Abstract

One of the many obstacles to spinal cord repair following trauma is the formation of a cyst that impedes axonal regeneration. Accordingly, we examined the potential use of electrospinning to engineer an implantable polarized matrix for axonal guidance. Polydioxanone, a resorbable material, was electrospun to fabricate matrices possessing either aligned or randomly oriented fibers. To assess the extent to which fiber alignment influences directional neuritic outgrowth, rat dorsal root ganglia (DRGs) were cultured on these matrices for 10 days. Using confocal microscopy, neurites displayed a directional growth that mimicked the fiber alignment of the underlying matrix. Because these matrices are generated from a material that degrades with time, we next determined whether a glial substrate might provide a more stable interface between the resorbable matrix and the outgrowing axons. Astrocytes seeded onto either aligned or random matrices displayed a directional growth pattern similar to that of the underlying matrix. Moreover, these glia-seeded matrices, once co-cultured with DRGs, conferred the matrix alignment to and enhanced outgrowth exuberance of the extending neurites. These experiments demonstrate the potential for electrospinning to generate an aligned matrix that influences both the directionality and growth dynamics of DRG neurites.

Keywords: Electrospinning, matrix, dorsal root ganglion, astrocyte, spinal cord injury

INTRODUCTION

Percussive injury to the spinal cord, in both human insults and animal models, results in the liquefactive necrosis of the tissue in and around the lesion site. Commonly, a fluid-filled cyst is the final consequence of this process (Balentine, 1978; Wozniewicz et al., 1983; Kakulas, 1984; Bresnahan et al., 1991; Bunge et al., 1993; Ito et al., 1997; Norenburg et al., 2004). Because of the lack of a solid substrate, this late-stage pathological endpoint represents a physical gap that impedes axonal regeneration and functional recovery (Guth et al., 1985; Basso et al., 1996; Beattie et al., 1997). To guide regenerating axons across this cavity, several research groups have investigated the use of bridging materials that include substrates derived from either stem cells (McDonald et al., 1999; Akiyama et al., 2002), support cells (Xu et al., 1995; Li et al., 1997), autologous grafts (von Wild and Brunelli, 2003; Houle et al., 2006), embryonic grafts (Reier et al., 1986), natural substances (Marchand et al., 1993), or synthetic substances (Tsai et al., 2004; Wen and Tresco, 2006). Many of these approaches have shown promise in attracting regenerating axons onto the prosthetic bridge. However, documented cases of axons traversing these conduits to reach the intact tissue on the opposite margin of the lesion area are rare. Consequently, successes in inducing axonal regeneration have not translated into appreciable recovery of function. Nevertheless, despite the failure of significant neuritic regrowth on existing bridges, advances in generating conduits for growth across lesioned areas must be made to successfully restore function after spinal cord injuries (SCI).

In a simplified view, an ideal bridging neural conduit would be made from a biocompatible material that contains either channels or fibers that spatially guide regenerating axons. Since damage to the spinal cord induces necrosis that frequently affects multiple fiber tract systems, this bridge should fill the extent of the cyst area. Additionally, it should have a level of porosity that allows the inward migration and incorporation of supportive cells as well as the traversing axons. Finally, the ideal bridge should have the capacity to deliver signaling factors in a controlled manner to aid in the attraction, directional growth and viability of traversing regenerating axons. One technique that has the capacity to generate such an ideal bridging prosthesis is electrospinning. Similar in concept to electrospraying, electrospinning uses a high-voltage electric field to generate extremely fine fibers that are deposited on a grounded collector to form a non-woven mat (Bowlin et al., 2002). Chemically, these mats can be electrospun from either extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins or synthetic polymers, both of which can be spun alone or in combination with other growth-promoting factors. Physical properties of these matrices, such as fiber diameter, porosity and alignment can also be controlled (Fridrikh et al., 2003). In the field of tissue engineering, the application of this technique has resulted in the generation of several biocompatible substrates such as growth-promoting dermal implants, cardiac patches and synthetic vessels (Stitzel et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2005). For example, studies show that interstitial fibroblasts and endothelial cells migrate readily into an implanted electrospun collagen matrix from surrounding tissue (Telemeco et al., 2005). Once there, these cells proliferate and actively remodel this biological substrate, resulting in accelerated wound repair with less contracture. More recently, electrospinning has been used to generate growth matrices for cortical stem cells (Yang et al., 2005). Collectively, these studies indicate the potential utility of electrospining to create biocompatible substrates for use in injury repair.

OBJECTIVE

In the present study we have examined the potential use of electrospinning to engineer a polarized matrix for axonal guidance. This matrix, which was spun from the resorbable suture material, polydioxanone (PDS), was tested for biocompatility with cells of neuronal and glial origin, and the growth dynamics of these cells on the matrix were assessed in cell culture studies. These experiments demonstrate that both the directionality and exuberance of axonal growth are controlled significantly by the physical and chemical properties of the underlying electrospun substrate. Controlling these two parameters of axonal growth are prerequisites to establishing a successful strategy for bridging lesioned areas in SCI.

METHODS

Electrospinning

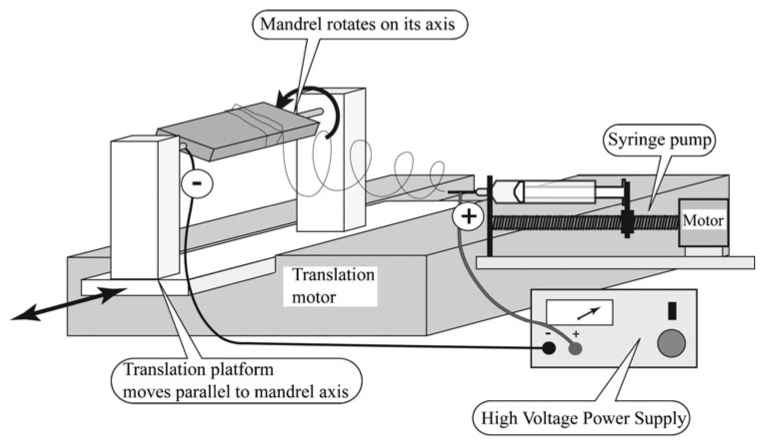

Electrospun matrices were fabricated from the PDS II violet monofilament surgical suture (Ethicon) as described previously (Boland et al., 2005). Briefly, for each matrix, 300 mg of 10% weight/volume of cut PDS filament was dissolved overnight in the solvent 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (Sigma-Aldrich). The solution was then transferred to a 5-ml syringe tipped with an 18-gauge blunt-end needle (Kontes) and the syringe mounted onto a syringe pump set at a delivery rate of ~30 ml hr−1 (KD Scientific 100). The needle was connected to the anode of a high voltage DC power supply (Spellman CZE1000R) via a wire outfitted with an alligator clip. The grounded rectangular mandrel, with a cross-section of 10 × 3 mm, was placed 20 cm from the needle (Fig. 1). An electric field was generated across the nozzle and the grounded mandrel, inducing a jet of solution to be drawn out from the syringe and resulted in the deposition of a solid-fiber core onto the rotating mandrel (Taylor, 1964). The rate of rotation of the mandrel, as determined by a calibrated digital stroboscope (Shimpo Instruments DT-311A), generated aligned and random fibers with diameters of 2–3 µm (Fig. 2). Specifically, a faster rotation rate of 5000 rpm was used to spin matrices of aligned fibers (aligned matrices) whereas a slower rotation rate of ~10 rpm or less generated randomly oriented fibers (random matrices). Additionally, an even distribution of the fibers on the mandrel was achieved by allowing the mandrel assembly to translate (0.5 Hz).

Fig. 1. The electrospinning apparatus.

Key system components include a solution reservoir (syringe), nozzle (18-gauge, blunted, metallic needle), high-voltage DC power supply and grounded target (rotating mandrel).

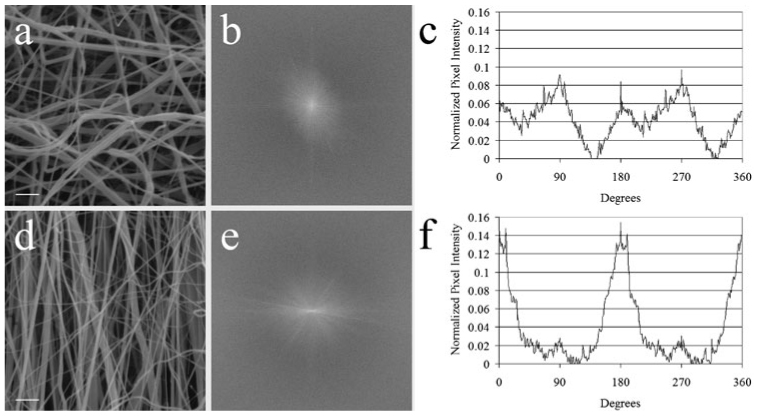

Fig. 2. Generation of aligned and randomly oriented PDS matrix fibers.

(a) SEM shows more randomly oriented fibers in a representative random matrix, generated by using a slower mandrel rotation speed (<10 rpm). (b) Raw output of the 2-D FFT alignment analysis of a random matrix. The more radially symmetrical silhouette of the 2-D FFT is consistent with fibers that are oriented in random directions. (c) Radial plot of the summations of relative pixel intensity at a radius versus the angle (°). The periodicity of the graph is caused by the inherent symmetry of the raw 2-D FFT output. The smaller, broader peaks reflect a more random distribution of directionality. (d) SEM showing more consistently oriented fibers in a representative aligned matrix that is generated using a mandrel rotation speed of 5000 rpm. (e) Raw output of the 2-D FFT alignment analysis of an aligned matrix. The slender profile of the silhouette indicaes fiber alignment. (f) A taller, narrower peak at ~180° indicates the general direction in which the fiber population is oriented. Scale bars in a and b, 10 µm.

Scanning electron microscopy

To prepare the matrices for scanning electron microscopy (SEM), 1-mm squares of both aligned and random matrices were cut from the electrospun mat and sputter-coated in gold. Photomicrographs (750 ×) were taken of random areas in each matrix, digitized with a flatbed scanner, and analyzed for fiber alignment using 2-dimensional fast Fourier transform (2-D FFT).

2-D FFT alignment analysis

As previously described by this laboratory (Alexander et al., 2006), utilizing the FFT function of the ImageJ image-processing software, an image containing a graphical representation of the frequency content was generated from a digitized, square, grayscale image of the elements to be analyzed. Pixel intensities and the distribution of the intensities (frequency content) of this output image correlate to the directional content of the original image. Pixel intensities were summed along a radius from the center to the edge of the image to quantify the relative contribution of objects oriented in that direction. This summing was repeated at 1° increments around the image and the 360 summations were plotted. In this manner, a 2-D FFT of an image containing randomly oriented elements results in relatively constant pixel intensities independent of direction. Theoretically, a radial summation of this type of data set should be represented as a flat line, however, because of edge effects associated with square images, an undulating plot with four small, symmetrical peaks results. In contrast, a 2-D FFT of an image that has elements that are aligned preferentially would result in higher pixel intensities along the aligned direction. Accordingly, when the radial summations are plotted, two peaks, representing the two angles (180° apart) associated with the aligned elements in an image are generally seen (Ayres et al., 2006; Ayres et al., in press).

DRG isolation and culture

In this study, the potential of aligned matrices to influence the growth dynamics of extending DRG neurites was tested. A set of random matrices was used as controls. DRGs were dissected from embryonic day 16 (E16) Sprague Dawley rats (Zivic Miller) as described previously (Sharma and Bigbee, 1998).

Circles of aligned and random matrices (8-mm diameter) were sterilized in 100% ethanol, rinsed in Hank’s balanced salt solution, and secured on the bottom of a 35-mm diameter Petri dish using hypodermic needles. Using a dissection microscope, several DRGs were micropipetted onto each matrix and pinned in place with 0.15-mm diameter minuten pins (Austerlitz). Cultures were incubated at 37°C with a 95% air/5% CO2 gas mix in Eagle’s minimum essential medium with glutamine supplemented with 10% glucose, 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.01% nerve growth factor (2.5). The medium was changed every two days, alternating between the above medium and medium containing the antimitotic agent, 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (10−5 M; Sigma-Aldrich), which limits the proliferation of Schwann cells in DRG cultures (Wood, 1976). Following a 10-day incubation, the cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Following fixation, DRG cultures were immunostained for the β-tubulin neuronal marker TuJ1 (Covance). Cultures were first blocked for 30 minutes in a solution consisting of PBS with 10% FBS and 0.3% Triton X-100, incubated for 2 hours in a 1:500 dilution of TuJ1 mouse primary antibody in PBS and visualized with a 1:200 dilution of Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) in PBS. 6 × digital, wide-field, fluorescence images of the DRG and its neuritic outgrowth were obtained using an Olympus BX51 microscope. For this study, DRGs were pinned on at least six matrices (three aligned and three random) and the experiment was repeated at least three times.

Astrocyte isolation and culture

In this study, the potential of aligned matrices to influence growth dynamics of astrocytes was tested. A set of random matrices was used as control. Rat primary astrocytes were isolated using methods described previously (McCarthy and de Vellis, 1980). Briefly, isolated postnatal day 3 (P3) rat cortices were minced and dissociated mechanically and enzymatically. Cells were seeded into T-75 poly-L-lysine-coated tissue culture flasks that contained Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/Ham’s F-12 medium, 10% FBS, and 1% 1X antibiotic-antimycotic agent, and allowed to proliferate until the population reached confluency (~12 days). During this time, media changes were made every 3–4 days. When confluent, cultures were shaken overnight in an incubator to remove non-adherent cells. Two cycles of treatment with the selective DNA-synthesis inhibitor cytosine arabinoside (Sigma-Aldrich) were carried out subsequently to further purify the astrocytic population.

Circles of aligned and random matrices were placed into 10-mm diameter culture wells and seeded with enzymatically-dissociated astrocytes at a concentration of 104 cells ml−1. Cultures were incubated for 7 days in the astrocyte media described above and fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Following fixation, astrocyte cultures were immunostained for the astrocytic marker, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (DAKO). Cultures were incubated for 2 hours in a 1:1000 dilution of the GFAP rabbit primary antibody in PBS and visualized with a 1:200 dilution of Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) in PBS. Images of astrocytes grown on aligned and random matrices were obtained with a Leica TCS-SP2 AOBS confocal microscope. For this study, astrocytes were seeded on at least six matrices (three aligned and three random) and the experiment repeated at least three times.

Astrocyte–DRG coculture

To test the extent to which astrocytes affect the growth of DRG neurites on electrospun PDS matrices, DRGs were cocultured with astrocytes that were first seeded on matrices as outlined above. Specifically, astrocytes were grown on either aligned or random matrices for 10 days until confluent. DRGs were then pipetted onto these astrocyte-seeded matrices, pinned down and cultured for an additional 10 days.

Immunohistochemistry was performed using a primary antibody cocktail of GFAP and TuJ1, and confocal images obtained for analysis. To determine the length of DRG neurite outgrowth on aligned matrices with and without astrocytes, a distance measurement was made from the center of the DRG to the furthest extent of overall neuritic outgrowth. Student’s t-test was used to determine statistical significance. For this study, astrocytes and DRGs were seeded and pinned respectively on at least six matrices (three aligned and three random) and the experiment repeated at least three times.

RESULTS

Using the apparatus shown in Fig. 1, PDS was electrospun onto a mandrel with a rotation speed of either 5000 rpm or <10 rpm to fabricate matrices containing fibers with varying degrees of alignment. SEM was then used to visualize the extent to which a mandrel speed of 5000 rpm generated aligned fibers (aligned matrix) and a mandrel speed of <10 rpm generated randomly orientated fibers (random matrix). Although the difference in fiber alignment between the two types of matrices was evident at the SEM level (Fig. 2a,d), a more objective determination of alignment was desirable to establish whether fiber alignment was significantly different. To achieve this, we employed a 2-D FFT methodology. Such an approach quantitatively analyzes the extent to which the population of fibers in the matrix is aligned with respect to each other, thereby establishing a general direction of alignment of the entire fiber population. After executing the algorithm on a converted grayscale SEM image cropped down to a square (Fig. 2a,d), the immediate output of a 2-D FFT is a frequency spectrum (Fig. 2b,e). The distribution of the pixels in the frequency spectrum can be used to evaluate fiber alignment in an original data image. A data image containing random elements produces a frequency spectrum with pixels distributed about the center in a symmetrical distribution (Fig. 2b). Conversely, a data image containing aligned elements produces a frequency spectrum with pixels distributed in an elongated ellipse (Fig. 2e). Fig. 2c,f are graphs of a 2-D FFT analysis on representative images of a random and aligned matrix, respectively. The height and width of the peaks indicate the uniformity of fiber alignment. The axis of distribution of the pixels in the frequency spectrum reports the principal axis of orientation (Ayres et al., 2006; Ayres et al., in press). Fibers electrospun at a high mandrel speed were displayed graphically as having a dominant orientation toward a specific direction (~180°, or a vertical orientation, in this case), thereby indicating a significant degree of alignment for the general fiber population. In contrast, for a random matrix, the presence of four small symmetrical peaks (associated with edge artifact) indicates that there is no preferential alignment. Moreover, the degree of fiber alignment in both types of matrices is consistent between electrospun samples fabricated for this study and those used in subsequent experiments.

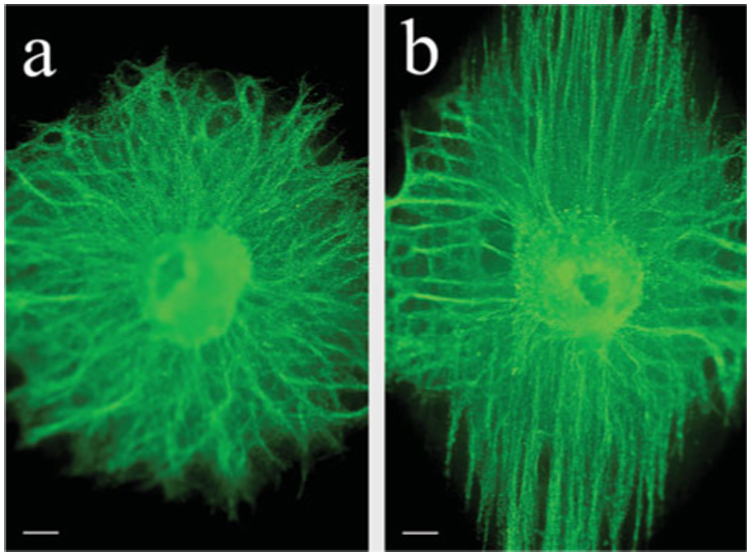

After confirming the matrix alignment, DRGs were pinned to matrices, cultured for 10 days, fixed and immunolabeled for the TuJ1 neuronal marker. Representative, low-power, fluorescent images of the DRGs on aligned and random matrices showed different patterns of neuritic outgrowth (Fig. 3). On a random matrix, neurites grew radially outward from the ganglion without preference to any specific direction, generating a round, spokes-of-a-wheel appearance (Fig. 3a). In contrast, on an aligned matrix most neurites grew preferentially along a particular axis (Fig. 3b). Using reflectance confocal microscopy, it was confirmed that this axis of growth was in the same orientation as the underlying fibers of the matrix (data not shown). Although a few neurites were not oriented initially to the direction of the underlying matrix, most eventually turned and continued their extension in the direction of the underlying fibers. Additionally, neurites growing in the direction of the underlying matrix grew faster than those growing perpendicular to the aligned fiber axis or on random matrix.

Fig. 3. Fiber alignment of the electrospun matrix is conferred to pinned DRGs.

Low-power, wide-field, fluorescent image of a representative DRG immunostained for TuJ1 (green) on matrix fixed 10 days after pinning. (a) DRG on a random matrix fixed 10 days after pinning. DRG neurites grown on a random matrix display a tortuous growth pattern that reflects the underlying matrix. (b) In contrast to DRG grown on a random matrix, neuritis grow preferentially in one direction (vertical in this image) that reflects the orientation of the underlying matrix fibers. Scale bars, 200 µm.

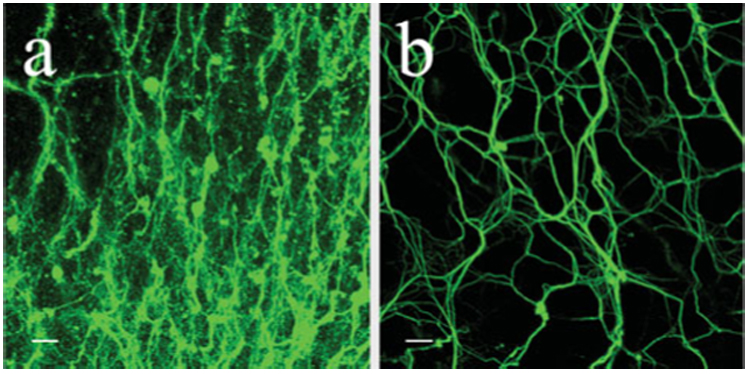

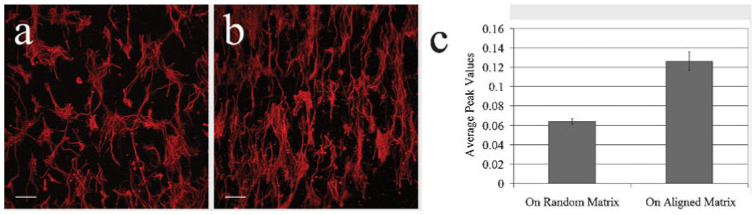

An observation that is not apparent in these images but evident in cultures grown for extended periods is that neurites began to show signs of cellular deterioration, such as the presence of membrane blebbing and vesiculation (Fig. 6a). These changes are common in neurons grown in vitro for extended periods in the absence of supportive or ECM substrata. Considering this, and that the matrices are generated from a resorbable material (PDS) that dissolves with time, we hypothesized that a glial substrate might provide a more stable, supportive interface between the resorbable matrix and the outgrowing neurites. Accordingly, astrocytes purified from P3 rat cortices were seeded onto aligned and random matrices and grown for 7 days. Subsequently, the matrices were fixed and immunolabeled for the astrocytic marker GFAP. Confocal images of astrocytes grown on both types of matrices show that these cells grow readily on electrospun PDS (Fig. 4). However, astrocytes grown on a random matrix extend processes that are positioned more randomly (Fig. 4a,c). This is in striking contrast to astrocytes grown on an aligned matrix (Fig. 4b,c), for which process extension mirrors the orientation of the underlying fibers.

Fig. 6. DRGs on astrocyte-seeded matrices grow more robustly, as evidenced by lack of vesiculation and fasciculation.

DRGs grown for 10 days on (a) a PDS matrix alone in the absence of astrocytes and (b) on an astrocyte-seeded PDS matrix. Astrocytes cannot be visualized because of the filter selection for this fluorescent image. Scale bars, 10 µm.

Fig. 4. Fiber alignment of the matrix is conferred onto seeded astrocytes.

Confocal images of astrocytes, immunostained with GFAP (red), grown on a random (a) or aligned matrix (b) for 7 days after seeding. In both instances, the orientation of the underlying matrix fibers is conferred to the astrocytic processes. (c) The average peak value of the 2-D FFT analysis (radial plot) on astrocytes seeded on matrices. Astrocytic process alignment on random and aligned matrices is statistically different (P = 0.004). Scale bars in a and b, 100 µm.

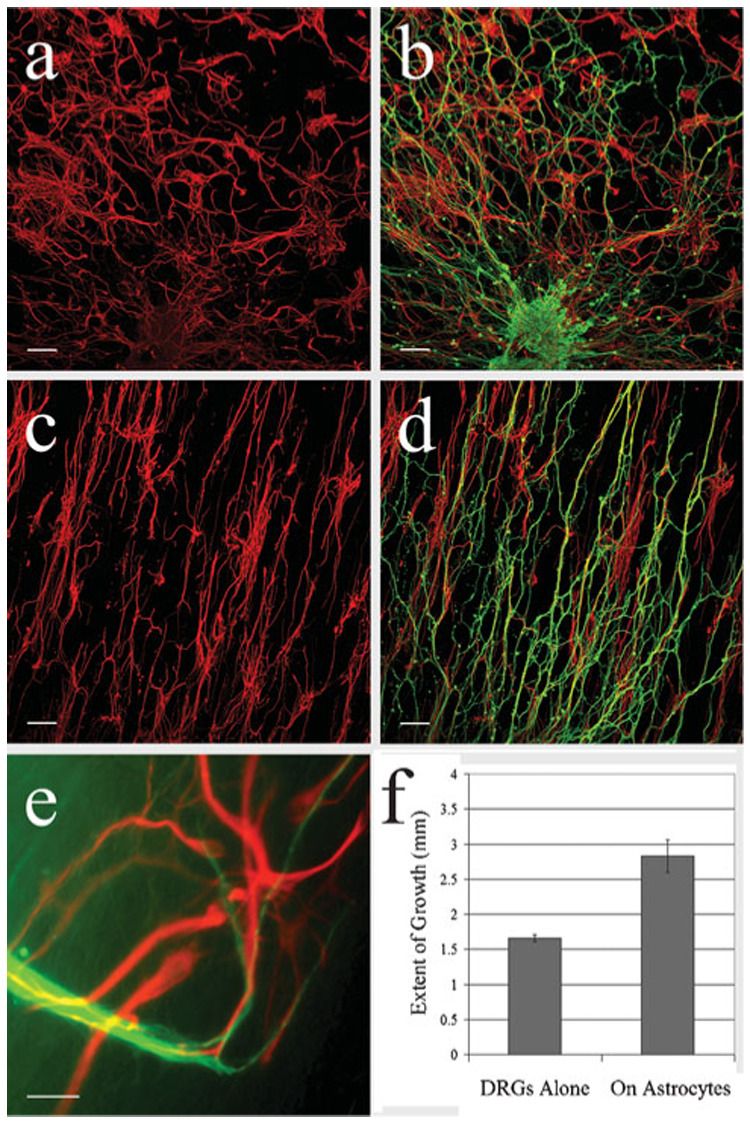

To test the extent to which astrocytes might improve the growth of DRG neurites on electrospun PDS matrices, DRGs were grown on matrices pre-seeded with astrocytes. First, dissociated astrocytes were seeded on aligned and random matrices and incubated for 10 days before DRGs were pinned onto the astrocyte-seeded matrices and incubated for 10 days. Subsequently, the matrices were fixed and dual-immunolabeled for TuJ1 and GFAP. Following 20 days growth, astrocytes seeded on both matrices extended longer processes than after only 7 days growth (Fig. 5a,c). Moreover, astrocytic processes were aligned to match the orientation of the underlying PDS fibers within each matrix, which is consistent with a shorter culture period. DRGs grown on a substrate of randomly-oriented astrocytes grew radially outward from the ganglion without preference to any specific direction (Fig. 5a,b). Conversely, DRGs grown on a substrate of aligned astrocytes (Fig. 5c,d) displayed a similar alignment and extended longer processes than when grown on a glia-free matrix (Fig. 5f). Many of the neurites on the aligned, astrocyte-seeded matrices reached the border of the matrix and continued growing on its opposite side. In both cases (aligned and random), processes changed direction readily to grow along astrocytic processes (Fig. 5e). Moreover, DRGs grown on either seeded matrix displayed less fasciculated outgrowth than observed on PDS matrices alone and appeared to be more robust, as evidenced by the lack of vesiculations and membrane blebbing (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. Aligned astrocytes influence the directionality and length of DRG neurite outgrowth.

(a–d) Confocal images showing DRG neurites (green) grown on astrocytes (red) seeded on either random (a,b) or aligned (c,d) matrices. In the presence of randomly oriented astrocytes (b), the orientation of the neurites is radial, growing out from the ganglion in all directions, whereas neurites grown on an aligned astrocyte-seeded matrix (d) display a similar alignment. (e) High-power, wide-field, fluorescent image showing that neurites change direction to grow along astrocytic processes. (f) The length of DRG neurite outgrowth on aligned matrices with or without seeded astrocytes. Outgrowth is significantly longer (P = 0.008) when grown on astrocyte-seeded matrices. Scale bars: a–d, 100 µm; e, 30 µm.

CONCLUSIONS

As confirmed by 2-D FFT analysis, matrices with aligned and randomly oriented PDS fibers can be produced by electrospinning with a rotation speed of either 5000 rpm or <10 rpm, respectively.

DRG neurons grown on random electrospun PDS matrices show no directional preference, whereas neurites grown on aligned matrices display directionality that mimics that of the underlying fiber orientation.

Astrocytes grown on random matrices show no directional preference, whereas astrocytes grown on aligned matrices display directionality.

DRGs cultured on a substrate of astrocytes grow more robustly and extend longer processes than when grown on a glia-free matrix.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have examined the potential use of electrospinning to engineer a polarized matrix for axonal guidance. By varying the rate of rotation of the mandrel, matrices containing aligned fibers and randomly oriented fibers were fabricated from PDS. The degree of fiber alignment was determined visually by SEM and quantified by 2-D FFT analysis. Both neurons and astrocytes were grown separately and in combination on these matrices to assess biocompatibility and growth dynamics. Specifically, when E16 DRGs were placed on these matrices and allowed to grow for 10 days, the direction of the projecting neurites matched the orientation of the underlying PDS fiber population. Moreover, on aligned matrices, the length of neuritic outgrowth exceeded that seen on random matrices. After 10 days in culture, however, neurites began to exhibit evidence of necrosis. In view of this, we tested the extent to which cortical astrocytes are compatible with these matrices and whether their presence affects DRG growth. When seeded on these PDS matrices, astrocytes grew robustly and the orientation of process outgrowth matched that of the underlying matrix. When DRGs were grown on these glial substrates, they exhibited no evidence of necrosis and their neurites aligned with astrocytes and displayed longer process outgrowth than on aligned PDS matrix alone. Collectively, these experiments demonstrate the potential for electrospinning to generate an aligned matrix that influences both the directionality and dynamics of DRG neurite growth.

In addition to generating an aligned matrix to influence the directionality of neurite outgrowth, the process of electrospinning can be manipulated further to generate matrices with additional characteristics that mimic more closely the in vivo environment of the CNS. Specifically, ECM molecules such as collagen and elastin remain biologically active when electrospun into matrices (Boland et al., 2004). These experiments provide evidence that viable ECM molecules in the CNS can also be electrospun into matrices to influence neuritic outgrowth. In our study, however, we elected to use the synthetic molecule PDS as the solute for electrospinning because of its proven biocompatibility, which is indicated by its inability to elicit an immune response, and its structural stability in biological tissue. These characteristics prevent the matrix from being remodeled in a manner that compromises its fiber polarity within a short time-frame, which is relevant when considering the use of this matrix to bridge lesioned areas of the CNS. Specifically, the alignment of the fibers in the matrix will remain stable, allowing regenerating axons sufficient time to cross the lesion into healthy target tissue. Moreover, by seeding the PDS matrix with astrocytes, we have generated a cellular bridge that retains alignment stability while providing crucial trophic support. Although not tested here, further modifications to the electrospinning processs should influence fiber diameter, matrix porosity and protein content (Bowlin et al., 2002), all of which influence the dynamics of axon growth.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by NIH Grants 5T32NS007288-20 and 5R21NS048377-02. Confocal microscopy was performed at the VCU Department of Anatomy & Neurobiology Microscopy Facility, which is supported, in part, with funding from NIH-NINDS Center core grant 5P30NS047463. We thank Dr. Scott Henderson for his insights and guidance on the confocal microscope, and Dr. Joseph Feher for drawing a schematic of the electrospinning apparatus.

REFERENCES

- Akiyama Y, Radtke C, Kocsis JD. Remyelination of the rat spinal cord by transplantation of identified bone marrow stromal cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:6623–6630. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06623.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JK, Fuss B, Colello RJ. Electric field-induced astrocyte alignment directs neurite outgrowth. Neuron Glia Biology. 2006;2:93–103. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X0600010X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres CE, Bowlin GL, Henderson SC, Taylor L, Shultz J, Alexander J, et al. Modulation of anisotropy in electrospun tissue-engineering scaffolds: Analysis of fiber alignment by the fast Fourier transform. Biomaterials. 2006;27:5524–5534. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres CE, Jha S, Meredith H, Bowman JR, Bowlin GL, Henderson SC, et al. Measuring fiber alignment in electrospun scaffolds: a user’s guide to the 2-D FFT approach. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition. doi: 10.1163/156856208784089643. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balentine JD. Pathology of experimental spinal cord trauma. I. The necrotic lesion as a function of vascular injury. Laboratory Investigation. 1978;39:236–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso DM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC. Graded histological and locomotor outcomes after spinal cord contusion using the NYU weightdrop device versus transection. Experimental Neurology. 1996;139:244–256. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC, Komon J, Tovar CA, Van Meter M, Anderson DK, et al. Endogenous repair after spinal cord contusion injuries in the rat. Experimental Neurology. 1997;148:453–463. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland ED, Coleman BD, Barnes CP, Simpson DG, Wnek GE, Bowlin GL. Electrospinning polydioxanone for biomedical applications. Acta Biomaterialia. 2005;1:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland ED, Matthews JA, Pawlowski KJ, Simpson DG, Wnek GE, Bowlin GL. Electrospinning collagen and elastin: preliminary vascular tissue engineering. Frontiers in Bioscience: A Journal and Virtual Library. 2004;9:1422–1432. doi: 10.2741/1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlin GL, Pawlowski KJ, Stitzel JD, Boland ED, Simpson DG, Fenn JB, et al. Electrospinning of polymer scaffolds for tissue engineering. In: Lewandrowski K, Wise D, Trantolo D, Gresser J, Yaszemski M, Altobelli D, editors. Tissue engineering and biodegradable equivalents: scientific and clinical applications. Marcel Dekker; 2002. pp. 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Bresnahan JC, Beattie MS, Stokes BT, Conway KM. Three dimensional computer-assisted analysis of graded contusion lesions in the spinal cord of the rat. Journal of Neurotrauma. 1991;8:91–101. doi: 10.1089/neu.1991.8.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge RP, Puckett WR, Becerra JL, Marcillo A, Quencer RM. Observations on the pathology of human spinal cord injury. A review and classification of 22 new cases with details from a case of chronic cord compression with extensive focal demyelination. Advances in Neurology. 1993;59:75–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridrikh SV, Yu JH, Brenner MP, Rutledge GC. Controlling the fiber diameter during electrospinning. Physical Review Letters. 2003;90:144502. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.144502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guth L, Barrett CP, Donati EJ, Anderson FD, Smith MV, Lifson M. Essentiality of a specific cellular terrain for growth of axons into a spinal cord lesion. Experimental Neurology. 1985;88:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(85)90109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houle JD, Tom VJ, Mayes D, Wagoner G, Phillips N, Silver J. Combining an autologous peripheral nervous system “bridge” and matrix modification by chondroitinase allows robust, functional regeneration beyond a hemisection lesion of the adult rat spinal cord. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:7405–7415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1166-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Oyanagi K, Wakabayashi K, Ikuta F. Traumatic spinal cord injury: a neuropathological study on the longitudinal spreading of the lesions. Acta Neuropathologica. 1997;93:13–18. doi: 10.1007/s004010050577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakulas BA. Pathology of spinal injuries. Central Nervous System Trauma. 1984;1:117–129. doi: 10.1089/cns.1984.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Field PM, Raisman G. Repair of adult rat corticospinal tract by transplants of olfactory ensheathing cells. Science. 1997;277:2000–2002. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand R, Woerly S, Bertrand L, Valdes N. Evaluation of two cross-linked collagen gels implanted in the transected spinal cord. Brain Research Bulletin. 1993;30:415–422. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90273-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy KD, Devellis J. Preparation of separate astroglial and oligodendroglial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue. Journal of Cell Biology. 1980;85:890–902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.3.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JW, Liu XZ, Qu Y, Liu S, Mickey SK, Turetsky D, et al. Transplanted embryonic stem cells survive, differentiate and promote recovery in injured rat spinal cord. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:1410–1412. doi: 10.1038/70986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norenberg MD, Smith J, Marcillo A. The pathology of human spinal cord injury: defining the problems. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2004;21:429–440. doi: 10.1089/089771504323004575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reier PJ, Bregman BS, Wujek JR. Intraspinal transplantation of embryonic spinal cord tissue in neonatal and adult rats. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1986;247:275–296. doi: 10.1002/cne.902470302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma KV, Bigbee JW. Acetylcholinesterase antibody treatment results in neurite detachment and reduced outgrowth from cultured neurons: further evidence for a cell adhesive role for neuronal acetylcholinesterase. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1998;53:454–464. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980815)53:4<454::AID-JNR7>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzel JD, Pawlowski KJ, Wnek GE, Simpson DG, Bowlin GL. Arterial smooth muscle cell proliferation on a novel biomimicking, biodegradable vascular graft scaffold. Journal of Biomaterials Applications. 2001;15:1–12. doi: 10.1106/U2UU-M9QH-Y0BB-5GYL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, Mai S, Norton D, Haycock JW, Ryan AJ, MacNeil S. Self-organization of skin cells in three-dimensional electro-spun polystyrene scaffolds. Tissue Engineering. 2005;11:1023–1033. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telemeco TA, Ayres C, Bowlin GL, Wnek GE, Boland ED, Cohen N, et al. Regulation of cellular infiltration into tissue engineering scaffolds composed of submicron diameter fibrils produced by electrospinning. Acta Biomaterialia. 2005;1:377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai EC, Dalton PD, Shoichet MS, Tator CH. Synthetic hydrogel guidance channels facilitate regeneration of adult rat brainstem motor axons after complete spinal cord transection. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2004;21:789–804. doi: 10.1089/0897715041269687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Wild KR, Brunelli GA. Restoration of locomotion in paraplegics with aid of autologous bypass grafts for direct neurotisation of muscles by upper motor neurons – the future: surgery of the spinal cord? Acta Neurochirurgica Supplement. 2003;87:107–112. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6081-7_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen X, Tresco PA. Fabrication and characterization of permeable degradable poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) hollow fiber phase inversion membranes for use as nerve tract guidance channels. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3800–3809. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PM. Separation of functional Schwann cells and neurons from normal peripheral nerve tissue. Brain Research. 1976;115:361–375. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniewicz B, Filipowicz K, Swiderska SK, Deraka K. Pathophysiological mechanism of traumatic cavitation of the spinal cord. Paraplegia. 1983;21:312–317. doi: 10.1038/sc.1983.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XM, Guenard V, Kleitman N, Bunge MB. Axonal regeneration into Schwann cell-seeded guidance channels grafted into transected adult rat spinal cord. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1995;351:145–160. doi: 10.1002/cne.903510113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Murugan R, Wang S, Ramakrishna S. Electrospinning of nano/micro scale poly(L-lactic acid) aligned fibers and their potential in neural tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2603–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]