Abstract

The comparative analysis of two cationic antibacterial peptides of the cathelicidin family—indolicidin and tritrypticin—enabled addressing the structural features critical for the mechanism of indolicidin activity. Functional behavior of retro-indolicidin was found to be identical to that of native indolicidin. It is apparent that the gross conformational propensities associated with retro-peptides resemble those of the native sequences, suggesting that native and retro-peptides can have similar structures. Both the native and the retro-indolicidin show identical affinities while binding to endotoxin, the initial event associated with the antibacterial activity of cationic peptide antibiotics. The indolicidin–endotoxin binding was modeled by docking the indolicidin molecule in the endotoxin structure. The conformational flexibility associated with the indolicidin residues, as well as that of the fatty acid chains of endotoxin combined with the relatively strong structural interactions, such as ionic and hydrophobic, provide the basis for the endotoxin–peptide recognition. Thus, the key feature of the recognition between the cationic antibacterial peptides and endotoxin is the plasticity of molecular interactions, which may have been designed for the purpose of maintaining activity against a broad range of organisms, a hallmark of primitive host defense.

Keywords: Indolicidin, antibacterial peptide, retro, endotoxin, plasticity of molecular interactions, primitive host defense

Every organism utilizes a complex array of mechanisms to defend itself from invading pathogens. In case of mammals, probably the most elaborate and multifaceted genetic machinery functions in a remarkably coordinated manner for host defense. In addition to the intricate adaptive immune system, mammals have also inherited an innate immune response, which works in a localized manner at the site of pathogenic invasion (Gudmundsson and Agerberth 1999; Medzhitov and Janeway, Jr. 2000; Zasloff 2002). The major component of the innate immune response involves production of peptide antibiotics that work like molecular guns and directly attack and kill the invading pathogens. Interestingly, in the context of neutralizing the foreign antigens, the immune system has provided an archetypal model for addressing the mechanistic aspects of molecular recognition. In fact, the studies involving various aspects of humoral and cellular immune systems have enormously contributed to our present understanding of the specificity and complexity of molecular recognition (Wilson and Stanfield 1994; Davies and Cohen 1996). It is anticipated that being an ancient form of the host defense, innate immunity may shed light on the development of the primitive form of molecular recognition.

A major component of the mammalian innate immunity constitutes expression of a large number of multifunctional proteinaceous effector molecules by neutrophils, which work as antibiotics after they are posttranslationally processed (Gudmundsson and Agerberth 1999). The molecular mechanisms associated with these antibiotics are expected to be relatively simple because the primary objective is to appropriately target and kill the pathogen. A diverse array of mechanisms by which peptidyl antibiotics attack the bacterial cell have been proposed. They include formation of a leakage channel across the membrane (Boman 1991), clustering at the membrane surface causing co-operative permeabilization by the carpet effect (Shai 1995), receptor-activated non-pore-forming mechanisms involving stereospecificity (Casteels and Tempst 1994), and inhibition of protein and DNA synthesis (Boman et al. 1993). The observed differences in the mechanisms of bacterial killing by peptidyl antibiotics appear to be consistent with the structural diversity among these molecules. In addition to their antibacterial activities, these molecules appear to be capable of performing several functions, such as endotoxin neutralization (Larrick et al. 1994), inhibition of tissue-degrading enzymes (Gao et al. 2000), and promotion of wound healing (Gallo et al. 1994), which are all indirectly related to the protection of the host.

We had earlier analyzed the mechanism of activation of tritrypticin (VRRFPWWWPFLRR), a cationic antibacterial peptide derived from a member of the cathelicidin precursor family (Zanetti et al. 1995; Nagpal et al. 1999). Cathelicidins belong to a larger family of cationic antibacterial peptides having two distinguishing structural features: amphipathicity and a net positive charge of at least 2 (Hancock 1997). They vary in length—from 13 to 30 residues—and show diverse sequences. The initial event common to all the cationic peptides appears to be the binding of the positively charged residues of the peptide to the negatively charged molecules exposed at the target cell surface, before permeabilization and bacterial killing (Hancock et al. 1995). We had suggested that tritrypticin undergoes a conformational transition while approaching the membrane receptor (Nagpal et al. 1999). Another cationic peptide, indolicidin (ILPWKWPWWPWRR-NH2), which is also a processed antibacterial peptide obtained from its corresponding precursor protein of the cathelicidin family appears to be functionally similar to tritrypticin (Selsted et al. 1992; Zanetti et al. 1995; Nagpal et al. 1999). The correlation of sequence homology and functional properties of indolicidin and tritrypticin led us to design a retro-analog of indolicidin. Comparison of structure–activity profiles of native and retro-indolicidin shed light on the molecular specificity in the context of primitive host defense.

Results and Discussion

Cathelicidins indolicidin and tritrypticin exhibit similar structure–activity profiles

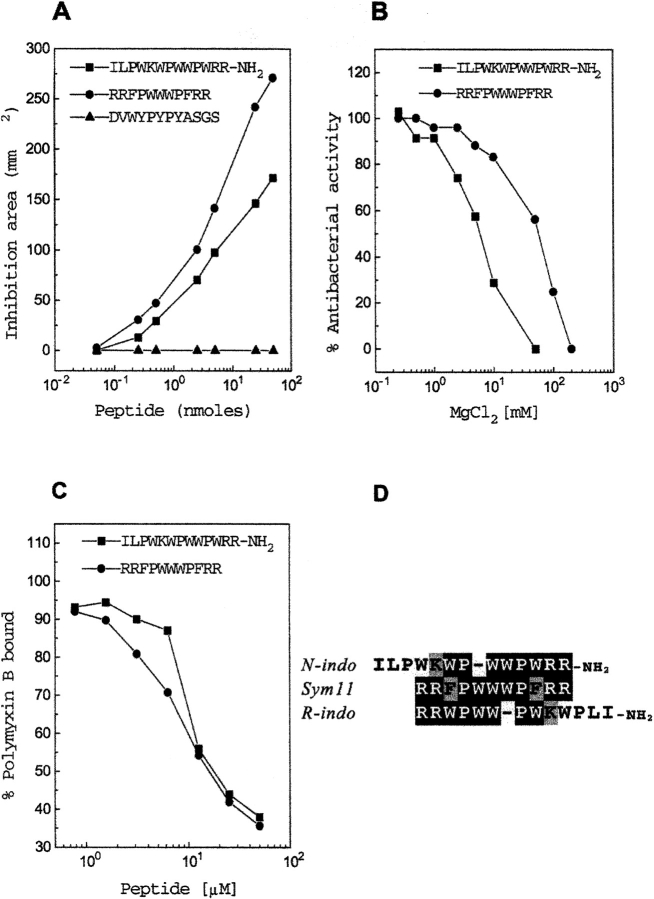

Indolicidin and tritrypticin have higher sequence similarity between them compared to the other cathelicidins as they both are proline- and tryptophan-rich cationic antibacterial peptides (Zanetti et al. 1995). It was anticipated that the similarity could be extended to their mechanism of action as well. We had earlier shown that the nearly palindromic tritrypticin when made more symmetric, as in its analog Sym11 (RRFPWWWPFRR), results in significant enhancement in activity (Nagpal et al. 1999). Also the sequence similarity of Sym11 with indolicidin was more pronounced. Therefore, the comparisons of the structure–activity profiles were made between indolicidin and Sym11 (Fig. 1 ▶). Three different functional attributes were used for this comparison: antibacterial activity, effect of divalent cations on the antibacterial activity, and the ability to competitively displace polymyxin B from endotoxin binding.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of tritrypticin analog Sym11 with indolicidin. (A) Antibacterial activity against Samonella typhimurium DVWYPYPYASGS is an unrelated peptide used as control. (B) Dose-dependent effect of MgCl2 on the antibacterial activity of the peptides against S. typhimurium. (C) Competitive displacement of dansyl polymyxin B in a dose-dependent manner by different peptides for endotoxin binding. (D) Sequence comparisons involving Sym11, indolicidin (N-indo) and retro-indolicidin (R-indo).

The antibacterial activities of Sym11 and indolicidin against Salmonella typhimurium were determined by radial diffusion assay (Fig. 1A ▶). The dose-dependent increase in the antibacterial activities of both peptides was evident, although indolicidin shows lower activity than Sym11. The control, 12mer peptide (DVWYPYPYASGS), showed no activity.

Measurement of the antibacterial activity assayed as a function of divalent cations also represents a functional measure of the cationic antibacterial peptides because they bind to the anionic sites on the membrane surface as an initial event (Hancock 1997). The effect of MgCl2 on antibacterial activities of these two peptides against S. typhimurium (Fig. 1B ▶) yields IC50 of 55 mM for Sym11 and 6 mM for indolicidin. Thus, MgCl2 can displace indolicidin more easily than Sym11 from the bacterial membrane, which is consistent with the observation that the latter has higher antibacterial activity than former.

Neutralization of LPS, which is also referred to as endotoxin, by indolicidin has been suggested earlier (Falla et al. 1996). Polymyxin B, a potent drug for endotoxin shock, is known to bind and effectively neutralize septic shock activities of LPS. It has been shown that indolicidin can displace polymyxin B competitively. The endotoxin binding of Sym11 and indolicidin were compared using in vitro polymyxin B displacement assay (Moore et al. 1986), as shown in Figure 1C ▶. It was observed that both the peptides could displace polymyxin B from endotoxin with IC50 of 18 μM and 17 μM for indolicidin and Sym11, respectively. Thus, the ability of Sym11 to displace polymyxin B from endotoxin is similar to that of indolicidin.

It is evident that the overall activity profiles of indolicidin and Sym11 are very similar in terms of different functional properties. The Sym11 analog shows better activity compared to indolicidin in the majority of the assays. This is not surprising considering that Sym11 incorporates both NT7 (RRFPWWW) and CT7 (WWWPFRR), which were independently adequate for exhibiting antibacterial activity (Nagpal et al.1999), whereas indolicidin shows similarity only with the C-terminal region of Sym11 (Fig. 1D ▶).

Functional behavior of retro-indolicidin is identical to that of native indolicidin

The homology of indolicidin with the C-terminal region of Sym11 (Fig. 1D ▶), combined with the fact that Sym11 is symmetric, indicates that the retro-analog of indolicidin (RRWPWWPWKWPLI-NH2) would also be homologous to the N-terminal region of Sym11, as seen in Figure 1D ▶. On the basis of this logic, it can be anticipated that retro-indolicidin may show functional behavior similar to native indolicidin in terms of various activity features.

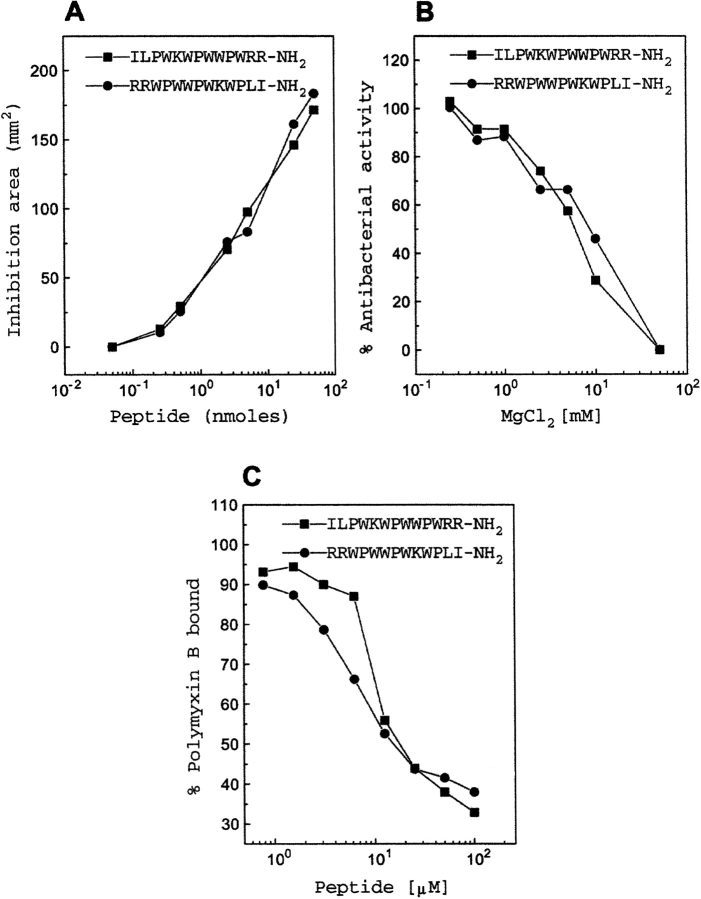

The antibacterial activity of retro-indolicidin was determined against gram-negative, as well as gram-positive, bacteria. Comparison of the antibacterial activity of the two peptides against S. typhimurium shows a dose-dependent increase in the activity of retro-indolicidin, which was practically identical to that in the case of the native peptide (Fig. 2A ▶). Comparison of the activities, by radial diffusion assay, of the two peptides against Escherichia coli and Streptococcus group A also showed similar behavior (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of indolicidin with retro-indolicidin. (A) Antibacterial activity against Salmonella typhimurium. (B) Dose-dependent effect of MgCl2 on the antibacterial activity of the peptides against S. typhimurium. (C) Competitive displacement of dansyl polymyxin B in a dose-dependent manner by different peptides for endotoxin binding.

The effect of the divalent cation (MgCl2) on the antibacterial activity against S. typhimurium of these two peptides was compared (Fig. 2B ▶). The IC50 values of 9 mM and 6 mM were observed in the case of retro-indolicidin and indolicidin, respectively. Thus, the divalent cation can displace both of the peptides with comparable efficiency from the bacterial membrane.

The functionally relevant binding of polymyxin B to endotoxin is highly specific. The competitive displacement of polymyxin B from endotoxin by retro-peptide was analyzed and compared with that of the native indolicidin (Fig. 2C ▶). It was observed that the retro-indolicidin could displace polymyxin B from endotoxin with an IC50 value of 17.5 μM. This is comparable to that of native indolicidin.

Thus, indolicidin and retro-indolicidin both show remarkable similarity in terms of various traits of activity. The observation that the retro-peptide shows a similar activity profile as that of the native peptide at a variety of different levels is intriguing. Similarity in activity of retro- and native peptides has been observed in a few other instances as well (Merrifield et al. 1995; Ido et al.1997; Pinilla et al. 1998; Vunnam et al. 1998). It was anticipated that the functional correlation between indolicidin and its retro-analog has adequate molecular basis. Diverse manifestations of activity used for comparing native indolicidin and its retro-analog shown above provide indirect functional correlation at the molecular level. To assess if functional similarities would reflect at the structural level as well, it was pertinent to analyze the direct structural interactions between indolicidin and the corresponding receptor, which is LPS in this case.

Model of the indolicidin–endotoxin binding

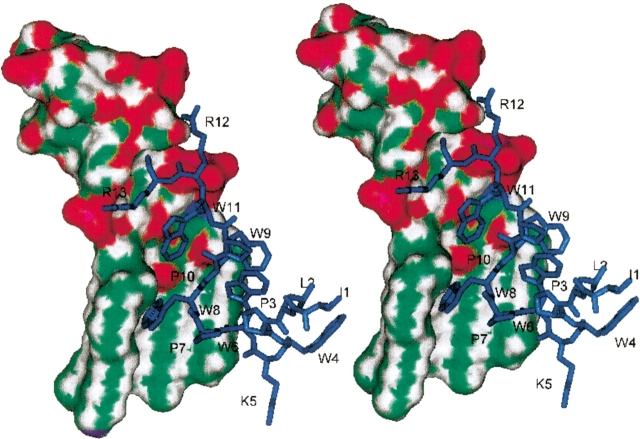

Availability of the experimentally determined three-dimensional structures of indolicidin and endotoxin enabled us to model the interaction between the two molecules in a knowledge-based manner. The solution structure of indolicidin in lipid-like medium has recently been determined (Rozek et al. 2000). Also the crystal structure of a complex of LPS with an LPS-binding protein, FhuA from E. coli, has been determined (Ferguson et al. 2000). Using these two structures, we have modeled the interaction of indolicidin with LPS. The indolicidin molecule was docked in the LPS structure using the ligand-interacting residues and stereochemistry of the LPS-binding protein as the guide. This was followed by energy minimization of the complex. The intermolecular energy was calculated to be −95.41 Kcal/mole. The energy-optimized model of the indolicidin-LPS complex is shown in Figure 3 ▶. It was observed that the two arginine residues at the N terminus of indolicidin exhibit ionic interactions with the phosphates of the LPS such that the guanidyl group of Arg 12 makes two hydrogen bonds with O6 of the diphosphate and that of the Arg 13 forms a hydrogen bond with O2 of the phosphate in LPS. The hydrophobic residues of the peptide—constituted by the three tryptophan residues—interact with the hydrophobic fatty acid tails of the LPS, which essentially wrap around this part of the peptide.

Fig. 3.

Model of indolicidin–LPS binding. Stereoscopic diagram of the complex of LPS with indolicidin. LPS is shown as Connolly surface and is marked as follows: green, carbon; red, oxygen; blue, nitrogen; white, hydrogen; purple, phosphates. Indolicidin is shown in navy blue stick with residues marked.

The structural interactions observed in the model of indolicidin-LPS complex correlate well with the binding interactions in the crystal structure of the complex of the LPS-binding protein bound to LPS (Ferguson et al. 2000), thereby supporting our model. Thus, the model of the indolicidin-LPS complex shows that the binding is facilitated by salt bridges and hydrophobic interactions. The polar-head groups of LPS and the Arg side chains of the peptide are involved in the salt bridges, and the three tryptophan residues of the indolicidin and the fatty acid chains of the LPS are predominantly involved in the hydrophobic association.

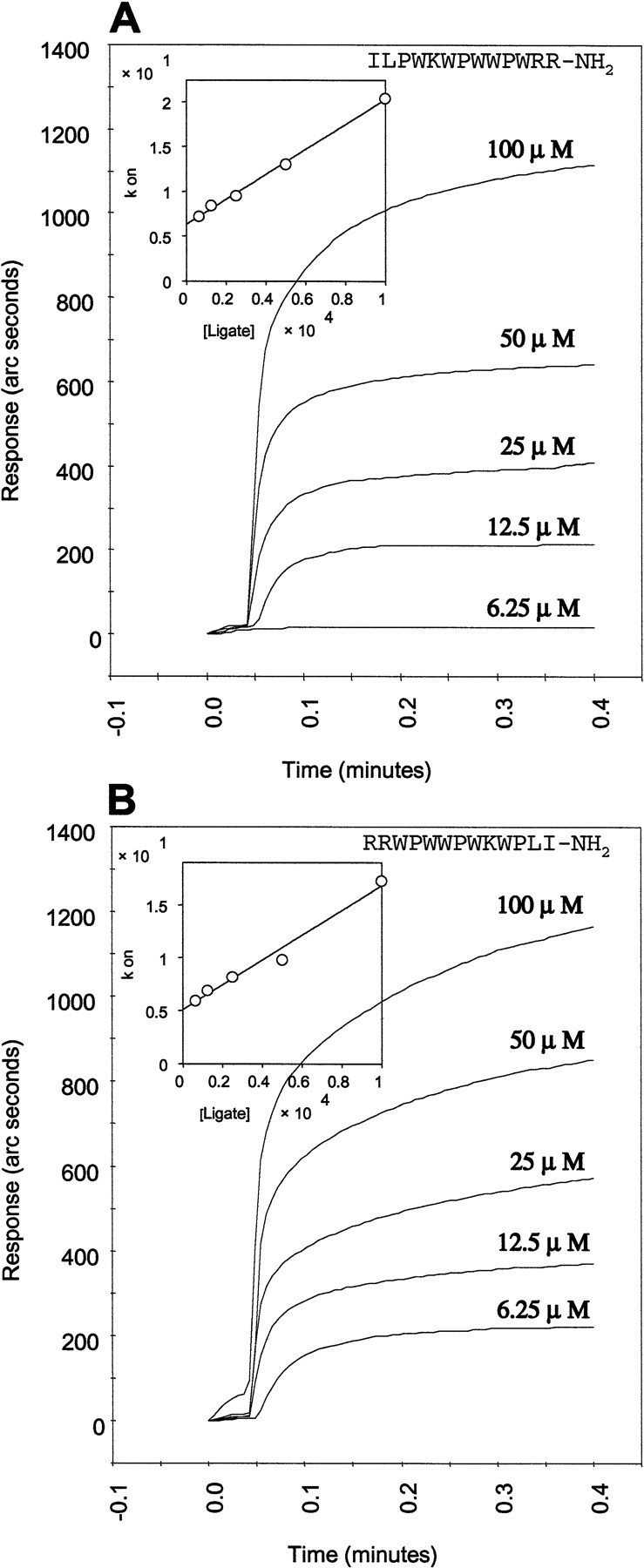

The direct affinity measurements of the LPS binding with indolicidin were consistent with the observed structural features in the above model. The anti-endotoxin activity of indolicidin assayed by polymyxin B displacement from LPS can be directly probed using an affinity biosensor and correlated with the direct interactions between the LPS and the peptide. Binding of indolicidin to immobilized LPS was assayed by IAsys Auto Plus. Figure 4A ▶ shows the sensograms of the interaction of indolicidin with LPS at different concentrations. It is apparent that the LPS–indolicidin binding, with the KD value of 45.2 μM, is favorable. The low value of the dissociation constant correlates well with the nature of the binding interactions of the indolicidin to LPS, mediated by salt bridges and hydrophobic interactions, as described in the structural model.

Fig. 4.

LPS affinity measurements of (A) indolicidin and (B) retro-indolicidin. The sensogram representing the binding signal of the peptide to the immobilized LPS is shown as a function of peptide concentration. The inset shows the linear fit of the Kon with the peptide concentration.

Comparison of the LPS binding of retro-indolicidin with that of indolicidin was also carried out (Fig. 4B ▶). It is evident that the KD value of retro-peptide, calculated on the basis of the sensograms, was almost identical (43.6 μM) to that of the native peptide. The Kon and the Koff values were also comparable for the two peptides (Table 1) indicating that the kinetics of binding are also similar in the two cases. This implies that the nature of interactions involved in the binding of the retro-peptide to the LPS is similar to that involving the native peptide. This would necessitate similarity of structures between indolicidin and its retro-analog. It is intriguing how a retro-sequence corresponding to a bioactive peptide will resemble its native counterpart.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of binding of peptides to LPS at 25°C

| Peptide | kass × 10−3(M−1 s−1) | kdiss(s−1) | KD × 106(M) |

| Indolicidin | 1.391 | 0.063 | 45.2 |

| Retro-indolicidin | 1.171 | 0.051 | 43.5 |

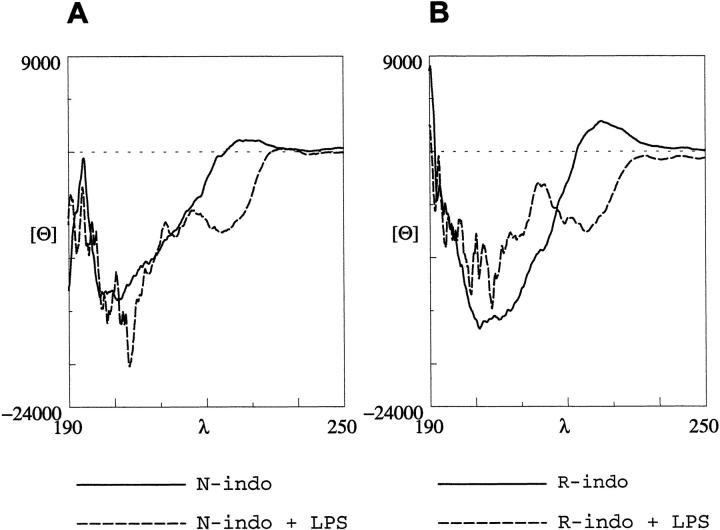

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of native and retro-indolicidin in free and LPS-bound forms were analyzed (Fig. 5 ▶). In aqueous solution, the CD spectra of indolicidin, as well as retro-indolicidin, are characterized by a broad negative band at 200 nm. Both the peptides also show a positive band at 228 nm, which has been attributed to the conformational propensities of tryptophan side chains of indolicidin (Woody 1985). A transition from a small positive to a significant negative band at 228 nm is evident on LPS binding, indicating reorientation of the tryptophans. The negative band at 228 nm on LPS binding can be attributed to the constrained conformations of tryptophan residues while interacting with the fatty acid region of LPS (Fig. 3 ▶), similar to that observed in the tritrypticin analogs having β-turn conformation constrained through intramolecular interactions (Nagpal et al 1999).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of circular dichroism profiles of (A) indolicidin and (B) retro-indolicidin, in free and LPS-bound forms.

Plasticity is a critical feature of indolicidin–LPS binding

We have established the functional similarity between the two peptides, indolicidin and its retro-analog. Also the gross conformational characteristics of retro-indolicidin resemble the native indolicidin, as seen from the CD data (Fig. 5 ▶) and consistent with the secondary structural propensities. The CD profiles of indolicidin and retro-indolicidin bound to LPS also show remarkable similarity. This functional and structural equivalence should be manifested in the interaction of the retro-peptide with LPS. It is evident from the model above that indolicidin binds to LPS through ionic and hydrophobic interactions. It should be possible to juxtapose the retro-peptide with LPS, such that its interactions mimic the native indolicidin. The long side chains of arginine residues and the relatively bulky head group of LPS provide significant flexibility so that the ionic interactions are optimized irrespective of the orientation in which the peptide is presented. Similar optimization opportunities exist for hydrophobic interactions around the tryptophan residues due to the flexibility of the fatty acid chains. Therefore, the most likely mode of recognition of receptors by indolicidin or the retro-peptide could be through a dumbbell-shaped structure with hydrophobic residues clustered on one side and the ionic residues clustered on the other. In such a structure, the hydrophobic cluster and the cationic cluster of residues would be positioned appropriately at a specific distance, such that they complement the structural features while binding to the corresponding receptor on the membrane surface. Such a model gives enormous leeway, in terms of structural design, of specifically presenting the peptides to the receptor.

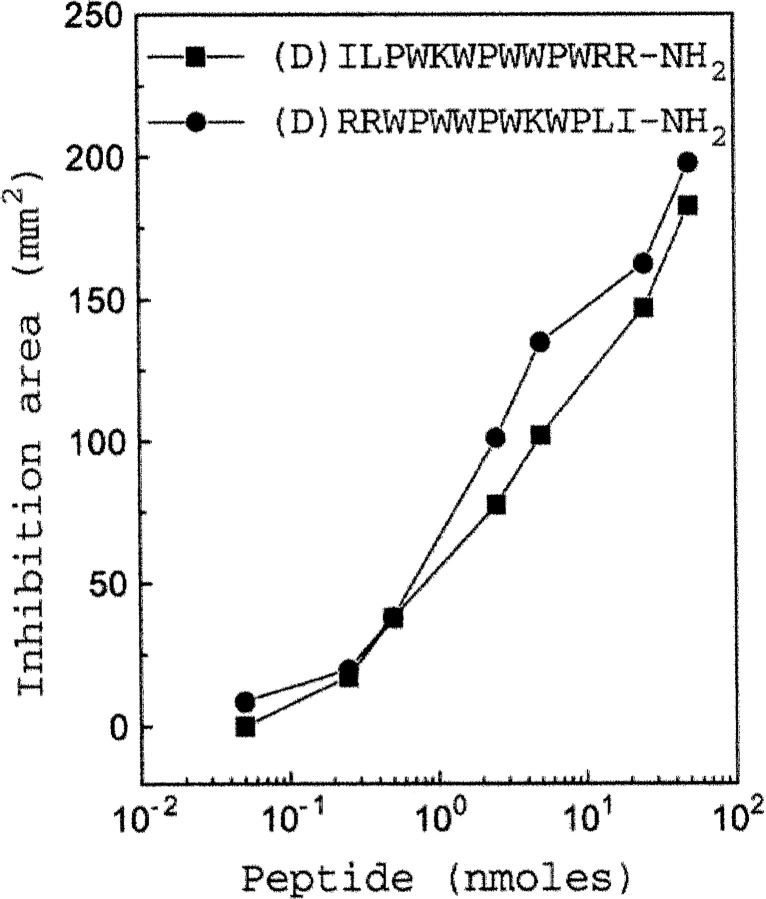

If reversal of the sequence does not have any problem in terms of achieving the functionally acceptable topology, inversion of the sequence (changing the handedness) should also be able to retain the functional topology. To test this hypothesis, we have analyzed antibacterial activities of the D-analogs (inverso) of indolicidin and retro-indolicidin against S. typhimurium by radial diffusion assay in a dose-dependent manner. As shown in Figure 6 ▶, both of them show similar activities. Thus, as expected, the antibacterial activities of the D-analogs were also comparable to their L-counterparts.

Fig. 6.

The D-analogs of indolicidin and retro-indolicidin show similar functional behavior as the corresponding L-peptides. Comparison of the antibacterial activities against Salmonella typhimurium of the two peptides is plotted in a dose-dependent manner.

Conclusion

The biologically relevant interactions ought to be specific at molecular level. It is obvious that both indolicidin and Sym11 show antibacterial activities, as well as LPS binding, in various chemically distinct forms such as native, retro, inverso or retro and inverso together. However, this does not imply that the two peptides bind to the membrane receptor in a nonspecific manner. Both the hydrophobic clustering and the electrostatic interactions accompanied by the relative flexibility in the peptide molecule would provide certain leeway within this specificity (Thomas et al. 1998). In other words, specificity of indolicidin binding to the membrane surface during the early event of recognition may be achieved by the appropriate juxtaposition of the hydrophobic and the cationic residues so as to match a complementary site on the receptor. The hydrophobic interactions involving the liquid crystalline nature of fatty acid chains of LPS while interacting with the aromatic residues of indolicidin and the relatively flexible and long arginine side chains of the peptide-forming salt bridges with the phosphate-head groups relate to the plasticity of indolicidin–LPS binding. This plasticity enables incorporation of otherwise drastic variations such as retro and inverso (D-analogs) without loss of activity. This relatively simple mode of recognition—associated with the innate immune system—may represent the early stages in the evolution of molecular recognition processes.

Thus, the key to the interaction between the cationic antibacterial peptides and LPS, as also inferred from their antibacterial activity, is the plasticity of molecular interactions. This form of plasticity has been shown to be a functional requirement in many instances (Keenan et al. 1998; Chen and Sigler 1999; Stock et al. 1999; Manivel et al. 2000). In the case of indolicidin, in which the binding affinities are very much in the physiological range, plasticity may be linked to the recognition of gross submolecular patterns, an issue that might have been of critical significance for a primitive form of host defense. The conformational flexibility associated with the residues of indolicidin and the fatty acid chains of LPS contribute to the plasticity of binding. Plasticity of interactions also ensures the recognition of a broad spectrum of organisms, which would be a necessity in primitive host defense.

Materials and methods

HMP (4-hydroxymethyl phenoxymethyl polystyrene), rink amide [4-(2`,4`-dimethoxyphenyl-Fmoc-aminomethyl)-phenoxy methyl-polystyrene] resins, solvents and reagents used for synthesis were supplied by Applied Biosystems, Inc. Fmoc amino acid derivatives were procured from Bachem Feinchemikalein AG. Biotin cuvettes were obtained from IAsys Autoplus, Affinity Sensors. LPS of wild S. typhimurium was obtained from Difco Laboratories. Other chemicals were purchased from Sigma.

The gram-negative bacterial strains S. typhimurium 3261 PNP2 Gro A mutant and E. coli BL21 (αD3) and Streptococcus group A were used for radial diffusion assay. Agarose I (biotechnology grade) was obtained from Amresco and tryptic soy broth (TSB) was from Himedia Laboratories.

Peptide synthesis, purification, and characterization

Indolicidin, tritrypticin, and their analogs were synthesized by solid phase method using an automated peptide synthesizer, model 431A from Applied Biosystems, Inc., employing standard Fmoc methodology. The peptides were cleaved from the resin by treatment with TFA/thioanisole/phenol/water/EDT in the ratio as recommended by Applied Biosystems, Inc. The crude peptides were purified using a C-18 column (Deltapak, 100 Å, 15 μ, spherical, 19 × 300 mm, Waters) and peptide purity was verified using a C-18 analytical column (Deltapak, 300 Å, 15 μ, spherical, 7.8 × 300 mm, Waters). Characterization was performed by molecular mass determination using a single Quadruple mass analyzer (Fisons Instruments).

Antibacterial assay

The radial diffusion assay was performed using double-layered agarose as described previously (Nagpal et al. 1999).

Effect of cation on antibacterial activity

Indolicidin, retro-indolicidin and Sym11 were tested for their antibiotic activity against S. typhimurium in the presence of MgCl2 by radial diffusion assay. Different concentrations of MgCl2 were mixed with the underlayer agar composed of 1% agarose, 0.03% TSB, and 0.02% tween 20 in 10 mM PB at pH 7.4, which is inoculated with ∼1 million bacterial cells. This mixture was poured into a round petri plate; 5 μL of 1 mM peptide in triplicate was added in each well made in the underlayer. The plates were incubated for 3 h at 37°C. The overlay agar containing 1% agarose in 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 and 3% TSB was then poured over it and further incubated at 37°C for 18 to 24 h. The diameter of the clear zone surrounding the wells was measured. The inhibition zone obtained with peptide in the absence of cation was considered as 100% antibacterial activity.

Dansyl polymyxin B displacement assay

Dansyl polymyxin B, a fluorescent derivative of polymyxin B, was prepared by condensing polymyxin B sulphate with dansyl chloride as described by Schindler and Teuber (1975). The comparative binding affinity of various antibiotic peptides for endotoxin were investigated by dansyl polymyxin B displacement assay (Moore et al. 1986). The data was expressed as the percent dansyl polymyxin B bound to the endotoxin as a function of peptide concentration. The sample concentration resulting in 50% displacement (IC50) of dansyl polymyxin B was thus determined from the graph.

Endotoxin binding

Binding kinetics were determined by using IAsys Auto Plus, Affinity Sensor. LPS was biotinylated with NHS-LC-biotin as described by de Haas et al. (1998). Biotinylated LPS pretreated with EDTA and sodium-desoxycholate as reported earlier (de Haas et al. 1998) was immobilized onto a streptavidin bound on a biotin-coated surface at a concentration of 0.25 mg/mL in 10 mM phosphate buffer saline at pH 7.4. Approximately 600 arc sec of endotoxin were immobilized (600 arc sec corresponds to an immobilized protein concentration of 1 ng/mm2). The unreacted sites were blocked with d-biotin. All measurements were carried in 10 mM HANK'S balanced salt solution. For the determination of association rate constants, the antibiotic peptides (100 μM–6.25 μM) in the same buffer were used. Dissociation rate constants were measured by replacing the sample by buffer. Following analyte binding, the surface was regenerated with 10 mM GlyHCl at pH 2. Kinetics of the interaction of the peptides with endotoxin were analyzed by nonlinear regression using the FAST fit software package supplied with the IAsys instrument.

Circular dichroism

The CD experiments were carried out on a JASCO 710 spectropolarimeter with a 1-nm bandwidth at 0.1-nm resolution and a 1-sec response time using a 10mm path-length cell; 20–25 scans with a speed of 200 nm/min in the range of 250–190 nm were accumulated and averaged. The spectra were recorded at the peptide concentration of 10 μM in 10-mM phosphate buffer (pH 7) at 25°C. Results were expressed as mean residue molar ellipticity in deg cm /dmol.

Computational analysis

BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990) was used for sequence analyses using the Protein Data Bank (PDB; Berman et al. 2000). The MSI software INSIGHT II (Molecular Simulations, Inc.) was used on an OCTANE workstation (Silicon Graphics) for model building, analysis, and display of structural data.

The coordinates of the indolicidin were obtained from the NMR structure of indolicidin bound to dodecylphosphocholine micelles (PDB code 1G89) and those of the LPS were from the crystal structure of a complex of LPS with FhuA (PDB code 1QFG), for the molecular docking analysis. The indolicidin was docked in the lipopolysaccharide using the DOCKING module in INSIGHT II. This was followed by energy-based refinement of the model in 100 steps of steepest descent minimization, which was followed by conjugate gradient minimization until convergence. The energy minimization was carried out using the DISCOVER module. The distance-dependent dielectric constant was used during these calculations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India. We thank Dr. Kanury Rao for useful discussions. The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

LPS, lipopolysaccharide

retro, peptide sequence with amino acids in reverse order

inverso (D-analog), peptide sequence with amino acids consisting of opposite-handedness

retro-inverso, peptide sequence with amino acids consisting of opposite-handedness in reverse order

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.0211602.

References

- Altschul, S.F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E.W., and Lipman, D.J. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman, H.M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T.N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I.N., and Bourne, P.E. 2000. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acid Res. 28 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boman, H.G. 1991. Antibacterial peptides: Key components needed in immunity. Cell 65 205–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boman, H.G., Agerberth, B., and Boman, A. 1993. Mechanisms of action on Escherichia coli of cecropin P1 and PR-39, two antibacterial peptides from pig intestine. Infect. Immun. 61 2978–2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casteels, P. and Tempst, P. 1994. Apidaecin-type peptide antibiotics function through a non-poreforming mechanism involving stereospecificity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 199 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. and Sigler, P.B. 1999. The crystal structure of a GroEL/peptide Complex: Plasticity as a basis for substrate diversity. Cell 99 757–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, D.R. and Cohen, G.H. 1996. Interactions of protein antigens with antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93 7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haas, C.J., Haas, P.J., van Kessel, K.P., and van Strijp, J.A. 1998. Affinities of different proteins and peptides for lipopolysaccharide as determined by biosensor technology. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 252 492–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falla, T.J., Karunaratne, D.N., and Hancock, R.E.W. 1996. Mode of action of the antimicrobial peptide indolicidin. J. Biol. Chem. 271 19298–19303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, A.D., Welte, W., Hofmann, E., Lindner, B., Holst, O., Coulton, J.W., and Diederichs, K. 2000. A conserved structural motif for lipopolysaccharide recognition by procaryotic and eucaryotic proteins. Structure 8 585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, R.L., Ono, M., Povsic, T., Page, C., Eriksson, E., Klagsbrun, M., and Bernfield, M. 1994. Syndecans, cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans, are induced by a proline-rich antimicrobial peptide from wounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 91 11035–11039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y., Lecker, S., Post, M.J., Hietaranta, A.J., Li, J., Volk, R., Li, M., Sato, K., Saluja, A.K., Steer, M.L., Goldberg, A.L., and Simons, M. 2000. Inhibition of ubiquitin-proteasome pathway-mediated I κ B α degradation by a naturally occurring antibacterial peptide. J. Clin. Invest. 106 439–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson, G.H. and Agerberth, B. 1999. Neutrophil antibacterial peptides, multifunctional effector molecules in the mammalian immune system. J. Immunol. Methods 232 45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, R.E.W. 1997. Peptide antibiotics. Lancet 349 418–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, R.E.W., Falla, T., and Brown, M. 1995. Cationic bactericidal peptides. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 37 135–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ido, Y., Vindigni, A., Chang, K., Stramm, L., Chance, R., Heath, W.F., DiMarchi, R.D., Di Cera, E., and Williamson, J.R. 1997. Prevention of vascular and neutral dysfunction in diabetic rats by C-peptide. Science 277 563–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, R.J., Freymann, D.M., Walter, P., and Stroud, R.M. 1998. Crystal structure of the signal sequence binding subunit of the signal recognition particle. Cell 94 181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrick, J.W., Hirata, M., Zheng, H., Zhong, J., Bolin, D., Cavaillon, J.-M., Warren, H.S., and Wright, S.C. 1994. A novel granulocyte-derived peptide with lipopolysaccharide-neutralizing activity. J. Immunol. 152 231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manivel, V., Sahoo, N.C., Salunke, D.M., and Rao, K.V.S 2000. Maturation of an antibody response is governed by modulations in flexibility of the antigen-combining site. Immunity 13 611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov, R. and Janeway, Jr., C. 2000. Innate immunity. N. Engl. J. Med. 3 338–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrifield, R.B., Juvvadi, P., Andreu, D., Ubach, J., Boman, A., and Boman, H.G. 1995. Retro and retroenantio analogs of cecropin-melittin hybrids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 92 3449–3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.A., Bates, N.C., and Hancock, R.E.W. 1986. Interaction of polycationic antibiotics with Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide and lipid A studied by using dansyl-polymyxin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 29 496–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagpal, S., Gupta, V., Kaur, K.J., and Salunke, D.M. 1999. Structure-function analysis of tritrypticin, an antibacterial peptide of innate immune origin. J. Biol. Chem. 274 23296–23304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinilla, C., Appel, J.R., Campbell, G.D., Buencamino, J., Benkirane, N., Muller, S., and Greenspan, N.S. 1998. All D-peptides recognized by an anti-carbohydrate antibody identified from a positional scanning library. J. Mol. Biol. 283 1013–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozek, A., Friedrich, C.L., and Hancock, R.E.W. 2000. Structure of the bovine antimicrobial peptide indolicidin bound to dodecylphosphocholine and sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles. Biochemistry 3915765–15774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler, P.R.G. and Teuber, M. 1975. Action of polymyxin B on bacterial membranes: Morphological changes in the cytoplasm and in the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 8 94–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selsted, M.E., Novotny, M.J., Morris, W.L., Tang, Y.-Q., Smith, W., and Cullor, J.S. 1992. Indolicidin, a novel bactericidal tridecapeptide amide from neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 267 4292–4295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shai, Y. 1995. Molecular recognition between membrane-spanning polypeptides. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20 460–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock, D., Leslie, A.G.W., and Walker, J.E. 1999. Molecular architecture of the rotary motor in ATP synthase. Science 286 1700–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C.J., Gangadhar, B.P., Surolia, N., and Surolia, A. 1998. Kinetics and mechanism of the recognition of endotoxin by polymyxin B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 12428–12434. [Google Scholar]

- Vunnam, S., Juvvadi, P., Rotondi, K.S., and Merrifield, R.B. 1998. Synthesis and study of normal, enantio, retro, and retroenantio isomers of cecropin A-melittin hybrids, their end group effects and selective enzyme inactivation. J. Peptide Res. 51 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, I.A. and Stanfield, R.L. 1994. Antibody–antigen interactions: New structures and new conformational changes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 4 857–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody, R.W. 1985. Circular dichroism of peptides. In The peptides: Analysis, synthesis, biology (ed. V.J. Hruby), Vol. 7, pp. 15–114. Academic Press, Inc., London.

- Zanetti, M., Gennaro, R., and Romeo, D. 1995. Cathelicidins: A novel protein family with a common proregion and a variable C-terminal antimicrobial domain. FEBS Lett. 374 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zasloff, M. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]