Abstract

The solution structure of the protein disulfide oxidoreductase Mj0307 in the reduced form has been solved by nuclear magnetic resonance. The secondary and tertiary structure of this protein from the archaebacterium Methanococcus jannaschii is similar to the structures that have been solved for the glutaredoxin proteins from Escherichia coli, although Mj0307 also shows features that are characteristic of thioredoxin proteins. Some aspects of Mj0307's unique behavior can be explained by comparing structure-based sequence alignments with mesophilic bacterial and eukaryotic glutaredoxin and thioredoxin proteins. It is proposed that Mj0307, and similar archaebacterial proteins, may be most closely related to the mesophilic bacterial NrdH proteins. Together these proteins may form a unique subgroup within the family of protein disulfide oxidoreductases.

Keywords: Protein oxidoreductase, NMR structure, thioredoxin homolog, thermophile

The regulation of protein disulfide bond formation and reduction is critical not only to protein structure, but it is also an effective electron transport mechanism for cellular processes ranging from ribonucleotide reduction to coordination of light and dark photosynthetic reactions (Holmgren 1989; Schurmann 1995; Prinz et al. 1997; Gilbert 1998). This wide range of protein disulfide bond activity is accomplished primarily by the protein disulfide oxidoreductases. All the members of this large family of proteins share a common structural fold, which contains an active site tetrapeptide sequence CXXC (Martin 1995). The active site cystine residues are capable of reversibly forming disulfide bonds that provide the redox character of these proteins. The common structural fold is composed of a βαβαββα secondary structure pattern, which has been termed the "thioredoxin fold."

Thioredoxin (Trx) was the first member of the protein disulfide oxidoreductase family to be identified (Laurent et al. 1964). Glutaredoxins (Grx) were identified a decade later in Trx-deficient Escherichia coli (Holmgren 1976). Together, the biochemical and structural properties of Trx and Grx proteins have been extensively studied. Functionally, these proteins are distinguished by their reducing agents and substrates. Grx proteins are reduced by glutathione and glutaredoxin reductase, whereas Trx proteins are reduced by thioredoxin reductase (Trr). Furthermore, Trx proteins act more as general protein disulfide reductases, and Grx proteins display a reductive preference for glutathione mixed disulfide substrates (Berardi et al. 1998). Structurally, the bacterial and T4 Grx proteins contain only the minimal βαβαββα secondary structural elements of the thioredoxin fold, whereas several eukaryotic Grx proteins possess additional helices at the N and C termini (i.e., a αβαβαββαα secondary structure pattern). Trx proteins, however, have a βαβαβαββα secondary structure pattern that has been conserved in both bacterial and eukaryotic organisms.

Other well-studied members of the protein disulfide oxidoreductases include the bacterial Dsb proteins and eukaryotic protein disulfide isomerases (PDI). These proteins are quite different from the Trx and Grx proteins. Although they incorporate a thioredoxin fold domain, they have much longer amino acid sequences and possess additional structural domains (Martin et al. 1993; Kemmink et al. 1997; McCarthy et al. 2000). The Dsb and PDI proteins appear to be essential for promoting proper protein folding through disulfide bond shuffling (Bardwell et al. 1993; Gilbert 1998).

There are several other proteins with disulfide oxidoreductase activity that do not fit into any of the well-established subgroups. An example of these unclassified disulfide oxidoreductases is the NrdH group of proteins. These were first isolated from Lactococcus lactis and nearly identical homologs have been identified in E. coli and Salmonella typhimurium (Jordan et al. 1996, 1997). Despite the similarity to Grx proteins in both size and predicted secondary structure, the NrdH proteins are incapable of binding glutathione but interact well with Trr. This blend of Trx and Grx attributes, in addition to a limited knowledge of in vivo function, has made it difficult to classify or define the position of NrdH proteins in the disulfide oxidoreductase family.

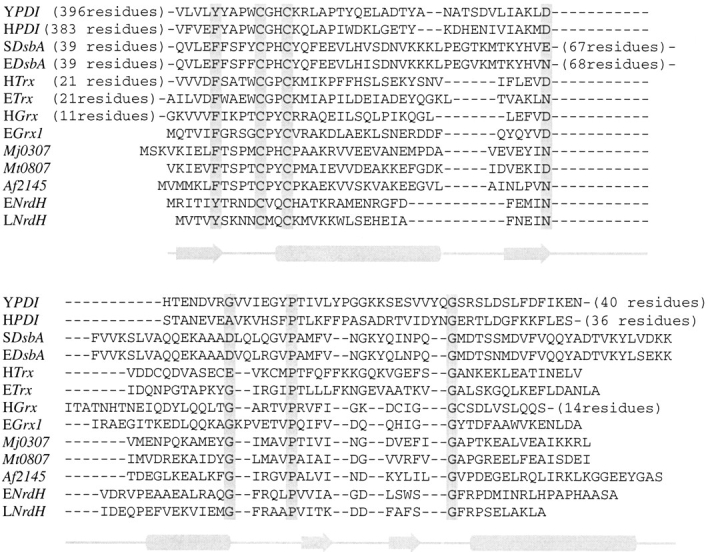

The advent of whole genome sequencing data has facilitated the search for novel protein disulfide oxidoreductases. Far less is known about these proteins in archaebacteria than in the prokaryotes and eukaryotes. McFarlan and co-workers identified a small disulfide oxidoreductase protein (Mt0807) from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum that was similar to Grx in its sequence but displayed behavior inconsistent with either the Grx or the Trx proteins (McFarlan et al. 1992). Open reading frames from the archaebacterial genomes of Methanococcus jannaschii (gene Mj0307) and Archaeoglobus fulgidus (gene Af2145) contain proteins that are homologous with Mt0807 (51% and 34% sequence identity for Mj0307 and Af2145, respectively; see Fig. 1 ▶ for a sequence comparison of these proteins and other protein disulfide oxidoreductases). Lee and co-workers have reported that Mj0307 also does not display glutathione-dependent behavior but does weakly interact with E. coli Trr (Lee et al. 2000).

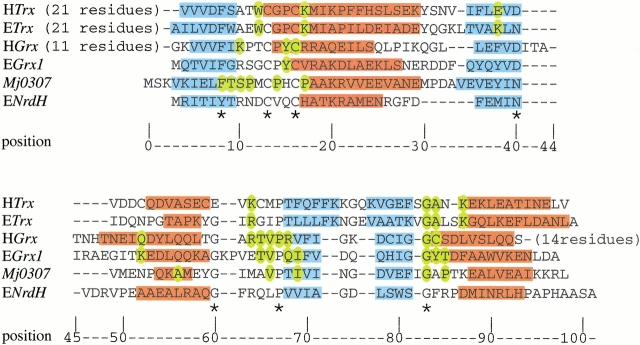

Fig. 1.

Sequence alignments of several protein disulfide oxidoreductases. The approximate locations of secondary structural elements in the minimal thioredoxin fold are displayed below the alignment. The alignment is based on highly conserved residues or residue types (filled boxes) as well as secondary structures based on prediction or from published crystal and NMR data. The identities of aligned proteins are as follows: S. cervisae PDI b domain (YPDI), H. sapiens PDI b domain (HPDI), S. typhimurium DsbA (SDsbA), E. coli DsbA (EDsbA), H. sapiens Trx (HTrx), E. coli Trx (ETrx), H. sapiens Grx (HGrx), E. coli Grx-1 (EGrx1), Mj0307, Mt0807, Af2145, E. coli NrdH (ENrdH), and L. lactis NrdH (LNrdH).

Given the importance of protein disulfide oxidoreductases in all organisms, it is of considerable interest to better understand the structure and function of these novel archaebacterial protein disulfide oxidoreductases. To this end, we report the solution structure of Mj0307 in its reduced state. Using these structural data, in combination with sequence alignments, we are able to explain several functional features of Mj0307. The data also suggest that these archaebacterial proteins and the mesophilic bacterial NrdH proteins may belong to the same subgroup within the protein disulfide oxidoreductase family.

Results

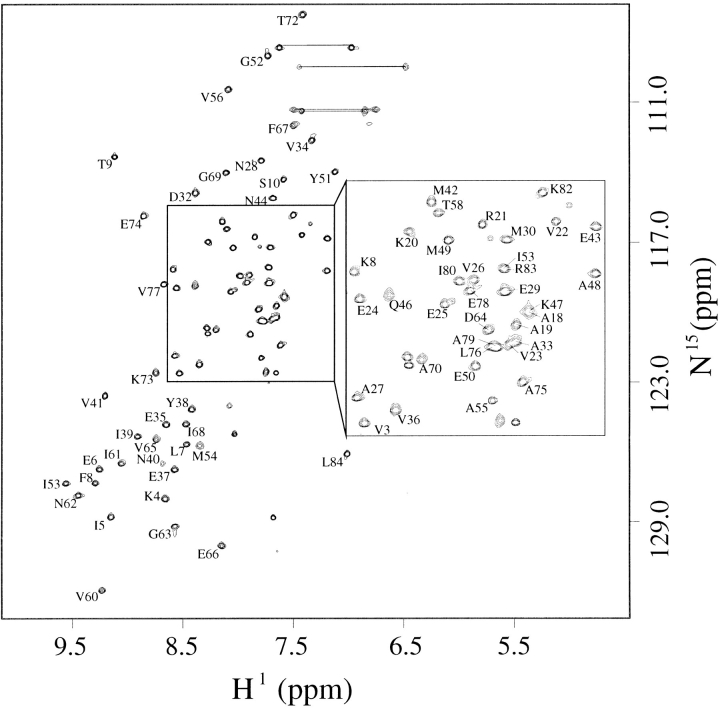

The hyperthermophilic nature of M. jannaschii (optimum growth temperature of 85°C) was exploited in the resonance assignment process of Mj0307 by collecting the experiments relevant for assignments at 60°C. The elevated temperature significantly improves the quality of experiments that exclusively use J coupling for information transfer. The amide backbone (except for proline residues) and side chain assignments were established for all residues except M0, S1, and P11 through P17. There are unassigned 15N-1H correlations in the HSQC spectrum that could possibly belong to some of the unassigned residues, but assignments could not be made unambiguously. The pH of our nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) samples was 6.1, and although biologically relevant, the amide proton exchange rate can be sufficient to lead to solvent exchange. Furthermore, the unassigned residues are located in solvent exposed and inherently flexible regions. It is possible that the combination of these inherent characteristics and sample properties may account for the inability to assign some of these residues. The assigned 15N-1H HSQC spectrum is shown in Figure 2 ▶, and a strip plot of slices from the 15N-resolved NOESY is shown in Figure 3 ▶.

Fig. 2.

The assigned backbone amide protons in an 15N-1H HSQC spectrum of Mj0307 at 60°C and 600 MHz (1H). Thin lines connect the peaks arising from side chain 15N-1H correlations.

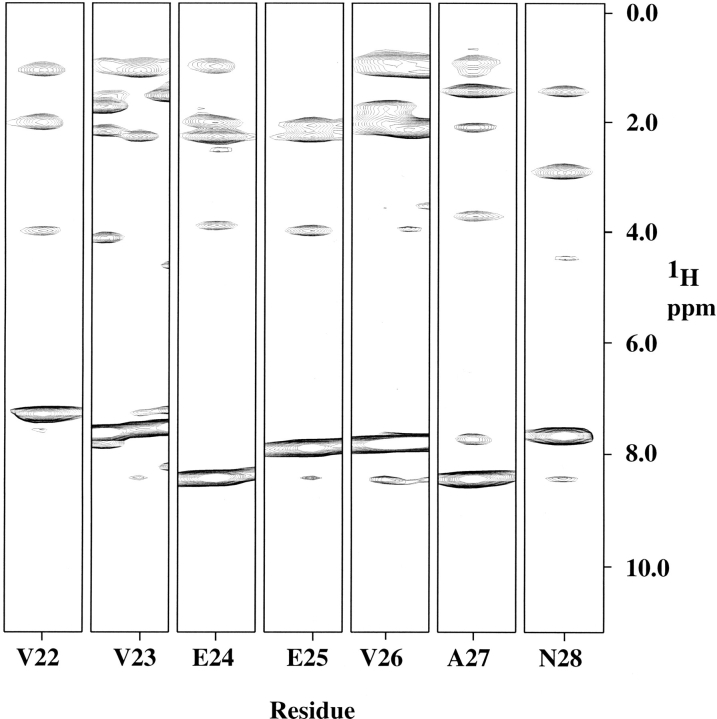

Fig. 3.

A strip plot from an 15N-resolved NOESY experiment taken at 35°C and 600 MHz (1H). Strips are shown for residues V22 through N28, part of helix 1 in Mj0307. The strips are labeled by residue number.

Experiments that rely on the nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) for resonance information transfer were of significantly lower quality at 60°C compared with those collected at 25°C or 35°C. This observation can be explained by considering the relationship between the intensity of the NOE and the rotational correlation time. Equation 1 displays the critical situation when the NOE vanishes, irrespective of the mixing time:

|

1 |

where ω0 is the Lamour frequency and τc is the rotational correlation time (Ernst et al. 1997). At values of 600 and 500 MHz, the critical rotational correlation times are 1.7 nsec and 2.2 nsec, respectively. As discussed below, Mj0307 is structurally similar to the E. coli Grx-1 protein, which has an estimated τc of 6.4 nsec at 25°C (Kelly et al. 1997). Assuming that the τc of Mj0307 is the same, then the τc at 60°C can be estimated by determining the ratio of τc25°C/τc60°C by using equation 2:

|

2 |

where r is the radius of the protein, η is the solvent viscosity, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the temperature. Using this approach, one obtains an approximate τc60°C of 2.9ns. Thus, the lower quality of the NOE data sets collected at 60°C, especially at 600 MHz, is almost certainly the result of approaching the critical τc value.

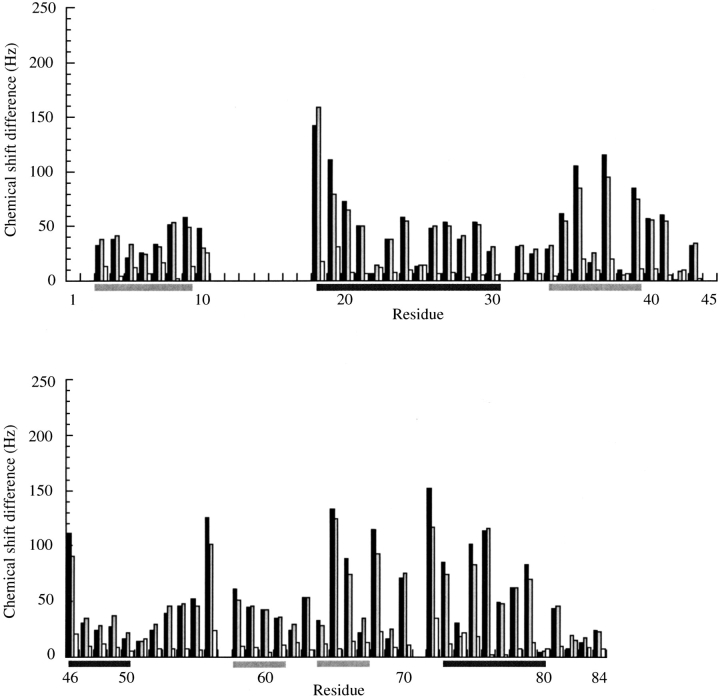

Even though the initial resonance assignments were made at 60°C, only modest changes in the chemical shifts were observed at lower temperatures. The observed changes in the backbone amide cross-peak positions in the 15N-1H HSQC spectra are shown in Figure 4 ▶. The changes between 15N-1H HSQC cross-peaks positions at 35°C and 25°C are also shown in Figure 4 ▶ because the 15N edited [1H-1H]NOESY-HSQC, and the 3D and 4D 13C edited [1H-1H]NOESY experiments were optimized at those temperatures, respectively. Although the observed changes in the 15N-1H HSQC cross-peak positions are modest, it can be seen from Figure 4 ▶ that the most temperature-sensitive changes between 60°C and the lower temperatures occur in the loop regions and at the edges of secondary structure. The most pronounced changes are at the start of the α2 helix and junction between β4 and α3. The changes between 35°C and 25°C are trivial throughout the entire protein.

Fig. 4.

The temperature dependence of the values for the backbone amide cross-peak chemical shift values in 15N-1H HSQC spectra. (black bars) Changes (in Hz) from 60°C to 25°C; (gray bars) changes (in Hz) from 60°C to 35°C; (white bars) changes (in Hz) between 35°C and 25°C. The change in cross peak chemical shifts, ΔHz, were calculated using the expression ΔHz = [(ΔHz15N)2 + (ΔHz1H)2]1/2. The secondary structure is indicated under the residue numbers with β strands (light gray bars) and helices (dark bars).

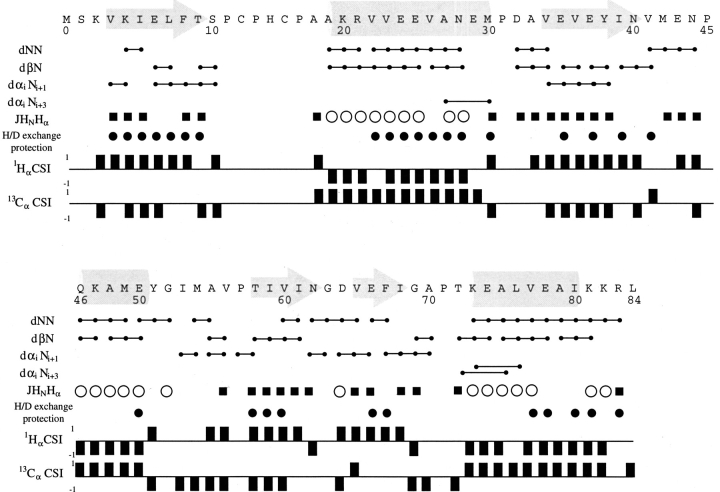

The short- and medium-range backbone amide proton NOEs, backbone 3-bond HαHN coupling constants, 1Hα and 13Cα chemical shift indices, and the backbone amide proton/deuteron exchange protection pattern for Mj0307 are presented in Figure 5 ▶. From these data, it can be seen that Mj0307 adopts the minimal βαβαββα secondary structure pattern of the thioredoxin fold. Using these constraints, as well as long-range NOEs, we determined the solution structure of Mj0307. The structure calculations were constrained by 505 NOEs, 52 backbone φ torsion angle, and 30 hydrogen bonds inferred from proton/deuteron exchange protection. Having started from 60 random conformers, we refined the 20 best calculated structures by using DYANA (Güntert et al. 1997) by energy minimization using the program OPAL (Luginbühl et al. 1996). The refined structure ensemble possesses 0.1 ± 0.3 NOE distance violations ≥0.1 Å; 0.1 ± 0.2 residual dihedral angle violations ≥2.5°; total AMBER energies of −3031 ± 146 kcal/mole (with −235 ± 13 kcal/mole and 3522 ± 163 kcal/mole contributions from van der Waals and electrostatic terms, respectively; see also Table 1). The refined structures were also analyzed with PROCHECK (Laskowski et al. 1993; Rullman 1996), which indicated that 97% of the residues fall into allowed or generously allowed regions of the Ramachandran map. A stereoview of the N, Cα, and C` backbone atoms from all 20 refined structures (PDB 1FO5) are presented in Figure 6A ▶, with the local root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) shown in Figure 6B ▶. A representative conformer of the final 20 structures with Kabsch-Sander secondary structure rendering is presented in Figure 7A ▶ (Kabsch and Sander 1983).

Fig. 5.

Summary of the short- and medium-range backbone amide proton NOEs, semiquantitative JHNHα coupling constant analysis, proton/deuteron exchange protection patterns, and chemical shift index (CSI) information. (lines capped with filled circles) NOE correlation between the given residues; (open circles and filled squares) JHNHα coupling constant values of <6 and >9 Hz, respectively; (filled circles) amide protons that were protected after 24 hours in the proton/deuteron exchange protection experiments. Helical regions are indicated by −1 and +1 values in the 1H CSI and 13C CSI analysis, respectively. Opposite values are indicative of an extended backbone conformation. CSI analysis was performed according to Wishart and Sykes (1994).

Table 1.

Structure statistics for Mj0307 final 20 structures

| Total restraints used | 587 |

| Total NOE restraints | 505 |

| Intraresidue | 65 |

| Sequential (|i − j| = 1) | 120 |

| Medium range (1 < |i − j| < 4) | 87 |

| Long range (|i − j| > 4) | 96 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 30 |

| Dihedral restraints | 52 |

| Rmsd from experimental constraints distance restraint violations | 0.1 ± 0.3 ≥ 0.1Å |

| dihedral restraint violations | 0.1 ± 0.2 ≥ 2.5° |

| Final energies (AMBER) | −3031 ± 146 kcal/mol |

| Coordinate precision (Å) | |

| Rmsd of backbone | 1.1 Å |

| Rmsd all heavy atoms | 1.6 Å |

| Rmsd of backbone in 2° struct | 0.6 Å |

| PROCHECK statistics | |

| Residues in most favored regions | 65% |

| Residues in add. allowed regions | 27% |

| Residues in gen. allowed regions | 4% |

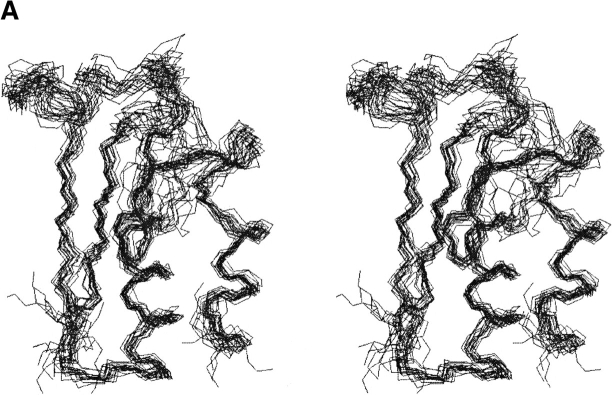

Fig. 6.

(A) A stereoview of the superposition of N, Cα, and C` backbone atoms from the 20 best calculated and refined structures. This figure was created with the program MOLMOL (Koradi et al. 1996). (B) The local RMSD of the backbone atoms is shown as a function of residue number using the superposition shown in A. (light gray bars) Positions of strands; (dark gray bars) helices.

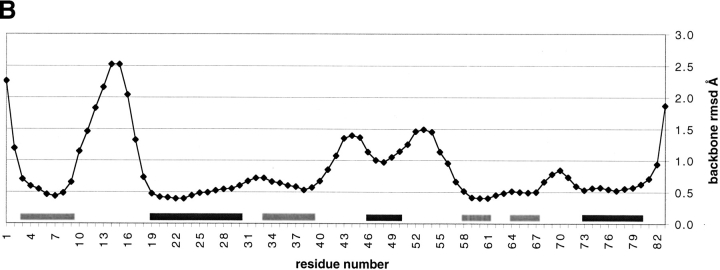

Fig. 7.

(A) A representative structure from the set of 20 calculated and refined solution structures of Mj0307 in the reduced state. (B) An overlay of the Mj0307 structure in A (in red) with a representative structure of reduced E. coli Grx1 (in blue; Sodano et al. 1993) is shown. The alignment was generated by fitting equivalent residues in the β sheet (with an RMSD of 0.69 Å). These renderings were generated with the visualization program MOLMOL (Koradi et al. 1996).

The tertiary structure of Mj0307 adopts the recognizable thioredoxin fold. The β strands have an ↑↑↓↑ orientation that form a single β sheet. The α1 and α3 helices pack against each other in a parallel manner on one side of the β sheet. The α2 helix is perpendicular to the orientation of the α1 and α3 helices on the opposite side of the β sheet. Other structural features characteristic of the thioredoxin fold include the omega backbone angle for residue P57, which is in the cis conformation. This backbone conformation has been observed for almost all prolines in this highly conserved position (Martin 1995). The F8 side chain packs into a hydrophobic pocket formed by the N terminus of the α2 helix and the loop connecting the β2 strand and the α2 helix. The F8 position is highly conserved in all disulfide oxidoreductases as either a phenylalanine or a tyrosine residue.

The tertiary structure of Mj0307 is similar to the oxidized and reduced E. coli Grx-1 structures (Fig. 7B ▶). Differences between these structures include the α2 helix, which is considerably shorter in Mj0307. The backbone conformation of the residues in the α2 helix are not as well defined as their counterparts in α1 and α3 helices. Using the Kabsch-Sander secondary structure rendering (Kabsch and Sander 1983), we found that residues Q46 to E50 adopt an α-helical conformation in some of the final 20 conformers, whereas in the other conformers these residues adopt a bend conformation. In the conformation displayed in Figure 7 ▶, A and B, these residues are in the helical conformation. Another difference between Mj0307 and E. coli Grx1 is in the connection between β4 strand and α3 helix. In Mj0307, this connection is composed of the six residues I68 to K73, whereas this junction in Grx-1 (and all mesophilic prokaryotic or eukaryotic Grx structures) is composed of a single glycine residue.

The calculated structures also show that almost all of the residues that display the greatest changes with temperature, shown in Figure 4 ▶, are confined to one of two regions. Residues A18, A19, V36, and Y38 form one cluster, and the second is formed by V65, I68, T72, A75, and L76. The structures show that the side chains of these clustered residues pack against each other, and whatever changes that occur between the 60°C and the lower temperatures are confined to these two regions.

Although the structural data reveal that Mj0307 is structurally similar to the mesophilic Grx proteins, its biological function in vivo is not as clear. In agreement with previous findings (Lee et al. 2000), we found that Mj0307 does function as a general disulfide oxidoreductase as shown by its ability to precipitate insulin in the presence of DTT (data not shown). Neither Mj0307 nor its archael homolog, Mt0807, functions as a Grx-like protein (McFarlan et al. 1992; Lee et al. 2000). Furthermore, Mt0807 was shown not to interact with Trr from either E. coli or Corynebacterium nephridii, but Mj0307 displayed a weak interaction with E. coli Trr. These results suggest a weak functional similarity to Trx proteins. The active site tetrapeptide sequence in Mj0307 (Mj0307 residues 13 through 16) is the same as the mesophilic bacterial DsbA protein, which is essential for disulfide bond rearrangement and has been shown to catalyze the refolding of scrambled RNaseA (Yu et al. 1993). Despite this similarity to DsbA, we were not able to observe Mj0307 catalysis of scrambled RnaseA refolding (results not shown).

In an attempt to gain a better insight into the possible biological function of Mj0307, we examined amino acid sequence alignments with several known disulfide oxidoreductase proteins. Sequence alignments with either mesophilic bacterial DsbA or eukaryotic PDI proteins are quite poor (∼12%–13% and 6%–9% sequence identities for DsbA and PDI proteins, respectively), but alignments with the NrdH proteins are significantly better (21%–23% sequence identity). Sequence alignments using Grx and Trx proteins from mesophilic bacteria and eukaryotes show the best sequence homology (19%–30% and 16%–30% for Trx and Grx, respectively).

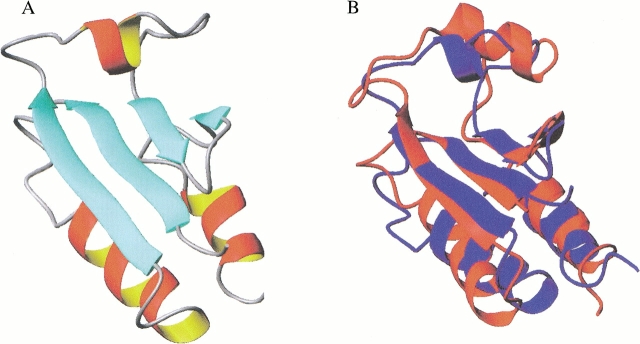

To further examine the relationship between Mj0307 and known Grx, Trx, and NrdH proteins, we examined structure-based sequence alignments (Fig. 8 ▶). Several conserved structural features were used to generate the alignment in Figure 8 ▶, among which included the conserved phenylalanine (or tyrosine) residue at position 8 (unless otherwise stated, position numbers refer to the numbering of Fig. 8 ▶), the CXXC active site tetrapeptide, the cis-proline residue at position 68, and the glycine residue at position 83.

Fig. 8.

Structure-based sequence alignment for H. sapiens Trx (HTrx), E. coli Trx (ETrx), H. sapiens Grx (HGrx), E. coli Grx-1 (EGrx1), Mj0307, and E. coli NrdH (ENrdH). (blue) Residues that adopt a β strand conformation; (red) helical residues. The residues that are important for protein–protein interactions in Trx (Eklund et al. 1991), glutathoine binding in HGrx, and EGrx1 are colored in yellow (Bushweller et al. 1994; Yang et al. 1998). The residues that are conserved in Mj0307, Mt0807, and Af2145 are also colored yellow in the Mj0307 sequence. The residues that are conserved in all of the aligned sequences are indicated by an asterisk below the alignment. The structures for all sequences are accessible in the Protein Databank, except ENrdH, which has its secondary structure derived from the PHD structure prediction (Rost 1996) and sequence homology.

Several interesting structure/function-related features are apparent in Figure 8 ▶. The residues that have been shown to make several important contacts with bound glutathione in Homo sapiens and E. coli Grx (residue positions 83–85) form the N terminus of a helix. In Mj0307, however, these residues are part of a loop structure, which is similar to the Trx and NrdH proteins. Thus, not only are the residue identities of positions 83–85 between Mj0307 and Grx proteins not conserved, but the secondary structure is also not conserved either. These sequence and structural differences most likely account for the inability of Mj0307, and Mt0807 as well, to behave as Grx proteins. In Trx proteins, the residues of this loop region at positions 83–87 have been shown to be essential for the interaction with Trr (Eklund et al. 1991). In Mj0307, these residues are similar to those found in E. coli Trx. This similarity, absent in Mt0807, may be enough to allow for an interaction with Trr. Although the loop region of positions 83–87 of Mj0307 resembles Trx proteins, the β-strand/loop/β-strand motif of positions 69–81 is more like the Grx proteins rather than the Trx proteins. The NrdH proteins also share a Grx resemblance in this region.

The alignment in Figure 8 ▶ also reveals that the residues that are conserved between Mj0307, Mt0807, and Af2145 cluster in the same regions as the residues that have been shown to be essential for either glutathione binding in Grx or protein–protein interactions in Trx. This observation would imply that the binding surface has been conserved among the Grx, Trx, and the Mj0307, Mt0807, and Af2145 proteins. The identity of the residues conserved between Mj0307, Mt0807, and Af2145 have both Grx and Trx characteristics. Although the conserved residues in positions 83–87 have some resemblance to E. coli Trx, the residues flanking the conserved cis-proline residue (position 68) have a Grx likeness. This likeness is highlighted by the presence of a valine residue at position 67, which is highly conserved in Grx proteins. The conserved residues in the active site and the surrounding region are also interesting because they do not have much resemblance to either a Grx or a Trx. The active site CXXC has been found to be highly conserved between Grx and Trx proteins. Although Mt0807 and Af2145 have an active site that is the same as the Grx proteins, the Mj0307 active site is identical to DsbA. The residue that immediately follows CXXC motif is conserved in all Trx and eukaryotic Grx proteins as an arginine or lysine, but this position in mesophilic bacteria is conserved as a valine and conserved as a proline in Mj0307, Mt0807, and Af2145. The consensus sequence of the five residues preceding the active site is FXKXX and F(W/S)AXW for Grx and Trx proteins, respectively. In the archael proteins, these residues form the pentapeptide FTSP(T/M), which is different from the Grx and Trx proteins as well as the NrdH proteins.

Discussion

We have determined the solution structure of the Mj0307 protein from the archaebacteria M. jannaschii in its reduced form. The solution structure shows that the βαβαββα secondary structure in this protein adopts the minimal thioredoxin fold and incorporates many structural features characteristic of this type of fold (Martin 1995). The secondary structure pattern in Mj0307 also has been identified by Lee and co-workers (Lee et al. 2000). Although the secondary structure assignments from our work coincide well with their results, there are two areas in which there are differences. One area is the starting point of the α2 helix. Our data indicate that this helix begins at residue A19, but Lee and co-workers suggest that it begins at H15. Because of the difficulty in obtaining resonance assignment information for the residues between P11 and P17, we do not necessarily disagree with this possibility. The observed JHαHN coupling constant for A18 in our data, however, does suggest that it is not in a helical conformation. The second discrepancy is the initiation of the β3 strand. Our data indicate that this strand stretches from T58 to I61, instead of M54 to I61 as Lee and co-workers suggest. Unlike the beginning of α2, our assignments and data are complete in this region. The JHαHN coupling constant for V56 and the presence of dαiNi + 1 NOEs at M54 and V56 are consistent with an extended strand conformation, but there is no amide backbone proton/deuteron exchange protection for any of the residues between I53 to V56. This would suggest that these residues do not adopt a well-formed β strand as do residues T58–-I61, and this observation is verified in the calculated structures.

Although the experiments for the structural data were collected at temperatures (25°C and 35°C) that are much lower than the native conditions of Mj0307 (upward of 85°C), the 1H-15N HSQC cross-peak positions display only a slight temperature dependence between 60°C and 25°C. The residues that display the most sensitivity to temperature are those that have side chains that pack together at either the N terminus of the α2 helix or in the loop region between the β4 strand and α3 helix. The structural location and modest nature of temperature-dependent shifts suggest that there may only be slight temperature-dependent changes in local secondary structure and not gross changes in tertiary structure.

The structural similarity of Mj0307 to the mesophilic bacterial Grx proteins might suggest that Mj0307 also functions as a Grx protein. There is ample evidence, however, to argue against such a suggestion. It has been reported that Mj0307 and Mt0807 do not show Grx behavior in functional assays (McFarlan et al. 1992; Lee et al. 2000), and this functional behavior can be explained by the structure-based sequence alignment (Fig. 8 ▶) that shows that the residues necessary for glutathione binding have not been conserved. Furthermore, it is likely that M. jannaschii, like M. thermoautotrophicum and other achaebacteria, exist in the absence of glutathione, which prevents any protein in these organisms from being classified as a Grx protein (Newton and Javor 1985; McFarlan et al. 1992).

The active site tetrapeptide sequence is highly conserved among the different classes of protein disulfide oxidoreductases, and the Mj0307 active site is identical to the mesophilic bacterial DsbA proteins. It is most unlikely, however, that Mj0307 has a similar biological function as DsbA because of the very poor overall sequence similarity to DsbA, the large differences in secondary and tertiary structure, and the inability of Mj0307 to promote refolding of scrambled RnaseA.

Lee and co-workers have reported a standard state redox potential of −277 mV for Mj0307, and this value makes Mj0307 the most reductive protein disulfide oxidoreductase known (Lee et al. 2000). This value is in stark contrast to DsbA, which has an identical active site and the most oxidative redox standard state measured for protein disulfide oxidoreductases (Wunderlich and Glockshuber 1993; Zapun et al. 1993). It has been well documented that the redox potential of protein disulfide oxidoreductases is modulated by more than just the two residues in the center of the CXXC motif. Residues outside the active site and helix dipoles can significantly affect the active site redox potential, and slight changes in the three-dimensional structure also can influence how these factors affect the redox potential (Chivers et al. 1997; Rossmann et al. 1997; Guddat et al. 1998; Krimm et al. 1998). The temperature-dependent changes in 1H-15N HSQC cross-peak positions suggest that there are slight structural changes in the vicinity of the active site that are induced by temperature changes. It is plausible that these changes affect the redox potential of Mj0307, and thus the redox potentials measured under mesophilic temperature and pressure conditions may not accurately reflect the redox potential under the conditions at which M. jannaschii normally lives. The impact of these experimental conditions have been documented in studies with a rubredoxin protein from Pyrococcus furiosus, which showed dramatic differences in redox potentials as a function of temperature and pressure (de Pelichy and Smith 1999).

Lee and co-workers also have reported that Mj0307 displays a weak interaction with Trr from E. coli (Lee et al. 2000). This weak interaction may be directed by the loop region connecting the β4 strand and the α3 helix, which shows a resemblance to the same region in E. coli Trx (Fig. 8 ▶). The equivalent loop regions in Mt0807 and Af2145 do not have this resemblance to E. coli Trx, and, relatedly, Mt0807 has been shown not to interact with E. coli Trr (McFarlan et al. 1992). The residues outside this loop region that are conserved between the Mj0307, Mt0807, and Af2145 proteins also do not show much similarity to those residues known to be important for protein–protein interactions in the known mesophilic bacterial and eukaryotic Trx proteins.

The in vivo function of Mj0307, and also Mt0807 and Af2145, may be most similar to the mesophilic bacterial NrdH proteins. Despite the modest sequence identity and predicted phylogenetic distance (Jordan et al. 1997), the NrdH proteins and the three archael proteins share a common size and (predicted) secondary structure. At least one member of both sets of proteins have displayed an ability to interact with E. coli Trr. E. coli NrdH serves as a good substrate, whereas the interaction is modest with Mj0307 and nonexistent for Mt0807. The poor interaction between the archael proteins and E. coli Trr, however, may be a consequence of the low sequence identity between the mesophilic and archael proteins, and the necessary residues required for a strong interaction have not been conserved. Trr homologs have been identified in M. jannaschii, M. thermoautotrophicum, and A. fulgidus with moderate sequence identities (32%–36%) to E. coli Trr. If Mj0307, Mt0807, and Af2145 can be reduced by these Trr homologs, then the similarity to the NrdH proteins becomes quite strong. We are engaged currently in efforts to probe the potential interaction between the M. jannaschii proteins.

If the archaebacterial proteins Mj0307, Mt0807, and Af2145 and the NrdH are shown subsequently to be functionally similar, then these proteins may constitute a novel subgroup within the family of protein disulfide oxidoreductases. This subgroup would be characterized by its Grx-like secondary and tertiary structure as well as its ability to interact with an appropriate Trr and not glutathione. This potential new subgroup of protein disulfide oxidoreductases may provide an important bridge in understanding conserved and divergent pathways in archaebacteria, prokaryotes, and eukaryotes that are dependent on protein disulfide oxidation and reduction.

Materials and methods

Cloning, protein purification, and sample preparation

The MJ0307 gene was provided as a generous gift from Professor Sung-Ho Kim (University of California at Berkeley, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory). The gene had been subcloned into a pET21a plasmid (Novagen). The plasmid was amplified using DH5α E. coli cells (GIBCO BRL) and transformed into the BL21(DE3) strain of E. coli cells for protein expression.

Protein expression and uniform isotopic enrichment of 15N or 15N/13C was accomplished by growing the transformed BL21(DE3) cells on M9 growth medium. The M9 medium used [15N]NH4Cl and [13C6]d-glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories or Isotec Inc.) as its sources of isotopic enrichment. Cells were grown at 37°C to an OD of 0.6 and induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Calbiochem) so that the final concentration of IPTG was 1 mM. After induction, cells were allowed to grow another 6 hours before harvesting. After centrifugation, the cell pellets were resuspended in 30 mL of 50 mM Tris at pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The resuspended pellet was sonicated on ice for six 15-sec intervals separated by 45 sec. The sonicated cellular debris was removed by centrifugation. After centrifugation, the supernatant was decanted and heated to 80°C for 10 min. Upon cooling, the precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation. The resulting supernatant was poured through a DEAE Sephrarose column (Amersham Pharmacia). Mj0307 was isolated by running a gradient of NaCl from 0 to 300 mM in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA , 5 mM DTT. The purity of the isolated Mj0307 protein was determined by electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry.

NMR samples were prepared by dialyzing the appropriate fractions from the DEAE column purification step. The protein was dialyzed into a solution with 35 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.1), 5 mM DTT, 0.02% v/v NaN3. The samples were concentrated to an appropriate volume. All samples had a final volume of 500 μL and contained ∼1.5 mM Mj0307.

NMR experiments

All data were collected on either a Bruker AMX-600 or a Bruker DRX-500 spectrometer (Bruker Instruments Inc.) equipped with triple axis or single axis gradient probes, respectively. The 1H and 15N correlation spectra were examined for suitable spectral dispersion by using HSQC experiments (Mori et al. 1995). Experiments for backbone and side chain assignments were conducted at 60°C. These experiments were the HNCACB (Wittekind and Mueller 1993), C(CO)NH (Grzesiek et al. 1993), H(CCO)NH (Grzesiek et al. 1993), 15N-resolved [1H-1H]TOCSY-HSQC (Cavanaugh and Rance 1992), HCCH-TOCSY (Kay et al. 1993), and an 110-msec mixing time 15N-resolved [1H-1H]NOESY-HSQC (Talluri and Wagner 1996). All of the structural constraints were from experiments optimized at 35°C, except the 90-msec mixing time 13C-resolved [1H-1H]NOESY-HSQC (Majumdar and Zuiderweg 1993) and 90-msec mixing time 13C/13C-separated HMQC-NOESY-HMQC (Vuister et al. 1993), which were optimized at 25°C. The short- and medium-range 15N-filtered backbone NOEs were determined from a 95-msec mixing time 15N-resolved [1H-1H]NOESY-HSQC. The torsion angle constraints were semiquantitatively determined based on measured JHαHN coupling constant values from HMQC-J experiments (Kay and Bax 1990). The proton/deuteron exchange protection data were determined from 15N-1H HSQC experiments collected on lyophilized Mj0307 that was resuspended in a 100% D2O solvent. The 15N-1H HSQC spectra were collected at 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 30 hours after resuspension.

All data processing was performed on Silicon Graphics Indigo2 workstations (Silicon Graphics Instruments) with Felix 95 or 97 (BIOSYM/Molecular Simulations). Directly acquired dimensions were treated with a convolution function to minimize the water signal and skewed sine-bell apodization functions before Fourier transformations. The transformed, directly acquired dimensions were phased and baseline-corrected using third-order polynomial correction functions. Indirectly acquired dimensions were apodized with skewed sine-bell functions before Fourier transformation and application of phase correction. Any additional baseline adjustments required after transforming the indirectly acquired dimensions were performed using the baseline convolution function available in Felix 95 and 97.

Structure calculations

Five hundred five upper limit distance constraints, 52 backbone φ torsion angle constraints, and 30 hydrogen bond constraints identified from proton/deuteron exchange protection patterns were used to calculate the solution structure of Mj0307. Calculations were performed using the program DYANA (Güntert et al. 1997). From the 60 random starting conformers, the 20 best conformers had residual target function values of 0.80 Å2 or less. These 20 conformers were further refined with restrained energy minimization by using the AMBER94 forcefield (Cornell et al. 1995) implemented in the program OPAL (Luginb̈hl et al. 1996). A conjugate minimization gradient (1500 steps) was used with bond angle, dihedral angle, van der Waals, electrostatic, NMR distance, and NMR-derived torsion angle terms. The minimization also was performed in a hydration sphere with a minimum thickness of 6 Å (with a dielectric constant of 1) without a cutoff for nonbonded interactions. For the ensemble of 20 refined structures, the heavy atom RMSD was 1.6 Å, the backbone heavy atom RMSD was 1.1 Å, and the residues in secondary structure (Mj0307 residues 3–9, 19–30, 33–39, 46–50, 58–61, 64–67, and 73–80) had an RMSD of 0.6 Å. The refined structures also were analyzed using PROCHECK (Laskowski et al. 1993; Rullman 1996), which indicated that 97% of the residues fall into allowed or generously allowed regions of the Ramachandran map. All DYANA and OPAL calculations as well as PROCHECK analyses were performed using Silicon Graphics Instruments R10000 workstations (Silicon Graphics Instruments). The coordinates for the final 20 structures have been deposited in the RCSB database as entry 1FO5.

Functional assays

The general protein disulfide oxidoreductase activity of Mj0307 was examined using the insulin precipitation assay with DTT as the Mj0307 reductant, as described by Holmgren (Holmgren 1979), by using protein from the NMR sample. The ability of Mj0307 to catalyze the refolding of scrambled RnaseA with DTT as a reductant was monitored by observing the cleavage of 2′-3′ cCMP. Scrambled RnaseA was prepared by incubating a 20-mg/mL solution of native RnaseA in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 120 mM DTT at 37°C for 3 hours. After 3 hours, the RnaseA was diluted to 1 mg/mL with additional 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 120 mM DTT. The DTT then was removed by passing the solution through a PD-10 size exclusion column (Amersham Pharmacia) and eluting the reduced and denatured RnaseA in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 6 M guanidine hydrochloride. The disulfide bonds were allowed to reoxidize under the denaturing conditions by exposure to atmospheric oxygen for 36 h. The 6-M guanidine hydrochloride was removed with a PD-10 size exclusion column. The scrambled RnaseA was eluted in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). The cCMP cleavage assay was performed according the procedure documented by Gilbert (Gilbert 1998).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jeffery Pelton of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory for his assistance with the structure calculations and refinement. This work was supported by the Director, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, Office of Energy Research of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC03-76SF00098, and through instrumentation grants from the U.S. Department of Energy (DE FG05–86ER75281) and the National Science Foundation (DMB 86-09305 and BBS 87-20134).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.35101.

References

- Bardwell, J.C., Lee, J.O., Jander, G., Martin, N., Belin, D., and Beckwith, J. 1993. A pathway for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90 1038–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardi, M.J., Pendred, C.L., and Bushweller, J.H. 1998. Preparation, characterization, and complete heteronuclear NMR resonance assignments of the glutaredoxin (C14S)-ribonucleotide reductase B1 737–761 (C754S) mixed disulfide. Biochemistry 37 5849–5857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushweller, J.H., Billeter, M., Holmgren, A., and Wüthrich, K. 1994. The nuclear magnetic resonance solution structure of the mixed disulfide between Escherichia coli glutaredoxin (C14S) and glutathione. J. Mol. Biol. 235 1585–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh, J. and Rance, M. 1992. Suppression of cross-relaxation effects in TOCSY spectra via a modified DIPSI-2 mixing sequence. J. Magn. Reson. 96 670–678. [Google Scholar]

- Chivers, P.T., Prehoda, K.E., and Raines, R.T. 1997. The CXXC motif: A rheostat in the active site. Biochemistry 36 4061–4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell, W., Cioplak, P., Bayly, C., Gould, I., Merz, K.J., Fergusan, D., Spellmyer, D., Fox, T., Caldwell, J., and Kollman, P. 1995. A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids and organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117 5179–5197. [Google Scholar]

- de Pelichy, L.D.G. and Smith, E.T. 1999. Redox properties of mesophilic and hyperthermophilic rubredoxins as a function of pressure and temperature. Biochemistry 38 7874–7880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund, H., Gleason, F.K., and Holmgren, A. 1991. Structural and functional relations among thioredoxins of different species. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Gen. 11 13–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, R.R., Bodenhausen, G., and Wokaun, A. 1997. Principles of nuclear magnetic resonance in one and two dimensions. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Gilbert, H.F. 1998. Protein disulfide isomerase. Methods Enzymol. 290 26–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzesiek, S., Anglister, J., and Bax, A. 1993. Correlation of backbone amide and aliphatic side-chain resonances in 13C/15N enriched proteins by isotropic mixing of 13C magnetization. J. Magn. Reson. B 101 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Guddat, L.W., Bardwell, J.C.A., and Martin, J.L. 1998. Crystal structure of reduced and oxidized DsbA: Investigation of domain motion and thiolate stablization. Structure 6 757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güntert, P., Mumenthaler, C., and Wüthrich, K. 1997. Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculations with the new program DYANA. J. Mol. Biol. 273 283–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren, A. 1976. Hydrogen donor system for Escherichia coli ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase dependent upon glutathione. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 73 2275–2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren, A. 1979. Thioredoxin catalyzes the reduction of insulin disulfides by dithiothreitol and dihydrolipoamide. J. Biol. Chem. 254 9627–9632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren, A. 1989. Thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. J. Biol. Chem. 264 13963–13966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A., Pontis, E., Aslund, F., Hellman, U., Gibert, I., and Reichard, P. 1996. The ribonucleotide reductase system of Lactococcus lactis. J. Biol. Chem. 271 8779–8785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A., Aslund, F., Pontis, E., Reichard, P., and Holmgren, A. 1997. Characterization of Escherichia coli NrdH. J. Biol. Chem. 272 18044–18050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch, W. and Sander, C. 1983. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: Pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22 2577–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay, L.E. and Bax, A. 1990. New methods for the measurement of NH-Cα coupling constants in 15N labeled proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 86 110–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, L.E., Xu, G.-Y., Singer, A., Muhandram, D., and Forman-Kay, J. 1993. A gradient-enhanced HCCH-TOCSY experiment for recording side-chain 1H and 13C correlations in H2O samples of proteins. J. Magn. Reson. B 101 333–337. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.J., Caputom, T.M., Eaton, S.F., Laue, T.M., and Bushweller, J.H. 1997. Comparison of backbone dynamics of reduced and oxidized Escherichia coli glutaredoxin-1 using 15N NMR relaxation measurements. Biochemistry 36 5029–5044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemmink, J., Darby, N.J., Dijkstra, K., Nigles, M., and Creighton, T.E. 1997. The folding catalyst protein disulfide isomerase is constructed of active and inactive thioredoxin modules. Curr. Biol. 7 239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koradi, R., Billeter, M., and Wüthrich, K. 1996. MOLMOL: A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krimm, I., Lemaire, S., Ruelland, E., Miginiac-Maslow, M., Jaquot, J.P., Hirasawa, M., Knaff, D.B., and Lancelin, J.M. 1998. The single mutation Trp35→Ala in the 35–40 redox site of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii thioredoxin h affects its biochemical activity and the pH dependence of C36-C39 1H-13C NMR. Eur. J. Biochem. 255 185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R.A., MacArthur, M.W., Moss, D.S., and Thornton, J.M. 1993. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 26 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, T.C., Moore, E.C., and Reichard, P. 1964. Enzymatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 239 3436–3444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.Y., Ahn, B.-Y., and Kim, K.-S. 2000. A thioredoxin from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii has a glutaredoxin-like fold but thioredoxin-like activities. Biochemistry 39 6652–6659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luginbühl, P., Güntert, P., Billeter, M., and Wüthrich, K. 1996. The new program OPAL for molecular dynamics simulations and energy refinements of biological macromolecules. J. Biol. Nucl. Magn. Reson. 8 136–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar, A. and Zuiderweg, E.R.P. 1993. Improved C13 resolved HSQC-NOESY spectra in H2O, using pulse field gradients. J. Magn. Reson. B 102 242–243. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.L. 1995. Thioredoxin—A fold for all reasons. Structure 3 245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.L., Bardwell, J.C., and Kuriyan, J. 1993. Crystal structure of the DsbA protein required for disulphide bond formation in vivo. Nature 365 464–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, A.A., Haebel, P.W., Torronen, A., Rybin, V., Baker E.N., and Metcalf, P. 2000. Crystal structure of the protein disulfide bond isomerase, DsbC, from Escherichia coli. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7 196–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlan, S.C., Terrell, C.A., and Hogenkamp, H.P.C. 1992. The purification, characterization and primary structure of a small redox protein from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum, an archaebacterium. J. Biol. Chem. 267 10561–10569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, S., Abeygunawardana, C., Johnson, M.O., and Vanzijl, P.C.M. 1995. Improved sensitivity of HSQC spectra of exchanging protons at short interscan delays using a new fast HSQC (FHSQC) detection scheme that avoids water saturation. J. Magn. Reson. B 108 94–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton, G.L. and Javor, B. 1985. γ-Glutamylcysteine and thiosulfate are major low molecular weight thiols in halobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 161 438–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz, W.A., Aslund, F., Holmgren, A., and Beckwith, J. 1997. The role of the thioredoxin and glutaredoxin pathways in reducing protein disulfide bonds in the Escherichia coli cytoplasm. J. Biol. Chem. 272 15661–15667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmann, R., Stern, D., Loferer, H., Jacobi, A., Glockshuber, R., and Hennecke, H. 1997. Replacement of Pro109 by His in TlpA, a thioredoxin-like protein from Bradyrhizobium japonicum, alters its redox properties but not its in vivo functions. FEBS Lett. 406 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost, B. 1996. PHD: Predicting one-dimensional protein structure by profile based neural networks. Methods Enzymol. 266 525–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rullmann, J.A.C. 1996. AQUA, Computer Program. Department of NMR Spectroscopy, Bijvoet Center for Biomolecular Research, Utrecht University, The Netherlands.

- Schurmann, P. 1995. Ferredoxin: Thioredoxin system. Methods Enzymol. 252 274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodano, P., Xia, T.H., Bushweller, J.H., Bjornberg, O., Holmgren, A., Billeter, M., and Wüthrich, K. 1993. Sequence specific 1H NMR assignments and determination of the three-dimensional structure of reduced Escherichia coli glutaredoxin. J. Mol. Biol. 221 1311–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talluri, S. and Wagner, G. 1996. An optimized 3D NOESY-HSQC. J. Magn. Reson. B 112 200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuister, G.W., Clore, G.M., Gronenborn, A.M., Powers, R., Garrett, R., Tschudin, R., and Bax, A. 1993. Increased resolution and improved spectral quality in 4D 13C/13C-separated HMQC-NOESY-HMQC spectra using pulse field gradients. J. Magn. Reson. B 101 210–213. [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D.S. and Sykes, B.D. 1994. Chemical shift as a tool for structure determination. Methods Enzymol. 239 363–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittekind, M. and Mueller, L. 1993. HNCACB, a high sensitivity 3D NMR experiment to correlate amide proton and nitrogen resonances with the alpha carbon and beta carbon resonances in proteins. J. Magn. Reson. B 101 201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich, M. and Glockshuber, R. 1993. Redox properties of protein disulfide isomerase (DsbA) from Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 2 717–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y., Jao, S.-C., Nanduri, S., Starke, D.W., Mieyal, J.J., and Qin, J. 1998. Reactivity of the human thioltransferase (glutaredoxin) C7S, C25S, C78S, C82S mutant and NMR solution structure of its glutathionyl mixed disulfide intermediate reflect catalytic specificity. Biochemistry 37 17145–17156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J., McLaughlin, S., Freedman, R.B., and Hirst, T.R. 1993. Cloning and active site mutagenesis of Vibrio cholerae DsbA, a periplasmic enzyme that catalyses disulfide bond formation. J. Biol. Chem. 268 4326–4330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapun, A., Bardwell, J.C., and Creighton, T.E. 1993. The reactive and destabilizing disulfide bond of DsbA, a protein required for protein disulfide bond formation in vivo. Biochemistry 32 5083–5092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]