Abstract

Desulfovibrio gigas desulforedoxin (Dx) consists of two identical peptides, each containing one [Fe-4S] center per monomer. Variants with different iron and zinc metal compositions arise when desulforedoxin is produced recombinantly from Escherichia coli. The three forms of the protein, the two homodimers [Fe(III)/Fe(III)]Dx and [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, and the heterodimer [Fe(III)/Zn(II)]Dx, can be separated by ion exchange chromatography on the basis of their charge differences. Once separated, the desulforedoxins containing iron can be reduced with added dithionite. For NMR studies, different protein samples were prepared labeled with 15N or 15N + 13C. Spectral assignments were determined for [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx and [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx from 3D 15N TOCSY-HSQC and NOESY-HSQC data, and compared with those reported previously for [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx. Assignments for the 13Cα shifts were obtained from an HNCA experiment. Comparison of 1H–15N HSQC spectra of [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx and [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx revealed that the pseudocontact shifts in [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx can be decomposed into inter- and intramonomer components, which, when summed, accurately predict the observed pseudocontact shifts observed for [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx. The degree of linearity observed in the pseudocontact shifts for residues ≥8.5 Å from the metal center indicates that the replacement of Fe(II) by Zn(II) produces little or no change in the structure of Dx. The results suggest a general strategy for the analysis of NMR spectra of homo-oligomeric proteins in which a paramagnetic center introduced into a single subunit is used to break the magnetic symmetry and make it possible to obtain distance constraints (both pseudocontact and NOE) between subunits.

Keywords: NMR, pseudocontact shifts, desulforedoxin, [Fe-4S] center, paramagnetic protein, Desulfovibrio gigas

The simplest iron–sulfur protein isolated from sulfate reducing bacteria is rubredoxin (Rd). The rubredoxins are low molecular weight (6–7 kD) proteins containing one iron center (Sieker et al. 1994). The metal atom is bound by four cysteine residues with a conserved binding sequence of the type: -C-X-Y-C-. . .. . ..-C-X-Y-C-. In the oxidized native state, the iron is high-spin Fe(III) with S = 5/2, and in the reduced state, the iron is high-spin Fe(II) with S = 2. The center has a distorted tetrahedral geometry. Several X-ray structures are available for Rds from various bacterial sources in both oxidation states (Watenpaugh et al. 1980; Frey et al. 1987; Dauter et al. 1992; Day et al. 1992).

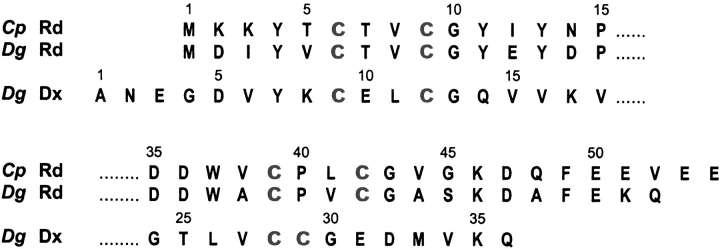

Desulfovibrio gigas desulforedoxin (Dx) (Moura et al. 1977) is a [Fe-4S] protein with a metal binding sequence motif similar to that of Rd, as shown in Figure 1 ▶. Dx is a homodimer of two 4-kD polypeptide chains, each binding a single Fe atom. Dx and Rd give rise to distinctly different visible, EPR, and Mössbauer spectra (Moura et al. 1996). X-ray structures have been determined for different metal derivatives of Dx: Fe, In, Cd, and Ga (Archer et al. 1995, 1999). NMR structures have been determined for the Zn and Cd forms of Dx (Goodfellow et al. 1996, 1998); although the structure of Dx in solution is similar to that in the solid state, differences were observed in hydrogen bonding (Goodfellow et al. 1996, 1998). A study of two mutants of Dx showed that the differences in geometry at the metal centers in Rd and Dx result from the different spacing of the C-terminal cysteine pair in the two proteins (Fig. 1 ▶) (Yu et al. 1997; B. J. Goodfellow, F. Rusnak, I. Moura, C. S. Ascenso, and J. J. Moura, in press). The largest difference between the metal centers of Rd and Dx is in one of the S-M-S angles (Archer et al. 1995, 1999). The Dx protein has only been found in cellular extract of D. gigas, and its function in this bacteria has still not been identified. A Dx-like domain has, however, been found in the N-terminus of desulfoferredoxin proteins that have been shown to possess superoxide reductase activity (Rusnak et al. 2002).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of metal-binding motifs from the amino acid sequences of Clostridium pasteurianum rubredoxin (CpRd), Desulfovibrio gigas rubredoxin (Dg Rd), and the Desulfovibrio gigas desulforedoxin monomer (Dg Dx). Cysteine residues that ligate the metal are highlighted in gray.

NMR spectra of paramagnetic systems, such as the native iron-containing forms of Rd and Dx, show the effects of strong hyperfine interactions between the unpaired electrons and nearby NMR-active nuclei. These interactions result in large chemical shift perturbations and efficient relaxation mechanisms. Standard approaches to protein structure determination in solution by NMR spectroscopy, based on NOEs and J couplings, can be severely hindered in these cases. However, these electron–nuclear interactions contain other kinds of information (Banci et al. 1991; Bertini and Luchinat 1998). Metal-centered dipolar interactions, which are through-space in nature, have been studied in proteins for many years. In heme systems, anisotropic magnetic susceptibility tensors have been determined and used to refine structures through minimization of differences between calculated and experimental pseudocontact shifts (Emerson and La Mar 1990). In addition, Bertini et al. have used pseudocontact chemical shifts (Banci et al. 1996, 1997, 1998a; Arnesano et al. 1998; Assfalg et al. 1998) and longitudinal relaxation rates (Bentrop et al. 1997) as constraints in protein structure determinations.

Extensive NMR studies of the rubredoxin from Clostridium pasteurianum (CpRd) carried out with protein samples labeled uniformly and/or selectively with 2H, 13C, and 15N have led to nearly complete assignment of 1H, 2H, 13C, and 15N signals from both the diamagnetic (Prantner et al. 1997; Volkman et al. 1997) and paramagnetic portions of the NMR spectra (Wilkens et al. 1998b) in both oxidation states of the protein. Large hyperfine shifts arising from Fermi contact (through-bond) interactions were observed for 1H, 2H, 13C, and 15N nuclei close to the iron center (Wilkens et al. 1998b). It was possible to reproduce the observed hyperfine shifts, 1H/2H isotope effects on 15N hyperfine shifts (Xia et al. 1998) and 15N relaxation rates (Wilkens et al. 1998a) through ab inito quantum mechanical calculations based on high-resolution X-ray structural models of the metal center. Comparison of calculated and experimental results showed that positions of atoms from protein groups close to the iron change as a function of the oxidation state. Nuclei more distant from the metal center also showed different chemical shifts in oxidized and reduced CpRd. The anisotropic magnetic susceptibility tensors for the two states were determined through analysis of field-dependent couplings in terms of the X-ray structure of oxidized CpRd, and these were used to predict chemical shift differences arising from pseudocontact interactions in the oxidized and reduced states. Excellent agreement between predicted and experimental chemical shifts validated the model and showed that the chemical shift differences observed for atoms more than 8 Å distant from the iron in the Fe(II) and Fe(III) forms of rubredoxin could be explained fully by electron–nuclear interactions with no change in the structure of the protein shell (Volkman et al. 1999).

A solution structure of the reduced form of the same protein, CpRd, has also been determined using standard NMR methodology and nonselective T1 measurements to give proton–metal distance constraints (Bertini et al. 1998). Owing to bleaching around the iron center the poorest definition was observed around the binding cysteines, although the position of the metal in relation to the rest of the protein was seen to improve as a result of the introduction of the paramagnetic constraints.

We have as a long-term goal a similar detailed examination of the NMR spectral properties of desulforedoxin, which has the added interest of two metal centers per homodimeric unit. During the overexpression and purification of Dx, it was found that a Zn(II) form could be purified along with the native Fe(III) form (Czaja et al. 1995). In addition, owing to the dimeric nature of Dx, a mixed metal form containing both Fe and Zn is also produced. The three forms can be separated by ion exchange chromatography as a result of their charge differences. We report here NMR investigations of [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx, [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, and [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx carried out with protein samples labeled uniformly with 15N and with 15N + 13C. These studies have resulted in extensive 1H, 15N, and 13Cα assignments for these molecules. In addition, because of the diamagnetism of zinc, the results have enabled the dissection of the intra- and intersubunit pseudocontact shifts for nuclei >8.5 Å distant from iron centers. The intra- and intersubunit 1H and 15N pseudocontact shifts were found to be strictly additive; this indicates that substitution of Fe(II) with Zn(II) does not lead to significant changes in the positions of atoms in the protein >8.5 Å from the metal center.

Results

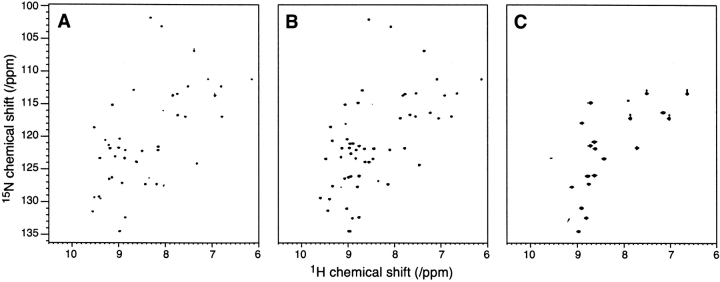

Figure 2 ▶ shows 1H–15N HSQC spectra of [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, and [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx. Distinct patterns of chemical shifts are clearly observed for the three different combinations of Zn- and Fe-containing Dx species, shown in Figure 3A–C ▶. Because [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx is a completely symmetric dimer, with identical local environments in the two monomers, a single set of resonances is observed for the 35 backbone NH groups of the 36-amino acid monomer as well as for the NH2 groups of the side chains of N2, Q14, and Q36 (Fig. 2A ▶). The 1H and 15N chemical shifts for [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx were assigned in a straightforward manner on the basis of previously reported 1H chemical shifts (Goodfellow et al. 1996) and the 3D 15N-edited NOESY and TOCSY spectra.

Fig. 2.

1H–15N HSQC spectra at pH 7.2 and 303 K of (A) [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, (B) Dx [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, and (C) [Fe(II)/Fe(II)].

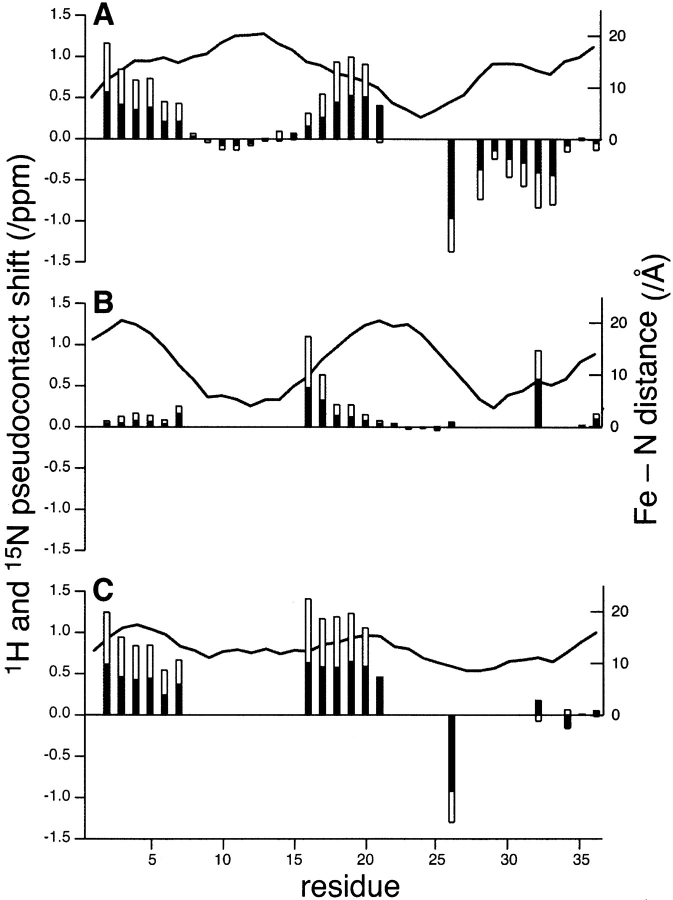

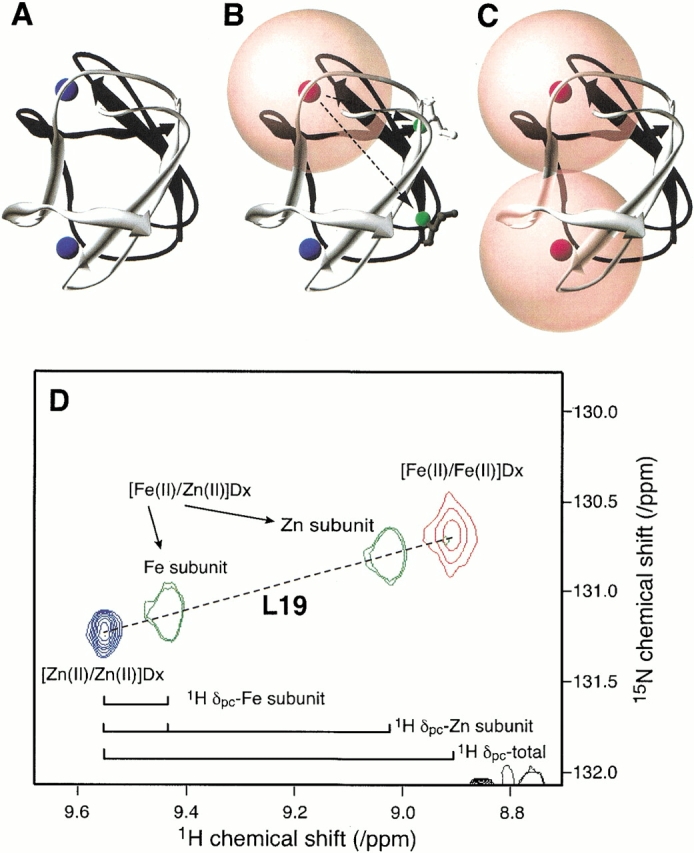

Fig. 3.

The metal composition of desulforedoxin affects backbone 1H and 15N chemical shifts. The X-ray structure of desulforedoxin (PDB ID: 1DXG) (Archer et al. 1995) is used to represent the three combinations of Fe and Zn species, (A) [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, (B) [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, and (C) [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx. In each case, one subunit of the dimeric desulforedoxin is colored black, and the other is colored white. Zn and Fe atoms are colored blue and red, respectively. In (B), the Fe and Zn atoms are bound to the black and white protein subunits, respectively. Spheres of radius 8.5 Å are centered on the Fe atoms, indicating the regions within which NMR signals are usually broadened beyond detection in 2D HSQC spectra. Fewer resonances should be observed from the homodimer containing Fe at both metal sites than from the heterodimer containing one Zn(II) and one Fe(II). In the case of [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx, the environments of corresponding nuclei in both subunits are equivalent; in the case of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, the environments of corresponding 15N nuclei in each subunit are different, as indicated for L19 (green) in (B). (D) Enlarged region of the superimposed 1H–15N HSQC spectra of (red) [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx, (green) [Fe(II)/ Zn(II)]Dx, and (blue) [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx. The cross peaks assigned to Leu19 are indicated in the figure. The proton pseudocontact shifts (1H Δpc) are indicated for the iron and zinc subunits of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx and for [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx. Note that these are additive and that the additivity holds also for the 15N pseudocontact shifts, as indicated by the colinearity of the set of four cross peaks.

The 1H–15N-HSQC spectrum of the mixed metal form of Dx (Fig. 2B ▶) shows 50 backbone NH cross peaks and 5 NH2 side-chain cross peaks. The larger number of peaks present in this spectrum is due to the symmetry of the dimer being broken by the nonequivalence of the two metal centers. From previous studies of CpRd, "bleaching" of 1H–15N cross peaks through the effects of paramagnetic broadening is expected for groups closer than about 8.5 Å to an iron center (Prantner et al. 1997; Volkman et al. 1997). Application of this principle to the structure of Dx, as shown in Figure 3B ▶, suggests that each iron center will "bleach" residues in both the iron-containing subunit as well as the other subunit. The extent of paramagnetic broadening from one Fe atom can be estimated using the X-ray structure: residues 1–8, 16–27, 32, and 34–36 of the Fe-containing monomer radius and residues 1–21 and 28–36 from the Zn containing monomer are more than 8.5 Å from the Fe (a total of 54, including five side-chain NH2 groups). The number of expected (52 backbone/five side chain) and observed (50 backbone/five side chain) cross peaks is very similar. Simple comparisons between the spectra of [Zn(II)/ Zn(II)]Dx and [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx led to assignments for residues 3–6, 19–26, 35, and 36 in the iron-containing subunit and residues 8–13, 29, 30, 34–36 in the zinc-containing subunit. All the remaining peaks in the 1H–15N HSQC spectrum of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx were assigned on the basis of 3D 15N-HSQC-TOCSY and 15N-HSQC-NOESY data.

[Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx also is a symmetric dimer; however, the paramagnetism of the iron centers obliterates signals from residues close to the iron centers, and only 17 backbone NH cross peaks and cross peaks from the NH2 groups of two side chains are seen (Fig. 2C ▶). Residues in Dx with 15N and 1HN atoms more than 8.5 Å away from both Fe atoms include 1–8, 16–21, 32, and 34–36 (18 residues, including two residues with side chain NH2 groups) (Fig. 3C ▶). It became apparent that the chemical shifts observed in the 1H– 15N HSQC spectrum of [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx could be predicted by adding the pseudocontact shifts from each of the subunits of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx. For example, Figure 3D ▶ shows an expansion of the two cross peaks of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx assigned to L19 compared to the single L19 resonance observed in the spectrum of [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx. The two distinct resonances observed for L19 in [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx arise due to their different positions in the structure relative to the single Fe atom, as illustrated in Figure 3 ▶. In this instance, a larger pseudocontact shift is observed for L19 in the Zn subunit than for the corresponding residue of the Fe subunit (Fig. 3D ▶), consistent with their relative distances from the paramagnetic center (Fig. 3B ▶). Addition of the pseudocontact shifts for each subunit in of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx (in both the 1H and 15N dimensions) yielded the position of the cross peak in the spectrum of [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx assigned to L19. The rationale for this is that nuclei in each symmetrical monomer of [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx experience both intrasubunit and intersubunit pseudocontact shifts. All peaks in the 1H–15N HSQC spectrum of [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx could be assigned by this approach.

Intra- and intersubunit pseudocontact contributions to the 1Hα and 13Cα chemical shifts of Dx were obtained through analysis of NMR spectra of samples labeled uniformly with 15N and 13C. Comparison of the 1HN and 15N assignments described above for [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx with the 3D HNCA spectrum of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx led to assignments for its 13Cα shifts. Constant time 1H–13C HSQC data sets were recorded for [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, and [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx. The 1Hα-13Cα cross peaks in the HSQC spectra of [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx and [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx were assigned by reference to the assignments described above and along with previous 1Hα assignments for [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx (Goodfellow et al. 1996). The 1H–13C cross peaks showed the same additivity of intrasubunit and intersubunit pseudocontact shifts observed with the 1H–15N cross peaks. This enabled the transfer of chemical shift assignments to the spectrum of [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx.

Figure 4 ▶ displays differences between the 1H and 15N chemical shifts of the diamagnetic Dx species ([Zn(II)/ Zn(II)]Dx) and those of the iron-containing Dx species (the Zn(II) subunit of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, the Fe(II) subunit of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, and homodimeric [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx) plotted as a function of the residue number. Also shown in the figure are distances between the iron and each nitrogen atom whose chemical shift is analyzed (in the case of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx this is the mean distance to both irons). Interestingly, the magnitudes of shift differences in the Zn-containing subunit of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx (Fig. 4A ▶) are generally larger than those for the Fe subunit (Fig. 4B ▶). This is partly due to the fact that more residues of the Fe subunit are `bleached,' owing to their close proximity to the paramagnetic center. The pattern of shift perturbations for [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx (Fig. 4C ▶) is quite different from those of either subunit of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx (Fig. 4B ▶), but correlates with their sum, as described above.

Fig. 4.

Chemical shifts of the paramagnetic, iron-containing desulforedoxin species of desulforedoxin relative to those of the diamagnetic species ([Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx) plotted as a function of residue number 1H (black bars) and 15N (white bars): (A) Zn-containing monomer of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx. (B) Fe-containing monomer of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx. (C) [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx. The lines trace the distances (in Å) between the iron and the nitrogen whose chemical shift is analyzed; in the case of [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx, this distance is the mean distance to both irons.

Discussion

Chemical shift differences between the observed peaks in the 1H–15N HSQC spectra of the three forms of Dx are expected to arise from pseudocontact shifts plus possible differences in protein conformation. Pseudocontact shifts have a 1/r3 dependence on the distance between the observed nucleus and the metal atom. Thus, resonances showing the smallest chemical shift differences are likely to arise from groups farthest from the iron center(s). Chemical shift differences between the completely diamagnetic [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx species and the three types of paramagnetically perturbed Dx subunits (Fig. 4 ▶) are generally consistent with this assertion, but in some instances residues equidistant from the Fe2+ center show dramatically different shift perturbations. For example, the backbone N atoms of residues 5 and 34 in the Zn subunit of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx are each 15.1 Å from the Fe2+, but are shifted 0.35 and −0.08 ppm from their positions in the HSQC spectrum of [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx. The presence of both positive and negative shift differences also clearly illustrates the lack of spherical symmetry in the dipolar effects of the paramagnetic center (Guiles et al. 1996; Volkman et al. 1999).

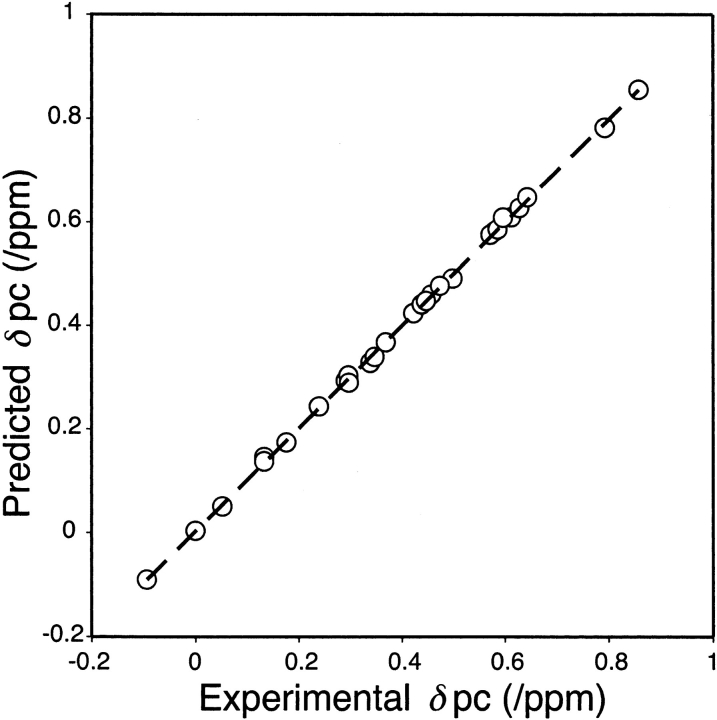

Ordinarily, detailed knowledge of the magnitude, rhombicity, and orientation of the magnetic susceptibility tensor is required for structural interpretation of pseudocontact shifts. In this case, however, the accuracy with which the sum of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx inter- and intramonomer pseudocontact shifts predicts the measured shifts in [Fe(II)/ Fe(II)]Dx provides a direct measure of structural similarity for the different Dx species. Any large differences between the experimental shifts of [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx and those predicted from adding the intra- and intersubunit pseudocontact shifts of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx to the diamagnetic shifts of [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx would indicate that structural changes result from substitution of a Zn atom for an Fe atom. Figure 5 ▶ shows the correlation between the experimental and predicted 1HN and 1Hα chemical shifts for [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx. The slope is very close to unity, and the off-line deviations are small. As mentioned above, only signals from residues 2–6, 16–21, 26, 32, and 34–36 are observable in the HSQC spectra of [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx, owing to the bleaching effect of the iron atoms. The close agreement between predicted and observed shifts indicates that structural changes resulting from replacement of Fe(II) by Zn(II) are minimal for those atoms observed, that is, those farther than ∼8.5 Å from the site of the metal replacement.

Fig. 5.

Correlation between the observed (ΔPC)exp and calculated (ΔPC)pred 1HN and 1Hα pseudocontact shifts for [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx. The dashed line represents the linear best fit, with a slope of 0.9941 and correlation coefficient of 0.9994.

How close can a backbone amide be to Fe(II) and still be observed? According to the X-ray structure of Dx, L26 of the Zn(II) subunit is 7.7 Å from the iron in the Fe(II) subunit; its signal was observed, albeit as a weak peak. This result for Dx is comparable with that for reduced Cp Rd in which a 1H-15N HSQC signal was observed from I12 whose HN is 7.6 Å from the iron (Prantner et al. 1997; Volkman et al. 1997). On the other hand, being farther from the iron does not guarantee that the signal will be observed. No signal was observed for K8 of the Fe(II) monomer of [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, which is 9.5 Å from Fe(II).

The finding that the structures of the different Dx species are similar suggests that it will be feasible to use the wealth of experimental pseudocontact shifts determined for [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx as constraints for refinement of the solution structure of Dx allowing the geometry at the metal center, and subsequently the H-bonding network at the center, to be probed. This will require knowledge of the orientation and magnitude of the magnetic susceptibility anisotropy (Δχ) of the paramagnetic center (Banci et al. 1998b; Wang et al. 1998). Δχ can be determined by measuring magnetic field-dependent 1H–15N and/or 1Hα–13Cα residual dipolar couplings and fitting them to the relatively low-resolution X-ray structure for Dx (Tjandra et al. 1996; Ottiger and Bax 1998; Volkman et al. 1999). Work along these lines is in progress.

Desulforedoxin is an example of an oligomeric protein containing identical subunits. Structural information for such molecules is hindered by the magnetic equivalence of signals from each subunit, which complicates the assignment of observables (such as NOEs) to intrasubunit and intersubunit interactions. One way of breaking this symmetry is to produce oligomers containing subunits with different stable isotope labeling patterns (e.g., a dimer one with 13C- and one with 15N-labeled subunit). The results reported here suggest another strategy: production of an oligomer containing one subunit with a paramagnetic center that produces pseudocontact shifts. The paramagnetism will break the degeneracy between chemical shifts of the paramagnetic-containing subunit and those of the other subunits. Further, the pseudocontact shifts can provide additional intra- and intersubunit structural constraints.

Materials and methods

Competent BL21(DE3) cells were transformed with the pT7–7 cloning vector containing the dsr gene (Czaja et al. 1995). A 25-μL aliquot of a fresh LB broth culture containing ampicillin (0.1 mg/mL) was used to inoculate 25 mL of M9 medium prepared with 15N-ammonium chloride and supplemented with 0.5% glucose (replaced with 13C-glucose for the doubly labeled sample), 0.5 μg/mL thiamine, 4% trace metals solution, and 0.1 mg/mL ampicillin. The trace metals solution contained the following (per liter): 69.9 g FeSO4•7H2O; 1.84 g CaCl2•2H2O; 640 mg H3BO3; 400 mg MnCl2•4H2O; 180 mg CoCl2•6H2O; 40 mg CuCl2•2H2O; 3.40 g ZnCl2; 6.05 g Na2MoO4•2H2O; 8 ml HCl 37%. Six milliliters of the resultant culture of an overnight growth at 37°C with shaking was used to inoculate six liters of an identical minimal medium. Expression of the dsr gene and purification of Dx were performed as previously described (Czaja et al. 1995). The yields were: 6.5 mg of [Fe(III)/Fe(III)]Dx, A280/A507 = 1.13; and 5.4 mg of [Fe(III)/Zn(II)]Dx, A280/A507 = 1.58. [Zn(II)/Zn(II)]Dx was prepared as described previously (Goodfellow et al. 1996).

Owing to the reduced paramagnetism (S = 2) in the Fe(II) state compared to the Fe(III) state, the iron-containing proteins were investigated in their reduced states. The proteins were reduced by adding one or two crystals of dithionite to a previously degassed (∼45 min) NMR sample under argon.

Each purified protein was exchanged through ultrafiltration (YM3 membrane, Amicon) with 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, at pH 7.2. The sample was concentrated to 450 μL in 90%/10% H2O/D2O. The final protein concentration was 1.6 mM for [Fe(II)/Fe(II)]Dx and 1 mM for [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx.

All spectra were acquired at a temperature of 303 K on the Bruker DMX 750 spectrometer at the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison, WI, at a 1H Larmor frequency of 750.13 MHz. Chemical shifts were referenced to external DSS (2,2 dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate) as 0 ppm (1H), and indirectly for 15N and 13C (Markley et al. 1998). 1H-15N HSQC spectra were acquired using the sequence of Wagner (Talluri and Wagner 1996) with water suppression via a 3-9-19 sequence with gradients (Piotto et al. 1992). Quadrature detection in the indirectly detected dimensions was obtained with the States-TPPI method (Marion and Wüthrich 1983). Each two-dimensional spectrum consisted of 2 K complex points in t2 and of 512 increments in t1 with spectral widths of 10,000 and 2778 Hz (at 750 MHz), respectively. A 13C CT-HSQC sequence (Tjandra and Bax 1997) was used to obtain the 1H/13C chemical shifts. Spectra contained 1 K complex points in t2 and 220 increments in t1 with spectral widths of 10,000 and 6250 Hz (at 750 MHz), respectively. Quadrature detection was achieved using the echo-antiecho method (Kay et al. 1992). The HNCA spectrum was acquired at 750 MHz using a sequence with gradient sensitivity enhancement (Kay et al. 1994) and contained 1 K complex points in t3, 64 increments in t2 and (15N dimension with echo-antiecho selection) 120 increments in t1 (13C dimension with States detection). Spectral widths were 10,000 (1H), 2500 (15N), and 6250 (13C) Hz. All data were weighted with squared cosine functions and processed using NMRPipe (Delaglio et al. 1995). The Sparky software program (T. D. Goddard and D. G. Kneller, SPARKY 3, University of California, San Francisco) was used in determining spectral assignments.

Acknowledgments

Work in Portugal was supported by PRAXIS: PCTI/1999/BME/36152 (J.J.G.M.). S.N. thanks JNICT for a predoctoral fellowship (BPD/16312/98), and B.J.G. thanks the Fundação Gulbenkian for a travel grant. Work at the University of Wisconsin–Madison was supported by NIH Grant GM58667 to J.L.M. NMR studies were carried out at the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison with support from the NIH Biomedical Technology Program (RR02301) and additional equipment funding from the University of Wisconsin, NSF Academic Infrastructure Program (BIR-9214394), NIH Shared Instrumentation Program (RR02781, RR08438), NSF Biological Instrumentation Program (DMB-8415048), and U.S. Department of Agriculture. NMR chemical shifts have been deposited at BioMagResBank (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu) under accession numbers: 5260 for [Fe(II)/ Fe(II)]Dx, 5271 for [Fe(II)/Zn(II)]Dx, and 5249 for [Zn(II)/ Zn(II)]Dx.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

Cp, Clostridium pasteurianum

Dg, Desulfovibrio gigas

Dx, desulforedoxin from Desulfovibrio gigas

Rd, rubredoxin

HSQC, heteronuclear single quantum coherence

NOESY, nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy

TOCSY, total correlation spectroscopy

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.0208802.

References

- Archer, M., Huber, R., Tavares, P., Moura, I., Moura, J.J., Carrondo, M.A., Sieker, L.C., LeGall, J., and Romao, M.J. 1995. Crystal structure of desulforedoxin from Desulfovibrio gigas determined at 1.8 Å resolution: A novel non-heme iron protein structure. J. Mol. Biol. 251 690–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer, M., Carvalho, A.L., Teixeira, S., Moura, I., Moura, J.J., Rusnak, F., and Romao, M.J. 1999. Structural studies by X-ray diffraction on metal substituted desulforedoxin, a rubredoxin-type protein. Protein Sci. 8 1536–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnesano, F., Banci, L., Bertini, I., and Felli, I.C. 1998. The solution structure of oxidized rat microsomal cytochrome b5. Biochemistry 37 173–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assfalg, M., Banci, L., Bertini, I., Bruschi, M., and Turano, P. 1998. 800 MHz 1H NMR solution structure refinement of oxidized cytochrome c7 from Desulfuromonas acetoxidans. Eur. J. Biochem. 256 261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banci, L., Bertini, I., and Luchinat, C. 1991. Nuclear and electron relaxation. VCH, Weinheim, Germany.

- Banci, L., Bertini, I., Bren, K.L., Cremonini, M.A., Gray, H.B., Luchinat, C., and Turano, P. 1996. The use of pseudocontact shifts to refine solution structures of paramagnetic metalloproteins: Met80Ala cyano-cytochrome c as an example. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Banci, L., Bertini, I., Savellini, G.G., Romagnoli, A., Turano, P., Cremonini, M.A., Luchinat, C., and Gray, H.B. 1997. Pseudocontact shifts as constraints for energy minimization and molecular dynamics calculations on solution structures of paramagnetic metalloproteins. Proteins 29 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banci, L., Bertini, I., De la Rosa, M.A., Koulougliotis, D., Navarro, J.A., and Walter, O. 1998. Solution structure of oxidized cytochrome c6 from the green alga Monoraphidium braunii. Biochemistry 37 4831–4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banci, L., Bertini, I., Huber, J.G., Luchinat, C., and Rosato, A. 1998b. Partial orientation of oxidized and reduced cytochrome b5 at high magnetic fields: Magnetic susceptibility anisotropy contributions and consequences for protein solution structure determination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 12903–12909. [Google Scholar]

- Bentrop, D., Bertini, I., Cremonini, M.A., Forsen, S., Luchinat, C., and Malmendal, A. 1997. Solution structure of the paramagnetic complex of the N-terminal domain of calmodulin with two Ce3+ ions by 1H NMR. Biochemistry 36 11605–11618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini, I. and Luchinat, C. 1998. NMR of paramagnetic molecules in biological systems. Benjamin/Cummings, Menlo Park, CA.

- Bertini, I., Kurtz, Jr., D.M., Eidness, M.K., Liu, G., Luchinat, C., Rosato, A., and Scott, R.A. 1998. Solution structure of reduced Clostridium pasteurianum rubredoxin. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 3 401–410. [Google Scholar]

- Czaja, C., Litwiller, R., Tomlinson, A.J., Naylor, S., Tavares, P., LeGall, J., Moura, J.J., Moura, I., and Rusnak, F. 1995. Expression of Desulfovibrio gigas desulforedoxin in Escherichia coli. Purification and characterization of mixed metal isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 270 20273–20277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauter, Z., Sieker, L.C., and Wilson, K.S. 1992. Refinement of rubredoxin from Desulfovibrio vulgaris at 1.0 Å with and without restraints. Acta Crystallogr. B 48 42–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day, M.W., Hsu, B.T., Joshua-Tor, L., Park, J.B., Zhou, Z.H., Adams, M.W., and Rees, D.C. 1992. X-ray crystal structures of the oxidized and reduced forms of the rubredoxin from the marine hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. Protein Sci. 1 1494–1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio, F., Grzesiek, S., Vuister, G.W., Zhu, G., Pfeifer, J., and Bax, A. 1995. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, S.D. and La Mar, G.N. 1990. NMR determination of the orientation of the magnetic susceptibility tensor in cyanometmyoglobin: A new probe of steric tilt of bound ligand. Biochemistry 29 1556–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey, M., Sieker, L., Payan, F., Haser, R., Bruschi, M., Pepe, G., and LeGall, J. 1987. Rubredoxin from Desulfovibrio gigas. A molecular model of the oxidized form at 1.4 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 197 525–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, B.J., Tavares, P., Romao, M.J., Czaja, C., Rusnak, F., Le Gall, J., Moura, I., and Moura, J.J. 1996. The solution structure of desulforedoxin, a simple iron–sulfur protein. An NMR study of the zinc derivative. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1 341–354. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, B.J., Rusnak, F., Moura, I., Domke, T., and Moura, J.J. 1998. NMR determination of the global structure of the 113Cd derivative of desulforedoxin: Investigation of the hydrogen bonding pattern at the metal center. Protein Sci. 7 928–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiles, R.D., Sarma, S., DiGate, R.J., Banville, D., Basus, V.J., Kuntz, I.D., and Waskell, L. 1996. Pseudocontact shifts used in the restraint of the solution structures of electron transfer complexes. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3 333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay, L.E., Keifer, P., and Saarinen, T. 1992. Pure absorption gradient enhanced heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy with improved sensitivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114 10663–10665. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, L.E., Xu, G.Y., and Yamazaki, T. 1994. Enhanced-sensitivity triple-resonance spectroscopy with minimal H2O saturation. J. Magn. Reson. Ser. A 109 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Marion, D. and Wüthrich, K. 1983. Application of phase sensitive two-dimansional correlated spectroscopy (COSY) for measurements of 1H-1H spin-spin coupling constants in proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 113 967–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markley, J.L., Bax, A., Arata, Y., Hilbers, C.W., Kaptein, R., Sykes, B.D., Wright, P.E., and Wüthrich, K. 1998. Recommendations for the presentation of NMR structures of proteins and nucleic acids. Pure Appl. Chem. 70 117–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura, I., Bruschi, M., Le Gall, J., Moura, J.J., and Xavier, A.V. 1977. Isolation and characterization of desulforedoxin, a new type of non-heme iron protein from Desulfovibrio gigas. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 75 1037–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura, J.J., Goodfellow, B.J., Romao, M.J., Rusnak, F., and Moura, I. 1996. Analysis, design and engineering of simple iron–sulfur proteins: Tales from rubredoxin and desulforedoxin. Comments Inorg. Chem. 19 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ottiger, M. and Bax, A. 1998. Determination of relative N-HN, N-C`, C-C`, and C-H effective bond lengths in a protein by NMR in a dilute liquid crystalline phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 12334–12341. [Google Scholar]

- Piotto, M., Saudek, V., and Sklenar, V. 1992. Gradient-tailored excitation for single-quantum NMR spectroscopy of aqueous solutions. J. Biomol. NMR 2 661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prantner, A.M., Volkman, B.F., Wilkens, S.J., Xia, B., and Markley, J.L. 1997. Assignment of 1H, 13C, and 15N signals of reduced Clostridium pasteurianum rubredoxin: Oxidation state-dependent changes in chemical shifts and relaxation rates. J. Biomol. NMR 10 411–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusnak F., Ascenso C., Moura I., and Moura J.J.G. 2002. Superoxide reductase activities of neelaredoxin and desulfoferrodoxin metalloproteins. Methods Enzymol. 349 243–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieker, L.C., Stenkamp, R.E., and LeGall, J. 1994. Rubredoxin in crystalline state. Methods Enzymol. 243 203–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talluri, S. and Wagner, G. 1996. An optimized 3D NOESY-HSQC. J. Magn. Reson. B 112 200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjandra, N. and Bax, A. 1997. Measurement of dipolar contributions to 1JCH splittings from magnetic-field dependence of J modulation in two-dimensional NMR spectra. J. Magn. Reson. 124 512–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjandra, N., Grzesiek, S., and Bax, A. 1996. Magnetic field dependence of nitrogen-proton J splittings in N-15-enriched human ubiquitin resulting from relaxation interference and residual dipolar coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118 6264–6272. [Google Scholar]

- Volkman, B.F., Prantner, A.M., Wilkens, S.J., Xia, B., and Markley, J.L. 1997. Assignment of 1H, 13C, and 15N signals of oxidized Clostridium pasteurianum rubredoxin. J. Biomol. NMR 10 409–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkman, B.F., Wilkens, S.J., Lee, A.L., Xia, B., Westler, W.M., Beger, R.D., and Markley, J.L. 1999. Redox-dependent magnetic alignment of Clostridium pasteurianum rubredoxin: Measurement of magnetic susceptibility anisotropy and prediction of pseudocontact shift contributions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 4677–4683. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., Eberstadt, M., Olejniczak, E.T., Meadows, R.P., and Fesik, S.W. 1998. A liquid crystalline medium for measuring residual dipolar couplings over a wide range of temperatures. J. Biomol. NMR 12 443–446. [Google Scholar]

- Watenpaugh, K.D., Sieker, L.C., and Jensen, L.H. 1980. Crystallographic refinement of rubredoxin at 1.2 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 138 615–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkens, S.J., Xia, B., Volkman, B.F., Weinhold, F., Markley, J.L., and Westler, W.M. 1998a. Inadequacies of the point-dipole approximation for describing electron-nuclear interactions in paramagnetic proteins: Hybrid density functional calculations and the analysis of NMR relaxation of high-spin Fe(III) rubredoxin. J. Phys. Chem. B. 102 8300–8305. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkens, S.J., Xia, B., Weinhold, F., Markley, J.L., and Westler, W.M. 1998b. NMR Investigations of Clostridium pasteurianum rubredoxin. Origin of hyperfine 1-H, 2-H, 13-C, and 15-N NMR chemical shifts in iron–sulfur proteins: Comparison of hybrid density functional calculations with experimental data. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 4806–4814. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, B., Wilkens, S.J., Westler, W.M., and Markley, J.L. 1998. Amplification of one-bond 1-H/2-H isotope effects on 15-N chemical shifts in Clostridium pasteurianum rubredoxin by fermi-contact effects through hydrogen bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 4893–4894. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L., Kennedy, M., Czaja, C., Tavares, P., Moura, J.J., Moura, I., and Rusnak, F. 1997. Conversion of desulforedoxin into a rubredoxin center. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 231 679–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]