Abstract

The tumor suppressor VHL (von Hippel-Lindau protein) serves as a negative regulator of hypoxia-inducible factor-α subunits. However, accumulated evidence indicates that VHL may play additional roles in other cellular functions. We report here a novel hypoxia-inducible factor-independent function of VHL in cell motility control via regulation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) endocytosis. In VHL null tumor cells or VHL knock-down cells, FGFR1 internalization is defective, leading to surface accumulation and abnormal activation of FGFR1. The enhanced FGFR1 activity directly correlates with increased cell migration. VHL disease mutants, in two of the mutation hot spots favoring development of renal cell carcinoma, failed to rescue the above phenotype. Interestingly, surface accumulation of the chemotactic receptor appears to be selective in VHL mutant cells, since other surface proteins such as epidermal growth factor receptor, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, IGFR1, and c-Met are not affected. We demonstrate that 1) FGFR1 endocytosis is defective in the VHL mutant and is rescued by reexpression of wild-type VHL, 2) VHL is recruited to FGFR1-containing, but not EGFR-containing, endosomal vesicles, 3) VHL exhibits a functional relationship with Rab5a and dynamin 2 in FGFR1 internalization, and 4) the endocytic function of VHL is mediated through the metastasis suppressor Nm23, a protein known to regulate dynamin-dependent endocytosis.

The von Hippel-Lindau disease is an inherited disorder that manifests in tumor formation in multiple organs (1, 2). The disease is characterized by highly vascularized tumors mainly due to overproduction of angiogenic factors. The underlying genetic defect was identified as mutations in the VHL tumor suppressor gene (3). The biological role of VHL is prominently linked to its E33 ubiquitin ligase activity toward a subset of cellular proteins, thus promoting their ubiquitination and degradation (4, 5). Prominent among its cellular targets are the α subunits (1α, 2α, and 3α) of the key transcription factor, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), involved in the cellular oxygen-sensing mechanism (6–8). Tumorigenic mutations that affect E3 ligase function of VHL result in constitutive stabilization of HIF-α, leading to transcriptional activation of several target genes of HIF (9), including those encoding critical angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor and enzymes involved in glucose metabolism (10).

Renal cell carcinomas (RCCs) harboring VHL mutations are often metastatic, and reexpression of wild-type VHL suppresses the metastatic behavior in RCC-derived cell lines (11, 12), although the mechanisms remain unclear. VHL mutant cells exhibit increased scattering upon hepatocyte growth factor treatment (13). Enhanced response to SDF-1 (stromal cell-derived factor-1), due to overexpression of chemokine receptor CXCR4, was also recently identified as a possible mechanism by which VHL tumors might disseminate to distant organs (14). On the other hand, accumulated evidence suggests that VHL null RCC cells exhibit intrinsically elevated migratory potential under normal serum conditions without chemokine or hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor induction (11, 15–17). In this report, we sought to understand the function of VHL in control of cell motility. Our data reveal an intriguing VHL mutant phenotype of selective FGFR1 accumulation on the cell surface. Surface accumulation of FGFR1 leads to elevated FGFR1 signaling via ERK1/2 and influences the migratory potential of VHL mutant cells toward serum. Further, we show that this phenotype is the result of a defect in VHL-mediated endocytosis of FGFR1. Interestingly, this VHL function required partnership with Nm23H1, a metastasis suppressor protein known to regulate dynamin-mediated endocytosis (18–21).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines and Reagents

VHL null RCC line 786-O and VHL+ human embryonic kidney HEK293 cells were from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Other cell lines from ATCC were Caki-1, Caki-2, ACHN, and HK-2. 786-Vec, 786-EGFP, and 786-VHL cells were generated by stable transfection of 786-O cells with pCDNA3.1, pCMV-EGFP, and pCMV-VHL (see below), respectively, and polyclonal selection by G418 (Invitrogen). Cells were maintained in DMEM (high glucose) supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and used within eight passages. G418 was excluded in all assay conditions. Transfection of HEK293 with Lipofectamine 2000 (~85% efficiency) was performed in a 6-well format according to the supplier’s protocol (Invitrogen). Electroporation using Nucleofector (Amaxa Biosystems) was performed with Solution T and program T-01 supplied by the vendor, which consistently achieved ~75% transfection efficiency. All inhibitors (PD98059, 3-(4-dimethylaminobenzylidenyl)-2-indolin-one (DMBI), and PDGFR III (Calbiochem)), dissolved in Me2SO (Sigma), were added to prewarmed (37 °C) culture medium and used at the indicated concentrations (see below).

Plasmid Constructs

pCMV-EGFP and pCMV-VHL were constructed by PCR, cloning EGFP and human VHL into the EcoRV site of pCDNA3.1 (Invitrogen). For EGFP-VHL, VHL was PCR-cloned into XhoI-KpnI sites of pEGFP-C1 (BD Biosciences Clontech). Plasmid-based short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) were constructed as follows. Target sequences (VHL-shRNA1, gagaactgggacgaggccg; VHL-shRNA2, gctgcccgtatggctcaac; VHL-shRNA3, gagcctagtcaagcctgag; Nm23H1-shRNA1, gtgagcgtaccttcattgc; Nm23H1-shRNA2, ggtgaaatacatgcactca) and control (random sequence ctactcagtatgcacgtcg) were cloned into pSuppressor-Neo according to instructions (Imgenex). The U6 promoter-shRNA cassette (BamHI-BglII fragment) was subcloned into the BglII site of pCMV-EGFP and screened for promoters (U6 and CMV) oriented in the opposite direction. To express shRNAs without EGFP, the constructs in pSuppressor-Neo were used. DN-FGFR1-RFP was created by PCR cloning of the FGFR1 coding sequence encompassing amino acids 1–468 into XhoI-HindIII sites of pDsRed-N1 (BD Biosciences Clontech). GST fusions of VHL were prepared by first cloning VHL open reading frames into pGEX3T (BamHI-EcoRI), followed by PCR amplification of GST or GST-VHL and subcloning into EcoRV-EcoRI of pIRES-Neo (3) (BD Biosciences Clontech). EGFP fusions of Nm23H1 and Nm23H2 were constructed by reverse transcriptase-PCR amplification of the open reading frames and cloning into pEGFP-C1 (XhoI-KpnI). VHL mutants were generated by a PCR-based method (22). The constitutively active version of HIF-2α (HIF-2α (P/A)) is an amino acid substitution of the proline residue at position 531 (P531A) that is the target of hydroxylation in normoxia. Both wild type and the constitutive HIF-2α coding sequences are cloned in the pCDNA3.0 vector and are gifts from W. Kaelin of Harvard Medical School. Wild-type and dominant negative dynamin 2-GFP and Rab5a-GFP constructs are gifts from S. Schmid of the Scripps Institute and N. Bunnet of the University of California San Francisco, respectively.

Boyden Chamber and Wound-healing Assays

Cell migration was assayed in the presence of 10 μg/ml mitomycin C (MTC). Cells grown to 90% confluence in 6-well plates were scratched with a 1000-μl pipette tip, and the wound was rinsed thoroughly. Fresh 1% serum and MTC was added to follow healing for 24 h. For inhibitor treatment, cells were treated with either mock (Me2SO) or the indicated inhibitors for 1 h prior to the addition of 1% serum. The medium mix (inhibitors or mock plus 1% serum and MTC) was replaced every 6–8 h. The assays were performed in triplicate. Trans-well Boyden chamber (8-μm pore size; Corning) assays were performed using 15,000 cells/well seeded into the upper chamber (1% serum), and migration toward high serum (10%) was followed for 12 h in the presence of MTC. Inserts were rinsed in PBS, fixed in methanol for 10 min, and stained with crystal violet for 5 min. Cells on the upper side were removed with a cotton swab, and migrated cells attached to the bottom side were counted using a × 10 objective focused at the center. For inhibitor treatment, cells were serum-starved for 12 h, trypsinized, counted, and seeded into the upper chamber (mock or inhibitors plus 1% serum and MTC). The lower chamber contained the same mix except for a 10% serum concentration. The medium mix was replaced every 6–8 h. Boyden chamber results of six independent experiments done in triplicate were analyzed using Student’s t test. DMBI and PD98056 were used at 25 μM.

Cell Surface Biotinylation

Cells grown in 6-well plates were washed with ice-cold PBS (pH 7.4) and incubated with 0.5 ml/well PBS containing 0.5 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (Pierce) for 30 min at 4 °C. Following rinsing, cells were lysed with 300 μl/well 1% Triton-radioimmune precipitation buffer containing protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). After protein estimation (BCA; Pierce), 1.5 mg of precleared extracts were incubated with respective rabbit polyclonal primary antibodies for 12 h at 4 °C in 1 ml of 1% Triton-radioimmune precipitation buffer. Protein A-agarose binding and washing was in 0.5% Triton-radioimmune precipitation buffer, and elution was in low pH buffer (50 mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.5). For β-actin control, 1.5-mg extracts were bound to streptavidin-agarose for 12 h at 4 °C, eluted in 1× SDS sample buffer, and blotted for β-actin. Immunoprecipitated receptors were detected using specific mouse monoclonal antibodies (total levels) and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (surface fraction).

Northern Blotting

Total RNA was extracted (RNAeasy Protect; Qiagen), and 20 μg/lane of total RNA were used for Northern blotting. Primeit II (Stratagene) was used to prepare FGFR1 (PCR product corresponding to amino acids 1– 468 of human FGFR1) and β-actin probes (Amersham Biosciences). Northern blotting followed standard procedures.

Western Blotting and Antibodies

Cells starved for 12 h (90% confluent in 6-well plates) were stimulated with prewarmed DMEM containing 20% serum for 15 min, washed with cold DMEM, and lysed using 200 μl of 2× SDS sample buffer/well. Lysates were collected with a cell scraper and diluted to 1× SDS sample buffer concentration. GST pull-down assays were performed according to the standard protocol provided by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). For final elution, 1× SDS sample buffer was directly added to the glutathione beads. Western blotting was according to standard procedures. All antibodies were used at recommended dilutions. Mouse monoclonal antibodies were p-p38MAPK (Cell Signaling), doubly phosphorylated ERK1/2 (Sigma), β-actin (Sigma), VHL (BD Biosciences, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and Neomarkers), GFP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), EGFR (Neomarkers), HIF-1α (cross-reacted with HIF-2α; Novus Biologicals), FGFR1 (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., Lake Placid, NY), p-FGFR1 (Cell Signaling), LAMP1 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa), Nm23H1 (Biomeda), Nm23H2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and GST (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were FGFR1 (Abcam, Sigma), p-FGFR1 (Cell Signaling), ERK1/2 (Sigma), p38MAPK (Cell Signaling), AKT (Cell Signaling), p-AKT (Cell Signaling), CXCR4 (Zymed Laboratories Inc.), c-Met (Cell Signaling), IGFR1 (Cell Signaling), and EGFR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Sigma), anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma), streptavidin (Pierce), and Tyr(P) (Zymed Laboratories Inc.) were used as secondary conjugates.

Indirect Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed in PBS plus 3.7% formaldehyde for 20 min, quenched with PBS plus 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), and permeabilized with 0.15% Saponin (Sigma) for 10 min at room temperature. Incubation with respective primary and secondary antibodies was in PBS plus 1% bovine serum albumin (1 h at room temperature). Primary antibodies were used at 1:100 dilution. Secondary antibodies are highly cross-absorbed goat anti-rabbit Alexa 546, goat anti-mouse Alexa 546, goat anti-rabbit Alexa 488; and goat anti-mouse Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR), which were used at 1:150 dilution. Confocal images were acquired with an Olympus IX70 microscope (Fluoview 300).

Activated Receptor Chase and Endocytosis Studies

200 ng/ml recombinant human bFGF (Promega) was mixed with 2.5 μg/ml heparin (Sigma) in serum-free medium (with 1% bovine serum albumin) and added to serum-starved cells (for 24 h) grown on coverslips. Cells were incubated at 4 °C for 2 h to allow ligand-receptor engagement and washed with cold DMEM, and chase was initiated in prewarmed DMEM (37 °C). Coverslips were lifted and directly fixed in PBS plus 3.7% formaldehyde. 500 ng/ml recombinant human EGF (Clonetics) was used in EGFR endocytosis studies. Cells were fixed as above at the end of chase. For transferrin internalization, serum-starved cells were incubated at 4 °C with filter-sterilized 1% bovine serum albumin in DMEM for 30 min to block nonspecific binding. Cells were incubated at 4 °C with 5 μg/ml transferrin-Alexa 546 (Molecular Probes) for 30 min, washed in cold DMEM, and chased with prewarmed DMEM containing 1% bovine serum albumin (37 °C). Cells were washed once in cold DMEM, fixed as above, and directly mounted in Prolong Antifade (Molecular Probes).

RESULTS

VHL Mutant Cells Exhibit Increased Cell Motility

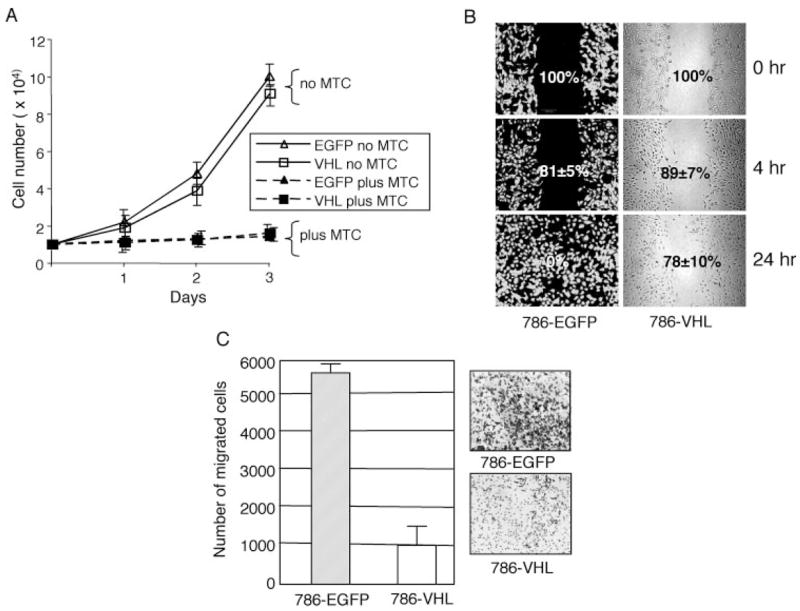

“Wound-healing” and Boyden chamber assays were employed to quantify the migratory properties of the human 786-O RCC cell line (23) polyclonally selected for stable expression of either enhanced green fluorescent protein (786-EGFP) or wild-type human VHL (786-VHL). EGFP is widely used as an inert control protein (e.g. see Refs. 24 and 25). Accordingly, we do not observe overt differences in gene expression between 786-O parental and 786-EGFP cells (supplementary Fig. S1B; see below). We have also determined that the expression level of VHL (in the 786-VHL stable cell line) is comparable with the endogenous levels in several known VHL+ kidney cell lines, such as HK-2, HEK293, and ACHN (supplemental Fig. S1A). To account for any difference in cell proliferation, all migration assays (Figs. 1, 4, and 5) were performed in the presence of 10 μg/ml MTC, a chemical that inhibits cell proliferation (Fig. 1A) (26) but not motility (26). In wound-healing experiments, 786-EGFP cells completely filled a ~500-μm wound within 24 h, whereas 786-VHL exhibited significantly reduced two-dimensional planar motility, with an estimated 78% wound remaining unhealed (Fig. 1B). Quantitative analysis of three-dimensional and chemotactic migration toward serum, assayed using Boyden chambers, showed that compared with 786-VHL cells, 786-EGFP cells exhibit a ~6-fold increased cell migration (p < 0.005) within a 12-h assay period (Fig. 1C). Thus, VHL null cells displayed an elevated migratory property that is inhibited by expression of VHL.

FIGURE 1. Re-expression of VHL inhibits cell motility in VHL mutant cells.

A, cell counts were obtained for 786-EGFP and 786-VHL stable cells grown in 1% serum conditions in the presence (plus MTC) or absence (no MTC) for the indicated duration. No significant difference in cell proliferation was observed between the two cell types in three independent experiments done in triplicate. Treatment with MTC inhibited cell proliferation in both cell types to a similar extent. B, 90% confluent cell monolayers in a 6-well culture dish were wounded with a 1000-μl pipette tip. Wound healing was followed for 786-EGFP and 786-VHL cells for 24 h. Representative images of four experiments are shown. 786-EGFP cells (left) are visualized with fluorescence, whereas 786-VHL cells (right) are with transmitted optics. The numbers within panels (with S.D. values) indicate the percentage gap left between the wound edges (indicating wound closure) at the specified time points. C, Boyden chamber assays for chemotactic cell migration showing an ~6-fold decrease of cell numbers migrated to the underside of the barrier membrane (p < 0.005) in 786-VHL compared with 786-EGFP cells in 12 h. The insets show representative images of migrated cells from six experiments done in triplicate. The error bars indicate S.D. (n = 18).

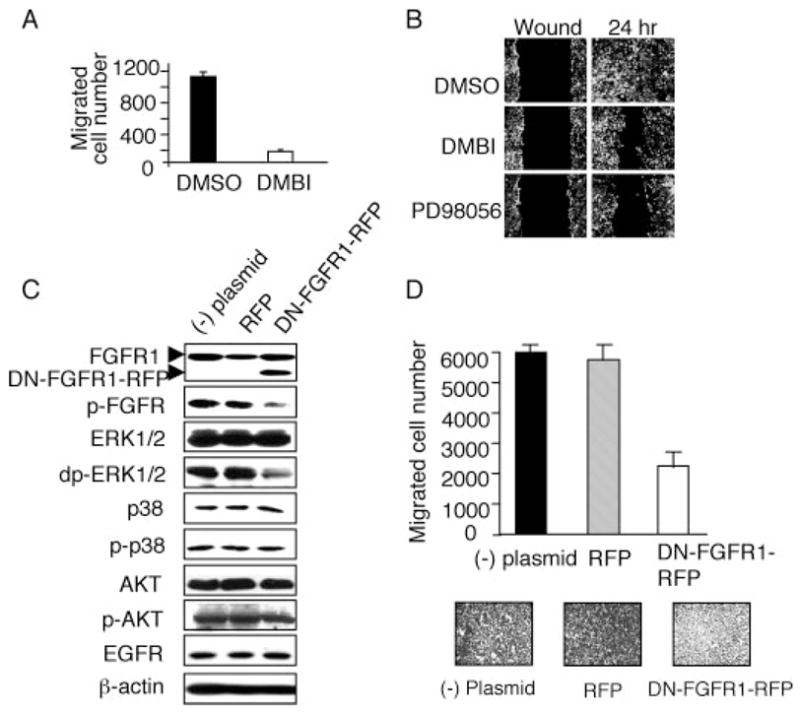

FIGURE 4. FGFR1 signaling is the major contributor to elevated ERK1/2 activity and cell migration in VHL mutant cells.

A, 786-EGFP cells were serum-starved overnight before being seeded into the upper chamber of a transwell. The cells were then incubated with medium containing 1% serum, the indicated reagents (DMBI at 25 μM), and 10 μg/ml MTC. The lower chamber contains the same mix except for 10% serum concentration. Medium/inhibitor mix was replenished every 6 h. Cells that migrated to the underside of the membrane were counted after 12 h. DMBI significantly reduces the transwell migration of the VHL(−) cells. The cell numbers presented are the total cell counts within a field of view at the center of the filter taken with a × 10 objective. Cell numbers are averages of four independent assays done in triplicate. The error bars indicate S.D. (n = 12). B, 786-EGFP cells were serum-starved overnight and then treated with serum-free medium containing the indicated reagents (solvent Me2SO, 25 μM for DMBI or PD98056) and 10 μg/ml MTC for 1 h. The scratch was then made for the wound-healing assays, and the cells were incubated in medium containing 1% serum, the inhibitors, or Me2SO and MTC. Medium/inhibitor mix was replenished every 6 h. 786-EGFP cell migration into the wound over 24 h is inhibited by DMBI and the ERK inhibitor PD98056. C, untransfected 786-O cells ((−) plasmid) or 786-O cells transfected with the control vector (RFP) or plasmid containing dominant-negative FGFR1-RFP fusion (DN-FGFR1-RFP) were stimulated with 20% serum for 15 min, and the protein extracts were subjected to Western blot. The DN-FGFR1-RFP fusion protein is detected as a faster migrating band (~12 kDa smaller; lower arrowhead) than the endogenous FGFR1 (upper arrowhead). There was no change in the endogenous FGFR1 levels. Expression of DN-FGFR1-RFP inhibited the activities of FGFR1 (p-FGFR) and ERK1/2 (doubly phosphorylated ERK1/2; dp-ERK1/2). There were no changes in AKT or p38MAPK pathways upon the expression of DN-FGFR1-RFP or RFP. Loading controls for cytosolic protein (β-actin) and membrane protein (EGFR) are shown. D, transwell assays showing expression of DN-FGFR1-RFP, but not RFP, inhibits chemotactic migration of 786-O cells (~3-fold inhibition, p < 0.005; n = 18).

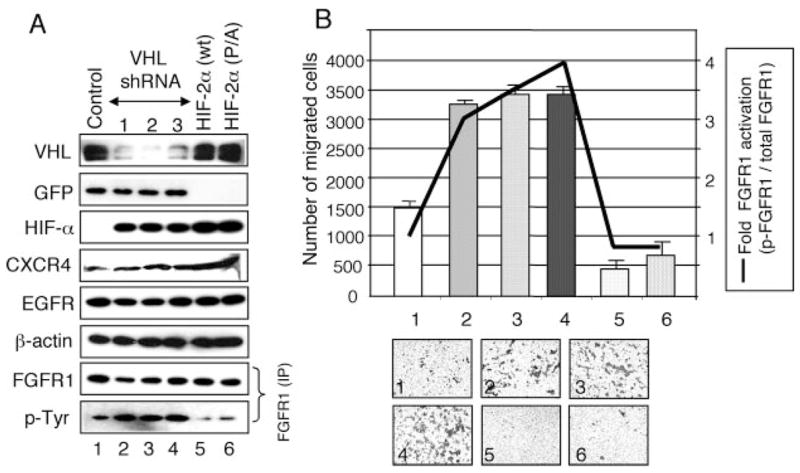

FIGURE 5. Loss of VHL leads to elevated FGFR1 activity and increased cell migration in HEK293 cells.

A, HEK293 cells were transfected with vectors expressing control shRNA (lane 1), three independent VHL shRNA constructs (lanes 2– 4), wild-type HIF-2α (HIF-2α (wt); lane 5), or constitutive HIF-2a (HIF-2α (P/A); lane 6). Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot using the antibodies indicated on the left. GFP co-expressed from the shRNA-containing plasmid was used as an expression level control. VHL protein levels are significantly knocked down by the VHL-specific shRNAs. HIF-αlevels are increased in VHL knock-down cells (lanes 2– 4) and in HIF-2αectopic expressing cells (lanes 5 and 6). CXCR4 levels are increased in VHL knockdown and in HIF-expressing cells, as expected. Controls of a cytosolic protein (β-actin), a membrane protein (EGFR), and EGFP (GFP) for shRNAs are shown. For FGFR1, equal amounts of lysates were immunoprecipitated with rabbit FGFR1 antibody and detected with mouse FGFR1 antibody or with mouse Tyr(P)-horseradish peroxidase antibody. B, Boyden chamber assays showing effects of loss of VHL and HIF-2α overexpression on cell migration in HEK293 cells. Numbers of cells that migrated to the underside of the membrane (scale on the left) were counted. The number for each graph corresponds to the sample shown in A. ~2.5-Fold elevated cell migration (p < 0.005) is seen in VHL-shRNA-treated cells compared with control shRNA-treated cells. Expression of HIF-2α (wt) or HIF-2α (P/A) led to decreased cell migration compared with the control. The insets show representative images of Boyden chamber assays of six independent experiments done in triplicate. The error bars indicate S.D. (n = 18). -Fold FGFR1 activation (scale on the right) was calculated as follows. Signal densities from Western blotting of total immunoprecipitated FGFR1 (A) and from reprobing for activated FGFR (Tyr(P)) were measured by densitometric analysis using ImageJ. The ratio of activated versus total FGFR1 (FGFR1 activation level) for control shRNA was arbitrarily set at 1. Relative FGFR1 activation levels were then plotted (line graph).

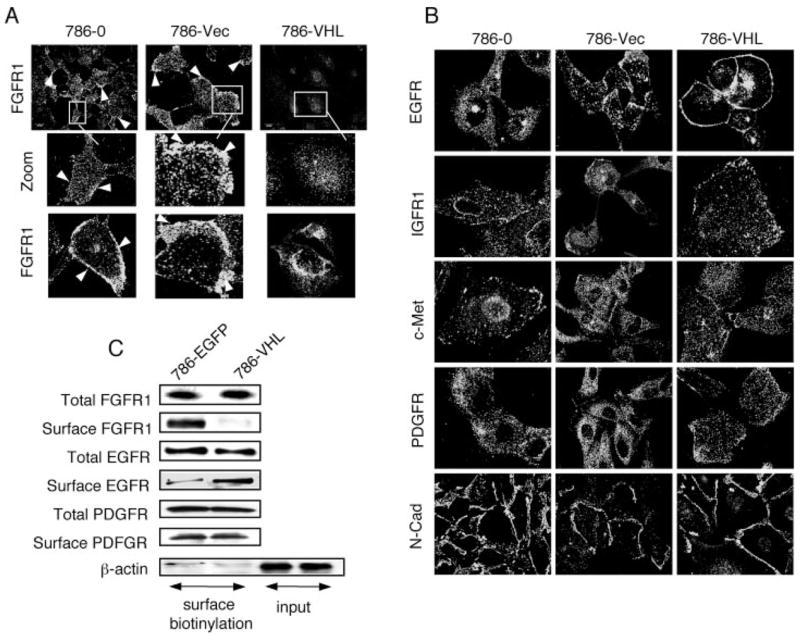

Cell Surface Accumulation of FGFR1 and Cellular Changes in VHL Null Cells

In the Drosophila tracheal tubule system, epithelial cell migration is mainly regulated by the FGF chemotactic signaling. It has been shown that Drosophila VHL negatively regulates tracheal cell migration (27). We have also demonstrated that abnormal accumulation of FGFR on tracheal cell surface, a result of defective endocytosis, can lead to aberrant cell migration (18). In tracheal cells, the ERK1-type mitogen-activated protein kinase is the major downstream mediator of the FGFR signaling pathway (18). We therefore examined whether the FGFR-ERK signaling function is evolutionarily conserved in Drosophila trachea and in the renal proximal tubule-derived tumor cells such as 786-O. We indeed observed surface FGFR1 accumulation in the VHL mutant cells (arrowheads in Fig. 2A). Reexpression of VHL in the 786-O cells dramatically reduced the cell membrane accumulation of FGFR1. We did not observe increased surface accumulation in VHL mutant cells in other surface proteins studied, namely EGFR, IGFR1, c-Met, PDGFR, and N-cadherin (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2. Surface accumulation of FGFR1 in VHL null cells.

A, FGFR1 antibody staining of 786-O parental cells, 786-O transfected with empty pCDNA3.1 vector (786-Vec), and 786-O transfected with pCMV-VHL (786-VHL). Surface accumulation of FGFR1 (arrowheads) is observed in 786-O and 786-Vec but not in 786-VHL cells. Views of large populations (upper panels) and individual cells (insets and lower panels) are shown. B, 786-O, 786-Vec, and 786-VHL cells were stained with antibodies indicated on the left. There is no increase in surface accumulation of these membrane proteins in the VHL(−) cells. C, 786-EGFP and 786-VHL cells are labeled with membrane-impermeable sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin. After immunoprecipitation with specific rabbit polyclonal antibodies, the total levels of each receptor were detected using mouse monoclonal antibodies, and the cell surface fraction was distinguished using streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase. For β-actin, cell lysates were bound to streptavidin-agarose, and the eluted proteins were checked for the greatly reduced presence of β-actin (surface biotinylation), as compared with the input lanes (probed for β-actin as loading controls) that represent one-tenth of the lysates used for immunoprecipitation. Consistent with immunostaining results (A), there is significantly lower surface localization of FGFR1 in 786-VHL cells compared with 786-EGFP cells. EGFR surface localization is slightly lower in 786-EGFP cells. PDGFR shows no change.

The differential membrane distribution of FGFR1 was confirmed by surface biotinylation assays to measure the fraction of surface versus total cellular levels. In this assay, surface proteins were selectively labeled with biotin using a membrane-impermeable cross-linker, sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin. The surface protein levels were identified, after immunoprecipitation, by Western blotting with horseradish peroxidase-streptavidin. As shown in Fig. 2C, whereas the total cellular levels of FGFR1 remained unchanged with or without VHL, reexpression of VHL led to a dramatic reduction of surface FGFR1. Consistent with our immunofluorescence data (Fig. 2B), surface levels of PDGFR were unchanged, whereas EGFR were slightly higher on the surface of 786-VHL cells compared with 786-EGFP cells (Fig. 2C). Reduced surface EGFR in VHL null cells may be due to overexpression of the autocrine tumor growth factor-α in these cells (28), which can result in increased ligand engagement of EGFR and consequently increased receptor internalization.

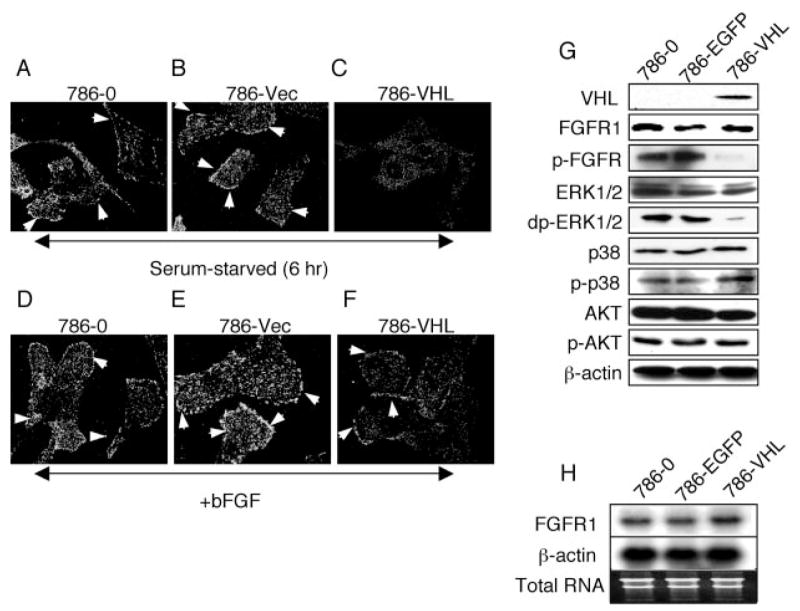

To verify that the membrane-localized FGFR1 is indeed active, we immunostained with an antibody that recognized the phosphotyrosine moieties in FGFR. Since FGFR2 is not expressed in these cells (data not shown), the phospho-FGFR (p-FGFR) antibody staining should correlate well with the activation status of FGFR1. We found a significant increase in tyrosine-phosphorylated FGFR1 at the cell surface in VHL mutant cells even after serum starvation for 6 h (Fig. 3, A and B). This indicated that high levels of surface FGFR1 lead to persistent and ligand-independent activation of the receptors as has been suggested for receptor tyrosine kinases (29, 30). On the other hand, VHL-positive cells showed no surface and very low overall p-FGFR staining under identical conditions (Fig. 3C). Stimulation of cells with bFGF and heparin leads to further increased p-FGFR staining in VHL mutant cells (Fig. 3, D and E) and a modest increase in 786-VHL cells (Fig. 3F), as expected. Further evidence of FGFR1 dysregulation came from Western blots (Fig. 3G), which showed that VHL expression significantly diminished FGFR1 activity (measured by the level of p-FGFR) without altering the total FGFR1 levels. Analysis of downstream signaling pathways revealed that whereas AKT and p38MAPK pathways remained unaffected, ERK1/2 activity (measured by the levels of doubly phosphorylated ERK1/2 (dp-ERK1/2)) was markedly reduced in 786-VHL cells (Fig. 3G). Northern blot analysis showed no changes in FGFR1 mRNA levels in 786-O, 786-EGFP, and 786-VHL cells (Fig. 3H), suggesting that membrane accumulation is not due to up-regulation of FGFR1 expression. To rule out potential artifacts arising from polyclonal selection, we transiently transfected empty plasmid (vector) or increasing amounts of plasmids expressing EGFP, pCMV-VHL, or pCMV-EGFP-VHL into 786-O cells (supplemental Fig. S1B). Western blot analysis indicates that expression of wild-type VHL or EGFP-VHL, but not EGFP, inhibited FGFR1 and ERK1/2 activities in a dose-dependent manner, consistent with the changes observed in 786-VHL stable cells. No detectable changes in AKT or p38MAPK pathways were observed upon VHL or EGFP-VHL expression, consistent with a recent report (31). Furthermore, expression of EGFP or vector backbone did not alter the gene expression pattern examined here.

FIGURE 3. Prolonged accumulation of activated FGFR1 in VHL mutant cells.

786-O (A), 786-Vec (B), and 786-VHL cells (C), as described in the legend to Fig. 2A, were serum-starved for 6 h. Cells were fixed and stained for phosphorylated p-FGFR (indicating activation). 786-O (D), 786-Vec (E), and 786-VHL cells (F) were serum-starved for 12 h and then incubated with bFGF and heparin for 2 h at 4 °C. Cells were then shifted to 37 °C and processed for immunostaining for p-FGFR 5 min later. p-FGFR persists on the cell surface at 6 h after starvation in 786-O and 786-Vec cells (arrowheads in A and B), whereas in 786-VHL cells, very little p-FGFR1 is detected (C). The addition of bFGF plus heparin further increased surface p-FGFR level in 786-O and 786-Vec cells (arrowheads in D and E). In 786-VHL there is some induction of surface p-FGFR after bFGF plus heparin treatment, as expected (arrowhead in F). G, Western blot of extracts from 786-O, 786-EGFP, and 786-VHL cells. Total levels of FGFR1 are unchanged, whereas the activated FGFR1 (p-FGFR) levels are greatly reduced in 786-VHL cells. Activated ERK1/2 levels (doubly phosphorylated ERK1/2; dp-ERK1/2) show concomitant reduction in 786-VHL cells. p38 and AKT signaling are unchanged. 786-O and 786-EGFP cells show no difference in the proteins examined. H, Northern blot analysis showing no changes in FGFR1 mRNA levels upon VHL expression. β-Actin and total RNA are shown as loading and RNA quality controls.

FGFR1 and ERK Activities Regulate Cell Migration in VHL Mutant Cells

We then sought to verify the role of FGFR1 signaling in activating ERK signaling pathway and promoting cell migration. Two approaches were employed to block FGFR1 activity: 1) pharmaceutical inhibitor to FGFR1 and 2) dominant negative FGFR1. DMBI is a specific tyrosine kinase inhibitor of FGFR1 and PDGFR at ~25 μM and has been shown not to affect EGFR or Src even at >100 μM (32). Since DMBI can inhibit both FGFR1 and PDGFR, a PDGFR-specific inhibitor, PDGFR III, was used to further distinguish between FGFR1 and PDGFR signaling. PDGFR III is a selective inhibitor of the PDGFR family of tyrosine kinases (α-PDGFR, β-PDGFR, c-Kit, and Flt3) at low concentrations (< 2 μM) and inhibits EGFR, FGFR, Src, protein kinase A, and protein kinase C only at an IC50 value of ~30 μM (33). As controls, we show that DMBI can significantly inhibit ERK1/2 activity at 25 μM concentrations, whereas PDGFR III has no effect on ERK1/2 activity at concentrations close to its IC50 (supplemental Fig. S1C). Thus, it appears that FGFR1 is the major contributor to ERK1/2 signaling in VHL mutant cells. Indeed, the widely used ERK signaling inhibitor PD98059 can reduce the ERK1/2 activity to a similar extent as in DMBI-treated 786-O cells (supplemental Fig. S1C). Therefore, almost complete inhibition of cell migration in the Boyden chamber assays using DMBI suggests that FGFR signaling plays a prominent role in cell migration of 786-EGFP cells (Fig. 4A). Consistent with this, DMBI as well as the ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 blocked the two-dimensional migration of 786-EGFP cells in the wound-healing assay (Fig. 4B).

To further demonstrate the specific role of FGFR1 in conferring increased motility of VHL mutant cells, we examined the outcome of expressing a dominant negative form of human FGFR1 (amino acids 1–468; DN-FGFR1) that lacks the kinase domain (34, 35). To monitor transfection efficiency, the DN-FGFR1 was fused in frame to RFP (designated as DN-FGFR1-RFP). Using electroporation, we routinely achieved ~75% transfection efficiency. Control 786-O cells (minus plasmid) and 786-O cells transfected with the RFP vector were exposed to the same conditions as the DN-FGFR1-RFP-expressing cells. DN-FGFR1-RFP is detected by anti-FGFR1 antibody as a smaller protein species compared with endogenous FGFR1 (~12-kDa difference; Fig. 4C, top). Fig. 4C also shows that expression of DN-FGFR1-RFP significantly reduced the level of activated FGFR (p-FGFR) and resulted in a dramatic reduction in ERK1/2 activity (doubly phosphorylated ERK1/2). Consistent with our previous observations (Fig. 3G), AKT or p38MAPK activation was not influenced by expression of DN-FGFR-RFP. Chemotactic cell migration toward serum, assayed in Boyden chambers, also showed a significant reduction (~3-fold reduction; p < 0.005) upon expression of DN-FGFR-RFP (Fig. 4D). The combined results demonstrate that FGFR activity is a major source of ERK1/2 activation, and FGFR-ERK1/2 activity is a dominant chemotactic system in the VHL null cells.

HIF-independent Role of VHL

Having established the involvement of FGFR1, we tested whether loss of VHL function is directly responsible for increased FGFR1 activity and cell migration. For this purpose, three shRNAs specific for VHL were expressed in the VHL+ HEK293 cells. The U6 and CMV promoters drive the shRNA and EGFP expression, respectively; thus, EGFP was used as an internal control (Fig. 5A). Importantly, HEK293 was used as wild-type VHL cell line for the following reasons. 1) Endogenous wild-type VHL is expressed at quantifiable levels (supplemental Fig. S1A) (31). 2) Detectable expression of CXCR4, a direct target of HIF-2 in RCC cells (14), has been observed in HEK293 (36); it can serve as a marker for the VHL and HIF activity. 3) Low levels of FGFR1 are expressed, and the cells are efficiently stimulated by bFGF (37); thus, the specific effects of VHL knock-down on FGFR signaling can be observed unambiguously. 4) HEK293 cells possess a moderate capacity of chemotactic migration toward serum (38). Also, we expressed either wild type HIF-2α (HIF-2α (WT)) or a constitutively active HIF-2α (HIF-2α (P/A)) in order to delineate HIF-dependent and -independent roles of VHL. Note that HIF-2α is used here because it is the dominant α subunit expressed in some of the best studied RCC cells, including 786-O (39).

As shown in Fig. 5A, expression of VHL-shRNAs, but not control shRNA, resulted in a significant reduction in the VHL protein levels (compare lane 1 with lanes 2–4). Concomitant with reduction in VHL, CXCR4 levels increased, indicating specific effects of loss of VHL on previously established pathways (14). Importantly, expression of HIF-2α (WT) or HIF-2α (P/A) increased CXCR4 but not VHL protein levels.

Boyden chamber assays (Fig. 5B) showed significantly increased migration of VHL-shRNA-treated cells compared with control HEK293 cells (~2.5-fold; p < 0.005) and HIF-2α (WT)- or HIF-2α (P/A)-overexpressing cells (~6-fold, p < 0.005). In order to correlate cell motility with the FGFR1 activity, total FGFR1 was immunoprecipitated (due to low endogenous expression) from the transfected cells with rabbit polyclonal antibodies and detected using mouse monoclonal FGFR1 antibodies or phosphotyrosine antibodies (Tyr(P)-horseradish peroxidase) to estimate total or activated FGFR1 levels, respectively (Fig. 5A, bottom). There is no significant variation in total FGFR levels in control, VHL knock-down, and HIF-overexpressing cells. VHL knock-down resulted in significant increase in p-FGFR levels. Interestingly, overexpression of HIF-2α (WT) or HIF-2α (P/A) slightly reduced the activation of FGFR (see quantification below). The cause of this reduction is not known. Since 1) HIF-2α levels in the VHL knock-down cells are comparable with that in the HIF-overexpressing cells, and 2) the total FGFR level is not altered, the inhibitory effect is most likely indirect. At any rate, this observation also suggests that the increased p-FGFR level in VHL knockdown cells is independent of the HIF activity. To better gauge the level of FGFR activation, the relative FGFR1 activity is expressed as -fold activation (Tyr(P)-FGFR/total FGFR1), with the vector control set arbitrarily at 1 (Fig. 5B, line graph). VHL shRNA-treated cells exhibited ~3-fold or ~6-fold increased FGFR1 activity compared with control or HIF-2α-transfected cells, respectively. The level of FGFR activation correlates well with the cell motility. Thus, increased FGFR1 activity and cell motility phenotype of the VHL mutation is independent of the elevated HIF expression level. This is also supported by the observation that the FGFR1 protein and mRNA levels are unchanged in 786-O parental, 786-EGFP, and 786-VHL cells (Fig. 3, G and H). These results demonstrated that enhanced activity of FGFR1 in VHL mutant cells is not due to increased expression levels of FGFR1, either transcriptionally or post-transcriptionally.

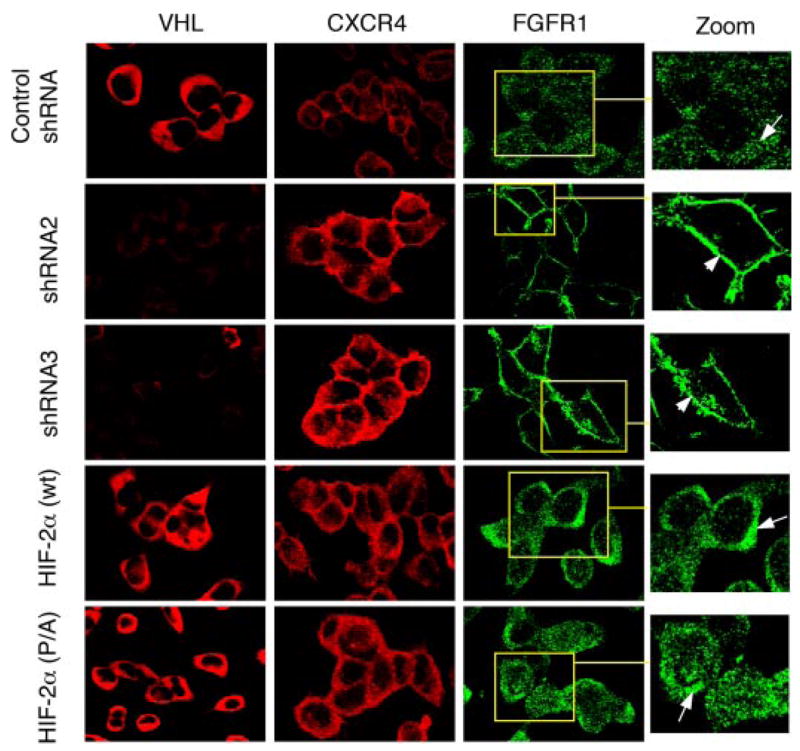

The effects of VHL knock-down and the irrelevance of HIF-α on FGFR1 surface accumulation were also directly visualized by immunostaining. As shown in Fig. 6, expression of VHL-specific shRNAs significantly knocked down VHL expression in HEK293 cells, which is correlated with increased FGFR1 surface accumulation and increased expression of CXCR4. Overexpression of either HIF-2α (WT) or HIF-2α (P/A) does not lead to FGFR1 surface accumulation, although they up-regulated CXCR4 expression.

FIGURE 6. HIF-independent surface accumulation of FGFR1 in HEK293 cells.

HEK293 cells transfected with the indicated plasmids (on the left) were stained with antibodies indicated at the top. Specific shRNA-mediated loss of VHL (second and third row; see also Fig. 5A) leads to increased surface accumulation of FGFR1 (arrowhead). FGFR1 in cells expressing control shRNA (top row) or HIF-2α (wild type or P/A; fourth and bottom rows) is localized in punctate structures that exhibited increased density toward the juxtanuclear region (arrows in insets). CXCR4, a positive control for HIF activity, is seen elevated in both VHL-shRNA-treated cells and HIF-2α-overexpressing cells but not in control shRNA-treated cells.

Taken together, the data presented so far confirmed that 1) surface accumulation of FGFR1 is linked to loss of VHL; 2) FGFR1 accumulation and increased migration phenotype occurs through an HIF-independent mechanism; and 3) increased cell migration due to loss of VHL correlates with elevated FGFR1 and ERK1/2 activities.

VHL Regulates Endocytosis of Activated FGF Receptors

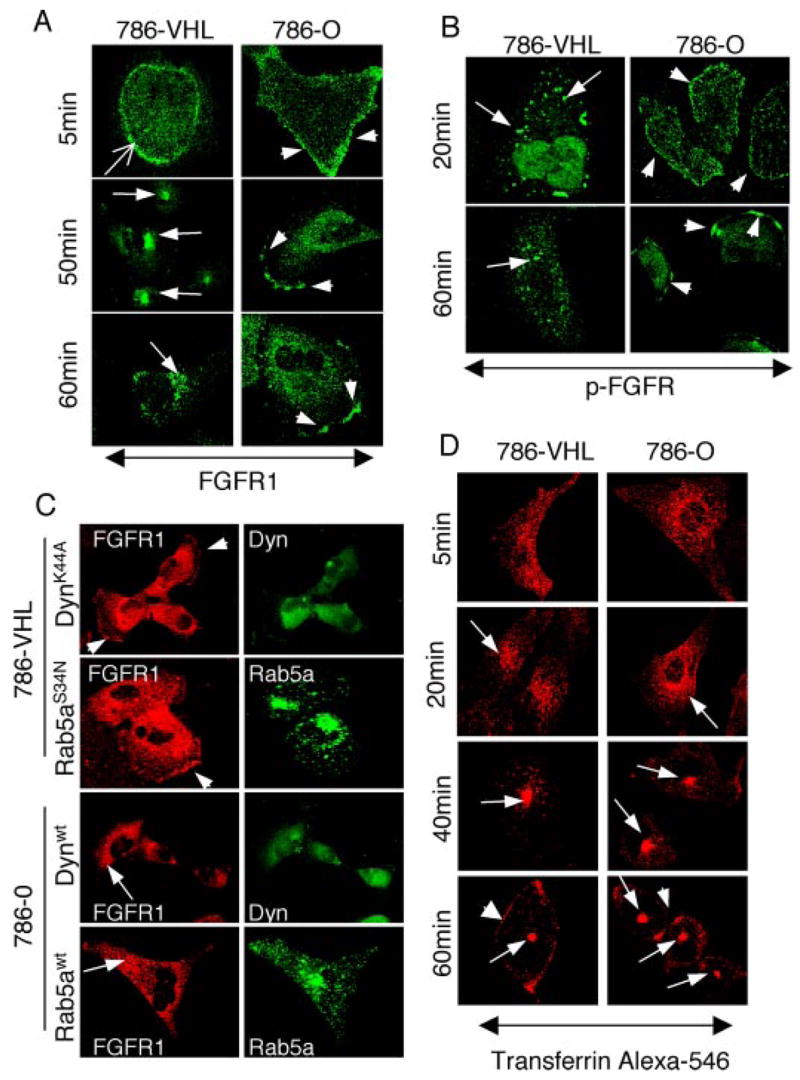

A defect in endocytosis of FGFR1 can result in surface retention, leading to increased cell migration and invasion in both humans and Drosophila (18, 40). To test if this is the case in VHL mutant cells, ligand-stimulated endocytosis of FGFR1 was synchronized and followed in 786-O and 786-VHL cells after a 24-h period of serum starvation. It should be noted that although FGFR1 is predominantly intracellular in 786-VHL cells under normal conditions, serum starvation leads to increased cell surface localization of FGFR1 (Fig. 3F). The internalization of FGFR1 was followed by incubation of serum-starved cells with bFGF plus heparin at 4 °C for 2 h and then chased with ligand-free medium at 37 °C over a 60-min period. In 786-VHL cells at 5 min after the initiation of chase, FGFR1 is detected just below the cell periphery (sharp arrow in Fig. 7A), consistent with the expectation that the ligand-bound FGFR1 is internalized. At 50–60 min, most of the internalized FGFR1 is localized to the perinuclear compartment (arrows in Fig. 7A). In contrast, high levels of FGFR1 remain on the cell surface at 5 min (arrowheads in Fig. 7A) in 786-O cells. Incredibly, the surface FGFR1 persists throughout the 60-min chase in 786-O cells and by 60 min progressively aggregates to distinct membrane patches, indicating defective internalization of FGFR1 in VHL mutant cells.

FIGURE 7. FGFR1 endocytosis defects in VHL null cells.

A and B, serum-starved cells were stimulated with bFGF and heparin. Ligand-induced endocytosis of FGFR1 was followed at 5-min intervals for 60 min. Representative time points are shown for brevity. A, 786-VHL cells (left columns) internalize (sharp arrow; 5 min) and target FGFR1 to juxtanuclear compartment (arrows; 50 and 60 min). In contrast, 786-O cells (right column) retain surface FGFR1 at 5 min (arrowhead) and exhibit progressive aggregation of FGFR1 to distinct membrane patches (arrowheads; 50 and 60 min). B, activated FGFR1 (p-FGFR) endocytosis was followed using an antibody that recognizes tyrosine-phosphorylated FGFR. 786-VHL cells (left columns) efficiently internalized activated FGFR1 (arrows; 20 min), and FGFR1 activity was gradually diminished to very weak signals (arrows; 60 min). In contrast, 786-O cells remained on the cell surface (arrowheads, right column; 20 min) and progressively aggregated to membrane patches (arrowheads; 60 min). C, 786-VHL or 786-O cells were transfected with the indicated dynamin 2-GFP or Rab5a-GFP constructs, treated with bFGF plus heparin, and double-stained for FGFR1 (red) and GFP (green). Cell surface accumulation of FGFR1 (arrowheads) is reproduced in 786-VHL cells (in ~75% transfected cells, n = 100) under normal serum conditions by expressing either dominant negative dynamin 2 (K44A) or dominant negative Rab5a (S34N). In addition, wild-type dynamin 2 or Rab5a can rescue the FGFR1 phenotype (in ~75% cells, n = 100) in 786-O cells. FGFR1 is now mostly cytoplasmic and more concentrated in the perinuclear region (arrows). D, 786-O or 786-VHL cells were incubated with transferrin-Alexa 546 at 4 °C, rinsed, and then incubated in prewarmed medium. TfR endocytosis was followed at various time points. No differences in transferrin internalization kinetics or its subcellular localization postinternalization was observed between 786-O and 786-VHL cells. The arrows follow the movement of transferrin-Alexa 546. The arrowheads in the 60-min panels point to TfRs that are recycled back to the surface.

To test if the endocytosis defect is reflected in an increased (or persistent) activity of FGFR1, a similar ligand-free chase was performed, and the cells were immunostained for activated FGFR1 using p-FGFR antibodies. At 20 min, internalized p-FGFR signals were observed in 786-VHL cells (arrows in Fig. 7B). By 60 min, only weak vesicle-associated p-FGFR signals could be detected, indicating attenuation of FGF receptor activity postinternalization. In contrast, p-FGFR in 786-O cells remained prominently on the cell surface at 20 min. By 60 min, the p-FGFR1 was localized in distinct cell surface aggregates, identical to the pattern observed with FGFR1 antibodies (arrowheads in Fig. 7B). Thus, VHL mutant cells exhibited defective internalization of FGFR1, leading to progressive membrane aggregation and persistent activation. Consistent with this, ectopic expression of dominant negative mutants of the endocytosis pathway components dynamin 2(K44A) and Rab5a(S34N) led to similar surface accumulation of FGFR1 in VHL(+) cells (Fig. 7C, 786-VHL). Conversely, overexpression of wild-type dynamin 2 and Rab5a partially rescued the surface accumulation of FGFR1 in VHL null 786-O cells (Fig. 7C).

To examine whether the FGFR1 accumulation phenotype is a result of a generalized defect in membrane receptor internalization in 786-O cells, we followed endocytosis of transferrin receptor (TfR) upon binding to AlexaFluor-conjugated transferrin (Fig. 7D). A previous report (41) observed increased TfR levels in 786-O cells, a target of HIF. However, as shown in Fig. 7D, there is no discernable difference in the kinetics of TfR internalization in 786-O and 786-VHL cells. Complete internalization occurred within 20 min in both cell types, and by 60 min transferrin was localized to the juxtanuclear compartment, whereas a small fraction was recycled back to the surface in both cell types (arrowheads in Fig. 7D).

Differential Abilities of VHL Disease Mutants in Reversing the FGFR1 Phenotype

Next, we sought to examine whether the FGFR1 endocytosis defect could be correlated with the known VHL mutations. Disease-causing VHL intragenic mutations are classified into four types (Types 1, 2A, 2B, and 2C) based on the associated tumor phenotype (2, 42, 43). Representative mutants from each class were expressed as EGFP fusions in the 786-O cells, and FGFR1 internalization followed at 50 min upon bFGF plus heparin stimulation. Specifically, we asked if the VHL role in FGFR1 endocytosis is linked to 1) its ability to regulate microtubule stability, 2) loss of HIF-α regulation, or 3) its property to bind fibronectin. Representative immunostaining of mutants from each class are shown in supplemental Fig. S2, and the results are summarized in Table 1. We made the following observations. First, Y98H, a β-domain mutant that is unable to restore microtubule stability (44) efficiently restored FGFR1 internalization. Second, we did not find a clear correlation between loss of HIF-α regulation and the FGFR1 phenotype (Table 1). For example, among the mutants that exhibit complete or partial loss of HIF-α regulation (del Exon2, S65L, S65W, Y98H, C162F, P154L and R167Q), S65L, Y98H, and P154L completely restored FGFR1 internalization, whereas S65W partially rescued and three mutants (del Exon2, C162F, and R167Q) failed to show rescue of the phenotype. The R64P and L188V mutants, associated with Type 2C phenotype and known to retain substantial HIF-α regulation, could partially restore FGFR1 internalization. Third, since all VHL mutants examined here are defective in fibronectin assembly (43, 45), the FGFR1 phenotype also does not correlate with failure to bind fibronectin.

TABLE 1. FGFR1 localization in VHL disease mutants.

| Plasmid in 786-O cells | Mutation | Disease phenotypea | Surface FGFR1b | HIF degradation/ubiquitinationc | Elongin C binding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFP | Null | ++ (no rescue) | − | − | |

| EGFP-VHL | Wild type | − (rescue) | ++ | + | |

| Del Ex-2 | Type 1 | HAB, RCC, rare PHE | ++ (no rescue) | − | − |

| S65L | Type 1 | HAB, RCC, rare PHE | − (rescue) | − | + |

| S65W | Type 1 | HAB, RCC, rare PHE | + (partial rescue) | − | + |

| C162F | Type 1 | HAB, RCC, rare PHE | ++ (no rescue) | − | − |

| Y98H | Type 2A | HAB, PHE, rare RCC | − (rescue) | +/− | + |

| R167Q | Type 2B | HAB, RCC, PHE | ++ (no rescue) | +/− | − |

| P154L | Type 2A/B | HAB, PHE, rare RCC | + (rescue) | − | + |

| R64P | Type 2C | PHE only | + (partial rescue) | ++ | + |

| L188V | Type 2C | PHE only | + (partial rescue) | ++ | + |

HAB, hemangioblastoma; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; PHE, pheochromocytoma.

++ (no rescue), surface FGFR1 observed in >75% of the cells; + (partial rescue), surface FGFR1 observed in >25% of the cells; − (rescue), no surface FGFR1 observed in the transfected cells.

+/−, different studies show weakly positive or negative results, depending on the assay conditions or the HIF-α species examined (i.e. 1α or 2α).

In summary, the FGFR1 phenotype appears to involve a novel VHL function that did not correlate with the current pathological and cellular classifications of the VHL protein. We do note some correlation between the strong FGFR1 accumulation phenotype and loss of elongin C binding activity. This may indicate either the involvement of the elongin C-binding domain of VHL in regulating FGFR1 endocytosis or that VHL-elongin C complex itself is directly involved. However, since the strong elongin C binder R64P and L188V can only partially rescue the phenotype, this correlation requires further investigation.

VHL Associates with FGFR1-containing Endosomes

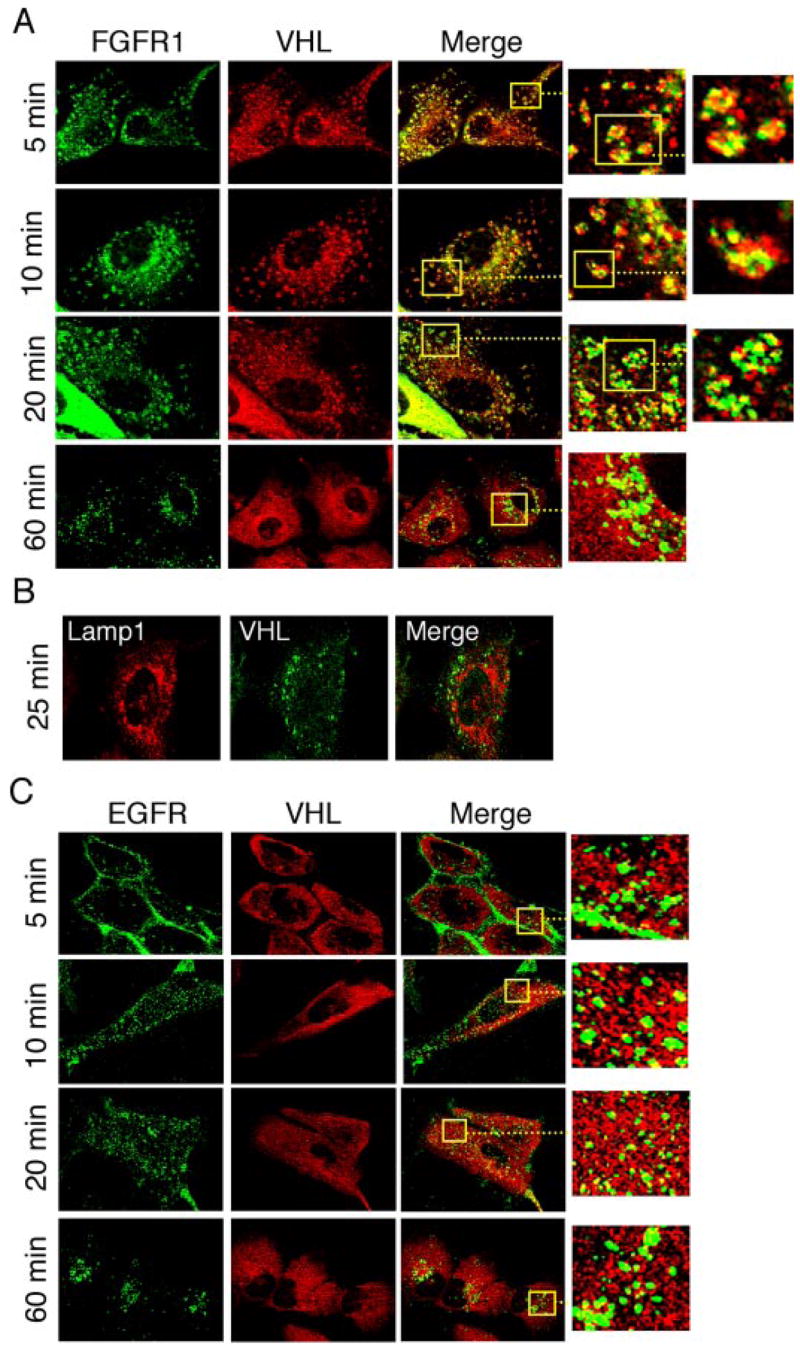

The differential rescue by VHL mutants demonstrated a specific functional requirement of VHL activity in FGFR1 endocytosis. A possibility that this VHL function may involve modulating the activity of known regulators of endocytosis was apparent by rescue of FGFR1 accumulation phenotype by wild-type dynamin 2 or Rab5a overexpression. Many proteins that regulate endocytosis and the signaling output of receptor tyrosine kinases are recruited to endosomes and are observed to occupy a mosaic, non-random pattern of distribution on the endosome (46). Assembly of such proteins onto endosomes is critical for the formation and maturation of endosomes from the plasma membrane (47). To test whether VHL is indeed localized to endosomes, we followed ligand-induced internalization of FGFR1 in 786-VHL cells and examined the intracellular localization of VHL during this process. Interestingly, VHL is found intimately associated with FGFR1-containing endosomes at early stages of endocytosis (Fig. 8A, insets) until a step prior to lysosomal delivery of FGFR1 (Fig. 9A, 10–20 min). VHL is much less abundant in FGFR1-containing vesicles near the nucleus at 20 min (enlarged view), suggesting that VHL is not involved in late endosome-lysosome functions. Indeed, VHL was not detectable in FGFR1-containing vesicles at a later time point (Fig. 8A, 60 min) or in Lamp-1-positive vesicles (Fig. 8B), indicating dissociation of VHL prior to lysosomal delivery of internalized FGFR1. VHL is present in a punctate mosaic pattern similar to the observed pattern for the endosome-associated protein Rab5a (48). Moreover, VHL and FGFR1 occupied different microdomains (Fig. 8A, enlarged views), suggesting a regulatory role for VHL that does not require direct binding to FGFR1 within the endosomes. To further confirm that the VHL-FGFR1 functional relationship is selective, we performed a similar endocytosis chase experiment for EGFR. As shown in Fig. 8C, upon EGF stimulation, EGFR is readily internalized and targeted to the perinuclear compartment within 60 min. Throughout this endocytic process, VHL is never associated with EGFR-containing vesicles (Fig. 8C, insets).

FIGURE 8. Involvement of VHL in FGFR1 endocytosis.

A, endocytosis was followed in 786-VHL cells upon bFGF plus heparin stimulation, and cells were double-stained for VHL (red) and FGFR1 (green) at the indicated time after ligand-free medium chase. The association of VHL with bFGF-stimulated endosomes lasted until a step prior to lysosomal delivery (~25 min). The insets and further enlarged views show individual endosomes with VHL and FGFR1 occupying different domains within the vesicles. B, the same endocytosis chase as in A, but cells were double-stained for VHL (green) and Lamp-1 (red), a lysosomal marker. Only the 25-min time point is shown. VHL is not present in the lysosomes. C, endocytosis was visualized following EGF stimulation, and cells were double-stained for VHL (red) and EGFR (green) at indicated times after ligand-free medium chase. VHL is not present in EGFR-containing endosomes at any time during the endocytosis (see insets).

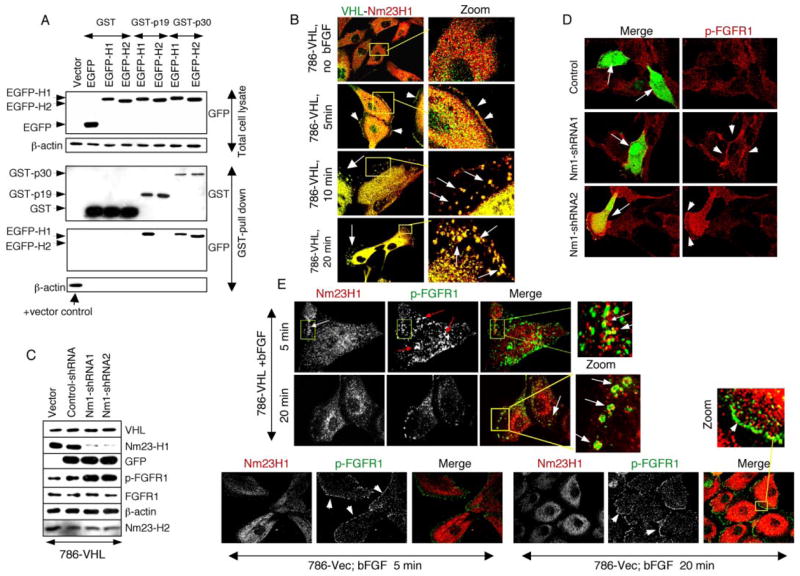

FIGURE 9. VHL and Nm23 cooperate in FGFR endocytosis.

A, HEK293 cells were doubly transfected with GST fusions of VHL isoforms (p30 or p19) and EGFP fusions of Nm23 isoforms (H1 or H2). Proteins from total lysates were subjected to Western blot with anti-GFP antibodies for EGFP-Nm23 expression (top). EGFP-H1 and EGFP-H2 can be distinguished by the slightly different migration. Equal amounts of lysates were pulled down using glutathione beads (for the GST fusion proteins), and the eluates were subjected to Western blot with anti-GST antibodies to detect the captured GST fusions and anti-GFP antibodies to detect EGFP-Nm23. The bottom panel shows β-actin in the GST pull-down eluates as negative controls and with total lysate from the vector transfection as a positive control (arrow), verifying the quality and specificity of the pull-down assay. B, 786-VHL cells were serum-starved, treated with bFGF plus heparin at 4 °C, rinsed, chased with serum-free medium at 37 °C for the indicated time (5–20 min), and double-stained for VHL (green) and Nm23H1 (red). Without bFGF treatment, VHL and Nm23H1 are dispersed throughout the cell body. At 5 min after ligand-induced endocytosis, both VHL and Nm23H1 are present at the cell periphery (arrowheads). At 10 –20 min after the chase, VHL and Nm23H1 are extensively co-localized in the endocytic vesicles (arrows). C, 786-VHL cells were transfected with pCMV vector alone or pCMV-EGFP vector containing U6 promoter cassette expressing control shRNA or one of the two Nm23H1-specific shRNAs. Equal amounts of lysates, indicated by equal β-actin, VHL, and Nm23H2, were subjected to Western blot for the proteins indicated on the right. Knock-down of Nm23H1 is correlated with increased levels of p-FGFR1, whereas total FGFR1 is not affected. D, 786-VHL cells were transiently transfected with plasmids expressing control shRNA or one of the two Nm23H1-specific shRNA as in C and 48 h later were serum-starved for 12 h, bFGF plus heparin-stimulated at 37 °C for 5 min, and double-stained for EGFP and p-FGFR. Transfected cells were recognized by EGFP expression (arrows). Compared with control shRNA or untransfected cells, Nm23H1 shRNA expression resulted in significantly enhanced FGFR1 activity (arrowheads). E, 786-vector and 786-VHL cells were starved, bFGF-treated, and chased with serum-free medium as in B. The cells were then double-stained for p-FGFR (green) and Nm23H1 (red) at the indicated time points. In 786-VHL cells, Nm23H1 localizes with p-FGFR in the endocytic vesicles, but the two proteins occupy different domains (Zoom). In 786-Vec cells (VHL null), Nm23H1 is never localized at membrane domains occupied by p-FGFR even at prolonged observation periods.

VHL Regulates FGFR1 Internalization via Nm23H1

Finally, we sought to identify the mechanism of VHL-mediated FGFR1 endocytosis. In a yeast two-hybrid screen, we had identified the metastasis suppressor Nm23 as a strong VHL-interacting protein.4 To verify the results in human cells, GST and EGFP fusions of VHL and Nm23H1/H2, respectively, were co-expressed in HEK293 cells, and the interaction was studied by GST pull-down assays (Fig. 9A). Since VHL p19 isoform (a shorter alternate translation initiation product) exhibits tumor suppressor activity (49), both p19 and p30 (full-length isoform) were tested in this assay. Whereas p30 bound both Nm23H1 and Nm23H2 upon serum stimulation, p19 showed interaction with only Nm23H1 (Fig. 9A). To test the relevance, we examined the behavior of VHL and Nm23H1 during FGFR1 endocytosis in 786-VHL cells (Fig. 9B). In serum-starved 786-VHL cells, VHL and Nm23H1 were dispersed throughout the cell body. At 5 min of bFGF stimulation, detectable fractions of both VHL and Nm23H1 were recruited to the cell periphery. At 10–20 min, VHL and Nm23H1 were found extensively co-localized within endocytic vesicles, suggesting dynamic assembly of VHL and Nm23H1. To directly test the functional partnership between VHL and Nm23H1 in FGFR1 pathway, we constructed two shRNAs for Nm23H1 (Figs. 9C) and studied the influence of loss of Nm23H1 in 786-VHL cells. Indeed, specific loss of Nm23H1 led to a dramatic increase in FGFR1 surface accumulation (data not shown) and activity (Fig. 9, C and D) even in the presence of wild type VHL (in 786-VHL cells), suggesting that Nm23H1 activity is required by VHL to prevent surface accumulation and abnormal activation of FGFR1.

We also determined that the protein levels of Nm23H1, Nm23H2, dynamin 2, and Rab5a are not altered in VHL+ and VHL mutant cells (data not shown). Having established the functional partnership between VHL and Nm23H1 in FGFR1 endocytosis (Fig. 9, A–D), we next examined the distribution of Nm23H1 during FGFR1 endocytosis in VHL+ and VHL mutant cells (Fig. 9E). In 786-VHL cells at 5 min after ligand-induced endocytosis, Nm23H1 and p-FGFR were localized within endocytic vesicles but occupying different domains, similar to what was observed for VHL and FGFR1 (Fig. 8A). At 20 min, Nm23H1 remained localized in p-FGFR-containing endosomes, but with reduced presence (Fig. 9E), again reminiscent of the VHL and FGFR localization pattern at this time point (Fig. 8A). By contrast, in the absence of VHL (786-Vec), endogenous Nm23H1 was unable to translocate to the cell periphery (where activated FGFR1 was seen) even at prolonged periods of observation (Fig. 9E). These observations support a model in which, during FGFR1 endocytosis, VHL binds to and translocates Nm23H1 to the cell periphery to stimulate dynamin-mediated vesicle formation and release from the plasma membrane. Additionally, the identical pattern of temporal reductions in VHL and Nm23H1 (5–20-min endocytosis) and complete co-localization of the two proteins within the endosomes suggest that VHL is required for transient assembly of Nm23H1, and this recruitment might regulate normal maturation of endosomes. In conclusion, the FGFR1 accumulation and increased migration phenotype in VHL null cells is a direct result of loss of VHL-mediated recruitment of Nm23H1 at cellular sites involved in FGFR1 internalization.

DISCUSSION

Pleiotropic Functions of VHL

Our interest in VHL-regulated cell migration stems from our earlier observations that loss of function of the Drosophila VHL homolog resulted in ectopic migration and branching of Drosophila tracheal cells (27). Since Drosophila tracheal cells do not proliferate, a direct role of VHL in modulating cell motility in vivo is implicated. It has been well documented that in VHL mutant RCCs, HIF-α subunits are stabilized, leading to production of proangiogenic factors and a switch to the glycolysis pathway (50). It is also evident from the extensive literature that VHL has multiple cellular functions. For example, VHL binds to microtubules, conferring resistance to microtubule-destabilizing drugs (44). VHL mutant cells also showed defects in exiting cell cycle upon serum withdrawal (51). Later studies linked this phenotype to altered cell-matrix interaction (16). Indeed, a series of elegant studies indicated defects in assembly of fibronectin (45, 52) and β1-integrin-anchored adhesions (12) in VHL mutants. These defects correlated with another well documented but little understood VHL mutant phenotype of increased cell motility (11, 13, 15–17). These findings strongly suggest that VHL has cellular functions that are distinct from its role as an ubiquitin E3 ligase targeting HIF-α.

Membrane Accumulation of FGFR1

In this report, we show that VHL null cells exhibit elevated motility and that the phenotype is a direct consequence of cell surface accumulation of FGFR1 and enhanced signaling via ERK1/2. This is demonstrated by re-expressing VHL in 786-O cells, by RNA interference-mediated knock-down of endogenous VHL in HEK293 cells, and by blocking FGFR1-ERK1/2 signaling using pharmaceuticals or dominant-negative FGFR1 mutant.

Elevated FGFR1 signaling due to overexpression (53) or decreased endocytosis (18, 40) has been linked with highly invasive behavior. In our analysis of disease-related VHL mutations, two point mutants, C162F and R167Q, that failed to restore internalization of FGFR1 are mutation hot spots and are associated with high risk of developing multiple lesions including RCC, the most aggressive among VHL tumors (2, 42, 43, 54). On the other hand, we find no consistent correlation between the ability to promote FGFR1 internalization and current classification of disease-related VHL mutations (i.e. FGFR surface accumulation can be rescued by mutations in each of the disease subtype) (Table 1). There is a potential correlation between mutants that show strong FGFR1 accumulation phenotype (del Exon2, C162F, and R167Q) and loss of elongin C binding capability (Table 1). However, this correlation requires further confirmation by examining more VHL mutants.

In this light, it is noteworthy that the FGFR1 localization and high motility phenotypes appear to be independent of the well known VHL function of down-regulating HIF-α. We show that ectopic expression of wild-type HIF-2αand constitutively stable HIF-2α (P/A) does not confer the VHL+ cells these phenotypes (Figs. 5 and 6). This conclusion is also supported by the results that show no increase of FGFR1 transcript or protein levels in the VHL mutant cells (Figs. 2C, 3H, and 5) and by our observation that inhibitors of HIF prolyl hydroxylases, such as dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG) and ethyl 3,4-dihydroxybenzoate (EDHB) (55, 56), failed to generate migration phenotypes in VHL+ cells (data not shown).

VHL Regulates Endocytosis of FGFR1

The effect of VHL mutation on FGFR1 accumulation is specific, since other surface proteins such as EGFR, IGFR1 c-Met, PDGFR, and N-cadherin do not overaccumulate on the cell surface in VHL mutants (Fig. 2). We demonstrate that surface accumulation of FGFR1 is correlated with defects in internalization by endocytosis (Fig. 7, A and B). However, endocytosis of TfR (Fig. 7D) is not affected. Most interestingly, we observed co-localization of VHL with FGFR1 in different domains of endosomes (Fig. 8A), but not with EGFR (Fig. 8C). This association is restricted to early endosomes, since no VHL is detected with FGFR1 in the later stage of endocytosis (Fig. 8B). The observed recruitment of VHL to FGFR1 pathway and not the EGFR pathway may be due to the underlying differences in assembly of signaling components between the two receptors. It is noteworthy that phosphorylated EGFR can itself serve as ascaffold for assembling the endocytic components (57), whereas FRS2 (FGFR substrate 2) recruits most of the components necessary for FGFR1 signaling and regulation (58).

We provide evidence that the endocytic function of VHL is mediated via the metastasis suppressor Nm23. We show that VHL and Nm23 isoforms form complex in cells and that both VHL and Nm23H1 are integral components of FGFR1 endocytosis machinery. This finding is highly significant, because promoting endocytosis is an evolutionarily conserved function of Nm23 (18–21, 59). Nm23, as a GTP supplier, stimulates endocytosis via locally modulating dynamin assembly and activity (18, 21). However, unlike dynamin, Nm23 is not a general regulator of endocytosis (18). In this respect, how Nm23 activity is restricted to a limited subset of endocytic pathways has been an important question. Combined with an earlier report of ARF6-mediated assembly of Nm23H1 in E-cadherin endocytosis (19), our observation of VHL-mediated recruitment of Nm23H1 to FGFR1 endocytosis represents a crucial cellular mechanism of regulated utilization of Nm23H1 endocytic activity in specific pathways. In particular, the Nm23 endocytic activity in promoting internalization of FGFR has been shown to regulate developmentally programmed epithelial cell migration in the Drosophila tracheal system (18). Interestingly, the tracheal phenotype due to loss-of-function Drosophila VHL mutant (27) phenocopy Nm23 knock-out mutants (18), suggesting that the functional relationship between VHL and Nm23 might be evolutionarily conserved and relevant during development. Our data presented here indicate that VHL is required for recruitment of Nm23 to the FGFR-containing endosomes and that Nm23 is required for the VHL-induced FGFR internalization. The exact nature of this functional relationship between Nm23 and VHL thus warrants further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the following for generous gifts of plasmids: W. G. Kaelin (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) for a subset of VHL mutants and HIF-2α, G. R. Guy (Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Singapore) for FGFR1 plasmid, N. W. Bunnett (University of California, San Francisco, CA) for Rab5a-GFP constructs, and S. L. Schmid (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA) for dynamin 2-GFP constructs.

Footnotes

This work was initially supported by the VHL Family Alliance (to T. H.) and subsequently by National Institutes of Health Grants PO1CA78582 and RO1CA109860 (to T. H.) and a Medical University of South Carolina/Department of Defense phase VII (Geocenters) grant (to V. D.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

The abbreviations used are: E3, ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; FGFR, FGF receptor; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; PDGFR III, 4-(6,7-dimethoxy-4-quinazolinyl)-N-(4-phenoxyphenyl)-1-piperazinecarboxamide; DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; CMV, cytomegalovirus; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; GST, glutathione S-transferase; MTC, mitomycin C; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; p-FGFR, phospho-FGFR; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; DMBI, 3-(4-dimethylaminobenzylidenyl)-2-indolinone; DN-FGFR1, dominant negative FGFR1; TfR, transferrin receptor.

V. Dammai and T. Hsu, unpublished observations.

References

- 1.Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, Chew EY, Libutti SK, Linehan WM, Oldfield EH. Lancet. 2003;361:2059–2067. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13643-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim WY, Kaelin WG. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4991–5004. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Latif F, Tory K, Gnarra J, Yao M, Duh FM, Orcutt ML, Stackhouse T, Kuzmin I, Modi W, Geil L. Science. 1993;260:1317–1320. doi: 10.1126/science.8493574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwai K, Yamanaka K, Kamura T, Minato N, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Klausner RD, Pause A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12436–12441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamura T, Conrad MN, Yan Q, Conaway RC, Conaway JW. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2928–2933. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamura T, Sato S, Iwai K, Czyzyk-Krzeska M, Conaway RC, Conaway JW. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10430–10435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190332597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krieg M, Haas R, Brauch H, Acker T, Flamme I, Plate KH. Oncogene. 2000;19:5435–5443. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maynard MA, Qi H, Chung J, Lee EH, Kondo Y, Hara S, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Ohh M. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11032–11040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maynard MA, Ohh M. Am J Nephrol. 2004;24:1–13. doi: 10.1159/000075346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruick RK. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2614–2623. doi: 10.1101/gad.1145503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamada M, Suzuki K, Kato Y, Okuda H, Shuin T. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4184–4189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esteban-Barragan MA, Avila P, Alvarez-Tejado M, Gutierrez MD, Garcia-Pardo A, Sanchez-Madrid F, Landazuri MO. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2929–2936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koochekpour S, Jeffers M, Wang PH, Gong C, Taylor GA, Roessler LM, Stearman R, Vasselli JR, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Kaelin WG, Jr, Linehan WM, Klausner RD, Gnarra JR, Vande Woude GF. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5902–5912. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Staller P, Sulitkova J, Lisztwan J, Moch H, Oakeley EJ, Krek W. Nature. 2003;425:307–311. doi: 10.1038/nature01874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lieubeau-Teillet B, Rak J, Jothy S, Iliopoulos O, Kaelin W, Kerbel RS. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4957–4962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidowitz EJ, Schoenfeld AR, Burk RD. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:865–874. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.865-874.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis MD, Roberts BJ. Oncogene. 2003;22:3992–3997. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dammai V, Adryan B, Lavenburg KR, Hsu T. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2812–2824. doi: 10.1101/gad.1096903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palacios F, Schweitzer JK, Boshans RL, D’Souza-Schorey C. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:929–936. doi: 10.1038/ncb881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deitcher D. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:625–626. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01927-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krishnan KS, Rikhy R, Rao S, Shivalkar M, Mosko M, Narayanan R, Etter P, Estes PS, Ramaswami M. Neuron. 2001;30:197–210. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adereth Y, Champion KJ, Hsu T, Dammai V. BioTechniques. 2005;38:864–868. doi: 10.2144/05386BM03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wykoff CC, Sotiriou C, Cockman ME, Ratcliffe PJ, Maxwell P, Liu E, Harris AL. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1235–1243. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Corte V, Van Impe K, Bruyneel E, Boucherie C, Mareel M, Vandekerckhove J, Gettemans J. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5283–5292. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuchs M, Hutzler P, Handschuh G, Hermannstadter C, Brunner I, Hofler H, Luber B. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2004;59:50–61. doi: 10.1002/cm.20019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miura Y, Yanagihara N, Imamura H, Kaida M, Moriwaki M, Shiraki K, Miki T. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2003;47:268–275. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(03)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adryan B, Decker HJ, Papas TS, Hsu T. Oncogene. 2000;19:2803–2811. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knebelmann B, Ananth S, Cohen HT, Sukhatme VP. Cancer Res. 1998;58:226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verveer PJ, Wouters FS, Reynolds AR, Bastiaens PI. Science. 2000;290:1567–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawano A, Takayama S, Matsuda M, Miyawaki A. Dev Cell. 2002;3:245–257. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gemmill RM, Zhou M, Costa L, Korch C, Bukowski RM, Drabkin HA. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:2266–2277. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaman GJ, Vink PM, van den Doelen AA, Veeneman GH, Theunissen HJ. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00271-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuno K, Ushiki J, Seishi T, Ichimura M, Giese NA, Yu JC, Takahashi S, Oda S, Nomoto Y. J Med Chem. 2003;46:4910–4925. doi: 10.1021/jm020505v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bellot F, Crumley G, Kaplow JM, Schlessinger J, Jaye M, Dionne CA. EMBO J. 1991;10:2849–2854. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ueno H, Gunn M, Dell K, Tseng A, Jr, Williams L. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1470–1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ueda H, Howard OM, Grimm MC, Su SB, Gong W, Evans G, Ruscetti FW, Oppenheim JJ, Wang JM. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:804–812. doi: 10.1172/JCI3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reilly JF, Mizukoshi E, Maher PA. DNA Cell Biol. 2004;23:538–548. doi: 10.1089/dna.2004.23.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen H, Lo SH. Biochem J. 2003;370:1039–1045. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kondo K, Klco J, Nakamura E, Lechpammer M, Kaelin WG., Jr Cancer Cell. 2002;1:237–246. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suyama K, Shapiro I, Guttman M, Hazan RB. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:301–314. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alberghini A, Recalcati S, Tacchini L, Santambrogio P, Campanella A, Cairo G. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30120–30128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500971200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clifford SC, Cockman ME, Smallwood AC, Mole DR, Woodward ER, Maxwell PH, Ratcliffe PJ, Maher ER. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1029–1038. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.10.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffman MA, Ohh M, Yang H, Klco JM, Ivan M, Kaelin WG., Jr Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1019–1027. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.10.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hergovich A, Lisztwan J, Barry R, Ballschmieter P, Krek W. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:64–70. doi: 10.1038/ncb899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohh M, Yauch RL, Lonergan KM, Whaley JM, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Louis DN, Gavin BJ, Kley N, Kaelin WG, Jr, Iliopoulos O. Mol Cell. 1998;1:959–968. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miaczynska M, Pelkmans L, Zerial M. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Le Roy C, Wrana JL. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:112–126. doi: 10.1038/nrm1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duclos S, Corsini R, Desjardins M. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:907–918. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blankenship C, Naglich JG, Whaley JM, Seizinger B, Kley N. Oncogene. 1999;18:1529–1535. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Unwin RD, Craven RA, Harnden P, Hanrahan S, Totty N, Knowles M, Eardley I, Selby PJ, Banks RE. Proteomics. 2003;3:1620–1632. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pause A, Lee S, Lonergan KM, Klausner RD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:993–998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stickle NH, Chung J, Klco JM, Hill RP, Kaelin WG, Jr, Ohh M. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3251–3261. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.8.3251-3261.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eswarakumar VP, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zbar B, Kishida T, Chen F, Schmidt L, Maher ER, Richards FM, Crossey PA, Webster AR, Affara NA, Ferguson-Smith MA, Brauch H, Glavac D, Neumann HP, Tisherman S, Mulvihill JJ, Gross DJ, Shuin T, Whaley J, Seizinger B, Kley N, Olschwang S, Boisson C, Richard S, Lips CH, Lerman M. Hum Mutat. 1996;8:348–357. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1996)8:4<348::AID-HUMU8>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, Kriegsheim A, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Science. 2001;292:468–472. doi: 10.1126/science.1059796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wright G, Higgin JJ, Raines RT, Steenbergen C, Murphy E. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20235–20239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sorkin A. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:480–484. doi: 10.1042/bst0290480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schlessinger J. Science. 2004;306:1506–1507. doi: 10.1126/science.1105396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rochdi MD, Laroche G, Dupre E, Giguere P, Lebel A, Watier V, Hamelin E, Lepine MC, Dupuis G, Parent JL. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18981–18989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312621200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Corn PG, McDonald ER, 3rd, Herman JG, El-Deiry WS. Nat Genet. 2003;35:229–237. doi: 10.1038/ng1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rathmell WK, Hickey MM, Bezman NA, Chmielecki CA, Carraway NC, Simon MC. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8595–8603. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.