Abstract

We investigated how asparagine (N)-linked glycosylation affects assembly of acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Block of N-linked glycosylation inhibited AChR assembly whereas block of glucose trimming partially blocked assembly at the late stages. Removal of each of seven glycans had a distinct effect on AChR assembly, ranging from no effect to total loss of assembly. Because the chaperone calnexin (CN) associates with N-linked glycans, we examined CN interactions with AChR subunits. CN rapidly associates with 50% or more of newly synthesized AChR subunits, but not with subunits after maturation. Block of N-linked glycosylation or trimming did not alter CN-AChR subunit associations nor did subunit mutations prevent N-linked glycosylation. Additionally, CN associations with subunits lacking N-linked glycans occurred without subunit aggregation or misfolding. Our data indicate that CN associates with AChR subunits without N-linked glycan interactions. Furthermore, CN-subunit associations only occur early in AChR assembly and have no role in events later that require N-linked glycosylation.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER)2 lumen is specialized for protein folding and assembly. Resident chaperone proteins facilitate protein folding while processing enzymes catalyze post-translational protein processing events such as the addition of asparagine (N)-linked glycans and disulfide bond formation. The role of N-linked glycans in protein folding, assembly, and function is not clearly defined. Prevention of N-linked glycosylation has varied effects among proteins and depends on many different factors (1). One function of N-linked glycosylation is to mediate associations with certain ER-resident chaperones. Whereas most ER-resident chaperone proteins bind directly to polypeptide regions of proteins, calnexin (CN) and calreticulin (CRT) can bind to N-linked glycans of proteins via its lectin binding domain. Both specifically associate with monoglucosylated Glc1Man9GlcNAc2 oligosaccharides transiently during glucose trimming of N-linked glycans in the ER (reviewed in Refs. 1–3). As a lectin, CN binds glycans to deliver proteins to other chaperones and processing enzymes. Recent studies suggest that CN is part of a larger complex that contains other components such as the thiol oxidoreductase ERp57 (reviewed in Ref. 4).

Can CN bind its substrates through an N-linked glycosylation-independent mechanism? Several studies found that CN interactions with proteins occur after enzymatic removal of glycans (5–7) and that glycosylation or glucosidase inhibitors did not completely inhibit associations with CN (8–13). Also, CN associates with proteins not N-linked glycosylated, such as the T-cell receptor ∊-subunit (14), a mutant proteolipid protein (15) or proteins mutated to eliminate consensus N-linked glycosylation sites, such as the multidrug P-glycoprotein (16). Recent results using various CN deletion or point mutations found regions of CN that can prevent aggregation of non-glycosylated proteins (17, 18). These results support a role for a lectin-independent association between CN and its substrates. However, other studies question this conclusion. Mutations of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) G protein that remove N-linked glycosylation sites associate with CN but, it was concluded that the glycan-independent associations were a result of nonspecific aggregation of mutant VSV G and CN (11). Another possible explanation for glycosylation independent CN associations is that the observed polypeptide associations are with chaperones that are part of a larger scaffold of chaperones that includes CN. Within this scaffold of chaperones, other chaperones could directly interact with the nascent protein via polypeptide associations resulting in the observed but indirect CN association.

In this study, we have examined the role of N-linked glycosylation on the folding and assembly of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs). Muscle-type AChRs are composed of four homologous subunits, α, β, γ (or ∊), and δ, which assemble into α2βγδ pentamers in the ER (19–22). Post-translational processing events, such as the formation of disulfide bonds (23) and addition of N-linked glycans (24, 25) are critical for proper AChR assembly in the ER. Coincident with these events, CN associates with AChR subunits (22, 26). To further examine the role of N-linked glycosylation and CN in AChR assembly, we used AChR subunits from Torpedo californica. Antibodies (Abs) specifically recognize and immunoprecipitate each of the four Torpedo AChR subunits unlike subunits cloned from other species. Torpedo subunits are also less prone to proteolysis after solubilization and have the added advantage that assembly is temperature-dependent, which allows assembly to be synchronized and significantly slowed compared with avian and mammalian AChRs (27). Using the Torpedo subunits, we found that treatment with castanospermine (CAS), which can disrupt interactions between CN and other glycoproteins, blocked the late stages in AChR assembly. In contrast, CN rapidly associated with newly synthesized AChR subunits but not with partially mature AChR subunits during the late stages of AChR assembly. Moreover, the interaction between CN and AChR subunits was not altered by CAS, tunicamycin (TUN) treatment, or by AChR subunits mutated to prevent the addition of N-linked glycans. Our data indicate that CN can associate with AChR subunits without interacting with N-linked glycans, and that CN has no role in subunit assembly events that require N-linked glycosylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue Culture

We used the tsA201 cell line, a human embryonic kidney cell line (28), for all transient transfections. Cells were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% calf serum. Mouse L fibroblast cells, stably transfected with Torpedo α-, β-, γ-, and δ-subunits (29) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% calf serum and 15 μg/ml hypoxanthine, 1 μg/ml aminopterin, and 5 μg/ml thymidine. 20 mm sodium butyrate was added to medium 1−5 days prior to assay to enhance AChR expression.

Construction of Glycosylation Mutants

We created glycosylation mutants of the AChR subunits to test the lectin specificity of CN for the AChR subunits. N-linked glycans are added to asparagines found in asparagine-X-serine/threonine (NX(S/T)) recognition sequences in proteins. In each of the glycosylation mutants, the S or T of the NX(S/T) consensus sequence was changed to an alanine. The γN2 and δN2 glycosylation mutants were a kind gift from Dr. K. Sumikawa (University of Irvine, Ref. 25). To create the double and triple mutants of the γ- and δ-subunits unique restriction sites between the now removed N-linked glycans were used to create the γN1N2, δN1N2, δN1N3, δN2N3, and δN1N2N3. All mutants were sequenced to ensure no errors were introduced by the PCR.

Transient Transfection

The wild-type and mutant Torpedo AChR subunit cDNAs in the pRBG4 expression vector (30), the canine CN-HA cDNA in the pREP8 vector (Invitrogen, Ref. 31) or the mouse GRP94-FLAG in the pFLAG-CMV-1 vector (Kodak) were transiently transfected into 6-cm cultures of tsA201 cells using a calcium phosphate method (32).

Metabolic Labeling, Solubilization, and Subunit Immunoprecipitations

To enhance subunit expression in the mouse L fibroblasts, stably transfected with the Torpedo subunit cDNAs (All-11 cells), cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 20 mm sodium butyrate 36 h before the experiment. Cultures in 10-cm plates were metabolically labeled as described previously (23, 27, 33). Briefly, the cultures were starved in methionine-cysteine (Met/Cys)-free DMEM for 15 min and then pulse-labeled at 37 °C in Met/Cys-free DMEM supplemented with 333 μCi of a [35S]Met [35S]Cys mixture ([35S]Met/Cys, NEN EXPE35S35S). Cells that were chased (Fig. 1, B and C) were washed two more times with the DMEM containing 5 mm Met/Cys and chased in medium. When added, 1 mm CAS was included in the sodium butyrate medium 2 h prior to labeling, as well as, during the label and chase. Cells were solubilized in lysis buffer composed of 150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris, 1 mm CaCl2, pH 7.4, 2 mm N-ethylmaleimide, and 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride plus 0.02% NaN3, 1.83 mg/ml phosphatidylcholine, and 1% Lubrol (LPC). Solubilized AChR subunits were purified using either a single immunoprecipitation (Fig. 1, D and E) or nondenaturing double immunoprecipitation protocol (Figs. 2E and 3B). The double immunoprecipitation protocol involved first immunoprecipitating cell lysates with an AChR subunit-specific monoclonal antibody (mAb). The first immunoprecipitation was then purified with protein G-Sepharose. The Sepharose beads bound to mAb-AChR subunit complexes were washed and treated with 100 mm glycine pH 2.5 to remove the subunit complexes from the Sepharose. The eluted subunit complexes were immunoprecipitated a second time with either the same subunit-specific or an N-terminal anti-CN Ab (Stressgen). The second Ab-subunit complexes were purified with protein A-Sepharose because the subunit-specific mAbs used in the first immunoprecipitations are not recognized by protein A. The final immunoprecipitations were washed three times, run on non-reducing 7.5% SDS-PAGE, fixed, treated 30 min with Amplify (Amersham Biosciences) to enhance the signal, dried, and exposed to film at —80 °C with an intensifying screen. The subunit band intensity was scanned using a Typhoon 8600 PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences) and quantified using the ImageQuant software included with the Typhoon. Autoradiographs were also quantified by scanning densitometry using a scanner and analyzed with the same ImageQuant software. To ensure that quantified bands were in the linear range and darker signals were not saturated, at least three different autoradiographic exposures were taken for each experiment.

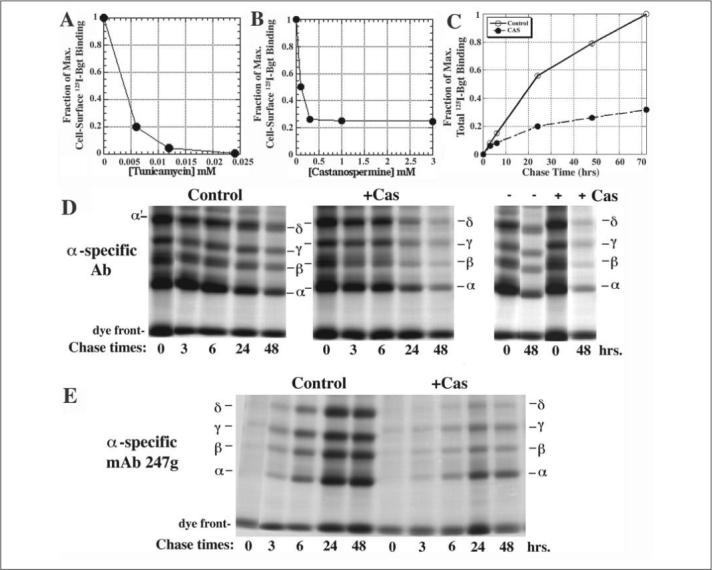

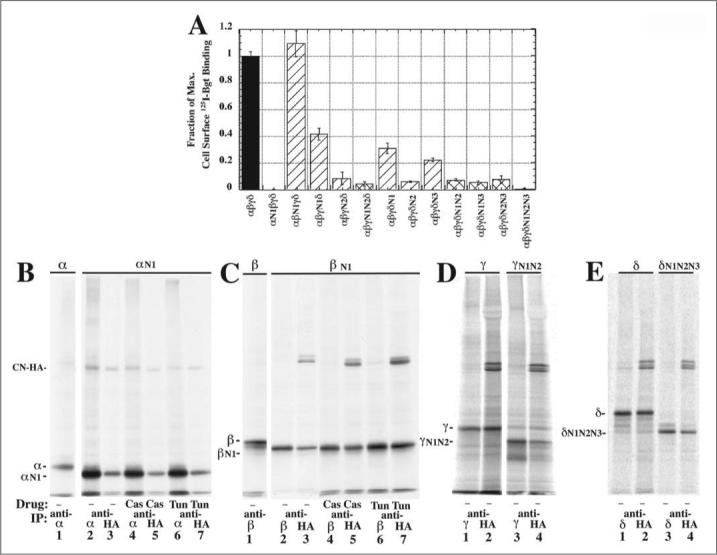

FIGURE 1. CAS and TUN block AChR subunit assembly.

A and B, effect of TUN (A) or CAS (B) cell surface 125I-Bgt binding. CAS and TUN were added 2 h prior to the temperature shift to 20 °C and cultures maintained for 48 h. Experiments were performed in duplicate in two independent experiments. C, effects of CAS on total cellular 125I-Bgt binding. CAS was added 2 h prior to the temperature shift to 20 °C and cultures maintained for the indicated times. Experiments were performed in triplicate in two independent experiments. Points are the mean ± standard deviation. D, AChR subunits were pulse-labeled for 30 min and chased for the indicated times in the absence (left) and presence (middle) of 1 mm CAS (n = 3). Subunits were immunoprecipitated with α-specific Abs. The band labeled as α' was previously shown to be different from the δ-subunit (27). E, equal aliquots of the labeled subunits from D were immunoprecipitated with conformational-dependent, α-specific mAb 247g (n = 3).

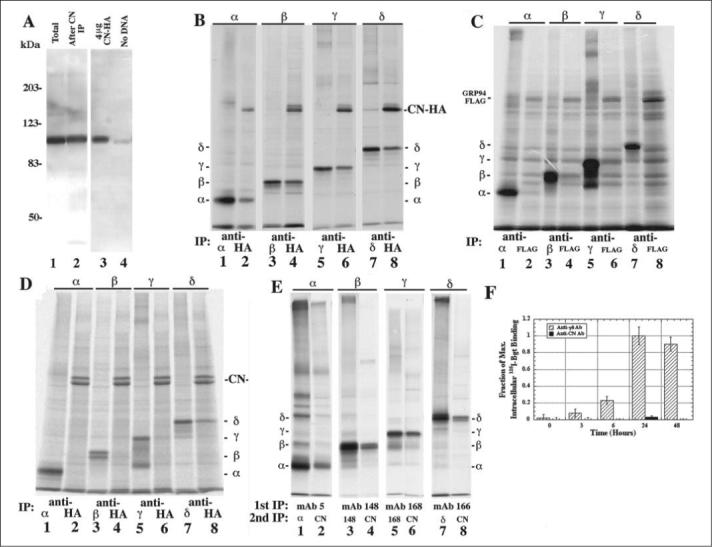

FIGURE 2. Calnexin interacts with newly synthesized AChR subunits but not with subunits later in assembly.

A, amount of CN immunodepleted by the anti-CN Ab was determined by overlaying Western blots with the anti-CN Ab. Total cell lysate from a single 10-cm plate of mouse L fibroblasts stably expressing the Torpedo subunits was trichloroacetic acid-precipitated (lane 1) and compared with total cell lysate that was immunoprecipitated with the anti-CN Ab before the trichloroacetic acid precipitation (lane 2; n = 5). The increase in CN expression was also measured by comparing sham-transfected cells (lane 4) to cells transfected with CN-HA (lane 3) by overlaying Western blots with anti-CN Ab (n = 4). B, cells transiently expressing CN-HA along with one of the four AChR subunits were [35S]Met/Cys pulse-labeled. Labeled lysates were split into two equal aliquots, immunoprecipitated with a subunit-specific Ab (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7) or an HA-specific Ab (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8), and compared with each other (see TABLE ONE; n = 5−7; ± S.E. for each subunit). C, to determine if transient overexpression leads to an increase in AChR subunit associated with a chaperone, cells transiently expressing GRP94-FLAG along with one of the four AChR subunits were [35S]Met/Cys pulse-labeled. Labeled lysates were split into two equal aliquots and immunoprecipitated with a subunit-specific Ab (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7) or a FLAG-specific mAb (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8). D, purification of nonspecific in vitro associations between CN-HA and AChR subunits. Cells transiently expressing CN-HA or one of the four AChR subunits were [35S]Met/Cys pulse-labeled. Labeled CN-HA lysates were combined with the labeled single AChR subunit lysates. These newly combined cell lysates were split into two equal aliquots and immunoprecipitated with a subunit-specific Ab (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7) or an anti-HA Ab (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8). E, cells stably expressing the Torpedo subunits were [35S]Met/Cys pulse-labeled. Labeled α-, β-, γ-, and δ-subunits were subjected to the double immunoprecipitation protocol (see “Materials and Methods”). Subunits that co-precipitate after a single immunoprecipitation were mostly lost because of the glycine treatment. F, CN does not associate with intracellular Bgt binding AChRs. Cells stably expressing the four Torpedo AChR subunits were shifted to 20 °C to begin AChR assembly. After 0, 3, 6, 24, and 48 h at 20 °C, the intracellular AChRs were isolated and bound to 10 nm 125I-Bgt along with an anti-γδ or anti-CN Ab. Fraction of maximum values shown were calculated by dividing all 125I-Bgt counts by the number of 125I-Bgt counts in the γδ subunit-specific Ab-purified vector samples (n = 3).

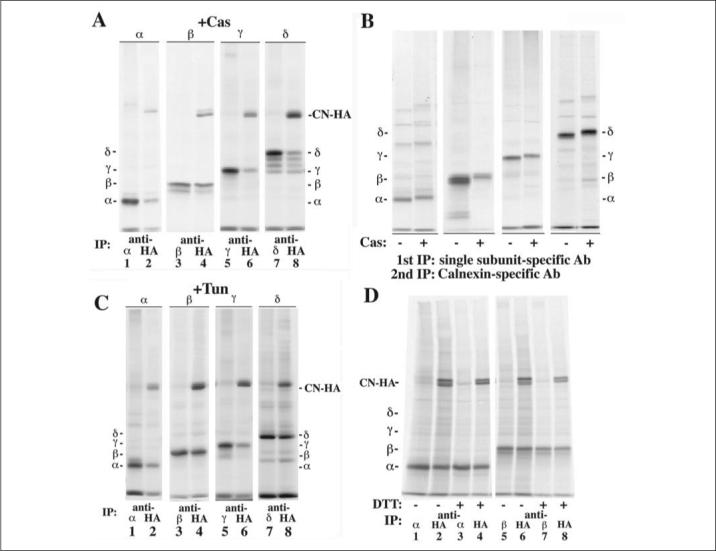

FIGURE 3. CAS, TUN, or DTT do not prevent associations between CN and AChR subunits.

A, cells transiently expressing CN-HA and each of the AChR subunits were treated with 1 mm CAS and [35S]Met/Cys pulse-labeled. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a subunit-specific (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) or a HA-specific Ab (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). The presence of CAS only slightly decreased the amount of δ associated with CN-HA as compared with Fig. 2B (TABLE ONE). B, cells stably expressing the Torpedo AChR subunits were [35S]Met/Cys pulse-labeled, and cell lysates were double immunoprecipitated as in Fig. 2E. 1 mm CAS was present in the medium in lanes labeled with Cas (+). For all four subunits, the presence of CAS had little to no effect on the associations between the subunits and CN when compared with Fig. 2E. C, cells transiently expressing CN-HA and one of the four AChR subunits were treated with 12 μm TUN and [35S]Met/Cys, pulse-labeled. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a subunit-specific Ab (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) or a HA-specific Ab (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). The presence of TUN had little to no effect on the associations between the subunits and CN-HA (TABLE ONE). D, cells transiently expressing CN-HA and either the α- or β- AChR subunit were pretreated and pulse-labeled in the absence (lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6) or presence of 5 mm DTT (lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8). Cell lysates were split in equal halves and immunoprecipitated with a subunit-specific (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) or anti-HA Ab (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). The presence of DTT had little to no effect on the associations between the subunits and CN-HA when +DTT lanes are compared with —DTT lanes.

To [35S]Met/Cys-labeled cells transiently transfected, cells were pulse-labeled for 5 min 18−24 h post-transfection as above except 111 μCi of [35S]Met/Cys was used. When 5 mm DTT was added to the cells, it was present in the medium 15 min before and during the 5-min pulse label (Fig. 3D). On the other hand, 1 mm CAS or 12 μm TUN was included in the medium 2 h prior to labeling, as well as during the label. Following the label, the cells were washed three times and solubilized in 1% LPC. 20 mm NEM was added to the LPC when solubilizing the DTT-treated cells to prevent formation of nonspecific disulfide bonds after solubilization. The cell lysates were then split into two equal aliquots and immunoprecipitated with a subunit-specific or an anti-HA-specific Ab, that quantitatively precipitates CN-HA (data not shown). The immunoprecipitations were protein G-Sepharose-purified, washed three times, run on non-reducing SDS-PAGE, and band intensities quantified as above.

Western Blots

To determine the amount of CN immunodepleted by the anti-CN Ab, a 1:100 dilution of anti-CN Ab (Stressgen) was added to LPC solubilized 10-cm plate of All-11 cells (Fig. 2A, lane 2). The Ab-CN complex was purified with protein-G-Sepharose, and the resulting supernatant was trichloroacetic acid-precipitated. Total CN was determined by not immunodepleting All-11 cells (Fig. 2A, lane 1). Equivalent amounts of trichloroacetic acid-precipitated total or immunodepleted samples were loaded in each gel lane. 6-cm plates of tsA201 either sham-transfected (Fig. 2A, lane 4) or transfected with 4 μg of CN-HA cDNA (Fig. 2A, lane 3) were trichloroacetic acid-precipitated to determine the transient increase of CN-HA expression. All samples were separated using 7.5% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose for Western blot analysis. Blots were probed with anti-CN Ab (1:2000 dilution) and were developed by chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham Biosciences). Band intensities were quantified by scanning 3−5 exposures to ensure the linearity of the band intensities using the Computing Densitometer and ImageQuant software (Amersham Biosciences).

125I-Bgt Binding

To measure cell surface 125I-α-bungarotoxin (125I-Bgt) binding of transiently transfected cells were shifted from 37 to 20 °C, 24 h after the transfection. Cultures were grown for 4 days after transfection at 20 °C for maximal surface AChR expression. In contrast, cells stably expressing αβγδ receptor subunits were grown at 37 °C for 36 h and then shifted to 20 °C for 48 h. The cultures were then washed with PBS and incubated at room temperature in PBS containing 4 nm 125I-Bgt (140−170 cpm/fmol) for 2 h, which results in saturation of binding. Cultures were washed again in PBS, and the cell surface counts determined by γ-counting. Intracellular 125I-Bgt binding was measured by preincubating the cells in excess cold Bgt prior to solubilization (Fig. 2F). Appropriate Abs along with 10 nm 125I-Bgt were added to the cell lysates, incubated at 4 °C overnight to saturate binding at this lower temperature, followed by protein G-Sepharose purification.

Sucrose Gradients

To compare the β- and βN1-subunits on the basis of their size, cell lysates, (labeled with [35S]Met/Cys) from cells transiently transfected with CN-HA alone or cotransfected with β or βN1 plus CN-HA, were layered on 5 ml of a 5−20% linear sucrose gradient prepared in the lysis buffer plus 0.1% LPC (Fig. 5). Gradients were centrifuged in a Beckman SW 50.1 rotor at 40,000 rpm for 10 h (ω2t = 1.53 × 1012). 300-μl fractions were collected from the top of the gradient (fraction 1) to the bottom (fraction 16). Under native, non-denatured conditions, proteins from each fraction were immunoprecipitated with a β-subunit-specific or anti-HA-specific Abs, precipitated by protein G-Sepharose and run on non-denaturing SDS-PAGE.

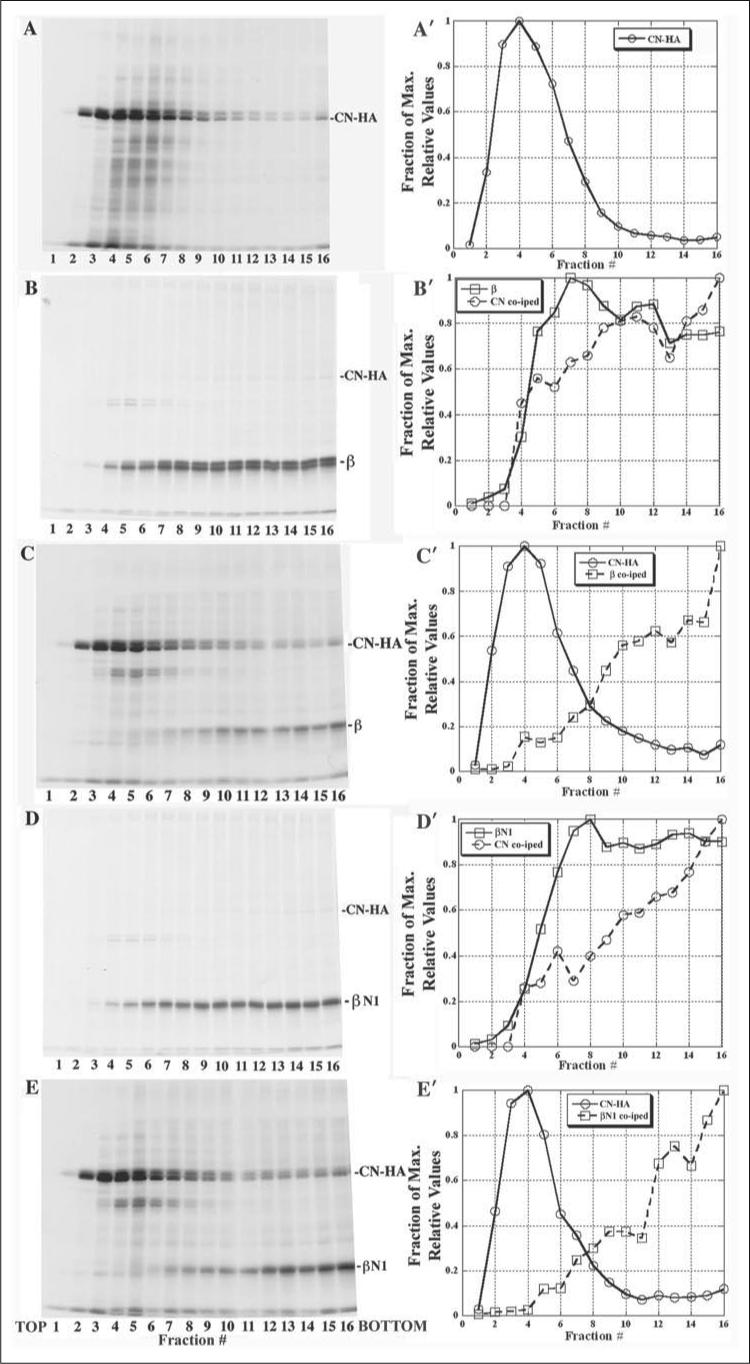

FIGURE 5. Sedimentation profiles of β- and βN1-subunits.

A–E, cells expressing CN-HA alone (A) or CN-HA with either β (B and C) or βN1 (D and E) were metabolically labeled. Cell lysates were layered onto 5−20% linear sucrose gradients and 300-μl samples collected from the top of each gradient. A'–E', CN-HA β-, and βN1-subunit band intensities were determined by densitometry for gradient fractions 1−16 and are plotted for each of the gradients (A–E). Labeled proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA Abs to precipitate CN-HA (A, C, and E) or with anti-β Abs to precipitate β- (B) or βN1- (D) subunits.

RESULTS

Loss of N-glycosylation or Its Glucose Trimming Blocks AChR Assembly

We first examined how block of N-linked glycosylation or its glucose trimming affected AChR assembly. Mouse fibroblast L cells stably expressing the four Torpedo AChR subunits were treated with TUN or CAS. Torpedo AChR subunits were used because their assembly is temperature-sensitive (29) allowing us to slow receptor assembly. Cells were treated with CAS or TUN starting 2 h before the temperature shift. CAS treatment decreased AChRs surface expression, as assayed with 125I-Bgt binding, by 75% (Fig. 1B), whereas TUN completely abolished it (Fig. 1A). In parallel, we measured 125I-Bgt binding to the total cellular pool of AChRs, which is a measure of the maturation of AChR subunits during their assembly in the ER (Fig. 1C). 48 h after the temperature shift CAS treatment caused a 74% decrease in cellular 125I-Bgt binding, similar to the CAS-induced decrease observed for cell surface 125I-Bgt binding. TUN completely abolished total cellular 125I-Bgt binding (data not shown). These data indicate that CAS and TUN treatment inhibit new AChR assembly because intracellular 125I-Bgt binding site formation occurs during AChR assembly in the ER.

The effect of CAS on AChR expression was further characterized by pulse chase experiments in the presence or absence of 1 mm CAS (Fig. 1, D and E). Immediately following the pulse label of the subunits, CAS treatment had no effect on AChR subunit band intensities in Fig. 1D. Based on densitometry of the AChR subunit bands at the zero hour time point, the ratio of band intensities (CAS-treated to control) was 1.02 for α-subunits, 0.90 for β-subunits, and 0.99 for γ-subunits. From these findings we conclude that CAS treatment had little to no effect on AChR subunit synthesis.

Subunit assembly was assayed by the amounts of β-, γ-, and δ-subunits that co-immunoprecipitated with α-subunits (Fig. 1D). Initially, subunit assembly was unaffected in CAS-treated cells. Again the band intensity ratios (CAS-treated to untreated) for the β- (0.90) and γ- (0.92) subunits that co-precipitated with α were not significantly changed. Little to no δ-subunit co-precipitated with α-subunits at the early chase times. The band that migrated at the same position as δ, labeled α' in Fig. 1C, was previously shown to be different from the δ-subunit and appears to be an α-subunit dimer (27). At the 48-h chase time, the band intensity ratios (CAS-treated to untreated) for co-precipitated β-, γ-, and δ-subunits were decreased. The ratios were reduced to 0.29 for β-subunits, 0.27 for γ-subunits, and 0.29 for δ-subunits, similar to the decreases in 125I-Bgt binding observed with CAS treatment (Fig. 1, B and C). Labeled subunits were also immunoprecipitated with mAb 247g, a mAb that only precipitates α-subunits after the formation of Bgt binding site when αβγδ tetramers assemble from αβγ trimers (Fig. 1E, Ref. 33). At the 3- and 6-h chase times in Fig. 1E, the intensity of the subunit bands in the precipitated αβγδ tetramers was reduced by 65−75% for the CAS-treated cells. Whereas CAS significantly reduced the relative amounts of the AChR subunits, CAS exposure did not alter the ratio of α:β:γ:δ at the 3- and 6-h chase times in Fig. 1E when mAb 247g precipitates αβγδ tetramers or at the 48-h chase time when mAb 247g precipitates α2βγδ pentamers (33). Whether or not CAS was present, we found a subunit ratio of 1:1:1:1 at the 3- and 6-h chase times and 2:1:1:1 at the 48-h chase time. Based on the results of Fig. 1, we conclude that CAS does not affect the early steps in AChR assembly when nascent subunits assemble into αβγ trimers. Instead, CAS is altering a later step in assembly after Bgt binding sites form and as αβγδ tetramers assemble.

The effect of the CAS on the migration of the AChR subunits on SDS-PAGE is shown in the far right panel of Fig. 1D. In the presence of CAS, the change in subunit migration that occurs during assembly is totally blocked. This finding suggests that the change in migration is a measure of the glucose removal during trimming of subunit N-linked glycans.

AChR Subunits Associate with CN

Because the chaperone CN behaves as a lectin, we tested whether CN is involved in the effects of TUN and CAS on AChR assembly. Previous studies found that CN binds AChR subunits (22, 26), but it was not established what fraction of the subunits associate and when the association occurs during assembly. To examine interactions between CN and AChR subunits, we expressed HA epitope-tagged CN (CN-HA; Ref. 31) with each AChR subunit individually. Transient transfection of CN-HA in the human embryonic kidney (HEK) cell line, tsA201, resulted in a ∼5-fold increase in the amount of CN expressed (Fig. 2A, compare lane 3 (CN-HA) to 4 (sham)). To test if each AChR subunit associated with CN-HA, cells transiently expressing single subunits and CN-HA were [35S]Met/Cys pulse-labeled for 5 min at 37 °C. Equal aliquots of labeled cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an HA-specific Ab (Fig. 2B, lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) and compared with the total amount of subunit immunoprecipitated with a subunit-specific Ab (Fig. 2B, lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7). Large amounts of each AChR subunit co-precipitated with CN-HA after 5 min of labeling, indicating that CN rapidly associates with AChR subunits, perhaps co-translationally. Similar results were obtained when the labeled subunits were chased up to 3 h after labeling or when the temperature was lowered to 20 °C (data not shown). When we quantified and compared the subunit band intensities, we observed that 52 ± 4% of α-, 56 ± 1% of β-, 60 ± 5% of γ- and 82 ± 4% of δ-subunits associate with the CN-HA (TABLE ONE). Taking into account ∼80% of the expressed CN is CN-HA and assuming a 1:1 stoichiometry between CN and AChR subunits, the percentage of the subunits associating with CN when endogenous CN is included is 62% of α-, 63% of β-, 72% of γ-, and 98% of δ-subunits.

TABLE ONE. Percentages of AChR subunit associated with CN-HA.

Values were estimated from quantified bands as in Fig. 2B for control, Fig. 3A for CAS and Fig. 3C for TUN. Values represent the amount of subunit that co-immunoprecipitated with CN-HA divided by the amount of subunit immunoprecipitated by the subunit-specific Ab. All values are shown as mean ± S.E. (n = 5−7).

| Subunit | Control | CAS | TUN |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |

| α | 52 ± 4 | 49 ± 3 | 48 ± 6 |

| β | 56 ± 1 | 61 ± 4 | 58 ± 8 |

| γ | 60 ± 5 | 62 ± 7 | 60 ± 6 |

| δ | 82 ± 4 | 69 ± 8a | 77 ± 6 |

Not significantly different from control based on Student's t test; p = 0.07.

We also designed experiments to test the specificity of CN-AChR subunits interactions. To test whether the HA tag contributes to CN-subunit interactions, we constructed a FLAG-tagged CN (CN-FLAG) and found that AChR subunits co-precipitated just as well with the CN-FLAG as CN-HA (data not shown). Using a different ER-resident chaperone, GRP94, tagged with the FLAG epitope (GRP94-FLAG), we observed no AChR subunits co-precipitating with GRP94-FLAG (Fig. 2C) indicating that AChR subunits specifically associate with ER chaperones in our system. We also tested the possibility that interactions could occur after solubilization of the cells by transiently expressing one of the four AChR subunits or CN-HA alone into separate cell cultures, [35S]Met/Cys pulse-labeled the cells and then solubilized (Fig. 2D). The cell lysates containing either a single-labeled AChR subunits or CN-HA were combined, and immunoprecipitations were performed as in Fig. 2B. We observed no co-precipitation of the α-, β-, or γ-subunits with CN-HA. However, ∼25% of the δ-subunit co-precipitated with CN-HA compared with the 82% of δ-subunits with CN-HA when they were transfected together (Fig. 2D). These results indicate that CN-HA and α-, β-, γ-, and δ-subunits associate predominantly in vivo. CN-HA and δ-subunits can associate in vitro, which may explain why a higher percentage of the δ-subunit associated with CN than the other three subunits.

We next tested whether CN-AChR interactions were different in cells stably expressing all four Torpedo AChR subunits. CN-specific Abs were used to immunoprecipitate the CN because only endogenous CN was expressed in these cells. Using this Ab, we were unable to clearly resolve co-precipitated AChR subunits because of the other proteins that precipitated with CN. To improve the resolution, we performed an immunoprecipitation using AChR subunit-specific Abs followed by a second immunoprecipitation with the CN-specific Ab (Fig. 2E, lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) or subunit-specific Abs (Fig. 2E, lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7). We found that ∼10−20% of the AChR subunits associated with CN. One reason for the small amount of AChR subunits co-precipitating with the endogenous CN is that the CN-specific Ab is not quantitative (e.g. Refs. 22 and 34). This problem is illustrated in Fig. 2A. The CN-specific Ab recognizes endogenous CN from cells stably expressing the four Torpedo AChR subunits (Fig. 2A, lane 1). However, if CN was first immunodepleted from an equal aliquot of the same cell lysate using a saturating amount of the CN-specific Ab, 82 ± 2% of the CN remained after the precipitation (Fig. 2A, lane 2). Thus, the Ab only precipitated ∼20% of the CN from the lysate. Taking into account that the anti-CN Ab immunoprecipitates ∼20% of the total CN (Fig. 2A), we estimate that 50−100% of each subunit associates with CN consistent with the results using transient expression of each of the subunits.

To address whether CN associates with subunits in the late stages of AChR assembly, we tested whether CN-specific Abs associated with assembling subunits after formation of Bgt binding sites. We separated intracellular Bgt binding sites from surface AChRs and performed 125I-Bgt binding to intracellular sites. Intracellular 125I-Bgt binding increased in a time dependent manner and saturated 24 h after the temperature shift (Fig. 2F). However, CN-specific Abs precipitated no 125I-Bgt binding sites at any time after the temperature shift (Fig. 2F). Any CN associations with AChR subunits are thus lost before Bgt binding site formation during AChR assembly.

CAS and TUN Do Not Affect CN-AChR Subunit Interactions

To test whether CAS or TUN altered interactions between CN and AChR subunits, cells expressing each subunit were treated with CAS and assayed as in Fig. 2B. CAS had no effect on the percentage of AChR subunits associating with CN with the possible exception of the δ-subunit (TABLE ONE). The four different δ-subunit bands (Fig. 3A, lanes 7 and 8) correspond to different states of N-linked glycosylation. The δ-subunit has three consensus sites for N-linked glycosylation and each of the bands represents the addition of 0 to 3 N-linked glycans. All of the δ-subunit glycosylation intermediates, including the non-glycosylated form, co-precipitated with CN-HA (Fig. 3A). Likewise, associations between CN and subunits from the cells stably expressing all of the subunits persisted in the presence of CAS (Fig. 3B). Our results with CN are at odds with other reports that found CAS significantly reduced the association of the α-subunit with CN (35). To block N-linked glycosylation of the AChR subunits using TUN, cells co-expressing each AChR subunit with CN-HA were [35S]Met/Cys pulse-labeled in the presence of TUN. TUN did not affect the percentage of subunit associating with CN-HA when compared with amounts in the untreated cells (Fig. 3C and TABLE ONE). Based on these results, we conclude that the trimming or addition of subunit glycans is not necessary for subunit interactions with CN.

DTT Does Not Affect CN-AChR Subunit Interactions

The crystal structure of the CN luminal domain (36) revealed two distinct subdomains: 1) a lectin binding domain at the N terminus and 2) a long arm, proline-rich, hairpin fold (P domain) that appears to interact with other proteins such as ERp57 (37). The ability of CN to bind to the protein N-linked glycan is lost with DTT treatment (38), likely via reduction of a disulfide bond within the lectin-binding domain (36). To test whether DTT exposure affects associations between CN and the subunits, cells transiently expressing each AChR subunit along with CN-HA were treated with 5 mm DTT. We have previously demonstrated that exposure to DTT prevents the formation of cystine loop disulfide bond that is essential for proper AChR subunit assembly (23). After labeling of the subunits, cells were solubilized in excess NEM to ensure no free sulfhydryls formed random disulfide bonds subsequent to solubilization. Although, the treatment of cells with DTT caused a small decrease in the labeling of the subunits, the overall percentage of α- or β-subunits associating with CN was unchanged (Fig. 3D; compare control lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6 to DTT, lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8). Thus, DTT treatment had little effect on interactions between CN and AChR subunits consistent with a model where AChR subunit-CN interaction occurs independent of the lectin binding motif.

AChR Subunit N-linked Glycosylation Mutations

To further examine whether CN binds AChR subunit N-linked glycans, we generated a series of AChR subunit mutations in which one or more of the subunit consensus sites for N-linked glycosylation were removed. Each subunit is N-linked glycosylated on 1−3 consensus sites. The α- and β-subunits have a single glycosylation site in a homologous position in the subunits (N1). γ- and δ-subunits have a second homologous glycosylation site (N2), and the δ-subunit has a third site (N3). To remove a glycosylation site, the serine/threonine in the consensus glycosylation site was changed to an alanine. A total of 12 mutated subunits were generated: 1) αN1, 2) βN1, 3) γN1, 4) γN2, 5) γN1N2, 6) δN1, 7) δN2, 8) δN3, 9) δN1N2, 10) δN1N3, 11) δN2N3, and 12) δN1N2N3. We expressed each mutated subunit with the other three wild-type subunits and assayed AChR cell surface expression using 125I-Bgt binding (Fig. 4A). With the exception of the β-subunit mutation, removal of one or more glycosylation sites on individual subunits caused a large decrease in surface AChR expression. In particular, the α, γ, and δ mutations in which all sites were removed resulted in total inhibition of surface expression consistent with the effect of TUN on AChR expression (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 4. Calnexin associates with non-glycosylated α-,γ-, and δ-subunit mutants.

A, cells were transiently transfected with all four wild-type subunits or one of the glycosylation mutants plus the other three wild-type subunits. As assayed by 125I-Bgt surface binding, cells transfected with αN1, γN1N2, or δN1N2N3 plus the other three wild-type subunits failed to express any surface Bgt binding AChRs. B–E, to test if subunit mutants lacking all consensus glycosylation sites can associate with CN, mutants were transiently coexpressed with CN-HA and [35S]Met/Cys pulse-labeled. Labeled lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-subunit Ab (lanes 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14) or an anti-HA Ab. Shown for comparison is the slower mobility of wild-type subunit (B–E, lane 1) compared with αN1, βN1 (B and C, lanes 2–7), γN1N2, or δN1N2N3 (D and E, lanes 3 and 4).

To test if CN interacts with the subunits lacking N-linked glycosylation sites, mutated subunits were transiently expressed with CN-HA and assayed for CN-subunit associations. Results are displayed in Fig. 4, B, C, D, and E for the expression of CH-HA with αN1, βN1, γN1N2, and δN1N2N3, respectively. Each mutated subunit associated with CN-HA at approximately the same levels as the wild-type subunits. Mutated subunits migrated faster on SDS-PAGE than the corresponding wild-type subunit confirming the loss of subunit glycosylation. For the αN1 (Fig. 4B) and βN1 (Fig. 4C), the mutated subunits treated with either CAS or TUN, did not alter their migration or their association with CN-HA.

One possible explanation for these results is that loss of N-linked glycosylation causes aggregation and nonspecific association with CN (11). Because α, γ, and δ subunits lacking N-linked glycosylation sites failed to properly assemble with the other wild-type subunits, it is possible that these mutated subunits do not properly fold and the associations with CN that are observed in Fig. 4, B, D, and E result from subunit aggregation. In contrast, there was no reduction in AChR assembly and surface Bgt binding expression when we substituted βN1-subunits for wild-type β-subunits (Fig. 4A), and it appears that the βN1-subunits fold and assemble correctly.

To rule out that the association between βN1 and CN is a result of nonspecific associations, we performed experiments to test whether βN1-subunits are aggregating. First, we found that virtually all βN1, as well as wild-type β-subunits were detergent solubilized by Triton X-100 (data not shown).

We also compared the sedimentation profiles of β- and βN1-subunits with or without CN-HA expression. The experiments were performed under non-denaturing and non-reducing conditions that allowed for coimmunoprecipitation of associated proteins. The sedimentation profile of CN-HA expressed in the absence of AChR subunits was determined to see if its sedimentation profile changed when expressed with AChR subunits (Fig. 5A). Cells transiently expressing β- or βN1-subunit and/or CN-HA were metabolically labeled, lysed, and layered onto a 5−20% linear sucrose gradient. CN-HA (Fig. 5, A, C, and E), β-subunits (Fig. 5B) or βN1-subunits (Fig. 5E) were immunoprecipitated from the collected gradient fractions. Uncomplexed CN sedimented at the top of the gradient in fractions 2−3, whereas in fractions 4−6, CN appears to be interacting with a large number of unidentified proteins as evidenced by the “smears” in those lanes above and below where CN migrates (Fig. 5A). Band intensities were determined for CN and the β- and βN1-subunits at the different gradient fractions (Fig. 5, A'–E') to determine the sedimentation profiles across the gradients. Little of the metabolically labeled CN co-precipitated with β- and βN1-subunits. This is because CN is extremely metabolically stabile compared with the AChR subunits. The half-life of CN is greater than 24 h (34) compared with a half-life of 30−60 min at 37 °C for Torpedo AChR subunits (39). Because of its stability, the CN protein is not metabolically labeled well and is not easily observed when co-immunoprecipitated with other proteins. With longer gel exposure times, we observed a significant amount of labeled CN that co-precipitated with β- or βN1-subunits, and the sedimentation profiles of the CN that co-precipitated with β- or βN1-subunits was determined (Fig. 5, B' and D').

Importantly, the sedimentation profiles of β- and βN1-subunits were similar to each other (Fig. 5, B and D). The subunits migrated broadly across the gradients, as previously observed for unassembled AChR subunits (40), appearing in fractions 3−4 where subunit monomers are expected to migrate and continuing to the bottom fractions. The migration of the subunits is consistent with the formation of heterogeneous homo-oligomers of the subunits and/or associations with chaperone proteins such as CN (see also Ref. 40). Because of the observed similarity in sedimentation of β- and βN1-subunits, we conclude that the associations with CN are not caused by nonspecific aggregation but result from normal productive associations that occur between CN and the AChR subunits.

A significant change in sedimentation profiles was observed with the β- or βN1-subunits that co-precipitated with CN or with the CN that co-precipitated with the subunits. In both cases, there was a shift toward the bottom of the gradient indicating the assembly of oligomeric complexes containing both CN and β- or βN1-subunits. The co-precipitated proteins were broadly distributed over fractions 7−16 suggesting that size of the CN-subunit complexes were heterogeneous.

DISCUSSION

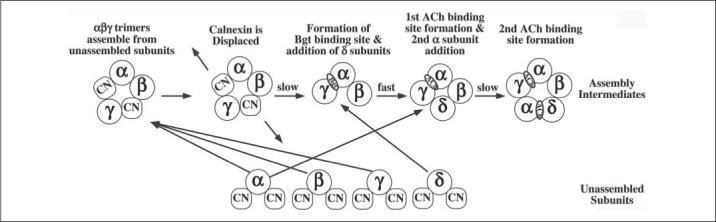

In this study, we found that the AChR subunit N-linked glycosylation strongly impacts whether AChRs fully assemble, but has little to no affect on whether AChR subunits associate with CN. N-Linked glycosylation of AChR subunits was altered using the glycosylation inhibitors, CAS or TUN, or by mutations removing the subunit glycosylation consensus sites for N-linked glycosylation. As observed previously (25, 41, 42), these changes in subunit glycosylation blocked AChR surface expression to varying degrees. We determined that the block of surface expression resulted from inhibition of AChR assembly in the ER (Fig. 1). Treatment with TUN blocked core glycosylation of all AChR subunits. Because attachment of core N-linked glycans to AChR subunits occurs co-translationally in the ER (43), glycosylation precedes or occurs during the very first steps of AChR assembly. Treatment with CAS blocked glucose trimming of subunit glycans. From the change in subunit migration on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1D), subunit glycan trimming appears to occur during later steps of AChR assembly, mostly after the formation of Bgt binding sites. Mutation of each N-linked glycosylation site on all four subunits had variable effects on AChR expression. As observed previously (25, 41), AChR expression is totally lost when α-subunits are not glycosylated (Fig. 4A). Mutation of the homologous glycosylation sites on γ- and δ-subunits caused a partial reduction in AChR expression while AChR expression was unaffected by mutation of the β-subunit site. Mutation of all glycosylation sites on the γ- and δ-subunits blocked virtually all AChR expression. The glycosylation site mutations, like TUN and CAS treatment, appeared to alter AChR assembly in the ER because formation of intracellular Bgt binding sites was also blocked. Altogether, our results indicate that N-linked glycosylation of many, but not all, of the glycosylation sites are critical for proper folding of AChR subunits. When certain sites are not glycosylated or glycans are not trimmed, subunits are likely identified as misfolded by ER quality control mechanisms and the subunits degraded by proteasomes (44).

CN behaves as a lectin in that it recognizes its substrates in the ER by a direct interaction with N-linked glycans. The dependence of AChR assembly on N-linked glycosylation suggested that CN might play a role in AChR assembly. Previous studies had already determined that α-, β-, and δ-subunits associate with CN (22, 26). We have confirmed these observations and also have shown that the fourth subunit, γ, associates with CN. Using pulse-chase analysis, we found that the associations between CN and AChR subunits occur rapidly (within 5 min) following subunit synthesis. The results are consistent with the CN associations occurring, at least in part, cotranslationally, as observed previously with other nascent polypeptides (45, 46). We determined that a large percentage of the newly synthesized AChR subunits (50−100%) associated with CN when each of the subunits was expressed individually. It is possible that CN only associates with unassembled AChR subunits as previously suggested (22). If this were the case, we would expect lower levels of CN-subunit interactions under conditions where the subunits are undergoing efficient assembly in cells expressing all four subunits. This was not observed. We obtained similar levels of CN-AChR subunit co-precipitations when AChR assembly was occurring (Fig. 2E) suggesting that CN associates with individual as well as assembled subunits. However, any CN associations with assembled subunits only occur during the early stages of AChR assembly because we were unable to precipitate any Bgt-binding complexes with CN-specific Abs (Fig. 2F). While a large percentage of AChR subunits associates with CN, the association continues only through the early stages of assembly and is lost by the time Bgt binding sites form on subunit complexes.

Surprisingly, we found that associations between CN and AChR subunits occur even after treatment with TUN (Fig. 3C), CAS (Fig. 3, A and B), or DTT (Fig. 3D), agents that normally disrupt CN associations with glycoproteins. One group (47) also found that an association between the α-subunit and CN with CAS exposure was present while another group (35) found that CAS disrupted 80% of the α-subunit-CN associations. To further examine this issue, we prevented N-linked glycosylation by mutating each subunit consensus site. We observed no significant reduction in the co-precipitation of CN with the mutated subunits (Fig. 4), thus providing further evidence for interactions between CN and AChR subunits independent of subunit glycosylation. From these results, we conclude that N-linked glycosylation is not required for AChR subunits to associate with CN and that the associations appear to occur through peptide-peptide interactions.

Previously it was reported that associations between untrimmed or non-glycosylated proteins and CN result from nonspecific disulfide bonding and/or aggregation (11). We performed experiments to test this possibility. First, under non-reducing conditions, we found no evidence of disulfide bonds linking CN with AChR subunits. Second, aggregation of mutated β-subunits lacking N-linked glycans was tested directly using sucrose gradient centrifugation. The β-subunit mutation was chosen because it, in contrast to the other three subunits, assembled into AChRs just as well as wild-type β-subunits (Fig. 4A), indicating that the mutated subunits are not misfolded. The migration of mutated β-subunits on sucrose gradients was indistinguishable from that of the wild-type β-subunits. Both wild-type and mutated β-subunits co-sedimented with CN on the gradients consistent with heteroligomeric complexes as opposed to aggregates. We cannot exclude the possibility that the association between CN and the AChR subunits is indirect, perhaps occurring through associations between the subunits and the protein-disulfide isomerase (PDI), ERp57, which can form a complex with CN (17, 48). Contrary to this possibility, we found that CN-subunit associations occur with similar efficiency whether CN and the subunits were expressed at high levels in HEK cells or much lower levels in mouse cells stably expressing all four Torpedo subunits conditions where the ratio of CN to ERp57 would be expected to be quite different (Fig. 2, B and E). Furthermore, others have reported in vitro associations between CN or CRT and non-glycosylated proteins in the absence of ERp57 (49–52).

Inhibiting the trimming of glycan terminal glucoses with CAS arrested assembly at a point during or after Bgt binding sites form on αβγ trimers (Fig. 1E). We have shown previously that at this point the α-subunit cystine loop between disulfide-bonded cysteines 128/142 rearranges making it inaccessible to a mAb that specifically recognizes the cystine loop (23). The α-subunit asparagine that is glycosylated at residue 141 is within the cystine loop that changes conformation. The results suggest that trimming of the glycan affects the efficiency of the folding events involving the α-subunit cystine loop. Treatment with CAS prevents the formation ERp57-glycoprotein mixed disulfides (53). Although CAS does not prevent AChR subunit associations with CN, it is possible that CAS prevents ERp57 function. The lower levels of AChR expression we observe in the presence of CAS are possibly the result of the other ER protein-disulfide isomerase, PDI, compensating for ERp57 inactivity. Indeed, Molinari and Helenius (53) found that in the presence of CAS ∼20% of the viral glycoproteins still folded correctly. They speculate that other ER chaperones normally not involved, such as PDI, are able to assist in the disulfide bond formation. An observation that supports this idea is the finding that PDI activity is decreased in the presence of CN or CRT (54).

Altogether, our data suggest separate roles for CN and N-linked glycosylation in the assembly of the AChR. Our results indicate that the absence of subunit glycosylation does not significantly affect CN-subunit associations. Furthermore, the trimming of the subunit glycans blocked by CAS occurs during AChR assembly at a point when CN is no longer associated with AChR subunits. Shown in Fig. 6 is a model of AChR assembly in the ER based on results from this study and previous findings about AChR assembly. An alternative model, the heterodimer model (55–57) could also be used to model the assembly of the AChR. In the proposed model, regions on AChR subunits require interactions with other subunits or chaperone proteins to prevent misfolding and ER-associated degradation. Without these interactions subunits are rapidly degraded by ER-associated degradation. CN is also shown in the model as binding to subunits as they assemble. The need for CN binding early in assembly may be caused by geometric constraints on subunit-subunit interactions that prevent full coverage of the labile regions unless they are part of the proper tetramer or pentamer. Because no Bgt binding complexes are immunoprecipitated with CN-specific Abs (Fig. 2F), CN would have to be displaced from assembling subunits before Bgt binding sites form on αβγ trimers as shown. We have found that a rate-limiting step in AChR assembly is the formation of Bgt binding sites on αβγ trimers. Bgt binding αβγ trimers are short-lived intermediates that rapidly assemble into αβγδ tetramers, which in turn allow formation of the ACh binding site on αβγδ tetramers (33). In Fig. 6, we speculate that this step is slowed by the need to shed CN from the αβγ trimer. The other rate-limiting step in AChR assembly appears to be the addition of unassembled α-subunits to αβγδ tetramers (33). As shown in the model, displacement of CN from the unassembled α-subunits occurs during this step. The tight association between CN and AChR subunits, which stabilizes the subunits, also appears to slow the assembly process when CN is displaced to initiate subsequent assembly events.

FIGURE 6. Potential role for CN during AChR assembly.

In this study, we find that CN binds to newly synthesized AChR subunits. Newly synthesized AChR subunits either rapidly assemble into αβγ trimers or remain unassembled (27). In the model, unassembled subunits are rapidly degraded via proteasomes (44) or stabilized to facilitate their assembly. We suggest that CN has two distinct functions in AChR assembly. First, associations with CN stabilize unassembled subunits and facilitate their assembly into αβγ trimers and the later additions of unassembled subunits. Second, the slow dissociation of CN controls the rate of AChR folding and oligomerization. Specifically, the rate-limiting steps, formation of Bgt-binding sites on αβγ trimers, and addition of the second α-subunits, coincide with the dissociation of CN from αβγ trimers and unassembled α-subunits.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. I. Wada for the generous gift of the CN-HA construct, B. Simen for the GRP94-FLAG construct, and Dr. K. Sumikawa for the γN2 and δN2 mutants. We would also like to thank Drs. Jon Lindstrom for the subunit-specific mAbs 5 (α), 148 (β), 166 (δ), and 168 (γ) and Toni Claudio for AChR Abs that were critical to the completion of this study. Dr. Gopal Thinakaran's critical reading of the study was also greatly appreciated.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health training grant (to C. P. W.) and by grants from NIDA and NINDS, National Institutes of Health and the Alzheimer's Association (to W. N. G.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The abbreviations used are: ER, endoplasmic reticulum; AChR, acetylcholine receptor; Ab, antibody; Bgt, bungarotoxin; CN, calnexin; CRT, calreticulin; CAS, castanospermine; DTT, dithiothreitol; HA, hemagglutinin; HEK, human embryonic kidney; LPC, lubrol phosphatidylcholine; mAb, monoclonal Ab; PDI, protein-disulfide isomerase; TUN, tunicamycin; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium.

REFERENCES

- 1.Helenius A, Aebi M. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004;73:1019–1049. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parodi AJ. Biochem. J. 2000;348:1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleizen B, Braakman I. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellgaard L, Frickel EM. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2003;39:223–247. doi: 10.1385/CBB:39:3:223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ware FE, Vassilakos A, Peterson PA, Jackson MR, Lehrman MA, Williams DB. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:4697–4704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams DB. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1995;73:123–132. doi: 10.1139/o95-015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danilczyk UG, Williams DB. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:25532–25540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carreno BM, Schreiber KL, McKean DJ, Stroynowski I, Hansen TH. J. Immunol. 1995;154:5173–5180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arunachalam B, Cresswell P. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:2784–2790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Q, Tector M, Salter RD. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:3944–3948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.3944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cannon KS, Hebert DN, Helenius A. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:14280–14284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Leeuwen JE, Kearse KP. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:9660–9665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jannatipour M, Callejo M, Parodi AJ, Armstrong J, Rokeach LA. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17253–17261. doi: 10.1021/bi981785c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajagopalan S, Xu Y, Brenner MB. Science. 1994;263:387–390. doi: 10.1126/science.8278814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swanton E, High S, Woodman P. EMBO J. 2003;22:2948–2958. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loo TW, Clarke DM. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:28683–28689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leach MR, Cohen-Doyle MF, Thomas DY, Williams DB. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;6:6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leach MR, Williams DB. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:9072–9079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith MM, Lindstrom J, Merlie JP. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:4367–4376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu Y, Ralston E, Murphy-Erdosh C, Hall ZW. J. Cell Biol. 1989;109:729–738. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.2.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ross AF, Green WN, Hartman DS, Claudio T. J. Cell Biol. 1991;113:623–636. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.3.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelman MS, Chang W, Thomas DY, Bergeron JJ, Prives JM. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:15085–15092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green WN, Wanamaker CP. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:20945–20953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sumikawa K, Gehle VM. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:6286–6290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gehle VM, Walcott EC, Nishizaki T, Sumikawa K. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1997;45:219–229. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller SH, Lindstrom J, Taylor P. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:22871–22877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green WN, Claudio T. Cell. 1993;74:57–69. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90294-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Margolskee RF, McHendry-Rinde B, Horn R. BioTechniques. 1993;15:906–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Claudio T, Green WN, Hartman DS, Hayden D, Paulson HL, Sigworth FJ, Sine SM, Swedlund A. Science. 1987;238:1688–1694. doi: 10.1126/science.3686008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee BS, Gunn RB, Kopito RR. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:11448–11454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wada I, Imai S, Kai M, Sakane F, Kanoh H. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:20298–20304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eertmoed AL, Vallejo YF, Green WN. Methods Enzymol. 1998;293:564–585. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)93034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green WN, Wanamaker CP. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:5555–5564. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-15-05555.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ou WJ, Cameron PH, Thomas DY, Bergeron JJ. Nature. 1993;364:771–776. doi: 10.1038/364771a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang W, Gelman MS, Prives JM. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:28925–28932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schrag JD, Bergeron JJ, Li Y, Borisova S, Hahn M, Thomas DY, Cygler M. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:633–644. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pollock S, Kozlov G, Pelletier MF, Trempe JF, Jansen G, Sitnikov D, Bergeron JJ, Gehring K, Ekiel I, Thomas DY. EMBO J. 2004;23:1020–1029. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ou WJ, Bergeron JJ, Li Y, Kang CY, Thomas DY. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:18051–18059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.18051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Claudio T, Paulson HL, Green WN, Ross AF, Hartman DS, Hayden DA. J. Cell Biol. 1989;108:2277–2290. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.6.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paulson HL, Ross AF, Green WN, Claudio T. J. Cell Biol. 1991;113:1371–1384. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.6.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merlie JP, Sebbane R, Tzartos S, Lindstrom J. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:2694–2701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sumikawa K, Miledi R. Mol. Brain Res. 1989;5:183–192. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(89)90034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson DJ, Blobel G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1981;78:5598–5602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christianson JC, Green WN. EMBO J. 2004;23:4156–4165. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Molinari M, Helenius A. Science. 2000;288:331–333. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daniels R, Kurowski B, Johnson AE, Hebert DN. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:79–90. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00821-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keller SH, Lindstrom J, Taylor P. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:17064–17072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.17064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frickel EM, Riek R, Jelesarov I, Helenius A, Wuthrich K, Ellgaard L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:1954–1959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042699099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nair S, Wearsch PA, Mitchell DA, Wassenberg JJ, Gilboa E, Nicchitta CV. J. Immunol. 1999;162:6426–6432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basu S, Srivastava PK. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:797–802. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.5.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jorgensen CS, Heegaard NH, Holm A, Hojrup P, Houen G. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:2945–2954. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2000.01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ihara Y, Cohen-Doyle MF, Saito Y, Williams DB. Mol. Cell. 1999;4:331–341. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80335-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Molinari M, Helenius A. Nature. 1999;402:90–93. doi: 10.1038/47062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zapun A, Darby NJ, Tessier DC, Michalak M, Bergeron JJ, Thomas DY. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:6009–6012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blount P, Smith MM, Merlie JP. J. Cell Biol. 1990;111:2601–2611. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saedi MS, Conroy WG, Lindstrom J. J. Cell Biol. 1991;112:1007–1015. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.5.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gu Y, Forsayeth JR, Verrall S, Yu XM, Hall ZW. J. Cell Biol. 1991;114:799–807. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.4.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]