Abstract

Androgen deprivation induces the regression of prostate tumors mainly due to an increase in the apoptosis rate; however, the molecular mechanisms underlying the antiapoptotic actions of androgens are not completely understood. We have studied the antiapoptotic effects of androgens in prostate cancer cells exposed to different proapoptotic stimuli. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated nick-end labeling and nuclear fragmentation analyses demonstrated that androgens protect LNCaP prostate cancer cells from apoptosis induced by thapsigargin, the phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoyl-13-phorbol-acetate, or UV irradiation. These three stimuli require the activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway to induce apoptosis and in all three cases, androgen treatment blocks JNK activation. Interestingly, okadaic acid, a phosphatase inhibitor that causes apoptosis in LNCaP cells, induces JNK activation that is also inhibited by androgens. Actinomycin D, the antiandrogen bicalutamide or specific androgen receptor (AR) knockdown by small interfering RNA all blocked the inhibition of JNK activation mediated by androgens indicating that this activity requires AR-dependent transcriptional activation. These data suggest that the crosstalk between AR and JNK pathways may have important implications in prostate cancer progression and may provide targets for the development of new therapies.

Introduction

Prostate cancer constitutes a major health problem in Western countries. It has been predicted that in 2007 prostate cancer will become the most common noncutaneous cancer in men [1]. Prostate tumors are typically androgen dependent during initial stages and are therefore responsive to androgen deprivation therapy. The removal of androgens during the initial stages of prostate cancer causes tumor regression through a combination of reduced cellular proliferation and increased apoptosis [2–4]. Despite the initial efficacy of androgen deprivation therapy, most prostate cancers progress to androgen-independent disease at which stage no effective therapy is currently available [5–7]. The acquisition of resistance to apoptosis that accompanies the transition to androgen independence is one of the hallmarks of advanced prostate cancers [8]. Better understanding of the antiapoptotic action of androgens and the mechanisms by which prostate cancer cells can bypass apoptotic signals are essential for the development of new strategies in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer.

Androgens exert their effects mainly through binding to androgen receptor (AR), a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Upon hormone binding, AR translocates into the nucleus where it binds to specific response elements. A number of co-regulators and/or co-regulator complexes are recruited to AR, which then control the transcription of various target genes [9,10]. Many of these AR target genes are deregulated during the later, “androgen-independent” phase of prostate cancer [11]. Current data suggest that although prostate cancer cells become androgen independent, AR is expressed and is functional during tumor progression, suggesting an important role for AR signaling during all phases of prostate carcinogenesis [12,13].

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are among the most widely used signal transduction pathways in eukaryotic cells. One of the main MAPKs, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK, also called stress-activated protein kinase) is known to play a critical role in different cellular activities, including cell growth and programmed cell death (reviewed in Ref. [14]). Similar to other MAPKs, JNK is activated by sequential protein phosphorylation through a MAPK module [15] and can be inactivated by the action of specific phosphatases (tyrosine, serine/threonine, and the dual-specificity phosphatases) (for a review, see Ref. [16]). Once activated, JNK phosphorylates and activates numerous downstream effectors, among them a number of transcription factors such as c-Jun, the major component of the AP-1 complex [17].

Crosstalk between these two protein families, nuclear receptors and MAPKs, has previously been reported. Originally described for the reciprocal inhibition between the ligand-bound glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and the activated transcription factor AP-1, this antagonism was later shown to exist for different members of the nuclear receptor superfamily (for reviews, see Refs. [18–20]), including AR [21,22], for which competition for limiting cofactors in the cell, such as CBP, has been implicated [22,23]. However, from studies on other nuclear receptors it is known that there are additional potential mechanisms for this crosstalk. For example, the cross-inhibition between GR and AP-1 may occur through mutual inhibition of DNA binding, prevention of fruitful interactions with the transcriptional initiation complex, interference with the JNK signaling pathway, and direct GR-JNK interactions that cause direct inhibition of JNK pathway activation [24–27].

To study the possible interaction between AR and the JNK pathway we used the androgen-responsive prostate cancer cell line LNCaP cells. Previous studies carried out in our laboratory demonstrated that the treatment of LNCaP cells with the phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoyl-13-phorbol-acetate (TPA), an activator of protein kinase C [28–30], or with thapsigargin (TG), an inhibitor of the Ca2+ ATPase present in the endoplasmic reticulum [31], induced JNK activation and concomitant apoptosis [32]. Supporting the involvement of JNK in apoptosis, the specific inhibition of JNK signaling significantly reduced the levels of apoptosis induced by TPA and TG [32,33].

In this study we demonstrate that androgens block JNK activation with concomitant inhibition of apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Androgen-induced JNK inhibition was independent of the JNK-activating stimulus and, therefore, these data establish JNK itself as a new focal point in the crosstalk between the AR and AP-1 signaling pathways. We show, for the first time, that inhibition of JNK activity by androgens occurs in a dose- and time-dependent manner and requires functional AR and AR-dependent de novo gene expression.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

Cell culture conditions and cell death induction have been described previously [32]. Briefly, the human prostate cancer cell lines, LNCaP, PC3, and DU145 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine (all from BioWhittaker-Cambrex, Verviers, Belgium) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air at 37°C. PC3-AR [34] and DU145-AR [35] cells were kindly provided by Dr. M. Marcelli and Dr. el-N. Lalani, respectively. To deplete the cells from androgens and lower the basal levels of activated JNK before any of the treatments, the cells were kept in low-serum media: 2 days in 2% charcoal-treated serum and 16 to 20 hours in 0.5% charcoal-treated serum. All the treatments were done in 0.5% charcoal-treated serum media. When indicated, cells were treated with the following concentrations of the compounds: R1881 10-8 or 10-7 M, as indicated (unless indicated differently, R1881 treatments are for 40 hours before the addition of TPA or TG, or UV irradiation), TPA 5 ng/ml, TG 100 nM, actinomycin D (ActD) 1 µg/ml, bicalutamide 10 to 100 µM. TPA, TG, and ActD were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Bicalutamide was obtained from Astra Zeneca (Cheshire, UK).

Apoptosis and Viability Assays

Viability in LNCaP cells was assessed by trypan blue exclusion assay. The cells were grown in six multiwell plates, harvested by trypsinization at indicated times, and gently resuspended in a small volume of PBS (100 to 150 µl/well). Ten microliters of cell suspension was mixed with 10 µl of trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich) previously diluted 1:1 with PBS. After 1 minute, cells were examined under the microscope for nonviable cells, indicated by trypan blue uptake. A minimum of 300 cells were counted for each well. Each experiment was done in triplicates and was repeated at least three times. The percentage of nonviable cells was expressed per 100 of the total cells (mean ± SD).

Apoptosis incidence was assessed by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining and the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay. For the detection of fragmented nuclei, cells were grown on coverslips and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy after DAPI staining. At least five areas and a minimum of 1000 cells were counted for each plate. The experiment was done in duplicate and repeated twice. Fragmented nuclei incidence was expressed per 100 of the total cells (mean ± SD). Cell apoptosis was characterized also by TUNEL assay, using the In Situ Cell Detection Kit from Roche according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the cells grown onto coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing three times with PBS, the cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1% sodium citrate for 10 minutes on ice. Cells were then stained for the TUNEL assay, and green fluorescent apoptotic bodies were visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplan2 fluorescence microscope). For the visualization of all the cells, a counterstaining with DAPI was performed. For statistical analysis, at least five areas and a minimum of 1000 cells were counted for each slide. The experiment was done in duplicate and repeated twice. The number of TUNEL-positive cells was expressed per 100 of the total cells (mean ± SD).

Western Analysis

Western analyses were performed as described previously [32]. Whole-cell extracts were prepared by lysing the cells in WCB [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.7), 300 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 20 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 2 µg/ml leupeptin, 0.5 mM PMSF] at 4°C for 2 hours. Protein extracts were resolved in SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. After blocking, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody in Tris-buffered saline-0.1% Tween (TBST) containing 5% BSA. The membranes were then incubated with the corresponding secondary antibody in TBST-5% nonfat milk for 1 hour at room temperature and the immunoreactive bands were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). Antibodies against total JNK and phospho-JNK were obtained from Cell Signaling and used at 1:500 dilution. PSA and AR antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA) and used at 1:300 and 1:500 dilutions, respectively. α-Tubulin antibody was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used at 1:5000 dilution.

Kinase Assays

Whole-cell extracts were obtained as described above for Western analysis. Solid-phase kinase assays were performed using glutathione S-transferase (GST)-cJun (1-79) as substrate, as described previously [32]. Briefly, 30 µg (for UV-treated cells) or 200 µg (for TG- and TPA-treated cells) of the protein samples were incubated with 10 µg of GST-cJun fusion protein as substrate in binding buffer (20 mM Hepes, 75 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM DTT, 20 mM glycerol phosphate, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 2 µg/ml leupeptin, 100 µg/ml PMSF) 3 hours at 4°C; the beads were washed three times and resuspended in 30 µl of kinase buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 150 mM KCl, and 10 µM ATP] and incubated for 20 minutes at 30°C in the presence of 5 µCi of [γ-32P]ATP. After size fractionation on a 12% SDS-PAGE, bands were visualized and quantified using phosphoimager analysis.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence analysis was performed as described previously, with minor modifications [36]. Briefly, LNCaP cells grown on coverslips were fixed with methanol for 10 minutes at -20°C, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in TBS and blocked in 5% BSA in TBS-0.1% Triton X-100. Phospho-JNK and total JNK primary antibodies were used overnight at 4°C at 1:50 dilution in TBS containing 3% BSA. The secondary antibody was conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594-Red. For the visualization of the nuclei, counterstaining with DAPI was performed. The slides were analyzed using confocal laser microscopy (Olympus Fluo View 1000, Olympus Europa GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) and representative images were captured.

Phosphatase Activity

Phosphatase assays were performed on intact cells. The cells were washed with buffer A (pH 7.8) (5.5 mM glucose, 136 mM NaCl, 2.6 mM KCl, 20 mM Hepes, 10 mM tricine). For phosphatase activity reaction, the same number of cells was resuspended in 0.3 ml of buffer A containing 5 mM pNPP (Sigma) and 1 mM MgCl2. After 60 minutes of incubation at 37°C, the reaction was stopped by addition of NaOH to a final concentration of 0.02 M. The amount of pNP released from pNPP, reflecting phosphatase activity, was measured at 405 nm (protocol adapted from Ref. [37]).

Small Interfering RNA-Mediated Knockdown of AR Expression

A previously described small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting AR [38] was selected to specifically knock down AR expression (siAR sense: CUGGGAAAGUCAAGCCCAUTT, purchased from Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO). LNCaP cells were transfected with siAR (200 nM) using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. The transfections were performed in triplicate and pools of the transfected cells were used for protein extraction and western analysis. siRNA targeting the luciferase gene (siLuc) was used as a negative control (Qiagen, Germantown, MD).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t test. Values of P < .05 were considered significant.

Results

R1881 Protects LNCaP Cells from TPA- and TG-induced Apoptosis

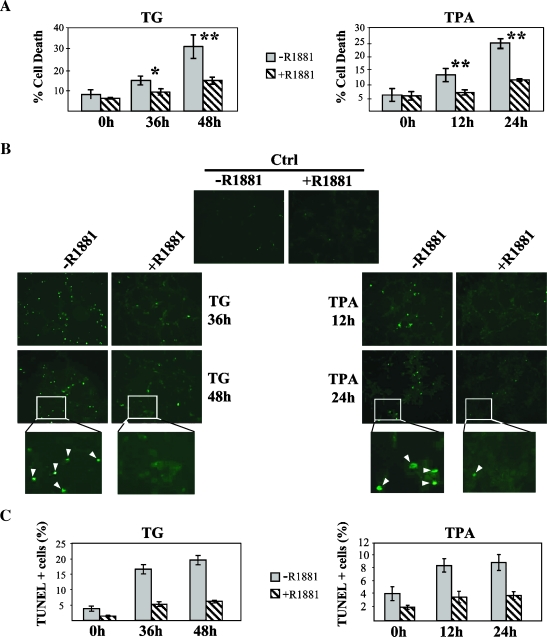

To study the effect of androgens in apoptosis of prostate cancer cells, we used two previously established models of apoptosis: TG and TPA treatments of the androgen-responsive prostate cancer cell line LNCaP cells [28,31,32]. As we previously reported, the treatment of LNCaP cells with these agents induces apoptosis that significantly increases after 12 and 36 hours for TPA and TG, respectively [32]. To assess the possible effect of androgens in apoptosis induced by these agents, we analyzed the time periods of 36 to 48 hours for TG and 12 to 24 hours for TPA, which correspond to the times during which rate of apoptosis induced by these agents starts.

We first analyzed the viability of LNCaP cells that were either left untreated or pretreated with R1881 for 40 hours, before their exposure to TG or TPA. As shown in Figure 1A, R1881 treatment decreased LNCaP cell death induced by both TG and TPA by approximately 50%. This increase in cell viability in the presence of R1881 was not due to a change in cell growth but to a decrease in cell death, because under these experimental conditions (low serum) R1881 did not affect cell proliferation (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Protective effect of androgens on TG- and TPA-induced cell death. LNCaP cells were grown on six-well plates. After a starvation period of 3 days, the cells were incubated with R1881 (10-7 M) for 40 hours followed by TG (100 nM), TPA (5 ng/ml), or vehicle for the indicated times. (A) Cell death was scored at the indicated times by trypan blue exclusion assay as described in Materials and Methods and quantified as a percentage of the total cell counts. Under these experimental conditions, significant differences were observed between the levels of cell death of cells that were treated with R1881 and those of nontreated ones. For the statistical analysis, at least three experiments were used. (*P < .01; **P < .001). (B) Microscope images of TUNEL assay on LNCaP cells at indicated times after TG and TPA addition. The TUNEL-positive cells (those undergoing apoptosis) appear as green-fluorescent dots (examples indicated by the arrows in the inset). (C) Quantification of the TUNEL results presented in (B), represented as the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells. The columns represent the mean of two independent experiments done in duplicate. In each experiment, an average of 2000 cells was scored. Bars represent the standard deviation.

To study the protective effect of androgens on cell death in more detail, we specifically determined the extent of apoptosis under these conditions. First, nuclear morphology was assessed for features of apoptosis after DAPI staining and examination of the nuclei by fluorescence microscopy (data not shown). Apoptosis was further confirmed by the TUNEL assay, which detects cells undergoing DNA fragmentation. For both TG and TPA, androgen pretreatment caused a strong decrease in apoptosis incidence compared to the cells treated with TG or TPA alone, reaching 65% to 70% lower levels of apoptosis in the presence of R1881 for TG and at least 50% in TPA-treated cells (Figure 1, B and C). The low basal levels of apoptosis induced by the culturing conditions in the absence of TG or TPA were also inhibited by androgens, suggesting that it is due to the activation of a similar pathway (Figure 1C). These data demonstrate that androgens protect LNCaP cells from apoptosis induced by two different stimuli, TG and TPA. Interestingly, these two compounds activate independent pathways; whereas TG increases the levels of cytosolic calcium [39], TPA activates protein kinase C [40], pointing toward a general protective effect of androgens.

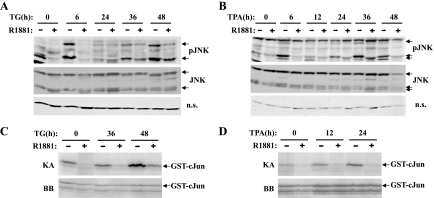

Androgens Decrease TG- and TPA-induced JNK Activation

Previous studies showed that activation of JNK has a decisive role in both TG- and TPA-induced apoptosis of LNCaP cells. Not only is there a good correlation between the onset of apoptosis and the sustained activation of JNK in these cells, but also specific inhibition of JNK activity blocked apoptosis induced by both agents [32,33]. We therefore assessed whether the molecular mechanisms underlying the antiapoptotic effect of R1881 involved alterations in the JNK pathway itself. To this end, LNCaP cells were treated with R1881 before the addition of TG or TPA, and JNK activation was analyzed at the time points that correlate with the onset of apoptosis. The use of an antibody that detects specifically the phosphorylated form of JNK allowed us to check JNK activation byWestern analysis. Consistent with previous data [32], in response to TG and TPA treatments JNK pathway was activated in a biphasic pattern, with an initial increase up to 6 hours for both agents and a second, more prolonged increase after 36 and 12 hours for TG and TPA, respectively (Figure 2, A and B). In contrast, in R1881-treated LNCaP cells, JNK activation was abrogated to near completion at 6 hours and significantly decreased at later time points, without any alteration in total JNK levels (Figure 2, A and B). In both cases, the decrease in JNK phosphorylation was accompanied by a decrease in JNK activity as shown in the solid-phase kinase assays using GST-c-Jun as a substrate (Figure 2, C and D).

Figure 2.

R1881 treatment inhibits TG- and TPA-induced JNK activation. LNCaP cells were plated in 10-cm plates at a density of 1 x 106 cells per plate and incubated in androgen-depleted low-serum media for 3 days before the treatment with R1881 (10-7 M) for 40 hours. After R1881 treatment, TG (100 nM) or TPA (5 ng/ml) was then added. At the indicated times the cells were harvested and whole-cell extracts prepared. Cell extracts (200 µg) were subjected to Western analysis, using either anti-phospho-JNK (pJNK) or total JNK (JNK) antibodies. (A, B) Western analysis of phosphorylated and total JNK in cell extracts from TG (A) or TPA (B) treatments. As a loading control, a nonspecific band that migrated at 40 kDa was used. (C, D) JNK activity demonstrated by solid-phase kinase assay (KA) using 200 µg of whole-cell extract from cultures treated with TG (C) and TPA (D). The lower panel (BB) shows the Coomassie blue staining of the gel for loading control. The arrows indicate the specific bands.

Taken together, these results indicate that the antiapoptotic action of androgens in the prostate cancer cell line LNCaP cells may be mediated through the inhibition of the JNK pathway.

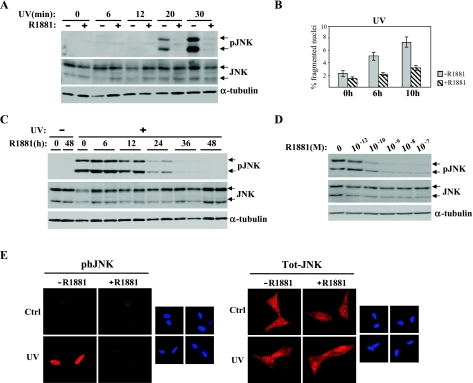

Androgens Inhibit UV-Induced Apoptosis of LNCaP Cells

To further study the role of R1881 in the regulation of JNK pathway and apoptosis in LNCaP cells, we assessed the effect of androgens on JNK activation and apoptosis induced by UV irradiation, a well-known activator of JNK, with concomitant apoptosis in different cell lines [14,41,42]. In LNCaP cells, UV irradiation induced strong activation of JNK, reaching maximal levels by 30 minutes after UV exposure. Pretreatment with R1881 before UV irradiation caused a dramatic block of UV-induced JNK phosphorylation (Figure 3A). Interestingly, although UV is a more potent activator of JNK than TG or TPA, the inhibition caused by R1881 treatment was stronger in UV-treated cells blocking JNK activation by >90%.

Figure 3.

R1881 inhibits UV-induced JNK activation and apoptosis. (A) LNCaP cells were plated at a density of 1 x 106 cells per plate on 10-cm plates. After the starvation period, the cells were either left untreated or treated with R1881 (10-7 M) for 40 hours before UV irradiation (2 J/cm2 for 5 seconds). At the indicated times after UV irradiation, the cells were harvested and whole-cell extracts were prepared. Extracts (50 µg) were subjected to Western analyses with total JNK (JNK)- and phosphorylated JNK (pJNK)-specific antibodies. Blots were also probed with an α-tubulin antiserum for loading control. (B) Quantification of apoptosis incidence in LNCaP cells 6 and 10 hours after UV exposure. The cells were grown on coverslips, either kept untreated or treated with R1881 for 40 hours before exposure to UV light. Apoptotic cells, indicated by fragmented nuclei, were scored after DAPI staining. The data shown are the mean of two independent experiments done in duplicate. An average of 2000 cells was scored in each experiment. (C) Time course of R1881 treatment of LNCaP cells before UV exposure. After UV irradiation, cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes and harvested, and whole-cell extracts were prepared. R1881-treated samples were done in duplicate. Extracts (50 µg) were resolved on SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western analysis with JNK and pJNK antisera. Blots were also probed with an α-tubulin antiserum for loading control. (D) LNCaP cells were treated for 40 hours with increasing concentrations of R1881 before UV irradiation. Thirty minutes after UV irradiation, whole-cell extracts were prepared and subjected to Western analysis as described above. (E) LNCaP cells plated onto coverslips were kept in charcoal-treated low-serum medium for 3 days. The cells were then either left untreated or treated with R1881 (10-7 M) for 40 hours and exposed to UV light as described above. After fixation with methanol, immunofluorescence analysis was carried out using pJNK and JNK antisera as described in Materials and Methods. Counterstaining with DAPI is shown in the smaller panels. The data presented are representative of two independent experiments done in duplicate.

We then assessed whether the inhibition of UV-induced JNK activation observed in R1881-treated LNCaP cells correlates with a decrease in apoptosis. Nuclear fragmentation analysis showed that apoptosis of LNCaP cells started 6 hours after UV irradiation (Figure 3B). In parallel with the observed inhibition of UV-induced JNK activation, androgen treatment also blocked UV-induced apoptosis (Figure 3B).

Androgen-dependent inhibition of JNK activation and concomitant apoptosis induced by UV supports our hypothesis of a general action of androgens on apoptosis in prostate cancer cells, regardless of the factor that triggers the apoptotic process. Consistent with this, the phosphatase inhibitor, okadaic acid, which causes apoptosis of LNCaP cells, also induces JNK activation. Both JNK activation and apoptosis were reduced by androgens (Ref. [43] and data not shown).

The simultaneous decrease of JNK activation and apoptosis induced by all four agents—TG, TPA, UV, and okadaic acid—by androgens suggests that JNK is the common juncture of all these pathways where androgens elicit their effect.

Androgens Inhibit JNK Activation in a Dose- and Time-Dependent Manner

To further analyze the R1881-dependent inhibition of JNK activation, a time course study was performed. LNCaP cells were treated with R1881 for increasing times and then irradiated with UV. In all cases, to allow maximal activation of JNK, the cells were incubated for 30 minutes after UV irradiation before being harvested. As shown in Figure 3C, R1881 treatment shorter than 12 hours did not cause any significant decrease in JNK activation upon UV irradiation, whereas 24-hour R1881 treatment blocked JNK phosphorylation by approximately 80%. This decrease became even more striking when the time of exposure to R1881 was increased, causing a nearly complete block of JNK activation after 48 hours treatment. This suppression of JNK phosphorylation was not due to a decrease in total JNK protein (Figure 3C). To our knowledge, this is the strongest inhibition of JNK activation described to date by a soluble agent.

We also assessed whether R1881-induced inhibition of UV-dependent JNK activation was dose dependent. Treatment of LNCaP cells with increasing concentrations of R1881 caused a progressive decrease in JNK activation with a nearly complete inhibition at 10-7 M (Figure 3D). In summary, our data indicate that androgens inhibit UV-induced JNK activation in both a dose- and a time-dependent manner in LNCaP cells.

Previous studies have demonstrated that another member of the nuclear receptor family, the GR, once activated by its ligand, blocks JNK activation by direct binding to inactive JNK, blocking its phosphorylation and simultaneously inducing nuclear translocation of inactive JNK [27,44,45]. Although the time required for the hormonal treatment to block JNK activation is significantly different (30 minutes for glucocorticoids and at least 36 hours for androgens), we assessed whether androgen treatment causes an alteration on the cellular distribution of JNK. To that end, we used confocal microscopy to analyze the localization of both phosphorylated and total JNK after UV irradiation in the presence or absence of R1881 in LNCaP cells. As is well established [15,46], UV irradiation induced JNK phosphorylation and its translocation to the nucleus (Figure 3E). Consistent with the Western analysis results presented above, androgen treatment of LNCaP cells blocked the nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated JNK (Figure 3E). In contrast, there was no significant alteration in total JNK levels or its cellular distribution in androgen-treated cells when compared with control cells (Figure 3E). These data, coupled to the significantly different time requirements for inhibition of JNK by glucocorticoids compared with androgens, indicate that androgen-dependent inhibition of JNK activation occurs through a different mechanism than that previously described for glucocorticoids.

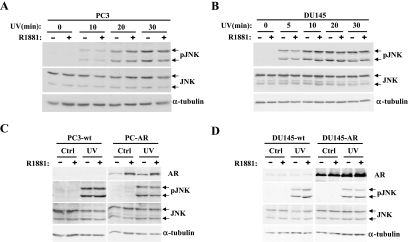

Androgen-Induced Block of JNK Activation Requires a Functional Androgen Receptor

That inhibition of JNK activation by androgens is dose- and time-dependent suggested a direct involvement of AR in this action. To verify the involvement of AR in this process, we first assessed the possible effect of R1881 on JNK activation in PC3 and DU145 cells, two prostate cancer cell lines that do not express functional AR [47,48]. PC3 and DU145 cells were either left untreated or pretreated with R1881 for 40 hours and were then exposed to UV irradiation and JNK activity was determined. As shown in Figure 4, A and B, in neither of these two cell lines did R1881 have an effect on UV-induced JNK activation. These data indicate that a functional AR signaling pathway is required for the androgen-induced inhibition of JNK activation. Surprisingly, stable reexpression of AR in both PC3 and DU145 cells did not restore the ability of androgens to inhibit JNK activation (Figure 4, C and D). This could be because expression of AR does not completely reestablish the normal androgen-signaling pathway and that other factors involved in androgen signaling may be missing in these cells. Consistent with this, a recent report [49] showed that both DU145 and PC3 cells do indeed express low levels of AR; however, in neither of them can androgen stimulate transcription of an AR-responsive reporter.

Figure 4.

R1881 treatment has no effect on the androgen-insensitive PC3 and DU145 cells. PC3 (A) and DU145 cells (B) were treated with R1881 (10-7 M) for 40 hours before exposure to UV (2 J/cm2 for 5 seconds). After UV induction, the cells were incubated at 37°C and harvested at the indicated times. Whole-cell lysates (75µg) were subjected to Western analysis using phospho-JNK (pJNK) and total JNK (JNK) antisera as described in Materials and Methods. Blots were also probed with an α-tubulin antiserum for loading control. (C) Wild-type PC3 cells (PC3-wt) and PC3 cells stably expressing AR (PC3-AR) were treated with R1881, irradiated with UV, and analyzed as in (A) with a harvest time of 30 minutes. (D) The same experiment as in (C) was performed with DU145-wt and DU145-AR cells.

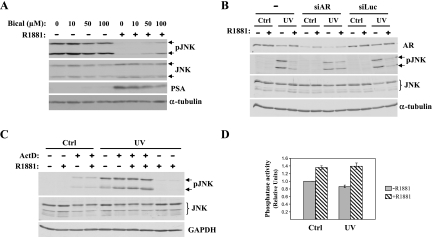

To further assess the possible involvement of AR in R1881-mediated inhibition of JNK, we used two different approaches to specifically inhibit AR-dependent action. We first used bicalutamide [50], a compound widely used as a specific antagonist of AR in LNCaP cells, as well as in the clinic [51,52]. LNCaP cells were treated with increasing concentrations of bicalutamide under conditions where JNK activation is inhibited by androgen treatment as presented above. The decrease in the AR-target gene PSA (prostate-specific antigen) confirmed the inhibition of AR-dependent transcription in response to bicalutamide treatment (Figure 5A). This decrease in PSA was accompanied by a reduction in androgen-induced inhibition of JNK activation (Figure 5A), suggesting that AR is involved in this process.

Figure 5.

R1881 inhibition of JNK activation requires AR-dependent transcriptional activation. (A) LNCaP cells were plated on 10-cm plates and incubated in low-serum media for 3 days. One hour before the addition of R1881 (10-8 M) the cells were treated with increasing concentrations of the androgen antagonist bicalutamide (Bical). After 40 hours of androgen treatment, the cells were UV irradiated and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes before being harvested. Whole-cell lysates (100 µg) were subjected to Western analysis for JNK expression (JNK), JNK activation (pJNK), and PSA expression. Blots were also probed with an α-tubulin antiserum for loading control. (B) LNCaP cells were plated on six multiwell plates and incubated in 2% charcoal-treated serum media for 2 days before their transfection with siAR. R1881 treatment was started 36 hours after siAR transfection, After 40 hours in the presence of R1881, the cells were UV irradiated and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes before being harvested. siRNA transfections were performed in triplicate and a pool of cells from three wells was used for protein extraction. Whole-cell lysates (75 µg) were subjected to Western analysis using AR, phospho-JNK (pJNK), and total JNK (JNK) antisera as described in Materials and Methods. Blots were also probed with an α-tubulin antiserum for loading control. (C) LNCaP cells incubated in androgen-depleted low serum medium for 3 days were then pretreated with ActD (1 µg/ml) for 1 h before the addition of R1881 (10-7 M). After 40 hours, the cells were exposed to UV (2 J/cm2 for 5 seconds) and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes before being harvested. Whole-cell extracts (50 µg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western analysis using pJNK and JNK antibodies. Blots were also probed with a GAPDH antiserum for loading control. (D) LNCaP cells were either kept untreated or treated with R1881 (10-7 M) for 40 hours before UV irradiation. Phosphatase activity in intact cells was measured by the amount of pNP released from pNPP as described in Material and Methods.

As a second approach to inhibit AR, we used siRNA to specifically knock down AR before R1881 treatment of LNCaP cells. We used a siRNA that was recently shown to be effective in knocking down AR expression in LNCaP cells [38]. As can be seen in Figure 5B, 4 days after siAR transfection AR levels were largely diminished compared to control cells (in both untransfected and siLuc transfected cells). The specific decrease in AR levels correlated with a block of R1881-dependent JNK inhibition. These data, together with the results obtained with the bicalutamide presented above (Figure 5A), show that AR is required for androgen-dependent inhibition of JNK activation.

Androgen Inhibition of JNK Activation Requires New RNA Synthesis

The long R1881 treatment period (40 hours) that is necessary to optimally block JNK activation and the involvement of AR in this process indicated that androgen action may require new gene expression. To assess this possibility, LNCaP cells were pretreated with the RNA synthesis inhibitor ActD before androgen treatment and the effect of R1881 on JNK activation was assessed by Western analysis as described above. As shown in Figure 5C, pretreatment of LNCaP cells with ActD blocked androgen-induced inhibition of JNK phosphorylation without affecting the levels of total JNK protein, indicating that R1881 inhibition of JNK activation requires new gene expression.

Because different signaling pathways can interact with each other, we next analyzed whether the effect of R1881 on JNK activity required other major signaling pathways. To that end, we first studied the possible involvement of the other major MAPK pathways. LNCaP cells were pretreated with either SB203580, an inhibitor of the p38 pathway, or PD98059, an inhibitor of the ERK pathway, before treatment with R1881. Neither inhibitor had any effect on androgen-induced inhibition of JNK phosphorylation (data not shown). Consistent with this, there was no significant increase in p38 or ERK phosphorylation upon androgen treatment (data not shown).

We next assessed the possible involvement of the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase (PI3K) pathway, which has been implicated in the survival of LNCaP cells under acute androgen deprivation [53]. We did not detect any increase in activated Akt levels in androgen-treated cells (data not shown). Moreover, wortmannin, an inhibitor of PI3K, had no effect on R1881 action on JNK activation (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that the inhibitory effect of R1881 on JNK activity does not require the activation of any of these related pathways.

We next assessed the known upstream components of the JNK pathway. MKK4 and MKK7 are two of the MKKs that are most frequently involved in JNK activation [15,54]. Analysis of UV-activated MKK4 and MKK7 levels in response to androgens revealed no significant effects (data not shown). These data suggest that the inhibitory action of androgens takes place at the JNK level itself.

It is known that JNK activation is not only regulated by its phosphorylation by upstream kinases of the pathway, but also by its dephosphorylation by phosphatases (for a review, see Ref. [16]). To assess whether there were any changes in phosphatase activity in response to androgens, we analyzed global phosphatase activity in LNCaP cells after UV irradiation in the presence or absence of R1881. There was a significant increase in phosphatase activity in R1881-treated cells when compared with their nontreated counterparts, both in nontreated cells and in UV-irradiated cells (Figure 5D). Supporting these results, the dephosphorylation rate of JNK upon ATP depletion is increased in the presence of androgens, suggesting that androgens facilitate JNK dephosphorylation (data not shown).

In summary, these data suggest that androgens increase the phosphatase activity in LNCaP cells, which leads to inactivation of JNK. Further studies are required to identify the phosphatase(s) that can account for R1881-dependent inhibition of JNK activation.

Discussion

The mechanisms by which androgens elicit their pro-proliferative and antiapoptotic effects in the normal prostate and in human prostate cancer cells are largely unknown. This knowledge is necessary for the development of new and more effective therapeutic strategies for prostate cancer treatment. Here, we have provided evidence that the antiapoptotic action of androgens in prostate cancer cells, at least in part, is due to inhibition of JNK signaling through a mechanism that requires AR-dependent new gene expression. The requirement of AR in this process was demonstrated not only by the loss of JNK activation and concomitant apoptosis induced by androgens, but also by the restoration of JNK activity both in the presence of the AR antagonist bicalutamide as well as by specific knockdown of AR by siRNA.

It is well known that the depletion of androgens induces apoptosis in the normal prostate as well as in prostate cancer in its beginning stages, causing rapid regression of the gland/tumor [2–4,55]. However, after some time, prostate cancer recurs in an androgen-independent form (reviewed in Refs. [5,7]). It is now believed that in this later stage, despite the low levels of androgens, AR remains activated (reviewed in Refs. [55–57]). This is supported by the fact that knocking down AR expression had a more pronounced effect on AR-induced transcription and cell growth/apoptosis than androgen depletion itself [58,59]. It is therefore important to know the molecular mechanisms of antiapoptotic action mediated by AR even in an androgen-depleted environment. Thus, our identification of the apoptotic JNK pathway as a target for AR action is significant in this regard. However, this specific action of AR cannot account for the prosurvival actions of androgens in normal cells that are not under stress, where there is no activation of the JNK pathway.

The role of JNK pathway activation in apoptosis is known to be highly context dependent [14]. The complexity of JNK signaling is influenced by several factors: the different and overlapping activities of JNK isoforms, the multitude of upstream activating kinases, the different scaffold molecules, and the variety of compartment-defined substrates [41,60,61]. We and others have demonstrated that JNK activation is required for apoptosis of prostate cancer cells in response to both TG and TPA [32,33]. The inhibition of JNK activation, either by expression of the JNK binding domain of JNK interacting protein-1 or by treatment with the JNK-specific inhibitor SP600125, caused a decrease in apoptosis, confirming the important role of the JNK pathway in this process [32,33].

Previous studies that focused on the role of AR-JNK pathway interactions in modulating apoptosis in LNCaP cells resulted in conflicting findings. Whereas in one study 2-methoxyestradiol-induced apoptosis is inhibited by androgens that correlated with a decrease in JNK activation [62], another study found that N-(4-hydroxyphenyl) retinamide-induced apoptosis was enhanced by androgens that correlated with activation of the JNK pathway [63]. Our data from all four inducers that we tested (TG, TPA, UV, and okadaic acid) support the results from the first study [62], suggesting that androgen treatment inhibits JNK activation and concomitant apoptosis in LNCaP cells regardless of the agent that triggers this apoptotic process. This places JNK at a key junction point for apoptosis in prostate cancer cells that is targeted by androgens. Consistent with JNK as a common focal point, we did not observe significant changes in the activity of the JNK upstream kinases, MKK4 and MKK7 (unpublished data). N-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)retinamide-induced apoptosis and its augmentation by androgens is a special case that may involve unique pathways that affect JNK signaling. Because our study, which was based on the reexpression of AR in DU145 and PC3 cells, was not enough to completely reestablish AR pathway in these two cell lines, further studies using other androgen-responsive prostate cancer cells similar to LNCaP cells will be useful to confirm this general inhibitory action of androgens.

The crosstalk between JNK and some other members of the nuclear receptor superfamily, but not AR, has previously been described [25,44,64,65]. For example, ligand-activated GR can physically interact with inactive JNK; this interaction inhibits JNK phosphorylation and induces its nuclear translocation [27,45,64]. These events occur rapidly in a manner that is independent of new gene transcription. In contrast to GR and other nuclear receptors tested so far [25,27,45], we have shown that inhibition of JNK phosphorylation by AR requires extended time (at least 36 hours), suggesting a mechanism of action that is different than for other nuclear receptors reported so far. This is supported by the fact that androgen-induced inhibition of JNK requires new gene transcription, which is not required for GR-dependent inhibition of JNK.

The participation of AR-dependent new gene expression, and therefore intermediate protein(s), in the inhibition of JNK activation by androgens suggested that other signaling pathways may also be involved in this crosstalk. However, ERK and p38 inhibitors had no effect on androgen-induced inhibition of JNK phosphorylation; consistently, there was no increase in the activity of these two pathways in response to androgen treatment, indicating that they are not involved in this process. Another important signaling pathway that could be relevant in this regard is the PI3K/protein kinase B pathway, which is critical for cell survival in many cell types, including prostate cancer cells (for a review, see Ref. [66]). However, we found no increase in Akt activation in response to androgen in LNCaP cells, and the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin did not have an effect on androgen-dependent inhibition of JNK activation (unpublished data); therefore, activation of PI3K/protein kinase B pathway is not involved in the inhibition of JNK phosphorylation by androgens in LNCaP cells. Although these results suggest that androgen-induced inhibition of JNK activation occurs by direct modulation of the JNK pathway, we cannot exclude the involvement of other signaling pathways that we have not yet analyzed.

Sustained reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation can trigger JNK activation through the inactivation of MAPK phosphatases (MKPs) [67] suggesting that inhibition of ROS accumulation could be responsible for the inhibition of JNK activation by androgens in LNCaP cells. However, the analysis of ROS levels in LNCaP cells showed that R1881 treatment induces an accumulation of ROS, consistent with previously published data [68], that is not inhibited under conditions where JNK activation is blocked by R1881 (data not shown).

Phosphatases are another group of proteins that could mediate the inhibitory effect of androgens on JNK activation. The increase in the phosphatase activity that we observed in the presence of androgens together with the faster dephosphorylation rate of JNK in androgen-treated cells suggests the presence of phosphatase(s) among the intermediate protein(s) involved in androgen-mediated inhibition of JNK activation. Supporting the possible involvement of phosphatases in regulating apoptosis in prostate cancer, previous work suggested that in human prostate tumors MKP-1 may inhibit apoptosis through the inhibition of the JNK pathway. These studies indicated that MKP-1 was overexpressed in preinvasive prostate cancer compared with normal prostate [69]. In addition, MKP-1 expression was inversely correlated with the enzymatic activity of JNK-1, but not that of ERK-1 [69]. Furthermore, in high-grade PIN lesions, MKP-1 expression was inversely correlated with their apoptotic potential [70]. Despite these interesting data with MKP-1, analyses of the expression of the different dual-specificity phosphatases that have been previously implicated in JNK dephosphorylation (DUSP1, DUSP8, and DUSP10) did not reveal any clear regulation by androgens that can account for the inhibition of UV-, TG-, or TPA-dependent JNK activation (unpublished data). However, because we demonstrated both an increase of phosphatase activity and a faster dephosphorylation of JNK in androgen-treated cells, it is possible that other member(s) of the rapidly growing DUSP family, or similar phosphatases, may be involved and further experiments are in progress to assess this possibility.

Other JNK-interacting proteins may be involved as well, such as GSTs that under normal conditions bind to and inhibit JNK [71,72]. Furthermore, overexpression of the scaffolding protein JIP1 can prevent JNK activity by sequestering JNK [33]. It has also been demonstrated that under certain conditions JIP proteins can also recruit DUSPs resulting in enhanced dephosphorylation and inactivation of JNK [73]. Taking these data into account, regulation of expression and/or activity of these proteins could be another possible mechanism that can account for the inhibitory action of androgens on JNK activity.

What is the significance of these results in human prostate cancer? The identification of JNK as a focal point for AR-dependent inhibition of apoptosis in prostate cancer cells suggests that it may be useful as a diagnostic or prognostic marker, as well as a new target for treatment. Consistent with this central role of JNK, a preliminary analysis suggests that JNK activation is downregulated with increasing grade of human prostate cancer (unpublished data). These findings are consistent with the data we present here suggesting that inhibition of JNK activation, perhaps through AR-dependent activation of specific phosphatase/s or other JNK interacting proteins, is linked to a significant decrease in apoptosis of prostate cancer cells. This could be the mechanism, at least in part, of how the apoptotic potential of advanced prostate cancers is inhibited where AR is known to be still activated. Therefore, these data suggest that increasing JNK activity in prostate cancer cells would reinstate their apoptotic potential and, consequently, may have clinical use for controlling disease progression.

Abbreviations

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- AR

androgen receptor

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- TPA

12-O-tetradecanoyl-13-phorbol-acetate

- TG

thapsigargin

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- MKP

MAPK phosphatase

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

Footnotes

This study was supported by funds from the Norwegian Research Council and Norwegian Cancer Society.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Debes JD, Tindall DJ. The role of androgens and the androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 2002;187:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denmeade SR, Isaacs JT. Development of prostate cancer treatment: the good news. Prostate. 2004;58:211–224. doi: 10.1002/pros.10360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyamoto H, Messing EM, Chang C. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: current status and future prospects. Prostate. 2004;61:332–353. doi: 10.1002/pros.20115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold JT, Isaacs JT. Mechanisms involved in the progression of androgen-independent prostate cancers: it is not only the cancer cell's fault. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2002;9:61–73. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0090061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heinlein CA, Chang C. Androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:276–308. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gleave M, Miyake H, Chi K. Beyond simple castration: targeting the molecular basis of treatment resistance in advanced prostate cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;56(Suppl 1):47–57. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKenzie S, Kyprianou N. Apoptosis evasion: the role of survival pathways in prostate cancer progression and therapeutic resistance. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97:18–32. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato S, Matsumoto T, Kawano H, Sato T, Takeyama K. Function of androgen receptor in gene regulations. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;89–90:627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dehm SM, Tindall DJ. Molecular regulation of androgen action in prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:333–344. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gregory CW, Hamil KG, Kim D, Hall SH, Pretlow TG, Mohler JL, French FS. Androgen receptor expression in androgen-independent prostate cancer is associated with increased expression of androgen-regulated genes. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5718–5724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, Baek SH, Chen R, Vessella R, Rosenfeld MG, Sawyers CL. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10:33–39. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohler JL, Gregory CW, Ford OH, III, Kim D, Weaver CM, Petrusz P, Wilson EM, French FS. The androgen axis in recurrent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:440–448. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1146-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Lin A. Role of JNK activation in apoptosis: a double-edged sword. Cell Res. 2005;15:36–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weston CR, Davis RJ. The JNK signal transduction pathway. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:14–21. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(01)00258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farooq A, Zhou MM. Structure and regulation of MAPK phosphatases. Cell Signal. 2004;16:769–779. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaulian E, Karin M. AP-1 as a regulator of cell life and death. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:E131–E136. doi: 10.1038/ncb0502-e131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saatcioglu F, Claret FX, Karin M. Negative transcriptional regulation by nuclear receptors. Semin Cancer Biol. 1994;5:347–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karin M, Chang L. AP-1-glucocorticoid receptor crosstalk taken to a higher level. J Endocrinol. 2001;169:447–451. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1690447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrlich P. Cross-talk between glucocorticoid receptor and AP-1. Oncogene. 2001;20:2465–2475. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato N, Sadar MD, Bruchovsky N, Saatcioglu F, Rennie PS, Sato S, Lange PH, Gleave ME. Androgenic induction of prostate-specific antigen gene is repressed by protein-protein interaction between the androgen receptor and AP-1/c-Jun in the human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17485–17494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frønsdal K, Engedal N, Slagsvold T, Saatcioglu F. CREB binding protein is a coactivator for the androgen receptor and mediates cross-talk with AP-1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31853–31859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aarnisalo P, Palvimo JJ, Janne OA. CREB-binding protein in androgen receptor-mediated signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2122–2127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konig H, Ponta H, Rahmsdorf HJ, Herrlich P. Interference between pathway-specific transcription factors: glucocorticoids antagonize phorbol ester-induced AP-1 activity without altering AP-1 site occupation in vivo. EMBO J. 1992;11:2241–2246. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caelles C, Gonzalez-Sancho JM, Munoz A. Nuclear hormone receptor antagonism with AP-1 by inhibition of the JNK pathway. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3351–3364. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caelles C, Bruna A, Morales M, Gonzalez-Sancho JM, Gonzalez MV, Jimenez B, Munoz A. Glucocorticoid receptor antagonism of AP-1 activity by inhibition of MAPK family. Ernst Schering Res Found Workshop. 2002:131–152. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-04660-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruna A, Nicolas M, Munoz A, Kyriakis JM, Caelles C. Glucocorticoid receptor-JNK interaction mediates inhibition of the JNK pathway by glucocorticoids. EMBO J. 2003;22:6035–6044. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Day ML, Zhao X, Wu S, Swanson PE, Humphrey PA. Phorbol ester-induced apoptosis is accompanied by NGFI-A and c-fos activation in androgen-sensitive prostate cancer cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:735–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young CY, Murtha PE, Zhang J. Tumor-promoting phorbol ester- induced cell death and gene expression in a human prostate adenocarcinoma cell line. Oncol Res. 1994;6:203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garzotto M, White-Jones M, Jiang Y, Ehleiter D, Liao WC, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Fuks Z, Kolesnick R. 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced apoptosis in LNCaP cells is mediated through ceramide synthase. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2260–2264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McConkey DJ, Greene G, Pettaway CA. Apoptosis resistance increases with metastatic potential in cells of the human LNCaP prostate carcinoma line. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5594–5599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engedal N, Korkmaz CG, Saatcioglu F. C-Jun N-terminal kinase is required for phorbol ester- and thapsigargin-induced apoptosis in the androgen responsive prostate cancer cell line LNCaP. Oncogene. 2002;21:1017–1027. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ikezoe T, Yang Y, Taguchi H, Koeffler HP. JNK interacting protein 1 (JIP-1) protects LNCaP prostate cancer cells from growth arrest and apoptosis mediated by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2017–2024. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murthy S, Marcelli M, Weigel NL. Stable expression of full length human androgen receptor in PC-3 prostate cancer cells enhances sensitivity to retinoic acid but not to 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Prostate. 2003;56:293–304. doi: 10.1002/pros.10261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nightingale J, Chaudhary KS, Abel PD, Stubbs AP, Romanska HM, Mitchell SE, Stamp GW, Lalani el-N. Ligand activation of the androgen receptor downregulates E-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion and promotes apoptosis of prostatic cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2003;5:347–361. doi: 10.1016/S1476-5586(03)80028-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korkmaz KS, Korkmaz CG, Pretlow TG, Saatcioglu F. Distinctly different gene structure of KLK4/KLK-L1/prostase/ARM1 compared with other members of the kallikrein family: intracellular localization, alternative cDNA forms, and regulation by multiple hormones. DNA Cell Biol. 2001;20:435–445. doi: 10.1089/104454901750361497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Negrao MR, Keating E, Faria A, Azevedo I, Martins MJ. Acute effect of tea, wine, beer, and polyphenols on ecto-alkaline phosphatase activity in human vascular smooth muscle cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:4982–4988. doi: 10.1021/jf060505u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rokhlin OW, Taghiyev AF, Bayer KU, Bumcrot D, Koteliansk VE, Glover RA, Cohen MB. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II plays an important role in prostate cancer cell survival. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:732–742. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.5.3975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Denmeade SR, Isaacs JT. The SERCA pump as a therapeutic target: making a “smart bomb” for prostate cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:14–22. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.1.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu WS, Heckman CA. The sevenfold way of PKC regulation. Cell Signal. 1998;10:529–542. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(98)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tournier C, Hess P, Yang DD, Xu J, Turner TK, Nimnual A, Bar-Sagi D, Jones SN, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. Requirement of JNK for stress-induced activation of the cytochrome c-mediated death pathway. Science. 2000;288:870–874. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5467.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu S, Loke HN, Rehemtulla A. Ultraviolet radiation-induced apoptosis is mediated by Daxx. Neoplasia. 2002;4:486–492. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kimura K, Markowski M, Bowen C, Gelmann EP. Androgen blocks apoptosis of hormone-dependent prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5611–5618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzalez MV, Gonzalez-Sancho JM, Caelles C, Munoz A, Jimenez B. Hormone-activated nuclear receptors inhibit the stimulation of the JNK and ERK signalling pathways in endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1999;459:272–276. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gonzalez MV, Jimenez B, Berciano MT, Gonzalez-Sancho JM, Caelles C, Lafarga M, Munoz A. Glucocorticoids antagonize AP-1 by inhibiting the activation/phosphorylation of JNK without affecting its subcellular distribution. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1199–1208. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cavigelli M, Dolfi F, Claret FX, Karin M. Induction of c-fos expression through JNK-mediated TCF/Elk-1 phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1995;14:5957–5964. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaighn ME, Narayan KS, Ohnuki Y, Lechner JF, Jones LW. Establishment and characterization of a human prostatic carcinoma cell line (PC-3) Invest Urol. 1979;17:16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stone KR, Mickey DD, Wunderli H, Mickey GH, Paulson DF. Isolation of a human prostate carcinoma cell line (DU 145) Int J Cancer. 1978;21:274–281. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910210305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alimirah F, Chen J, Basrawala Z, Xin H, Choubey D. DU-145 and PC-3 human prostate cancer cell lines express androgen receptor: implications for the androgen receptor functions and regulation. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2294–2300. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Furr BJ. The development of Casodex (bicalutamide): preclinical studies. Eur Urol. 1996;29(Suppl 2):83–95. doi: 10.1159/000473846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bao BY, Hu YC, Ting HJ, Lee YF. Androgen signaling is required for the vitamin D-mediated growth inhibition in human prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:3350–3360. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mantoni TS, Reid G, Garrett MD. Androgen receptor activity is inhibited in response to genotoxic agents in a p53-independent manner. Oncogene. 2006;25:3139–3149. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murillo H, Huang H, Schmidt LJ, Smith DI, Tindall DJ. Role of PI3K signaling in survival and progression of LNCaP prostate cancer cells to the androgen refractory state. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4795–4805. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.11.8467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nishina H, Katada T. The biological functions of JNKKs (MKK4/MKK7 knockout mice) In: Lin A, editor. The JNK signaling pathway. Georgetown, TX: Landes Bioscience/Eurekah.com; 2006. pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feldman BJ, Feldman D. The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat Rev. 2001;1:34–45. doi: 10.1038/35094009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Navarro D, Luzardo OP, Fernandez L, Chesa N, Diaz-Chico BN. Transition to androgen-independence in prostate cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;8:191–201. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(02)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Comstock CE, Knudsen KE. The complex role of AR signaling after cytotoxic insult: implications for cell-cycle-based chemotherapeutics. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1307–1313. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.11.4353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liao X, Tang S, Thrasher JB, Griebling TL, Li B. Small-interfering RNA-induced androgen receptor silencing leads to apoptotic cell death in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:505–515. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li TH, Zhao H, Peng Y, Beliakoff J, Brooks JD, Sun Z. A promoting role of androgen receptor in androgen-sensitive and -insensitive prostate cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2767–2776. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Waetzig V, Herdegen T. Context-specific inhibition of JNKs: overcoming the dilemma of protection and damage. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jaeschke A, Karasarides M, Ventura JJ, Ehrhardt A, Zhang C, Flavell RA, Shokat KM, Davis RJ. JNK2 is a positive regulator of the cJun transcription factor. Mol Cell. 2006;23:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shimada K, Nakamura M, Ishida E, Kishi M, Konishi N. Roles of p38- and c-jun NH2-terminal kinase-mediated pathways in 2-methoxyestradiol-induced p53 induction and apoptosis. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1067–1075. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shimada K, Nakamura M, Ishida E, Kishi M, Konishi N. Requirement of c-jun for testosterone-induced sensitization to N-(4-hydroxyphenyl) retinamide-induced apoptosis. Mol Carcinog. 2003;36:115–122. doi: 10.1002/mc.10107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Swantek JL, Cobb MH, Geppert TD. Jun N-terminal kinase/stressactivated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK) is required for lipopolysaccharide stimulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) translation: glucocorticoids inhibit TNF-alpha translation by blocking JNK/SAPK. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6274–6282. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hirasawa N, Sato Y, Fujita Y, Mue S, Ohuchi K. Inhibition by dexamethasone of antigen-induced c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation in rat basophilic leukemia cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:4939–4943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li L, Ittmann MM, Ayala G, Tsai MJ, Amato RJ, Wheeler TM, Miles BJ, Kadmon D, Thompson TC. The emerging role of the PI3-K-Akt pathway in prostate cancer progression. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005;8:108–118. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kamata H, Honda S, Maeda S, Chang L, Hirata H, Karin M. Reactive oxygen species promote TNFalpha-induced death and sustained JNK activation by inhibiting MAP kinase phosphatases. Cell. 2005;120:649–661. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pinthus JH, Bryskin I, Trachtenberg J, Lu JP, Singh G, Fridman E, Wilson BC. Androgen induces adaptation to oxidative stress in prostate cancer: implications for treatment with radiation therapy. Neoplasia. 2007;9:68–80. doi: 10.1593/neo.06739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Magi-Galluzzi C, Mishra R, Fiorentino M, Montironi R, Yao H, Capodieci P, Wishnow K, Kaplan I, Stork PJ, Loda M. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 1 is overexpressed in prostate cancers and is inversely related to apoptosis. Lab Invest. 1997;76:37–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Magi-Galluzzi C, Montironi R, Cangi MG, Wishnow K, Loda M. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and apoptosis in PIN. Virchows Arch. 1998;432:407–413. doi: 10.1007/s004280050184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Holley SL, Fryer AA, Haycock JW, Grubb SE, Strange RC, Hoban PR. Differential effects of glutathione S-transferase pi (GSTP1) haplotypes on cell proliferation and apoptosis. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2268–2273. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lo HW, Ali-Osman F. Genetic polymorphism and function of glutathione S-transferases in tumor drug resistance. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Willoughby EA, Perkins GR, Collins MK, Whitmarsh AJ. The JNK-interacting protein-1 scaffold protein targets MAPK phosphatase-7 to dephosphorylate JNK. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10731–10736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]