Abstract

Glucocorticoids are capable of exerting both genomic and non-genomic actions in target cells of multiple tissues, including the brain, which trigger an array of electrophysiological, metabolic, secretory and inflammatory regulatory responses. Here, we have attempted to show how glucocorticoids may generate a rapid anti-inflammatory response by promoting arachidonic acid-derived endocannabinoid biosynthesis. According to our hypothesized model, non-genomic action of glucocorticoids results in the global shift of membrane lipid metabolism, subverting metabolic pathways toward the synthesis of the anti-inflammatory endocannabinoids, anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol (2-AG), and away from arachidonic acid production. Post-transcriptional inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2) synthesis by glucocorticoids assists this mechanism by suppressing the synthesis of pro-inflammatory prostaglandins as well as endocannabinoid-derived prostanoids. In the central nervous system (CNS) this may represent a major neuroprotective system, which may cross-talk with leptin signaling in the hypothalamus allowing for the coordination between energy homeostasis and the inflammatory response.

Index words: hypothalamus, anti-inflammatory, glucocorticoid, endocannabinoid, arachidonic acid, leptin

1. Introduction

Glucocorticoids are synthesized and released from the adrenal cortex in response to stress activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and under circadian control. Glucocorticoids are capable of exerting both genomic and non-genomic actions in target cells of multiple tissues, including the brain, which trigger an array of electrophysiological, metabolic, secretory and inflammatory regulatory responses. Generally, genomic actions are mediated by intracellular glucocorticoid receptors and the regulation of transcription factors and/or direct transcriptional regulation via binding to glucocorticoid response elements on the DNA, although active transport may also trigger genomic glucocorticoid actions (Schmidt et al., 2000). While the most rapid genomic effect reported for glucocorticoids takes little more than 7 minutes, such as in the case of the glucocorticoid-induced transcription of the mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat in L tk2 aprt2 cells (Groner et al., 1983), genomic glucocorticoid actions usually require more than an hour before they are detectable (Joels and De Kloet, 1992). Non-genomic effects of glucocorticoids, on the other hand, occur more rapidly, often taking only seconds to minutes to be detected (Ffrench-Mullen, 1995; Hyde et al., 2004; Malcher-Lopes et al., 2006). The non-genomic actions of glucocorticoids may involve multiple mechanisms mediated by intracellular and/or membrane-associated receptors. Our recent findings in the hypothalamus suggest that glucocorticoids cause rapid synthesis of the arachidonic acid-based endocannabinoids arachidonoyl-ethanolamine (anandamide, AEA) and 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol (2-AG) in neuroendocrine cells of the hypothalamus via activation of a cAMP signaling pathway (Di et al., 2003; Malcher-Lopes et al., 2006). Glucocorticoids have well-known anti-inflammatory effects in non-neuronal tissues, and these are mediated in part by rapid steroid actions that inhibit the production of arachidonic acid and downstream pro-inflammatory prostaglandins. Here, we discuss non-genomic glucocorticoid actions mediated by activation of the type II corticosteroid receptor, or glucocorticoid receptor, and putative membrane-associated receptors that may contribute to rapid anti-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids by shifting intracellular signaling away from the arachidonic acid-based pro-inflammatory response toward the production of endocannabinoids. In the central nervous system CNS this may represent a major neuroprotective system, and its cross-talk with leptin in the hypothalamus may be critical for the coordination between energy homeostasis and the inflammatory response.

2. Glucocorticoid-Mediated Non-Genomic Regulation of the HPA Axis

2.1. Non-genomic actions of glucocorticoids on anterior pituitary corticotropin cells

Glucocorticoids inhibit adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) release from cells of the anterior pituitary gland by reducing corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH)-induced secretion of ACTH in the portal blood through a feedback regulation comprised of both rapid and delayed components (Dayanithi and Antoni, 1989; Jingami et al., 1985; Keller-Wood et al., 1988; Keller-Wood and Dallman, 1984). Rapid glucocorticoid suppression of CRH-induced ACTH secretion occurs within 30 min of systemic glucocorticoid administration and accounts for about 50% of the glucocorticoid negative feedback effects (Dallman and Jones, 1973). There are conflicting reports on the genomic vs. non-genomic mechanisms controlling the rapid inhibitory feedback at the pituitary (Dayanithi and Antoni, 1989; Hinz and Hirschelmann, 2000). Hence, rapid (i.e., after 30 min) glucocorticoid inhibition of CRH-stimulated ACTH release from pituitary cell columns was blocked by the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist RU38486 and by blocking gene transcription and protein synthesis (Dayanithi and Antoni, 1989). These findings suggest that the glucocorticoid inhibition of pituitary ACTH secretion under these conditions is mediated by activation of glucocorticoid receptors and glucocorticoid receptor regulation of gene transcription. On the other hand, a recent in vivo study showed suppression of CRH-induced ACTH secretion within 5-15 min of intravenous glucocorticoid injection (Hinz and Hirschelmann, 2000). This effect was not blocked by either pretreatment with the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist RU38486 or by blocking gene transcription, suggesting an alternative non-genomic mechanism of glucocorticoid inhibition of ACTH release from the pituitary. The discrepancies between these studies may arise from the different preparations, isolated cells vs. whole animal, and/or from the different time frames under study, as the 30 min time point in the former study may already show delayed glucocorticoid effects, as suggested by the transcriptional dependence.

Rapid suppressive effects of glucocorticoids on CRH-induced ACTH release were also observed in a pituitary corticotropin-secreting cell line, AtT20 cells (Woods et al., 1992). Dexamethasone and the synthetic glucocorticoid receptor agonist, RU28362, inhibited CRH-stimulated ACTH release in a dose-dependent manner and this effect was blocked by an L-type Ca2+ channel antagonist. Dexamethasone also inhibited ACTH release evoked by Ca2+ channel activation by 56%. On the other hand, although CRH caused a significant increase in cAMP levels, dexamethasone had no detectable effect on CRH-induced cAMP accumulation. Therefore, it seems that dexamethasone prevents CRH-induced release of ACTH in these cells by blocking a Ca2+-dependent mechanism downstream from cAMP activation. The time frame used in this study was long enough (45-120 min) to include both non-genomic and genomic effects. In fact, the glucocorticoid inhibitory effect on CRH-induced ACTH release was suppressed by blocking gene transcription. It is less likely, on the other hand, that the dexamethasone-induced suppression of ACTH release in response to Ca2+ channel activation depends on genomic transcription and de novo protein synthesis.

Interleukin-1β facilitates CRH-induced ACTH release from perfused anterior pituitary cells by a mechanism that is not dependent on CRH receptor activation (Cambronero et al., 1992; Payne et al., 1994). This stimulatory effect of IL-1β on ACTH release was also subject to inhibition by a short glucocorticoid pretreatment (Cambronero et al., 1992).

2.2. Non-genomic action of glucocorticoids in the hypothalamus

The long loop negative feedback effect that glucocorticoids exert on CRH and vasopressin peptide synthesis in hypothalamic neurosecretory cells involves relatively well characterized steroid receptor-mediated mechanisms of gene transcription regulation (Fremeau et al., 1986; Funder, 1992; 1997; McEwen et al., 1986). On the other hand, the inhibition of peptide secretion from these neurons by glucocorticoids does not require transcriptional regulation and occurs on a time scale inconsistent with the involvement of de novo protein synthesis (Brush et al., 1974; Keller-Wood and Dallman, 1984). The cellular mechanisms underling this rapid glucocorticoid inhibitory feedback are less clear, but non-genomic regulation of neuronal activity is implicated to directly or indirectly suppress the action-potential dependent release of CRH and VP from parvocellular neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and reduce ACTH release from the anterior pituitary. Using an electrophysiological approach, Kasai and Yamashita (1988) demonstrated that cortisol could inhibit some neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus from adrenalectomized rats, but was ineffective in slices from intact rats (Kasai and Yamashita, 1988). Other studies in vivo verified that the firing rate of medial parvocellular hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus neurons projecting to the median eminence was directly suppressed by glucocorticoids and that the norepinephrine-mediated activation of most medial parvocellular neurons of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus was inhibited by glucocorticoids (Kasai et al., 1988; Saphier and Feldman, 1988).

We recently found using whole-cell patch-clamp recordings in acute hypothalamic slices that glucocorticoids rapidly (within 1 min) and dose-dependently reduced the frequency of spike-independent (miniature) excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) in both parvocellular and magnocellular neuroendocrine cells, indicating a suppression of glutamate release from synaptic terminals controlling paraventricular nucleus neuroendocrine cell excitation (Di et al., 2003; Di et al., 2005). The threshold concentration for the glucocorticoid-mediated synaptic effect was between 10 and 100 nM and the EC50 was between 300 nM and 500 nM, representing effective glucocorticoid levels characteristic of stress activation of the HPA axis. Single-cell RT-PCR analysis identified the glucocorticoid-responsive neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus as not only CRH-expressing cells, but also thyrotropin-releasing hormone-, vasopressin- and oxytocin-expressing parvocellular neurons as well as both vasopressin- and oxytocin-expressing magnocellular neurons. The glucocorticoid effect was not elicited by intracellular application of the steroid, was insensitive to glucocorticoid receptor and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, and was maintained when the glucocorticoid was conjugated to the membrane-impermeant bovine serum albumin, suggesting that it was mediated by a membrane receptor.

This glucocorticoid-induced suppression of synaptic excitation was prevented by postsynaptic blockade of G protein signaling, indicating that the presynaptic effect was triggered by a postsynaptic mechanism that depends on the activation of a G protein-mediated signaling pathway leading downstream to the release of a retrograde messenger, which, in turn, acts presynaptically to inhibit glutamate release. This effect was completely blocked by cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists and was mimicked and occluded by exogenous cannabinoid application (Di et al., 2003; Di et al., 2005; Malcher-Lopes et al., 2006). Mass spectrometry analyses further demonstrated the synthesis of the endogenous cannabinoids AEA and 2-AG in the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus in response to glucocorticoids (Di et al., 2005; Malcher-Lopes et al., 2006). Together, these findings indicated that glucocorticoids induced the synthesis and retrograde release of endocannabinoids, which suppressed the synaptic excitation of supraoptic and paraventricular neuroendocrine cells. Furthermore, this glucocorticoid-induced, endocannabinoid-mediated suppression of synaptic excitation was completely blocked by the adipocyte hormone leptin (Malcher-Lopes et al., 2006). The leptin effect was mediated by inhibiting cAMP activity via phosphodiesterase 3B activation, suggesting that the rapid glucocorticoid effect was mediated by a cAMP-dependent signaling pathway. That the rapid glucocorticoid suppression of synaptic excitation and endocannabinoid synthesis in paraventricular neurons was mediated by activation of a Gs-cAMP-protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway was confirmed using specific inhibitors of cAMP-dependent signaling (Malcher-Lopes et al., 2006). Thus, our findings demonstrated that glucocorticoids rapidly suppress synaptic excitation in hypothalamic neuroendocrine cells by triggering the synthesis and release of the endogenous cannabinoids AEA and 2-AG via a PKA-dependent signaling mechanism.

Glucocorticoids have been shown to activate membrane-initiated, non-genomic cellular mechanisms involving PKA activity in other cell types as well. For instance, dexamethasone caused a rapid decrease in intracellular [Ca2+] in a human bronchial epithelial cell line via actions that did not depend on either activation of glucocorticoid receptors or on transcriptional regulation (Urbach et al., 2002). The mineralocorticoid receptor agonist aldosterone also caused a similar elevation in [Ca2+] in these cells by acting on the same underlying mechanism (Urbach and Harvey, 2001). These effects were suppressed by inhibitors of adenylyl cyclase and PKA activity, and by blocking Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. They also demonstrated a rapid, non-genomic glucocorticoid modulation of bronchial epithelial cell pH by stimulation of the Na+/H+ exchanger, which was also mediated by a PKA-dependent pathway as well as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1 and ERK2) activation (Urbach et al., 2006; Verriere et al., 2005). A glucocorticoid-activated, non-genomic pathway was also shown to block ATP-evoked and P2X receptor-stimulated Ca2+ influx in mouse HT4 neuroblastoma cells via a PKA-dependent mechanism (Han et al., 2005). It has also been demonstrated that cAMP and PKA are required for and enhance glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in leukemic cells from patients with B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (Tiwari et al., 2005). These findings together support the existence of a glucocorticoid non-genomic mechanism that is triggered by a membrane Gs-coupled receptor and the activation of a cAMP-PKA signaling pathway in different kinds of cells.

The PKA-dependent non-genomic glucocorticoid effects in the hypothalamus are reminiscent of non-genomic actions of other steroids. For instance, 17β-estradiol was shown to rapidly increase cAMP generation and to stimulate cAMP/PKA-dependent Ca2+ uptake by a membrane-associated action in cultured rabbit kidney proximal tubule cells (Han et al., 2000) and in enterocytes isolated from rat duodenum (Picotto et al., 1996). Estrogen has also been reported to act through a non-genomic mechanism to increase cAMP levels in human breast cancer cells and uterus in vivo (Amarneh and Simpson, 1996). Further, progesterone has been shown to increase cAMP levels via activation of a putative membrane receptor and a non-genomic mechanism in human spermatozoa (Luconi et al., 2004).

Several studies have demonstrated a facilitation of endocannabinoid synthesis by PKA activity. Cadas et al. (1996) showed that agents that stimulate cAMP formation cause PKA-mediated potentiation of the Ca2+-dependent biosynthesis of the AEA precursor N-arachidonoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine (N-ArPE) (see below for discussion of endocannabinoid synthetic pathways). N-ArPE is thought to be synthesized by the Ca2+-dependent transacylation between phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine (Fig. 1), a reaction that also generates sn-1-lyso-2-arachidonoyl-phosphatidylcholine, which has been proposed to serve as a 2-AG precursor in neurons (Di Marzo and Deutsch, 1998). These observations are consistent with our findings in hypothalamic neuroendocrine cells showing that glucocorticoids stimulate a putative Gs-coupled membrane receptor and cAMP synthesis, leading downstream to PKA-dependent stimulation of a biosynthetic pathway common to both AEA and 2-AG. Activation of other enzymes, such as phosphatidylinositol–specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC), are required to carry on the synthesis of endocannabinoids from their precursors, and fast, non-genomic activation of PI-PLC by glucocorticoids has been demonstrated by different groups. For instance, in lymphoblastoid cells, 15 seconds of dexamethasone application were sufficient to activate the membrane PI-PLC (Graber and Losa, 1995). It was also demonstrated that dexamethasone-induced apoptosis of thymocytes involves non-genomic activation of PI–PLC (Cifone et al., 1999; Lepine et al., 2004; Marchetti et al., 2003).

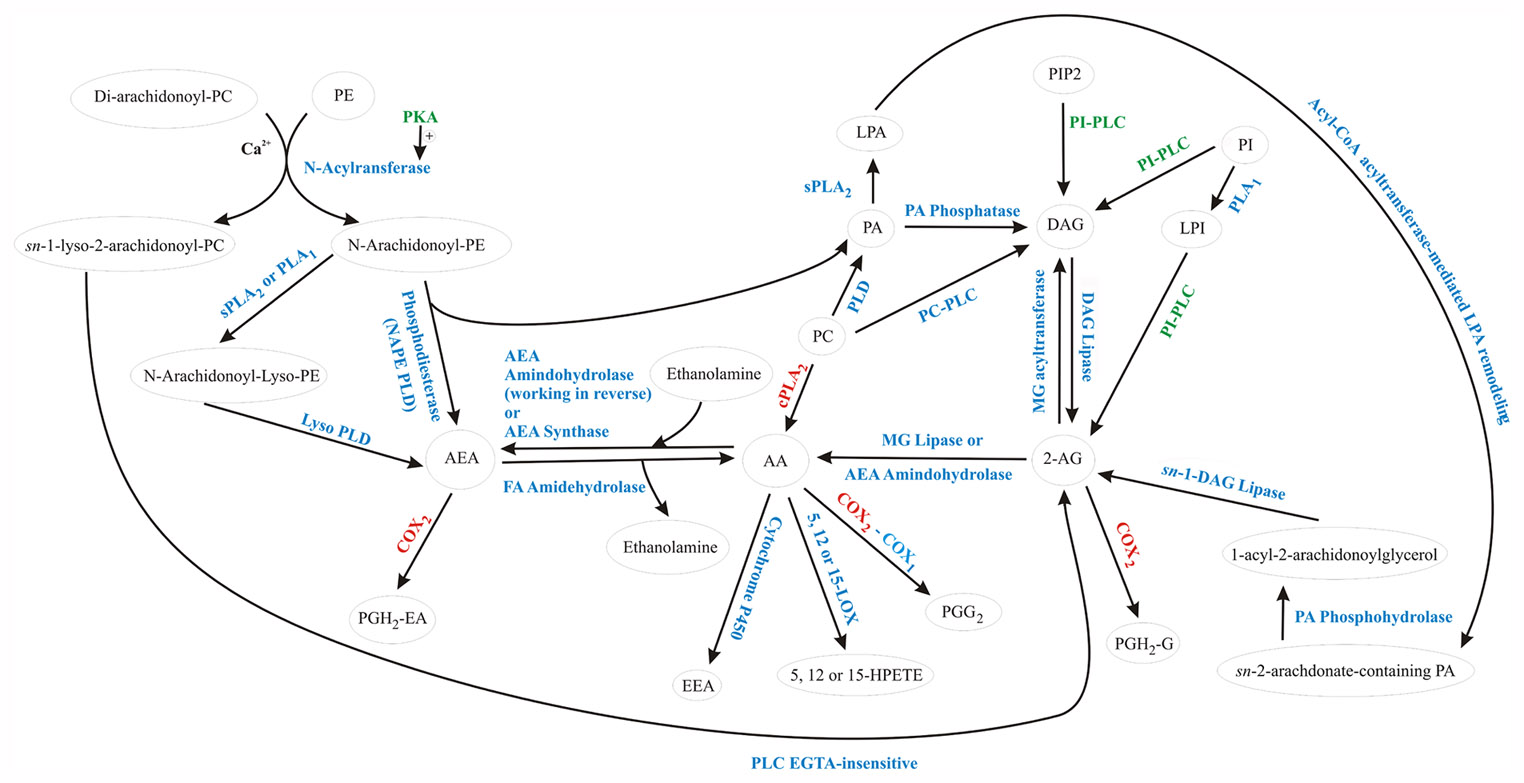

Figure 1.

Non-genomic and post-transcriptional glucocorticoid-mediated regulation of arachidonic acid and endocannabinoid metabolism. Enzymes stimulated or inhibited by glucocorticoids are shown in green and red, respectively. Glucocorticoids stimulate several enzymes that participate in the synthesis of different endocannabinoid precursors with concomitant inhibition of COX2, preventing endocannabinoid metabolism into endocannabinoid-derived prostaglandins. On the other hand, by inhibiting both cPLA2 and COX2, glucocorticoids prevent the use of endocannabinoid precursors to form arachidonic acid, making them available for the synthesis of endocannabinoids. The overall effect, therefore, is to shift the arachidonic acid metabolism away from the synthesis of prostaglandins, promoting endocannabinoid formation. AA, arachidonic acid; AEA, arachidonoylethanolamide (anandamide); COX2, cyclooxygenase 2; COX1, cyclooxygenase 1; DAG, diacylglycerol; EEA, epoxyeicosatrienoic acid; HPETE, hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acids; LPA, lisophosphatidic; PA, phosphatidic acid; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PGH2-EA, prostaglandin H2 ethanolamide; PGH2, prostaglandin hydroxy-endoperoxide; PGH2G, prostaglandin H2 glycerol ester; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PIP, phosphatidylinositol phosphate; PKA, protein kinase A; PLA1, phospholipase A1; PLC, phospholipase C; PLD, phospholipase D; sPLA2, secretory phospholipase A2.

3. Endocannabinoid Signaling

3.1. Biosynthesis of the arachidonic acid-containing endocannabinoids

The endocannabinoids AEA and 2-AG derive from the non-oxidative metabolism of arachidonic acid (Fig. 1) and belong to two well known lipid classes, the acyl-ethanolamines and the monoglycerides (Schmid et al., 1990). The biosynthetic pathways leading to the formation of arachidonic acid cross talk with numerous pathways involved in the synthesis and metabolism of many membrane-derived fatty acid derivatives, including the endogenous cannabinoids AEA and 2-AG. N-acylethanolamines are a group of ethanolamines with long-chain fatty acids that are involved in anti-inflammatory and membrane-stabilizing actions and apoptotic processes (Epps et al., 1980; Epps et al., 1979; Hansen et al., 1995; Kondo et al., 1998; Schmid et al., 1995) in different mammalian cells and tissues (Hansen et al., 2000; Schmid, 2000; Schmid and Berdyshev, 2002; Schmid et al., 1990; Sugiura et al., 2002). The arachidonic acid-containing N-acylethanolamine, N-arachidonoyl-ethanolamine (AEA), was the first identified endogenous ligand of the cannabinoid (CB) receptors (Devane et al., 1992) and vanilloid receptor (Di Marzo et al., 2002), and was shown to exert behavioral and physiological effects similar to those of the cannabis-derived Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) (Di Marzo, 1998; Mechoulam et al., 1998). In contrast, N-acylethanolamines with a saturated or monounsaturated fatty acid, such as N-palmitoyl-ethanolamine, do not activate cannabinoid receptors but share with endocannabinoids their anti-inflammatory and anti-nociceptive properties (Calignano et al., 1998; Calignano et al., 2001; Lambert et al., 2002). A second endocannabinoid with agonist activity at cannabinoid receptors, 2-AG, was subsequently discovered and has also been found in several different cell types, including neurons, blood cells, and inflammatory cells (Mechoulam et al., 1995; Sugiura et al., 1995).

The first biochemical reaction shown to produce AEA was identified in mammalian brain fractions and consisted of the direct condensation of arachidonic acid and ethanolamine (Fig. 1). This reaction was catalyzed by a putative membrane-bound “AEA synthase,” which required both precursors to be present at relatively high (i.e., mM) concentrations (Devane and Axelrod, 1994; Kruszka and Gross, 1994). This AEA synthase activity was found to be highly concentrated in brain homogenates where synaptic constituents were present (Devane and Axelrod, 1994), and despite the high substrate concentration requirements, it seems to be very selective, using only arachidonic acid as the aliphatic constituent and ethanolamine as the polar moiety (Kruszka and Gross, 1994). It was suggested that under physiological conditions, an increased production of arachidonic acid and ethanolamine by phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and phospholipase D (PLD) would be necessary to provide an appropriate amount of substrate for AEA synthesis. Later, however, a protein also identified in porcine brain with the same chemical properties as the previously described AEA synthase also catalyzed the reverse reaction, that is the hydrolysis of AEA to produce arachidonic acid and ethanolamine. This raised the question whether the AEA synthase was in fact an “AEA amidohydrolase” isozyme working in reverse when high substrate concentrations were present (Ueda et al., 1997; Ueda et al., 1995). Regardless, two distinct enzymatic activities for the synthesis and degradation of AEA, respectively, from and to arachidonic acid and ethanolamine were identified in the mouse uterus (Paria et al., 1996), supporting the idea that AEA could be directly formed from arachidonic acid and ethanolamine under physiological conditions.

Alternative mechanisms for AEA biosynthesis have also been described. Using cultured neurons, Di Marzo and collaborators demonstrated a distinct pathway for AEA synthesis that was Ca2+-dependent and activated by membrane depolarization (Fig. 1). This Ca2+-dependent AEA synthesis occurred through phosphodiesterase-mediated cleavage of a novel phospholipid precursor, N-ArPE (Di Marzo et al., 1994). Conversion of N-ArPE to AEA was PLA2-independent, but required a phospholipase D-like enzyme and trans-acylase activity (Felder et al., 1996; Okamoto et al., 2004). The trans-acylase activity was shown to be dependent on intracellular Ca2+ and stimulated by PKA (Cadas et al., 1996), which reduces the threshold of the intracellular [Ca2+] necessary for N-ArPE formation. In fact, it has been proposed that, in the absence of concomitant activation of PKA, the Ca2+ levels alone necessary to activate N-ArPE biosynthesis would probably never be achieved under physiological conditions (Di Marzo, 1999). Consequently, PKA activity is most likely necessary for in vivo endocannabinoid biosynthesis by this pathway.

Alternatively, N-ArPE can also be converted to N-arachidonoyl-Lyso-PE by phospholipase A1 (PLA1) or PLA2, and then converted to AEA by a lysophospholipase D (Lyso PLD) (Natarajan et al., 1984; Sun et al., 2004). Sun and collaborators demonstrated that several secretory PLA2 isoenzymes (sPLA2), but not a cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2α), can generate N-acyl-lysoPE from N-ArPE. However, they could not rule out the possibility that PLA1 can also catalyze this reaction. They further showed that this PLA2 / PLA1 activity for N-palmitoyl-PE was broadly distributed in different rat tissues including the brain, thymus, pancreas, and stomach, among others. Interestingly, both N-palmitoyl-ethanolamine and AEA were produced at the same rate in this pathway. Therefore, since sPLA2 isozymes, especially sPLA2-IIA, are up-regulated at inflamed tissues and are implicated in inflammatory processes, it is possible that the pathway utilizing N-acyl-lysoPE might be involved in the production of anti-inflammatory N-acylethanolamines at sites of inflammation (Sun et al., 2004).

There are several possible biosynthetic pathways for the monoglyceride endocannabinoid, 2-AG, including some pathways coupled to AEA (Fig. 1). For instance, if di-arachidonoyl-phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine are used as substrates for N-acyltransferase, then N-ArPE and sn-1-lyso-2-arachidonoyl-PC are formed. The latter have been proposed as direct precursors for the formation of 2-AG by a PLC isoenzyme (Di Marzo et al., 1996). Furthermore, phosphatidic acid (PA) formed by N-ArPE PLD is a precursor for diacylglycerol (DAG), the principal 2-AG precursor. Several pathways converge to generate DAG. Thus, DAG can be formed from PA by the PA phosphatase and by the hydrolytic reactions catalyzed by phospholipase C (PLC) activity on phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylinositol (PI) or phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PIP2). Diacylglycerol is then hydrolyzed to 2-AG by the action of DAG lipase (Di Marzo et al., 1996; Prescott and Majerus, 1983; Stella et al., 1997; Sugiura et al., 2002). These PLC-dependent pathways were initially described as degradation routes for arachidonic acid-DAGs in platelets (Prescott and Majerus, 1983) and were shown to mediate the Ca2+-induced generation of 2-AG in cultured neurons (Stella et al., 1997). Okuyama and coworkers have proposed that 2-AG can be produced by the hydrolysis of PI by a PI-specific phospholipase A1 (PI-PLA1) to produce lysophosphatidylinositol (LysoPI), which is then hydrolyzed to 2-AG by a specific PLC, the lysoPI-specific PLC (Tsutsumi et al., 1995; Tsutsumi et al., 1994; Ueda et al., 1993). Although the physiological significance of such a pathway is still undetermined, the lysoPI-specific PLC is found in synaptosomes.

Arachidonic acid-containing phosphatidylcholine can also supply substrate for 2-AG biosynthesis, since it can be converted to phosphatidic acid and DAG by the sequential actions of phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid phosphatase (Sugiura et al., 2004) (Fig. 1). Bisogno and coworkers demonstrated a PLC-independent pathway in N18TG2 cells, where DAGs serving as 2-AG precursors were produced through the hydrolysis of phosphatidic acid (Bisogno et al., 1999). The formation of 2-AG from its stereoisomer 1(3)-arachidonoylglycerol was also demonstrated in several nerve cells stimulated with agonists coupled to PI-PLC (Di Marzo and Deutsch, 1998). The stereoisomer precursor is formed by the sequential hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositols and DAGs catalyzed respectively by the G-protein-coupled PI-PLC and an sn-1-selective DAG lipase.

3.2. Endocannabinoids as retrograde messengers in the nervous system

Initially, the lipophilic character of endocannabinoids, which is unusual among neurotransmitters, posed difficulties for understanding their role in neuromodulation. Endocannabinoids are not stored in vesicles, but rather are synthesized from membrane phospholipid precursors and they can, therefore, be released on demand from virtually any region of the cell and are likely to reach their targets by crossing membranes in close proximity to one another (Di Marzo et al., 1999b) or, possibly, that are in actual contact with each other. Once released, endocannabinoids can act at both presynaptic and postsynaptic sites (Breivogel and Childers, 1998).

In the early 1990s, an “unconventional” form of interneuronal communication was discovered, which opened the way for the elucidation of endocannabinoid actions in the brain. It was shown that a brief depolarization of CA1 pyramidal hippocampal neurons caused a transient suppression of synaptic GABA inputs, referred to as depolarization-induced suppression of synaptic inhibition (DSI) (Pitler and Alger, 1992). The DSI was characterized by a decrease in GABAergic synaptic events in the absence of any change either in quantal size or in postsynaptic sensitivity to GABA, indicating a suppression of GABA release with DSI (Alger et al., 1996; Pitler and Alger, 1992). The suppression of GABA release by postsynaptic depolarization suggested a presynaptic modulation induced by an activity-dependent postsynaptic mechanism, and indicated that DSI was mediated by a retrograde messenger released from the postsynaptic cell and transmitted to presynaptic GABA terminals to suppress GABA release. In 2001, it was demonstrated that DSI in the hippocampus was mediated by the activity-dependent retrograde release of an endocannabinoid (Huang et al., 2001; Kreitzer and Regehr, 2001a; b; Maejima et al., 2001; Robbe et al., 2001; Wilson and Nicoll, 2001). Since then, evidence supporting the role of endocannabinoids as retrograde messengers in DSI as well as in response to activation of postsynaptic G protein-coupled receptors has been acquired in different cell types from several different areas of the brain (Freund et al., 2003). In addition, evidence for a similar activity-dependent endocannabinoid release and retrograde suppression of glutamatergic excitatory synaptic inputs (DSE) was subsequently described (Ohno-Shosaku et al., 2002) and has since been reported in several different areas of the brain, including in the hypothalamus (Hirasawa et al., 2004; Di et al., 2005).

3.3. The role of endocannabinoids in HPA modulation

Data on the effects of endogenous and exogenous cannabinoids on HPA axis secretion point to a primary impact on the hypothalamus, but there is also some evidence of possible direct cannabinoid CB1 receptor-mediated modulation of the HPA axis at the anterior pituitary. Accordingly, cannabinoid CB1 receptor-mRNA transcripts have been isolated from anterior pituitary and, to a lesser extent, from the intermediate lobe, whereas they were not found in the neural lobe (Gonzalez et al., 1999). Although AEA itself was detected only in trace amounts, higher concentrations of the AEA precursor N-ArPE and of 2-AG were found in the anterior pituitary, suggesting that endocannabinoids may be synthesized there. Furthermore, cannabinoid CB1 receptors were found and cannabinoid inhibition of hormone secretion was observed in human anterior pituitary cells, including corticotrophs, mammotrophs, somatotrophs, and folliculostellate cells. Also, the endocannabinoids AEA and 2-AG have been reported in human pituitary tissue (Pagotto et al., 2001).

The use of cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice to address the mechanisms and site of action for endocannabinoid-mediated modulation of the HPA axis has revealed a complex pathway. Peripheral treatment of cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice with AEA unexpectedly resulted in a significant elevation of plasma ACTH and corticosterone, and an increase in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus Fos immunoreactivity (Wenger et al., 2003). This effect was not blocked by antagonism of either cannabinoid CB1 receptor or the transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) receptor, and suggested the involvement of a non-CB1 type of cannabinoid receptor. A similar cannabinoid CB1 receptor-independent activation of the HPA axis and of c-fos expression in the paraventricular nucleus by exogenous AEA application was also observed in normal rats (Wenger et al., 1997). Considering the available data, a possible alternative explanation for this effect is the conversion of exogenous AEA by cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2) to prostaglandin ethanolamides, which have been shown to be produced in vivo in mice injected with AEA and to increase synaptic excitation in the hippocampus through acannabinoid CB1 receptor-independent mechanism (Weber et al., 2004).

A parallel study in the same cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mouse revealed an increased activation of the HPA axis in the knockout mice under basal and stress-stimulated conditions (Barna et al., 2004). The loss of the inhibitory effect of endogenous cannabinoids on ACTH and corticosterone secretion in this study was mediated by the loss of cannabinoid CB1 receptors located within the brain, and not at the level of the anterior pituitary, since the CRH stimulation of ACTH release, and its suppression by dexamethasone, were similar in pituitary explants from both the knockout and wild type mice. Furthermore, the cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 was without effect on ACTH release. These results indicate that the short-loop glucocorticoid negative feedback at the pituitary is cannabinoid CB1 receptor-independent, while the long-loop feedback in the hypothalamus is cannabinoid CB1 receptor-dependent, and that the heightened activity of the HPA axis in cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout animals may be a consequence of a disrupted glucocorticoid negative feedback at the level of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus.

A recent study using a different strain of cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mouse also reported an impaired glucocorticoid negative feedback in the knockout animals, although in this study there was a significant contribution to the impairment by the pituitary (Cota et al., 2007). A significant increase in plasma corticosterone concentration was measured at the onset of the night cycle in these mice, and dexamethasone suppression of ACTH and corticosterone secretion was only effective at the highest dose tested (100 mg/kg ip). Also, CRH mRNA was increased within the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and glucocorticoid receptor mRNA in the hippocampal CA1 region was reduced in the cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice, suggestive of impaired negative feedback. No difference in basal ACTH secretion was detected in pituitary primary cell cultures prepared from the cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout animals. The most striking difference in their study was the finding that CRH- or forskolin-stimulated ACTH release was greater in the pituitary cell cultures from the cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice. These last two findings differed from those of Barna and colleagues (2004), who reported no differences in basal and CRH-stimulated ACTH secretion from pituitaries isolated from knockout and wildtype mice. These contradictory findings might be explained by the use in the two studies of different background strains of mice or of different genders, or by the different methodologies employed by the two groups. The study by Barna et al. (2004) employed an explant perifusion approach that permitted continuous sampling of ACTH and repeated measures of ACTH responses to CRH applications, whereas the study by Cota et al. (2007) used primary cell cultures and measured single ACTH responses to 4 hr incubations in CRH or forskolin. Nevertheless, it is clear from these studies that deletion of cannabinoid CB1 receptor results in a heightened basal tone of the HPA axis and impairment of the negative feedback effects of glucocorticoids. What is not clear from these studies is to what extent cannabinoid CB1 receptor deletion affects the regulation of CRH release from the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus.

3.4. Cannabinoid receptor-mediated intracellular signaling

The cannabinoid CB1 receptor is coupled to Gαi and to the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase, which leads to a reduction in cAMP levels and reduced downstream PKA activity. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor activation causes the inhibition of N- and P/Q-type calcium channels, as well as stimulation of inward rectifying potassium channels (Ameri, 1999; Davis et al., 2003; Derkinderen et al., 2001; Derkinderen et al., 2003; Felder et al., 1995; Howlett, 1995; Wilson and Nicoll, 2001). There is also evidence for cannabinoid receptor-mediated activation of phospholipase A (PLA) and phospholipase C (PLC) and phosphorylation-dependent activation of MAPKs, ERK1, ERK2, p38 and Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), leading to the regulation of nuclear transcription factors (Howlett, 2005; Sugiura et al., 2004).

Several studies suggest that AEA and 2-AG may be internalized via a common carrier-mediated process with high substrate and inhibitor selectivity (Beltramo and Piomelli, 2000; Piomelli et al., 1999). Studies using an inhibitor of the transporter, N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-arachidonylamide (AM404), support a role of the AEA transporter in the inactivation of exogenously administered AEA (Beltramo and Piomelli, 2000; Beltramo et al., 1997). It has been proposed that the same transporter may also be involved in the release of AEA (Hillard and Jarrahian, 2000). The activity of the transporter is positively modulated by nitric oxide donors (Bisogno et al., 2001; Maccarrone et al., 2000). COX2 dependent termination of endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic effects in the hippocampus has also been reported (Sang et al., 2006). Termination of the endocannabinoid effect is, therefore, under the control of a specific mechanism of reuptake, which introduces an additional level of synaptic activity modulation.

3.5. Cannabinoid receptor distribution overlaps with that of glucocorticoid receptors

The central cannabinoid receptor, cannabinoid CB1 receptor is expressed predominantly in the brain, and is found at moderate to high levels in the hippocampus, cerebellum, striatum, neocortex and hypothalamus (Moldrich and Wenger, 2000; Tsou et al., 1998). They are present in the brain at higher levels than most of the other known G protein-coupled receptors (Breivogel and Childers, 1998). Immunohistochemical studies have revealed cannabinoid CB1 receptor expression in the lateral hypothalamus (Moldrich and Wenger, 2000) and the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of rats and mice (Castelli et al., 2007; Tsou et al., 1998; Wittmann et al., 2007). The CB2 receptor is found primarily in the spleen and in hematopoietic cells (Munro et al., 1993), although it was recently also found in the brainstem (Sharkey et al., 2007). It is noteworthy that there is substantial overlap between the distribution of cannabinoid receptors and glucocorticoid receptors in the CNS and other tissues. In the rat brain, glucocorticoid receptors are abundantly expressed in several areas where cannabinoid CB1 receptors are also expressed, including the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, hippocampus, cortex, cerebellum, and various brain stem nuclei (De Kloet et al., 1998; Fuxe et al., 1985a; Fuxe et al., 1985b).

4 Non-Genomic Pathways Activated by the Cytosolic Glucocorticoid Receptor

4.1. Glucocorticoid receptor-mediated immune suppression

Glucocorticoids have been used therapeutically for their immunosuppressant effects, which involve both genomic and non-genomic mechanisms (Inagaki et al., 1992; Lowenberg et al., 2006b). Through genomic actions, glucocorticoids inhibit the gene expression of pro-inflammatory factors, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-2, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferon γ (IFN-γ), prostaglandins, nitric oxide synthase, and adhesion molecules (Ashwell et al., 2000; Barnes and Adcock, 1993; Cohen and Duke, 1984). On the other hand, the same glucocorticoid receptor present in the cytosol of T lymphocytes has been shown to also suppress T-cell activation by mechanisms that do not depend on de novo protein synthesis. Several studies have demonstrated that the inactive form of the glucocorticoid receptor is present in the cytosol of T lymphocytes as part of a T-cell receptor (TCR)-linked multiprotein complex that contains chaperone proteins such as heat-shock protein (HSP) 90, lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase (LCK) and FYN oncogene (Bamberger et al., 1996; Lowenberg et al., 2006b; Pratt, 1998). Upon glucocorticoid binding to the glucocorticoid receptor, this complex dissociates, the glucocorticoid receptor dimerizes and exposes a nuclear localization signal, which allows it to translocate to the nucleus (Beato et al., 1996; Picard and Yamamoto, 1987). Once inside the nucleus, the active form of the glucocorticoid receptor regulates the transcription of genes involved in the immune response by binding to transcription factors, such as activator protein 1 (AP1) and nuclear factor kB (NFkB), and by direct actions at glucocorticoid response elements on the chromosomal DNA (Boumpas et al., 1991; Cato and Wade, 1996; Franchimont, 2004). The dissociation of the glucocorticoid receptor-TCR complex caused by glucocorticoid binding also disrupts the TCR-dependent LCK/FYN signaling pathway (Lowenberg et al., 2006b), which is essential for activating the T-cell response (Allison and Havran, 1991; Cooke and Perlmutter, 1989; Ehrlich et al., 2002; Li et al., 2004; Lustgarten et al., 1991; Palacios and Weiss, 2004; Rivas et al., 1988; Rudd et al., 1989). When the complex is intact, TCR stimulation causes the activation of p56LCK and p59FYN, leading to downstream activation of protein kinase C (PKC), protein kinase B (PKB), the MAPK p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and JNK, which results in T-cell activation (Denny et al., 1999; Denny et al., 2000; Janeway and Bottomly, 1994; Mustelin and Tasken, 2003; Nel, 2002; Nel and Slaughter, 2002; Salojin et al., 1999).

Lowenberg and coworkers showed that glucocorticoids rapidly impaired phosphorylation of LCK/FYN and suppressed signaling downstream from the LCK-CD4 and FYN-CD3 complexes, so that the activation of PKC, PKB, and the MAPKs were non-genomically attenuated by glucocorticoid disassembly of the TCR-linked complex (Lowenberg et al., 2005). However, the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist RU38486 could either mimic or suppress the effect of dexamethasone, depending on the concentration used. It is possible that this dual effect was caused by RU38486-induced disruption of the TCR-linked multiprotein complex, in which the glucocorticoid receptor, LCK and FYN are non-covalently associated. Indeed, the glucocorticoid receptor antagonists, RU38486 and RU40555, although unable to induce glucocorticoid receptor-mediated gene regulation (Fryer et al., 2000; Nordeen et al., 1995; Pariante et al., 2001), do induce significant glucocorticoid receptor nuclear translocation (Htun et al., 1996; Jewell et al., 1995; Qi et al., 1990; Rupprecht et al., 1993; Sackey et al., 1997) and DNA binding (Beck et al., 1993; Pariante et al., 2001; Schmidt, 1986), which should also lead to the disassembly of the TCR-linked complex. Therefore, RU38486 may mimic the rapid dexamethasone immunosuppressive effects by similarly disrupting the LCK/FYN signaling pathway.

4.2. Glucocorticoid receptor-mediated insulin resistance

An important side effect of glucocorticoid immunosuppressant therapy is the induction of insulin resistance. This has important clinical considerations given that insulin resistance is a risk factor not only for the development of Type II diabetes mellitus, but also for cardiovascular disease. The insulin receptor signaling pathway regulates growth and metabolic responses in many cell types (Czech and Corvera, 1999). Upon insulin binding, the insulin receptor activates a number of downstream signaling intermediates, including insulin receptor substrate (IRS), p70S6 kinase (p70S6K), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K), protein kinase B (PKB), and glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3 (Chan et al., 1999; Cheatham et al., 1994; Hill et al., 1999; Lowenberg et al., 2006a; Proud and Denton, 1997; Wang et al., 1999; White, 1997). Prolonged treatment with dexamethasone reduced IRS-1, PI3K, and PKB in adipocytes (Buren et al., 2002; Turnbow et al., 1994), indicating a genomic down-regulation by glucocorticoids. However, Lowenberg and coworkers showed that in cultured adipocytes and T lymphocytes, short-term dexamethasone treatment non-genomically abrogates insulin receptor-initiated signaling (Lowenberg et al., 2006a). Thus dexamethasone treatment caused a reduction in the kinase activities of insulin receptors and several downstream signaling intermediates: GSK-3, FYN, AMPK, and p70S6k. On the other hand, dexamethasone caused increased JNK phosphorylation, which is also able to reduce the response to insulin (Lowenberg et al., 2006a). In this case, dexamethasone inhibition of insulin signaling was clearly inhibited by the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist RU38486, and was insensitive to blockade of gene transcription, supporting a transcription-independent mechanism mediated by the intracellular glucocorticoid receptor.

4.3. Glucocorticoid receptor-mediated inhibition of arachidonic acid release

A major factor contributing to the anti-inflammatory action of glucocorticoids is the suppression of inflammatory prostaglandins. One way by which glucocorticoids suppress prostaglandin synthesis is by inhibiting the release of the prostaglandins precursor, arachidonic acid, catalyzed by phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (Bailey, 1991). Several studies indicate that glucocorticoids can suppress PLA2-mediated synthesis of arachidonic acid by a fast, non-genomic mechanism involving the cytosolic glucocorticoid receptor.

For instance, dexamethasone suppressed endotoxin-induced prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)-mediated diarrhea in mice by inhibiting arachidonic release, and the inhibitory action of dexamethasone was not blocked by inhibiting protein synthesis, indicating a non-genomic mechanism of the glucocorticoid (Doherty, 1981). Bradykinin stimulates a rise in intracellular calcium concentration leading to PGE2 production in cultured porcine tracheal smooth muscle cells, an effect that is suppressed by dexamethasone pretreatment for 24 h. Dexamethasone also suppressed bradykinin-stimulated release of radioactivity from cells that had been prelabeled with 3H-arachidonic acid. These findings suggest that dexamethasone suppressed PGE2 production by reducing the activity of cytosolic PLA2 and PGE2 synthase (Tanaka et al., 1995).

Dexamethasone suppressed IL-1β-induced arachidonic acid and PGE2 release in cultured A549 pulmonary adenocarcinoma cells, and this was mimicked by the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, RU486. On the other hand, RU486 blocked the dexamethasone inhibition of IL-1β-induced, COX2 gene expression in the same cells. Thus, both dexamethasone and RU486 suppress arachidonic acid biosynthesis and release, but the dexamethasone-induced genomic repression of COX2 and PGE synthase is antagonized by RU486. This is reminiscent of the non-genomic immunosuppressive effect in T-cells mediated by both RU486 and dexamethasone described above, and suggests that the glucocorticoid receptor multiprotein complex may be involved in the dexamethasone suppression of IL-1β-induced arachidonic acid release. Hence, glucocorticoid response element-dependent transcription was induced by dexamethasone but was unaffected by RU486, indicating that a non-genomic mechanism underlies dexamethasone- and RU486-mediated fast suppression of arachidonic acid release (Chivers et al., 2004).

Glucocorticoids have also been shown to rapidly block epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulation of cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2) activation and cPLA2-mediated arachidonic acid release in A549 cells. Croxtall and collaborators have demonstrated that dexamethasone rapidly inhibits cPLA2 activation and arachidonic acid release downstream from the EGF receptor by blocking the activation of MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK) and ERK (Ahn et al., 1991; Croxtall et al., 2000; Croxtall et al., 1996; Croxtall et al., 1995; Croxtall et al., 2002; de Vries-Smits et al., 1992; Lin et al., 1993). The dexamethasone effect was inhibited by RU486, but not by blocking gene transcription. However, the inhibition by dexamethasone increased from 40% with short treatments (<5 min) to 70% with longer treatments, and the long-term effect was inhibited by blocking gene transcription, suggesting a combined non-genomic and genomic regulation of EGF-induced arachidonic acid synthesis by glucocorticoids. They showed that the non-genomic dexamethasone effect was caused by the inhibition of the phosphorylation of MEK1 and suppression of the MEK substrate ERK1, which prevented ERK1-mediated phosphorylation of cPLA2, thereby suppressing enzyme translocation to the membrane, and subsequent liberation of arachidonic acid (Croxtall et al., 2000; Lin et al., 1993). Taken together, these studies indicate that glucocorticoids prevent arachidonic acid release, at least in part, through a glucocorticoid receptor-dependent mechanism that abrogates the stimulated phosphorylation of cPLA2.

In a pituitary corticotroph cell line (AtT-20 cells), dexamethasone was able to suppress arachidonic acid synthesis stimulated by the bee venom polypeptide melittin (Pompeo et al., 1997). A 2-hour dexamethasone treatment caused a robust inhibition (up to 80%) of the early melittin-induced arachidonic acid release (1 min). The melittin effect has been traditionally thought to be due to its stimulatory effect on the secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) types I, II, and III, with no effect on cPLA2 (Cajal and Jain, 1997; Clark et al., 1987; Emmerling et al., 1993; Mollay et al., 1976; Rao, 1992; Steiner et al., 1993; Suzuki et al., 1991; Zeitler et al., 1991). However, a recent study showed that melittin causes the release of various free fatty acids (Lee et al., 2001). In this study, whereas PLA2 inhibitors had only minimal effects, phosphatidylinositol-phospholipase C and DAG lipase inhibitors exerted more robust inhibitory effects on melittin-induced release of arachidonic acid and palmitic acid. These results suggest that melittin-induced free fatty acid release involve multiple lipases. Further experiments showed that melittin also caused Ca2+ influx, but this did not appear to be a key factor in free fatty acid release (Lee et al., 2001). Therefore, glucocorticoid inhibition of melittin-induced release of arachidonic acid in AtT-20 cells is less dependent on the blockade of the melittin influence over cPLA2 phosphorylation state or Ca2+ influx and more on phosphatidylinositol-phospholipase C and diacylglycerol lipase activity. This suggests that melittin may act through multiple intermediates that converge on membrane phospholipid substrates for the formation of arachidonic acid.

It is possible, then, that glucocorticoids may cause a shift away from the use of these intermediates, making them unavailable for the synthesis of arachidonic acid, or may cause the conversion of arachidonic acid into other molecules, such as the arachidonic acid-derived endocannabinoids. Indeed, the melittin-induced Ca2+ influx and its stimulatory effect on phosphatidylinositol-phospholipase C and diacylglycerol lipase are changes that would be expected to favor endocannabinoid biosynthesis. We propose that non-genomic glucocorticoid actions in different cells may result in a shift in membrane lipid metabolism that favours the synthesis of the endocannabinoids AEA and 2-AG and a reduction in arachidonic acid.

5. Crosstalk Between Glucocorticoid-Induced Endocannabinoid Signaling and Pro-Inflammatory Mediators

5.1. Arachidonic acid metabolism

Arachidonic acid is a polyunsaturated fatty acid stored in membrane lipids of virtually all cells types, where it serves as a precursor to prostaglandins, leukotrienes, thromboxanes, endocannabinoids and related mediators and regulators of inflammation and neurotransmission. Neurons are rich in arachidonate containing lipids, but it seems that they are not capable of synthesizing arachidonic acid de novo from linoleate, a function that is fulfilled in the brain by astrocytes and endothelial cells (Calder, 2005; Iversen and Kragballe, 2000). Pro-inflammatory stimuli such as histamine and platelet-derived growth factor stimulate the release of arachidonic acid during the inflammatory response. In the nervous system, it can also be released in response to neurotransmitters, neuromodulators, and neuropeptides. Upon stimulation, free arachidonate is produced and released from the cell membrane by three distinct pathways: (1) PLD-catalyzed production of phosphatidic acid from phosphatidyl ethanolamine or phosphatidyl choline, followed by formation of diglyceride, monoglyceride and arachidonic acid; (2) PLC-mediated conversion of PI into DAG, followed by the action of DAG lipase and monoglyceride lipase to produce arachidonic acid and glycerol; and (3) PLA2 action on membrane phospholipids (Calder, 2005; Iversen and Kragballe, 2000; Seeds and Bass, 1999).

Once released, the free arachidonate has a short lifespan during which it can be rapidly esterified into membrane phospholipids, metabolized into eicosanoids or diffuse outside the cells, where it can modulate the activity of ion channels and protein kinases (DeGeorge et al., 1989; Horrocks, 1989). Free arachidonate can be metabolized by the action of three distinct classes of enzymes, cyclooxygenases, lipoxygenases, and cytochrome P450 (Fig. 1), all of which are expressed by neurons (Kozak et al., 2002; Sang and Chen, 2006). Cyclooxygenases 1 and 2 are the rate-limiting enzymes that participate in arachidonic acid metabolism to form protaglandins, prostacyclins or thromboxane A2 (Kozak et al., 2002). The lipoxygenases 5, 12 and 15 convert arachidonic acid into the corresponding hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acids (5-, 12- and 15-HPETEs) and dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid. These are subsequently converted to hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) by peroxidases, leukotrienes by hydrase and glutathione S-transferase, or lipoxins by lipoxygenases (Yamamoto, 1992). Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid and dihydroxyacids are formed by cytochrome p450 epoxygenase (McGiff, 1991).

5.2. Glucocorticoid inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis

Cyclooxygenases convert polyunsaturated fatty acids, including arachidonic acid, to precursors of potent bioactive molecules, such as prostaglandins, which are pro-inflammatory lipid mediators synthesized in response to interleukin-1. As reviewed by Kozak and co-workers (Kozak et al., 2002), prostaglandin biosynthesis depends on three distinct enzymatic steps: (1) phospholipase-dependent release of arachidonic acid from phospholipid pools; (2) cyclooxygenase-mediated oxygenation of arachidonic acid (or other liberated fatty acids) to generate the prostaglandin hydroxy-endoperoxide (PGH2); and (3) the conversion of PGH2 to prostaglandins, thromboxane or prostacyclin by distinct synthases. Two cyclooxygenase isoenzymes, cyclooxygenase-1 (COX1) and COX2, encoded by different genes, can convert arachidonic acid to PGH2, which is subsequently converted to prostaglandins by cell-specific isomerase and reductase activity. COX1 is a constitutively expressed housekeeping gene while COX2 is an immediate early gene which is expressed at low basal levels and is rapidly induced in response to a variety of inflammatory and proliferative stimuli, including cytokines, growth factors, and tumour promoters, and mediates prostaglandin biosynthesis in inflammatory cells and in the central nervous system (Dubois et al., 1998; Smith et al., 2000; Vane et al., 1998).

The cyclooxygenase enzymes are pharmacological targets for both non-steroidal drugs (e.g., aspirin) and steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as glucocorticoids. Synthetic glucocorticoids down-regulate inflammatory genes (Barnes, 1995) and present the most effective treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases such as asthma. In a human pulmonary cell line, COX2-mediated prostaglandin production is antagonized by dexamethasone (Mitchell et al., 1994), which suppresses COX2 synthesis by destabilizing COX2 mRNA. This effect, although post-transcriptional, was inhibited by the transcription blocker actinomycin D, suggesting that it involves dexamethasone-induced cellular factors in the rapid degradation of COX2 mRNA (Newton et al., 1998; Ristimaki et al., 1996); for a review see (Stellato, 2004).

Like arachidonic acid, both AEA and 2-AG are liberated from the cell membrane by phospholipases in a stimulus-dependent manner (Sugiura et al., 2002), and are selectively oxygenated by COX2, but not COX1. COX2-mediated 2-AG oxygenation was shown to generate PGH2 glycerol esters (PGH2-G) in cultured macrophages, whereas PGH2 ethanolamides (PG-H2EA) were produced by COX2-catalized oxygenation of AEA in human fibroblasts (Kozak et al., 2000; Yu et al., 1997). 2-AG was metabolized by COX2 as effectively as arachidonic acid, whereas AEA oxygenation by COX2 occurs with a micromolar Km, suggesting that this reaction may only occur in tissues in which high amounts of AEA are found (Kozak and Marnett, 2002).

PGH2-G and PG-H2EA represent a unique class of eicosanoids for which the biological function is largely unknown. In murine RAW cells, these endocannabinoid-derived eicosanoids served as precursors for glycerol esters and ethanolamides of the prostaglandin E2, prostaglandin D2, and prostaglandin F2α in reactions catalyzed by the respective prostaglandin synthases (Kozak et al., 2002). Similarly, PGH2-G and PG-H2EA served as substrates to produce the corresponding endocannabinoid-derived prostacyclin derivatives by prostacyclin synthases. It was also demonstrated that the sequential action of COX2 and thromboxane synthase on AEA and 2-AG can generate thromboxane A2 ethanolamide and thromboxane A2 glycerol ester, respectively. However, endocannabinoid-derived thromboxanes are produced at very reduced levels when compared with arachidonic acid, indicating that this pathway may not be as physiologically significant (Kozak et al., 2002). Other studies showed that PGH2-G was produced by murine primary resident peritoneal macrophages by lipopolysaccharide treatment (Rouzer and Marnett, 2005). The products of COX2-mediated oxygenation of AEA were shown to increase pulmonary arterial pressure via a mechanism that also depends on enzymatic degradation by fatty acid amide hydrolase into arachidonic acid products (Wahn et al., 2005). On the other hand, inhibition of COX2 by nimesulide potentiated AEA-induced relaxation of rat isolated small mesenteric arteries (Ho and Randall, 2007). These findings indicate physiological roles for the endocannabinoid-derived products of COX2 activity in the control of the immune response and blood pressure. On the other hand, they demonstrate that COX2 is also an important factor controlling endocannabinoid activity termination.

5.3. Endocannabinoid-derived prostanoid modulation of neuronal activity

There is also evidence for an endocannabinoid-derived prostanoid role in the modulation of synaptic activity in the CNS. Thus, in contrast to their endocannabinoid precursors, which cause suppression of inhibitory transmission in hippocampal neurons, the prostanoids produced by the sequential action of COX2 and the prostaglandin E, D and F synthases (PGE2-G, PGD2-G, PGF2α-G and PGD2-EA, but not PGE2-EA or PGE2α-EA), were shown to induce a concentration-dependent increase in the frequency of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents in cultured hippocampal neurons (Sang et al., 2006). This increase was not blocked by a cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist, but was attenuated by IP3 and MAPK inhibitors. These effects appeared to be mediated by prostanoid receptors distinct from the known receptors of the corresponding arachidonic acid-derived prostanoids. Furthermore, inhibition of COX2 activity reduced spontaneous inhibitory synaptic activity and augmented the cannabinoid CB1 receptor-dependent, depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI), suggesting that tonic COX2 activity controls both basal and depolarization-induced endocanabinoid levels. Accordingly, enhancement of COX2 activity not only stimulated the synaptic transmission but also abolished DSI (Sang et al., 2006). Interestingly, PGE2-G was also shown to stimulate hippocampal glutamatergic synaptic activity, revealed by an increase in the frequency of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents. These PGE2-G effects were not affected by cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists. Furthermore, the increased excitatory synaptic transmission induced by PGE2-G lead to a NMDA receptor-dependent neurotoxic effect, suggesting that the COX2 oxidative metabolism of endocannabinoids may contribute to inflammation-induced neurodegeneration, since endocannabinoids have been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects and to serve a neuroprotective function during inflammation in the CNS (Carrier et al., 2005; Correa et al., 2005; Eljaschewitsch et al., 2006; Ullrich et al., 2006).

5.4. Glucocorticoid-mediated shift in brain lipid metabolism

The dexamethasone-mediated post-transcriptional suppression of COX2 synthesis discussed above is consistent with a glucocorticoid-induced metabolic shift that favours the reduction of pro-inflammatory lipids in the brain with concomitant accumulation of arachidonic acid-derived, endocannabinoids (Fig. 1). In the brain, the glucocorticoid-induced inhibition of COX2-mediated oxidation of endocannabinoids is likely to serve as a neuroprotective mechanism, which may reduce neurotoxicity during inflammation or after activation of excitatory neuronal circuits during the acute phase of a stress response. Additionally, it seems reasonable to assume that the direct glucocorticoid-induced synthesis of endocannabinoids observed in the hypothalamus may also occur in other brain areas, including the hippocampus. Therefore, glucocorticoid-induced endocannabinoid synthesis (and / or its accumulation) may occur either by a direct mechanism, as we have demonstrated in the hypothalamus (Di et al., 2003; Di et al., 2005; Malcher-Lopes et al., 2006) or as a consequence of glucocorticoid-mediated inhibition of COX2 synthesis (Sang et al., 2006). The latter hypothesis is supported by the fact that COX2 inhibition enhanced endocannabinoid-mediated DSI in the hippocampus (Sang et al., 2006; Wilson and Nicoll, 2001). Indeed, it was demonstrated in another study that inhibition of COX2, but not the AEA degradative enzyme fatty acid amide hydrolase, prolongs DSI, suggesting that COX2 limits endocannabinoid actions temporally in the hippocampus (Kim and Alger, 2004). Interestingly, AEA has been shown to induce COX2 activity in cerebral microvascular endothelium at the transcriptional level (Chen et al., 2005). It is tempting to speculate that such a mechanism may integrate a complex stress/inflammatory state-dependent, self-regulated loop to control the ratio between pro-inflammatory lipids and endocannabinoids. Thus, on the one hand, the induction of COX2 by inflammatory factors such as interleukins favours the production of prostaglandins and endocannabinoid-derived prostanoids, with metabolism and reduction of endocannabinoid levels. On the other hand, elevated glucocorticoids would shift membrane lipid metabolism, leading to the reduction of prostaglandins and endocannabinoid-derived prostanoids, and the concomitant accumulation of endocannabinoids. The increase in endocannabinoids may in turn, at least in the case of AEA, lead to the concentration-dependent induction of COX2, thereby reducing endocannabinoids and closing the feedback loop. Such a hypothetical metabolic loop may explain how glucocorticoids and leptin cross-talk with inflammatory factors to control energy homeostasis and neurotoxicity during inflammatory states.

5.5. The hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus as a neuroimmune center

There is considerable evidence for the fundamental role of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus as an integrative immunomodulatory center that operates via neuroendocrine and pre-autonomic pathways to control energy and fluid homeostasis, glucocorticoid-mediated immunosuppression and behavioral changes (Yang et al., 1997). It has been shown that both glucocorticoids (Tempel et al., 1993) and cannabinoids (Verty et al., 2005) injected into the paraventricular nucleus cause increased appetite and weight gain. We have demonstrated that glucocorticoids cause the release of endocannabinoids in the paraventricular nucleus, reducing neuronal activation by suppressing glutamatergic synaptic inputs and facilitating GABAergic synaptic activity (Di et al., 2003; Di et al., 2005), which led us to propose that the orexigenic effect of local glucocorticoids are mediated by endocannabinoids in this hypothalamic nucleus (Malcher-Lopes et al., 2006). On the other hand, administration of IL-1β into the paraventricular nucleus was shown to stimulate neuronal activity and to induce anorexia and loss of body weight (Avitsur et al., 1997). As stated earlier, IL-1β is known to induce COX2 activity and is a major signal involved in the hypothalamic regulation of the neuroimmune response at the level of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus by influencing its pre-autonomic output as well as the synthesis and secretion of CRH, vasopressin, oxytocin and other stress-related mediators. Electrophysiological experiments demonstrated that IL-1β elicited a depolarization in paraventricular nucleus parvocellular and magnocellular neurons by inhibiting GABA synaptic inputs (Ferri and Ferguson, 2003; Ferri et al., 2005), and that this effect was mediated by prostaglandin synthesis (Ferri and Ferguson, 2005). The paraventricular neuron response to IL-1β and PGE2 was abolished by blocking spiking activity, suggesting that the IL-1β response was due to local GABA circuits. Additionally, IL-1β and PGE2 caused a direct hyperpolarization in putative GABAergic hypothalamic neurons surrounding the paraventricular nucleus, consistent with a role as IL-1β-sensitive inhibitory interneurons upstream from the paraventricular nucleus neuroendocrine cells (Boudaba et al., 1996). These findings clearly point to an opposing relationship between glucocorticoid- and IL1-β-mediated synaptic modulation of cells of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, which is consistent with their opposing roles in energy homeostasis and inflammation-associated regulation of hypothalamic neuroendocrine and pre-autonomic output. Furthermore, they demonstrate that IL-1β-mediated regulation of paraventricular neuronal activity involves COX2 induction and activation, which can be considered as circumstantial evidence that, in the presence of IL-1β, glucocorticoid-induced endocannabinoids in the paraventricular nucleus are likely to serve as substrate for COX2 oxygenation to form prostanoids, which may contribute to remove the cannabinoid CB1 receptor-mediated suppression of excitation induced by glucocorticoids in paraventricular neurons. Therefore, it seems that the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus circuitry contains all the molecular components necessary to carry on a regulatory loop centered on the glucocorticoid-dependent determination of the arachidonic acid metabolic fate in a nutrition and inflammation state- dependent fashion based on the levels of leptin and cytokines such as IL-1β. Low levels of the anorexigenic factors leptin and IL1-β is a permissive state that favors the glucocorticoid-induced production of arachidonic acid-derived endocannabinoids in the hypothalamus, which is likely to increase appetite. By contrast, if leptin is elevated, glucocorticoid-induced endocannabinoid synthesis is suppressed, whereas, if IL1-β is elevated, COX2 activation is likely to convert glucocorticoid-induced endocannabinoids to prostanoids.

It is noteworthy that, in addition to its central effects on appetite regulation, leptin acts as an indirect inflammatory signal within the brain, where it was shown to induce both IL1-β and COX2 (Inoue et al., 2006), further highlighting its role in the central coordination of energy homeostasis and the inflammatory/stress response. Leptin induces IL1-β expression in macrophages located in the meninges and perivascular space, whereas it causes COX2 induction in endothelial cells. Acting as an inflammatory agent, therefore, leptin stimulates COX2 activity in macrophages and endothelial cells, which would be expected to shift arachidonic acid and the arachidonic acid-derived endocannabinoid metabolism towards prostaglandin production. As a nutritional state-dependent modulator of energy homeostasis, leptin acts in the paraventricular nucleus to suppress glucocorticoid-induced release of endocannabinoids. In both cases, leptin's actions tend toward the prevention of endocannabinoid accumulation.

5.6. Peripheral crosstalk between glucocorticoid-endocannabinoid signaling and inflammatory mediators

Glucocorticoid-mediated increases in peripheral endocannabinoid biosynthesis would allow for activation of the mostly peripheral CB2 receptors widely expressed among cells of the immune system. Similar to centrally expressed cannabinoid CB1 receptors, the peripheral CB2 receptors mediate an inhibition of their target cells. In addition to its central action via the CB1 receptor, AEA displays potent immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory activities by interacting with peripheral cannabinoid CB1 receptor and/or cannabinoid CB2 receptors. Therefore, glucocorticoid-mediated inhibition of prostaglandins and increase of endocannabinoids function to suppress the immune response in concert. For example, lipopolysaccharide, which elicits a well-known arachidonic acid-mediated inflammatory response, has been shown to increase AEA levels over 10-fold in mouse macrophages via CD14-, NF-κB-, and ERK1 / ERK2-dependent activation of the AEA synthetic enzymes N-acyltransferase and phospholipase D. It has also been shown to induce the AEA degradative enzyme fatty acid amide hydrolase (Liu et al., 2003). 2-AG has been shown to be stimulated by rat platelets and macrophages after lipopolysaccharide stimulation (Di Marzo et al., 1999a; Varga et al., 1998). Recently, an inhibitory role for cannabinoid CB1 receptor activation has been shown in an animal model of lipopolysaccharide-induced fever (Benamar et al., 2007). Non-hypothermic doses of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55,212 were used to reduce lipopolysaccharide-induced fever in a manner sensitive to cannabinoid CB1 receptor-, but not cannabinoid CB2 receptor-specific antagonists in rats. A similar reduction was also seen when THC (the main psychoactive cannabinoid present in marijuana) was used. Furthermore, plasma concentrations of lipopolysaccharide-induced increases in IL-6 were significantly decreased by the synthetic cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55,212. Therefore, under conditions of HPA axis activation, increased circulating concentrations of glucocorticoids play a central role in activating rapid non-genomic pathways that ultimately serve to decrease the overall activity of the immune system and specifically the inflammatory response in a manner that likely favours a shift in the utilization of arachidonic acid as a precursor for endocannabinoid biosynthesis rather than through the COX pathway leading to the formation of prostaglandins.

6. Conclusions

We have attempted to show how glucocorticoids may generate a rapid anti-inflammatory response by promoting arachidonic acid-derived endocannabinoid biosynthesis via non-genomic and post-transcriptional mechanisms. According to our hypothesized model, a non-genomic action of glucocorticoids results in the global shift of membrane lipid metabolism, subverting metabolic pathways toward the synthesis of the anti-inflammatory endocannabinoids AEA and 2-AG and away from the pro-inflammatory mediators arachidonic acid and prostaglandins. Post-transcriptional inhibition of COX2 synthesis by glucocorticoids assists this mechanism by suppressing the synthesis of prostaglandins as well as endocannabinoid-derived prostanoids. In the CNS this may represent a major neuroprotective system, which may cross-talk with leptin signaling in the hypothalamus to allow the coordination of energy homeostasis and the inflammatory response.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Shi Di for her outstanding scientific contributions to the body of work that comprises our portion of the data presented in this review. We would also like to thank Katalin Halmos for her excellent technical work that went into these studies. This work was supported by NIH grants MH066958 and MH069879.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Ahn NG, Seger R, Bratlien RL, Diltz CD, Tonks NK, Krebs EG. Multiple components in an epidermal growth factor-stimulated protein kinase cascade. In vitro activation of a myelin basic protein/microtubule-associated protein 2 kinase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4220–4227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alger BE, Pitler TA, Wagner JJ, Martin LA, Morishita W, Kirov SA, Lenz RA. Retrograde signalling in depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition in rat hippocampal CA1 cells. J Physiol. 1996;496(Pt 1):197–209. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison JP, Havran WL. The immunobiology of T cells with invariant gamma delta antigen receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:679–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.003335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarneh BA, Simpson ER. Detection of aromatase cytochrome P450, 17 alpha-hydroxylase cytochrome P450 and NADPH:P450 reductase on the surface of cells in which they are expressed. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1996;119:69–74. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(96)03796-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameri A. The effects of cannabinoids on the brain. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;58:315–348. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwell JD, Lu FW, Vacchio MS. Glucocorticoids in T cell development and function*. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:309–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avitsur R, Pollak Y, Yirmiya R. Administration of interleukin-1 into the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus induces febrile and behavioral effects. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1997;4:258–265. doi: 10.1159/000097345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JM. New mechanisms for effects of anti-inflammatory glucocorticoids. Biofactors. 1991;3:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger CM, Schulte HM, Chrousos GP. Molecular determinants of glucocorticoid receptor function and tissue sensitivity to glucocorticoids. Endocr Rev. 1996;17:245–261. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-3-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barna I, Zelena D, Arszovszki AC, Ledent C. The role of endogenous cannabinoids in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis regulation: in vivo and in vitro studies in CB1 receptor knockout mice. Life Sci. 2004;75:2959–2970. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ. Inhaled glucocorticoids for asthma. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:868–875. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503303321307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ, Adcock I. Anti-inflammatory actions of steroids: molecular mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1993;14:436–441. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90184-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beato M, Chavez S, Truss M. Transcriptional regulation by steroid hormones. Steroids. 1996;61:240–251. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(96)00030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CA, Estes PA, Bona BJ, Muro-Cacho CA, Nordeen SK, Edwards DP. The steroid antagonist RU486 exerts different effects on the glucocorticoid and progesterone receptors. Endocrinology. 1993;133:728–740. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.2.8344212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltramo M, Piomelli D. Carrier-mediated transport and enzymatic hydrolysis of the endogenous cannabinoid 2-arachidonylglycerol. Neuroreport. 2000;11:1231–1235. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200004270-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltramo M, Stella N, Calignano A, Lin SY, Makriyannis A, Piomelli D. Functional role of high-affinity anandamide transport, as revealed by selective inhibition. Science. 1997;277:1094–1097. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benamar K, Yondorf M, Meissler JJ, Geller EB, Tallarida RJ, Eisenstein TK, Adler MW. A novel role of cannabinoids: implication in the fever induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:1127–1133. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.113159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno T, MacCarrone M, De Petrocellis L, Jarrahian A, Finazzi-Agro A, Hillard C, Di Marzo V. The uptake by cells of 2-arachidonoylglycerol, an endogenous agonist of cannabinoid receptors. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:1982–1989. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno T, Melck D, De Petrocellis L, Di Marzo V. Phosphatidic acid as the biosynthetic precursor of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol in intact mouse neuroblastoma cells stimulated with ionomycin. J Neurochem. 1999;72:2113–2119. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudaba C, Szabo K, Tasker JG. Physiological mapping of local inhibitory inputs to the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7151–7160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-22-07151.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boumpas DT, Paliogianni F, Anastassiou ED, Balow JE. Glucocorticosteroid action on the immune system: molecular and cellular aspects. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1991;9:413–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivogel CS, Childers SR. The functional neuroanatomy of brain cannabinoid receptors. Neurobiol Dis. 1998;5:417–431. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brush FR, Dallman M, Jones MT, Tiptaft E. Proceedings: Corticosteroid feedback at the pituitary level. J Endocrinol. 1974;61:LXIV–LXV. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buren J, Liu HX, Jensen J, Eriksson JW. Dexamethasone impairs insulin signalling and glucose transport by depletion of insulin receptor substrate-1, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and protein kinase B in primary cultured rat adipocytes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;146:419–429. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1460419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadas H, Gaillet S, Beltramo M, Venance L, Piomelli D. Biosynthesis of an endogenous cannabinoid precursor in neurons and its control by calcium and cAMP. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3934–3942. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-12-03934.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajal Y, Jain MK. Synergism between mellitin and phospholipase A2 from bee venom: apparent activation by intervesicle exchange of phospholipids. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3882–3893. doi: 10.1021/bi962788x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder PC. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:423–427. doi: 10.1042/BST0330423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calignano A, La Rana G, Giuffrida A, Piomelli D. Control of pain initiation by endogenous cannabinoids. Nature. 1998;394:277–281. doi: 10.1038/28393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calignano A, La Rana G, Piomelli D. Antinociceptive activity of the endogenous fatty acid amide, palmitylethanolamide. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;419:191–198. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00988-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]