Abstract

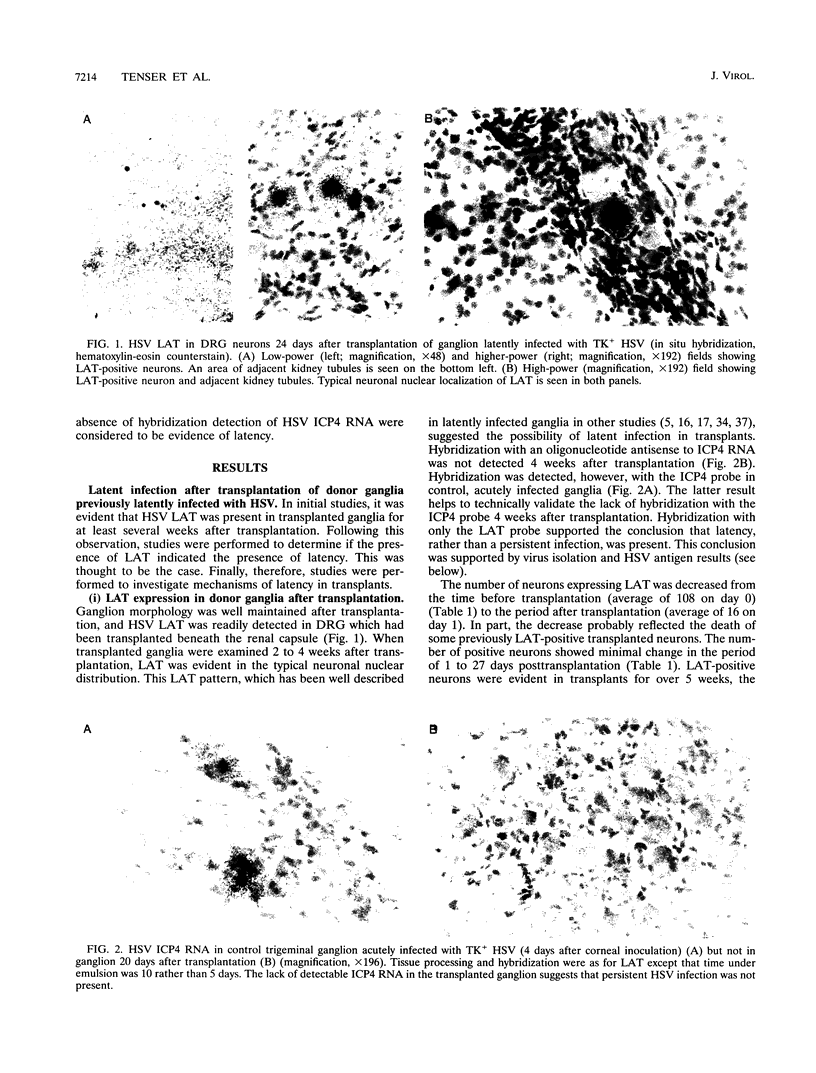

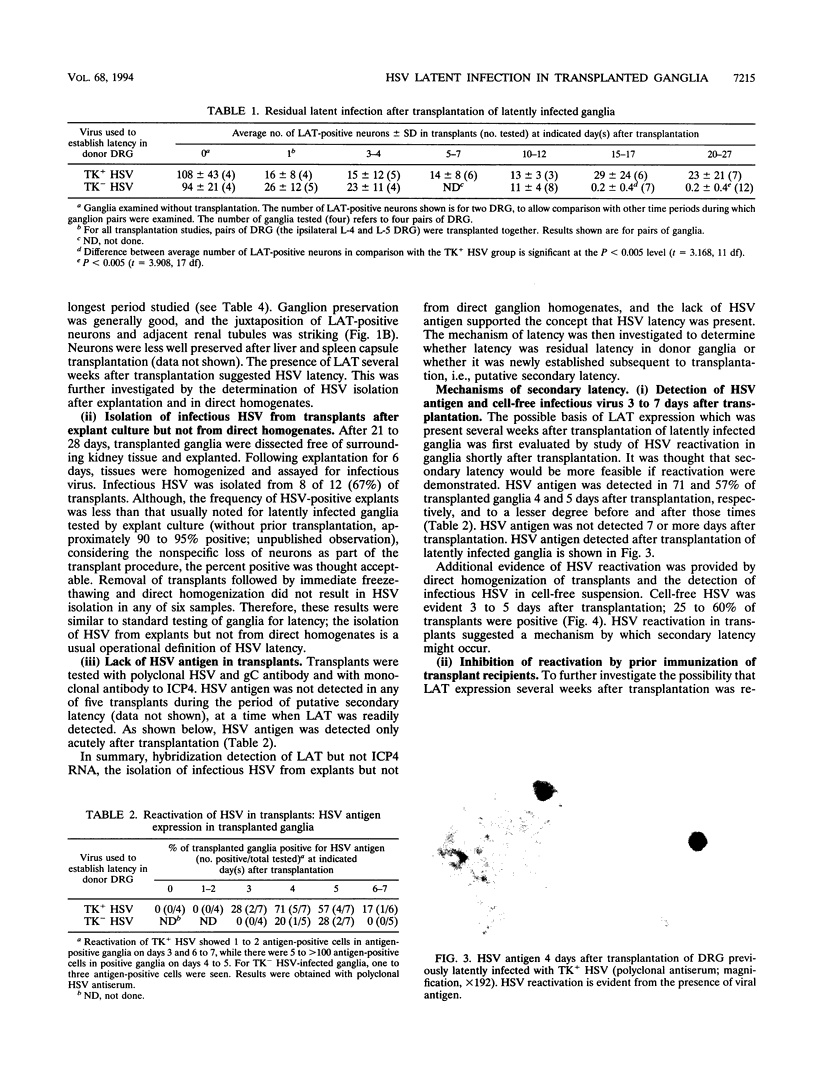

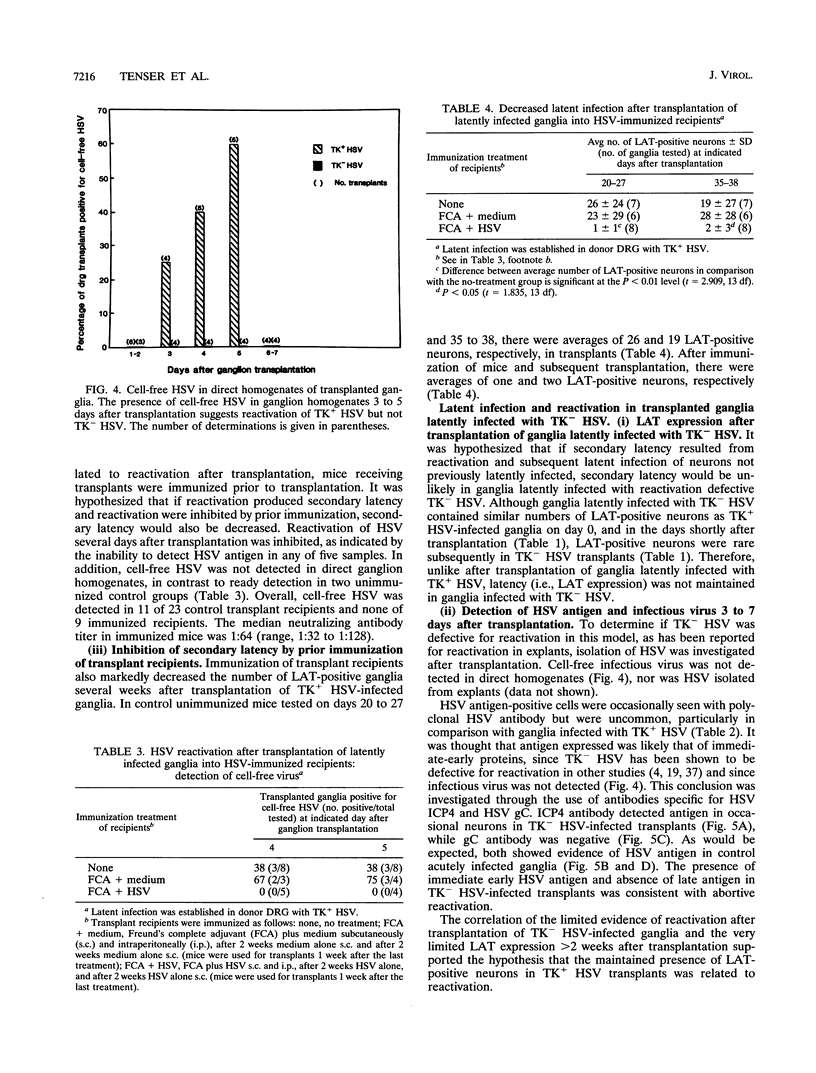

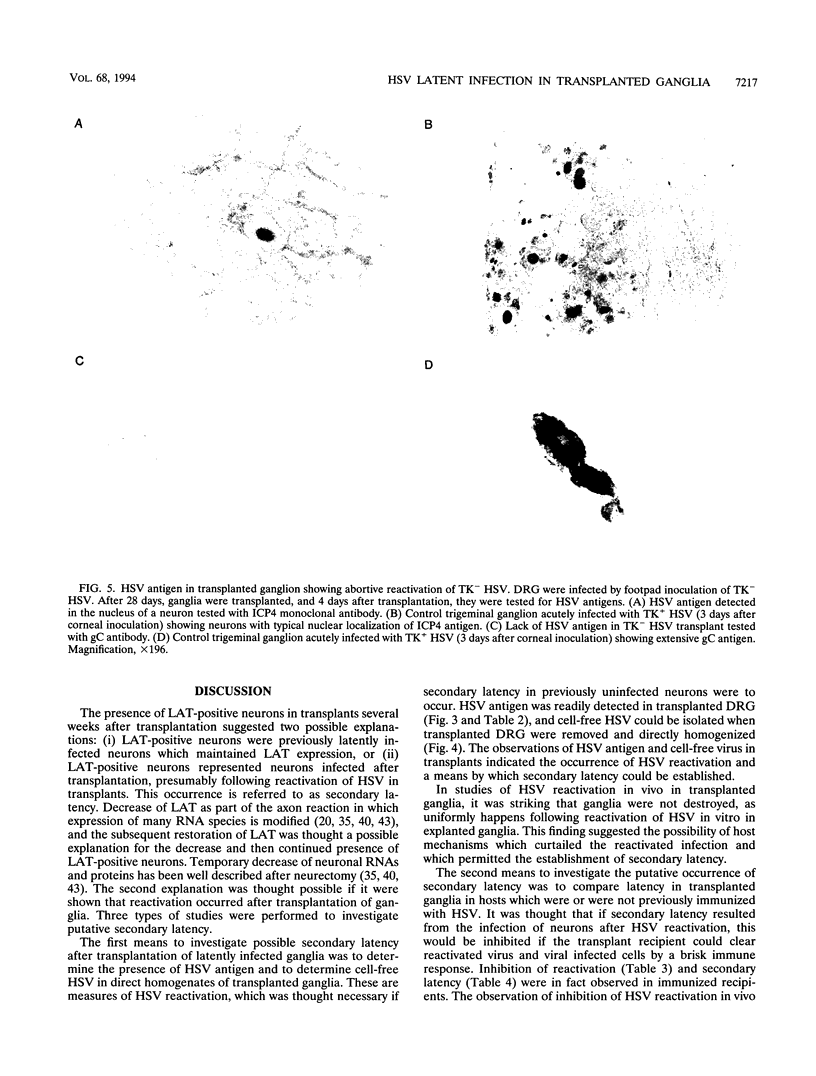

Sensory ganglia latently infected with herpes simplex virus (HSV) were transplanted beneath the renal capsule of syngeneic recipients, and the latent infection remaining was investigated. HSV latency-associated transcript (LAT) expression and reactivation of HSV after explant of transplanted dorsal root ganglia were monitored as markers of latency. Two to four weeks after transplantation, both indicated evidence of HSV latency in transplants. At those times, infectious virus was not detected in direct ganglion homogenates. In addition, viral antigen and infected cell polypeptide 4 RNA were not detected. Taken together, the results suggested that HSV latent infection rather than persistent infection was present in transplants. From these results, two explanations seemed possible: latency was maintained in transplanted neurons, or alternatively, latency developed after transplantation, in neurons not previously latently infected. The latter was considered putative secondary latency and was investigated in three ways. First, evidence of reactivation which might serve as a source for secondary latency was evaluated. Reactivation of HSV in transplants was evident from HSV antigen expression (52% of transplants) and the presence of cell-free virus (38% of transplants) 3 to 5 days after transplantation. Second, putative secondary latency was investigated in recipients immunized with HSV prior to receiving latently infected ganglia. Reactivation was not detected 3 to 5 days after transplantation in immunized recipients, and LAT expression was rare in these recipients after 3 to 4 weeks. Lastly, the possibility of secondary latency was investigated by comparing results obtained with standard HSV and with reactivation-defective thymidine kinase-negative (TK-) HSV. Defective reactivation of TK- HSV was demonstrated by immunohistochemistry and by the inability to isolate infectious virus. Donor dorsal root ganglia latently infected with TK+ HSV showed many LAT-positive neurons 2 or more weeks after transplantation (average, 26 per transplant). However, LAT expression was undetectable or minimal > 2 weeks after transplantation in donor ganglia latently infected with TK- HSV (average, 0.2 per transplant). Impaired reactivation of TK- HSV-infected donor ganglia after transplantation, therefore, was correlated with subsequent limited LAT expression. From these results, the occurrence of secondary latency was concluded for ganglia latently infected with TK+ HSV and transplanted beneath the kidney capsule. In vivo reactivation in this transplant model may provide a more useful means to investigate HSV reactivation than in usual in vitro explant models and may complement other in vivo reactivation models. The occurrence of secondary latency was unique. The inhibition of secondary latency by the immune system may provide an avenue to evaluate immunological control of HSV latency.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bloom D. C., Devi-Rao G. B., Hill J. M., Stevens J. G., Wagner E. K. Molecular analysis of herpes simplex virus type 1 during epinephrine-induced reactivation of latently infected rabbits in vivo. J Virol. 1994 Mar;68(3):1283–1292. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1283-1292.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonneau R. H., Jennings S. R. Herpes simplex virus-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes restricted to a normally low responder H-2 allele are protective in vivo. Virology. 1990 Feb;174(2):599–604. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonneau R. H., Jennings S. R. Modulation of acute and latent herpes simplex virus infection in C57BL/6 mice by adoptive transfer of immune lymphocytes with cytolytic activity. J Virol. 1989 Mar;63(3):1480–1484. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1480-1484.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen D. M., Kosz-Vnenchak M., Jacobson J. G., Leib D. A., Bogard C. L., Schaffer P. A., Tyler K. L., Knipe D. M. Thymidine kinase-negative herpes simplex virus mutants establish latency in mouse trigeminal ganglia but do not reactivate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jun;86(12):4736–4740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deatly A. M., Spivack J. G., Lavi E., O'Boyle D. R., 2nd, Fraser N. W. Latent herpes simplex virus type 1 transcripts in peripheral and central nervous system tissues of mice map to similar regions of the viral genome. J Virol. 1988 Mar;62(3):749–756. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.3.749-756.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberle R., Courtney R. J. Preparation and characterization of specific antisera to individual glycoprotein antigens comprising the major glycoprotein region of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 1980 Sep;35(3):902–917. doi: 10.1128/jvi.35.3.902-917.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efstathiou S., Kemp S., Darby G., Minson A. C. The role of herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase in pathogenesis. J Gen Virol. 1989 Apr;70(Pt 4):869–879. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-4-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield Z., Devor M. Collateral reinnervation of rat hindlimb skin does not depend on repeated sensory testing. Neurosci Lett. 1981 Sep 25;25(3):305–309. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. M., Sedarati F., Javier R. T., Wagner E. K., Stevens J. G. Herpes simplex virus latent phase transcription facilitates in vivo reactivation. Virology. 1990 Jan;174(1):117–125. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho D. Y. Herpes simplex virus latency: molecular aspects. Prog Med Virol. 1992;39:76–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson P. C., Diamond J. Temporal and spatial constraints on the collateral sprouting of low-threshold mechanosensory nerves in the skin of rats. J Comp Neurol. 1984 Jul 1;226(3):336–345. doi: 10.1002/cne.902260304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R. J. Effect of immune serum on the establishment of herpes simplex virus infection in trigeminal ganglia of hairless mice. J Gen Virol. 1980 Aug;49(2):401–405. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-2-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R. J. Initiation and maintenance of latent herpes simplex virus infections: the paradox of perpetual immobility and continuous movement. Rev Infect Dis. 1985 Jan-Feb;7(1):21–30. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosz-Vnenchak M., Coen D. M., Knipe D. M. Restricted expression of herpes simplex virus lytic genes during establishment of latent infection by thymidine kinase-negative mutant viruses. J Virol. 1990 Nov;64(11):5396–5402. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5396-5402.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosz-Vnenchak M., Jacobson J., Coen D. M., Knipe D. M. Evidence for a novel regulatory pathway for herpes simplex virus gene expression in trigeminal ganglion neurons. J Virol. 1993 Sep;67(9):5383–5393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5383-5393.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause P. R., Croen K. D., Straus S. E., Ostrove J. M. Detection and preliminary characterization of herpes simplex virus type 1 transcripts in latently infected human trigeminal ganglia. J Virol. 1988 Dec;62(12):4819–4823. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4819-4823.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leib D. A., Bogard C. L., Kosz-Vnenchak M., Hicks K. A., Coen D. M., Knipe D. M., Schaffer P. A. A deletion mutant of the latency-associated transcript of herpes simplex virus type 1 reactivates from the latent state with reduced frequency. J Virol. 1989 Jul;63(7):2893–2900. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.2893-2900.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leib D. A., Coen D. M., Bogard C. L., Hicks K. A., Yager D. R., Knipe D. M., Tyler K. L., Schaffer P. A. Immediate-early regulatory gene mutants define different stages in the establishment and reactivation of herpes simplex virus latency. J Virol. 1989 Feb;63(2):759–768. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.2.759-768.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leist T. P., Sandri-Goldin R. M., Stevens J. G. Latent infections in spinal ganglia with thymidine kinase-deficient herpes simplex virus. J Virol. 1989 Nov;63(11):4976–4978. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4976-4978.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman A. R. The axon reaction: a review of the principal features of perikaryal responses to axon injury. Int Rev Neurobiol. 1971;14:49–124. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. R., Suzuki S. Inflammatory sensory polyradiculopathy and reactivated peripheral nervous system infection in a genital herpes model. J Neurol Sci. 1987 Jun;79(1-2):155–171. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(87)90270-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeoch D. J., Dolan A., Donald S., Brauer D. H. Complete DNA sequence of the short repeat region in the genome of herpes simplex virus type 1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986 Feb 25;14(4):1727–1745. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.4.1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKendall R. R. IgG-mediated viral clearance in experimental infection with herpes simplex virus type 1: role for neutralization and Fc-dependent functions but not C' cytolysis and C5 chemotaxis. J Infect Dis. 1985 Mar;151(3):464–470. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan J. L., Darby G. Herpes simplex virus latency: the cellular location of virus in dorsal root ganglia and the fate of the infected cell following virus activation. J Gen Virol. 1980 Dec;51(Pt 2):233–243. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-2-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Openshaw H., Asher L. V., Wohlenberg C., Sekizawa T., Notkins A. L. Acute and latent infection of sensory ganglia with herpes simplex virus: immune control and virus reactivation. J Gen Virol. 1979 Jul;44(1):205–215. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-44-1-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves W. C., Corey L., Adams H. G., Vontver L. A., Holmes K. K. Risk of recurrence after first episodes of genital herpes. Relation to HSV type and antibody response. N Engl J Med. 1981 Aug 6;305(6):315–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198108063050604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock D., Lokensgard J., Lewis T., Kutish G. Characterization of dexamethasone-induced reactivation of latent bovine herpesvirus 1. J Virol. 1992 Apr;66(4):2484–2490. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2484-2490.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawtell N. M., Thompson R. L. Rapid in vivo reactivation of herpes simplex virus in latently infected murine ganglionic neurons after transient hyperthermia. J Virol. 1992 Apr;66(4):2150–2156. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2150-2156.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillitoe E. J., Wilton J. M., Lehner T. Sequential changes in cell-mediated immune responses to herpes simplex virus after recurrent herpetic infection in humans. Infect Immun. 1977 Oct;18(1):130–137. doi: 10.1128/iai.18.1.130-137.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimeld C., Hill T. J., Blyth W. A., Easty D. L. Reactivation of latent infection and induction of recurrent herpetic eye disease in mice. J Gen Virol. 1990 Feb;71(Pt 2):397–404. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-2-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner I., Spivack J. G., Deshmane S. L., Ace C. I., Preston C. M., Fraser N. W. A herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant containing a nontransinducing Vmw65 protein establishes latent infection in vivo in the absence of viral replication and reactivates efficiently from explanted trigeminal ganglia. J Virol. 1990 Apr;64(4):1630–1638. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1630-1638.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. G., Cook M. L. Maintenance of latent herpetic infection: an apparent role for anti-viral IgG. J Immunol. 1974 Dec;113(6):1685–1693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. G. Human herpesviruses: a consideration of the latent state. Microbiol Rev. 1989 Sep;53(3):318–332. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.3.318-332.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. G., Wagner E. K., Devi-Rao G. B., Cook M. L., Feldman L. T. RNA complementary to a herpesvirus alpha gene mRNA is prominent in latently infected neurons. Science. 1987 Feb 27;235(4792):1056–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.2434993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenser R. B., Edris W. A., Hay K. A. Neuronal control of herpes simplex virus latency. Virology. 1993 Aug;195(2):337–347. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenser R. B., Hay K. A., Edris W. A. Latency-associated transcript but not reactivatable virus is present in sensory ganglion neurons after inoculation of thymidine kinase-negative mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 1989 Jun;63(6):2861–2865. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2861-2865.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenser R. B., Hsiung G. D. Pathogenesis of latent herpes simplex virus infection of the trigeminal ganglion in guinea pigs: effects of age, passive immunization, and hydrocortisone. Infect Immun. 1977 Apr;16(1):69–74. doi: 10.1128/iai.16.1.69-74.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenser R. B. Sequential changes of sensory neuron (fluoride-resistant) acid phosphatase in dorsal root ganglion neurons following neurectomy and rhizotomy. Brain Res. 1985 Apr 22;332(2):386–389. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90610-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trousdale M. D., Steiner I., Spivack J. G., Deshmane S. L., Brown S. M., MacLean A. R., Subak-Sharpe J. H., Fraser N. W. In vivo and in vitro reactivation impairment of a herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript variant in a rabbit eye model. J Virol. 1991 Dec;65(12):6989–6993. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6989-6993.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar M. J., Cortés R., Theodorsson E., Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z., Schalling M., Fahrenkrug J., Emson P. C., Hökfelt T. Neuropeptide expression in rat dorsal root ganglion cells and spinal cord after peripheral nerve injury with special reference to galanin. Neuroscience. 1989;33(3):587–604. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90411-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler S. L., Nesburn A. B., Watson R., Slanina S. M., Ghiasi H. Fine mapping of the latency-related gene of herpes simplex virus type 1: alternative splicing produces distinct latency-related RNAs containing open reading frames. J Virol. 1988 Nov;62(11):4051–4058. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.11.4051-4058.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J., Oblinger M. M. NGF rescues substance P expression but not neurofilament or tubulin gene expression in axotomized sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 1991 Feb;11(2):543–552. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-02-00543.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarling J. M., Moran P. A., Brewer L., Ashley R., Corey L. Herpes simplex virus (HSV)-specific proliferative and cytotoxic T-cell responses in humans immunized with an HSV type 2 glycoprotein subunit vaccine. J Virol. 1988 Dec;62(12):4481–4485. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4481-4485.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]