Abstract

Dictyostelium myosin II is activated by phosphorylation of its regulatory light chain by myosin light chain kinase A (MLCK-A), an unconventional MLCK that is not regulated by Ca2+/calmodulin. MLCK-A is activated by autophosphorylation of threonine-289 outside of the catalytic domain and by phosphorylation of threonine-166 in the activation loop by an unidentified kinase, but the signals controlling these phosphorylations are unknown. Treatment of cells with Con A results in quantitative phosphorylation of the regulatory light chain by MLCK-A, providing an opportunity to study MLCK-A’s activation mechanism. MLCK-A does not alter its cellular location upon treatment of cells with Con A, nor does it localize to the myosin-rich caps that form after treatment. However, MLCK-A activity rapidly increases 2- to 13-fold when Dictyostelium cells are exposed to Con A. This activation can occur in the absence of MLCK-A autophosphorylation. cGMP is a promising candidate for an intracellular messenger mediating Con A-triggered MLCK-A activation, as addition of cGMP to fresh Dictyostelium lysates increases MLCK-A activity 3- to 12-fold. The specific activity of MLCK-A in cGMP-treated lysates is 210-fold higher than that of recombinant MLCK-A, which is fully autophosphorylated, but lacks threonine-166 phosphorylation. Purified MLCK-A is not directly activated by cGMP, indicating that additional cellular factors, perhaps a kinase that phosphorylates threonine-166, are involved.

Although best known for its specialized role in muscle contraction, the myosin II motor protein also is involved in diverse processes in nonmuscle cells. Studies of genetically engineered myosin mutants revealed that myosin is required for cytokinesis in the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum when cells are grown in suspension (1–3) and for the construction of multicellular fruiting bodies from free-living Dictyostelium amebae (5). Although myosin is not necessary for cell locomotion and chemotaxis, these processes are less efficient in the absence of myosin (4). Myosin also contributes to tight capping of cell surface proteins at the rear of the cell in response to the lectin Con A. Upon Con A treatment, Dictyostelium lacking intact myosin can move cell surface proteins rearward, but this movement is slower than in wild-type cells and parallels the long axis of the cell without converging at the back (6). Thus, although looser aggregates of cell surface proteins sometimes are seen at the rear of myosin-deficient cells (7), tight caps such as those seen in wild-type cells are not formed (8–10).

The contractile activity of the myosin motor in smooth muscle and nonmuscle cells is activated by phosphorylation of the myosin regulatory light chain (RLC) subunit (reviewed in refs. 11 and 12). This phosphorylation increases the actin-activated ATPase activity of myosin and is carried out by myosin light chain kinase (MLCK). In animal cells, increased RLC phosphorylation is observed during mitosis (13–15), after exposure to chemoattractant (16), during colchicine-induced capping (17), in agonist-driven shape changes (18), and in response to adsorption of pathogenic bacteria to the intestinal cell surface (19). In Dictyostelium, activating RLC phosphorylation is induced after exposure to chemoattractant (20) and during Con A-induced capping (21). Both myosin heavy chain and RLC phosphorylation contribute to cortical tension (22). Surprisingly, Dictyostelium cells harboring a RLC mutant with an alanine at the phosphorylation site can still perform processes that require myosin, such as formation of tight caps and cytokinesis in suspension (23). However, the conservation of well-regulated RLC phosphorylation from Dictyostelium to mammals suggests RLC phosphorylation plays a significant role in governing myosin activity (reviewed in ref. 24). Alternate forms of regulation (such as myosin heavy chain phosphorylation; see ref. 12 for review) may complement or parallel RLC phosphorylation in coordinating the actomyosin cytoskeleton.

A myosin light chain kinase, MLCK-A, has been identified in Dictyostelium and the gene encoding it (mlkA) cloned (25–27). Genetic studies indicate a role for MLCK-A in cytokinesis. Cells lacking MLCK-A (mlkA−) are often multinucleate, although this phenotype is less extreme than that seen in cells lacking myosin heavy chain (21). Because mlkA− cells still contain phosphorylated RLC, MLCK-A and another unidentified MLCK may act in concert to promote cytokinesis (21).

In contrast to other MLCKs, Dictyostelium MLCK-A is not directly activated by Ca2+/calmodulin (25, 26). The activity of the enzyme is moderately increased upon autophosphorylation at threonine-289 (26, 28). This modification is apparently unregulated, and therefore would not allow the enzyme to respond to changing cellular conditions. Because the fully autophosphorylated Dictyostelium MLCK-A has ≈10,000-fold lower activity (26, 28) than other MLCKs (reviewed in ref. 29), it seems likely that an additional activation mechanism exists.

Experiments in which Dictyostelium cells are stimulated with Con A provide an opportunity to further dissect MLCK-A regulation. Treatment of Dictyostelium cells with Con A results in virtually quantitative phosphorylation of the RLC (21). This induction of RLC phosphorylation requires MLCK-A, as it does not occur in mlkA− cells. Con A treatment concomitantly induces phosphorylation of threonine-166 in the activation loop of MLCK-A, thereby activating the enzyme (28).

The signal that governs phosphorylation of threonine-166 is as yet unidentified, but cGMP is a strong candidate. In Dictyostelium, cGMP levels are thought to affect myosin heavy and light chain phosphorylation (reviewed in ref. 30). A peak in cGMP levels during chemotaxis (31) immediately precedes changes in the amount of RLC phosphorylation in developing cells (20), and mutants affecting this cGMP flux also alter RLC phosphorylation (32).

In this paper we explore the nature of MLCK-A regulation. Our findings suggest that the regulation of MLCK-A occurs via changes in enzyme activity rather than changes in enzyme localization. The increase in MLCK-A activity does not require the autophosphorylation site at threonine-289. In vitro, cGMP, in conjunction with an unidentified cellular factor, increases MLCK-A activity. A simple model encompassing these and previous (28) results is that MLCK-A is activated by phosphorylation of threonine-166 by a cGMP-dependent protein kinase. This model suggests a mechanism by which cGMP controls myosin activity during chemotaxis and cytokinesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

HS183 mlkA− cells (21) and their parent strain JH10 (ref. 33; referred to here as “wild type”) have been described. The T289A mutant is HS183 transformed with a plasmid containing an altered mlkA gene (28).

Media and Cell Culture.

Cells were grown axenically in HL-5 medium (34) in shaking culture to densities of 1–5 × 106 cells/ml. In some cases HL-5 was supplemented with FM medium (35) at a ratio of 3:1. For starvation, cells were shaken for 9 hr at a density of 2 × 107 cells/ml in MSB (MES starvation buffer: 20 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid-KOH, pH 6.8, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM CaCl2).

MLCK-A Assays.

For the assays in Figs. 2 and 4, cells were pelleted gently in a microcentrifuge, washed in MSB without CaCl2 (MSB-C), and resuspended at 1.3 × 107 cells/ml in MSB-C. Suspended cells (3 μl) were added to each assay tube and allowed to incubate at 22°C for approximately 5 min. For Con A-stimulated cells, cells were incubated with 30 μg/ml Con A (Sigma) in MSB-C for the indicated time. Cells were lysed by adding assay buffer. For kinase assays in Fig. 5, cells were replaced by various amounts of recombinant MLCK-A purified as described (28). The total assay volume was 10 μl with a final composition of 34 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 4.3 mM MgCl2, 0.43 mM DTT, 220 μM ATP, 1,000 μCi/ml [γ-32P]ATP, 0.4 mg/ml Dictyostelium myosin, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 4.3 mM NaF. Where indicated, assays were supplemented with 10 μM cGMP. Wild-type Dictyostelium myosin used as substrate in the assay was purified as described by Ruppel et al. (36). After 5 min at 22°C, reactions were terminated by the addition of 100 μl of 10% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and incubated on ice for at least 5 min. After centrifugation, pellets were neutralized with 2 μl of 0.5 M NaHCO3, solubilized in Laemmli sample buffer (37), and electrophoresed on 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Gels were Coomassie-stained to check for even loading and then dried and subjected to autoradiography. Bands were quantitated by using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager. Occasionally samples displayed high MLCK-A activity before treatment with Con A or cGMP, presumably caused by activation of this enzyme during growth or manipulation of the cells. Because MLCK-A was already fully activated at the beginning of the experiment, results from these sets of assays were excluded from our analysis.

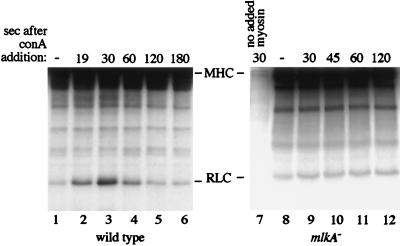

Figure 2.

Con A treatment of cells increases MLCK activity. Wild-type (lanes 1–6) and mlkA− (lanes 7–12) Dictyostelium cells were exposed to Con A for the times indicated and then lysed in assay buffer containing myosin and [γ-32P]ATP and incubated for 5 min. The kinase assays were terminated with TCA and the reaction products were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. The assay in lane 7 did not contain exogenous myosin (a small amount of myosin contributed by the cell lysate was present in all assays). The positions of the RLC and myosin heavy chain (MHC) are indicated. MHC is phosphorylated primarily by a heavy chain kinase that copurified with the myosin substrate added to the assay. These MHC bands are not seen in samples in which exogenous myosin has not been added to the assay (lane 7) and their phosphorylation is not altered by Con A addition.

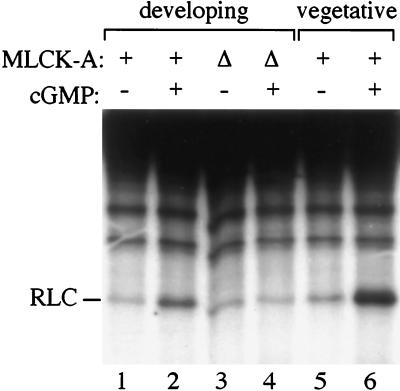

Figure 4.

cGMP increases MLCK-A activity in lysates from vegetative and developing cells. Growing cells (lanes 5 and 6) or cells starved in buffer (lanes 1–4) were lysed in assay buffer containing myosin substrate and [γ-32P]ATP. After 5 min, kinase assays were terminated and reaction products analyzed by SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. Lanes 1 and 2 and 5 and 6 contain extracts from wild-type cells; lanes 3 and 4 contain extracts from mlkA− cells. Assays in lanes 2, 4, and 6 contained 10 μM cGMP. The position of the RLC is shown.

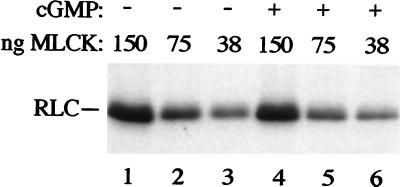

Figure 5.

cGMP does not directly activate MLCK-A. Recombinant MLCK-A was purified from bacteria and assayed in the presence of myosin substrate and [γ-32P]ATP. The amount of enzyme added to each assay is indicated. The reaction products were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. Assays in lanes 4–6 contained 10 μM cGMP. The position of the RLC is indicated.

To estimate the specific activity of MLCK-A in cGMP-containing lysates, vegetative JH10 cells were resuspended in 10 mM MES-KOH (pH 6.8) at 4 × 107 cells/ml. Lysates were prepared from an aliquot of the cells. Lysates and 50–400 pg of purified recombinant MLCK-A (28) were electrophoresed on 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and immunoblotted. Immunoblots were probed with affinity-purified antibody to MLCK-A (21) and an ECL kit (Amersham). The amount of MLCK-A in the lysate, as compared with the recombinant standards, was quantitated by using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager. Another aliquot of cells was further diluted in 10 mM MES-KOH (pH 6.8) to 4 × 106/ml. These cells (5 μl) were mixed with 5 μl of 2× reaction mix, which contained 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, 200 μCi/ml [γ-32P]ATP, 200 mM NaCl, 2 mg/ml Dictyostelium N464K myosin (28, 38), 2 mg/ml BSA, 2 mM DTT, 0.2% Triton X-100, 20 mM NaF, and 20 μM cGMP. The reactions were terminated by adding 10 μl of 2× Laemmli sample buffer and then processed as described (28). Assays were performed at 22°C and were linear over the 5-min time course used for these experiments.

Con A Treatment and Urea Gels.

To examine total RLC phosphorylation in Con A-treated cells, 3 × 106 cells were allowed to settle in a 60-mm Petri dish for at least 5 min. The adherent cells were washed in MSB and then covered with 2.5 ml of MSB, with or without 30 μg/ml Con A (Sigma). After a 5-min incubation at 22°C, cells were resuspended with a micropipettor, and 1 ml of the suspension was transferred to a tube containing 100 μl of 100% (wt/vol) TCA. After a 5-min incubation on ice, the precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge. The pellet was neutralized by addition of 3 μl of 0.5 M NaHCO3, resuspended in 2× urea sample buffer (9.1 M urea, 21 mM Trizma base, 192 mM glycine, 1.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT), and electrophoresed on urea gels according to the method of Perrie and Perry (39). These 8 M urea/polyacrylamide gels were modified from the original method to include a stacking gel containing 3.5% acrylamide, 0.13% bisacrylamide, 20 mM Trizma base, and 8 M urea. The gels were analyzed by immunoblotting with affinity-purified antibody against RLC (≈1 μg/ml; ref. 21). Bound antibody was visualized with an ECL detection kit (Amersham).

Immunoprecipitation of 32P-Labeled RLC.

Metabolic labeling of Dictyostelium with 32P and immunoprecipitation of RLC have been described (21). Labeled cells were treated with Con A for 1 min as in ref. 28.

Localization of MLCK-A in Con A-Treated Cells.

JH10 and HS183 cells were harvested in log phase, allowed to settle onto glass coverslips within a circle delimited by a hydrophobic PAP pen (Research Products International), and washed with oxygenated MSB. Forty microliters of 50 μg/ml fluorescein-isothiocyanate-labeled Con A (Sigma) in MSB was added to the cells. Approximately 25 sec after Con A addition, unbound Con A was removed by dipping the coverslip into oxygenated MSB. Cells were incubated in a humid chamber for the indicated times and then fixed in 1% formaldehyde in PBS (0.09% NaCl, 2.8 mM NaH2PO4, 7.2 mM Na2HPO4) for 10 min followed by acetone extraction at −10°C for 5 min. Coverslips were rinsed twice in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl and 150 mM NaCl for several min. Affinity-purified antibody against MLCK-A [ref. 21; approximately 3 μg/ml in a solution of 0.5% (wt/vol) BSA in PBS] was added to the cells. The coverslips were incubated with antibody for approximately 80 min in a humid chamber and then rinsed several times with PBS. Coverslips were incubated with rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (19 μg/ml; Cappel Research Products, Durham, NC) in 0.5% (wt/vol) BSA/PBS for 30 min. Unbound antibody was removed by three washes in PBS and a final wash with water. The coverslips were mounted in a drop of Mowiol (prepared as in ref. 40) with DABCO (Sigma) and examined using a fluorescence microscope.

RESULTS

Con A Treatment Does Not Alter MLCK-A Localization.

The Con A-induced increase in RLC phosphorylation (21) could reflect an increase in MLCK-A activity, a decrease in myosin light chain phosphatase activity, or a change in localization of myosin or MLCK-A that results in more efficient myosin phosphorylation. To address the last of these possibilities, we investigated the location of MLCK before and during Con A treatment. Because Dictyostelium myosin has been shown to accumulate beneath the Con A cap (41), we examined whether MLCK-A also became concentrated there. Adherent Dictyostelium cells were treated with fluorescein-isothiocyanate-labeled Con A for varying amounts of time and then fixed. Fixed cells were probed with antibody against MLCK-A and rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody (Fig. 1).

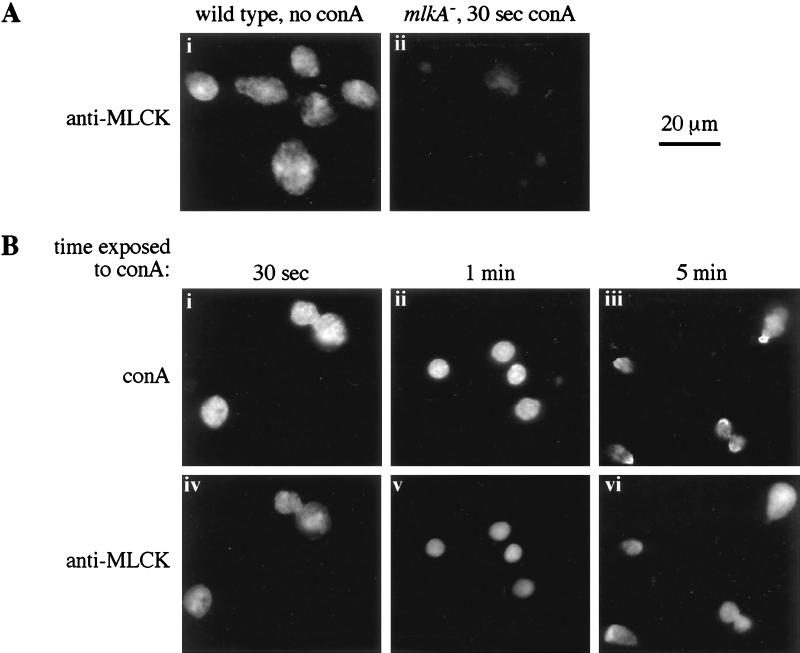

Figure 1.

MLCK-A does not accumulate in the actomyosin mesh beneath Con A caps. (A) MLCK-A staining in untreated wild-type and Con A-treated mlkA− cells. Adherent wild-type (i) and mlkA− (ii) Dictyostelium were treated with affinity-purified antibodies against MLCK-A. Rhodamine-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody was used to visualize the MLCK-A by indirect immunofluorescence. mlkA− Dictyostelium were treated with Con A for 30 sec before fixation and antibody treatment. The photograph in ii was exposed for twice the amount of time as those in Ai and Biv–vi. (B) MLCK-A localization in Con A-treated cells. Adherent wild-type cells were treated with Con A conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate. At the times indicated, the cells were fixed and probed with antibodies against MLCK-A as described above. i–iii show Con A staining and iv–vi show MLCK-A staining.

Before treatment with Con A, wild-type cells (JH10) displayed diffuse staining with MLCK-A antibody (Fig. 1A, i). The staining had a slightly reticular aspect, although we have not observed any association of MLCK-A with particulate material in cell fractionation studies (J.L.T. and L.A.S., unpublished data). Some of the staining, particularly that which appears nuclear, was nonspecific, as shown by faint fluorescence in cells lacking MLCK-A (Fig. 1A, ii).

After brief treatment of cells with Con A, this lectin could be seen distributed evenly over the cell surface (Fig. 1B, i). At longer times after treatment, the lectin typically was seen gathered at one end of the cell in a cap (Fig. 1B, iii). MLCK-A staining did not colocalize with the cap, but rather remained diffuse throughout the time course (Fig. 1B, iv–vi). In several cases, MLCK-A appeared to be diminished in the cap area (compare Fig. 1B, iii and vi).

Con A Treatment Activates MLCK-A.

Because Con A treatment was not observed to cause colocalization of myosin and MLCK-A, we investigated the possibility that MLCK-A activity was increased in response to Con A. To assay kinase activity after Con A treatment, we lysed cells in reaction buffer containing [γ-32P]ATP, the phosphatase inhibitor NaF, and myosin at various times after stimulation. After 5 min, reactions were terminated and subjected to SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. Con A treatment resulted in increased levels of MLCK activity, peaking at a 7-fold increase about 30 sec after stimulation (Fig. 2, lanes 1–6). The exact timing and magnitude of the activity peak varied between experiments; activation levels ranged from 2- to 13-fold, with the peak typically occurring within 1 min of Con A addition.

The increase in MLCK activity was caused by MLCK-A, as it did not occur in mlkA− cells (Fig. 2, lanes 7–12). In these cells there is at least one additional kinase capable of phosphorylating RLC in vivo (21). Unlike MLCK-A, this kinase did not alter its activity in response to Con A treatment (Fig. 2, lanes 8–12) and it demonstrated relatively little activity in these assays.

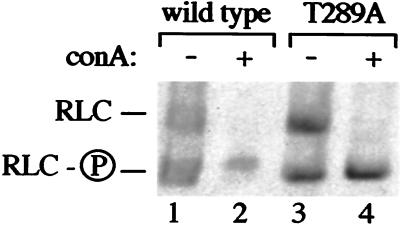

MLCK-A Can Be Activated in Vivo by an Autophosphorylation-Independent Mechanism.

Because autophosphorylation of MLCK-A has been shown to increase its activity (26), we wanted to investigate whether it was required for Con A-induced RLC phosphorylation. To address this question, lysates made from Dictyostelium cells treated with Con A or mock-treated were analyzed by electrophoresis on a urea/polyacrylamide gel, which separates phosphorylated and unphosphorylated RLCs (39). An immunoblot of the gel using antibody against RLC revealed that RLC was virtually quantitatively phosphorylated in response to a 5-min Con A treatment in both wild-type cells and in cells carrying MLCK-A T289A, a mutant MLCK-A lacking the autophosphorylation site (Fig. 3). Because kinetic MLCK assays, such as those shown in Fig. 2, demonstrate a peak in MLCK-A activity after approximately 1 min of Con A treatment, the persistence of RLC phosphorylation over the 5-min treatment period in this steady-state assay suggests that the phosphorylation is stable over the course of several minutes.

Figure 3.

Con A-induced phosphorylation of RLC does not require autophosphorylation of MLCK-A. Adherent Dictyostelium cells were treated with Con A (lanes 2 and 4) or mock-treated with buffer (lanes 1 and 3). After 5 min, the cells were resuspended and placed in TCA. TCA precipitates were solubilized in urea and electrophoresed in an acrylamide gel containing 8 M urea. The RLC was visualized by immunoblotting. RLC and RLC-P indicate the position of migration of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated RLC standards, respectively. Lanes 1 and 2 contain extracts from wild-type cells; lanes 3 and 4 contain extracts derived from cells carrying a mutant MLCK-A with an alanine residue substituted at the autophosphorylation site threonine-289.

We confirmed that RLC phosphorylation occurred in T289A cells by Con A treatment of Dictyostelium metabolically labeled with 32P. Immunoprecipitation of RLC from these cells, followed by quantitation of 32P in the immunoprecipitates, revealed that RLC phosphorylation was stimulated by Con A 1.6-fold in T289A cells (average of two experiments), a magnitude in agreement with that observed in the urea/polyacrylamide gel system. The largest stimulation of RLC phosphorylation observed in wild-type cells was 1.7-fold.

MLCK-A Is Activated Indirectly by cGMP in Cell Lysates.

Because a peak in cGMP levels (31) immediately precedes increases in RLC phosphorylation in developing cells (20), we tested whether cGMP could activate MLCK-A. Cells were starved to activate the developmental pathway and then lysed in reaction buffer containing myosin and [γ-32P]ATP, with or without cGMP. We found that cGMP stimulated myosin light chain kinase activity 2.5-fold (Fig. 4, lanes 1 and 2). The enhanced kinase activity depended on the presence of MLCK-A in the lysate; lysates from starved mlkA− cells did not exhibit increased kinase activity in the presence of cGMP (Fig. 4, lanes 3 and 4). Thus, the alternative kinase responsible for the low levels of RLC phosphorylation observed in the assays of mlkA− cells is not stimulated by cGMP.

If cGMP is the intracellular mediator for Con A-induced phosphorylation in vegetative cells, it should be able to stimulate kinase activity in lysates from vegetative cells as well as in developing cells. In lysates made from vegetative cells, cGMP stimulated kinase activity 3- to 12-fold over several experiments (Fig. 4, lanes 5 and 6, shows a 6-fold increase). Some aspect of the cGMP-dependent activation pathway was labile under these conditions; addition of cGMP to lysates that had been standing on ice for several minutes did not alter MLCK-A activity (L.A.S., unpublished data).

Recombinant MLCK-A undergoes autophosphorylation on threonine-289, but is devoid of threonine-166 phosphorylation in the activation loop (28). We observed that the activity of the endogenous MLCK-A present in the cGMP-treated lysates appeared to be substantially greater than that of recombinant MLCK-A, perhaps reflecting a role for threonine-166 phosphorylation in this pathway. To measure this effect, we first used quantitative immunoblotting to determine that there were approximately 120,000 MLCK-A molecules per Dictyostelium cell. At a myosin concentration of 3.6 μM (1 mg/ml), the activity of the MLCK-A in cGMP-treated lysates was 0.51 ± 0.18 s−1. This value is 210-fold higher than that of fully autophosphorylated recombinant MLCK-A (28). Thus, a cGMP-dependent mechanism exists for activating MLCK-A dramatically above the level achieved by autophosphorylation.

cGMP does not appear to activate MLCK-A directly. cGMP added to MLCK-A expressed in bacteria did not change the activity of the purified enzyme (Fig. 5; compare lanes 1–3 with lanes 4–6). Similar results were obtained with enzyme purified from Dictyostelium (J.L.T., unpublished data).

DISCUSSION

We have shown that treatment of intact Dictyostelium cells with Con A results in a rapid activation of MLCK-A and that cGMP can activate MLCK-A in cell lysates. Although these results may reflect distinct pathways of MLCK-A activation, the simpler interpretation is that cGMP is the intracellular mediator that causes MLCK-A activation when cells are treated with Con A. Con A is a tetravalent protein, and thus may crosslink membrane proteins (reviewed in ref. 42). Such crosslinking of membrane receptors could result in a burst of second messengers inside the cell. For example, Hadden et al. (43) found that Con A treatment of lymphocytes results in a 10- to 50-fold increase in intracellular cGMP levels. In Dictyostelium Con A potentiates the amount of cGMP produced in starved cells in response to cAMP, but does not alter the amount of cGMP produced in vegetative cells in response to the chemoattractant folate (44). However, in these experiments, cells were preincubated with Con A for several minutes before treatment with chemoattractant and measurement of cGMP levels. Thus, these experiments do not address the level of cGMP produced within the short (1 min) time frame of MLCK-A activation.

A role for cGMP in the regulation of MLCK-A is consistent with the observation of several investigators that cGMP fluxes are correlated with changes in myosin phosphorylation in vivo in Dictyostelium. Control of myosin phosphorylation by cGMP is seen during chemotaxis to cAMP and folate (reviewed in ref. 30) and in response to hyperosmotic shock (45). The relationship between myosin phosphorylation and cGMP is quite complex; genetic studies link cGMP fluxes during chemotaxis to changes in both myosin RLC and heavy chain phosphorylation and imply that cGMP both inhibits and enhances these phosphorylations. In streamer F mutants, which have a prolonged increase in cGMP after cAMP stimulation, both heavy chain and RLC phosphorylation are delayed, suggesting that high cGMP concentrations are inhibitory to phosphorylation (32, 46). In contrast, mutants unable to produce cGMP in response to cAMP stimulation fail to phosphorylate myosin, indicative of a requirement for cGMP in both types of myosin phosphorylation (32, 47). Our results directly address the nature of this requirement for cGMP in RLC phosphorylation: MLCK-A is indirectly activated by cGMP. Recent results by Dembinsky et al. (48) demonstrate that a myosin heavy chain kinase is also indirectly activated by cGMP. The apparent inhibitory nature of cGMP on myosin phosphorylation remains to be clarified.

The requirement for a cell lysate in the activation of MLCK-A by cGMP indicates that an additional cellular factor mediates activation. cGMP has multiple targets in cells: ion channels, phosphodiesterases, and protein kinases (reviewed in ref. 49). We recently have reported that MLCK-A is activated by phosphorylation of threonine-166 by an unidentified kinase (28). Thus, the simplest model is that MLCK-A is activated by phosphorylation on threonine-166 by a cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Con A treatment of cells results in a 6- to 7-fold increase in phosphorylation of threonine-166 (28); this corresponds well with the 3- to 12-fold increase in kinase activity measured here. MLCK-A in cGMP-treated lysates is 210-fold more active than recombinant MLCK-A. The more modest fold increase in activity observed in lysates could be explained by differences in basal activity levels; in vivo, MLCK-A has measurable basal levels of threonine-166 phosphorylation, whereas the recombinant kinase completely lacks this phosphorylation.

In smooth muscle cells, cGMP is a second messenger for nitric oxide and mediates muscle relaxation by indirectly inhibiting RLC phosphorylation (reviewed in ref. 49). In this context, increases in cGMP levels result in a lower concentration of intracellular calcium and thus bring about a decrease in the activity of the conventional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent MLCK. Although this is the major, and perhaps only, MLCK in muscle cells, in nonmuscle cells the regulation of RLC phosphorylation appears to be more complex. For instance, the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent MLCK can be activated by phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase (50). In addition, other kinases can phosphorylate RLC on activating sites (51, 52). Furthermore, the existence of MLCK-A-like kinases in other organisms has not been explored.

There are some striking parallels in the events that lead to RLC phosphorylation in Dictyostelium and in the nonmuscle cells of other organisms. For example, increases in RLC phosphorylation are seen during chemotaxis of polymorphonuclear lymphocytes (16) and during an agonist-induced shape change in platelets reminiscent of the “cringe” response in Dictyostelium (18). RLC phosphorylation also is increased in Dictyostelium under these circumstances (20). Con A-induced capping of cell surface proteins induces RLC phosphorylation in Dictyostelium (21) as does colchicine-induced capping in mouse lymphoma cells (17). Cytoskeletal changes during capping also bear similarity to those observed in intestinal cells during adhesion of pathogenic Escherichia coli (19). In both conditions, a patch of actin and myosin is formed under a specific region of the plasma membrane. In both situations, the level of RLC phosphorylation is increased dramatically, perhaps in response to patching of plasma membrane proteins.

Although the increases in RLC phosphorylation described above may be mediated by a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent MLCK, the association of at least some of these situations with increased cGMP levels is intriguing. It is unlikely that cGMP increases in platelets result in activation of an MLCK-A-like kinase, as cGMP appears to inhibit platelet aggregation and RLC phosphorylation (reviewed in ref. 49). In contrast, it is quite feasible that cGMP mediates phosphorylation during Con A capping; as noted above, cGMP levels are greatly increased during treatment of lymphocytes with Con A (43). Also, several studies implicate cGMP in promoting chemotaxis in neutrophils (reviewed in ref. 53). Unfortunately, the role of cGMP in neutrophil chemotaxis is not entirely clear as a few studies find it to be inhibitory, but the degree to which cGMP levels are increased appears to determine whether cGMP inhibits or promotes chemotaxis (53). Finally, increases in cGMP have been observed during mitosis in hepatoma cells (54). A cGMP-activated MLCK could serve to phosphorylate RLC in preparation for cytokinesis, during which increased levels of RLC phosphorylation are observed (13, 15). Thus, control of RLC phosphorylation by cGMP and an MLCK-A type kinase may be a common feature in many types of cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Taro Uyeda for Dictyostelium myosin substrate and helpful discussions, Tom Egelhoff for help with capping and immunofluorescence, and Peter Newell for sharing unpublished data. We thank Ray Deshaies for critical reading of the manuscript. L.A.S. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Muscular Dystrophy Association and University of Redlands Faculty Research Grants. J.L.S. was supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Muscular Dystrophy Association and the American Heart Association. This work was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant GM46551 (to J.A.S.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- MLCK

myosin light chain kinase

- MSB

MES starvation buffer

- RLC

myosin regulatory light chain

- TCA

trichloroacetic acid

References

- 1. De Lozanne A, Spudich J A. Science. 1987;236:1086–1091. doi: 10.1126/science.3576222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knecht D, Loomis W F. Science. 1987;236:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.3576221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manstein D J, Titus M A, De Lozanne A, Spudich J A. EMBO J. 1989;8:923–932. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wessels D, Soll D R, Knecht D, Loomis W F, De Lozanne A, Spudich J. Dev Biol. 1988;128:164–177. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters D J, Knecht D A, Loomis W F, De Lozanne A, Spudich J, van Haastert P J M. Dev Biol. 1988;128:158–163. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jay P Y, Elson E L. Nature (London) 1992;356:438–440. doi: 10.1038/356438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aguado-Velasco C, Bretscher M S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9684–9686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasternak C, Spudich J A, Elson E L. Nature (London) 1989;341:549–551. doi: 10.1038/341549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukui Y, De Lozanne A, Spudich J A. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:367–378. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.2.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egelhoff T T, Brown S S, Spudich J A. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:677–688. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.4.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sellers J R. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1991;3:98–104. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(91)90171-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan J L, Ravid S, Spudich J A. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:721–760. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.003445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamakita Y, Yamashiro S, Matsumura F. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:129–137. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mishima M, Mabuchi I. J Biochem. 1996;119:906–913. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeBiasio R L, LaRocca G M, Post P L, Taylor D L. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1259–1282. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.8.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fechheimer M, Zigmond S. Cell Motil. 1983;3:349–361. doi: 10.1002/cm.970030406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bourguignon L Y W, Nagpal M L, Hsing Y. J Cell Biol. 1981;91:889–894. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.3.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daniel J L, Molish I R, Rigmaiden M, Stewart G. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:9826–9831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manjarrez-Hernandez H A, Baldwin T J, Williams P H, Haigh R, Knutton S, Aitken A. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2368–2370. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2368-2370.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berlot C H, Spudich J A, Devreotes P N. Cell. 1985;43:307–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith J L, Silveira L A, Spudich J A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12321–12326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egelhoff T T, Naismith T V, Brozovich F V. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1996;17:269–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00124248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ostrow B D, Chen P, Chisholm R L. J Biol Chem. 1994;127:1945–1955. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammer J A., III J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1779–1782. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffith L M, Downs S M, Spudich J A. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:1309–1323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.5.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan J L, Spudich J A. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13818–13824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan J L, Spudich J A. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:16044–16049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith J L, Silveira L A, Spudich J A. EMBO J. 1996;15:6075–6083. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stull J T, Nunnally M H, Michnoff C H. In: The Enzymes: Control by Phosphorylation, Part A. Boyer P D, Krebs E G, editors. Vol. 17. Orlando: Academic; 1986. pp. 113–166. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newell P C. J Biosci. 1995;20:289–310. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mato J M, Krens F A, van Haastert P J M, Konijn T M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:2348–2351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.6.2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu G, Newell P C. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:1737–1743. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.7.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hadwiger J A, Firtel R A. Genes Dev. 1992;6:38–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sussman M. In: Dictyostelium discoideum: Molecular Approaches to Cell Biology. Spudich J A, editor. Orlando: Academic; 1987. pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franke J, Kessin R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:2157–2161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.5.2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruppel K M, Uyeda T Q P, Spudich J A. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18773–18780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laemmli U K. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruppel K M, Spudich J A. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1123–1136. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.7.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perrie W T, Perry S V. Biochem J. 1970;119:31–38. doi: 10.1042/bj1190031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab.; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carboni J, Condeelis J. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:1884–1893. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.6.1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin S S, Levitan I B. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:273–277. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90136-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hadden J W, Hadden E M, Haddox M K, Goldberg N D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:3024–3027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.10.3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mato J M, van Haastert P J M, Krens F A, Konijn T M. Cell Biol Int Rep. 1978;2:163–170. doi: 10.1016/0309-1651(78)90037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuwayama H, Ecke M, Gerisch G, van Haastert P J M. Science. 1996;271:207–209. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu G, Newell P C. J Cell Sci. 1991;98:483–490. doi: 10.1242/jcs.98.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu G, Kuwayama H, Ishida S, Newell P C. J Cell Sci. 1993;106:591–596. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.2.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dembinsky A, Rubin H, Ravid S. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:911–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lincoln T M, Cornwell T. FASEB J. 1993;7:328–338. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.2.7680013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klempke R L, Cai S, Giannini A L, Gallagher P J, de Lanerolle P. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:481–492. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amano M, Ito M, Kimura K, Fukata Y, Chihara K, Nakano T, Matsuura Y, Kaibuchi K. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20246–20249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Komatsu S, Hosoya H. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;223:741–745. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elferink J G R, VanUffelen B E. Gen Pharmacol. 1996;27:387–393. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zeilig C E, Goldberg N D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:1052–1056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.3.1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]