Abstract

Motivation: Trimeric autotransporter adhesins (TAAs), such as Yersinia YadA, Neisseria NadA, Moraxella UspAs, Haemophilus Hia and Bartonella BadA, are important pathogenicity factors of proteobacteria. Their high sequence diversity and distinct mosaic-like structure lead to difficulties in the annotation of their sequences. These stem from the large number of short repeats, the presence of compositionally unusual coiled-coils, fuzzy domain boundaries and regions of seemingly low sequence complexity.

Results: We have developed a workflow, named daTAA, for the accurate domain annotation of TAAs. Its core consists of manually curated alignments and of knowledge-based rules that enhance assignments made by sequence similarity. Compared to general domain annotation servers such as PFAM, daTAA captures more domains and provides more sensitive domain detection, as well as integrated and detailed coiled-coil assignments.

Availability: The daTAA server is freely accessible at http://toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/dataa

Contact: andrei.lupas@tuebingen.mpg.de

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Adherence to the host plays a key role in bacterial pathogenesis. Within the diverse group of proteins mediating adhesion, trimeric autotransporter adhesins (TAAs) form a recently discovered and rapidly growing family. They include many medically important pathogenicity factors, such as YadA from Yersinia enterocolitica, NadA from Neisseria meningitidis, UspA1 and UspA2 from Moraxella catarrhalis, Hia and Hsf from Haemophilus influenzae and BadA from Bartonella henselae (reviewed in Linke et al., 2006). TAAs are found mainly in α-, β- and γ-Proteobacteria (including their viruses and virulence plasmids). Additionally they occur in small numbers in δ- and ɛ-Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria (Synechococcus and Thermosynechococcus), Bacteroidetes (Chlorobium), Fusobacteria (Fusobacterium) and Clostridia (Desulfitobacterium; as an aside, we submit that this last organism is misclassified, since Clostridia are Gram-positive and thus lack an outer membrane, while autotransporters require an outer membrane for their biological activity). A fair number of TAAs are also found in marine metagenome sequences and are thus not assigned phylogenetically at present.

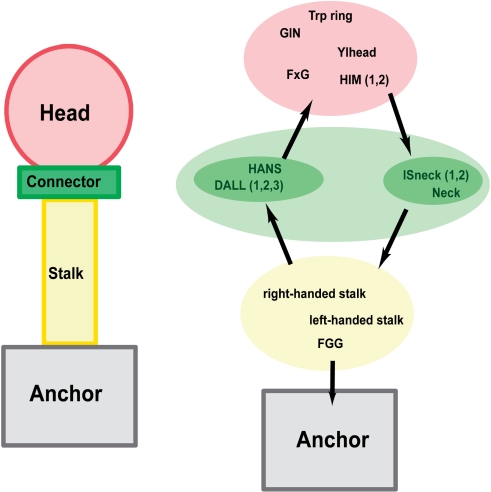

TAAs follow a general head-stalk-anchor organization (Hoiczyk et al., 2000), where the head mediates binding to the host, the stalk projects the head from the membrane and the anchor provides the pore for autotransport and attaches the protein to the bacterial surface after export is complete (Fig. 1). Only the anchor domain is homologous in all TAAs and provides the defining feature of this family. The domains forming the heads and stalks belong to several analogous types and usually occur in modular and highly repetitive fashion. In some TAAs, head and stalk domains alternate in the sequence, indicating a more complicated architecture. So far only a small number of TAA fragments have been solved by X-ray crystallography; these are the complete head of YadA (Nummelin et al., 2004) and two fragments of Hia, comprising part of the head (Yeo et al., 2004) and the complete membrane anchor (Meng et al., 2006).

Fig. 1.

Schematic architecture or TAAs and organization of their domains. The names of three domain types, Ylhead, HIM and ISneck, stand for—in order—YadA-like head, head insert motif and insertion sequence neck. Other abbreviated domain names (GIN, FxG, HANS, DALL and FGG) come from prominent residue patterns in those domains.

No systematic study of the domain composition of TAAs is available and most of the constituent domains have not been captured by general domain databases, such as PFAM (Finn et al., 2006). Several reasons may account for this: (i) the large number of internal repeats, only few of which occur in ungapped arrays, present significant problems for automated domain predictors and repeat detection algorithms, (ii) the usually short length and high sequence divergence of TAA domains makes their detection by sequence comparison programs difficult, (iii) the compositional bias leads to the frequent but erroneous identification of domains as low-complexity regions and (iv) the unusual periodicity and residue distribution of many coiled-coil segments precludes their detection by software built on heptad repeats and canonical scoring matrices.

In this study we present a workflow that addresses some of the issues above. We provide manually curated definitions for recurrent domains of TAAs, adjust the cutoff thresholds for the prediction of coiled-coil segments and offer an annotation of their properties. Our server provides a graphical, interactive summary of the annotation results.

2 METHODS

To identify TAA sequences, searches were made at the National Center for Bioinformatics Information (NCBI) using BLAST and PSI-BLAST [www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/Blast.cgi; (Altschul et al., 1990, 1997)] on the non-redundant database (nr) and in the MPI Toolkit (Biegert et al., 2006) using HHPred (Soding, 2005) on the Protein Data Bank filtered at 70% sequence identity (pdb70). Sequences were extracted using the Entrez service (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Entrez/) and aligned in MACAW (Schuler et al., 1991) and MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004). Domain boundaries were defined iteratively by sequence conservation and context. Coiled-coils were predicted using COILS (Lupas et al., 1991) and Marcoil (Delorenzi and Speed, 2002). Profile Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) were generated from multiple alignments of individual domains using HMMER (hmmer.janelia.org).

Annotation by the domain annotation of TAAs (daTAA) server is a multi step process. First, the sequence is analyzed for the presence of a membrane anchor. This domain is readily detectable and represents a reliable marker for whether a protein is a TAA. If this is not found, the server returns a message informing the user that the sequence may not be a TAA. If the user has knowledge that the sequence is a TAA fragment, (s)he can select a check-box on the submission page that the sequence should be analyzed anyway. This step was introduced because our domain definitions are calibrated on TAAs and may lead to occasional false-positive identifications when used on other proteins.

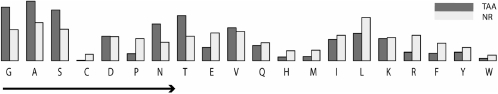

Second, the sequence is screened for coiled-coil regions using Marcoil, with a cutoff of 0.05. Then, HMMER is used to detect the presence of individual domains at a significance of 1e-3 per individual match; this cutoff was chosen because it allowed the identification of all manually annotated domains in a reference file of phylogenetically representative TAAs and produced no recognizable false positives. At more relaxed cutoffs, TAA domains start yielding overlapping predictions. We attribute this primarily to the biased residue composition of TAAs, which results in occasionally striking sequence similarity between structurally unrelated domains. Residues with small side chains, including all three smallest residues Gly, Ala and Ser, are significantly overrepresented as compared to the non-redundant database (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Frequencies of amino acids in TAAs compared to the non-redundant database. The arrow denotes increasing side-chain size. The numbers for the graph are: G (nr—7.0%, TAA—12.2%), A (8.6%, 13.5%), S (7.1%, 11.4%), C (1.4%, 0%), D (5.3%, 5.5%), P (5.0%, 1.5%), N (4.1%, 8.3%), T (5.5%, 10.2%), E (6.2%, 2.9%), V (6.6%, 7.4%), Q (4.1%, 3.3%), H (2.2%, 0.8%), M (2.3%, 0.9%), I (5.7%, 4.8%), L (9.8%, 6.1%), K (5.2%, 5.0%), R (5.7%, 1.9%), F (3.9%, 1.6%), Y (2.9%, 1.9%) and W (1.2%, 0.4%).

After these assignments, sequence motifs are identified using a set of specific, knowledge-based rules:

after their detection by a Hidden Markov Model, YadA-like head (Ylhead) repeats predicted in close proximity (20 residues or less) are merged and individual repeats are parsed using a regular expression; this expression reflects the five hydrophobic residues ending in glycine, which form the inner β-strand of the repeat

polar core motifs in coiled-coil regions predicted by Marcoil are identified by regular expressions

the regions separating either one of Trp-ring, DALL, HANS, FGG or coiled-coil domains from the preceding necks are assigned as coiled-coils in the absence of a Marcoil signal, provided they are 21 residues or less and no other domain is predicted in between; the same is true for regions separating FGG from coiled-coil segments

predicted coiled-coil segments are merged if they are separated by no more than 21 residues and no other domain is predicted in between

Except for the regular expressions, rules are specified in a text file that is parsed by the server for each run, so it is easy to add new rules and modify existing ones without altering the source code.

We chose PFAM as a reference for testing the performance of daTAA, because it contains the largest number of annotated TAA domains and also uses HMMER for domain assignments. For the comparison we considered only TAA domain definitions from PFAM-A: HIM, Hep_Hag, YadA, X_fast-SP_rel and DUF1079. Similarly, the daTAA annotation did not include domains in the beta database, which are still undergoing refinement. Assignment was done through the web interface of both servers. We only considered PFAM hits that were within the gathering threshold.

The performance of the servers was compared against all TAA sequences that had been deposited since the last daTAA update on June 30th, 2007, and had <70% sequence identity to previously deposited sequences. The set contained nine proteins with 8360 residues total, ranging in length from 212 to 2039 residues. For reference, the server predictions were also compared to a manual annotation obtained using the software tools COILS, MACAW and BLAST. In revision, a second set of nine proteins (13 695 residues total, ranging in length from 340 to 5035 residues), which had become available since submission of the manuscript, was analyzed in the same way. The manual annotation files for both sets are available as Supplementary Material.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Domains and motifs of Trimeric Autotransporter Adhesins

The building blocks of TAAs can be viewed in two ways: by their domain structure or by their sequence motifs. Repetitive domains usually contain characteristic sequence motifs in multiple copies often at regular intervals, while non-repetitive domains contain sequence motifs in single copy. The repetitive domains are the YadA-like head domains (Ylhead) and the coiled-coil segments of the stalks; all other domains currently captured in daTAA are non-repetitive.

The Ylhead domain is a trimer of single-stranded, left-handed β-helices, in which each structural repeat is formed by an outer and an inner β-strand, running perpendicularly to the fiber axis. The inner strands carry a highly conserved pattern of five alternating small and large hydrophobic residues, ending with an invariant glycine. This pattern has been recognized before (Hoiczyk et al., 2000; Tahir et al., 2000) and named NSVAIG-S; we use it to refine the repeat assignments in Ylhead domains as described in the Methods.

The coiled-coil segments of the stalks form right-handed or left-handed supercoils; in some stalks, segments of both kinds are combined. Right-handed segments are primarily built on repeats of 15 residues (pentadecads) arranged over four helical turns (3.75 residues per turn), but may show a number of other periodicities, all ranging between 3.7 and 3.83 residues per turn (for a structural interpretation of these periodicities, see Lupas and Gruber, 2005). Irrespective of the detailed periodicity, the repeats of right-handed coiled-coils in TAAs contain a prominent YxD motif starting five residues before the C-terminal end, with x usually threonine.

Left-handed coiled-coil segments are built on the usual repeats of seven residues (heptads) arranged over two helical turns (3.5 residues per turn). Occasionally, these repeats are interrupted by insertions of four residues (stammers), which straighten out the supercoil. The segments are conspicuous for an unusually high proportion of polar residues in their hydrophobic core. The most frequent patterns are those with one hydrophilic core residue per heptad: [VI]xxNT and LxxTN, but there are also several conspicuous ones in which both core residues are hydrophilic: NxxQD, SxxNT, QxxH and QxxD. These patterns are used to annotate in greater detail the coiled-coil regions predicted by Marcoil.

The non-repetitive domains of TAAs also contain prominent sequence motifs, but, in contrast to repetitive domains, these are not used for annotation. They are however often used in the name denoting the domain. Thus, the HANS domain is named for a prominent His-Ala-Asn-Ser pattern and DALLs for their common usage of Asp-Ala-Leu-Leu.

The domains annotated in daTAA are summarized in Table 1, arranged by class: signal peptide, heads, stalks, connectors and anchor. The ends of domains are either coiled-coils or β-helices, and connectors are defined as the domains that allow for the transition from one type of structure to the other. The table includes the autotransporter signal peptide, which is a highly conserved signal sequence among many autotransporters, even though this is not a domain in the stricter sense.

Table 1.

Annotated domains of TAAs, divided into functional classes. Where the structure of a domain is known, the Protein Data Bank accession code is given in square brackets

| Domain name | Structure | Prediction | PFAM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class: signal peptide | |||

| Autotransporter signal peptide | – | HMMER | – |

| Class: head | |||

| Ylhead | Beta-solenoid [1p9h] | HMMER/rules | Hep_Hag |

| HIM1, HIM2a | Insert within last Ylhead repeat before the neck | HMMER | – |

| Trp-ring | Beta-meander [1s7m] | HMMER | – |

| GIN | Beta-prism [1s7m] | HMMER | – |

| FxG | Unknown | HMMER | X_fast-SP-rel |

| Class: stalk | |||

| Right-handed stalks | Right handed CC | HMMER | – |

| Left-handed stalks | Left-handed coiled coil | Marcoil/rules | DUF1079b |

| FGG | Coiled-coil variant | HMMER/rules | – |

| Class: connector | |||

| Neck | Loop [1p9h] | HMMER | HIM |

| HANS | Unknown | HMMER/rules | – |

| DALL1, 2, 3 | Unknown | HMMER | – |

| ISneck1 | Neck with an inserted domain [1s7m] | HMMER | – |

| ISneck2a | Neck with an short insertion | HMMER | - (HIM)c |

| Class: anchor | |||

| Membrane anchor | Beta-barrel occluded by CC | HMMER | YadA |

aDUF1079 is a motif in the left-handed stalks of Moraxella UspA1 and UspA2.

bThese domains were added as a result of the manual benchmark annotation and were not used for benchmarking.

cPFAM HIM definition annotates only first half of this motif.

Domain arrangements in TAAs are not arbitrary, but follow certain rules. Some rules are obvious, such as the fact that signal sequences always occur at the N-terminus and the membrane anchor at the C-terminus (although a very small number of anchors are extended C-terminally by a coiled-coil). The reasons for a fair number of rules are however unclear to us at present. Thus, right-handed stalks only occur between the last neck sequence and the membrane anchor; Ylhead repeats always lead into a neck-like sequence, followed by a coiled-coil; DALLs are always followed by a neck; HANS always leads into Ylhead repeats. We note that these rules could be used for predictive purposes, although we currently do not do so.

3.2 Comparison of daTAA performance to PFAM

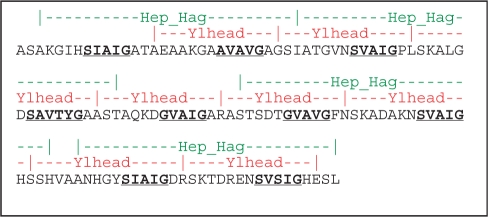

In order to evaluate daTAA annotations, we did a three-way comparison between daTAA, PFAM and manual annotation on a test set of recently deposited TAA sequences, as described in the Methods (Fig. 3). The coverage achieved by daTAA was 50%, against 28% obtained by PFAM and 56% obtained manually. The three domain types present in both daTAA and PFAM (Table 1; Ylhead = Hep_Hag repeat; neck = HIM motif; membrane anchor = YadA family) accounted for one-third of total residues (Table 2); DUF1079 was not considered as it only occurs in Moraxella UspAs, none of which was present in our test set. daTAA predicted all three types accurately: it only missed three variant necks and a small number of divergent Ylhead repeats, and overpredicted one Ylhead repeat in a segment identified by manual annotation as a new motif (HIM2). Although PFAM also performed very well, considering that it is a general domain annotation system, it had issues with both domain recognition and domain boundary definitions. Thus, it failed to identify one-third of the anchor domains and assigned the others in a shortened form, omitting part of the coiled-coil that forms the N-terminal third of this domain. Its performance on neck sequences was mixed: it did identify two of the three variant necks (only partly, however, and without recognizing that they were disrupted by longer insertions), but it overpredicted two additional necks. Finally, it predicted the regions of Ylhead repeats well, but not the repeats themselves, as its profile includes two repeats and does not coincide with the ends of the constituent β-strands (Fig. 4).

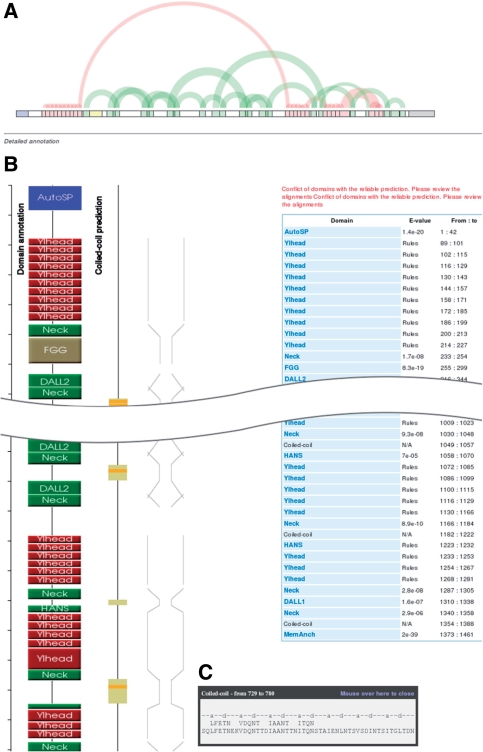

Fig. 3.

Details of daTAA and PFAM performance in comparison with manual annotation. The two sets of sequences are as described in the Methods. In each group, the first box denotes the PFAM annotation, the second daTAA and the third the manual annotation. Matches are colored according to their functional class as autotransporter signal peptide: blue, heads: red, connectors: green, stalks: yellow, anchor: grey. Set A. 1. gi|153095004| Mannheimia haemolytica PHL213 2. gi|149190224| Vibrio shilonii AK1 3. gi|154149446| Campylobacter hominis ATCC BAA-381 4. gi|153834639| Vibrio harvei HY01 5. gi|153093295| Mannheimia haemolytica PHL213 6. gi|150380584| Shewanella sediminis HAW-EB3 7. gi|148827620| Haemophilus influenzae PittGG 8. gi|154149537| Campylobacter hominis ATCC BAA-381 9. gi|149909020| Moritella sp. PE36 Set B. 1. gi|78061293| Burkholderia sp. 383 2. gi|161017094| Bartonella tribocorum CIP 105476 3. gi|161505469| Salmonella enterica subsp. arizonae 4. gi|156124985| Acinetobacter venetianus 5. gi|157145682| Citrobacter koseri ATCC BAA895 6. gi|155199120| Escherichia coli 7. gi|86750771| Rhodopseudomonas palustris HaA2 8. gi|85709253| Erythrobacter sp. NAP1 9. gi|162429157| Methylobacterium nodulans ORS 2060.

Table 2.

Coverage of annotation against total number of residues in the testing sets

| SET A | SET B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| daTAA (%) | PFAM (%) | manual (%) | daTAA (%) | PFAM (%) | manual (%) | |

| Domains common for PFAM and daTAA | ||||||

| Ylhead | 18 | 17 | 20 | 13 | 12 | 14 |

| Neck | 4 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 11 | 10 |

| MemAnch | 10 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 6 |

| FxG | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Domains not present in PFAM | 13 | – | 18 | 27 | – | 36 |

| Coiled coils | 5 | – | 3 | 11 | – | 25 |

| Total | 50 | 28 | 56 | 66 | 26 | 92 |

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the annotation of consecutive repeats in the YadA head. The first line (green) denotes the PFAM annotation, the second line (red) daTAA. The third line shows the sequence of the YadA head, with the conserved SVAIG motifs bold and underlined.

Domains only present in daTAA accounted for about a quarter of total residues (Table 2). daTAA annotation for these domains agreed closely with the manual annotation, except in two points: daTAA did not recognize any of the seven Trp-ring domains, occurring in two proteins, and manual annotation missed four FxG domains, all from one protein. We had noted before that Trp-ring domains are exceedingly divergent, with many pairwise identities in the ‘midnight zone’ under 15%. In order to preserve selectivity, we had therefore built the profile from a focused set of Trp-ring domain sequences. Clearly, these were too different from the ones in our test proteins to allow their detection. In response to this issue, we have generated several profiles of Trp-ring domains and a significant match to any of these will lead to a Trp-ring prediction by daTAA. Surprisingly, daTAA also predicted four FxG domains that had been missed in the manual annotation due to oversight, but which were readily recognizable as FxG domains. This highlights one important advantage of daTAA: automated servers do not make mistakes of oversight.

In revision, we added a second test set to the paper, referred to as Set B in Table 2 and Figure 3. This set was as large as the first and confirmed the results obtained previously, with a slightly better performance of daTAA relative to PFAM. Strikingly, manual annotation was relatively much better on this set, due mainly to sequence 1, which contained over 1900 residues of a very unusual coiled-coil. This coiled-coil is built on the basic repeating unit ITSLSTSTSTGLSSANSS, consisting of a hendecad plus a heptad and containing almost 50% serine. This coiled-coil could be recognized in the manual annotation due to almost two decades of experience with coiled-coils, but was outside the range of automated methods, even when supplemented with rules.

3.3 The daTAA server

The daTAA workflow was implemented as a web service within the MPI Toolkit (http://toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/dataa). The server provides the customary tabs for a front page, a browsing page and a search page. The front page gives a brief description of TAAs and explains the features that users will encounter when browsing the system or submitting sequences for annotation. The browsing page provides a list of the TAA domains captured by daTAA, each hyperlinked to its own page with an image of the domain structure (where known), a plot of average side-chain size and hydrophobicity, the phylogenetic spectrum and an option to show the multiple alignment from which the HMM was computed. The search page, finally, provides an input box for submitting sequences to the server.

After a sequence has been annotated, the server returns a results page with a summary of the outcome (Fig. 5). The top of the page contains an overview, which gives users a quick insight into the repeat structure of the query. Following this are four representations running from top to bottom. Three, from left to right, show graphically the location of daTAA domains in the sequence, coiled-coil predictions by Marcoil and a schematic of the anticipated fiber diameter. The fourth, furthest to the right, is a table listing the domains, their E-values and their residue numbers. Users can mouse over the domain boxes to call a tooltip, which shows the alignment to the HMM consensus in the case of domains (except where these are assigned by rules) or the heptad register in the case of coiled-coils. For coiled-coils, the tooltip also shows polar core motifs above the sequence. Users can click on domain boxes, or on the domain names in the table, in order to access the domain description pages. At the bottom of the results page, users are provided with a form allowing them to forward by a single click the first 100 residues of their protein to the SignalP server at the Technical University of Denmark. We introduced this feature in order to help users check whether their sequence may be incomplete, since many chromosomal TAA genes are known to be disrupted (Hoiczyk et al., 2000).

Fig. 5.

Screenshot of the daTAA results page. (A) Overview of repetitive domains. The graph is obtained by an implementation of a method for the visualization of repeats in strings (Wattenberg, 2002). (B) Picture with domain bubbles, coiled-coil prediction and schematic representation of the anticipated fiber width. (C) Tooltip with a Marcoil coiled-coil prediction and polar core motifs.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The unusual domain structure of trimeric autotransporters makes their automated annotation challenging. We have addressed this problem with a workflow built on profile HMMs, coiled-coil prediction, regular-expression patterns and knowledge-based rules. The result, daTAA, specifically addresses the issues arising from the short length, strong sequence divergence, unusual amino acid composition and combinatorial occurrence of TAA domains. daTAA provides considerably wider and more accurate coverage than a general annotation server and compares favorably with manual annotation. In future, daTAA will be extended to other classes of prokaryotic surface proteins with similar properties, such as single-chain autotransporters and the adhesins of Gram-positive bacteria. The daTAA server is public and its graphical user interface will hopefully provide experimental biologists with an intuitive access.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors would like to thank Dirk Linke and Marcin Grynberg for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the German Science Foundation (FOR449/LU1165 and SFB766/B4) and by institutional funds from the Max Planck Society.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Altschul SF, et al. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegert A, et al. The MPI Bioinformatics Toolkit for protein sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W335–W339. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorenzi M, Speed T. An HMM model for coiled-coil domains and a comparison with PSSM-based predictions. 2002;18:617–625. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.4.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, et al. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D247–D251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoiczyk E, et al. Structure and sequence analysis of Yersinia YadA and Moraxella UspAs reveal a novel class of adhesins. EMBO J. 2000;19:5989–5999. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.22.5989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke D, et al. Trimeric autotransporter adhesins: variable structure, common function. Trends Microbiol. 2006;14:264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas A, et al. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science. 1991;252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas AN, Gruber M. The structure of alpha-helical coiled coils. Adv. Protein Chem. 2005;70:37–78. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng G, et al. Structure of the outer membrane translocator domain of the Haemophilus influenzae Hia trimeric autotransporter. EMBO J. 2006;25:2297–2304. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nummelin H, et al. The Yersinia adhesin YadA collagen-binding domain structure is a novel left-handed parallel beta-roll. EMBO J. 2004;23:701–711. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler GD, et al. A workbench for multiple alignment construction and analysis. Proteins. 1991;9:180–190. doi: 10.1002/prot.340090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soding J. Protein homology detection by HMM-HMM comparison. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:951–960. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir YE, et al. Functional mapping of the Yersinia enterocolitica adhesin YadA. Identification Of eight NSVAIG - S motifs in the amino-terminal half of the protein involved in collagen binding. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;37:192–206. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattenberg M. Arc Diagrams: Visualizing Structure in Strings. Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Information Visualization. 2002. IEEE Computer Society.

- Yeo HJ, et al. Structural basis for host recognition by the Haemophilus influenzae Hia autotransporter. EMBO J. 2004;23:1245–1256. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.