Abstract

Many therapeutic proteins require storage at room temperature for extended periods of time. This can lead to aggregation and loss of function. Cyclodextrins (CDs) have been shown to function as aggregation suppressors for a wide range of proteins. Their potency is often ascribed to their affinity for aromatic amino acids, whose surface exposure would otherwise lead to protein association. However, no detailed structural studies are available. Here we investigate the interactions between human growth hormone (hGH) and different CDs at low pH. Although hGH aggregates readily at pH 2.5 in 1 M NaCl to form amorphous aggregates, the presence of 25 to 50 mM of various β-CD derivatives is sufficient to completely avoid this. α- and γ-CD are considerably less effective. Stopped-flow data on the aggregation reaction in the presence of β-CD are analyzed according to a minimalist association model to yield an apparent hGH-β-CD dissociation constant of ∼6 mM. This value is very similar to that obtained by simple fluorescence-based titration of hGH with β-CD. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies indicate that β-CD leads to a more unfolded conformation of hGH at low pH and predominantly binds to the aromatic side-chains. This indicates that aromatic amino acids are important components of regions of residual structure that may form nuclei for aggregation.

Keywords: Human growth hormone, cyclodextrins, stopped-flow kinetics, aggregation, aromatic amino acids

Cyclodextrins (CDs) are the primary products of the degradation of starch by CD glucosyltransferases. They are circular oligosaccharides composed of α-(1→4)-linked α-d-glucosyl units (Frömming and Szejtli 1994; Szejtli and Osa 1996; Szejtli 1998; Easton and Lincoln 1999). The most common and industrially useful CDs are α-, β-, and γ-CD, which consists of six, seven, and eight glucose units, although larger CDs are known (Larsen 2001). CDs can be visualized as toroidal, hollow, truncated cones with hydrophilic rims crowned by OH-6 primary groups on the narrow rim and OH-2 and OH-3 secondary hydroxyl groups on the wide rim. In contrast, the internal cavity is hydrophobic, lined with H-3, H-5, and H-6 hydrogens and O-4 ether oxygens (Szejtli 1998). Such an arrangement leads to a water-soluble molecule that can accommodate hydrophobic moieties in its cavity. In this way, CDs can bind to hydrophobic parts of the protein surface, leading to a hydrophilic covering layer, which increases the solubility of the protein. Binding of aromatic side-chains may explain the ability of CDs to reduce protein aggregation and increase the shelf-life of therapeutic proteins, such as growth hormones (Hagenlocher and Pearlman 1989; Brewster et al. 1991; Charman et al. 1993) and insulin (Banga and Mitra 1993). Similar "chaperoning" effects have been seen for carbonic anhydrase (Sharma and Sharma 2001) and freeze-dried β-galactosidase (Branchu et al. 1999). The small dissociation constants of the CD toward aromatic amino acids generally lie in the high millimole range but can be significantly lower for nonpeptide groups (Cooper 1992). Larger CDs are not likely to bind aromatic side-chains, but can be used to remove detergents from solubilized protein-detergent complexes (Machida et al. 2000). In addition, CDs have attracted attention as drug delivery systems for peptides and protein drugs (Irie and Uekama 1999) and as stabilizers that reduce chemical degradation of peptides (Sigurjonsdottir et al. 1999). A corollary of the antiaggregation properties of the CD is that it also destabilizes the native state, simply because it binds more strongly to aromatic amino acids in the unfolded state than in the native state (Cooper 1992).

β-CD is commercially the most widely used CD because of its ready availability, low price, and outstanding ability to accommodate hydrophobic molecules (e.g., poorly water soluble drugs) either completely or in part (Connors 1997). To overcome its low solubility in water (∼15 mM), β-CD is commonly derivatized, for example, with glucose, maltose, methyl, or hydroxypropyl groups (Szejtli1988; Frömming and Szejtli 1994; Jicsinszky et al. 1996).

Here we describe a study of the interaction between CDs and proteins, using human growth hormone (hGH) as a model system. This single-domain 191-residue protein forms a four-helical bundle (Chantalat et al. 1995). In the native state, hGH exposes a large number of aromatic amino acids, which enhance its tendency to misfold and aggregate during production. To provide a convenient assay for aggregation, we exploit the fact that hGH populates a partially folded A-state at low pH (Abildgaard et al. 1992), with native-like secondary structure but loss of tertiary structure. This state is very susceptible to aggregation in the presence of NaCl. We show that this aggregation can be prevented by cyclodextrins, determine apparent dissociation constants for the reaction, and analyze structural aspects of the interaction by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR).

Results

hGH forms a partially folded state at low pH that is prone to aggregation

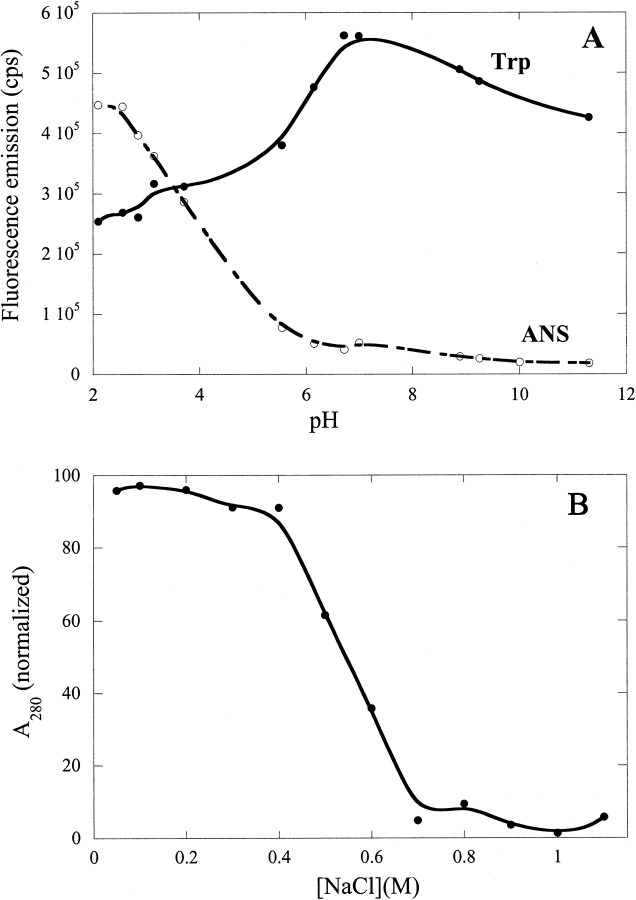

Previous studies have identified a partially folded state of hGH at low pH (Abildgaard et al. 1992; DeFelippis et al. 1995) with native-like secondary structure but reduced tertiary interactions. In support of this, we find that lowering the pH below 5 leads to a very significant increase in the binding of 1,8-anilino-naphthalene-sulfonic acid (1,8-ANS) and to a decrease in the fluorescence of the single Trp residue (Fig. 1A ▶), whereas there is no significant change in the circular dichroism signal over this pH range (data not shown). 1,8-ANS, whose intrinsic fluorescence signal increases significantly in hydrophobic environments, is used as a probe for partially folded states, which typically expose contiguous patches of hydrophobic residues (Engelhard and Evans 1995). Furthermore, this state precipitates when we add NaCl (Fig. 1B ▶). Above ∼0.8M NaCl, essentially all hGH is precipitated and can be spun down. According to Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, the precipitate is not structurally distinct from the A-state (data not shown) and can be redissolved in the absence of NaCl.

Fig. 1.

(A) Binding of the fluorescent probe 1,8-anilino-naphthalene-sulfonic acid (ANS) to human growth hormone (hGH) as a function of pH in the absence of salt. The increase in ANS fluorescence at low pH, together with the accompanying decrease in Trp fluorescence, supports the accumulation of a partially folded A-state. The solid lines are smoothing curves intended to guide the eye. (B) NaCl- aggregation of hGH at pH 2.5. 22 μM hGH were incubated with 0 to 1.1 M NaCl at 25°C for 1 h and spun down at 14,000 rpm for 15 min, and the A280 of the supernatant was measured. The solid lines are smoothing curves.

Aggregation of hGH can be suppressed by CDs

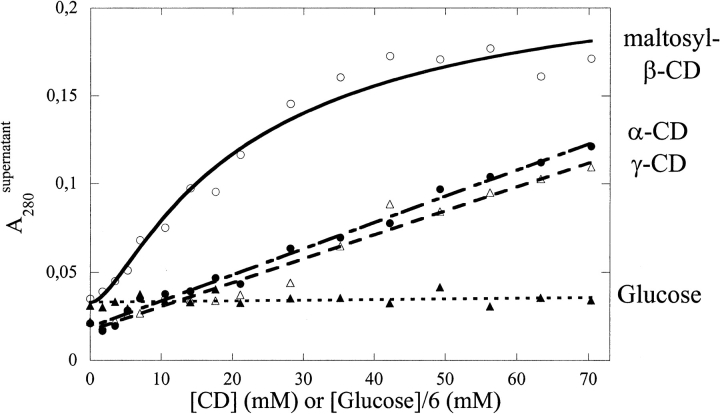

Incubation of hGH aggregates with increasing concentrations of various CDs leads to the disappearance of aggregates (Fig. 2 ▶). This is not a simple solvent effect but requires the presence of the hydrophobic CD cavity, because glucose at similar concentrations (w/v) had no effect. To obtain a quantitative but model-independent estimate for the solubilization efficacy of the various CDs, we use the plots in Figure 2 ▶ to visually determine [CD]50%, the CD concentration at which half the hGH is solubilized (Table 1). For most of the β-CD derivatives—namely, hydroxy-propyl-β-CD (HP-βCD), glycosyl-β-CD, and sulfobutyl-ether-β-CD—[CD]50% is several-fold lower than for α-CD and γ-CD. There are two exceptions, namely, sulfated CD and monoacetyl-CD, which are completely unable to prevent aggregation of hGH.

Fig. 2.

Solubilization of hGH by various cyclodextrins (CDs) at pH 2.5 in 1 M NaCl. Glucose is included as a control to show that the reaction is not a simple solvent effect but requires the presence of a CD cavity. The concentration of glucose is sixfold higher than indicated on the X-axis to facilitate comparison with the CDs.

Table 1.

Solubilization of hGH by different cyclodextrins (CDs) at pH 2.5 in 1 M NaCl

| CD | [CD]50% (mM)a |

| α-CD | 59 |

| γ-CD | 68 |

| Hydroxypropyl-CD | 19 |

| Mono-glycosyl-β-CD | 13 |

| Mono-maltosyl-β-CD | 16.5 |

| Captisol (Sulfobutyl-ether-β-CD) | 32 |

| Sulfated β-CD (5–9 SO42− per β-CD) | No effect |

| Monoacetyl-CD | No effect |

| Glucose (control) | No effect |

a The cyclodextrin concentration at which 50% of human growth hormone aggregates. Error, ≈10%.

Visible aggregation may also be induced at pH 7.0 by prolonged incubation at elevated temperatures (e.g., several days at 65°C). This aggregation is completely suppressed by the presence of HP-βCD (data not shown). However, the acid state of hGH provides a more convenient and accessible model system to investigate the ability of CDs to suppress aggregation.

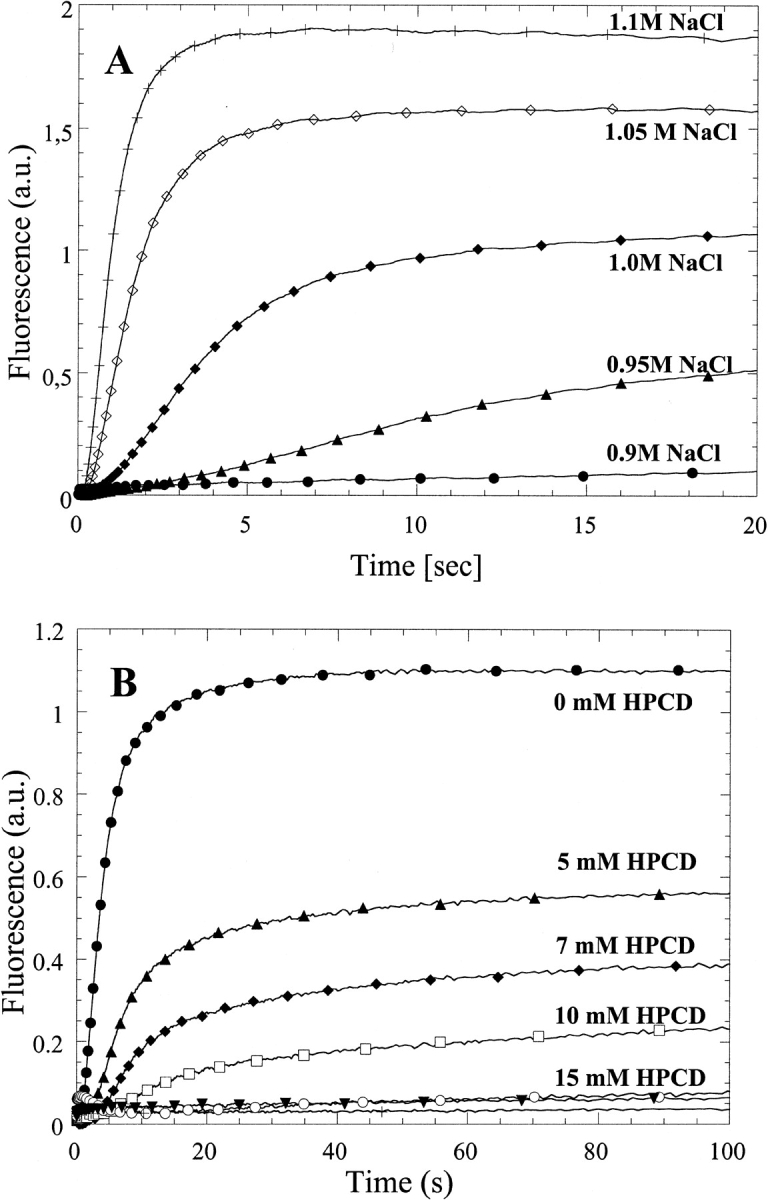

Aggregation of hGH can be followed by stopped-flow kinetics to derive apparent dissociation constants for binding

To investigate the mechanism of aggregation and its prevention by CDs, we have performed stopped-flow experiments in which hGH was mixed with NaCl at pH 2.5. The reaction is followed by fluorescence, which also reports on the light scattering caused by aggregation. There is a very substantial change in the rate of aggregation between 0.9 and 1.1 M NaCl (Fig. 3A ▶), but in all cases, there is a clear lag phase before an increase in apparent fluorescence. The increase in fluorescence involves a fast and a slow relaxation phase, with ∼85% and 15% of the total amplitude change, respectively. The lag phase and fast phase are also seen when the reaction is monitored by the change in fluorescence anisotropy (data not shown), but the slow phase disappears. The lag phase indicates that an initial conformational change, which is not visible by fluorescence, has to occur before aggregation can occur. Further, aggregation appears to be a multistep process, in which the major changes in tertiary interactions, possibly forming an "aggregation nucleus," occur in the fast step, and the slow step probably represents subsequent build-up of aggregates based on this nucleus (involving fewer conformational changes).

Fig. 3.

(A) Increase in apparent fluorescence on mixing hGH with increasing concentrations of NaCl at pH 2.5. (B) As in A but in 1.0 M NaCl and 0 to 25 mM hydroxy-propyl-β-CD (HPCD).

A dramatic reduction in the amount of light scattering is observed when the reaction is repeated at 1 M NaCl in the presence of increasing concentrations of HP-βCD (Fig. 3B ▶). HP-βCD leads to an increase in the length of the lag phase and a decrease in the subsequent aggregation steps. Increasing concentrations of CD also increase the viscosity of the solution from 1.12 (0 mM HP-βCD) to 1.28 centipoise (20 mM HP-βCD). However, control experiments with glycerol instead of HP-βCD show that viscosity does not affect the aggregation kinetics in this range (data not shown).

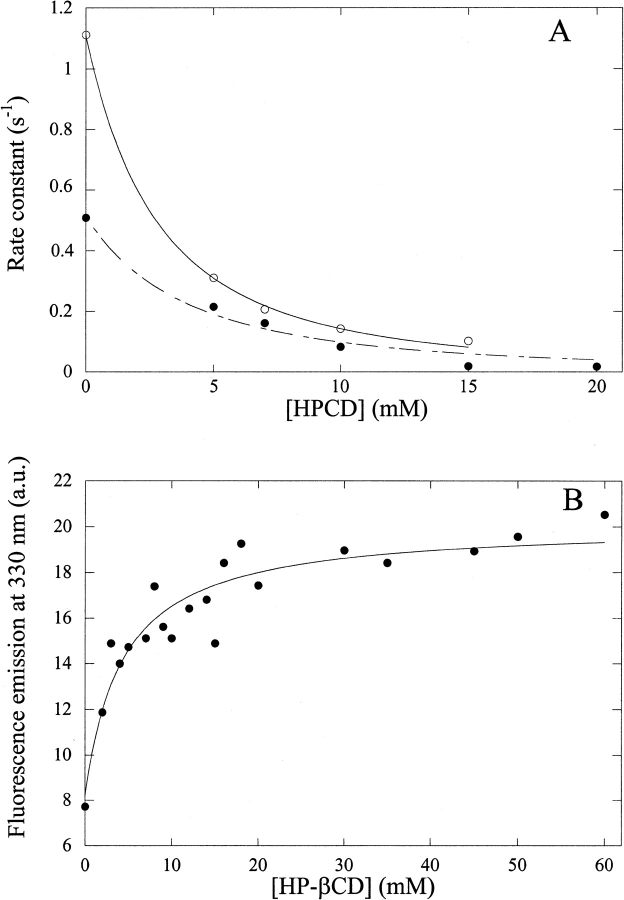

When the data are fitted to a simple aggregation model (see Materials and Methods) using the lag time and fast aggregation rate, apparent dissociation constants of 5.6 ± 0.2 and 7.8 ± 1.0 mM are obtained (Fig. 4A ▶, Table 2). To corroborate these dissociation constants by other means, we have also measured the binding of HP-βCD to hGH directly by titrating hGH with HP-βCD at pH 2.5 in the absence of NaCl. This gives rise to an increase in Trp fluorescence with an apparent dissociation constant of 4.6 ± 1.2 mM (Fig. 4B ▶), in reasonable agreement with the above data. The KD determined by direct titration may in fact be an overestimate if HP-βCD preferentially binds to a more unfolded form that is less populated in the absence of HP-βCD (see below). Estimates for dissociation constants between β-CD and free aromatic amino acids lie in the same range as the values determined in this work, namely, ∼10 to 20 mM (Horsky and Pitha 1994).

Fig. 4.

(A) The fast rate of aggregation of hGH (empty circles) and the reciprocal of the lag time (filled circles) at pH 2.5 in 1 M NaCl fitted to Equation 1. This yields an apparent dissociation constant of 5.6 ± 0.2 and 7.8 ± 1.0 mM, respectively. (B) Titration of 20 μM hGH with hydroxy-propyl-β-CD (HP-βCD) in 25 mM Gly (pH 2.5), followed by tryptophan fluorescence (excitation, 295 nm; emission, 330 nm). The data are fitted to a simple binding curve to yield an apparent dissociation constant of 4.6 ± 1.2 mM.

Table 2.

Apparent dissociation constants between HP-βCD and hGH at pH 2.5

| Method | Apparent Kd (mM) |

| Stopped flow: fast phase | 5.6 ± 0.2 |

| Stopped flow: lag phase | 7.8 ± 1.0 |

| Direct titration | 4.6 ± 1.2 |

NMR data identify aromatic amino acids as the predominant sites of binding for β-CD

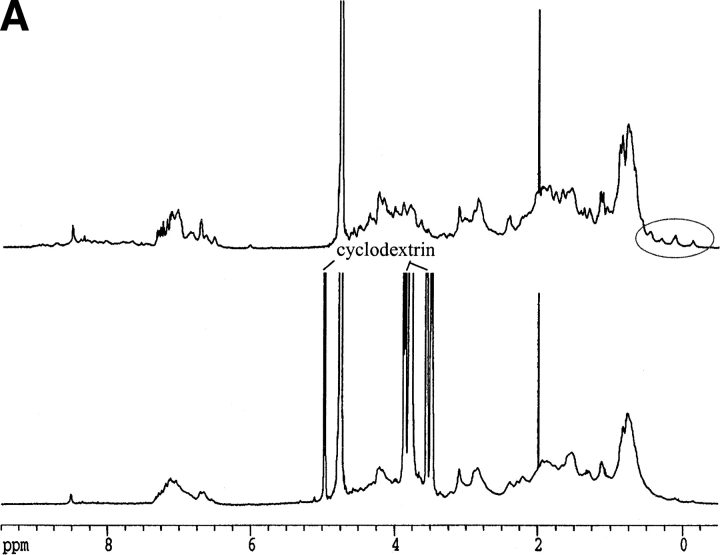

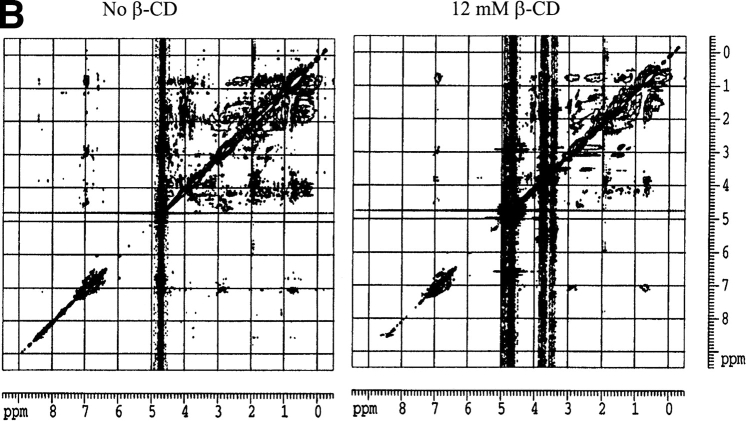

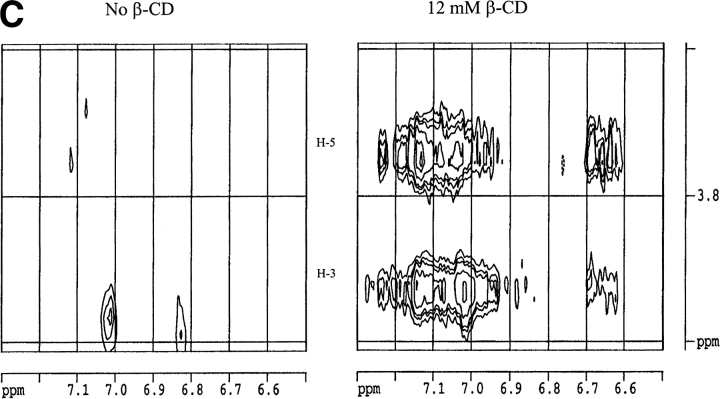

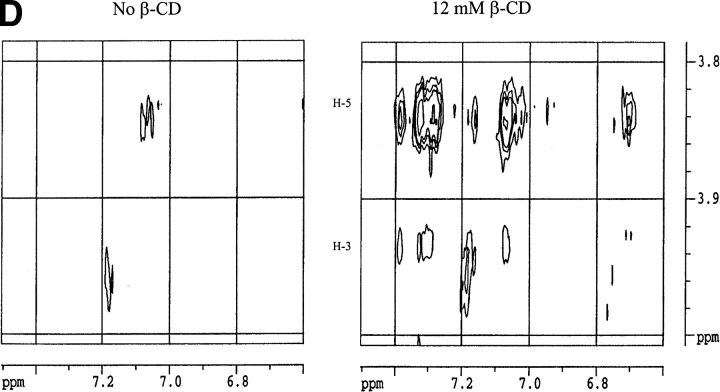

Circular dichroism is not sensitive enough to monitor the interaction between hGH and CDs. The near-UV spectrum, which monitors the structure experienced by the aromatic amino acids, does not show any significant changes on addition of CDs to hGH at pH 2.5 or pH 7.0 (data not shown). NMR is more informative. The one-dimensional NMR spectrum of hGH at pD 1.7 changes on addition of β-CD (Fig. 5A ▶). Note in particular the perturbed chemical shift of methyl peaks at ∼0 ppm, which disappear in the presence of β-CD. These peaks are normally taken as evidence of folded structure, and their disappearance indicates that β-CD leads to a more complete unfolding of hGH. Further evidence for increased unfolding comes from two-dimensional NOESY (nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy) spectra, which show that the cross-peaks evident in the absence of β-CD at pD 1.7 (Fig. 5B ▶, left panel) collapse into discrete areas on addition of the CD (Fig. 5B ▶, right panel). The interactions between hGH and β-CD are shown in more detail in Fig. 5C ▶ (right panel); the reference spectrum in the absence of β-CD (Fig. 5C ▶, left panel) proves that essentially all the peaks in this region of the spectrum arise from hGH-CD interactions. The interactions only involve H-3 and H-5 on β-CD (i.e., the interior of the hydrophobic cavity) and Phe and Tyr residues on hGH. The chemical shifts in the 6.7 to 6.6 ppm interval can be assigned to Tyr Hɛ, whereas the 7.3 to 6.9 ppm range corresponds to Hδ, Hɛ and Hψ of Phe and Hδ of Tyr (Bundi and Wüthrich 1979). However, none of these peaks can be assigned to specific amino acid residues because of the lack of NMR assignment data for hGH.

Fig. 5.

(A) One-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of hGH at pD 1.7 alone (top spectrum) and with 12 mM β-CD (lower spectrum). Note the disppearance of the methyl peaks around 0 ppm. (B) Two-dimensional NOESY spectrum of hGH at pD 1.7 alone (left) and with 12 mM β-CD (right), highlighting the cross-peaks between β-CD and hGH. (C) Close-up of the region of interaction between hGH and β-CD from B (right) and the region in the absence of β-CD (left). (D) As C but at pD 6.8.

At pD 6.8, the one-dimensional NMR spectrum of hGH is not affected by β-CD. However, some cross-peaks between β-CD and hGH are seen in the two-dimensional NOESY spectra, although it is evident that a smaller number of side-chains are involved in the interactions (Fig. 5D ▶) compared with pD 1.7.

Discussion

CDs as aggregation suppressors

In this study, we introduce a new and convenient aggregation model system, namely, salt-induced aggregation of hGH at low pH. Salts have been used to precipitate proteins since the early days of protein research. In general, NaCl stimulates protein-protein association by two different means, namely, (1) screening of repulsive charges prevalent at extreme pH and (2) the phenomenon of preferential hydration, in which NaCl is excluded from the protein surface and therefore encourages the reduction of solvent-exposed surface area (Timasheff 1993). Screening is already very pronounced at 150 mM NaCl, whereas preferential hydration is a weaker effect that generally manifests itself at higher concentrations. Because aggregation of hGH only becomes significant at ∼0.7 M NaCl, preferential hydration is likely to be the dominant driving force for aggregation in our model system. Although aggregation here occurs by salt-induced precipitation, we consider this process to mimic aggregation under other conditions such as thermal denaturation, vortexing, or rapid dilution from high denaturant concentrations. Partially folded states such as the acid state are particularly susceptible to aggregation (see below); by comparison, the native state of most proteins (including hGH) does not precipitate out below 4 M NaCl.

The various CDs show very different solubilizing abilities. α- and γ-CD are much less efficient than the best β-CD derivatives, probably owing to the different cavity dimensions. The diameter of a benzene ring ranges from 5.2 to 6.0 Å. This allows for a snug fit into the β-CD cavity (Hamilton et al. 1976; Inoue and Miyata 1981), which has a diameter of ∼6.4 Å at H-3 and ∼6.0 Å at H-5 (Easton and Lincoln 1999). In contrast, α-CD (∼5.2 Å at H-3 and ∼4.7 Å at H-5) and γ-CD (∼8.3 Å at H-3 and ∼7.8 Å at H-5) are too small and too large, respectively. Substituents on the β-CD ring also affect aggregation suppression; for example, the anionic sulfated β-CD and the neutral acetyl-β-CD have no effect, and the sulfobutyl-ether derivative Captisol only performs about half as well as HP-βCD and the branched β-CDs (Table 1). These substituents both affect solubility and the accessibility of the cavity. The branched CDs, glycosyl- and maltosyl-β-CD, proved overall best in preventing hGH aggregation. The chemically derivatized HP-β-CD and Captisol have randomly distributed substituents at both C2 and C3 of the wide rim of the CD as well as C6 at the narrow rim of the CD, reducing the accessibility to both entrances of the β-CD cavity. In contrast, glycosyl- and maltosyl-β-CD are homogeneous products, only substituted at C6 at the narrow rim of β-CD. This allows full access to the CD cavity through the wide rim of the CD. Their lower [CD]50% values indicate that the wide rim of β-CD is the binding site for aromatic amino acids. This is supported by NMR studies on complexes between amino acids and β-CD (R.W. and K.L.L., unpubl.).

A recent study on the aggregation of carbonic anhydrase reported a lack of effect by carboxymethylated CDs (Sharma and Sharma 2001), whereas quaternary ammonium-CDs and acetyl-CDs were good protein solubilizers. The ambiguous role of acetyl-CDs (which does not prevent aggregation of growth hormone) indicates that the solubilizing ability of the CDs to some extent depends on the individual proteins.

Structural information on the interaction between hGH and HP-βCD

Our NMR data indicate that β-CD stabilizes a more unfolded conformation of hGH at low pH. This is not surprising, given that the unfolded state offers better access to β-CD than the acid-denatured state. Preferential binding of CDs to the denatured state also destabilizes the native state of several proteins (Cooper 1992). The NMR data do not permit us to determine the dissociation constants of the hGH-β-CD complex at pD 1.7 and 6.8, but they do indicate that more residues are involved at low pH. Because no proton assignment of hGH has been published, it is impossible to get a whole or even a partial assignment of the interaction sites. Nevertheless, the cross-peaks in the recorded two-dimensional NOESY spectra indicate that interactions between hGH and β-CD occur in at least two different sites in the native state. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) studies have also shown that hGH has at least two binding sites for maltosyl-β-CD (Irie and Uekama 1999). The structure of the native state of hGH shows that most of the 21 aromatic amino acids are partially or completely buried. This leaves six highly exposed residues (Phe 25, Tyr 42, Phe 44, Phe 92, Tyr 103, and Phe 139) as the most likely interaction partners with β-CD in the native state. An even larger number of residues will be solvent accessible in the acid-denatured state. For steric reasons, only a fraction of the possible interaction sites may be populated a any given time. β-CD only needs to bind to a fraction of these exposed residues to avoid aggregation.

A 1H-NMR-based investigation of the interactions between monomeric insulin and various CDs also indicates preferential binding to aromatic amino acids, but no direct unfolding activity by the CDs was reported (Tokihiro et al. 1997).

Protein aggregation and approaches to prevent it

There are many reports of the ability of CDs to suppress aggregation of proteins under destabilizing or disruptive conditions, such as thermal denaturation, vortexing, or other mechanical exposure; prolonged incubation at room temperature; and rapid refolding from the denatured state (Hagenlocher and Pearlman 1989; Brewster et al. 1991; Banga and Mitra 1993; Charman et al. 1993; Branchu et al. 1999; Sharma and Sharma 2001). The ability to suppress aggregation is particularly useful in the production of proteins that have to be purified from inclusion bodies. These proteins are solubilized in the unfolded state, typically high concentrations of guanidinium chloride or urea, from which they have to be refolded. However, when the proteins are diluted to low denaturant concentrations, folding to the native state often competes with aggregation (Cleland et al. 1993). Including CDs in the dilution buffer improves the yield of native protein (Karuppiah and Sharma 1995), although other agents such as polyethylene glycol (Cleland et al. 1992) or detergents (Tandon and Horowitz 1988) also have a beneficial effect. All these substances seem to work via transient interactions with unfolded/partially unfolded protein, which block exposed hydrophobic surfaces sufficiently to avoid aggregation but not to prevent folding. More recently, a two-step "artifical chaperone kit" has been introduced, in which a cationic detergent in the first step captures the nonnative protein in a complex that stalls both aggregation and renaturation. In the second step, the detergent is slowly removed from the protein by the addition of a cyclodextrin, allowing the majority of the protein population to fold (Rozema and Gellman 1996). This approach, in which the CD may also transiently bind to the unfolded protein, is reported to be more robust than the other methods. However, few attempts have been made to compare all approaches systematically, so it is difficult to assess which is superior in general.

In many cases, aggregation appears to initialize through the specific association of partially folded intermediates. This may occur via a domain-swapping mechanism, in which matching structural elements from each molecule make interactions similar to those found in the native state (Hurle et al. 1994; Fink 1998). The aggregates increase in size as the process is propagated in three dimensions. The specificity of the aggregation is illustrated by bovine growth hormone, which aggregates via an amphipathic helix exposed in a folding intermediate (Brems 1988). When this helix is supplied as a fragment in trans or is replaced by the corresponding helix from hGH, aggregation is inhibited (Lehrman et al. 1991). The strategies developed to counter aggregation seek to increase the partitioning of partially folded intermediates toward the native conformation rather than toward aggregated species. These include osmolytes to stabilize the native state at the expense of the intermediate (Schein 1990), chaperones (Thomas et al. 1997), immobilization, stabilizing agents such as arginine (Rudolph and Lilie 1996), growth at lower temperatures, and fusion proteins (Georgiou and Valax 1996).

Implications for the role of aromatic amino acids in folding and aggregation

Our results showed that α- and γ-CD also interact with hGH, but to a smaller extent than does β-CD, because higher α- and γ-CD concentrations were needed to prevent aggregation. The range of possible amino acid side-chain interactions with different CDs, as well as the effect of neighboring amino acid residues, is far from fully understood. The hydrophobic interior of the cyclodextrin cavity enables CDs to sequester hydrophobic moieties, and this does not necessarily limit them to aromatic amino acids. Although aromatic amino acids are expected to form weaker interactions with α- and γ-CD than with β-CD, α-CD may complex aliphatic amino acids and protonated aspartic and glutamic acids. Linear aliphatic chains from, for example, Ile allow a snug fit in the narrow α-CD cavity, although the binding affinities of aliphatic amino acids toward β-CD are several-fold lower than the aromatics (R.W. and K.L.L., unpubl.). Because of the massive overlap of aliphatic signals from hGH in the two-dimensional NOESY spectra, we cannot speculate on the involvement of these residues in CD interactions. However, their lower affinity relegates their involvement to a lower level than that of the aromatics.

CDs sequester exposed aromatic residues and induce a more unfolded state of hGH, preventing aggregation. This indicates that aromatic residues are involved in the formation of regions of residual structure, and these regions constitute nuclei for aggregation. Nucleation mechanisms are hallmarks for aggregation and manifest themselves as lag phases, just as we have observed in this study. Preexisting nuclei supplied by seeding greatly accelerate, for example, amyloid formation (Harper and Lansbury 1997). Therefore, aggregation is best eliminated by reducing nucleus formation to a minimum.

It is well documented that aromatic amino acids contribute to regions of residual structure in otherwise unfolded proteins, no doubt because of the large amount of hydrophobic surface area they can bury by local interactions. For instance, a β-hairpin region of barnase containing fragments 69–110 shows nonrandom chemical shifts, and implicates a number of aromatic residues (Trp94, Trp71, Tyr79, Phe82, Tyr90, Tyr97, His102, Tyr103, and Phe106), some of which are involved in the folding nucleus, in nonnative hydrophobic contacts (Neira and Fersht 1996). Aromatics are also involved in regions of residual structure in BPTI, the structure of which persists even in 8 M urea and accelerates folding (Dadlez 1997). Similar observations have been reported for the 434-repressor (Neri et al. 1992) and apolipoprotein C-1 (Gursky 2001). The acid-denatured state of the 64-residue protein CI2 is largely devoid of structure and is equivalent to the guanidinium chloride–denatured state in terms of folding properties (Itzhaki et al. 1995). However, the acid-denatured state only shows interactions between the single Trp residue and β-CD; the two aromatics Tyr 42 and Phe 50 do not interact with β-CD, indicating that they are part of one or several regions of persistent structure (F.L.A., K.L.L., R.W., and D.O., unpubl.).

The interactions between CDs and aromatic amino acids may present a very suitable system to suppress nucleation and general intermolecular associations while allowing folding to occur. This is precisely because they are weak and dynamic enough to allow the proteins to sample different intramolecular conformations while obstructing interfaces with other molecules. This indicates that β-CDs should be used on a more systematic level as possible antiaggregators. Native β-CD is not appropriate for this from a toxicological point of view, because it is capable of extracting biomembrane components (Easton and Lincoln 1999), and forms a highly insoluble complex with cholesterol, which may lead to toxic effects after prolonged exposure (Szejtli and Osa 1996). However, careful derivatization of β-CD alters its selectivity toward biomembrane components and minimizes its toxicity (Szejtli and Osa 1996). Currently, drug formulations containing HP-βCD have been approved for parenteral drug administration (e.g., Sporanox containing the antifungal agent intraconazole from Janssen Pharmaceuticals). Captisol (sulphobutyl-ether-β-CD)-based formulations are likely to follow in the near future, for example, Pfizer's Vfend and Geodon, containing the intravenously delivered antifungal voriconazole and the rapid-acting intramuscular antipsychotic ziprasidone, respectively.

Materials and methods

hGH was kindly provided by Novo Nordisk A/S and dissolved in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0) and 40 mM NaCl. α-, β-monoacetyl-, and γ-CDs were from Wacker Chemie GMBH; hydroxypropyl-β-CD (HP-βCD) from Acros Organics; mono-glycosyl-β-CD and mono-maltosyl-β-CD from Ensuiko Sugar Refining Co. Ltd.; and sulfated β-CD, Na-salt from Aldrich Chemical Company, Inc. Captisol (sulfobutyl-ether-β-CD Na-salt, D.S. 6.4) was a kind gift from Dr. V. Stella, University of Kansas, Kansas. 1,8-ANS was from Sigma-Aldrich Corp.

Steady-state aggregation experiments

22 μM hGH in 25 mM glycine buffer (pH 2.5) was incubated with 1 M NaCl at 25°C with 0 to 140 mM CD for at least 1 h. After centrifugation for 15 min at 14,000 rpm, A280 of the supernatant was measured.

Binding of HP-βCD to hGH

22 μM hGH in 25 mM glycine buffer (pH 2.5) was mixed with 0 to 60 mM HP-βCD. The emission at 330 nm on excitation at 295 nm was measured on a RTC 2000 Spectrometer (Photon Technology International).

Binding of 1,8-ANS to hGH

11 μM hGH was mixed with 50 μM 1,8-ANS in 25 mM buffer over the pH range 1.9 to 11.4.

Stopped-flow kinetics

All kinetic stopped-flow experiments were performed at 25°C on an SX18-MV stopped-flow apparatus (Applied Photophysics Ltd.) Initially, 242 μM hGH in 25 mM glycine buffer (pH 2.5) was mixed with 0.99 to 1.21 M NaCl in the same buffer in a 1:10 ratio to give 22 μM hGH and 0.9 to 1.1 M NaCl. In a second series of experiments, the NaCl concentration was held constant to give 1 M after mixing, and the HP-βCD concentration was varied to give 0 to 25 mM after mixing. Excitation wavelength was 295 nm, and emission was detected above 320 nm with a glass cut-off filter. A minimum of 5 accumulations was averaged.

NMR spectroscopy

hGH was freeze-dried and resuspended in 99.9% deuterium oxide (D2O) two times to reduce the water signal in the spectra. hGH was then dissolved to 0.7 mM in 99.99% D2O with 110 mM phosphate pD 1.7 or pD 6.8 (corresponding to pH 2.1 and 7.2, respectively). β-CD was added to a final concentration of 12 mM after the recording was completed on the sample without β-CD. Spectra were recorded on a BRUKER DRX600 spectrometer equipped with a 5-mm xyz-grad TXI(H/C/N) probe. 1H two-dimensional NOESY spectra with 100 ms mixing time were conducted to detect intermolecular interactions between β-CD and hGH. The NMR data were processed with BRUKER XwinNMR version 2.5 software and spectral analysis was performed with XEASY version 1.3.13 (Bartels et al. 1995).

Data analysis

Solubilization of hGH by CD derivatives

[CD]50%, the CD concentration at which half the hGH was solubilized, was estimated visually after fitting a smoothing function to a plot of the A280 of the supernatant versus [CD].

Stopped-flow kinetics

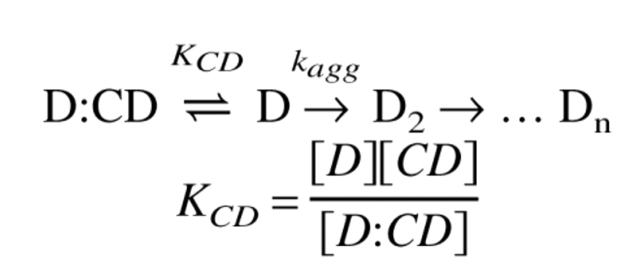

During aggregation of acid-denatured hGH (D), three phases are observed, namely, a lag phase, a fast phase, and a slow phase. We assume the following simple mechanism for the aggregation of acid-denatured hGH, in which aggregation only occurs through the dimerized intermediate, as indicated by equilibrium studies (DeFelippis et al. 1995; Kasimova et al. 1998).

|

The observed aggregation rate kobs can then be espressed as:

|

(1) |

Here fD denotes the amount of uncomplexed protein. At each CD concentration, we use (1) the fast aggregation rate (from the fit of the post-lag phase kinetic data to a double exponential phase) and (2) the reciprocal of the visually estimated lag time as values for kagg. KCD is obtained from plots of kagg versus [CD].

We have no direct data on the stoichiometry of the hGH/CD complex and therefore assume a 1:1 relationship for simplicity. This gives a very reasonable fit to both the kinetic (Fig. 4A ▶) and equilibrium (Fig. 4B ▶) data. The quality of the fits makes it unnecessary to assume higher-order relationships in the model.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hans Holmegaard Sørensen and Novo Nordisk A/S for generously providing hGH for this project. B.R.K. and F.L.A. were in part supported by Novo Scholarship Stipends. D.E.O. is supported by the Danish Technical Science Research Council.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.0202702.

References

- Abildgaard, F., Jorgensen, A.M.M., Led, J.J., Christensen, T., Jensen, E.B., Junker, F., and Dalboge, H. 1992. Characterization of tertiary interactions in a folded protein by NMR methods: Studies of pH-induced structural changes in human growth hormone. Biochemistry 31 8587–8596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banga, A.K. and Mitra, R. 1993. Minimization of shaking-induced formation of insoluble aggregates of insulin by cyclodextrins. J. Drug. Target. 1 341–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, C., Xia, T.-H., Billeter, M., Günter, P., and Wüthrich, K. 1995. The program XEASY for computer-supported NMR spectral of biological macromolecules. J. Biomol. NMR 5 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branchu, S., Forbes, R.T., York, P., Petrén, S., Nyqvist, H., and Camber, O. 1999. Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin inhibits spray-drying–induced inactivation of β-galactosidase. J. Pharm. Sci. 88 905–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brems, D.N. 1988. Solubility of different conformers of bovine growth hormone. Biochemistry 27 4541–4546. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, M.E., Hora, M.S., Simpkins, J.W., and Bodor, N. 1991. Use of 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin as a solubilizing and stabilizing excipient for protein drugs. Pharm. Res. 8 792–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundi, A. and Wüthrich, K. 1979. 1H-NMR parameters of the common amino acid residues measured in aqueous solutions of the linear tetrapeptides H-Gly-Gly-X-L-Ala-OH. Biopolymers 18 285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Chantalat, C., Jones, N.D., Korber, F., Navaza, J., and Pavlovsky, A.G. 1995. The crystal structure of wild-type growth hormone at 2.5-Å resolution. Protein Pept. Lett. 2 333–340. [Google Scholar]

- Charman, S.A., Mason, K.L., and Charman, W.N. 1993. Techniques for assessing the effects of pharmaceutical excipients on the aggregation of porcine growth hormone. Pharm. Res. 10 954–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland, J.L., Builder, S.E., Swartz, J.R., Winkler, M., Chang, J.Y., and Wang, D.I. 1992. Polyethylene glycol enhanced protein refolding. Biotechnology 10 1013–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland, J.L., Powell, M.F., and Shire, S.J. 1993. The development of stable protein formulations: A close look at protein aggregation, deamidation and oxidation. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 10 307–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors, K.A. 1997. The stability of cyclodextrin complexes in solution. Chem. Rev. 97 1325–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, A. 1992. Effect of cyclodextrins on the thermal stability of globular proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114 9208–9209. [Google Scholar]

- Dadlez, M. 1997. Hydrophobic interactions accelerate early stages of the folding of BPTI. Biochemistry 36 2788–2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelippis, M.R., Kilcomons, M.A., Lents, M.P., Youngman, K.M., and Havel, H.A. 1995. Acid stabilization of human growth hormone equilibrium folding intermediates. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1247 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton, C.J. and Lincoln, S.F. 1999. Modified cyclodextrins: Scaffolds and templates for supramolecular chemistry, Imperial College Press, London.

- Engelhard, M. and Evans, P.A. 1995. Kinetics of interaction of partially folded proteins with a hydrophobic dye: Evidence that molten globule character is maximal in early folding intermediates. Protein Sci. 4 1553–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink, A.L. 1998. Protein aggregation: Folding aggregates, inclusion bodies and amyloid. Folding Design 3 R9–R29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frömming, K.-H. and Szejtli, J. 1994. Cyclodextrins in pharmacy, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht.

- Georgiou, G. and Valax, P. 1996. Expression of correctly folded proteins in Escherichia coli. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 7 190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gursky, O. 2001. Solution conformation of human apolipoprotein C-1 inferred from proline mutagenesis: Far- and near-UV CD study. Biochemistry 40 12178–12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenlocher, M. and Pearlman, R. 1989. Use of a substituted cyclodextrin for stabilization of solutions of recombinant human growth hormone. Pharm. Res. 6 S30. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J.A., Sabesan, M.N., Steinrauf, L.K., and Geddes, A. 1976. The crystal structure of a complex of cycloheptaamylose with 2,5-diiodobenzoic acid. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 73 659–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper, J.D. and Lansbury, P.T.J. 1997. Models of amyloid seeding in Alzheimer's disease and scrapie: Mechanistic truths and physiological consequences of the time-dependent solubility of amyloid proteins. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 66 385–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsky, J. and Pitha, J. 1994. Inclusion complexes of proteins: Interaction of cyclodextrins with peptides containing aromatic amino acids studied by competitive spectrophotometry. J. Inclusion Phenom. Mol. Recog. Chem. 18 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Hurle, M.R., Helms, L.R., Li, L., Chan, W., and Wetzel, R. 1994. A role for destabilizing amino acid replacements in light-chain amyloidosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 91 5446–5450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, Y. and Miyata, Y. 1981. Formation and molecular dynamics of cycloamylose inclusion complexes with phenylalanine. Bull. Chem. Soc. Japan 54 809–816. [Google Scholar]

- Irie, T. and Uekama, K. 1999. Cyclodextrins in peptide and protein delivery. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 36 101–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki, L.S., Otzen, D.E., and Fersht, A.R. 1995. The structure of the transition state for folding of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2 analysed by protein engineering: Evidence for a nucleation-condensation mechanism for protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 254 260–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jicsinszky, L., Fenyvesi, E., Hashimoto, H., and Ueno, A. 1996. Cyclodextrin derivatives. In Comprehensive supramolecular chemistry: Cyclodextrins, vol. 3 (eds. J. Szejtli, J. and T. Osa, T.), pp. 98–137. Elsevier Science Ltd., Oxford.

- Karuppiah, N. and Sharma, A. 1995. Cyclodextrins as protein folding aids. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 211 60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasimova, M.R., Milstein, S.J., and Freire, E. 1998. The conformational equilibrium of human growth hormone. J. Mol. Biol. 277 409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, K.L. 2001. Large cyclodextrins. Biol. J. Armenia 53 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lehrman, S.R., Tuls, J.L., A., H.H., Haskell, R.J., Putnam, S.D., and Tomich, C.C. 1991. Site-directed mutagenesis to probe protein folding: Evidence that the formation and aggregation of a bovine growth hormone folding intermediate are dissociable processes. Biochemistry 30 5777–5784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida, S., Ogawa, S., Xiaohua, S., Takaha, T., Fujii, K., and Hayashi, K. 2000. Cycloamylose as an efficient artificial chaperone for protein refolding. FEBS Lett. 486 131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neira, J.L., and Fersht, A.R. 1996. An NMR study on the β-hairpin region of barnase. Folding Design 1 231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neri, D., Billeter, M., Wider, G., and Wüthrich, K. 1992. NMR determination of residual structure in a urea-denatured protein, the 434-repressor. Science 257 1559–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozema, D. and Gellman, S.H. 1996. Artificial chaperone-assisted refolding of denatured-reduced lysozyme: Modulation of the competition between renaturation and aggregation. Biochemistry 35 15760–15771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, R. and Lilie, H. 1996. In vitro folding of inclusion body proteins. FASEB J. 10 49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schein, C.H. 1990. Solubility as a function of protein structure and solvent components. Biotechnology 7 690–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurjonsdottir, J.F., Loftsson, T., and Masson, M. 1999. Influence of cyclodextrins on the stability of the peptide salmon calcitonin in aqueous solution. Int. J. Pharm. 186 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szejtli, J. 1988. Cyclodextrin technology, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht.

- ———. 1998. Introduction and general overview of cyclodextrin chemistry. Chem. Rev. 98 1743–1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szejtli, J., and Osa, T., eds. 1996. Comprehensive supramolecular chemistry: Cyclodextrins, vol. 3. Elsevier Science Ltd, Oxford, England.

- Tandon, S. and Horowitz, P. 1988. The effects of lauryl maltoside on the reactivation of several enzymes after treatment with guanidinium chloride. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 955 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.G., Ayling, A., and Baneux, F. 1997. Molecular chaperones, folding catalysts, and the recovery of active recombinant proteins from E. coli: To fold or to refold. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 66 197–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timasheff, S.N. 1993. The control of protein stability and association by weak interactions with water: How do solvents affect these processes? Ann. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 22 67–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokihiro, K., Irie, T., and Uekama, K. 1997. Varying effects of cyclodextrin derivatives on aggregation and thermal behavior of insulin in aqueous solution. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 45 525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]