Abstract

The replication fork blocks are common in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. In most cases, these blocks are associated with increased levels of mitotic recombination. One of the best-characterized replication fork blocks in eukaryotes is found in ribosomal DNA (rDNA) repeats of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. It has been shown that the replication fork blocking protein Fob1p regulates the recombination rate and the number of rDNA copies in S. cerevisiae, but the mechanistic aspects of these events are still poorly understood. Sequence profile searches revealed that Fob1p is related to retroviral integrases. Subsequently, the catalytic domain of HIV-1 integrase was used as a template to build a reliable three-dimensional model of Fob1p. Structural insights from this study may be useful in explaining Fob1p-mediated formation of extrachromosomal rDNA circles that accelerate aging in yeast and recombination events that lead to expansion or contraction of rDNA.

Keywords: Fob1p, HOT1, rDNA maintenance, DNA recombination, aging in yeast

The replication fork block (RFB) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae occurs in a nontranscribed part of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) tandem repeats and causes the accumulation of branched intermediates in two-dimensional agarose gels (Brewer and Fangman 1988). The RFB ensures unidirectional replication in rDNA that matches the direction of 35S rRNA transcription and persists even when rDNA is cloned into a plasmid (Brewer et al. 1992). The rDNA also contains a DNA sequence element termed HOT1, which is responsible for mitotic recombinational hot-spot activity and overlaps with the RFB site (Keil and Roeder 1984; Voelkel-Meiman et al. 1987). More recently, a gene (FOB1) was isolated whose product (Fob1p) was necessary for both RFB and HOT1 activities (Kobayashi and Horiuchi 1996). Subsequent studies from the same group identified Fob1p as a major regulator of the rDNA copy number (Kobayashi et al. 1998). Finally, it was shown that Fob1p has nuclear localization (Defossez et al. 1999) and influences the aging process in yeast by controlling the abundance of extrachromosomal rDNA circles (ERCs).

Despite the wealth of data linking Fob1p to several important cellular functions that seem to require DNA recombination, the mechanism of its action is still unclear (Defossez et al. 1999; Kobayashi et al. 1998). Using sequence profile analysis, I show that Fob1p has distant, yet statistically significant, sequence similarity to retroviral integrases. This relationship was confirmed when a good three-dimensional (3-D) model of Fob1p was built using the catalytic core domain of HIV-1 integrase as template. The functional implications of this finding are discussed in the context of available experimental data.

Results

The function of an unknown protein traditionally is inferred from its similarity to proteins of known functions. In the case of Fob1p, a BLAST search (Altschul et al. 1997) of the protein database initially did not identify any matches above statistically significant expectation (E) values. The improved version of PSI-BLAST (Schaffer et al. 2001) detected a significant match (E = 0.002) with the functionally uncharacterized human protein (gi|17478564) containing an integrase core domain. When this protein was used as a query with the inclusion threshold of 0.001, Fob1p was identified after the first iteration (E = 3×10−4) in addition to many other integrase-like proteins. An independent search of the PFAM database (Bateman et al. 2000) also produced a significant match to the integrase core domain (PF00665; E = 0.0051). The zinc finger-like domain of integrases, which is represented as a separate entity in PFAM, was not among significant matches in this search (PF02022; E = 2). However, when compared with a custom-built, hidden Markov model (Eddy 1998) of integrases that included both zinc finger-like and catalytic domains, Fob1p had a highly significant score (E < 10−12).

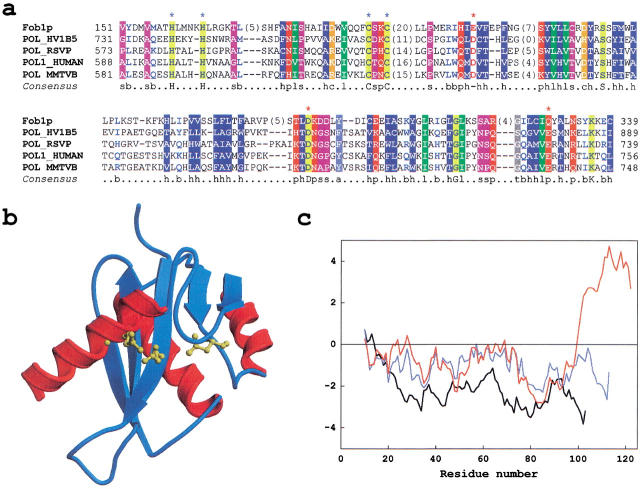

Retroviral integrases belong to a functionally diverse superfamily of polynucleotide transferases whose structurally characterized members include HIV-1 integrase (Dyda et al. 1994), RNase H (Katayanagi et al. 1990), Mu transposase (Rice and Mizuuchi 1995) and Holliday junction resolvase RuvC (Ariyoshi et al. 1994). These enzymes use a divalent metal ion to cut polynucleotides via a common catalytic mechanism; integrases and transposases also use the newly formed 3` hydroxyl group to catalyze a DNA strand-transfer reaction. Retroviral integrases have three distinct functional domains: (i) the N-terminal domain similar to helix-turn-helix proteins that binds zinc and mediates dimerization; (ii) the catalytic core domain with conserved carboxylic residues D,D(35)E coordinating metal ions needed for the catalysis; (iii) the C-terminal domain that nonspecifically binds DNA (Andrake and Skalka 1996; Craigie 2001). The first two domains (Wang et al. 2001) are highly conserved among retroviral and retrotransposon integrases, and related domains are easily recognizable in Fob1p after its alignment with several known retroviral integrases (Fig. 1a ▶).

Fig. 1.

(a) Multiple sequence alignment of Fob1p with known retroviral integrases. Amino-acid residues belonging to the HHCC motif of integrases are marked by blue asterisks above the alignment; carboxylate residues forming the catalytic triad are marked with red asterisks. Numbers at the beginning and the end indicate the sequence parts that were aligned; numbers in parentheses indicate how many residues were omitted, either to make the alignment more compact or because they cannot be aligned reliably. Shading of residues was based on their physicochemical properties. The meaning of letters on the consensus line is as follows: s, small residues (ACDGNPSTV); b, big (EFHIKLMQRWY); h, hydrophobic (ACFGHILMTVWY); p, polar (CDEHKNQRST); l, aliphatic (ILV); c, charged (DEHKR); −, negatively charged (DE); t, tiny (ACGST). Individual residues conserved across the whole alignment are shaded in yellow and shown as capital letters on the consensus line. (b) Structural model confirms similarity of Fob1p to retroviral integrases. The catalytic core of HIV-1 integrase (PDB code 1c0m) was used as a template to build a model of Fob1p (residues 217–339). In the structural alignment, Fob1p shares ∼13% sequence identity with the template. Fob1p residues corresponding to the integrase catalytic site are shown in ball-and-stick representation and are colored yellow. Comparative modeling was done using MODELLER (Sanchez and Sali 1998), and the structure was rendered with MOLSCRIPT (Kraulis 1991) and Raster3D (Merritt and Bacon 1997). (c) Evaluation of 3-D models of Fob1p. The catalytic core of HIV-1 integrase (PDB code 1c0m) and 3-D models of Fob1p were evaluated using the energy function derived from high-resolution crystal structures of many unrelated proteins (Sippl 1993). As expected for structures of good quality, the template (black line) and the correct model (blue line) have average energy profiles smaller than zero over most of their lengths. The model based on incorrect alignment shows higher energy compared to reliable structures (red line). Energy profiles are not superimposable because of insertions and deletions.

Even though the sequence similarity described above indicates that Fob1p and integrases have comparable folds, it is hard to establish their functional relatedness unambiguously. To that end, the credibility of sequence-based prediction was tested by building a 3-D model of Fob1p using the catalytic core domain of HIV-1 integrase (Goldgur et al. 1998). Because the low sequence identity between Fob1p and integrases makes the reliable alignment very difficult, an iterative procedure of model building and evaluation was employed (Guenther et al. 1997). Briefly, the alignment from Figure 1a ▶ was used to produce a model by satisfying spatial restraints (Sali and Blundell 1993), and the model was subsequently evaluated using an empirically derived energy function (Sippl 1993). Parts of the protein with unsatisfactory energy were realigned to the template and the whole process of model building and evaluation was repeated until most of the average energy profile was below zero (blue line in Fig. 1c ▶). The final model was optimized by adjusting the conformation of side chains to minimize steric clashes (Fig. 1b ▶). Applying the procedure developed for large-scale comparative modeling of proteins (Sanchez and Sali 1998), one can calculate the probability (pG) that estimates the quality of protein models. Extensive jack-knife testing has shown that models having pG>0.5 are in the "good" class and have at least partially correct fold (Sanchez and Sali 1998). According to this criterion, the model shown in Figure 1b ▶ is very reliable (pG = 0.91). However, in this model, the residues E-D-Q align with the catalytic triad of D-D-E residues (Fig. 1a ▶). This carboxylate triad is one of the most conserved features of polynucleotide transferases (Dyda et al. 1994; Rice and Mizuuchi 1995) and mutants with E->Q substitution in the last carboxylate residue were shown to be inactive (Baker and Luo 1994; Engelman and Craigie 1992). To explore the possibility that the last catalytic residue was misaligned, I made an alternative alignment (not shown) that matched E-D-E with conserved D-D-E residues. The model produced from this alignment, though quite similar in the overall topology, was not reliable (pG = 0.31; red line in Fig. 1c ▶). While this result could be the flaw of the model building and/or evaluation procedure, it indirectly suggests that Fob1p has a different arrangement of catalytic residues in its active site. This proposal is in line with the comparative analyses of polynucleotide transferases, which show that the third catalytic residue has increased mobility within a catalytic site and can be contributed by different secondary structure elements (Craigie 2001). Finally, it is possible that this substitution renders Fob1p catalytically inactive while preserving its structural and/or architectural role in rDNA maintenance.

Discussion

Blocked replication forks in Escherichia coli lead to increased recombination by causing the reversal of fork progression, which gives rise to structures resembling Holliday junctions. The resolution of junction proceeds through a double-stranded break (DSB) in DNA, with RuvC, a member of the polynucleotide transferase superfamily, acting as a nuclease (Seigneur et al. 1998). Similarly, a unidirectional RFB in rDNA is conserved in many eukaryotes and also is associated with increased recombination (Rothstein et al. 2000). Several nonexclusive models have been offered to explain how Fob1p controls the expansion and contraction of rDNA repeats and the formation of ERCs in yeast (Kobayashi et al. 1998; Defossez et al. 1999; Rothstein et al. 2000). In all proposed models, a DSB in DNA seems to be an essential event, but the identity of an enzyme that would act in this reaction is unknown. Furthermore, the identity of any Holliday junction-resolving enzyme in eukaryotes is unclear (Aravind et al. 2000), despite the existence of branch migration and Holliday junction-resolving activities in mammalian cell-free extracts (Constantinou et al. 2001). Sequence similarity to retroviral integrases and successful structural modeling suggest that Fob1p, in addition to its fork-blocking activity, also could act as nuclease. As argued before, any of several distinct recombination outcomes stemming from the RFB, including the formation of ERCs, can be triggered by a DSB in DNA (Rothstein and Gangloff 1999). I propose that Fob1p not only causes the replication block, but also initiates DSBs to promote recombination in rDNA. That being said, it must be emphasized that Fob1p activity is not the only requirement for rDNA maintenance in yeast. Depending on how DSBs are repaired, stimulated recombination can either increase or decrease the number of rDNA copies (Rothstein and Gangloff 1999). For example, Pol I transcription-defective strains with functional Fob1p have reduced number of rDNA repeats and the reintroduction of Pol I in the same system brings the number of rDNA copies to normal (Kobayashi et al. 1998). Therefore, it seems that additional regulatory mechanisms, involving at least Pol I (Kobayashi et al. 1998) and helicase Sgs1 (Defossez et al. 1999), operate in conjunction with Fob1p to determine the number of rDNA copies.

Acknowledgments

I thank L. Aravind and Wendy Dlakić for comments and Masayasu Nomura for sharing results before publication. This work was supported by a Special Fellowship from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.4470102.

References

- Altschul, S.F., Madden, T.L., Schaffer, A.A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., and Lipman, D.J. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrake, M.D. and Skalka, A.M. 1996. Retroviral integrase, putting the pieces together. J. Biol. Chem. 271 19633–19636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind, L., Makarova, K.S., and Koonin, E.V. 2000. Holliday junction resolvases and related nucleases: Identification of new families, phyletic distribution and evolutionary trajectories. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 3417–3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariyoshi, M., Vassylyev, D.G., Iwasaki, H., Nakamura, H., Shinagawa, H., and Morikawa, K. 1994. Atomic structure of the RuvC resolvase: A Holliday junction-specific endonuclease from E. coli. Cell 78 1063–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, T.A. and Luo, L. 1994. Identification of residues in the Mu transposase essential for catalysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 91 6654–6658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, A., Birney, E., Durbin, R., Eddy, S.R., Howe, K.L., and Sonnhammer, E.L. 2000. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 263–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, B.J. and Fangman, W.L. 1988. A replication fork barrier at the 3` end of yeast ribosomal RNA genes. Cell 55 637–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, B.J., Lockshon, D., and Fangman, W.L. 1992. The arrest of replication forks in the rDNA of yeast occurs independently of transcription. Cell 71 267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinou, A., Davies, A.A., and West, S.C. 2001. Branch migration and Holliday junction resolution catalyzed by activities from mammalian cells. Cell 104 259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigie, R. 2001. HIV integrase, a brief overview from chemistry to therapeutics. J. Biol. Chem. 276 23213–23216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defossez, P.A., Prusty, R., Kaeberlein, M., Lin, S.J., Ferrigno, P., Silver, P.A., Keil, R.L., and Guarente, L. 1999. Elimination of replication block protein Fob1 extends the life span of yeast mother cells. Mol. Cell 3 447–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyda, F., Hickman, A.B., Jenkins, T.M., Engelman, A., Craigie, R., and Davies, D.R. 1994. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of HIV-1 integrase: Similarity to other polynucleotidyl transferases. Science 266 1981–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy, S.R. 1998. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics 14 755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman, A. and Craigie, R. 1992. Identification of conserved amino acid residues critical for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase function in vitro. J. Virol. 66 6361–6369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldgur, Y., Dyda, F., Hickman, A.B., Jenkins, T.M., Craigie, R., and Davies, D.R. 1998. Three new structures of the core domain of HIV-1 integrase: An active site that binds magnesium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95 9150–9154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther, B., Onrust, R., Sali, A., O'Donnell, M., and Kuriyan, J. 1997. Crystal structure of the δ` subunit of the clamp-loader complex of E. coli DNA polymerase III. Cell 91 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayanagi, K., Miyagawa, M., Matsushima, M., Ishikawa, M., Kanaya, S., Ikehara, M., Matsuzaki, T., and Morikawa, K. 1990. Three-dimensional structure of ribonuclease H from E. coli. Nature 347 306–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil, R.L. and Roeder, G.S. 1984. Cis-acting, recombination-stimulating activity in a fragment of the ribosomal DNA of S. cerevisiae. Cell 39 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, T., Heck, D.J., Nomura, M., and Horiuchi, T. 1998. Expansion and contraction of ribosomal DNA repeats in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Requirement of replication fork blocking (Fob1) protein and the role of RNA polymerase I. Genes Dev. 12 3821–3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, T. and Horiuchi, T. 1996. A yeast gene product, Fob1 protein, required for both replication fork blocking and recombinational hotspot activities. Genes Cells 1 465–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis, P.J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, E.A. and Bacon, D.J. 1997. Raster3D: Photorealistic Molecular Graphics. Methods Enzymol. 277 505–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice, P. and Mizuuchi, K. 1995. Structure of the bacteriophage Mu transposase core: A common structural motif for DNA transposition and retroviral integration. Cell 82 209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein, R. and Gangloff, S. 1999. The shuffling of a mortal coil. Nat. Genet. 22 4–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein, R., Michel, B., and Gangloff, S. 2000. Replication fork pausing and recombination or "gimme a break." Genes Dev. 14 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali, A. and Blundell, T.L. 1993. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234 779–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, R. and Sali, A. 1998. Large-scale protein structure modeling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95 13597–13602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer, A.A., Aravind, L., Madden, T.L., Shavirin, S., Spouge, J.L., Wolf, Y.I., Koonin, E.V., and Altschul, S.F. 2001. Improving the accuracy of PSI-BLAST protein database searches with composition-based statistics and other refinements. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 2994–3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigneur, M., Bidnenko, V., Ehrlich, S.D., and Michel, B. 1998. RuvAB acts at arrested replication forks. Cell 95 419–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippl, M.J. 1993. Recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Proteins 17 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelkel-Meiman, K., Keil, R.L., and Roeder, G.S. 1987. Recombination-stimulating sequences in yeast ribosomal DNA correspond to sequences regulating transcription by RNA polymerase I. Cell 48 1071–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.Y., Ling, H., Yang, W., and Craigie, R. 2001. Structure of a two-domain fragment of HIV-1 integrase: Implications for domain organization in the intact protein. EMBO J. 20 7333–7343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]