Abstract

We have evaluated the interaction energy of a three-residue ionic network constructed on the β-sheet surface of protein G using double mutant cycles. Although the two individual ion pairs were each stabilizing by ∼0.6 kcal/mol, the excess gain in stability for the triad was small (0.06 kcal/mol).

Keywords: β-Sheet, protein stability, protein design, electrostatics, side chain interactions

The β-sheet surface of the protein G immunoglobulin-binding domain B1 (GB1) has been used as a model system for evaluating the β-sheet forming propensities of amino acids (Minor and Kim 1994; Smith et al. 1994). These studies, in combination with statistical surveys of known structures and theoretical models of β-sheet propensity provide some general guidelines for amino acid selection in β-sheet design (Munoz and Serrano 1994; Street and Mayo 1999).

An important next step in understanding β-sheet stability is to define the role of side chain interactions such as hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions. In particular, the energetic effects of surface ionic interactions have been debated. Solvent-exposed ion pairs have been found to stabilize folded proteins in a number of cases (Horovitz et al. 1990; Serrano et al. 1990; Lyu et al. 1992; Spek et al. 1998; Takano et al. 2000). In the context of the β-sheet surface environment, ion pairs have been reported to stabilize folded proteins by 0.4–1 kcal/mol (Smith and Regan 1995; Blasie and Berg 1997; Merkel et al. 1999). However, some surface ion pairs exhibit neutral or destabilizing effects (Dao-pin et al. 1991; Strop and Mayo 2000). The high dielectric of the aqueous environment and the loss of side chain conformational freedom have been invoked to explain the marginal stabilizing effects of some pairwise electrostatic interactions.

Networks of charged surface residues have been observed in hyperthermophile proteins and have been proposed to offer an energetic advantage over single ion pairs due to the reduced entropic cost of fixing a third residue (Dao-pin et al. 1991; Yip et al. 1995). Indeed, two analyses of solvent-exposed ionic triads in α-helical regions have shown that three-residue networks offer a stabilizing effect greater than would be observed for the sum of the two individual pairwise interactions (Horovitz et al. 1990; Spek et al. 1998).

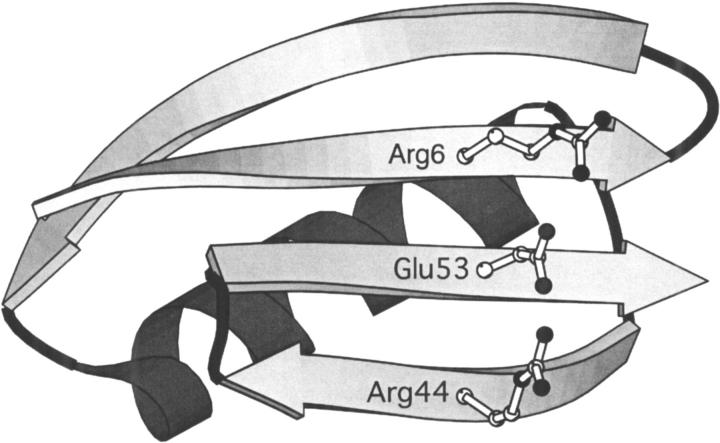

To test the effect of an ionic triad in the context of the β-sheet surface, we have evaluated the energetic contribution of a three-residue triad constructed on the β-sheet surface of GB1. The network consists of Arg6, Glu53, and Arg44, residues that lie on three adjacent strands of the β-sheet surface (Fig. 1A ▶). Double mutant cycle analysis was used to isolate the interaction energy of the triad (Horovitz and Fersht 1990). Eight GB1 variants were constructed, which represent all permutations of Arg or Ile at position 6, Glu or Ala at position 53, and Arg or Ala at position 44. In this three-residue thermodynamic cycle, the interaction energy of the ionic network is calculated as in equation 1.

Fig. 1.

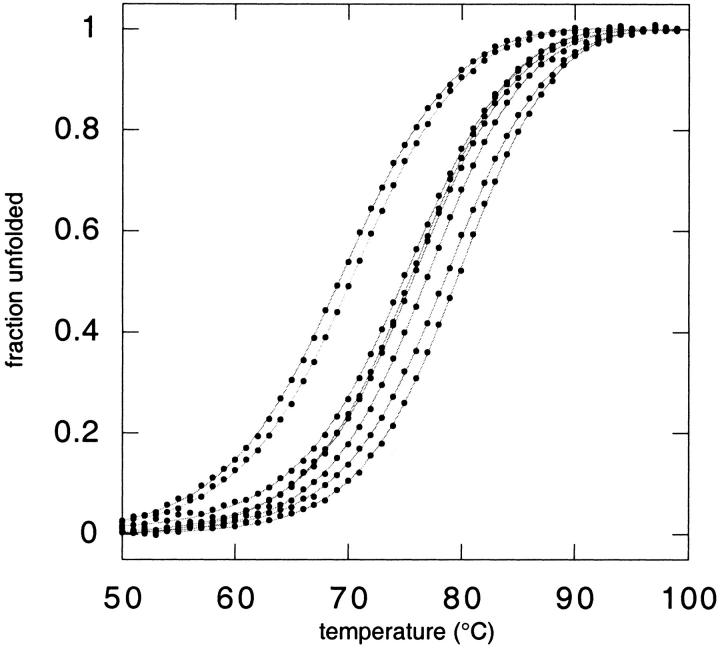

(A) The β-sheet surface of GB1 showing possible orientations for side chains Arg6, Glu53, and Arg44. In the positions shown, nitrogen–oxygen distances are 2.92 Å and 2.85 Å for residue pairs 6–53 and 44–53, respectively. Side chains were positioned with a dead-end elimination algorithm (Voigt et al. 2000) and the figure was created with MOLSCRIPT (Kraulis 1991). (B) Thermal denaturation curves for GB1 variants. From left to right (at 50% unfolded): R6A53R44, R6A53A44,I6A53R44, I6A53A44,R6E53A44, I6E53A44,R6E53R44, and I6E53R44.

|

(1) |

ΔGXYZ is the free energy of unfolding for the GB1 mutant with amino acids X, Y, and Z at positions 6, 53, and 44, respectively. The interaction energy of an Arg-Glu ion pair in the presence of another residue X is calculated as in equation 2.

|

(2) |

Free energies of unfolding (ΔG) were evaluated by two-state analysis of thermal denaturation curves monitored by circular dichroism (CD) (Fig. 1B ▶).

The variant containing both a single ion pair and isoleucine, I6E53R44, had the highest Tm and ΔG of unfolding (Table 1), whereas the variant with the ionic triad, R6E53R44, was only slightly less stable. It is interesting to note that the addition of the third charged residue almost fully compensates for the loss of the β-branched (and therefore β-sheet stabilizing) amino acid.

Table 1.

Stability data for GB1 variants

| Variant | Tm (°C) | ΔHTm (kcal/mol) | ΔG (75°C) (kcal/mol) |

| R6E53R44 | 79.1 ± 0.5 | 53.5 ± 2.0 | 0.61 |

| R6E53A44 | 76.1 ± 0.4 | 52.3 ± 2.0 | 0.16 |

| R6A53R44 | 69.6 ± 0.3 | 45.0 ± 1.6 | −0.74 |

| R6A53A44 | 70.6 ± 0.3 | 46.6 ± 1.5 | −0.62 |

| I6E53R44 | 80.1 ± 0.6 | 56.1 ± 2.5 | 0.79 |

| I6E53A44 | 77.2 ± 0.4 | 54.1 ± 1.9 | 0.34 |

| I6A53R44 | 75.5 ± 0.3 | 50.1 ± 1.5 | 0.08 |

| I6A53A44 | 76.0 ± 0.3 | 51.4 ± 1.6 | 0.14 |

Tm = midpoint of thermal denaturation transition; ΔHTm = enthalpy of unfolding at Tm; ΔG (75°C) = free energy of unfolding calculated at 75°C.

Interaction energies of the Arg6–Glu53 pair were 0.58 kcal/mol in the presence of Ala44 and 0.64 kcal/mol in the presence of Arg44 (Table 2). The Arg44–Glu53 pair had interaction energies of 0.51 kcal/mol (in the presence of Ile6) and 0.57 kcal/mol (with Arg6). This level of stabilization is consistent with other surface electrostatic interactions studied by double mutant cycles (Serrano et al. 1990; Spek et al. 1998; Merkel et al. 1999).

Table 2.

Interaction energies for ion pairs and the three-residue network

| Interaction | ΔΔG (75°C) Kcal/mol | ΔΔΔG (75°C) Kcal/mol |

| R6E53 (A44) | 0.58 | |

| R6E53 (R44) | 0.64 | |

| E53R44 (I6) | 0.51 | |

| E53R44 (R6) | 0.57 | |

| R6E53R44 | 0.06 |

ΔΔG (75°C) interaction energy (calculated at 75°C) of the ion pair in the presence of the residue indicated in parentheses; ΔΔΔG (75°C) interaction energy (calculated at 75°C) of the triad as described in the text.

Although the pairwise electrostatic interactions are clearly favorable, the ionic network does not appear to significantly enhance GB1 stability any more than the simple sum of the individual pairs. As shown in Table 2, the interaction energy of unfolding for the ionic network, ΔΔΔGinteraction, determined at 75°C (approximately the average Tm for the eight variants) was 0.06 kcal/mol. This very low interaction energy suggests that the contributions of the ion pairs are additive; there is no additional stabilization of one ion pair in the presence of a third charged residue. In contrast, previous studies of charged networks on α-helices using the double mutant cycle method showed stabilizing interaction energies of 0.77 kcal/mol for an Asp–Arg–Asp triad (Horovitz et al. 1990) and 0.65 kcal/mol for an Arg–Glu–Arg triad (Spek et al. 1998).

The lack of a significant stabilizing interaction energy of the Arg6–Glu53–Arg44 triad may be due to a variety of factors. Previously reported factors such as desolvation, side chain entropy loss, and conformational strain may counteract the electrostatic benefits of the network. However, the local environment of the triad, including secondary structure and neighboring residues, may also affect the magnitude of the interaction energy of the triad. Further studies on β-sheet surface electrostatic interactions may help to clarify whether or not secondary structure influences the stabilizing effect of ionic networks.

Materials and methods

Mutagenesis and protein expression

GB1 variants were constructed by inverse PCR mutagenesis and expressed using the T7 promoter system as previously described (Su and Mayo 1997). Purification of 57-residue GB1 variants containing an amino-terminal methionine was accomplished by reverse phase HPLC and verified by mass spectrometry.

Thermal denaturation

The increase in CD signal at 218 nm was followed during thermal unfolding from 1°C to 99°C using 50 μM protein in 50 mM sodium phosphate at pH 5.5. The midpoint of the thermal denaturation (Tm) and the enthalpy of unfolding (ΔH) were determined from a two-state analysis of each denaturation curve (Minor and Kim 1994; Smith et al. 1994). The change in heat capacity upon unfolding (ΔCp) was held constant at 0.621 kcal/K • mol, a value previously reported for wild-type GB1 (Alexander et al. 1992). ΔG values were assigned using the Gibbs-Helmholtz relation with ΔCp = 0.621 kcal/K • mol (Minor and Kim 1994; Smith et al. 1994). The average error in calculating ΔG (as determined from curve fitting) was 0.06 kcal/mol.

Acknowledgments

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.23502.

References

- Alexander, P., Fahnestock, S., Lee, T., Orban, J., and Bryan, P. 1992. Thermodynamic analysis of the folding of the streptococcal protein-G IgG-binding domains B1 and B2—Why small proteins tend to have high denaturation temperatures. Biochemistry 31 3597–3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasie, C.A. and Berg, J.M. 1997. Electrostatic interactions across a beta-sheet. Biochemistry 36 6218–6222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dao-pin, S., Sauer, U., Nicholson, H., and Matthews, B.W. 1991. Contributions of engineered surface salt bridges to the stability of T4 lysozyme determined by directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry 30 7142–7153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horovitz, A., Serrano, L., Avron, B., Bycroft, M., and Fersht, A.R. 1990. Strength and cooperativity of contributions of surface salt bridges to protein stability. J. Mol. Biol. 216 1031–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horovitz, A. and Fersht, A.R. 1990. Strategy for analyzing the cooperativity of intramolecular interactions in peptides and proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 214 613–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis, P.J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallography 24 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, P.C.C., Gans, P.J., and Kallenbach, N.R. 1992. Energetic contribution of solvent-exposed ion-pairs to alpha-helix structure. J. Mol. Biol. 223 343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkel, J.S., Sturtevant, J.M., and Regan, L. 1999. Sidechain interactions in parallel beta sheets: The energetics of cross-strand pairings. Structure 7 1333–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor, D.L. and Kim, P.S. 1994. Measurement of the β-sheet-forming propensities of amino acids. Nature 367 660–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz, V. and Serrano, L. 1994. Intrinsic secondary structure propensities of the amino-acids, using statistical phi-psi matrices—Comparison with experimental scales. Proteins 20 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, L., Horovitz, A., Avron, B., Bycroft, M., and Fersht, A.R. 1990. Estimating the contribution of engineered surface electrostatic interactions to protein stability by using double-mutant cycles. Biochemistry 29 9343–9352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.K. and Regan, L. 1995. Guidelines for protein design-the energetics of β sheet side-chain interactions. Science 270 980–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.K., Withka, J.M., and Regan, L. 1994. A thermodynamic scale for the β-sheet forming propensities of the amino acids. Biochemistry 33 5510–5517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spek, E.J., Bui, A.H., Lu, M., and Kallenbach, N.R. 1998. Surface salt bridges stabilize the GCN4 leucine zipper. Protein Sci. 7 2431–2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street, A.G. and Mayo, S.L. 1999. Intrinsic beta-sheet propensities result from van der Waals interactions between side chains and the local backbone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96 9074–9076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strop, P. and Mayo, S.L. 2000. Contribution of surface salt bridges to protein stability. Biochemistry 39 1251–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, A. and Mayo, S.L. 1997. Coupling backbone flexibility and amino acid sequence selection in protein design. Protein Sci. 6 1701–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano, K., Tsuchimori, K., Yamagata, Y., and Yutani, K. 2000. Contribution of salt bridges near the surface of a protein to the conformational stability. Biochemistry 39 12375–12381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt, C.A., Gordon, D.B., and Mayo, S.L. 2000. Trading accuracy for speed: A quantitative comparison of search algorithms in protein sequence design. J. Mol. Biol. 299 789–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip, K.S.P., Stillman, T.J., Britton, K.L., Artymiuk, P.J., Baker, P.J., Sedelnikova, S.E., Engel, P.C., Pasquo, A., Chiaraluce, R., Consalvi, V., Scandurra, R., and Rice, D.W. 1995. The structure of pyrococcus-furiosis glutamate-dehydrogenase reveals a key role for ion-pair networks in maintaining enzyme stability at extreme temperatures. Structure 3 1147–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]