Abstract

There has been little research on the effectiveness of different training strategies or the impact of exposure to treatment manuals alone on clinicians' ability to effectively implement empirically supported therapies. Seventy-eight community-based clinicians were assigned to 1 of 3 training conditions: review of a cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) manual only, review of the manual plus access to a CBT training Web site, or review of the manual plus a didactic seminar followed by supervised casework. The primary outcome measure was the clinicians' ability to demonstrate key CBT interventions, as assessed by independent ratings of structured role plays. Statistically significant differences favoring the seminar plus supervision over the manual only condition were found for adherence and skill ratings for 2 of the 3 role plays, with intermediate scores for the Web condition.

In recent years there has been rapid growth in the identification of empirically supported behavioral treatments for a range of substance use disorders (Leshner, 1999; McLellan & McKay, 1998), including contingency management (Griffith, Rowan-Szal, Roark, & Simpson, 2000), family therapy (Stanton & Shadish, 1997), cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT; Irvin, Bowers, Dunn, & Wong, 1999), motivational interviewing (MI; Dunn, Deroo, & Rivara, 2001; Wilk, Jensen, & Havighurst, 1997), manualized drug counseling approaches (Crits-Christoph et al., 1999), and several more. In contrast, there has been comparatively little research on the most effective means by which these treatments may be disseminated to the clinical community. Unlike the pharmaceutical industry—which widely disseminates information about new pharmacological treatments through specialized training sessions, distribution of promotional materials and advertisements, and direct incentives to health care providers—there are few mechanisms for effective dissemination of empirically supported behavioral therapies to clinical practice. Moreover, very little is known regarding the most effective means of doing so.

In contrast, procedures used to train therapists to implement manual-guided therapies in clinical efficacy research are now widely used and generally accepted as standard (Crits-Christoph et al., 1998; Rounsaville, Chevron, Weissman, Prusoff, & Frank, 1986). Therapist training for clinical efficacy trials generally consists of three elements: selection of therapists who are experienced in and committed to the type of treatment they will implement in the trial, an intensive didactic seminar that includes review of the treatment manual with extensive role-playing and practice, and successful completion of at least one closely supervised training case. The latter usually involves certification of the clinician's ability to implement the treatment as defined in the manual through supervisor ratings demonstrating that the clinician attained criterion levels of adherence and skill (DeRubeis, Hollon, Evans, & Bemis, 1982; Shaw, 1984; Waltz, Addis, Koerner, & Jacobson, 1993; Weissman, Rounsaville, & Chevron, 1982). In general, these strategies appear to be successful, in that therapist adherence or skill generally improves during training (or at least achieves acceptable levels; Crits-Christoph et al., 1998), and comparatively little variance in outcome due to therapists' effects is found in studies that use these procedures (Carroll et al., 1998; Crits-Christoph et al., 1998). However, it should be noted that these therapist training strategies have been adopted largely on the basis of face validity and have not been subject to empirical evaluation.

However, these clinician training methods have rarely been applied in efforts to disseminate these treatments to the clinical community. Instead, dissemination has generally been limited to widespread distribution of manuals and/or brief didactic training (e.g., workshops typically of 0.5 to 2 days in duration) without subsequent competency evaluation or provision of supervision. It is not clear that these dissemination methods are sufficient to foster the adoption of key skills by clinicians or that they facilitate clinicians' ability to implement new treatments at adequate levels of fidelity (e.g., comparable with those achieved in the original clinical trials establishing the treatments' efficacy). Moreover, it is not known whether clinician training procedures drawn from clinical trials methodology will be effective or even feasible with real world substance use clinicians. In many community substance abuse treatment settings, (a) clinicians may have minimal training with little or no exposure to the theoretical underpinnings of many empirically supported treatments, (b) many clinicians have not completed bachelor's or master's degrees, (c) clinicians' exposure to and acceptance of empirically supported treatments is variable, and (d) rates of turnover are high (Horgan & Levine, 1999; Institute of Medicine, 1998; McLellan, Belding, McKay, Zanis, & Alterman, 1996).

Only a handful of studies have evaluated strategies for training real world clinicians to use empirically supported treatments. An uncontrolled evaluation of the impact of a 2-day clinical training workshop on 44 participants' knowledge and practice of MI (Miller & Rollnick, 1991) suggested that clinicians' knowledge of MI (assessed through a 15-item, multiple-choice test) increased significantly after attending the workshop, as did their articulation of statements reflecting techniques of MI in response to written vignettes (Rubel, Sobell, & Miller, 2000). In a subsequent uncontrolled evaluation, Miller and Mount (2001) reported that after a 2-day MI training seminar, counselors reported large changes in practice, whereas observational ratings suggested more modest changes in practice behavior. However, training did not have a meaningful impact on client behaviors (e.g., resistance; Miller & Mount, 2001). Morgenstern, Morgan, McCrady, Keller, and Carroll (2001) trained 29 counselors drawn from community drug abuse treatment clinics to deliver CBT. However, no significant differences were found in substance use outcomes when 252 substance abusers were randomly assigned to treatment as usual, high-standardization CBT, or low-standardization CBT as delivered by those clinicians (Morgenstern, Blanchard, Morgan, Labouvie, & Hayaki, 2001). However, it is not clear whether those clinicians attained levels of competence in CBT that would be commensurate with the levels typically achieved in efficacy trials or whether the training in fact enhanced the clinicians' skill or ability to deliver CBT competently.

Several other important questions regarding training real world clinicians to deliver empirically supported therapies have not been addressed. To our knowledge, no study has evaluated the relative effectiveness of different clinician training strategies or whether clinicians' knowledge or ability to implement new approaches changes merely as a result of exposure to a treatment manual. In addition, standard clinician training strategies, consisting of multiple-day workshops followed by supervised clinical work, are relatively expensive and time intensive and thus may be of limited feasibility in training large numbers of clinicians. However, computer-based training approaches may offer a more practical and less expensive method for training larger numbers of substance use clinicians than is feasible through standard face-to-face training strategies. Computer-based training has been demonstrated to be effective in several areas of health care (Anger et al., 2001; Eva, MacDonald, Rodenburg, & Greehr, 2000; Hulsman, Ros, Winnubst, & Bensing, 2002; Issenberg et al., 1999; Todd et al., 1998) but has not yet been evaluated as a strategy to train clinicians in specific manual-guided psychotherapies.

In this report, we describe a dissemination trial comparing the relative efficacy of three methods of training community-based clinicians to implement CBT: (a) exposure to a CBT manual alone, (b) exposure to the manual plus an interactive Web site, or (c) exposure to the manual plus the training strategy routinely used in clinical efficacy trials, that is, a 3-day didactic seminar followed by supervised training cases. We hypothesized that the Web-based training and the seminar plus supervision strategies would be more effective than exposure to the manual alone.

Method

Participants

Participants were 78 clinicians who volunteered to participate in the trial and who provided written informed consent. The participants were required to be currently employed full-time as a clinician treating a predominantly substance-using population. Clinicians were recruited through newsletters and direct contact with clinics. A total of 100 clinicians were initially contacted, 2 were excluded because they were not currently treating substance users, and 20 elected not to participate.

Our intent was to randomize clinicians to training conditions; however, because of practical constraints, 24 of the 78 could not be randomized and were forced into one of the three training conditions. Twelve clinicians were switched from the seminar plus supervision group to the manual only group because they could not attend the training on the days scheduled or obtain permission from their employers to miss work for 3 days. Eight clinicians were forced into the seminar plus supervision or Web group to compensate for those lost to the seminar plus supervision group. Four clinicians were switched from the Web condition and forced into either the seminar plus supervision or manual only group because they did not have adequate access to the Internet or were more unfamiliar with computers than they had indicated at the time of informed consent.

Training Conditions

Manual only

In this condition, clinicians were provided a copy of the CBT manual (Carroll, 1998) after completing baseline assessment. The manual describes the rationale for CBT for drug abuse, with session-by-session guidelines for eight key types of CBT interventions (functional analysis of drug use, coping with craving, managing thoughts about drug use, refusal skills, seemingly irrelevant decisions, problem-solving skills, planning for emergencies, and HIV risk-reduction strategies). The clinicians were asked to spend at least 20 hr reading the manual and practicing CBT.

Manual plus Web-based training

This condition was identical to the manual only condition, but the clinicians also had access to an Internet-based interactive training program. The Web-based program was closely based on the CBT manual and included links to the manual and the eight session topics. In addition, this program involved five types of activities modeled on material typically covered in a face-to-face CBT training seminar. These included the following: (a) a section on “The ABCs of CBT” that reviewed the underlying theoretical foundations of CBT, (b) a section titled “Lessons Learned” that included a number of questions that had been frequently raised about CBT by clinicians in previous training seminars (e.g., “How should I adapt CBT for use with patients with comorbid psychopathology?” and “My patients frequently say they do not experience craving, so how should I introduce this topic to them?”), (c) a “Test Your Knowledge—Basic” section that presented 34 questions about CBT in a multiple-choice format (if the clinician's response was correct, then the program praised the clinician; if the response was incorrect, then the program explained why the response was incorrect, provided the correct response, and referred the clinician to the corresponding page in the manual), (d) a “Test Your Knowledge—Intermediate” section that included several more difficult questions, which were also drawn from the manual, with the same format as above, and (e) a “Try Your Skills” section, which included 12 virtual role plays. Each virtual role play presented a clinical vignette that asked the clinician to demonstrate key CBT skills. The clinician was instructed to write his or her response in a space provided, and the program then presented a sample ideal response and highlighted its features.

Clinicians were asked to spend 20 hr working with the Web site (approximately the same as the didactic seminar). Instructions and assistance were provided regarding the content of the Web site and strategies for going through the material. Clinicians were free to repeat sections of the Web-based training as often as they liked for the duration of the trial. Access to the Web site was controlled through a password system and thus was not accessible to the clinicians assigned to the other conditions.

Manual plus training seminar and supervision

In addition to receiving the CBT manual as described above, clinicians assigned to this condition attended a 3-day didactic CBT training seminar. Modeled on those used in previous clinical trials for CBT (Carroll et al., 1994, 1998, 2004), the seminar included a detailed review of each manual section, videotaped examples of CBT sessions, and role plays of each skill. Following the didactic seminar, the clinicians were asked to practice CBT with their clients over the next 3 months. These practice sessions were audiotaped if their clients provided written informed consent. Practice session tapes were forwarded to three experienced CBT supervisors who evaluated them using the adherence–skill rating system described below. The CBT supervisors then provided up to three 1-hr sessions of supervision via telephone. All 27 clinicians assigned to this condition completed the 3 full days of training; 17 of the 27 sent in audiotapes and completed at least one supervision session.

Assessments

Assessments were completed at baseline, 4 weeks after baseline (e.g., after exposure to the Web site or didactic training for clinicians assigned to those conditions), and 3 months after posttraining assessment (i.e., after completion of supervision for clinicians assigned to the seminar plus supervision condition). The primary outcome measure was the clinicians' ability to demonstrate key CBT techniques via a videotaped role play exercise in which the participants were asked to demonstrate three key CBT interventions: explaining the CBT rationale for treatment and conducting a functional analysis of (a) drug use, (b) coping with craving, and (c) seemingly irrelevant decisions (automatic thoughts). Five experienced clinicians, who had been trained to follow a standardized script with minimal prompting, played the part of a substance-dependent patient in the role plays. The role plays were videotaped for independent evaluation of adherence–skill and took about 1 hr to complete.

The Yale Adherence Competence Scale (YACS; Carroll et al., 2000), a general system for evaluating therapist adherence and skill across several types of manualized substance abuse treatment, was used to evaluate the extent to which the clinicians were able to demonstrate the three CBT skills. The YACS scales have been demonstrated to have good interrater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficients of .85 or greater) and to sharply discriminate CBT from other treatments (Carroll et al., 1998, 2000, 2001). For each item, raters evaluated the clinician on two dimensions using a 7-point, Likert-type scale. First, they rated the extent to which the clinician covered the intervention thoroughly and accurately (adherence); second, they rated the skill with which the clinician delivered the intervention (competence).

Fourteen items drawn from the CBT scale of the YACS were used. For Role Play 1, these included four items associated with introducing the rationale for CBT treatment and functional analyses of substance use. For Role Play 2, four items that evaluated components of skill training in coping with craving were used, and for Role Play 3, six items that assessed skill training associated with evaluating and changing cognitions were used. Four experienced master's-level process raters who were blind to the clinicians' training condition rated the role play tapes. The raters were trained via review of a detailed rating guideline manual, as well as several practice ratings, to achieve consensus.

To assess whether the training methods had an effect on the clinicians' knowledge of CBT theory and technique, we had the participants complete a 55-item, multiple-choice test at baseline and posttraining as a secondary outcome measure. Items on the test were drawn directly from the CBT manual (Carroll, 1998) and addressed both theoretical and practical questions regarding implementation of CBT. Finally, at the 3-month follow-up, the clinicians reported on their use of CBT techniques in their clinical work, as well as their perceptions of barriers to implementing CBT.

Data Analysis

Baseline demographic and training characteristics for the three groups of clinicians were assessed through analyses of variance for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Evaluation of primary (changes in adherence and skill ratings) as well as secondary (knowledge test scores) outcome measures across time were evaluated with 3 (Condition) × 2 (Time) repeated measures analyses of variance. Rather than simply interpreting the omnibus statistic, we specified two a priori contrasts: one comparing the seminar plus supervision with the manual condition and the other comparing the Web condition with the manual only condition. Therefore, in the Results section below, we refer to contrast main effects and Contrast × Time effects, rather than to training condition main effects or Condition × Time effects. Interrater reliability for the YACS ratings was estimated through intraclass correlation coefficients with Shrout and Fleiss's (1979) fixed effects model to estimate reliabilities for independent samples.

Results

The 78 clinicians had a mean age of 45.5 (SD = 9.8) years, and 54% were women and 46% were men. Of the clinicians, 27% were African American, 8% were Hispanic, 61% were Caucasian, and 4% identified their ethnicity as other. A total of 49% of the clinicians had a master's degree, 28% had a bachelor's degree, 16% had an associates degree, and 7% had a high school diploma or a general equivalency diploma. The clinicians reported a mean of 9.0 (SD = 5.9) years of experience treating substance users, and 47% indicated they had a substance abuse problem in the past. The clinicians reported that they carried an average weekly caseload of 21 clients (SD = 14.4) and that a mean of 91% of their caseload comprised substance users. When asked how many hours of formal supervision they received per week, the most frequent response was 1 hr (47% of the sample). The clinicians were also asked to rate their level of familiarity with several approaches to substance use treatment using a 5-point, Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The clinicians indicated that they were most familiar with 12-step or disease-model approaches (M = 4.1, SD = 1.0), followed by interpersonal approaches (M = 2.9, SD = 1.2), motivational approaches (M = 2.7, SD = 1.0), and CBT (M = 2.4, SD = 1.0). The clinicians indicated that they were less familiar with other approaches (mean scores were 2.0 or less for CBT for depression or anxiety disorders, dialectical behavior therapy, and short-term dynamic therapy). Of the sample, 63% reported that they had previous exposure to treatment manuals, and 27% had used computer-aided self-instruction in the past. No statistically significant differences in these baseline characteristics by training condition were found. Moreover, there were no significant differences between the randomized (n = 54) and nonrandomized clinicians (n = 24) on baseline demographic, training, and experience characteristics. There were also no significant differences in baseline adherence and skill ratings or knowledge test scores.

At the posttraining assessment point, all clinicians reported that they had read the CBT manual, and all those assigned to the Web condition reported accessing the Web site at least once. Although the mean number of hours that the clinicians reported reading the manual was about half of what was requested, it did not differ by condition. For the manual only condition, the mean total time that the clinicians reported reading the manual was 9.2 hr (SD = 6.9), for the Web condition, the mean total time was 10.1 hr (SD = 5.7), and for the seminar plus supervision condition, the mean total time was 10.6 hr (SD = 7.3), F(2, 73) = 0.2, p = .82. Clinicians in the Web condition reported spending a mean of 15.7 hr (SD = 7.6) working with the Web site. In the seminar plus supervision condition, all clinicians completed all 3 days of the didactic seminar, for a mean estimate of 20 additional training hr, with an additional 3 hr of telephone supervision. Thus, the mean total hours of training completed was approximately 10 hr for the manual only condition, 26 for the Web condition, and 33 for the seminar plus supervision condition.

Change in Clinicians' Ability to Demonstrate CBT Techniques

As in previous evaluations of the YACS (Carroll et al., 2000), ratings of both adherence and skill levels were found to have good levels of interrater reliability, as the mean intraclass correlation coefficient was .87 for the three sets of adherence ratings and .83 for the three sets of skill ratings. Adherence and skill ratings by training condition and time (pretraining, posttraining, and follow-up–postsupervision) are presented in Table 1. The first set of statistics presented reflects the Contrast × Time effects for pretraining–posttraining comparisons, and the second set refers to the Contrast × Time effects for the posttraining–follow-up comparisons.

Table 1. Role Play Adherence and Skill Scores by Time and Training Condition.

| Variable | Manual only | Manual + Web | Manual + seminar + supervision | Total | Contrast 1 × Time t | Contrast 1 × Time p | Contrast 2 × Time t | Contrast 2 × Time p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role Play 1: Introduction to CBT, functional analysis | ||||||||

| Adherence–pretraining | 1.7 (0.4) | 2.0 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.6) | ||||

| Posttraining | 2.5 (1.2) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.6 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.3) | 2.3 | 0.03 | 0.6 | 0.55 |

| Follow-up | 2.4 (1.1) | 3.3 (1.0) | 4.0 (1.5) | 3.3 (1.4) | 1.1 | 0.28 | 0.6 | 0.56 |

| Skill–pretraining | 1.1 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.3 (0.9) | ||||

| Posttraining | 2.1 (1.6) | 2.7 (1.5) | 3.4 (1.5) | 2.8 (1.6) | 2.4 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.54 |

| Follow-up | 2.0 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.2) | 3.9 (1.8) | 3.0 (1.7) | 0.8 | 0.43 | 0.4 | 0.69 |

| Role Play 2: Coping with craving | ||||||||

| Adherence–pretraining | 2.2 (0.6) | 2.4 (0.9) | 2.4 (0.9) | 2.3 (0.8) | ||||

| Posttraining | 3.0 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.1) | 3.8 (1.2) | 3.3 (1.2) | 1.9 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.89 |

| Follow-up | 2.7 (0.9) | 3.9 (1.3) | 4.0 (1.4) | 3.6 (1.4) | 1.2 | 0.21 | 2.1 | 0.04 |

| Skill–pretraining | 1.6 (0.8) | 2.0 (1.3) | 1.9 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.1) | ||||

| Posttraining | 2.7 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.3) | 3.6 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.4) | 1.6 | 0.11 | 0.2 | 0.83 |

| Follow-up | 2.4 (1.2) | 3.8 (1.5) | 3.8 (1.7) | 3.4 (1.6) | 1.3 | 0.19 | 1.8 | 0.07 |

| Role Play 3: Seemingly irrelevant decisions | ||||||||

| Adherence–pretraining | 2.4 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.3) | ||||

| Posttraining | 3.2 (2.0) | 3.4 (1.6) | 4.2 (1.4) | 3.6 (1.7) | 2.0 | 0.04 | 0.5 | 0.62 |

| Follow-up | 3.2 (1.5) | 4.0 (1.7) | 3.9 (1.8) | 3.7 (1.8) | 0.8 | 0.44 | 0.7 | 0.48 |

| Skill–pretraining | 1.9 (1.6) | 2.3 (1.6) | 1.9 (1.5) | 2.0 (1.6) | ||||

| Posttraining | 2.9 (2.3) | 3.1 (1.8) | 4.0 (1.8) | 3.4 (2.0) | 2.1 | 0.04 | 0.4 | 0.69 |

| Follow-up | 2.8 (1.8) | 3.8 (2.0) | 3.6 (2.2) | 3.4 (2.0) | 0.6 | 0.53 | 0.8 | 0.46 |

Note. Scores range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating better adherence or skill. Values given are means, with standard deviations in parentheses. Sample sizes for the three training conditions (manual, Web, seminar plus supervision, total) are as follows: pretraining = 27, 24, 27, 78; posttraining = 25, 24, 27, 76; follow-up = 21, 22, 24, 67. Degrees of freedom are as follows: pretraining to posttraining (1, 73); posttraining to follow-up analyses (1, 64). Contrast 1 = seminar plus supervision versus manual only; Contrast 2 = Web versus manual only; CBT = cognitive–behavioral therapy.

At the posttreatment assessment, all effects for time were statistically significant, suggesting that the group as a whole improved their performance for all three role plays. No main effects of contrast were statistically significant. For the adherence dimension, evaluation of Contrast × Time effects for the two primary contrasts (seminar plus supervision vs. manual only, Web vs. manual only) suggested that the clinicians assigned to the seminar plus supervision condition made significantly greater gains than those assigned to the manual only condition for two of the three role plays. Clinicians assigned to the Web condition tended to have higher adherence ratings compared with the manual only condition, but differences were not statistically significant. Cohen's d (Cohen, 1988) for the seminar plus supervision versus manual only comparison across the three role plays was 0.85, 0.73, and 0.50, respectively (mean effect size = 0.69). Effect sizes for the Web versus manual only comparison were 0.50, 0.20 and 0.10, respectively (mean effect size = 0.27).

For the skill dimension, clinicians assigned to the seminar plus supervision condition had significantly higher posttraining skills scores than those assigned to the manual only condition for two of the three role plays. Effect sizes for the skill dimension across the three role plays were 0.71, 0.64, and 0.48, respectively (mean effect size = 0.61). Clinicians assigned to the Web condition tended to have higher mean skill scores than those assigned to the manual only condition, but these were not significantly different at the posttraining assessment point. Effect sizes for the Web versus manual only condition for the skill dimension were 0.37, 0.21, and 0.09, respectively (mean effect size = 0.22).

Posttraining to Follow-Up

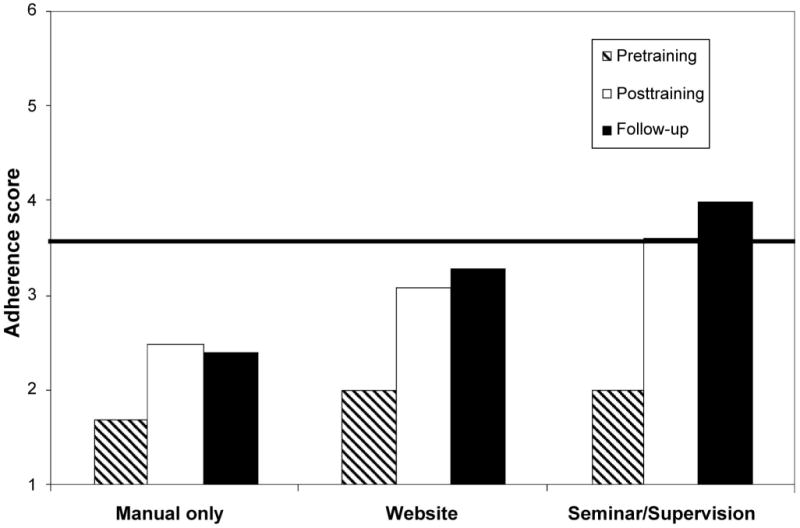

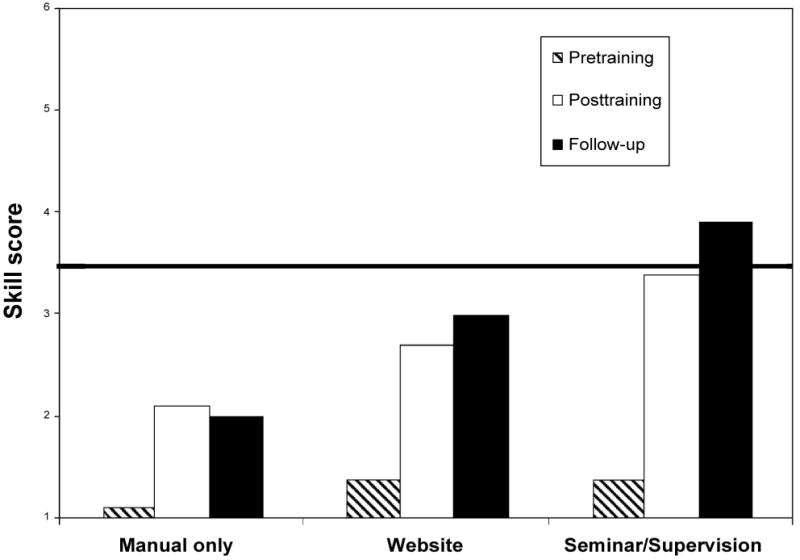

At the follow-up evaluation (which reflected postsupervision ratings for those assigned to the seminar plus supervision condition), both contrasts were significant for the first two role plays: introduction to CBT, adherence t(64) = 4.1, p = .001, skill t(64) = 4.2, p = .001; coping with craving, adherence t(64) = 3.2, p = .001, skill t(64) = 3.2, p = .001; seemingly irrelevant decisions, adherence t(64) = 1.8, p = .08, skill t(64) = 1.8, p = .07. This suggests that participants assigned to the seminar plus supervision and the Web conditions had significantly higher ratings than those assigned to the manual only condition. However, the Contrast × Time effects were not statistically significant, suggesting that clinicians in both these conditions retained the significant gains seen at the posttraining assessment point, but there was no further differential change by training condition. As illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, ratings for those assigned to the seminar plus supervision and Web conditions improved slightly during the follow-up–supervision period and decreased somewhat for those assigned to the manual only condition. Effect sizes for the seminar plus supervision versus manual only comparison for the adherence dimension at follow-up were 1.4, 1.4, and 0.47, respectively (mean effect size = 1.1); for the skill dimension they were 1.3, 1.2, and 0.44, respectively (mean effect size = 0.98). Effect sizes for the Web versus manual only comparison for the adherence dimension at follow-up were 0.81, 1.3, and 0.53, respectively (mean effect size = 0.88); for the skill dimension they were 0.81, 1.2, and 0.56, respectively (mean effect size = 0.86).

Figure 1.

Role Play 1 (presenting the cognitive–behavioral therapy rationale and functional analysis): adherence scores by time and training condition. Scores range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating better adherence. The solid horizontal line indicates the criterion level that is typical for certification in clinical efficacy trials.

Figure 2.

Role Play 1 (presenting the cognitive–behavioral therapy rationale and functional analysis): skill scores by time and training condition. Scores range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating better skill. The solid horizontal line indicates the criterion level that is typical for certification in clinical efficacy trials.

Because not all participants assigned to the seminar plus supervision condition submitted practice tapes and participated in the supervision sessions, exploratory analyses were conducted to evaluate whether those clinicians who participated in supervision had higher adherence or skill ratings than those who did not. For all role plays and for both the adherence and skill ratings, there were significant effects for time (indicating increases in adherence and skill ratings) and group (indicating a main effect for group, with higher scores overall for those who participated in supervision), but there were no significant Group × Time interactions.

Finally, we evaluated the three conditions in practical (e.g., clinically significant) terms, that is, the effectiveness of the three conditions in terms of proportions of number of clinicians successfully trained. We used the criterion of final ratings of 3.5 or higher on two of the three role plays for both adherence and skill scores. This standard was selected because it is the criterion used to certify clinicians in previous clinical efficacy trials that have evaluated CBT (Carroll et al., 1998, 2000, 2004) and is similar to the redline level concept from the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Project (Addis, 1997; Shaw, 1984). The percentage of clinicians meeting this criterion was 15% for the manual only condition, 48% for the Web condition, and 54% for the seminar plus supervision condition, χ2(2, N = 67) = 7.7, p = .02.

Randomized Versus Nonrandomized Clinicians

To evaluate whether the results reported above reflected possible bias associated with the inclusion of nonrandomized clinicians, the primary analyses were repeated, including only the 54 clinicians who were randomized to one of the three training conditions. Although the mean scores did not change appreciably, the posttraining Contrast × Time effects were no longer statistically significant. For the full sample, mean posttraining effect sizes (which compared the seminar plus supervision condition with the manual only condition and averaged across the three role plays, Cohen's d; Cohen, 1988) were 0.69 for the adherence ratings and 0.61 for the skill ratings. For the randomized sample, effect sizes were 0.67 and 0.69, respectively. At follow-up, mean effect sizes were 1.1 for adherence and 0.98 for skill ratings for the full sample and 1.2 and 1.2, respectively, for the randomized sample.

Effect of Clinician Characteristics on Acquisition of Skills

Exploratory analyses that evaluated the effect of the clinicians' education level (master's vs. bachelor's degree or less), years of experience, and recovery status (self-identified as having had a substance abuse problem vs. not) on outcomes suggested the following: First, there were no significant main effects or interactions by training condition of level of education or years of experience on adherence–skill ratings. Second, there was some evidence that traditional face-to-face training was particularly helpful to the recovering subgroup. That is, there were several statistically significant Group × Time interactions on adherence and skill scores, suggesting greater improvement in the recovering group when assigned to the seminar plus supervision condition compared with the manual only condition (Time × Contrast effects were statistically significant for both adherence and skill scores for Role Plays 1 and 2). At baseline, the recovering group reported having significantly higher caseloads, F(1, 73) = 4.9, p = .03, being more familiar with disease model and 12-step approaches, F(1, 73) = 19.6, p = .001, and receiving less than 1 hr of supervision each week, F(1, 73) = 8.4, p = .03, compared with the clinicians who did not identify themselves as having had a substance use problem in the past. However, because education level was significantly related to self-reported recovery status, χ2(1, N = 78) = 12.7, p < .001, educational level may have some influence on these findings.

Changes in Clinicians' Knowledge of CBT

Changes from baseline to posttraining on the CBT Knowledge Test are presented in Table 2. There was an overall effect for time, t(74) = 5.1, p < .01, suggesting that scores improved for the group as a whole over time. However, there were no significant Contrast × Time effects (effect sizes for the Web vs. manual and seminar plus supervision contrasts were 0.30 and 0.33, respectively). Those assigned to the seminar plus supervision condition had the largest increase in scores (4.3 points). Participants with a master's degree had significantly greater increases across time than participants who had a bachelor's degree or less (at posttraining, scores were 42.1 for those with a master's degree vs. 36.9 for those with a bachelor's degree). However, there was no significant interaction of Training Condition × Educational Level on knowledge scores. By recovery status, there was an interaction of Training Condition × Recovery Status, in which clinicians who self-identified as recovering made somewhat greater gains if they were assigned to the Web or seminar plus supervision conditions, F(1, 68) = 3.2, p = .08. There were no significant main effects or interactions of years of clinical experience on knowledge scores.

Table 2. CBT Knowledge Test Scores by Time and Training Condition.

| Score | Manual only

(n = 25) |

Manual + Web

(n = 24) |

Manual + seminar + supervision

(n = 27) |

Contrast 1 × Time t | Contrast 1 × Time p | Contrast 2 × Time t | Contrast 2 × Time p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretraining | 36.6 (4.8) | 36.3 (5.6) | 36.0 (4.9) | ||||

| Posttraining | 38.3 (6.3) | 40.2 (7.1) | 40.4 (4.9) | −1.8 | 0.08 | −1.4 | 0.16 |

Note. Scores range from 1 to 55, with higher scores indicating more correct responses. Values given are means, with standard deviations in parentheses. Degrees of freedom are (1, 73). CBT = cognitive–behavioral therapy; Contrast 1 = seminar plus supervision versus manual only; Contrast 2 = Web versus manual only.

When only those clinicians who had been randomized to a training condition were included in the analysis, the posttraining mean scores for the randomized subsample were not appreciably different from those of the full sample (manual only M = 38.5, Web site M = 40.2, seminar plus supervision M = 41.2), and effect sizes (comparing the seminar plus supervision condition with the manual only condition) were comparable (0.33 for the full sample and 0.44 for the randomized subsample). The CBT Knowledge Test and the adherence and skill ratings were moderately correlated. Pearson's r correlations for the pretraining CBT Knowledge Test and the pretraining mean adherence and skill ratings were .38 and .41, respectively (both p < .01). At posttraining, correlations were .31 and .32, respectively (both p < .01).

Satisfaction and Use of CBT Techniques

The clinicians' report of their use of CBT techniques in their clinical work was assessed via self-reports at follow-up and are presented in Table 3. Overall, there were few statistically significant between-condition differences, but the general pattern suggested somewhat higher reported use of CBT in their clinical work and greater satisfaction with the CBT manual among the seminar plus supervision and Web conditions compared with the manual only condition. Moreover, ratings by participants assigned to the manual only condition suggested that they perceived more barriers to using CBT in their clinical work (e.g., seeing CBT as too long, too structured, or not compatible with their style) compared with clinicians assigned to the other conditions.

Table 3. Self-Reported Use of CBT and Perceived Barriers to Using CBT by Training Condition.

| Variable | Manual only

(n = 21) |

Manual + Web

(n = 22) |

Manual + seminar + supervision

(n = 24) |

Contrast 1

(t) |

Contrast 1

(p) |

Contrast 2

(t) |

Contrast 2

(p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How many patients introduced to CBT in past 3 months | 13.3 (12.1) | 18.7 (31.5) | 18.6 (17.3) | 0.8 | 0.40 | 0.8 | 0.41 |

| How often introduce CBT concepts to clientsa | 3.4 (1.0) | 3.7 (0.8) | 3.5 (0.7) | 0.7 | 0.47 | 1.2 | 0.23 |

| Effectiveness of CBT manual as a clinical toola | 3.7 (0.9) | 3.9 (0.6) | 4.3 (0.5) | 0.1 | 0.95 | 0.6 | 0.57 |

| How relevant is CBT to clinical worka | 3.5 (1.1) | 3.7 (0.9) | 3.8 (1.0) | 0.9 | 0.40 | 0.6 | 0.58 |

| Influence of CBT on clinical worka | 3.3 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.6) | 4.4 (0.5) | 1.1 | 0.28 | 0.5 | 0.63 |

| Barriers to implementing CBTa | |||||||

| 12 session duration too short | 2.1 (1.3) | 2.3 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.5 | 0.13 | 0.5 | 0.61 |

| CBT not compatible with my style | 2.0 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.2 (0.6) | 2.8 | 0.01 | 1.1 | 0.26 |

| CBT too structured | 2.0 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.9) | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.9 | 0.07 | 1.3 | 0.20 |

| CBT not useful with patients in crisis | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.3 (1.2) | 1.7 (0.8) | 2.3 | 0.02 | 0.1 | 0.88 |

Note. Values given are means, with standard deviations in parentheses. Degrees of freedom are (1, 64). CBT = cognitive–behavioral therapy; Contrast 1 = seminar plus supervision versus manual only; Contrast 2 = Web versus manual only.

Scores range from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely).

Discussion

This dissemination trial of three strategies for training real world counselors to use CBT suggested that the clinicians' ability to implement CBT, as assessed by independent ratings of adherence and skill for three key CBT interventions, was significantly higher—for two of the three areas assessed—for those who participated in the seminar plus supervision condition compared with those assigned to the manual only condition, with intermediate ratings for the Web condition. Ratings for the clinicians assigned to the seminar plus supervision or Web conditions remained stable or improved during the follow-up–supervision period, whereas those for the clinicians assigned to the manual only condition tended to stay the same or decrease slightly. The mean effect size for the seminar plus supervision versus manual only condition comparisons was consistent with a large effect, whereas the average effect size for the Web versus manual only condition contrasts was inconsistent with a medium size effect. In addition, the seminar plus supervision condition was associated with significantly more clinicians reaching criterion levels for adequate fidelity than those assigned to the manual only condition. Evaluations of the clinicians' change in knowledge of CBT and self-reports of their implementation of CBT in clinical practice suggested more modest changes that tended not to be significantly different across conditions.

Taken together, these findings have important implications for the dissemination of CBT and other empirically supported treatments to the clinical community. This was to our knowledge the first trial that explicitly evaluated whether clinicians' ability to implement empirically supported therapies changed after merely reading a manual. Although our findings suggest that some improvement occurred in the manual only condition, such changes tended to be smaller and more short lived than those of clinicians who participated either in traditional seminar-based training or Web-based training.

Although offering a didactic seminar plus supervised practice is the gold standard for training clinicians to participate in clinical efficacy studies, these methods have tended to be accepted at face value and have rarely been subject to empirical evaluation. Our data suggest that these training methods are reasonably effective, at least for this group of drug abuse counselors. There was some indication that face-to-face training may be particularly important for clinicians who self-identify as having had a substance abuse problem in the past, as this subgroup tended to improve their adherence and skill ratings much more when they were assigned to the seminar plus supervision condition. As suggested by our data and others (Project MATCH Research Group, 1998), substance use clinicians who have had a substance abuse problem themselves are more likely to be familiar and comfortable with traditional disease model counseling approaches and may thus have less familiarity with or receptiveness to CBT. Face-to-face training—with the opportunity to see videotaped examples, practice skills, ask questions, and receive supervision—may be essential if such individuals are to be persuaded to learn and effectively implement new approaches.

These findings also point to the potential promise of computer-based training as a strategy for training larger numbers of clinicians to learn novel approaches. Although our findings suggest that the traditional didactic seminar plus supervision strategy was more effective than merely providing clinicians with a training manual, providing 3 days of training and several hours of supervision was expensive and time consuming for these busy clinicians. It was also unfeasible for a number of them who could not arrange to take 3 days off work. Although the Web-based training developed for this evaluation was fairly rudimentary (in that it was highly text based and did not include multimedia features such as videotaped vignettes of applications of CBT), these data suggest it was somewhat more effective than the manual alone, although effects were not statistically significant. More highly sophisticated computer-based training programs that can recreate more of the experience of face-to-face training may prove to be a promising method of encouraging more clinicians to learn and use empirically supported therapies.

Finally, although this group of clinicians, especially those who participated in more intensive training methods, improved their ability to demonstrate key CBT skills, those increases were fairly modest. Adherence and skill ratings approached adequate levels consistent with those of more selected groups of doctoral-level therapists that participated in previous clinical trials using the same instrument and raters (Carroll et al., 1998, 2000) for only 54% of the group assigned to the seminar plus supervision condition, 48% of those assigned to the Web condition, and 15% of those assigned to the manual only condition. To further enhance community-based clinicians' ability to use and implement CBT, it may be necessary to use longer or more intensive training and supervision to achieve levels of fidelity that are comparable with those achieved in the clinical efficacy trials.

It should be also noted that although the three conditions differed with respect to modality of training, they also differed with respect to intensity in terms of total number of hours. Thus, an alternative explanation of our findings is that more intensive training may account for greater increases in adherence and skill levels seen for the seminar plus supervision condition relative to the manual only condition. Repeated contact with trainees and the provision of consultation and support over a more extended period of time, rather than one-shot approaches, may be needed to produce larger and durable training effects. Another approach worthy of further evaluation would be a training to criterion approach in which clinicians would receive feedback, coaching, and supervision until they met minimum standards for certification, with ongoing monitoring and refresher training.

This trial has several limitations. First, because of the practical constraints of working with real world counselors, it was not possible to randomize all clinicians because several of the participants could not attend the scheduled training seminars and others had limited computer skills or inadequate computer access. Nevertheless, we were able to randomize 69% of the sample. The randomized and nonrandomized clinicians were not significantly different on baseline demographic variables or pretraining adherence–skill ratings. Moreover, supplemental analyses that included only the randomized subgroup indicated comparable effect sizes and a similar pattern of changes as for the full sample. This suggests that, other than the reduction in power, conclusions based on the data from the randomized subsample would not be greatly different from those reported here. In a study of outcomes for outpatient versus inpatient substance abuse treatment, in which practical considerations sharply limit the extent to which randomization is possible for all participants, McKay, Alterman, McLellan, and Snider (1995) reported few differences in treatment outcomes for randomized versus nonrandomized substance users. This suggests that in effectiveness studies such as these, in which the ability to fully randomize participants is limited by differences in the practical demands associated with the various experimental conditions, conclusions based on nonrandomized groups may be similar to those based on randomized samples. Second, this study was conceived solely as a dissemination trial. Thus, although the findings presented here address the effects of these training methods on clinicians' ability to demonstrate CBT techniques, they do not address the extent to which the training provided affected actual patient outcomes. Although Miller and Mount's (2001) uncontrolled study suggested that the training seminar was associated with change in clinician within-session practice behavior but not client in-session resistance, others have suggested that clinicians who demonstrate levels of fidelity comparable with levels seen in benchmark efficacy trials have comparable outcomes (Henggeler, Melton, Brondino, Scherer, & Hanley, 1997). Third, although little change appeared to be associated with the manual only condition, it should be noted that the study did not include a no-manual condition with which to compare outcomes for this approach. Finally, these findings reflect effects of training on real world clinicians who volunteered to participate in an evaluation of training strategies, and it is not known whether these findings generalize to other, possibly less motivated, groups of clinicians or to other types of treatment. This group of clinicians was, however, very similar in terms of demographic, educational, and experience characteristics to those participating in large-scale effectiveness trials (Ball et al., 2002) and is also representative of substance use clinicians in the state of Connecticut (Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, 2002).

Nevertheless, as the first systematic trial of widely used strategies to train clinicians to learn and implement manual-guided therapies, these findings are significant in several respects. First, they underscore that real world clinicians are eager to learn empirically supported therapies, as we had little difficulty recruiting or retaining sufficient numbers of clinicians. Second, our findings suggest that merely making manuals available to clinicians has little enduring effect on clinicians' ability to implement new treatments. This has important implications for present efforts to disseminate new treatments. Our findings suggest that face-to-face training followed by direct supervision and credentialing may be essential for effective technology transfer and raise questions regarding whether practitioners should feel competent (from an ethical perspective) to administer an empirically supported treatment on the basis of reading a manual alone. Third, findings suggest that Web-based training has some promise in this context and should be pursued as a strategy for making training in empirically supported psychotherapies more widely available. Finally, the findings suggest that standard strategies used to train clinicians in clinical trials can be effective for community-based clinicians and may be pursued as a strategy for future dissemination trials and bridging the gap between research and practice.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grants R44 DA 11352, P50 DA09241, K05 DA00089 (to Bruce J. Rounsaville), and K05-DA00457 (to Kathleen M. Carroll). We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Tami Frankforter, Charla Nich, Lisa Fenton, Joanne Corvino, Theresa Babuscio, Karen Hunkele, Brian Kiluk, Monica Canning-Ball, Lance Barnes, John Hamilton, and the clinicians who participated in the trial.

References

- Addis ME. Evaluating the treatment manual as a means of disseminating empirically validated psychotherapies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1997;4:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Anger WK, Rohlman DS, Kirkpatrick J, Reed RR, Lundeen CA, Eckerman DA. cTRAIN: A computer-aided training system developed in SuperCard for teaching skills using behavioral education principles. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2001;33:277–281. doi: 10.3758/bf03195377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Bachrach K, DeCarlo J, Farentinos C, Keen M, McSherry T, et al. Characteristics of community clinicians trained to provide manual-guided therapy for substance abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:309–318. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM. A Cognitive–behavioral approach: Treating cocaine addiction. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Connors GJ, Cooney NL, DiClemente CC, Donovan DM, Longabaugh RL, et al. Internal validity of Project MATCH treatments: Discriminability and integrity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:290–303. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Fenton LR, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Shi J, et al. Efficacy of disulfiram and cognitive–behavioral therapy in cocaine-dependent outpatients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:264–272. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Sifry R, Frankforter T, Nuro KF, Ball SA, et al. A general system for evaluating therapist adherence and competence in psychotherapy research in the addictions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;57:225–238. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Gordon LT, Nich C, Jatlow PM, Bisighini RM, et al. Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for ambulatory cocaine abusers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:177–197. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Steinberg K, Nich C, Roffman RA, Kadden RM, Miller M, et al. Treatment process, alliance, and outcome in brief versus extended treatments for marijuana dependence. 2001 doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03047.x. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Blaine JD, Frank A, Luborsky L, Onken LS, et al. Psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence: Results of the National Institute on Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:495–502. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.6.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Chittams J, Barber JP, Beck AT, Frank A, et al. Training in cognitive, supportive-expressive, and drug counseling therapies for cocaine dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:484–492. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. Connecticut's addiction counselors. Hartford, CT: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Evans MD, Bemis KM. Can psychotherapies for depression be discriminated? A systematic evaluation of cognitive therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:744–756. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.5.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn C, Deroo I, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: A systematic review. Addiction. 2001;96:1725–1742. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961217253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eva KW, MacDonald RD, Rodenburg D, Greehr G. Maintaining the characteristics of effective clinical teachers in computer assisted learning environments. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2000;5:233–246. doi: 10.1023/A:1009881605391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JD, Rowan-Szal GA, Roark RR, Simpson DD. Contingency management in outpatient methadone treatment: A meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58:55–66. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Melton GB, Brondino MJ, Scherer DG, Hanley JH. Multisystemic therapy with violent and chronic juvenile offenders and their families: The role of treatment fidelity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:821–833. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan CM, Levine HJ. The substance abuse treatment system: What does it look like and whom does it serve? In: Lamb S, Greenlick MR, McCarty D, editors. Bridging the gap between practice and research: Forging partnerships with community-based drug and alcohol treatment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. pp. 186–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsman RL, Ros WJG, Winnubst JAM, Bensing JM. The effectiveness of a computer-assisted instruction programme on communication skills of medical specialists in oncology. Medical Education. 2002;36:125–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Bridging the gap between practice and research: Forging partnerships with community-based drug and alcohol treatment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin JE, Bowers CA, Dunn ME, Wong MC. Efficacy of relapse prevention: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:563–570. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Hart IR, Mayer JW, Felner JM, Petrusa ER, et al. Simulation technology for health care professional skills training and assessment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:861–866. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshner AI. Science-based views of drug addiction and its treatment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1314–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, Snider EC. Effects of random versus nonrandom assignment in a comparison of inpatient and day hospital rehabilitation for male alcoholics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:70–78. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Belding MA, McKay JR, Zanis D, Alterman AI. Can the outcomes research literature inform the search for quality indicators in substance abuse treatment? In: Edmunds M, Frank RG, Hogan M, McCarty D, Robinson-Beale R, Weisner C, editors. Managing managed care: Quality improvement in behavioral health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. pp. 271–311. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, McKay JR. The treatment of addiction: What can research offer practice? In: Lamb S, Greenlick MR, McCarty D, editors. Bridging the gap between practice and research: Forging partnerships with community based drug and alcohol treatment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. pp. 147–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Mount KA. A small study of training in motivational interviewing: Does one workshop change clinician and client behavior? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2001;29:457–471. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Blanchard KA, Morgan TJ, Labouvie E, Hayaki J. Testing the effectiveness of cognitive–behavioral treatment for substance abuse in a community setting: Within treatment and posttreatment findings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:1007–1017. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Morgan TJ, McCrady BS, Keller DS, Carroll KM. Manual-guided cognitive–behavioral therapy training: A promising method for disseminating empirically supported substance abuse treatments to the practice community. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Therapist effects in three treatments for alcohol problems. Psychotherapy Research. 1998;8:455–474. [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Chevron E, Weissman MM, Prusoff BA, Frank E. Training therapists to perform interpersonal psychotherapy in clinical trials. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1986;27:364–371. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(86)90012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubel EC, Sobell LC, Miller WR. Do continuing workshops improve participants skills? Effects of a motivational interviewing workshop on substance-abuse counselors' skills and knowledge. Behavior Therapist. 2000;23:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BF. Specification of the training and evaluation of cognitive therapists for outcome studies. In: Williams JBW, Spitzer RL, editors. Psychotherapy research: Where are we and where should we go? New York: Guilford Press; 1984. pp. 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:420–429. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton MD, Shadish WR. Outcome, attrition, and family-couples treatment for drug abuse: A meta-analysis and review of the controlled, comparative studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;122:170–191. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd KH, Braslow A, Brennan RT, Lowery DW, Cox RJ, Lipscomb LE, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of video self-instruction versus traditional CPR training. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1998;31:364–369. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70348-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz J, Addis ME, Koerner K, Jacobson NS. Testing the integrity of a psychotherapy protocol: Assessment of adherence and competence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:620–630. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.4.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron E. Training psychotherapists to participate in psychotherapy outcome studies. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1982;139:1442–1446. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.11.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk AI, Jensen NM, Havighurst TC. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials addressing brief interventions in heavy alcohol drinkers. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12:274–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.012005274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]