Abstract

Electrostatic contributions to the conformational stability of apoflavodoxin were studied by measurement of the proton and salt-linked stability of this highly acidic protein with urea and temperature denaturation. Structure-based calculations of electrostatic Gibbs free energy were performed in parallel over a range of pH values and salt concentrations with an empirical continuum method. The stability of apoflavodoxin was higher near the isoelectric point (pH 4) than at neutral pH. This behavior was captured quantitatively by the structure-based calculations. In addition, the calculations showed that increasing salt concentration in the range of 0 to 500 mM stabilized the protein, which was confirmed experimentally. The effects of salts on stability were strongly dependent on cationic species: K+, Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ exerted similar effects, much different from the effect measured in the presence of the bulky choline cation. Thus cations bind weakly to the negatively charged surface of apoflavodoxin. The similar magnitude of the effects exerted by different cations indicates that their hydration shells are not disrupted significantly by interactions with the protein. Site-directed mutagenesis of selected residues and the analysis of truncation variants indicate that cation binding is not site-specific and that the cation-binding regions are located in the central region of the protein sequence. Three-state analysis of the thermal denaturation indicates that the equilibrium intermediate populated during thermal unfolding is competent to bind cations. The unusual increase in the stability of apoflavodoxin at neutral pH affected by salts is likely to be a common property among highly acidic proteins.

Keywords: Electrostatics, protein stability, flavodoxin, ion binding, ionic strength, cations, protein folding.

Electrostatic interactions among the charged moieties of surface ionizable residues can contribute significantly to the conformational stability of proteins. These electrostatic effects are responsible for the salt and pH dependence of stability (Matthew et al. 1985). Several lines of experimental evidence indicate that individual pairwise electrostatic interactions among surface charged residues are generally weak. For example, the pKa values of surface residues are on average within 0.5 pKa units from the pKa values of model compounds (Matthew et al. 1985, Shaw et al. 2001), presumably because charged atoms at protein surfaces are not markedly dehydrated or strongly influenced electrostatically by other polar and charged atoms in the protein (Loewenthal et al. 1993). In some cases the pKa values of surface residues are not perturbed significantly by the elimination of neighboring charged groups (Forsyth and Robertson 2000). In fact, charged residues can often be substituted by neutral ones without affecting the global stability of proteins significantly (Meeker et al. 1996; Irún et al. 2001a). On the other hand, recent experimental studies have shown that the stability of some proteins can be enhanced by a judicious alteration of the pattern of interactions among charged surface residues (Grimsley et al. 1999; Loladze et al. 1999; Spector et al. 2000). Apparently, the discrete contributions by individual charged groups can add up to significant global effects. Detailed experimental studies of electrostatic contributions to stability are still necessary to learn how to modulate protein stability effectively by reconfiguring the constellation of surface charges.

The present study on apoflavodoxin was motivated partly by an interest in characterizing electrostatic interactions in a highly acidic protein. Salt- and pH-dependent contributions to stability have been explored systematically in many basic proteins such as myoglobin, nuclease, cytochrome c, lysozyme, and ribonuclease A (Matthew et al. 1985 and references therein). Except for studies by Pace and coworkers on RNase T1 and RNase Sa, the electrostatic properties of acidic proteins remain largely unexplored (Shaw et al. 2001 and references therein). Interest in acidic proteins stems from the notion that some electrostatic properties of proteins depend on the isoionic point (Linderstrøm-Lang 1924). For example, the salt dependence of pKa values of ionizable groups is thought to be determined by the distance between the pKa value and the isoionic point (Antosiewicz et al. 1994). In proteins where basic and acidic residues are evenly distributed over the surface, short range and long range, attractive and repulsive coulombic interactions are balanced at the isoionic point, and the isoionic point is salt insensitive. Conversely, the pKa values of residues that ionize at pH values far from the pI, where the balance of attractive and repulsive interactions might be skewed, are expected to be more salt sensitive than those that ionize at pH values where the net charge is close to zero. The pH dependence of stability is also likely to be affected by the net charge of the protein, especially in highly charged proteins, in which long-range electrostatic interactions can contribute significantly to the stability of the native state. In the classical view of protein electrostatics, the electrostatic contributions to stability are expected to be maximal at the isoionic point of a protein, and the salt dependence of stability at a given pH is expected to be determined by the distance to the isoionic point. This view has been challenged recently by experiments with proteins whose isoionic points have been altered systematically by charge-reversal mutations. The pH of maximum stability of these proteins is independent of the isoionic point (Grimsley et al. 1999; Shaw et al. 2001).

A second aim of this study was to test further the ability of empirical structure-based methods to capture the pH and salt dependence of stability of proteins. Continuum methods for structure-based calculations of electrostatic properties of proteins have evolved significantly over the past 20 years. Model-dependent solutions of the linearized Poisson-Boltzmann equation, as embodied in the empirical solvent-accessibility modified Tanford-Kirkwood (SATK) algorithm (Matthew et al. 1985), have been superseded by more rigorous numerical solutions based on the method of finite differences (FDPB) (Antosiewicz et al. 1996 and references therein). In addition to a more refined treatment of the topology of the protein-water interface, the FDPB calculations are capable of handling explicitly the self-energy terms that are ignored in the SATK method (Antosiewicz et al. 1996 and references therein). Ironically, it has been shown previously that the empirical SATK method captures correctly the ionization energies of surface groups (Matthew et al. 1985). Its performance is comparable, or even better, to the more rigorous FDPB method, which tends to exaggerate the magnitude of electrostatic effects when applied to a static structure, even if the protein interior is treated with arbitrarily high protein dielectric constants (Antosiewicz et al. 1996). Here we assess if the SATK method, which captures successfully many electrostatic properties of basic proteins (Matthew et al. 1985), succeeds in capturing the character of electrostatic effects in a highly acidic protein such as apoflavodoxin. This protein is a good test case as the pH dependence of its stability and the effects of salt on stability at neutral pH are somewhat unusual.

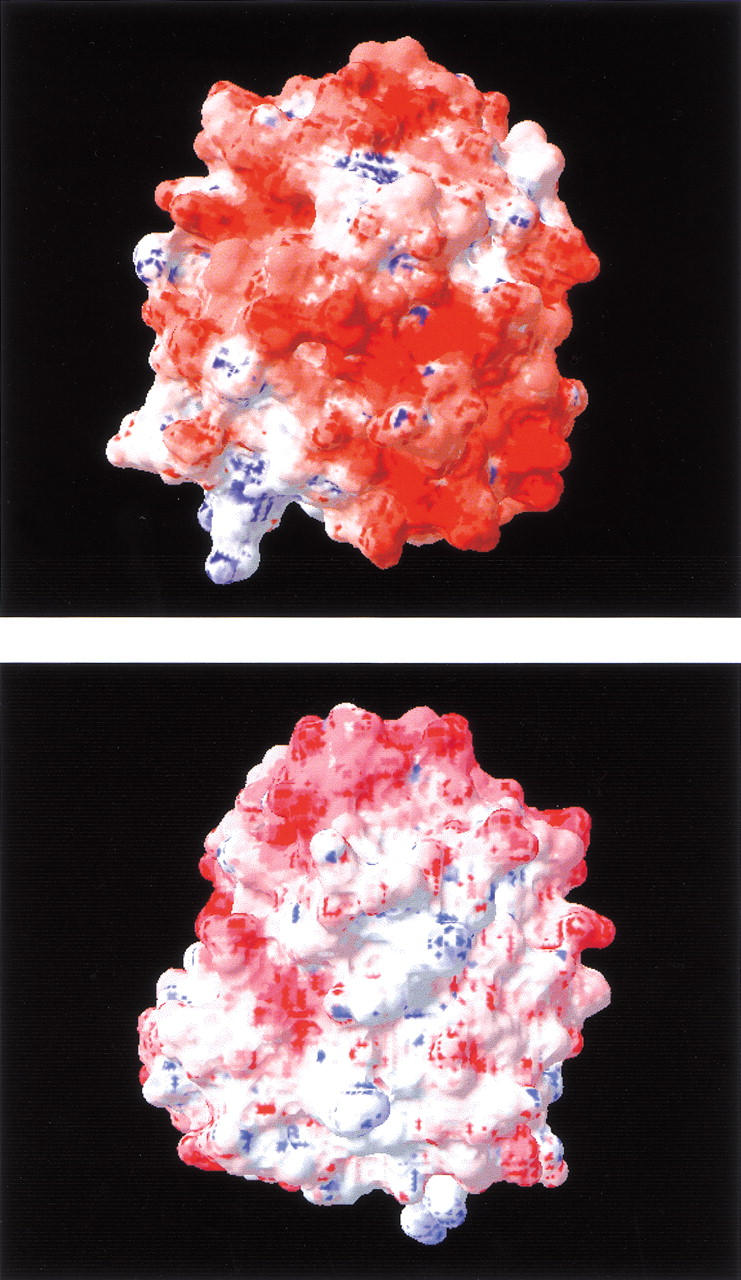

Flavodoxins are electron transfer proteins that carry a noncovalently bound FMN molecule that can be easily removed (Rogers 1987; Ludwig and Luschinsky 1992; Mayhew and Tollin 1992). Apoflavodoxin is quite a useful model protein for studying the stability and folding properties of proteins (Genzor et al. 1996a,b; Maldonado et al. 1998; Fernández-Recio et al. 1999; Irún et al. 2001a,b; Langdon et al. 2001). The apoflavodoxin from Anabæna PCC 7119 (Fillat et al. 1991) is a 169 amino acid-long α/β protein whose equilibrium urea denaturation follows a two-state mechanism (Genzor et al. 1996b; Langdon et al. 2001), whereas the equilibrium thermal unfolding is three-state (Irún et al. 2001a,b). It contains 31 acidic residues (11 glutamic and 20 aspartic acids) and 15 basic ones (10 lysines, 4 arginines, and 1 histidine). The high content of negative charges in this protein is reflected in the large negative electrostatic potentials on its surface (Fig. 1 ▶). Apoflavodoxin bears a large negative charge at neutral pH and its conformational stability at this pH is strongly influenced by salts. We have studied the conformational stability of apoflavodoxin as a function of pH and salt concentration and compared experimental values with the results of structure-based calculations. The pH dependence of stability differs from the one commonly observed in basic proteins such as nuclease (Whitten and García-Moreno 2000) and myoglobin (Matthew et al. 1985). At neutral pH, apoflavodoxin is stabilized by increasing salt concentrations. The chloride salts of choline, Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ were used to dissect the salt effect into contributions by the general ionic strength effect and by ion-specific effects. Cation-specific effects were found to be significant. The physical character of protein-cation interactions was investigated by site-directed mutagenesis and structure-based calculations. Both the pH and the salt dependence of stability indicate that destabilizing electrostatic interactions between negatively charged groups are significant at pH values above 4. Interesting similarities exist between the observed effects of salt on conformational properties of apoflavodoxin at neutral pH and those on acid-denatured proteins.

Fig. 1.

Surface electrostatic potentials of apoflavodoxin calculated at pH 7.0 and I = 0 mM with the program spdbviewer (Guex and Peitsch 1997). The potentials are color coded from blue (positive) to red (negative).

Results

pH dependence of stability of wild-type apoflavodoxin

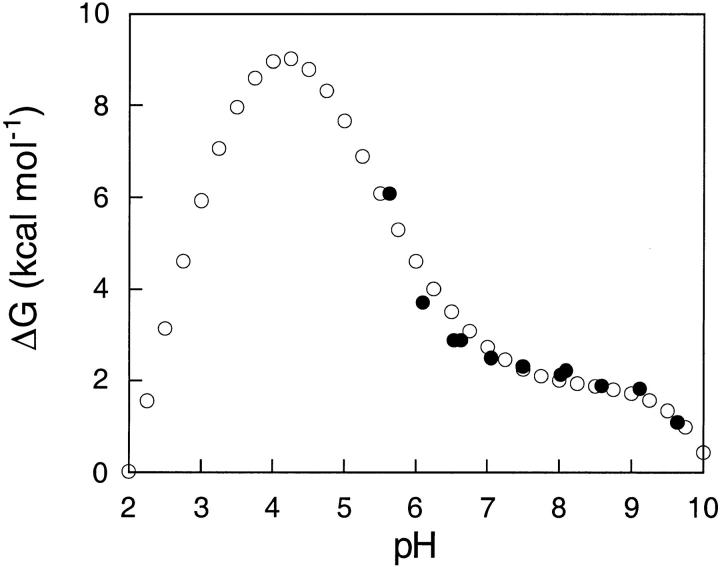

The calculated and the experimental pH dependence of apoflavodoxin stability measured in 10 mM ionic strength at 298 K is shown in Figure 2 ▶. According to the structure-based calculations, the electrostatic contributions to global stability are stabilizing throughout the pH range of 2 to 10. The predicted isoionic point over the range of ionic strength 10 mM to 400 mM is pH 4. The electrostatic contributions to the stability of this protein are maximal near the isoionic point and lower at all other pH values.

Fig. 2.

pH dependence of the conformational stability of apoflavodoxin. All data were measured or calculated at 25°C and ionic strength of 10 mM. (open circles) Electrostatic contributions to stability calculated with the solvent-accessibility modified Tanford-Kirkwood (SATK) method. (closed circles). Global free energy of denaturation determined by urea denaturation. The latter data are plotted after subtracting 1.3 kcal mole−1 to superimpose it with the stability profile calculated from structure. The following buffers were used at the appropriate concentration to ensure constant ionic strength: pH 5.5–6.6 (MES); pH 6.5–8.1 (MOPS); pH 8.1–9.6 (CHES). Protein concentration was 2 μM. An averaged value of m = 2.25 kcal mole−1 M−1 was used to calculate ΔG at a given pH from the concentration at the point of mid-denaturation. The estimated systematic error (Fernández-Recio et al. 1999) of the measured free energies is of ±0.5 kcal mole−1. However, the relative error of a difference between two energy values is of only 0.06 kcal mole−1. This means that all the experimental points (closed circles) could be simultaneously shifted by ±0.5 kcal mole−1 along the Y axis.

In the pH range of 5.5 to 9.5 the agreement between the pH dependence of stability predicted from structure and the one determined by urea denaturation experiments is excellent. The comparison between predicted and measured stabilities is only possible at pH >5 because of the increased insolubility of the protein near its isoelectric point (Genzor et al. 1996b). At pH values below the isoelectric point, the protein in solution exists in an altered conformation reminiscent of a molten globule; thus all comparisons between calculated and measured values below pH 5 would be meaningless. Use of the structure at pH 6.0 for the calculation of electrostatic stability curves over the wide range of pH studied is validated by the observation that the crystallographic structures at pH 6.0 (Genzor et al. 1996b) and at pH 9.0 (Fernández-Recio et al. 1999) are indistinguishable. Except for very minor local changes at His34, apoflavodoxin does not undergo any crystallographically detectable conformational change in this pH range.

In the pH range of 5.5 to 9.5, the measured conformational stability of apoflavodoxin is on average 1.3 kcal mole−1 higher than the calculated electrostatic free energy. This indicates that in the absence of stabilizing electrostatic interactions, the stability of apoflavodoxin would be marginal, close to 1 kcal mole−1. It is noteworthy that the net contributions from interactions among charged atoms to the stability of this protein are stabilizing because flavodoxin has nearly twice as many acidic residues as basic ones. The arrangement of the ionizable side chains on the surface of the protein is such that the destabilization arising from medium- to long-range repulsive interactions among the large number of acidic residues is offset by stabilizing short- and medium-range interactions between residues of opposite polarity. The nearly quantitative agreement between calculated and measured pH dependence of stability indicates that the semiempirical SATK method that was used to compute electrostatic energies captures correctly the balance between short-range and long-range electrostatic effects, at least in the limit of low ionic strength. This is consistent with previous studies demonstrating the ability of this empirical method to estimate accurately the pKa values of surface ionizable residues (Kao et al. 2000; Matthew et al. 1985).

Effects of ionic strength on the stability of apoflavodoxin

Under conditions of pH in which the net effect of electrostatic interactions is stabilizing, the effects of increasing salt concentration are expected to be destabilizing because of screening of the net favorable electrostatic interactions by the ionic strength. In the case of apoflavodoxin, the calculations show that its stability at neutral pH should increase with increasing ionic strength. This unusual response to increasing salt concentration originates with the balance between long-range and short-range interactions characteristic of highly acidic proteins at neutral pH. Because of the large number of acidic residues, at pH 7 there are substantial, repulsive, long-range electrostatic interactions. These repulsive interactions are screened very effectively under conditions of high ionic strength, more effectively than the short-range attractive interactions. Thus the conformational stability of apoflavodoxin increases under conditions of high ionic strength. This is likely to be a property common to all acidic proteins.

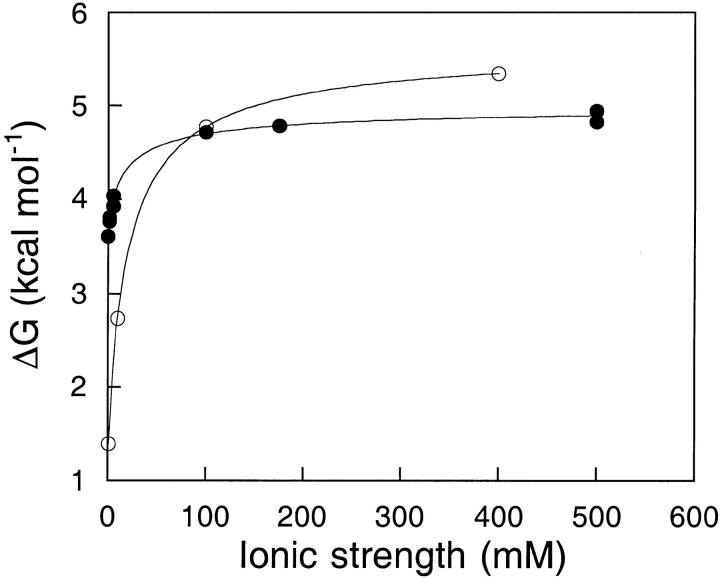

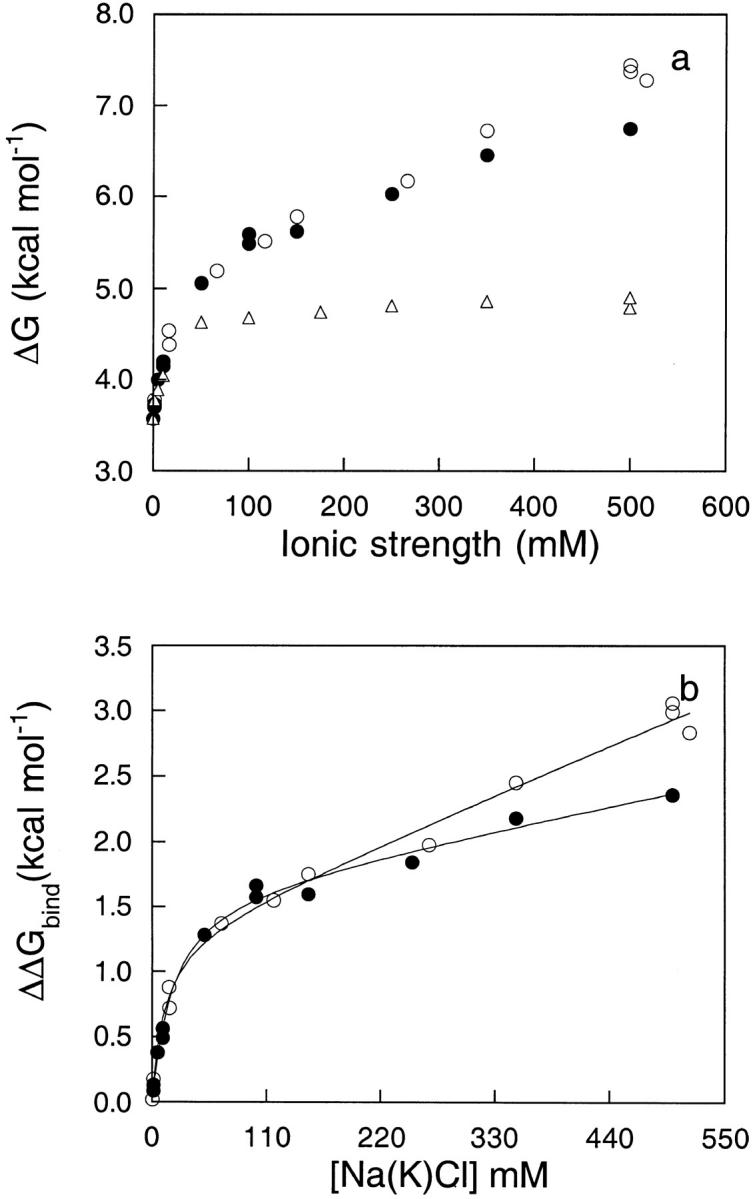

The ionic strength dependence of the stability of apoflavodoxin determined by urea denaturation at pH 7 is shown in Figure 3 ▶. Choline chloride was used to regulate the ionic strength in these experiments because the choline cation is bulky; thus it is unlikely to bind directly to the negatively charged surface of the protein. Use of choline chloride as the support electrolyte enabled the dissection of the salt effect into general ionic strength effects and salt-specific effects. The ionic strength dependence of stability at pH 7 calculated from structure with the SATK method is also shown in Figure 3 ▶. The calculated trend follows the experimental data qualitatively; in both experiment and calculations the ionic strength <100 mM has the greatest effect on stability. However, the measured increase in stability between the ionic strengths of 1 mM to 500 mM is ∼1 kcal mole−1, which is considerably smaller than the 4 kcal mole−1 increase predicted in this range by the structure-based calculations.

Fig. 3.

Conformational stability of apoflavodoxin as a function of ionic strength. All data were calculated or measured at pH 7.0 and 25°C. (open circles). Electrostatic contributions to stability calculated with the SATK method. The calculated values only describe the effects of ionic strength on stability. (closed circles) Global free energy of denaturation determined by urea denaturation. The experiments were performed in 1 mM MOPS with different amounts of choline chloride, using a 2-μM protein concentration. An average m value of 2.25 kcal mole−1 M−1 was used to calculate the conformational stability from the midpoint urea concentration. The relative error of a difference between two energy values is of only 0.06 mole−1. The lines are simple interpolations.

The explanation behind the discrepancy between the magnitude of the calculated and the observed salt effect on the stability of flavodoxin is not obvious. In a recent H-NMR study of the salt dependence of pKa values of histidines in myoglobin (Kao et al. 2000), it was established that the SATK algorithm used to calculate the curve in Figure 3 ▶ is fairly robust in the estimation of ionic strength effects. Furthermore, the data in Figure 2 ▶ indicate that in the limit of low ionic strength the algorithm captures correctly the magnitude of electrostatic interactions in apoflavodoxin. Three factors can be invoked to explain the discrepancy between predicted and measured salt dependence of stability. First, the calculation of electrostatic contributions to conformational stability of the native state assumes the total absence of electrostatic interactions in the denatured state. The presence of electrostatic interactions in the denatured state will result in discrepancy between the calculated effect of pH on stability and the effect measured by urea denaturation. Recent experimental evidence indicates that in other proteins, electrostatic interactions in denatured states can be significant (Whitten and García-Moreno 2000). The possibility of strong electrostatic effects in the denatured state of apoflavodoxin cannot be excluded, especially considering the high linear density of Glu and Asp in some sections of the sequence. Because the calculated and the measured pH dependence of stability in 10 mM ionic strength (Fig. 2 ▶) agree quantitatively, the discrepancy between experiment and theory at higher ionic strengths would require the compaction of the denatured state with increasing ionic strength. A compact denatured state would have more native-like electrostatic interactions than the expanded denatured state populated under conditions of low ionic strength. A second factor that might explain the discrepancy between the measured and the calculated ionic strength dependence of stability is the size of the choline cation. At pH 7, in ionic strength 1 mM, the predicted net charge in apoflavodoxin is −17. The calculated electrostatic potential of this protein at this pH value is negative throughout the entire surface of the protein (Fig. 1 ▶). Therefore, salt effects are expected to be dominated by interactions between the protein and cations. Although the electrostatic potentials of proteins calculated with the Poisson-Boltzmann equation are generally insensitive to the size of the ionic species, the significant difference between the size of Na+ used in the calculations and that of choline used in the experiments could result in the observed discrepancy. Finally, a third possibility is that the structure-based calculations are only valid in the limit of low ionic strength. To better understand the molecular origins of the unusual salt dependence of apoflavodoxin stability, the effects of different monovalent and divalent cations were studied.

Effects of choline, Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ on the stability of apoflavodoxin at 25°C

To elucidate the contributions by cation-specific effects to the salt dependence of apoflavodoxin stability, we compared the effects of choline chloride with those of the chloride salts of Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+. All measurements were performed under a constant ionic strength of 500 mM. The salt dependence of stability of a protein is expected to be sensitive to specific cation species when direct chemical interactions are present. The data in Table 1 show that the stabilizing effects of Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ are similar (∼3 kcal mole−1) and clearly higher than the effect exerted by choline at the same ionic strength (1.3 kcal mole−1).

Table 1.

Stability of wild-type apoflavodoxin in MOPS 1 mM, pH 7.0 at 25°C, in the presence of different salts at a constant ionic strength of 500 mM

| Salt | Concentration (M) | U1/2 (M) | ΔGa (kcal mol−1) |

| — | — | 1.59 | 3.58 |

| Chol Cl | 0.50 | 2.18 | 4.91 |

| NaCl | 0.50 | 3.28 | 7.38 |

| KCl | 0.50 | 2.87 | 6.46 |

| MgCl2 | 0.16 | 2.84 | 6.39 |

| CaCl2 | 0.16 | 2.71 | 6.10 |

a Calculated from U1/2 and a mean value of m = 2.25. From the spread of m and U1/2 values determined in our laboratory for apoflavodoxin (Fernández-Recio et al. 1999) we estimated that although each calculated free energy may have a systematic error of ±0.5 kcal mole−1, the error in the difference between two energies is of only ±0.06 kcal mole−1 (Fernández-Recio et al. 1999).

Cation-specific effects on the stability of apoflavodoxin at neutral pH

The dependence of stability of apoflavodoxin on NaCl and KCl concentration was studied in greater depth to further analyze cation-specific effects. The data in Figure 4a ▶ show that Na+ and K+ are more effective than choline in stabilizing the native state of apoflavodoxin at neutral pH. To obtain a measure of the net influence of cation binding on apoflavodoxin stability, the effect of choline was subtracted. This assumes that the effects associated with choline reflect the ionic strength effects and that these are truly independent of the size and chemical properties of the cations. This use of the term "ionic strength" adheres strictly to the definition implicit in the Poisson-Boltzmann equation, proposed originally by Debye and Hückel, to describe an electrical property of a solution that depends solely on the concentration and valence of its component ions. To the extent that the effect of choline does reflect a pure ionic strength effect, the data in Figure 4b ▶ describe the net increase in stability caused by cation binding as a function of cation concentration. It is noteworthy that the observed effect for Na+ and K+ are almost identical, particularly at low salt concentrations.

Fig. 4.

(a) Conformational stability of apoflavodoxin as a function of Na+ (open circles), K+ (closed circles), and choline chloride (open triangles). A 2-μM protein concentration was used. The relative error of a difference between two energy values is of only 0.06 kcal mole−1. (b) Specific effect of Na+ (open circles) and K+ (closed circles) on the conformational stability of apoflavodoxin in 1 mM MOPS, pH 7.0, and 25°C obtained by subtracting the choline curve (ionic strength effect) from the cation curves. The solid lines are fits to equation 3. The fitting yields n = 1.3, ΔΔGbound-free = 1.3 kcal mole−1, Kb = 37 M−1, and α = 0.0033 for Na+, and n = 1.3, ΔΔGbound-free = 1.4 kcal mole−1, Kb = 31 M−1, and α = 0.0016 for K+.

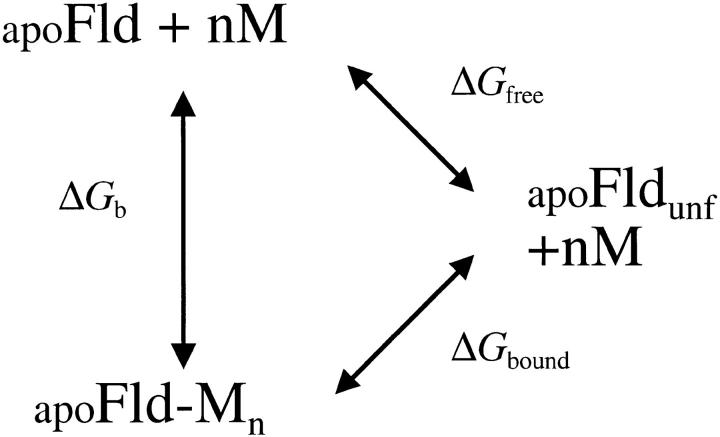

Because of the observed effect of cation binding on protein stability, as determined from urea denaturation curves saturates at high salt concentration (see below), the data were used to calculate some parameters of the cation-binding equilibrium with the model depicted in Scheme 1 ▶. In this model it was assumed that the conformational stability of apoflavodoxin (ΔGfree) is changed by cation binding to the new value of ΔGbound and that at any cation concentration the apparent stability is given by:

|

(1) |

where χfree and χbound are the molar fractions of the two species. We also assumed that n equivalent cations (M) can be bound simultaneously and that the increase in protein stability as a function of cation concentration (ΔΔG) follows equation 2:

|

(2) |

where Kb is the binding constant and ΔΔGbound-free is the difference in conformational stability between free and fully cation-loaded apoflavodoxin. Inspection of Figure 4b ▶ indicates that, in addition to the increase in stability at low ionic strength attributed to cation binding, a linear increase was also evident at higher ionic strengths. Not shown in the figure are data demonstrating that the linear increase in stability was still present at very high salt concentrations. The molecular origins of salt effects at these very high salt concentrations are not obvious, but they are probably related to general solvent effects. A similar linear dependence of pKa values of histidines on salt concentration was described recently (Kao et al. 2000). At low salt concentrations, those effects were interpreted as originating in the self-energy contribution to pKa values (i.e., they reflect a bias toward the charged species of the basic residue at high salt concentrations). Unable to account for the linear increase in stability at high salt concentrations with a physical model, a term (α[M]) was added to equation 2 (see equation 3) to account for it in the fits to the experimental data:

|

(3) |

The solid line in Figure 4b ▶ shows the fit of the experimental data to equation 3. The parameters that were resolved are n = 1.3, ΔΔGbound-free = 1.3 kcal mole−1 and Kb = 37 M−1 for Na+; and n = 1.3, ΔΔGbound-free = 1.4 kcal mole−1 and Kb = 31 M−1 for K+. Because the increase in protein stability derives from the strength of the complex, the calculated binding constant should report on the observed stability increase. For Na+ the calculated strength of the complex, in standard conditions, derived from the binding constants is ∼2.1 kcal mole−1 and for K+ it is ∼2.0 kcal mole−1. Considering the simplicity of the model, which, for example, disregards the possible ionic strength dependence of the binding constant or possible problems with use of the choline data as reference behavior meant to account for ionic strength effects proper, the fit is reasonably consistent and provides a simple phenomenological explanation of the observed cation-dependent effect: The binding of one-cation equivalents at low-affinity sites increases the stability of apoflavodoxin by ∼1.5 kcal mole−1.

Figure 9.

Scheme 1.

Identification of putative cation-binding sites

In recent years, a number of monovalent cation-binding sites in proteins have been described crystallographically (Di Cera et al. 1995). None are evident in the structure of apoflavodoxin; thus they were sought by analysis of surface electrostatic potentials. Electrostatic potential on the cation-accessible surface of apoflavodoxin was calculated as a function of pH and ionic strength with equation 11. This empirical function is useful to identify hot spots in the potential surface where the magnitude of the electrostatic potential is unusually high (or low). In the case of ion binding governed by coulombic interactions, these hot spots correspond to ion-binding sites (García-Moreno 1994, 1995,Kao et al. 2000). In earlier studies, this empirical function was used successfully to identify chloride-binding sites on the surface of myoglobin and hemoglobin (García-Moreno 1995; Kao et al. 2000). Identification of binding sites is easier for anions than for cation because strong interactions between proteins and anions such as chloride are governed by coulombic interactions. In contrast, it is not appropriate to treat cation binding strictly in terms of coulombic interactions because the energetics of binding are governed by the interplay between favorable coulombic interactions between ion and protein and by the energetically destabilizing dehydration of the cation and its ligands on binding. Accurate estimation of this energy remains a daunting challenge, as does quantitative representation of this energy on a surface representation of the cation-binding potential.

Four regions were identified on the Na+-accessible surface of apoflavodoxin where clusters of acidic residues result in large patches with large and negative electrostatic potential. The most prominent region includes contributions by Asp-90, Asp-144, Glu-145, and Asp-146. It is interesting to note that in the crystal there is an intermolecular contact between Glu-145 and Lys-3 of a neighboring molecule. This could result in a biased configuration of these carboxylic moieties, or it could also reflect the presence of a preconfigured cation-binding site that draws the lysine into a favorable contact. Another cation-binding site includes contributions from Glu-16, Glu-20, Asp-35, and Asp-65. A third site involves Glu-40, Asp-43, and Asp-46. The fourth site involves contributions from Glu-61 and Glu-67 with minor contributions from Asp-96, Asp-129, and Asp-100. These hot spots represent the regions in the protein where significant charge imbalance is present. The calculations are not particularly sensitive to the details of the structure. In fact, the magnitude and distribution of surface electrostatic potentials calculated on the surface of the apoflavodoxin structure (Genzor et al. 1996a) and in the structure of holo protein (Rao et al. 1992) are comparable. Although the magnitude of the surface electrostatic potential calculated with the empirical equation 11 and by the more rigorous finite difference solution of the Poisson-Boltzmann equation (Fig. 1 ▶) are significantly different, it is important to note that the distribution of potentials calculated by these two methods is very similar. The hot spots identified in maps calculated with one method are present in maps calculated with the other method.

The surface electrostatic potential of apoflavodoxin has several noteworthy features. At pH 7, negative electrostatic potentials are dominant throughout the surface of this protein (as shown in Fig. 1 ▶), consistent with its high content of acidic residues. The magnitude of the potential at the putative cation-binding sites calculated with equation 11 is not as large as in the binding sites that have been identified crystallographically, such as the Na+ site in thrombin (Di Cera et al. 1995) (data not shown). Overall, the calculations indicate that there are probably no discrete sites to which cations bind tightly, consistent with the data in Figure 4 ▶. Note also that the hot spots that were identified by examination of the electrostatic potentials involve contributions by residues that are neighbors in sequence. This supports the interpretation of the difference in the magnitude between the observed and the calculated salt dependence of stability at pH 7 in terms of a significant salt effect on the physical properties and on the Gibbs free energy of the denatured state of apoflavodoxin.

Energetics of site-specific cation binding

To understand the molecular origins of the cation-specific component of the stabilization of apoflavodoxin by salt, we estimated cation-binding affinities with structure-based calculations. In earlier studies it was shown that empirical calculations based on the Tanford-Kirkwood model capture quantitatively the phenomenological chloride-binding constants estimated from linkage analysis of the anion effect on the energetics of ligand binding and of tetramer assembly (García-Moreno 1995). The estimation of cation-binding constants is a considerably more difficult problem. In the case of cations, the binding energetics are governed by the interplay between favorable electrostatic interactions between the cation and its negatively charged ligands at the binding site and the unfavorable penalty of dehydration of both cation and the acidic ligands incurred concomitant with binding. The calculation of hydration energies of ions with continuum or with microscopic methods remains a formidable task, and the errors in such calculations are much larger than the net energy associated with the cation-specific effect in apoflavodoxin. Therefore, these calculations are only meant to provide a rough assessment of the origins of the peculiar salt dependence of stability of flavodoxin. We were initially encouraged by the observation that the effects of Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ on the stability of apoflavodoxin are quite similar. This similarity indicates that the direct interactions between these monovalent cations and apoflavodoxin do not necessarily involve dehydration of the cation, which would render the calculations tractable. However, to explain the similarity between the effects of monovalent and divalent cations it is necessary to invoke some dehydration of the latter resulting from closer interactions with the acidic ligands. In the calculations, the cations were treated as being fully hydrated and hydration energies were not included, as done previously in ion-binding calculations with the SATK method (Kao et al. 2000; Matthew et al. 1985).

According to the calculations, two cation-binding sites have higher affinity than the others. One of these consists of the Asp-90, Asp-144, Glu-145, and Asp-146 cluster; the other one involves Asp-35 and Asp-65. Binding at a third site defined by Glu-40, Asp-43, and Asp-46 was predicted to be weaker. The salt concentration at the point of half saturation of the stronger binding sites is ∼10 mM, whereas for the weaker binding sites it is closer to 80 mM. At a concentration of Na+ of 100 mM the electrostatic Gibbs free energy of interaction between Na+ and the protein is estimated at −1.7 kcal mole−1 for each of the tight sites and −0.9 kcal mole−1 for the weak site. Overall, these numbers are in reasonable agreement with the thermodynamic parameters (increase in protein stability and binding constant) resolved experimentally for the data in Figure 4b ▶.

Site-directed mutagenesis to dissect the origins of cation-specific effects

To distinguish between site-specific cation binding and binding of a more diffuse nature, site-directed mutagenesis of individual carboxyl groups, as well as more drastic deletions, were used to disrupt the constellation of charges in apoflavodoxin. The effects of 0.5 M choline and 0.5 M Na+ on the stability of the point mutants E67A, D144A, and E145A and of four shortened apoflavodoxins (1–149, 39–169, Δ[119–139], and Δ[120–139]) were measured by urea denaturation. The three point mutations were selected based on their predicted contribution to Na+ binding in the electrostatic calculations.

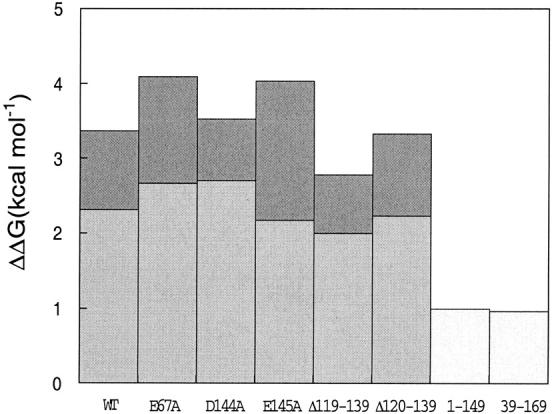

Figure 5 ▶ shows the increase in stability exerted by choline and Na+ on the mutant and variant flavodoxins. The three point mutants behave similarly to wild type: There is an ionic strength effect exerted by choline that increases the stability by ∼1 kcal mole−1 (for the less stable E145A mutant the effect is stronger) and then an additional and comparable Na+-stabilizing effect ranging from 2.2 to 2.7 kcal mole−1. Apparently none of the three point mutations alter the Na+ binding properties of apoflavodoxin significantly. The two deletion variants Δ(119–139) and Δ(120–139), which lack the loop splitting the β4 strand, are also very similar to wild type. This indicates that the amino acid residues in the 119–139 loop do not contribute to the putative Na+-binding regions.

Fig. 5.

Incremental stabilization of wild-type and mutant apoflavodoxin by choline chloride and sodium chloride. Light bars represent the specific increase in free energy of unfolding exerted by Na+ (relative to choline at the same concentration: 0.5 M). Dark bars represent the ionic strength-related increase in free energy of unfolding exerted by choline (at 0.5 M). The relative error of a difference between two energy values is of only 0.06 mole−1. For the apoflavodoxin fragments 1–149 and 39–169, the global effect of 0.5 M NaCl is presented.

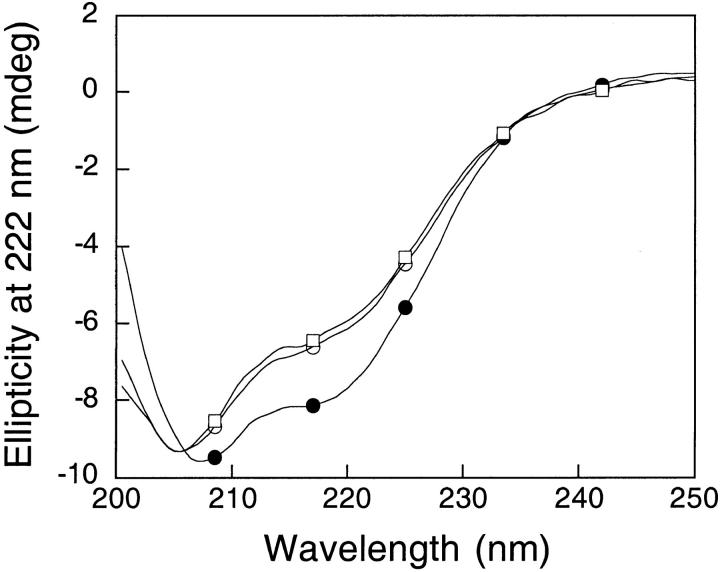

The mutants lacking the N- or C-terminal regions of apoflavodoxin (39–169 and 1–149, respectively) are insensitive to changes in ionic strength. For example, thermal denaturation of 1–149 (a two-state process; Maldonado et al. 1998) at low ionic strength occurs with a Tm of 37°C, and addition of 0.5 M choline does not change this temperature (Fig. 6 ▶). On the other hand, Na+ at 0.5 M raises the temperature of mid-denaturation from 37°C to 48°C, indicating that Na+ binds to the 1–149 fragment. Binding of Na+ to 1–149 is also indicated by the effect exerted on the far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectrum (Fig. 7 ▶). At low ionic strength, 1–149 is marginally stable (Maldonado et al. 1998) and its CD spectrum resembles a mixture of folded (with helical conformation) and unfolded protein. Addition of choline does not change the spectrum, but addition of 0.5 M Na+ clearly increases the helical content while the random coil content decreases (see also Maldonado et al. 1998).

Fig. 6.

Thermal denaturation of the shortened apoflavodoxin 1–149 at pH 7.0 in 5 mM sodium phosphate (open circles), plus 0.5 M choline chloride (open squares), plus 0.5 M NaCl (closed circles). A 2-μM protein concentration was used.

Fig. 7.

Far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectrum of the shortened apoflavodoxin 1–149 at pH 7.0 in 5 mM sodium phosphate (open circles), plus 0.5 M choline chloride (open squares), plus 0.5 M NaCl (closed circles). A 10-μM protein concentration in a 0.1-cm cuvette was used.

Effects of choline and Na+ on the thermostability of apoflavodoxin

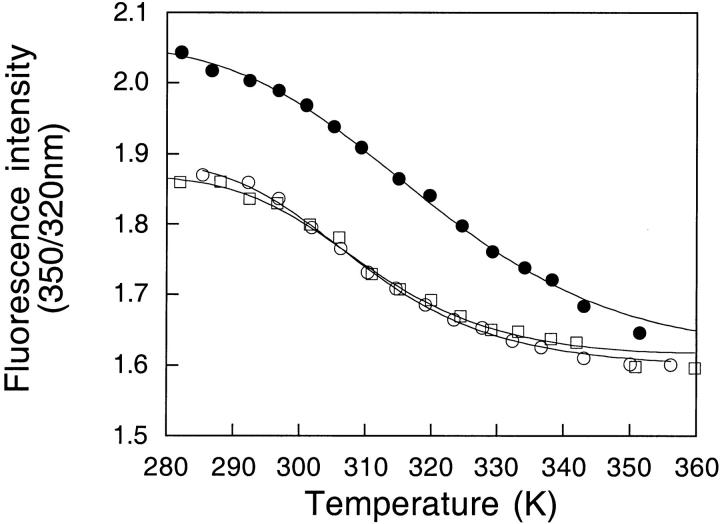

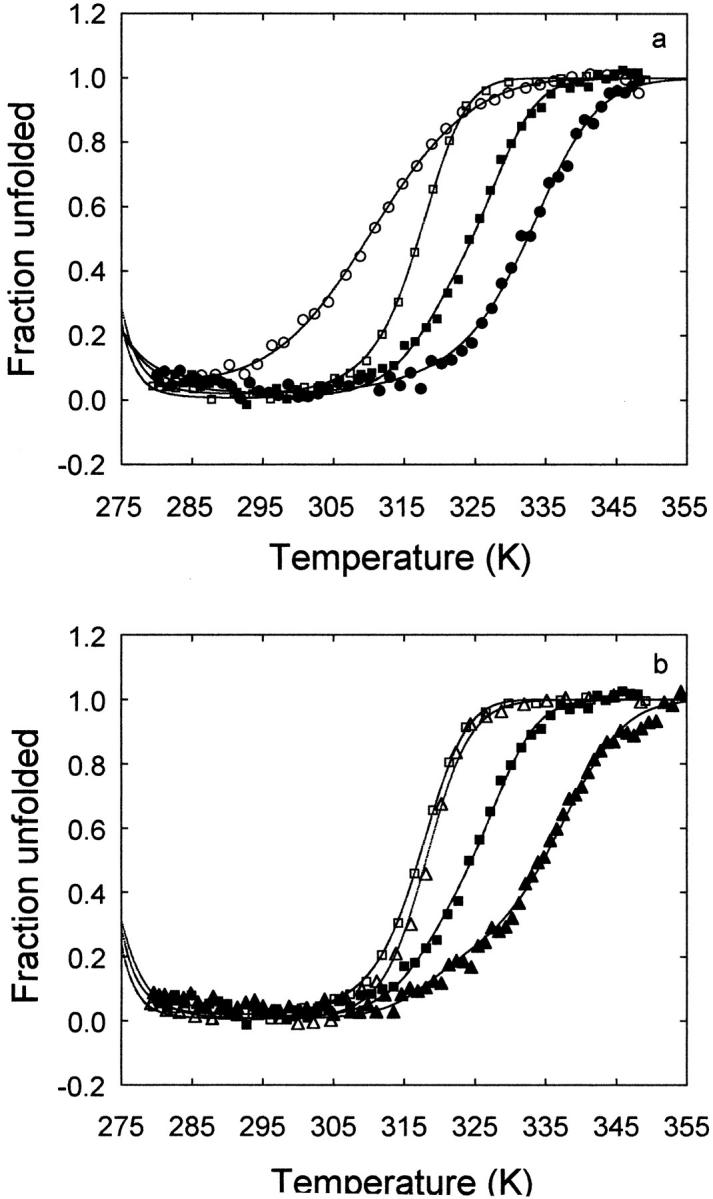

Unlike the equilibrium chemical denaturation of apoflavodoxin, which is two-state (Genzor el al. 1996b;Langdon et al. 2001), the thermal unfolding of apoflavodoxin is a fully reversible three-state process (Irún et al. 2001a,b). The influence of Na+ and choline on the thermal stability of wild-type apoflavodoxin was determined from thermal denaturation monitored by intrinsic fluorescence and far-UV CD (Fig. 8 ▶). As a first approximation, the fluorescence curve reflects the transformation of native protein into the intermediate and the CD curve the unfolding of the latter. Global analysis of the fluorescence and CD curves acquired under identical buffer conditions allows a precise calculation of the temperatures of mid-denaturation for the N-to-I and I-to-U unfolding equilibria (Table 2).

Fig. 8.

Thermal denaturation of wild-type apoflavodoxin as followed by fluorescence (open symbols) and far-UV CD (closed symbols) in 1 mM MOPS, pH 7.0 (circles); 1 mM MOPS, pH 7.0 plus 0.5 M choline chloride (squares); and 1 mM MOPS, pH 7.0 plus 0.5 M sodium chloride (triangles). Protein concentration was 2 μM.

Table 2.

Thermostability of the native and intermediate conformations of apoflavodoxin at pH 7.0, in different ionic strengths and cation concentration conditions

| Tma (°K) | ||

| Added salt (0.5 M) | N-to-1 equilibrium | I-to-U equilibrium |

| — | 310.5 ± 0.1 | 332.1 ± 0.1 |

| Chol Cl | 317.3 ± 0.1 | 327.6 ± 0.1 |

| NaCl | 318.9 ± 0.1 | 334.6 ± 0.4 |

a Calculated from global fits of fluorescence and far-UV CD (circular dichroism) thermal unfolding curves.

The influence of ionic strength on the two-equilibria can be assessed from a comparison of Tm at low ionic strength and in the presence of 0.5 M choline chloride (Fig. 8a ▶; Table 2). Choline raises the N-to-I Tm by 7°. This indicates that the electrostatic repulsions among acidic groups are reduced in the intermediate. Increasing the ionic strength, therefore, stabilizes preferentially the native state relative to the intermediate. In contrast, the influence of choline in the I-to-U Tm is the opposite (a decrease of 4.5°). This can be explained if the stabilizing contributions arising from interactions between positively and negatively charged groups observed in the native state are still present in the intermediate. Weakening of these interactions at high ionic strength destabilizes the intermediate relative to the unfolded state. Preferential attenuation of destabilizing electrostatic interactions in the U state would also explain the observed effect of choline on the I-to-U transition.

The influence of cation binding on the equilibria can be inferred by comparing the Tm at constant ionic strength with and without sodium (Fig. 8b ▶; Table 2). Sodium hardly changes the N-to-I Tm (1.5°). This indicates that it binds to the intermediate and native states with similar strength. As for the I-to-U Tm, sodium increases it by 7°, which reflects the preferential binding of the cation to the intermediate, compared with the unfolded state.

Discussion

The net contribution by electrostatic interactions to the conformational stability of proteins is usually stabilizing over a wide range of pH values, particularly in basic proteins such as myoglobin and hemoglobin (Matthew et al. 1985). The stability of most basic proteins is highest near neutral pH and decreases with decreasing pH. If the pKa values of surface ionizable residues were affected by the net charge of proteins, the dependence of stability on pH would be expected to be different for acidic and basic proteins (Linderstrøm-Lang 1924). The present study shows that highly acidic proteins such as apoflavodoxin, which have a substantial net negative charge at neutral pH, can also have net stabilizing electrostatic contributions to stability over a wide range of pH. In the case of flavodoxin, the pH dependence of stability increases dramatically with decreasing pH. Although it has been recently shown that in RNase Sa the pH of maximum stability need not correspond to its isoionic point (Shaw et al. 2001), the behavior of apoflavodoxin is likely to be common among highly acidic proteins. This behavior was captured quantitatively by the SATK calculations under conditions of very low ionic strength and without explicit consideration of contributions by cation binding. Recent reports (Kao et al. 2000; Loladze et al. 1999) have corroborated the suitability of these empirical algorithms for estimation of pKa values and other properties of surface ionizable residues (Matthew et al. 1985). The agreement between the measured and the predicted pH dependence of stability of apoflavodoxin is excellent. It validates the use of structure-based calculations to explore the structural origins of the measured energetics. Note that the calculated and the measured pH dependence of stability in Figure 2 ▶ are frame shifted along the ordinate by just 1 kcal mole−1. This indicates that at pH 7 the electrostatic contributions to stability are greater than the contributions by non-electrostatic effects.

The stability of most basic proteins decreases under conditions of increasing salt concentration near neutral pH (Matthew et al. 1985). This is usually interpreted in terms of screening of the net stabilizing electrostatic contributions to the native state, although a recent study suggests that the attenuation of electrostatic interactions need not be the dominant factor that determines the salt dependence of pKa values of surface residues (Kao et al. 2000). According to the structure-based calculations, in the case of apoflavodoxin the net effect of an increase in salt concentrations between 0 and 500 mM is to stabilize the native state. This unusual response to salt arises from the preferential screening of the large number of repulsive long-range coulombic interactions among the 31 acidic residues in this protein. This predicted dependence of stability on salt concentration was corroborated experimentally (Fig. 3 ▶), although the magnitude of the salt effect on stability measured in the presence of a bulky cation such as choline is considerably smaller than the calculated effect.

The stability increase measured in the presence of different salts at constant ionic strength was markedly different. Specifically, the effect of the choline salt of chloride is much lower than the effect measured in the presence of chloride salts of Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+. The choice of choline as a counterion was meant to probe the effects of the ionic strength on protein stability. Choline is a bulky cation; thus it was assumed that it cannot bind or establish direct contact with the acidic residues on the surface of apoflavodoxin. The fact that the other salts, chiefly NaCl and KCl, exert a much stronger stabilizing effect than choline at low ionic strength (Fig. 4a ▶) indicates that these smaller cations can interact more favorably and perhaps more directly with the protein. This would increase the stability of the native state relative to the denatured state, in which binding is less likely attributable to the lower local density of acidic moieties. In an attempt to estimate the contribution by cation binding to the stability of such complexes, the salt effect measured in the presence of choline was subtracted from the effect measured in the presence of other cationic species (Fig. 4b ▶). This is only valid if the component of the salt dependence of stability that is related to the ionic strength effect follows strictly the behavior described originally by Debye and Hückel, proportional to the concentration and to the valence of the component ions. The simplest possible binding model was used to fit the data corrected for the ionic strength effect. The fit indicates that the cation-specific effect can be captured phenomenologically by invoking the binding of a single cation. The calculated increase in protein stability on cation binding according to the fit is 1.3 and 1.4 kcal mole−1 for Na+ and K+, respectively. These energies are consistent with the calculated value of the complex binding energy (2.0 and 2.1 kcal mole−1 for Na+ and K+, respectively) and also with the affinity of cation-binding sites estimated from structure-based calculations.

Not many monovalent cation-binding sites have been found in proteins. The Na+ site in thrombin, for example, is rich in negatively charged residues as well as in polar atoms (Di Cera et al. 1995). In the absence of direct, structural information on the location and nature of the putative cation-binding sites, we sought to determine the most likely regions of binding by examination of surface electrostatic potentials. Identification of the putative binding sites of monovalent cations in proteins is extremely difficult because of the difficulty in quantitating the self-energies of ions in chemically nonhomogeneous environments. The search of cation-binding sites involved the simplest approach possible, consisting of locating hot spots on the electrostatic surface potential. The electrostatic potentials mapped onto the molecular surfaces calculated with ionic and hydrated radii of sodium ions were analyzed. The dominant hot spots on the surface accessible to ionic Na+ were also the dominant hot spots on the surface accessible to hydrated Na+. Furthermore, we showed that the identity of the hot spots is independent of the method used to estimate electrostatic potentials. Specifically, the distributions of potentials calculated with the empirical equation 11 and with the more sophisticated methods embodied by algorithms such as GRASP or DELPHI are equivalent because the spatial distribution of charges governs the shape of the potential.

Two regions on the surface of apoflavodoxin have large negative electrostatic potentials. These regions are likely to attract high concentrations of cations. It is important to emphasize that these hot spots are quite large: They are not sharply defined discrete binding sites. The difference in the effects of choline and the small cations indicates that direct, chemical interactions between the small cations and apoflavodoxin are present that cannot be established with choline, presumably because of its greater size and bulkiness. On the other hand, the overall similarity in the effects exerted by Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ indicates that there is minimal disruption of the innermost hydration shell around the cations, and that inner sphere complexes between the cations and the acidic ligands are unlikely. Thus in the calculations of binding affinities based on electrostatic considerations, the cations were treated as fully hydrated cations and the energetics of dehydration were ignored. Under the simple assumption that the cation-binding affinity is determined by the magnitude of the electrostatic potential, the calculations showed that cations could bind at either one of the two largest patches of high negative electrostatic potential with binding affinities comparable to the ones that were measured experimentally.

To test if the predicted regions of cation binding were responsible for the observed salt effects, the salt dependence of stability was measured for point mutants in which some of the acidic residues predicted to play substantial roles in stabilizing cations were modified to uncharged residues. The behavior of mutants and of the wild-type apoflavodoxin was nearly identical (Fig. 5 ▶). This argues that cation binding to apoflavodoxin is not site-specific and that the weak interactions between cations and the protein are diffuse and probably distributed over many weak binding sites. This is the expected nature of cation-protein interactions when the cations do not shed their innermost waters on binding.

In another attempt to identify the regions of the protein where cations might bind, we analyzed the choline and sodium effects on the stability of several shortened apoflavodoxins obtained by either site-specific cleavage or mutagenesis. The flavodoxin variants lacking a long loop (119–139) that splits the β5 strand (S. Maldonado, A. Lostao, and J. Sancho, unpubl.) behave like wild type (Fig. 5 ▶). The residues in this loop are therefore not the source of the specific salt effect. The apoflavodoxin variant lacking the C-terminal long helix, 1–149 (Maldonado et al. 1998) can be stabilized effectively by Na+. Choline, however, has little effect, as evidenced by its inability to induce secondary structure (Fig. 7 ▶) and by the fact that the Tm of the 1–149 fragment is unaltered by 0.5 M choline (Fig. 6 ▶). Na+ has an effect on 1–149, but it is smaller than the effect exerted on the entire protein. There are very few clustered acidic residues in the C-terminal segment absent in 1–149 fragment. Therefore, it is likely that the difference in the response to salt of wild type and of the 1–149 fragment reflects a change in the conformation and dynamic properties of the fragment (a monomeric, cooperatively stabilized molten globule; Maldonado et al. 1998), as indicated by its spectroscopic properties. This could lead to distortion of the cation-binding regions such that a lower affinity and, hence, a lower Na+ stabilizing effect would be observed. A clear indication of Na+ binding to 1–149 comes from the strengthening of its far-UV signal with Na+ (Fig. 7 ▶). As for the lack of a choline effect in 1–149, it indicates that the unfavorable electrostatic interactions that can be screened by ionic strength are not present in the 1–149 molten globule fragment.

The effects of Na+ and choline on the apoflavodoxin variant lacking the N-terminal region (39–169; S. Maldonado and J. Sancho, unpubl.) were also studied. This apoflavodoxin fragment is moderately stabilized by choline (data not shown) and it is also stabilized by Na+ (Fig. 5 ▶), although the effect of Na+ is less than for the intact protein. The low Na+ effect on this fragment is not surprising considering that this fragment is also partly unstructured (S. Maldonado and J. Sancho, unpubl.). The ability of Na+ to stabilize this fragment indicates that the regions responsible for the cation-specific effect are still present in this fragment. There are several carboxyl groups in the 1–38 fragment, but most are in electrostatically favorable environments. For example, Glu-20, Asp-24, and Asp-29 interact with Arg-23; and Glu-25 interacts with both Lys-157 and Lys-165. In fact, Glu-16 and Asp-35 are the only two carboxylic groups in the N terminal 1–38 fragment that might give rise to destabilizing electrostatic interactions. Overall, the mutational analyses indicate that a significant number of the residues responsible for the cation-specific effect in apoflavodoxin are located in the central half of the protein (40–120).

Little is known about the determinants of stability of folding intermediates. Apoflavodoxin populates an equilibrium thermal intermediate that is being used to analyze the energetics of these protein conformations (Irún et al. 2001a,b). By performing a three-state global fitting of fluorescence and far-UV CD thermal unfolding curves at low ionic strength and in the presence of 0.5 M choline chloride or sodium chloride, we have investigated the effects of the ionic strength and cation binding on the equilibrium intermediate. Our data indicate that the thermal intermediate is less destabilized than the native state by internal electrostatic repulsions arising from its many acidic residues. This could reflect that, in the intermediate, some of the more electrostatically destabilizing regions are unfolded or simply that the intermediate is more loosely structured and therefore more likely to resolve repulsive electrostatic interactions through conformational changes. The stabilizing charge/charge interactions deemed responsible for the net electrostatic contribution to the stability of the native state at 25°C appear to be present in the intermediate because increasing the ionic strength lowers the Gibbs free energy of the intermediate. It is also noticeable that the intermediate is significantly stabilized by cation binding. Both the persistence of the favorable charge/charge interactions and cation binding in the intermediate are consistent with a previous mutational analysis (Irún et al. 2001a) that indicated most native apoflavodoxin surface hydrogen bonds were still present in this high temperature intermediate conformation, which in turn indicates that it displays a fairly native-like topology.

Finally, it is interesting to draw a parallel between the effects of salt on the stability of apoflavodoxin at neutral pH and the effects of salts on acid-unfolded proteins at very low pH. Acid-unfolded proteins have a large, net positive charge. They can be refolded very effectively under conditions of high salt concentration (Goto et al. 1990). Folding is usually achieved in chloride concentrations between 50 mM and 100 mM. The salt effect is anion-specific, and anions such as perchlorate, sulfate, and thiocyanates are much more effective than chloride in inducing refolding. When ranked according to the efficacy with which they can refold acid-denatured proteins, the anions follow the series that describes their ability to interact with ligands of the opposite polarity. This indicates that there are specific interactions between proteins and anions. Furthermore, with some of the anions, the effect is achieved at very low concentrations; thus the salt-induced refolding of acid-denatured proteins cannot be ascribed to the ionic strength. On the other hand, attempts to localize the effect to a particular set of residues or show that anion binding is site-specific have failed. In the case of both the acid-denatured proteins and flavodoxin at neutral pH, it is likely that many ions interact weakly with several diffuse ion-binding sites that are present in the native state but not in the unfolded protein. Thus the equilibrium between native and unfolded states shifts in favor of the native state under conditions of high salt. This delocalization of the ion-binding potential does not mean direct interactions between ligands and ions are not established, but it does imply these interactions are weak and therefore difficult to isolate and to estimate with structure-based energy calculations. The discrepancies between calculated and measured salt dependence of stability of flavodoxin underscore the difficulties in capturing salt-specific effects in proteins and the need for improved computational methods for structure-based calculation of electrostatic energy.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

Protein expression and purification of wild-type and mutant flavodoxins were performed as described earlier (Fillat et al. 1991; Genzor et al. 1996b). Apoflavodoxin was prepared from the holoflavodoxin (Edmondson and Tollin 1971) and its concentration was determined as previously described (Genzor et al. 1996b).

Mutagenesis and purification of apoflavodoxin variants

Mutagenesis of the wild-type gene was performed as described (Genzor et al. 1996b). The following mutants were used in this study: E67A, D144A, and E145A. In addition, shortened apoflavodoxins (1–149, 39–169, Δ[119–139], and Δ[120–139]) were prepared either by cleavage of flavodoxin mutants containing a S149M (Maldonado et al. 1998) or a Q38M (S. Maldonado and J. Sancho, unpubl.) mutation or directly by site-directed mutational deletion of an internal apoflavodoxin region (A. Lostao, S. Maldonado, and J. Sancho, unpubl.).

CD spectra

CD spectra in the far-UV were recorded in a Jasco 710 spectropolarimeter at 25 ± 2°C using a 0.1-cm cuvette and a 10-μM protein concentration.

Urea denaturation

Unfolding of wild-type, mutant, and shortened apoflavodoxins as a function of urea concentration was monitored by intrinsic fluorescence (emission at 320 with excitation at 280 nm) at 25 ± 0.1°C in a Kontron SMF 25 fluorimeter, using a protein concentration of 2 μM. Under these conditions the unfolding is reversible and protein concentration independent (Genzor et al. 1996b; Maldonado et al. 1998). Single experiments at different buffer conditions were performed. The buffer was 1 mM MOPS pH 7.0, modified as required by addition of salt. To study the pH dependence of stability, the following buffers were used at a constant ionic strength of 10 mM: MES (5.6–6.6), MOPS (pH 6.6–8.1), and CHES (pH 8.1–9.6). The data were analyzed assuming a two-state equilibrium, a linear relationship between free energy and urea concentration, and a linear dependence of native and denatured state fluorescence on urea concentration using the following equation:

|

(4) |

where F is the observed fluorescence emission, FF and mF the emission of the folded state and its urea dependence, FU and mU the emission of the unfolded state and its urea dependence, ΔGw the Gibbs energy difference between the folded and unfolded states in the absence of denaturant, D the concentration of denaturant (urea), and m the slope of the linear plot of ΔG versus D (Pace et al. 1989; Santoro and Bolen 1988). Because no systematic deviations in m values in different buffer conditions were observed, an averaged m value of 2.25 kcal mole−1M−1 was used to calculate the reported free energies from the urea concentrations of mid-denaturation. For the stability curves of apoflavodoxin fragments of low stability, the mF D term of equation 4 has been omitted.

Thermal denaturation

Thermal unfolding curves of apoflavodoxin at low ionic strength (1 mM MOPS, pH 7.0) and with either 0.5 M NaCl or 0.5 M choline chloride were monitored by fluorescence (emission at 320; excitation at 280 nm) and by far-UV CD (222 nm), using a 2-μM protein concentration. No protein concentration effects in Tm are observed in this concentration range and the unfolding is reversible (Irún et al. 2001b). Single experiments at different buffer conditions were performed. The temperature was increased at ∼1°C/min in a sealed cuvette. Global fitting of the two thermal unfolding curves (fluorescence and far-UV CD) at each buffer condition to a three-state model involving native (N), intermediate (I), and unfolded (U) conformations was performed with the program MLAB (Civilized Software). The approach was that of Luo et al. (1995). Each thermal denaturation curve was preliminary-fitted to the equation for a two-state equilibrium:

|

(5) |

where S is the spectroscopic signal, SF and SU the signals for the folded and unfolded states, Tm is the transition temperature, and ΔH and ΔCp are the enthalpy and specific heat of denaturation at Tm, respectively (Pace et al, 1989). The data were then converted to apparent fractions of unfolded protein, Fapp, using equation 6:

|

(6) |

where Y is the observed signal, and YU and YN are the optical signals for unfolded and native protein, respectively. Fapp is related to the fractional populations of the intermediate and unfolded states (FI and FU) by equation 7:

|

(7) |

where Z is a constant that describes the spectroscopic resemblance of the I state to the U state. From the relationship between fractional populations and equilibrium constants, Fapp can be calculated using equation 8:

|

(8) |

where:

|

(9) |

|

(10) |

In each fitting, all thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔCp, and Tm) were globally constrained, whereas the Z values were allowed to vary among the different spectroscopic techniques.

Structure-based calculation of electrostatic contributions to stability

The crystallographic structure (accession code 1ftg) of apoflavodoxin (Genzor et al. 1996a) was used to calculate the electrostatic Gibbs free energy as a function of pH and ionic strength with the empirical SATK algorithm, described previously (Matthew et al. 1985). In the present calculations the protein interior was treated with a dielectric constant of 4 and the depth of charge burial was fixed at 0, as is customary in these calculations. For these reasons the lowest dielectric constant sampled by any pair of interacting charged atoms was 41. It is well understood that the success of the SATK algorithm in reproducing the ionization energetics of surface groups stems from the use of high effective dielectric constants in the calculation of electrostatic energies of interaction between pairs of charges.

The identification of putative cation-binding sites at the surface of apoflavodoxin involved calculation of the electrostatic potentials (ψel) on the cation-accessible surface with equation 11:

|

(11) |

In this expression rkj is the distance in Å between point k on the protein surface and the jth charge. SAj refers to the normalized solvent accessibility of a charged atom, calculated with a probe radius of 1.4 Å. Zj is the pH-dependent fractional charge of each titratable site. The effective dielectric constants (Deff) were obtained from the electrostatic work terms calculated as a function of ionic strength with the Tanford-Kirkwood algorithm, as described previously (García-Moreno 1994). The values of ψel calculated with equation 11 are salt- and pH-dependent because the fractional charge of each ionizable residue (Zj) is a function of these variables. Only contributions from ionizable groups to the surface electrostatic potential are included in the calculation of ψel,k. The properties and limitations of this empirical function have been described previously (García-Moreno 1994, 1995; Kao et al. 2000).

Calculations of the energetics of cation binding were performed as described previously in a study of anion binding to hemoglobin (García-Moreno 1995) and in myoglobin (Kao et al. 2000). The notion that ion-binding sites can be identified as extrema on the surface electrostatic potentials is valid in the case of anions because anions are only weakly hydrated and their site-specific binding interactions with proteins are governed by Coulombic effects (Collins 1997). Cations, however, interact strongly with water, and it is not entirely appropriate to locate cation-binding sites with potential energy functions that fail to consider explicitly the energetic penalty associated with the dehydration of cations and of their acidic ligands when they interact in a partially dehydrated state. Hydration energies are ignored completely in the present calculations because of the inability to capture them quantitatively with this or any other algorithm. However, the calculations are meaningful because the experimental data indicate that in the case of apoflavodoxin, cation-protein interactions proceed without any significant dehydration of the cations. For this reason, the sites of putative cation binding that were used in the calculations were identified as maxima or minima in the magnitude of ψel at the ion-accessible surface calculated with the radius of hydrated cations instead of the ionic radius.

Surface electrostatic potentials were also calculated by finite difference solution of the Poisson-Boltzmann equation as embodied in the GRASP software (Nicholls et al. 1991). The magnitude of the potentials calculated with the GRASP program and with the empirical function in equation 11 are different; the magnitude of the potentials calculated with GRASP is always higher. However, the distribution of maxima and minima throughout the protein calculated by the two methods is similar because this is governed by the geometric arrangement of the charged atoms on the surface of the protein and not by the specific treatment of ionic and dielectric effects inherent in the different algorithms.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by grants CRG 940230 (NATO), PB97–1027 (DGES), BMC2001–2522 (MCYT), P15/97 (DGA), P120/2001 (DGA), and MCB-9600991 (National Science Foundation) and by fellowships from Gobierno Vasco (S.M.), Diputación General de Aragón (AG), Gobierno español (M.P.I., L.A.C.), and Programa Intercampus (A.L.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.2980102.

References

- Antosiewicz, J., McCammon, J.A., and Gilson, M.K. 1994. Prediction of pH-dependent properties of proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 238 415–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1996. The determinants of pKas in proteins. Biochemistry 35 7819–7833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, K. 1997. Charge density-dependent strength of hydration and biological structure. Biophys. J. 35 7819–7833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cera, E., Guinto, E.R., Vindigni, A., Dang, Q.D., Ayala, Y.M., Wuyi, M., and Tulinsky, A. 1995. The Na+ binding site of thrombin. J. Biol. Chem. 270 22089–22092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, D.E. and Tollin, G. 1971. Chemical and physical characterization of the Shethna flavoprotein and apoprotein and kinetics and thermodynamics of flavin analog binding to the apoprotein. Biochemistry 10 124–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Recio, J., Romero, A., and Sancho, J. 1999. Energetics of a hydrogen bond (charged and neutral) and of a cation-π interaction in apoflavodoxin. J. Mol. Biol. 290 319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillat, M.F., Borrias, W.E., and Weisbeerk, P.J. 1991. Isolation and overexpression in Escherichia coli of the flavodoxin gene from Anabæna PCC 7119. Biochem. J. 280 187–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, W.R. and Robertson, A.D. 2000. Insensitivity of perturbed carboxyl pKa values in the ovomucoid third domain to charge replacement at a neighboring residue. Biochemistry 39 8067–8072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno, E.B. 1994. Estimating binding constants for site-specific interactions between monovalent ions and proteins. Methods Enzymol. 240 645–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1995. Probing structural and physical basis of protein energetics linked to protons and salt. Methods Enzymol. 259 512–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genzor, C.G., Perales-Alcón, A., Sancho, J., and Romero, A. 1996a. Closure of a tyrosine/tryptophane aromatic gate leads to a compact fold in apoflavodoxin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genzor, C.G., Beldarraín, A., Gómez-Moreno, C., López-Lacomba, J.L., Cortijo, M., and Sancho, J. 1996b. Conformational stability of apoflavodoxin. Protein Sci. 5 1376–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto, Y., Calciano, L.J., and Fink, A.L. 1990. Acid-induced folding of proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 87 573–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsley, G.R., Shaw, K.L., Fee, L.R., Alston, R.W., Huyghues-Despointes, B.M., Thurlkill, R.L., Scholtz, J.M., and Pace, C.N. 1999. Increasing protein stability by altering long-range coulombic interactions. Protein Sci. 8 1843–1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex, N. and Peitsch, M.C. 1997. Swiss-Model and the swiss-pdbviewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18 2714–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irún, M.P., Maldonado, S., and Sancho, J. 2001a. Stabilisation of apoflavodoxin by replacing hydrogen-bonded charged Asp or Glu residues by the neutral isosteric Asn or Gln. Protein Eng. 14 173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irún, M.P., García-Mira, M.M., Sánchez-Ruiz, J.M., and Sancho, J. 2001b. Native hydrogen bonds in a molten globule: The apoflavodoxin thermal intermediate. J. Mol. Biol. 306 877–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao, Y.H., Fitch, C.A., Bhattacharya, S., Sarkisian, C.J., Lecomte, J.T., and García-Moreno, E.B. 2000. Salt effects on ionization equilibria of histidines in myoglobin. Biophys. J. 79 1637–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langdon, G.M., Jiménez, M.A., Genzor, C.G., Maldonado, S., Sancho, J., and Rico, M. 2001. Anabaena apoflavodoxin hydrogen exchange: On the stable exchange core of the α/β(21345) flavodoxin-like family. Proteins 43 476–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linderstrøm-Lang, K. 1924. On the ionization of proteins. C.R. Trav. Lab Carlsberg. 15 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Loladze, V.V., Ibarra-Molero, B., Sanchez-Ruiz, J.M., and Makhatadze, G.I. 1999. Engineering a thermostable protein via optimization of charge-charge interactions on the protein surface. Biochemistry 38 16419–16423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenthal, R., Sancho, J., Reinikainen, T., and Fersht, A.R. 1993. Long-range surface-charge interactions in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 232 574–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, M.L and Luschinsky, C.L. 1992. Structure and redox properties of Clostridial flavodoxin. In Chemistry and biochemistry of flavoenzymes (ed. F. Müller), Vol. III, pp 427–466. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida.

- Luo, J., Iwakura, M., and Matthews, C.R. 1995. Detection of a stable intermediate in the thermal unfolding of a cysteine-free form of dihydrofolate reductase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 34 10669–10675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado, S., Jiménez, M.A., Langdon, G.M., and Sancho, J. 1998. Cooperative stabilization of a molten globule apoflavodoxin fragment. Biochemistry 37 10589–10596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthew J.B., Gurd F.R., García-Moreno B., Flanagan M.A., March K.L., and Shire S.J. 1985. pH-dependent processes in proteins. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 18 91–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew, S.G. and Tollin, G. 1992. General properties of flavodoxins. In Chemistry and biochemistry of flavoenzymes (ed. F. Müller), Vol. III, pp 389–426. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida.

- Meeker, A.K., García-Moreno, B., and Shortle, D. 1996. Contributions of the ionizable amino acids to the stability of staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry 35 26443–26449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, A.J., Bharadwaj, R., and Honing, B. 1991. GRASP, a graphical representation and analysis of surface properties. Biophys. J. 239 423–433. [Google Scholar]

- Pace C.N., Shirley B.A., and Thomson, J.A. 1989. Measuring the conformational stability of a protein. In Protein structure: A practical approach (ed. T.E. Creighton), pp 311–330. IRL Press, Oxford, England.

- Rao, S.T., Shaffie, F., Yu, C., Satyshur, K.A., Stockman, B.J., Markley, J.L., and Sundaralingam, M. 1992. Structure of the oxidized long-chain flavodoxin from anabaena 7210 at 2 A resolution. Protein Sci. 1 1413–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, L.J. 1987. Ferredoxins, flavodoxins and related proteins: Structure, function and evolution. In The cyanobacterium (eds. P. Fay and c. Van Baalen), pp 35–67. Elsevier Science Publishers, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

- Santoro, M.M. and Bolen, D.W. 1988. Unfolding free-energy changes determined by the linear extrapolation method. 1. Unfolding of phenylmethanesulfonyl alpha-chymotrypsin using different denaturants. Biochemistry 27 8063–8068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, K.L., Grimsley, G.R., Yakovlev, G.I., Makarov, A.A., and Pace, C.N. 2001. The effect of net charge on the solubility, activity, and stability of ribonuclase Sa. Protein Sci. 10 1206–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector, S., Wang, M., Carp, S.A., Robblee, J., Hendsch, Z.S., Fairman, R., Tidor, B., and Raleigh, D.P. 2000. Rational modification of protein stability by the mutation of charged surface residues. Biochemistry 39 872–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitten, S.T. and García-Moreno, E.B. 2000. pH dependence of stability of staphylococcal nuclease: Evidence of substantial electrostatic interactions in the denatured state. Biochemistry 39 14292–14304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]