Abstract

Proteins containing Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] clusters play important roles in many biological electron transfer reactions. Typically, [2Fe-2S] clusters are not directly involved in the catalytic transformation of substrate, but rather supply electrons to the active site. We report herein X-ray absorption spectroscopic (XAS) data that directly demonstrate an average increase in the iron–histidine bond length of at least 0.1 Å upon reduction of two distantly related Rieske-type clusters in archaeal Rieske ferredoxin from Sulfolobus solfataricus strain P-1 and bacterial anthranilate dioxygenases from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. This localized redox-dependent structural change may fine tune the protein–protein interaction (in the case of ARF) or the interdomain interaction (in AntDO) to facilitate rapid electron transfer between a lower potential Rieske-type cluster and its redox partners, thereby regulating overall oxygenase reactions in the cells.

Keywords: Anthranilate dioxygenase (AntDO), archaeal Rieske ferredoxin (ARF), iron-sulfur cluster, reduction potential, Rieske-type ferredoxin, X-ray absorption fine structure, X-ray absorption spectroscopy

Proteins containing Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] clusters provide critical electron transfer reactions (Mason and Cammack 1992; Trumpower and Gennis 1994; Link 1999; Berry et al. 2000) in biological pathways. Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] clusters differ from the classical plant-type ferredoxin (Fd) [2Fe-2S] clusters in the nature of the amino acid ligands to the cluster. Although plant-type Fd [2Fe-2S] clusters are ligated by four cysteine residues, Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] clusters have a mixed coordination environment involving two histidines to one iron and two cysteines to the other iron. The cluster coordination has been firmly established by recent X-ray crystal structures of the Rieske iron–sulfur protein domains from the bovine mitochondrial bc1 complex (Iwata et al. 1996), the spinach chloroplast b6f complex (Carrell et al. 1997), bacterial naphthalene dioxygenase (NDO) (Kauppi et al. 1998), and bacterial Rieske-type Fd (BphF) (Colbert et al. 2000). The di-histidine-coordinated iron becomes a localized ferrous site upon reduction of the cluster with the di-cysteine-coordinated iron remaining ferric (Fee et al. 1984; Cline et al. 1985; Kuila and Fee 1986; Gurbiel et al. 1996).

Two different types of Rieske clusters have been observed in proteins: one with higher reduction potentials (Em = +150 to +490 mV) in cytochrome bc1/b6f complexes of the aerobic respiratory chain and photosynthesis, and the other with lower reduction potentials (Em = −150 to −50 mV, NHE) in a diverse group of bacterial multicomponent terminal oxygenases and soluble Rieske-type ferredoxins (Kuila and Fee 1986; Link et al. 1992; Mason and Cammack 1992; Riedel et al. 1995; Link et al. 1996; Brugna et al. 1999). The degree to which structural variations in the vicinity of the clusters contribute to the functional properties is still a matter of intense debate, although correlations among reduction potentials, variations of hydrogen-bond networks (Denke et al. 1998; Schröter et al. 1998; Guergova-Kuras et al. 2000), and polypeptide dipoles in the vicinity of the Rieske-type clusters (Colbert et al. 2000) have been proposed. The midpoint reduction potentials of the clusters in archaeal Rieske-type ferredoxin (ARF) from Sulfolobus solfataricus strain P-1, a small, soluble, thermophilic protein of unknown function, and bacterial Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 anthranilate dioxygenase (AntDO), which catalyzes the conversion of anthranilate to catechol in the β-ketoadipate pathway for biodegradation of aromatic compounds (Eby et al. 2001), are examples of Rieske-type clusters that belong to the lower reduction potential class. The midpoint redox potentials of the clusters in ARF and AntDO are −155 mV (T. Iwasaki, A. Kounosu, N. Kurosawa, T. Imai, A. Urishiyama, unpubl.) and approximately −125 mV (estimated from redox potential of 2-halobenzoate 1,2-dioxygenase) (Correll et al. 1992; Riedel et al. 1995; Coulter et al. 1999; Eby et al. 2001), respectively. We report herein X-ray absorption spectroscopic (XAS) data that directly demonstrate an increase in the iron–histidine bond length of at least 0.1 Å upon reduction of the Rieske-type cluster, suggesting a functional role in biocatalysis for these clusters.

Results

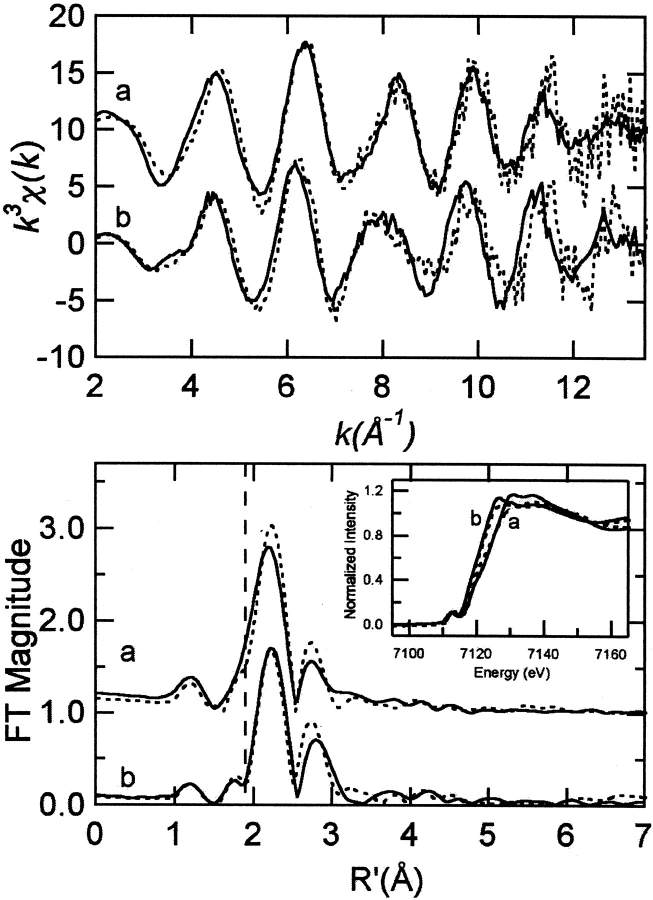

Fe XAS for both ARF and AntDO show the expected shift in edge position to lower energy upon reduction of the Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] cluster (Fig. 1 ▶, inset). For Rieske-type ferredoxins, the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) is a measure of the average coordination environment of both iron atoms in the cluster. One iron has a coordination sphere including four sulfur atoms and a distant iron, while the other iron has a sphere that includes two sulfur atoms, two nitrogen atoms, and a distant iron. Thus, the average coordination environment is three sulfur atoms, one nitrogen atom, and a distant iron. The EXAFS data (Table 1) for oxidized ARF (AntDO) are best fit assuming three sulfur atom scatterers at 2.20 Å (2.21 Å), one nitrogen atom at 1.95 Å (1.97 Å), and one iron scatterer at 2.67 Å (2.64 Å). The EXAFS data for reduced ARF (AntDO) are best fit assuming three sulfur atom scatterers at 2.24 Å (2.21 Å), one nitrogen atom at 2.15 Å (2.15 Å), and an iron scatterer at 2.69 Å (2.62 Å). The outer-shell atoms of the histidine–imidazole ligand can also be incorporated into all fits, with reasonable Debye-Waller factor values. However, inclusion of these atoms contributes minimally to the fit and results in no significant improvement of the goodness-of-fit value.

Fig. 1.

EXAFS (top) and sulfur phase-corrected Fourier transforms (bottom, over k = 2–13.5 Å−1) of oxidized (a) and reduced (b) ARF (solid) and AntDO (dashed). The vertical line in the Fourier transform is positioned to illustrate the shift to longer distance of the shoulder of the first shell peak, which represents the Fe-Nimid scattering shell. X-ray absorption Fe K edge spectra (bottom, inset) for oxidized (a) and reduced (b) ARF (solid) and AntDO (dashed).

Table 1.

Curve fitting results for Fe EXAFSa

| Sample filename (k range) Δ κ3 χ | Fit | Shell | Ras (Å) | σas2 (Å) | fb |

| ARF (oxid) | 1 | Fe-S3 | 2.20 | 0.0050 | 0.064 |

| FFO0A (2–13.5 Å−1) | Fe-Fe | 2.67 | 0.0060 | ||

| Δ k3 χ = 13.39 | Fe-N | 1.95 | 0.0010 | ||

| 2 | Fe-S3 | 2.18 | 0.0055 | 0.082 | |

| Fe-Fe | 2.67 | 0.0058 | |||

| ARF (red) | 3 | Fe-S3 | 2.24 | 0.0052 | 0.059 |

| FFR0A (2–13.5 Å−1) | Fe-Fe | 2.69 | 0.0049 | ||

| Δ k3 χ = 12.58 | Fe-N | 2.15 | 0.0067 | ||

| 4 | Fe-S3 | 2.24 | 0.0049 | 0.063 | |

| Fe-Fe | 2.68 | 0.0050 | |||

| AntDO (oxid) | 5 | Fe-S3 | 2.21 | 0.0044 | 0.083 |

| AFORA (2–13.5 Å−1) | Fe-N | 1.97 | 0.0027 | ||

| Δ k3 χ = 15.07 | Fe-Fe | 2.64 | 0.0049 | ||

| 6 | Fe-S3 | 2.20 | 0.0045 | ||

| Fe-Fe | 2.64 | 0.0051 | |||

| AntDO (red) | 7 | Fe-S3 | 2.21 | 0.0028 | 0.070 |

| AFRRA (2–13.5 Å−1) | Fe-N | 2.15 | 0.0028 | ||

| Δ k3 χ = 14.60 | Fe-Fe | 2.62 | 0.0039 | ||

| 8 | Fe-S3 | 2.22 | 0.0052 | 0.072 | |

| Fe-Fe | 2.62 | 0.0038 |

a Shell is the type and number of scatterers per metal. Ras is the metal-scatterer distance. σas2 is a mean square deviation in Ras.

bf′ is defined as:

|

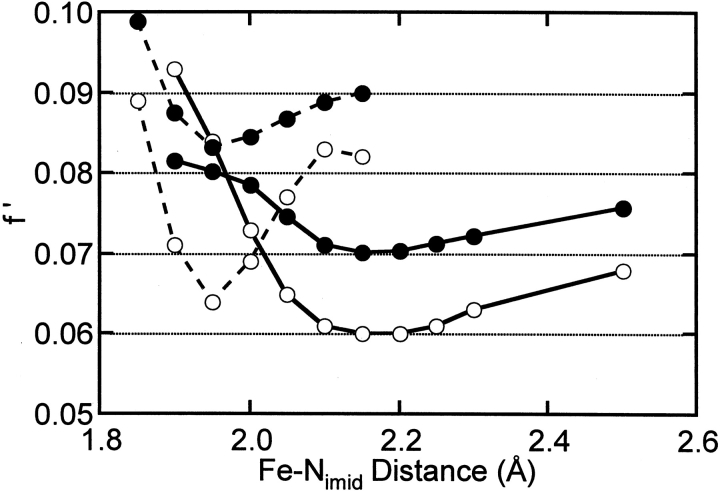

The distance of the Fe-Nimid shell in oxidized ARF and AntDO EXAFS is better defined than that of the Fe-Nimid shell in the reduced proteins. The shorter Fe-Nimid distances in the oxidized clusters are evidenced by the low-R shoulder on the Fe EXAFS FT first-shell peaks (Fig. 1, bottom ▶). The uncertainty in this distance in the reduced forms is a result of the lack of resolution between the Fe-S and Fe-Nimid distances. Nonetheless, the comparison between improvement in goodness-of-fit value and Fe-Nimid distance clearly demonstrates a lengthening of the Fe-Nimid shell in the reduced form and precludes the presence of a short (1.96 Å) Fe-Nimid bond length (Fig. 2 ▶). Curve fitting of the reduced Fe EXAFS data is not significantly worsened by omitting the Fe-Nimid shell (compare Fits 3 and 4 or 7 and 8; Table 1). However, based on ENDOR studies of other lower potential Rieske-type clusters (Gurbiel et al. 1996; Link 1999), it seems more likely that the histidine ligands remain bound to the ferrous iron. The NDO crystal structure of predominantly reduced Rieske-type cluster also shows that both histidine-NΔs are bound to the cluster (Karlsson et al. 2000).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the goodness-of-fit value (f`) with the Fe-Nimid bond distance for oxidized (dashed) and reduced (solid) ARF (open circles) and AntDO (filled circles) in fits where the Fe-Nimid distance was constrained to the specified value and the Fe-Nimid Debye-Waller factor was constrained to be 0.0020 Å2. Lines connect the points for visual comparison.

Discussion

The XAS results indicate that the Fe-S bond distances vary only slightly upon reduction of the cluster, which is in agreement with a previous report (Tsang et al. 1989). The Fe-Nimid bond distance, however, has increased by at least 0.1 Å upon reduction in both ARF and AntDO. Such a significant increase in Fe-Nimid bond distance has not been recorded for any type of Rieske Fe-S cluster (Tsang et al. 1989).

Evidence does exist, however, for redox-dependent, protein-based structural changes associated with biological [2Fe-2S] clusters with complete cysteinyl ligation. For example, NMR analysis of human ferredoxin (Xia et al. 1998), and X-ray crystallographic analysis of Anabaena ferredoxin (Morales et al. 1999) indicate significant structural rearrangement between the oxidized and reduced states. Anabaena ferredoxin undergoes a peptide conformational change upon reduction that leads to a [2Fe-2S] cluster environment very similar to that in Burkholderia cepacia phthalate dioxygenase reductase (PDR) (Morales et al. 1999).

In the Rieske domain of NDO, which is homologous to bacterial and archaeal Rieske-type ferredoxins, one of the histidine ligands to the cluster is connected to the neighboring subunit via a hydrogen bond network (Kauppi et al. 1998), implying a specific protein-mediated electron and/or proton transfer pathway between the Rieske-type cluster and the mononuclear active site. This pathway in NDO has been further explored using single turnover studies with an enzyme that contained a Rieske cluster in the oxidized or reduced states (Wolfe et al. 2001). Surprisingly, the oxidation state of the Rieske cluster was a determining factor, along with the presence of substrate, in O2 activation at the mononuclear site. The mechanism for regulation of activation at the mononuclear site might well be the lengthening of the Fe-Nimid bond that is observed upon reduction of the two distantly related Rieske-type clusters of ARF and AntDO. This structural change is most likely to be an inherent property of the Rieske-type cluster, at least for those with the lower reduction potentials. The localized redox-dependent structural change may fine tune the protein– protein interaction (in the case of ARF) or the interdomain interaction (in AntDO) to facilitate rapid electron transfer, as well as O2 binding, thereby regulating overall oxygenase activity.

The scale of redox-dependent structural changes of the cluster, ca. 0.17 Å for the Fe-Nimid bond, is such that the changes could easily evade detection by crystallographic techniques, which often have a lower precision in metal–ligand bond distances (Kauppi et al. 1998). XAS has been used in only two cases to analyze the iron coordination environment of a Rieske cluster (Powers et al. 1989; Tsang et al. 1989), neither of which quantitatively describes the contribution of the histidine ligands to the iron EXAFS for the cluster.

The XAS results presented here provide the first direct evidence that the coordination sphere of a Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] cluster varies significantly between oxidation states. These structural changes may be limited to Rieske-type clusters that play specific catalytic roles in biology and not applicable to the entire class of iron–sulfur cluster proteins. Nonetheless, this work provides some of the first structural evidence in support of the hypothesis that oxidation state-mediated structural changes of iron–sulfur centers play a critical role in regulating enzymatic catalysis.

Materials and methods

The arf gene coding for hypothetical archaeal Rieske-type ferredoxin (ORF c06009) of the hyperthermoacidophilic archaeon S. solfataricus P-1 (DSM 1616T) was cloned and sequenced (the DDBJ accession number, AB047031), and its gene product overproduced as a hexa-histidine-tagged protein in Escherichia coli strain BL21 CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL strain (Stratagene) and purified to homogeneity. The recombinant protein has been characterized by circular dichroism, electron paramagnetic resonance, resonance Raman, and potentiometric analyses (T. Iwasaki, A. Kounosu, N. Kurosawa, T. Imai, and A. Urushiyama, manuscript in preparation). S. solfataricus ARF contains the consensus motif characteristic for the oxygenase-associated Rieske-type ferredoxins, -Cys-Xaa-His-//-Gly-(Xaa)2–(Val/Ile)-Xaa-Cys-Xaa-(Leu)-His (Mason and Cammack 1992; Link 1999), where the two cysteines and two histidines (Cys-42, Cys-61, His-44, His-64) probably serve as ligands to a Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] cluster. Purified recombinant ARF was concentrated initially by pressure filtration with an Amicon YM-10 membrane, and further by placing the samples under a stream of dry argon gas (Iwasaki et al. 2000). Dithionite reduction was performed anaerobically at room temperature under argon atmosphere. The resultant samples (∼0.6–0.8 mM), containing 30% (v/v) glycerol, were frozen in a 24 × 1 × 2 mm polycarbonate cuvet with a Mylar-tape front window for XAS studies.

Recombinant AntDO was overexpressed and purified to homogeneity (Eby et al. 2001). The removal of mononuclear iron from the catalytic site (to avoid complication of Fe K-edge XAS analysis) and the preparation of oxidized and reduced Rieske cluster in AntDO were performed as described previously (Coulter et al. 1999). Briefly, Fe(II) was removed from the catalytic site by dialysis against three changes of 2 L of buffer containing 25 mM MOPS (pH 7.3), 5 mM EDTA over 12 h. To remove exogenous Fe and EDTA, the mononuclear Fe-removed protein (apoAntDO) was dialyzed against two changes of 2 L buffer containing 25 mM MOPS (pH 7.3) over 12 h. ApoAntDO was then passed through a HiTrap 5-mL desalting column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with 25 mM MOPS, (pH 7.3) for complete removal of Fe and EDTA. Loss of Fe(II) from the catalytic site was confirmed by monitoring absorbance at 340 nm when apoAntDO was added to a spectrophotometric NADH oxidation assay (0.5 mM anthranilate, 0.1 mM NADH, 0.5 μM apoAntDO, 0.18 μM AntC in 50 mM MES, pH 6.3 and 100 mM KCl; Eby et al. 2001). The absence of detectable catalysis of aromatic substrate was also confirmed in the same assay when anthranilate was monitored by HPLC (Eby et al. 2001). The apoAntDO sample was then split into two aliquots. A final concentration of 10% (vol/vol) glycerol was added to one aliquot, placed into XAS cuvets, and frozen in liquid nitrogen (oxidized apoAntDO). The other aliquot was made anaerobic by first mixing the sample with N2 gas for 5 min, then reduced by careful titration with an anaerobic sodium dithionite solution (20 mg/mL) in an anaerobic chamber until the red-brown color faded from apoAntDO, a characteristic of reduced Rieske [2Fe-2S]. Glycerol at 10% (vol/vol) final concentration was added to reduced apoAntDO, placed into XAS cuvets, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The appearance of reduced Rieske centers was confirmed by presence of the characteristic UV/VIS and EPR spectra (Eby et al. 2001).

XAS data were collected at 10 K at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, beamline 7-3, with the SPEAR storage ring operating at 3.0 GeV. A monochromator containing a Si[220] crystal and a 13-element Ge solid-state X-ray fluorescence detector (provided by the NIH Biotechnology Research Resource) were employed for data collection. No photoreduction was observed in comparisons of the first and last spectra collected for a given sample. The first inflection of the edge of an Fe foil (assumed to be 7111.2 eV) was used for energy calibration. All other data collection parameters were as described previously (Cosper et al. 1999). EXAFS analysis was performed with the EXAFSPAK software (www-ssrl.slac.stanford.edu/exafspak.html) according to standard procedures (Scott 1985).

Electronic supplemental material

Plots of curve-fitting results for the EXAFS of oxidized and reduced Sulfolobus solfataricus and Acinetobacter sp. Rieske-type proteins is available as supplementary information.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. S.A. Dikanov (University of Illinois) and Dr. T. Nishino (Nippon Medical School) for discussion, and Dr. T. Oshima (Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Science) for allowing us access to the large-scale fermenter facility. The XAS data were collected at SSRL, which is operated by the Department of Energy, Division of Chemical Sciences. The SSRL Biotechnology program is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Biomedical Resource Technology Program, Division of Research Resources. This investigation was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (no. 11169237 to T.I.) and from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (BSAR-507 to T.I.), and by the National Institutes of Health (GM 42025 to R.A.S. and GM59818 to E.L.N and D.M.K.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.0222402.

References

- Berry, E.A., Guergova-Kuras, M., Huang, L.-S., and Crofts, A.R. 2000. Structure and function of cytochrome bc complexes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69 1005–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugna, M., Nitschke, W., Asso, M., Guigliarelli, B., Lemesle-Meunier, D., and Schmidt, C. 1999. Redox components of cytochrome bc-type enzymes in acidophilic prokaryotes. II. The Rieske protein of phylogenetically distant acidophilic organisms. J. Biol. Chem. 274 16766–16772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrell, C.J., Zhang, H., Cramer, W.A., and Smith, J.L. 1997. Biological identity and diversity in photosynthesis and respiration: Structure of the lumen-side domain of the chloroplast Rieske protein. Structure 5 1613–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline, J.F., Hoffman, B.M., Mims, W.B., LaHaie, E., Ballou, D.P., and Fee, J.A. 1985. Evidence for N coordination to Fe in the [2Fe-2S] clusters of Thermus Rieske protein and phthalate dioxygenase from Pseudomonas. J. Biol. Chem. 260 3251–3254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert, C.L., Couture, M.M.-J., Eltis, L.D., and Bolin, J. 2000. A cluster exposed: Structure of the Rieske ferredoxin from biphenyl dioxygenase and the redox properties of Rieske Fe-S proteins. Structure 8 1267–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll, C.C., Batie, C.J., Ballou, D.P., and Ludwig, M.L. 1992. Phthalate dioxygenase reductase: A modular structure for electron transfer from pyridine nucleotides to [2Fe-2S]. Science 258 1604–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosper, N.J., Stålhandske, C.M.V., Saari, R.E., Hausinger, R.P., and Scott, R.A. 1999. X-ray absorption spectroscopic analysis of Fe(II) and Cu(II) forms of a herbicide-degrading α-ketoglutarate dioxygenase. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 4 122–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter, E.D., Moon, N., Batie, C.J., Dunham, W.R., and Ballou, D.P. 1999. Electron paramagnetic resonance measurements of the ferrous mononuclear site of phthalate dioxygenase substituted with alternate divalent metal ions: Direct evidence for ligation of two histidines in the copper(II)-reconstituted protein. Biochemistry 38 11062–11072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denke, E., Merbitz-Zahradnik, T., Hatzfeld, O.M., Snyder, C.H., Link, T.A., and Trumpower, B.L. 1998. Alteration of the midpoint potential and catalytic activity of the Rieske iron–sulfur protein by changes of amino acids forming hydrogen bonds to the iron–sulfur cluster. J. Biol. Chem. 273 9085–9093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eby, D.M., Beharry, Z.M., Coulter, E.D., Kurtz, D.M., and Neidle, E.L. 2001. Characterization and evolution of anthranilate 1,2-dioxygenase from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. J. Bacteriol. 183 109–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fee, J.A., Findling, K.L., Yoshida, T., Hille, R., Tarr, G.E., Hearshen, D.O., Dunham, W.R., Day, E.P., Kent, T.A., and Münck, E. 1984. Purification and characterization of the Rieske iron–sulfur protein from Thermus thermophilus. Evidence for a [2Fe-2S] cluster having non-cysteine ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 259 124–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guergova-Kuras, M., Kuras, R., Ugulava, N., Hadad, I., and Crofts, A.R. 2000. Specific mutagenesis of the Rieske iron–sulfur protein in Rhodobacter sphaeroides shows that both the thermodynamic gradient and the pK of the oxidized form determine the rate of quinol oxidation by the bc(1) complex. Biochemistry 39 7436–7444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurbiel, R.J., Doan, P.E., Gassner, G.T., Macke, T.J., Case, D.A., Ohnishi, T., Fee, J.A., Ballou, D.P., and Hoffman, B.M. 1996. Active site structure of Rieske-type proteins: Electron nuclear double resonance studies of isotopically labeled phthalate dioxygenase from Pseudomonas cepacia and Rieske protein from Rhodobacter capsulatus and molecular modeling studies of a Rieske center. Biochemistry 35 7834–7845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki, T., Watanabe, E., Ohmori, D., Imai, T., Urushiyama, A., Akiyama, M., Hayashi-Iwasaki, Y., Cosper, N.J., and Scott, R.A. 2000. Spectroscopic investigation of selective cluster conversion of archaeal zinc-containing ferredoxin from Sulfolobus sp. strain 7. J. Biol. Chem. 275 25391–25401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata, S., Saynovits, M., Link, T.A., and Michel, H. 1996. Structure of a water soluble fragment of the "Rieske" iron sulfur protein of the bovine heart mitochondrial cytochrome bc(1) complex determined by MAD phasing at 1.5 angstrom resolution. Structure 4 567–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, A., Parales, J.V., Parales, R.E., Gibson, D.T., Eklund, H., and Ramaswamy, S. 2000. The reduction of the Rieske iron–sulfur cluster in naphthalene dioxygenase by X-rays. J. Inorg. Biochem. 78 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppi, B., Lee, K., Carredano, E., Parales, R.E., Gibson, D.T., Eklund, H., and Ramaswamy, S. 1998. Structure of an aromatic-ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase-naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase. Structure 6 571–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuila, D. and Fee, J.A. 1986. Evidence for a redox-linked ionizable group associated with the [2Fe-2S] cluster of Thermus Rieske protein. J. Biol. Chem. 261 2768–2771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link, T.A. 1999. Iron sulfur proteins. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 47 83–157. [Google Scholar]

- Link, T.A., Hagen, W.R., Pierik, A.J., Assmann, C., and Jagow, G.v. 1992. Determination of the redox properties of the Rieske [2Fe-2S] cluster of bovine heart bc1 complex by direct electrochemistry of a water-soluble fragment. Eur. J. Biochem. 208 685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link, T.A., Hatzfeld, O.M., Unalkat, P., Shergill, J.K., Cammack, R., and Mason, J.R. 1996. Comparison of the "Rieske"[2Fe-2S] center in the bc1 complex and in bacterial dioxygenases by circular dichroism spectroscopy and cyclic voltammetry. Biochemistry 35 7546–7552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, J.R. and Cammack, R. 1992. The electron-transport proteins of hydroxylating bacterial dioxygenases. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46 277–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales, R., Charon, M.-H., Hudry-Clergeon, G., Peillot, Y., Norager, S., Medina, M., and Frey, M. 1999. Refined X-ray structures of the oxidized, at 1.3 Å, and reduced, at 1.17 Å, [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin from the cyanobacterium Anabaena PCC7119 show redox-linked conformational changes. Biochemistry 38 15764–15773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers, L., Schagger, H., Vonjagow, G., Smith, J., Chance, B., and Ohnishi, T. 1989. EXAFS studies of the isolated bovine heart Rieske [2Fe-2S]1+(1+,2+) cluster. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 975 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel, A., Fetzner, S., Rampp, M., Lingens, F., Liebl, U., Zimmermann, J.-L., and Nitschke, W. 1995. EPR, electron spin echo envelope modulation, and electron nuclear double resonance studies of the 2Fe2S centers of the 2-halobenzoate 1,2-dioxygenase from Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia 2CBS. J. Biol. Chem. 270 30869–30873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröter, T., Hatzfeld, O.M., Gemeinhardt, S., Korn, M., Friedrich, T., Ludwig, B., and Link, T.A. 1998. Mutational analysis of residues forming hydrogen bonds in the Rieske [2Fe-2S] cluster of the cytochrome bc1 complex in Paracoccus denitrificans. Eur. J. Biochem. 255 100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, R.A. 1985. Measurement of metal-ligand distances by EXAFS. Methods Enzymol. 117 414–459. [Google Scholar]

- Trumpower, B.L. and Gennis, R.B. 1994. Energy transduction by cytochrome complexes in mitochondrial and bacterial respiration: The enzymology of coupling electron transfer reactions to transmembrane proton translocation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63 675–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, H.-T., Batie, C.J., Ballou, D.P., and Penner-Hahn, J.E. 1989. X-ray absorption spectroscopy of the [2Fe-2S] Rieske cluster in Pseudomonas cepacia phthalate dioxygenase. Determination of core dimensions and iron ligation. Biochemistry 28 7233–7240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, M.D., Parales, J.V., Gibson, D.T., and Lipscomb, J.D. 2001. Single turnover chemistry and regulation of O2 activation by the oxygenase component of naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 276 1945–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, B., Volkman, B.F., and Markley, J.L. 1998. Evidence for oxidation-state-dependent conformational changes in human ferredoxin from multinuclear, multidimensional NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry 37 3965–3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]