Abstract

A single amino acid mutation (W321F) in Mycobacterium tuberculosis catalase–peroxidase (KatG) was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis. The purified mutant enzyme was characterized using optical and electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, and optical stopped-flow spectrophotometry. Reaction of KatG(W321F) with 3-chloroperoxybenzoic acid, peroxyacetic acid, or t-butylhydroperoxide showed formation of an unstable intermediate assigned as Compound I (oxyferryl iron:porphyrin π-cation radical) by similarity to wild-type KatG, although second-order rate constants were significantly lower in the mutant for each peroxide tested. No evidence for Compound II was detected during the spontaneous or substrate-accelerated decay of Compound I. The binding of isoniazid, a first-line anti-tuberculosis pro-drug activated by catalase–peroxidase, was noncooperative and threefold weaker in KatG(W321F) compared with wild-type enzyme. An EPR signal assigned to a protein-based radical tentatively assigned as tyrosyl radical in wild-type KatG, was also observed in the mutant upon reaction of the resting enzyme with alkyl peroxide. These results show that mutation of residue W321 in KatG does not lead to a major alteration in the identity of intermediates formed in the catalytic cycle of the enzyme in the time regimes examined here, and show that this residue is not the site of stabilization of a radical as might be expected based on homology to yeast cytochrome c peroxidase. Furthermore, W321 is indicated to be important in KatG for substrate binding and subunit interactions within the dimer, providing insights into the origin of isoniazid resistance in clinically isolated KatG mutants.

Keywords: Catalase, peroxidase, isoniazid resistance, M. tuberculosis, KatG mutant, kinetic mechanism, spectroscopy

Isoniazid (isonicotinic acid hydrazide; INH) has historically been one of the most effective antibiotics against tuberculosis (Robitzek and Selikoff 1952) and continues to be used as a first-line drug to treat Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections. The mechanism of activation of this pro-drug is not fully understood, but it has been clearly shown that the catalase–peroxidase of M. tuberculosis, encoded by the katG gene, is required for mycobacterial sensitivity (Zhang et al. 1992, 1993). For example, the M. tuberculosis katG gene can confer INH sensitivity in resistant mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis and M. tuberculosis, and naturally resistant strains of Escherichia coli (Zhang et al. 1992; 1993). Also, mutations in the katG gene are among the major causes of INH resistance in clinical isolates from around the world (Marttila et al. 1996, 1998; Musser et al. 1996; Rouse et al. 1996), providing evidence for the functional requirement of the enzyme in vivo.

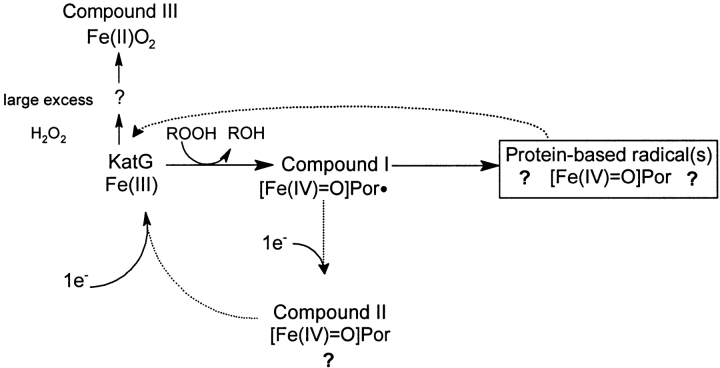

M. tuberculosis catalase–peroxidase (KatG) is a dimeric heme enzyme with homology to yeast cytochrome c peroxidase (CcP) and to plant peroxidases such as horseradish peroxidase (HRP), especially in the distal and proximal heme regions (Welinder 1991). The catalytic cycle of KatG bears some analogy to that of HRP, with optical evidence from stopped-flow spectrophotometry showing that KatG forms a Cmpd I analog. This oxyferryl iron-protoporphyrin IX: π-cation radical species is unstable, however, and it rapidly decays back to resting (ferric) enzyme without accumulation of other intermediates (Chouchane et al. 2000). Cmpd I in KatG is a catalytically competent intermediate that is apparently reduced by single-electron-transfer substrates including INH, although the optical spectrum of the second intermediate expected in the peroxidase cycle, Cmpd II (Dunford 1991, 1999), could not be identified. [Other authors have claimed identification of KatG Cmpd II based on the observation of a Soret peak at 430 nm when the resting enzyme was treated with peroxynitrite (Wengenack et al. 1999b), or upon addition of substrate to Cmpd I (Regelsberger et al. 2000), although in the latter case, the features of the optical spectrum more closely resembled those of the ferric enzyme, and in the former, the Soret maximum does not correspond to that of Cmpd II of peroxidases.]

Studies of purified mutant KatG enzymes are expected to provide insights into the mechanism of drug activation and the structure and function of catalase–peroxidases in general. For several mutant KatGs from drug-resistant strains, a correlation between decreased catalase–peroxidase activities and drug resistance has been reported (Rouse et al. 1996), although the origin of drug resistance is likely to involve factors beyond the moderate and variable alterations in basic enzyme activity observed. These other factors may include total enzyme levels expressed in the mutant strains, ability of the mutant KatGs to bind heme, the affinity of the mutants for the drug, as well as other unknown factors. The specific catalytic role of amino acids not associated with drug resistance has also been investigated in KatGs (Regelsberger et al. 2000). Our interest here lies in gaining insights into the mechanism of INH activation and how this process is damaged in mutant KatGs. One particular mutation, S315T, which is the most common drug-resistant mutation in M. tuberculosis KatGs, leads to an 80-fold increase in INH resistance although basic enzyme activities (catalase–peroxidase) are reduced by only 50%. A reduced affinity of this mutant for INH was also reported, although the drug apparently binds at the same site as in the wild-type enzyme (Wengenack et al. 1998; Todorovi et al. 1999). The S315T KatG also shows a reduced rate of superoxide-dependent INH oxidation (Wengenack et al. 1999a). These results show that this mutation does not lead to gross alteration in catalytic function, which is reasonable because M. tuberculosis KatG is important for virulence (Manca et al. 1999). Residue Ser-315 in KatG is considered homologous to Ser-185 in CcP and may be part of a heme access channel (Heym et al. 1995).

The point mutation W321G in M. tuberculosis KatG is also associated with INH resistance in a clinical isolate (Musser et al. 1996). Expression of M. tuberculosis KatG W321G in an INH-resistant Mycobacterium bovis BCG host strain yielded an enzyme with <30% of wild-type catalase and peroxidase activities, and the strain had a high level of drug resistance (MIC > 500 μg/mL compared with 0.05 μg/mL for wild type; Rouse et al. 1996). Although Trp-321 had seemed to be a homolog of Trp-191 in CcP, indicating that KatG could form Compound ES upon reaction with peroxide, optical spectroscopic results instead indicate Cmpd I (oxyferryl iron:porphyrin π-cation radical) formation in KatG (Chouchane et al. 2000). This intermediate is quite unstable, however, and is reduced back to the resting state without clear evidence for a typical Cmpd II, presumably owing to internal electron-transfer reactions; at least one of these reactions produces a tyrosyl radical in KatG (S. Chouchane, S. Girotto, Y. Yusupov, and R.S. Magliozzo, pers. comm.).

Here, we report the preparation of the mutant KatG(W321F) by site-directed mutagenesis, and the characterization of the recombinant protein. Optical stopped-flow spectrophotometric studies of the purified, overexpressed M. tuberculosis enzyme KatG(W321F) show formation of Cmpd I with various alkyl hydroperoxides. KatG(W321F) showed decreased catalase and peroxidase activities, a decreased rate of Cmpd I formation, and a decrease in affinity for isoniazid, compared with wild-type KatG. We also observed an increase in the stability of Cmpd I in the mutant, indicating that W321 may participate in or facilitate electron transfer to the peroxidase-cycle intermediates without stabilization of a tryptophan radical.

Results

The catalase–peroxidase KatG(W321F) used in these studies was produced in E. coli (UM262 strain) using an overexpression system carrying the mutated M. tuberculosis katG gene. For wild-type enzyme, the overexpression system generates polypeptide at a rate that overruns the heme biosynthesis capacity of the bacteria grown in LB medium. Addition of δ-aminolevulinic acid to growth media was found to greatly enhance the yield of KatG(W321F) holoenzyme similar to wild-type KatG (Chouchane et al. 2000), but for the mutant, heme-deficient enzyme was a much greater proportion of the total KatG isolated even in the presence of δ-aminolevulinic acid. The heme-deficient enzyme was separated from the holoenzyme during hydrophobic column chromatography on phenyl Sepharose (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech) and was not studied here. Pure KatG(W321F) was indistinguishable from wild-type enzyme on SDS-PAGE and in native polyacrylamide electrophoresis gels (data not shown). The optical purity ratio of the purified enzyme was A407/A280 ≥ 0.66, similar to wild-type KatG.

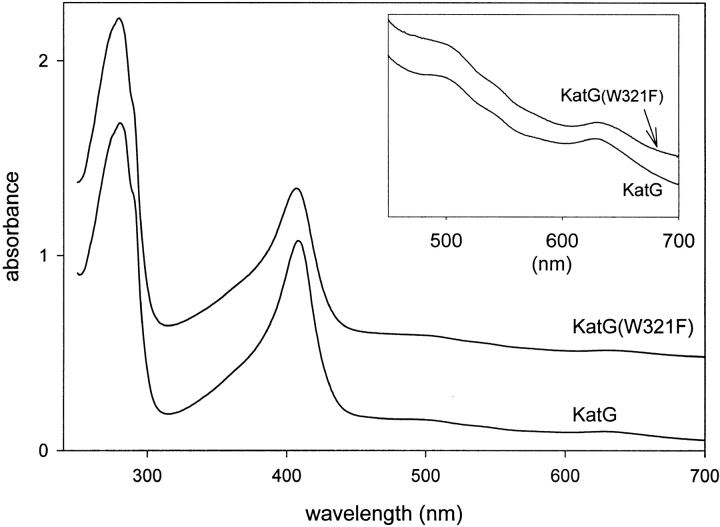

The optical spectrum of the resting enzyme was essentially the same as that of wild-type KatG (Fig. 1 ▶), reflecting a mixture of five- and six-coordinate high-spin and small amounts of six-coordinate low-spin iron species. Catalase and peroxidase activities of pure KatG(W321F) holoenzyme were reduced compared with the wild-type enzyme. For example, the catalase specific activity was 1524 U/mg, but the peroxidase specific activity was 0.17 U/mg. These values are 38% and 18% of the wild-type activities, respectively. [The accuracy of these activities relies in part on the extinction coefficient at the Soret maximum for evaluation of the enzyme concentration. Therefore, small differences in the relative amounts of five-coordinate and six-coordinate high-spin heme, as well as the content of low-spin heme that would alter the extinction coefficient at the Soret maximum, have not been accounted for. The error due to this type of inaccuracy is expected to be very small, because the optical spectrum of the purified enzyme is very similar to that of the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 1 ▶), except for a small increase in the content of low-spin heme in KatG(W321F) evident in a more prominent shoulder near 545 nm.]

Fig. 1.

Optical absorption spectra of ferric KatG (wild type) and KatG(W321F). Spectra are displaced along the Y-axis for clearer presentation.

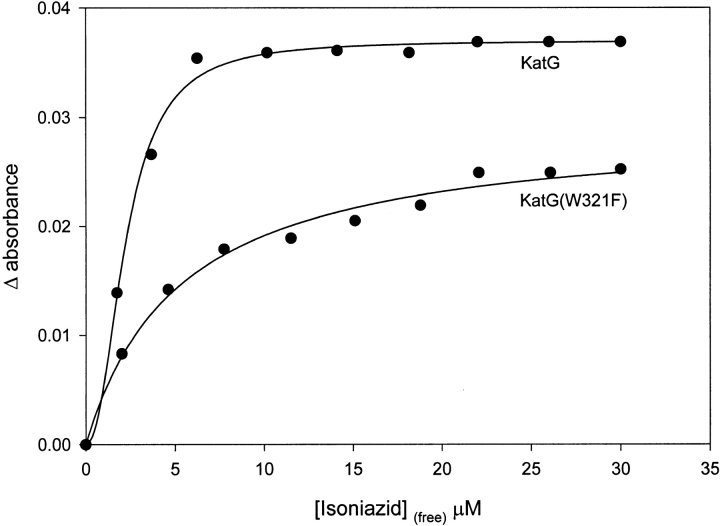

The affinity of KatG(W321F) for INH was evaluated using optical difference spectroscopy, and the results were compared with wild-type KatG (Fig. 2 ▶). For wild-type KatG, a sigmoidal binding isotherm was observed, and the data were fit to the Hill equation [isoniazid]0.5 = 2.2 ± 0.11 μM (similar to Wengenack et al. 1998), whereas for the mutant, the data were consistent with noncooperative binding. In this case, a hyperbolic function was used for fitting, giving a Kd = 5.4 ± 0.67 μM.

Fig. 2.

Optical difference data and fitted curves for titration of KatG and KatG(W321F) with isoniazid. Isoniazid affinities were evaluated by a least-squares fitting using the Hill equation (KatG) giving [isoniazid]0.5 = 2.2 μM; or a hyperbolic function [KatG(W321F)] giving Kd = 5.3 μM.

In stopped-flow optical experiments using small-to-large excesses of H2O2, no new species or intermediate was found (10 μM ferric KatG(W321F) mixed with <5 mM hydrogen peroxide). For higher concentrations of H2O2, an intermediate with absorbance maxima at 418 nm, 545 nm, and 580 nm was observed. These features match those of peroxidase Cmpd III (oxyferrous form) including that of KatG (Sanders et al. 1964; Wittenberg et al. 1967; Goodwin et al. 1997; Chouchane et al. 2000). The Cmpd III spectrum for KatG(W321F) quickly disappears as the spectrum of the resting enzyme returns, similar to the behavior of wild-type KatG (data not shown).

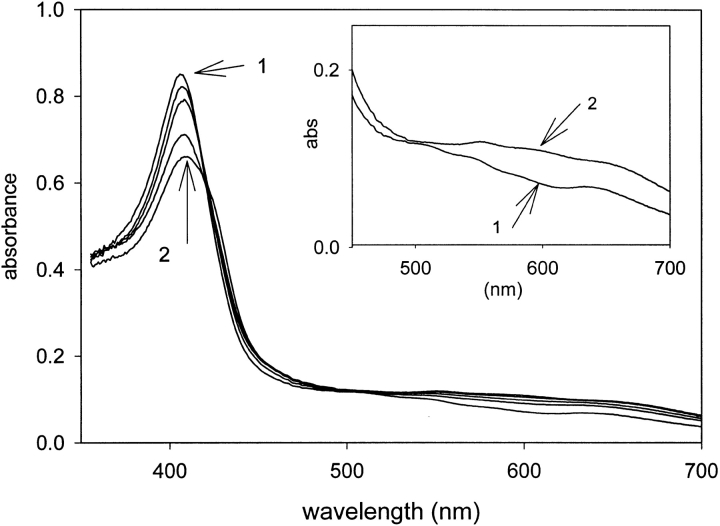

KatG(W321F) forms Cmpd I with alkyl peroxides such as t-butyl hydroperoxide, 3-chloroperoxybenzoic acid, or peroxyacetic acid. Figure 3 ▶ shows stopped-flow optical data for KatG(W321F) (9 μM) reacted with 300 μM CPBA. The product spectrum is characterized by a decreased Soret intensity (409 nm), whereas in the visible region, features consistent with the Cmpd I spectrum of wild-type KatG were observed, including shoulders near 550 nm and 590 nm and a feature at 655 nm. For the mutant, however, these features were not as clearly resolved as in wild-type KatG.

Fig. 3.

Optical stopped-flow absorption spectra of ferric KatG(W321F) and its Cmpd I. (1) Resting (ferric) enzyme; (2) Cmpd I formed from 9 μM enzyme plus 300 μM CPBA. (Inset) Visible region of spectra 1 and 2.

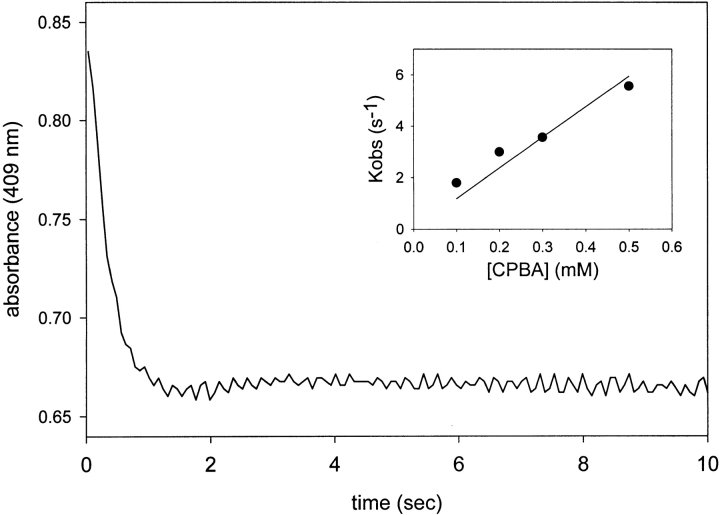

The second-order rate constants for formation of Cmpd I in KatG(W321F) were determined from the rates observed in stopped-flow experiments performed as a function of peroxide concentration (Fig. 4 ▶, inset). The rate constants show a dependence on the type of peroxide chosen (CPBA > PAA >>> tBOOH), but overall, the rates are reduced compared with the second-order rates for the similar reactions in wild-type KatG (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Optical stopped-flow kinetic data showing absorbance at 409 nm versus time during formation of KatG(W321F) Cmpd I. Enzyme, 9 μM; CPBA, 300 μM. (Inset) Linear dependence of the observed rates (Kobs) as a function of CPBA concentration.

Table 1.

Second-order rate constants for Cmpd I formation in M. tuberculosis KatG and KatG(W321F)

| Conditions | KatG (M−1 sec−1) | KatG(W321F) (M−1 sec−1) | Percent decrease vs. wild-type KatG |

| +tBOOHa | 25.4 | 15 | 40% |

| +CPBA | 3.1 × 104 | 9.4 × 103 | 70% |

| +PAA | 1.2 × 104 | 6.7 × 103 | 45% |

a In 10 mM TEA at pH 7.8; all others in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer at pH 7.2.

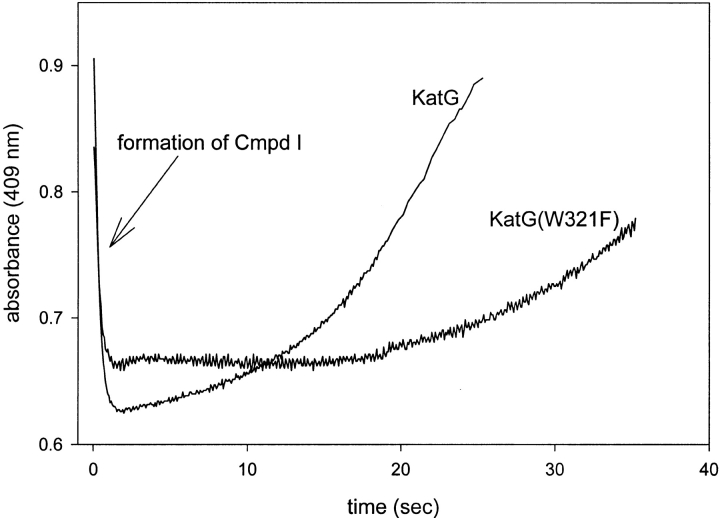

Figure 5 ▶ shows the time course of the reaction of KatG(W321F) during an extended incubation after mixing with CPBA. Here, the absorbance at 409 nm decreased due to formation of Cmpd I, and a steady state, during which no optical changes are apparent, persisted through 20–25 sec. The length of this interval depends on the concentration of peroxide. After cycling through Cmpds I and II and depletion of peroxide, the absorbance returns to its value in the ferric enzyme in a zero-order reaction. (The rate of this phase of the reaction was independent of peroxide concentration for both wild-type and mutant enzyme [data not shown]). For the experiment with wild-type KatG shown in Figure 4 ▶, the steady-state interval was shorter than in the case of KatG(W321F) because less peroxide was required to convert the resting enzyme to Cmpd I. The slope of the final phase of the optical change for the mutant was shallower (∼2.5-fold) than that for wild-type KatG. This result indicates a reduced rate of electron transfers that discharge the oxidized intermediate(s) in the mutant, compared with wild-type KatG.

Fig. 5.

Absorbance at 409 nm as a function of time during extended incubation of KatG and KatG(W321F) after mixing with peroxide. Traces were recorded after mixing ferric KatG(W321F) (9 μM) with 300 μM CPBA and ferric KatG (10 μM) with 100 μM CPBA.

The Cmpd I intermediate formed in KatG(W321F) was shown in double-mixing stopped-flow experiments to react very quickly with excess isoniazid, ascorbate, or potassium ferrocyanide, with behavior similar to that reported for wild-type KatG (data not shown) (Chouchane et al. 2000). This indicates that the catalytic competence of Cmpd I in the mutant is not greatly altered.

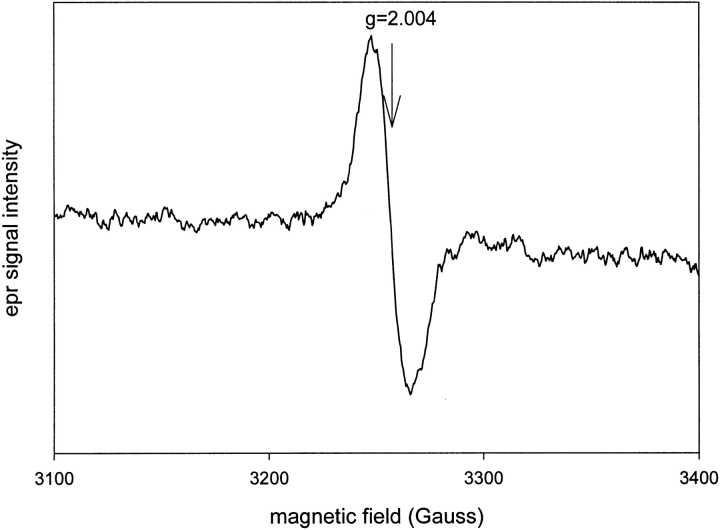

EPR spectroscopy of the product formed after a brief incubation (5–10 sec) of KatG(W321F) with excess peroxyacetic acid showed the same protein-based radical species formed in the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 6 ▶) and is assigned as a tyrosyl radical. The analogous spectrum formed in wild-type KatG had been previously assigned to the porphyrin π-cation radical of Cmpd I (Chouchane et al. 2000).

Fig. 6.

Electron paramagnetic resonance spectrum of KatG(W321F) freeze-quenched after 10 sec incubation with peroxyacetic acid. The sample was prepared as described in Materials and Methods. The spectrometer conditions were as follows: time constant, 1.0 sec; temperature, 77 K; power, 10 mW; receiver gain, 4000; modulation amplitude, 3.2 G; frequency 9.126 GHz.

Discussion

Site-directed mutagenesis was used to produce a mutant katG gene, and the mutant enzyme KatG(W321F) was overexpressed in E. coli and purified. The optical spectrum of the resting KatG(W321F) enzyme is nearly indistinguishable from that of wild-type KatG. Also, the fluoride- and cyanide-bound forms showed the same optical spectra as the analogous complexes of the wild-type enzyme. In contrast to these similarities, the catalase and peroxidase activities of KatG(W321F) are reduced by 60% and 80%, respectively, and the rate of Cmpd I formation with various alkyl peroxides is reduced between two- and threefold compared with wild type. The affinity for isoniazid was decreased approximately threefold, and the binding was noncooperative. These losses in catalytic ability and drug affinity are factors that could contribute to drug resistance of KatG mutants at position 321 in the M. tuberculosis enzyme. It should be noted that no profound loss of catalase–peroxidase function occurs in this mutant, similar to KatG(S315T) and other drug-resistant KatG enzymes, supporting the idea that KatG activity is essential for bacterial virulence. Furthermore, there are many other factors that could further contribute to isoniazid resistance in vivo, which have not been examined here. Nevertheless, residue 321 is conserved in KatGs and is undoubtedly important for proper INH binding and therefore activation.

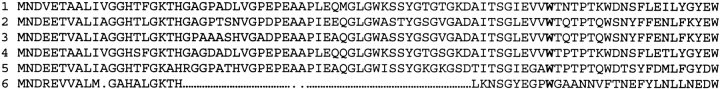

The increased stability of Cmpd I in KatG(W321F) may implicate W321 in direct electron transfer to Cmpd I (or Cmpd II), which, in the wild-type enzyme, results in a more rapid discharge of these intermediates. Alternatively, conformational rearrangements arising from the replacement of phenylalanine for tryptophan in the mutant may alter the rate of electron transfer from other residues near the heme that discharges the intermediates. The finding that tyrosyl radical is responsible for the EPR signal of the product of the reaction of resting enzyme with peroxide in the mutant and wild-type enzymes indicates that at least part of this pathway involves tyrosine. No EPR evidence for a stable radical formed on tryptophan was found in the experiments on wild-type KatG, but this does not rule out participation of this side chain in the electron-transfer pathway that discharges oxidized intermediates. Sequence homology between KatGs and CcP noted by others strongly indicated functional homology between these enzymes. For example, primary sequence alignments show homologies and identities within the regions containing residues 312–341 of bacterial catalase–peroxidases, and 182–211 of CcP, including the conserved tryptophan in question (Fig. 7 ▶). Preceding this conserved region and starting at 312 in bacterial catalase–peroxidases, however, is a 35-amino-acid insertion. These extra residues may displace or misorient the conserved region containing W321 and thereby preclude oxidation of the Trp and/or stabilization of the radical as in Cmpd ES. It should be noted that mutation of W191 in CcP did not result in a major change in the catalytic cycle; although that residue has been proven to be the site of the stable radical in Cmpd ES, other amino acids in CcP can be oxidized by Cmpd I (Mauro et al. 1988; Erman et al. 1989). The tentative assignment of a tyrosine radical in the catalytic cycle of M. tuberculosis KatG mentioned above also shows divergent catalytic function for KatG compared with yeast and plant peroxidases. Ongoing studies of the mechanism of KatG and the change in function for mutants will continue to provide an understanding of the role of this enzyme in isoniazid activation and other fundamental functions of KatG.

Fig. 7.

Alignment of primary structures of bacterial catalase–peroxidases and yeast cytochrome c peroxidase. The amino acid sequence surrounding the proximal histidine and the conserved tryptophan of interest, M. tuberculosis KatG(W321), is shown. (1) M. tuberculosis KatG (257–341); (2) E. coli KatG (HPI) (254–338); (3) Salmonella typhimurium KatG (255–339); (4) Mycobacterium intracellulare KatG (264–348); (5) Bacillus stearothermophilus KatG (249–333); (6) cytochrome c peroxidase (163–211) (Heym et al. 1995).

Materials and methods

All standard chemicals and reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Isonicotinic acid hydrazide (INH) was recrystallized from methanol before use. Restriction nucleases, polynucleotide kinase, DNA ligase, and the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase were obtained from New England Biolabs, Inc.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

Phagemid pBluescript II KS+ (pKS II+; Stratagene) was used for cloning, mutagenesis, and sequencing. The plasmid pKAT II was used as an overexpression vector for KatG (Johnsson et al. 1997) and as the source for the katG gene that was cloned into pKS II+ to generate pSY15 used for mutagenesis. E. coli strain DH5α (F−, φ80dlacZDM15D[lacZYA-argF]U169deoRrecA1endA1hsdR17(rk−, mk+)phoAsupE441−thi-1gyrA96relA1) was used as a host for the plasmids and cloning procedures, and BMH71-18 mutS (thi, supE, δ(lac-proAB), [mutS::Tn10][F`, proA+B+, lacIqZδM15]) (Clontech) was used in the mutagenesis steps. E. coli strain UM262 (recA katG::Tn10 pro leu rpsL hsdM hsdR endl lacY) (Loewen and Stauffer 1990) was used for overexpression of both wild-type and mutated KatG proteins. UM262 and pKAT II were both gifts from Stewart Cole (Institut Pasteur, Paris).

Site-directed mutagenesis of the M. tuberculosis katG gene

Mutagenesis was performed using the Transformer site-directed mutagenesis kit from Clontech. The 1.0-kb ClaI–XhoI fragment of the katG gene was subcloned into the pKS II+ vector in two steps to generate pSY15, in which mutagenesis was performed. The desired nucleotide substitutions were confirmed (Gene Link, Inc.) for all sequences, using double-stranded plasmid DNA by the Sanger method (Sanger et al. 1977). The confirmed mutated katG insert was excised from the pKS II+ vector using NheI and XhoI. This NheI–XhoI fragment containing the W321F mutation was ligated to the pKAT II vector to replace the corresponding wild-type fragment, giving the pSY25 vector. The mutagenesis primer for the W321F mutation was AGGTCGTATTCACGAACAC CCCG, and the selection primer replacing a unique ScaI restriction site with a unique BglII site was CTGTGACTGGTGAGATCT CAACCAAGTC (boldface type indicates the bases changed during mutagenesis; the underlined portion of the selection primer sequence represents the new restriction enzyme site).

Purification of M. tuberculosis catalase–peroxidases

The catalase–peroxidase enzymes [wild-type KatG and mutant KatG(W321F)] used in this study were isolated and purified from an overexpression system in E. coli UM262 carrying either the wild-type katG gene or the mutated gene in the pKATII vector. Bacteria were grown in LB media at 37°C in the presence of ampicillin at a final concentration of 100 μg/mL. Protein expression was induced by the addition of 3-β-indoleacrylic acid (40 mg/L) when cultures achieved a cell density giving an A600 of 0.9∼1. δ-Aminolevulinic acid (150 μM) was added to LB broth at the time of induction to enhance the yield of holoenzyme (Chouchane et al. 2000). Cells were harvested 16 h postinduction, and enzyme was purified according to a published procedure (Marcinkeviciene et al. 1995) except that 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) replaced TEA-HCl buffer throughout the procedure. The pure enzymes had optical purity ratios A407/A280 ≥ 0.66. SDS gel electrophoresis was carried out under denaturing (SDS-Page) and nondenaturing (Native-Page) conditions using a Pharmacia Biotech PhastGel system.

Enzyme assays

Protein concentration was determined using a heme extinction coefficient, ɛ407 nm = 100 mM−1 cm−1. Catalase and peroxidase activities were determined according to published procedures (Marcinkeviciene et al. 1995; Saint-Joanis et al. 1999) in potassium phosphate buffer at pH 7.2 and 21°C. Spectrophotometric measurements were obtained using an NT14 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Aviv Associates).

Stopped-flow optical measurements

A rapid scanning diode array stopped-flow apparatus (HiTech Scientific Model SF-61DX2) was used for kinetics experiments. Data acquisition and analyses were performed using the Kinet-Asyst software package (HiTech Scientific). All reactions were carried out in potassium phosphate buffer at pH 7.2 (except where noted otherwise) and were thermostatted at 25°C. The change in absorbance in the Soret region for the resting enzyme reacted with varying concentration of peroxides was fit to single exponential decay functions, and the rates were used to calculate second-order rate constants for Cmpd I formation. Double-mixing stopped-flow experiments were performed to follow the reaction of Cmpd I with reducing substrates including INH, ascorbate, and potassium ferrocyanide as previously reported (Chouchane et al. 2000).

Isoniazid titration

The binding of isoniazid to purified enzymes was analyzed using optical difference spectroscopy in the Soret region (Wengenack et al. 1998). The change in the difference in absorbance between 378 nm and 411 nm, plotted against free isoniazid concentration, was analyzed using the Hill equation for the wild-type enzyme, and a simple hyperbola for the mutant, which showed noncooperative binding. Data were analyzed using SigmaPlot.

EPR spectroscopy

EPR spectra (X-band) were recorded at 77 K using a Varian E-12 spectrometer. WinEPR software was used for data acquisition and analysis, as reported previously (Chouchane et al. 2000). Samples were prepared in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2). The reaction between resting enzyme and peroxide was freeze-quenched manually by mixing 40 μM KatG(W321F) with 400 μM peroxyacetic acid into the same syringe; after a 10-sec incubation, the green mixture was quickly frozen by expelling the mixture directly into an isopentane bath at −140°C. The resulting powder was packed into an EPR tube and immediately frozen in liquid N2.

Scheme 1.

Illustration of the intermediates identified or assigned based on optical or EPR spectroscopy (solid arrows) and conversions assumed to be operating but not observed (dotted arrows).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI-43582 (NIAID) to R.S.M. and The Heiser Program of The New York Community Trust to S.Y. The authors express thanks to Nicolas Carrasco for providing data on anionic ligand binding to KatG.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

KatG, catalase–peroxidase

KatG(W321F), W321F mutant of KatG

INH, isonicotinic acid hydrazide

HRP, horseradish peroxidase

CcP, cytochrome c peroxidase

tBOOH, tert-butyl hydroperoxide

CPBA, 3-chloroperoxybenzoic acid

PAA, peroxyacetic acid; Cmpd I, Compound I

Cmpd II, Compound II

EPR, electron paramagnetic resonance

TEA, triethanolamine

LB, Luria-Bertani.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/ps.09902.

References

- Chouchane, S., Lippai, I., and Magliozzo, R.S. 2000. Catalase–peroxidase (Mycobacterium tuberculosis KatG) catalysis and isoniazid activation. Biochemistry 39 9975–9983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunford, H.B. 1991. Horseradish peroxidase: Structure and kinetic properties. In Peroxidases in chemistry and biology (eds. J. Everse et al.), Vol. II, pp 1–24. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- Dunford, H.B. 1999. Model peroxidases from yeast and horseradish, cloned enzymes, and comparison to metmyoglobin. In Heme peroxidases, pp. 18–32. WILEY-VCH, New York.

- Erman, J.E., Vitello, L.B., Mauro, J.M., and Kraut, J. 1989. Detection of an oxyferryl porphyrin π-cation-radical intermediate in the reaction between hydrogen peroxide and a mutant yeast cytochrome c peroxidase. Evidence for tryptophan-191 involvement in the radical site of compound I. Biochemistry 28 7992–7995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, D.C., Grover, T.A., and Aust, S.D. 1997. Roles of efficient substrates in enhancement of peroxidase-catalyzed oxidations. Biochemistry 36 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heym, B., Alzari, P.M., Honore, N., and Cole, S.T. 1995. Missense mutations in the catalase–peroxidase gene, katG, are associated with isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 15 235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson, K., Froland, W.A., and Schultz, P.G. 1997. Overexpression, purification, and characterization of the catalase–peroxidase KatG from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 272 2834–2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen, P.C. and Stauffer, G.V. 1990. Nucleotide sequence of katG of Salmonella typhimurium LT2 and characterization of its product, hydroperoxidase I. Mol. Gen. Genet. 224 147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manca, C., Paul, S., Barry, C.E., 3rd, Freedman, V.H., and Kaplan, G. 1999. Mycobacterium tuberculosis catalase and peroxidase activities and resistance to oxidative killing in human monocytes in vitro. Infect. Immun. 67 74–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcinkeviciene, J.A., Magliozzo, R.S., and Blanchard, J.S. 1995. Purification and characterization of the Mycobacterium smegmatis catalase–peroxidase involved in isoniazid activation. J. Biol. Chem. 270 22290–22295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marttila, H.J., Soini, H., Huovinen, P., and Viljanen, M.K. 1996. katG mutations in isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates recovered from Finnish patients. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 40 2187–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marttila, H.J., Soini, H., Eerola, E., Vyshnevskaya, E., Vyshnevskiy, B.I., Otten, T.F., Vasilyef, A.V., and Viljanen, M.K. 1998. A Ser315Thr substitution in KatG is predominant in genetically heterogeneous multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates originating from the St. Petersburg area in Russia. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 42 2443–2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro, J.M., Fishel, L.A., Hazzard, J.T., Meyer, T.E., Tollin, G., Cusanovich, M.A., and Kraut, J. 1988. Tryptophan-191–phenylalanine, a proximal-side mutation in yeast cytochrome c peroxidase that strongly affects the kinetics of ferrocytochrome c oxidation. Biochemistry 27 6243–6256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musser, J.M., Kapur, V., Williams, D.L., Kreiswirth, B.N., van Soolingen, D., and van Embden, J.D. 1996. Characterization of the catalase–peroxidase gene (katG) and inhA locus in isoniazid-resistant and -susceptible strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by automated DNA sequencing: Restricted array of mutations associated with drug resistance. J. Infect. Dis. 173 196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regelsberger, G., Jakopitsch, C., Ruker, F., Krois, D., Peschek, G.A., and Obinger, C. 2000. Effect of distal cavity mutations on the formation of compound I in catalase–peroxidases. J. Biol. Chem. 275 22854–22861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robitzek, E.H. and Selikoff, I.J. 1952. Hydrazine derivative of isonicotinic acid (rimifon, marsilid) in the treatment of active progressive caseous-pneumonic tuberculosis. Am. Rev. Tuberc. 65 402–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, D.A., DeVito, J.A., Li, Z., Byer, H., and Morris, S.L. 1996. Site-directed mutagenesis of the katG gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Effects on catalase–peroxidase activities and isoniazid resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 22 583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Joanis, B., Souchon, H., Wilming, M., Johnsson, K., Alzari, P.M., and Cole, S.T. 1999. Use of site-directed mutagenesis to probe the structure, function and isoniazid activation of the catalase/peroxidase, KatG, from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem J. 338 753–760. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, B.C., Holmes-Siedle, A.G., and Stark, B.P. 1964. Appendix B. In Peroxidase: The properties and uses of a versatile enzyme and of some related catalysts (eds. B.C. Sanders et al.), pp. 217–238. Butterworths, Washington, DC.

- Sanger, F., Nicklen, S., and Coulson, A.R. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 74 5463–5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovi, S., Jurani, N., Macura, S., and Rusnak, F. 1999. Binding of 15N-labeled isoniazid to KatG and KatG(S315T): Use of two-spin [zz]-order relaxation rate for 15N–Fe distance determination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 10962–10966. [Google Scholar]

- Welinder, K.G. 1991. Bacterial catalase–peroxidases are gene duplicated members of the plant peroxidase superfamily. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1080 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wengenack, N.L., Hoard, H.M., and Rusnak, F. 1999a. Isoniazid oxidation by Mycobacterium tuberculosis KatG: A role for superoxide which correlates with isoniazid susceptibility. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 9748–9749. [Google Scholar]

- Wengenack, N.L., Jensen, M.P., Rusnak, F., and Stern, M.K. 1999b. Mycobacterium tuberculosis KatG is a peroxynitritase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 256 485–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wengenack, N.L., Todorovic, S., Yu, L., and Rusnak, F. 1998. Evidence for differential binding of isoniazid by Mycobacterium tuberculosis KatG and the isoniazid-resistant mutant KatG(S315T). Biochemistry 37 15825–15834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg, J.B., Noble, R.W., Wittenberg, B.A., Antonini, E., Brunori, M., and Wyman, J. 1967. Studies on the equilibria and kinetics of the reactions of peroxidase with ligands. II. The reaction of ferroperoxidase with oxygen. J. Biol. Chem. 242 626–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., Heym, B., Allen, B., Young, D., and Cole, S. 1992. The catalase–peroxidase gene and isoniazid resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nature 358 591–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., Garbe, T., and Young, D. 1993. Transformation with katG restores isoniazid-sensitivity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates resistant to a range of drug concentrations. Mol. Microbiol. 8 521–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]