Abstract

Successful gene therapy depends on stable transduction of hematopoietic stem cells. Target cells must cycle to allow integration of Moloney-based retroviral vectors, yet hematopoietic stem cells are quiescent. Cells can be held in quiescence by intracellular cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p15INK4B blocks association of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)4/cyclin D and p27kip-1 blocks activity of CDK2/cyclin A and CDK2/cyclin E, complexes that are mandatory for cell-cycle progression. Antibody neutralization of β transforming growth factor (TGFβ) in serum-free medium decreased levels of p15INK4B and increased colony formation and retroviral-mediated transduction of primary human CD34+ cells. Although TGFβ neutralization increased colony formation from more primitive, noncycling hematopoietic progenitors, no increase in M-phase-dependent, retroviral-mediated transduction was observed. Transduction of the primitive cells was augmented by culture in the presence of antisense oligonucleotides to p27kip-1 coupled with TGFβ-neutralizing antibodies. The transduced cells engrafted immune-deficient mice with no alteration in human hematopoietic lineage development. We conclude that neutralization of TGFβ, plus reduction in levels of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27, allows transduction of primitive and quiescent hematopoietic progenitor populations.

To achieve durable gene therapy for diseases affecting blood cells, corrective DNA must be introduced into pluripotent human hematopoietic stem cells (HSC). Moloney murine leukemia virus-based retroviral vectors are currently the safest and most effective vehicles for transfer of DNA into target cells with stable integration (1–3). However, transduction of HSC is thwarted by the fact that these vectors require target cell mitosis (4), and most stem cells are in the G0/G1- phase of the cell cycle (5–8). Since the external factors that recruit HSC into cycle have not yet been identified, we hypothesized that a reduction in the levels of internal cell-cycle inhibitors could release HSC from quiescence to allow retroviral-mediated transduction.

Cell-cycle entry depends on the sequential formation and activation of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)/cyclin complexes CDK4/cyclin D, CDK2/cyclin E, and CDK2/cyclin A (9, 10). The assembly and activity of CDK/cyclin complexes are regulated by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKI). The CKI p15INK4B is induced by TGFβ (11, 12) and binds to CDK4 to prevent its association with cyclin D (12). Since CDK4/cyclin D activity is mandatory for the G1- to S-phase transition, TGFβ-mediated induction of p15 causes cell-cycle arrest. A second CKI, p27kip-1, has been shown to be elevated in quiescent fibroblasts (13). Unlike p15, which binds CDK4 and CDK6 monomers, p27 binds to CDK/cyclin complexes (14). At low levels, p27 binds to CDK4/cyclin D without altering its kinase activity (14, 15). At high levels, p27 binds to and inactivates CDK4/cyclin D and CDK2/cyclin E complexes, leaving the retinoblastoma protein in a hypophosphorylated state, preventing cell-cycle progression (16). p27 also acts through CDK2/cyclin E to negatively regulate cyclin A expression (17). Synthesis of cyclin A and activation of the CDK2/cyclin A complex are essential for S-phase progression (18).

In an attempt to stimulate quiescent human hematopoietic cells to enter the cell cycle, we modulated levels of the CKI p15INK4B and p27kip-1. Reduction of TGFβ levels by addition of neutralizing antibody (Ab) to the culture medium resulted in dramatic decreases in the levels of p15 in primary human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors, with a concomitant increase in the levels of colony formation and M-phase-dependent retroviral transduction. However, the most primitive cells within the CD34+ population [CD34+/38− and 4-hydroperoxycyclophosphamide (4-HC)-resistant CD34+ cells] did not enter the cell cycle when TGFβ was neutralized. These data indicated that there were additional factors holding the most primitive cells in the G0/G1-phase of the cell cycle.

Serum withdrawal and cell-to-cell contact elevate p27 levels and cause quiescence in fibroblasts (14–18), but the mechanisms regulating p27 expression and activity are unknown in hematopoietic cells. Cytokine addition, modulation of serum content, and loss of contact do not release HSC from quiescence. We report here that a reduction in p27 levels after treatment with antisense oligonucleotides (ONs), together with neutralization of TGFβ, promoted cell-cycle progression in quiescent human hematopoietic progenitors without inducing differentiation. The entry of a portion of the cells into S phase was evidenced by induction of cyclin A and Ki67 expression, and increased levels of M-phase-dependent, retroviral-mediated gene transfer were documented in vitro and after long-term engraftment in immune-deficient mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transduction of Human Hematopoietic Cells.

CD34+ progenitors were isolated from normal human bone marrow by immunomagnetic selection, as described (19). Use of the samples was approved by the Childrens Hospital Los Angeles Committee for Clinical Investigation. Elimination of cycling cells by 4-HC treatment was performed, as previously published (20). CD34+/38− cells were isolated from human marrow by preenrichment of CD34+ cells by using Miltenyi columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter acquisition by using a stringent gate, as described (5). Cells were cultured in serum-containing (2) or serum-free medium (Ex-Vivo 15, BioWhittaker) with the cytokines interleukin (IL)-6, stem cell factor (SCF), IL-3, and Flt3 ligand (FL), all used at 10–50 ng/ml, from BioSource International (Camarillo, CA). Supernatant from the LN retroviral vector, packaged in the producer cell line PG13 (21) and collected as described (22), was added to cells on the COOH-terminal domain of fibronectin [Retronectin, Takara Shuzo, Otsu, Japan (23)], with and without addition of neutralizing Ab to TGFβ (panspecific rabbit anti-human, R & D Systems) used at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml. C-5 propyne-modified phosphorothioate ONs synthesized by Operon Technologies (Alameda, CA) were used at a final concentration of 50 μM in serum-free medium (Ex-Vivo 15). The sequence for the antisense ON (anti-p27) was 5′-qgC GUC UGC UCC AcagF-3′ (F indicates fluorescein), and the scrambled, or missense ON was 5′-qgC AUC CCC UGU Gca gF-3′, as described previously (24).

Mice.

In some experiments, after the designated transduction period, cells were washed and transplanted as described (19, 25) into immune-deficient beige/nude/xid mice bred at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles. Mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation 12 mo after transplantation and marrow and tissues were collected and analyzed, as previously published (19, 25).

Assay for Transduction of Clonogenic Progenitors.

After the transduction period, cells were washed twice and plated in methylcellulose-based medium to assess colony formation with and without the selective agent G418 [Geneticin, 0.9 mg/ml active (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY)], as described (19). Colonies were enumerated on day 21, then clones that had attained a size of at least 200 cells in the presence of G418 were plucked from the methylcellulose and DNA was isolated as described (2, 25).

Human-specific colony-forming unit (CFU) plating and cloning of individual human T cells and myeloid progenitors was done from the marrow of long-term engrafted immune-deficient mice, as described (25). Genomic DNA was extracted from individual colonies and clones and was analyzed for the presence of the LN provirus by PCR for the neomycin (neo) gene (19). After confirmation of vector integration, the clonal integration pattern was assessed by subjecting DNA from each colony to amplification in an inverse PCR reaction, as described (2, 25).

Immunoblotting.

Cells (100,000 or 500,000) were incubated ±anti-TGFβ and ON for the indicated times at 37°C, with 5% CO2. Pelleted cells were then lysed on ice for 10 min (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4/250 mM NaCl/2 mM EDTA/2 μg/ml aprotinin/1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride/1 mM NaF/0.5 μg/ml leupeptin/1% Nonidet P-40). The cleared lysates were boiled in SDS sample buffer at 95°C and electrophoresed on SDS/10% or 12% polyacrylamide gels, then transferred onto Hybond membranes (Amersham). Immunoblotting was done as described (26) by using Abs to p15 (K-18), p27 (M-197 or F-8), and cyclin A (H-432) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Membranes were stripped in 0.1 M glycine (pH 2.5) and reprobed with an anti-actin Ab (I-19) as a loading control.

Immunohistochemistry.

After incubation with anti-TGFβ Ab and/or antisense ON to p27 for 18 hr, 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells were centrifuged onto charged glass slides. Slides were fixed in acetone, then blocked for 15 min at room temperature with Qualex reagent (BioGenex/ABN). The mAb to Ki67 (Immunotech, Marseille, France) was introduced onto the slides at a 1:1,000 dilution in Qualex, then incubated at 25°C for 15 min. The SuperSensitive StreptAvigen Kit with fast red chromogen was used for detection (BioGenex/ABN).

Statistical Analyses.

All analyses were performed by using the excel 5.0 software (Microsoft). Average values are listed with standard deviations. SEM was used if all values were listed in table format to show the range. The significance of each set of values was assessed by using the two-tailed t test assuming equal variance.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Neutralization of TGFβ Reduces Levels of the CKI p15 and Causes an Increase in Hematopoietic Colony Formation.

TGFβ has been demonstrated to inhibit division of hematopoietic progenitors (27–29). The molecular mechanisms by which TGFβ inhibits cell-cycle progression have been reported for fibroblastic cells (12–13) but have not yet been determined for primary human hematopoietic progenitors. To define the impact of TGFβ at both the cellular and molecular levels, CD34+ cells isolated from eight different normal human bone marrow samples were used. Cells were first transduced with supernatant from the PG13/LN packaging cell line, in serum-free medium on fibronectin (FN) (30–32) in the presence or absence of a TGFβ-neutralizing Ab. After transduction, cells were washed twice and plated for colony formation with or without G418, which selects for the presence of the neomycin-resistance (neo) gene carried by the LN vector. Addition of anti-TGFβ Ab resulted in statistically significant increases in both total and G418-resistant colony formation. The number of total colonies that grew from 3,000 cells was 770 ± 51 with addition of anti-TGFβ Ab and 526 ± 41 without addition (n = 8, P < 0.05). The number of colonies that grew in G418 was 311 ± 29 with anti-TGFβ Ab and 133 ± 13 without addition (n = 8, P < 0.05). Therefore, the extent of transduction was increased from 25 ± 7% to 40 ± 3% by addition of anti-TGFβ Ab (P < 0.05).

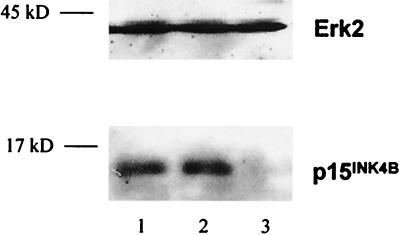

Western blot analyses were done at different time points to assess the effect of addition and neutralization of TGFβ on levels of the CKI p15 in primary human bone- marrow-derived CD34+ cells. The levels of p15 were not significantly elevated by addition of TGFβ, suggesting that the induction of p15 by the levels of TGFβ present in the medium was already maximal (Fig. 1). In contrast, 12 hr after incubation with neutralizing Ab to TGFβ, levels of p15 protein were undetectable by Western blotting (Fig. 1). Levels of β-actin (not shown) and the mitogen-activated protein kinase protein ERK2 (Fig. 1) were unchanged, indicating that there were equivalent levels of protein in all lanes and no nonspecific toxicity to the cells.

Figure 1.

Immunoblotting analysis of CD34+ cells from normal human bone marrow cultured with anti-TGFβ Ab showed a selective reduction in the levels of the CKI p15. Marrow-derived CD34+ cells were cultured in serum-free medium with IL-3, IL-6, and SCF for 12 hr, with addition of TGFβ or neutralizing Ab to TGFβ. After 12 hr, cells were collected and immunoblot analysis was done by using Abs against p15 and ERK2. Lane 1, medium alone; lane 2, medium + 5 ng/ml TGFβ; and lane 3, medium + anti-TGFβ Ab.

Next, the effects of TGFβ neutralization were examined in a more primitive hematopoietic progenitor population, 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells. 4-HC has been shown to kill cycling cells while sparing quiescent repopulating progenitors (33, 34). 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells isolated from human bone marrow were 100% negative for immunohistochemical staining with an anti-Ki67 mAb, demonstrating that they were in the G0-phase of the cell cycle (6). 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells from eight marrow donors were transduced in medium containing IL-3, IL-6, SCF, and FL. All transductions were done on FN in serum-free medium, with and without addition of anti-TGFβ Ab. Supernatant from the PG13/LN cell line was added after a 12-hr preincubation. Twelve hours later, cells were collected, and colony-forming assays were plated with and without G418. In all cases, there was a significant increase in colony formation from 10,000 cells when anti-TGFβ Ab was added (190 ± 21 vs. 85 ± 14 without addition, n = 8, P < 0.05). However, transfer of the neo gene into 4-HC-resistant CD34+ progenitors was not significantly increased by neutralization of TGFβ, in contrast to the results obtained with the total CD34+ cell populations. Accordant with these data, there was no increase in the percentage of cells that were positive for immunohistochemical staining with an anti- Ki67 Ab 18 hr after addition of anti-TGFβ Ab, confirming that the cells had not yet exited the G0-phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 2B).

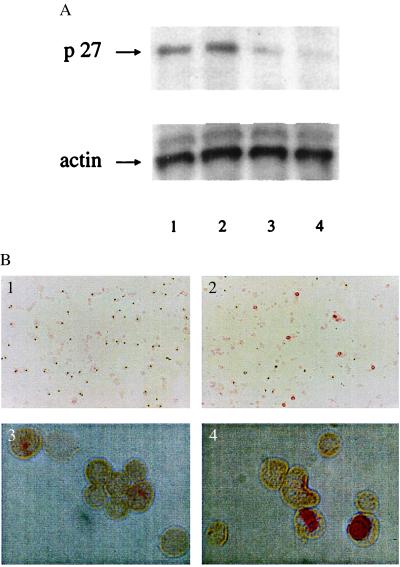

Figure 2.

The combination of anti-TGFβ and antisense ON to p27kip-1 increased the percentage of 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells exiting G0. 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells were incubated in serum-free medium with cytokines, ±anti-TGFβ Ab, ±antisense ON to p27 for 18 hr. (A) Levels of p27 protein were tested by immunoblotting. Lane 1, cells incubated in medium alone; lane 2, medium + anti-TGFβ Ab; lane 3, medium plus anti-p27 ON; and lane 4, medium with anti-TGFβ Ab + anti-p27 ON. (B) Levels of the Ki67 protein were assessed by immunohistochemistry. (1) Cells incubated with anti-TGFβ Ab alone. (×8.5.). (2) Cells incubated with anti-TGFβ Ab + anti-p27 ON (×8.5.). (3) Cells incubated with anti-TGFβ Ab alone (×85.). (4) Cells incubated with anti-TGFβ Ab + anti-p27 ON (×85.).

We had determined that reduction in extracellular TGFβ levels by incubation with anti-TGFβ Abs significantly reduced the levels of the p15 inhibitor in CD34+ cells (Fig. 1). However, neutralization of TGFβ was insufficient to allow exit of 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells from G0 during the period of exposure to the vector, as detected by a lack of retroviral-mediated transduction. An absence of expression of the protein Ki67, which is induced on entry from G0- to G1-phase, confirmed this observation (Fig. 2B). These data indicated that another intracellular protein could be inhibiting cell-cycle entry in the more primitive 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells. A candidate for the second inhibitor was the protein p27kip-1, which had been shown previously to be elevated in quiescent fibroblasts (14, 18).

To investigate the importance of p27 in maintaining the quiescence of 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells, we chose to reduce its levels using an antisense ON. A C-5 propyne-modified phosphorothioate 16-mer was used, with a missense control ON that bore the same modifications (24), chosen to increase stability (35). A fluorescein tag was added to the 3′ end of both ONs to facilitate tracking into the cell. We determined that the optimal method for achieving entry of the ON into primary hematopoietic progenitors was to use a concentration of 50 μM, without the use of lipofectants. This method resulted in specific reduction of p27 levels without affecting other pathways, such as mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation in response to cytokines (data not shown). After an 18-hr incubation with the anti-p27 ON, CD34+ cells showed high levels of fluorescence. To verify that the ON had entered the cytoplasm, rather than just being bound to the membrane, cells were incubated for a total of 24 hr with the ON, with samples taken each 6 hr for analysis. Each sample was soaked for one additional hour in DNase plus RNase to destroy surface ON, then cells were subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis. An average of 68% of the cells had incorporated ON at the 12- and 18-hr time points. By 24 hr, the average number of cells that were positive for incorporation of the ON had decreased to 23% (data not shown).

The effects of antisense p27 ON incorporation on colony formation from human hematopoietic cells was tested. CD34+ progenitors from bone marrow were incubated for 16 hr in serum-free medium in the presence of antisense p27 or missense ON vs. no treatment. After the incubation period, cells were washed, counted, and plated for colony formation. Addition of the missense ON did not significantly alter the extent of CFU production (1,270 ± 421 CFU grew from 10,000 missense-treated cells vs. 1,172 ± 499 untreated, n = 8, P > 0.05). However, there was a significant increase in the number of colonies obtained from marrow-derived CD34+ cells incubated for 16 hr with the anti-p27 ON (2,007 ± 735 CFU, n = 8, P < 0.05 for anti-p27 vs. missense and untreated).

The effect of the anti-p27 ON on proliferation of 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells from human marrow was examined next. 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells were incubated ±anti-TGFβ Ab, ±antisense ON to p27 for 18 hr, then tested for levels of p27 protein by immunoblotting and for levels of the Ki67 protein by immunohistochemistry. Addition of antisense ONs to p27 caused a specific decrease in p27 levels (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4), without nonspecific reductions in protein levels, as demonstrated by rehybridizing the blot with an anti-actin Ab (Fig. 2A, Lower).

After incubation of 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells for 18 hr in serum-free medium with both anti-TGFβ-neutralizing Ab and anti-p27 ON, Ki67 staining demonstrated that an average of 11.2 ± 3.7% of the 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells had exited the G0-phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 2B; n = 4). CD34+ cells (4-HC resistant) incubated with anti-TGFβ-neutralizing Ab alone lacked detectable Ki67 expression (Fig. 2B).

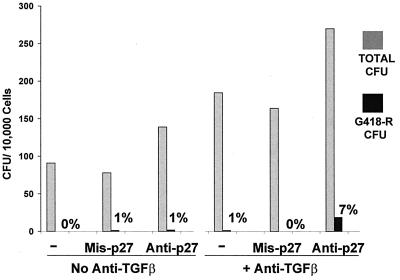

Next, the ability of 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells to be transduced was assessed after 12-hr preincubation on FN, in serum-free medium, ±anti-TGFβ Ab, with addition of missense, anti-p27, or no ON. After the preincubation period, an equal volume of PG13/LN supernatant was added, and incubation was continued for another 12 hr. Then, cells were plated in colony-forming assay with and without G418. Addition of anti-p27 ON significantly increased total CFU production both in the presence and in the absence of anti-TGFβ Ab, while the missense ON had no effect (Fig. 3). Transduction of a small percentage (7.4 ± 2.1%, n = 8) of the 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells was achieved only in the presence of both anti-TGFβ Ab and anti-p27 ON, but not with anti-TGFβ Ab alone (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Addition of anti-TGFβ and antisense ON to p27kip-1 increased both total and G418-resistant CFU production from 4-HC-resistant CD34+ cells. Cells were incubated for 12 hr in serum-free medium with cytokines on FN, with and without anti-TGFβ Ab, and with and without addition of missense or anti-p27 ON. After the preincubation period, supernatant from the PG13/LN cell line was added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 12 hr. A colony-forming assay was plated ±G418, and CFU were counted on day 21. The average of eight experiments is shown.

The effects of inhibitor neutralization on the 4-HC-resistant cells might have been minimized by trace amounts of the drug still present in cells that were then induced to cycle within 24 hr. Therefore, the effects of TGFβ and p27 neutralization on CD34+/38− cells, which are quiescent, noncycling progenitors (5–8), was examined next. We had previously shown that this primitive progenitor population engrafts immune-deficient mice to the same extent as a comparable number of CD34+ cells but is relatively refractory to retroviral-mediated transduction (36). Transduction in the optimized serum-free medium containing cytokines, anti-p27 ON, and anti-TGFβ-neutralizing Ab was compared with a standard transduction medium containing 25% fetal calf serum and cytokines (19). It had been determined previously that the latter medium resulted in poor transduction of CD34+/38− cells (36). CD34+/38− cells from four normal donors were incubated for 16 hr ± anti-TGFβ Ab and ±missense or anti-p27 ON, followed by addition of PG13/LN supernatant for an additional 12 hr. Cells were then washed twice and plated in colony-forming assay. Without neutralization of TGFβ and p27, very few colonies developed within 21 days, and there was no evidence of transduction, indicating a lack of entry of the cells into mitosis. Formation of colonies within a 3-week period and growth of G418-resistant CFU from the CD34+/38− cells was achieved only after transduction in the medium containing both anti-TGFβ Ab and anti-p27 ON (25.5 ± 5.7% total colonies, vs. 3.8 ± 3.2% from cells transduced in the standard medium, n = 4, P = 0.006). The extent of transduction was increased from zero to 24% by transduction in the optimized medium containing both anti-p27 ON and anti-TGFβ Ab.

Each colony that had grown in the selective agent G418 was confirmed to contain the LN vector by PCR for the neo gene. To verify that individual, primitive stem, and progenitor cells had been recruited into cell cycle to allow retroviral entry and integration, each colony was subjected to inverse PCR to determine the clonal integration pattern (2, 25). The inverse PCR technique identified a unique pattern for each colony (data not shown), indicating that multiple CD34+/38− cells had been stimulated into cell cycle by the use of anti-TGFβ-neutralizing Ab coupled with anti-p27 ON. These results indicated that causing a reduction in levels of the CKI p27 while neutralizing TGFβ leads to cell-cycle induction and an increase in the extent of M-phase-dependent, retroviral-mediated transduction of quiescent progenitors.

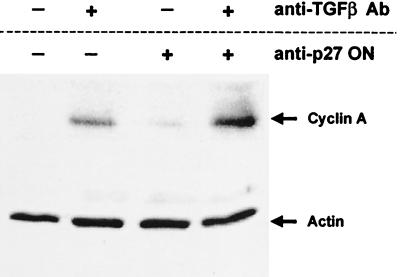

To show further that anti-TGFβ-neutralizing Ab and antisense ON to p27 induced cell-cycle entry, we examined cyclin A levels. Cyclin A is induced at the G1- to S-phase transition (17, 18). Immunoblot analyses were performed on CD34+ cells from human bone marrow, treated with anti-TGFβ alone, anti-p27 ON alone, or the combination of both anti-TGFβ and anti-p27 ON. Either anti-TGFβ Ab or anti-p27 ON used alone slightly increased levels of cyclin A protein, but the combination of both anti-TGFβ Ab and anti-p27 ON led to the most significant increase in cyclin A levels (Fig. 4). The induction of cyclin A by the combination of anti-TGFβ Ab and anti-p27 ON correlated with the increase in the number of cells that stained with the Ki67 Ab (Fig. 2), and the increase in retroviral-mediated transduction of quiescent cells (Fig. 3).

Figure 4.

Cyclin A levels are increased in primary human CD34+ cells cultured with anti-TGFβ Ab and anti-p27 ONs. Marrow-derived CD34+ cells were cultured in serum-free medium with IL-3, IL-6, and SCF for 16 hr, with and without anti-TGFβ Ab and anti-p27 ON. Cells were collected and lysed, and the lysates were run on SDS/PAGE, transferred to a membrane, and incubated with anti-p27 and anti-cyclin A Abs. The level of total cellular protein in each lane was assessed by immunoblotting with an anti-actin Ab.

To determine whether hastening induction of cell cycle by reducing p27 levels and neutralizing TGFβ altered the capacity of the cells to engraft and sustain multilineage differentiation, we used an immune-deficient mouse xenograft system. CD34+ cells from normal human marrow were precultured on FN in serum-free medium with cytokines alone (IL-3, IL-6, SCF, and FL) vs. cytokines, anti-TGFβ Ab, and anti-p27 ON for 12 hr. Then an equal volume of LN vector-containing supernatant was added to the cultures for an additional 12 hr. At the end of the transduction period, the cells from each arm of the experiment were collected, washed twice, and transplanted into groups of beige/nude/xid mice (n = 5), as described (19, 25, 36). One mouse died early from causes unrelated to the transplant. The other mice were killed 12 mo after transplantation, and marrow and tissues were analyzed for levels of human hematopoietic cell engraftment and retroviral marking. There was no significant alteration in the level of human cell engraftment or lineage development between cells cultured in the two conditions (Table 1). These data indicate that accelerating cell cycle through neutralizing TGFβ and reducing p27 levels during the 24-hr ex vivo culture period before transplantation did not induce significant differentiation of the most primitive, engrafting cells within the treated CD34+ population.

Table 1.

Human hematopoietic lineages recovered from the bone marrow of bnx mice 12 mo after transplantation

| Mouse no. | % Human cells of each lineage in bnx bone marrow

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD45 | CD4 | CD8 | CD33 | CD19 | |

| A1 | 18.0 | 4.9 | 4.0 | 8.1 | 2.9 |

| A2 | 6.6 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 1.4 |

| A3 | 11.4 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 5.6 | 0.3 |

| A4 | 11.5 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 3.9 | 1.3 |

| Average | 11.9 ± 2.3 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.5 |

| B1 | 5.9 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| B2 | 31.2 | 9.5 | 6.3 | 12.2 | 2.9 |

| B3 | 17.4 | 5.9 | 4.2 | 8.2 | 2.2 |

| B4 | 10.1 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 4.6 | 0.6 |

| B5 | 14.0 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 5.4 | 1.0 |

| Average | 15.7 ± 4.3 | 4.4 ± 1.5 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 6.5 ± 1.7 | 1.5 ± 0.4 |

Mice were harvested 12 mo after transplantation with human hematopoietic progenitors transduced by two methods: A. 12 hr preincubation on FN in serum-free medium with the cytokines IL-3, IL-6, SCF, and FL, followed by 12 hr with addition of an equal volume of supernatant from the PG13/LN packaging cell line. B. Identical conditions, but with 5 μg of anti-TGFβ Ab and 50 μM anti-p27 ONs added during the preincubation period. The harvested bnx/hu bone marrow was labeled with human-specific mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry, with 10,000 events acquired for each sample.

To determine whether transduction of primitive, engrafting hematopoietic cells had been achieved, bone marrow samples from each mouse were analyzed by PCR for the neo gene carried by the LN vector. There were no cells marked with the neo gene in the marrow of mice that had received cells transduced in medium with cytokines alone. These data indicate that the long-term engrafting cells within the CD34+ progenitor population were not stimulated by cytokines alone to enter cell cycle within the 24-hr period, to allow M-phase-dependent transduction by the retroviral vector LN. These findings were not surprising, since previous reports had shown that the majority of primitive hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells are not readily cytokine responsive and few begin to cycle until at least 48 hr after stimulation (5, 7, 8, 36).

In contrast, all mice transplanted with cells prestimulated for 12 hr on FN in serum-free medium with anti-TGFβ Ab and anti-p27 ON, then exposed to a 12-hr pulse of retroviral supernatant had cells marked by the neo gene in their marrow. Inverse PCR analysis of each marrow sample determined that at least six to eight individual, transduced human progenitor cells were contributing to hematopoiesis in the mice. To quantitate further the level of retroviral marking, human-specific CFU assays were done with and without the selective agent G418. An average of 54 ± 32 human colonies grew from mice that had received human CD34+ cells transduced with cytokines alone. There were no G418-resistant CFU that grew from those mice. Mice that had been transplanted with human CD34+ cells transduced in the presence of cytokines, anti-TGFβ, and anti-p27 ON had an average of 30.7 ± 12.8 G418-R CFU out of 88.7 ± 31.2 total, with an average transduction level of 30.6 ± 5.8%. These data indicate that through the use of anti-TGFβ Ab and anti-p27 ON to accelerate cell-cycle entry, a significant number of primitive, reconstituting cells were transduced by M-phase-dependent retroviral vectors within a 24-hr period, whereas through the use of cytokines alone, no primitive cells were transduced in the same period of time.

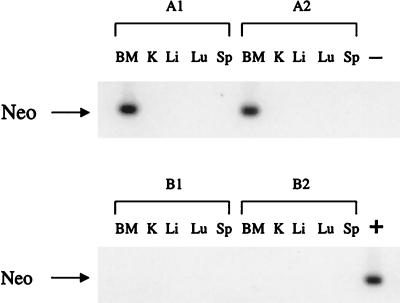

To ensure that the most primitive population of long-term engrafting cells could be transduced by using the anti-TGFβ Ab/anti-p27 ON strategy, and that the combination of TGFβ neutralization and p27 reduction, but not TGFβ neutralization alone, was required to achieve retroviral transduction within a 24-hr period, a second transplantation experiment was done. CD34+/38− cells from human bone marrow were precultured on FN in serum-free medium with cytokines, anti-TGFβ Abs, and missense p27 ON vs. with cytokines, anti-TGFβ Abs, and antisense p27 ON, for 12 hr. Then LN vector-containing supernatant was added to each culture for an additional 12 hr. At the end of the transduction period, the cells from each arm of the experiment were collected, washed twice, and transplanted into groups of beige/nude/xid mice (n = 4), as described (19, 25, 36). The mice were killed 12 mo after transplantation, and marrow and tissues were analyzed for levels of human hematopoietic cell engraftment and retroviral marking. Human CD45+ cell engraftment levels were equivalent between mice transplanted with cells treated with anti-TGFβ Ab and anti-p27 ON (12.0 ± 1.9% of the total marrow) and mice transplanted with cells treated with missense p27 ON and anti-TGFβ Ab (11.5 ± 0.6%). There was an equal distribution of the human hematopoietic lineages (T cell, B cell, myeloid, and progenitors) that had developed in the two groups. Bone marrow samples were analyzed further by neo PCR, inverse PCR, human-specific CFU plating for G418 resistant colonies, and single-cell cloning of individual T cells and myeloid progenitors, followed by inverse PCR as described (2, 25). Only mice that had been transplanted with human progenitors transduced in the presence of anti-TGFβ Ab and anti-p27 ON had neo gene-marked human cells in their marrow (Fig. 5). Marked human cells were not observed in the other tissues, in agreement with previously reported studies (19, 25). Equivalent numbers of human-specific colonies developed from the bone marrow of the two groups of mice, but G418-resistant CFU grew only from mice transplanted with human progenitors transduced with anti-TGFβ Ab and anti-p27 ON (average = 9.3% transduction).

Figure 5.

PCR for the neo gene in tissues from recipients of human bone marrow-derived CD34+/38− cells subjected to a 24 hr ex vivo transduction period with and without anti-p27 ON. Human CD34+/38− cells from human bone marrow were precultured on FN in serum-free medium with (A) cytokines, anti-TGFβ Abs, and antisense p27 ON, or (B) cytokines, anti-TGFβ Abs, and missense p27 ON for 12 hr. For each group, 1 and 2 refer to individual mice. LN vector-containing supernatant was then added for an additional 12 hr. The cells were transplanted into immune-deficient mice. Tissues were harvested 12 mos after transplantation, genomic DNA was isolated, and PCR for the neo gene carried by the LN vector was done. BM, bone marrow; K, kidney; Li, liver; Lu, lung; Sp, spleen.

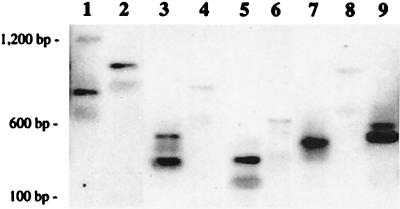

To assess further the levels of retroviral vector transduction of the primitive engrafting cells within the CD34+/38− population, inverse PCR analysis was done to determine the clonal diversity of the marked cells contributing to hematopoiesis. Both total bone marrow samples and individual T cell and myeloid clones were assessed as described (2, 25). Total marrow samples had an average of six readily detectable clonal integration patterns, by inverse PCR analysis. By single-cell cloning of human T cells and myeloid progenitors, additional patterns can often be revealed (37, 38). T cell clones had from four to nine different patterns, proving that multiple unique integration events had occurred (Fig. 6), and myeloid clones had an average of six unique patterns, corresponding with the bulk marrow analysis. Retroviral marking of multiple human hematopoietic clonogenic progenitors capable of long-term reconstitution was obtained only by transduction in the combination of anti-TGFβ Ab and anti-p27 ON. Transduction with anti-TGFβ Ab alone in a 24-hr period was insufficient to achieve marking of progenitors that could contribute to long-term human hematopoiesis in the mice.

Figure 6.

Clonal integration analysis of individual human T cell clones analyzed by inverse PCR. Individual human T lymphoid (CD45+/3+) cells recovered from a mouse transplanted with human CD34+/38− cells transduced for 24 hr in the presence of anti-TGFβ Abs and anti-p27 ON were sorted by automated cell deposition into 96-well plates. Clones were stimulated with nontransduced, irradiated allogeneic feeder cells, phytohemagglutinin, and recombinant human IL-2, as described (25). Human T lymphocytes were expanded individually, then genomic DNA was isolated, and a number of the clones were demonstrated by PCR to contain the neo gene. Clonal integration analysis was then performed (2, 25). Nine unique patterns are shown, indicating that nine lymphoid progenitors capable of long-term reconstitution in the mice were initially transduced within the CD34+/38− population.

In summary, the use of cytokines, serum-free medium, and anti-TGFβ was not sufficient to allow entry of the most primitive engrafting cells within the CD34+/38− population to cycle during a 12-hr prestimulation followed by a 12-hr exposure to vector supernatant. Reduction in the levels of p27 through use of antisense ONs in combination with the neutralization of TGFβ was necessary to allow retroviral marking of a portion of the primitive, engrafting cells in such a short period of time. Primitive hematopoietic progenitors induced into cell-cycle entry by the combination of anti-TGFβ Ab and anti-p27 ON were transduced by retroviral vectors in a 24-hr period and retained the ability to durably engraft immune-deficient mice with multilineage development. These data are significant, because it has been established that human hematopoietic stem cells differentiate over time in culture, so rapid transduction periods are highly preferable to extended ones. It has been shown previously that cells within the CD34+/38− population can be transduced at low levels after 5 days prestimulation in culture (36), but not in shorter periods of time. In the current studies, we have successfully accelerated the entry into cell cycle to accomplish the same outcome within 24 hr, rather than 5 days.

While we have demonstrated an increase in the cell-cycle-dependent, retroviral-mediated transduction of primitive, engrafting human hematopoietic cells in the current studies, other factors also must be considered, which could improve the levels even more if addressed. For instance, levels of the retroviral receptors RAM-1 and GALV-r have been reported to be very low in the most primitive subsets of hematopoietic cells (39). Temporary introduction of the genes encoding the receptors could lead to augmented levels of permanent integration of retroviral vector genomes, if coupled with the current strategies (40). Also, there could be other CDK inhibitors preventing cell cycle in different subsets of the hematopoietic cells that could be reduced to allow larger numbers of the cells to enter cycle.

The current studies provide a method for prompting a portion of the primitive human hematopoietic cells into cycle to allow increased levels of M-phase-dependent, retroviral-mediated transduction within a 24-hr period, without forcing differentiation. Moreover, these studies indicate that TGFβ and p27 play an important role in cell-cycle entry in primary, quiescent hematopoietic cells. The methods used in these studies represent a significant improvement in the ability to transduce primary, quiescent human hematopoietic stem cells without altering their capacity for subsequent engraftment and lineage development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Denise Carbonaro-Hall, Susan Smith, Craig Jordan, and Don Kohn for their invaluable help. J.N. was supported by a Career Development Award from the Childrens Hospital Los Angeles Research Institute, by a grant from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (SCOR #1-P50-HL54850) and by a James A. Shannon Director’s Award from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1RO1DK53041). N.T. was supported by grants from the Association Française contre les Myopathies, La Ligue, and the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer.

ABBREVIATIONS

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cells

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinase

- CKI

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- Ab

antibody

- ON

oligonucleotide

- 4-HC

4-hydroperoxycyclophosphamide

- IL

interleukin

- SCF

stem cell factor

- FL

Flt3 ligand

- CFU

colony-forming unit

- FN

fibronectin

- neo

neomycin

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

References

- 1. Williams D A. Hum Gene Ther. 1990;1:229–235. doi: 10.1089/hum.1990.1.3-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nolta J A, Kohn D B. In: Current Protocols in Human Genetics. Boyle A, editor. New York: Wiley; 1997. , unit 13.7, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nolta J A, Kohn D B. In: Stem Cell Handbook. Potten CS, editor. London: Academic; 1996. pp. 447–461. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller D G, Adam M A, Miller A D. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4239–4246. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.8.4239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hao Q L, Shah A J, Thiemann F T, Smogorzewska E M, Crooks G M. Blood. 1995;86:3745–3754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jordan C T, Yamasaki G, Minamoto D. Exp Hematol. (Charlottesville, VA) 1996;24:1347–1355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berardi A C, Wang A, Levine J D, Lopez P, Scadden D T. Science. 1995;267:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.7528940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponchio L, Conneally E, Eaves C J. Blood. 1995;86:3314–3324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherr C J. Cell. 1994;79:551–555. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinberg R A. Cell. 1995;81:323–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannon G J, Beach D. Nature (London) 1994;371:257–261. doi: 10.1038/371257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandhu C, Garbe J, Bhattacharya N, Daksis J, Pan C H, Koh J, Slingerland J M, Stampfer M R. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2458–2469. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polyak K, Kato J Y, Solomon M J, Sherr C J, Massague J, Roberts J M, Koff A. Genes Dev. 1994;8:9–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toyoshima H, Hunter T. Cell. 1994;78:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poon R Y C, Toyoshima H, Hunter T. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1197–1213. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.9.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vlach J, Hennecke S, Alevizopoulos K, Conti D, Amati B. EMBO J. 1996;15:6595–6604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zerfass-Thome K, Schulze A, Zwerschke W, Vogt B, Helin K, Bartek J, Henglein B, Jansen-Durr P. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:407–415. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pagano M, Pepperkok F, Verde F, Ansorge W, Draetta G. EMBO J. 1992;11:961–971. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nolta J A, Smogorzewska E M, Kohn D B. Blood. 1995;86:101–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenarsky C, Weinberg K, Petersen J, Nolta J, Brooks J, Annett G, Kohn D, Parkman R. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1990;6:425–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller A D, Garcia J V, von Suhr N, Lynch C M, Wilson C, Eiden M V. J Virol. 1994;65:2220–2224. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2220-2224.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauer G B, Valdez P, Kearns K, Bahner I, Wen S F, Zaia JA, Kohn D B. Blood. 1997;89:7–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dao, M. A., Hashino, K., Kato, I. & Nolta, J. A. (1998) Blood, in press. [PubMed]

- 24.Croix B S, Florens V A, Rak J W, Flanagan M, Bhattacharya N, Slingerland J M, Kerbel R S. Nat Med. 1996;2:1204–1210. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nolta J A, Dao M A, Wells S, Smogorzewska E M, Kohn D B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2414–2419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor N, Bacon K, Smith S, Jahn T, Kadlecek TA, Uribe L, Kohn DB, Gelfand EW, Weiss A, Weinberg K. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2031–2036. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eaves C J, Cashman J D, Kay R J, Dougherty G J, Otsuka T, Gaboury L A, Hogge D E, Lansdorp P M, Eaves A C, Humphries R K. Blood. 1991;78:110–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sitnicka E, Ruscetti F W, Priestley G V, Wolf N S, Bartelmez S H. Blood. 1996;88:82–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hatzfeld A, Batard P, Panterne B, Taieb F, Hatzfeld J. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:207–213. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.2-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moritz T, Patel V P, Williams D A. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1451–1460. doi: 10.1172/JCI117122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanenberg H, Xiao X L, Dilloo D, Hashino K, Kato I, Williams D A. Nat Med. 1996;2:876–885. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moritz T, Dutt P, Xiao X, Carstanjen D, Vik T, Hanenberg H, Williams D A. Blood. 1996;88:855–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones R J, Zuehlsdorf M, Rowley S D. Blood. 1987;70:1490–1494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharkis S J, Santos G W, Colvin M. Blood. 1980;55:521–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner R W. Nature (London) 1994;372:333–336. doi: 10.1038/372333a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dao M A, Shah A J, Smogorzewska E M, Crooks GC, Nolta J A. Blood. 1998;91:1243–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dao M A, Yu X J, Nolta J A. Exp Hematol. 1997;25:1357–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dao M A, Hannum C H, Kohn D B, Nolta J A. Blood. 1997;89:446–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orlic D, Girard L J, Jordan C T, Anderson S M, Cline A P, Bodine D M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11097–11102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bertran J, Miller J L, Yang Y, Fenimore-Justman A, Rueda F, Vanin E F, Nienhuis A W. J Virol. 1996;70:6759–6767. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6759-6766.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]