Abstract

The aggregation observed in protein conformational diseases is the outcome of significant new β-sheet structure not present in the native state. Peptide model systems have been useful in studies of fibril aggregate formation. Experimentally, it was found that a short peptide AGAAAAGA is one of the most highly amyloidogenic peptides. This peptide corresponds to the Syrian hamster prion protein (ShPrP) residues 113–120. The peptide was observed to be conserved in all species for which the PrP sequence has been determined. We have simulated the stabilities of oligomeric AGAAAAGA and AAAAAAAA (A8) by molecular dynamic simulations. Oligomers of both AGAAAAGA and AAAAAAAA were found to be stable when the size is 6 to 8 (hexamer to octamer). Subsequent simulation of an additional α-helical AAAAAAAA placed on the A8-octamer surface has revealed molecular events related to conformational change and oligomer growth. Our study addresses both the minimal oligomeric size of an aggregate seed and the mechanism of seed growth. Our simulations of the prion-derived 8-residue amyloidogenic peptide and its variant have indicated that an octamer is stable enough to be a seed and that the driving force for stabilization is the hydrophobic effect.

Keywords: Amyloid, prion, β-sheet, molecular dynamics simulation, protein folding, protein unfolding, conformational conversion

Changes in sequence or shape of a protein may lead to a conformational disease. Conformational diseases are typically expressed in the appearance of amyloid fibrils. Understanding amyloid seed formation and elongation at the molecular level presents a major challenge, as it may lead to novel approaches in design and therapy (Carrell and Lomas 1997). A relatively large number of protein conformational diseases have already been identified (Chesebro 1998). Interestingly, at least in proteins related to Alzheimer, prion protein-related encephalopathies, and type II diabetes, it has been discovered that certain short sequence fragments (5–40 residues) contained within the respective proteins can form amyloids even in isolated peptide form. The β-peptide (Aβ, 42 residues) from Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein constitutes one such example. A key step in Alzheimer involves proteolytic cleavage of Aβ (Haass and Strooper 1999). The fragment consisting of residues 25–35 in Aβ (GSNKGAIIGLM) has been shown to already form large β-sheet fibrils that are essentially similar to those obtained by the full-length Aβ (Shearman et al. 1994; Terzi et al. 1994; Iverson et al. 1995; Pike et al. 1995; Hughes et al. 2000). The human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP), a 37-residue peptide hormone involved in type II diabetes, constitutes another such example. Fibrils obtained from this hormone have been observed to be toxic to human and to rat islet β-cells in vitro (Lorenzo et al. 1994). Experiments have shown that a hexamer of hIAPP (residues 22–27, NFGAIL), and even a pentamer (residues 23–27, FGAIL), are already sufficient for amyloid formation and cytotoxicity (Tenidis et al. 1999). Prion proteins also contain such amyloidogenic peptide-fragments. Prions are infectious protein agents lacking nucleic acids. They consist of altered β-sheet-rich conformations of a normal cellular protein (Prusiner 1991, 1998). Recently, for the first time, the prion hypothesis has been proved (Sparrer et al. 2000). In particular, several fragments of Syrian hamster prion protein (ShPrP) have been observed to form amyloids. These include residues 109–122, 178–191, and 202–218 (Gasset et al. 1992). Within these, the most highly amyloidogenic peptide is AGAAAAGA, which corresponds to ShPrP residues 113–120. This fragment is conserved in all species whose PrP sequence has been determined (Gasset et al. 1992). Sup35 is a prion-like protein in yeast. It has a polar fragment (GNNQQNY) that shows the amyloid properties of full-length Sup35 (Balbirnie et al. 2001).

The fact that these disease-related short peptides are amyloidogenic and toxic makes them particularly useful for studies of amyloid formation and elongation. The fibrils formed by short peptide fragments may or may not have the same fibril form and the same toxicity. For the islet amyloid polypeptide, the fibrils formed by all short peptide fragments were cytotoxic toward the pancreatic cell line (Tenidis et al. 1999). In the case of amyloid formation by the β-peptide, the truncated peptide Aβ(25–35) leads to a faster onset of the toxic effect and to a larger oxidative damage than the parent Aβ(1–42). Our work has shown that the truncated peptide fragments (16–22 and 25–35) have different fibril formations from those of the longer sequences of 10–35, which is closer to Aβ(1–42) (Ma and Nussinov 2002). Nevertheless, the kinetics of amyloid formation from such short peptides is similar to that of their larger parent proteins. Consequently, in principle, studies of such short amyloidogenic peptides may illuminate some of the fundamental processes taking place in amyloid formation in large protein systems. Whereas in principle short peptide systems are considerably simpler than those of large proteins, obtaining atomic detail on peptide amyloid formation from X-ray diffraction of amyloid fibrils has proved to be equally difficult. Amyloid fibrils from both short peptides and large proteins yield only limited information on the pattern of the β-sheet backbone within the fibril. Furthermore, current experimental methodologies encounter difficulties in obtaining atomic details regarding seed formation and propagation. To get an insight into the fundamentals of amyloid formation, here we present a theoretical approach using extensive molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the oligomerization of two peptides, AGAAAAGA and AAAAAAAA.

Our study focuses on two aspects: the stability of the oligomeric β-sheets, which would indicate minimal seed size and the mechanism(s) through which the β-sheet propagates. Amyloid formation is a considerably slower process than protein/peptide folding. Therefore, it is unrealistic to expect to observe amyloid formation directly from simulations of random peptide conformations. Instead, we start from preformed oligomeric β-sheets of various sizes (trimeric, tetrameric, hexameric, and octameric oligomers) and simulate the stabilities of the peptide oligomers in water. After identifying stable oligomers, we simulate how the stable oligomer will affect the conformational changes of other peptides.

Currently, there is no evidence that AGAAAAGA or AAAAAAAA fragments are involved in the initialization of the prion amyloid formation. Nevertheless, our study provides an insight into the preference of the β-strand arrangements of these fragments in amyloids. More important, our current studies provide some elementary information regarding what can be learned about the complex amyloid formation problem from molecular simulations. The assumption implicit in such a simulation approach is that peptides may form amyloids if their oligomers are stable, surviving high temperature molecular dynamics simulations; conversely, they are unlikely to form amyloids under these conditions if their oligomers dissociate during the simulations. Recently, we have applied this methodology to the NFGAIL fragment from the hIAPP. Experimentally, NFGAIL forms amyloids, whereas the mutant NAGAIL does not (Azriel and Gazit 2001). Consistently, we found that an NFGAIL nonamer survives the high temperature simulation and that the NAGAIL nonamer with the same structure dissociates rapidly (Zanuy et al., 2002). In the simulations of oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid β-peptide fragments 16–22, 24–36, 16–35, and 10–35, we also obtained a good agreement with solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies, including a novel bent double-layered hairpin-like structure for A-β(10–35) (Balbach et al. 2000; Ma and Nussinov 2002; R. Tycko pers. comm.).

Results

Trimer, tetramers, and hexamer for AGAAAAGA peptide

The simplest model of a β-sheet is the β-hairpin system, with two β-strands interacting in an antiparallel direction and linked by turn residues. Three antiparallel strands in a β-hairpin conformation were also synthesized and characterized by NMR (Kortemme et al. 1998). Without the turn linkage, β-strands in the β-hairpin system separate (Ma and Nussinov 2000). Therefore, it is expected that small oligomers of peptides will not be stable in solution. The question is how small can an oligomer be and still be stable. The next question that arises is in which direction the small oligomers initially get stabilized. It could be a simple extension of the β-sheet within the β-sheet plane (an open β-sheet) or multilayered β-sheets. In general, an extension of a single-layer β-sheet has to be stabilized by chemical bonds, such as a disulfide crosslink (Venkatraman et al. 2002). In our simulations of β-strand oligomers, we favored multilayered sheets.

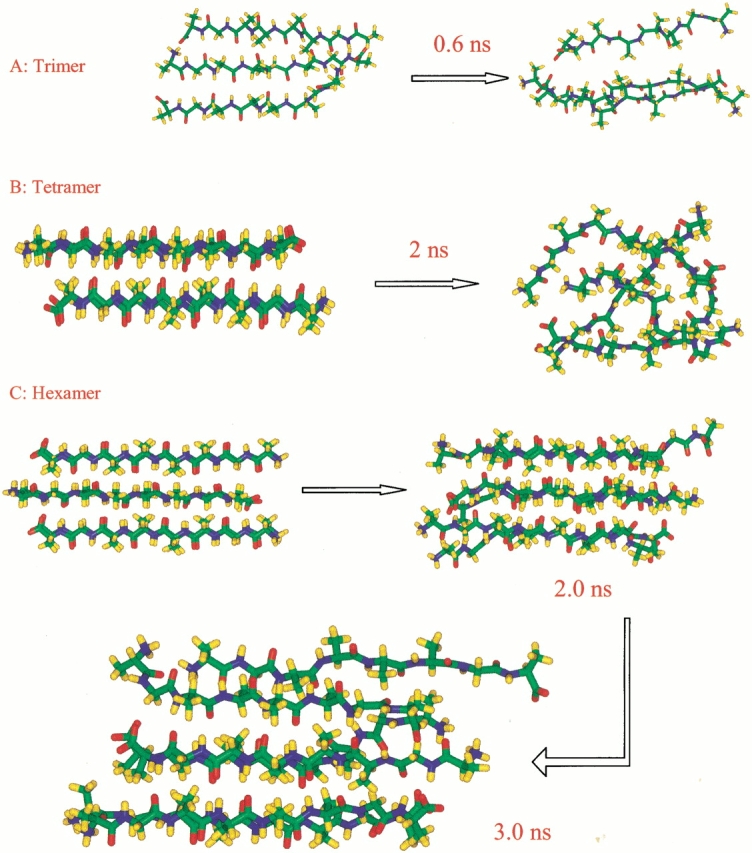

Trimeric NH3+AGAAAAGACOO− was simulated at 300 K, starting with a planar three-stranded antiparallel conformation (Fig. 1a ▶). However, one strand was found to fold over the other two strands rapidly (Fig. 2a ▶), indicating that a planar trimer is not a likely intermediate.

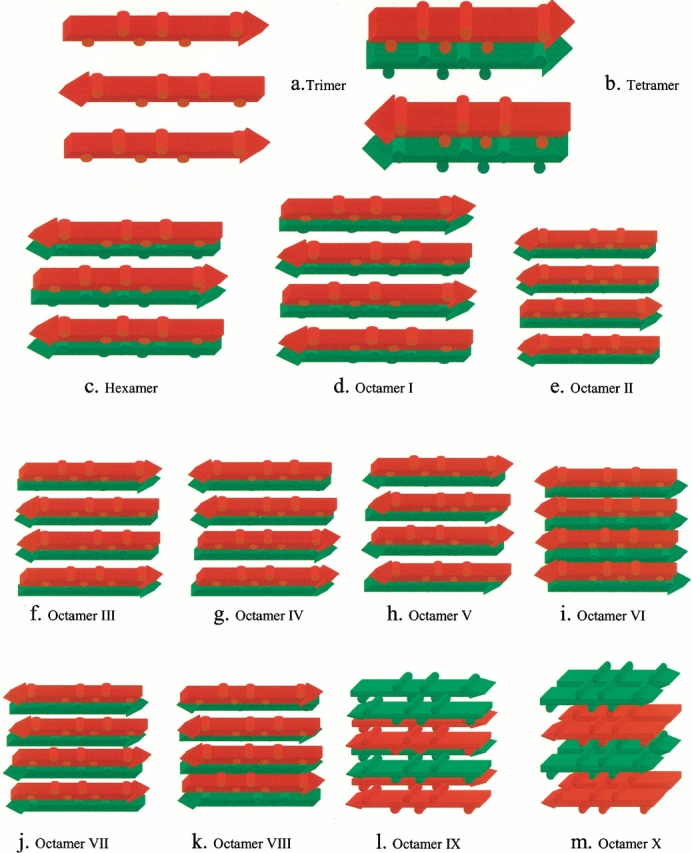

Fig. 1.

Oligomer conformations investigated in this work. Peptides in the same sheet have the same color. The sequence is AGAAAAGA, with the alanine methyl groups depicted as cylindrical humps. (a) Trimer in an antiparallel sheet. (b) Tetramer in two layers. In each layer, the strands are antiparallel. The sheets are parallel. (c) Hexamer in two layers. In each layer the strands are antiparallel sheet. The sheets are parallel. (d) Octamer I. The most stable octamer orientation in which the β strands are antiparallel within each sheet layer but parallel across layers. (e) Octamer II. Three β-strands are antiparallel and one strand is parallel with parallel layers. (f) Octamer III. One parallel interaction (the two strands in the center) and two anti-parallel interactions (at the edges of the complex) with parallel stacking across layers. (g) Octamer IV. Two parallel interactions (along the edges of the complex) and one antiparallel interaction (in the center of the complex) with parallel layers. (h) Octamer V. The β-strands are antiparallel both within each β-sheet layer and across layers. (i) Octamer VI. The β-strands are parallel within each β-sheet layer and with antiparallel layers. (j) Octamer VII. Two parallel interactions (along the edges of the complex) and one antiparallel interaction with antiparallel layers. (k) Octamer VIII. One parallel interaction (two strands in the center) and two antiparallel interactions (at the edges of the complex), with antiparallel stacking across layers. (l) Octamer IX. A sheet of two antiparallel β-strands stacks on other two-stranded sheets in four parallel layers. (m) Octamer X. A sheet of two parallel β-strands stacks on other two-stranded sheets in four antiparallel layers.

Fig. 2.

Snapshots of the conformational changes of trimer (a), tetramer (b), and hexamer (c). The initial conformations are those depicted schematically in Figure 1a–c ▶, respectively.

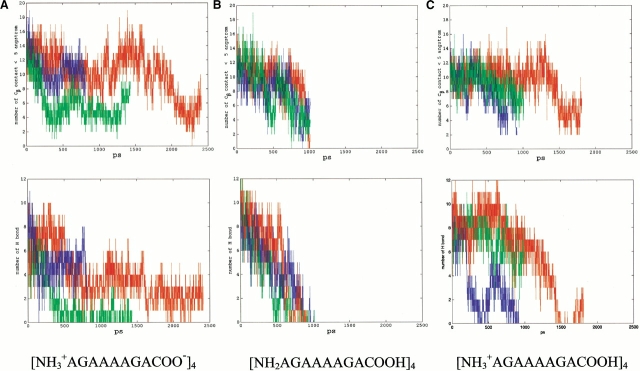

As for a tetramer, we start with a bilayered antiparallel state (Fig. 1b ▶). In such a conformation, two antiparallel sheets stack on top of each other, with the methyl groups in register with each other. We have studied several ionic states for tetramers, including the normal zwitter ion form (NH3+AGAAAAGACOO−)4, the positively charged form (NH3+AGAAAAGACOOH)4, and the neutral species (NH2AGAAAAGACOOH)4. For each ionic state, three separate MD simulations are performed to follow the conformational changes. In general, they change to random coiled states at ∼1 to 2 nanoseconds (ns) at 330 K (Figs. 2, 3 ▶ ▶). To illustrate the stability of the oligomer, we monitor the change in the number of hydrogen bonds and in the methyl group contacts between the β-strands. Nine trajectories for the three tetramers are reported in Figure 2 ▶. The initial starting conformations have ∼15 hydrogen bonds, with the number of hydrogen bonds decreasing rapidly during the simulations. At the end of the simulations, the tetramers still managed to be together like collapsed random coils, mainly because of the hydrophobic interactions among the methyl groups. All tetramers at the three ionic states behave similarly. However, there is a slight preference for the positively charged species, indicating that a low pH value favors a β-cluster formation. The neutral species appears to be the least stable.

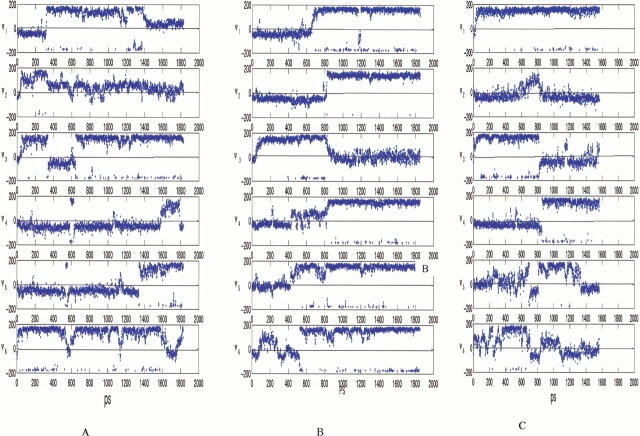

Fig. 3.

Trajectories (methyl group contacts, top row; hydrogen bonds, bottom row) for the tetramer in three ionic states. (a) zwitterion, (b) neutral, and (c) positively charged. Three simulations are performed for each ionic state.

The oligomeric β-sheet complex gains substantial stability when the complex size reaches six ([NH3+ AGAAAAGACOO−]6 hexamer, starting conformation is shown in Fig. 1c ▶). This conformation results from adding two antiparallel strands to each of the β-sheet layers. Therefore, the hexamer consists of two overlapping three-stranded antiparallel β-sheets. The hexamer is stable during most stages of the simulation (3 nanoseconds [ns] at 330 K, Fig 2c ▶, Fig. 4a ▶). At an early stage (<0.5 ns), one pair of peptides at the edge of the complex rapidly unpacks and repacks against the rest of the peptides. At the end of the 3-ns simulation, four β-strands remain a closely packed β-sheet cluster, whereas the two other strands are loosely attached (Fig. 2c ▶).

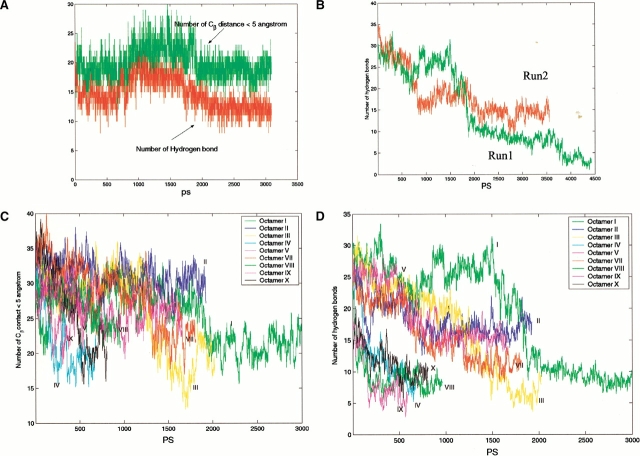

Fig. 4.

Trajectories from simulations of the following: (a) Hexamer, showing the Cβ contacts and the number of hydrogen bonds. (b) Two trajectories of Octamer I in the most stable orientation (Fig. 1d ▶). The figure shows the number of interstrand hydrogen bonds from the two simulations. (c) The methyl group contacts from the simulation of all octamers (Fig. 1e–m ▶), except for Octamer VI. This octamer dissociated after 300 ps and thus is not shown here. (d) The number of interstrand hydrogen bonds from simulations of all octamers, except for Octamer VI. The schematic initial conformations are given in Figure 1e–m ▶.

Is the self-assembly process stabilized by the "hydrophobic effect" or through a competition between inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonds? Experimentally, the formation of the polyalanine β-pleated sheet complex was found to be significantly enhanced on temperature elevation (Blondelle et al. 1996), indicating the role of hydrophobic interactions. Our observation of the increasing stability with complex size similarly derives from hydrophobicity. In a tetramer, every peptide and all methyl groups in the cluster are exposed to the solvent. However, there are buried methyl groups in the hexamer, and the hydrophobic effect plays a central role in stabilizing the hexamer. This conclusion is based on analysis of the changes in the hydrophobic contacts (between the methyl groups) and of interstrand hydrogen bonding in the simulations. As seen in Figures 3 and 5 ▶ ▶, although the number of interstrand hydrogen bonds decrease with simulation time, most methyl groups are still in contact with each other.

Fig. 5.

Snapshots of conformational changes taking place in Octamer I (Fig. 1d ▶) from run 1. The stable β-strand interactions are retained over a long simulation time.

The methyl group is the smallest hydrophobic side chain. Aggregation of methane was used to simulate the hydrophobic effect in aqueous solution (Raschke et al. 2001). These investigators found that the formation of small clusters of methane molecules is thermodynamically unfavorable because the buried surface formed by the small methane cluster is not large enough to compensate for the loss of solvent entropy in forming the contact pair. Our observation of the stability of a hexamer is similar to their finding of the requirement to have minimum buried surface.

AGAAAAGA octamers

To investigate the most likely β-sheet arrangement, we have extensively simulated conformations of AGAAAAGA octamers with various hydrophobic (methyl group) contacts in parallel/antiparallel combinations. We further compared two layered with four layered oligomers.

Figures 1d–m ▶ illustrate the investigated octamer conformations, including (I) the most stable orientation, in which the β-strands are antiparallel within each β-sheet layer but parallel across layers (Fig. 1d ▶, Octamer I); (II) three β-strands are antiparallel and one strand is parallel with parallel layers (Fig. 1e ▶, Octamer II); (III) one parallel interaction (two strands in the center) and two antiparallel interactions (at the edges of the complex) with parallel stacking across layers (Fig. 1f ▶, Octamer III); (IV) two parallel interactions (along the edges of the complex) and one antiparallel interaction (in the center of the complex) with parallel layers (Fig. 1g ▶, Octamer IV); (V) the β-strands are antiparallel both within each β-sheet layer and across layers (Fig. 1h ▶, Octamer V); (VI) the β-strands are parallel within each β-sheet layer and with antiparallel layers (Fig. 1i ▶, Octamer VI); (VII) two parallel interactions (along the edges of the complex) and one antiparallel interaction with antiparallel layers (Fig. 1j ▶, Octamer VII); (VIII) one parallel interaction (two strands in the center) and two antiparallel interactions (at the edges of the complex) with antiparallel stacking across layers (Fig. 1k ▶, Octamer VIII); (IX) a sheet of two antiparallel β-strands stacks on other two-stranded sheets in four layers (Fig. 1l ▶, Octamer IX); and (X) a sheet of two parallel β-strands stacks on other two-stranded sheets in four layers (Fig. 1m ▶, Octamer X).

The trajectories for interstrand methyl group contacts and the number of hydrogen bonds are reported in Figure 4c and d ▶, respectively. Conformers IV, VI, VIII, IX, and X are the least stable, and both methyl group contacts and hydrogen-bonding interactions among the strands disappear rapidly. Other conformers (Octamers I, II, III, V, and VII) are more stable. Although all of the octamers investigated do not survive the 330 K simulations as perfect β-sheet oligomers, their kinetic stabilities still indicate a preferred β-strands orientation and provide rich information regarding peptide interactions in aggregated oligomers.

Two simulations are performed for Octamer I at 330 K, using different initial velocity assignment and slightly different starting conformations; however, the β-strands orientations are the same. The trajectories from both runs behave similarly. Interstrand methyl group contacts are almost identical for the two simulations (data not shown); however, the hydrogen-bonding trajectories vary (Fig. 4b ▶). The characteristics of the dissociation of Octamer I at 330 K are similar to those of the hexamer. Indeed, six strands in Octamer I behave like a hexamer for up to 3 ns of the simulation. Again, the stable tetramer portion of the octamer retains the β-strands interaction for a long time (Fig. 5 ▶).

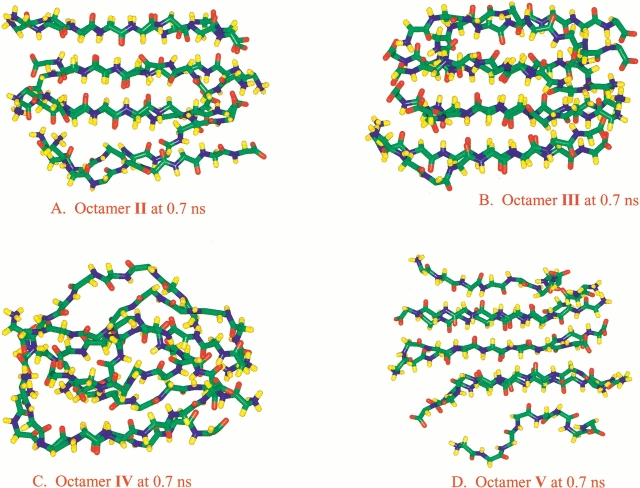

Although we have not exhaustively tested all possible β-strand arrangements in octamers, the trends observed in the 10 conformers have indicated that, for AGAAAAGA, the most favorable oligomeric arrangements are antiparallel β-strands and parallel cross-layer stacking (Fig. 1d ▶, Octamer I). Such a conclusion is not only indicated by the simulation of Octamer I, which shows the most stable hydrogen-bonding interaction and methyl-group contact, but also supported by a comparison of the simulation behavior of other octameric arrangements. Octamer II differs from Octamer I in one parallel interaction. In the simulation, the hydrogen bonds among the parallel β-strands disappear first, with the other portion of Octamer II also behaving like a stable hexamer (Fig. 6a ▶). Octamer III (Fig. 1f ▶) introduces parallel interaction in the center of the β-strands, further destabilizing the oligomer (Fig. 6b ▶). Continuing this trend of parallel interaction being destabilizing, Octamer IV (Fig. 1g ▶) rapidly dissociates in our simulation (Fig. 6c ▶). Octamer V, which has an initial arrangement of antiparallel β-strands and antiparallel layers, quickly rearranges into parallel layers via layer sliding (Fig. 6d ▶).

Fig. 6.

Snapshots from the simulations for several octamers at 0.7 nanoseconds (ns) simulation time. (a) Octamer II. (b) Octamer III. (c) Octamer IV. (d) Octamer V. The initial conformations are schematically drawn in Figure 1 ▶.

Comparing two layered (I–VIII) with four-layered oligomers (IX and X), the two-layered oligomers have better stabilities. This behavior comes from better hydrophobic protection in the two layered octamers than the four layered models. However, if each layer has more than three strands, the additional layer may provide extra stabilization (e.g., in a possible three-strand three-layer nonamer). In the present study, we did not explore this possibility. Such models were tested in a separate study of the NFGAIL nonamers (Zanuy et al. 2002).

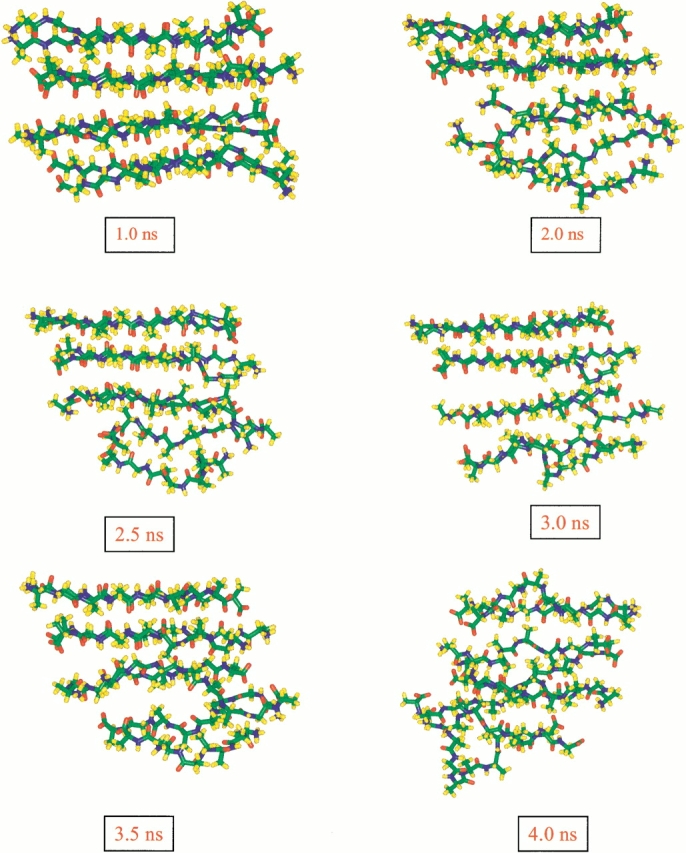

AAAAAAAA tetramer and octamer

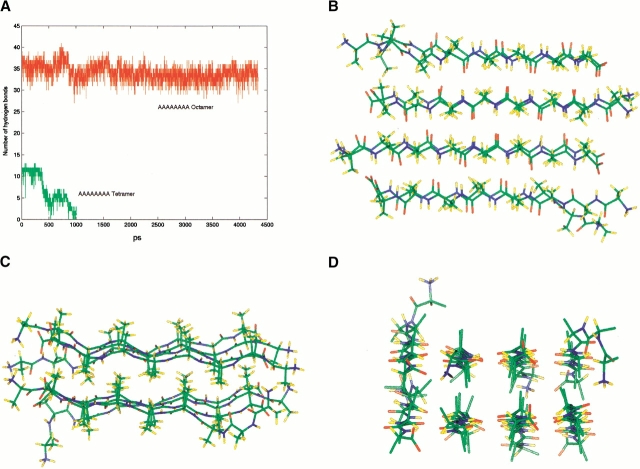

Polyalanine-based peptides have also been used as a model system to study amyloid formation (Blondelle et al. 1996). Aggregates of repeated alanine segments have been found to be associated with cell death (Rankin et al. 2000). Consequently, we also study polyalanine species, including the tetramer (NH3+AAAAAAAACOO−)4 and the octamer (NH3+AAAAAAAACOO−)8. First, we compare A8 oligomers with AGAAAAGA oligomers to examine the effects of glycine mutations. The stability of the AAAAAAAA tetramer was simulated at 330 K. The two tetramers, that of the A8 and of the AGAAAAGA, behave similarly, as illustrated by the trajectories of hydrogen bonds in the tetramers (AGAAAAGA tetramer, Fig. 3 ▶; AAAAAAAA tetramer, Fig. 7a ▶). On the other hand, the polyalanine octamer is considerably more stable than the AGAAAAGA octamer. After a long simulation at 330 K (4.3 ns) and subsequently at 350 K (1.6 ns), the A8 octamer still effectively holds perfect double-layer β-sheets (Fig. 7 ▶). Even at 400 K (1.3 ns), only one strand along the edge of the sheet was found to be partially deformed. Apparently, after the formation of the octamer complex, the additional methyl groups offer better hydrophobic interactions. In the next section of simulations of interactions of the preformed A8 octamer and random AAAAAAAA, the β-sheet oligomers also show great stability.

Fig. 7.

Polyalanine simulations: (a) Trajectories of the (NH3+AAAAAAAACOO−)8 octamer and of the (NH3+AAAAAAAACOO−)4 tetramer. (b–d) Different views of a snapshot from the octamer polyalanine simulations.

The equilibrium structure of the A8 octamer (Fig. 7 ▶) captures an essential feature of an amyloid protofilament. The widely adopted model for amyloid fibrils is the cross-β structure (for review, see Sunde and Blake 1998). In such a model, the fibril axis runs parallel to the direction of the backbone hydrogen bonds, whereas the β-strands are perpendicular to it. A 24 β-stranded unit constitutes a complete helical turn. According to this model, the β-strands have to be twisted in each monomer by 15°. Here, in our simulations, although the starting conformation of the A8 octamer is planar, its equilibrium structure is twisted, as indicated in Figure 7 ▶. However, the interstrands twist angle of the A8 octamer is much smaller, only 5° instead of the expected 15°. Two possible reasons may explain the smaller twist angle: First, the small size of the methyl group does not allow a large twist angle. With a large twist angle, the methyl groups cannot effectively be in contact and still maintain a stable β-sheet complex. Second, despite the fact that for octamers (and hexamers) the twist angle is only 5°, it may increase as the small protofilament propagates into large fibrils. In our subsequent simulations of Aβ peptide fragments, we found that the twist angles strongly depend on the sequence and orientation of the β-strands. The strands twist to make optimal interstrands interactions (Ma and Nussinov 2002).

Molecular events conformational conversion and propagation

The highly stable A8 octamer is a good candidate for studying the mechanism of nucleation and conformational conversion. Consequently, we next investigate the ability of the A8 octamer to act as a nucleation site to lock an added monomer or to convert it into a β-strand conformation with subsequent locking. To probe this possibility, we performed two sets of simulations. First, we simulated the behavior of an additional α-helical A8 monomer that was placed on the surface of the equilibrated A8 octamer (at 350 K and 400 K, Fig. 8a ▶). In the second set, we simulated the preformed ordered octamer surrounded by eight additional random structured polyalanine monomers (at 350 K and 400 K, Fig. 8b ▶). We have not observed the growth of the oligomer. However, the simulations revealed some important events in the interaction of the added A8 monomers and the preformed A8 octamer. This observation leads us to speculate on possible mechanisms of amyloid growth.

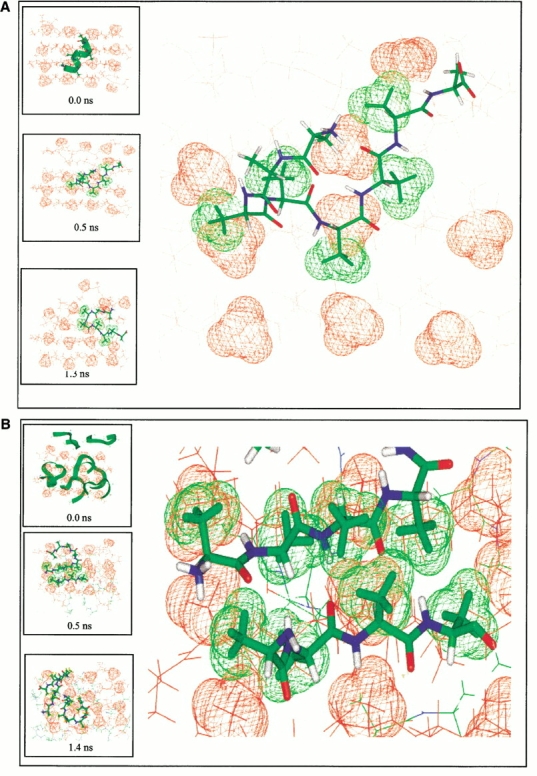

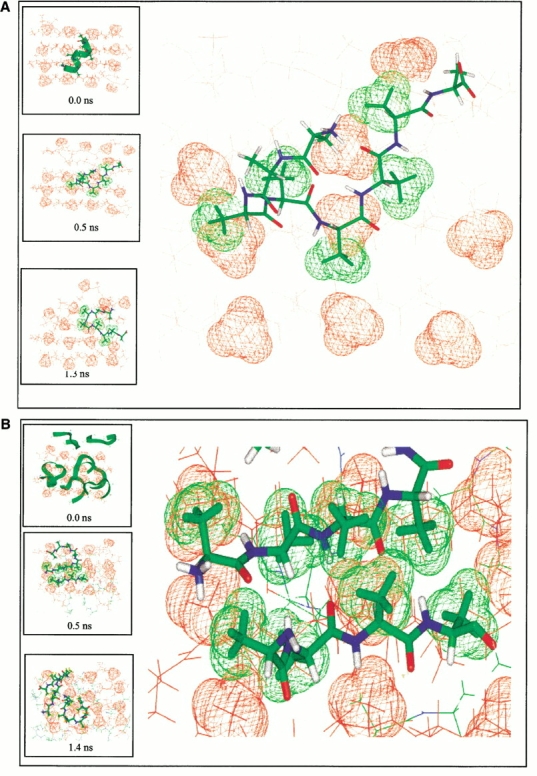

Fig. 8.

The conformational change of additional octa-alanines (green color) placed on the polyalanine octamer surface (red). Only methyl groups on the top of the surface are shown for the octamer. The large figures are enhanced views of the atomic details of the surface matching. The inserted boxes are snapshots from the simulations. (a) Simulation of a preformed octamer plus an α-helical octa-alanine at 350 K. The green methyl groups of (A3A4A5A6A7) in the additional octa-alanine indicate the match with the methyl groups on the octamer surface (in red). (b) Simulation of a preformed octamer plus eight random octa-alanines at 400 K. The enlarged figure shows the perfect match of the β-strands patches on the lateral surface, which lasts about 0.25 ns. No β-interactions are observed between the octamer and the random peptides along the edge.

We followed the conformational changes of the added A8 monomers. In reference simulations, an isolated A8 monomer solvated with water molecules was observed to be completely random and flexible at 350 K. When put on the hydrophobic surface of the preformed β-sheet of the octamer, the added A8 monomer is observed to spend more time around the β-region of the Ramachandran plot. Figure 9 ▶ compares the ξ torsional angle trajectories of the isolated A8 monomer with those near the octamer surface. In the Ramachandran plot, the β structure is characterized by ξ torsional angle values ∼0° to 180° and φ angle ∼−30° to −180°. Because both α and β regions cover similar φ values, we only plot the ξ trajectories here. As may be seen in Figure 9 ▶, in the course of the simulation more ξ torsional angles have changed to β-regions in those peptides that are near the octamer surface, compared with the peptide in its isolated state.

Fig. 9.

Comparison of ξ angle changes of polyalanine in isolated state (a) and on the octamer surface (b, 350 K simulation; c, 400 K simulation). The angles are ξ1: N2-Cα2-C2-N3; ξ2: N3-Cα3-C3-N4; ξ3: N4-Cα4-C4-N5; ξ4: N5-Cα5-C5-N6; ξ5: N6-Cα6-C6-N7; |gR6: N7-Cα7-C7-N8.

In the set one simulations (ordered octamer plus one helical polyalanine), we observed that it was able to retain an α-helical structure only for a short time (20 picoseconds [ps] at 350 K and 3 ps at 400 K). It then changed to a random coil on the octamer surface. At 350 K, the random coil lasted for about 0.4 ns. The β-structure appeared at 0.45 ns and lasted for ∼0.4 ns. Initially, only three residues (A4A5A6) had β-like structure. Gradually, additional residues were converted to a β-conformation (A3 and A7A8). As seen in Figure 8 ▶, this partial β-polyalanine still moves around on the octamer surface. Note that one strand of the octamer is perturbed by the additional polyalanine. At the end of the simulation, this peptide moves to the disrupted corner of the octamer and remains there as a curved strand with a β-turn. In the 400-K simulation, a tri-residue β-strand patch (A1A2A3) appeared earlier in this peptide, already at ∼30 ps. This tri-residue β-patch settled on the octamer surface at ∼70 ps. It stayed locked at this site for 0.8 ns while another portion of the peptide moved rapidly around the octamer surface.

In the set two simulations (ordered octamer plus eight random polyalanines), the system behavior differs between the 350-K and the 400-K simulations. In the 350-K run (2 ns), no matching of the β-strand patch with the octamer hydrophobic surface is observed. The random monomers interfere with each other, competing for the limited ordered surface. However, in the 400-K simulations (4 ns), we observe the important feature of the β-strand patch matching and propagation. At 400 K, the structural changes accelerate and the hydrophobic effect is more prominent than at 350 K. β-strand patches are frequent and are observed to be matched to the surface with different lifetimes. One of the three residue β-strand patches locked onto the surface at ∼170 ps, lasting essentially through the entire simulation. Furthermore, this three residue β-strand patch binds to an incoming β-strand patch from another peptide, illustrating key events of oligomer propagation on the ordered surface (Fig. 8b ▶).

There are two possible ways by which the changing environment can affect fibril growth: (1) hydrogen bonding, that is, the seed readily binds the incoming monomer through hydrogen bonding in the direction of the fibril axis with a stepwise amyloid growth, and (2) hydrophobic interactions. Hydrophobic interactions do not require the incoming monomer to bind directly at the end of the fibril. Rather, it is more likely that hydrophobic interactions lead to an initial monomer binding in a direction that is perpendicular to the fibril axis, which has a colliding cross-section area far larger than the fibril ends. The binding of the incoming monomer at the fibril hydrophobic surface changes the folding environment of the peptide and stabilizes the β-conformation, with subsequent movement to the ends, leading to fibril growth.

Our simulations do not show the direct growth of seeds in either direction. This may be because of the limitations in our simulations. The limited simulation time (nanoseconds) cannot reproduce all aggregation events (with a timescale of seconds or hours). This explains why we do not observe the complete rearrangement of the added monomers onto preformed oligomers. Nevertheless, the molecular events revealed by the simulations indicate that the hydrophobic interaction mechanism is more consistent with the nucleated conformational conversion and replication mechanism (Serio et al. 2000). Serio et al. (2000) have suggested that the changed environment allows the peptides to (1) slowly rearrange and form structured nuclei; (2) undergo a conformational change as they associate with the seed-nuclei; and (3) the peptides stay unlocked; however, may form conformations that assemble more rapidly once a seed-nucleus is added.

The conformational change of the additional A8 peptides and their association with the "preformed" octamer surface may indicate a conformational selection process. The preexisting ordered hydrophobic pattern on the octamer surface acts as a conformational trap for an incoming peptide, with a suitably matching conformation. The seed does not actively induce or catalyze a conformational change. In the simulations, the initial β-like patch occurred away from the surface. In the next step, the β-like patch of the peptide matched with the oligomer surface and stabilized. Other unmatched residues did not undergo immediate conversion. They remained flexible until the β-like patch locked onto the surface. The catalytic power of the hydrophobic surface derives from the stabilization it imparts to the preexisting peptide pattern through a matching configuration. In the monomeric state, the β-like patch might rapidly interconvert to another conformation. Hence, it is via conformational selection that it associates into a more stable locked conformation. However, it should be noted that it is hard to infer a detailed mechanism on the basis of our limited simulations. More thorough studies are required to fully understand the intriguing problem of amyloid growth.

Discussion

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain amyloid formation, particularly for the prion proteins (Jarrett and Lansbury 1993; Serio et al. 2000). Two kinetic models have been suggested for the transformation and propagation of the prion protein in bovine (Prusiner 1991; Jarrett and Lansbury 1993) from PrPC to PrPSc. According to the first model, the rate-limiting step is the irreversible autocatalytic conversion of a monomeric PrPC to a monomeric PrPSc. The second step (Prusiner 1991) is a fast oligomerization of PrPSc. In contrast, the second model proposes a fast equilibrium interconversion between the monomeric PrPC and the monomeric PrPSc precursor. Here, the rate-limiting step is the formation of a PrPSc oligomer seed. The oligomer then acts as a nucleus for amyloid growth (Jarrett and Lansbury 1993). Recently, Serio et al. (2000) have proposed a third, nucleated conformational conversion and replication mechanism. In all models, the key step is the formation of an amyloid nucleus.

The question then arises as to what is the minimum size of the nucleus. In a recent mathematical model (Masel et al. 1999) of the nucleated polymerization mechanism, the minimal nucleation size has been proposed to be a 6-mer. By this mechanism, the formation of a dimer, trimer up to the hexamer is a rapid association/dissociation process, with the equilibrium strongly favoring the dissociation process, making it extremely difficult to form a hexamer. However, the equilibrium shifts and favors polymerization after the formation of a hexamer, leading to an accelerated polymer growth.

Confirmation of the seed formation mechanism with ab initio simulations is beyond our current capabilities. There are two critical steps before the formation of a stable seed. (1) The change of a peptide chain from either a random or an ordered (α-helix) conformation to a β-conformation is a slow process on the order of microseconds or longer. (2) The aggregation of the peptides to a stable seed is a considerably slower process and takes hours or even weeks to incubate to reach its formation. Our present studies are unable to address these two elementary steps. Instead, we focus on the stabilities of possible β-strand oligomers. Our studies confirm that the oligomer stability increases with its size.

Three factors contribute to peptide oligomer stabilities, namely, hydrogen-bonding interactions, hydrophobic interactions, and dipole interactions. For short peptides, dipole interactions may play an important role in determining favored β-strands orientation. In principle, antiparallel β-strands have attractive dipole interactions, whereas parallel β-strands have repulsive dipole interactions. However, as all three factors change with β-strands orientation, we cannot separate between them.

Our results regarding the stability of parallel and antiparallel arrangements do not readily apply to other peptide systems. Parallel or antiparallel arrangement in an amyloid is strongly sequence-dependent. Balbirnie et al. (2001) studied an amyloid-forming peptide (GNNQQNY) from the yeast prion Sup35 and found the precisely opposite arrangements in which parallel β-sheets are in an antiparallel contact with adjoining sheets. Aβ-peptide fragments similarly show a sequence-dependent change in the orientation of the β-strands. A fragment (residues 16–22) from the Aβ peptide forms an amyloid with an antiparallel β-sheet organization (Balbach et al. 2000), whereas amyloid fibrils derived from Aβ residues 10–35 have parallel β-sheet interactions (Benziger et al. 2000). For hydrophobic residue-rich sequences, it is very likely that hydrophobic interactions also determine whether it is a parallel or an antiparallel β-sheet, depending on the matching of the hydrophobic residues. In our case, because our peptides are symmetric, antiparallel orientation is favorable. Such a conclusion is consistent with the polyalanine rich silk structure (Rathore and Sogah 2001).

Our simulations might be an indication of the importance of an ordered oligomer surface in the conformational selection and thus in the conformational conversion through equilibrium shift toward the conformation of the bound peptide. In a mutational analysis of designed peptides and amyloid fibril formation, Takahashi et al. also emphasize the importance of matching between hydrophobic surfaces for a well-organized assembly into an amyloid fibril (Takahashi et al. 2000). However, in the cross-β model, the growth direction is along the fibril axis. In our simulations, the conversion of the added peptides is initially in a direction perpendicular to the fibril axis, where the hydrophobic effect predominates, and the larger surface area increases the chance of collision. This requires shifting a newly formed oligomer from the lateral surface to the edge of the fibril. Such oligomer shifting may be inferred from the recent experimental findings that led to the nucleated conformational conversion model and the replication of a protein-based genetic information mechanism. Serio et al. (2000) have observed that rotation greatly enhances the nucleating activity. They suggested that rotation dissociates overly large complexes and/or increases the chance of effective collisions. The dissociation of the overly large complexes is consistent with the requirement of shifting the newly formed oligomer to the edge of the fibril, leading to both hydrogen-bond formation and hydrophobic interactions between consecutive oligomers in the fibril axis direction. Electron micrographs of gold-labeled seeds showed that amyloid fibers grow bidrectionally, that is, from both ends. However, occasionally, fibers showed gold labeling at one end only (Scheibel et al. 2001). Scheibel et al. explained the unidirectional growth as steric hindrance of bound gold particles on fiber ends or improper folding at fiber ends that blocks the addition of new material. Their first explanation of steric hindrance is also consistent with the importance of the surface perpendicular to the fibril axis.

Conclusions

The kinetics of amyloid formation is characterized by an initial slow lag phase and a subsequent rapid propagation. Experimentally, concentration-dependent aggregation indicated that the first step in the aggregation process is the formation of a micelle (Blondelle et al. 1996; Lomakin et al. 1996; Lomakin et al. 1997). This occurs when the concentration is higher than a critical micellar concentration. Our simulations probing the stability of the peptide-sheet complexes are a simplification of these processes. Nevertheless, they allow us to address several key questions: (1) How is the initial seed stabilized? (2) What is the smallest size that a seed can be? (3) What is the mechanism through which the seed catalyzes the addition of β-strands? Through the simulation we have established that an octamer is stable enough to be a seed and that the driving force for stabilization is the hydrophobic effect. The observation that the β-sheet oligomer is stable only when the size reaches 6 to 8 peptides doomed its slow formation and a long lag phase. Our simulations further indicate that fibril elongation is via seed–strand conformational selection rather than through a conformational change induced by the seed.

Materials and methods

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed in the canonical ensemble (NVT) at several temperatures using the program Discover 2.98. All atoms of the system were considered explicitly, and their interactions were computed using the CFF91 force field with periodic boundary conditions. The potential energy functions include bond stretching, angle bending, torsion, and out-of-plane angle deformation terms and contain cross-terms to describe the couplings between bond–bond, angle–angle, bond–angle, bond–torsion, torsion–angle, and angle–angle–torsion (Maple et al. 1998). A distance cutoff of 10 Å was used for van der Waals interactions and electrostatic interactions. The time step in the MD simulations was 1 femtosecond (fs) (10−15 s). Trajectories of peptide oligomers were saved every 1 ps (10−12 s). Previously, we used the same methods and force field to simulate a β-hairpin from protein G. A good agreement with NMR experimental results was obtained both with respect to the hairpin structure and stability (Ma and Nussinov 2000).

Our model systems include the peptide (AGAAAAGA and AAAAAAAA) oligomers (trimers, tetramers, hexamers, and octamers) solvated with ∼3000 water molecules in a 46*46*46 Å3 cubic box. The effective water density in the solvation box was 1.006 g/cm3. The starting conformations of the peptide complex are generated to represent a β-sheet cluster. Standard Ramachandran angle was used to generate the β-strands, using the Biopolymer module in INSIGHTII molecular modeling package (Accelrys Software 2000). A β-sheet may have various conformations. We use only simple planar sheet as a starting conformation to minimize a possible introduced bias.

Peptide chains are transformed to the conformation of linear β-strands. The chains are then placed with predefined parallel or antiparallel orientations and different layers. The hydrogen-bonded chains were placed at ∼5.0 Å separation, and the distance between the sheets was set to ∼10 Å, which corresponds to the average distance in a cross-β structure (Sunde and Blake 1998). All starting conformations were built using the INSIGHTII molecular modeling package (Accelrys Software 2000). The oligomers are next solvated with water molecules. The oligomers and water molecules are initially minimized with 500 steps to relax the local forces. Subsequently, the system was heated from 0° to the desired temperature in 10,000 steps. Unless specified, most simulations were performed at 330 K. However, certain simulations are run at 300 K, 350 K, or 400 K, depending on the purpose of the simulations. These temperatures offer the convenient conditions for testing the stabilities of peptide oligomers within our nanoseconds simulation timescales. The simulation time is still much shorter than in actual experiments.

The conditions of the simulations of preformed polyalanine octamer plus additional polyalanine monomers are the same as for the other systems, within a periodic box of 46*46*46 Å3. The conformations of the random structures are taken from simulations of isolated octa-alanines in water. We put three random peptides on each ordered hydrophobic surface and two along one edge of the ordered octamer. The octamer and the random peptides are separated initially by a 5-Å layer of water molecules.

To monitor the stability of the oligomer, we analyze the change in the number of hydrogen bonds and the methyl group contacts between the β-strands. The hydrogen bond cutoff was 2.5 Å, and the interstrands methyl group contacts were counted for the methyl groups with Cβ distance within 5.0 Å. The trajectory analysis was performed using the DeCipher module in the INSIGHTII molecular modeling package (Accelrys Software 2000).

Because of the huge number of conformational states studied in this work, most simulation times are ∼1–2 ns, with the stable conformations being tested for up to 4 ns. Multiple simulations were performed for several oligomers, with three simultaneous simulations for each tetramer oligomer and two parallel simulations for the most stable octamer conformers. The total cumulative simulation times for all systems are ∼50 ns. All computations were run in parallel using eight processors in the Origin 2000 machine.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jacob V. Maizel for encouragement and for helpful discussions. In particular we thank Dr. David Eisenberg for critical reading and making very constructive suggestions on a preliminary form of this manuscript. The computation times are provided by the National Cancer Institute's Frederick Advanced Biomedical Supercomputing Center. The research of Ruth Nussinov in Israel has been supported in part by the Magnet grant, by the Ministry of Science grant, by the "Center of Excellence in Geometric Computing and its Applications" funded by the Israel Science Foundation (administered by the Israel Academy of Sciences), and by the Adams Brain Center grant. This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract number NO1-CO-12400. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the view or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organization imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.4270102.

References

- Azriel, R. and Gazit, E. 2001. Analysis of the minimal amyloid-forming fragment of the islet amyloid polypeptide. J. Biol. Chem. 276 34156–34161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbach, J.J., Ishii, Y., Antzutkin, O.N., Leapman, R.D., Rizzo, N.W., Dyda, F., Reed, J., and Tycko, R. 2000. Amyloid fibril formation by Aβ16–22, a seven-residue fragment of the Alzheimer's β-amyloid peptide, and structural characterization by solid state NMR. Biochemistry 39 13748–13759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbirnie, M., Grothe, R., and Eisenberg, D.S. 2001. An amyloid-forming peptide from the yeast prion Sup35 reveals a dehydrated β-sheet structure from amyloid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98 2375–2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benziger, T.L.S., Gregory, D.M. Burkoth, T.S., Miller-Auer, H., Lynn, D.G., Botto, R.E., and Meredith, S.C. 2000. Two-dimensional structure of β-amyloid(10–35) fibrils. Biochemistry 39 3491–3499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondelle, S.B., Forood, B., Houghten, R.A., and Perez-Paya, E. 1996. Polyalanine-based peptides as models for self-associated β-pleated-sheet complexes. Biochemistry 36 8393–8400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrell, R.W. and Lomas, D.A. 1997. Conformational disease. Lancet 350 134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesebro, B. 1998. BSE and prions: Uncertainties about the agent. Science 279 42–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasset, M., Baldwin, M.A., Lloyd, D.H., Gabriel, J-M., Holtzman, D.M., Cohen, F., Fletterick, R., and Prusiner, S.B. 1992. Predicted α-helical regions of the prion protein when synthesized as peptides form amyloid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 89 10940–10944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass, C. and Strooper, B.D. 1999. The presenilins in Alzheimer's disease—proteolysis holds the key. Science 286 916–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, E., Burke, R.M., and Doig, A.J. 2000. Inhibition of toxicity in the β-amyloid peptide fragment β-(25–35) using N-methylated derivatives. J. Biol. Chem. 275 25109–25115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson, L.L., Mortishire-Smith, R.J., Pollack, S.J., and Shearman, M.S. 1995. The toxicity in vitro of β-amyloid protein. Biochem. J. 311 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett, J.T. and Lansbury, Jr. P.T. 1993. Seeding "one-dimensional crystallization" of amyloid: A pathogenic mechanism in Alzheimer's disease and scrapie? Cell 73 1055–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortemme, T., Ramirez-Alvarado, M., and Serrano, L. 1998. Design of a 20-amino acid, three-stranded β-sheet protein. Science 281 253–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomakin, A., Chung, D.S., Benedek, G.B., and Kirschner, D.A. 1996. On the nucleation and growth of amyloid β-protein fibrils: Detection of nuclei and quantitation of rate constants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93 1125–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomakin, A., Teplow, D.B., Kirschner, D.A., and Benedek, G.B. 1997. Kinetic theory of fibrillogensis of amyloid β-protein Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94 7942–7947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, A., Razzaboni, B., Weir, G.C., and Yankner, B.A. 1994. Pancreatic islet cell toxicity of amylin associated with type-2 diabetes mellitus. Nature 368 756–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B. and Nussinov, R. 2000. Molecular dynamic simulations of a β-hairpin fragment of protein G: Balance between side-chain and backbone forces. J. Mol. Biol. 296 1091–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2002 . Stabilities and conformations of Alzheimer's β-amyloid peptide oligomers (Aβ16–22, Aβ16–35 and Aβ10–35): Sequence effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Maple, J.R., Hwang, M.J., Jalkanen, K.J., Stockfisch, T.P., and Hagler, A.T. 1998. Derivation of class II force fields: V quantum force field for amides, peptides, and related compounds. J. Comput. Chem. 19 430–458. [Google Scholar]

- Masel, J., Jansen, V.A.A., and Nowark, M.A. 1999. Quantifying the kinetic parameters of prion replication. Biophys. Chem. 77 139–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike, C.J., Walencewicz-Wasserman, A.J., Kosmoski, J., Cribbs, D.H., Glabe, C.G., and Cotman, C.W. 1995. Structure-activity analyses of β-amyloid peptides: Contributions of the β 25–35 region to aggregation and neurotoxicity. J. Neurochem. 64 253–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner, S.B. 1991. Molecular biology of prion diseases. Science 252 1515–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1998. Prions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95 13363–13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin, J., Wyttenbach, A., and Rubinsztein, D.C. 2000. Intracellular green fluorescent protein-polyalanine aggregates are associated with cell death. Biochem. J. 348 15–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raschke, T.M., Tsai, J., and Levitt, M. 2001. . Quantification of the hydrophobic interaction by simulations of the aggregation of small hydrophobic solutes in water Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98 5965–5969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathore, O. and Sogah, D.Y. 2001. Self-assembly of β-sheets into nanostructures by poly(alanine) segments incorporated in multiblock copolymers inspired by spider silk. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 123 5231–5239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibel, T., Kowal, A.S., Bloom, J.D., and Lindquist, S.L. 2001. Bidirectional amyloid fiber growth for a yeast prion determinant. Curr. Biol. 11 366–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serio, T.R., Gashikar, A.G., Kowal, A.S., Sawicki, G.J., Moslehi, J.J., Serpell, L., Arnsdorf, M.F., and Lindquist, S.L. 2000. Nucleated conformational conversion and the replication of conformational information by a prion determinant. Science 289 1317–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearman, M.S., Ragan, C.I., and Iverson, L.L. 1994. Inhibition of PC12 cell redox activity is a specific, early indicator of the mechanism of β-amyloid-mediated cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 91 1470–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrer, H.E., Santoso, A., Szoka, F.C., and Weissman, J.S. 2000. Evidence for the prion hypothesis: Induction of the yeast [PSI+] factor by vitro-converted Sup35 protein. Science 289 595–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunde, M. and Blake, C.C.F. 1998. From the globular to the fibrous state: Protein structure and structural conversion in amyloid formation. Q. Rev. Biophys. 31 1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, Y., Ueno, A., and Mihara, H. 2000. Mutational analysis of designed peptides that undergo structural transition from α helix to β sheet and amyloid fibril formation. Structure 8 915–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenidis, K., Waldner, M., Bernhagen, J., Fischle, W., Bergmann, M., Weber, M., Merkle, M., Voelter, W., Brunner, H., and Kapurniotu, A. 1999. Identification of a penta- and hexapetide of islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) with amyloidogenic and cytotoxic properties. J. Mol. Biol. 295 1055–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzi, E., Hölzmann, G., and Seelig, J. 1994. Reversible random coil-β-sheet transition of the Alzheimer β-amyloid fragment (25–35). Biochemistry 33 1345–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman, J., Gowda, G.A.N., and Balaram, P. 2002. Design and construction of an open multistranded β-sheet polypeptide stabilized by a disulfide bridge. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124 4987–4994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanuy, D., Ma, B., and Nussinov, R., 2002. Short peptide amyloid organization: Stabilities and conformations of the islet amyloid peptide NFGA1L. Biophys. J. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]