Abstract

β2-Microglobulin (β2-m) is a major component of dialysis-related amyloid fibrils. Although recombinant β2-m forms needle-like fibrils by in vitro extension reaction at pH 2.5, reduced β2-m, in which the intrachain disulfide bond is reduced, cannot form typical fibrils. Instead, thinner and flexible filaments are formed, as shown by atomic force microscopy images. To clarify the role of the disulfide bond in amyloid fibril formation, we characterized the conformations of the oxidized (intact) and reduced forms of β2-m in the acid-denatured state at pH 2.5, as well as the native state at pH 6.5, by heteronuclear NMR. {1H}-15N NOE at the regions between the two cysteine residues (Cys25–Cys80) revealed a marked difference in the pico- and nanosecond time scale dynamics between that the acid-denatured oxidized and reduced states, with the former showing reduced mobility. Intriguingly, the secondary chemical shifts, ΔCα, ΔCO, and ΔHα, and 3JHNHα coupling constants indicated that both the oxidized and reduced β2-m at pH 2.5 have marginal α-helical propensity at regions close to the C-terminal cysteine, although it is a β-sheet protein in the native state. The results suggest that the reduced mobility of the denatured state is an important factor for the amylodogenic potential of β2-m, and that the marginal helical propensity at the C-terminal regions might play a role in modifying this potential.

Keywords: Amyloid fibrils, atomic force microscopy, β2-microglobulin, denatured state, disulfide bond, heteronuclear NMR, hydrogen/deuterium exchange

An increasing number of proteins have been found to aggregate into insoluble fibers that cause various pathologic disorders in vivo. These fibers, collectively referred to as "amyloid fibrils," have common structural features (Gillmore et al. 1997; Kelly 1998). Recent studies have shown that several proteins that are not related to any disease can also form similar amyloid-like fibers (Brange et al. 1997; Guijarro et al. 1998; Ohnishi et al. 2000; Fezoui et al. 2001; Bucciantini et al. 2002), suggesting that such a conformation is common to many proteins. Under appropriate conditions, many proteins have the potential to assume this conformation. On the other hand, amyloid fibrils are homogeneous, and it is not possible to form chimeric fibrils composed of distinct amyloid proteins or peptides (Chien and Weissman 2001). This high species barrier suggests that amyloid fibrils are stabilized by specific interactions that can distinguish between different sequences and conformations. Thus, amyloid fibrils can be considered as alternatively folded conformations of globular proteins, and understanding the properties of such fibrils is essential to obtain further insight into the conformation and folding of proteins.

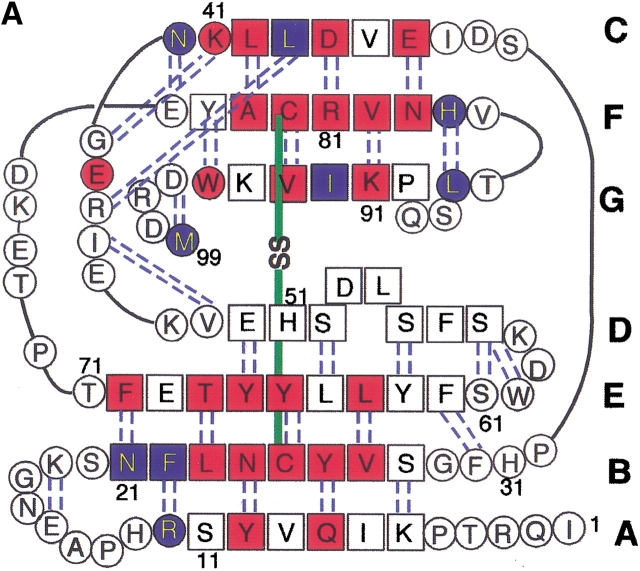

Among many amyloidogenic proteins, β2-microglobulin (β2-m), a 99-residue protein with a molecular weight of 11.8 kD, is a major target for intensive study because of its clinical importance (Fig. 1 ▶). β2-m amyloidosis has been a common and serious complication among patients on hemodialysis for more than 10 years (Gejyo et al. 1985; Casey et al. 1986; Gejyo and Arakawa 1990; Koch 1992). β2-m has been identified as a major structural component of amyloid fibrils deposited in the synovia of the carpal tunnel. In vivo, however, β2-m exists on the surface of all cells as the light chain of the class I major histocompatibility complex. It assumes a typical immunoglobulin fold, consisting of seven β-strands organized into two β-sheets connected by a disulfide bridge, Cys25–Cys80 (Bjorkman et al. 1987; Okon et al. 1992; Verdone et al. 2002). Although it is obvious that the increase in β2-m concentration in blood over a long period causes amyloidosis, the molecular mechanism of amyloid fibril formation is still unknown (McParland et al. 2000, 2002; Esposito et al. 2000; Chiti et al. 2001; Heegaard et al. 2001; Kad et al. 2001; Morgan et al. 2001).

Fig. 1.

Amino acid sequence (A) and schematic structure (B) of β2-m. Secondary structures are indicated with hydrogen bonds (A) and the numbering of β-strands (A,B). The locations of strongly (red) and weakly (blue) protected amide protons are indicated. The figure was produced using MOLMOL (Koradi et al. 1996) with the structure (PDB entry 3HLA) reported by Bjorkman et al. (1987).

Naiki et al. have been studying amyloid fibril formation of β2-m (Naiki et al. 1997; Naiki and Gejyo 1999; Yamaguchi et al. 2001) as well as other amyloid fibrils including Alzheimer's β-amyloid (Hasegawa et al. 1999). They established a kinetic experimental system to analyze amyloid fibril formation in vitro, in which the extension phase with the seed fibrils is quantitatively characterized by the fluorescence of thioflavin T (ThT) (Naiki et al. 1989, 1991). Recently, we analyzed the amyloid fibrils of β2-m prepared by the extension reaction by using a novel procedure that uses H/2H exchange of amido protons combined with NMR analysis (Hoshino et al. 2002). It is noted that a similar procedure was independently developed by Alexandrescu (2001), who investigated the model amyloid fibrils formed by cold-shock protein A. Our results with β2-m amyloid fibrils indicated that most residues in the middle region of the molecule, including the loop regions in the native structure, form a rigid β-sheet core, suggesting the mechanisms of amyloid fibril formation and its conformational stability.

Interestingly, the optimal pH for the seed-dependent fibril formation of β2-m in vitro is not at physiological pH but acidic pH, implying the important role of non-native state in forming the amyloid fibrils as suggested for other proteins (Brange et al. 1997; Guijarro et al. 1998; Khurana et al. 2001). MacParland et al. (2002) recently reported that the amyloid precursor accumulated at pH 3.6 retains stable structure in five (B, C, D, E, and F) of the seven β-strands that comprise the hydrophobic core of the native protein. They suggested that this stable region is important for amyloid fibril formation. However, the typical amyloid fibrils of β2-m were not formed at pH 3.6; instead, thinner and flexible filaments morphologically distinct from the amyloid fibrils were formed in such conditions. The optimal pH for the seed-dependent fibril formation is at pH 2.5, where β2-m is substantially denatured as judged by CD, fluorescence, and 1H NMR (Naiki et al. 1997; Naiki and Gejyo 1999; Yamaguchi et al. 2001; Ohhashi et al. 2002). On the other hand, reduced β2-m, in which the disulfide bond is reduced, cannot form amyloid fibrils at pH 2.5, although filamentous structures similar to those formed with intact β2-m at pH 3.6 have been observed (Kad et al. 2001; Smith and Radford 2001; Hong et al. 2002; Ohhashi et al. 2002).

It has been shown that some residual structures exist in several proteins even when they are highly denatured (Shortle 1996; Shortle and Acherman 2001). It is likely that subtle differences in the denatured or intermediate states between the intact and reduced β2-m result in the large differences in their amyloidogenic potentials at pH 2.5. In this context, it is important to characterize the acid-denatured state of β2-m in detail, as the residual structures may play a critical role in fibril formation. Characterization of the conformation and dynamics at the atomic level under acidic conditions may provide clues to understand the mechanism of amyloid fibril formation, which can be useful in clarifying its formation under physiologic conditions. In this study, we characterized the oxidized and reduced forms of β2-m in the acid-denaturation as well as the native state by multidimensional NMR methods.

Results

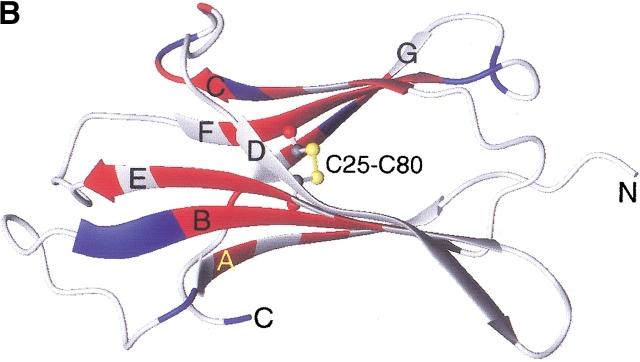

Atomic force microscopy

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was used to characterize the structures of fibrils formed with oxidized β2-m and the filamentous structures formed with reduced β2-m. AFM images of β2-m fibrils prepared by the extension reaction showed typical characteristics of amyloid fibrils (Fig. 2A–C ▶). The fibrils are remarkably straight, with a length of about 1–2 μm, and are uniform in their height (i.e., diameter) of 14 nm. These rigid needle-like and uniformly structured fibrils are basically similar to that observed by electron microscopy (EM) (Naiki et al. 1997; Yamaguchi et al. 2001; Hong et al. 2002; Ohhashi et al. 2002), but the images obtained here were much clearer. We observed a longitudinal periodicity of about 100 nm and a left-handed spiral structure. Moreover, the ends of the fibrils are not frayed but are clearly cut, implying that the extension reaction occurred in a highly cooperative manner. Similar AFM images of β2-m amyloid fibrils were reported by Kad et al. (2001).

Fig. 2.

AFM images of amyloid fibrils and filaments of β2-m. (A–C) Intact β2-m fibrils; (D–F) reduced β2-m filaments. (A,B) Amplitude images; (C–E) topographic images; (F) a 3D image. The full scales of (A) and (D) are 5 μm and those of (B), (C), (E), and (F) are 2 μm. The scale on the bottom represents the height of pixels in the image; the lighter the color the higher the feature is from the surface.

The reduced β2-m incubated in the presence of seeds also showed very clear AFM images (Fig. 2D–F ▶). However, they differed from intact fibrils in several respects. First, the filaments are highly flexible. Second, the filaments are again uniform in diameter (2 nm), but are much thinner than intact β2-m fibrils. Third, the filaments of reduced β2-m are generally longer than the intact β2-m fibrils. The filamentous images of the reduced β2-m observed here are similar to the EM images of the filamentous structures of reduced β2-m prepared either in the presence or absence of seeds at pH 2.5 (Ohhashi et al. 2002), indicating that the filaments were formed independently of the seeds. The AFM images of the reduced β2-m are also similar to filamentous structures of intact β2-m formed at pH 2.5 in the presence of high salt without seeds (data not shown, see also McParland 2000; Kad et al. 2001; Smith and Radford 2001; Hong et al. 2002).

At first glance, the filaments of reduced β2-m had the appearance of thin, flexible hair strands obtained by unwinding a tight braid, implying that the intact rigid β2-m fibrils were produced by braiding flexible filaments of reduced β2-m. However, as the reduced β2-m could not form rigid fibrils under any conditions (Ohhashi et al. 2002) and they are easily formed with intact β2-m under high salt conditions where hydrophobic interactions are strengthened (McParland 2000; Kad et al. 2001; Hong et al. 2002), the filamentous structures do not seem to represent a productive intermediate of fibril formation. These filaments are likely to be dead-end products failing to cooperatively form tightly associated fibrils. The observation of blunt ends of the fibrils with no fraying (Fig. 2A–C ▶) supported this interpretation.

NMR analysis of the native state

To understand the molecular mechanism of fibril formation specific to intact β2-m with the disulfide bond, we used heteronuclear NMR approaches to characterize the three conformational states of β2-m, that is, the native state at pH 6.5, oxidized and reduced forms of acid-denatured β2-m at pH 2.5.

Assignments

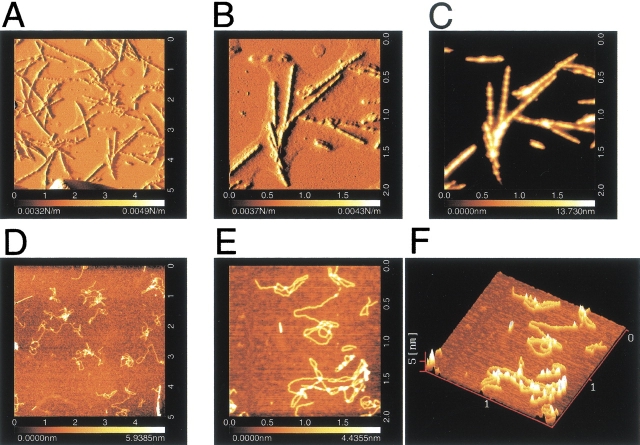

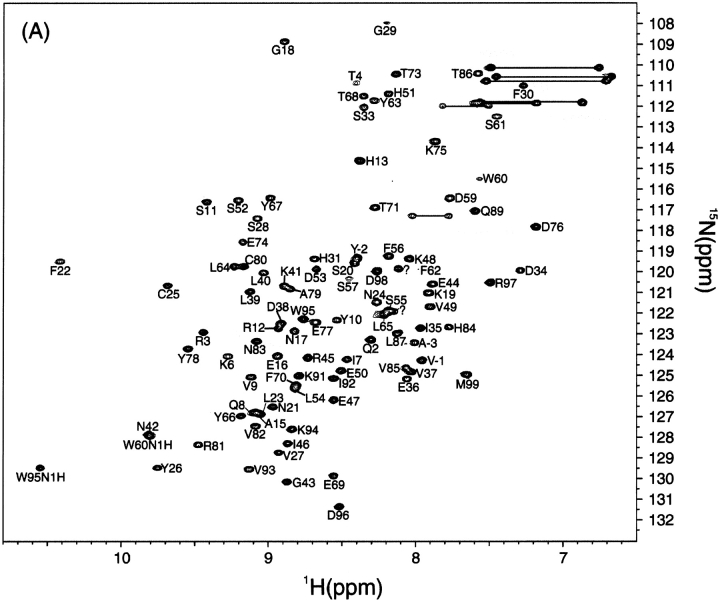

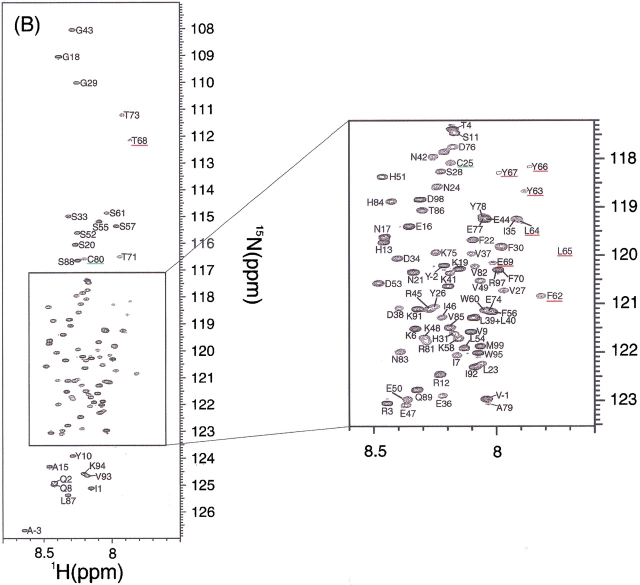

First, the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of the recombinant β2-m at pH 6.5 and 37°C showed a spectrum of high dispersion of crosspeaks, as expected for a small β-sheet protein (Fig. 3A ▶). The assignment of the native state was accomplished by analyzing HNCACB spectra. Some ambiguities were resolved by a combination of TOCSY-HSQC and NOESY-HSQC spectra. As a result, among a total of 97 residues expected for the HSQC spectrum, 95 were unambiguously assigned (Supplemental Material: Table 1). Ser88 was missing in all the spectra acquired and could not be assigned. The chemical shift values of the native state were mostly in good agreement with those reported previously, although they provide only 1H (Okon et al. 1992; Esposito et al. 2000; Verdone et al. 2002) or 1H and 15N chemical shifts (McParland et al. 2002). Our assignment was important in that it provided a 13C chemical shift, which is a more reliable indicator of the secondary structure than the 1H chemical shift.

Fig. 3.

(Panel C appears on facing page.) 1H-15N HSQC spectra of β2-m in the native state at pH 6.5 (A), the acid-denatured states of intact β2-m (B), and reduced β2-m (C) at pH 2.5. Temperature was 37°C. The underlined residues had weak peak intensities.

Chemical shifts

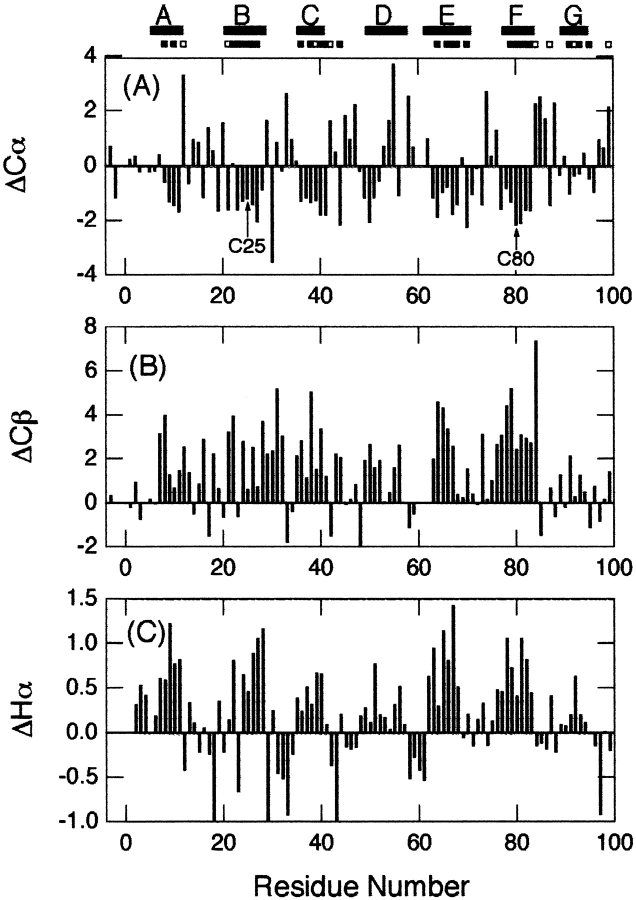

Based on the resonance assignments, Cα, Cβ, and Hα chemical shift differences from random coil chemical shifts (i.e., secondary chemical shifts: ΔCα, ΔCβ, and ΔHα, respectively), which are excellent indicators of secondary structures (Wishart et al. 1995), were plotted for the native state at pH 6.5 (Fig. 4 ▶). Negative ΔCα, positive ΔCβ, and positive ΔHα indicate that the residue is part of a β-sheet, whereas the opposite signs indicate an α-helix. The overall patterns of ΔCα, ΔCβ, and ΔHα were similar to each other, and were consistent with the locations of β-strands obtained from the X-ray structure (Bjorkman et al. 1987) or the three-dimensional (3D) structure determined recently by NMR (Verdone et al. 2002).

Fig. 4.

Secondary chemical shifts of backbone resonances versus residue number of β2-m in the native state at pH 6.5. (A) ΔCα, (B) ΔCβ, and (C) ΔHα. The locations of secondary structures obtained from the X-ray structure and Cys residues are indicated. The locations of highly (more than 24 h) and moderately (at least 10 min) protected amide protons are indicated by closed and open bars, respectively, under the locations of secondary structures. The chemical shift of the random coil was calculated on the basis of the previous report by Wishart et al. (1995).

H/2H exchange

We performed H/2H exchange experiments on native β2-m to probe the stability of each residue at 5°C and pDr 6.5, where pDr is a pH meter electrode reading without correction for the isotope effect. To follow the exchange kinetics of as many residues as possible, experiments were performed at 5°C. Nevertheless, in the first spectrum recorded 10 min after starting the exchange, about two-thirds of the residues disappeared, as the intrinsic exchange rate is relatively large at pDr 6.5. Attempts to lower the pH value failed because of the protein's tendency to aggregate at pH lower than 6.5.

Residues in the β-strands were strongly protected from exchange (Figs. 1 and 4 ▶ ▶), indicating the presence of a stable core consisting of all the β-strands except βD. βD connects the two β-sheet layers and is not involved in the core of β2-m. Also, this result showed that the strongly protected residues were not limited to the two strands linked by the disulfide bridge, but extended over other β-strands, suggesting that the structure of β2-m is stabilized by all the β-strands.

NMR analysis of the acid-denatured states

Assignments

In contrast to the native state, the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of the acid-denatured state of β2-m with the disulfide bond at pH 2.5 and 37°C showed that all the peaks are located in the limited range of HN chemical shifts from 7.8 to 8.6 ppm, suggesting that β2-m is highly denatured (Fig. 3B ▶). Peak assignments were obtained by HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, HN(CA)CO, and HNCO, which can provide a sequential connectivity of Cα, Cβ, and CO resonances. Furthermore, the sequential connectivity was confirmed by analyzing the HSQC-NOESY-HSQC spectrum, in which most of the dNN(i,i+1) crosspeaks were observed except at the N and C terminal regions. As a result, we could assign all the backbone amide protons in the oxidized from of β2-m (Supplemental Material: Table 2).

We anticipated that the chemical shift values of the reduced β2-m in the denatured state are only slightly different from those of the intact β2-m in the denatured state. Indeed, the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of the reduced β2-m at pH 2.5 (Fig. 3C ▶) revealed that most of the peaks shifted only slightly upon reduction of the disulfide bond. Moreover, peaks of the reduced form were sharper than those of the oxidized form, probably because of the highly dynamic nature of the molecule due to the absence of the disulfide bridge (below). Therefore, assignments were obtained, without using doubly labeled proteins, on the basis of those of the intact β2-m. The combination of HSQC-NOESY-HSQC, TOCSY-HSQC and NOESY-HSQC with 15N-labeled β2-m provided a complete assignment of the reduced form of β2-m (Supplemental Material: Table 2). One of the interesting aspects of Figures 3B and C ▶ is that there is a large degree of variation in the intensities of each peak. In particular, the intensities of the residues from Ser61 to Phe70 were very weak in both the oxidized and reduced forms, suggesting a nonrandom nature of this region.

Chemical shifts and 3JHNHα coupling constants

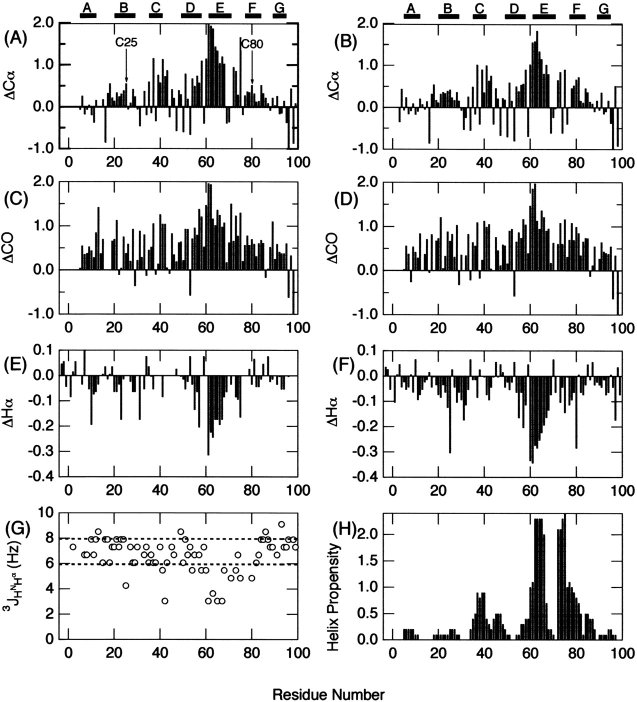

Based on the resonance assignments, secondary chemical shifts, ΔCα, ΔCO, and ΔHα, of the acid-denatured state of the intact β2-m at pH 2.5, are plotted in Figure 5A, C, and E ▶, respectively. In the case of the acid-denatured intact β2-m, we included ΔCO and its positive and negative values representing α-helix and β-sheet, respectively. In marked contrast to the native state, secondary chemical shift values had low intensities, confirming that the molecule is substantially disordered at pH 2.5, consistent with the CD spectrum under the same conditions (Ohhashi et al. 2002).

Fig. 5.

Secondary chemical shifts of backbone resonances versus residue number of the acid-denatured β2-m at pH 2.5. (A,B) ΔCα, (C,D) ΔCO, (E,F) ΔHα of the intact β2-m (A,C,E) and reduced (B,D,F) β-2m. (G) 3JHNHα values for the acid-denatured state of intact β2-m. (H) Helical propensity prediction by the program AGADIR (Múnos and Serrano 1994). The locations of secondary structures obtained from the X-ray structure are indicated in (A) and (B). For ΔCα and ΔCO, correction factors reported by Schwarzinger et al. (2001) were taken into consideration.

However, ΔCα, ΔCO, and ΔHα indicated frequent sampling of the helical conformation over the whole sequence in the acid-denatured state, although β2-m assumes a β-sheet conformation in the native state. In particular, the region between residues Lys58–Thr68 showed notable and persistent deviations characteristic of helical conformation. The non-negligible tendency for taking the helical conformation was supported by the observation that most of the dNN(i,i+1) crosspeaks were observed in the HSQC-NOESY-HSQC spectrum. In contrast, the unfolded state of apo-plastocyanin formed under nondenaturing conditions showed few cross-peaks, indicating the preference for β rather than helical conformation (Bai et al. 2001).

In Figure 5G ▶, the 3JHNHα coupling constants for the acid-denatured state of intact β2-m were plotted against residue number. In general, the values for most residues were located in the range of 6.0 to 8.0 Hz, reflecting random backbone motions over distributions of dihedral angles. However, several residues had notable deviations from these values. In particular, Ser61, Tyr63, Leu65, and Tyr67, which, located in the region suggested to be notably helical based on the chemical shift data, showed anomalously low values. Because small coupling constants less than 6.0 Hz are indicative of helical or turn structure, the results were consistent with the chemical shift data. Although chemical shifts and 3JHNHα coupling constants were characteristic of a helical structure, the medium range NOE (dαN[i,i+3]) indicative of an α-helix was not observed in the NOESY spectrum. This implied that the region corresponding to βE strand in the native state exhibits a marginal helical structure in the acid-denatured state.

The overall patterns of ΔCα, ΔCO, and ΔHα in the acid-denatured state of reduced β2-m are similar to those of intact β2-m (Fig. 5B,D,F ▶), consistent with the global unfolding of the molecule. Again, the region between residues Lys58–Thr68 showed notable deviations characteristic of helical conformation. Consistent with these observations, the CD spectra of both the intact and reduced proteins in the acid-denatured state hint the presence of a small amount of helical structure (Ohhashi et al. 2002). Intriguingly, the ΔHα values in the reduced state were evidently larger than those in the oxidized state in particular for this region. The validity of this observation is unknown, however, because ΔCα and ΔCO do not show such propensity.

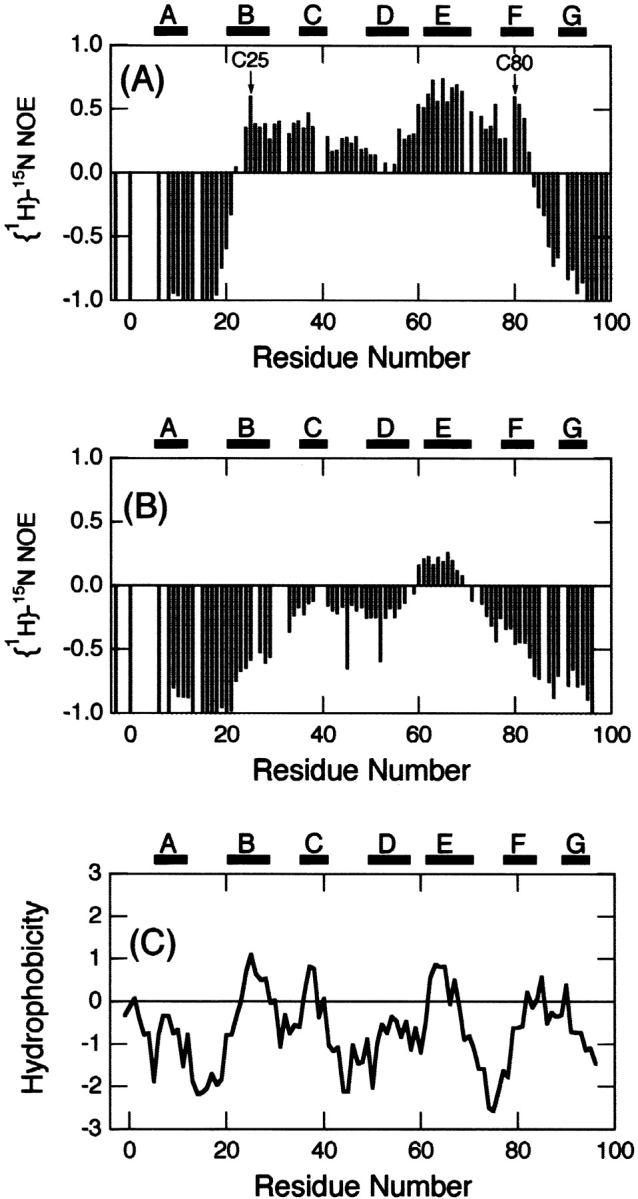

Backbone dynamics

To assess the backbone dynamics on a pico- to nanosecond timescale, {1H}-15N NOE (Farrow et al. 1994) was measured for both the oxidized and reduced forms of β2-m at pH 2.5 (Fig. 6 ▶). For intact β-2m, the region between Cys25 and Cys80 showed positive NOE values, whereas the N- and C-terminal regions showed negative values. This result indicated the flexibility of the N- and C-terminal regions and rigidity around the disulfide bond. On the other hand, reduced β2-m showed negative values over the whole sequence except the region between Ser61 to Phe70, and the NOE intensity was inversely proportional to the distance from the ends of the polypeptide chain. The reduction of the disulfide bond therefore significantly increased the flexibility of the molecule, although the region between Ser61 to Phe70 was still weakly restrained.

Fig. 6.

{1H}-15N NOE heteronuclear NOE for the backbone amide nitrogen atoms of the intact (A) and reduced (B) β2-m measured at 500 MHz on the normal scale at pH 2.5 and 37°C. (C) Hydrophobicity of β2-m plotted against residue number. Hydrophobicity was calculated using the scale of Kyte and Doolittle (1982) averaged over a sliding window of seven residues. The locations of secondary structures obtained from the X-ray structure and Cys residues are indicated in (A).

Discussion

Differences between the intact and reduced β2-m

Although the intact β2-m formed typical amyloid fibrils by the seed-dependent extension reaction at pH 2.5, the reduced β2-m is incapable of fibril formation. It is likely that the acid-denatured state of intact β2-m represents an intermediate of amyloid fibril formation and that the conformational features important for fibril formation are destroyed by the reduction of the disulfide bond. Thus, the remaining structures in the acid-denatured state of β2-m and the conformational differences between the intact and reduced β2-m are important in clarifying the structural determinant(s) of amyloid fibril formation. As described above, two unique features were detected for the acid-denatured β2-m. One is the increase in nano- to picosecond dynamics of the residues between the disulfide bond, Cys25–Cys80, and the other is the weak but still notable helical propensities at regions close to the C-terminal cysteine observed for both the intact and reduced β2-m. We now consider the roles of these features in amyloid fibril formation.

Although the reduction in nano- to picosecond dynamics of the residues between the disulfide-bonded loop might be expected from the restriction imposed by the disulfide bond, the results are important because it indicates that the ability of β2-m to form amyloid fibrils is closely related to the conformational dynamics of the non-native state. In addition, we are interested in the weakly restricted residues Ser61–Phe70 in the reduced β2-m, the same region that exhibited the marginal helical propensity. Hydropathy index (Kyte and Doolittle 1982) shows that hydrophobicity of the corresponding region is moderately high (Fig. 6C ▶). In accordance with this, half of the residues in the very unique sequence (SFYLLYYTEF) are aromatic. It is likely that the reduced flexibility is linked with the clustering of hydrophobic residues in this region.

The other unique feature of the acid-denatured β2-m is the weak but notable helical propensities in both the oxidized and reduced states. Considering that β2-m is composed of β-sheet in the native state, the weak preference for helical conformation rather than β-conformation over the whole sequence was surprising. To probe the origin of this helical preference, we estimated the helical propensity of the β2-m sequence by AGADIR (Fig. 5H ▶) (Múnos and Serrano 1994). Although the helical propensities are very low in comparison with those of highly helical proteins such as myoglobin, the overall pattern was surprisingly similar to that of ΔCα; three regions showing weak α-helical propensities in the profile (i.e.,Val37–Leu40, Trp60–Tyr67, Pro72–Glu77) coincide with the region of notable helicity in the acid-denatured state (Fig. 5A,B ▶). Therefore, the frequent sampling of helical conformation of these regions observed by NMR chemical shifts may reflect the intrinsic weak preference for helical structure of the sequence.

Implication for the role of disulfide bond

By analyzing the amyloidogenic potentials of peptide fragments produced by digestion with Acromobacter protease I, we found that the 22-residue peptide fragment Ser20–Lys41 (K3 peptide) retains the potential to form typical amyloid fibrils, suggesting that Ser20–Lys41 includes the minimal region required for amyloid fibril formation (Kozhukh et al. 2002). The observation that reduced β2-m could not form typical amyloid fibrils is apparently inconsistent with the fibril formation of K3 peptide because K3 peptide does not have the disulfide bond. The reason why the amyloidogenic potential lost upon reduction of the disulfide bond was restored by fragmentation is not clear. Nevertheless, it is tempting to assume that the notable helical propensity located at Lys58–Thr68 plays a role in determining the amyloidogenic potential of β2-m (see below).

The differences in amyloidogenic potential of intact and reduced β-2m may be explained as follows. The notable helical propensity located at Lys58–Thr68 plays an inhibitory role in forming amyloid fibrils that are composed of β-sheet structures. In the intact β-2m, however, the restricted mobility caused by the disulfide bond stabilizes the intermediate state, resulting in apparent shielding of the inhibitory effect. Reduction of the disulfide bond destabilizes the intermediate state by increasing the flexibility of the molecule and, consequently, by revealing an inhibitory role of the helical propensity. This results in the formation of dead-end products, that is, thinner and highly flexible filaments. As the inability of reduced β2-m to form typical amyloid fibrils is mainly due to the inhibitory effect of the region, which includes Lys58–Thr68, its deletion restores the amyloidogenic potential, as indicated by fibril formation of the K3 peptide (Kozhukh et al. 2002). Of course, additional experimental data is required to verify the validity of this hypothetical mechanism. On the other hand, it is clear from the present results that the restrained backbone dynamics on a pico- to nanosecond time scale is important for the amyloidogenic potential of intact β2-m.

We previously proposed a two-region mechanism of amyloid fibril formation of β2-m (Kozhukh et al. 2002). The β2-m molecule is assumed to consist of two regions: that is, essential (or minimal) and nonessential regions. The essential region even after isolation can form fibrils by itself and K3 peptide (Ser20–Lys41) accommodates such a region. For intact β2-m, unfolding of the native structure is necessary to expose the essential region. On the other hand, although the nonessential region cannot form the amyloid fibrils by itself, it can participate in fibril formation passively once it is associated with the essential region. In other words, the core β-sheet formed in the essential region can propagate by itself to the rest of the molecule. In fact, the H/D exchange experiments of the amyloid fibrils indicate that the regions with notable helicity (Lys58–Thr68) also form the rigid amyloid structures (Hoshino et al. 2002). Thus, the present results suggest that nonessential regions not only participate in fibril formation but also determine the amyloidogenic potential of a protein.

Conclusions

β2-m is one of the most important targets of molecular and structural studies of amyloid fibril formation because of its relatively small size suitable for high-resolution structural analysis. β2-m, a component of class I MHC antigen, assumes a typical immunoglobulin domain-fold with an intrachain disulfide bond buried in the protein molecule. Previously, we reported that, although this disulfide bond is not essential for maintaining an immunoglobulin fold, it is essential for forming amyloid fibrils (Ohhashi et al. 2002). Intriguingly, reduced β2-m formed thinner and flexible fibrous structures, which were presumably a dead-end product. In this study, we characterized the conformational features of the reduced and oxidized forms of β2-m in the acid-denatured state and demonstrated the differences in pico- to nanosecond dynamics between these two forms. Moreover, a weak but notable α-helical propensity at regions close to the C-terminal cysteine was also found. It is likely that these conformational differences in the denatured states determine the amyloidogenic potential of β2-m, although the exact mechanism is still unclear. A study on β2-m mutants with altered α-helical propensity is an interesting topic to address the role of secondary structure propensity in β-sheet-rich amyloid fibril formation.

Materials and methods

Materials

15N-Ammonium hydroxide was purchased from Shoko Co., Ltd. 13C3-Glycerol and 13C-methanol were purchased from Nippon Sanso Co. Other reagents were purchased from Nacalai Tesque.

Recombinant human β2-m was expressed in methyltrophic yeast Pichia pastoris and purified as described previously (Kozhukh et al. 2002; Ohhashi et al. 2002). Among three types of β2-m with different N-terminal sequences, we used the major fraction, which has additional four residues at the N-terminus, E(-4)-A(-3)-Y(-2)-V(-1)-I(1). It has been confirmed that recombinant β2-m is indistinguishable from β2-m derived from patients with respect to amyloid fibril formation. Uniformly 15N- and 15N/13C-labeled β2-m was obtained using 15N-ammonium hydroxide, 13C3-glycerol, and 13C-methanol as the sole nitrogen and carbon sources.

Reduced β2-m was prepared as follows. About 5 mg of lyophilized β2-m was dissolved in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) containing 4 M Gdn-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM DTT. The reaction mixture was left at room temperature for 3 h to reduce the disulfide bond. After reduction, the excess reagents were removed by gel filtration with a PD10 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated with 3 mM HCl (pH 2.5), which was degassed before use. Then, the sample solution was concentrated to about 500 μL with a Centricon (Amicon) at 4°C, and the pH was readjusted to 2.5 with small aliquots of 10 mM HCl.

β2-m amyloid fibrils were prepared by the fibril extension method established by Naiki et al. (1997, 1999) and as described previously (Kozhukh et al. 2002; Ohhashi et al. 2002), in which the fragmented seed fibrils were extended by the monomeric proteins and the reaction was monitored by fluorometric analysis with ThT. The filaments of the reduced β2-m were formed by the same procedures as used for the fibril extension reaction except that the monomeric β2-m was replaced by the reduced β2-m.

AFM measurements

A 10-μL sample drop was spotted on freshly cleaved mica. After standing on the substrate for 1 min, the residue solution was blown off with compressed air and air dried. AFM images were obtained using a dynamic force microscope (SPI3700-SPA300, Seiko Instruments). The scanning tip used was a Si microcantilever (SI-DF20, Seiko Instruments, spring constant = 13 N/m, resonance frequency = 135 kHz). The protein concentration was 5 ng/μL for intact β2-m and 0.5 ng/μL for reduced β2-m, respectively. The scan rate was 1 Hz.

NMR measurements

The spectra were all recorded at 37°C on a 500 MHz spectrometer (Bruker DRX 500) equipped with a triple-axis-gradient triple-resonance probe. The sample conditions were 1 mM β2-m in 50 mM Na phosphate (pH 6.5) for the native state, and 1 mM β2-m in 3 mM HCl (pH 2.5) for both the oxidized and reduced forms of the acid-denatured state.

The assignment of the native state was obtained by analyzing the 3D HNCACB (Wittekind and Mueller 1993), NOESY-HSQC (Marion et al. 1989), with a mixing time of 200 msec and TOCSY HSQC (Marion et al. 1989), with mixing times of 58.7 and 39.1 msec. For assignment of the oxidized form of the acid-denatured state, triple resonance experiments HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, HNCO, and HN(CA)CO (Grzesiek and Bax 1992a, 1992b) were recorded. Assignments obtained were confirmed by analyzing the HSQC-NOESY-HSQC (Ikura et al. 1990) with a mixing time of 200 msec. The 1H chemical shifts were referenced with respect to 2.2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonic acid (DSS). The chemical shifts for 13C and 15N were indirectly referenced. The assignment of reduced β2-m was accomplished by the combination of HSQCNOESY-HSQC, NOESY-HSQC, and TOCSY-HSQC. The peak intensities were invariant throughout the experiment, confirming that self-association reaction does not occur during the measurement.

H/2H exchange in the native state was performed at 5°C and pDr 6.5. About 5 mg of lyophilized 15N-labeled β2-m was dissolved in 50 mM Na phosphate buffer (pDr = 6.5), which was deuterated prior to the experiment. Then the sample solution was immediately loaded into a NMR tube and the HSQC spectra were recorded successively. The spectral widths were 8012.82 Hz for 1H and 1621.9 Hz for 15N, and four scans of 1024 data points were collected in each of 256 t1 increments. To obtain the assignment at 5°C, we separately measured sevearl HSQC spectra of β2-m without H/2H exchange by gradually decreasing temperature from 37°C. By following the shift of the peaks upon the temperature change, we were able to assign most of the residues at 5°C, the chemical shift values of which were slightly different from those at 37°C, depending on the residues (data not shown).

The measurement of steady-state heteronuclear 1H-15N NOE was carried out at 37°C according to the procedure described by Farrow et al. (1994). The NOE values were calculated as the ratios of peak heights from spectra obtained with and without a 1H saturation period. Data processing and analysis were performed using nmrPipe, nmrDraw, and PIPP (Garret et al. 1991; Delaglio et al. 1995).

Electronic supplemental material

Supplemental material is presented for polypeptide backbone 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shifts for β2-m in the native state at pH 6.5 and 37°C (Table 1) (table 1.doc), and for polypeptide backbone 1H, 13C, and 15N chemical shifts for β2-m in the acid denatured states with and without disulfide bond at pH 2.5 and 37°C (Table 2) (table 2.doc) (see www.proteinscience.org).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Gennady Kozhukh for the preparation of β2-m, and Professors Toshio Yamazaki and Hideo Akutsu for help with the NMR experiments. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

AFM, atomic force microscopy

β2-m, β2-microglobulin

EM, electron microscopy

HSQC, heteronuclear single quantum coherence spectroscopy

NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance

NOE, nuclear Overhauser effect

NOESY, nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy

pDr, pH meter electrode reading without correction for the isotope effect

ThT, thioflavin T

TOCSY, total correlation spectroscopy

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.0213202.

References

- Alexandrescu, A. 2001. An NMR-based quenched hydrogen exchange investigation of model amyloid fibrils formed by cold shock protein A. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 67–78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y., Chung, J., Dyson, H.J., and Wright, P.E. 2001. Structural and dynamic characterization of an unfolded state of polar apo-plastocyanin formed under nondenaturing conditions. Protein Sci. 10 1056–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkman, P.J., Saper, M.A., Samraoui, B., Bennett, W.S., Strominger, J.L., and Wiley, D.C. 1987. Structure of the human class I histocompatibility antigen, HLA-A2. Nature 329 506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brange, J., Andersen, L., Laursen, E.D., Meyn, G., and Rasmussen, E. 1997. Toward understanding insulin fibrillation. J. Pharm. Sci. 86 517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucciantini, M., Giannoni, E., Chiti, F., Baroni, F., Formigli, L., Zurdo, J., Taddei, N., Ramponi, G., Dobson, C.M., and Stefani, M. 2002. Inherent toxicity of aggregates implies a common mechanism for protein misfolding diseases. Nature 416 507–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey, T.T., Stone, W.J., Diraimondo, C.R., Barantley, B.D., Diraimondo, C.V., Gorevic, P.D., and Page, D.L. 1986. Tumoral amyloidosis of bone of β2-microglobulin origin in association with long-term hemodialysis. Hum. Pathol. 17 731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien, P. and Weissman, J.S. 2001. Conformational diversity in a yeast prion dictates its seeding specificity. Nature 410 223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiti, F., Mangione, P., Andreola, A., Giorgetti, S., Stefani, M., Dobson, C.M., Bellotti, V., and Taddei, N. 2001. Detection of two partially structured species in the folding process of the amyloidogenic protein β2-microglobulin. J. Mol. Biol. 307 379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio, F., Grzesiek, S., Zhu, V.G., Preifer, J., and Bax, A. 1995. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX Pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, G, Michelutti, R., Verdone, G., Viglino, P., Hernández, H., Robinson, C.V., Amoresano, A., Dal Piaz, F., Monti, M., Pucci, P., Mangione, P., Stoppini, M., Merlini, G., Ferri, G., and Bellotti, V. 2000. Removal of the N-terminal hexapeptide from human β2-microglobulin facilitates protein aggregation and fibril formation. Protein Sci. 9 831–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow, N.A., Muhandiram, R., Singer, A.U., Pascal, S.M., Kay, C.M., Gish, G., Shoelson, S.E., Pawson, T., Forman-Kay, J.D., and Kay L.E. 1994. Backbone dynamics of a free and a phosphopeptide-complexed Src homology 2 domain studied by 15N NMR relaxation. Biochemistry 33 5984–6003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fezoui, Y., Hartley, D.M., Walsh, D.M., Selkoe, D.J., Osterhout, J.J., and Teplow, D.B. 2001. A de novo designed helix-turn-helix peptide forms nontoxic amyloid fibrils. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2 990–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garret, D.S., Powers, R., Gronenborn, A.M., and Clore, G. M. 1991. A common sense approach to peak picking in two-, three-, and four dimensional spectra using automatic coupler analysis of contour diagrams. J. Magn. Reson. 95 214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gejyo, F. and Arakawa, M. 1990. Dialysis amyloidosis: Current disease concepts and new perspectives for its treatment. Contrib. Nephrol. 78 47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gejyo, F., Yamada, T., Odani, S., Nakagawa, Y., Arakawa, M., Kunitomo, T., Kataoka, H. Suzuki, M., Hirasawa, Y., Shirahama, T., Cohen, A.S., and Schmid, K. 1985. A new form of amyloid protein associated with chronic hemodialysis was identified as β2-microglobulin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 129 701–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore, J.D., Hawkins, P.N., and Pepys, M.B. 1997. Amyloidosis: A review of recent diagnostic and therapeutic developments. Br. J. Haematol. 99 245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzesiek, S. and Bax, A. 1992a. Correlating backbone amide and side chain resonances in larger proteins by multiple relayed triple resonance NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114 6291–6293. [Google Scholar]

- Grzesiek, S. and Bax, A. 1992b. Improved 3D triple resonance NMR techniques applies to a 31 kDa protein. J. Magn. Reson. 96 432–440. [Google Scholar]

- Guijarro, J.I., Sunde, M., Jones, J.A., Campbell, I.D., and Dobson, C.M. 1998. Amyloid fibril formation by an SH3 domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95 4224–4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, K., Yamaguti, I., Omata, S., Gejyo, F., and Naiki, H. 1999. Interaction between Aβ(1–42) and Aβ(1–40) in Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibril formation in vitro. Biochemistry 38 15514–15521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heegaard, N.H.H., Sen, J.W., Kaarsholm, N.C., and Nissen, M.H. 2001. Conformational intermediate of the amyloidogenic protein β2-microglobulin at neutral pH. J. Biol. Chem. 276 32657–32662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino, M., Katou, H., Hagihara, Y., Hasegawa, K., Naiki, H., and Goto, Y. 2002. Mapping the core of the β2-microglobulin amyloid fibrils by H/D exchange. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9 332–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D.-P., Gozu, M., Hasegawa, K., Naiki, H., and Goto, Y. 2002. Conformation of β2-microglobulin amyloid fibrils analyzed by reduction of the disulfide bond. J. Biol. Chem. 277 21554–21560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikura, M., Bax, A., Clore, G.M., and Gronenborn, A.M. 1990. Detection of nuclear overhauser effects between degenerate amide proton resonances by heteronuclear 3-dimensional nuclear-magnetic-resonance spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112 9020–9022. [Google Scholar]

- Kad, N.M., Thomson, N.H., Smith, D.P., Smith, D.A., and Radford, S.E. 2001. β2-Microglobulin and its deamidated variant, N17D form amyloid fibrils with a range of morphologies in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 313 559–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.W. 1998. The alternative conformations of amyloidogenic proteins and their multi-step assembly pathways. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana, R., Gillespie, J.R., Talapatra, A., Minert, L.J., Ionescu-Zanetti, C., Millett, I., and Fink, A.L. 2001. Partially folded intermediates as critical precursors of light chain amyloid fibrils and amorphous aggregates. Biochemistry 40 3525–3535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch, K.M. 1992. Dialysis-related amyloidosis. Kidney Int. 41 1416–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koradi, R., Billeter, M., and Wüthrich, K. 1996. MOLMOL: A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozhukh, G.V, Hagihara, Y., Kawakami, T., Hasegawa, K., Naiki, H., and Goto, Y. 2002. Investigation of a peptide responsible for amyloid fibril formation of β2-microglobulin by acromobacter protease I. J. Biol. Chem. 277 1310–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyte, J. and Doolittle, R.F. 1982. A simple method for displaying the hydrophobic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157 105–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion, D., Driscoll, P.C., Kay, L.E., Wingfield, P.T., Bax, A., Gronenborn, A.M., and Clore, G.M. 1989. Overcoming the overlap problem in the assignment of 1H NMR spectra of larger proteins by use of three-dimensional heteronuclear 1H-15N Hartmann-Hahn multiple quantum coherence spectroscopy: Application to interleukin 1β. Biochemistry 28 6150–6156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McParland, V.J., Kad, N.M., Kalverda, A.P., Brown, A., Kirwin-Jones, P., Hunter, M.G., Sunde, M., and Radford, S.E. 2000. Partially unfolded states of β2-microglobulin and amyloid formation in vitro. Biochemistry 39 8735–8746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McParland, V.J., Kalverda, A.P., Homans, S.W., and Radford, S.E. 2002. Structural properties of an amyloid precursor of β2-microglobulin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9 326–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, C.J., Gelfand, M., Atreya, C., and Miranker, A.D. 2001. Kidney dialysis-associated amyloidosis: A molecular role of copper in fiber formation. J. Mol. Biol. 309 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Múnos, V. and Serrano, L. 1994. Elucidating the folding problem of helical peptides in solution. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1 399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naiki, H. and Gejyo, F. 1999. Kinetic analysis of amyloid fibril formation. Methods Enzymol. 309 305–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naiki, H., Hashimoto, N., Suzuki, S., Kimura, H., Nakakuki, K., and Gejyo, F. 1997. Establishment of a kinetic model of dialysis-related amyloid fibril extension in vitro. Amyloid 4 223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Naiki, H., Higuchi, K., Hosokawa, M., and Takeda, T. 1989. Fluorometric determination of amyliod fibrils in vitro using the fluorescent dye, thioflavine T. Anal. Biochem. 177 244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naiki, H., Higuchi, K., Nakakuki, K., and Takeda, T. 1991. Kinetic analysis of amyloid fibril polymerization in vitro. Lab. Invest. 65 104–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohhashi, Y., Hagihara, Y., Kozhukh, G., Hoshino, M., Hasegawa, K., Yamaguchi, I., Naiki, H., and Goto, Y. 2002. The intrachain disulfide bond of β2-microglobulin is not essential for the immunoglobulin fold at neutral pH, but is essential for amyloid fibril formation at acidic pH. J. Biohem. 131 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi, S., Koide, A., and Koide, S. 2000. Solution conformation and amyloid-like fibril formation of a polar peptide derived from a β-hairpin in the OspA single-layer β-sheet. J. Mol. Biol. 301 477–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okon, M., Bray, P., and Vucelic, D. 1992. 1H NMR Assignments and secondary structure of human β2-microglobulin in solution. Biochemistry 31 8906–8915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzinger, S., Kroon, G.J.A., Foss, T.R., Chung, J., Wright, P.E., and Dyson, H.J. 2001. Sequence dependent correction of random coil NMR chemical shifts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123 2970–2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortle, D. 1996. Structural analysis of non-native states of proteins by NMR methods. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 6 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortle, D. and Acherman, M.S. 2001. Persistence of native-like topology in a denatured protein in 8 M urea. Science 293 487–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D. and Radford, S.E. 2001. Role of the single disulphide bond of β2-microglobulin in amyloidosis in vitro. Protein Sci. 10 1775–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdone, G., Corazza, A., Viglino, P., Pettirossi, F., Giorgetti, G., Mangione, P., Andreola, A., Stoppini, M., Bellotti, V., and Esposito, G. 2002. The solution structure of human β2-microglobulin reveals the prodromes of its amyloid transition. Protein Sci. 11 487–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D.S., Bigam, C.G., Holm, A., Hodges, R.S., and Sykes, B.D. 1995. 1H, 13C and 15N random coil NMR chemical shifts of the common amino acids. I. Investigation of nearest-neighbor effects. J. Biomol. NMR 5 67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittekind, M. and Mueller, M. 1993. HNCACB, a high sensitivity 3D NMR experiment to correlate amide-proton and nitrogen resonances with the alpha and beta carbon resonances in proteins. J. Magn. Reson. B 101 201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, I., Hasegawa, K., Takahashi, N., and Naiki, H. 2001. Apolipoprotein E inhibits the depolymerization of β2-microglobulin related amyloid fibrils at a neutral pH. Biochemistry 40 8499–8507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]