Abstract

Gating kinetics and underlying thermodynamic properties of human ether-a-go-go-related gene (HERG) K+ channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes were studied using protocols able to yield true steady-state kinetic parameters. Channel mutants lacking the initial 16 residues of the amino terminus before the conserved eag/PAS region showed significant positive shifts in activation voltage dependence associated with a reduction of zg values and a less negative ΔGo, indicating a deletion-induced displacement of the equilibrium toward the closed state. Conversely, a negative shift and an increased ΔGo, indicative of closed-state destabilization, were observed in channels lacking the amino-terminal proximal domain. Furthermore, accelerated activation and deactivation kinetics were observed in these constructs when differences in driving force were considered, suggesting that the presence of distal and proximal amino-terminal segments contributes in wild-type channels to specific chemical interactions that raise the energy barrier for activation. Steady-state characteristics of some single point mutants in the intracellular loop linking S4 and S5 helices revealed a striking parallelism between the effects of these mutations and those of the amino-terminal modifications. Our data indicate that in addition to the recognized influence of the initial amino-terminus region on HERG deactivation, this cytoplasmic region also affects activation behavior. The data also suggest that not only a slow movement of the voltage sensor itself but also delaying its functional coupling to the activation gate by some cytoplasmic structures possibly acting on the S4-S5 loop may contribute to the atypically slow gating of HERG.

INTRODUCTION

The human ether-a-go-go-related gene (HERG) encodes a potassium channel that mediates the cardiac repolarizing current IKr (1,2). ERG potassium channels play a key role setting the electrical behavior of a variety of cell types (3–10). Malfunction of HERG currents is responsible for the type 2 long QT syndrome (1,11–16), a clinical disorder characterized by prolongation of the QT interval on the electrocardiogram associated with an increased risk of life-threatening arrhythmia (11,17,18). The critical determinant of HERG physiological roles is its atypical kinetic behavior, characterized by slow activation kinetics and a very fast voltage-dependent inactivation process on depolarization. In addition, a fast recovery from inactivation followed by a much slower deactivation process take place on repolarization, helping to maintain the channels open before closing at negative potentials. This makes HERG operate as an inward rectifier because little outward current passes through it during depolarization, although an increased current is induced during repolarization, even though the driving force for potassium decreases at negative voltages under physiological conditions (19–23).

It is important to understand the activation and deactivation gating kinetics to properly interpret the contribution of HERG channels to cell function. In this case, use of equilibrium and/or steady-state conditions to obtain voltage dependencies and for derivation of thermodynamic parameters is of primary interest for at least two reasons: 1), it provides a model- and researcher-independent way to quantify the kinetic characteristics, and 2), it allows for an accurate comparison of these characteristics among different channel constructs that could help to understand the impact of a given residue and/or protein domain on channel functionality. However, disparate V½ values for activation of different HERG mutants, sometimes differing by several tens of millivolts, have been reported using so-called fully activated or steady-state activation curves (2,23–33). As previously emphasized (22,34,35), the slow rates of HERG activation and deactivation at voltages around the V½ values of the activation curves make the use of very long pulses necessary to reach a complete steady state. On the other hand, such slowness will shift the voltage dependence of activation, making impossible an accurate comparison of two channel mutants showing different activation time courses, unless the steady-state condition is fulfilled.

As for other voltage-dependent potassium channels, the main determinant of HERG voltage sensitivity is the occurrence of conformational changes in the voltage-sensing domain contributed by the S1-S4 transmembrane segments (29–33,36–38). However, it has been also recognized that other protein regions can contribute to the gating machinery and influence the activation and deactivation transitions. Thus, an interaction of the N-terminus with the S4-S5 linker has been proposed as a determinant of HERG slow deactivation (19,23,39), although direct proof of such a physical coupling between these structures is still lacking. It has also been proposed that an interaction of the initial eag domain with the channel core could be involved in facilitation of opening after elimination of the proximal domain in the amino terminus of HERG (34). Electrostatic interactions between a small section of the proximal domain (close to the S1 helix) and the gating machinery (possibly at the level of the S4-S5 loop), have been proposed as a determinant of the modulatory effects of this domain on gating (33). Finally, a role of the S4-S5 linker coupling the voltage sensor movement to the activation gate of HERG has also been recently recognized (40).

In this study we characterized the thermodinamic and kinetic gating properties of HERG channel mutants either lacking specific domains of the amino terminus or carrying several point mutations in the S4-S5 loop, using protocols designed to yield kinetic parameters under true steady-state conditions. The results were also compared with those obtained with channels combining structural alterations in both regions. Our findings emphasize the key role of these cytoplasmic structures modulating HERG gating properties and indicate that not only the movement of the voltage sensor itself but also the S4-S5 linker and the N-terminal regions act as important determinants of activation and deactivation voltage-dependent properties.

METHODS

Plasmids and preparation of cRNA

The original plasmid containing the cDNA for the HERG channel (psP64A+-HERG) was a generous gift of Dr. E. Wanke (University of Milan, Italy). For in vitro cRNA synthesis, the HERG constructs cloned in the psP64A+ vector were linearized, and capped cRNA was synthesized from the linear cDNA templates by standard methods using SP6 RNA polymerase as described previously (41,42).

Generation of HERG channel mutants

Procedures for generation of the Δ138-373 and Δ2-370 mutants have been detailed elsewhere (34,43). To construct the mutant Δ2-16, a forward polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primer was synthesized to introduce a HindIII restriction site and an ATG codon, plus 27 bp of HERG coding sequence corresponding to amino acids 17–26 (5′-GGAAGCTTTCAGGATGACCATCATCCGCAAGTTTGAGGGCCAGAG). The reverse primer was designed to cover the coding sequence of HERG corresponding to amino acids 400–407 (5′-CCTTGAAGGGGCTGTAATGCAGGAT). The resulting PCR product was digested with HindIII and BstEII, gel purified, and ligated into HindIII/BstEII-digested wild-type HERG in the psP64A+ expression vector. For the Δ2-135 mutant, a forward primer containing the HindIII site, an ATG, and the coding sequence corresponding to amino acids 136–145 (5′-GGAAGCTTTCAGGATGGACATGGTGGGGTCCCCGGCTCATGACACC) was used in PCR with the same reverse primer as above covering amino acids 400–407 of the HERG sequence. The PCR product generated was digested with HindIII/BstEII, and the purified fragment was used to replace the corresponding HindIII/BstEII wild-type fragment in the psP64A+-HERG construct.

The point mutants D540C, R541H, R541A, Y542C, Y545C, and G546C were created by site-directed mutagenesis using the PCR-based overlap extension method as previously described (34,43,44). The final PCR fragments were digested with BstEII/BglII and ligated into BstEII/BglII-digested wild-type HERG in the psP64A+ vector. To combine S4-S5 loop mutations and the Δ2-370 amino-terminal deletion, BstEII/BglII restriction fragments from each of the S4-S5 channel mutants were used to replace the corresponding segments in HERG deleted construct Δ2-370. All constructs were sequenced to confirm the mutations and to ensure the absence of introduced errors.

Expression of HERG channel variants and current recording conditions in Xenopus laevis oocytes

Procedures for frog anesthesia and surgery, obtaining oocytes, and microinjection have been detailed elsewhere (34,41–43,45). Oocytes were maintained in OR-2 medium (in mM: NaCl 82.5, KCl 2, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2, Na2HPO4 1, HEPES 10, at pH 7.5). Cytoplasmic microinjections were performed with 30–50 nl of in vitro synthesized cRNA per oocyte. HERG currents were studied in manually defolliculated oocytes. Recordings were systematically obtained in high-K+ OR-2 medium in which 50 mM KCl replaced an equivalent amount of NaCl to maximize tail current magnitude at negative repolarizing potentials. A continuous perfusion of the cells at 1–5 ml/min was used to minimize the possible influence of K+ variations during long test pulses. The amount of injected cRNA was calibrated to maintain inward current levels in the 1–6 μA range at repolarizing voltages around −100 mV to ensure proper voltage control. Functional expression was typically assessed 2–3 days after microinjection. Recordings were made at room temperature using the two-electrode voltage-clamp method as described previously (34,42,43,45). Membrane potential was typically clamped at −80 mV except for constructs showing a left shift in voltage dependence of activation, in which a −100/−110 mV basal voltage was used to compensate for this shift. When indicated, a holding potential of 0/+20 mV was also used to maintain the channels open to obtain true steady-state activation data. Ionic currents sampled at 1 KHz were elicited using the voltage protocols indicated in the graphs.

Kinetic parameters of activation and deactivation were obtained as previously described (34,42). The voltage dependence of activation was assessed by standard tail current analysis using depolarization pulses of variable amplitude. For slowly deactivating channels, the size of the peak inward tail currents gives a reasonable estimate for the fraction of channels activated (and inactivated) at the end of the depolarization. Alternatively, and for very rapidly deactivating constructs, fitting the relaxation of the tail currents and extrapolating the magnitude of the decaying current to the moment the depolarizing pulse ended were used to determine the amount of current passing through channels opened on depolarization without influence of rapid inactivation (2,42). To take into account the possible influence of the inactivation recovery process on peak tail current or extrapolated current magnitudes, the integral of the completely deactivated tail currents was also used to estimate the voltage dependence of these channels. In all cases, very small variations of the half-maximum activation voltage (V½) were observed by any of the three alternative procedures, never reaching differences above ±3 mV. Tail current magnitudes normalized to maximum were fitted with a Boltzmann function to estimate the V½ and equivalent gating charge (zg):

|

where V is the test potential, and F, R, and T are Faraday constant, gas constant, and absolute temperature, respectively. The activation data were also fitted with a second Boltzmann function of the form:

|

where ΔGo is the work done at 0 mV. Although both equations are equivalent, from the last expression, the effect of every mutation on changes in the chemical potential (ΔGo) and electrostatic potential (−VzgF) that drives activation can be obtained. The time course of voltage-dependent activation was studied using an indirect envelope-of-tail-currents protocols, varying the duration of depolarizing prepulses, and following the magnitude of the tail currents on repolarization. The time necessary to reach a half-maximal tail current magnitude was used to compare the speed of activation of the different channels.

The rates of deactivation were determined from negative-amplitude biexponential fits to the decaying phase of tail currents using a function of the form:

|

where τf and τs are the time constants of fast and slow components, Af and As are the relative amplitudes of these components, and C is a constant. In this case, the first cursor of the fitting window was advanced to the end of the initial hook because of the recovery of inactivation.

Statistics

Data values given in the text and in figures with error bars represent the mean ± SE for the number of indicated cells. Comparisons between data groups were at first performed by parametric Student's unpaired t-test (two-tailed) or ANOVA. Where nonhomogeneous variances (as evidenced after Bartlett's test) were obtained, alternate Welch's test assuming Gaussian populations with unequal SD and nonparametric Wilcoxon or Mann-Whitney tests, which do not make any assumption about the scatter of the data, were also used to evaluate significance of mean differences between cell populations. In all cases, p-values <0.05 were considered indicative of statistical significance.

RESULTS

Influence of specific amino-terminal deletions on steady-state activation voltage dependence of HERG channels

Exhaustive mutagenesis and kinetic studies using HERG channels modified in the initial protein segment located between residues 1 and 135, which includes the conserved eag/PAS domain, have been used to emphasize the crucial role of this region in setting the slow closing kinetics of the channel (19–21). However, the possible impact of these structural alterations on activation gating has not been similarly assessed.

To investigate the possible influence of the initial amino-terminal domains on HERG activation properties, we generated two channel constructs lacking either the first 135 amino acids including the previously characterized PAS structure located between residues 16 and 135 (mutant Δ2-135) or only the initial 16 amino acids (mutant Δ2-16) that remained disordered in the crystalline structure (21). The characteristics of these channels were compared with those of mutant Δ2-370 in which not only the initial portion but most of the amino terminus has been deleted, and with Δ138-373 channels lacking only the protein segment corresponding to the proximal domain. In all cases, these constructs were expressed in Xenopus oocytes, and currents were measured using a two-electrode voltage clamp. To elucidate the voltage dependence of activation, depolarization pulses to different potentials were applied, and tail currents were recorded on repolarization (Fig. 1). Because of the rapid inactivation exhibited by HERG, the ionic currents during depolarizing pulses used to activate the channels are rather small, and their kinetics are obscured by superposition of activation and inactivation transitions over a wide range (2,22,24,29,30,34). Big deactivating tail currents can be measured after the return to negative voltages following the depolarizing steps that trigger the activation (and inactivation) of the channels. Such currents, inward at the negative potentials and ionic conditions used here, result from fast inactivation removal, followed by a decay caused by a relatively slow channel closing. Analysis of the magnitude of these tail currents as a function of previous depolarization voltage can be used to generate I versus V curves from which the voltage dependence of channel activation can be obtained (Fig. 2). For wild-type channels, Boltzmann fits (see Methods) to the normalized tail current data obtained in response to depolarization pulses of 1 s duration from a holding potential of −80 mV yielded V½, zg, and ΔGo values of −21.9 ± 0.55 mV, 3.23 ± 0.06, and −1.65 ± 0.05 kcal/mol, respectively (n = 25). However, for such channels as wild-type HERG characterized by very slow activation/deactivation kinetics, no steady state will be achieved unless much longer pulses are applied. Thus, at a holding potential of −80 mV the position of the Boltzmann curve along the voltage axis was strongly shifted toward more negative values by increasing the duration of the depolarizing step from 1 to 10 s. This modified the aforementioned kinetic parameters to −42.6 ± 0.72 mV, 4.16 ± 0.09, and −4.08 ± 0.05 kcal/mol (n = 5). On the other hand, and perhaps more important, when 10 s preconditioning test pulses were applied to wild-type channels from two holding voltages (−80 and 0 mV), at which closed and open channels are expected, respectively, the activation curves were still separated by nearly 30 mV. This demonstrates that for wild-type channels test depolarizations of up to 10 s are not long enough to reach a true equilibrium because if a steady-state condition is attained during the depolarizing test pulse, the current magnitudes and the position of the derived I/V curves must be independent of the previous channel state (holding voltage) or the test pulse duration. Therefore, only fractional or isochronal but not real steady-state parameters can be derived from these data. Subsequently, V½ values under steady-state conditions and the charge and free-energy parameters for all channel constructs were obtained from Boltzmann fits to activation curves either coming from coincident curves at two extreme holding voltages and long 10-s depolarizations or from the extrapolated mean of such still noncoincident curves (Fig. 2). This guaranteed that I/V curves were exclusively a function of test pulse characteristics, regardless of the previous (open or closed) state of the channels. As previously shown, this extrapolated value marks the end of the I/V curve trend to converge as a result of increased test pulse duration from any holding voltage, yielding a reasonable estimation of the true steady-state V½ (22,34,35). As an example of the impact caused by steady-state deviations on the derived kinetic parameters, the −1.65 kcal/mol ΔGo value obtained for wild-type HERG using 1-s depolarization pulses from a holding potential of −80 mV is increased to −4.08 kcal/mol with 10-s conditioning pulses, a value still deviated from the −5.70 kcal/mol under steady-state conditions.

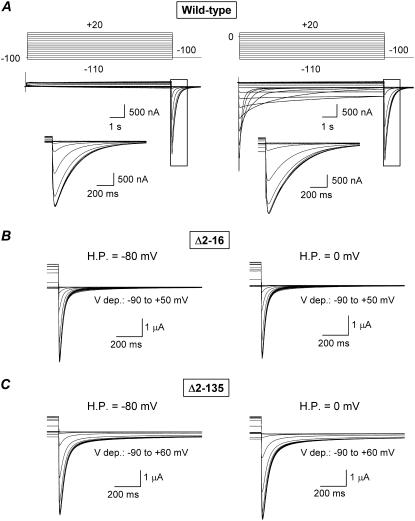

FIGURE 1.

Effect of deleting the initial region of the amino terminus on HERG currents recorded with protocols designed to yield steady-state activation voltage dependence. (A) Membrane currents obtained from an oocyte expressing wild-type HERG channels after 10-s depolarizations to different voltages as indicated at the top. Holding potentials of −100 mV to keep the channels fully closed (left) and 0 mV to hold them fully open (right) were used. Currents at the end of the depolarizing steps and the tail currents at −100 mV corresponding to the boxed area are shown expanded in the insets. (B and C) Membrane currents in oocytes expressing HERG constructs lacking the initial 16 amino acids (Δ2-16) or the initial region of the amino terminus including the eag/PAS domain (Δ2-135). Tail currents at −80 (B) or −100 mV (C) were obtained after 10-s prepulses between −90 and +50/+60 mV in 10-mV increments. Only the end of the depolarizing steps and the tail currents are shown for simplicity. Holding potentials (H.P.) of −80 (left traces) and 0 mV (right traces) were used as indicated on the graphs.

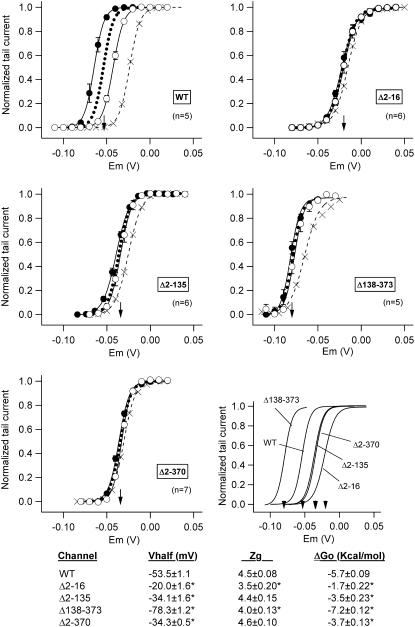

FIGURE 2.

Effect of amino-terminal deletions on HERG activation voltage dependence under steady-state conditions. Fractional activation curves for wild-type (WT) and the indicated channel variants were obtained from tail current data obtained as detailed in Fig. 1. Open and filled symbols correspond to data obtained in response to 10-s prepulses from hyperpolarized (−80 to −110 mV) and depolarized (0 to +40 mV) holding voltages, respectively. The continuous lines correspond to Boltzmann curves that best fitted the data. The dotted lines represent the deduced position of the activation curves under steady-state conditions, obtained by horizontally averaging the values of the two lines coming from both holding voltages to prevent alterations in the sigmoidal shape of the traces. The V½ values for the steady-state curves are indicated by arrows in the graphs. Activation curves obtained with prepulses of 1-s duration (crosses) from hyperpolarized holding potentials are also shown for comparison. Steady-state curves for the different constructs are shown superimposed (lower right panel). Kinetic and thermodynamic parameters obtained under steady-state conditions for the different channel variants are summarized at the bottom. *p < 0.05 versus wild-type.

It is important to note that the observed variations in kinetic behavior after short (1-s) and long (10-s) conditioning pulses are not a consequence of a secondary process (e.g., recruitment of silent channels or long-term open probability variations as a result of a slow and uncontrolled cellular process) taking place during long depolarizations because 1), for the same conditioning pulse, opposite I/V curve shifts are obtained as a function of the holding potential, and 2), the same amount of current was obtained at saturating positive voltages for the 1- and 10-s-derived I/V curves. Thus, with those constructs showing relatively small displacements of the 10-s I/V curve and almost coincident 10-s-derived curves at two holding potentials (i.e., Δ2-16, Δ2-135, Δ2-370, R541A and Y545C channels), only nonsignificant variations (<5%) in the maximal amount of current were observed when I/V curves obtained using 10-s conditioning pulses were compared with those obtained in the same oocytes using 1-s depolarizing steps. Analogously, maximal current levels amounting to 4.0 ± 1.3% (n = 7) and 2.3 ± 1.6% (n = 6) of those recorded in response to 1-s depolarizing steps were obtained when 10-s depolarizations were applied to wild-type and G546C channels, respectively. Therefore, the short- and long-term derived parameters originate from the different kinetic situations affecting the same channel population. On the other hand, this kinetic behavior is inherent to HERG itself and not related to the oocyte expression system or to contamination of recordings with endogenous chloride currents during long voltage steps because analogous deviations are observed in HEK293 cells expressing wild-type HERG channels (35).

The steady-state values of V½, zg, and ΔGo of the different constructs are summarized at the bottom of Fig. 2. It can be observed that a negative shift in V½ from −53.5 ± 1.1 mV for wild-type (n = 5) to −78.3 ± 1.2 mV for Δ138-373 (n = 5) is induced by deletion of the proximal domain, but the voltage dependence of activation is shifted in the opposite direction in channels lacking the initial amino acids of the protein. Thus, mutants Δ2-16, Δ2-135, and Δ2-370 showed V½ values of −20.0 ± 1.6 (n = 6), −34.1 ± 1.6 (n = 6), and −34.3 ± 0.5 mV (n = 7), respectively. Interestingly, a V½ value equivalent to that obtained here under steady-state conditions has been previously reported for wild-type HERG using 30-s depolarization steps (23). The data in Fig. 2 also indicate a significant reduction of zg for Δ2-16 and Δ138-373 compared with wild-type channels. On the other hand, whereas a larger chemical potential drives the opening of the proximal-domain-deleted Δ138-373 channels (ΔGo = −7.2 ± 0.12 kcal/mol as compared with −5.7 ± 0.09 kcal/mol for wild-type), a less negative ΔGo is observed for those constructs deleted in the initial region of the amino terminus, regardless of the presence or absence of the proximal domain (−1.7 ± 0.22, −3.5 ± 0.23, and −3.7 ± 0.13 kcal/mol for Δ2-16, Δ2-135, and Δ2-370 mutants). These data suggest that the presence of the proximal domain tends to stabilize the closed state(s) of HERG, whereas the initial segment of the protein tends to stabilize the group of open states relative to the group of closed ones.

Effect of amino-terminal deletions on HERG activation rates

As indicated above for the activation voltage dependencies, direct measurement of HERG activation rates during depolarization steps is not possible because of overlapping of rapid inactivation and channel opening. Therefore, we studied the time course of voltage-dependent activation using an envelope-of-tails protocol in which the duration of a depolarizing prepulse is varied at each potential, and the magnitude of the tail current peak at a constant repolarizing voltage is measured at the end of every conditioning prepulse. Because of the presence of several preopen closed states, the HERG activation time course shows a sigmoidal shape (24,30,33,45). Therefore, we estimated the rate of activation at a given voltage from the time necessary to attain half-maximum tail current magnitude at every depolarization potential (34,35). The data obtained with the different constructs carrying deletions in the amino terminus are compared with those from wild-type channels in Fig. 3. Plots of activation rates as a function of depolarization membrane potential showed a similar slope for all channel types through the tested range. With a value of 0 mV taken as a reference, relatively similar activation kinetics was observed for channels carrying deletions in the first 135 amino acids, as compared with those of the wild-type channels. Thus, the 143 ± 8.6 ms (n = 6) necessary to reach the half-maximal tail amplitude of the wild-type channels at this voltage were either slightly increased to 211 ± 21 ms (n = 6) and 213 ± 11 ms (n = 7), or slightly decreased to 100 ± 9 ms (n = 6) for Δ2-16, Δ2-135, and Δ2-370 channels, respectively. However, consistent with previous results (34), a marked acceleration in activation kinetics of around fivefold (t½ = 28 ± 1 ms (n = 6)) was obtained with Δ138-373 channels selectively deleted in the proximal domain.

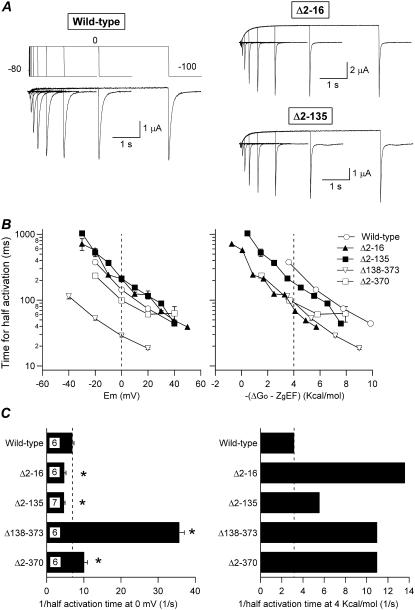

FIGURE 3.

Effect of amino-terminal deletions on HERG activation rates. (A) Comparison of channel activation rates at 0 mV in oocytes expressing wild-type HERG and Δ2-16 or Δ2-135 constructs. The time course of voltage-dependent activation was studied by varying the duration of a depolarizing pulse to 0 mV following the voltage protocol shown on top of the wild-type current traces. Current traces corresponding to depolarization steps of 0, 20, 40, 80, 160, 320, 640, 1280, 2560, and 5120 ms are shown superimposed. (B) Dependence of activation rates on depolarization membrane potential (left) or total potential driving force (right) for channels carrying different deletions in the amino terminus. The magnitude of the peak tail current on repolarization was determined from recordings as shown in panel A after varying the duration of depolarization prepulses to different potentials. The time necessary to attain half-maximum tail current magnitude is plotted versus either depolarization potential (left) or total energy driving activation (i.e., −(ΔGo − zgEF), right). ΔGo and zg values were derived as detailed in Methods from steady-state activation voltage-dependence curves of the different channels. Data from Δ138-373 and Δ2-370 deleted channels are also shown for comparison. (C) Summary of activation rates at 0 mV (left) and 4 kcal/mol of electrochemical driving force (right). The speed of activation of the different constructs is compared as measured by the inverse value of the half activation time. The t½ values at 0 mV or those graphically determined at 4 kcal/mol from the crossing of the activation graphs and the 4 kcal/mol line in B (right panel) were used. *p < 0.05 versus wild-type.

The analysis of the mutation effects on activation rates is complicated by the shifts in voltage dependence of steady-state activation (V½) and by the alterations in the effective number of gating charges moving across the membrane electric field (zg). Because this would change the total activation driving force (chemical plus electrostatic potential) for every channel mutant at a given voltage, we also plotted the activation rates for the different constructs versus the total energy driving activation (i.e., −(ΔGo − zgEF)) (30,31). These plots showed similar slopes along the tested range. Interestingly, when compensated for the differences in driving force, the activation kinetics of all mutants appeared clearly accelerated as compared with the wild-type channel. If a level of 4 kcal/mol is taken as a reference, this acceleration corresponded to almost 2-fold for the Δ2-135 mutant, 3.5-fold for Δ138-373 and Δ2-370 channels, and 4.3-fold for the Δ2-16 construct.

These results indicate that although the mutations cause shifts in the steady-state voltage dependence of activation that could affect opening rates at submaximal activation potentials, the changes observed in the rates are not secondary to those shifts. They also suggest that 1), not only the N-terminal region corresponding to the proximal domain (33,34,45) but also the initial part of the amino terminus may contribute to set the activation characteristics of HERG, and 2), the amino-terminal structures exert rate-limiting control of gating transitions during the activation process. Interestingly, our corrected data show that a facilitation of activation (faster activation rate) is induced not only by deletion of the proximal domain (Δ138-373) that causes a shift of the equilibrium toward the open state (more negative ΔGo) but also in the mutants lacking the initial amino-terminal region (Δ2-16, Δ2-135, and Δ2-370) in which ΔGo is shifted by the deletions to less negative values. This demonstrates the utility of this approach to separate alterations in the transition energy of the gating process from changes in energy difference between, or relative stability of, the closed and open states.

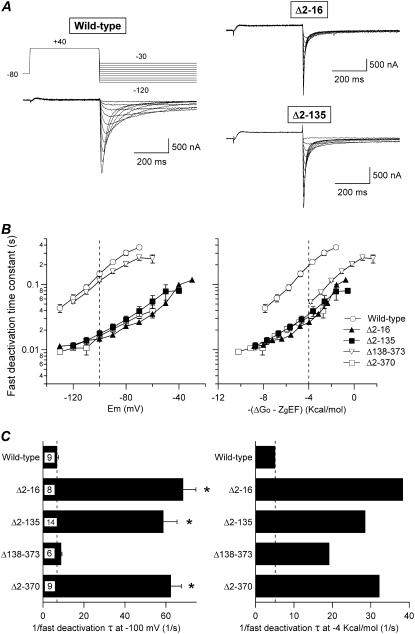

Effect of amino-terminal deletions on HERG deactivation kinetics

Fitting the decaying phase of tail currents to a biexponential function at different potentials after a fixed depolarization pulse allows the estimation of the voltage dependence of deactivation kinetics. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the time constant of the fast deactivation component that accounts for most of the current amplitude at negative voltages (21,30,34) became strongly reduced in all channel mutants lacking the initial 16-amino-acid segment. Thus, values of 14.5 ± 1.3, 14.4 ± 2.0, and 16.0 ± 1.3 ms (n = 8–14) were obtained for Δ2-16, Δ2-135, and Δ2-370 compared with 145 ± 14 (n = 9) for wild-type channels at −100 mV, a potential well below the threshold for activation of all constructs. However, a value closer to that of wild-type was observed with the proximal domain-deleted Δ138-373 mutant (113 ± 4 ms, n = 6). These results emphasized the key role of the amino-terminus initial segments on regulation of HERG deactivation properties (34). Interestingly, although this reduction in deactivation time constants remained almost unaltered for all the initial segment-deleted constructs, once differences in total potential energy are considered, a 3.75-fold acceleration of closing was also observed for Δ138-373 channels at equivalent driving forces.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of amino-terminal deletions on HERG deactivation rates. (A) Comparison of channel deactivation in wild-type channels and Δ2-16 or Δ2-135 constructs carrying deletions in the eag/PAS region. Families of currents were obtained during steps to potentials ranging from −120 to −30 mV after depolarization pulses to open (and inactivate) the channels, as indicated at the top of the wild-type current traces. Only the first part of the 4-s repolarization steps used to follow the complete decay of the tail currents is shown for clarity. (B) Dependence of deactivation rates on repolarization membrane potential (left) or total potential driving force (right) for channels carrying different deletions in the amino terminus. Deactivation time constants were quantified by fitting a double exponential to the decaying portion of the tails as described in Methods. Only the magnitude of the deactivation time constant corresponding to the fast decaying current major component at negative voltages is shown. Data from Δ138-373 and Δ2-370 deleted channels are also shown for comparison. (C) Summary of deactivation rates at −100 mV (left) and −4 kcal/mol of electrochemical driving force (right). The speed of deactivation of the different constructs are compared as reflected by the inverse value of the deactivation time constant. Values obtained at −100 mV or those graphically determined at −4 kcal/mol from the deactivation graphs and the −4 kcal/mol line crossing in B (right panel) were used. *p < 0.05 versus wild-type.

Influence of S4-S5 loop mutations on steady-state activation voltage dependence of HERG channels

The interaction of the initial HERG region with the S4-S5 linker has been proposed as a determinant of slow deactivation (19,23,39). The aforementioned modifications of HERG activation properties, observed when the initial segment of the amino terminus is eliminated, prompted us to check if mutations in the S4-S5 loop could similarly affect activation parameters. For this purpose, we generated several single-point mutations between residues 540 and 546 of this linker that were characterized using procedures analogous to those described above for the amino-terminal constructs. Additionally, some of these mutations were combined with amino-terminal deletions to check for possible additive effects on gating (see below).

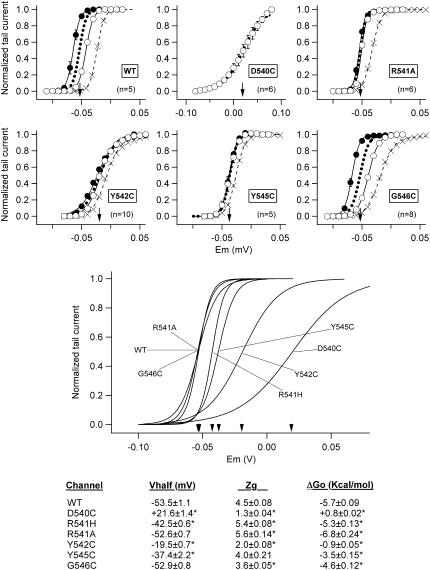

Data regarding the activation voltage dependence of D540C, R541A, Y542C, Y545C, and G546C mutants are summarized in Figs. 5 and 6. Results of channels in which arginine 541 was replaced by histidine (R541H) are also shown. This change introduced a histidine that is highly conserved in the same position of several Kv channels, including some members of the eag family, and whose mutation to arginine has been reported to compensate for the alterations in activation gating caused by N-terminal deletions of the rat eag channel (46). The position of the steady-state Boltzmann curves along the x-axis remained the same in cells expressing R541A and G546C channels as compared with wild-type, whereas a small rightward shift of around 10 mV was observed with R541H and Y545C mutants (Fig. 6). However, strong displacements to more depolarized potentials were obtained after introducing cysteines in residues 540 and 542. In this case the V½ values were modified from the −53.5 mV of the wild-type to 21.6 ± 1.4 (n = 6) and −19.5 ± 0.7 mV (n = 10) in D540C and Y542C channels, respectively. These huge modifications in steady-state voltage dependencies were also accompanied by a substantial reduction in the slope of the I/V curves that lowered the zg value from 4.5 in the wild-type to 1.3 ± 0.04 and 2.0 ± 0.08 in D540C and Y542C channels. As a result of these alterations, the chemical potential for activation ΔGo was raised from the control −5.7 kcal/mol to 0.8 ± 0.02 and −0.9 ± 0.05 kcal/mol, respectively. These data indicate that without an applied membrane field (e.g., at 0 mV) the tendency of the channels to open is nearly abolished (Y542C) or slightly reversed (D540C) by the mutations.

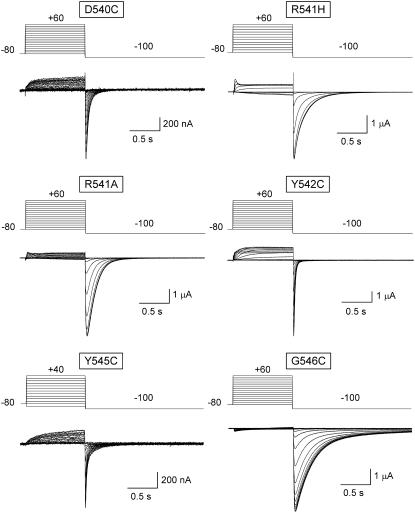

FIGURE 5.

Effect of S4-S5 loop single point mutations on HERG currents obtained at different depolarization voltages. Families of currents were obtained with the protocols indicated on top of the traces, using 1-s depolarizations to test potentials between −80 and +60 mV in 10-mV steps from a holding potential of −80 mV. Note the differences in the tail-current kinetics of the different mutants on repolarization to −100 mV.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of S4-S5 loop mutations on HERG activation voltage dependence under steady-state conditions. Fractional activation curves for wild-type (WT) and the indicated mutants were obtained from tail-current data obtained as detailed in Fig. 2. Open and filled symbols correspond to data obtained after 10-s depolarization prepulses from hyperpolarized and depolarized holding voltages at which channels are maintained closed and open, respectively. Fully superimposable graphs after short 1-s depolarizations from both holding potentials are illustrated in the case of the very fast activating and deactivating D540C channels. The continuous lines correspond to Boltzmann curves that best fit the data, and the dotted lines represent the deduced position of the activation curves under steady-state conditions obtained as a mean of those corresponding to both holding voltages. The V½ values for the steady-state curves are indicated by arrows in the graphs. Activation curves obtained with prepulses of 1-s duration (crosses) from hyperpolarized holding potentials are also shown for comparison. Steady-state curves for the different constructs are shown superimposed (lower panel). Kinetic and thermodynamic parameters obtained under steady-state conditions for the different channels are summarized at the bottom. *p < 0.05 versus wild-type.

Effect of S4-S5 loop mutations on HERG activation rates

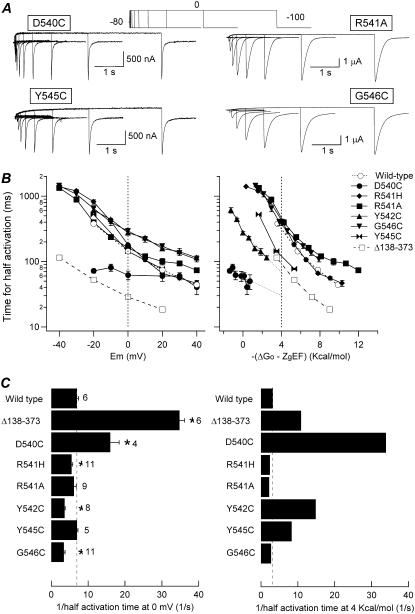

To characterize the time dependence of the activation process, an envelope-of-tails protocol (see above) was applied to mutants in the S4-S5 linker. As shown in Fig. 7, plots of half-activation-time variation as a function of depolarization potential showed similar slopes for the S4-S5 mutants as compared with wild-type and proximal-domain-deleted channels. However, there was a notable exception to this trend in the case of the D540C mutant, which showed only a small variation of t½ values at different depolarizing voltages. Comparison of activation rates at 0 mV indicated very little change in the kinetics of opening after modification of residues 541 and 545, but almost twofold slower rates were observed with Y542C and G546C mutants. Interestingly, considerably faster rates were obtained with D540C channels at 0 mV, although this difference tended to disappear at positive voltages because of the reduced voltage dependence of the activation rates exhibited by this mutant. Indeed, the acceleration of channel opening induced by mutation of residue 540 became more pronounced when activation rates were compensated for differences in driving force. Nevertheless, the flat energetic profile of the D540C mutant complicated the performance of a rigorous comparison at the more positive levels of energy driving activation. With the 4 kcal/mol level taken as a reference, we also observed a slightly slowed activation rate with R541A, R541H, and G546C channels. Finally, the Y542C and Y545C mutants exhibited 4.6- and 2.6-fold faster activation rates than wild-type at equivalent driving force. Altogether, these results indicate that not only deactivation gating (19) but also voltage-dependent activation properties can be affected by structural alterations in the S4-S5 linker (39).

FIGURE 7.

Effect of S4-S5 loop mutations on HERG activation rates. (A) Comparison of channel activation rates at 0 mV in oocytes expressing different S4-S5 loop single-point mutants. Representative families of currents recorded using an envelope-of-tails protocol as detailed in Fig. 3 are shown. (B) Dependence of activation rates on depolarization membrane potential (left) or total potential driving force (right) for the different mutants. The time necessary to attain half-maximum tail-current magnitude is plotted against depolarization potential (left) or total energy driving activation (i.e., −(ΔGo − zgEF); right). Data from either wild-type channels or those deleted in the proximal domain (Δ138-373), with strong accelerations in activation kinetics (33,34), are also shown for comparison. (C) Summary of activation rates at 0 mV (left) and 4 kcal/mol of electrochemical driving force (right). The speed of activation of the different channel variants is compared according to the inverse value of the half-activation time. The t½ values at 0 mV or those graphically determined at 4 kcal/mol from the crossing of the activation graphs and the 4 kcal/mol line in B (right panel) were used. *p < 0.05 versus wild-type.

Effects of S4-S5 loop mutations on HERG deactivation kinetics

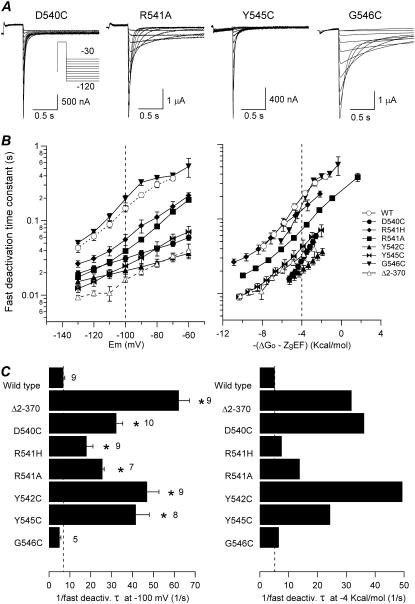

The effects of S4-S5 loop mutations on the time constant of the fast deactivation component are summarized in Fig. 8. No significant differences in the rate of deactivation as a function of voltage were observed for G546C as compared with wild-type. However, considerably faster rates were obtained for the rest of the S4-S5 mutants. This acceleration of deactivation ranged from about sevenfold faster for Y542C than wild-type at −100 mV to almost threefold as observed with R541H. It is important to note the smaller inclination of the D540C and Y542C τ-versus-voltage plots as compared with those of the rest of mutants. This tended to equalize the tail-current kinetics at very negative voltages, suggesting a reduction of the voltage dependence of closing from introduction of a cysteine in these positions. When the deactivation rates were plotted as a function of total potential energy (−(ΔGo − zgEF)), a clear tendency of the slopes obtained with the different mutants to be equal was observed, except for D540C channels, for which a steeper trace was apparent. Comparison of deactivation rates at an equivalent driving force of −4 kcal/mol also showed that although very small accelerations of deactivation are obtained with R541H and G546C mutants, the time constant of deactivation is notably smaller in mutants D540C, R541A, Y542C, and Y545C than in wild-type, meaning deactivation accelerations of about seven-, three-, nine-, and fivefold, respectively. Interestingly, whereas the accelerations of deactivation at −100 mV in the S4-S5 loop mutants were always smaller than that of the Δ2-370 construct lacking most of the amino terminus, equivalent or greater accelerations than that of the Δ2-370 mutant were observed at the same driving force with D540C, Y542C, and Y545C channels.

FIGURE 8.

Effect of S4-S5 loop mutations on HERG deactivation rates. (A) Representative currents obtained with the voltage protocol indicated in the inset. (B) Plots of fast deactivation time constants as a function of voltage (left) or total electrochemical driving force (right). (C) Summary of deactivation rates at −100 mV (left) and −4 kcal/mol of electrochemical driving force (right). The speed of deactivation of the different mutants is compared according to the inverse value of the deactivation time constant. Time constant values obtained at −100 mV or those graphically determined at −4 kcal/mol were used. *p < 0.05 versus wild-type.

Gating modifications induced by S4-S5 loop alterations in channels lacking the amino terminus

The aforementioned results demonstrate that in addition to the previously reported effects of amino-terminal deletions and S4-S5 loop mutations on HERG deactivation properties (19,21,34,47,48), clear modifications on activation gating can also be induced by structural alteration of these domains. Therefore, the effects of S4-S5 loop mutations were also assessed in the background of the Δ2-370 variant, which is lacking almost the whole amino terminus. As an initial approach, three S4-S5 mutants were used, corresponding to those showing no effect (G546C) or intermediate (R541A) and strong (Y542C) accelerations of closing kinetics.

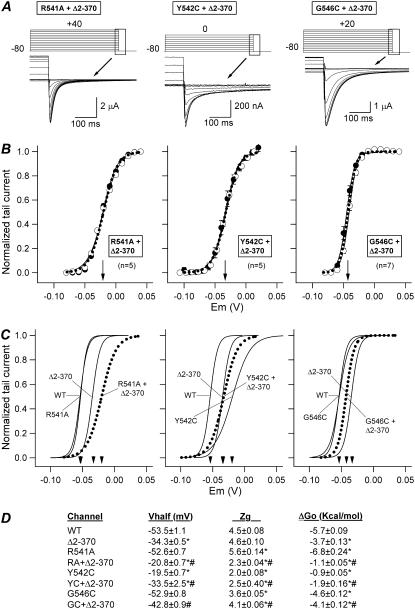

Fig. 9 summarizes the effects of the double mutations on activation voltage dependence. Fig. 9 A shows current traces in response to the voltage-clamp protocols depicted on top, and Fig. 9 B illustrates steady-state activation curves constructed from the relation between depolarization membrane voltage and the amplitude of tail currents, using 10-s depolarizing steps and two holding potentials. Comparison of Boltzmann curves for the double mutants and those of wild-type and single mutants in Fig. 9 C indicates that the impact of the mutation is clearly different in channels with or without the amino terminus. Thus, the small changes in V½ and zg values (0.9 mV and −1.1 equivalent gating charges) obtained with the R541A single mutant, largely differ from the 13 mV depolarizing shift and the 2.3 reduction in zg induced by the mutation in the Δ2-370 channel background. Subsequently, the −1.1 kcal/mol of ΔGo increase between R541A and wild-type channels is changed to 2.6 kcal/mol between the R541A + Δ2-370 and Δ2-370 variants. Therefore, the slight reduction of free energy needed for channel activation (destabilization of closed states relative to activated states) caused by mutating residue 541 is changed to a clear net increase in free energy (destabilization of activated states relative to closed ones) by introducing the R541A mutation in the Δ2-370 background. Performance of similar comparisons with the Y542C mutation reveals that, whereas the single Y542C mutant exhibits a positive shift of 34 mV and a zg reduction of 2.0, a similar reduction in the slope of the I/V curve but a shift of only 0.8 mV is induced by mutating the same residue in the Δ2-370 construct. Concomitantly, the 4.8 kcal/mol increase in ΔGo obtained with the Y542C mutation is reduced to 1.8 kcal/mol when the mutation is combined with the deletion of the amino terminus. However, a quite different pattern is observed with the G546C mutation. In this case, the limited 0.6 mV rightward shift obtained with the single mutant is changed to an 8.5 mV leftward shift between the G546C + Δ2-370 and the Δ2-370 constructs, and the 0.9 reduction in zg is diminished to 0.5. This means a small change in ΔGo increase from 1.1 kcal/mol after introducing the G546C mutation in wild-type channels, to −0.7 kcal/mol after introduction of the same mutation in Δ2-370.

FIGURE 9.

Steady-state activation voltage dependence of HERG channels without amino terminus and carrying single-point mutations in the S4-S5 loop. (A) Comparison of membrane currents obtained from oocytes expressing double mutant HERG channels after 10-s depolarizations to different voltages as indicated at the top. Only currents recorded at the end of the depolarizing steps and the tail currents corresponding to the boxed area are shown. Note the more negative repolarization voltage (−100 mV) used with G546C + Δ2-370 channels as compared with that (−80 mV) used with R541A + Δ2-370 and Y542C + Δ2-370 constructs. (B) Activation voltage dependence under steady-state conditions of the double mutant channels. Fractional activation curves were obtained from tail currents, with open and filled symbols corresponding to data recorded in response to 10-s prepulses from hyperpolarized and depolarized holding voltages, respectively. The continuous lines correspond to Boltzmann curves that best fitted the data. The dotted lines represent the deduced position of the activation curves under steady-state conditions obtained as a mean of those corresponding to both holding voltages. Note the good correspondence of all plots regardless of the holding-potential level. The V½ values for the steady-state curves are indicated by arrows in the graphs. (C) Superimposed steady-state activation curves for different constructs. Activation curves for wild-type channels and those corresponding to the single mutants are also shown for comparison. (D) Summary of kinetic and thermodynamic parameters obtained under steady-state conditions for the different channels. *p < 0.05 versus wild-type. #p < 0.05 versus single mutants in the S4-S5 loop or amino-terminus-deleted Δ2-370 channel.

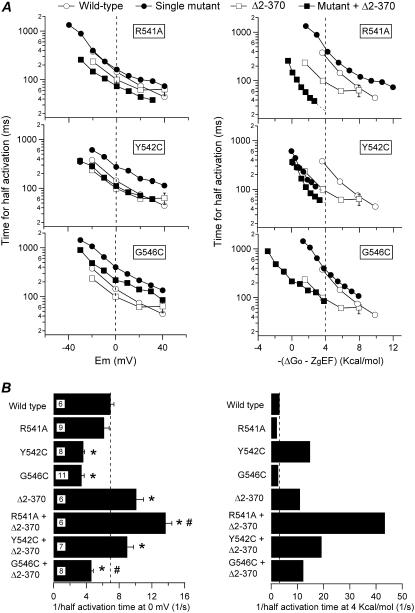

The differences in the impact of the S4-S5 loop mutations in channels with or without the amino terminus can be extended to the activation time course. As shown in Fig. 10, the time necessary to reach half-maximal activation at 0 mV was significantly reduced from 99 ± 8.6 ms (n = 6) in the Δ2-370 mutant to 73 ± 4 ms (n = 6) in the R541A + Δ2-370 construct. This contrasts with the almost identical activation rate observed at that voltage when wild-type and R541A channels are compared. These differences were still more pronounced after compensation of activation rates for differences in driving force because the slightly slower rate of activation exhibited by the R541A mutant at 4 kcal/mol (see also above) was changed to an almost fourfold faster rate in the R541A + Δ2-370 construct as compared with the Δ2-370 channel. Clear differences were also observed after performance of a similar analysis with the Y542C and G546C mutations. Thus, compared with wild-type activation rates, the significantly slower rates exhibited by the Y542C and G546C mutants at 0 mV were either abolished by introducing a cysteine in position 542 of the Δ2-370 channel (Y542C + Δ2-370 activation t½ 111 ± 9.5 ms, n = 7) or remained slow in the G546C + Δ2-370 mutant (216 ± 11.0 ms, n = 8). Furthermore, the 4.6-fold faster than wild-type activation shown by the Y542C mutant at 4 kcal/mol was reduced to a 1.7-fold faster rate of the Y542C + Δ2-370 construct as compared with the Δ2-370 channel at the same driving force. Finally, no changes in activation rates were observed at 4 kcal/mol regardless of the background in which the G546C mutation was introduced.

FIGURE 10.

Effect of combining S4-S5 single-point mutations with the deletion of the amino terminus on HERG activation rates. (A) Plots of the dependence of activation rates on depolarization membrane potential (left) or total potential driving force (right) for the different mutants. (B) Comparisons of the activation speed expressed as the inverse of the half-activation time at 0 mV (left) or 4 kcal/mol of electrochemical driving force (right). Data from wild-type channels and single mutants also illustrated in Figs. 3 and 7 are shown for comparison. *p < 0.05 versus wild-type. #p < 0.05 versus single mutants in the S4-S5 or amino-terminus-deleted Δ2-370 channel.

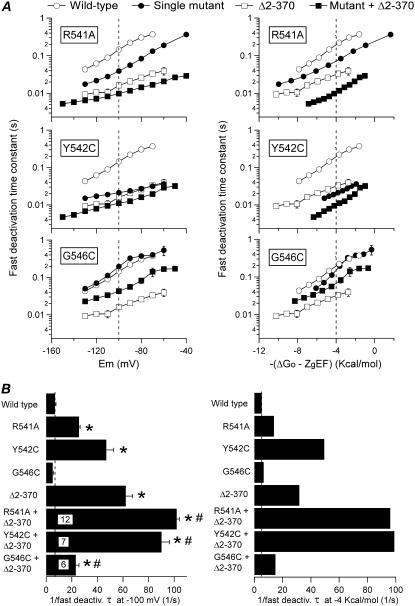

As a final verification, we also compared the effects of mutating S4-S5 loop residues on closing kinetics with and without the amino terminus. The results of this analysis are summarized in Fig. 11. Surprisingly, clearly additive accelerations of closing were obtained after combining the elimination of the amino terminus with mutations of residues 541 or 542, both at −100 mV and at an equivalent driving force of −4 kcal/mol. On the other hand, the acceleration of closing induced by removal of the amino terminus was significantly reduced by the G546C mutation. Thus, the 9.0- and 6.1-fold faster than wild-type deactivation rates of Δ2-370 channels at −100 mV and −4 kcal/mol, respectively, became 3.3- and 4.4-fold faster in the G546C + Δ2-370 construct than in Δ2-370. As discussed below, this suggests that neither of the structural alterations in the S4-S5 linker is entirely neutral in respect to deactivation characteristics. In addition, the similar phenotypes exhibited by the S4-S5 linker mutants and the channel variants lacking amino-terminal segments are probably not exclusively caused by disruption of an interaction between the amino terminus and the S4-S5 loop because in this case no further effect of the mutations should be expected in channels lacking the whole amino terminus.

FIGURE 11.

Effect of combining S4-S5 single-point mutations with the deletion of the amino terminus on HERG deactivation rates. (A) Plots of fast deactivation time constants as a function of voltage (left) or total electrochemical driving force (right). (B) Summary of deactivation rates at −100 mV (left) and −4 kcal/mol of electrochemical driving force (right). The speed of deactivation of the different mutants is compared according to the inverse value of the deactivation time constant. Data from wild-type channels and single mutants also illustrated in Figs. 4 and 8 are shown for better comparison. *p < 0.05 versus wild-type. #p < 0.05 versus single mutants in the S4-S5 loop or amino-terminus-deleted Δ2-370 channel.

DISCUSSION

In this article we show the characterization of gating and thermodynamic properties of HERG channels carrying either single or combined structural alterations in the amino terminus and S4-S5 linker domains. The impact of such structural modifications on gating is also assessed using protocols capable of yielding kinetic parameters under true steady-state conditions. Whereas previous work emphasized the need to perform adequately designed experiments to obtain real steady-state properties and to derive kinetic parameters in a way independent of the researcher or the underlying gating model (22,34,35), such circumstances are frequently neglected (2,23–33). Our results demonstrate that, in most cases, the use of conditioning pulses of one or a few seconds is clearly insufficient to reach equilibrium. These results also indicate that 10-s-long prepulses could yield quasi-steady-state characteristics for channels showing relatively fast activation/deactivation rates, but they might be inadequate to determine the kinetic and thermodynamic behavior of channels with slow activation and deactivation rates around the V½ values of the activation curves (e.g., wild-type or G546C isoforms). Apart from introducing uncertainties in the calculated parameters, this would also preclude appropriate estimations of the impact caused by a structural modification until measurements are performed under equivalent conditions. Interestingly, the key role of slow activation gating in deviations from steady state has been previously recognized, even after long depolarization prepulses (22). Our results indicate that the combination of slow activation and deactivation rates determines the shifts from the steady-state activation (n∞) curves. Thus, very small shifts in n∞ curves are obtained, not only with Δ138-373 channels showing a selective acceleration of activation kinetics but also with several constructs (e.g., Δ2-16, Δ2-135, Δ2-370, R541H, R541A, or Y542C) exhibiting activation kinetics equivalent to those of wild-type but a marked acceleration of closing.

Previous work with channel constructs modified in the initial region of HERG amino terminus including the eag/PAS domain indicated the crucial role of this segment in setting deactivation characteristics and suggested that it can interact with the gating machinery, likely at the S4-S5 loop level (19–21,23). A specific role on HERG activation gating has also been proposed for the proximal domain located in the amino terminus between the eag/PAS and the first transmembrane helix, because deleting this region or modifying a short cluster of basic residues near S1 helix caused strong alterations of activation properties (33,34,45). However, a possible role of the initial amino-terminal segment on activation properties has not been previously recognized. Our current results indicate that the relevance of this protein segment in normal activation gating is greater that previously depicted. Thus, significant positive shifts in steady-state activation voltage dependence associated with a reduction of zg values and a less negative ΔGo are caused by selective deletion of this domain. These effects map to the initial region of the protein because they are also observed in channel variants lacking only the first 16 residues of the amino terminus. The differences in activation kinetics also extend to opening rates once differences in driving force are taken into account because the activation of the deleted constructs is at least twofold faster at equivalent electrochemical potentials. Because these deleted channels also show a marked acceleration of deactivation, it is conceivable that the alterations in the amino terminus cause stabilization of a transition state leading to a smaller energetic barrier between the group of closed and open states and hence faster activation and deactivation kinetics.

It is important to emphasize that our analysis does not allow us to identify the individual steps in the gating pathway that are influenced by the mutations but only to recognize positions or structures altering the whole gating process. It is also evident that for a voltage-dependent event, the speed of the process will be related to the amount of force (chemical plus electrostatic potential) driving it. Therefore, the distinct deviations from electrochemical equilibrium must be taken into account in comparing mutants to ensure that differences in gating rates are not simply secondary to shifts in voltage dependence. It could be argued that, because activation and deactivation rates are measured at potential ranges at which subsecond time constants are present but very long voltage steps are necessary to derive the equilibrium parameters, different gating transitions are being isolated in both cases. Note, however, that although activation and deactivation rates cannot be individually measured at potentials around the activation V½ (e.g., −53 mV for wild-type channels) because of superpositioning of the two processes, extrapolation of their values up to these voltages indicates that, for example, for wild-type channels, activation half-time and fast deactivation rate are longer than 1 s. This suggests that the measured rates and the equilibrium parameters both qualify the global gating process. It also validates the use of the steady-state V½ and zg values to correct and compare the gating rates of the different mutants. Interestingly, except for the D540C mutant, which shows a reduced voltage dependence of activation rates, the similar slope of the plots relating the gating parameters of the different constructs either with voltage or with driving force over a wide range indicates that similar conclusions about the effect of the mutations and the role of different regions in gating would be reached if activation (and deactivation) rates extrapolated to potential values near V½ are used.

Deletion of the proximal domain located after the eag/PAS segment in the amino terminus causes a strong alteration in activation parameters, but an irrelevant participation of this domain on deactivation has been proposed (34). However, a significant acceleration of closing is observed in these proximal-domain-deleted channels once differences in total potential energy driving deactivation are considered. As previously pointed out (33), care should be taken when compensating deactivation rates for driving force because the extent to which the gate remains coupled to the voltage sensor movement during closing is still an open question. Thus, the time constants of deactivation have to be corrected for the corresponding variations in zg and voltage dependence of activation only if channel closure remains directly coupled to voltage sensor movements. Until now, the selective alterations of activation and deactivation gating by specific modification of the proximal and the initial amino-terminus domains, respectively, have been taken as an indication that both processes were not simple reversions of each other. However, it is tempting to speculate that the common alterations in response to both structural alterations demonstrated here are produced because activation and deactivation gating are related and similarly coupled to sensor reorganizations, although they can also be strongly influenced by other domains or structures within the protein.

Although the molecular mechanism by which some structural alterations modify the distribution of HERG closed and open states is still unclear, a combination of steady-state and kinetic data can provide important information to identify gating-sensitive regions in the channel and to show the relative stability of those states under different conditions. We observed that all mutants lacking the initial portions of the amino terminus showed a positively shifted V½ of steady-state activation and a less negative ΔGo compared with wild-type, which indicates that such deletions shift the equilibrium toward the closed state. Conversely, a negative shift and an increased ΔGo indicating a destabilization of the closed state were observed for proximal domain-deleted channels. Interestingly, in both cases an accelerated activation is obtained once differences in electrochemical potential energy driving activation (i.e., −(ΔGo − zgEF) or the differences in total energy between the open and closed states) are taken into account. This suggests that the presence of any amino-terminal segment contributes in wild-type channels to specific chemical interactions that raise the energy barrier for activation.

Recent work has localized the modulatory effects of the proximal domain on gating activation to a short positively charged sequence between residues 362 and 366 that seems to act through an electrostatic influence on the gating machinery (33). Whether this influence is exerted by a direct interaction of this sequence with the gating structures themselves (e.g., voltage sensor, S4-S5 linker, or channel gate at the bottom of S6) or indirectly through some intermediate structure (e.g., distal amino or eag/PAS domains) remains an open question. Our results indicate that a similar facilitation of activation is apparent at the same driving force in channels lacking the initial portion of the amino terminus, the proximal domain, or both. Because the effects of such deletions on activation (and deactivation) rates are similar and nonadditive (as illustrated by Δ2-370 channels; Figs. 3 C and 4 C), it is possible to speculate that an adequate positioning of the eag/PAS-containing region (most probably the first 16 N-terminal residues) toward the channel core is important not only for normal deactivation as previously proposed but also for activation gating. Consequently, it is possible that maintenance of a normal organization in the amino terminus is essential for proper orientation of this region and that disrupting it could contribute to modifications of activation properties. This would also be consistent with the dominant effect of its deletion on activation voltage dependence. Thus, the negative shifts caused by removal of the proximal domain in the Δ138-373 variant are readily reversed when both proximal and the initial amino-terminus domains are eliminated, as demonstrated by the similar voltage dependencies exhibited by the Δ2-16, Δ2-135, and Δ2-370 constructs.

It has been proposed that an interaction of the initial part of the amino terminus with the S4-S5 linker acts as a determinant of HERG slow deactivation (19,23,39). It has also been shown that some mutations in this linker alter HERG activation properties and that it constitutes a crucial component of the activation process by acting as a coupler between voltage sensor movements and the gate (39,40). We reasoned that if physical interaction(s) between the amino terminus and the S4-S5 loop also participate in modulation of activation gating, mutations introduced in the contact point(s) at the level of the S4-S5 loop could phenocopy the effect of the amino-terminal deletions. Furthermore, it could also be expected that the effects of both structural alterations would not be additive. Steady-state properties of mutants in residues 540 to 546 show some differences as a function of the mutated residue. Clear displacements of the V½ to more positive voltages and a notably less negative value of ΔGo were obtained after introducing a cysteine at residues D540, Y542, and Y545. On the other hand, a remarkable acceleration of activation (and deactivation) kinetics was observed in these three mutants, indicating an agreement between the behavior of the channels lacking the initial segment of the amino terminus and that of the S4-S5 loop-altered constructs. As an additional control to strengthen the possibility of an amino terminus/S4-S5 loop interaction, we characterized the effect of mutations in the S4-S5 linker using an amino-terminal-deleted channel as background. Surprisingly, in all cases the behavior of the double mutants did not correspond to any of the single mutants. It is difficult to conceive a mechanism by which the S4-S5 single-point mutations could cause additional effects on channels lacking virtually the whole amino terminus if such an effect strictly relies on a physical interaction between the two structures. Although these data are not contrary to the possibility that such an interaction exists, they demonstrate that in no case are the structural and/or functional alterations induced in the gating machinery by the S4-S5 mutations neutral by themselves. Therefore, caution must be exercised when using them as an argument in favor of or against the existence of the interaction.

The changes in activation kinetics of the D540C and Y542C channels were accompanied by a strong zg reduction. Thus, our data indicate the existence of an almost flat energetic profile for these mutants, characterized not only by a small thermodynamic tendency of the closed-to-open transition to take place at 0 mV (i.e., near zero ΔGo) but also by a low activation energy (i.e., small ΔG‡ of the transition state between the closed and open states). Remarkably, we detected a very small voltage dependence of the D540C channel activation rates. It has been shown that neutralization of the negative charge in position 540 makes a prominent component of gating charge movement appear at negative voltages, where channels do not open (49). Altogether, the negative and positive shifts in the Q-V and the G-V relations, respectively, and the effects on activation and deactivation kinetics suggest that the mutation uncouples the movements of the voltage sensor and the activation gate. Albeit with slight variations, similar alterations have been thoroughly characterized in Shaker channels in which several mutations in the S4 helix (50,51), the S4-S5 linker (52), and the bottom of S6 (53) have been shown to disrupt the normally tight coupling between voltage sensor and gate. In that case, movement of the voltage sensor appeared to be hindered by coupling to the activation gate, thus helping to explain the effects of carboxy-terminal S6 mutations in which unloading this region from the S4-S5 linker allows the S4 segment to more easily carry its gating charge without effectively opening the permeation pathway (53). Previous work on HERG strengthened the evidence of an interaction between the bottom of S6 and the first part of the S4-S5 linker, specifically at residue 540 (40,54). Interestingly, sensor and pore opening uncoupling in Shaker leads to slowed activation kinetics (e.g., ILT and V2 mutants; 52,55), but the opposite happens in the HERG D540C mutant. It is possible that whereas in Shaker such uncoupling favors a more stable voltage sensor-independent closed state (56), an unstable HERG closed channel is generated after mutation of residue 540. This would also be consistent with the recently observed stabilization of the activation gate closed conformation by interactions between the initial portion of the S4-S5 linker (around D540) and the C-terminal S6 residues around R665 or L666 (43).

In summary, our results indicate that besides the gate and the voltage sensor located in the central channel core, other cytoplasmic regions such as the initial part of the amino terminus can influence normal function of the HERG gating machinery. Some of these effects cannot be exerted only on the deactivation process as previously recognized (19,23,39) but also affect the activation behavior, probably by modulating the transduction of charge movement into channel opening and closing. Previous studies measuring time constants without correcting for driving force or for the shift in V½ determined at true steady state may have misinterpreted observations about how amino-terminal regions or the S4-S5 linker modulate relative stability of closed and open states and the energy of gating transitions between them. Our data also suggest that in addition to the slow movement of the voltage sensor itself (30,36,37), delaying voltage sensor and activation gate functional coupling by other channel structures can contribute to the atypically slow activation of HERG. Although further work is needed to elucidate the exact interactions involved, it is possible that physical coupling of the initial amino-terminal segment to the bottom of helix S4 or the S4-S5 linker could contribute to these modulatory effects.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants SAF2003-00329 from Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, BFU2006-10936 from Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia of Spain (both partially cofinanced by FEDER European Funds) and IB05-002 from Principado de Asturias (Spain). C.A.R. is a predoctoral fellow from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología (refs. BES-2004-3872). P.M. holds a predoctoral fellowship from FICYT of Asturias (ref. BP03-108).

Editor: Francisco Bezanilla.

References

- 1.Sanguinetti, M. C., C. Jiang, M. E. Curran, and M. T. Keating. 1995. A mechanistic link between an inherited and an acquired cardiac arrhythmia: HERG channel encodes the IKr potassium channel. Cell. 81:299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trudeau, M. C., J. W. Warmke, B. Ganetzky, and G. A. Robertson. 1995. HERG, a human inward rectifier in the voltage-gated potassium channel family. Science. 269:92–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barros, F., C. Villalobos, J. García-Sancho, D. del Camino, and P. de la Peña. 1994. The role of the inwardly rectifying K+ current in resting potential and thyrotropin-releasing hormone-induced changes in cell excitability of GH3 rat anterior pituitary cells. Pflugers Arch. 426:221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barros, F., D. del Camino, L. A. Pardo, T. Palomero, T. Giráldez, and P. de la Peña. 1997. Demonstration of an inwardly rectifying K+ current component modulated by thyrotropin-releasing hormone and caffeine in GH3 rat anterior pituitary cells. Pflugers Arch. 435:119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer, C. K., R. Schäfer, D. Schiemann, G. Reid, I. Hanganu, and J. R. Schwarz. 1999. A functional role of the erg-like inward-rectifying K+ current in prolactin secretion from rat lactotrophs. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 148:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schäfer, R., I. Wulfsen, S. Behrens, F. Weinsberg, C. K. Bauer, and J. R. Schwarz. 1999. The erg-like current in rat lactotrophs. J. Physiol. 518:401–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emmi, A., H. J. Wenzel, P. A. Schwartzkroin, M. Taglialatela, P. Castaldo, L. Bianchi, J. Nerbonne, G. A. Robertson, and D. Janigro. 2000. Do glia have heart? Expression and functional role for Ether-a-go-go currents in hippocampal astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 20:3915–3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherubini, A., G. L. Taddei, O. Crociani, M. Paglierani, A. M. Buccoliero, L. Fontana, I. Noci, P. Borri, E. Borrani, M. Giachi, A. Becchetti, B. Rosati, E. Wanke, M. Olivotto, and A. Arcangeli. 2000. HERG potassium channels are more frequently expressed in human endometrial cancer as compared to non-cancerous endometrium. Br. J. Cancer. 83:1722–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Overholt, J. L., E. Ficker, T. Yang, H. Shams, G. R. Bright, and N. R. Prabhakar. 2000. HERG-like potassium current regulates the resting membrane potential in glomus cells of the rabbit carotic body. J. Neurophysiol. 83:1150–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosati, B., P. Marchetti, O. Crociani, M. Lecchi, R. Lupi, A. Arcangeli, M. Olivotto, and E. Wanke. 2000. Glucose- and arginine-induced insulin secretion by human pancreatic b-cells: the role of HERG K+ channels in firing and release. FASEB J. 14:2601–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viskin, S. 1999. Long QT syndromes and torsade de pointes. Lancet. 354:1625–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiang, C., and D. M. Roden. 2000. The long QT syndromes: Genetic basis and clinical implications. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 36:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keating, M. T., and M. C. Sanguinetti. 2001. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias. Cell. 104:569–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redfern, W. S., L. Carlsson, A. S. Davis, W. G. Lynch, I. MacKenzie, S. Palethorpe, P. K. S. Siegl, I. Strang, A. T. Sullivan, R. Wallis, A. J. Camm, and T. G. Hammond. 2002. Relationship between preclinical cardiac electrophysiology, clinical QT interval prolongation and torsade de pointes for a broad range of drugs: evidence for a provisional safety margin in drug development. Cardiovasc. Res. 58:32–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas, D., W. Zhang, K. Wu, A.-B. Wimmer, B. Gut, G. Wendt-Nordahl, S. Kathöfer, V. A. W. Kreye, H. A. Katus, W. Schoels, J. Kiehn, and C. A. Karle. 2003. Regulation of potassium channel activation by protein kinase C independent of direct phosphorylation of the channel protein. Cardiovasc. Res. 59:14–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finlayson, K., H. J. Witchel, J. McCulloch, and J. Sharkey. 2004. Adquired QT interval prologation and HERG: Implications for drug discovery and development. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 500:129–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roden, D. M., R. Lazzara, M. Rosen, P. J. Schwartz, J. Towbin, and G. M. Vincent. 1996. Multiple mechanisms in the long-QT syndrome. Current knowledge, gaps, and future directions. Circulation. 94:1996–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz, P. J. 2005. Management of long QT syndrome. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2:346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang, J., M. C. Trudeau, A. M. Zappia, and G. A. Robertson. 1998. Regulation of deactivation by an amino terminal domain in Human ether-a-go-go-related gene potassium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 112:637–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, J., C. D. Myers, and G. A. Robertson. 2000. Dynamic control of deactivation gating by a soluble amino-terminal domain in HERG K+ channels. Biophys. J. 115:749–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morais-Cabral, J. H., A. Lee, S. L. Cohen, B. T. Chait, M. Li, and R. MacKinnon. 1998. Crystal structure and functional analysis of the HERG potassium channel N terminus: a eukariotic PAS domain. Cell. 95:649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schönherr, R., B. Rosati, S. Heh, V. G. Rao, A. Arcangeli, M. Olivotto, S. H. Heinemann, and E. Wanke. 1999. Funtional role of the slow activation property of ERG K+ channels. Eur. J. Neurosci. 11:753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen, J., A. Zou, I. Splawski, M. T. Keating, and M. C. Sanguinetti. 1999. Long QT syndrome-associated mutations in the Per-Arnt-sim (PAS) domain of HERG potassium channels accelerate deactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:10113–10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, S., S. Liu, M. J. Morales, H. C. Strauss, and R. L. Rasmusson. 1997. A quantitative analysis of the activation and inactivation kinetics of HERG expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. 502:45–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kupershmidt, S., D. J. Snyders, A. Raes, and D. M. Roden. 1998. A K+ channel splice variant common in human heart lacks a C-terminal domain required for expression of rapidly activating delayed rectifier current. J. Biol. Chem. 273:27231–27235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aydar, E., and C. Palmer. 2001. Functional characterization of the C-terminus of the human ether-à-go-go-related gene K+ channel (HERG). J. Physiol. 534:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paulussen, A., A. Raes, G. Matthijs, D. J. Snyders, N. Cohen, and J. Aerssens. 2002. A novel mutation (T65P) in the PAS domain of the human potassium channel HERG results in the long QT syndrome by trafficking deficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 277:48610–48616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paulussen, A. D. C., A. Raes, R. J. Jongbloed, R. A. H. J. Gilissen, A. A. M. Wilde, D. J. Snyders, H. J. M. Smeets, and J. Aerssens. 2005. HERG mutation predicts short QT based on channel kinetics but causes long QT by heterotetrameric trafficking deficiency. Cardiovasc. Res. 67:467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu, J., M. Zhang, M. Jiang, and G.-N. Tseng. 2003. Negative charges in the transmembrane domains of the HERG K channel are involved in the activation and deactivation gating processes. J. Gen. Physiol. 121:599–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subbiah, R. N., C. E. Clarke, D. J. Smith, J. Zhao, T. J. Campbell, and J. I. Vandenberg. 2004. Molecular basis of slow activation of the human ether-à-go-go related gene potassium channel. J. Physiol. 558:417–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subbiah, R. N., M. Kondo, T. J. Campbell, and J. I. Vandenberg. 2005. Trytophan scanning mutagenesis of the HERG K+ channel: The S4 domain is loosely packed and likely to be lipid exposed. J. Physiol. 569:367–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, M., J. Liu, M. Jiang, D.-M. Wu, K. Sonawane, H. R. Guy, and G.-N. Tseng. 2005. Interactions between charged residues in the transmembrane segments of the voltage-sensing domain in the hERG channel. J. Membr. Biol. 207:169–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saenen, J. B., A. J. Labro, A. Raes, and D. J. Snyders. 2006. Modulation of HERG gating by a charge cluster in the N-terminal proximal domain. Biophys. J. 91:4381–4391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viloria, C. G., F. Barros, T. Giráldez, D. Gómez-Varela, and P. de la Peña. 2000. Differential effects of amino-terminal distal and proximal domains in the regulation of human erg K+ channel gating. Biophys. J. 79:231–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miranda, P., T. Giráldez, P. de la Peña, D. G. Manso, C. Alonso-Ron, D. Gómez-Varela, P. Domínguez, and F. Barros. 2005. Specificity of TRH receptor coupling to G-proteins for regulation of ERG K+ channels in GH3 rat anterior pituitary cells. J. Physiol. 566:717–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith, P. L., and G. Yellen. 2002. Fast and slow voltage sensor movements in HERG potassium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 119:275–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piper, D. R., A. Varghese, M. C. Sanguinetti, and M. Tristani-Firouzi. 2003. Gating currents associated with intramembrane charge displacement in HERG potassium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:10534–10539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang, M., J. Liu, and G.-N. Tseng. 2004. Gating charges in the activation and inactivation processes of the HERG channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 124:703–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanguinetti, M. C., and Q. P. Xu. 1999. Mutations of the S4–S5 linker alter activation properties of HERG potassium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. 514:667–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]