2000;13:73–84. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00009-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps S., Meyer J., Chatterjee G., Wang H., Lengyel P., Roe B. A. The mouse Ifi200 gene cluster: genomic sequence, analysis, and comparison with the human HIN-200 gene cluster. Genomics. 2003;82:34–46. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding B., Liu C. J., Huang Y., Hickey R. P., Yu J., Kong W., Lengyel P. p204 is required for the differentiation of P19 murine embryonal carcinoma cells to beating cardiac myocytes: its expression is activated by the cardiac GATA4, NKX2.5, and TBX5 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2006a;281:14882–14892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding B., Liu C. J., Huang Y., Yu J., Kong W., Lengyel P. p204 protein overcomes the inhibition of the differentiation of P19 murine embryonal carcinoma cells to beating cardiac myocytes by Id proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2006b;281:14893–14906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P. Cbfa 1, a molecular switch in osteoblast biology. Dev. Dyn. 2000;219:461–471. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1074>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P., Schinke T., Karsenty G. The osteoblast: a sophisticated fibroblast under central surveillance. Science. 2000;289:1501–1504. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P., Zhang R., Geoffroy V., Ridall A. L., Karsenty G. Osf2/Cbfa 1, a transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation. Cell. 1997;89:747–754. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliazer S., Spencer J., Ye D., Olson E., Ilaria R. L., Jr Alteration of Mesodermal cell differentiation by EWS/FLI-1, the oncogene implicated in Ewing's sarcoma. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:482–492. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.2.482-492.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M., Asano S., Nakamura T., Adachi M., Yoshida M., Yanagida M., Nishida E. CRM1 is responsible for intracellular transport mediated by the nuclear export signal. Nature. 1997;390:308–311. doi: 10.1038/36894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerace L. Nuclear export signals and the fast track to the cytoplasm. Cell. 1995;82:341–344. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90420-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribaudo G., Riera L., De Andrea M., Landolfo S. The antiproliferative activity of the murine interferon-inducible Ifi 200 proteins depends on the presence of two 200 amino acid domains. FEBS Lett. 1999;456:31–36. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00916-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harhaj E. W., Sun S. C. Regulation of RelA subcellular localization by a putative nuclear export signal and p50. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999;19:7088–7095. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin C. H., Miyazono K., ten Dijke P. TGF-beta signalling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature. 1997;390:465–471. doi: 10.1038/37284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel L., Rolle S., De Andrea M., Azzimonti B., Osello R., Gribaudo G., Gariglio M., Landolfo S. The retinoblastoma protein is an essential mediator that links the interferon-inducible 204 gene to cell-cycle regulation. Oncogene. 2000;19:3598–3608. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollnagel A., Oehlmann V., Heymer J., Ruther U., Nordheim A. Id genes are direct targets of bone morphogenetic protein induction in embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:19838–19845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iavarone A., Garg P., Lasorella A., Hsu J., Israel M. A. The helix-loop-helix protein Id-2 enhances cell proliferation and binds to the retinoblastoma protein. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1270–1284. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.11.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jen Y., Manova K., Benezra R. Each member of the Id gene family exhibits a unique expression pattern in mouse gastrulation and neurogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 1997;208:92–106. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199701)208:1<92::AID-AJA9>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jen Y., Weintraub H., Benezra R. Overexpression of Id protein inhibits the muscle differentiation program: in vivo association of Id with E2A proteins. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1466–1479. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.8.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson M., Mathers J., Dickinson R. J., Mandl M., Keyse S. M. Both nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of the dual specificity phosphatase MKP-3 and its ability to anchor MAP kinase in the cytoplasm are mediated by a conserved nuclear export signal. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:41882–41891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406720200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri T., Yamaguchi A., Komaki M., Abe E., Takahashi N., Ikeda T., Rosen V., Wozney J. M., Fujisawa-Sehara A., Suda T. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 converts the differentiation pathway of C2C12 myoblasts into the osteoblast lineage. J. Cell Biol. 1994;127:1755–1766. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J., Chung H., Yoo Y. G., Kim H., Lee J. Y., Lee M. O., Kong G. Inhibitor of DNA binding 1 activates vascular endothelial growth factor through enhancing the stability and activity of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Mol. Cancer Res. 2007;5:321–329. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T., et al. Requisite roles of Runx2 and Cbfb in skeletal development. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2003;21:193–197. doi: 10.1007/s00774-002-0408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T. Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell. 1997;89:755–764. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo N., Wolff B., Sekimoto T., Schreiner E. P., Yoneda Y., Yanagida M., Horinouchi S., Yoshida M. Leptomycin B inhibition of signal-mediated nuclear export by direct binding to CRM1. Exp. Cell Res. 1998;242:540–547. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu M., et al. Cbfbeta interacts with Runx2 and has a critical role in bone development. Nat. Genet. 2002;32:639–644. doi: 10.1038/ng1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]