Abstract

Experimental infection of mice with Plasmodium berghei ANKA (PbA) provides a powerful model to define genetic determinants that regulate the development of cerebral malaria (CM). Based on the hypothesis that excessive activation of the complement system may confer susceptibility to CM, we investigated the role of C5/C5a in the development of CM. We show a spectrum of susceptibility to PbA in a panel of inbred mice; all CM-susceptible mice examined were found to be C5 sufficient, whereas all C5-deficient strains were resistant to CM. Transfer of the C5-defective allele from an A/J (CM resistant) onto a C57BL/6 (CM-susceptible) genetic background in a congenic strain conferred increased resistance to CM; conversely, transfer of the C5-sufficient allele from the C57BL/6 onto the A/J background recapitulated the CM-susceptible phenotype. The role of C5 was further explored in B10.D2 mice, which are identical for all loci other than C5. C5-deficient B10.D2 mice were protected from CM, whereas C5-sufficient B10.D2 mice were susceptible. Antibody blockade of C5a or C5a receptor (C5aR) rescued susceptible mice from CM. In vitro studies showed that C5a-potentiated cytokine secretion induced by the malaria product P. falciparum glycosylphosphatidylinositol and C5aR blockade abrogated these amplified responses. These data provide evidence implicating C5/C5a in the pathogenesis of CM.

Despite the development of more potent antimalarial drugs, there has been little progress in identifying interventions that improve the outcome of cerebral malaria (CM) (1, 2). This may be attributable, at least partly, to the observation that severe malaria syndromes such as CM appear to be primarily mediated by host responses to infection rather than by the parasite directly.

Experimental infection of inbred and congenic mice with Plasmodium berghei ANKA (PbA) provides a well-established model to identify host genetic determinants that regulate both protective immunity and infection-associated immunopathology, including the development of CM. Similar to P. falciparum infection in humans, mice susceptible to PbA (e.g., C57BL/6 mice) develop symptoms of severe malaria and CM, including cytokine-associated encephalopathy, acidosis, coagulopathy, shock, and pulmonary edema, culminating in a fatal outcome (3–5). Conversely, A/J mice, although equally susceptible to PbA infection, are more resistant to the associated CM syndrome (6–7).

Excessive or dysregulated inflammatory responses to malaria, including high levels of TNF/lymphotoxin-α or inadequate production of regulatory (antiinflammatory) cytokines such as TGF-β and IL-10, are associated with the development of CM in both human infections and rodent models of disease (4, 8–12). High levels of inflammatory cytokines are associated with endothelial cell activation and increased expression of adhesion molecules that contribute to the sequestration of parasitized erythrocytes and leukocytes in the cerebral vascular bed and the resultant CM syndrome (10, 13–15). Although it is well established that host response contributes to the development of CM, the underlying genetic determinants of susceptibility are poorly characterized (10). A detailed understanding of the host genetic factors that contribute to susceptibility or resistance to CM may facilitate the identification of novel interventions to modulate host response and improve the outcome of CM (2, 15).

The complement system is an essential component of the innate immune response to several infectious agents (16). The complement cascade can be activated by four different pathways, three of which converge at the level of the C3 component, leading to the cleavage of C3 and C5 to their activated forms, C3a and C5a, as well as the formation of the terminal membrane attack complex (17, 18). A recently described pathway results in the generation of C5a in the absence of C3 (19).

A growing body of evidence has implicated excessive activation of the complement system, especially formation of the potent proinflammatory anaphylatoxin C5a in mediating deleterious host responses to bacterial infections and contributing to the development of sepsis, adverse outcomes, and death (16, 18, 20). Blockade of C5a activity or C5aR with antibodies or C5aR antagonists in animal models of sepsis prevents multiorgan injury and improves survival (19, 21–24). Generation of C5a is normally tightly regulated, and under controlled conditions, local production of C5a can enhance effector function of macrophages and neutrophils and contribute to an effective innate response to infection. However, detectable systemic C5a suggests a loss of regulation of complement activation. Elevated C5a levels are associated with several deleterious effects on host innate defense, including defective phagocyte and endothelial cell function, robust chemokine and cytokine secretion, and lymphoid apoptosis (16, 18, 20).

Similar to sepsis, CM is believed to be the result, at least partly, of a dysregulated inflammatory response to infection. However, the roles of C5 and C5a in the pathogenesis of CM have not been studied. We hypothesized that excessive generation of C5a in response to infection confers susceptibility to CM and investigated the role of C5a in the development of CM in vivo. Using a panel of inbred and congenic mice, we demonstrate a spectrum of differential susceptibility to CM that is associated with the presence or absence of C5 and the generation of C5a, as well as the engagement of C5aR. These data provide direct evidence indicating that C5a plays a role in the pathogenesis of CM in the PbA model.

RESULTS

Differential susceptibility of inbred mice to PbA-induced experimental CM

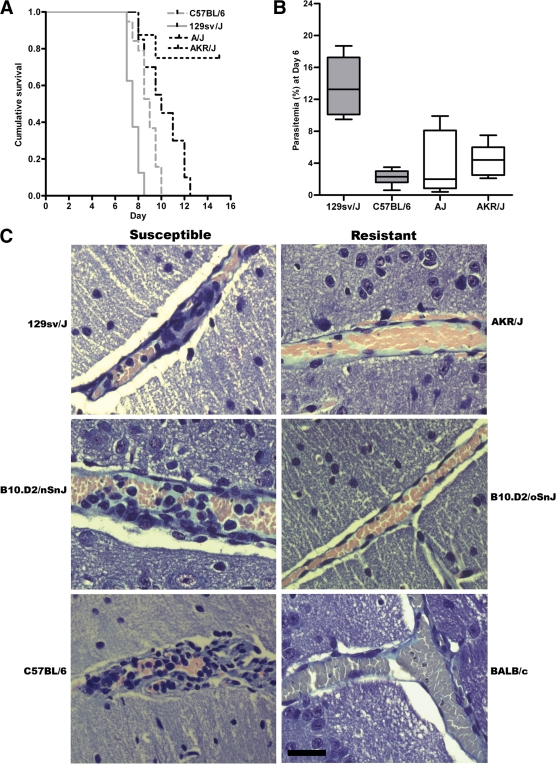

Previous studies have established that inbred strains of mice such as C57BL/6 are susceptible to PbA infection and develop symptoms of experimental CM and rapidly succumb to infection. In contrast, other inbred mice, such as DBA/2 or A/J mice, are more resistant to CM and display enhanced survival during the acute phase of infection (6, 7, 25–27). To more completely define the phenotypic expression of differential susceptibility in this experimental model, we simultaneously challenged a panel of inbred mice under carefully controlled experimental conditions with a uniform inoculum of PbA and examined parasitemia, the development of experimental CM, and survival over a course of infection (Table I and Fig. 1 A). We observed differences in survival between A/J and C57BL/6 mice (A/J vs. C57BL/6: P = 0.002 and χ2 = 9.879 using a log-rank test for survival; Fig. 1 A). However, in this analysis a broader spectrum of susceptibility was observed than previously reported (6, 7, 25–27). This phenotypic expression ranged from highly susceptible to highly resistant to experimental CM (Table I and Fig. 1 A). Compared with CM-susceptible C57BL/6 mice, highly susceptible mice such as 129sv/J and 129P3/J mice had an earlier onset of neurological symptoms and succumbed significantly sooner to CM (as confirmed by histopathology; Fig. 1 C) during the course of infection (P = 0.001 and χ2 = 11.317 using a log-rank test). In contrast, AKR/J mice were highly resistant, with significantly improved survival compared with other strains (P = 0.00001 and χ2 = 13.568 using a log-rank test; Fig. 1 C). To examine whether parasite burden contributed to these different phenotypes, we examined the parasitemia in these inbred lines. No significant difference in parasitemia was observed between susceptible, resistant, and highly resistant mice throughout the course of infection (Fig. 1 B and Fig. S1, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20072248/DC1). In contrast, highly susceptible mice, such as 129sv/J mice, developed significantly higher parasite burdens earlier in the course of infection, as indicated by day 6 peripheral parasitemias (P = 0.006 using a Kruskal-Wallis test; Fig. 1 B).

Table I.

PbA-induced experimental CM is associated with the presence of the C5 gene

| Strain | C5 status | CM phenotypea |

|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6 | Sufficient | Susceptible |

| C57BL/10 | Sufficient | Susceptible |

| CBA/Ca | Sufficient | Susceptible |

| DBA/1 | Sufficient | Susceptible |

| SJL/J | Sufficient | Susceptible |

| 129sv/J | Sufficient | Highly susceptible |

| 129P3/J | Sufficient | Highly susceptible |

| C3H/HeN | Sufficient | Susceptible |

| B10.D2/nSnJ | Sufficient | Susceptible |

| B10.D2/oSnJ | Deficient | Resistant |

| A/J | Deficient | Resistant |

| DBA/2 | Deficient | Resistant |

| AKR/J | Deficient | Highly resistant |

| BALB/c | Sufficient | Highly resistant |

CM phenotype describes mice that were judged as developing CM if they displayed neurological symptoms including mono-, hemi-, para-, or tetraplegia, movement disorder, ataxia, hunching, convulsions, and coma, and succumbed to infection by day 12 after inoculation (references 6, 7). Susceptible strains developed neurological symptoms within 6–10 d after inoculation. Highly susceptible mice showed both a significantly higher parasite density and an early onset of neurological symptoms and death than susceptible mouse strains. Resistant strains displayed a significantly delayed onset of neurological symptoms and improved survival compared with susceptible groups. Highly resistant strains did not develop neurological symptoms and displayed enhanced survival compared with resistant strains. Strains analyzed in this study are bolded. Other strains (italicized) were derived as previously described (references 26–28).

Figure 1.

Differential susceptibility to PbA-induced experimental CM. The phenotypes of inbred mice strains infected with PbA range from highly susceptible (early onset of cerebral symptoms and high parasitemia) to highly resistant (very little mortality caused by CM). (A) 129sv/J mice were highly susceptible and died significantly earlier than C57BL/6 mice (C57BL/6 vs. 129sv/J: P = 0.001 and χ2 = 9.879 using a Mantel-Cox log-rank test). A/J mice survived significantly longer than C57BL/6 mice (A/J vs. C57BL/6: P = 0.001 and χ2 = 9.879 using a Mantel-Cox log-rank test). AKR/J mice were highly resistant and had significantly improved survival rates compared with all other strains (A/J vs. AKR/J: P = 0.00001 and χ2 = 13.568 using a Mantel-Cox log-rank test). The figure is representative of two independent experiments (n = 10 mice/group/experiment). 100% of 129sv/J and C57BL/6 mice developed CM (as described in Materials and methods), compared with 30% of A/J and 0% of AKR/J mice. (B) 129sv/J mice had significantly higher mean parasitemia than other CM-susceptible or -resistant mice on day 6 after infection (P = 0.006 using a Kruskal-Wallis test). Representative data from one of two independent experiments (n = 5 mice/group/experiment) are shown. Data are presented as means ± SD. (C) Histopathological examination of brains from susceptible (129sv/J, B10.D2/nSnJ, and C57BL/6) and resistant (AKR/J, B10.D2/oSnJ, and BALB/c) mice, isolated on day 6 after inoculation and formalin fixed. 5-μM sections were prepared and stained with Giemsa. CM-susceptible mice displayed characteristic histological evidence of CM, including the accumulation of mononuclear cells and parasitized erythrocytes in the microvasculature. Bar, 50 μM.

C5 sufficiency is associated with susceptibility to CM

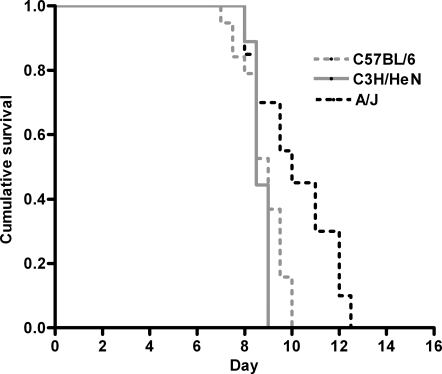

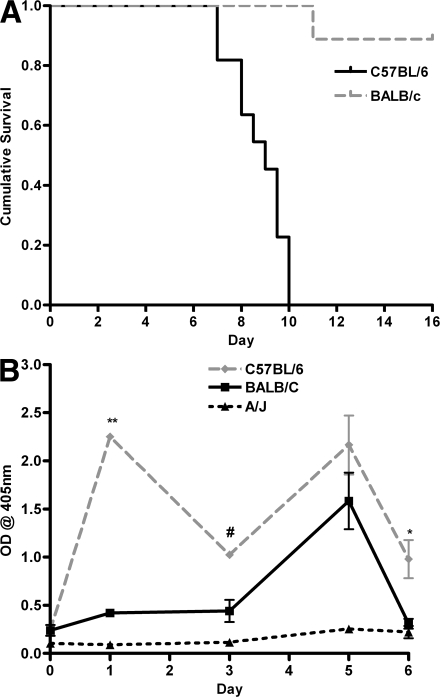

To test the hypothesis that excessive C5a generation may confer susceptibility to CM, we determined the C5 status in the panel of susceptible and resistant mice we had phenotyped, as well as those reported in the literature (Table I) (26–28). C57BL/6, 129sv/J, and 129P3/J strains were shown to be susceptible to PbA-induced CM, and each of these strains is C5 sufficient (wild-type sequence for C5). A/J, DBA/2J, and AKR/J mice are C5 deficient (i.e., they possess a known frame-shift mutation in the C5 gene and do not express functional C5) and were significantly more resistant to PbA-induced CM. A similar association of CM with C5 sufficiency was established by determining the C5 status of other inbred mouse strains reported in the literature as susceptible or resistant to PbA. In each case, inbred mice reported to be susceptible to CM were found to be C5 sufficient. Conversely, all C5-deficient mice analyzed in this study and those reported in the literature were found to be resistant to CM. However there were two notable exceptions to this association. C3H/HeN mice are reported to be C5 sufficient but resistant to CM (28). We genotyped and phenotyped this strain together with appropriate controls and determined that it contained a wild-type sequence for C5 and was sensitive to PbA-induced CM, with a survival course similar to CM-susceptible C57BL/6 mice (Table I and Fig. 2). BALB/c mice are also reported to be resistant to CM and C5 sufficient (8, 27, 29). Because several different lines of BALB/c mice are in current use and because C5 “sufficiency” in the literature often meant only that the C5 gene did not contain the single A/J frame-shift mutation (as detected by PCR), we phenotyped the line in use in our laboratory and investigated this line for the presence of C5 sufficiency by sequencing the entire C5 gene to exclude any other point mutations, confirming gene transcription using RT-PCR, and by measuring C5a production over the course of PbA infection by ELISA. BALB/c mice were found to be resistant to the development of CM, with significantly higher survival than C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 3 A). Sequence analysis showed that the C5 gene from BALB/c mice contained no mutations in the open reading frame and therefore would have been predicted, by our hypothesis, to be susceptible to PbA-induced CM. To explain this apparent discrepancy, serum C5a levels in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice over the course of an infection were analyzed. CM-susceptible C57BL/6 mice were shown to have significantly higher levels of C5a in the peripheral blood than BALB/c mice during infection, particularly at early time points (Fig. 3 B). These observations were also supported by RT-PCR analysis demonstrating that BALB/c mice have levels of C5 that are significantly lower than susceptible C57BL/6 mice and are similar to C5-null A/J mice (BALB/c vs. C57BL/6 mean [SD] day 1 C5 mRNA copy number = 427.1 [471] vs. 4,132 [961], P = 0.002; BALB/c vs. A/J mean [SD] day 1 C5 mRNA copy number = 427.1 [471] vs. 691.6 [480], P = 0.498). These data indicate that susceptibility to PbA-induced CM is associated with C5 sufficiency and support a role for the generation of C5a early during the course of infection as a putative mediator of CM in susceptible animals.

Figure 2.

The role of C5 in the development of PbA-induced experimental CM in C3H/HeN mice. To determine the phenotype and role of C5 in PbA infection in the C5-sufficient mice strain C3H/HeN, C3H/HeN mice, as well as control strains A/J (CM resistant) and C57BL/6 (CM susceptible), were challenged with PbA. C3H/HeN mice were susceptible to the development of CM (100% developed CM) and displayed similar mortality rates as C57BL/6 (C5-sufficient) mice (C57BL/6 vs. C3H/HeN: P = 0.2237 and χ2 = 1.481 using a log-rank test), but significantly higher rates than A/J (C5-deficient) mice (A/J vs. C3H/HeN: P = 0.0033 and χ2 = 8.656; and C57BL/6 vs. A/J: P = 0.0017 and χ2 = 9.879 using a log-rank test). The data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 10 mice/group/experiment).

Figure 3.

Survival and C5a levels in BALB/c, C57BL/6, and A/J mice. Sequence analysis showed that the BALB/c mice used in these studies were C5 sufficient and therefore, by our hypothesis, should be susceptible to PbA-induced CM. (A) However, BALB/c mice are highly resistant to CM despite C5 sufficiency (P < 0.0001 and χ2 = 16.531 using a log-rank test). The figure is representative of two independent experiments (n = 10 mice/group/experiment). 100% of C57BL/6 mice developed CM compared with 0% BALB/c mice. (B) Serum C5a levels of C57BL/6, BALB/c, and A/J mice are represented by mean OD at 405 nm (error bars show SD). C57BL/6 mice had higher circulating C5a levels, particularly on days 1 and 5 compared with A/J (C5-deficient) mice, whereas BALB/c mice only show a C5a peak at day 5 and not early in the course of PbA infection (**, P < 0.0001; *, P < 0.05; and #, P < 0.01 using a Mann-Whitney U test). The graph represents pooled data from two independent experiments (n = 5 mice/group/experiment).

Congenic mice confirm a role for C5 in susceptibility to CM

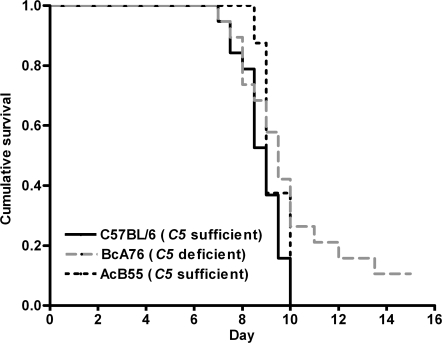

The phenotypic differences to PbA infection between the inbred mouse lines observed in Table I could be either the direct result of C5 sufficiency/deficiency or secondary to other genetic factors acting alone or in combination with C5. Therefore, we further explored the hypothesis that C5a contributes to the pathogenesis of CM by examining the phenotype in recombinant congenic mice and in closely related mouse lines that differ in the presence or absence of C5. Recombinant congenic mice were derived from systematic inbreeding of a double backcross between C5-deficient A/J mice and CM-susceptible, C5-sufficient C57BL/6 mice (30). In this system, each congenic strain contains a fixed set of congenic segments (12.5% of DNA from the donor parent) placed on the genetic background of the recipient parent (87.5% of DNA). Thus, AcB55 recombinant congenic mice contain 12.5% of C57BL/6 genetic material, including a functional C5 gene, on a predominantly A/J genetic background (30); conversely, BcA76 recombinant congenic mice are composed of 12.5% A/J genetic material (including the mutant C5 gene) on a C57BL/6 background. Experimental challenge of these recombinant congenic mice with PbA showed that transfer of the C5-sufficient allele onto an A/J background, as in AcB55 mice, accelerated the development of CM and fatal outcomes compared with the parental A/J (C5-deficient) mice (A/J vs. AcB55: P < 0.05 and χ2 = 4 using a log-rank test). In contrast, BcA76 mice that carry the A/J C5 deficiency allele had reduced incidence of CM and improved survival compared with the parental C57BL/6 mice (C57BL/6 vs. BcA76: P < 0.05 and χ2 = 4.038 using a log-rank test; Fig. 4). We found no difference in parasite burden between congenic AcB55 and BcA76 mice (unpublished data).

Figure 4.

Congenic mice confirm a role for C5 in susceptibility to CM. To further explore the hypothesis that C5a contributes to the pathogenesis of CM, we examined the phenotype in recombinant congenic mice derived from systematic inbreeding of A/J and C57BL/6 mice that differ in their C5 status. Transfer of the C5-sufficient allele onto an A/J background in AcB55 mice accelerated the development of CM and fatal outcomes, whereas BcA76 mice that carry the A/J C5 deficiency allele had reduced incidence of CM and improved survival compared with parental C57BL/6 mice. The data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 10 mice/group/experiment). C5-deficient congenic mice survive significantly longer than C5-sufficient congenic mice (P < 0.05 and χ2 = 4.038 using a log-rank test).

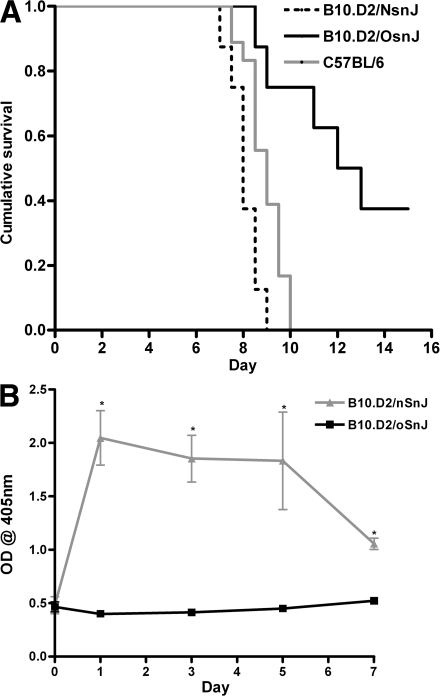

In addition to the recombinant congenic mice, we also examined PbA-induced CM susceptibility in congenic B10.D2/nSnJ and B10.D2/oSnJ mice, which are genetically identical strains except that the B10.D2/nSnJ strain is C5 sufficient, whereas B10.D2/oSnJ mice contain the mutant allele of the C5 gene (with both on a C57BL/10 background). B10.D2/nSnJ mice were found to be susceptible to PbA-induced CM and rapidly succumbed to infection, whereas B10.D2/oSnJ mice displayed significantly improved survival (P < 0.0001 and χ2 = 12.274 using a log-rank test; Fig. 5 A). C5a levels were examined over the course of infection, and B10.D2/nSnJ mice displayed significantly higher levels of circulating C5a as early as day 1 after infection (Fig. 5 B). Together with the observations in C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice, these data further support the contention that an early and sustained induction of C5a confers susceptibility to CM.

Figure 5.

Role of C5 in pathogenesis of CM in closely related B10.D2 mouse strains. To examine whether the survival difference was solely attributable to C5, the congenic B10.D2/nSnJ (C5-sufficient) and B10.D2/oSnJ (C5-deficient) mice were infected with PbA. (A) B10.D2/oSnJ mice are resistant to the development of CM and survive significantly longer than C5-sufficient mice (75 vs. 0%; P < 0.0001 and χ2 = 12.274 using a log-rank test). The figure is representative of two independent experiments (n = 8 mice/group/experiment). 100% of B10.D2/nSnJ mice developed CM compared with 25% of B10.D2/oSnJ mice. (B) Levels of serum C5a, shown as mean OD at 405 nm, were significantly increased in C5-sufficient (B10.D2/nSnJ) mice compared with C5-deficient (B10.D2/oSnJ) mice at days 1, 3, 5, and 7 after infection (*, P < 0.0001 using a Mann-Whitney U test). The data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 5 mice/group/experiment). Data are presented as means ± SD.

Association of C5 status with CM susceptibility in congenic and recombinant congenic mice support the hypothesis that C5 is an important pathological contributor to the host response. Furthermore, with confirmation in genetically identical B10.D2 mice that differ only at the C5 locus, we can remove the roles of other background genetic effects and state more confidently that the C5 gene itself influences overall outcome in experimental CM.

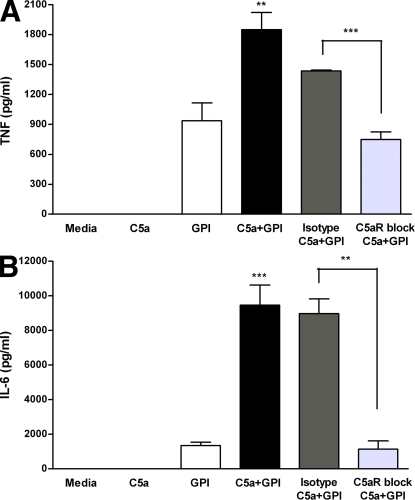

C5a enhances P. falciparum glycosylphosphatidylinositol (PfGPI)–induced proinflammatory responses in vitro

High levels of proinflammatory cytokines are associated with CM in humans and in mouse models (2–6). The P. falciparum product PfGPI has been shown to induce proinflammatory cytokine responses in a Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2–dependent manner (31–33). Because C5a may potentiate inflammatory cytokine induction to other TLR ligands, such as LPS, and because we show that peripheral C5a levels are significantly higher in susceptible mice during malaria infection, we investigated whether the presence of C5a enhances PfGPI-induced TNF and IL-6 production in vitro. The exposure of human PBMCs to HPLC-purified PfGPI in vitro induced the production of TNF and IL-6. The addition of C5a potentiated PfGPI-induced cytokine production, whereas C5aR blockade using anti-C5aR antibody significantly inhibited TNF and IL-6 production (TNF, P = 0.0064; and IL-6, P = 0.0001 using a two-way analysis of variance interaction effect [C5*PfGPI]; Fig. 6, A and B). These data indicate that C5a augments PfGPI-stimulated TNF and IL-6 production and, thus, may play a significant role in the development of the CM syndrome observed in susceptible mice.

Figure 6.

C5a potentiates PfGPI-induced inflammatory cytokines, and amplified responses are inhibited by C5aR blockade. Human PBMCs were treated in three groups as follows: (a) no antibody treatment (control); (b) 5 μg/ml of mouse anti-C5aR blocking antibody; or (c) mouse anti–human IgG2a κ isotype control. Each group was subsequently treated with 50 nM C5a ± 300 ng/ml HPLC-purified PfGPI for 6–24 h, and the supernatants were assayed for the production of TNF and IL-6. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way analysis of variance and is representative of the interaction effect (C5a*PfGPI). A Student's t test was used to assess whether blockade of C5aR inhibited cytokine induction. (A) C5a potentiated PfGPI-induced TNF production at 6 h (**, P = 0.0064), and this effect was inhibited by blocking C5aR (***, P = 0.0008). (B) C5a potentiated PfGPI-induced IL-6 production at 24 h (***, P = 0.0001), and this effect was inhibited by C5aR blockade (**, P = 0.0013). Data are representative of two independent experiments and are presented as means ± SEM.

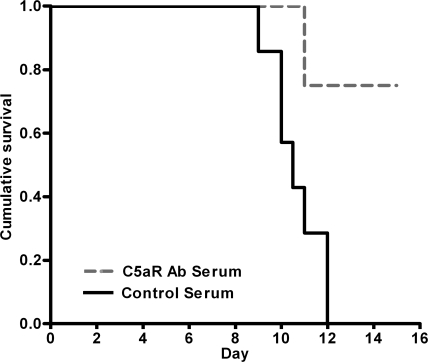

C5a and C5aR blockade rescues susceptible mice from experimental CM

The above genetic approaches implicated C5 in the pathogenesis of CM. C5 cleavage generates two effector pathways, the potent anaphylatoxin C5a and C5b, which initiates the C5b-9 membrane attack complex. To distinguish the role of C5a from the C5b-9 membrane attack complex in PbA infection and to provide direct evidence that C5a is a mediator of CM rather than a consequence of infection, we performed C5a and C5aR blockade experiments to determine whether we could protect susceptible mice from CM. Treatment of B10.D2/nSnJ (C5-sufficient) mice with anti-C5aR antibodies early in PbA infection (2 h before and 30 h after infection) conferred significant protection from CM compared with mice that received control serum (P = 0.0022 using a log-rank test; Fig. 7). Similar results were obtained using anti-C5a serum (P = 0.0019 using a log-rank test; unpublished data). These data provide the first direct evidence that the blockade of complement activation improves outcome in experimental CM and demonstrate that C5a–C5aR interactions play a central role in initiating and/or amplifying CM.

Figure 7.

Blockade of C5a–C5aR protects susceptible mice from the development of CM. To identify whether CM outcome in C5-sufficient mice could be modulated, C5aR was blocked using antibody treatment of PbA-infected mice. B10.D2/nSnJ (C5-sufficient) mice that received anti-C5aR serum (n = 8) were significantly protected from developing CM compared with controls receiving nonimmune serum (n = 7; P = 0.0022 and χ2 = 9.414 using a log-rank test). 100% of B10.D2/nSnJ mice treated with nonimmune serum developed CM compared with 0% of B10.D2/nSnJ mice treated with anti-C5aR serum.

DISCUSSION

This study provides the first evidence implicating excessive activation of the complement system, in particular C5a, in mediating experimental CM. We demonstrate a spectrum of differential susceptibility to PbA-induced CM associated with the presence or absence of C5 (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). A role for C5 was confirmed by reciprocal transfer of C5-defective or -sufficient alleles in recombinant congenic mice and by parasite challenge of genetically identical mice that differ only at the C5 locus (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). In vitro experiments suggest that the mechanism by which C5a contributes to CM includes the potentiation of host inflammatory responses to malaria products such as PfGPI (Fig. 6). Additionally, our findings that disruption of C5a–C5aR interactions blocks augmented inflammatory responses in vitro and leads to protection from CM in vivo (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7) demonstrate that complement activation has a pivotal and causative role in mediating or amplifying the CM syndrome. Collectively, these data provide direct evidence for a role for C5a in the development of CM in the PbA model and suggest a potential role for excessive complement activation in the pathogenesis of CM.

There are several putative mechanisms by which excessive complement activation might mediate or augment the pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying CM. During sepsis, activation of the complement system, particularly the generation of C5a, has been associated with several deleterious impacts on host defense, including defective phagocyte function and oxidative killing; potentiated macrophage chemokine and cytokine secretion in response to TLR ligands such as LPS, caspase activation, T cell apoptosis, and associated immunodeficiency; and enhanced secretion of proinflammatory mediators and tissue factor from endothelium (17, 19, 21). Excessive generation of C5a during severe malaria infections may contribute to similar defects in host response. C5a has been shown to up-regulate several endothelial cell adhesion molecules relevant to parasite sequestration and malaria pathogenesis, including intercellular cellular adhesion molecule 1, vascular cellular adhesion molecule 1, and P- and E-selectins (21, 34–36). Increased expression of adhesion molecules, particularly in the cerebral microvasculature, would be expected to enhance leukocyte and parasitized erythrocyte adherence to endothelium, contributing to the release of toxic mediators, disruption of microcirculatory flow and regional metabolism, and endothelial cell activation and injury that characterize CM (37–39). Similar to sepsis, dysregulated inflammatory responses to microbial products have also been implicated as key factors in the pathogenesis of human CM (3, 10, 32, 33). Parasite products such as PfGPI have been shown to induce inflammatory mediators in a TLR2-dependant manner (31–33). In this study, we show that C5a enhances PfGPI-induced inflammatory responses (Fig. 6), as it does for LPS (40–42), and may contribute to the marked inflammatory response and endothelial cell activation that are central to the pathophysiology of CM (3, 32, 43, 44). In addition, C5aRs are constitutively expressed by CNS neurons, suggesting that they may be at risk in settings of CM-associated inflammation and complement activation (45).

Several studies have reported that parasite burden does not appear to play a pivotal role in the development of CM in the PbA model (8, 9, 32). Consistent with these data, we observed no significant difference in parasitemia between CM-susceptible and -resistant mice, suggesting that C5/C5a does not significantly affect parasite burden (7–9, 32). However, we observed that highly susceptible 129sv/J mice had significantly higher parasite densities than either susceptible or resistant mice (Fig. 1 B and Fig. S1). The inability of this strain to control initial parasitemia may predispose 129sv/J mice to more severe disease and the rapid development of CM. As suggested by Amante et al. (46), these findings indicate that parasite burden may also contribute to the pathogenesis of experimental CM. Collectively, these observations indicate that CM is a complex and polygenic process, and that in highly susceptible and highly resistant strains other genetic factors, in addition to C5, contribute to the phenotypes observed. Although the precise genetic determinants regulating the control of acute blood-stage parasite replication in P. berghei are unknown, studies have identified several loci, including Char1, Char2, Char3, and Char9, in the control of peak parasitemia in P. chabaudi–infected mice (47–50); more recently, Berr1, Berr3, Berr4, and cmsc loci on chromosomes 1, 9, 4, and 17 (in the H-2 region), respectively, have been associated with the genetic control of host response (26, 51–52).

Current evidence indicates that a tightly regulated proinflammatory response is critical in the control and resolution of malaria infection, whereas excessive and sustained inflammatory responses contribute to immunopathology (8,10-12, 53–55). Similar to inflammatory responses to infection, our findings indicate that both the timing and the peak concentrations of C5a are important in determining outcome. We show that early induction of C5 activation during the course of infection contributes to potentiated inflammatory responses and predisposes mice to the development of CM (e.g., C57BL/6 mice). Conversely, BALB/c mice do not display early activation of C5 but rather a gradual activation that may facilitate the regulated responses necessary for the control of acute PbA infection while limiting host immunopathology.

High levels of circulating C5a in the susceptible mice are consistent with studies of severe malaria and experimental malaria challenge models in humans, which reported activation of the complement system by both the classical and alternative pathways during human infection (56–58). The observation that C5a appears very early in the course of experimental CM supports its role as a potential early mediator and also suggests that it may be a useful biomarker to predict those who will go on to develop CM. Because only a small proportion of malaria-infected individuals progress to severe disease, a predictive biomarker would be of clinical utility in identifying and more effectively allocating therapeutic resources to those at greater risk of adverse outcomes. To be valuable as a biomarker would require that C5a levels have a predictive value in patients who are at risk of CM but have not yet developed the syndrome. To define the role of C5a as a putative mediator of human CM and determine whether elevated C5a levels will be a useful biomarker will require additional study in prospective clinical trials.

Interventions that prevent CM would be of potential clinical benefit in the management of human P. falciparum infection (2). In this study, C5a–C5aR blockade results in significant protection against CM in infected susceptible mice (Fig. 7). Although the precise trigger of complement activation during malaria infection requires further investigation, the observations that C5a is required for the development of experimental CM and that blockade of C5a–C5aR activity early in the course of PbA infection improves outcome identify C5a–C5aR as a potential target for intervention in human severe malaria and CM. Additional studies are required to investigate the potential role of C5a in human infection, including CM induced by P. falciparum malaria. If C5a is subsequently shown to be an important mediator in CM in humans, then the availability of inhibitors of C5a–C5aR, including receptor antagonists and an FDA-approved humanized monoclonal antibody against C5, might permit direct testing of the hypothesis that C5a–C5aR blockade will improve clinical outcome (59). In summary, these data provide direct evidence for a role for C5a in the development of CM in the PbA model, and suggest a potential role for excessive complement activation and C5a generation in particular, in the pathophysiology of human CM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice, parasites, and experimental infections.

Experiments involving animals were reviewed and approved by the University of Toronto Animal Use Committee and were performed in compliance with current University of Toronto animal use guidelines. Mice used in this study were 8–16 wk old and were maintained under pathogen-free conditions with a 12-h light cycle. C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. 129sv/J, C3H/HeN, 129P3/J, DBA/2J, A/J, AKR/J, B10.D2/oSnJ, and B10.D2/nSnJ mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory.

PbA parasites were maintained by passage through naive C57BL/6 mice, as previously described (29, 32). Experimental infections were initiated by i.p. injection of 5 × 105 PbA-parasitized erythrocytes. The course of infection was monitored twice daily for neurological symptoms including mono-, hemi-, para-, or tetraplegia, movement disorder, ataxia, hunching, convulsions, and coma, to define CM as previously described (3–9, 26–28, 46, 60). Mice were judged to have CM if they displayed these neurological criteria within days 6–10 after infection and either succumbed to infection or were humanely killed as per the requirements of our institutional animal use committee. Parasitemias were monitored using thin blood smears stained with modified Giemsa stain (Protocol Hema 3 stain set; Sigma-Aldrich) from 3 d after infection onwards. CM was confirmed by histological examination of cerebral pathology. Brain tissue was carefully removed, fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded, sectioned (5 μM), and stained with Giemsa or hematoxylin and eosin.

C5 deficiency and sequencing of the C5 gene in BALB/c mice.

All C5-deficient mice used in this study had a bp deletion at positions 62 and 63 of the C5 gene, which was fixed in several strains during their generation. This frame-shift caused a premature stop codon that resulted in these mice being unable to produce C5 mRNA or functional C5 protein.

The coding region of the Hc (C5) gene (available from GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ under GeneID no. 15139) was completely sequenced from BALB/c/Cr genomic DNA. Primers were designed to amplify all coding exons and a minimum of 100 bp in each direction of the flanking introns using Primer3 (Table S1, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20072248/DC1) (61). Targets were PCR amplified with Taq Platinum HiFi (Invitrogen) using 50 ng DNA per reaction in a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems). Fragments were visualized on an agarose gel. The PCR conditions were an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 25 cycles of denaturing at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 53–59°C for 30 s, and extension at 68°C for 60 s. 5 μl of PCR product was treated with the ExoSap-IT kit containing exonuclease I and shrimp alkaline phosphotase, according to the manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare), to remove primers and unbound nucleotides. Purified PCR products were sequenced using the BigDye Terminator v3.0 cycle sequencing kit and an automated ABI 3700 instrument (Applied Biosystems).

Generation of recombinant (AcB/BcA) congenic mice.

The AcB/BcA recombinant congenic strains were derived by systematic inbreeding from a double backcross (N3) between A/J and C57BL/6 parents (30). In this breeding scheme, each of these strains derives 12.5% of its genome from either A/J or C57BL/6, fixed as a set of discrete congenic segments on the background of the other parental strain (87.5% of its genome). AcB55 recombinant congenic mice were on an A/J background containing a gene segment bearing a functional C5 gene from C57BL/6 mice. Conversely, BcA76 recombinant congenic mice carry within their congenic regions the C5 mutant gene from A/J mice on a C57BL/6 background.

Measurement of serum C5a levels in mice.

C5a levels were assayed in serum specimens from PbA-infected and uninfected B10.D2/oSnJ, B10.D2/nSnJ, C57BL/6, BALB/c, and A/J mice using a sandwich ELISA. In brief, a 96-well plate was coated with purified 2 μg/ml of rat anti–mouse C5a antibody in 0.1 M NaHPO4 coating buffer, pH 9.5 (BD Biosciences), overnight at 4°C. The plate was washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and blocked with PBS/10% FBS for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were diluted 1:100 in blocking buffer and incubated for 2 h, followed by five washes. Bound C5a was detected using biotinylated 1 μg/ml of rat anti–mouse C5a antibody and avidin–horseradish peroxidase. Reactive C5a levels were measured using 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min, and the reaction was stopped using 2 N H2SO4. The plate was read at an OD of 405 nm.

Real-Time RT-PCR detection of C5 mRNA levels.

Total RNA was extracted from whole blood using RNeasy columns according to the manufacturer's instructions (QIAGEN). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using Superscript II RT with Oligo (dT)12-18 primers (Invitrogen). A standard curve of mouse genomic DNA (Fermentas) was used as described previously (62). gDNA standards or cDNA were added to the real-time PCR reaction containing 1× Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and 0.5 μM of primers (Table S2, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20072248/DC1) in a final volume of 10 μl. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using a sequence detection system (ABI Prism 7900HT; Applied Biosystems). C5 copy numbers were normalized to the housekeeping genes Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh), Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl-transferase 1 (Hprt), Succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit A (Sdha), and Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein, ζ polypeptide (Ywhaz) (63).

C5a- and PfGPI-induced cytokine production.

Human PBMCs were isolated from the venous blood of healthy volunteers and plated at a density of 106 cells per well. Cells were separated into three groups and treated as follows: control (no treatment), anti-CD88 (5 μg/ml of mouse anti–human CD88; Serotec), or isotype control antibody (5 μg/ml of mouse anti–human IgG2a; BD Biosciences). Within each group, cells were incubated with media (control), 50 nM C5a (Biovision), 300 ng/ml of HPLC-purified PfGPI, or C5a and PfGPI for 24 h. Supernatants were collected and assayed for TNF-α and IL-6 cytokine production using a cytometric bead array (BD Biosciences).

C5a and C5aR1 blockade in PbA infection in vivo.

To block C5a–C5aR interactions, B10.D2/nSnJ (C5-sufficient) mice were administered either anti-C5a goat serum or anti-C5aR rabbit serum in two independent experiments, as previously described (64, 65). The treatment groups received either 0.5 ml anti-C5a or anti-C5aR serum i.p. 2 h before parasite challenge, and the control groups received 0.5 ml of corresponding nonimmune serum (control serum). Mice were challenged with 5 × 105 PbA-parasitized erythrocytes. After 30–32 h, mice received a second injection of 0.5 ml anti-C5a, anti-C5aR, or control serum. Mice were monitored for 15 d.

Statistical analysis.

Survival studies were analyzed using the log-rank test, parasitemias were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparison test, and serum C5a levels were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Data are presented as means ± SD unless otherwise noted. All experiments were repeated at least two times.

Online supplemental material.

Fig. S1 shows the parasitemia data over the course of infection for various strains infected with PbA. Table S1 shows the primers used to sequence the C5 gene from BALB/c mice. Primers were designed using Primer3 (61) to amplify all exons and a minimum of 100 bp in each direction of the flanking introns. Table S2 shows the primers used for quantitative real-time RT-PCR detection of C5 mRNA levels in mice. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20072248/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Team Grant in Malaria (to K.C. Kain), operating grant MT-13721 (to K.C. Kain), Genome Canada through the Ontario Genomics Institute (K.C. Kain), the Canadian Genetics Disease Network (P. Gros), the CIHR Canada Research Chair (K.C. Kain and W.C. Liles), and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants AI41139 (to D.C. Gowda), GM 29507 (to P.A. Ward), GM 61656 (to P.A. Ward), and HL-31963 (to P.A. Ward).

None of the authors have conflicting financial interests.

Abbreviations used: CM, cerebral malaria; PbA, Plasmodium berghei ANKA; PfGPI, P. falciparum glycosylphosphatidylinositol; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

P. Gros and K.C. Kain contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Dondorp, A., F. Nosten, K. Stepniewska, N. Day, and N. White. 2005. Artesunate versus quinine for treatment of severe falciparum malaria: a randomised trial. Lancet. 366:717–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White, N.J. 1998. Not much progress in treatment of cerebral malaria. Lancet. 352:594–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schofield, L., M.C. Hewitt, K. Evans, M.A. Siomos, and P.H. Seeberger. 2002. Synthetic GPI as a candidate anti-toxic vaccine in a model of malaria. Nature. 418:785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Souza, J.B., and E.M. Riley. 2002. Cerebral malaria: the contribution of studies in animal models to our understanding of immunopathogenesis. Microbes Infect. 4:291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gimenez, F., S. Barraud de Lagerie, C. Fernandez, P. Pino, and D. Mazier. 2003. Tumor necrosis factor alpha in the pathogenesis of cerebral malaria. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60:1623–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jennings, V.M., J.K. Actor, A.A. Lal, and R.L. Hunter. 1997. Cytokine profile suggesting that murine cerebral malaria is an encephalitis. Infect. Immun. 65:4883–4887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennings, V.M., A.A. Lal, and R.L. Hunter. 1998. Evidence for multiple pathologic and protective mechanisms of murine cerebral malaria. Infect. Immun. 66:5972–5979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen, D.S., K.J. Evans, M.C. D'Ombrain, N.J. Bernard, A.C. Sexton, L. Buckingham, A.A. Scalzo, and L. Schofield. 2005. The natural killer complex regulates severe malarial pathogenesis and influences acquired immune responses to Plasmodium berghei ANKA. Infect. Immun. 73:2288–2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engwerda, C.R., T.L. Mynott, S. Sawhney, J.B. De Souza, Q.D. Bickle, and P.M. Kaye. 2002. Locally up-regulated lymphotoxin α, not systemic tumor necrosis factor α, is the principle mediator of murine cerebral malaria. J. Exp. Med. 195:1371–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevenson, M.M., and E.M. Riley. 2004. Innate immunity to malaria. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:169–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Day, N.P., T.T. Hien, T. Schollaardt, P.P. Loc, L.V. Chuong, T.T. Chau, N.T. Mai, N.H. Phu, D.X. Sinh, N.J. White, and M. Ho. 1999. The prognostic and pathophysiologic role of pro- and antiinflammatory cytokines in severe malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1288–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Omer, F.M., and E.M. Riley. 1998. Transforming growth factor β production is inversely correlated with severity of murine malaria infection. J. Exp. Med. 188:39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Kossodo, S., and G.E. Grau. 1993. Profiles of cytokine production in relation with susceptibility to cerebral malaria. J. Immunol. 151:4811–4820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Kossodo, S., and G.E. Grau. 1993. Role of cytokines and adhesion molecules in malaria immunopathology. Stem Cells. 11:41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golenser, J., J. McQuillan, L. Hee, A.J. Mitchell, and N.H. Hunt. 2006. Conventional and experimental treatment of cerebral malaria. Int. J. Parasitol. 36:583–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo, R.F., and P.A. Ward. 2005. Role of C5a in inflammatory responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23:821–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riedemann, N.C., T.A. Neff, R.F. Guo, K.D. Bernacki, I.J. Laudes, J.V. Sarma, J.D. Lambris, and P.A. Ward. 2003. Protective effects of IL-6 blockade in sepsis are linked to reduced C5a receptor expression. J. Immunol. 170:503–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward, P.A. 2004. The dark side of C5a in sepsis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huber-Lang, M., J.V. Sarma, F.S. Zetoune, D. Rittirsch, T.A. Neff, S.R. McGuire, J.D. Lambris, R.L. Warner, M.A. Flierl, L.M. Hoesel, et al. 2006. Generation of C5a in the absence of C3: a new complement activation pathway. Nat. Med. 12:682–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chenoweth, D.E., and T.E. Hugli. 1978. Demonstration of specific C5a receptor on intact human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 75:3943–3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Czermak, B.J., M. Breckwoldt, Z.B. Ravage, M. Huber-Lang, H. Schmal, N.M. Bless, H.P. Friedl, and P.A. Ward. 1999. Mechanisms of enhanced lung injury during sepsis. Am. J. Pathol. 154:1057–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smedegard, G., L.X. Cui, and T.E. Hugli. 1989. Endotoxin-induced shock in the rat. A role for C5a. Am. J. Pathol. 135:489–497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huber-Lang, M., V.J. Sarma, K.T. Lu, S.R. McGuire, V.A. Padgaonkar, R.F. Guo, E.M. Younkin, R.G. Kunkel, J. Ding, R. Erickson, et al. 2001. Role of C5a in multiorgan failure during sepsis. J. Immunol. 166:1193–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huber-Lang, M.S., J.V. Sarma, S.R. McGuire, K.T. Lu, R.F. Guo, V.A. Padgaonkar, E.M. Younkin, I.J. Laudes, N.C. Riedemann, J.G. Younger, and P.A. Ward. 2001. Protective effects of anti-C5a peptide antibodies in experimental sepsis. FASEB J. 15:568–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagayasu, E., K. Nagakura, M. Akaki, G. Tamiya, S. Makino, Y. Nakano, M. Kimura, and M. Aikawa. 2002. Association of a determinant on mouse chromosome 18 with experimental severe Plasmodium berghei malaria. Infect. Immun. 70:512–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohno, T., and M. Nishimura. 2004. Detection of a new cerebral malaria susceptibility locus, using CBA mice. Immunogenetics. 56:675–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delahaye, N.F., N. Coltel, D. Puthier, L. Flori, R. Houlgatte, F.A. Iraqi, C. Nguyen, G.E. Grau, and P. Rihet. 2006. Gene-expression profiling discriminates between cerebral malaria (CM)-susceptible mice and CM-resistant mice. J. Infect. Dis. 193:312–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lou, J., R. Lucas, and G.E. Grau. 2001. Pathogenesis of cerebral malaria: recent experimental data and possible applications for humans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:810–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lovegrove, F.E., L. Pena-Castillo, N. Mohammad, W.C. Liles, T.R. Hughes, and K.C. Kain. 2006. Simultaneous host and parasite expression profiling identifies tissue-specific transcriptional programs associated with susceptibility or resistance to experimental cerebral malaria. BMC Genomics. 7:295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fortin, A., E. Diez, D. Rochefort, L. Laroche, D. Malo, G.A. Rouleau, P. Gros, and E. Skamene. 2001. Recombinant congenic strains derived from A/J and C57BL/6J: a tool for genetic dissection of complex traits. Genomics. 74:21–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel, S.N., Z. Lu, K. Ayi, L. Serghides, D.C. Gowda, and K.C. Kain. 2007. Disruption of CD36 impairs cytokine response to Plasmodium falciparum glycosylphosphatidylinositol and confers susceptibility to severe and fatal malaria in vivo. J. Immunol. 178:3954–3961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu, Z., L. Serghides, S.N. Patel, N. Degousee, B.B. Rubin, G. Krishnegowda, D.C. Gowda, M. Karin, and K.C. Kain. 2006. Disruption of JNK2 decreases the cytokine response to Plasmodium falciparum glycosylphosphatidylinositol in vitro and confers protection in a cerebral malaria model. J. Immunol. 177:6344–6352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krishnegowda, G., A.M. Hajjar, J. Zhu, E.J. Douglass, S. Uematsu, S. Akira, A.S. Woods, and D.C. Gowda. 2005. Induction of proinflammatory responses in macrophages by the glycosylphosphatidylinositols of Plasmodium falciparum: cell signaling receptors, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) structural requirement, and regulation of GPI activity. J. Biol. Chem. 280:8606–8616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albrecht, E.A., A.M. Chinnaiyan, S. Varambally, C. Kumar-Sinha, T.R. Barrette, J.V. Sarma, and P.A. Ward. 2004. C5a-induced gene expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Am. J. Pathol. 164:849–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Floreani, A.A., T.A. Wyatt, J. Stoner, S.D. Sanderson, E.G. Thompson, D. Allen-Gipson, and A.J. Heires. 2003. Smoke and C5a induce airway epithelial intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and cell adhesion. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 29:472–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wada, K., M.C. Montalto, and G.L. Stahl. 2001. Inhibition of complement C5 reduces local and remote organ injury after intestinal ischemia/reperfusion in the rat. Gastroenterology. 120:126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner, G.D., V.C. Ly, T.H. Nguyen, T.H. Tran, H.P. Nguyen, D. Bethell, S. Wyllie, K. Louwrier, S.B. Fox, K.C. Gatter, et al. 1998. Systemic endothelial activation occurs in both mild and severe malaria. Correlating dermal microvascular endothelial cell phenotype and soluble cell adhesion molecules with disease severity. Am. J. Pathol. 152:1477–1487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner, G.D., H. Morrison, M. Jones, T.M. Davis, S. Looareesuwan, I.D. Buley, K.C. Gatter, C.I. Newbold, S. Pukritayakamee, B. Nagachinta, et al. 1994. An immunohistochemical study of the pathology of fatal malaria. Evidence for widespread endothelial activation and a potential role for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in cerebral sequestration. Am. J. Pathol. 145:1057–1069. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor, T.E., W.J. Fu, R.A. Carr, R.O. Whitten, J.S. Mueller, N.G. Fosiko, S. Lewallen, N.G. Liomba, and M.E. Molyneux. 2004. Differentiating the pathologies of cerebral malaria by postmortem parasite counts. Nat. Med. 10:143–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riedemann, N.C., R.F. Guo, T.J. Hollmann, H. Gao, T.A. Neff, J.S. Reuben, C.L. Speyer, J.V. Sarma, R.A. Wetsel, F.S. Zetoune, and P.A. Ward. 2004. Regulatory role of C5a in LPS-induced IL-6 production by neutrophils during sepsis. FASEB J. 18:370–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaeffer, V., J. Cuschieri, I. Garcia, M. Knoll, J. Billgren, S. Jelacic, E. Bulger, and R. Maier. 2007. The priming effect of C5a on monocytes is predominantly mediated by the p38 MAPK pathway. Shock. 27:623–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mack, C., K. Jungermann, O. Gotze, and H.L. Schieferdecker. 2001. Anaphylatoxin C5a actions in rat liver: synergistic enhancement by C5a of lipopolysaccharide-dependent alpha(2)-macroglobulin gene expression in hepatocytes via IL-6 release from Kupffer cells. J. Immunol. 167:3972–3979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hollestelle, M.J., C. Donkor, E.A. Mantey, S.J. Chakravorty, A. Craig, A.O. Akoto, J. O'Donnell, J.A. van Mourik, and J. Bunn. 2006. von Willebrand factor propeptide in malaria: evidence of acute endothelial cell activation. Br. J. Haematol. 133:562–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiser, S., J. Miu, H.J. Ball, and N.H. Hunt. 2007. Interferon-gamma synergises with tumour necrosis factor and lymphotoxin-alpha to enhance the mRNA and protein expression of adhesion molecules in mouse brain endothelial cells. Cytokine. 37:84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Barr, S.A., J. Caguioa, D. Gruol, G. Perkins, J.A. Ember, T. Hugli, and N.R. Cooper. 2001. Neuronal expression of a functional receptor for the C5a complement activation fragment. J. Immunol. 166:4154–4162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amante, F.H., A.C. Stanley, L.M. Randall, Y. Zhou, A. Haque, K. McSweeney, A.P. Waters, C.J. Janse, M.F. Good, G.R. Hill, and C.R. Engwerda. 2007. A role for natural regulatory T cells in the pathogenesis of experimental cerebral malaria. Am. J. Pathol. 171:548–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foote, S.J., R.A. Burt, T.M. Baldwin, A. Presente, A.W. Roberts, Y.L. Laural, A.M. Lew, and V.M. Marshall. 1997. Mouse loci for malaria-induced mortality and the control of parasitaemia. Nat. Genet. 17:380–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fortin, A., A. Belouchi, M.F. Tam, L. Cardon, E. Skamene, M.M. Stevenson, and P. Gros. 1997. Genetic control of blood parasitaemia in mouse malaria maps to chromosome 8. Nat. Genet. 17:382–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fortin, A., L.R. Cardon, M. Tam, E. Skamene, M.M. Stevenson, and P. Gros. 2001. Identification of a new malaria susceptibility locus (Char 4) in recombinant congenic strains of mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:10793–10798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burt, R.A., T.M. Baldwin, V.M. Marshall, and S.J. Foote. 1999. Temporal expression of an H2-linked locus in host response to mouse malaria. Immunogenetics. 50:278–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Campino, S., S. Bagot, M.L. Bergman, P. Almeida, N. Sepulveda, S. Pied, C. Penha-Goncalves, D. Holmberg, and P.A. Cazenave. 2005. Genetic control of parasite clearance leads to resistance to Plasmodium berghei ANKA infection and confers immunity. Genes Immun. 6:416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bagot, S., S. Campino, C. Penha-Goncalves, S. Pied, P.A. Cazenave, and D. Holmberg. 2002. Identification of two cerebral malaria resistance loci using an inbred wild-derived mouse strain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:9919–9923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mitchell, A.J., A.M. Hansen, L. Hee, H.J. Ball, S.M. Potter, J.C. Walker, and N.H. Hunt. 2005. Early cytokine production is associated with protection from murine cerebral malaria. Infect. Immun. 73:5645–5653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lyke, K.E., R. Burges, Y. Cissoko, L. Sangare, M. Dao, I. Diarra, A. Kone, R. Harley, C.V. Plowe, O.K. Doumbo, and M.B. Sztein. 2004. Serum levels of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 beta (IL-1beta), IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IL-12(p70) in Malian children with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria and matched uncomplicated malaria or healthy controls. Infect. Immun. 72:5630–5637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Awandare, G.A., B. Goka, P. Boeuf, J.K. Tetteh, J.A. Kurtzhals, C. Behr, and B.D. Akanmori. 2006. Increased levels of inflammatory mediators in children with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria with respiratory distress. J. Infect. Dis. 194:1438–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wenisch, C., S. Spitzauer, K. Florris-Linau, H. Rumpold, S. Vannaphan, B. Parschalk, W. Graninger, and S. Looareesuwan. 1997. Complement activation in severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 85:166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roestenberg, M., M. McCall, T.E. Mollnes, M. van Deuren, T. Sprong, I. Klasen, C.C. Hermsen, R.W. Sauerwein, and A. van der Ven. 2007. Complement activation in experimental human malaria infection. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 101:643–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stoute, J.A., A.O. Odindo, B.O. Owuor, E.K. Mibei, M.O. Opollo, and J.N. Waitumbi. 2003. Loss of red blood cell-complement regulatory proteins and increased levels of circulating immune complexes are associated with severe malarial anemia. J. Infect. Dis. 187:522–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hillmen, P., N.S. Young, J. Schubert, R.A. Brodsky, G. Socie, P. Muus, A. Roth, J. Szer, M.O. Elebute, R. Nakamura, et al. 2006. The complement inhibitor eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N. Engl. J. Med. 355:1233–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Neill, A.L., and N.H. Hunt. 1992. Pathology of fatal and resolving Plasmodium berghei cerebral malaria in mice. Parasitology. 105:165–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rozen, S., and H. Skaletsky. 2000. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. 132:365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yun, J.J., L.E. Heisler, I.I. Hwang, O. Wilkins, S.K. Lau, M. Hyrcza, B. Jayabalasingham, J. Jin, J. McLaurin, M.S. Tsao, and S.D. Der. 2006. Genomic DNA functions as a universal external standard in quantitative real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vandesompele, J., K. De Preter, F. Pattyn, B. Poppe, N. Van Roy, A. De Paepe, and F. Speleman. 2002. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 3:research0034.1–research0034.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Riedemann, N.C., R.F. Guo, T.A. Neff, I.J. Laudes, K.A. Keller, V.J. Sarma, M.M. Markiewski, D. Mastellos, C.W. Strey, C.L. Pierson, et al. 2002. Increased C5a receptor expression in sepsis. J. Clin. Invest. 110:101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ward, P.A., N.C. Riedemann, R.F. Guo, M. Huber-Lang, J.V. Sarma, and F.S. Zetoune. 2003. Anti-complement strategies in experimental sepsis. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 35:601–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.